Pediatric Nurses' Views on Obstacles and Support in End-of-Life Care

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/09

|11

|9084

|485

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) nurses' perceptions of obstacles and supportive behaviors in providing end-of-life care to children. A national survey of AACN members revealed that language barriers and parental discomfort with withholding or withdrawing mechanical ventilation were significant obstacles. Supportive behaviors included allowing time alone with the child after death. The study highlights the importance of addressing communication barriers and providing adequate support to nurses in these emotionally challenging situations, ultimately aiming to improve the end-of-life experience for dying children and their families. Desklib provides a platform for students to access similar reports and solved assignments.

By Renea L. Beckstrand,RN, PhD, CCRN, CNE,Nicole L. Rawle,RN, MS, APRN,

Lynn Callister,RN, PhD,and Barbara L. Mandleco,RN, PhD

Background Each year 55 000 children die in the United States,

and most of these deaths occur in hospitals. The barriers and

supportive behaviors in providing end-of-life care to children

should be determined.

Objective To determine pediatric intensive care unit nurses’

perceptions of sizes, frequencies, and magnitudes of selected

obstacles and helpful behaviors in providing end-of-life care

to children.

Method A national sample of 1047 pediatric intensive care

unit nurses who were members of the American Association

of Critical-Care Nurses were surveyed. A 76-item questionnaire

adapted from 3 similar surveys with critical care, emergency,

and oncology nurses was mailed to possible participants.

Nurses who did not respond to the first mailing were sent a

second mailing. Nurses were asked to rate the size and fre-

quency of listed obstacles and supportive behaviors in caring

for children at the end of life.

Results A total of 474 usable questionnaires were received

from 985 eligible respondents (return rate, 48%). The 2 items

with the highest perceived obstacle magnitude scores for size

and frequency means were language barriers and parental

discomfort in withholding and/or withdrawing mechanical

ventilation. The highest supportive behavior item was allowing

time alone with the child when he or she has died.

Conclusions Pediatric intensive care unit nurses play a vital

role in caring for dying children and the children’s families.

Overcoming language and communication barriers with chil-

dren’s families and between interdisciplinary team members

could greatly improve the end-of-life experience for dying

children. (American Journal of Critical Care. 2010;19:543-552)

PEDIATRIC NURSES’

PERCEPTIONS OFOBSTACLES

AND SUPPORTIVEBEHAVIORS

IN END-OF-LIFE CARE

End-of-Life Care

©2009 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009497

www.ajcconline.org AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6543

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

Lynn Callister,RN, PhD,and Barbara L. Mandleco,RN, PhD

Background Each year 55 000 children die in the United States,

and most of these deaths occur in hospitals. The barriers and

supportive behaviors in providing end-of-life care to children

should be determined.

Objective To determine pediatric intensive care unit nurses’

perceptions of sizes, frequencies, and magnitudes of selected

obstacles and helpful behaviors in providing end-of-life care

to children.

Method A national sample of 1047 pediatric intensive care

unit nurses who were members of the American Association

of Critical-Care Nurses were surveyed. A 76-item questionnaire

adapted from 3 similar surveys with critical care, emergency,

and oncology nurses was mailed to possible participants.

Nurses who did not respond to the first mailing were sent a

second mailing. Nurses were asked to rate the size and fre-

quency of listed obstacles and supportive behaviors in caring

for children at the end of life.

Results A total of 474 usable questionnaires were received

from 985 eligible respondents (return rate, 48%). The 2 items

with the highest perceived obstacle magnitude scores for size

and frequency means were language barriers and parental

discomfort in withholding and/or withdrawing mechanical

ventilation. The highest supportive behavior item was allowing

time alone with the child when he or she has died.

Conclusions Pediatric intensive care unit nurses play a vital

role in caring for dying children and the children’s families.

Overcoming language and communication barriers with chil-

dren’s families and between interdisciplinary team members

could greatly improve the end-of-life experience for dying

children. (American Journal of Critical Care. 2010;19:543-552)

PEDIATRIC NURSES’

PERCEPTIONS OFOBSTACLES

AND SUPPORTIVEBEHAVIORS

IN END-OF-LIFE CARE

End-of-Life Care

©2009 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009497

www.ajcconline.org AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6543

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Caring for dying children involves unique barri-

ers. Conflicts arise when futile efforts are continued

to save what society has determined should not be

lost. In a study4 of pediatric palliative health care

providers, barriers included uncertain prognosis,

unwillingness of patients’ family members to acknowl-

edge incurable conditions, language barriers, and

time constraints.

In another study,5 a total of 446 staff members

and physicians were asked about their comfort and

expertise in providing end-of-life care to children.

Staff members felt inexperienced in communicating

about end-of-life issues with patients and patients’

families. Staff members also reported feeling unpre-

pared to deal with pain and symp-

tom management, and a majority

(54%) felt personally unsupported

as they cared for dying children.

Lee and Dupree6 conducted

32 interviews with 29 nurses, physi-

cians, and psychosocial support

personnel about 8 patient deaths

in a large, multidisciplinary PICU.

Themes included the importance

of communication, accommodating the wishes of

others despite a staff member’s own preferences,

issues about use of technology, sadness, and emo-

tional support. The participants reported that they

did not feel adequately supported in dealing with

their grief after caring for a dying child; however,

many welcomed the sadness as a sign of their emo-

tional availability and humanity. Lee and Dupree

concluded that grief, rather than moral distress, was

the dominant response of these caregivers and empha-

sized that research on better communication skills and

emotional support of caregivers was needed.

No published material specifically addresses both

common barriers and supportive behaviors as perceived

by pediatric nurses in end-of-life care. In addition, rela-

tively few researchers4,7,8have addressed the perspectives

of nurses who direct the development of end-of-life care

programs, although nurses bear the major responsibility

for implementing those programs. More than half of

PICU nurses surveyed in 2001 reported that nurses wer

the caregivers who initiated discussions with patients’

families about forgoing life-sustaining treatment.7 Nurses

may feel at a loss as they provide care, because researc

on what really helps dying children and the children’s

families at the end of life is limited.3

Educating clinicians and nurses about end-of-life

decision making and management of infants and chil-

dren, in the context of family-centered care, has not

kept pace with advances in medicine.2,7,8 Care dilemmas

arise as dying patients are placed in an environment

created to sustain life.9 Solomon et al10 found that con-

cerns about overly burdensome treatment were greater

in pediatric end- of-life care than in adult end-of-life

care. They also discovered that nurses were more than

20 times as worried about saving children who

“should not be saved” as about giving up too soon.

Research Questions

The research questions for our study were as follow

• What are the sizes (intensities) and frequencies

of obstacles and supportive behaviors in providing

end-of-life care to infants and children as perceived by

PICU nurses?

• What are the perceived obstacle magnitude

(POM) scores?

• What are the perceived supportive behavior

magnitude (PSBM) scores?

Methods

Design

This was a descriptive quantitative study of PICU

nurses’ perceptions of the size (intensity) of selected

Death of a child evokes deep feelings of tragedy, devastation, and painful co

fusion at the injustice of a life being ended prematurely. Each year 55000

children die in the United States.1,2 Most of the deaths (75%-85%) occur in a

hospital, and most of the hospital deaths take place in pediatric intensive c

units (PICUs).3 The leading cause of death of children more than 1 year old i

unintentional injury. Other major causes include complications of prematurity, death fro

congenital anomalies, cancer, and intentional injuries.2

About the Authors

Renea L. Beckstrand is an associate professor, Nicole L.

Rawle is working in pediatrics, and Lynn Callister and

Barbara L. Mandleco are professors in the College of

Nursing, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Corresponding author: Renea L. Beckstrand,RN, PhD, CCRN,

CNE, Brigham Young University, College of Nursing, 422

SWKT, PO Box 25432, Provo, UT 84602-5432 (e-mail:

renea@byu.edu).

544 AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

Research on the

magnitude of

specified obstacles

or supportive

behaviors is limited.

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

ers. Conflicts arise when futile efforts are continued

to save what society has determined should not be

lost. In a study4 of pediatric palliative health care

providers, barriers included uncertain prognosis,

unwillingness of patients’ family members to acknowl-

edge incurable conditions, language barriers, and

time constraints.

In another study,5 a total of 446 staff members

and physicians were asked about their comfort and

expertise in providing end-of-life care to children.

Staff members felt inexperienced in communicating

about end-of-life issues with patients and patients’

families. Staff members also reported feeling unpre-

pared to deal with pain and symp-

tom management, and a majority

(54%) felt personally unsupported

as they cared for dying children.

Lee and Dupree6 conducted

32 interviews with 29 nurses, physi-

cians, and psychosocial support

personnel about 8 patient deaths

in a large, multidisciplinary PICU.

Themes included the importance

of communication, accommodating the wishes of

others despite a staff member’s own preferences,

issues about use of technology, sadness, and emo-

tional support. The participants reported that they

did not feel adequately supported in dealing with

their grief after caring for a dying child; however,

many welcomed the sadness as a sign of their emo-

tional availability and humanity. Lee and Dupree

concluded that grief, rather than moral distress, was

the dominant response of these caregivers and empha-

sized that research on better communication skills and

emotional support of caregivers was needed.

No published material specifically addresses both

common barriers and supportive behaviors as perceived

by pediatric nurses in end-of-life care. In addition, rela-

tively few researchers4,7,8have addressed the perspectives

of nurses who direct the development of end-of-life care

programs, although nurses bear the major responsibility

for implementing those programs. More than half of

PICU nurses surveyed in 2001 reported that nurses wer

the caregivers who initiated discussions with patients’

families about forgoing life-sustaining treatment.7 Nurses

may feel at a loss as they provide care, because researc

on what really helps dying children and the children’s

families at the end of life is limited.3

Educating clinicians and nurses about end-of-life

decision making and management of infants and chil-

dren, in the context of family-centered care, has not

kept pace with advances in medicine.2,7,8 Care dilemmas

arise as dying patients are placed in an environment

created to sustain life.9 Solomon et al10 found that con-

cerns about overly burdensome treatment were greater

in pediatric end- of-life care than in adult end-of-life

care. They also discovered that nurses were more than

20 times as worried about saving children who

“should not be saved” as about giving up too soon.

Research Questions

The research questions for our study were as follow

• What are the sizes (intensities) and frequencies

of obstacles and supportive behaviors in providing

end-of-life care to infants and children as perceived by

PICU nurses?

• What are the perceived obstacle magnitude

(POM) scores?

• What are the perceived supportive behavior

magnitude (PSBM) scores?

Methods

Design

This was a descriptive quantitative study of PICU

nurses’ perceptions of the size (intensity) of selected

Death of a child evokes deep feelings of tragedy, devastation, and painful co

fusion at the injustice of a life being ended prematurely. Each year 55000

children die in the United States.1,2 Most of the deaths (75%-85%) occur in a

hospital, and most of the hospital deaths take place in pediatric intensive c

units (PICUs).3 The leading cause of death of children more than 1 year old i

unintentional injury. Other major causes include complications of prematurity, death fro

congenital anomalies, cancer, and intentional injuries.2

About the Authors

Renea L. Beckstrand is an associate professor, Nicole L.

Rawle is working in pediatrics, and Lynn Callister and

Barbara L. Mandleco are professors in the College of

Nursing, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Corresponding author: Renea L. Beckstrand,RN, PhD, CCRN,

CNE, Brigham Young University, College of Nursing, 422

SWKT, PO Box 25432, Provo, UT 84602-5432 (e-mail:

renea@byu.edu).

544 AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

Research on the

magnitude of

specified obstacles

or supportive

behaviors is limited.

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

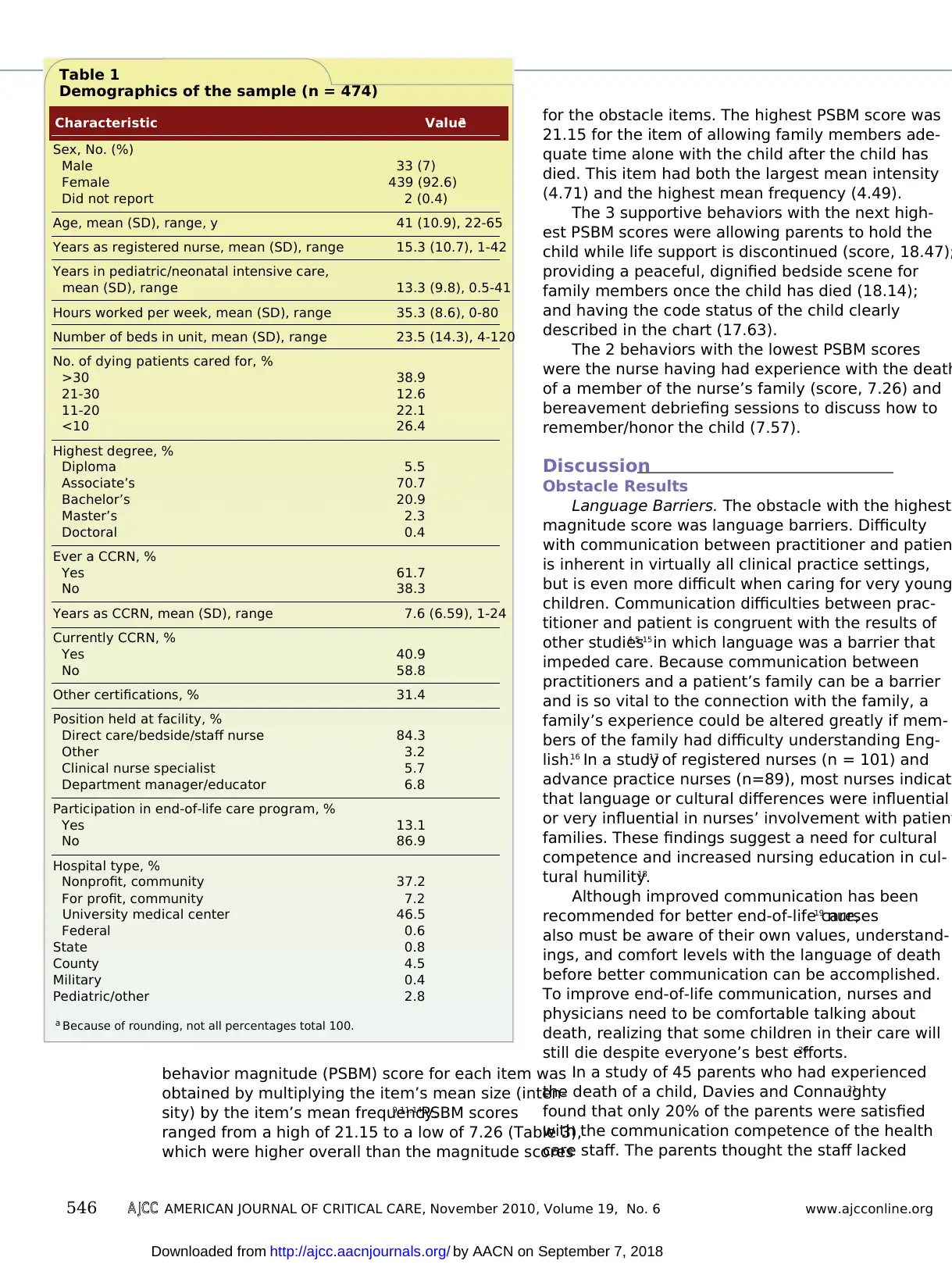

Results

Demographic Data

Of the 1047 potential respondents, 536 returned

questionnaires. A total of 62 questionnaires were

considered ineligible because they were returned by

respondents who did not feel qualified to complete

the questionnaire, were retired, or were no longer

working in a PICU. A few questionnaires were returned

as undeliverable and so were also unusable. Usable

responses were received from 474 of 985 eligible

respondents, for a response rate of 48% after 2 mail-

ings.13 Because the sample was randomly selected,

geographically dispersed, and of adequate size,

results are generalizable to PICU nurses who are

members of AACN. Of the 472 respondents, 439

(92.6%) were women and 33

(7.0%) were men (Table 1). This

percentage of men is slightly lower

than the national AACN member-

ship demographics of 11% men.

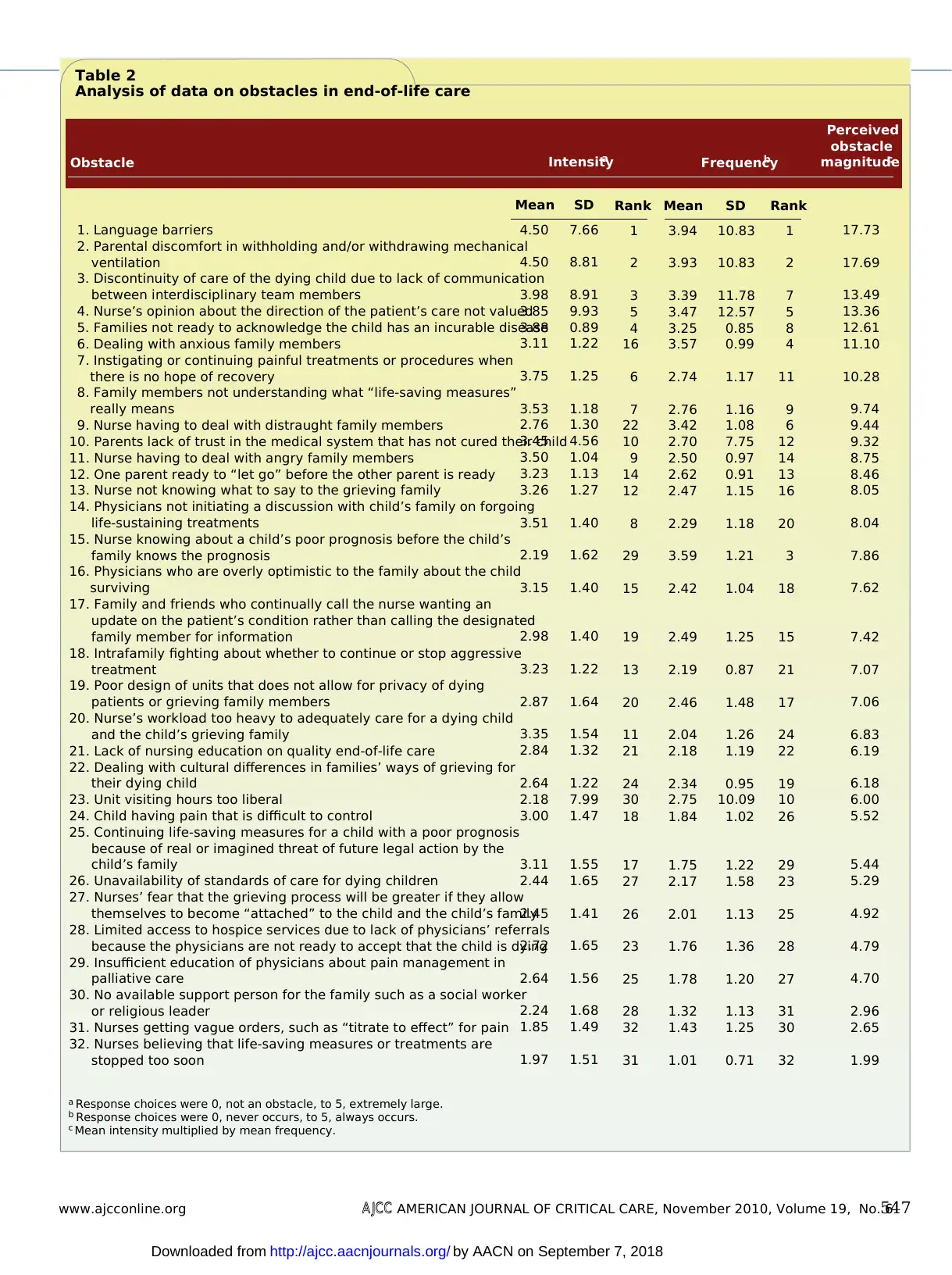

Obstacle Magnitude

Respondents ranked all obstacle

items in the questionnaire by both

size and frequency. The scale used for

obstacle size ranged from 0 (not an

obstacle) to 5 (extremely large). A

similar scale of 0 (never occurs) to 5

(always occurs) was used for scoring

item frequencies. An obstacle’s perceived magnitude or

impact was determined by multiplying its mean size

(intensity) by its mean frequency to obtain a POM

score.9,11,14

For the 32 rated obstacles, the POM scores

ranged from a high of 17.73 to a low of 1.99 (Table

2). The item with the highest POM score was language

barriers (score, 17.73), which had both the highest

mean intensity and the highest mean frequency.

The next 3 obstacles with the highest POM scores

were parental discomfort in withholding and/or with-

drawing mechanical ventilation (score, 17.69), dis-

continuity of care of the dying child due to lack of

communication between interdisciplinary team mem-

bers (13.49), and the nurse’s opinion about the direc-

tion of the patient’s care not being valued (13.36).

The 2 obstacles with the lowest POM scores were

nurses believing that life-saving measures or treatments

are stopped too soon (score, 1.99) and nurses getting

vague orders such as “titrate to effect” for pain (2.65).

Supportive Behavior Magnitude

Supportive behaviors were ranked on a scale of 0

(not a help) to 5 (extremely large). Perceived frequen-

cies for each item were ranked on a scale of 0 (never

occurs) to 5 (always occurs). The perceived supportive

barriers and supportive behaviors in caring for dying

children. The frequency of occurrence of the obstacles

and supportive behaviors also was measured, and

magnitude scores were calculated.

Sample

After the study was approved by the appropri-

ate institutional review board, a geographically

diverse sample of 1047 PICU nurses was obtained

from the American Association of Critical-Care

Nurses (AACN). AACN members who read English,

cared for infants and children, and had experience

in end-of-life care were considered eligible for the

study. Return of the questionnaire was considered

consent to participate in the study.

Instrument

The National Survey of Pediatric Nurses’ Per-

ceptions of End-of-Life Care questionnaire used for

the study was adapted from 3 similar surveys with

critical care nurses,9 emergency nurses,11 and oncol-

ogy nurses.12 In order to strengthen content validity,

information from experts was used to further revise

questionnaire items. The questionnaire was pretested

by 27 pediatric nurses experienced in the care of dying

children. Changes in items were made on the basis of

the nurses’ comments and suggestions. The question-

naire took approximately 23 minutes to complete.

Procedure

Mailing information for the survey was pur-

chased from AACN. Questionnaires were mailed

with a cover letter explaining the purposes of the

study and with a self-addressed, stamped return

envelope. One additional mailing to nonresponders

was completed several months after the initial mail-

ing. The second mailing consisted of a new cover

letter, another copy of the questionnaire, and a

self-addressed stamped envelope for ease of return.

Data Analysis

SPSS software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) was

used for data analysis. Frequencies, measures of cen-

tral tendency, dispersion, and reliability statistics were

calculated. Items were ranked from highest to lowest

on the basis of the mean scores. Items on obstacles

and supportive behaviors also were ranked from most

frequently occurring to least frequently occurring on

the basis of the items’ mean frequency scores. Cron-

bachα scores were calculated to determine internal

consistency estimates of reliability for the size and

the frequency of the obstacle items (0.93 and 0.88,

respectively) and of the supportive behavior items

(0.85 and 0.79, respectively).

www.ajcconline.org AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6545

Obstacles with the

greatest impact

were language ba

riers and parents’

discomfort with

withdrawing

mechanical

ventilation.

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

Demographic Data

Of the 1047 potential respondents, 536 returned

questionnaires. A total of 62 questionnaires were

considered ineligible because they were returned by

respondents who did not feel qualified to complete

the questionnaire, were retired, or were no longer

working in a PICU. A few questionnaires were returned

as undeliverable and so were also unusable. Usable

responses were received from 474 of 985 eligible

respondents, for a response rate of 48% after 2 mail-

ings.13 Because the sample was randomly selected,

geographically dispersed, and of adequate size,

results are generalizable to PICU nurses who are

members of AACN. Of the 472 respondents, 439

(92.6%) were women and 33

(7.0%) were men (Table 1). This

percentage of men is slightly lower

than the national AACN member-

ship demographics of 11% men.

Obstacle Magnitude

Respondents ranked all obstacle

items in the questionnaire by both

size and frequency. The scale used for

obstacle size ranged from 0 (not an

obstacle) to 5 (extremely large). A

similar scale of 0 (never occurs) to 5

(always occurs) was used for scoring

item frequencies. An obstacle’s perceived magnitude or

impact was determined by multiplying its mean size

(intensity) by its mean frequency to obtain a POM

score.9,11,14

For the 32 rated obstacles, the POM scores

ranged from a high of 17.73 to a low of 1.99 (Table

2). The item with the highest POM score was language

barriers (score, 17.73), which had both the highest

mean intensity and the highest mean frequency.

The next 3 obstacles with the highest POM scores

were parental discomfort in withholding and/or with-

drawing mechanical ventilation (score, 17.69), dis-

continuity of care of the dying child due to lack of

communication between interdisciplinary team mem-

bers (13.49), and the nurse’s opinion about the direc-

tion of the patient’s care not being valued (13.36).

The 2 obstacles with the lowest POM scores were

nurses believing that life-saving measures or treatments

are stopped too soon (score, 1.99) and nurses getting

vague orders such as “titrate to effect” for pain (2.65).

Supportive Behavior Magnitude

Supportive behaviors were ranked on a scale of 0

(not a help) to 5 (extremely large). Perceived frequen-

cies for each item were ranked on a scale of 0 (never

occurs) to 5 (always occurs). The perceived supportive

barriers and supportive behaviors in caring for dying

children. The frequency of occurrence of the obstacles

and supportive behaviors also was measured, and

magnitude scores were calculated.

Sample

After the study was approved by the appropri-

ate institutional review board, a geographically

diverse sample of 1047 PICU nurses was obtained

from the American Association of Critical-Care

Nurses (AACN). AACN members who read English,

cared for infants and children, and had experience

in end-of-life care were considered eligible for the

study. Return of the questionnaire was considered

consent to participate in the study.

Instrument

The National Survey of Pediatric Nurses’ Per-

ceptions of End-of-Life Care questionnaire used for

the study was adapted from 3 similar surveys with

critical care nurses,9 emergency nurses,11 and oncol-

ogy nurses.12 In order to strengthen content validity,

information from experts was used to further revise

questionnaire items. The questionnaire was pretested

by 27 pediatric nurses experienced in the care of dying

children. Changes in items were made on the basis of

the nurses’ comments and suggestions. The question-

naire took approximately 23 minutes to complete.

Procedure

Mailing information for the survey was pur-

chased from AACN. Questionnaires were mailed

with a cover letter explaining the purposes of the

study and with a self-addressed, stamped return

envelope. One additional mailing to nonresponders

was completed several months after the initial mail-

ing. The second mailing consisted of a new cover

letter, another copy of the questionnaire, and a

self-addressed stamped envelope for ease of return.

Data Analysis

SPSS software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) was

used for data analysis. Frequencies, measures of cen-

tral tendency, dispersion, and reliability statistics were

calculated. Items were ranked from highest to lowest

on the basis of the mean scores. Items on obstacles

and supportive behaviors also were ranked from most

frequently occurring to least frequently occurring on

the basis of the items’ mean frequency scores. Cron-

bachα scores were calculated to determine internal

consistency estimates of reliability for the size and

the frequency of the obstacle items (0.93 and 0.88,

respectively) and of the supportive behavior items

(0.85 and 0.79, respectively).

www.ajcconline.org AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6545

Obstacles with the

greatest impact

were language ba

riers and parents’

discomfort with

withdrawing

mechanical

ventilation.

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

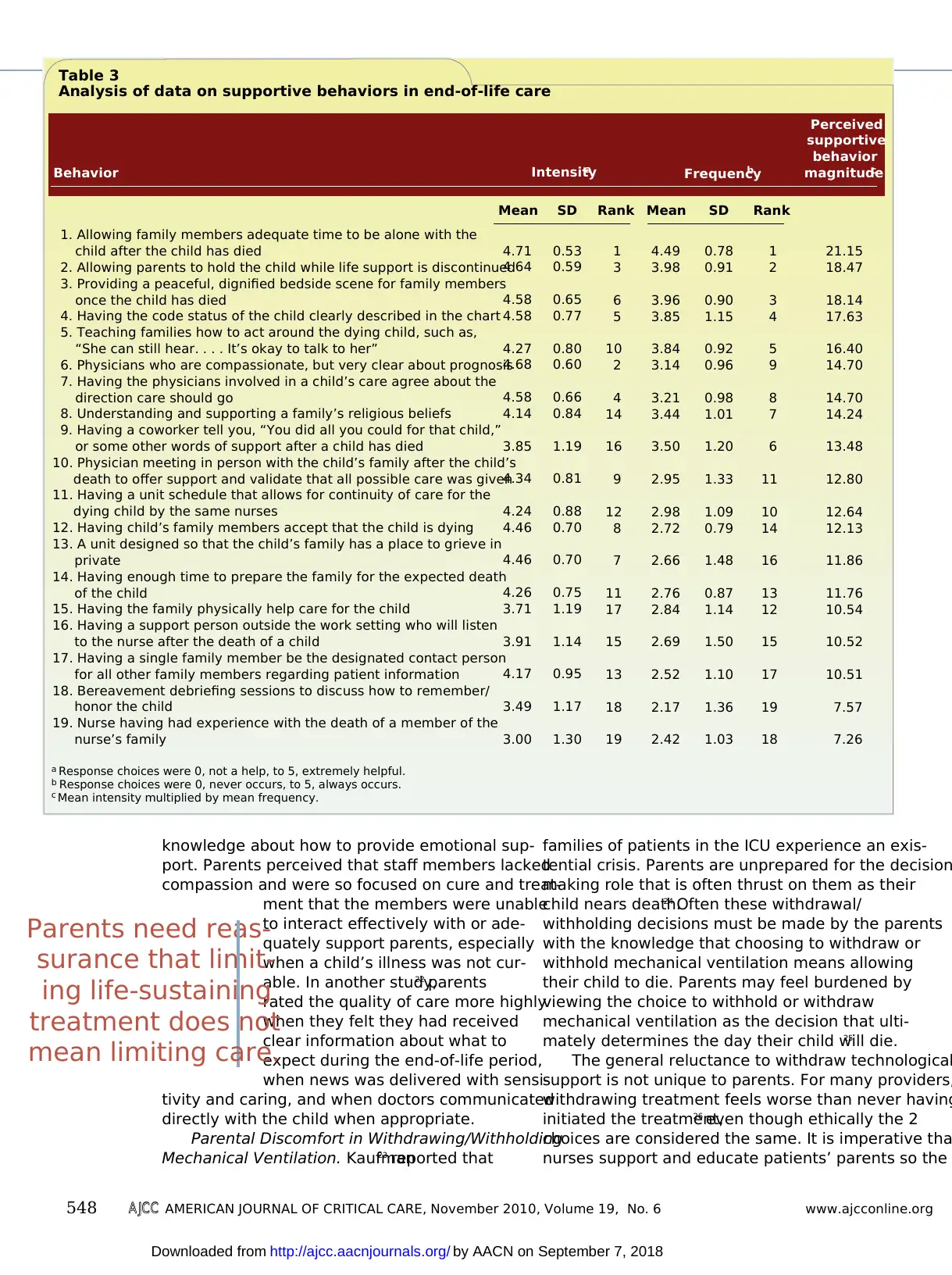

behavior magnitude (PSBM) score for each item was

obtained by multiplying the item’s mean size (inten-

sity) by the item’s mean frequency.9,11,14PSBM scores

ranged from a high of 21.15 to a low of 7.26 (Table 3),

which were higher overall than the magnitude scores

for the obstacle items. The highest PSBM score was

21.15 for the item of allowing family members ade-

quate time alone with the child after the child has

died. This item had both the largest mean intensity

(4.71) and the highest mean frequency (4.49).

The 3 supportive behaviors with the next high-

est PSBM scores were allowing parents to hold the

child while life support is discontinued (score, 18.47);

providing a peaceful, dignified bedside scene for

family members once the child has died (18.14);

and having the code status of the child clearly

described in the chart (17.63).

The 2 behaviors with the lowest PSBM scores

were the nurse having had experience with the death

of a member of the nurse’s family (score, 7.26) and

bereavement debriefing sessions to discuss how to

remember/honor the child (7.57).

Discussion

Obstacle Results

Language Barriers. The obstacle with the highest

magnitude score was language barriers. Difficulty

with communication between practitioner and patien

is inherent in virtually all clinical practice settings,

but is even more difficult when caring for very young

children. Communication difficulties between prac-

titioner and patient is congruent with the results of

other studies4,5,15in which language was a barrier that

impeded care. Because communication between

practitioners and a patient’s family can be a barrier

and is so vital to the connection with the family, a

family’s experience could be altered greatly if mem-

bers of the family had difficulty understanding Eng-

lish.16 In a study17 of registered nurses (n = 101) and

advance practice nurses (n=89), most nurses indicate

that language or cultural differences were influential

or very influential in nurses’ involvement with patient

families. These findings suggest a need for cultural

competence and increased nursing education in cul-

tural humility.18

Although improved communication has been

recommended for better end-of-life care,19 nurses

also must be aware of their own values, understand-

ings, and comfort levels with the language of death

before better communication can be accomplished.

To improve end-of-life communication, nurses and

physicians need to be comfortable talking about

death, realizing that some children in their care will

still die despite everyone’s best efforts.20

In a study of 45 parents who had experienced

the death of a child, Davies and Connaughty21

found that only 20% of the parents were satisfied

with the communication competence of the health

care staff. The parents thought the staff lacked

Table 1

Demographics of the sample (n = 474)

Characteristic Valuea

a Because of rounding, not all percentages total 100.

Sex, No. (%)

Male

Female

Did not report

Age, mean (SD), range, y

Years as registered nurse, mean (SD), range

Years in pediatric/neonatal intensive care,

mean (SD), range

Hours worked per week, mean (SD), range

Number of beds in unit, mean (SD), range

No. of dying patients cared for, %

>30

21-30

11-20

<10

Highest degree, %

Diploma

Associate’s

Bachelor’s

Master’s

Doctoral

Ever a CCRN, %

Yes

No

Years as CCRN, mean (SD), range

Currently CCRN, %

Yes

No

Other certifications, %

Position held at facility, %

Direct care/bedside/staff nurse

Other

Clinical nurse specialist

Department manager/educator

Participation in end-of-life care program, %

Yes

No

Hospital type, %

Nonprofit, community

For profit, community

University medical center

Federal

State

County

Military

Pediatric/other

33 (7)

439 (92.6)

2 (0.4)

41 (10.9), 22-65

15.3 (10.7), 1-42

13.3 (9.8), 0.5-41

35.3 (8.6), 0-80

23.5 (14.3), 4-120

38.9

12.6

22.1

26.4

5.5

70.7

20.9

2.3

0.4

61.7

38.3

7.6 (6.59), 1-24

40.9

58.8

31.4

84.3

3.2

5.7

6.8

13.1

86.9

37.2

7.2

46.5

0.6

0.8

4.5

0.4

2.8

546 AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

obtained by multiplying the item’s mean size (inten-

sity) by the item’s mean frequency.9,11,14PSBM scores

ranged from a high of 21.15 to a low of 7.26 (Table 3),

which were higher overall than the magnitude scores

for the obstacle items. The highest PSBM score was

21.15 for the item of allowing family members ade-

quate time alone with the child after the child has

died. This item had both the largest mean intensity

(4.71) and the highest mean frequency (4.49).

The 3 supportive behaviors with the next high-

est PSBM scores were allowing parents to hold the

child while life support is discontinued (score, 18.47);

providing a peaceful, dignified bedside scene for

family members once the child has died (18.14);

and having the code status of the child clearly

described in the chart (17.63).

The 2 behaviors with the lowest PSBM scores

were the nurse having had experience with the death

of a member of the nurse’s family (score, 7.26) and

bereavement debriefing sessions to discuss how to

remember/honor the child (7.57).

Discussion

Obstacle Results

Language Barriers. The obstacle with the highest

magnitude score was language barriers. Difficulty

with communication between practitioner and patien

is inherent in virtually all clinical practice settings,

but is even more difficult when caring for very young

children. Communication difficulties between prac-

titioner and patient is congruent with the results of

other studies4,5,15in which language was a barrier that

impeded care. Because communication between

practitioners and a patient’s family can be a barrier

and is so vital to the connection with the family, a

family’s experience could be altered greatly if mem-

bers of the family had difficulty understanding Eng-

lish.16 In a study17 of registered nurses (n = 101) and

advance practice nurses (n=89), most nurses indicate

that language or cultural differences were influential

or very influential in nurses’ involvement with patient

families. These findings suggest a need for cultural

competence and increased nursing education in cul-

tural humility.18

Although improved communication has been

recommended for better end-of-life care,19 nurses

also must be aware of their own values, understand-

ings, and comfort levels with the language of death

before better communication can be accomplished.

To improve end-of-life communication, nurses and

physicians need to be comfortable talking about

death, realizing that some children in their care will

still die despite everyone’s best efforts.20

In a study of 45 parents who had experienced

the death of a child, Davies and Connaughty21

found that only 20% of the parents were satisfied

with the communication competence of the health

care staff. The parents thought the staff lacked

Table 1

Demographics of the sample (n = 474)

Characteristic Valuea

a Because of rounding, not all percentages total 100.

Sex, No. (%)

Male

Female

Did not report

Age, mean (SD), range, y

Years as registered nurse, mean (SD), range

Years in pediatric/neonatal intensive care,

mean (SD), range

Hours worked per week, mean (SD), range

Number of beds in unit, mean (SD), range

No. of dying patients cared for, %

>30

21-30

11-20

<10

Highest degree, %

Diploma

Associate’s

Bachelor’s

Master’s

Doctoral

Ever a CCRN, %

Yes

No

Years as CCRN, mean (SD), range

Currently CCRN, %

Yes

No

Other certifications, %

Position held at facility, %

Direct care/bedside/staff nurse

Other

Clinical nurse specialist

Department manager/educator

Participation in end-of-life care program, %

Yes

No

Hospital type, %

Nonprofit, community

For profit, community

University medical center

Federal

State

County

Military

Pediatric/other

33 (7)

439 (92.6)

2 (0.4)

41 (10.9), 22-65

15.3 (10.7), 1-42

13.3 (9.8), 0.5-41

35.3 (8.6), 0-80

23.5 (14.3), 4-120

38.9

12.6

22.1

26.4

5.5

70.7

20.9

2.3

0.4

61.7

38.3

7.6 (6.59), 1-24

40.9

58.8

31.4

84.3

3.2

5.7

6.8

13.1

86.9

37.2

7.2

46.5

0.6

0.8

4.5

0.4

2.8

546 AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 2

Analysis of data on obstacles in end-of-life care

1. Language barriers

2. Parental discomfort in withholding and/or withdrawing mechanical

ventilation

3. Discontinuity of care of the dying child due to lack of communication

between interdisciplinary team members

4. Nurse’s opinion about the direction of the patient’s care not valued

5. Families not ready to acknowledge the child has an incurable disease

6. Dealing with anxious family members

7. Instigating or continuing painful treatments or procedures when

there is no hope of recovery

8. Family members not understanding what “life-saving measures”

really means

9. Nurse having to deal with distraught family members

10. Parents lack of trust in the medical system that has not cured their child

11. Nurse having to deal with angry family members

12. One parent ready to “let go” before the other parent is ready

13. Nurse not knowing what to say to the grieving family

14. Physicians not initiating a discussion with child’s family on forgoing

life-sustaining treatments

15. Nurse knowing about a child’s poor prognosis before the child’s

family knows the prognosis

16. Physicians who are overly optimistic to the family about the child

surviving

17. Family and friends who continually call the nurse wanting an

update on the patient’s condition rather than calling the designated

family member for information

18. Intrafamily fighting about whether to continue or stop aggressive

treatment

19. Poor design of units that does not allow for privacy of dying

patients or grieving family members

20. Nurse’s workload too heavy to adequately care for a dying child

and the child’s grieving family

21. Lack of nursing education on quality end-of-life care

22. Dealing with cultural differences in families’ ways of grieving for

their dying child

23. Unit visiting hours too liberal

24. Child having pain that is difficult to control

25. Continuing life-saving measures for a child with a poor prognosis

because of real or imagined threat of future legal action by the

child’s family

26. Unavailability of standards of care for dying children

27. Nurses’ fear that the grieving process will be greater if they allow

themselves to become “attached” to the child and the child’s family

28. Limited access to hospice services due to lack of physicians’ referrals

because the physicians are not ready to accept that the child is dying

29. Insufficient education of physicians about pain management in

palliative care

30. No available support person for the family such as a social worker

or religious leader

31. Nurses getting vague orders, such as “titrate to effect” for pain

32. Nurses believing that life-saving measures or treatments are

stopped too soon

17.73

17.69

13.49

13.36

12.61

11.10

10.28

9.74

9.44

9.32

8.75

8.46

8.05

8.04

7.86

7.62

7.42

7.07

7.06

6.83

6.19

6.18

6.00

5.52

5.44

5.29

4.92

4.79

4.70

2.96

2.65

1.99

Rank

1

2

7

5

8

4

11

9

6

12

14

13

16

20

3

18

15

21

17

24

22

19

10

26

29

23

25

28

27

31

30

32

SD

10.83

10.83

11.78

12.57

0.85

0.99

1.17

1.16

1.08

7.75

0.97

0.91

1.15

1.18

1.21

1.04

1.25

0.87

1.48

1.26

1.19

0.95

10.09

1.02

1.22

1.58

1.13

1.36

1.20

1.13

1.25

0.71

Mean

3.94

3.93

3.39

3.47

3.25

3.57

2.74

2.76

3.42

2.70

2.50

2.62

2.47

2.29

3.59

2.42

2.49

2.19

2.46

2.04

2.18

2.34

2.75

1.84

1.75

2.17

2.01

1.76

1.78

1.32

1.43

1.01

Rank

1

2

3

5

4

16

6

7

22

10

9

14

12

8

29

15

19

13

20

11

21

24

30

18

17

27

26

23

25

28

32

31

SD

7.66

8.81

8.91

9.93

0.89

1.22

1.25

1.18

1.30

4.56

1.04

1.13

1.27

1.40

1.62

1.40

1.40

1.22

1.64

1.54

1.32

1.22

7.99

1.47

1.55

1.65

1.41

1.65

1.56

1.68

1.49

1.51

Mean

4.50

4.50

3.98

3.85

3.88

3.11

3.75

3.53

2.76

3.45

3.50

3.23

3.26

3.51

2.19

3.15

2.98

3.23

2.87

3.35

2.84

2.64

2.18

3.00

3.11

2.44

2.45

2.72

2.64

2.24

1.85

1.97

Obstacle FrequencybIntensitya

Perceived

obstacle

magnitudec

a Response choices were 0, not an obstacle, to 5, extremely large.

b Response choices were 0, never occurs, to 5, always occurs.

c Mean intensity multiplied by mean frequency.

www.ajcconline.org AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6547

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

Analysis of data on obstacles in end-of-life care

1. Language barriers

2. Parental discomfort in withholding and/or withdrawing mechanical

ventilation

3. Discontinuity of care of the dying child due to lack of communication

between interdisciplinary team members

4. Nurse’s opinion about the direction of the patient’s care not valued

5. Families not ready to acknowledge the child has an incurable disease

6. Dealing with anxious family members

7. Instigating or continuing painful treatments or procedures when

there is no hope of recovery

8. Family members not understanding what “life-saving measures”

really means

9. Nurse having to deal with distraught family members

10. Parents lack of trust in the medical system that has not cured their child

11. Nurse having to deal with angry family members

12. One parent ready to “let go” before the other parent is ready

13. Nurse not knowing what to say to the grieving family

14. Physicians not initiating a discussion with child’s family on forgoing

life-sustaining treatments

15. Nurse knowing about a child’s poor prognosis before the child’s

family knows the prognosis

16. Physicians who are overly optimistic to the family about the child

surviving

17. Family and friends who continually call the nurse wanting an

update on the patient’s condition rather than calling the designated

family member for information

18. Intrafamily fighting about whether to continue or stop aggressive

treatment

19. Poor design of units that does not allow for privacy of dying

patients or grieving family members

20. Nurse’s workload too heavy to adequately care for a dying child

and the child’s grieving family

21. Lack of nursing education on quality end-of-life care

22. Dealing with cultural differences in families’ ways of grieving for

their dying child

23. Unit visiting hours too liberal

24. Child having pain that is difficult to control

25. Continuing life-saving measures for a child with a poor prognosis

because of real or imagined threat of future legal action by the

child’s family

26. Unavailability of standards of care for dying children

27. Nurses’ fear that the grieving process will be greater if they allow

themselves to become “attached” to the child and the child’s family

28. Limited access to hospice services due to lack of physicians’ referrals

because the physicians are not ready to accept that the child is dying

29. Insufficient education of physicians about pain management in

palliative care

30. No available support person for the family such as a social worker

or religious leader

31. Nurses getting vague orders, such as “titrate to effect” for pain

32. Nurses believing that life-saving measures or treatments are

stopped too soon

17.73

17.69

13.49

13.36

12.61

11.10

10.28

9.74

9.44

9.32

8.75

8.46

8.05

8.04

7.86

7.62

7.42

7.07

7.06

6.83

6.19

6.18

6.00

5.52

5.44

5.29

4.92

4.79

4.70

2.96

2.65

1.99

Rank

1

2

7

5

8

4

11

9

6

12

14

13

16

20

3

18

15

21

17

24

22

19

10

26

29

23

25

28

27

31

30

32

SD

10.83

10.83

11.78

12.57

0.85

0.99

1.17

1.16

1.08

7.75

0.97

0.91

1.15

1.18

1.21

1.04

1.25

0.87

1.48

1.26

1.19

0.95

10.09

1.02

1.22

1.58

1.13

1.36

1.20

1.13

1.25

0.71

Mean

3.94

3.93

3.39

3.47

3.25

3.57

2.74

2.76

3.42

2.70

2.50

2.62

2.47

2.29

3.59

2.42

2.49

2.19

2.46

2.04

2.18

2.34

2.75

1.84

1.75

2.17

2.01

1.76

1.78

1.32

1.43

1.01

Rank

1

2

3

5

4

16

6

7

22

10

9

14

12

8

29

15

19

13

20

11

21

24

30

18

17

27

26

23

25

28

32

31

SD

7.66

8.81

8.91

9.93

0.89

1.22

1.25

1.18

1.30

4.56

1.04

1.13

1.27

1.40

1.62

1.40

1.40

1.22

1.64

1.54

1.32

1.22

7.99

1.47

1.55

1.65

1.41

1.65

1.56

1.68

1.49

1.51

Mean

4.50

4.50

3.98

3.85

3.88

3.11

3.75

3.53

2.76

3.45

3.50

3.23

3.26

3.51

2.19

3.15

2.98

3.23

2.87

3.35

2.84

2.64

2.18

3.00

3.11

2.44

2.45

2.72

2.64

2.24

1.85

1.97

Obstacle FrequencybIntensitya

Perceived

obstacle

magnitudec

a Response choices were 0, not an obstacle, to 5, extremely large.

b Response choices were 0, never occurs, to 5, always occurs.

c Mean intensity multiplied by mean frequency.

www.ajcconline.org AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6547

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

knowledge about how to provide emotional sup-

port. Parents perceived that staff members lacked

compassion and were so focused on cure and treat-

ment that the members were unable

to interact effectively with or ade-

quately support parents, especially

when a child’s illness was not cur-

able. In another study,22 parents

rated the quality of care more highly

when they felt they had received

clear information about what to

expect during the end-of-life period,

when news was delivered with sensi-

tivity and caring, and when doctors communicated

directly with the child when appropriate.

Parental Discomfort in Withdrawing/Withholding

Mechanical Ventilation. Kaufman23 reported that

families of patients in the ICU experience an exis-

tential crisis. Parents are unprepared for the decision

making role that is often thrust on them as their

child nears death.24 Often these withdrawal/

withholding decisions must be made by the parents

with the knowledge that choosing to withdraw or

withhold mechanical ventilation means allowing

their child to die. Parents may feel burdened by

viewing the choice to withhold or withdraw

mechanical ventilation as the decision that ulti-

mately determines the day their child will die.25

The general reluctance to withdraw technological

support is not unique to parents. For many providers,

withdrawing treatment feels worse than never having

initiated the treatment,26 even though ethically the 2

choices are considered the same. It is imperative tha

nurses support and educate patients’ parents so the

Table 3

Analysis of data on supportive behaviors in end-of-life care

1. Allowing family members adequate time to be alone with the

child after the child has died

2. Allowing parents to hold the child while life support is discontinued

3. Providing a peaceful, dignified bedside scene for family members

once the child has died

4. Having the code status of the child clearly described in the chart

5. Teaching families how to act around the dying child, such as,

“She can still hear. . . . It’s okay to talk to her”

6. Physicians who are compassionate, but very clear about prognosis

7. Having the physicians involved in a child’s care agree about the

direction care should go

8. Understanding and supporting a family’s religious beliefs

9. Having a coworker tell you, “You did all you could for that child,”

or some other words of support after a child has died

10. Physician meeting in person with the child’s family after the child’s

death to offer support and validate that all possible care was given

11. Having a unit schedule that allows for continuity of care for the

dying child by the same nurses

12. Having child’s family members accept that the child is dying

13. A unit designed so that the child’s family has a place to grieve in

private

14. Having enough time to prepare the family for the expected death

of the child

15. Having the family physically help care for the child

16. Having a support person outside the work setting who will listen

to the nurse after the death of a child

17. Having a single family member be the designated contact person

for all other family members regarding patient information

18. Bereavement debriefing sessions to discuss how to remember/

honor the child

19. Nurse having had experience with the death of a member of the

nurse’s family

21.15

18.47

18.14

17.63

16.40

14.70

14.70

14.24

13.48

12.80

12.64

12.13

11.86

11.76

10.54

10.52

10.51

7.57

7.26

Rank

1

2

3

4

5

9

8

7

6

11

10

14

16

13

12

15

17

19

18

SD

0.78

0.91

0.90

1.15

0.92

0.96

0.98

1.01

1.20

1.33

1.09

0.79

1.48

0.87

1.14

1.50

1.10

1.36

1.03

Mean

4.49

3.98

3.96

3.85

3.84

3.14

3.21

3.44

3.50

2.95

2.98

2.72

2.66

2.76

2.84

2.69

2.52

2.17

2.42

Rank

1

3

6

5

10

2

4

14

16

9

12

8

7

11

17

15

13

18

19

SD

0.53

0.59

0.65

0.77

0.80

0.60

0.66

0.84

1.19

0.81

0.88

0.70

0.70

0.75

1.19

1.14

0.95

1.17

1.30

Mean

4.71

4.64

4.58

4.58

4.27

4.68

4.58

4.14

3.85

4.34

4.24

4.46

4.46

4.26

3.71

3.91

4.17

3.49

3.00

Behavior FrequencybIntensitya

Perceived

supportive

behavior

magnitudec

a Response choices were 0, not a help, to 5, extremely helpful.

b Response choices were 0, never occurs, to 5, always occurs.

c Mean intensity multiplied by mean frequency.

548 AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

Parents need reas-

surance that limit-

ing life-sustaining

treatment does not

mean limiting care.

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

port. Parents perceived that staff members lacked

compassion and were so focused on cure and treat-

ment that the members were unable

to interact effectively with or ade-

quately support parents, especially

when a child’s illness was not cur-

able. In another study,22 parents

rated the quality of care more highly

when they felt they had received

clear information about what to

expect during the end-of-life period,

when news was delivered with sensi-

tivity and caring, and when doctors communicated

directly with the child when appropriate.

Parental Discomfort in Withdrawing/Withholding

Mechanical Ventilation. Kaufman23 reported that

families of patients in the ICU experience an exis-

tential crisis. Parents are unprepared for the decision

making role that is often thrust on them as their

child nears death.24 Often these withdrawal/

withholding decisions must be made by the parents

with the knowledge that choosing to withdraw or

withhold mechanical ventilation means allowing

their child to die. Parents may feel burdened by

viewing the choice to withhold or withdraw

mechanical ventilation as the decision that ulti-

mately determines the day their child will die.25

The general reluctance to withdraw technological

support is not unique to parents. For many providers,

withdrawing treatment feels worse than never having

initiated the treatment,26 even though ethically the 2

choices are considered the same. It is imperative tha

nurses support and educate patients’ parents so the

Table 3

Analysis of data on supportive behaviors in end-of-life care

1. Allowing family members adequate time to be alone with the

child after the child has died

2. Allowing parents to hold the child while life support is discontinued

3. Providing a peaceful, dignified bedside scene for family members

once the child has died

4. Having the code status of the child clearly described in the chart

5. Teaching families how to act around the dying child, such as,

“She can still hear. . . . It’s okay to talk to her”

6. Physicians who are compassionate, but very clear about prognosis

7. Having the physicians involved in a child’s care agree about the

direction care should go

8. Understanding and supporting a family’s religious beliefs

9. Having a coworker tell you, “You did all you could for that child,”

or some other words of support after a child has died

10. Physician meeting in person with the child’s family after the child’s

death to offer support and validate that all possible care was given

11. Having a unit schedule that allows for continuity of care for the

dying child by the same nurses

12. Having child’s family members accept that the child is dying

13. A unit designed so that the child’s family has a place to grieve in

private

14. Having enough time to prepare the family for the expected death

of the child

15. Having the family physically help care for the child

16. Having a support person outside the work setting who will listen

to the nurse after the death of a child

17. Having a single family member be the designated contact person

for all other family members regarding patient information

18. Bereavement debriefing sessions to discuss how to remember/

honor the child

19. Nurse having had experience with the death of a member of the

nurse’s family

21.15

18.47

18.14

17.63

16.40

14.70

14.70

14.24

13.48

12.80

12.64

12.13

11.86

11.76

10.54

10.52

10.51

7.57

7.26

Rank

1

2

3

4

5

9

8

7

6

11

10

14

16

13

12

15

17

19

18

SD

0.78

0.91

0.90

1.15

0.92

0.96

0.98

1.01

1.20

1.33

1.09

0.79

1.48

0.87

1.14

1.50

1.10

1.36

1.03

Mean

4.49

3.98

3.96

3.85

3.84

3.14

3.21

3.44

3.50

2.95

2.98

2.72

2.66

2.76

2.84

2.69

2.52

2.17

2.42

Rank

1

3

6

5

10

2

4

14

16

9

12

8

7

11

17

15

13

18

19

SD

0.53

0.59

0.65

0.77

0.80

0.60

0.66

0.84

1.19

0.81

0.88

0.70

0.70

0.75

1.19

1.14

0.95

1.17

1.30

Mean

4.71

4.64

4.58

4.58

4.27

4.68

4.58

4.14

3.85

4.34

4.24

4.46

4.46

4.26

3.71

3.91

4.17

3.49

3.00

Behavior FrequencybIntensitya

Perceived

supportive

behavior

magnitudec

a Response choices were 0, not a help, to 5, extremely helpful.

b Response choices were 0, never occurs, to 5, always occurs.

c Mean intensity multiplied by mean frequency.

548 AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

Parents need reas-

surance that limit-

ing life-sustaining

treatment does not

mean limiting care.

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

palliative and curative therapies beginning at diagno-

sis so no delay occurs in establishing either type of

therapy and respite care for children and children’s

families who are going through such a difficult process.

Nurse’s Opinions Not Valued. Although Miller et al33

reported that most research findings suggest nurses

have a limited role in end-of-life

decision making and care planning,

nurses are often the first to be aware

of the transition from potential

recovery to a realization that curative

efforts most likely are futile.24 Critical

care nurses play a pivotal role in cli-

nician- family communication in the

ICU and may have valuable insights

into the progress of a disease, the

families’ perceptions and wishes,

and the families’ level of under-

standing and unique needs. Nurses

are an important part of the health

care team. More importantly, families rate nurses’

communication skills as one of the most important

skills of ICU clinicians.19

Lowest Scoring Obstacles. Nurses believing that

life-saving measures or treatments are stopped too

soon was the lowest scoring obstacle. Possibly the

nurses in our sample believe that stopping treatment

too soon does not often happen, or perhaps the

impact of this obstacle was low. Solomon et al26

reported that the number of physicians and nurses

who were concerned about the provision of overly

burdensome treatment was 4 times greater than the

number who were concerned about undertreatment.

Another low scoring item was nurses getting

vague orders, such as “titrate to effect” for pain med-

ications. This score may have been low because nurses

feel competent and actually prefer

being able to decide how much pain

medication to give dying children.

Feudtner et al34 found that nurses

felt most competent about pain

management and least competent

about talking with children and the

children’s families about dying. Of

note, nurses in the future should

receive fewer titrate-to-effect orders

for pain medication because cur-

rent Joint Commission guidelines35

state that all medication orders must

include “the degree of accuracy,

completeness, and discrimination necessary for

their intended use.” Thus, physicians are required

to order specific dosages and frequencies of med-

ications, and a nurse who determines dosages and

parents can make decisions for continuation or with-

drawal of treatment. Robichaux and Clark24 wrote of

the need for nurses to protect and oftentimes be the

voice of the patient in order to prevent further tech-

nological intrusion. The real choice may not be

between life or death, but how the child will live

until death occurs.20 Nurses have acknowledged that

although mechanical ventilation is often associated

with the breath of life, use of this technology can

also extend suffering. In a study27 with critical care

nurses on end-of-life care, a participant stated, “We

[nurses] are trapped between technology and reality.”

Parents need reassurance that limiting life-

sustaining treatment does not mean limiting care.25

Ideally, parents should be educated that withdrawal

of aggressive therapies is not seen as surrendering

to death or abandoning hope. Parents should have

an understanding of what is best for the child and

what the child would want, if she or he could com-

municate, should curative efforts be unsuccessful.

Brandon et al28 found that children who died

in critical care areas were more likely to have experi-

enced withdrawal of respiratory or medical support

as end-of-life interventions, whereas children who

died in intermediate units were more likely to have a

do-not-resuscitate order, including no use of endo-

tracheal intubation or use of only drugs to resusci-

tate the child if he or she stopped breathing or the

heart stopped. These findings partly reflect the fact

that respiratory compromise requiring endotracheal

intubation is an intervention reserved for critical care

settings and that ICUs have unique and often chal-

lenging issues associated with ethical end-of-life care.

The finding that most children die in the ICU may

indicate that hospitalized children are receiving more

complex medical treatments than can be provided

on general pediatric units, and once therapy is initi-

ated, discontinuing it is often difficult.25,29

Discontinuity of Care Between Interdisciplinary Team

Members. Frustration occurs when providers do not

share the same perspectives and goals for a patient.

Having even a single physician unable to recognize

that a child is terminal can give the child’s family

false hope. Having medical subspecialists contradict

one another creates confusion for a patient’s family

and may result in digression when time is critical.

When a patient is not correctly recognized as termi-

nal, curative regimens take precedence and a child’s

unnecessary suffering may be prolonged.19

Many nurses in our study commented on the

need for early recognition of likely death rather

than waiting until a child starts to decompensate

dramatically before palliative care is initiated. Cur-

rent research30-32 supports a coexistent approach with

www.ajcconline.org AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6549

The supportive

behavior with the

greatest impact

was allowing fam-

ily members ade-

quate time with th

child after the

child has died.

Further research

is needed to

decrease highly

rated obstacles

and to continue

to support highly

rated supportive

behaviors.

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

sis so no delay occurs in establishing either type of

therapy and respite care for children and children’s

families who are going through such a difficult process.

Nurse’s Opinions Not Valued. Although Miller et al33

reported that most research findings suggest nurses

have a limited role in end-of-life

decision making and care planning,

nurses are often the first to be aware

of the transition from potential

recovery to a realization that curative

efforts most likely are futile.24 Critical

care nurses play a pivotal role in cli-

nician- family communication in the

ICU and may have valuable insights

into the progress of a disease, the

families’ perceptions and wishes,

and the families’ level of under-

standing and unique needs. Nurses

are an important part of the health

care team. More importantly, families rate nurses’

communication skills as one of the most important

skills of ICU clinicians.19

Lowest Scoring Obstacles. Nurses believing that

life-saving measures or treatments are stopped too

soon was the lowest scoring obstacle. Possibly the

nurses in our sample believe that stopping treatment

too soon does not often happen, or perhaps the

impact of this obstacle was low. Solomon et al26

reported that the number of physicians and nurses

who were concerned about the provision of overly

burdensome treatment was 4 times greater than the

number who were concerned about undertreatment.

Another low scoring item was nurses getting

vague orders, such as “titrate to effect” for pain med-

ications. This score may have been low because nurses

feel competent and actually prefer

being able to decide how much pain

medication to give dying children.

Feudtner et al34 found that nurses

felt most competent about pain

management and least competent

about talking with children and the

children’s families about dying. Of

note, nurses in the future should

receive fewer titrate-to-effect orders

for pain medication because cur-

rent Joint Commission guidelines35

state that all medication orders must

include “the degree of accuracy,

completeness, and discrimination necessary for

their intended use.” Thus, physicians are required

to order specific dosages and frequencies of med-

ications, and a nurse who determines dosages and

parents can make decisions for continuation or with-

drawal of treatment. Robichaux and Clark24 wrote of

the need for nurses to protect and oftentimes be the

voice of the patient in order to prevent further tech-

nological intrusion. The real choice may not be

between life or death, but how the child will live

until death occurs.20 Nurses have acknowledged that

although mechanical ventilation is often associated

with the breath of life, use of this technology can

also extend suffering. In a study27 with critical care

nurses on end-of-life care, a participant stated, “We

[nurses] are trapped between technology and reality.”

Parents need reassurance that limiting life-

sustaining treatment does not mean limiting care.25

Ideally, parents should be educated that withdrawal

of aggressive therapies is not seen as surrendering

to death or abandoning hope. Parents should have

an understanding of what is best for the child and

what the child would want, if she or he could com-

municate, should curative efforts be unsuccessful.

Brandon et al28 found that children who died

in critical care areas were more likely to have experi-

enced withdrawal of respiratory or medical support

as end-of-life interventions, whereas children who

died in intermediate units were more likely to have a

do-not-resuscitate order, including no use of endo-

tracheal intubation or use of only drugs to resusci-

tate the child if he or she stopped breathing or the

heart stopped. These findings partly reflect the fact

that respiratory compromise requiring endotracheal

intubation is an intervention reserved for critical care

settings and that ICUs have unique and often chal-

lenging issues associated with ethical end-of-life care.

The finding that most children die in the ICU may

indicate that hospitalized children are receiving more

complex medical treatments than can be provided

on general pediatric units, and once therapy is initi-

ated, discontinuing it is often difficult.25,29

Discontinuity of Care Between Interdisciplinary Team

Members. Frustration occurs when providers do not

share the same perspectives and goals for a patient.

Having even a single physician unable to recognize

that a child is terminal can give the child’s family

false hope. Having medical subspecialists contradict

one another creates confusion for a patient’s family

and may result in digression when time is critical.

When a patient is not correctly recognized as termi-

nal, curative regimens take precedence and a child’s

unnecessary suffering may be prolonged.19

Many nurses in our study commented on the

need for early recognition of likely death rather

than waiting until a child starts to decompensate

dramatically before palliative care is initiated. Cur-

rent research30-32 supports a coexistent approach with

www.ajcconline.org AA JJCCCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2010, Volume 19, No. 6549

The supportive

behavior with the

greatest impact

was allowing fam-

ily members ade-

quate time with th

child after the

child has died.

Further research

is needed to

decrease highly

rated obstacles

and to continue

to support highly

rated supportive

behaviors.

by AACN on September 7, 2018http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

frequencies of medications may be practicing out-

side the nurse’s licensure.

Supportive Behaviors

PSBM scores for supportive behaviors were much

higher than POM scores were because the highest

scoring behaviors were usually under a nurse’s con-

trol and thus were perceived as very helpful. The 3

PSBM items with the highest scores are interrelated

and occur after a child’s death.

Top 3 Supportive Behaviors. Allowing family

members adequate time to be alone with a child

after the child has died was also the top supportive

behavior in other studies9,11,12of nurses’ perspectives

in end-of-life care. Adequate time alone indicates

respect for the parent-child relation-

ship, because the grieving process

should not be rushed. Nurses appar-

ently appreciate being able to offer

this time alone to children’s families.

The second highest rated sup-

portive behavior was allowing par-

ents to hold the child while life

support was discontinued, another

element within a nurse’s control.

Providing support to families around

the time of death may positively

affect long- term bereavement out-

comes for them for years. Holding

their child one last time would be a

valuable memory for parents and

may be important in the grieving process. This con-

trol of the environment at the time of death is also

related to the third highest rated supportive behav-

ior: providing a peaceful, dignified bedside scene

for family members once the child has died.

Physicians’ Involvement. Four other highly rated

supportive behaviors were associated with physicians’

actions. Having physicians provide a clear code status

and being clear about a child’s diagnosis were per-

ceived as very supportive behaviors in end-of-life care.

Physicians who agreed with a child’s prognosis and

who told the family that all possible care was done

for the child were also perceived as very supportive.

These highly ranked items indicate the need for a

collaborative, unified, interdisciplinary end-of-life team.

Andresen et al36 reported that physicians were more

likely to talk to a child’s family about decision making

at the end of life, whereas nurses were more likely

to be involved in talking about sibling, psychosocial,

and religious issues. A pooled, collective effort of all

health care team members, with consideration of their

opinions and abilities, is needed to help alleviate suf-

fering when a child dies.

Nurse Having Had Experience With the Death of a

Member of the Nurse’s Family. Although the item “nu

having had experience with the death of a member o

the nurse’s family” scored in the top 10 in other stud

ies of nurses’ perceptions of end-of-life care,9,11it was

the lowest scoring supportive behavior in our study.

Perhaps the death of a child differs greatly from the

death of an adult family member and presents a diffe

ent set of psychological and social issues. Other low

scoring supportive behaviors included bereavement

debriefing sessions to discuss how to remember/hono

the child and having a single family member as the

designated contact person for all other family mem-

bers regarding patient information.

Limitations

We did not distinguish between neonatal and

PICU nurses in this study; rather, we focused on

pediatric critical care nurses working in acute care.

Differences between ICU and non-ICU staff mem-

bers’ perceptions of end-of-life care were reported by

Davies et al.4 In that study, time constraints, staff

shortages, and parental discomfort about withhold-

ing/ withdrawing medical nutrition or hydration

were reported more frequently by non-ICU staff than

by ICU staff. Further research may be indicated to

differentiate neonatal nurses’ perceptions of barriers

and supportive behaviors from those of pediatric

nurses. Also, our sample consisted of nurses from

only a single specialty nursing organization, AACN.

How nurses from exclusively pediatric organizations

perceive end-of-life care is not known. Future researc

on these nurses’ perceptions is planned.

Implications

Pediatric nurses play a vital role in caring for

dying children and the children’s families. Parents

of children who died in the ICU have reported that

they relied more heavily on nursing professionals

than on the parents’ own family members when

making end-of-life decisions.37

Improving Communication

Overcoming communication barriers with the

family and within the interdisciplinary team can

positively affect end-of-life care. Better communica-

tion would help parents confront the difficult situa-

tions they face and would better prepare families