Effectiveness of Interventions for University Student Health Behaviors

VerifiedAdded on 2022/12/21

|10

|9819

|1

Report

AI Summary

This document presents a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions aimed at improving physical activity, diet, and weight-related behaviors among university and college students. The study analyzed 41 studies published between January 1970 and April 2014, finding that 34 reported significant improvements in key outcomes. The review examined the effectiveness of interventions on physical activity, nutrition, and weight loss. Meta-analysis showed significant increases in moderate physical activity within intervention groups. While many studies improved nutrition outcomes, only a few found significant weight reduction. The review highlights tertiary institutions as appropriate settings for lifestyle interventions, emphasizing the need for further research to improve these strategies. The review uses the PRISMA reporting guidelines and assesses the risk of bias and study quality. This is a valuable resource for students studying public health, nutrition, and related fields, available on Desklib for further study and research.

REV I E W Open Access

Effectiveness of interventions targeting physica

activity,nutrition and healthy weight for

university and college students:a systematic

review and meta-analysis

Ronald C Plotnikoff1,2*

, Sarah A Costigan1,2

, Rebecca L Williams1,3

, Melinda J Hutchesson1,3

, Sarah G Kennedy1,2

,

Sara L Robards1,2

, Jennifer Allen2

, Clare E Collins1,3

, Robin Callister1,4

and John Germov5

Abstract

To examine the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving physicalactivity,diet,and/or weight-related

behaviors amongst university/college students.Five online databases were searched (January 1970 to April2014).

Experimentalstudy designs were eligible for inclusion.Data extraction was performed by one reviewer using a

standardized form developed by the researchers and checked by a second reviewer.Data were described in a

narrative synthesis and meta-analyses were conducted when appropriate.Study quality was also established.

Forty-one studies were included;of these,34 reported significant improvements in one of the key outcomes.Of

the studies examining physicalactivity 18/29 yielded significant results,with meta-analysis demonstrating significant

increases in moderate physicalactivity in intervention groups compared to control.Of the studies examining

nutrition,12/24 reported significantly improved outcomes;only 4/12 assessing weightloss outcomes found

significantweightreduction.This appears to be the firstsystematic review of physical activity,diet and weight loss

interventions targeting university and college students.Tertiary institutions are appropriate settings for implementing

and evaluating lifestyle interventions,however more research is needed to improve such strategies.

Keywords: University,College,Tertiary education institutions,University students,Health promotion,Health behavior,

Healthy universities,Physical activity,Exercise,Diet,Nutrition,Weight loss

Introduction

Physical inactivity and poor dietary-intake are related be-

haviorsthat impacton health and wellbeing and the

maintenance of a healthy weight.These behaviors under-

pin risk of lifestyle related non-communicable conditions

[1].Risk for ischaemic heart disease,stroke,type two dia-

betes,osteoporosis,variouscancersand depression are

linked by behavioraland biomedicalhealth determinants

such asphysicalinactivity,poor dietary behaviorsand

overweight/obesity [2].

The health benefits of engaging in regular physicalac-

tivity are wellestablished foradults[3]. Strategiesto

promotephysicalactivityhavebecomean important

public health approach for the prevention of chronic dis-

eases [4]. The prevalence of achieving physical activity rec

ommendations declines rapidly between the ages of18

and 24 [5] when many young people are undertaking ter-

tiary education [6-8].For instance,in the United States

nearly half of all university students are not achieving rec-

ommended levels ofphysicalactivity [9].Australian data

in the ≥18 year age group indicate 66.9% are sedentary or

have low levels of physical activity during 2011-2012 [10].

Similarly in the United Kingdom,73% of male and 79% of

female university students do notmeetphysicalactivity

guidelines [6]. Further, Irwin [8] suggests that students liv-

ing on campus are less likely to be active, and thus may be

at greater risk of poor health.

* Correspondence:Ron.plotnikoff@newcastle.edu.au

1Priority Research Centre for PhysicalActivity and Nutrition,University of

Newcastle,Callaghan Campus,Newcastle,NSW,Australia

2Schoolof Education,Faculty of Education and Arts,University of Newcastle,

Callaghan Campus,Newcastle,NSW,Australia

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2015 Plotnikoff et al.;licensee BioMed Central.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided the originalwork is properly credited.The Creative Commons Public Domain

Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,

unless otherwise stated.

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition

and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45

DOI10.1186/s12966-015-0203-7

Effectiveness of interventions targeting physica

activity,nutrition and healthy weight for

university and college students:a systematic

review and meta-analysis

Ronald C Plotnikoff1,2*

, Sarah A Costigan1,2

, Rebecca L Williams1,3

, Melinda J Hutchesson1,3

, Sarah G Kennedy1,2

,

Sara L Robards1,2

, Jennifer Allen2

, Clare E Collins1,3

, Robin Callister1,4

and John Germov5

Abstract

To examine the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving physicalactivity,diet,and/or weight-related

behaviors amongst university/college students.Five online databases were searched (January 1970 to April2014).

Experimentalstudy designs were eligible for inclusion.Data extraction was performed by one reviewer using a

standardized form developed by the researchers and checked by a second reviewer.Data were described in a

narrative synthesis and meta-analyses were conducted when appropriate.Study quality was also established.

Forty-one studies were included;of these,34 reported significant improvements in one of the key outcomes.Of

the studies examining physicalactivity 18/29 yielded significant results,with meta-analysis demonstrating significant

increases in moderate physicalactivity in intervention groups compared to control.Of the studies examining

nutrition,12/24 reported significantly improved outcomes;only 4/12 assessing weightloss outcomes found

significantweightreduction.This appears to be the firstsystematic review of physical activity,diet and weight loss

interventions targeting university and college students.Tertiary institutions are appropriate settings for implementing

and evaluating lifestyle interventions,however more research is needed to improve such strategies.

Keywords: University,College,Tertiary education institutions,University students,Health promotion,Health behavior,

Healthy universities,Physical activity,Exercise,Diet,Nutrition,Weight loss

Introduction

Physical inactivity and poor dietary-intake are related be-

haviorsthat impacton health and wellbeing and the

maintenance of a healthy weight.These behaviors under-

pin risk of lifestyle related non-communicable conditions

[1].Risk for ischaemic heart disease,stroke,type two dia-

betes,osteoporosis,variouscancersand depression are

linked by behavioraland biomedicalhealth determinants

such asphysicalinactivity,poor dietary behaviorsand

overweight/obesity [2].

The health benefits of engaging in regular physicalac-

tivity are wellestablished foradults[3]. Strategiesto

promotephysicalactivityhavebecomean important

public health approach for the prevention of chronic dis-

eases [4]. The prevalence of achieving physical activity rec

ommendations declines rapidly between the ages of18

and 24 [5] when many young people are undertaking ter-

tiary education [6-8].For instance,in the United States

nearly half of all university students are not achieving rec-

ommended levels ofphysicalactivity [9].Australian data

in the ≥18 year age group indicate 66.9% are sedentary or

have low levels of physical activity during 2011-2012 [10].

Similarly in the United Kingdom,73% of male and 79% of

female university students do notmeetphysicalactivity

guidelines [6]. Further, Irwin [8] suggests that students liv-

ing on campus are less likely to be active, and thus may be

at greater risk of poor health.

* Correspondence:Ron.plotnikoff@newcastle.edu.au

1Priority Research Centre for PhysicalActivity and Nutrition,University of

Newcastle,Callaghan Campus,Newcastle,NSW,Australia

2Schoolof Education,Faculty of Education and Arts,University of Newcastle,

Callaghan Campus,Newcastle,NSW,Australia

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2015 Plotnikoff et al.;licensee BioMed Central.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided the originalwork is properly credited.The Creative Commons Public Domain

Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,

unless otherwise stated.

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition

and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45

DOI10.1186/s12966-015-0203-7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Dietary intake patterns that align with nationaldietary

guidelines are associated with reduced risk of developing

chronic conditions [11,12],however recent research sug-

geststertiary studentsdo not achieve these guidelines

[13-15].For instance,in the United States,university and

college students have sub-optimal dietary habits compared

to such recommendations [16].Similarly,Australian ter-

tiary studentsfail to consume the recommended daily

servings of fruit (50%) and vegetables (90%) [2]. While stu-

dents from the UK failto consume the recommended

daily intake of fruit and vegetables (88.7% and 83.5%,re-

spectively) [17].

Commencing college/university is often associated with

students having more autonomy over their dietary choices

(e.g.,food purchasing and preparation).Due to life stage,

students may not consider the risk of developing chronic

diseases when making food choices [18].Specifically,fac-

tors such as cost,skipping meals,inadequate variety of

foods,snacking,and frequent consumption offast foods

may increase students’risk of poor health [19].Indeed,

studies have reported that considerable weight gain occurs

during college/university [20,21].The associated food se-

lection skills and habits have long-term health impacts

[22].Further,within US institutions a great proportion of

freshmen (first year) live in college resident halls,which

provide commercially prepared food,take-away and pre-

prepared meals.This environment may further contribute

to subsequent poor food purchasing and preparation be-

haviors. Along with these dietary behaviors, physical activity

participation also declinesin university and college stu-

dents, which may be due to increased sedentary time when

studying and during examination periods [23].

Given the lack of physical activity and healthy eating it

is not surprising that the prevalence of overweight/obesity

has reached epidemic proportions in young adults.In the

USA, the age range of greatest increase in obesity (7.1% to

12.1%) is among young adults aged 18–29 years [7].In-

deed,late adolescence and early adulthood appear to be

significant periods oftransition,highlighting the import-

ance ofunderstanding factors such as attitudes towards

and knowledge ofhealth benefits,as these may be associ-

ated with physical activity levels, dietary behavior and obes-

ity prevalence [24].Improvements to lifestyle behaviors can

reduce or preventthe occurrence ofnon-communicable

diseases;therefore strategies to foster healthier lifestyles in

the working age population are essential.

Higher education institutions are an appropriate set-

ting to promote healthy lifestyles.First,universities and

colleges have the potentialto engage large numbers of

students in behavior change interventions,and the esti-

mated number of individuals participating in higher educa-

tion is continuing to rise [25].It is projected that student

numbers in American collegeswill reach 22 million in

2014,and that the number of students enrolled in higher

education worldwide willreach 262 million by 2025,a

marked increase from 178 million in 2010 [26].Second,

higher education institutions have access to a large propor

tion of students living away from home for the first time,

and have the capacity to provide supportand establish

healthy behavioralpatterns that may continue throughout

the lifespan.Third,universities and colleges are regarded

as organizationsthat follow high standardsof practice

which can establish research-based examplesfor sur-

rounding communities to follow.This allows for the op-

portunity and responsibility to develop and implement the

best available research evidence,and to set a benchmark

for other groups to follow [27].Universities and colleges

have a range of facilities, resources and qualified staff, com

monly including health professionals,idealfor implement-

ing initiatives to target lifestyle-related health issues. Finall

the possibility that exists for students to deliver initiatives

as a part oftheir study/training to become health profes-

sionals adds to the promise for tertiary education institu-

tions as ideal settings for promoting healthy lifestyles.

Evidencesuggeststhat intervention strategieshave

been successfulfor students in the highereducational

setting [1,5],particularly interventions that seek to em-

power individuals to achieve their fullpotentialthrough

creating learning and supportto improve health,well-

being and sustainability within the community [28].In

addition,whilstthe primary advantage ofimplementing

health promotion programs is to reduce individuals’ health

risks,the benefits to higher education institutions in attri-

tion,retention and academic performance are also poten-

tial gains [29].Although a recentreview examining the

effectivenessof interventionstargeting health behaviors

(physicalactivity,nutrition and healthy weight)amongst

university staff has been conducted [22],it appears that a

review investigating the effectiveness ofhealth behavior

interventions on these health behaviors/issues for univer-

sity students has not yet been performed.

Objective

The objective of this paper is to systematically review the

best available evidence regarding the impact of health be-

havior interventions to improve physical activity, diet and/

or weight outcomes and targeted at students enrolled in

tertiary education institutions.

Review

Methods

Data source

A structured electronic search employing PRISMA report-

ing guidelines [30] was performed on health-focused inter-

vention studies carried outin tertiary leveleducational

institutions and published between January 1970 and April

2014.MEDLINE with full text,PsychINFO,CINAHL,

ERIC and ProQuest were systematicallysearched

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 2 of 10

guidelines are associated with reduced risk of developing

chronic conditions [11,12],however recent research sug-

geststertiary studentsdo not achieve these guidelines

[13-15].For instance,in the United States,university and

college students have sub-optimal dietary habits compared

to such recommendations [16].Similarly,Australian ter-

tiary studentsfail to consume the recommended daily

servings of fruit (50%) and vegetables (90%) [2]. While stu-

dents from the UK failto consume the recommended

daily intake of fruit and vegetables (88.7% and 83.5%,re-

spectively) [17].

Commencing college/university is often associated with

students having more autonomy over their dietary choices

(e.g.,food purchasing and preparation).Due to life stage,

students may not consider the risk of developing chronic

diseases when making food choices [18].Specifically,fac-

tors such as cost,skipping meals,inadequate variety of

foods,snacking,and frequent consumption offast foods

may increase students’risk of poor health [19].Indeed,

studies have reported that considerable weight gain occurs

during college/university [20,21].The associated food se-

lection skills and habits have long-term health impacts

[22].Further,within US institutions a great proportion of

freshmen (first year) live in college resident halls,which

provide commercially prepared food,take-away and pre-

prepared meals.This environment may further contribute

to subsequent poor food purchasing and preparation be-

haviors. Along with these dietary behaviors, physical activity

participation also declinesin university and college stu-

dents, which may be due to increased sedentary time when

studying and during examination periods [23].

Given the lack of physical activity and healthy eating it

is not surprising that the prevalence of overweight/obesity

has reached epidemic proportions in young adults.In the

USA, the age range of greatest increase in obesity (7.1% to

12.1%) is among young adults aged 18–29 years [7].In-

deed,late adolescence and early adulthood appear to be

significant periods oftransition,highlighting the import-

ance ofunderstanding factors such as attitudes towards

and knowledge ofhealth benefits,as these may be associ-

ated with physical activity levels, dietary behavior and obes-

ity prevalence [24].Improvements to lifestyle behaviors can

reduce or preventthe occurrence ofnon-communicable

diseases;therefore strategies to foster healthier lifestyles in

the working age population are essential.

Higher education institutions are an appropriate set-

ting to promote healthy lifestyles.First,universities and

colleges have the potentialto engage large numbers of

students in behavior change interventions,and the esti-

mated number of individuals participating in higher educa-

tion is continuing to rise [25].It is projected that student

numbers in American collegeswill reach 22 million in

2014,and that the number of students enrolled in higher

education worldwide willreach 262 million by 2025,a

marked increase from 178 million in 2010 [26].Second,

higher education institutions have access to a large propor

tion of students living away from home for the first time,

and have the capacity to provide supportand establish

healthy behavioralpatterns that may continue throughout

the lifespan.Third,universities and colleges are regarded

as organizationsthat follow high standardsof practice

which can establish research-based examplesfor sur-

rounding communities to follow.This allows for the op-

portunity and responsibility to develop and implement the

best available research evidence,and to set a benchmark

for other groups to follow [27].Universities and colleges

have a range of facilities, resources and qualified staff, com

monly including health professionals,idealfor implement-

ing initiatives to target lifestyle-related health issues. Finall

the possibility that exists for students to deliver initiatives

as a part oftheir study/training to become health profes-

sionals adds to the promise for tertiary education institu-

tions as ideal settings for promoting healthy lifestyles.

Evidencesuggeststhat intervention strategieshave

been successfulfor students in the highereducational

setting [1,5],particularly interventions that seek to em-

power individuals to achieve their fullpotentialthrough

creating learning and supportto improve health,well-

being and sustainability within the community [28].In

addition,whilstthe primary advantage ofimplementing

health promotion programs is to reduce individuals’ health

risks,the benefits to higher education institutions in attri-

tion,retention and academic performance are also poten-

tial gains [29].Although a recentreview examining the

effectivenessof interventionstargeting health behaviors

(physicalactivity,nutrition and healthy weight)amongst

university staff has been conducted [22],it appears that a

review investigating the effectiveness ofhealth behavior

interventions on these health behaviors/issues for univer-

sity students has not yet been performed.

Objective

The objective of this paper is to systematically review the

best available evidence regarding the impact of health be-

havior interventions to improve physical activity, diet and/

or weight outcomes and targeted at students enrolled in

tertiary education institutions.

Review

Methods

Data source

A structured electronic search employing PRISMA report-

ing guidelines [30] was performed on health-focused inter-

vention studies carried outin tertiary leveleducational

institutions and published between January 1970 and April

2014.MEDLINE with full text,PsychINFO,CINAHL,

ERIC and ProQuest were systematicallysearched

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 2 of 10

[22,31-34].The following search terms were used:(uni-

versity OR college) AND (health promotion OR interven-

tion OR program OR education)AND (behaviorOR

physicalactivity OR exercise OR dietOR nutrition OR

weight).Published articles in peer reviewed journals were

considered for the review. Bibliographies of selected studies

were also considered.Only manuscripts written in English

were considered for the review.Two reviewers independ-

ently assessed articles for study inclusion,initially based on

the title and abstract.Full texts were then retrieved and

assessed for inclusion.A third reviewer was used to make

the final decision in the case of discrepancies.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Type of participants

Any study includingstudentsattendinginstitutions

within the tertiary education sector was included.If other

types ofparticipants,e.g.,staffwere also recruited,only

students’data were extracted.

Type of intervention (s)/phenomena of interest

Interventions deemed eligible for inclusion had to be im-

plemented within a tertiary education setting and have

the aim ofimproving physicalactivity and/or dietary in-

take and/or weight.Interventions ofall lengths were ac-

cepted for inclusion within the review.

Type of studies

All quantitative study designs (including randomized con-

trolled trials,non-randomized experimentaltrials,pre-

post with no control group) were eligible for inclusion.

Type of outcomes

This review considered the following outcome measures spe-

cific to the health behavior targeted (an increase in know-

ledge among participants was not a sufficient outcome):

i) Physical activity related outcomes:steps per day,

time spent undertaking vigorous and/or moderate

physical activity, VO2 max,muscular strength/

endurance,energy expenditure,flexibility;

ii) Nutrition outcomes:energy intake,macronutrient

composition,core food group consumption,diet

quality;and,

iii) Weight related outcomes:weight (kg or lbs),body

mass index (kg/m2) (BMI),waist circumference

(cm),% weight loss,% body fat,waist-to-hip ratio

(WHR).

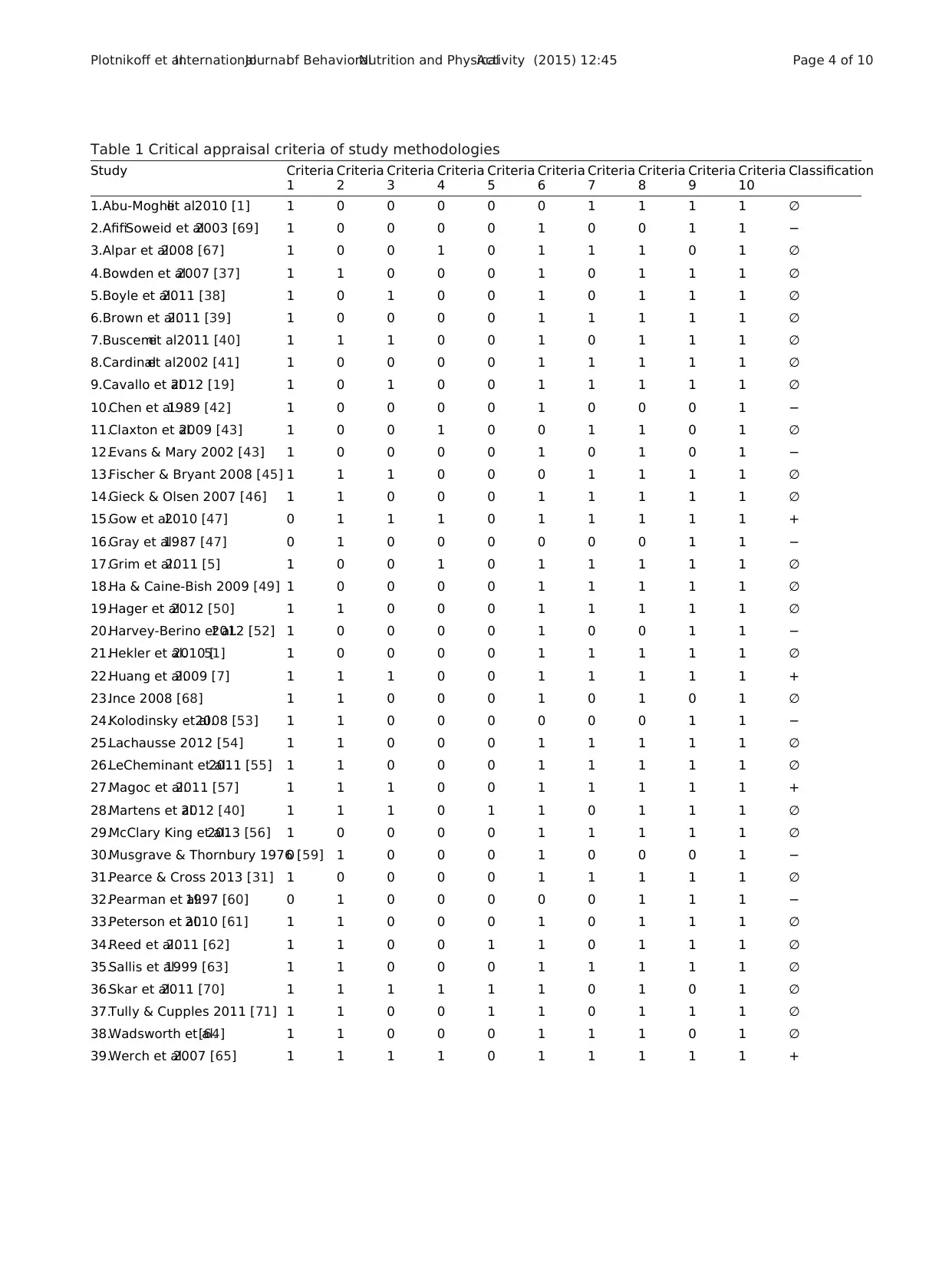

Risk of bias

Risk ofbias was assessed for allincluded studies by two

independentreviewers (SK,SR) (a third reviewer[SC]

was consulted and consensus reached in the event ofa

disagreement)using the Academyof Nutrition and

Dietetics Quality Criteria Checklist: Primary Research tool

assessing 10 criteria [35].These criteria included whether:

(1) The study clearly stated the research question;(2) If

the selection of participants was free from bias;(3) If the

study groups were comparable;(4) Description of method

of handling withdrawals;(5) Use ofblinding;(6) Detailed

description ofinterventions and comparisons;(7) Clear

definition ofoutcomes and valid and reliable measure-

ments;(8) Appropriate statisticalanalysis;(9) Consider-

ation oflimitations;and,(10)Likelihood ofbias due to

funding.Study quality was classed as positive if criteria 2,

3, 6 and 7,as wellas one other validity criteria question

were scored with a ‘yes’,neutralif criteria points 2,3 6

and 7 did not score a ‘yes’,or negative if more than six of

the validity criteria questions were answered with a ‘no’.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by two reviewers (SK,SR)

using a standardized form developed by the researchers.

The data extraction consisted of11 dimensions;country

of origin,target sample and size,participants’mean age,

duration of study,intervention description,participant re-

tention,health behavior,study design,outcomes,results,

and significance of results (see Additional file 1:Table S1,

Additionalfile 2:Table S2,and Table 1).Extraction was

checked foraccuracy and consistency by a third re-

viewer (SC).

Meta-analysis

Results were pooled in meta-analysis ifthey were avail-

able as finalvalues atpost-intervention,the number of

participants was recorded and interventions were suffi-

cientlysimilarfor comparison.If standard deviations

were notavailable,but other statistics (e.g.,95% CIor

standard errors) were available,they were converted ac-

cording to thecalculationsoutlined in theCochrane

Handbook for Systematic Reviews ofInterventions [36].

Heterogeneity was assessed using chi-squared with sig-

nificant heterogeneity assigned at a P value < 0.10.If sig-

nificant heterogeneity existed,the random effects model

was used for statistical analysis;if homogenous,the fixed

effect modelwas used.The data from individualstudies

on physicalactivity were combined across studies using

standardized mean difference (SMD)due to the differ-

ences in reported metrics for total, moderate and vigorous

physicalactivity.A unit conversion was not undertaken.

Therefore,the meta-analyticalresults do notreflectthe

specific magnitude of effects for each study, but rather the

extent to which they are more successful against controls.

When a study compared multiple treatment groups with a

single control,the sample size of the controlwas divided

equally across the treatmentgroup arms so the partici-

pants were not counted more than once in the analysis.

All meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 3 of 10

versity OR college) AND (health promotion OR interven-

tion OR program OR education)AND (behaviorOR

physicalactivity OR exercise OR dietOR nutrition OR

weight).Published articles in peer reviewed journals were

considered for the review. Bibliographies of selected studies

were also considered.Only manuscripts written in English

were considered for the review.Two reviewers independ-

ently assessed articles for study inclusion,initially based on

the title and abstract.Full texts were then retrieved and

assessed for inclusion.A third reviewer was used to make

the final decision in the case of discrepancies.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Type of participants

Any study includingstudentsattendinginstitutions

within the tertiary education sector was included.If other

types ofparticipants,e.g.,staffwere also recruited,only

students’data were extracted.

Type of intervention (s)/phenomena of interest

Interventions deemed eligible for inclusion had to be im-

plemented within a tertiary education setting and have

the aim ofimproving physicalactivity and/or dietary in-

take and/or weight.Interventions ofall lengths were ac-

cepted for inclusion within the review.

Type of studies

All quantitative study designs (including randomized con-

trolled trials,non-randomized experimentaltrials,pre-

post with no control group) were eligible for inclusion.

Type of outcomes

This review considered the following outcome measures spe-

cific to the health behavior targeted (an increase in know-

ledge among participants was not a sufficient outcome):

i) Physical activity related outcomes:steps per day,

time spent undertaking vigorous and/or moderate

physical activity, VO2 max,muscular strength/

endurance,energy expenditure,flexibility;

ii) Nutrition outcomes:energy intake,macronutrient

composition,core food group consumption,diet

quality;and,

iii) Weight related outcomes:weight (kg or lbs),body

mass index (kg/m2) (BMI),waist circumference

(cm),% weight loss,% body fat,waist-to-hip ratio

(WHR).

Risk of bias

Risk ofbias was assessed for allincluded studies by two

independentreviewers (SK,SR) (a third reviewer[SC]

was consulted and consensus reached in the event ofa

disagreement)using the Academyof Nutrition and

Dietetics Quality Criteria Checklist: Primary Research tool

assessing 10 criteria [35].These criteria included whether:

(1) The study clearly stated the research question;(2) If

the selection of participants was free from bias;(3) If the

study groups were comparable;(4) Description of method

of handling withdrawals;(5) Use ofblinding;(6) Detailed

description ofinterventions and comparisons;(7) Clear

definition ofoutcomes and valid and reliable measure-

ments;(8) Appropriate statisticalanalysis;(9) Consider-

ation oflimitations;and,(10)Likelihood ofbias due to

funding.Study quality was classed as positive if criteria 2,

3, 6 and 7,as wellas one other validity criteria question

were scored with a ‘yes’,neutralif criteria points 2,3 6

and 7 did not score a ‘yes’,or negative if more than six of

the validity criteria questions were answered with a ‘no’.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by two reviewers (SK,SR)

using a standardized form developed by the researchers.

The data extraction consisted of11 dimensions;country

of origin,target sample and size,participants’mean age,

duration of study,intervention description,participant re-

tention,health behavior,study design,outcomes,results,

and significance of results (see Additional file 1:Table S1,

Additionalfile 2:Table S2,and Table 1).Extraction was

checked foraccuracy and consistency by a third re-

viewer (SC).

Meta-analysis

Results were pooled in meta-analysis ifthey were avail-

able as finalvalues atpost-intervention,the number of

participants was recorded and interventions were suffi-

cientlysimilarfor comparison.If standard deviations

were notavailable,but other statistics (e.g.,95% CIor

standard errors) were available,they were converted ac-

cording to thecalculationsoutlined in theCochrane

Handbook for Systematic Reviews ofInterventions [36].

Heterogeneity was assessed using chi-squared with sig-

nificant heterogeneity assigned at a P value < 0.10.If sig-

nificant heterogeneity existed,the random effects model

was used for statistical analysis;if homogenous,the fixed

effect modelwas used.The data from individualstudies

on physicalactivity were combined across studies using

standardized mean difference (SMD)due to the differ-

ences in reported metrics for total, moderate and vigorous

physicalactivity.A unit conversion was not undertaken.

Therefore,the meta-analyticalresults do notreflectthe

specific magnitude of effects for each study, but rather the

extent to which they are more successful against controls.

When a study compared multiple treatment groups with a

single control,the sample size of the controlwas divided

equally across the treatmentgroup arms so the partici-

pants were not counted more than once in the analysis.

All meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 3 of 10

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

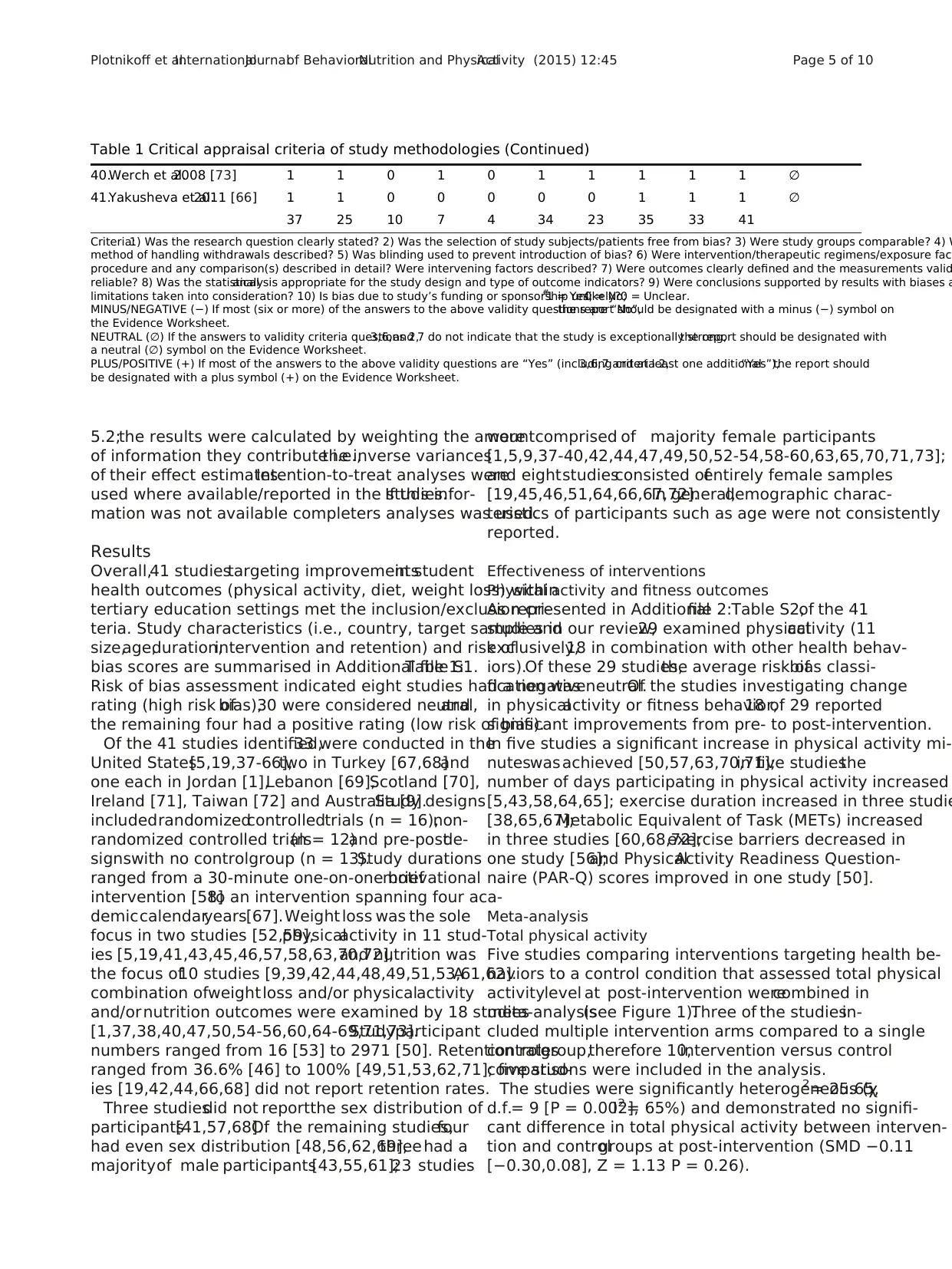

Table 1 Critical appraisal criteria of study methodologies

Study Criteria

1

Criteria

2

Criteria

3

Criteria

4

Criteria

5

Criteria

6

Criteria

7

Criteria

8

Criteria

9

Criteria

10

Classification

1.Abu-Moghliet al.2010 [1] 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 ∅

2.AfifiSoweid et al.2003 [69] 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 −

3.Alpar et al.2008 [67] 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 ∅

4.Bowden et al.2007 [37] 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

5.Boyle et al.2011 [38] 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

6.Brown et al.2011 [39] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

7.Buscemiet al.2011 [40] 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

8.Cardinalet al.2002 [41] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

9.Cavallo et al.2012 [19] 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

10.Chen et al.1989 [42] 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 −

11.Claxton et al.2009 [43] 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 ∅

12.Evans & Mary 2002 [43] 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 −

13.Fischer & Bryant 2008 [45] 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 ∅

14.Gieck & Olsen 2007 [46] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

15.Gow et al.2010 [47] 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 +

16.Gray et al.1987 [47] 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 −

17.Grim et al.2011 [5] 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

18.Ha & Caine-Bish 2009 [49] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

19.Hager et al.2012 [50] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

20.Harvey-Berino et al.2012 [52] 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 −

21.Hekler et al.2010 [51] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

22.Huang et al.2009 [7] 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 +

23.Ince 2008 [68] 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 ∅

24.Kolodinsky et al.2008 [53] 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 −

25.Lachausse 2012 [54] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

26.LeCheminant et al.2011 [55] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

27.Magoc et al.2011 [57] 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 +

28.Martens et al.2012 [40] 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

29.McClary King et al.2013 [56] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

30.Musgrave & Thornbury 1976 [59]0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 −

31.Pearce & Cross 2013 [31] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

32.Pearman et al.1997 [60] 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 −

33.Peterson et al.2010 [61] 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

34.Reed et al.2011 [62] 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

35.Sallis et al.1999 [63] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

36.Skar et al.2011 [70] 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 ∅

37.Tully & Cupples 2011 [71] 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

38.Wadsworth et al.[64] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 ∅

39.Werch et al.2007 [65] 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 +

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 4 of 10

Study Criteria

1

Criteria

2

Criteria

3

Criteria

4

Criteria

5

Criteria

6

Criteria

7

Criteria

8

Criteria

9

Criteria

10

Classification

1.Abu-Moghliet al.2010 [1] 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 ∅

2.AfifiSoweid et al.2003 [69] 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 −

3.Alpar et al.2008 [67] 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 ∅

4.Bowden et al.2007 [37] 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

5.Boyle et al.2011 [38] 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

6.Brown et al.2011 [39] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

7.Buscemiet al.2011 [40] 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

8.Cardinalet al.2002 [41] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

9.Cavallo et al.2012 [19] 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

10.Chen et al.1989 [42] 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 −

11.Claxton et al.2009 [43] 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 ∅

12.Evans & Mary 2002 [43] 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 −

13.Fischer & Bryant 2008 [45] 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 ∅

14.Gieck & Olsen 2007 [46] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

15.Gow et al.2010 [47] 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 +

16.Gray et al.1987 [47] 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 −

17.Grim et al.2011 [5] 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

18.Ha & Caine-Bish 2009 [49] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

19.Hager et al.2012 [50] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

20.Harvey-Berino et al.2012 [52] 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 −

21.Hekler et al.2010 [51] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

22.Huang et al.2009 [7] 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 +

23.Ince 2008 [68] 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 ∅

24.Kolodinsky et al.2008 [53] 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 −

25.Lachausse 2012 [54] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

26.LeCheminant et al.2011 [55] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

27.Magoc et al.2011 [57] 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 +

28.Martens et al.2012 [40] 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

29.McClary King et al.2013 [56] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

30.Musgrave & Thornbury 1976 [59]0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 −

31.Pearce & Cross 2013 [31] 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

32.Pearman et al.1997 [60] 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 −

33.Peterson et al.2010 [61] 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

34.Reed et al.2011 [62] 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

35.Sallis et al.1999 [63] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

36.Skar et al.2011 [70] 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 ∅

37.Tully & Cupples 2011 [71] 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 ∅

38.Wadsworth et al.[64] 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 ∅

39.Werch et al.2007 [65] 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 +

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 4 of 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5.2;the results were calculated by weighting the amount

of information they contribute i.e.,the inverse variances

of their effect estimates.Intention-to-treat analyses were

used where available/reported in the studies.If this infor-

mation was not available completers analyses was used.

Results

Overall,41 studiestargeting improvementsin student

health outcomes (physical activity, diet, weight loss) within

tertiary education settings met the inclusion/exclusion cri-

teria. Study characteristics (i.e., country, target sample and

size,age,duration,intervention and retention) and risk of

bias scores are summarised in Additional file 1:Table S1.

Risk of bias assessment indicated eight studies had a negative

rating (high risk ofbias),30 were considered neutral,and

the remaining four had a positive rating (low risk of bias).

Of the 41 studies identified,33 were conducted in the

United States[5,19,37-66],two in Turkey [67,68]and

one each in Jordan [1],Lebanon [69],Scotland [70],

Ireland [71], Taiwan [72] and Australia [9].Study designs

includedrandomizedcontrolledtrials (n = 16),non-

randomized controlled trials(n = 12)and pre-postde-

signswith no controlgroup (n = 13).Study durations

ranged from a 30-minute one-on-one briefmotivational

intervention [58]to an intervention spanning four aca-

demiccalendaryears[67].Weight loss was the sole

focus in two studies [52,59],physicalactivity in 11 stud-

ies [5,19,41,43,45,46,57,58,63,70,72],and nutrition was

the focus of10 studies [9,39,42,44,48,49,51,53,61,62].A

combination ofweightloss and/or physicalactivity

and/or nutrition outcomes were examined by 18 studies

[1,37,38,40,47,50,54-56,60,64-69,71,73].Studyparticipant

numbers ranged from 16 [53] to 2971 [50]. Retention rates

ranged from 36.6% [46] to 100% [49,51,53,62,71]; five stud-

ies [19,42,44,66,68] did not report retention rates.

Three studiesdid not reportthe sex distribution of

participants[41,57,68].Of the remaining studies,four

had even sex distribution [48,56,62,69],three had a

majorityof male participants[43,55,61];23 studies

were comprised of majority female participants

[1,5,9,37-40,42,44,47,49,50,52-54,58-60,63,65,70,71,73];

and eightstudiesconsisted ofentirely female samples

[19,45,46,51,64,66,67,72].In general,demographic charac-

teristics of participants such as age were not consistently

reported.

Effectiveness of interventions

Physical activity and fitness outcomes

As represented in Additionalfile 2:Table S2,of the 41

studies in our review,29 examined physicalactivity (11

exclusively,18 in combination with other health behav-

iors).Of these 29 studies,the average risk ofbias classi-

fication was neutral.Of the studies investigating change

in physicalactivity or fitness behavior,18 of 29 reported

significant improvements from pre- to post-intervention.

In five studies a significant increase in physical activity mi-

nuteswas achieved [50,57,63,70,71];in five studiesthe

number of days participating in physical activity increased

[5,43,58,64,65]; exercise duration increased in three studie

[38,65,67];Metabolic Equivalent of Task (METs) increased

in three studies [60,68,72];exercise barriers decreased in

one study [56];and PhysicalActivity Readiness Question-

naire (PAR-Q) scores improved in one study [50].

Meta-analysis

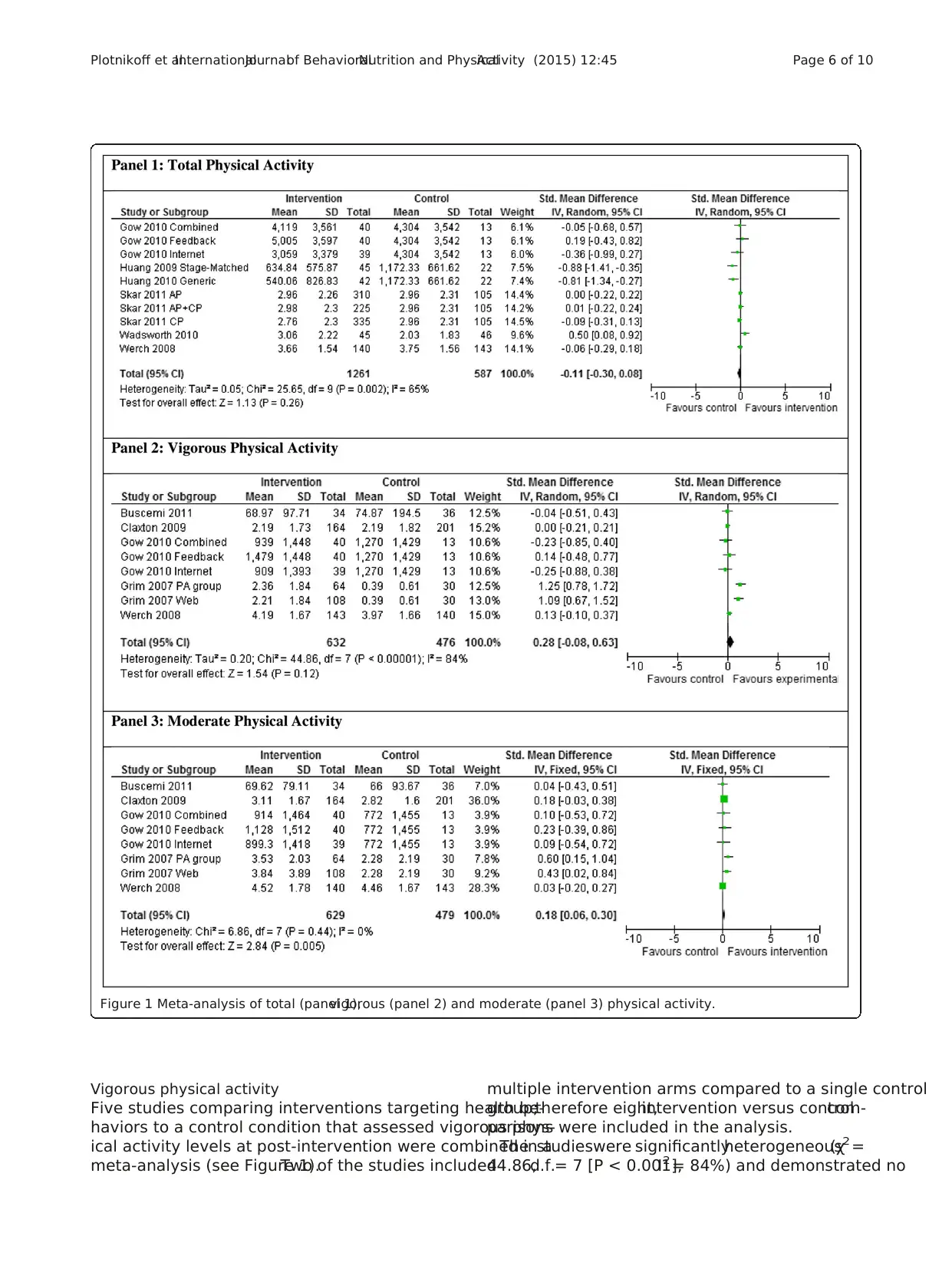

Total physical activity

Five studies comparing interventions targeting health be-

haviors to a control condition that assessed total physical

activitylevel at post-intervention werecombined in

meta-analysis(see Figure 1).Three of the studiesin-

cluded multiple intervention arms compared to a single

controlgroup,therefore 10,intervention versus control

comparisons were included in the analysis.

The studies were significantly heterogeneous (χ2 = 25.65,

d.f.= 9 [P = 0.002],I 2 = 65%) and demonstrated no signifi-

cant difference in total physical activity between interven-

tion and controlgroups at post-intervention (SMD −0.11

[−0.30,0.08], Z = 1.13 P = 0.26).

Table 1 Critical appraisal criteria of study methodologies (Continued)

40.Werch et al.2008 [73] 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

41.Yakusheva et al.2011 [66] 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 ∅

37 25 10 7 4 34 23 35 33 41

Criteria:1) Was the research question clearly stated? 2) Was the selection of study subjects/patients free from bias? 3) Were study groups comparable? 4) W

method of handling withdrawals described? 5) Was blinding used to prevent introduction of bias? 6) Were intervention/therapeutic regimens/exposure fac

procedure and any comparison(s) described in detail? Were intervening factors described? 7) Were outcomes clearly defined and the measurements valid

reliable? 8) Was the statisticalanalysis appropriate for the study design and type of outcome indicators? 9) Were conclusions supported by results with biases a

limitations taken into consideration? 10) Is bias due to study’s funding or sponsorship unlikely?#

1 = Yes;0 = No;0 = Unclear.

MINUS/NEGATIVE (−) If most (six or more) of the answers to the above validity questions are “No”,the report should be designated with a minus (−) symbol on

the Evidence Worksheet.

NEUTRAL (∅) If the answers to validity criteria questions 2,3,6,and 7 do not indicate that the study is exceptionally strong,the report should be designated with

a neutral (∅) symbol on the Evidence Worksheet.

PLUS/POSITIVE (+) If most of the answers to the above validity questions are “Yes” (including criteria 2,3,6,7 and at least one additional“Yes”),the report should

be designated with a plus symbol (+) on the Evidence Worksheet.

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 5 of 10

of information they contribute i.e.,the inverse variances

of their effect estimates.Intention-to-treat analyses were

used where available/reported in the studies.If this infor-

mation was not available completers analyses was used.

Results

Overall,41 studiestargeting improvementsin student

health outcomes (physical activity, diet, weight loss) within

tertiary education settings met the inclusion/exclusion cri-

teria. Study characteristics (i.e., country, target sample and

size,age,duration,intervention and retention) and risk of

bias scores are summarised in Additional file 1:Table S1.

Risk of bias assessment indicated eight studies had a negative

rating (high risk ofbias),30 were considered neutral,and

the remaining four had a positive rating (low risk of bias).

Of the 41 studies identified,33 were conducted in the

United States[5,19,37-66],two in Turkey [67,68]and

one each in Jordan [1],Lebanon [69],Scotland [70],

Ireland [71], Taiwan [72] and Australia [9].Study designs

includedrandomizedcontrolledtrials (n = 16),non-

randomized controlled trials(n = 12)and pre-postde-

signswith no controlgroup (n = 13).Study durations

ranged from a 30-minute one-on-one briefmotivational

intervention [58]to an intervention spanning four aca-

demiccalendaryears[67].Weight loss was the sole

focus in two studies [52,59],physicalactivity in 11 stud-

ies [5,19,41,43,45,46,57,58,63,70,72],and nutrition was

the focus of10 studies [9,39,42,44,48,49,51,53,61,62].A

combination ofweightloss and/or physicalactivity

and/or nutrition outcomes were examined by 18 studies

[1,37,38,40,47,50,54-56,60,64-69,71,73].Studyparticipant

numbers ranged from 16 [53] to 2971 [50]. Retention rates

ranged from 36.6% [46] to 100% [49,51,53,62,71]; five stud-

ies [19,42,44,66,68] did not report retention rates.

Three studiesdid not reportthe sex distribution of

participants[41,57,68].Of the remaining studies,four

had even sex distribution [48,56,62,69],three had a

majorityof male participants[43,55,61];23 studies

were comprised of majority female participants

[1,5,9,37-40,42,44,47,49,50,52-54,58-60,63,65,70,71,73];

and eightstudiesconsisted ofentirely female samples

[19,45,46,51,64,66,67,72].In general,demographic charac-

teristics of participants such as age were not consistently

reported.

Effectiveness of interventions

Physical activity and fitness outcomes

As represented in Additionalfile 2:Table S2,of the 41

studies in our review,29 examined physicalactivity (11

exclusively,18 in combination with other health behav-

iors).Of these 29 studies,the average risk ofbias classi-

fication was neutral.Of the studies investigating change

in physicalactivity or fitness behavior,18 of 29 reported

significant improvements from pre- to post-intervention.

In five studies a significant increase in physical activity mi-

nuteswas achieved [50,57,63,70,71];in five studiesthe

number of days participating in physical activity increased

[5,43,58,64,65]; exercise duration increased in three studie

[38,65,67];Metabolic Equivalent of Task (METs) increased

in three studies [60,68,72];exercise barriers decreased in

one study [56];and PhysicalActivity Readiness Question-

naire (PAR-Q) scores improved in one study [50].

Meta-analysis

Total physical activity

Five studies comparing interventions targeting health be-

haviors to a control condition that assessed total physical

activitylevel at post-intervention werecombined in

meta-analysis(see Figure 1).Three of the studiesin-

cluded multiple intervention arms compared to a single

controlgroup,therefore 10,intervention versus control

comparisons were included in the analysis.

The studies were significantly heterogeneous (χ2 = 25.65,

d.f.= 9 [P = 0.002],I 2 = 65%) and demonstrated no signifi-

cant difference in total physical activity between interven-

tion and controlgroups at post-intervention (SMD −0.11

[−0.30,0.08], Z = 1.13 P = 0.26).

Table 1 Critical appraisal criteria of study methodologies (Continued)

40.Werch et al.2008 [73] 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 ∅

41.Yakusheva et al.2011 [66] 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 ∅

37 25 10 7 4 34 23 35 33 41

Criteria:1) Was the research question clearly stated? 2) Was the selection of study subjects/patients free from bias? 3) Were study groups comparable? 4) W

method of handling withdrawals described? 5) Was blinding used to prevent introduction of bias? 6) Were intervention/therapeutic regimens/exposure fac

procedure and any comparison(s) described in detail? Were intervening factors described? 7) Were outcomes clearly defined and the measurements valid

reliable? 8) Was the statisticalanalysis appropriate for the study design and type of outcome indicators? 9) Were conclusions supported by results with biases a

limitations taken into consideration? 10) Is bias due to study’s funding or sponsorship unlikely?#

1 = Yes;0 = No;0 = Unclear.

MINUS/NEGATIVE (−) If most (six or more) of the answers to the above validity questions are “No”,the report should be designated with a minus (−) symbol on

the Evidence Worksheet.

NEUTRAL (∅) If the answers to validity criteria questions 2,3,6,and 7 do not indicate that the study is exceptionally strong,the report should be designated with

a neutral (∅) symbol on the Evidence Worksheet.

PLUS/POSITIVE (+) If most of the answers to the above validity questions are “Yes” (including criteria 2,3,6,7 and at least one additional“Yes”),the report should

be designated with a plus symbol (+) on the Evidence Worksheet.

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 5 of 10

Vigorous physical activity

Five studies comparing interventions targeting health be-

haviors to a control condition that assessed vigorous phys-

ical activity levels at post-intervention were combined in a

meta-analysis (see Figure 1).Two of the studies included

multiple intervention arms compared to a single control

group;therefore eight,intervention versus controlcom-

parisons were included in the analysis.

The studieswere significantlyheterogeneous(χ2 =

44.86,d.f.= 7 [P < 0.001],I 2 = 84%) and demonstrated no

Figure 1 Meta-analysis of total (panel 1),vigorous (panel 2) and moderate (panel 3) physical activity.

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 6 of 10

Five studies comparing interventions targeting health be-

haviors to a control condition that assessed vigorous phys-

ical activity levels at post-intervention were combined in a

meta-analysis (see Figure 1).Two of the studies included

multiple intervention arms compared to a single control

group;therefore eight,intervention versus controlcom-

parisons were included in the analysis.

The studieswere significantlyheterogeneous(χ2 =

44.86,d.f.= 7 [P < 0.001],I 2 = 84%) and demonstrated no

Figure 1 Meta-analysis of total (panel 1),vigorous (panel 2) and moderate (panel 3) physical activity.

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 6 of 10

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

significantdifference in vigorous physicalactivity levels

between the intervention and controlgroupsat post-

intervention (SMD 0.28 [−0.08,0.63],Z = 1.54 P = 0.12)

(see Figure 1).

Moderate physical activity

As represented in Figure 1,five studies comparing inter-

ventions targeting health behaviors to a controlcondi-

tion that assessed moderate physicalactivity levelsat

post-intervention were combined in meta-analysis.Two

of the studies included multiple intervention arms com-

pared to a single controlgroup;therefore eight,inter-

vention versus control comparisons were included in the

analysis.

The studies were homogenous (χ2 = 6.86,d.f. = 7 [P =

0.44], I2 = 0%) and demonstrated significantly greater mod-

erate physical activity levels in the intervention group com-

pared to the control group at post intervention (SMD 0.18

[0.06,0.30], Z = 2.84 P = 0.005).

Nutrition outcomes

Of the 41 included studies,24 reported nutrition out-

comes (10 examined nutrition exclusively),with fruit and

vegetable intake the most reported outcome, used in 12 of

the reported studies [39,40,44,47,49-51,54,56,62,65,73].Of

the 24 studies,the average risk of bias rating was neutral.

Six studies had a negative rating,sixteen were neutral and

two had a positive rating.

Interventions were found to be effective in improving nu-

trition behaviors in 12 of the 24 studies [1,39,44,49-51,54,

60-62,65,68]. In three studies a significant improvement in

dietquality was achieved [1,61,68];six studies reported

vegetable intake increases [39,44,49-51,54];in six studies

fruit intake increased [39,44,49,50,54,62];fat intake was

reduced in four studies [44,51,60,61];fewer calories were

consumed in one study [60];frequency ofwholegrain

product consumption was increased in one study [50];and

consumption ofhealthy fats increased in one study [65].

Due to the heterogeneity and lack of standard methods to

assess dietary intake within the nutrition domain,a meta-

analysis was unable to be conducted.

Weight outcomes

Of the 41 included studies, 12 reported weight-related out-

comes (two examined weight exclusively) [37,38,40,47,50,

52,54,55,59,64,66,71] and of these 12,four reported signifi-

cantimprovements in these outcomes [38,47,52,66].The

average risk of bias rating for the 12 studies was neutral. A

significant reduction in waist-to-hip ratio was reported in

one study [38];in one study BMI decreased significantly

[47];one study reported significant weight loss [52];and a

significant increase in the number of participants trying to

lose weightwas reported by one study [66].Due to the

variation in aimsand measureswithin the domain of

weight, a meta-analysis was not conducted.

Discussion

The current review identified 41 studies that investigated

the impactof lifestyle interventions targeting improve-

mentof health outcomes (specifically physicalactivity,

diet or weight)for students within the tertiary sector.

Most studies reported atleastone significantimprove-

mentin a health outcome variable,with a numberof

studies having multiple significant impacts.Study results

were mostly positive,with at leasthalf of the studies

for physicalactivity and nutrition reporting significant

outcomes.These included18/29 studiesexamining

physicalactivity thatfound significanteffectsinclud-

ing increased physicalactivity minutes,an increase in

the number of days participating in physical activity and

also in exercise duration,increased METsand PAR-Q

scores and a decrease in barriers to exercise.In addition,

results ofthe meta-analysis suggestthe studies target-

ing moderatephysicalactivitydemonstrated signifi-

cantly greatermoderate physicalactivity levels in the

intervention group compared to the controlgroup at

postintervention.Of the studies examining nutrition,

50% reported significantimprovements,including im-

proved diet quality,increased fruit,vegetable and whole-

grain intake,and healthy fats and a reduction in overall

fat intake and calories.Of the studies examining body

weight,four of 12 resulted in significantoutcomes in-

cluding reductions in weight,BMI, and WHR and/or

an increasein the numberof participantstrying to

lose weight.

Interventionsspanning a university semesteror less

(≤12 weeks)generally resulted in a greater number of

significantoutcomesin comparison to interventions

with a duration of more than a semester.In addition,in-

terventions targeting nutrition only resulted in more sig-

nificant outcomes in comparison to targeting PA,weight

or multiple behaviours. For instance, of the ten intervention

targeting dietary behaviour,eight (80%) had significant re-

sults and the majority of these studies (7/8) were ≤12 week

For PA only studies,seven ofthe 11 (64%) interventions

had significant results,and of these seven studies five had

a duration of≤12 weeks.Of the two studies examining

weightonly interventions,only the 12 week study re-

ported significant results.Furthermore,when targeting a

combination ofbehaviours,11 of18 (61%) interventions

had significant results, and just over half of these interven-

tions had a duration of ≤12 weeks (6/11).

Less than half of the studies in each category were ran-

domized controlled trials,however there was no trend

(based on study counts)towards study design influen-

cing the effectiveness of interventions.The vast majority

of the studies were conducted in the USA (n = 31)and

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 7 of 10

between the intervention and controlgroupsat post-

intervention (SMD 0.28 [−0.08,0.63],Z = 1.54 P = 0.12)

(see Figure 1).

Moderate physical activity

As represented in Figure 1,five studies comparing inter-

ventions targeting health behaviors to a controlcondi-

tion that assessed moderate physicalactivity levelsat

post-intervention were combined in meta-analysis.Two

of the studies included multiple intervention arms com-

pared to a single controlgroup;therefore eight,inter-

vention versus control comparisons were included in the

analysis.

The studies were homogenous (χ2 = 6.86,d.f. = 7 [P =

0.44], I2 = 0%) and demonstrated significantly greater mod-

erate physical activity levels in the intervention group com-

pared to the control group at post intervention (SMD 0.18

[0.06,0.30], Z = 2.84 P = 0.005).

Nutrition outcomes

Of the 41 included studies,24 reported nutrition out-

comes (10 examined nutrition exclusively),with fruit and

vegetable intake the most reported outcome, used in 12 of

the reported studies [39,40,44,47,49-51,54,56,62,65,73].Of

the 24 studies,the average risk of bias rating was neutral.

Six studies had a negative rating,sixteen were neutral and

two had a positive rating.

Interventions were found to be effective in improving nu-

trition behaviors in 12 of the 24 studies [1,39,44,49-51,54,

60-62,65,68]. In three studies a significant improvement in

dietquality was achieved [1,61,68];six studies reported

vegetable intake increases [39,44,49-51,54];in six studies

fruit intake increased [39,44,49,50,54,62];fat intake was

reduced in four studies [44,51,60,61];fewer calories were

consumed in one study [60];frequency ofwholegrain

product consumption was increased in one study [50];and

consumption ofhealthy fats increased in one study [65].

Due to the heterogeneity and lack of standard methods to

assess dietary intake within the nutrition domain,a meta-

analysis was unable to be conducted.

Weight outcomes

Of the 41 included studies, 12 reported weight-related out-

comes (two examined weight exclusively) [37,38,40,47,50,

52,54,55,59,64,66,71] and of these 12,four reported signifi-

cantimprovements in these outcomes [38,47,52,66].The

average risk of bias rating for the 12 studies was neutral. A

significant reduction in waist-to-hip ratio was reported in

one study [38];in one study BMI decreased significantly

[47];one study reported significant weight loss [52];and a

significant increase in the number of participants trying to

lose weightwas reported by one study [66].Due to the

variation in aimsand measureswithin the domain of

weight, a meta-analysis was not conducted.

Discussion

The current review identified 41 studies that investigated

the impactof lifestyle interventions targeting improve-

mentof health outcomes (specifically physicalactivity,

diet or weight)for students within the tertiary sector.

Most studies reported atleastone significantimprove-

mentin a health outcome variable,with a numberof

studies having multiple significant impacts.Study results

were mostly positive,with at leasthalf of the studies

for physicalactivity and nutrition reporting significant

outcomes.These included18/29 studiesexamining

physicalactivity thatfound significanteffectsinclud-

ing increased physicalactivity minutes,an increase in

the number of days participating in physical activity and

also in exercise duration,increased METsand PAR-Q

scores and a decrease in barriers to exercise.In addition,

results ofthe meta-analysis suggestthe studies target-

ing moderatephysicalactivitydemonstrated signifi-

cantly greatermoderate physicalactivity levels in the

intervention group compared to the controlgroup at

postintervention.Of the studies examining nutrition,

50% reported significantimprovements,including im-

proved diet quality,increased fruit,vegetable and whole-

grain intake,and healthy fats and a reduction in overall

fat intake and calories.Of the studies examining body

weight,four of 12 resulted in significantoutcomes in-

cluding reductions in weight,BMI, and WHR and/or

an increasein the numberof participantstrying to

lose weight.

Interventionsspanning a university semesteror less

(≤12 weeks)generally resulted in a greater number of

significantoutcomesin comparison to interventions

with a duration of more than a semester.In addition,in-

terventions targeting nutrition only resulted in more sig-

nificant outcomes in comparison to targeting PA,weight

or multiple behaviours. For instance, of the ten intervention

targeting dietary behaviour,eight (80%) had significant re-

sults and the majority of these studies (7/8) were ≤12 week

For PA only studies,seven ofthe 11 (64%) interventions

had significant results,and of these seven studies five had

a duration of≤12 weeks.Of the two studies examining

weightonly interventions,only the 12 week study re-

ported significant results.Furthermore,when targeting a

combination ofbehaviours,11 of18 (61%) interventions

had significant results, and just over half of these interven-

tions had a duration of ≤12 weeks (6/11).

Less than half of the studies in each category were ran-

domized controlled trials,however there was no trend

(based on study counts)towards study design influen-

cing the effectiveness of interventions.The vast majority

of the studies were conducted in the USA (n = 31)and

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 7 of 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

therefore the global generalizability of these results must

be interpreted with caution.

With few exceptions,participantnumberswere sur-

prisingly smallgiven the large institutions from which

participants were drawn.Additionally,participants were

overwhelmingly female,which may be due in part to the

higher percentage of females enrolled in some universities

and colleges.This raises questions about the approaches

used to recruit participants or the intrinsic appeal of the in-

terventionstrialed.Indeed,resultsfrom a questionnaire

examining gender differences in the health habits of univer-

sity students showed that males were less interested in nu-

trition advice and health-enhancing behaviors,suggesting

that interventions targeting health behaviors in university/

college students may need to be gender-specific to address

the different needs and interests of both sexes [15].

The transition from secondary to tertiary education

often results in an increase in health risk secondary to a

decrease in physical activity and increase in poor dietary

choices [74].For many students,making the transition

to tertiary education coincides with more freedom and

controlover their lives.However,this can contribute to

the increases in risk taking behaviors that are evident in

this population [75].With this new-found independence,

many students may not have developed skills such as self-

efficacy and accountability,leaving them at higher risk of

adopting unhealthy behaviors.A number of studies in this

review successfully targeted self-efficacy [5,7,39,46,54,57,64]

to improve health behaviors.

Interventionsthatwere embedded within university/

college courses were effective at improving physicalac-

tivity,nutrition and weight-related outcomes.Course-

embedded interventionsinvolvefrequentface-to-face

contactwith facilitators.It has been suggested thatfre-

quent professionalcontact may improve health outcomes

by enhancing vigilance and providing encouragement and

support[76].Additionally,interventions where students

received feedback on their progress appeared to be more

effective than simply attending lectures or receiving edu-

cational resources.

Universities and colleges are an idealsetting for imple-

mentation of health promotion programs as they support

a large studentpopulation atkey time for the develop-

ment of lifestyle skills and behaviors.Students have access

to world-class facilities,technology,and highly educated

staff including a variety of health disciplines,all of which

could contribute to the developmentof highly effective

health promoting interventions.A number ofstudies in

this review utilized university facilities, such as fitness cen-

tresand designated walking tracks,showing significant

improvements in physicalactivity outcomes.Besides ease

of access for students,use ofexisting facilities and re-

sources is also cost-effective, which is often a major limita-

tion of health promotion programs.

Conclusions

This study extends the current literature examining the

effectiveness ofinterventions targeting physicalactivity,

nutrition and weight-loss behaviors amongstuniversity

and college students.To the best ofthe authors’know-

ledge itis the firstsystematic review examining health

behaviors of students within a tertiary education setting.

Some limitations ofthe field existwhich should be ac-

knowledged.First,the majority of studies examined were

conducted in the USA,which may limit interpretations

and globalgeneralizability ofresults.Second,only four

of the 41 studies that met the inclusion criteria showed

a positive result in meeting the risk ofbias validity cri-

teria questions.Also, the potentialeffectof publication

bias mustbe considered,as the observationsmade in

this review did notinclude grey literature (e.g.,unpub-

lished dissertations).

This review has severalstrengths.It employed a com-

prehensive search strategy,adhered to the PRISMA proto-

col with two reviewersused forthe identification and

evaluation of studies [30],assessed study risk ofbias with

two independent reviewers using the Academy of Nutrition

and Dietetics Quality Criteria Checklist,and included a

meta-analyses for physical activity.

Tertiary education students within the university/college

setting are ideal targets for lifestyle interventions aimed at

improving health behaviors.Within this setting,students

are often surrounded by an abundance of research expert-

ise, multi-disciplinaryhealth professionals,and world-

class facilities and resources making this potentially an

ideal health-promoting environment.Additionally,stu-

dents are in a learning environment and are still at an age

where health behaviors that impact on health later in life

can be improved.Therefore,there is significant scope for

implementation oflifestyle interventions to improve the

health of this group that represents a significant propor-

tion of our population.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Study Characteristics.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Study Results.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’contributions

RCP,SAC,CEC,RC and JG conceptualized and designed the study.SAC and

JA drafted the introduction section.SAC,RLW,SGK,SLR extracted the data.

MJH conducted the statisticalanalyses.Allauthors contributed to the writing

and editing of the manuscript.Allauthors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Acknowledgements

RCP is supported by a National Health & Medical Research Council (NH & MR

Senior Research Fellowship.

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 8 of 10

be interpreted with caution.

With few exceptions,participantnumberswere sur-

prisingly smallgiven the large institutions from which

participants were drawn.Additionally,participants were

overwhelmingly female,which may be due in part to the

higher percentage of females enrolled in some universities

and colleges.This raises questions about the approaches

used to recruit participants or the intrinsic appeal of the in-

terventionstrialed.Indeed,resultsfrom a questionnaire

examining gender differences in the health habits of univer-

sity students showed that males were less interested in nu-

trition advice and health-enhancing behaviors,suggesting

that interventions targeting health behaviors in university/

college students may need to be gender-specific to address

the different needs and interests of both sexes [15].

The transition from secondary to tertiary education

often results in an increase in health risk secondary to a

decrease in physical activity and increase in poor dietary

choices [74].For many students,making the transition

to tertiary education coincides with more freedom and

controlover their lives.However,this can contribute to

the increases in risk taking behaviors that are evident in

this population [75].With this new-found independence,

many students may not have developed skills such as self-

efficacy and accountability,leaving them at higher risk of

adopting unhealthy behaviors.A number of studies in this

review successfully targeted self-efficacy [5,7,39,46,54,57,64]

to improve health behaviors.

Interventionsthatwere embedded within university/

college courses were effective at improving physicalac-

tivity,nutrition and weight-related outcomes.Course-

embedded interventionsinvolvefrequentface-to-face

contactwith facilitators.It has been suggested thatfre-

quent professionalcontact may improve health outcomes

by enhancing vigilance and providing encouragement and

support[76].Additionally,interventions where students

received feedback on their progress appeared to be more

effective than simply attending lectures or receiving edu-

cational resources.

Universities and colleges are an idealsetting for imple-

mentation of health promotion programs as they support

a large studentpopulation atkey time for the develop-

ment of lifestyle skills and behaviors.Students have access

to world-class facilities,technology,and highly educated

staff including a variety of health disciplines,all of which

could contribute to the developmentof highly effective

health promoting interventions.A number ofstudies in

this review utilized university facilities, such as fitness cen-

tresand designated walking tracks,showing significant

improvements in physicalactivity outcomes.Besides ease

of access for students,use ofexisting facilities and re-

sources is also cost-effective, which is often a major limita-

tion of health promotion programs.

Conclusions

This study extends the current literature examining the

effectiveness ofinterventions targeting physicalactivity,

nutrition and weight-loss behaviors amongstuniversity

and college students.To the best ofthe authors’know-

ledge itis the firstsystematic review examining health

behaviors of students within a tertiary education setting.

Some limitations ofthe field existwhich should be ac-

knowledged.First,the majority of studies examined were

conducted in the USA,which may limit interpretations

and globalgeneralizability ofresults.Second,only four

of the 41 studies that met the inclusion criteria showed

a positive result in meeting the risk ofbias validity cri-

teria questions.Also, the potentialeffectof publication

bias mustbe considered,as the observationsmade in

this review did notinclude grey literature (e.g.,unpub-

lished dissertations).

This review has severalstrengths.It employed a com-

prehensive search strategy,adhered to the PRISMA proto-

col with two reviewersused forthe identification and

evaluation of studies [30],assessed study risk ofbias with

two independent reviewers using the Academy of Nutrition

and Dietetics Quality Criteria Checklist,and included a

meta-analyses for physical activity.

Tertiary education students within the university/college

setting are ideal targets for lifestyle interventions aimed at

improving health behaviors.Within this setting,students

are often surrounded by an abundance of research expert-

ise, multi-disciplinaryhealth professionals,and world-

class facilities and resources making this potentially an

ideal health-promoting environment.Additionally,stu-

dents are in a learning environment and are still at an age

where health behaviors that impact on health later in life

can be improved.Therefore,there is significant scope for

implementation oflifestyle interventions to improve the

health of this group that represents a significant propor-

tion of our population.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Study Characteristics.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Study Results.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’contributions

RCP,SAC,CEC,RC and JG conceptualized and designed the study.SAC and

JA drafted the introduction section.SAC,RLW,SGK,SLR extracted the data.

MJH conducted the statisticalanalyses.Allauthors contributed to the writing

and editing of the manuscript.Allauthors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Acknowledgements

RCP is supported by a National Health & Medical Research Council (NH & MR

Senior Research Fellowship.

Plotnikoff et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity (2015) 12:45 Page 8 of 10

Author details

1Priority Research Centre for PhysicalActivity and Nutrition,University of

Newcastle,Callaghan Campus,Newcastle,NSW,Australia.2Schoolof

Education,Faculty of Education and Arts,University of Newcastle,Callaghan

Campus,Newcastle,NSW,Australia.3Schoolof Health Sciences,Faculty of

Health,University of Newcastle,Callaghan Campus,Newcastle,NSW,

Australia.4Schoolof BiomedicalSciences and Pharmacy,Faculty of Health,

University of Newcastle,Callaghan Campus,Newcastle,NSW,Australia.