Point-of-Decision Prompts to Increase Stair Use: A Systematic Review Update

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/29

|9

|7490

|401

AI Summary

This systematic review update examines the effectiveness of point-of-decision prompts to encourage stair use and enhancements to stairs or stairwells when combined with point-of-decision prompts to increase stair use. The article describes the rationale for these systematic reviews, along with information about the review process and the resulting conclusions.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Point-of-Decision Prompts to Increase

Stair Use

A Systematic Review Update

Robin E. Soler, PhD, Kimberly D. Leeks, PhD, MPH, Leigh Ramsey Buchanan, PhD,

Ross C. Brownson, PhD, Gregory W. Heath, DHSc, MPH, David H. Hopkins, MD, MPH,

the Task Force on Community Preventive Services

Abstract:In 2000, the Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community Guide) completed a

systematic review of the effectiveness of various approaches to increasing physical activity including

informational,behavioraland social,and environmentaland policy approaches.Among these

approaches was the use of signs placed by elevators and escalators to encourage stair use.This

approach was found to be effective based on suffıcient evidence. Over the past 5 years the body of

evidence of this intervention has increased substantially, warranting an updated review. This update

was conducted on 16 peer-reviewed studies (including the six studies in the previous systematic

review),which met specifıed quality criteria and included evaluation outcomes of interest.These

studies evaluated two interventions: point-of-decision prompts to increase stair use and enhance-

ments to stairs or stairwells (e.g., painting walls, laying carpet, adding artwork, playing music) when

combined with point-of-decision prompts to increase stair use.This latter intervention was not

included in the original systematic review.

According to the Community Guide rules of evidence,there is strong evidence that point-of-

decision prompts are effective in increasing the use of stairs. There is insuffıcient evidence, due to a

inadequate number of studies, to determine whether or not enhancements to stairs or stairwells are

an effective addition to point-of-decision prompts.This article describes the rationale for these

systematic reviews, along with information about the review process and the resulting conclusions.

Additionalinformation about applicability,other effects,and barriers to implementation is also

provided.

(Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300) Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of American Journal of Preventive

Medicine

Introduction

The prevalence ofoverweight and obesity in the

U.S. has increased over the past several decades.

In 2003–2004,66.3% of adults in the U.S.were

overweightor obese,and 32.2% were obese.1 Obesity

increases the risk of many diseases and health conditions,

including hypertension,type 2 diabetes,coronary heart

disease,stroke,gallbladder disease,osteoarthritis,and

some cancers.2 The primary cause ofoverweightand

obesity in the U.S. is energy imbalance.2,3Energy imbal-

ance occurs when the number of calories used is not equ

to the number of calories consumed. Energy expenditure

has been on the decline in the U.S. for decades, due in p

to increasing automation of previously manual activi-

ties.In 1996,the U.S.Preventive Services Task Force

(USPSTF) recommended thathealthcareproviders

counsel all patients on the importance of incorporating

physicalactivity into their daily routines.4 One way to

increase energy expenditure,and improve energy bal-

ance, is to incorporate small bouts of physical activity in

daily routines.3

Many intervention approaches are available to increas

engagement in physical activity by adults.5 Each of these

approaches has a set of advantages and disadvantages

can be applied, with differing degrees of success, to peo

with a variety of demographic characteristics and life-

styles in diverse locations. As noted in an earlier review

From the Community Guide Branch, Division of Health Communications

and Marketing Strategy,NationalCenter for Health Marketing,(Soler,

Leeks,Hopkins) and the Chronic Disease Nutrition Branch,Division of

Nutrition,PhysicalActivity,and Obesity,NationalCenter for Chronic

Disease Health Promotion and Prevention (Buchanan),CDC, Atlanta,

Georgia;St.Louis University,Schoolof Public Health (Brownson),St.

Louis, Missouri; and University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Department

of Health and Human Performance (Heath), Chattanooga, Tennessee

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Robin E. Soler, PhD,

Community Guide Branch,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

1600 Clifton Road, MS-E69, Atlanta GA 30333. E-mail: RSoler@cdc.gov.

0749-3797/00/$17.00

doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.028

S292 Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of American Journal of Preventive Medicin

Stair Use

A Systematic Review Update

Robin E. Soler, PhD, Kimberly D. Leeks, PhD, MPH, Leigh Ramsey Buchanan, PhD,

Ross C. Brownson, PhD, Gregory W. Heath, DHSc, MPH, David H. Hopkins, MD, MPH,

the Task Force on Community Preventive Services

Abstract:In 2000, the Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community Guide) completed a

systematic review of the effectiveness of various approaches to increasing physical activity including

informational,behavioraland social,and environmentaland policy approaches.Among these

approaches was the use of signs placed by elevators and escalators to encourage stair use.This

approach was found to be effective based on suffıcient evidence. Over the past 5 years the body of

evidence of this intervention has increased substantially, warranting an updated review. This update

was conducted on 16 peer-reviewed studies (including the six studies in the previous systematic

review),which met specifıed quality criteria and included evaluation outcomes of interest.These

studies evaluated two interventions: point-of-decision prompts to increase stair use and enhance-

ments to stairs or stairwells (e.g., painting walls, laying carpet, adding artwork, playing music) when

combined with point-of-decision prompts to increase stair use.This latter intervention was not

included in the original systematic review.

According to the Community Guide rules of evidence,there is strong evidence that point-of-

decision prompts are effective in increasing the use of stairs. There is insuffıcient evidence, due to a

inadequate number of studies, to determine whether or not enhancements to stairs or stairwells are

an effective addition to point-of-decision prompts.This article describes the rationale for these

systematic reviews, along with information about the review process and the resulting conclusions.

Additionalinformation about applicability,other effects,and barriers to implementation is also

provided.

(Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300) Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of American Journal of Preventive

Medicine

Introduction

The prevalence ofoverweight and obesity in the

U.S. has increased over the past several decades.

In 2003–2004,66.3% of adults in the U.S.were

overweightor obese,and 32.2% were obese.1 Obesity

increases the risk of many diseases and health conditions,

including hypertension,type 2 diabetes,coronary heart

disease,stroke,gallbladder disease,osteoarthritis,and

some cancers.2 The primary cause ofoverweightand

obesity in the U.S. is energy imbalance.2,3Energy imbal-

ance occurs when the number of calories used is not equ

to the number of calories consumed. Energy expenditure

has been on the decline in the U.S. for decades, due in p

to increasing automation of previously manual activi-

ties.In 1996,the U.S.Preventive Services Task Force

(USPSTF) recommended thathealthcareproviders

counsel all patients on the importance of incorporating

physicalactivity into their daily routines.4 One way to

increase energy expenditure,and improve energy bal-

ance, is to incorporate small bouts of physical activity in

daily routines.3

Many intervention approaches are available to increas

engagement in physical activity by adults.5 Each of these

approaches has a set of advantages and disadvantages

can be applied, with differing degrees of success, to peo

with a variety of demographic characteristics and life-

styles in diverse locations. As noted in an earlier review

From the Community Guide Branch, Division of Health Communications

and Marketing Strategy,NationalCenter for Health Marketing,(Soler,

Leeks,Hopkins) and the Chronic Disease Nutrition Branch,Division of

Nutrition,PhysicalActivity,and Obesity,NationalCenter for Chronic

Disease Health Promotion and Prevention (Buchanan),CDC, Atlanta,

Georgia;St.Louis University,Schoolof Public Health (Brownson),St.

Louis, Missouri; and University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Department

of Health and Human Performance (Heath), Chattanooga, Tennessee

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Robin E. Soler, PhD,

Community Guide Branch,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

1600 Clifton Road, MS-E69, Atlanta GA 30333. E-mail: RSoler@cdc.gov.

0749-3797/00/$17.00

doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.028

S292 Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of American Journal of Preventive Medicin

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

the Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community

Guide),which evaluated interventions designed to in-

crease physicalactivity,“the role ofcommunity-based

interventions to promote physical activity has emerged as

a critical piece of an overall strategy to increase physical

activity behaviorsamong thepeopleof the United

States.”5 This 2002 review focused on community-based

intervention approaches, including:

● Informationalapproaches to change knowledge and

attitudes about the benefıts of and opportunities for

physical activity within a community;

● Behavioral and social approaches to teach people the

behavioral management skills necessary both for suc-

cessful adoption and maintenance of behavior change

and for creating social environments that facilitate and

enhance behavioral change; and

● Environmentaland policy approaches to change the

structure of physical and organizational environments

to provide safe,attractive,and convenient places for

physical activity.

This article reports the fındings from an update to the

2002 Point-of-Decision Prompts review,which is a be-

havior and social approach as described above. The up-

dated systematic review examines literature regarding the

effectiveness of prompts on increasing stair use either by

increasing the number of actual stair users or increasing

the frequency of stair use through prompts that relate to

both of these foci, which can be implemented by commu-

nities to help increase levels of physical activity. Point-of-

decision prompts can be used alone or with stairwell

enhancements in an attempt to improve the effectiveness

of the prompt (i.e., by making stairwells more attractive

to potential users).

Guide to Community Preventive Services

The systematic reviews in this report present the fındings

of the independent, nonfederal Task Force on Commu-

nity Preventive Services (Task Force). The Task Force is

developing the Community Guide with the support of the

USDHHS in collaboration with public and private part-

ners. The CDC provides staff support to the Task Force

for development of the Community Guide. The book, The

Guide to Community Preventive Services. What Works to

Promote Health? (Oxford University Press,2005;also

available at www.thecommunityguide.org) presents the

background and the methods used in developing the

Community Guide.The physicalactivity review noted

above was published in the American Journal of Preven-

tive Medicine in 20025,6and describes the broader ana-

lytic framework used to evaluate the effectivenessof

community-based physical activity interventions.

Methods

This updated review was conducted according to the me

ods developed for the Community Guide, which have bee

described in detail elsewhere.5,7As an update to an existing

Community Guide review,5 some information and guidance

was drawn from the previous review team and resulting

documentation. Inclusion criteria for studies in this revie

were:(1) primary research published in a peer-reviewed

journal;(2) published in English before April20,2005;

(3) met the minimum research quality for study design a

execution7; and (4) evaluated the effects ofpoint-of-decision

prompts to encourage stair use (with or without enhance

ments to the stairwell).The outcome measure remained

stair use, and the search strategy was widened by inclus

additional electronic databases. The systematic review t

(the team) accepted the broader conceptual approach o

original physical activity review5 but developed a new con-

ceptualframework for the interventions evaluated in this

update. The team recalculated the original effect size me

sure (relative change) and calculated a new summary eff

measure (absolute change);reexamined the evidence re-

garding applicability of this intervention;and updated the

overall conclusions based on the original six studies and

additional ten studies found through the updated literatu

search.

Conceptual Approach

Point-of-decision prompts are motivational signs, placed

or near stairwells or at the base of elevators and escalat

encouraging people to use the stairs.These prompts are

typically designed to change a behavior of interest by pr

viding information about a healthier alternative or estab

ing a deterrent to the behavioral standard (e.g., announc

that an elevator is off limits to those capable of using sta

with the intended goal of motivating and enabling peopl

change their behavior and maintain that change over tim

Stairwellenhancements improve the appearance ofstair-

wells by painting walls or laying carpet.A conceptualap-

proach was used to evaluate the effectiveness of point-o

decision prompts and stairwellenhancements to increase

stair use. The approach suggests that extended presenc

point-of-decision promptdesigned to increase stairuse

might work by changing individual knowledge or attitude

about using the stairs. Information provided through sta

prompts might also contribute to an individual’s change

knowledge or attitudes about the value of physical activ

general. As a result, prompts are expected to increase th

of stairs as a mode of transportation and may change at

tudes toward or amount of engagement in physical activ

Walking up or down stairs uses more energy than taking

elevator or escalator,and stair use requires bodily move-

ment. The relationships between stair use and caloric ex

diture and between stair use and physical activity were n

reviewed. This conceptual approach suggests that the sl

Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300 S293

February 2010

Guide),which evaluated interventions designed to in-

crease physicalactivity,“the role ofcommunity-based

interventions to promote physical activity has emerged as

a critical piece of an overall strategy to increase physical

activity behaviorsamong thepeopleof the United

States.”5 This 2002 review focused on community-based

intervention approaches, including:

● Informationalapproaches to change knowledge and

attitudes about the benefıts of and opportunities for

physical activity within a community;

● Behavioral and social approaches to teach people the

behavioral management skills necessary both for suc-

cessful adoption and maintenance of behavior change

and for creating social environments that facilitate and

enhance behavioral change; and

● Environmentaland policy approaches to change the

structure of physical and organizational environments

to provide safe,attractive,and convenient places for

physical activity.

This article reports the fındings from an update to the

2002 Point-of-Decision Prompts review,which is a be-

havior and social approach as described above. The up-

dated systematic review examines literature regarding the

effectiveness of prompts on increasing stair use either by

increasing the number of actual stair users or increasing

the frequency of stair use through prompts that relate to

both of these foci, which can be implemented by commu-

nities to help increase levels of physical activity. Point-of-

decision prompts can be used alone or with stairwell

enhancements in an attempt to improve the effectiveness

of the prompt (i.e., by making stairwells more attractive

to potential users).

Guide to Community Preventive Services

The systematic reviews in this report present the fındings

of the independent, nonfederal Task Force on Commu-

nity Preventive Services (Task Force). The Task Force is

developing the Community Guide with the support of the

USDHHS in collaboration with public and private part-

ners. The CDC provides staff support to the Task Force

for development of the Community Guide. The book, The

Guide to Community Preventive Services. What Works to

Promote Health? (Oxford University Press,2005;also

available at www.thecommunityguide.org) presents the

background and the methods used in developing the

Community Guide.The physicalactivity review noted

above was published in the American Journal of Preven-

tive Medicine in 20025,6and describes the broader ana-

lytic framework used to evaluate the effectivenessof

community-based physical activity interventions.

Methods

This updated review was conducted according to the me

ods developed for the Community Guide, which have bee

described in detail elsewhere.5,7As an update to an existing

Community Guide review,5 some information and guidance

was drawn from the previous review team and resulting

documentation. Inclusion criteria for studies in this revie

were:(1) primary research published in a peer-reviewed

journal;(2) published in English before April20,2005;

(3) met the minimum research quality for study design a

execution7; and (4) evaluated the effects ofpoint-of-decision

prompts to encourage stair use (with or without enhance

ments to the stairwell).The outcome measure remained

stair use, and the search strategy was widened by inclus

additional electronic databases. The systematic review t

(the team) accepted the broader conceptual approach o

original physical activity review5 but developed a new con-

ceptualframework for the interventions evaluated in this

update. The team recalculated the original effect size me

sure (relative change) and calculated a new summary eff

measure (absolute change);reexamined the evidence re-

garding applicability of this intervention;and updated the

overall conclusions based on the original six studies and

additional ten studies found through the updated literatu

search.

Conceptual Approach

Point-of-decision prompts are motivational signs, placed

or near stairwells or at the base of elevators and escalat

encouraging people to use the stairs.These prompts are

typically designed to change a behavior of interest by pr

viding information about a healthier alternative or estab

ing a deterrent to the behavioral standard (e.g., announc

that an elevator is off limits to those capable of using sta

with the intended goal of motivating and enabling peopl

change their behavior and maintain that change over tim

Stairwellenhancements improve the appearance ofstair-

wells by painting walls or laying carpet.A conceptualap-

proach was used to evaluate the effectiveness of point-o

decision prompts and stairwellenhancements to increase

stair use. The approach suggests that extended presenc

point-of-decision promptdesigned to increase stairuse

might work by changing individual knowledge or attitude

about using the stairs. Information provided through sta

prompts might also contribute to an individual’s change

knowledge or attitudes about the value of physical activ

general. As a result, prompts are expected to increase th

of stairs as a mode of transportation and may change at

tudes toward or amount of engagement in physical activ

Walking up or down stairs uses more energy than taking

elevator or escalator,and stair use requires bodily move-

ment. The relationships between stair use and caloric ex

diture and between stair use and physical activity were n

reviewed. This conceptual approach suggests that the sl

Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300 S293

February 2010

increase in caloric expenditure (energy expenditure) result-

ing from stair use, which serves to improve energy balance

can,in combination with other forms of physical activity,

contribute to physiologic improvements that are,in turn,

related to longer-term health outcomes.

Selection of Outcomes for Review

The primary outcomes examined in this review were objec-

tive measurements of changes in the use of stairs during two

or more periods of time. Objective measurements were vi-

sual counts of people using the stairs or electronic counts

(from devices such as motion detectors). Some of the quali-

fying studies reported other outcomes which were examined

but are not presented in this report.

Selection of stair use as an outcome assumes that small

amounts ofphysicalactivity on a regular basis willhelp

improve the energy imbalance that affects large numbers of

people (particularly people who are sedentary and those

who are obese).Stair use typically involves ascending or

descending one to four flights per day. Using stairs expends

twice as much energy as using elevators8 with each stair

ascended burning approximately 0.11 kilocalorie and each

stair descended burning approximately 0.05 kilocalorie.9

Regular, substantial stair use (as many as six assents of 199

steps per assent per day for 12 weeks) has been shown to

improve cardiovascular outcomes among previously seden-

tary young women10and Benn et al., in their study of a small

group of older men found that

climbing only three to four flights of stairs at a mod-

erate pace (approximately 50 –70 s) elicits peak circu-

latory demands similar to, but at a much more rapid

rate ofadjustmentthan,10 minutes ofhorizontal

walking at2.5 mph,intermittently carrying a 30-

pound weight, or 4 minutes of walking up a moder-

ately steep slope.11

Over the long-term, this added energy expenditure could

contribute to improved energy balance and longer-term

health outcomes such as weight control.

Search Strategy

The articles considered for this review were obtained from

systematic searches of multiple databases, reviews of biblio-

graphic reference lists, and consultations with experts in the

fıeld. The team’s updated search for evidence encompassed

the period from 2000 to April 2005, which overlapped with

the search conducted for the originalCommunity Guide

review of these interventions (search period 1980 –2000).5

The original review used the following seven databases: En-

viroline, MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Social SciSearch, Sociologi-

cal Abstracts, Sportdiscus, and Transportation Research In-

formation Services (TRIS).For the team’s updated search,

the following 15 databaseswere examined:ArticleFirst,

CINAHL, EMBASE, Enviroline, Health Promotion and Edu-

cation Database, MEDLINE, Ovid, PsycINFO, PubMed, So-

cialSciSearch,SocialScience Citation Index,Sociological

Abstracts,SPORTDiscus,Transportation Research Infor-

mation Services (TRIS),and WorldCat.This list includes

some databases notavailable atthe time ofthe original

review.

Evaluating and Summarizing the Studies

Each study that met the inclusion criteria was evaluated fo

the suitability of the study design and study execution usin

the standardized Community Guide abstraction form.12The

suitability of each study design was rated as greatest, mod

erate, or least depending on the degree to which the desig

protects against threats to validity.The execution of each

study was rated as good,fair,or limited on the basis of

several predetermined factors that could potentially limit a

study’s utility for assessing effectiveness.Each study was

reviewed by at least two trained researchers. Concerns abo

study design and execution were discussed with an expert

physicalactivity interventions and differences in opinion

were resolved by consensus among a team of three system

atic reviewers (the coordination team).Only studies rated

greatest or moderate in design suitability and good or fair i

execution were considered qualifying studies and included

in the team’s fınal assessment of the evidence in this revie

Studies with limited execution are,by Community Guide

methods, excluded from consideration, and studies of least

suitable design were excluded by the coordination team

because the body of literature was adequately represented

with moderate and greatest suitability study designs.

Calculation of Effect Sizes

The qualifying studies provided measurements of change i

the number or proportion of people using the stairs before

and after the implementation of point-of-decision prompts

(with or without additional enhancements to the stairs or

stairwells).To facilitate comparison across studies and an

evaluation across the body of evidence, individual study ar

results were converted (if necessary) into measurements o

both absolute and relative percentage change.In addition,

whenever possible, a mean effect size was calculated on th

entire sample in each study arm.Studies contained more

than one study arm when there were multiple locations or

mechanismsof implementation forthe intervention.In

some cases,effectmeasures were reported for subgroup

means (e.g.,one for men and one for women).For these

study fındings, the mean of the subgroups was incorporate

into the overallcalculations for median and interquartile

interval (IQI),thus providing only one independent effect

size per study arm (these are referred to as data points). F

time–series studies without a concurrent comparison group

the effectsizes (using pretestmeasurements and the last

postintervention measurement provided) were calculated a

follows:

S294 Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300

www.ajpm-online.net

ing from stair use, which serves to improve energy balance

can,in combination with other forms of physical activity,

contribute to physiologic improvements that are,in turn,

related to longer-term health outcomes.

Selection of Outcomes for Review

The primary outcomes examined in this review were objec-

tive measurements of changes in the use of stairs during two

or more periods of time. Objective measurements were vi-

sual counts of people using the stairs or electronic counts

(from devices such as motion detectors). Some of the quali-

fying studies reported other outcomes which were examined

but are not presented in this report.

Selection of stair use as an outcome assumes that small

amounts ofphysicalactivity on a regular basis willhelp

improve the energy imbalance that affects large numbers of

people (particularly people who are sedentary and those

who are obese).Stair use typically involves ascending or

descending one to four flights per day. Using stairs expends

twice as much energy as using elevators8 with each stair

ascended burning approximately 0.11 kilocalorie and each

stair descended burning approximately 0.05 kilocalorie.9

Regular, substantial stair use (as many as six assents of 199

steps per assent per day for 12 weeks) has been shown to

improve cardiovascular outcomes among previously seden-

tary young women10and Benn et al., in their study of a small

group of older men found that

climbing only three to four flights of stairs at a mod-

erate pace (approximately 50 –70 s) elicits peak circu-

latory demands similar to, but at a much more rapid

rate ofadjustmentthan,10 minutes ofhorizontal

walking at2.5 mph,intermittently carrying a 30-

pound weight, or 4 minutes of walking up a moder-

ately steep slope.11

Over the long-term, this added energy expenditure could

contribute to improved energy balance and longer-term

health outcomes such as weight control.

Search Strategy

The articles considered for this review were obtained from

systematic searches of multiple databases, reviews of biblio-

graphic reference lists, and consultations with experts in the

fıeld. The team’s updated search for evidence encompassed

the period from 2000 to April 2005, which overlapped with

the search conducted for the originalCommunity Guide

review of these interventions (search period 1980 –2000).5

The original review used the following seven databases: En-

viroline, MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Social SciSearch, Sociologi-

cal Abstracts, Sportdiscus, and Transportation Research In-

formation Services (TRIS).For the team’s updated search,

the following 15 databaseswere examined:ArticleFirst,

CINAHL, EMBASE, Enviroline, Health Promotion and Edu-

cation Database, MEDLINE, Ovid, PsycINFO, PubMed, So-

cialSciSearch,SocialScience Citation Index,Sociological

Abstracts,SPORTDiscus,Transportation Research Infor-

mation Services (TRIS),and WorldCat.This list includes

some databases notavailable atthe time ofthe original

review.

Evaluating and Summarizing the Studies

Each study that met the inclusion criteria was evaluated fo

the suitability of the study design and study execution usin

the standardized Community Guide abstraction form.12The

suitability of each study design was rated as greatest, mod

erate, or least depending on the degree to which the desig

protects against threats to validity.The execution of each

study was rated as good,fair,or limited on the basis of

several predetermined factors that could potentially limit a

study’s utility for assessing effectiveness.Each study was

reviewed by at least two trained researchers. Concerns abo

study design and execution were discussed with an expert

physicalactivity interventions and differences in opinion

were resolved by consensus among a team of three system

atic reviewers (the coordination team).Only studies rated

greatest or moderate in design suitability and good or fair i

execution were considered qualifying studies and included

in the team’s fınal assessment of the evidence in this revie

Studies with limited execution are,by Community Guide

methods, excluded from consideration, and studies of least

suitable design were excluded by the coordination team

because the body of literature was adequately represented

with moderate and greatest suitability study designs.

Calculation of Effect Sizes

The qualifying studies provided measurements of change i

the number or proportion of people using the stairs before

and after the implementation of point-of-decision prompts

(with or without additional enhancements to the stairs or

stairwells).To facilitate comparison across studies and an

evaluation across the body of evidence, individual study ar

results were converted (if necessary) into measurements o

both absolute and relative percentage change.In addition,

whenever possible, a mean effect size was calculated on th

entire sample in each study arm.Studies contained more

than one study arm when there were multiple locations or

mechanismsof implementation forthe intervention.In

some cases,effectmeasures were reported for subgroup

means (e.g.,one for men and one for women).For these

study fındings, the mean of the subgroups was incorporate

into the overallcalculations for median and interquartile

interval (IQI),thus providing only one independent effect

size per study arm (these are referred to as data points). F

time–series studies without a concurrent comparison group

the effectsizes (using pretestmeasurements and the last

postintervention measurement provided) were calculated a

follows:

S294 Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300

www.ajpm-online.net

absolute percentage change (difference is described as “per-

centage point change”),

Effect size ⫽ Ipost⫺ Ipre;

relative percentage change (result is described as “percent-

age change”),

Effect size ⫽ ((Ipost⫺ Ipre)/I pre) ⫻ 100.

For the study thatincluded a concurrentcomparison

population (not exposed to the intervention), the effect size

was calculated as follows:

absolute percentage change (difference is described as “per-

centage point change”),

Effect size ⫽ (Ipost⫺ Ipre) ⫺ (Cpost⫺ Cpre);

relative percentage change (result is described as “percent-

age change”),

Effect size

⫽ ([(I post⫺ Ipre) ⫺ (Cpost⫺ Cpre)] ⁄ Ipre) ⫻ 100.

For all calculations, I ⫽ intervention group; C ⫽ comparison

group;and “pre” and “post” subscripts indicate measure-

ments taken before and after intervention implementation.

For studies in which multiple postintervention measure-

ments were taken, the measurement most distant from the

end of the intervention is used. In addition to the calculation

of effect sizes for each study,an overall median effect size

and interquartile interval were determined for both absolute

and relative percentage change.

Throughout the results section effect sizes are presented

as both absolute and relative change. The original review of

point-of-decision prompts5 reported relative change only;

thus relative change is reported in this paper to allow for

comparisons across reviews.Absolute change is also re-

ported because it provides an estimate of change that is not

dependent on baseline rates (that may vary according to

setting or other population characteristics).

Results

Part I: Interventions to Increase the Use of

Stairs (Updated)

The team examined the evidence from qualifying studies

for two related interventions:(1) point-of-decision

prompts;and (2)stairwellenhancements when com-

bined with point-of-decision prompts.

Review of Evidence: Point-of-Decision

Prompts

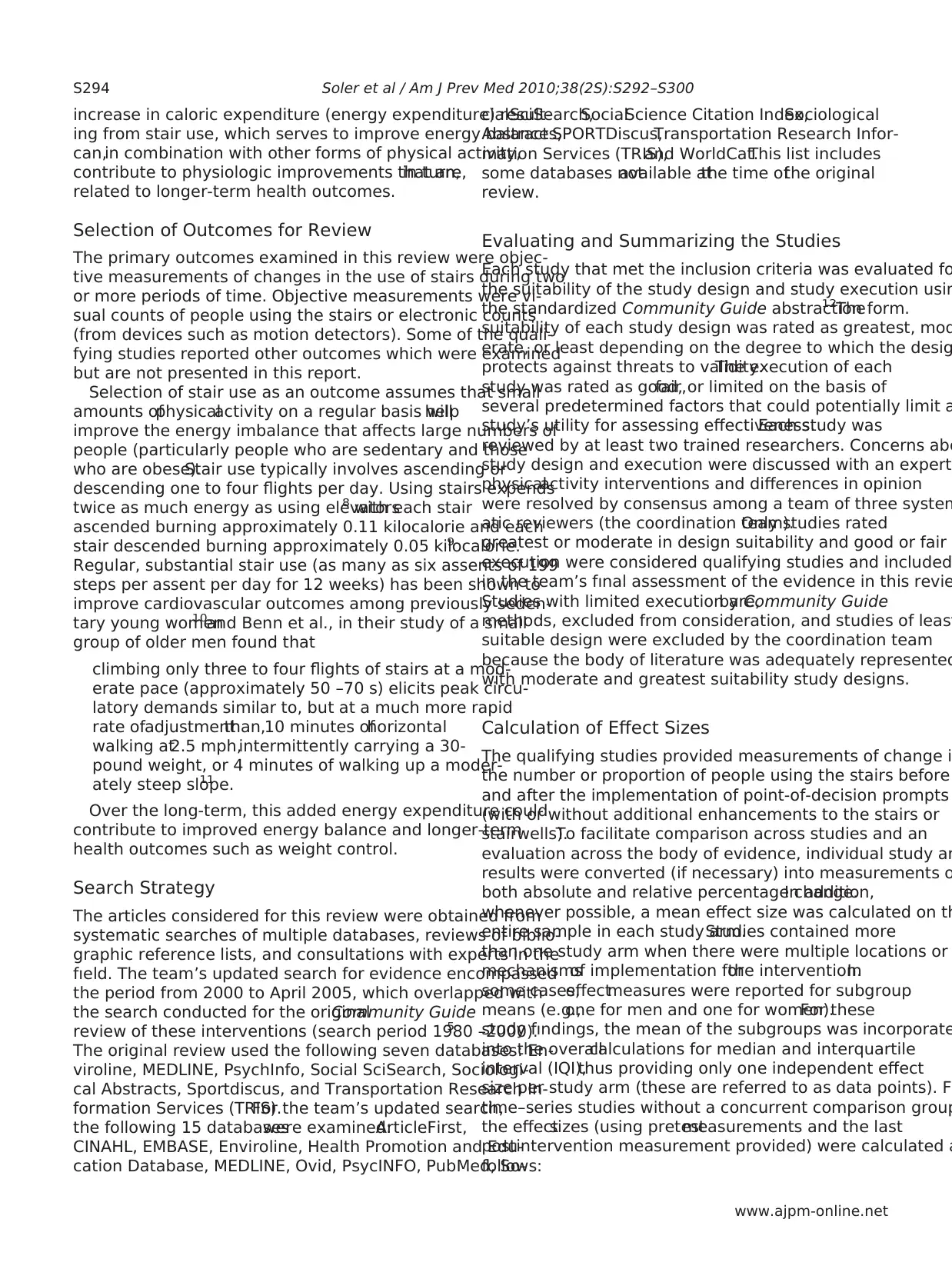

Point-of-decision prompts are motivational signs placed

on or near stairwells or at the base of elevators and esca-

lators encouraging people to use stairs. These signs, such

as the one shown in Figure 1, inform individuals about a

health or weight-loss benefıt from using stairs,about a

nearby opportunity to use stairs, or both. A few examp

of the content of the signs include “improve your wais

line, use the stairs” or “your heart needs exercise, use

stairs.” Point-of-decision signs may be combined with

prompts such as footprints placed to direct individuals

stairwell; the team considered these additional efforts

this review.Point-of-decision prompts when combined

with more elaborate enhancements to the stairs or sta

such as painting stairwell walls or playing music in sta

are reviewed separately below.

Effectiveness.The literature search identifıed 15 stud-

ies thatassessed the effectiveness ofpoint-of-decision

prompts when used alone in changing the frequency o

amount of stair use or the number of stair users.13–27

Four

of these studies were rated as having least suitable st

designs and were excluded from further analysis.21–24

Figure 1.Sample point-of-decision prompt

Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300 S295

February 2010

centage point change”),

Effect size ⫽ Ipost⫺ Ipre;

relative percentage change (result is described as “percent-

age change”),

Effect size ⫽ ((Ipost⫺ Ipre)/I pre) ⫻ 100.

For the study thatincluded a concurrentcomparison

population (not exposed to the intervention), the effect size

was calculated as follows:

absolute percentage change (difference is described as “per-

centage point change”),

Effect size ⫽ (Ipost⫺ Ipre) ⫺ (Cpost⫺ Cpre);

relative percentage change (result is described as “percent-

age change”),

Effect size

⫽ ([(I post⫺ Ipre) ⫺ (Cpost⫺ Cpre)] ⁄ Ipre) ⫻ 100.

For all calculations, I ⫽ intervention group; C ⫽ comparison

group;and “pre” and “post” subscripts indicate measure-

ments taken before and after intervention implementation.

For studies in which multiple postintervention measure-

ments were taken, the measurement most distant from the

end of the intervention is used. In addition to the calculation

of effect sizes for each study,an overall median effect size

and interquartile interval were determined for both absolute

and relative percentage change.

Throughout the results section effect sizes are presented

as both absolute and relative change. The original review of

point-of-decision prompts5 reported relative change only;

thus relative change is reported in this paper to allow for

comparisons across reviews.Absolute change is also re-

ported because it provides an estimate of change that is not

dependent on baseline rates (that may vary according to

setting or other population characteristics).

Results

Part I: Interventions to Increase the Use of

Stairs (Updated)

The team examined the evidence from qualifying studies

for two related interventions:(1) point-of-decision

prompts;and (2)stairwellenhancements when com-

bined with point-of-decision prompts.

Review of Evidence: Point-of-Decision

Prompts

Point-of-decision prompts are motivational signs placed

on or near stairwells or at the base of elevators and esca-

lators encouraging people to use stairs. These signs, such

as the one shown in Figure 1, inform individuals about a

health or weight-loss benefıt from using stairs,about a

nearby opportunity to use stairs, or both. A few examp

of the content of the signs include “improve your wais

line, use the stairs” or “your heart needs exercise, use

stairs.” Point-of-decision signs may be combined with

prompts such as footprints placed to direct individuals

stairwell; the team considered these additional efforts

this review.Point-of-decision prompts when combined

with more elaborate enhancements to the stairs or sta

such as painting stairwell walls or playing music in sta

are reviewed separately below.

Effectiveness.The literature search identifıed 15 stud-

ies thatassessed the effectiveness ofpoint-of-decision

prompts when used alone in changing the frequency o

amount of stair use or the number of stair users.13–27

Four

of these studies were rated as having least suitable st

designs and were excluded from further analysis.21–24

Figure 1.Sample point-of-decision prompt

Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300 S295

February 2010

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Two of the studies19,25

were of good execution;the re-

maining nine13–18,20,26,27

were rated as fair.One addi-

tionalpaper provided information on a study already

included in the review.28 Details ofthe 11 qualifying

studies,including a summary ofthe content,delivery,

evaluation design,and outcomes,are available at www.

thecommunityguide.org/pa/environmental-policy/

podp.html.

Study design and implementationcharacteris-

tics. All 11 qualifying studies used time–series designs,

and were rated as being of moderate suitability.13–20,25–27

All of the qualifying studies were conducted between

1980 and 2003, and measured stair use in adult popula-

tions. The types of point-of-decision prompts used in the

qualifyingstudiesweresigns13–19,26,27

or banners,20

which were distinctions used by the authors and not

necessarily related to the size of the prompt, although in

the one study specifying stair banners, the messages were

physically placed on each stair, but like the signs, varied in

design and message.The 11 qualifying studies imple-

mented a variety of point-of-decision prompts messages

such as health benefıts and health promotion,13,14,16 –18,25

weight control,14 and signs (in Spanish and English)

using eitheran individualor family perspective to

specifıcally targetthe Hispanic community.19 One

study focused primarily on African-Americans,and

the point-of-decision prompt was tailored to this partic-

ular community.15Additionally, in one study a deterrent

sign was displayed that limited the elevator to use by the

staff and the physically challenged.26

Outcomes Related to Stair Use

Eleven qualifying studies,13–20,25–27

consisting of 21 study

arms for stair use, provided evidence in terms of absolute

(i.e., percentage point) change. In these studies, the base-

line rates of stair use ranged from 1.7% to 39.7% of po-

tential users (median⫽8.2, IQI⫽5.2, 21.2). Stair use dur-

ing the intervention period in these study arms ranged

from 4.0% to 41.9% ofpotentialusers.The median

change for the 21 study arms representing these studies

was an increase in stair use of2.4 percentage points

(IQI⫽0.83, 6.7 percentage points).Increases in stair

use in 15 of 21 study arms were reported as statistically

signifıcant,14 –20,22–28

while two study arms (from the

same study)reported a signifıcantdecrease in stair

use.19

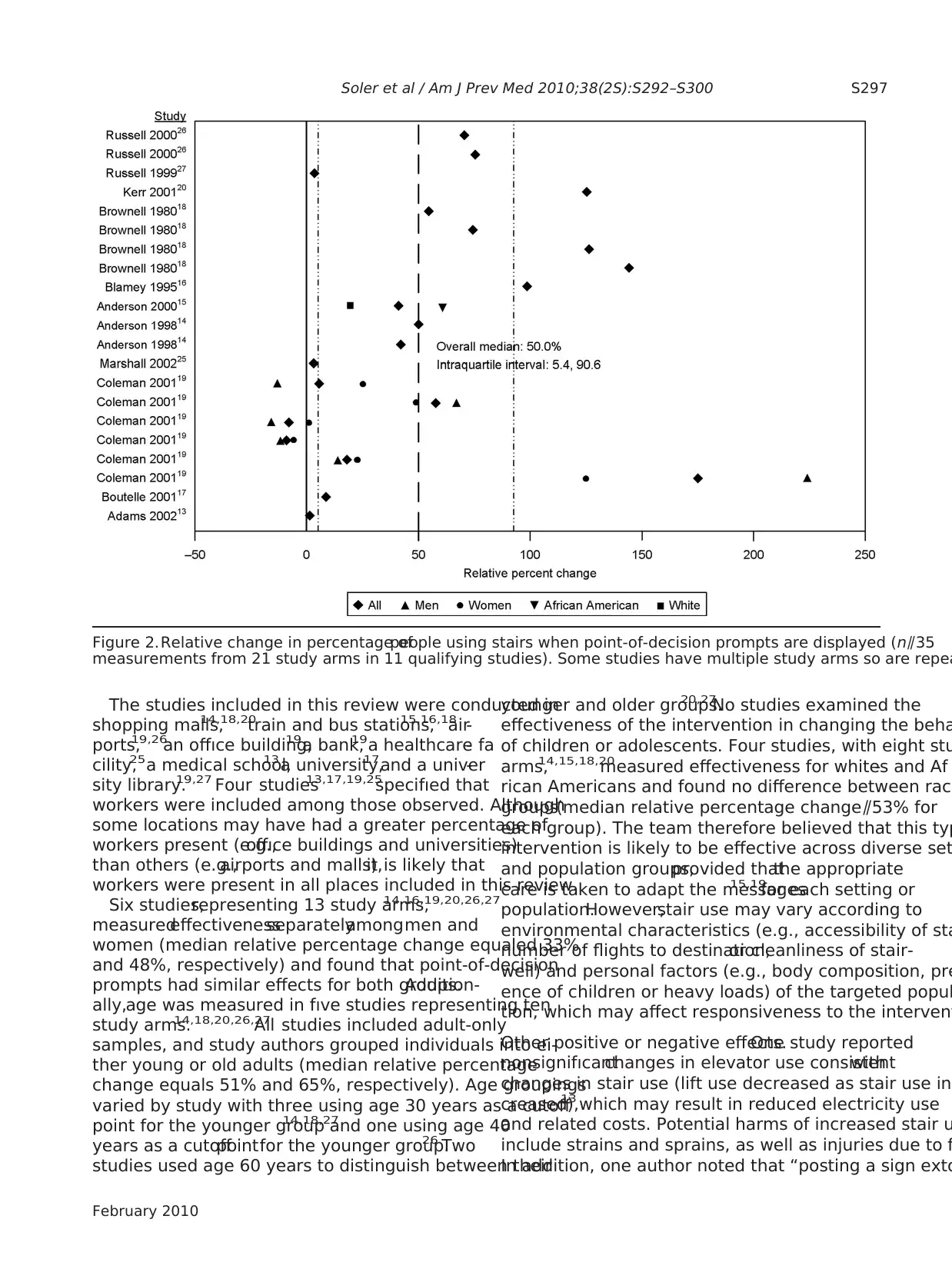

To examine effects relative to baseline stair use, eleven

qualifying studies that included 21 study arms for stair

use were evaluated in terms of relative (i.e., percentage)

change.13–20,25–27

The majority of studies reported a low

levelof baseline stair use (⬍20%).Overall,in the 11

qualifying studies,the median relative improvement in

observed stair use was 50 percentage points (IQI⫽5.4%,

90.6%) from baseline (Figure 2; note that data points for

subpopulations and simple means for the total sample a

included on this fıgure).

The team examined how the effectiveness of point-of-

decision prompts, measured in units of absolute change

varied with baseline stair use and found no signifıcant

relationship between baseline stairuse and absolute

change (Spearman’srho ⫺⫽ 0.39,n⫽21 data points,

p⫽0.77).

The team also examined the effectiveness of point-of-

decision prompts by the period of observation. Research

ers in nine of the studies(representing18 study

arms)13,17–20,25–27

left point-of-decision prompts in place

and observed passersby for different lengths of time, wit

observation periodsranging from 1 week (relative

change⫽81.1%)26to 12 weeks (relative change⫽5.16%).25

The period of observation was not reported for two quali

ing studies representing three study arms.14,15

There was no

signifıcant relationship between the period of observatio

and relative change in stair use (Spearman’s rho ⫺⫽ 0.12

n⫽18 data points, p⫽0.65).

Overall, 25 of the 28 data points representing 17 study

arms (ten studies) in this body of evidence reported fınd

ings in favor of the intervention.For some studies the

statistical signifıcance of the results was not reported, an

for some, the fındings differed by direction for subgroup

Among those studies with fındings in favor of the inter-

vention, at the individual level the actual increase in sta

use was modest. Because using stairs is a physical activ

that can be done by most people in most places where

stairs are present,modest increases in stair use among

populations ofadults across settings (malls,worksites,

libraries,and other such facilities) and across time can

contribute to or extend bouts of physical activity and ma

have a positive effect on energy balance.

Applicability.The body of evidence used to evaluate the

applicability ofthis intervention was the same as that

used to evaluate effectiveness.Seven studies were con-

ducted in the U.S.,14,15,17–19,26,27

two were conducted in

the United Kingdom,13,20

and one study each was con-

ducted in Scotland specifıcally16 and in Australia.25

Point-of-decision prompts were evaluated in a range of

settings, and two studies investigated the effectiveness

the same intervention in different locations.18,19

Baseline

use of stairs differed across settings (e.g., buildings with

single or multiple flights of stairs,public locations and

worksites), and the effectiveness of the intervention also

varied across settings,suggesting that the goal (e.g.,lei-

sure activity or work), or type of dress (e.g., suit or work

shoes) of people in certain types of locations may have a

impact on the effectiveness of the intervention.

S296 Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300

www.ajpm-online.net

were of good execution;the re-

maining nine13–18,20,26,27

were rated as fair.One addi-

tionalpaper provided information on a study already

included in the review.28 Details ofthe 11 qualifying

studies,including a summary ofthe content,delivery,

evaluation design,and outcomes,are available at www.

thecommunityguide.org/pa/environmental-policy/

podp.html.

Study design and implementationcharacteris-

tics. All 11 qualifying studies used time–series designs,

and were rated as being of moderate suitability.13–20,25–27

All of the qualifying studies were conducted between

1980 and 2003, and measured stair use in adult popula-

tions. The types of point-of-decision prompts used in the

qualifyingstudiesweresigns13–19,26,27

or banners,20

which were distinctions used by the authors and not

necessarily related to the size of the prompt, although in

the one study specifying stair banners, the messages were

physically placed on each stair, but like the signs, varied in

design and message.The 11 qualifying studies imple-

mented a variety of point-of-decision prompts messages

such as health benefıts and health promotion,13,14,16 –18,25

weight control,14 and signs (in Spanish and English)

using eitheran individualor family perspective to

specifıcally targetthe Hispanic community.19 One

study focused primarily on African-Americans,and

the point-of-decision prompt was tailored to this partic-

ular community.15Additionally, in one study a deterrent

sign was displayed that limited the elevator to use by the

staff and the physically challenged.26

Outcomes Related to Stair Use

Eleven qualifying studies,13–20,25–27

consisting of 21 study

arms for stair use, provided evidence in terms of absolute

(i.e., percentage point) change. In these studies, the base-

line rates of stair use ranged from 1.7% to 39.7% of po-

tential users (median⫽8.2, IQI⫽5.2, 21.2). Stair use dur-

ing the intervention period in these study arms ranged

from 4.0% to 41.9% ofpotentialusers.The median

change for the 21 study arms representing these studies

was an increase in stair use of2.4 percentage points

(IQI⫽0.83, 6.7 percentage points).Increases in stair

use in 15 of 21 study arms were reported as statistically

signifıcant,14 –20,22–28

while two study arms (from the

same study)reported a signifıcantdecrease in stair

use.19

To examine effects relative to baseline stair use, eleven

qualifying studies that included 21 study arms for stair

use were evaluated in terms of relative (i.e., percentage)

change.13–20,25–27

The majority of studies reported a low

levelof baseline stair use (⬍20%).Overall,in the 11

qualifying studies,the median relative improvement in

observed stair use was 50 percentage points (IQI⫽5.4%,

90.6%) from baseline (Figure 2; note that data points for

subpopulations and simple means for the total sample a

included on this fıgure).

The team examined how the effectiveness of point-of-

decision prompts, measured in units of absolute change

varied with baseline stair use and found no signifıcant

relationship between baseline stairuse and absolute

change (Spearman’srho ⫺⫽ 0.39,n⫽21 data points,

p⫽0.77).

The team also examined the effectiveness of point-of-

decision prompts by the period of observation. Research

ers in nine of the studies(representing18 study

arms)13,17–20,25–27

left point-of-decision prompts in place

and observed passersby for different lengths of time, wit

observation periodsranging from 1 week (relative

change⫽81.1%)26to 12 weeks (relative change⫽5.16%).25

The period of observation was not reported for two quali

ing studies representing three study arms.14,15

There was no

signifıcant relationship between the period of observatio

and relative change in stair use (Spearman’s rho ⫺⫽ 0.12

n⫽18 data points, p⫽0.65).

Overall, 25 of the 28 data points representing 17 study

arms (ten studies) in this body of evidence reported fınd

ings in favor of the intervention.For some studies the

statistical signifıcance of the results was not reported, an

for some, the fındings differed by direction for subgroup

Among those studies with fındings in favor of the inter-

vention, at the individual level the actual increase in sta

use was modest. Because using stairs is a physical activ

that can be done by most people in most places where

stairs are present,modest increases in stair use among

populations ofadults across settings (malls,worksites,

libraries,and other such facilities) and across time can

contribute to or extend bouts of physical activity and ma

have a positive effect on energy balance.

Applicability.The body of evidence used to evaluate the

applicability ofthis intervention was the same as that

used to evaluate effectiveness.Seven studies were con-

ducted in the U.S.,14,15,17–19,26,27

two were conducted in

the United Kingdom,13,20

and one study each was con-

ducted in Scotland specifıcally16 and in Australia.25

Point-of-decision prompts were evaluated in a range of

settings, and two studies investigated the effectiveness

the same intervention in different locations.18,19

Baseline

use of stairs differed across settings (e.g., buildings with

single or multiple flights of stairs,public locations and

worksites), and the effectiveness of the intervention also

varied across settings,suggesting that the goal (e.g.,lei-

sure activity or work), or type of dress (e.g., suit or work

shoes) of people in certain types of locations may have a

impact on the effectiveness of the intervention.

S296 Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300

www.ajpm-online.net

The studies included in this review were conducted in

shopping malls,14,18,20

train and bus stations,15,16,18

air-

ports,19,26

an offıce building,19a bank,19a healthcare fa-

cility,25a medical school,13a university,17and a univer-

sity library.19,27 Four studies13,17,19,25

specifıed that

workers were included among those observed. Although

some locations may have had a greater percentage of

workers present (e.g.,offıce buildings and universities)

than others (e.g.,airports and malls),it is likely that

workers were present in all places included in this review.

Six studies,representing 13 study arms,14,16,19,20,26,27

measuredeffectivenessseparatelyamongmen and

women (median relative percentage change equaled 33%

and 48%, respectively) and found that point-of-decision

prompts had similar effects for both groups.Addition-

ally,age was measured in fıve studies representing ten

study arms.14,18,20,26,27

All studies included adult-only

samples, and study authors grouped individuals into ei-

ther young or old adults (median relative percentage

change equals 51% and 65%, respectively). Age groupings

varied by study with three using age 30 years as a cutoff

point for the younger group14,18,27

and one using age 40

years as a cutoffpointfor the younger group.26 Two

studies used age 60 years to distinguish between their

younger and older groups.20,27

No studies examined the

effectiveness of the intervention in changing the beha

of children or adolescents. Four studies, with eight stu

arms,14,15,18,20

measured effectiveness for whites and Af-

rican Americans and found no difference between raci

groups(median relative percentage change⫽53% for

each group). The team therefore believed that this typ

intervention is likely to be effective across diverse set

and population groups,provided thatthe appropriate

care is taken to adapt the messages15,19

for each setting or

population.However,stair use may vary according to

environmental characteristics (e.g., accessibility of sta

number of flights to destination,or cleanliness of stair-

well) and personal factors (e.g., body composition, pre

ence of children or heavy loads) of the targeted popul

tion, which may affect responsiveness to the intervent

Other positive or negative effects.One study reported

nonsignifıcantchanges in elevator use consistentwith

changes in stair use (lift use decreased as stair use in

creased),13 which may result in reduced electricity use

and related costs. Potential harms of increased stair u

include strains and sprains, as well as injuries due to f

In addition, one author noted that “posting a sign exto

Figure 2.Relative change in percentage ofpeople using stairs when point-of-decision prompts are displayed (n⫽35

measurements from 21 study arms in 11 qualifying studies). Some studies have multiple study arms so are repea

Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300 S297

February 2010

shopping malls,14,18,20

train and bus stations,15,16,18

air-

ports,19,26

an offıce building,19a bank,19a healthcare fa-

cility,25a medical school,13a university,17and a univer-

sity library.19,27 Four studies13,17,19,25

specifıed that

workers were included among those observed. Although

some locations may have had a greater percentage of

workers present (e.g.,offıce buildings and universities)

than others (e.g.,airports and malls),it is likely that

workers were present in all places included in this review.

Six studies,representing 13 study arms,14,16,19,20,26,27

measuredeffectivenessseparatelyamongmen and

women (median relative percentage change equaled 33%

and 48%, respectively) and found that point-of-decision

prompts had similar effects for both groups.Addition-

ally,age was measured in fıve studies representing ten

study arms.14,18,20,26,27

All studies included adult-only

samples, and study authors grouped individuals into ei-

ther young or old adults (median relative percentage

change equals 51% and 65%, respectively). Age groupings

varied by study with three using age 30 years as a cutoff

point for the younger group14,18,27

and one using age 40

years as a cutoffpointfor the younger group.26 Two

studies used age 60 years to distinguish between their

younger and older groups.20,27

No studies examined the

effectiveness of the intervention in changing the beha

of children or adolescents. Four studies, with eight stu

arms,14,15,18,20

measured effectiveness for whites and Af-

rican Americans and found no difference between raci

groups(median relative percentage change⫽53% for

each group). The team therefore believed that this typ

intervention is likely to be effective across diverse set

and population groups,provided thatthe appropriate

care is taken to adapt the messages15,19

for each setting or

population.However,stair use may vary according to

environmental characteristics (e.g., accessibility of sta

number of flights to destination,or cleanliness of stair-

well) and personal factors (e.g., body composition, pre

ence of children or heavy loads) of the targeted popul

tion, which may affect responsiveness to the intervent

Other positive or negative effects.One study reported

nonsignifıcantchanges in elevator use consistentwith

changes in stair use (lift use decreased as stair use in

creased),13 which may result in reduced electricity use

and related costs. Potential harms of increased stair u

include strains and sprains, as well as injuries due to f

In addition, one author noted that “posting a sign exto

Figure 2.Relative change in percentage ofpeople using stairs when point-of-decision prompts are displayed (n⫽35

measurements from 21 study arms in 11 qualifying studies). Some studies have multiple study arms so are repea

Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300 S297

February 2010

ling the benefıts of climbing one flight of stairs may con-

vey false information. It may lead people to believe that a

single 30-second climb willsubstantially improve their

health.”29

Economic efficiency.For this updated review, a search

of literature on economic effectiveness was conducted.

No studies were found thatmetthe requirements for

inclusion in a Community Guide review.30

Barriers to intervention implementation.Few studies

reviewed indicated specifıc barriers to successful imple-

mentation of the intervention. One author reported un-

authorized removalof prompts from stairwells.13 An-

otherreported thatthe flooron which an employee

worked affected stair use, suggesting that the more stairs

one has to ascend,the less effective the intervention

might be.24Additionally, some stairwells are locked and

others may be diffıcultto fınd,poorly lit,or notwell

maintained.17Some institutions may have fıre codes and

other policies restricting the placement ofprompts or

posters in public areas. Choice of dress (e.g., high-heeled

shoes) may also serve as barriers to stair use and may

increase general risk of using the stairs.

Summary and Discussion: Effectiveness

of Point-of-Decision Prompts

In general, the qualifying studies identifıed in this review

reported a low level of observed baseline use of stairs, and

small but signifıcant increases in the use of stairs follow-

ing the implementation ofpoint-of-decision prompts.

Although absolute changes were small, these differences

representmodestrelative improvements in the use of

stairs. In general, the lower the level of baseline use, the

greater the improvements in use. The duration of obser-

vation reported in the qualifying studies was relatively

short, with a maximum observation period of 12 weeks.

The team had little evidence with which to evaluate the

long-term impact of these interventions on stair use, and

there was no signifıcant association between length of

observation periods and changes in stair use.

The venue in which the prompt is placed may also

influence the amount of exposure. Some locations, such

as malls and airports,have populations that (with the

exception of a limited number of employees) likely do not

return from one day to the next; whereas other locations,

such as offıce buildings and commuter train stations,

likely have populations that return—and therefore are

exposed to the prompts— day after day.None of these

studies examined the impact that repeated exposure to

prompts may have on stair use— clearly an area for future

research.

Conclusion

According to Community Guide rules of evidence,7 this

review provides strong evidence that point-of-decision

prompts contribute to modest increases in the percentag

of people choosing to take the stairs rather than an elev

tor or escalator. The observed increases in the use of sta

may contribute to a modest improvement in daily physi-

cal activity that would have a cumulative effect on calor

expenditure and, in turn, energy balance.

Review of Evidence: Stair or Stairwell

Enhancements when Combined with

Point-of-Decision Prompts

Enhancement of stairs or stairwells when combined with

point-of-decision prompts was also examined as part of

this update review. This intervention includes modifying

stairwells through one or more of the following: painting

walls, laying carpet, adding artwork, and playing music.

This intervention may indirectly increase the effective-

ness of point-of-decision prompts by changing attitudes

about stair use (or a particular stairwell).

Effectiveness.The team identifıed two studies17,31

that

assessed theeffectivenessof stairwellenhancements

when combined with point-of-decision promptsin

changing frequency of stair use,as measured by mean

number of trips per person per day and percentage of

people using the stairs. Both of these studies used time–

series designs, were rated as moderate in suitability, an

were evaluated as being of fair execution. Details of the

two qualifying studies, including a summary of the con-

tent, delivery, evaluation design, and outcomes, are ava

able atwww.thecommunityguide.org/pa/environmental-

policy/podp.html.

Study design and implementationcharacteris-

tics. Both studies reviewed investigated the impact of

environmental change on stair use. One study31reported

a long-term evaluation during which a stairwellwas

painted and carpeted,artwork was placed on the walls

of landings,point-of-decision promptswereposted

throughout the building and on the computer kiosk in th

lobby, and fınally, music was piped in. This intervention

was implemented in stages where cumulative effects we

examined (effectiveness was evaluated after new carpet

and paint were added,and then again after adding art-

work). In the second study, the effectiveness of prompts

alone and the effectiveness of prompts plus adding art-

work and music to the stairwell were examined.17For this

study, the prompts-alone condition was included in the

review described above. One study was conducted in an

offıce building31and the other was conducted in a univer-

sity building.17Both studies were conducted in the U.S.

S298 Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300

www.ajpm-online.net

vey false information. It may lead people to believe that a

single 30-second climb willsubstantially improve their

health.”29

Economic efficiency.For this updated review, a search

of literature on economic effectiveness was conducted.

No studies were found thatmetthe requirements for

inclusion in a Community Guide review.30

Barriers to intervention implementation.Few studies

reviewed indicated specifıc barriers to successful imple-

mentation of the intervention. One author reported un-

authorized removalof prompts from stairwells.13 An-

otherreported thatthe flooron which an employee

worked affected stair use, suggesting that the more stairs

one has to ascend,the less effective the intervention

might be.24Additionally, some stairwells are locked and

others may be diffıcultto fınd,poorly lit,or notwell

maintained.17Some institutions may have fıre codes and

other policies restricting the placement ofprompts or

posters in public areas. Choice of dress (e.g., high-heeled

shoes) may also serve as barriers to stair use and may

increase general risk of using the stairs.

Summary and Discussion: Effectiveness

of Point-of-Decision Prompts

In general, the qualifying studies identifıed in this review

reported a low level of observed baseline use of stairs, and

small but signifıcant increases in the use of stairs follow-

ing the implementation ofpoint-of-decision prompts.

Although absolute changes were small, these differences

representmodestrelative improvements in the use of

stairs. In general, the lower the level of baseline use, the

greater the improvements in use. The duration of obser-

vation reported in the qualifying studies was relatively

short, with a maximum observation period of 12 weeks.

The team had little evidence with which to evaluate the

long-term impact of these interventions on stair use, and

there was no signifıcant association between length of

observation periods and changes in stair use.

The venue in which the prompt is placed may also

influence the amount of exposure. Some locations, such

as malls and airports,have populations that (with the

exception of a limited number of employees) likely do not

return from one day to the next; whereas other locations,

such as offıce buildings and commuter train stations,

likely have populations that return—and therefore are

exposed to the prompts— day after day.None of these

studies examined the impact that repeated exposure to

prompts may have on stair use— clearly an area for future

research.

Conclusion

According to Community Guide rules of evidence,7 this

review provides strong evidence that point-of-decision

prompts contribute to modest increases in the percentag

of people choosing to take the stairs rather than an elev

tor or escalator. The observed increases in the use of sta

may contribute to a modest improvement in daily physi-

cal activity that would have a cumulative effect on calor

expenditure and, in turn, energy balance.

Review of Evidence: Stair or Stairwell

Enhancements when Combined with

Point-of-Decision Prompts

Enhancement of stairs or stairwells when combined with

point-of-decision prompts was also examined as part of

this update review. This intervention includes modifying

stairwells through one or more of the following: painting

walls, laying carpet, adding artwork, and playing music.

This intervention may indirectly increase the effective-

ness of point-of-decision prompts by changing attitudes

about stair use (or a particular stairwell).

Effectiveness.The team identifıed two studies17,31

that

assessed theeffectivenessof stairwellenhancements

when combined with point-of-decision promptsin

changing frequency of stair use,as measured by mean

number of trips per person per day and percentage of

people using the stairs. Both of these studies used time–

series designs, were rated as moderate in suitability, an

were evaluated as being of fair execution. Details of the

two qualifying studies, including a summary of the con-

tent, delivery, evaluation design, and outcomes, are ava

able atwww.thecommunityguide.org/pa/environmental-

policy/podp.html.

Study design and implementationcharacteris-

tics. Both studies reviewed investigated the impact of

environmental change on stair use. One study31reported

a long-term evaluation during which a stairwellwas

painted and carpeted,artwork was placed on the walls

of landings,point-of-decision promptswereposted

throughout the building and on the computer kiosk in th

lobby, and fınally, music was piped in. This intervention

was implemented in stages where cumulative effects we

examined (effectiveness was evaluated after new carpet

and paint were added,and then again after adding art-

work). In the second study, the effectiveness of prompts

alone and the effectiveness of prompts plus adding art-

work and music to the stairwell were examined.17For this

study, the prompts-alone condition was included in the

review described above. One study was conducted in an

offıce building31and the other was conducted in a univer-

sity building.17Both studies were conducted in the U.S.

S298 Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300

www.ajpm-online.net

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Outcomes related to stair use.There was not enough

evidence in this body of literature to draw conclusions

about effectiveness.In the study conducted in an offıce

building,all interventions (paint,carpet,art,signs,and

music) together led to a relative increase in stair use of

8.8% (baseline use: M⫽2.14 trips per day per occupant).31

The other study examined the effectiveness of point-of-

decision prompts with artwork and music and reported a

39.6% relative increase in stair use (percentage of people

using stairs at baseline: 11.1%).17

Barriers to intervention implementation.Fire code

regulations may limit or preclude enhancements to stairs

and stairwells.The qualifying studies did notprovide

additional information on barriers to implementation of

these interventions.

Conclusion

According to the Community Guide’s rules of evidence,7

there is insuffıcient evidence to determine the effective-

ness of point-of-decision prompts in encouraging stair

use when combined with stair or stairwell enhancements.

Two studies of moderate suitability were identifıed.Al-

though both observed improvements in stair use over the

period ofobservation (relative percentage changes of

8.8% in trips per person per day and 39.6% of people

using the stairs),more research is needed to determine

the effects of this intervention on stair use.

Research Issues

Informationalapproachesto increasingphysical

activity.

Effectiveness.This review established the effectiveness

of point-of-decision promptsto encourage stairuse.

However, important research issues regarding the effec-

tiveness ofthese interventions remain.Many research

questions from the fırstCommunity Guide review of

point-of-decision prompts5have been addressed in more

recent studies.However,some questions have not been

addressed and others emerged from this update.

● What effect does varying the message or format of the

prompthave on providing a “booster” to stair use

among the targeted population?

● What type of prompt is most effective? What effect

does format or size have, if any?

● Is there a “critical distance” from the elevator or esca-

lator to the stairs, in which the effect of signage on stair

use is reduced?

● Are there a minimum or maximum number of flights

one must expect stair users to ascend in order for the

prompt to be effective?

● How many individualsread thepoint-of-decision

prompt and react (i.e., increase their use of the stair

a result, as opposed to reacting to other knowledge

the intervention is occurring?

● What strategies can be used to maintain the interve

tion effect after the intervention ends? Are periodic

“boosters” necessary or helpful?

Economic evaluations.The available economic data

were limited.Therefore,considerable research is war-

ranted on the following questions.

● What is the cost effectiveness of each of these seem

ingly low-cost interventions?

● How can effectiveness in terms of health outcomes o

quality adjusted health outcomes be better measure

estimated, or modeled?

Summary

In this article, the team reported results from an upda

review ofpoint-of-decision prompts thatincluded an

additional review of stair or stairwell enhancements w

used with point-of-decision prompts.The inclusion of

more recent studies provides strong evidence of effec

ness of the point-of-decision prompt intervention in in

creasing the use of stairs. On average these improvem

represent a modest improvement in stair use.Point-of-

decision prompts may represent a simple, lower-cost o

tion to increase physical activity in some settings. The

was insuffıcient evidence to draw a conclusion regardi

the effectiveness of stair or stairwell enhancements w

used with point-of-decision prompts. Despite the inclu

sion of additional studies, there remain important gap

understanding of the effectiveness of these interventi

in some settings (such as worksites), and the contribu

of these interventions to overallphysicalactivity and

physical fıtness.

The team thanks the following individuals for their con

tributions to this review: Reba Norman, research librar

ian;Kate W.Harris and Tony Pearson-Clarke,editors;

and the team’s Coordination Team:Nico Pronk,PhD,

Health Partners, Minneapolis MN; Dennis Richling, MD,

CorSolutions, Chicago IL; Deborah R. Bauer, RN, MPH,

NationalCenter for Chronic Disease Prevention and

Health Promotion, CDC, Atlanta GA; Andrew Walker,

Private Consultant,Atlanta GA; Abby Rosenthal,

MPH, Offıce on Smoking and Health, CDC, Atlanta GA;

Curtis S.Florence,II PhD, Emory University,Atlanta

GA; and Deborah MacLean,The Coca-Cola Company,

Atlanta GA.

The names and affıliations of the Task Force membe

are listed in the front of this supplementand at

www.thecommunityguide.org.

Soler et al / Am J Prev Med 2010;38(2S):S292–S300 S299

February 2010

evidence in this body of literature to draw conclusions

about effectiveness.In the study conducted in an offıce

building,all interventions (paint,carpet,art,signs,and

music) together led to a relative increase in stair use of

8.8% (baseline use: M⫽2.14 trips per day per occupant).31

The other study examined the effectiveness of point-of-

decision prompts with artwork and music and reported a

39.6% relative increase in stair use (percentage of people

using stairs at baseline: 11.1%).17

Barriers to intervention implementation.Fire code

regulations may limit or preclude enhancements to stairs

and stairwells.The qualifying studies did notprovide

additional information on barriers to implementation of

these interventions.

Conclusion

According to the Community Guide’s rules of evidence,7

there is insuffıcient evidence to determine the effective-

ness of point-of-decision prompts in encouraging stair

use when combined with stair or stairwell enhancements.

Two studies of moderate suitability were identifıed.Al-

though both observed improvements in stair use over the

period ofobservation (relative percentage changes of

8.8% in trips per person per day and 39.6% of people

using the stairs),more research is needed to determine

the effects of this intervention on stair use.

Research Issues

Informationalapproachesto increasingphysical

activity.