Power System Frequency Control using Simplified Models Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2020/05/08

|13

|1800

|261

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment delves into the intricacies of power system frequency control, examining how different generation source mixes affect performance. The analysis encompasses synchronous and asynchronous generation, exploring the impact of governor droop and inertia constants. The student utilized MATLAB Simulink to simulate system responses, derive equations of motion, and compare simulated results with mathematical derivations. The assignment investigates the effects of adding governors to synchronous generators and the resulting system-frequency response with primary frequency control. Furthermore, the study explores factors influencing system frequency response, such as inertia constant and governor droop, and evaluates the effects of reducing the proportion of online synchronous generation capacity. The conclusion summarizes the key findings and highlights the influence of various parameters on system frequency stability and control.

POWER SYSTEM FREQUENCY CONTROL USING SIMPLIFIED MODELS.

BY (STUDENT NAME)

CLASS (COURSE) NAME:

TUTOR (PROFESSOR):

SCHOOL NAME:

THE CITY/STATE:

DATE:

BY (STUDENT NAME)

CLASS (COURSE) NAME:

TUTOR (PROFESSOR):

SCHOOL NAME:

THE CITY/STATE:

DATE:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table of Contents

Introduction...................................................................................................................... 3

Answers to given questions............................................................................................. 4

Part a) Equation of motion............................................................................................4

Part b) System-frequency response without frequency-control....................................6

Part c) Compare the simulated response with mathematically derived response.........7

Part d) Addition of governors to synchronous generators.............................................8

Part e): System-frequency response with primary frequency control..........................11

Part f) factors influencing system frequency response...............................................13

Conclusion..................................................................................................................... 14

Introduction...................................................................................................................... 3

Answers to given questions............................................................................................. 4

Part a) Equation of motion............................................................................................4

Part b) System-frequency response without frequency-control....................................6

Part c) Compare the simulated response with mathematically derived response.........7

Part d) Addition of governors to synchronous generators.............................................8

Part e): System-frequency response with primary frequency control..........................11

Part f) factors influencing system frequency response...............................................13

Conclusion..................................................................................................................... 14

Introduction.

The aim of this assignment is to investigate how a system frequency control system

performs as the mix of generation sources are varied. The performance for different proportions

of synchronous and asynchronous generation is performed, to how the frequency control

systems performs for different proportions of generation with frequency control using total online

generation capacity Sb [ MW ]

The total online generation capacity is divided into two (2) which include the online

synchronous Ssb and online non-synchronous Sabgeneration capacity. Thus, total online

generation is given by:

Sb =Ssb +Sab

Where Ssb =αb SbandSab= ( 1−αb ) Sb, given that α bis the specified proportion of the total

online generation capacity which is synchronous.

Ssb is divided into the proportion of online synchronous generation capacity with primary

governing control Sspb=α spb Ssb and the balance of online synchronous generation capacity is

ungoverned S¿=1−αspb, therefore:. Ssb =Sspb+ S¿. In this assignment the system is assumed to

be ungoverned.

The initial power output from each of the generation sources is specified where the initial

system load is determined. The initial power output from the online synchronous generation with

primary speed control is specified as a fraction βsb of the specified online capacity Sspb. The initial

power output as pu (per unit) is given as:

Pms p0

=βsp ( Sspb

Sb )=βsp ( αspb Ssb

Sb )=β sp ( α spb αb ) ∈ puof Sb

The other types of generation as pu are given as:

Pms u0

=βsu ( 1−αspb ) αbPma u0

=βau (1−αb )

The aim of this assignment is to investigate how a system frequency control system

performs as the mix of generation sources are varied. The performance for different proportions

of synchronous and asynchronous generation is performed, to how the frequency control

systems performs for different proportions of generation with frequency control using total online

generation capacity Sb [ MW ]

The total online generation capacity is divided into two (2) which include the online

synchronous Ssb and online non-synchronous Sabgeneration capacity. Thus, total online

generation is given by:

Sb =Ssb +Sab

Where Ssb =αb SbandSab= ( 1−αb ) Sb, given that α bis the specified proportion of the total

online generation capacity which is synchronous.

Ssb is divided into the proportion of online synchronous generation capacity with primary

governing control Sspb=α spb Ssb and the balance of online synchronous generation capacity is

ungoverned S¿=1−αspb, therefore:. Ssb =Sspb+ S¿. In this assignment the system is assumed to

be ungoverned.

The initial power output from each of the generation sources is specified where the initial

system load is determined. The initial power output from the online synchronous generation with

primary speed control is specified as a fraction βsb of the specified online capacity Sspb. The initial

power output as pu (per unit) is given as:

Pms p0

=βsp ( Sspb

Sb )=βsp ( αspb Ssb

Sb )=β sp ( α spb αb ) ∈ puof Sb

The other types of generation as pu are given as:

Pms u0

=βsu ( 1−αspb ) αbPma u0

=βau (1−αb )

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Where the initial power output from the synchronous generation sources is Pm s0

=Pms u0

+ Pmau0

and from the asynchronous generation sources isPm a0

=Pmau0 , thus, the total output generation

sources are Pm0

=Pm s0

+ Pm a0. Therefore, to define the initial steady-state operating point of the

system it is required to specify βsp , βau∧β su

The inertia constant of online synchronous generation limits the rate of change of

frequency, and it is converted to pu as: H=H s ( Ssb

Sb )=αb Hs

The system load is linearly dependent on the system-frequency perturbation as:

Pl ( f ) =Pl0

( 1+D ∆ f )

Where Pl0the initial steady-state value of the load f =f 0 ( 1+∆ f ) is the system frequency, ∆ f is

per-unit system-frequency perturbation and f 0=50 Hzis the nominal frequency of the system

Answers to given questions

Part a) Equation of motion

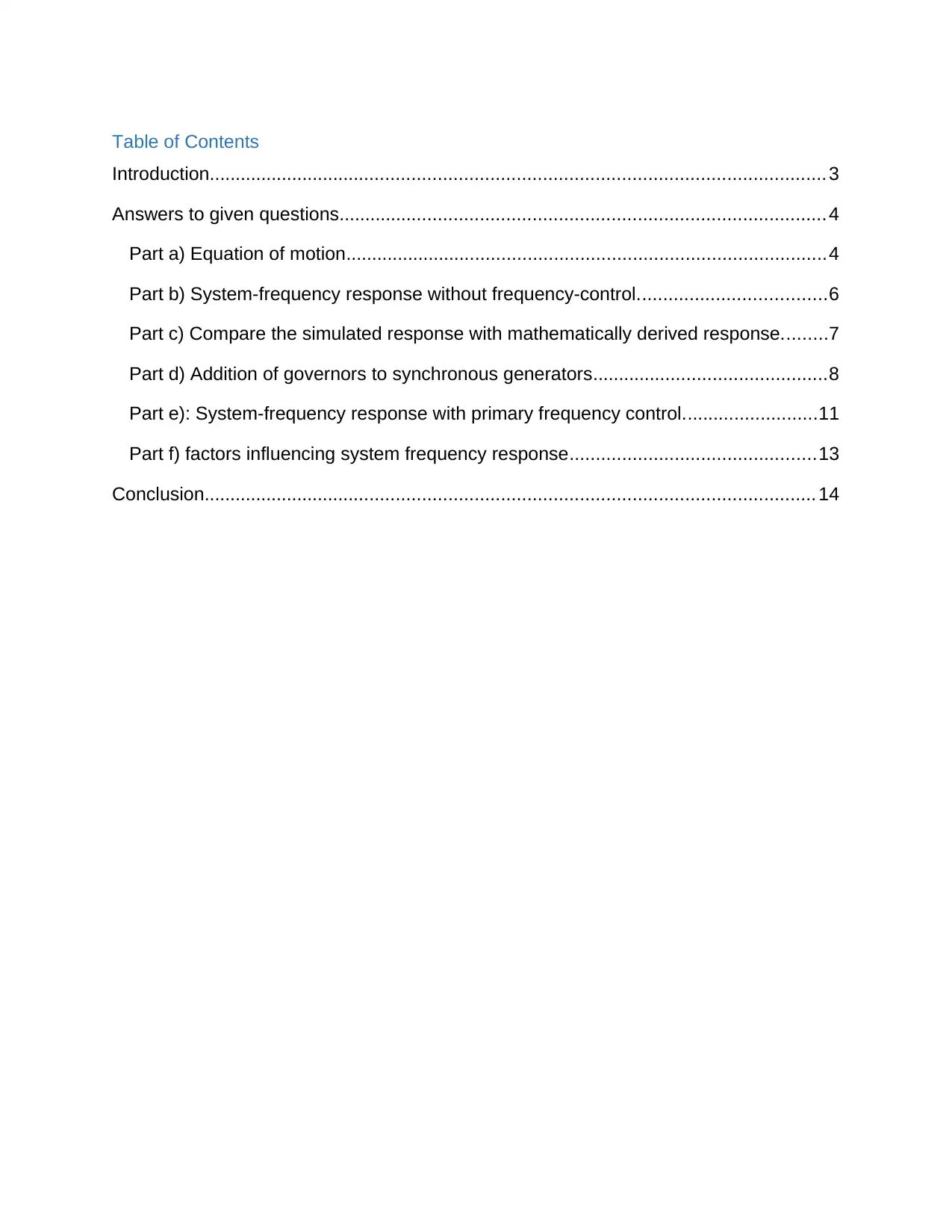

Given the equivalent generator for system load / frequency analysis in figure 1 (a) below:

Figure 1 (a): equivalent generator for system load / frequency analysis

=Pms u0

+ Pmau0

and from the asynchronous generation sources isPm a0

=Pmau0 , thus, the total output generation

sources are Pm0

=Pm s0

+ Pm a0. Therefore, to define the initial steady-state operating point of the

system it is required to specify βsp , βau∧β su

The inertia constant of online synchronous generation limits the rate of change of

frequency, and it is converted to pu as: H=H s ( Ssb

Sb )=αb Hs

The system load is linearly dependent on the system-frequency perturbation as:

Pl ( f ) =Pl0

( 1+D ∆ f )

Where Pl0the initial steady-state value of the load f =f 0 ( 1+∆ f ) is the system frequency, ∆ f is

per-unit system-frequency perturbation and f 0=50 Hzis the nominal frequency of the system

Answers to given questions

Part a) Equation of motion

Given the equivalent generator for system load / frequency analysis in figure 1 (a) below:

Figure 1 (a): equivalent generator for system load / frequency analysis

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The derivation of general equations for the initial-values of the outputs on the integrator(s) in the

system in figure 1. From the figure we can deduct the following equations

∆ f = E ( s )

2 Hs (i)E ( s )=Pm−Pl (ii) Pe=( ( Plo+ ∆ Pl ) + ( D+1 ) )∆ f (iii)

Combining equation (ii) and (ii):

E ( s )=Pm−( ( Plo+ ∆ Pl ) + ( D+1 )) ∆ f (iv )

Eliminating E(s) from equation (i) using equation (iv) gives

∆ f =Pm−¿ ¿

Making ∆ f the subject of the formula:

∆ f = 1

2 Hs ( pm− ( Plo+ ∆ Pl )

D+1 ) ( vi )

Let Plo+∆ Pl

D+ 1 = pl

∆ f = 1

2 Hs ( pm− pl )(vii)

The mathematical modelling block diagram of load can be represented as in figure 1 (b) below

Figure 1 (b): The mathematical modelling block diagram

Figure 1 is implemented in Simulink block diagrams shown in figure 2 below. The model

parameters and initial conditions are represented as variables in the Simulink blocks rather than

by specific numerical values

Figure 2: Simulink representation

system in figure 1. From the figure we can deduct the following equations

∆ f = E ( s )

2 Hs (i)E ( s )=Pm−Pl (ii) Pe=( ( Plo+ ∆ Pl ) + ( D+1 ) )∆ f (iii)

Combining equation (ii) and (ii):

E ( s )=Pm−( ( Plo+ ∆ Pl ) + ( D+1 )) ∆ f (iv )

Eliminating E(s) from equation (i) using equation (iv) gives

∆ f =Pm−¿ ¿

Making ∆ f the subject of the formula:

∆ f = 1

2 Hs ( pm− ( Plo+ ∆ Pl )

D+1 ) ( vi )

Let Plo+∆ Pl

D+ 1 = pl

∆ f = 1

2 Hs ( pm− pl )(vii)

The mathematical modelling block diagram of load can be represented as in figure 1 (b) below

Figure 1 (b): The mathematical modelling block diagram

Figure 1 is implemented in Simulink block diagrams shown in figure 2 below. The model

parameters and initial conditions are represented as variables in the Simulink blocks rather than

by specific numerical values

Figure 2: Simulink representation

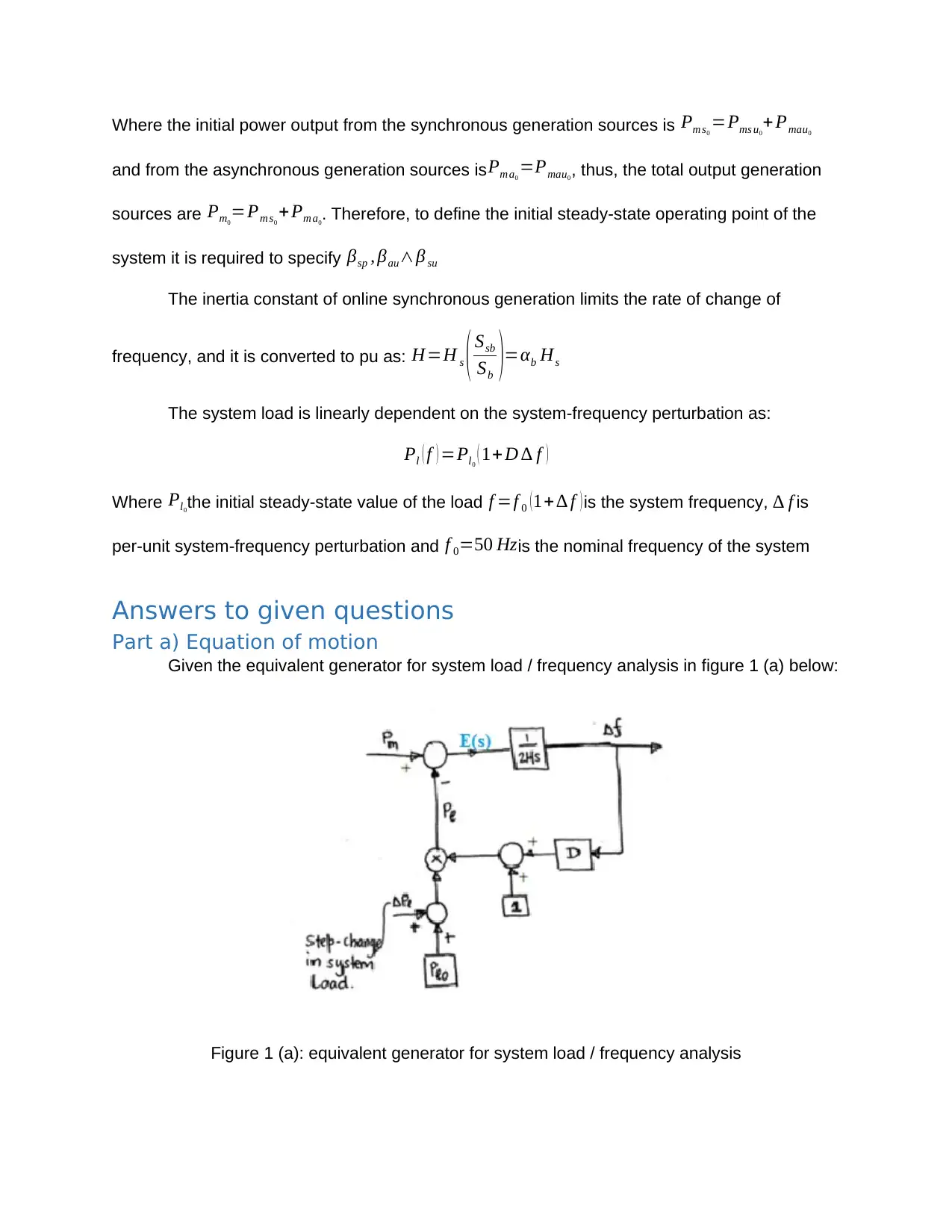

Part b) System-frequency response without frequency-control.

By use of the Simulink model constructed in part (a), the simulation is performed using

the following data in table 1 below:

Parameters Value Parameters Values

∆ pl 0.02 α spb 0.0

H 3.5 βsp 0.0

D 1.0 βsu 0.8

α b 1.0 βau 0.8

Table 1: Generator parameters

Simulation results for the above parameter for ∆ f

Figure 1 (d): Simulated result

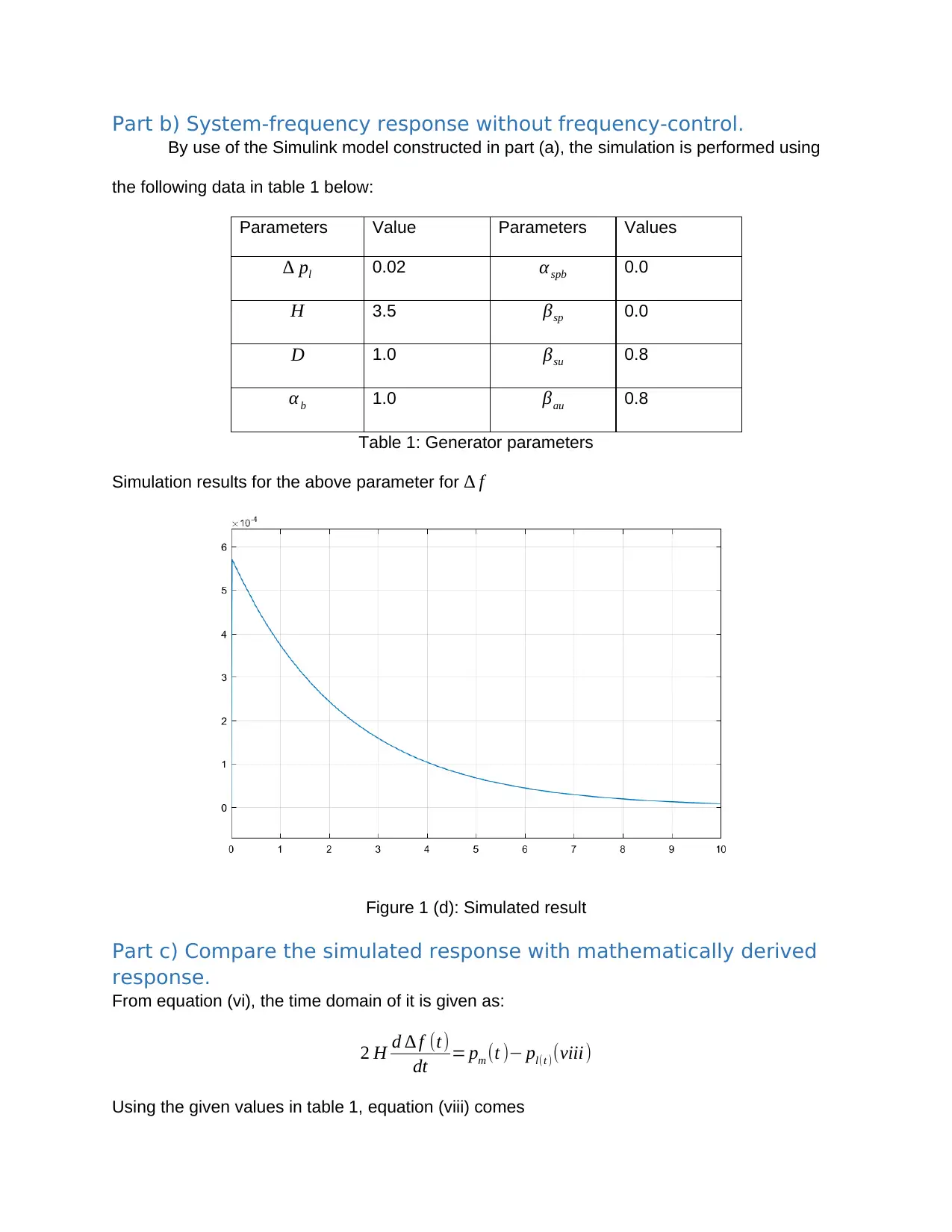

Part c) Compare the simulated response with mathematically derived

response.

From equation (vi), the time domain of it is given as:

2 H d ∆ f (t)

dt = pm (t )− pl(t )(viii )

Using the given values in table 1, equation (viii) comes

By use of the Simulink model constructed in part (a), the simulation is performed using

the following data in table 1 below:

Parameters Value Parameters Values

∆ pl 0.02 α spb 0.0

H 3.5 βsp 0.0

D 1.0 βsu 0.8

α b 1.0 βau 0.8

Table 1: Generator parameters

Simulation results for the above parameter for ∆ f

Figure 1 (d): Simulated result

Part c) Compare the simulated response with mathematically derived

response.

From equation (vi), the time domain of it is given as:

2 H d ∆ f (t)

dt = pm (t )− pl(t )(viii )

Using the given values in table 1, equation (viii) comes

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7 d ∆ f

dt =2 pm ( t ) −pl ( t ) (ix)

On simulating the above using MATLAB gives the figure

Figure 1 (e): Simulation of equation (ix).

Figures 1 (d) and 1 (e) are same,

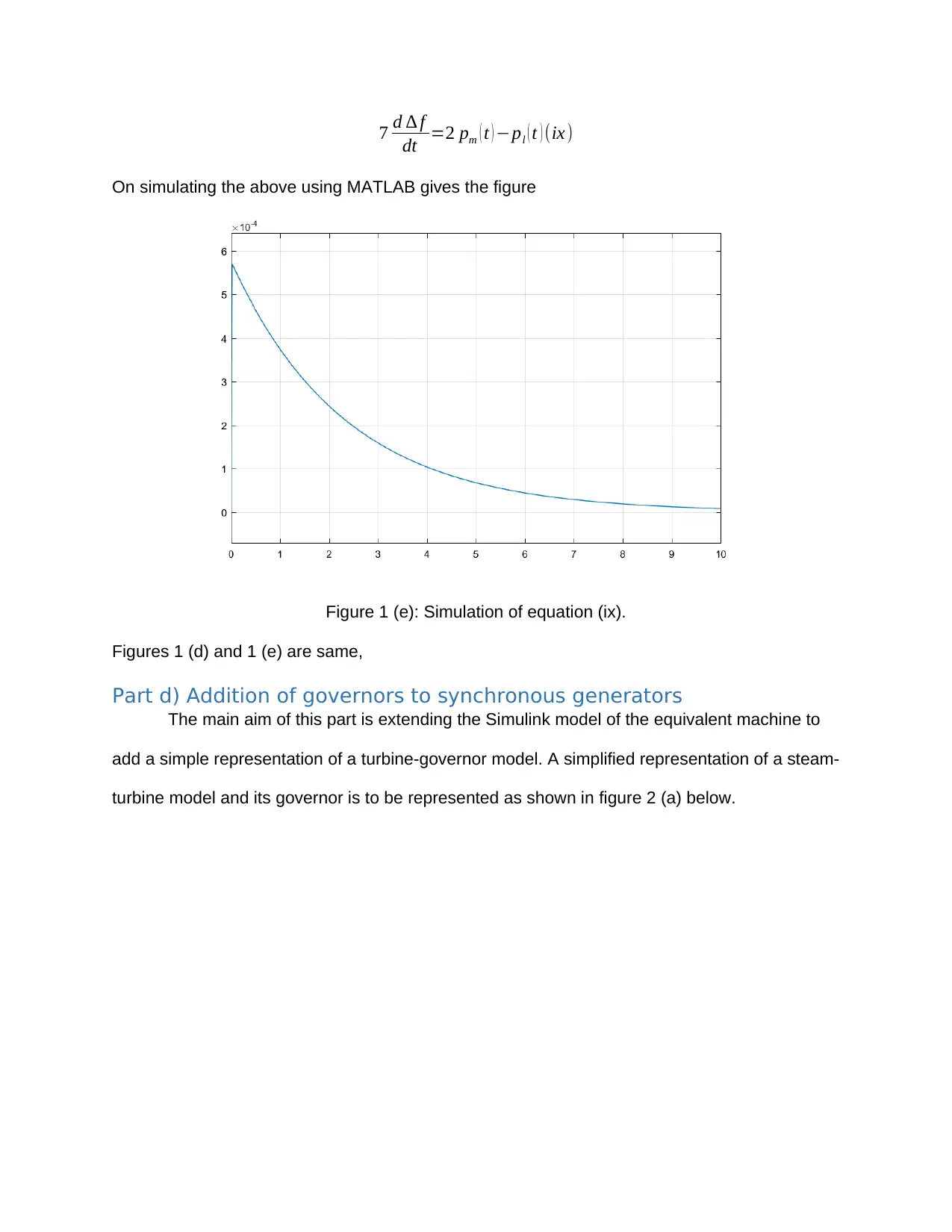

Part d) Addition of governors to synchronous generators

The main aim of this part is extending the Simulink model of the equivalent machine to

add a simple representation of a turbine-governor model. A simplified representation of a steam-

turbine model and its governor is to be represented as shown in figure 2 (a) below.

dt =2 pm ( t ) −pl ( t ) (ix)

On simulating the above using MATLAB gives the figure

Figure 1 (e): Simulation of equation (ix).

Figures 1 (d) and 1 (e) are same,

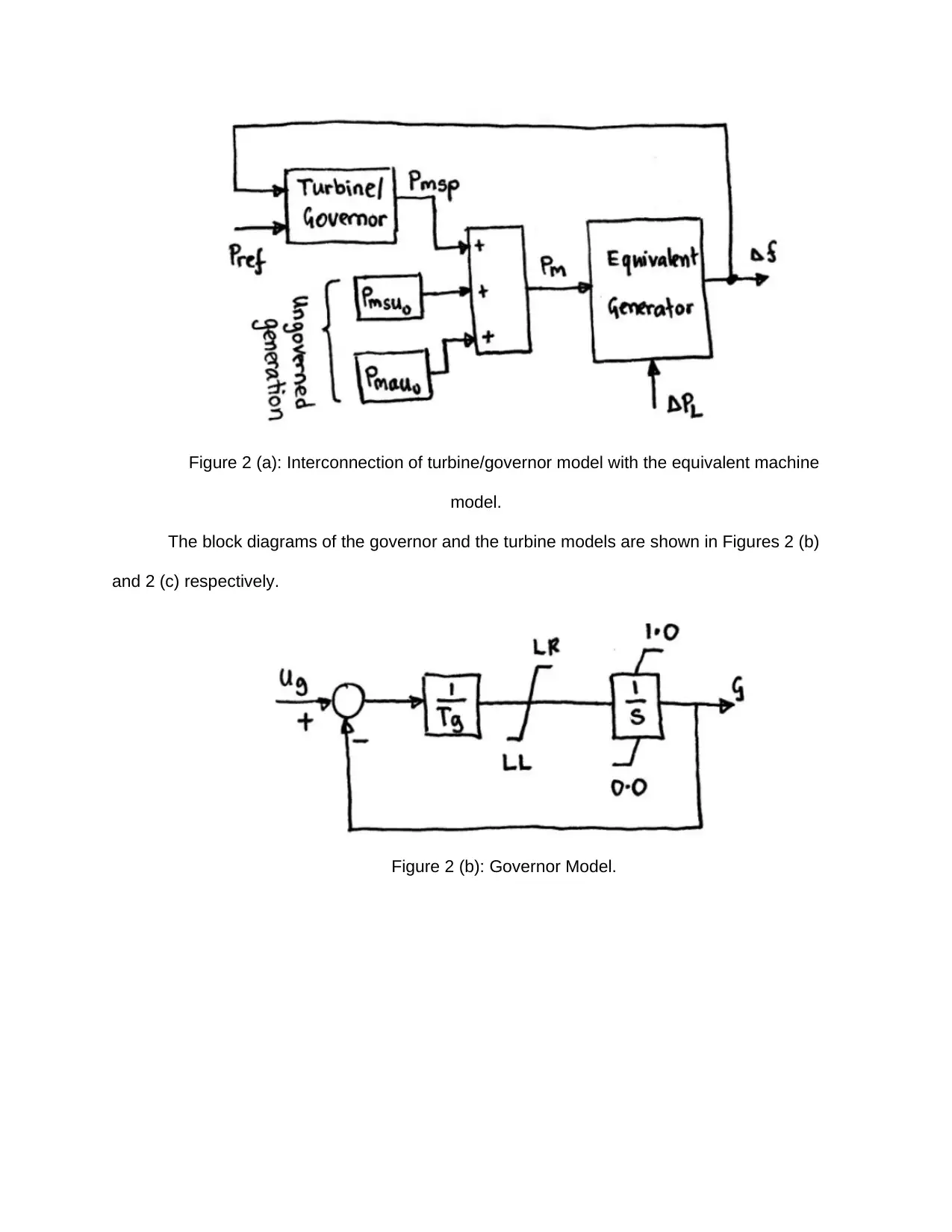

Part d) Addition of governors to synchronous generators

The main aim of this part is extending the Simulink model of the equivalent machine to

add a simple representation of a turbine-governor model. A simplified representation of a steam-

turbine model and its governor is to be represented as shown in figure 2 (a) below.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Figure 2 (a): Interconnection of turbine/governor model with the equivalent machine

model.

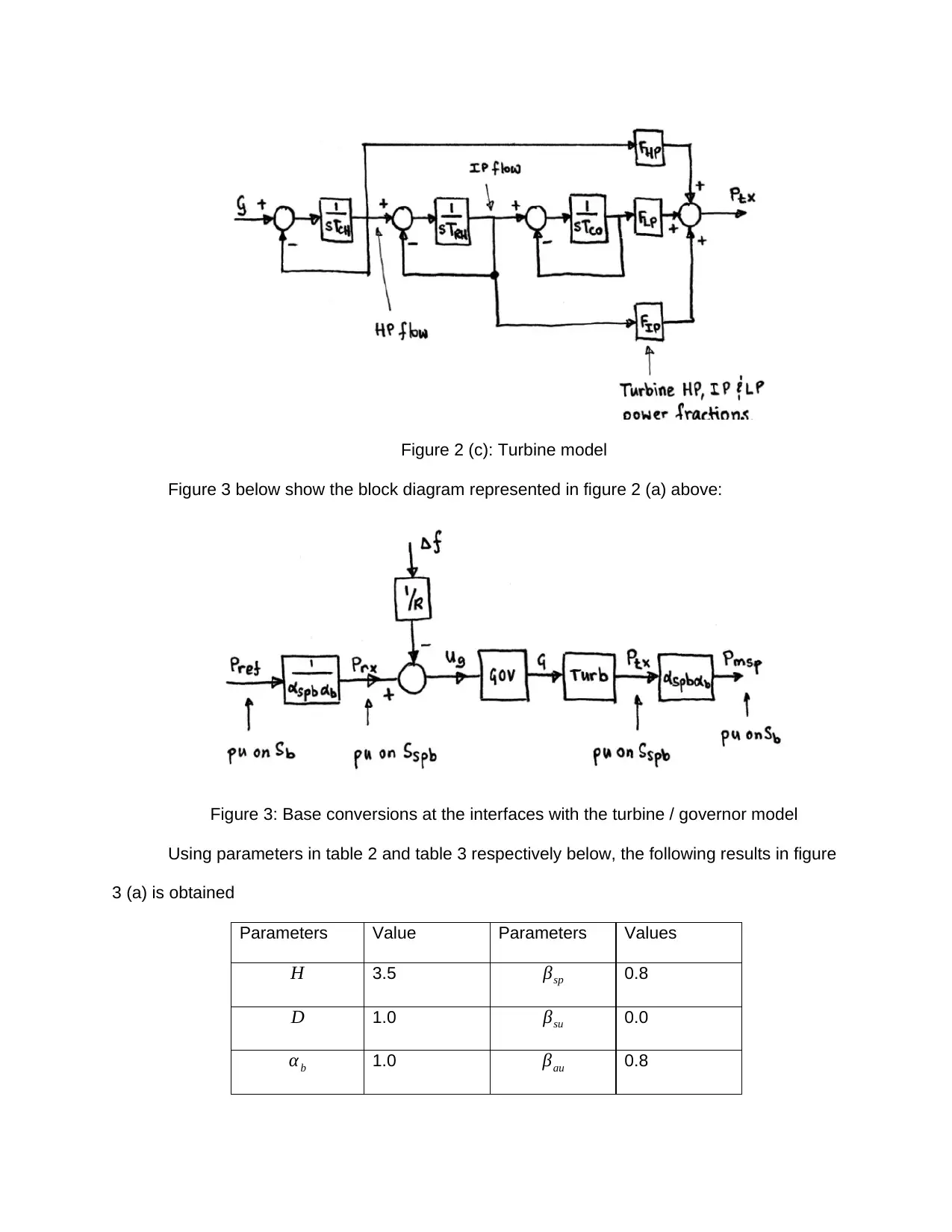

The block diagrams of the governor and the turbine models are shown in Figures 2 (b)

and 2 (c) respectively.

Figure 2 (b): Governor Model.

model.

The block diagrams of the governor and the turbine models are shown in Figures 2 (b)

and 2 (c) respectively.

Figure 2 (b): Governor Model.

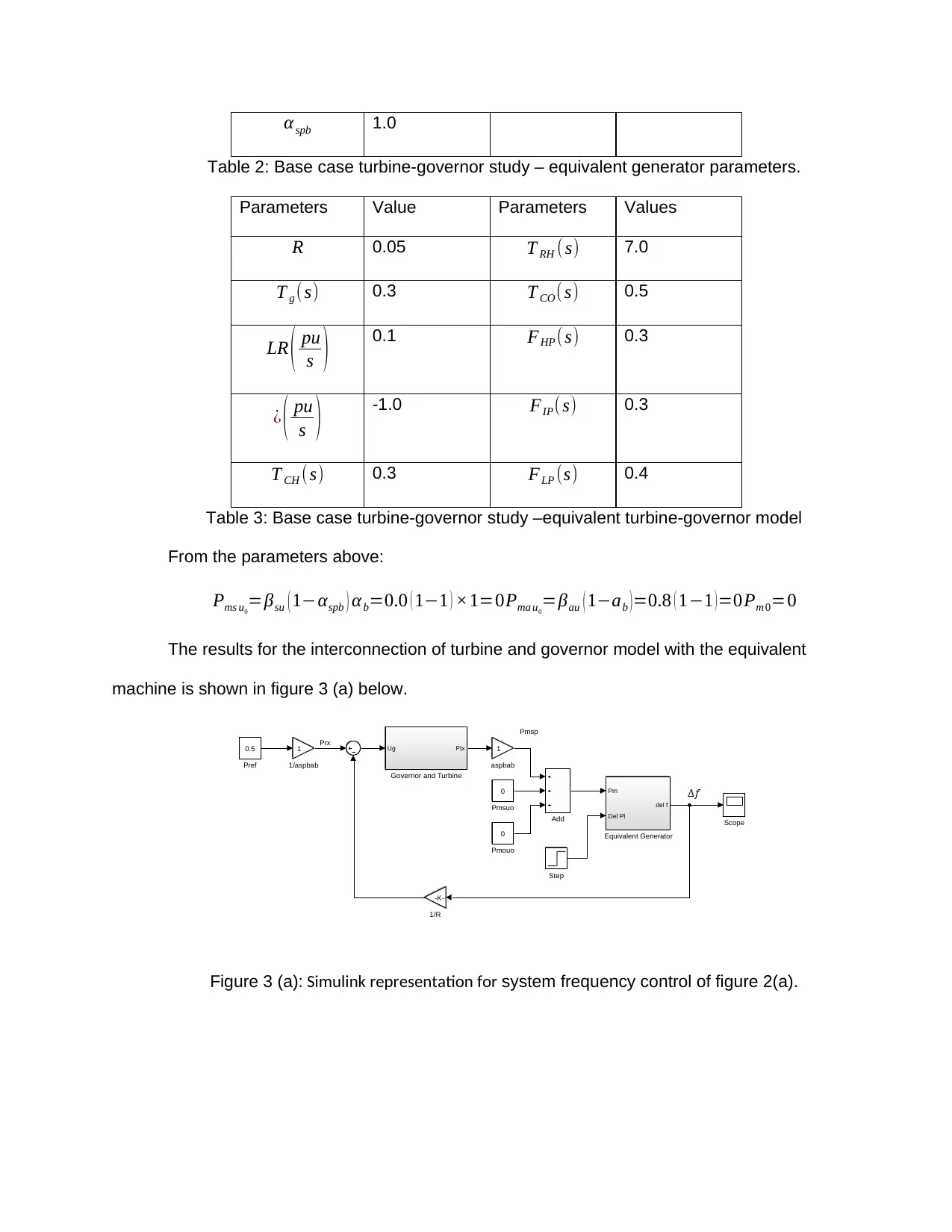

Figure 2 (c): Turbine model

Figure 3 below show the block diagram represented in figure 2 (a) above:

Figure 3: Base conversions at the interfaces with the turbine / governor model

Using parameters in table 2 and table 3 respectively below, the following results in figure

3 (a) is obtained

Parameters Value Parameters Values

H 3.5 βsp 0.8

D 1.0 βsu 0.0

α b 1.0 βau 0.8

Figure 3 below show the block diagram represented in figure 2 (a) above:

Figure 3: Base conversions at the interfaces with the turbine / governor model

Using parameters in table 2 and table 3 respectively below, the following results in figure

3 (a) is obtained

Parameters Value Parameters Values

H 3.5 βsp 0.8

D 1.0 βsu 0.0

α b 1.0 βau 0.8

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

α spb 1.0

Table 2: Base case turbine-governor study – equivalent generator parameters.

Parameters Value Parameters Values

R 0.05 T RH ( s) 7.0

T g ( s) 0.3 T CO( s) 0.5

LR ( pu

s ) 0.1 FHP (s) 0.3

¿ ( pu

s ) -1.0 FIP( s) 0.3

T CH (s) 0.3 FLP (s) 0.4

Table 3: Base case turbine-governor study –equivalent turbine-governor model

From the parameters above:

Pms u0

=βsu ( 1−αspb ) α b=0.0 ( 1−1 ) ×1=0Pma u0

=βau ( 1−ab )=0.8 ( 1−1 )=0 Pm 0=0

The results for the interconnection of turbine and governor model with the equivalent

machine is shown in figure 3 (a) below.

Prx

Pmsp

Pm

Del Pl

del f

Equivalent Generator

Ug Ptx

Governor and Turbine

1

1/aspbab

1

aspbab

0.5

Pref

Add

0

Pmouo

0

Pmsuo

Step

-K-

1/R

Scope

Figure 3 (a): Simulink representation for system frequency control of figure 2(a).

Table 2: Base case turbine-governor study – equivalent generator parameters.

Parameters Value Parameters Values

R 0.05 T RH ( s) 7.0

T g ( s) 0.3 T CO( s) 0.5

LR ( pu

s ) 0.1 FHP (s) 0.3

¿ ( pu

s ) -1.0 FIP( s) 0.3

T CH (s) 0.3 FLP (s) 0.4

Table 3: Base case turbine-governor study –equivalent turbine-governor model

From the parameters above:

Pms u0

=βsu ( 1−αspb ) α b=0.0 ( 1−1 ) ×1=0Pma u0

=βau ( 1−ab )=0.8 ( 1−1 )=0 Pm 0=0

The results for the interconnection of turbine and governor model with the equivalent

machine is shown in figure 3 (a) below.

Prx

Pmsp

Pm

Del Pl

del f

Equivalent Generator

Ug Ptx

Governor and Turbine

1

1/aspbab

1

aspbab

0.5

Pref

Add

0

Pmouo

0

Pmsuo

Step

-K-

1/R

Scope

Figure 3 (a): Simulink representation for system frequency control of figure 2(a).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Part e): System-frequency response with primary frequency control.

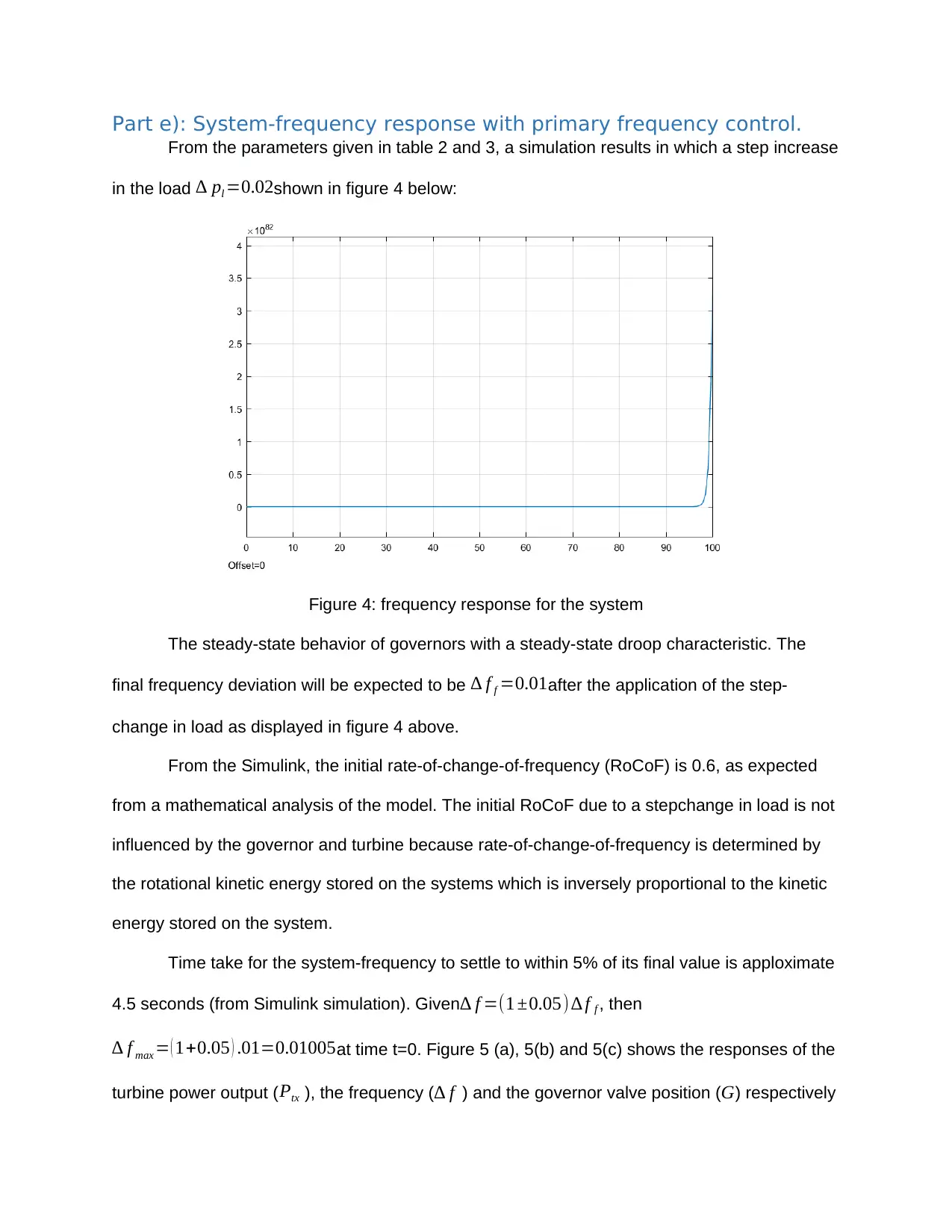

From the parameters given in table 2 and 3, a simulation results in which a step increase

in the load ∆ pl =0.02shown in figure 4 below:

Figure 4: frequency response for the system

The steady-state behavior of governors with a steady-state droop characteristic. The

final frequency deviation will be expected to be ∆ f f =0.01after the application of the step-

change in load as displayed in figure 4 above.

From the Simulink, the initial rate-of-change-of-frequency (RoCoF) is 0.6, as expected

from a mathematical analysis of the model. The initial RoCoF due to a stepchange in load is not

influenced by the governor and turbine because rate-of-change-of-frequency is determined by

the rotational kinetic energy stored on the systems which is inversely proportional to the kinetic

energy stored on the system.

Time take for the system-frequency to settle to within 5% of its final value is apploximate

4.5 seconds (from Simulink simulation). Given∆ f =(1 ±0.05)∆ f f , then

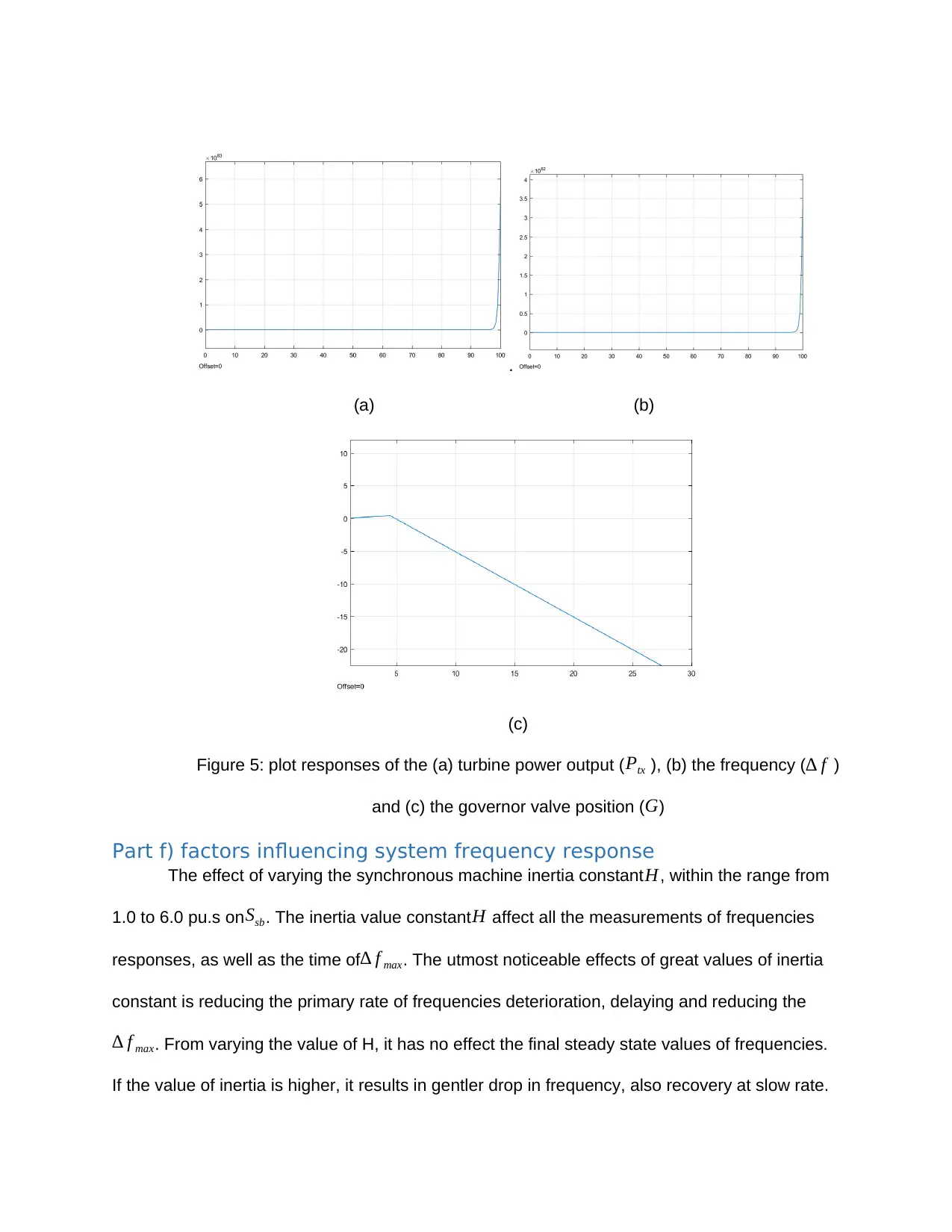

∆ f max = ( 1+0.05 ) .01=0.01005at time t=0. Figure 5 (a), 5(b) and 5(c) shows the responses of the

turbine power output ( Ptx ), the frequency ( ∆ f ) and the governor valve position (G) respectively

From the parameters given in table 2 and 3, a simulation results in which a step increase

in the load ∆ pl =0.02shown in figure 4 below:

Figure 4: frequency response for the system

The steady-state behavior of governors with a steady-state droop characteristic. The

final frequency deviation will be expected to be ∆ f f =0.01after the application of the step-

change in load as displayed in figure 4 above.

From the Simulink, the initial rate-of-change-of-frequency (RoCoF) is 0.6, as expected

from a mathematical analysis of the model. The initial RoCoF due to a stepchange in load is not

influenced by the governor and turbine because rate-of-change-of-frequency is determined by

the rotational kinetic energy stored on the systems which is inversely proportional to the kinetic

energy stored on the system.

Time take for the system-frequency to settle to within 5% of its final value is apploximate

4.5 seconds (from Simulink simulation). Given∆ f =(1 ±0.05)∆ f f , then

∆ f max = ( 1+0.05 ) .01=0.01005at time t=0. Figure 5 (a), 5(b) and 5(c) shows the responses of the

turbine power output ( Ptx ), the frequency ( ∆ f ) and the governor valve position (G) respectively

.

(a) (b)

(c)

Figure 5: plot responses of the (a) turbine power output (Ptx ), (b) the frequency (∆ f )

and (c) the governor valve position (G)

Part f) factors influencing system frequency response

The effect of varying the synchronous machine inertia constant H , within the range from

1.0 to 6.0 pu.s on Ssb. The inertia value constant H affect all the measurements of frequencies

responses, as well as the time of∆ f max. The utmost noticeable effects of great values of inertia

constant is reducing the primary rate of frequencies deterioration, delaying and reducing the

∆ f max. From varying the value of H, it has no effect the final steady state values of frequencies.

If the value of inertia is higher, it results in gentler drop in frequency, also recovery at slow rate.

(a) (b)

(c)

Figure 5: plot responses of the (a) turbine power output (Ptx ), (b) the frequency (∆ f )

and (c) the governor valve position (G)

Part f) factors influencing system frequency response

The effect of varying the synchronous machine inertia constant H , within the range from

1.0 to 6.0 pu.s on Ssb. The inertia value constant H affect all the measurements of frequencies

responses, as well as the time of∆ f max. The utmost noticeable effects of great values of inertia

constant is reducing the primary rate of frequencies deterioration, delaying and reducing the

∆ f max. From varying the value of H, it has no effect the final steady state values of frequencies.

If the value of inertia is higher, it results in gentler drop in frequency, also recovery at slow rate.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.