Exploring CAM Use Among Adult Sickle Cell Patients for Pain Relief

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/23

|6

|5474

|84

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among adult sickle cell disease (SCD) patients attending a tertiary institution's sickle cell clinic. The cross-sectional survey of 227 patients revealed that a significant majority (91.6%) used CAM in the last six months to manage pain, with prayer being the most common method. The study found that females and individuals with higher education levels were more likely to use CAM. While pharmacologic medications remain a primary component of pain management, an increasing number of patients are turning to CAM for pain relief. The research highlights the need for further investigation into the benefits and accessibility of CAM therapies for adult SCD patients. Desklib provides access to this and other solved assignments to aid students in their studies.

PRIMARY CARE & HEALTH SERVICES SECTION

Original Research Article

Pain Control in Sickle Cell Disease

Patients: Use of Complementary and

Alternative Medicine

Wendy E. Thompson, DrPH, MSW,* and Ike Eriator,

MD, MPH†

*School of Social Work, Andrews University, Berrien

Springs, Michigan;

†School of Medicine, University of Mississippi,

Jackson, Mississippi, USA

Reprint requests to: Wendy E. Thompson, DrPH,

MSW, School of Social Work, Andrews University,

Berrien Springs, MI 49103, USA. Tel: 601-594-0058;

Fax: 269-471-3686; E-mail: thompsow@andrews.edu.

Disclosure: None of the authors has any conflict of

interest or anything to disclose.

Abstract

Objective. To examine the factors associated with

the use of complementary and alternative medicine

(CAM) as reported by patients attending an adult

sickle cell clinic at a tertiary institution.

Design. Cross-sectional survey.

Setting. This study was conducted in a university

tertiary care adult sickle cell clinic.

Subjects. Adult sickle cell patients.

Method. Following Institutional Review Board

approval, a questionnaire was administered to

patients in a sickle cell clinic to examine their use of

CAM for managing pain at home and while admitted

to the hospital.

Results. Of the 227 respondents who completed the

questionnaire, 92% experienced pain lasting from 6

months to more than 2 years. Two hundred and eight

(91.6%) indicated that they have used CAM within

the last 6 months to control pain. The frequency

of CAMs use was higher among females, singles,

those with more education, and higher household

income.

Conclusions. This study shows that a substantial

majority of sickle cell patients live with pain on a

regular basis and that there is substantial CAM use

in the adult Sickle cell disease population. Being

female and having a high school or higher education

were significantly correlated with the use of CAM in

sickle cell patients. A variety of CAM therapies are

used, with the most common being prayer.

Key Words. Complementary Alternative Methods;

Sickle Cell Disease; Coping with Pain; Chronic Pain

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD)remains a significantpublic

health problem in the United States [1]. It is estimated that

approximately 2 million Americans are genetic carriers of

the sickle celltrait [2], and 100,000 people are estimated

to be living with a history of SCD in the United States [3].

The incidence ofSCD is particularly high among African

Americans [4]. Despite the availability of tests to screen for

compatibility ofgenotype [1,5]and programs to increase

individuals’awareness ofthe disease [6],the prevalence

rate ofSCD has continued to rise in the past decade in

some parts of the United States [7]. The prevalence of this

disease is greaterthan that of any other condition

detected by newborn blood screening [2]. Research has

indicated that SCD is linked with severalacute pulmonary

complications including asthma,thromboembolism,and

acute chestsyndrome [8,9].Otherhealth complications

thatoccur as a resultof the disease include blindness,

skin ulcers,gallstones,priapism,bacterialsepticemia,

splenic sequestration, stroke, and chronic organ damage

[10–13]. These complications can be life-threatening and

can affect the whole body [6].

One of the hallmarks of this disease is intermittent, unpre-

dictable pain episodes ofvarying intensities [14].Pain in

SCD presents distinctive challenges for patients, families,

and health-care professionals [15–17].It is the most fre-

quent problem experienced by people with SCD and has

profound effects upon comfortand function in work,

school,play,and socialrelationships [18].A review by

Ballas, Gupta and Graves (2012) examined the frequency

of painfulepisodes experienced by sickle cellpatients and

found that acute painfulepisodes were the most common

bs_bs_banner

Pain Medicine 2014; 15: 241–246

Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

241

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

Original Research Article

Pain Control in Sickle Cell Disease

Patients: Use of Complementary and

Alternative Medicine

Wendy E. Thompson, DrPH, MSW,* and Ike Eriator,

MD, MPH†

*School of Social Work, Andrews University, Berrien

Springs, Michigan;

†School of Medicine, University of Mississippi,

Jackson, Mississippi, USA

Reprint requests to: Wendy E. Thompson, DrPH,

MSW, School of Social Work, Andrews University,

Berrien Springs, MI 49103, USA. Tel: 601-594-0058;

Fax: 269-471-3686; E-mail: thompsow@andrews.edu.

Disclosure: None of the authors has any conflict of

interest or anything to disclose.

Abstract

Objective. To examine the factors associated with

the use of complementary and alternative medicine

(CAM) as reported by patients attending an adult

sickle cell clinic at a tertiary institution.

Design. Cross-sectional survey.

Setting. This study was conducted in a university

tertiary care adult sickle cell clinic.

Subjects. Adult sickle cell patients.

Method. Following Institutional Review Board

approval, a questionnaire was administered to

patients in a sickle cell clinic to examine their use of

CAM for managing pain at home and while admitted

to the hospital.

Results. Of the 227 respondents who completed the

questionnaire, 92% experienced pain lasting from 6

months to more than 2 years. Two hundred and eight

(91.6%) indicated that they have used CAM within

the last 6 months to control pain. The frequency

of CAMs use was higher among females, singles,

those with more education, and higher household

income.

Conclusions. This study shows that a substantial

majority of sickle cell patients live with pain on a

regular basis and that there is substantial CAM use

in the adult Sickle cell disease population. Being

female and having a high school or higher education

were significantly correlated with the use of CAM in

sickle cell patients. A variety of CAM therapies are

used, with the most common being prayer.

Key Words. Complementary Alternative Methods;

Sickle Cell Disease; Coping with Pain; Chronic Pain

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD)remains a significantpublic

health problem in the United States [1]. It is estimated that

approximately 2 million Americans are genetic carriers of

the sickle celltrait [2], and 100,000 people are estimated

to be living with a history of SCD in the United States [3].

The incidence ofSCD is particularly high among African

Americans [4]. Despite the availability of tests to screen for

compatibility ofgenotype [1,5]and programs to increase

individuals’awareness ofthe disease [6],the prevalence

rate ofSCD has continued to rise in the past decade in

some parts of the United States [7]. The prevalence of this

disease is greaterthan that of any other condition

detected by newborn blood screening [2]. Research has

indicated that SCD is linked with severalacute pulmonary

complications including asthma,thromboembolism,and

acute chestsyndrome [8,9].Otherhealth complications

thatoccur as a resultof the disease include blindness,

skin ulcers,gallstones,priapism,bacterialsepticemia,

splenic sequestration, stroke, and chronic organ damage

[10–13]. These complications can be life-threatening and

can affect the whole body [6].

One of the hallmarks of this disease is intermittent, unpre-

dictable pain episodes ofvarying intensities [14].Pain in

SCD presents distinctive challenges for patients, families,

and health-care professionals [15–17].It is the most fre-

quent problem experienced by people with SCD and has

profound effects upon comfortand function in work,

school,play,and socialrelationships [18].A review by

Ballas, Gupta and Graves (2012) examined the frequency

of painfulepisodes experienced by sickle cellpatients and

found that acute painfulepisodes were the most common

bs_bs_banner

Pain Medicine 2014; 15: 241–246

Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

241

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

cause ofhospitalizations.The study also indicated that

50% of hospitaladmissions foracute painfulepisodes

were readmissions within 1 month afterdischarge.This

was associated with pain, suffering, fear, anxiety, depres-

sion, the utilization of relatively high doses of opioids, and

alienationfrom the realitiesof daily living [19]. The

researchers suggested that improvement was needed in

the managementof pain during hospitalization and at

home afterdischarge.Brousseau et al.(2010),using a

retrospective cohort, examined 21,112 sickle cell-related

emergency room treatmentor in-patienthospitalization.

They noted a mean of 2.59 (95% confidence interval[CI])

encounter per patient per year. Utilization was highest for

those in the age group 18–30 years and those with public

insurance.The 30-day rehospitalization rate was 33.4%,

with those in the 18–30-year age group averaging 41.1%

[20]. Pharmacologic medications are a significant compo-

nent ofacute and chronic pain management in the adult

sickle cellpatient.However,recently,more and more

patients have been turning to complementary and alter-

native medicines (CAM)to help manage their painfulepi-

sodes [21–23].

CAM, defined as a group ofdiverse medicaland health

care systems, practices, and products that are not pres-

ently considered part ofconventionalmedicine, is on the

rise universally [24].For the purpose ofthis research,

prayer was defined using the National Center for

Complementary and Alternative Medicine’s definition as

“an active processof appealing to a higherspiritual

power, especially for health reasons: it includes individual

or group prayer on behalfof oneselfor others.” Spiritual

healing is the healing that is transmitted by the spirit, soul

of divine force. Acupuncture is a technique in which prac-

titionersstimulate specific pointson the body—most

often by inserting thin needles through the skin. Massage

therapyincludesmany differenttechniquesin which

practitioners manually manipulate the softtissues ofthe

body.Most meditation techniques involve ways in which

a person learns to focus attention.Relaxation tech-

niques, such as breathing exercises, guided imagery, and

progressive muscle relaxation,are designed to produce

the body’s naturalrelaxation response.

SCD patients seeking to use CAM face a numberof

challenges such as lack of access to these methods and

lack of third party or insurance to cover them as they utilize

CAM [25,26].Sibinga et al.(2006)examined pediatric

patients with SCD and use ofcomplementary and alter-

native therapies and showed that the use ofCAM thera-

pies was common among children with SCD.Prayer,

relaxation techniques, and spiritualhealing were the most

commonly reported CAM therapies [27]. However, there is

a scarcity ofresearch studies on CAM use among adult

sickle cellpatients and the factors thatare associated

its use.

The purpose of our study is to examine the factors asso-

ciated with the use of CAM as reported by patients attend-

ing an adult sickle cellclinic at a tertiary institution in the

United States.

Methods

This is a cross-sectionalstudy carried out using a survey

administered during the months of July through Septem-

ber 2010 at an adultsickle cellclinic.The researcher

invited alladults who were obtaining pain management

treatment for SCD at the clinic (in that 3-month period) to

voluntarily complete a three-page written questionnaire

about CAM use and its benefits. The study protocolwas

approved by InstitutionalReview Boards at Jackson

State University and the University ofMedicalCenter,

Jackson, Mississippi.Written,informed consentforms

were obtained from allparticipants.

Subjects

There were 450 sickle cellpatient registered in the clinic.

The study sample consisted ofa total of 227 patients

invited to participate in the study. Selection criteria for this

study included participants who had been diagnosed with

SCD, were African American, were between ages 18 and

65 years, and had been experiencing pain within the last 6

months.All of the invited patients agreed to participate,

and completed the questionnaire while in the waiting

room. Not allparticipants answered allof the questions.

Survey

Participants completed a three-page survey while they

were waiting to be seen by the hematologist.The ques-

tionnairewas tested for reliability.Cronbach’salpha

coefficientwas greaterthan .80.The questionnaire was

pilot-tested with individuals of similar demographic back-

ground to the study population and was revised based on

theircomments.It was assessed forcontentvalidity by

experts in the field.The survey was written atan eight-

grade reading level and took approximately20–25

minutes to complete. Respondents were informed that the

principalinvestigator and a nurse were available onsite if

they needed assistance with completing the question-

naire. The completed questionnaires were handed back to

the principalinvestigator.The questionnaire consisted of

nine structured items. Participants were asked about their

pain experienced within the past 6 months (when treated

at home and when treated in the hospital),the types of

CAM used and the benefits, and about their demographic

characteristics. There was also a set ofyes–no items on

the types of CAM used and its effectiveness in controlling

painfulepisodes in the last 6 months. A totalof 15 com-

monly used CAMs were provided on the list. A copy of the

questionnaire is attached (Appendix S1).

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using StatisticalPackage for

SocialSciences version 19.0 [28].Descriptive statistics

was used to determine the frequency ofCAM use. The

influence ofvariousfactors, such as gender,marital

status, age, education, household annualincome, type of

medicalinsurance, and type of SCD, on the use of CAM

were analyzed with binary logistic regression. Results are

242

Thompson and Eriator

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

50% of hospitaladmissions foracute painfulepisodes

were readmissions within 1 month afterdischarge.This

was associated with pain, suffering, fear, anxiety, depres-

sion, the utilization of relatively high doses of opioids, and

alienationfrom the realitiesof daily living [19]. The

researchers suggested that improvement was needed in

the managementof pain during hospitalization and at

home afterdischarge.Brousseau et al.(2010),using a

retrospective cohort, examined 21,112 sickle cell-related

emergency room treatmentor in-patienthospitalization.

They noted a mean of 2.59 (95% confidence interval[CI])

encounter per patient per year. Utilization was highest for

those in the age group 18–30 years and those with public

insurance.The 30-day rehospitalization rate was 33.4%,

with those in the 18–30-year age group averaging 41.1%

[20]. Pharmacologic medications are a significant compo-

nent ofacute and chronic pain management in the adult

sickle cellpatient.However,recently,more and more

patients have been turning to complementary and alter-

native medicines (CAM)to help manage their painfulepi-

sodes [21–23].

CAM, defined as a group ofdiverse medicaland health

care systems, practices, and products that are not pres-

ently considered part ofconventionalmedicine, is on the

rise universally [24].For the purpose ofthis research,

prayer was defined using the National Center for

Complementary and Alternative Medicine’s definition as

“an active processof appealing to a higherspiritual

power, especially for health reasons: it includes individual

or group prayer on behalfof oneselfor others.” Spiritual

healing is the healing that is transmitted by the spirit, soul

of divine force. Acupuncture is a technique in which prac-

titionersstimulate specific pointson the body—most

often by inserting thin needles through the skin. Massage

therapyincludesmany differenttechniquesin which

practitioners manually manipulate the softtissues ofthe

body.Most meditation techniques involve ways in which

a person learns to focus attention.Relaxation tech-

niques, such as breathing exercises, guided imagery, and

progressive muscle relaxation,are designed to produce

the body’s naturalrelaxation response.

SCD patients seeking to use CAM face a numberof

challenges such as lack of access to these methods and

lack of third party or insurance to cover them as they utilize

CAM [25,26].Sibinga et al.(2006)examined pediatric

patients with SCD and use ofcomplementary and alter-

native therapies and showed that the use ofCAM thera-

pies was common among children with SCD.Prayer,

relaxation techniques, and spiritualhealing were the most

commonly reported CAM therapies [27]. However, there is

a scarcity ofresearch studies on CAM use among adult

sickle cellpatients and the factors thatare associated

its use.

The purpose of our study is to examine the factors asso-

ciated with the use of CAM as reported by patients attend-

ing an adult sickle cellclinic at a tertiary institution in the

United States.

Methods

This is a cross-sectionalstudy carried out using a survey

administered during the months of July through Septem-

ber 2010 at an adultsickle cellclinic.The researcher

invited alladults who were obtaining pain management

treatment for SCD at the clinic (in that 3-month period) to

voluntarily complete a three-page written questionnaire

about CAM use and its benefits. The study protocolwas

approved by InstitutionalReview Boards at Jackson

State University and the University ofMedicalCenter,

Jackson, Mississippi.Written,informed consentforms

were obtained from allparticipants.

Subjects

There were 450 sickle cellpatient registered in the clinic.

The study sample consisted ofa total of 227 patients

invited to participate in the study. Selection criteria for this

study included participants who had been diagnosed with

SCD, were African American, were between ages 18 and

65 years, and had been experiencing pain within the last 6

months.All of the invited patients agreed to participate,

and completed the questionnaire while in the waiting

room. Not allparticipants answered allof the questions.

Survey

Participants completed a three-page survey while they

were waiting to be seen by the hematologist.The ques-

tionnairewas tested for reliability.Cronbach’salpha

coefficientwas greaterthan .80.The questionnaire was

pilot-tested with individuals of similar demographic back-

ground to the study population and was revised based on

theircomments.It was assessed forcontentvalidity by

experts in the field.The survey was written atan eight-

grade reading level and took approximately20–25

minutes to complete. Respondents were informed that the

principalinvestigator and a nurse were available onsite if

they needed assistance with completing the question-

naire. The completed questionnaires were handed back to

the principalinvestigator.The questionnaire consisted of

nine structured items. Participants were asked about their

pain experienced within the past 6 months (when treated

at home and when treated in the hospital),the types of

CAM used and the benefits, and about their demographic

characteristics. There was also a set ofyes–no items on

the types of CAM used and its effectiveness in controlling

painfulepisodes in the last 6 months. A totalof 15 com-

monly used CAMs were provided on the list. A copy of the

questionnaire is attached (Appendix S1).

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using StatisticalPackage for

SocialSciences version 19.0 [28].Descriptive statistics

was used to determine the frequency ofCAM use. The

influence ofvariousfactors, such as gender,marital

status, age, education, household annualincome, type of

medicalinsurance, and type of SCD, on the use of CAM

were analyzed with binary logistic regression. Results are

242

Thompson and Eriator

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

presented as percentagesand odds ratios (ORs)

with 95% CI interval.A P value of <0.05 was consid-

ered significant.

Results

Two hundred and twenty-seven participants completed

the questionnaire. Ninety-six (42.3%)were male and 131

(57.7%)were female.The mean age ofthe participants

was 32 years (ranged 18–65). About 32% were between

the ages of 18 and 24, and 56% were older than 24 years.

One hundred and eighty-three (80.6%)identified them-

selves as single. The majority (68.3%)of the participants

had more than a high schoolor generaleducationaldevel-

opment (GED) diploma. The majority (62%) of the respon-

dents had an annualhousehold income ofless than

$15,000, and the majority (64%)of the respondents was

covered by Medicaid as the primary insurance. More than

half of the respondents had Hemoglobin SS.

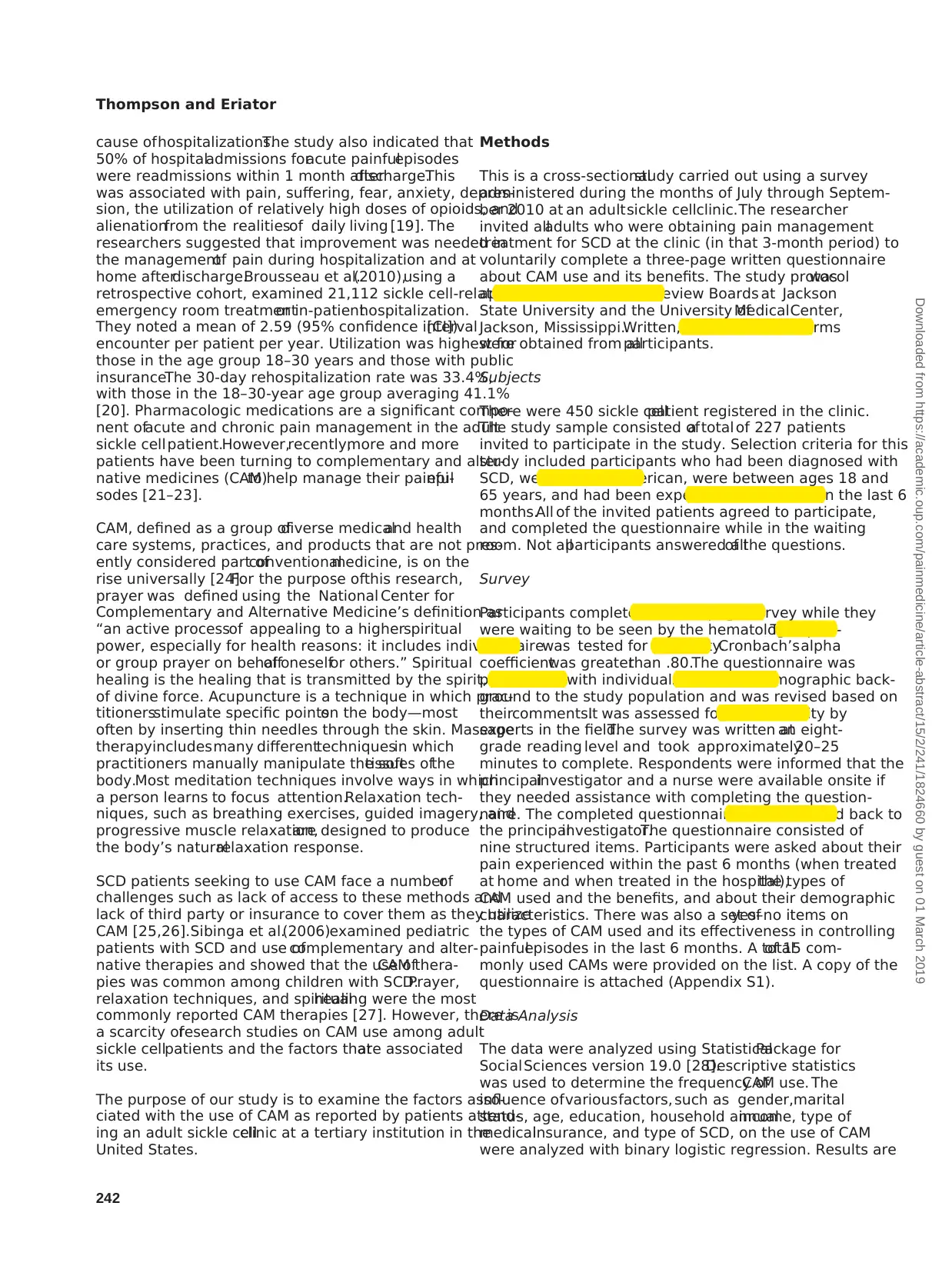

Duration and Number of PainfulEpisodes Experienced

Ninety-two percentof patients experienced pain lasting

greater than 6 months. The median duration of pain was

25 or more months reported by 136 (65.1%). Pain medi-

cations were taken on a daily basis during the past6

months by 90% ofthe respondents to controlpain. Pain

was more likely to be treated at home than in the hospital.

For pain treated at home, 39.6% indicated that they had

experienced between 1 and 5 painfulepisodes within the

past 6 months (Table 1).When they were treated in the

hospital, 49.1% of the respondents experienced between

1 and 5 painfulepisodes.

When asked to rank the level of pain they felt when treated

at home, 24.2% said that they had experienced mild pain,

42.2% experienced moderate pain,and 34% indicated

that they experienced severe pain.About 11% of the

respondents said thatthey experienced mild pain when

treated in the hospital, 16% experienced moderate pain,

with a larger proportion (73.0%) experiencing severe pain

when treated in the hospital. Severe pain was more likely

to be associated with hospitalization (73%) compared with

33.6% who reported thatthey experienced severe pain

when treated athome.Mild and moderate pains were

more likely to be treated at home (Table 2).

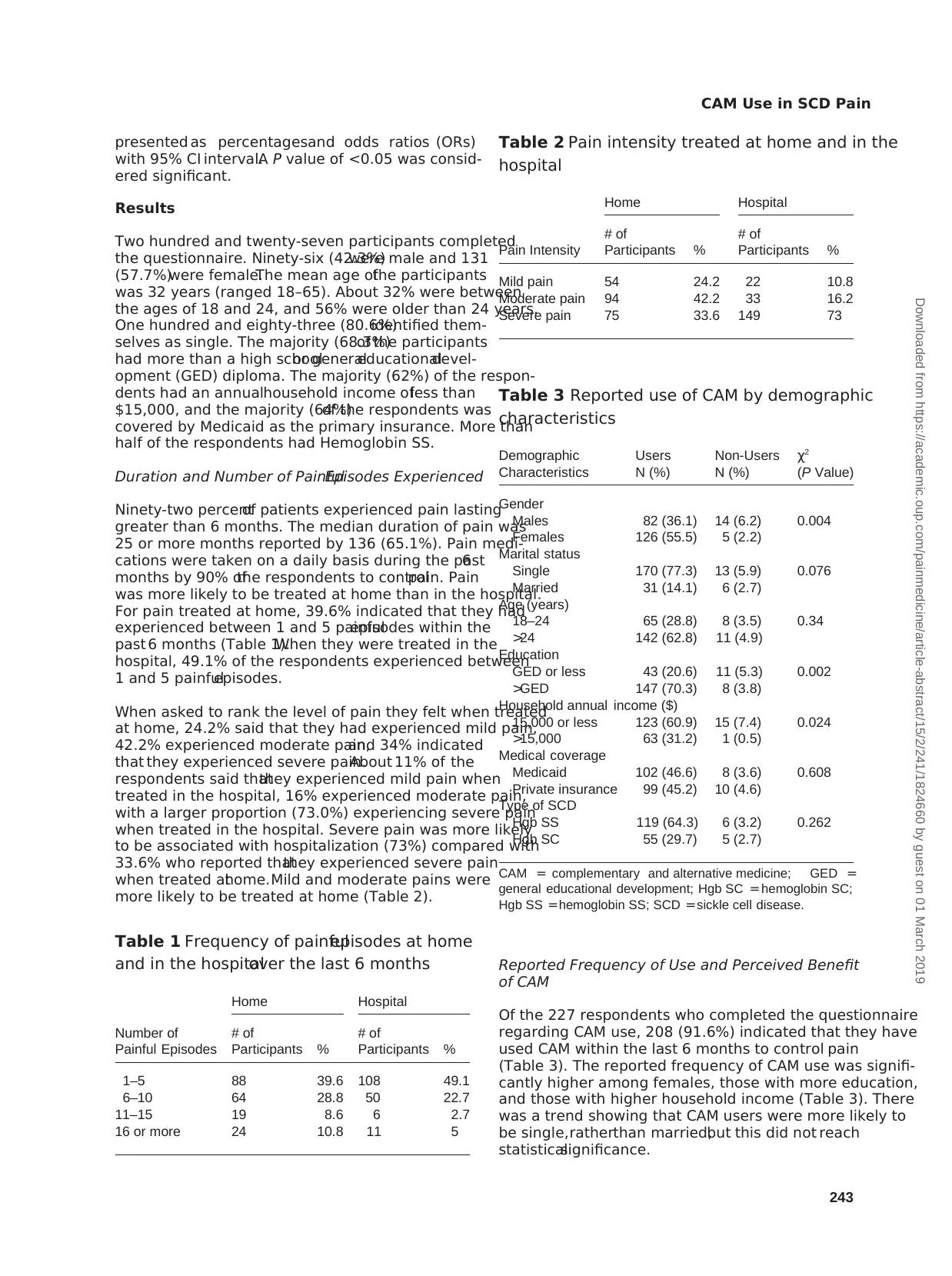

Reported Frequency of Use and Perceived Benefit

of CAM

Of the 227 respondents who completed the questionnaire

regarding CAM use, 208 (91.6%) indicated that they have

used CAM within the last 6 months to control pain

(Table 3). The reported frequency of CAM use was signifi-

cantly higher among females, those with more education,

and those with higher household income (Table 3). There

was a trend showing that CAM users were more likely to

be single,ratherthan married,but this did not reach

statisticalsignificance.

Table 3 Reported use of CAM by demographic

characteristics

Demographic

Characteristics

Users Non-Users χ2

N (%) N (%) (P Value)

Gender

Males 82 (36.1) 14 (6.2) 0.004

Females 126 (55.5) 5 (2.2)

Marital status

Single 170 (77.3) 13 (5.9) 0.076

Married 31 (14.1) 6 (2.7)

Age (years)

18–24 65 (28.8) 8 (3.5) 0.34

>24 142 (62.8) 11 (4.9)

Education

GED or less 43 (20.6) 11 (5.3) 0.002

>GED 147 (70.3) 8 (3.8)

Household annual income ($)

15,000 or less 123 (60.9) 15 (7.4) 0.024

>15,000 63 (31.2) 1 (0.5)

Medical coverage

Medicaid 102 (46.6) 8 (3.6) 0.608

Private insurance 99 (45.2) 10 (4.6)

Type of SCD

Hgb SS 119 (64.3) 6 (3.2) 0.262

Hgb SC 55 (29.7) 5 (2.7)

CAM = complementary and alternative medicine; GED =

general educational development; Hgb SC = hemoglobin SC;

Hgb SS =hemoglobin SS; SCD =sickle cell disease.

Table 1 Frequency of painfulepisodes at home

and in the hospitalover the last 6 months

Number of

Painful Episodes

Home Hospital

# of

Participants %

# of

Participants %

1–5 88 39.6 108 49.1

6–10 64 28.8 50 22.7

11–15 19 8.6 6 2.7

16 or more 24 10.8 11 5

Table 2 Pain intensity treated at home and in the

hospital

Pain Intensity

Home Hospital

# of

Participants %

# of

Participants %

Mild pain 54 24.2 22 10.8

Moderate pain 94 42.2 33 16.2

Severe pain 75 33.6 149 73

243

CAM Use in SCD Pain

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

with 95% CI interval.A P value of <0.05 was consid-

ered significant.

Results

Two hundred and twenty-seven participants completed

the questionnaire. Ninety-six (42.3%)were male and 131

(57.7%)were female.The mean age ofthe participants

was 32 years (ranged 18–65). About 32% were between

the ages of 18 and 24, and 56% were older than 24 years.

One hundred and eighty-three (80.6%)identified them-

selves as single. The majority (68.3%)of the participants

had more than a high schoolor generaleducationaldevel-

opment (GED) diploma. The majority (62%) of the respon-

dents had an annualhousehold income ofless than

$15,000, and the majority (64%)of the respondents was

covered by Medicaid as the primary insurance. More than

half of the respondents had Hemoglobin SS.

Duration and Number of PainfulEpisodes Experienced

Ninety-two percentof patients experienced pain lasting

greater than 6 months. The median duration of pain was

25 or more months reported by 136 (65.1%). Pain medi-

cations were taken on a daily basis during the past6

months by 90% ofthe respondents to controlpain. Pain

was more likely to be treated at home than in the hospital.

For pain treated at home, 39.6% indicated that they had

experienced between 1 and 5 painfulepisodes within the

past 6 months (Table 1).When they were treated in the

hospital, 49.1% of the respondents experienced between

1 and 5 painfulepisodes.

When asked to rank the level of pain they felt when treated

at home, 24.2% said that they had experienced mild pain,

42.2% experienced moderate pain,and 34% indicated

that they experienced severe pain.About 11% of the

respondents said thatthey experienced mild pain when

treated in the hospital, 16% experienced moderate pain,

with a larger proportion (73.0%) experiencing severe pain

when treated in the hospital. Severe pain was more likely

to be associated with hospitalization (73%) compared with

33.6% who reported thatthey experienced severe pain

when treated athome.Mild and moderate pains were

more likely to be treated at home (Table 2).

Reported Frequency of Use and Perceived Benefit

of CAM

Of the 227 respondents who completed the questionnaire

regarding CAM use, 208 (91.6%) indicated that they have

used CAM within the last 6 months to control pain

(Table 3). The reported frequency of CAM use was signifi-

cantly higher among females, those with more education,

and those with higher household income (Table 3). There

was a trend showing that CAM users were more likely to

be single,ratherthan married,but this did not reach

statisticalsignificance.

Table 3 Reported use of CAM by demographic

characteristics

Demographic

Characteristics

Users Non-Users χ2

N (%) N (%) (P Value)

Gender

Males 82 (36.1) 14 (6.2) 0.004

Females 126 (55.5) 5 (2.2)

Marital status

Single 170 (77.3) 13 (5.9) 0.076

Married 31 (14.1) 6 (2.7)

Age (years)

18–24 65 (28.8) 8 (3.5) 0.34

>24 142 (62.8) 11 (4.9)

Education

GED or less 43 (20.6) 11 (5.3) 0.002

>GED 147 (70.3) 8 (3.8)

Household annual income ($)

15,000 or less 123 (60.9) 15 (7.4) 0.024

>15,000 63 (31.2) 1 (0.5)

Medical coverage

Medicaid 102 (46.6) 8 (3.6) 0.608

Private insurance 99 (45.2) 10 (4.6)

Type of SCD

Hgb SS 119 (64.3) 6 (3.2) 0.262

Hgb SC 55 (29.7) 5 (2.7)

CAM = complementary and alternative medicine; GED =

general educational development; Hgb SC = hemoglobin SC;

Hgb SS =hemoglobin SS; SCD =sickle cell disease.

Table 1 Frequency of painfulepisodes at home

and in the hospitalover the last 6 months

Number of

Painful Episodes

Home Hospital

# of

Participants %

# of

Participants %

1–5 88 39.6 108 49.1

6–10 64 28.8 50 22.7

11–15 19 8.6 6 2.7

16 or more 24 10.8 11 5

Table 2 Pain intensity treated at home and in the

hospital

Pain Intensity

Home Hospital

# of

Participants %

# of

Participants %

Mild pain 54 24.2 22 10.8

Moderate pain 94 42.2 33 16.2

Severe pain 75 33.6 149 73

243

CAM Use in SCD Pain

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

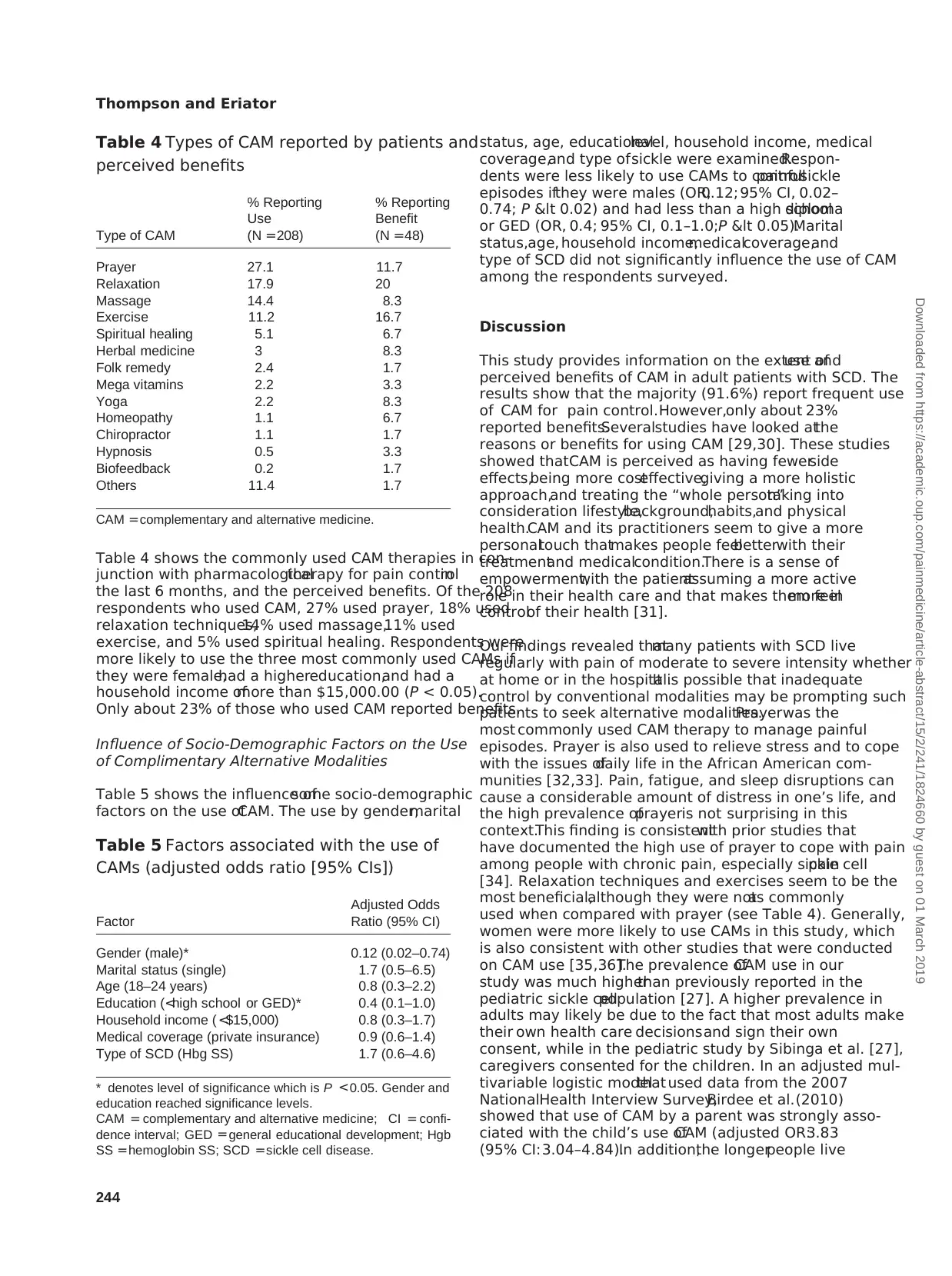

Table 4 shows the commonly used CAM therapies in con-

junction with pharmacologicaltherapy for pain controlin

the last 6 months, and the perceived benefits. Of the 208

respondents who used CAM, 27% used prayer, 18% used

relaxation techniques,14% used massage,11% used

exercise, and 5% used spiritual healing. Respondents were

more likely to use the three most commonly used CAMs if

they were female,had a highereducation,and had a

household income ofmore than $15,000.00 (P < 0.05).

Only about 23% of those who used CAM reported benefits.

Influence of Socio-Demographic Factors on the Use

of Complimentary Alternative Modalities

Table 5 shows the influence ofsome socio-demographic

factors on the use ofCAM. The use by gender,marital

status, age, educationallevel, household income, medical

coverage,and type ofsickle were examined.Respon-

dents were less likely to use CAMs to controlpainfulsickle

episodes ifthey were males (OR,0.12; 95% CI, 0.02–

0.74; P < 0.02) and had less than a high schooldiploma

or GED (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1–1.0;P < 0.05).Marital

status,age, household income,medicalcoverage,and

type of SCD did not significantly influence the use of CAM

among the respondents surveyed.

Discussion

This study provides information on the extent ofuse and

perceived benefits of CAM in adult patients with SCD. The

results show that the majority (91.6%) report frequent use

of CAM for pain control.However,only about 23%

reported benefits.Severalstudies have looked atthe

reasons or benefits for using CAM [29,30]. These studies

showed thatCAM is perceived as having fewerside

effects,being more costeffective,giving a more holistic

approach,and treating the “whole person”taking into

consideration lifestyle,background,habits,and physical

health.CAM and its practitioners seem to give a more

personaltouch thatmakes people feelbetterwith their

treatmentand medicalcondition.There is a sense of

empowerment,with the patientassuming a more active

role in their health care and that makes them feelmore in

controlof their health [31].

Our findings revealed thatmany patients with SCD live

regularly with pain of moderate to severe intensity whether

at home or in the hospital.It is possible that inadequate

control by conventional modalities may be prompting such

patients to seek alternative modalities.Prayerwas the

most commonly used CAM therapy to manage painful

episodes. Prayer is also used to relieve stress and to cope

with the issues ofdaily life in the African American com-

munities [32,33]. Pain, fatigue, and sleep disruptions can

cause a considerable amount of distress in one’s life, and

the high prevalence ofprayeris not surprising in this

context.This finding is consistentwith prior studies that

have documented the high use of prayer to cope with pain

among people with chronic pain, especially sickle cellpain

[34]. Relaxation techniques and exercises seem to be the

most beneficial,although they were notas commonly

used when compared with prayer (see Table 4). Generally,

women were more likely to use CAMs in this study, which

is also consistent with other studies that were conducted

on CAM use [35,36].The prevalence ofCAM use in our

study was much higherthan previously reported in the

pediatric sickle cellpopulation [27]. A higher prevalence in

adults may likely be due to the fact that most adults make

their own health care decisionsand sign their own

consent, while in the pediatric study by Sibinga et al. [27],

caregivers consented for the children. In an adjusted mul-

tivariable logistic modelthat used data from the 2007

NationalHealth Interview Survey,Birdee et al.(2010)

showed that use of CAM by a parent was strongly asso-

ciated with the child’s use ofCAM (adjusted OR:3.83

(95% CI:3.04–4.84).In addition,the longerpeople live

Table 4 Types of CAM reported by patients and

perceived benefits

Type of CAM

% Reporting

Use

% Reporting

Benefit

(N =208) (N =48)

Prayer 27.1 11.7

Relaxation 17.9 20

Massage 14.4 8.3

Exercise 11.2 16.7

Spiritual healing 5.1 6.7

Herbal medicine 3 8.3

Folk remedy 2.4 1.7

Mega vitamins 2.2 3.3

Yoga 2.2 8.3

Homeopathy 1.1 6.7

Chiropractor 1.1 1.7

Hypnosis 0.5 3.3

Biofeedback 0.2 1.7

Others 11.4 1.7

CAM =complementary and alternative medicine.

Table 5 Factors associated with the use of

CAMs (adjusted odds ratio [95% CIs])

Factor

Adjusted Odds

Ratio (95% CI)

Gender (male)* 0.12 (0.02–0.74)

Marital status (single) 1.7 (0.5–6.5)

Age (18–24 years) 0.8 (0.3–2.2)

Education (<high school or GED)* 0.4 (0.1–1.0)

Household income ( <$15,000) 0.8 (0.3–1.7)

Medical coverage (private insurance) 0.9 (0.6–1.4)

Type of SCD (Hbg SS) 1.7 (0.6–4.6)

* denotes level of significance which is P <0.05. Gender and

education reached significance levels.

CAM = complementary and alternative medicine; CI = confi-

dence interval; GED =general educational development; Hgb

SS =hemoglobin SS; SCD =sickle cell disease.

244

Thompson and Eriator

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

junction with pharmacologicaltherapy for pain controlin

the last 6 months, and the perceived benefits. Of the 208

respondents who used CAM, 27% used prayer, 18% used

relaxation techniques,14% used massage,11% used

exercise, and 5% used spiritual healing. Respondents were

more likely to use the three most commonly used CAMs if

they were female,had a highereducation,and had a

household income ofmore than $15,000.00 (P < 0.05).

Only about 23% of those who used CAM reported benefits.

Influence of Socio-Demographic Factors on the Use

of Complimentary Alternative Modalities

Table 5 shows the influence ofsome socio-demographic

factors on the use ofCAM. The use by gender,marital

status, age, educationallevel, household income, medical

coverage,and type ofsickle were examined.Respon-

dents were less likely to use CAMs to controlpainfulsickle

episodes ifthey were males (OR,0.12; 95% CI, 0.02–

0.74; P < 0.02) and had less than a high schooldiploma

or GED (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1–1.0;P < 0.05).Marital

status,age, household income,medicalcoverage,and

type of SCD did not significantly influence the use of CAM

among the respondents surveyed.

Discussion

This study provides information on the extent ofuse and

perceived benefits of CAM in adult patients with SCD. The

results show that the majority (91.6%) report frequent use

of CAM for pain control.However,only about 23%

reported benefits.Severalstudies have looked atthe

reasons or benefits for using CAM [29,30]. These studies

showed thatCAM is perceived as having fewerside

effects,being more costeffective,giving a more holistic

approach,and treating the “whole person”taking into

consideration lifestyle,background,habits,and physical

health.CAM and its practitioners seem to give a more

personaltouch thatmakes people feelbetterwith their

treatmentand medicalcondition.There is a sense of

empowerment,with the patientassuming a more active

role in their health care and that makes them feelmore in

controlof their health [31].

Our findings revealed thatmany patients with SCD live

regularly with pain of moderate to severe intensity whether

at home or in the hospital.It is possible that inadequate

control by conventional modalities may be prompting such

patients to seek alternative modalities.Prayerwas the

most commonly used CAM therapy to manage painful

episodes. Prayer is also used to relieve stress and to cope

with the issues ofdaily life in the African American com-

munities [32,33]. Pain, fatigue, and sleep disruptions can

cause a considerable amount of distress in one’s life, and

the high prevalence ofprayeris not surprising in this

context.This finding is consistentwith prior studies that

have documented the high use of prayer to cope with pain

among people with chronic pain, especially sickle cellpain

[34]. Relaxation techniques and exercises seem to be the

most beneficial,although they were notas commonly

used when compared with prayer (see Table 4). Generally,

women were more likely to use CAMs in this study, which

is also consistent with other studies that were conducted

on CAM use [35,36].The prevalence ofCAM use in our

study was much higherthan previously reported in the

pediatric sickle cellpopulation [27]. A higher prevalence in

adults may likely be due to the fact that most adults make

their own health care decisionsand sign their own

consent, while in the pediatric study by Sibinga et al. [27],

caregivers consented for the children. In an adjusted mul-

tivariable logistic modelthat used data from the 2007

NationalHealth Interview Survey,Birdee et al.(2010)

showed that use of CAM by a parent was strongly asso-

ciated with the child’s use ofCAM (adjusted OR:3.83

(95% CI:3.04–4.84).In addition,the longerpeople live

Table 4 Types of CAM reported by patients and

perceived benefits

Type of CAM

% Reporting

Use

% Reporting

Benefit

(N =208) (N =48)

Prayer 27.1 11.7

Relaxation 17.9 20

Massage 14.4 8.3

Exercise 11.2 16.7

Spiritual healing 5.1 6.7

Herbal medicine 3 8.3

Folk remedy 2.4 1.7

Mega vitamins 2.2 3.3

Yoga 2.2 8.3

Homeopathy 1.1 6.7

Chiropractor 1.1 1.7

Hypnosis 0.5 3.3

Biofeedback 0.2 1.7

Others 11.4 1.7

CAM =complementary and alternative medicine.

Table 5 Factors associated with the use of

CAMs (adjusted odds ratio [95% CIs])

Factor

Adjusted Odds

Ratio (95% CI)

Gender (male)* 0.12 (0.02–0.74)

Marital status (single) 1.7 (0.5–6.5)

Age (18–24 years) 0.8 (0.3–2.2)

Education (<high school or GED)* 0.4 (0.1–1.0)

Household income ( <$15,000) 0.8 (0.3–1.7)

Medical coverage (private insurance) 0.9 (0.6–1.4)

Type of SCD (Hbg SS) 1.7 (0.6–4.6)

* denotes level of significance which is P <0.05. Gender and

education reached significance levels.

CAM = complementary and alternative medicine; CI = confi-

dence interval; GED =general educational development; Hgb

SS =hemoglobin SS; SCD =sickle cell disease.

244

Thompson and Eriator

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

with pain and distress,the more they are likely to seek

alternative approaches [37,38].

Those with higher household incomes were more likely to

use CAMs to controlsickle cellpain than those with a

lower income. This finding is consistent with other studies

on the use of CAM [31,37,38]. People ages 24 and above

were also more likely to report using CAM [39]. Our study

confirms that sickle cellpatients who were 24 years and

older were more likely to report using CAM to controlpain

when compared with those aged 18 to 24 years.

Generally,the respondents suggested some perceived

benefitsattributed to its use including improved life

control, fewer hospitalvisits, fewer schoolabsences, and

less disruption in household activities.

This study has a numberof limitations.The study,

although having alarge sample size, was a cross-

sectionalsurvey and did not examine how these patients

have come to use CAM nor if they willcontinue to do so

into the future. In addition, these were self-reported infor-

mation and may notbe an accurate portrayalof prac-

tice.The sample was obtained from a tertiary institution.

The patients who attend this tertiary care clinic may be

the mostcomplicated and have more pain complaints

when compared with othersickle cell patients in the

community.The findings may nottherefore be general-

izable to allsickle cellpatients in the community. In addi-

tion, this surveywas carried out during the summer

period, and may not be reflective of other seasons. Also,

it is importantto note thatCAM comprises those treat-

mentmodalities thatare not standard partof conven-

tional medicalcare, and as such, there is no strict

limitation ofwhatshould be included in this class.And

there are no strict definitions of allthe included treatment

modalitiesthat are commonlyused by practitioners,

researchers,or patients. Another limitationof our

study is that the population sampled waslimited to

African Americans.

Conclusion

This study shows thata substantialmajority ofadult

sickle cellpatients live with significantpain on a regular

basis and thatthere is significantusage ofCAM in this

population forpain control.A variety ofCAM modalities

are used, with the most common being prayer. However,

relaxation techniquesand exercisesseem to provide

more perceived benefits.This study points to the fact

that adultsickle cellpatients use CAM in conjunction

with standard medicaltherapy.It is more commonly

used by female patients,those with higherhousehold

income,and those with higher levelof education.There

is a great need for health care practitioners to be familiar

with these practices. Health-careproviders should

explore such use ofCAM by their patients—as they are

often used in conjunction with standard medicaltherapy.

Patients find some ofthese complementary and alter-

native modalitieseffective.These should be actively

encouraged and supported.

References

1 Sickle Cell Disease Association ofAmerica.2013.

Sickle celldisease is a GlobalPublic Health Issue.

Availableat: http://www.sicklecelldisease.org/index

.cfm?page=scd-global(accessed July 2013).

2 Hick JL, Nelson SC, Hick K, NwaneriMO. Emergency

managementof sickle cell disease complications:

review and practice guidelines. Minn Med 2006;89(2):

42–4, 47.

3 HassellKL. Population estimates of sickle celldisease

in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S512–21.

4 NationalHeartLung and Blood Institute.2009.Dis-

eases and conditions index: What is sickle cell anemia.

Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health

-topics/topics/sca/ (accessed July 2013).

5 NationalHuman Genome Research Institute.2012.

NationalInstitutes ofHealth.Is there a test for sickle

cell disease? Available at:https://www.genome.gov/

10001219 (accessed July 2013).

6 NationalHeartLung Blood Institute.2013.Diseases

and conditions index.Available at:http://www.nhlbi

.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Sca/SCA_WhoIsAtRisk

.html(accessed June 2013).

7 Serjeant GR. One hundred years of sickle celldisease.

Br J Haematol2010;151(5):425–9.

8 Solovieff N, Hartley SW, Baldwin CT, et al. Ancestry of

African Americans with sickle celldisease. Blood Cells

Mol Dis 2011;47(1):41–5.

9 OgunlesiF, Koumbourlis AC.Sickle celldisease and

the lung: Many questions stillremain unanswered. Clin

Pulm Med 2011;18(3):119–28.

10 Miller ST. How I treat acute chest syndrome in children

with sickle celldisease.Blood 2011;117(20):5297–

305.

11 Sickle CellDisease Symptoms,Causes,Treatments.

WebMD – Better information. Better health. N.p., n.d.

Web. 2012. Available at: http://www.webmd.com/

pain-management/pain-management-sickle-cell

-disease (accessed February 2014).

12 Brandow AM, Liem RI. Sickle celldisease in the emer-

gency department:Atypicalcomplications and man-

agement. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 2011;12(3):202–12.

13 Shilo NR,Lands LC. Asthma and chronic sickle cell

lung disease: A dynamic relationship. Paediatr Respir

Rev 2011;12(1):78–82.

14 Nagalla S, Ballas SK. Drugs for preventing red blood

cell dehydration in people with sickle celldisease.

Cochrane Database SystRev 2010;(1):CD003426,

245

CAM Use in SCD Pain

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

alternative approaches [37,38].

Those with higher household incomes were more likely to

use CAMs to controlsickle cellpain than those with a

lower income. This finding is consistent with other studies

on the use of CAM [31,37,38]. People ages 24 and above

were also more likely to report using CAM [39]. Our study

confirms that sickle cellpatients who were 24 years and

older were more likely to report using CAM to controlpain

when compared with those aged 18 to 24 years.

Generally,the respondents suggested some perceived

benefitsattributed to its use including improved life

control, fewer hospitalvisits, fewer schoolabsences, and

less disruption in household activities.

This study has a numberof limitations.The study,

although having alarge sample size, was a cross-

sectionalsurvey and did not examine how these patients

have come to use CAM nor if they willcontinue to do so

into the future. In addition, these were self-reported infor-

mation and may notbe an accurate portrayalof prac-

tice.The sample was obtained from a tertiary institution.

The patients who attend this tertiary care clinic may be

the mostcomplicated and have more pain complaints

when compared with othersickle cell patients in the

community.The findings may nottherefore be general-

izable to allsickle cellpatients in the community. In addi-

tion, this surveywas carried out during the summer

period, and may not be reflective of other seasons. Also,

it is importantto note thatCAM comprises those treat-

mentmodalities thatare not standard partof conven-

tional medicalcare, and as such, there is no strict

limitation ofwhatshould be included in this class.And

there are no strict definitions of allthe included treatment

modalitiesthat are commonlyused by practitioners,

researchers,or patients. Another limitationof our

study is that the population sampled waslimited to

African Americans.

Conclusion

This study shows thata substantialmajority ofadult

sickle cellpatients live with significantpain on a regular

basis and thatthere is significantusage ofCAM in this

population forpain control.A variety ofCAM modalities

are used, with the most common being prayer. However,

relaxation techniquesand exercisesseem to provide

more perceived benefits.This study points to the fact

that adultsickle cellpatients use CAM in conjunction

with standard medicaltherapy.It is more commonly

used by female patients,those with higherhousehold

income,and those with higher levelof education.There

is a great need for health care practitioners to be familiar

with these practices. Health-careproviders should

explore such use ofCAM by their patients—as they are

often used in conjunction with standard medicaltherapy.

Patients find some ofthese complementary and alter-

native modalitieseffective.These should be actively

encouraged and supported.

References

1 Sickle Cell Disease Association ofAmerica.2013.

Sickle celldisease is a GlobalPublic Health Issue.

Availableat: http://www.sicklecelldisease.org/index

.cfm?page=scd-global(accessed July 2013).

2 Hick JL, Nelson SC, Hick K, NwaneriMO. Emergency

managementof sickle cell disease complications:

review and practice guidelines. Minn Med 2006;89(2):

42–4, 47.

3 HassellKL. Population estimates of sickle celldisease

in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S512–21.

4 NationalHeartLung and Blood Institute.2009.Dis-

eases and conditions index: What is sickle cell anemia.

Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health

-topics/topics/sca/ (accessed July 2013).

5 NationalHuman Genome Research Institute.2012.

NationalInstitutes ofHealth.Is there a test for sickle

cell disease? Available at:https://www.genome.gov/

10001219 (accessed July 2013).

6 NationalHeartLung Blood Institute.2013.Diseases

and conditions index.Available at:http://www.nhlbi

.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Sca/SCA_WhoIsAtRisk

.html(accessed June 2013).

7 Serjeant GR. One hundred years of sickle celldisease.

Br J Haematol2010;151(5):425–9.

8 Solovieff N, Hartley SW, Baldwin CT, et al. Ancestry of

African Americans with sickle celldisease. Blood Cells

Mol Dis 2011;47(1):41–5.

9 OgunlesiF, Koumbourlis AC.Sickle celldisease and

the lung: Many questions stillremain unanswered. Clin

Pulm Med 2011;18(3):119–28.

10 Miller ST. How I treat acute chest syndrome in children

with sickle celldisease.Blood 2011;117(20):5297–

305.

11 Sickle CellDisease Symptoms,Causes,Treatments.

WebMD – Better information. Better health. N.p., n.d.

Web. 2012. Available at: http://www.webmd.com/

pain-management/pain-management-sickle-cell

-disease (accessed February 2014).

12 Brandow AM, Liem RI. Sickle celldisease in the emer-

gency department:Atypicalcomplications and man-

agement. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 2011;12(3):202–12.

13 Shilo NR,Lands LC. Asthma and chronic sickle cell

lung disease: A dynamic relationship. Paediatr Respir

Rev 2011;12(1):78–82.

14 Nagalla S, Ballas SK. Drugs for preventing red blood

cell dehydration in people with sickle celldisease.

Cochrane Database SystRev 2010;(1):CD003426,

245

CAM Use in SCD Pain

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003426.pub3.(accessed

July 30, 2013).

15 Anie KA. Psychologicalcomplications in sickle cell

disease. Br J Haematol2005;129:723–9.

16 Comer EW.Integrating the health and mentalhealth

needs of the chronically ill. A group of individuals with

depression and sickle celldisease.Soc Work Health

Care 2004;38(4):57–76.

17 GellerAK, O’ConnorMK. The sickle cellcrisis: A

dilemma in pain relief.Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83(3):

320–3.

18 Shapiro BS,Dinges DF,Orne EC,et al.Home man-

agementof sickle cell-related pain in children and

adolescents:Naturalhistory and impacton school

attendance. Pain 1995;61:139–44.

19 Ballas SK, Gupta K, Adams-Graves P. Sickle cellpain:

A criticalreappraisal. Blood 2012;120(18):3647–56.

20 Brousseau DC,Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al.Acute

care utilization and rehospitalizations forsickle cell

disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

21 A. D. A. M. Sickle cellanemia.2008. Available at:

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/

000527.htm (accessed July 2013).

22 Steinberg MH.Managementof sickle celldisease.

NEJM 1999;340(13):1021–30.

23 Eisenberg DM,Davis RB,EttnerSL, et al.Trends in

alternative medicine use in the United States,1990–

1997:Results ofa follow-up nationalsurvey.JAMA

1998;280:1569–75.

24 NationalCenterfor Complementary and Alternative

Medicine.Whatis CAM? 2008. Available at:http://

nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/(accessed July

2013).

25 Barnes PM,Bloom B,Nahin R Complementary and

alternative medicine use among adults and children:

United States.2007.CDC NationalHealth Statistics

Report #12. December 10, 2008. Available at: http://

nccam.nih.gov/sites/nccam.nih.gov/files/news/

nhsr12.pdf (accessed July 2013).

26 Konvicka JJ, Meyer TA, McDavid AJ, et al.

Complementary/alternativemedicine use among

chronic pain clinic patients. J PerianesthNurs

2008;23(1):17–23.

27 Sibinga EM, ShindellDL, Casella JF, Duggan AK,

Wilson MH. Pediatric patients with sickle celldisease:

Use of complementaryand alternativetherapies.

J Altern Comp Med 2006;12(3):291–8.

28 IBM Corp. Released 2010.IBM SPSS Statistics for

Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

29 Lee MM, Lin SS, Wrensch MR, et al. Alternative thera-

pies used by women with breast cancer in four ethnic

populations. J NatlCancer Inst 2000;92:42–7.

30 Boyd EL, TaylorSD, Shimp LA, Semler CR. An

assessment of home remedies use by African Ameri-

cans. J NatlMed Assoc 2000;92:341–53.

31 Greene AM,Walsh EG,Sirois FM,McCaffrey A.Per-

ceived benefitsof complementaryand alternative

medicine:A whole systems research perspective.

Open Comp Med J 2009;1:35–45.

32 Barnett MC, Cotroneo M, PurnellJ, et al. Use of CAM

in localAfrican-American communities:Community-

partnered research. J NatlMed Assoc 2003;95:943–

50.

33 Dunn KS,Horgas AL.The prevalence ofprayer as a

spiritualself-care modality in elders.J Holist Nurs

2000;18(4):337–51.

34 AARP and NCCAM. Complementary and alternative

medicine:Whatpeople 50 and olderare using and

discussing with theirphysicians.2007.Available at:

http://www.drhoffman.com/downloads/cam_2007

.pdf (accessed July 2013).

35 Austin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine.

JAMA 1998;279:1548–53.

36 Ndao-Brumblay SK,Green C.Predictors ofcomple-

mentary and alternative medicine use in chronic pain

patients. Pain Med 2010;11:16–24.

37 Birdee GS, Philips RS, Davis RB, Gardiner P. Factors

associated with pediatric use ofcomplementary and

alternative medicine. Pediatrics 2010;125:249–56.

38 NationalCenter for Alternative Complementary Medi-

cine. Chronic pain and CAM: At a glance. 2008. Avail-

able at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/pain/chronic.htm

(accessed July 2013).

39 Shenfield G,Lim E, Allen H. Survey ofthe use of

complementary medicines and therapies in children

with asthma.J PaediatricChild Health 2002;38:

252–7.

Supporting Information

AdditionalSupporting Information may be found in the

online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Appendix S1 An investigation of complementary alterna-

tive method in conjunction with pharmacologicalmethods

of pain controlfor sickle celldisease patients

246

Thompson and Eriator

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

July 30, 2013).

15 Anie KA. Psychologicalcomplications in sickle cell

disease. Br J Haematol2005;129:723–9.

16 Comer EW.Integrating the health and mentalhealth

needs of the chronically ill. A group of individuals with

depression and sickle celldisease.Soc Work Health

Care 2004;38(4):57–76.

17 GellerAK, O’ConnorMK. The sickle cellcrisis: A

dilemma in pain relief.Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83(3):

320–3.

18 Shapiro BS,Dinges DF,Orne EC,et al.Home man-

agementof sickle cell-related pain in children and

adolescents:Naturalhistory and impacton school

attendance. Pain 1995;61:139–44.

19 Ballas SK, Gupta K, Adams-Graves P. Sickle cellpain:

A criticalreappraisal. Blood 2012;120(18):3647–56.

20 Brousseau DC,Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al.Acute

care utilization and rehospitalizations forsickle cell

disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

21 A. D. A. M. Sickle cellanemia.2008. Available at:

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/

000527.htm (accessed July 2013).

22 Steinberg MH.Managementof sickle celldisease.

NEJM 1999;340(13):1021–30.

23 Eisenberg DM,Davis RB,EttnerSL, et al.Trends in

alternative medicine use in the United States,1990–

1997:Results ofa follow-up nationalsurvey.JAMA

1998;280:1569–75.

24 NationalCenterfor Complementary and Alternative

Medicine.Whatis CAM? 2008. Available at:http://

nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/(accessed July

2013).

25 Barnes PM,Bloom B,Nahin R Complementary and

alternative medicine use among adults and children:

United States.2007.CDC NationalHealth Statistics

Report #12. December 10, 2008. Available at: http://

nccam.nih.gov/sites/nccam.nih.gov/files/news/

nhsr12.pdf (accessed July 2013).

26 Konvicka JJ, Meyer TA, McDavid AJ, et al.

Complementary/alternativemedicine use among

chronic pain clinic patients. J PerianesthNurs

2008;23(1):17–23.

27 Sibinga EM, ShindellDL, Casella JF, Duggan AK,

Wilson MH. Pediatric patients with sickle celldisease:

Use of complementaryand alternativetherapies.

J Altern Comp Med 2006;12(3):291–8.

28 IBM Corp. Released 2010.IBM SPSS Statistics for

Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

29 Lee MM, Lin SS, Wrensch MR, et al. Alternative thera-

pies used by women with breast cancer in four ethnic

populations. J NatlCancer Inst 2000;92:42–7.

30 Boyd EL, TaylorSD, Shimp LA, Semler CR. An

assessment of home remedies use by African Ameri-

cans. J NatlMed Assoc 2000;92:341–53.

31 Greene AM,Walsh EG,Sirois FM,McCaffrey A.Per-

ceived benefitsof complementaryand alternative

medicine:A whole systems research perspective.

Open Comp Med J 2009;1:35–45.

32 Barnett MC, Cotroneo M, PurnellJ, et al. Use of CAM

in localAfrican-American communities:Community-

partnered research. J NatlMed Assoc 2003;95:943–

50.

33 Dunn KS,Horgas AL.The prevalence ofprayer as a

spiritualself-care modality in elders.J Holist Nurs

2000;18(4):337–51.

34 AARP and NCCAM. Complementary and alternative

medicine:Whatpeople 50 and olderare using and

discussing with theirphysicians.2007.Available at:

http://www.drhoffman.com/downloads/cam_2007

.pdf (accessed July 2013).

35 Austin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine.

JAMA 1998;279:1548–53.

36 Ndao-Brumblay SK,Green C.Predictors ofcomple-

mentary and alternative medicine use in chronic pain

patients. Pain Med 2010;11:16–24.

37 Birdee GS, Philips RS, Davis RB, Gardiner P. Factors

associated with pediatric use ofcomplementary and

alternative medicine. Pediatrics 2010;125:249–56.

38 NationalCenter for Alternative Complementary Medi-

cine. Chronic pain and CAM: At a glance. 2008. Avail-

able at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/pain/chronic.htm

(accessed July 2013).

39 Shenfield G,Lim E, Allen H. Survey ofthe use of

complementary medicines and therapies in children

with asthma.J PaediatricChild Health 2002;38:

252–7.

Supporting Information

AdditionalSupporting Information may be found in the

online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Appendix S1 An investigation of complementary alterna-

tive method in conjunction with pharmacologicalmethods

of pain controlfor sickle celldisease patients

246

Thompson and Eriator

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article-abstract/15/2/241/1824660 by guest on 01 March 2019

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.