Primary Health Care Improvement: Report on Global Stakeholder Meeting

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/12

|25

|9855

|325

Report

AI Summary

This report summarizes the key discussions and outcomes of the Primary Health Care Improvement Global Stakeholder Meeting held on 6-8 April 2016. The meeting focused on improving primary health care (PHC) performance through better measurement, knowledge management, and collaborative action. It highlights the importance of strong PHC systems in achieving better health outcomes equitably and cost-effectively, emphasizing domains such as access, comprehensiveness, continuity, coordination, people-centeredness, and quality. The report outlines efforts by initiatives like the Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) and the Health Data Collaborative (HDC) to enhance PHC measurement and data utilization. It addresses common causes of poor PHC performance and proposes strategies for improvement, including the WHO Global Challenge on Primary Health Care Improvement. The report serves as a roadmap for stakeholders to support country-level PHC measurement and improvement efforts, aiming to advance evidence-informed decision-making and overall performance enhancement in primary health care systems globally.

Primary Health Care Improveme

Global Stakeholder Meetin

6-8 April 2016

Global Stakeholder Meetin

6-8 April 2016

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

| P a g e 2

| P a g e 3

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................ 3

Key Messages ............................................................................................................................. 4

Acronym Index ............................................................................................................................ 5

Purpose ...................................................................................................................................... 7

Background ................................................................................................................................. 7

Measurement ............................................................................................................................. 9

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework ................................................................................................. 9

Establishing priorities for PHC measurement ....................................................................................... 10

Health Data Collaborative ................................................................................................................... 13

From Measurement to Improvement ........................................................................................ 15

Accelerating the process of using measurement to drive improvement ............................................... 15

Knowledge Management .................................................................................................................... 16

Action for Improvement ............................................................................................................ 18

Common causes of poor PHC performance .......................................................................................... 18

Strategies for PHC improvement ......................................................................................................... 19

PHC improvement activities (current and future) ................................................................................ 20

Global Challenge for Primary Health Care Improvement ...................................................................... 21

Annex 1: Situation Analysis Measurement ................................................................................ 23

Annex 2: PHCPI Vital Signs ........................................................................................................ 24

This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts, and does not necessarily

represent the decisions or the stated policy of the World Health Organization.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................ 3

Key Messages ............................................................................................................................. 4

Acronym Index ............................................................................................................................ 5

Purpose ...................................................................................................................................... 7

Background ................................................................................................................................. 7

Measurement ............................................................................................................................. 9

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework ................................................................................................. 9

Establishing priorities for PHC measurement ....................................................................................... 10

Health Data Collaborative ................................................................................................................... 13

From Measurement to Improvement ........................................................................................ 15

Accelerating the process of using measurement to drive improvement ............................................... 15

Knowledge Management .................................................................................................................... 16

Action for Improvement ............................................................................................................ 18

Common causes of poor PHC performance .......................................................................................... 18

Strategies for PHC improvement ......................................................................................................... 19

PHC improvement activities (current and future) ................................................................................ 20

Global Challenge for Primary Health Care Improvement ...................................................................... 21

Annex 1: Situation Analysis Measurement ................................................................................ 23

Annex 2: PHCPI Vital Signs ........................................................................................................ 24

This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts, and does not necessarily

represent the decisions or the stated policy of the World Health Organization.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

| P a g e 4

Key Messages

1. Health systems based on high-performing primary health care (PHC) are able to achieve better health

outcomes, more equitably, and at lower relative cost than health systems that over emphasize disease-

specific and/or hospital-based care.

2. Little is known about the performance of PHC, particularly in domains of service delivery: access,

comprehensiveness, continuity, coordination, people-centeredness and quality. Challenges exist across

the measurement spectrum from data collection, analysis, visualization and use for improvement.

3. Recent efforts by international agencies, including the Primary Health Care Performance Initiative

(PHCPI) and the Health Data Collaborative (HDC), offer an opportunity for stakeholders to collaborate

and complement country investments in the area of PHC measurement for improvement.

4. The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) seeks to catalyze improvements in PHC in low-

and middle-income countries by developing better measurement of PHC-relevant domains, increasing

data availability and sharing knowledge.

5. The Health Data Collaborative (HDC) aims to address disparate funding and fragmented sources of

health data that lead to the current inadequacy of data for reliable, timely decision-making. The output

of HDC is more collaborative and efficient investment in country information systems and monitoring

and evaluation plans.

6. This meeting seeks to inform these stakeholder efforts and provide a common work plan for (1)

improved PHC performance measurement including research and development of less measured

domains of quality PHC and incorporation of these measures into existing measurement platforms and

(2) PHC improvement efforts including relevant guidance and tools and the WHO Global Challenge on

Primary Health Care Improvement.

Key Messages

1. Health systems based on high-performing primary health care (PHC) are able to achieve better health

outcomes, more equitably, and at lower relative cost than health systems that over emphasize disease-

specific and/or hospital-based care.

2. Little is known about the performance of PHC, particularly in domains of service delivery: access,

comprehensiveness, continuity, coordination, people-centeredness and quality. Challenges exist across

the measurement spectrum from data collection, analysis, visualization and use for improvement.

3. Recent efforts by international agencies, including the Primary Health Care Performance Initiative

(PHCPI) and the Health Data Collaborative (HDC), offer an opportunity for stakeholders to collaborate

and complement country investments in the area of PHC measurement for improvement.

4. The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) seeks to catalyze improvements in PHC in low-

and middle-income countries by developing better measurement of PHC-relevant domains, increasing

data availability and sharing knowledge.

5. The Health Data Collaborative (HDC) aims to address disparate funding and fragmented sources of

health data that lead to the current inadequacy of data for reliable, timely decision-making. The output

of HDC is more collaborative and efficient investment in country information systems and monitoring

and evaluation plans.

6. This meeting seeks to inform these stakeholder efforts and provide a common work plan for (1)

improved PHC performance measurement including research and development of less measured

domains of quality PHC and incorporation of these measures into existing measurement platforms and

(2) PHC improvement efforts including relevant guidance and tools and the WHO Global Challenge on

Primary Health Care Improvement.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

| P a g e 5

Acronym Index

AeHIN Asia eHealth Information Network

ASSD Africa Symposium on Statistical Development

BMGF

CoP

CQI

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

Community of practice

Continuous quality improvement

CRVS Civil registration and vital statistics

DHIS District Health Information System

GAVI Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization

GFATM The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

GFF Global Financing Facility in Support of Every Woman Every Child

GIZ German Corporation for International Cooperation

HDC Health data collaborative

HMIS Health management information system

IHP+ The international health partnership

IPCHS Integrated, people-centred health services

JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency

LMIC Low and Middle Income Countries

M&E Monitoring and evaluation

NHA National health accounts

NORAD Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PEPFAR The United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief

PHC Primary health care

PHCPI Primary health care performance initiative

RBF Results based financing

SARA Service Availability and Readiness Assessment

SDG Sustainable development goal

SDI Service Delivery Indicators

SPA Service Provision Assessment

UHC Universal health coverage

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

UNSD United Nations Statistical Division

USAID United States Agency for International Development

WBG World Bank Group

WHO World Health Organization

Acronym Index

AeHIN Asia eHealth Information Network

ASSD Africa Symposium on Statistical Development

BMGF

CoP

CQI

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

Community of practice

Continuous quality improvement

CRVS Civil registration and vital statistics

DHIS District Health Information System

GAVI Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization

GFATM The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

GFF Global Financing Facility in Support of Every Woman Every Child

GIZ German Corporation for International Cooperation

HDC Health data collaborative

HMIS Health management information system

IHP+ The international health partnership

IPCHS Integrated, people-centred health services

JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency

LMIC Low and Middle Income Countries

M&E Monitoring and evaluation

NHA National health accounts

NORAD Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PEPFAR The United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief

PHC Primary health care

PHCPI Primary health care performance initiative

RBF Results based financing

SARA Service Availability and Readiness Assessment

SDG Sustainable development goal

SDI Service Delivery Indicators

SPA Service Provision Assessment

UHC Universal health coverage

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

UNSD United Nations Statistical Division

USAID United States Agency for International Development

WBG World Bank Group

WHO World Health Organization

| P a g e 6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

| P a g e 7

Purpose

This document provides background on situation, challenges, and opportunities in the field of

measurement for improvement in primary health care (PHC). It then describes current, relevant multi-

stakeholder efforts to address these challenges and opportunities, followed by key questions for

consideration and potential deliverables for the global stakeholder community. These deliverables (some

underway, some proposed) are offered as a draft roadmap toward a collaborative process for supporting

country PHC measurement and improvement efforts. This document will undergo significant revision with

inputs from the PHC Improvement Global Stakeholder Meeting on 6-8 April to develop a work plan for (1)

improved PHC performance measurement including research and development of less measured domains of

quality PHC and incorporation of these measures into existing measurement platforms and (2) PHC

improvement efforts including the development of relevant guidance and tools and the WHO Global

Challenge on Primary Health Care Improvement.

Background

The highest attainable standard of health, including access to timely, acceptable, affordable, and high-

quality health care is a fundamental right of every human being. Primary health care (PHC), as a regular site

of first-access and on-going care with the capacity to address the majority of health problems, has long been

recognized as critical to attaining health for all.1 Numerous international reviews have bolstered this claim,

demonstrating that health systems based on high-performing PHC are able to achieve better health

outcomes, more equitably (even equilibrating the negative impact of social determinants of health), and at

lower relative cost than health systems that over emphasize selective disease-specific and/or hospital-based

care. 2,3,4,5

It is undeniable that strong PHC is foundational to achieving health for all, particularly the most

marginalized and vulnerable. In addition, strong PHC is essential to attaining today’s leading global health

objectives including Universal Health Coverage (UHC), Integrated People-centred Health Services (IPCHS)6,

and health related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Yet, too often the potential of PHC for dramatic

improvements in the health of populations and function of health systems is undermined by lack of

1 Recognizing that primary care has variable definitions, this paper is grounded in the historical approach of primary health care established at

Alma Ata while emphasising health system and service delivery reforms relevant to primary care. We adopt a definition from the World Health

Report 2008: Primary health care – now more than ever: care that exhibits features of person-centeredness, comprehensiveness, integration,

continuity of care, participation of patients, families and communities. This requires health services that are organized with close-to-client

multidisciplinary teams responsible for a defined population, collaborate with social services and other sectors, and coordinate the contributions of

specialists and community organizations.

2 Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502

3 Kruk, Margaret Elizabeth, et al. "The Contribution of Primary Care to Health and Health Systems in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: a critical

review of major primary care initiatives." Social science & medicine 70.6 (2010): 904-911.

4 Starfield B. Policy relevant determinants of health: an international perspective. Health Policy, 2002, 60:201-218.

5 Rohde J, et al 30 years after Alma-Ata: has primary health care worked in countries?, The Lancet, Volume 372, Issue 9642, 13–19 September

2008, 950-961

6 WHO Framework on integrated people-centred health services was recently adopted by the 138th Session of the Executive Board, and will be

discussed at this year’s World Health Assembly. The framework proposes five interdependent strategies (including reorienting the model of care

around primary-care based systems) for health services to become more integrated and people-centred. The proposed resolution includes a request

for research and development on indicators to trace global progress on integrated people-centered health services; as well as technical support and

guidance to Member States for the implementation, national adaptation and operationalization of the framework.

http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB138/B138_37-en.pdf

Purpose

This document provides background on situation, challenges, and opportunities in the field of

measurement for improvement in primary health care (PHC). It then describes current, relevant multi-

stakeholder efforts to address these challenges and opportunities, followed by key questions for

consideration and potential deliverables for the global stakeholder community. These deliverables (some

underway, some proposed) are offered as a draft roadmap toward a collaborative process for supporting

country PHC measurement and improvement efforts. This document will undergo significant revision with

inputs from the PHC Improvement Global Stakeholder Meeting on 6-8 April to develop a work plan for (1)

improved PHC performance measurement including research and development of less measured domains of

quality PHC and incorporation of these measures into existing measurement platforms and (2) PHC

improvement efforts including the development of relevant guidance and tools and the WHO Global

Challenge on Primary Health Care Improvement.

Background

The highest attainable standard of health, including access to timely, acceptable, affordable, and high-

quality health care is a fundamental right of every human being. Primary health care (PHC), as a regular site

of first-access and on-going care with the capacity to address the majority of health problems, has long been

recognized as critical to attaining health for all.1 Numerous international reviews have bolstered this claim,

demonstrating that health systems based on high-performing PHC are able to achieve better health

outcomes, more equitably (even equilibrating the negative impact of social determinants of health), and at

lower relative cost than health systems that over emphasize selective disease-specific and/or hospital-based

care. 2,3,4,5

It is undeniable that strong PHC is foundational to achieving health for all, particularly the most

marginalized and vulnerable. In addition, strong PHC is essential to attaining today’s leading global health

objectives including Universal Health Coverage (UHC), Integrated People-centred Health Services (IPCHS)6,

and health related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Yet, too often the potential of PHC for dramatic

improvements in the health of populations and function of health systems is undermined by lack of

1 Recognizing that primary care has variable definitions, this paper is grounded in the historical approach of primary health care established at

Alma Ata while emphasising health system and service delivery reforms relevant to primary care. We adopt a definition from the World Health

Report 2008: Primary health care – now more than ever: care that exhibits features of person-centeredness, comprehensiveness, integration,

continuity of care, participation of patients, families and communities. This requires health services that are organized with close-to-client

multidisciplinary teams responsible for a defined population, collaborate with social services and other sectors, and coordinate the contributions of

specialists and community organizations.

2 Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502

3 Kruk, Margaret Elizabeth, et al. "The Contribution of Primary Care to Health and Health Systems in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: a critical

review of major primary care initiatives." Social science & medicine 70.6 (2010): 904-911.

4 Starfield B. Policy relevant determinants of health: an international perspective. Health Policy, 2002, 60:201-218.

5 Rohde J, et al 30 years after Alma-Ata: has primary health care worked in countries?, The Lancet, Volume 372, Issue 9642, 13–19 September

2008, 950-961

6 WHO Framework on integrated people-centred health services was recently adopted by the 138th Session of the Executive Board, and will be

discussed at this year’s World Health Assembly. The framework proposes five interdependent strategies (including reorienting the model of care

around primary-care based systems) for health services to become more integrated and people-centred. The proposed resolution includes a request

for research and development on indicators to trace global progress on integrated people-centered health services; as well as technical support and

guidance to Member States for the implementation, national adaptation and operationalization of the framework.

http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB138/B138_37-en.pdf

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

| P a g e 8

emphasis and underinvestment. As a result, PHC implementation has lagged far behind its aspirational

objectives: continuing to focus on the delivery of a basic package of health interventions for selected priority

diseases rather than comprehensive care, ineffective decentralization that impedes PHC from responding to

local conditions, failing to focus on improved coordination between providers and levels of care, missing out

on the benefits of multidisciplinary care, limiting access hours of PHC facilities, and under-emphasising

health work force development and retention resulting in overworked and under-supported staff.

In most countries, little is known about the performance of PHC, particularly in service delivery domains

that are critical to its effectiveness but often not well measured: access7, comprehensiveness8, continuity9,

coordination10, people-centeredness11 (family and community orientation), and quality (both technical and

interpersonal). These domains characterize high-quality primary care (as first contact care) and help explain

performance variation across country contexts, in all settings from low- to high-income countries. While

there are numerous typologies of primary care, not all of them lead to desirable outcomes and impact.

Measuring these domains of high quality PHC acknowledges their importance in explaining performance

variation and can lead to critical reforms. Increased and improved measurement of PHC performance, with

measures relevant to community, facility, district and national processes, is needed to promote

accountability and guide improvement efforts at each level of the health system. There is tremendous

opportunity to have a major impact on health through targeted measurement of what drives strong primary

health care systems and better utilization of these data for improvement by stakeholders at all levels of the

health system.

Several recent collaborative efforts by international development agencies have drawn further attention

to this area including the Health Data Collaborative (HDC)12 and the Primary Health Care Performance

Initiative (PHCPI). 13 HDC seeks to facilitate and accelerate progress in strengthening country systems for

monitoring progress and performance for accountability and transparency within the context of the health

related SDGs. PHCPI brings together partners to improve PHC in low- and middle-income countries through

better measurement to inform and accelerate national and sub-national PHC progress and knowledge-

sharing.

As a key next step, this meeting serves to engage leadership of Member States, partner organizations,

international development associations, academic partners and WHO to move toward a common roadmap

for strengthened PHC measurement and improvement. Stakeholder input obtained through this meeting will

be used to shape the concrete steps needed to advance the measurement and improvement agenda,

including: (1) improved performance measurement (2) research and development for under-measured

domains (3) improved transparency and accountability (4) and evidence-informed decision making all

leading to (5) performance improvement.

7 Access: Available, affordable services in close proximity to people. Primary care serves as the entry point into the health care system and the

first and regular source of care for most health needs.

8 Comprehensiveness: Delivers a broad spectrum of preventive, promotive, curative and palliative care across the life-course

9 Continuity: Individuals have a relationship with same provider and team over time, health information is available over time, and health

management plans are continuous.

10 Coordination: Primary care offers a hub from which people are guided through the health system, managing care across levels, referring to

specialists as needed and effectively following-up to monitor health progress.

11People-centeredness: an approach to care that consciously adopts individuals’, carers’, families’ and communities’ perspectives as

participants in, and beneficiaries of, trusted health systems that are organized around the comprehensive needs of people rather than individual

diseases, and respects their preferences. People-centred care also requires that patients have the education and support they need to make

decisions and participate in their own care and that carers are able to attain maximal function within a supportive working environment. People-

centred care is broader than patient and person-centred care, encompassing not only clinical encounters, but also including attention to the health of

people in their communities and their crucial role in shaping health policy and health services.

12 Health Data Collaborative www.healthdatacollaborative.org

13 Primary Health Care Performance Initiative www.phcperformanceinitiative.org

emphasis and underinvestment. As a result, PHC implementation has lagged far behind its aspirational

objectives: continuing to focus on the delivery of a basic package of health interventions for selected priority

diseases rather than comprehensive care, ineffective decentralization that impedes PHC from responding to

local conditions, failing to focus on improved coordination between providers and levels of care, missing out

on the benefits of multidisciplinary care, limiting access hours of PHC facilities, and under-emphasising

health work force development and retention resulting in overworked and under-supported staff.

In most countries, little is known about the performance of PHC, particularly in service delivery domains

that are critical to its effectiveness but often not well measured: access7, comprehensiveness8, continuity9,

coordination10, people-centeredness11 (family and community orientation), and quality (both technical and

interpersonal). These domains characterize high-quality primary care (as first contact care) and help explain

performance variation across country contexts, in all settings from low- to high-income countries. While

there are numerous typologies of primary care, not all of them lead to desirable outcomes and impact.

Measuring these domains of high quality PHC acknowledges their importance in explaining performance

variation and can lead to critical reforms. Increased and improved measurement of PHC performance, with

measures relevant to community, facility, district and national processes, is needed to promote

accountability and guide improvement efforts at each level of the health system. There is tremendous

opportunity to have a major impact on health through targeted measurement of what drives strong primary

health care systems and better utilization of these data for improvement by stakeholders at all levels of the

health system.

Several recent collaborative efforts by international development agencies have drawn further attention

to this area including the Health Data Collaborative (HDC)12 and the Primary Health Care Performance

Initiative (PHCPI). 13 HDC seeks to facilitate and accelerate progress in strengthening country systems for

monitoring progress and performance for accountability and transparency within the context of the health

related SDGs. PHCPI brings together partners to improve PHC in low- and middle-income countries through

better measurement to inform and accelerate national and sub-national PHC progress and knowledge-

sharing.

As a key next step, this meeting serves to engage leadership of Member States, partner organizations,

international development associations, academic partners and WHO to move toward a common roadmap

for strengthened PHC measurement and improvement. Stakeholder input obtained through this meeting will

be used to shape the concrete steps needed to advance the measurement and improvement agenda,

including: (1) improved performance measurement (2) research and development for under-measured

domains (3) improved transparency and accountability (4) and evidence-informed decision making all

leading to (5) performance improvement.

7 Access: Available, affordable services in close proximity to people. Primary care serves as the entry point into the health care system and the

first and regular source of care for most health needs.

8 Comprehensiveness: Delivers a broad spectrum of preventive, promotive, curative and palliative care across the life-course

9 Continuity: Individuals have a relationship with same provider and team over time, health information is available over time, and health

management plans are continuous.

10 Coordination: Primary care offers a hub from which people are guided through the health system, managing care across levels, referring to

specialists as needed and effectively following-up to monitor health progress.

11People-centeredness: an approach to care that consciously adopts individuals’, carers’, families’ and communities’ perspectives as

participants in, and beneficiaries of, trusted health systems that are organized around the comprehensive needs of people rather than individual

diseases, and respects their preferences. People-centred care also requires that patients have the education and support they need to make

decisions and participate in their own care and that carers are able to attain maximal function within a supportive working environment. People-

centred care is broader than patient and person-centred care, encompassing not only clinical encounters, but also including attention to the health of

people in their communities and their crucial role in shaping health policy and health services.

12 Health Data Collaborative www.healthdatacollaborative.org

13 Primary Health Care Performance Initiative www.phcperformanceinitiative.org

| P a g e 9

Measurement

In order to improve primary health care performance, countries, districts, and facilities first need

information about how their systems are performing and what barriers are preventing them from delivering

high-quality, patient-centered primary care services. The last decade saw progress in many low- and middle-

income countries toward producing, using, and sharing health data; yet, most country health information

systems still do not meet current data demands.

In many countries data collection is not harmonized around the needs of planners and managers, but

rather numerous reporting tools to meet the stated objectives of multiple implementers and stakeholders.

This lack of coordination requires an enormous data collection effort from already overburdened human

resources. At times country HMIS efforts are siloed or lack interoperability, missing out on opportunities for

analysis of complex, crosscutting problems. Far too often, there are limited resources for HMIS reforms.

Even where coordinated, high-functioning systems exist, data quality assurance can remain challenging.

Traditionally, measures of PHC performance have focused on quantifying the inputs—human resources,

facilities, and financing, for example—and describing service delivery volume and outcomes, including

disease-specific morbidity and mortality. Measurement of quality service delivery has been largely

neglected, as has the experience of patients, health workers, and communities in seeking, accessing and

delivering health services. Most countries, districts, and facilities lack data on many of the core functions of

quality PHC (first contact accessibility, continuity, coordination, and comprehensiveness), patient-

centeredness and responsiveness, and primary care organization and management. This lack of data and

knowledge about which components of service delivery and organization need strengthening impedes the

ability of actors at all levels of the health system to take action for improvement.

Ideally, measurement of PHC functions and service delivery should be occurring in a coordinated way at

the community and facility, subnational and national levels. In such a system, actors at each level of the

system - national planners and policy makers, sub-national managers, and providers and communities -

would be able to access and use standardized and interoperable data collection platforms to track key

performance indicators to continually assess the quality and effectiveness of care delivered and proactively

plan for future service delivery needs as well as identify areas where change in existing systems and policies

are needed.

Data needs for these activities range from measurement of the local burden of disease to drug and

supply availability and from health worker performance and motivation to experiential quality and results of

care delivery. Subnational-level decision makers need access to this information from facilities in their

catchment area in order to track trends in performance and outcomes over time, quickly detect and act

upon emerging issues and gaps, and identify positive outliers to extract and spread promising practices. The

same is true at the national level, where timely information from districts is converted to knowledge to drive

action for improvement and used to inform future practices, policies and strategic planning. At the global

level, measurement informs global surveillance efforts, donor investment priorities, and international

policies. At all levels, measurement is a tool for enabling comparability, identifying promising practices for

sharing, and creating accountable and transparent systems that are responsive to the needs of their

constituents.

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

Given the expansive field of health systems measurement, an organizing framework for understanding

monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is critical. The IHP+ common M&E Framework (Figure 1) provides a results-

Measurement

In order to improve primary health care performance, countries, districts, and facilities first need

information about how their systems are performing and what barriers are preventing them from delivering

high-quality, patient-centered primary care services. The last decade saw progress in many low- and middle-

income countries toward producing, using, and sharing health data; yet, most country health information

systems still do not meet current data demands.

In many countries data collection is not harmonized around the needs of planners and managers, but

rather numerous reporting tools to meet the stated objectives of multiple implementers and stakeholders.

This lack of coordination requires an enormous data collection effort from already overburdened human

resources. At times country HMIS efforts are siloed or lack interoperability, missing out on opportunities for

analysis of complex, crosscutting problems. Far too often, there are limited resources for HMIS reforms.

Even where coordinated, high-functioning systems exist, data quality assurance can remain challenging.

Traditionally, measures of PHC performance have focused on quantifying the inputs—human resources,

facilities, and financing, for example—and describing service delivery volume and outcomes, including

disease-specific morbidity and mortality. Measurement of quality service delivery has been largely

neglected, as has the experience of patients, health workers, and communities in seeking, accessing and

delivering health services. Most countries, districts, and facilities lack data on many of the core functions of

quality PHC (first contact accessibility, continuity, coordination, and comprehensiveness), patient-

centeredness and responsiveness, and primary care organization and management. This lack of data and

knowledge about which components of service delivery and organization need strengthening impedes the

ability of actors at all levels of the health system to take action for improvement.

Ideally, measurement of PHC functions and service delivery should be occurring in a coordinated way at

the community and facility, subnational and national levels. In such a system, actors at each level of the

system - national planners and policy makers, sub-national managers, and providers and communities -

would be able to access and use standardized and interoperable data collection platforms to track key

performance indicators to continually assess the quality and effectiveness of care delivered and proactively

plan for future service delivery needs as well as identify areas where change in existing systems and policies

are needed.

Data needs for these activities range from measurement of the local burden of disease to drug and

supply availability and from health worker performance and motivation to experiential quality and results of

care delivery. Subnational-level decision makers need access to this information from facilities in their

catchment area in order to track trends in performance and outcomes over time, quickly detect and act

upon emerging issues and gaps, and identify positive outliers to extract and spread promising practices. The

same is true at the national level, where timely information from districts is converted to knowledge to drive

action for improvement and used to inform future practices, policies and strategic planning. At the global

level, measurement informs global surveillance efforts, donor investment priorities, and international

policies. At all levels, measurement is a tool for enabling comparability, identifying promising practices for

sharing, and creating accountable and transparent systems that are responsive to the needs of their

constituents.

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

Given the expansive field of health systems measurement, an organizing framework for understanding

monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is critical. The IHP+ common M&E Framework (Figure 1) provides a results-

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

| P a g e 10

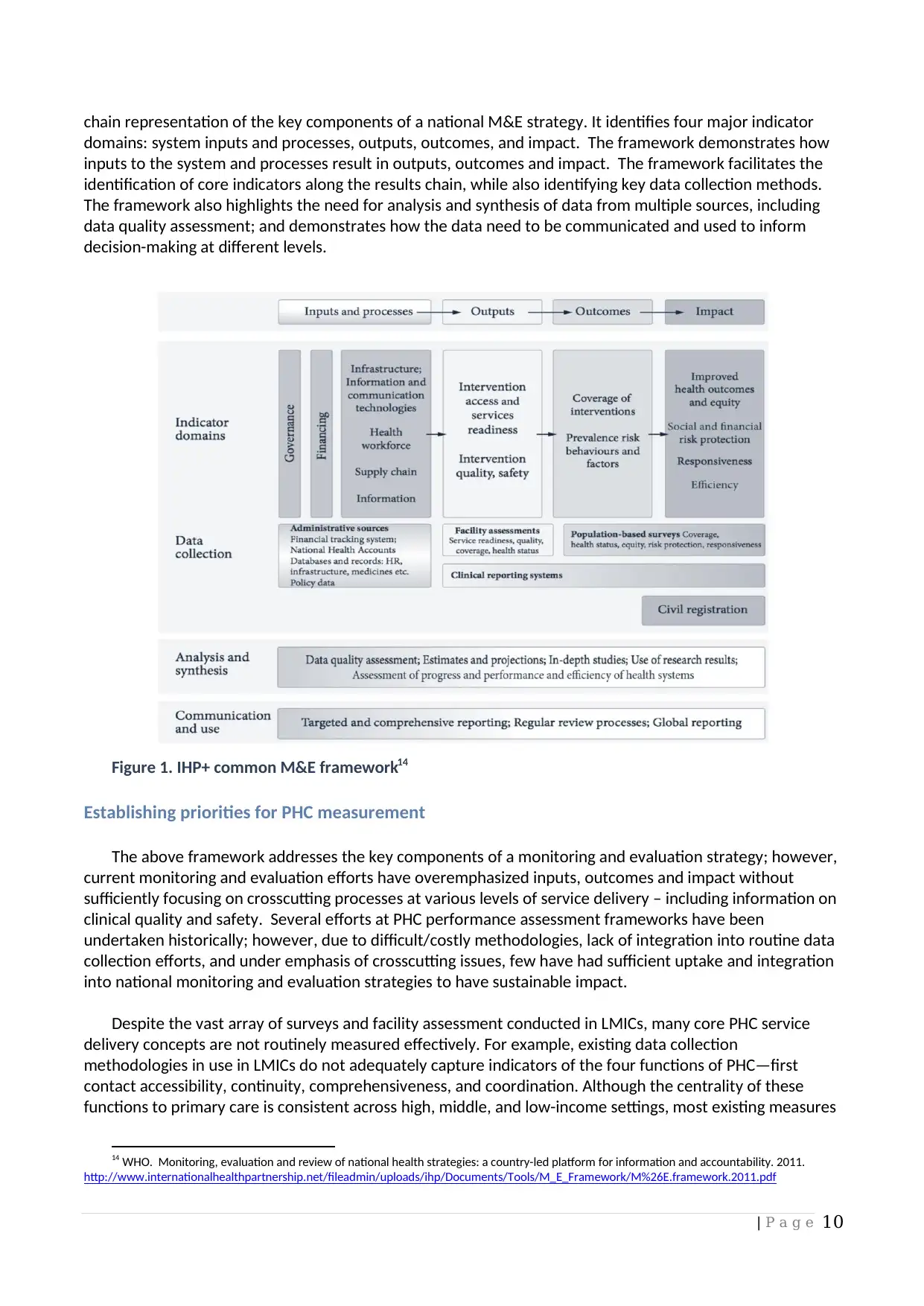

chain representation of the key components of a national M&E strategy. It identifies four major indicator

domains: system inputs and processes, outputs, outcomes, and impact. The framework demonstrates how

inputs to the system and processes result in outputs, outcomes and impact. The framework facilitates the

identification of core indicators along the results chain, while also identifying key data collection methods.

The framework also highlights the need for analysis and synthesis of data from multiple sources, including

data quality assessment; and demonstrates how the data need to be communicated and used to inform

decision-making at different levels.

Figure 1. IHP+ common M&E framework14

Establishing priorities for PHC measurement

The above framework addresses the key components of a monitoring and evaluation strategy; however,

current monitoring and evaluation efforts have overemphasized inputs, outcomes and impact without

sufficiently focusing on crosscutting processes at various levels of service delivery – including information on

clinical quality and safety. Several efforts at PHC performance assessment frameworks have been

undertaken historically; however, due to difficult/costly methodologies, lack of integration into routine data

collection efforts, and under emphasis of crosscutting issues, few have had sufficient uptake and integration

into national monitoring and evaluation strategies to have sustainable impact.

Despite the vast array of surveys and facility assessment conducted in LMICs, many core PHC service

delivery concepts are not routinely measured effectively. For example, existing data collection

methodologies in use in LMICs do not adequately capture indicators of the four functions of PHC—first

contact accessibility, continuity, comprehensiveness, and coordination. Although the centrality of these

functions to primary care is consistent across high, middle, and low-income settings, most existing measures

14 WHO. Monitoring, evaluation and review of national health strategies: a country-led platform for information and accountability. 2011.

http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/fileadmin/uploads/ihp/Documents/Tools/M_E_Framework/M%26E.framework.2011.pdf

chain representation of the key components of a national M&E strategy. It identifies four major indicator

domains: system inputs and processes, outputs, outcomes, and impact. The framework demonstrates how

inputs to the system and processes result in outputs, outcomes and impact. The framework facilitates the

identification of core indicators along the results chain, while also identifying key data collection methods.

The framework also highlights the need for analysis and synthesis of data from multiple sources, including

data quality assessment; and demonstrates how the data need to be communicated and used to inform

decision-making at different levels.

Figure 1. IHP+ common M&E framework14

Establishing priorities for PHC measurement

The above framework addresses the key components of a monitoring and evaluation strategy; however,

current monitoring and evaluation efforts have overemphasized inputs, outcomes and impact without

sufficiently focusing on crosscutting processes at various levels of service delivery – including information on

clinical quality and safety. Several efforts at PHC performance assessment frameworks have been

undertaken historically; however, due to difficult/costly methodologies, lack of integration into routine data

collection efforts, and under emphasis of crosscutting issues, few have had sufficient uptake and integration

into national monitoring and evaluation strategies to have sustainable impact.

Despite the vast array of surveys and facility assessment conducted in LMICs, many core PHC service

delivery concepts are not routinely measured effectively. For example, existing data collection

methodologies in use in LMICs do not adequately capture indicators of the four functions of PHC—first

contact accessibility, continuity, comprehensiveness, and coordination. Although the centrality of these

functions to primary care is consistent across high, middle, and low-income settings, most existing measures

14 WHO. Monitoring, evaluation and review of national health strategies: a country-led platform for information and accountability. 2011.

http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/fileadmin/uploads/ihp/Documents/Tools/M_E_Framework/M%26E.framework.2011.pdf

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

| P a g e 11

are currently validated and used in only high-income countries. Expert consensus is that these measures are

not applicable to most LMICs, particularly fragile states. This leads to the paradoxical situation of many low

and middle-income countries in which countries are overwhelmed by data and reporting requirements, but

lack critical data for decision-making and improvement efforts.

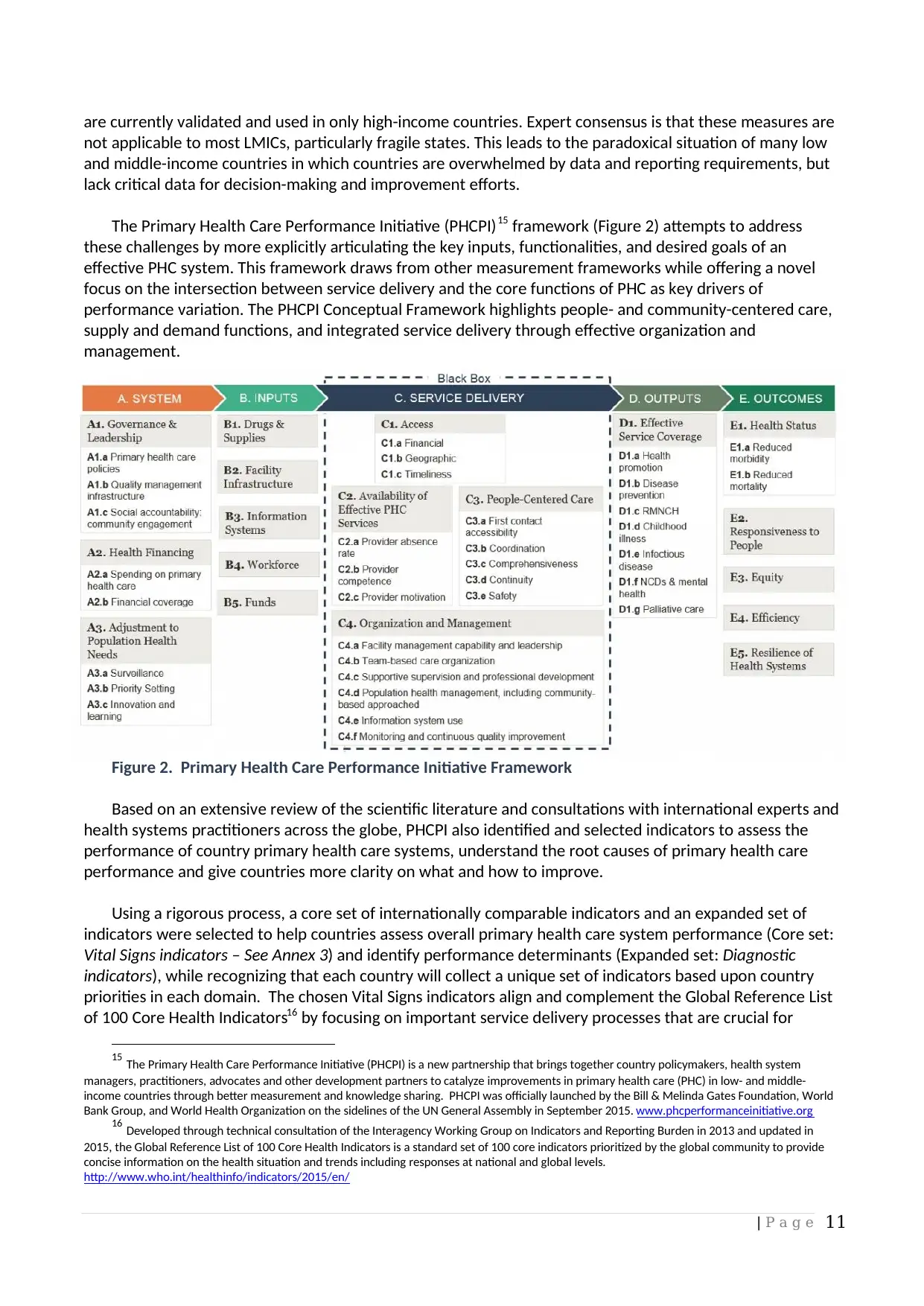

The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) 15 framework (Figure 2) attempts to address

these challenges by more explicitly articulating the key inputs, functionalities, and desired goals of an

effective PHC system. This framework draws from other measurement frameworks while offering a novel

focus on the intersection between service delivery and the core functions of PHC as key drivers of

performance variation. The PHCPI Conceptual Framework highlights people- and community-centered care,

supply and demand functions, and integrated service delivery through effective organization and

management.

Figure 2. Primary Health Care Performance Initiative Framework

Based on an extensive review of the scientific literature and consultations with international experts and

health systems practitioners across the globe, PHCPI also identified and selected indicators to assess the

performance of country primary health care systems, understand the root causes of primary health care

performance and give countries more clarity on what and how to improve.

Using a rigorous process, a core set of internationally comparable indicators and an expanded set of

indicators were selected to help countries assess overall primary health care system performance (Core set:

Vital Signs indicators – See Annex 3) and identify performance determinants (Expanded set: Diagnostic

indicators), while recognizing that each country will collect a unique set of indicators based upon country

priorities in each domain. The chosen Vital Signs indicators align and complement the Global Reference List

of 100 Core Health Indicators16 by focusing on important service delivery processes that are crucial for

15 The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) is a new partnership that brings together country policymakers, health system

managers, practitioners, advocates and other development partners to catalyze improvements in primary health care (PHC) in low- and middle-

income countries through better measurement and knowledge sharing. PHCPI was officially launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, World

Bank Group, and World Health Organization on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in September 2015. www.phcperformanceinitiative.org

16 Developed through technical consultation of the Interagency Working Group on Indicators and Reporting Burden in 2013 and updated in

2015, the Global Reference List of 100 Core Health Indicators is a standard set of 100 core indicators prioritized by the global community to provide

concise information on the health situation and trends including responses at national and global levels.

http://www.who.int/healthinfo/indicators/2015/en/

are currently validated and used in only high-income countries. Expert consensus is that these measures are

not applicable to most LMICs, particularly fragile states. This leads to the paradoxical situation of many low

and middle-income countries in which countries are overwhelmed by data and reporting requirements, but

lack critical data for decision-making and improvement efforts.

The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) 15 framework (Figure 2) attempts to address

these challenges by more explicitly articulating the key inputs, functionalities, and desired goals of an

effective PHC system. This framework draws from other measurement frameworks while offering a novel

focus on the intersection between service delivery and the core functions of PHC as key drivers of

performance variation. The PHCPI Conceptual Framework highlights people- and community-centered care,

supply and demand functions, and integrated service delivery through effective organization and

management.

Figure 2. Primary Health Care Performance Initiative Framework

Based on an extensive review of the scientific literature and consultations with international experts and

health systems practitioners across the globe, PHCPI also identified and selected indicators to assess the

performance of country primary health care systems, understand the root causes of primary health care

performance and give countries more clarity on what and how to improve.

Using a rigorous process, a core set of internationally comparable indicators and an expanded set of

indicators were selected to help countries assess overall primary health care system performance (Core set:

Vital Signs indicators – See Annex 3) and identify performance determinants (Expanded set: Diagnostic

indicators), while recognizing that each country will collect a unique set of indicators based upon country

priorities in each domain. The chosen Vital Signs indicators align and complement the Global Reference List

of 100 Core Health Indicators16 by focusing on important service delivery processes that are crucial for

15 The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) is a new partnership that brings together country policymakers, health system

managers, practitioners, advocates and other development partners to catalyze improvements in primary health care (PHC) in low- and middle-

income countries through better measurement and knowledge sharing. PHCPI was officially launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, World

Bank Group, and World Health Organization on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in September 2015. www.phcperformanceinitiative.org

16 Developed through technical consultation of the Interagency Working Group on Indicators and Reporting Burden in 2013 and updated in

2015, the Global Reference List of 100 Core Health Indicators is a standard set of 100 core indicators prioritized by the global community to provide

concise information on the health situation and trends including responses at national and global levels.

http://www.who.int/healthinfo/indicators/2015/en/

| P a g e 12

achieving universal health coverage and other global priorities. Diagnostic indicators, which provide more

detailed information to identify performance gaps are, by nature, less internationally comparable, and will

need to be tailored to country context and health management information system (HMIS) capacities.

Currently available information on LMIC performance related to the Vital Signs can be found on the PHCPI

website at www.phcperformanceintiative.org.

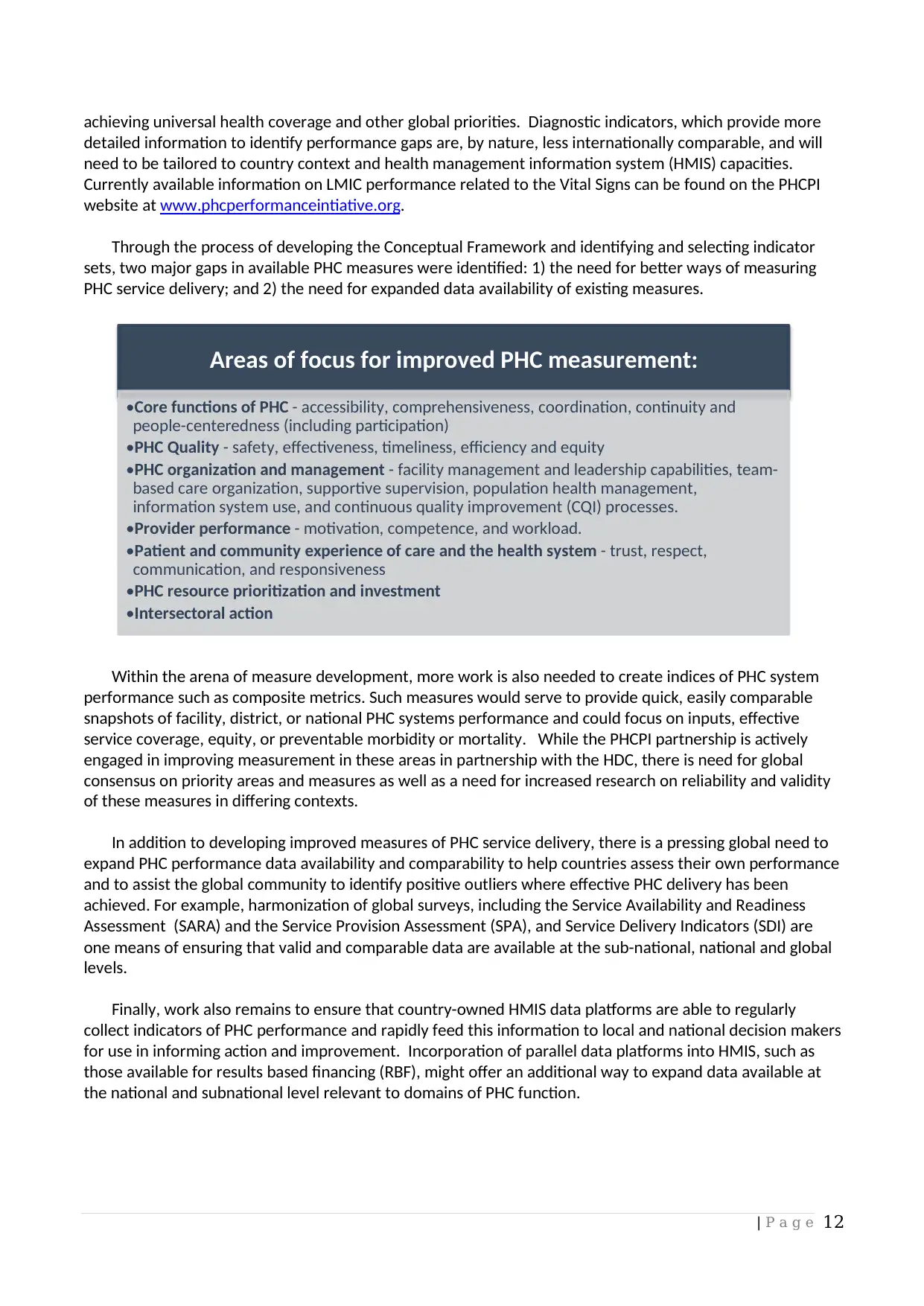

Through the process of developing the Conceptual Framework and identifying and selecting indicator

sets, two major gaps in available PHC measures were identified: 1) the need for better ways of measuring

PHC service delivery; and 2) the need for expanded data availability of existing measures.

Within the arena of measure development, more work is also needed to create indices of PHC system

performance such as composite metrics. Such measures would serve to provide quick, easily comparable

snapshots of facility, district, or national PHC systems performance and could focus on inputs, effective

service coverage, equity, or preventable morbidity or mortality. While the PHCPI partnership is actively

engaged in improving measurement in these areas in partnership with the HDC, there is need for global

consensus on priority areas and measures as well as a need for increased research on reliability and validity

of these measures in differing contexts.

In addition to developing improved measures of PHC service delivery, there is a pressing global need to

expand PHC performance data availability and comparability to help countries assess their own performance

and to assist the global community to identify positive outliers where effective PHC delivery has been

achieved. For example, harmonization of global surveys, including the Service Availability and Readiness

Assessment (SARA) and the Service Provision Assessment (SPA), and Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) are

one means of ensuring that valid and comparable data are available at the sub-national, national and global

levels.

Finally, work also remains to ensure that country-owned HMIS data platforms are able to regularly

collect indicators of PHC performance and rapidly feed this information to local and national decision makers

for use in informing action and improvement. Incorporation of parallel data platforms into HMIS, such as

those available for results based financing (RBF), might offer an additional way to expand data available at

the national and subnational level relevant to domains of PHC function.

Areas of focus for improved PHC measurement:

•Core functions of PHC - accessibility, comprehensiveness, coordination, continuity and

people-centeredness (including participation)

•PHC Quality - safety, effectiveness, timeliness, efficiency and equity

•PHC organization and management - facility management and leadership capabilities, team-

based care organization, supportive supervision, population health management,

information system use, and continuous quality improvement (CQI) processes.

•Provider performance - motivation, competence, and workload.

•Patient and community experience of care and the health system - trust, respect,

communication, and responsiveness

•PHC resource prioritization and investment

•Intersectoral action

achieving universal health coverage and other global priorities. Diagnostic indicators, which provide more

detailed information to identify performance gaps are, by nature, less internationally comparable, and will

need to be tailored to country context and health management information system (HMIS) capacities.

Currently available information on LMIC performance related to the Vital Signs can be found on the PHCPI

website at www.phcperformanceintiative.org.

Through the process of developing the Conceptual Framework and identifying and selecting indicator

sets, two major gaps in available PHC measures were identified: 1) the need for better ways of measuring

PHC service delivery; and 2) the need for expanded data availability of existing measures.

Within the arena of measure development, more work is also needed to create indices of PHC system

performance such as composite metrics. Such measures would serve to provide quick, easily comparable

snapshots of facility, district, or national PHC systems performance and could focus on inputs, effective

service coverage, equity, or preventable morbidity or mortality. While the PHCPI partnership is actively

engaged in improving measurement in these areas in partnership with the HDC, there is need for global

consensus on priority areas and measures as well as a need for increased research on reliability and validity

of these measures in differing contexts.

In addition to developing improved measures of PHC service delivery, there is a pressing global need to

expand PHC performance data availability and comparability to help countries assess their own performance

and to assist the global community to identify positive outliers where effective PHC delivery has been

achieved. For example, harmonization of global surveys, including the Service Availability and Readiness

Assessment (SARA) and the Service Provision Assessment (SPA), and Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) are

one means of ensuring that valid and comparable data are available at the sub-national, national and global

levels.

Finally, work also remains to ensure that country-owned HMIS data platforms are able to regularly

collect indicators of PHC performance and rapidly feed this information to local and national decision makers

for use in informing action and improvement. Incorporation of parallel data platforms into HMIS, such as

those available for results based financing (RBF), might offer an additional way to expand data available at

the national and subnational level relevant to domains of PHC function.

Areas of focus for improved PHC measurement:

•Core functions of PHC - accessibility, comprehensiveness, coordination, continuity and

people-centeredness (including participation)

•PHC Quality - safety, effectiveness, timeliness, efficiency and equity

•PHC organization and management - facility management and leadership capabilities, team-

based care organization, supportive supervision, population health management,

information system use, and continuous quality improvement (CQI) processes.

•Provider performance - motivation, competence, and workload.

•Patient and community experience of care and the health system - trust, respect,

communication, and responsiveness

•PHC resource prioritization and investment

•Intersectoral action

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 25

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.