Program Development Intelligence Report: Food Nutrition in Australia

VerifiedAdded on 2020/03/16

|19

|5154

|27

Report

AI Summary

This Program Development Intelligence Report investigates the concerning issue of high sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption among Australian children, particularly within the indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. The report highlights the significant health risks associated with SSB intake, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, dental caries, and cardiovascular diseases. It examines the extent of SSB consumption, analyzes individual and socio-environmental determinants, and considers stakeholder perspectives to understand the factors contributing to the problem. The report emphasizes the need for interventions involving government and non-government organizations to reduce SSB consumption and mitigate the adverse health outcomes faced by these vulnerable populations. The findings underscore the importance of addressing this issue to ensure a healthier future for Australian children.

Running head: PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

TOPIC: FOOD NUTRITION

TITLE: PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Name of the student:

Student ID:

No. of pages: 18

TOPIC: FOOD NUTRITION

TITLE: PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Name of the student:

Student ID:

No. of pages: 18

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Executive Summary

Australian children, particularly the indigenous Aboriginal children show high consumption of

high sugar beverages. They are found to be highly obese and have the risk of developing serious

health concerns in the future like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, kidney failure among others.

Fifty six percent of the children of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait were found to consume SSBs.

Various factors were found to be responsible for the increased consumption of SSBs among the

indigenous Australians. These included their socio-environmental backgrounds, socio-economic

backgrounds, education, unemployment, preferences, and availability and modelling systems.

Interventions are needed to be carried out with the help of the government and non-government

organizations in order to reduce SSB consumption.

Executive Summary

Australian children, particularly the indigenous Aboriginal children show high consumption of

high sugar beverages. They are found to be highly obese and have the risk of developing serious

health concerns in the future like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, kidney failure among others.

Fifty six percent of the children of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait were found to consume SSBs.

Various factors were found to be responsible for the increased consumption of SSBs among the

indigenous Australians. These included their socio-environmental backgrounds, socio-economic

backgrounds, education, unemployment, preferences, and availability and modelling systems.

Interventions are needed to be carried out with the help of the government and non-government

organizations in order to reduce SSB consumption.

2PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Table of Contents

Introduction....................................................................................................................................3

Program development intelligence report...................................................................................4

1. Magnitude and significance of the problem generally to children’s health..........................4

1.1. Health risks....................................................................................................................4

1.2. Extent of SSB consumption..........................................................................................5

1.3. Synthesis of the data......................................................................................................7

1.4. Summary and Conclusion.............................................................................................7

2. Analysis of the problem from an individual and socio-environmental perspective.............8

2.1. Individual determinants.................................................................................................8

2.2. Socio-environmental determinants................................................................................8

3. Consideration of stakeholder perspectives.........................................................................10

3.1. Stakeholders and partners............................................................................................10

3.2. Relationship to the problem and potential interventions.............................................11

3.3. Questions asked to stakeholders..................................................................................12

3.4. Primary healthcare service..........................................................................................12

Conclusion....................................................................................................................................13

Reference List...............................................................................................................................15

Table of Contents

Introduction....................................................................................................................................3

Program development intelligence report...................................................................................4

1. Magnitude and significance of the problem generally to children’s health..........................4

1.1. Health risks....................................................................................................................4

1.2. Extent of SSB consumption..........................................................................................5

1.3. Synthesis of the data......................................................................................................7

1.4. Summary and Conclusion.............................................................................................7

2. Analysis of the problem from an individual and socio-environmental perspective.............8

2.1. Individual determinants.................................................................................................8

2.2. Socio-environmental determinants................................................................................8

3. Consideration of stakeholder perspectives.........................................................................10

3.1. Stakeholders and partners............................................................................................10

3.2. Relationship to the problem and potential interventions.............................................11

3.3. Questions asked to stakeholders..................................................................................12

3.4. Primary healthcare service..........................................................................................12

Conclusion....................................................................................................................................13

Reference List...............................................................................................................................15

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Introduction

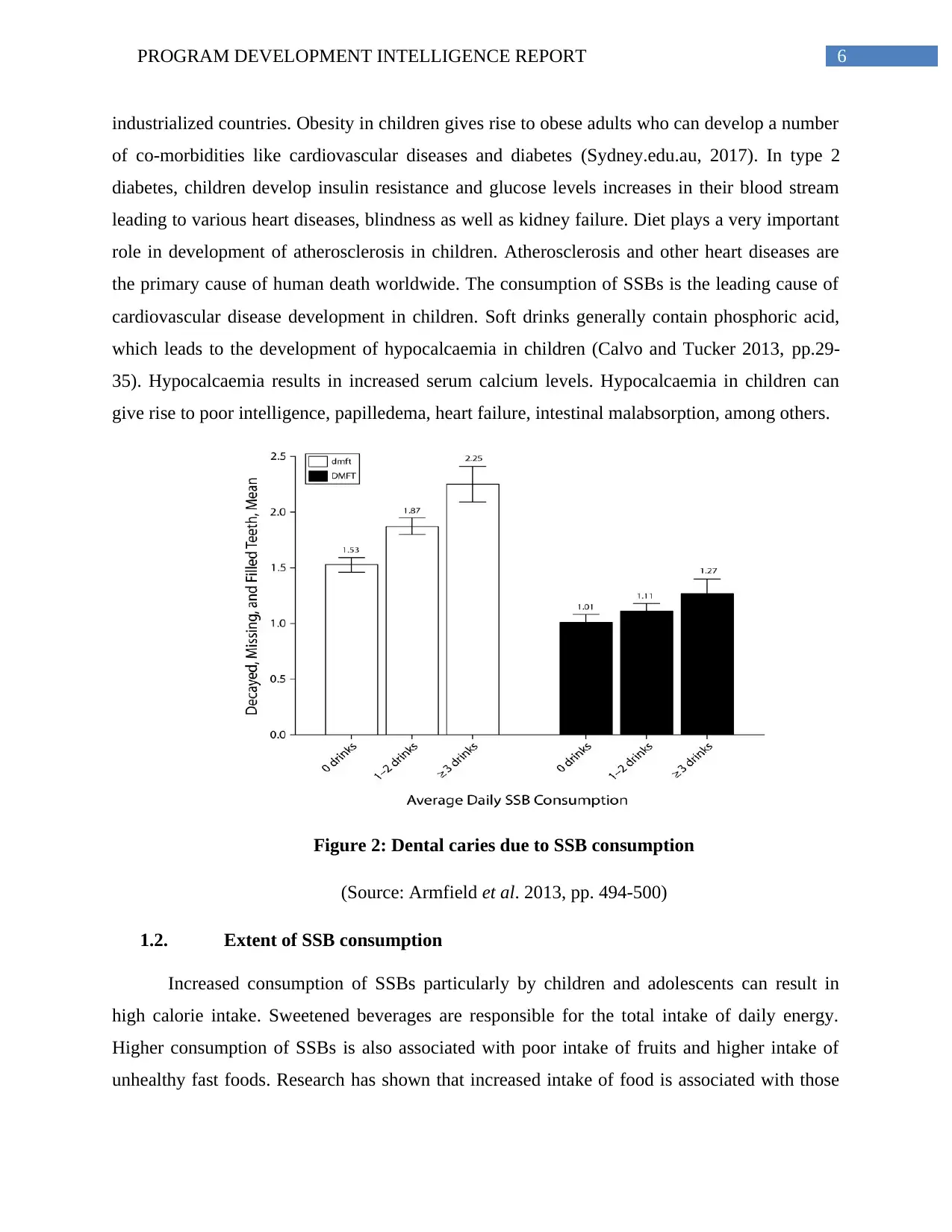

Sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) is linked to obesity in children. SSBs include

sweetened soft drinks, fruit juices with added sugars, sweetened tea, coffee, sodas, among others.

Consumption of SSBs has increased in children, adolescents and adults as well. These are

associated with dental caries, obesity and other medical conditions. SSB consumption is

associated with a high body mass index (BMI) and increased deposition of fat. Daily

consumption of SSBs can give rise to approximately 6.5 kg of weight gain in individuals in a

year. Australia is one of the top countries in the consumption of sugary drinks and majority of

the consumers are children (Vichealth.vic.gov.au, 2017).

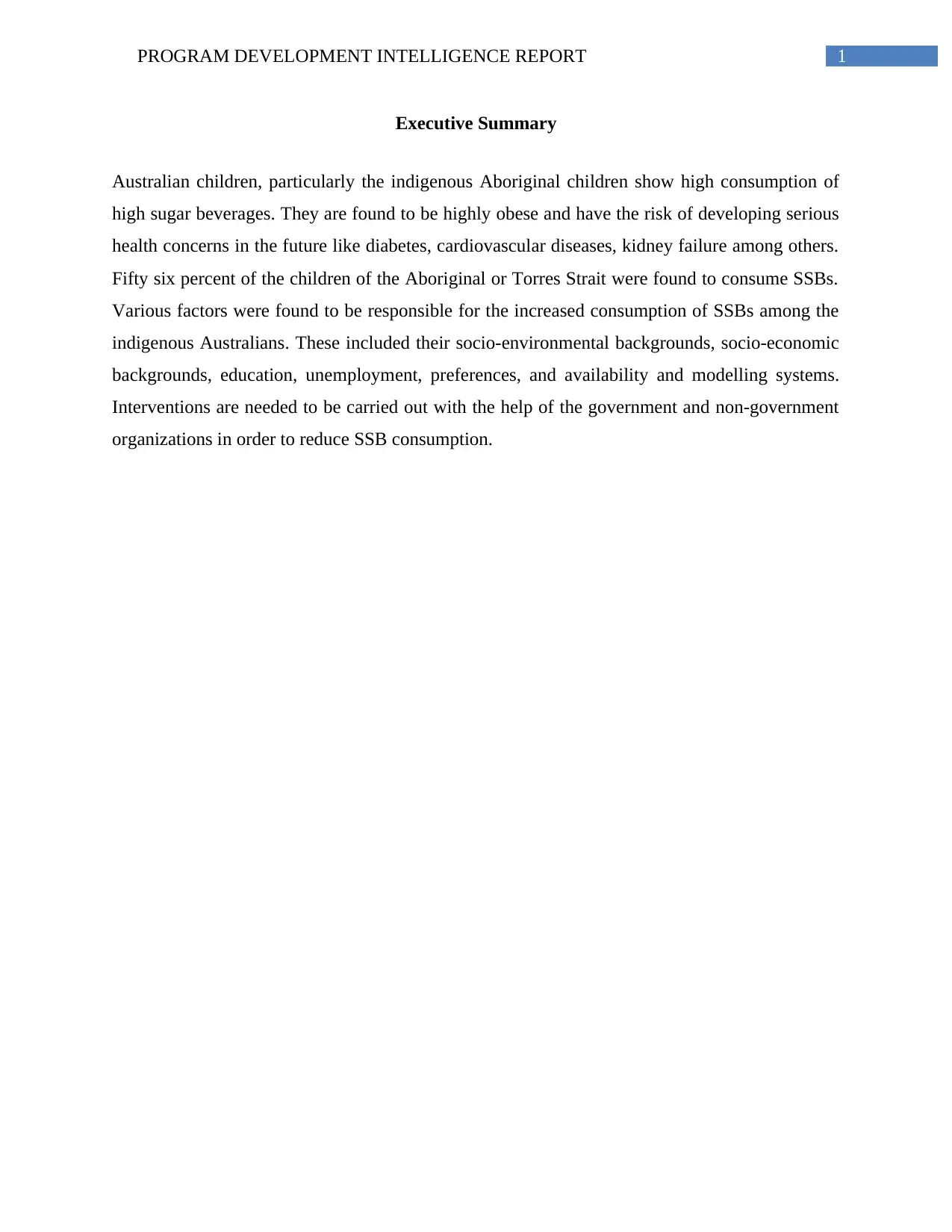

This report focuses on understanding the ill effects of SSB consumption in the Australian

children particularly the indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait island children. Consumption of

SSBs results in obesity, diabetes, hypocalcaemia (increased levels of serum calcium), decreased

bone mineral density, dental caries, kidney stones, increase in the systolic and diastolic blood

pressure, among others. Type 2 diabetes is the prevalent form of diabetes among the children

consuming large amounts of SSBs (Rethinksugarydrink.org.au, 2017). In Australia, intake of

sweetened beverages were high among teenagers aged between 14-18 years, but on the average,

children aged between 2-18 years of age showed higher consumption than adults. About 50% of

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island children aged from 2 years drank high amounts of SSBs

compared to the non-indigenous people (Laws et al. 2014, p.779).

Figure 1: Graphical representation of BMI

Introduction

Sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) is linked to obesity in children. SSBs include

sweetened soft drinks, fruit juices with added sugars, sweetened tea, coffee, sodas, among others.

Consumption of SSBs has increased in children, adolescents and adults as well. These are

associated with dental caries, obesity and other medical conditions. SSB consumption is

associated with a high body mass index (BMI) and increased deposition of fat. Daily

consumption of SSBs can give rise to approximately 6.5 kg of weight gain in individuals in a

year. Australia is one of the top countries in the consumption of sugary drinks and majority of

the consumers are children (Vichealth.vic.gov.au, 2017).

This report focuses on understanding the ill effects of SSB consumption in the Australian

children particularly the indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait island children. Consumption of

SSBs results in obesity, diabetes, hypocalcaemia (increased levels of serum calcium), decreased

bone mineral density, dental caries, kidney stones, increase in the systolic and diastolic blood

pressure, among others. Type 2 diabetes is the prevalent form of diabetes among the children

consuming large amounts of SSBs (Rethinksugarydrink.org.au, 2017). In Australia, intake of

sweetened beverages were high among teenagers aged between 14-18 years, but on the average,

children aged between 2-18 years of age showed higher consumption than adults. About 50% of

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island children aged from 2 years drank high amounts of SSBs

compared to the non-indigenous people (Laws et al. 2014, p.779).

Figure 1: Graphical representation of BMI

5PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

(Source: Pmc.gov.au, 2017)

This report at first focuses on the SSB consumption and the health risks associated with it.

This report specifically focuses on SSB consumption of the indigenous children of Australia. The

second part of the report deals with program planning and evaluation.

Program development intelligence report

1. Magnitude and significance of the problem generally to children’s health

1.1. Health risks

Increase in sugar availability has resulted in increased sugar intakes in the form of

various sweetened drinks. These SSBs include a variety of drinks like sodas, energy drinks,

sweetened fruit juices, soft drinks, sweetened tea, and coffee, among others (Scharf and DeBoer

2016, pp.273-293). Popularity of SSBs has increased among children, adolescents and adults.

Various health risks can arise due to consumption of SSBs. The most significant health risk

being obesity. Among 10 million Australians who are overweight or obese, 47% were found to

consume large amounts of SSBs. About 56% of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island children

aged about 2 years were found to consume SSBs (Abs.gov.au, 2017). Total intake of sugars,

starches, carbohydrates, fats, fibre and sodium were higher for the aboriginal children than the

non-indigenous children. Other health risks include, high body mass index, increased

hypocalcaemia, loss of bone mineral density, dental caries, kidney stones, and increase in

systolic and diastolic blood pressure. High BMI and higher deposition of fat was found

compared to the non-drinkers. Moreover, children also showed increase in the incidence of

dental caries. Hypocalcaemia or increase in the level of calcium in the serum was also evident.

Increase in SSB consumption among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children causes an

increased risk of developing heart diseases and type 2 diabetes (Brimblecombe et al. 2013,

pp.380-384).

Intake of large amounts of beverages or foods containing added sugars increases the total

energy consumption and subsequently results in dilution of the total nutrient intake. In recent

years, the occurrence of obesity among young children has increased particularly in the

(Source: Pmc.gov.au, 2017)

This report at first focuses on the SSB consumption and the health risks associated with it.

This report specifically focuses on SSB consumption of the indigenous children of Australia. The

second part of the report deals with program planning and evaluation.

Program development intelligence report

1. Magnitude and significance of the problem generally to children’s health

1.1. Health risks

Increase in sugar availability has resulted in increased sugar intakes in the form of

various sweetened drinks. These SSBs include a variety of drinks like sodas, energy drinks,

sweetened fruit juices, soft drinks, sweetened tea, and coffee, among others (Scharf and DeBoer

2016, pp.273-293). Popularity of SSBs has increased among children, adolescents and adults.

Various health risks can arise due to consumption of SSBs. The most significant health risk

being obesity. Among 10 million Australians who are overweight or obese, 47% were found to

consume large amounts of SSBs. About 56% of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island children

aged about 2 years were found to consume SSBs (Abs.gov.au, 2017). Total intake of sugars,

starches, carbohydrates, fats, fibre and sodium were higher for the aboriginal children than the

non-indigenous children. Other health risks include, high body mass index, increased

hypocalcaemia, loss of bone mineral density, dental caries, kidney stones, and increase in

systolic and diastolic blood pressure. High BMI and higher deposition of fat was found

compared to the non-drinkers. Moreover, children also showed increase in the incidence of

dental caries. Hypocalcaemia or increase in the level of calcium in the serum was also evident.

Increase in SSB consumption among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children causes an

increased risk of developing heart diseases and type 2 diabetes (Brimblecombe et al. 2013,

pp.380-384).

Intake of large amounts of beverages or foods containing added sugars increases the total

energy consumption and subsequently results in dilution of the total nutrient intake. In recent

years, the occurrence of obesity among young children has increased particularly in the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

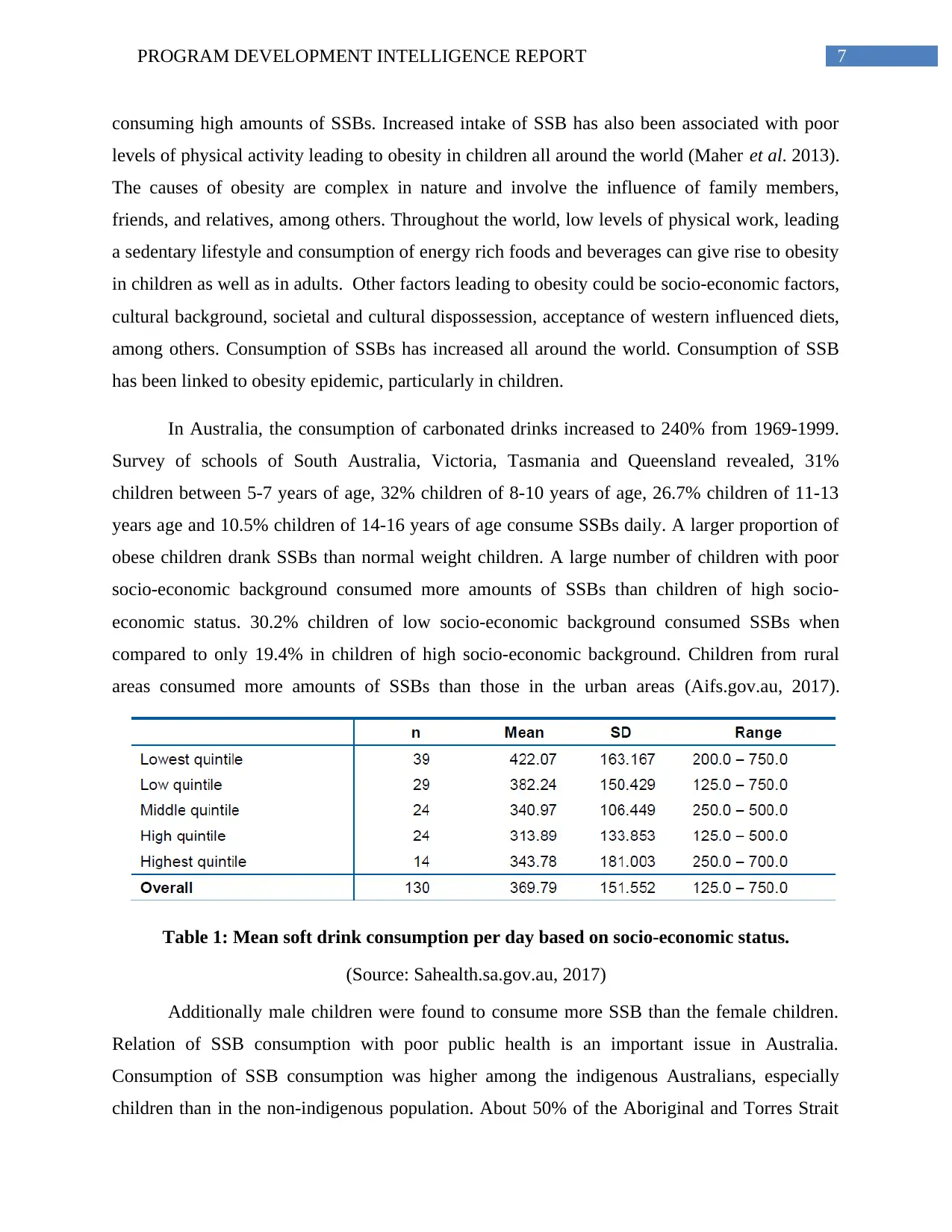

industrialized countries. Obesity in children gives rise to obese adults who can develop a number

of co-morbidities like cardiovascular diseases and diabetes (Sydney.edu.au, 2017). In type 2

diabetes, children develop insulin resistance and glucose levels increases in their blood stream

leading to various heart diseases, blindness as well as kidney failure. Diet plays a very important

role in development of atherosclerosis in children. Atherosclerosis and other heart diseases are

the primary cause of human death worldwide. The consumption of SSBs is the leading cause of

cardiovascular disease development in children. Soft drinks generally contain phosphoric acid,

which leads to the development of hypocalcaemia in children (Calvo and Tucker 2013, pp.29-

35). Hypocalcaemia results in increased serum calcium levels. Hypocalcaemia in children can

give rise to poor intelligence, papilledema, heart failure, intestinal malabsorption, among others.

Figure 2: Dental caries due to SSB consumption

(Source: Armfield et al. 2013, pp. 494-500)

1.2. Extent of SSB consumption

Increased consumption of SSBs particularly by children and adolescents can result in

high calorie intake. Sweetened beverages are responsible for the total intake of daily energy.

Higher consumption of SSBs is also associated with poor intake of fruits and higher intake of

unhealthy fast foods. Research has shown that increased intake of food is associated with those

industrialized countries. Obesity in children gives rise to obese adults who can develop a number

of co-morbidities like cardiovascular diseases and diabetes (Sydney.edu.au, 2017). In type 2

diabetes, children develop insulin resistance and glucose levels increases in their blood stream

leading to various heart diseases, blindness as well as kidney failure. Diet plays a very important

role in development of atherosclerosis in children. Atherosclerosis and other heart diseases are

the primary cause of human death worldwide. The consumption of SSBs is the leading cause of

cardiovascular disease development in children. Soft drinks generally contain phosphoric acid,

which leads to the development of hypocalcaemia in children (Calvo and Tucker 2013, pp.29-

35). Hypocalcaemia results in increased serum calcium levels. Hypocalcaemia in children can

give rise to poor intelligence, papilledema, heart failure, intestinal malabsorption, among others.

Figure 2: Dental caries due to SSB consumption

(Source: Armfield et al. 2013, pp. 494-500)

1.2. Extent of SSB consumption

Increased consumption of SSBs particularly by children and adolescents can result in

high calorie intake. Sweetened beverages are responsible for the total intake of daily energy.

Higher consumption of SSBs is also associated with poor intake of fruits and higher intake of

unhealthy fast foods. Research has shown that increased intake of food is associated with those

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

consuming high amounts of SSBs. Increased intake of SSB has also been associated with poor

levels of physical activity leading to obesity in children all around the world (Maher et al. 2013).

The causes of obesity are complex in nature and involve the influence of family members,

friends, and relatives, among others. Throughout the world, low levels of physical work, leading

a sedentary lifestyle and consumption of energy rich foods and beverages can give rise to obesity

in children as well as in adults. Other factors leading to obesity could be socio-economic factors,

cultural background, societal and cultural dispossession, acceptance of western influenced diets,

among others. Consumption of SSBs has increased all around the world. Consumption of SSB

has been linked to obesity epidemic, particularly in children.

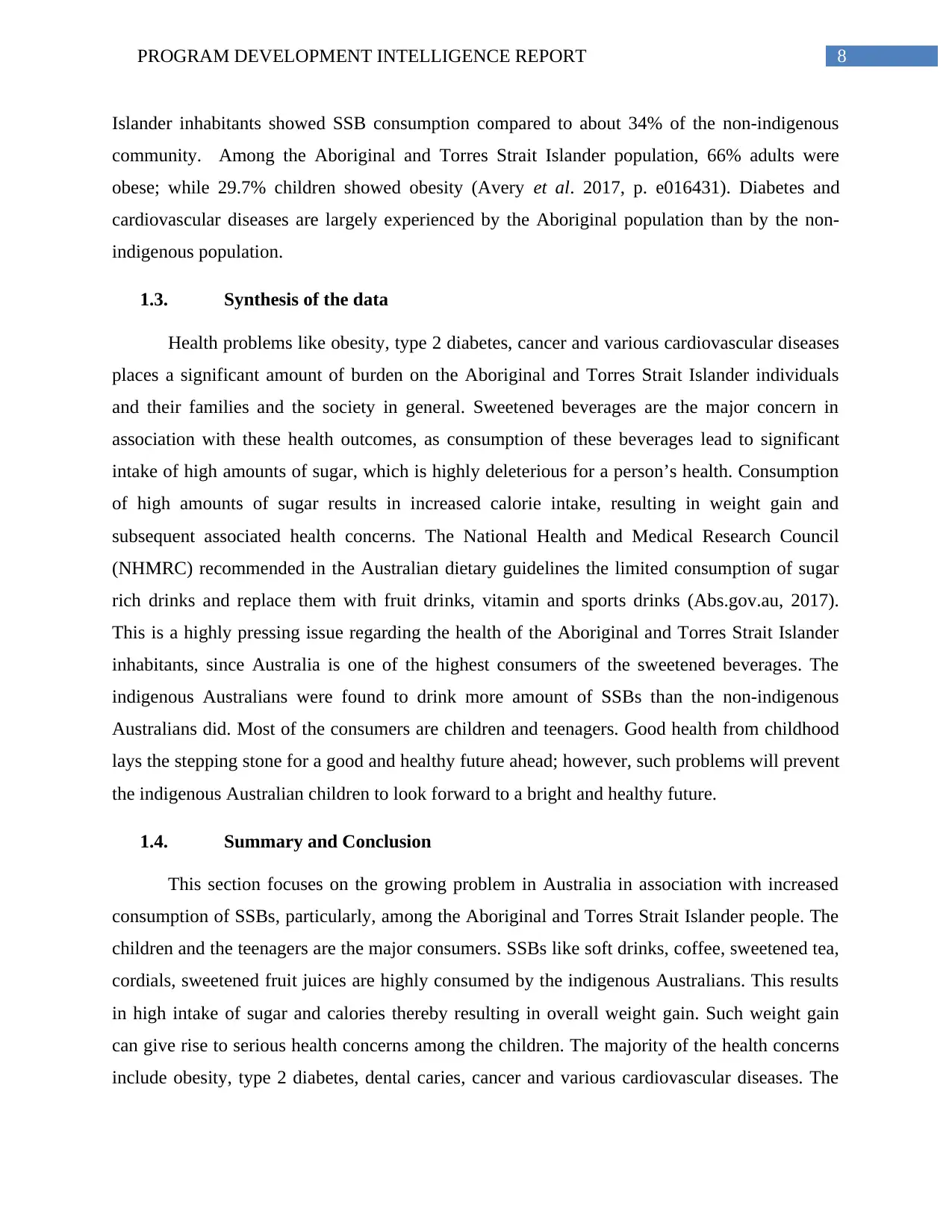

In Australia, the consumption of carbonated drinks increased to 240% from 1969-1999.

Survey of schools of South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania and Queensland revealed, 31%

children between 5-7 years of age, 32% children of 8-10 years of age, 26.7% children of 11-13

years age and 10.5% children of 14-16 years of age consume SSBs daily. A larger proportion of

obese children drank SSBs than normal weight children. A large number of children with poor

socio-economic background consumed more amounts of SSBs than children of high socio-

economic status. 30.2% children of low socio-economic background consumed SSBs when

compared to only 19.4% in children of high socio-economic background. Children from rural

areas consumed more amounts of SSBs than those in the urban areas (Aifs.gov.au, 2017).

Table 1: Mean soft drink consumption per day based on socio-economic status.

(Source: Sahealth.sa.gov.au, 2017)

Additionally male children were found to consume more SSB than the female children.

Relation of SSB consumption with poor public health is an important issue in Australia.

Consumption of SSB consumption was higher among the indigenous Australians, especially

children than in the non-indigenous population. About 50% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait

consuming high amounts of SSBs. Increased intake of SSB has also been associated with poor

levels of physical activity leading to obesity in children all around the world (Maher et al. 2013).

The causes of obesity are complex in nature and involve the influence of family members,

friends, and relatives, among others. Throughout the world, low levels of physical work, leading

a sedentary lifestyle and consumption of energy rich foods and beverages can give rise to obesity

in children as well as in adults. Other factors leading to obesity could be socio-economic factors,

cultural background, societal and cultural dispossession, acceptance of western influenced diets,

among others. Consumption of SSBs has increased all around the world. Consumption of SSB

has been linked to obesity epidemic, particularly in children.

In Australia, the consumption of carbonated drinks increased to 240% from 1969-1999.

Survey of schools of South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania and Queensland revealed, 31%

children between 5-7 years of age, 32% children of 8-10 years of age, 26.7% children of 11-13

years age and 10.5% children of 14-16 years of age consume SSBs daily. A larger proportion of

obese children drank SSBs than normal weight children. A large number of children with poor

socio-economic background consumed more amounts of SSBs than children of high socio-

economic status. 30.2% children of low socio-economic background consumed SSBs when

compared to only 19.4% in children of high socio-economic background. Children from rural

areas consumed more amounts of SSBs than those in the urban areas (Aifs.gov.au, 2017).

Table 1: Mean soft drink consumption per day based on socio-economic status.

(Source: Sahealth.sa.gov.au, 2017)

Additionally male children were found to consume more SSB than the female children.

Relation of SSB consumption with poor public health is an important issue in Australia.

Consumption of SSB consumption was higher among the indigenous Australians, especially

children than in the non-indigenous population. About 50% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait

8PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Islander inhabitants showed SSB consumption compared to about 34% of the non-indigenous

community. Among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, 66% adults were

obese; while 29.7% children showed obesity (Avery et al. 2017, p. e016431). Diabetes and

cardiovascular diseases are largely experienced by the Aboriginal population than by the non-

indigenous population.

1.3. Synthesis of the data

Health problems like obesity, type 2 diabetes, cancer and various cardiovascular diseases

places a significant amount of burden on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals

and their families and the society in general. Sweetened beverages are the major concern in

association with these health outcomes, as consumption of these beverages lead to significant

intake of high amounts of sugar, which is highly deleterious for a person’s health. Consumption

of high amounts of sugar results in increased calorie intake, resulting in weight gain and

subsequent associated health concerns. The National Health and Medical Research Council

(NHMRC) recommended in the Australian dietary guidelines the limited consumption of sugar

rich drinks and replace them with fruit drinks, vitamin and sports drinks (Abs.gov.au, 2017).

This is a highly pressing issue regarding the health of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

inhabitants, since Australia is one of the highest consumers of the sweetened beverages. The

indigenous Australians were found to drink more amount of SSBs than the non-indigenous

Australians did. Most of the consumers are children and teenagers. Good health from childhood

lays the stepping stone for a good and healthy future ahead; however, such problems will prevent

the indigenous Australian children to look forward to a bright and healthy future.

1.4. Summary and Conclusion

This section focuses on the growing problem in Australia in association with increased

consumption of SSBs, particularly, among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The

children and the teenagers are the major consumers. SSBs like soft drinks, coffee, sweetened tea,

cordials, sweetened fruit juices are highly consumed by the indigenous Australians. This results

in high intake of sugar and calories thereby resulting in overall weight gain. Such weight gain

can give rise to serious health concerns among the children. The majority of the health concerns

include obesity, type 2 diabetes, dental caries, cancer and various cardiovascular diseases. The

Islander inhabitants showed SSB consumption compared to about 34% of the non-indigenous

community. Among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, 66% adults were

obese; while 29.7% children showed obesity (Avery et al. 2017, p. e016431). Diabetes and

cardiovascular diseases are largely experienced by the Aboriginal population than by the non-

indigenous population.

1.3. Synthesis of the data

Health problems like obesity, type 2 diabetes, cancer and various cardiovascular diseases

places a significant amount of burden on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals

and their families and the society in general. Sweetened beverages are the major concern in

association with these health outcomes, as consumption of these beverages lead to significant

intake of high amounts of sugar, which is highly deleterious for a person’s health. Consumption

of high amounts of sugar results in increased calorie intake, resulting in weight gain and

subsequent associated health concerns. The National Health and Medical Research Council

(NHMRC) recommended in the Australian dietary guidelines the limited consumption of sugar

rich drinks and replace them with fruit drinks, vitamin and sports drinks (Abs.gov.au, 2017).

This is a highly pressing issue regarding the health of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

inhabitants, since Australia is one of the highest consumers of the sweetened beverages. The

indigenous Australians were found to drink more amount of SSBs than the non-indigenous

Australians did. Most of the consumers are children and teenagers. Good health from childhood

lays the stepping stone for a good and healthy future ahead; however, such problems will prevent

the indigenous Australian children to look forward to a bright and healthy future.

1.4. Summary and Conclusion

This section focuses on the growing problem in Australia in association with increased

consumption of SSBs, particularly, among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The

children and the teenagers are the major consumers. SSBs like soft drinks, coffee, sweetened tea,

cordials, sweetened fruit juices are highly consumed by the indigenous Australians. This results

in high intake of sugar and calories thereby resulting in overall weight gain. Such weight gain

can give rise to serious health concerns among the children. The majority of the health concerns

include obesity, type 2 diabetes, dental caries, cancer and various cardiovascular diseases. The

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

children being the future, it is necessary to address this problem and limit the use of SSBs to

prevent such health risks in the future.

2. Analysis of the problem from an individual and socio-environmental perspective

Many factors or determinants were associated with SSB consumption. These factors were

categorized into environmental and personal factors. Moreover, socio-demographic factors were

taken into account.

2.1. Individual determinants

Various lifestyle factors play an essential role in contributing to obesity development.

Poverty management is essential in tackling obesity (Alvaro et al. 2010, pp.91-99). Social

aspects and food behaviours play an important role (Germov and Williams 2008, pp.3-23).

Various personal factors like attitude towards soft drinks also play an important role. Attitudes

like preference for soft drinks during meals, as a thirst quencher and soft drinks providing good

health are also important factors that determine the increased consumption of SSBs among

children. Research revealed that regular soft drinks were considered suitable to be taken with

meals as a thirst quencher and to have health benefits. Preferences like the taste of the soft drink

also played an important part in increasing soft drink consumption among children (van de Gaar

et al. 2017, p.195).

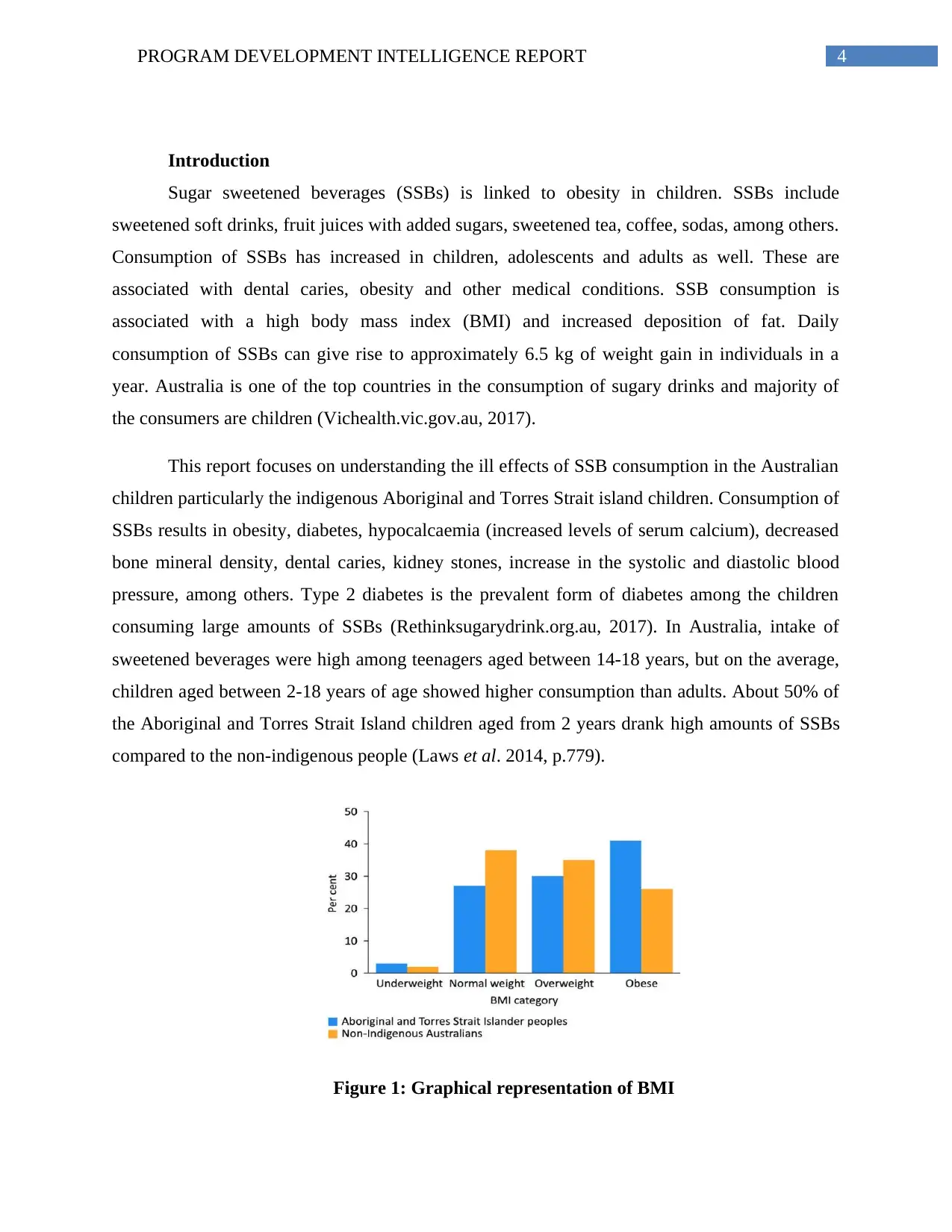

2.2. Socio-environmental determinants

Various environmental factors like accessibility, modelling (parents and elders who drink

soft drinks) and distance of the shop from home are important determinants for increased rates of

SSB consumption (Ogden 2011). Various socio-demographic factors like grades, gender, future

education plans and diet played a very important role in increased SSB consumption among

children (Pollard et al. 2016, pp.71-77). Boys were found to drink more soft drinks sometimes

twice a week or more. Moreover, those without any future education goals or plans were found

to drink more SSB compared to those who had a specific higher education plan in mind. The

tenth grade students were found to drink more regular soft drinks than their ninth grade

counterparts. Those dieting were found to drink more of diet soft drinks compared to those who

were not dieting (Armfield et al. 2013, pp.494-500).

children being the future, it is necessary to address this problem and limit the use of SSBs to

prevent such health risks in the future.

2. Analysis of the problem from an individual and socio-environmental perspective

Many factors or determinants were associated with SSB consumption. These factors were

categorized into environmental and personal factors. Moreover, socio-demographic factors were

taken into account.

2.1. Individual determinants

Various lifestyle factors play an essential role in contributing to obesity development.

Poverty management is essential in tackling obesity (Alvaro et al. 2010, pp.91-99). Social

aspects and food behaviours play an important role (Germov and Williams 2008, pp.3-23).

Various personal factors like attitude towards soft drinks also play an important role. Attitudes

like preference for soft drinks during meals, as a thirst quencher and soft drinks providing good

health are also important factors that determine the increased consumption of SSBs among

children. Research revealed that regular soft drinks were considered suitable to be taken with

meals as a thirst quencher and to have health benefits. Preferences like the taste of the soft drink

also played an important part in increasing soft drink consumption among children (van de Gaar

et al. 2017, p.195).

2.2. Socio-environmental determinants

Various environmental factors like accessibility, modelling (parents and elders who drink

soft drinks) and distance of the shop from home are important determinants for increased rates of

SSB consumption (Ogden 2011). Various socio-demographic factors like grades, gender, future

education plans and diet played a very important role in increased SSB consumption among

children (Pollard et al. 2016, pp.71-77). Boys were found to drink more soft drinks sometimes

twice a week or more. Moreover, those without any future education goals or plans were found

to drink more SSB compared to those who had a specific higher education plan in mind. The

tenth grade students were found to drink more regular soft drinks than their ninth grade

counterparts. Those dieting were found to drink more of diet soft drinks compared to those who

were not dieting (Armfield et al. 2013, pp.494-500).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

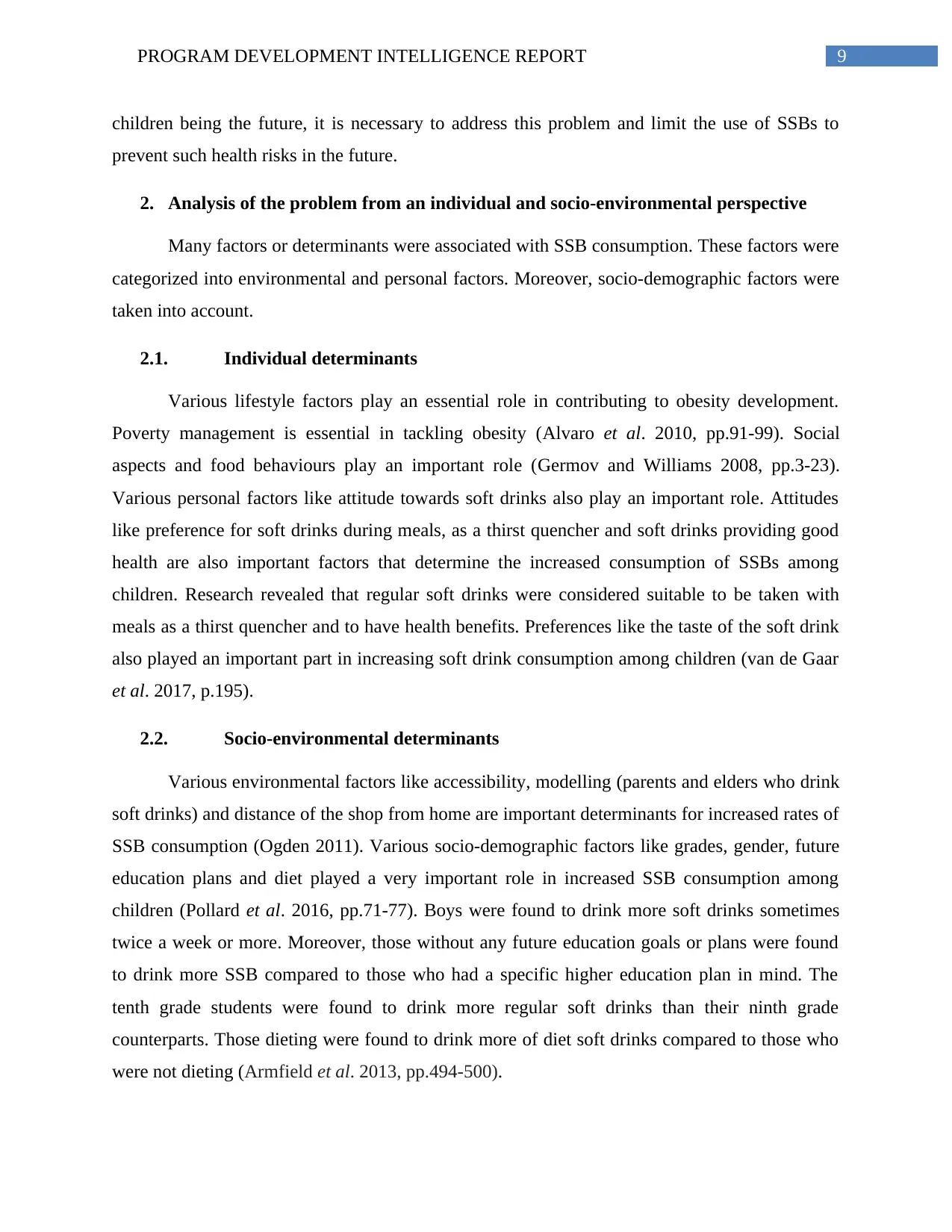

The children of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait suffer from a worse socio-economic

disadvantage compared to that of the non-indigenous Australian population. They are more

exposed to various environmental risk factors that affect their health. Moreover, they are also

exposed to various behavioural factors that affect their health (Shepherd, Li and Zubrick 2012,

pp.439-461). They live in poor households with minimum sanitary conditions that do not support

their development of good healthy habits. Very few of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait children

complete their class twelve education. Moreover, they also suffer from poor employment rates

(Sacks, Swinburn and Lawrence 2009, pp.76-86). Moreover, according to these people, health as

a holistic approach rather than being based on biomedical approach towards healthcare.

Moreover, they have poor access to fresh water, they experience many hardships, culture

dispossession, land dispossessions, racism and health exclusion. All these factors have led the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island community to be ignorant towards their health and thereby

resulting in increased consumption of soft drinks.

Figure 3: Graphical representation of gender difference in SSB consumption

(Source: Abs.gov.au, 2017)

The children of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait suffer from a worse socio-economic

disadvantage compared to that of the non-indigenous Australian population. They are more

exposed to various environmental risk factors that affect their health. Moreover, they are also

exposed to various behavioural factors that affect their health (Shepherd, Li and Zubrick 2012,

pp.439-461). They live in poor households with minimum sanitary conditions that do not support

their development of good healthy habits. Very few of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait children

complete their class twelve education. Moreover, they also suffer from poor employment rates

(Sacks, Swinburn and Lawrence 2009, pp.76-86). Moreover, according to these people, health as

a holistic approach rather than being based on biomedical approach towards healthcare.

Moreover, they have poor access to fresh water, they experience many hardships, culture

dispossession, land dispossessions, racism and health exclusion. All these factors have led the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island community to be ignorant towards their health and thereby

resulting in increased consumption of soft drinks.

Figure 3: Graphical representation of gender difference in SSB consumption

(Source: Abs.gov.au, 2017)

11PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT INTELLIGENCE REPORT

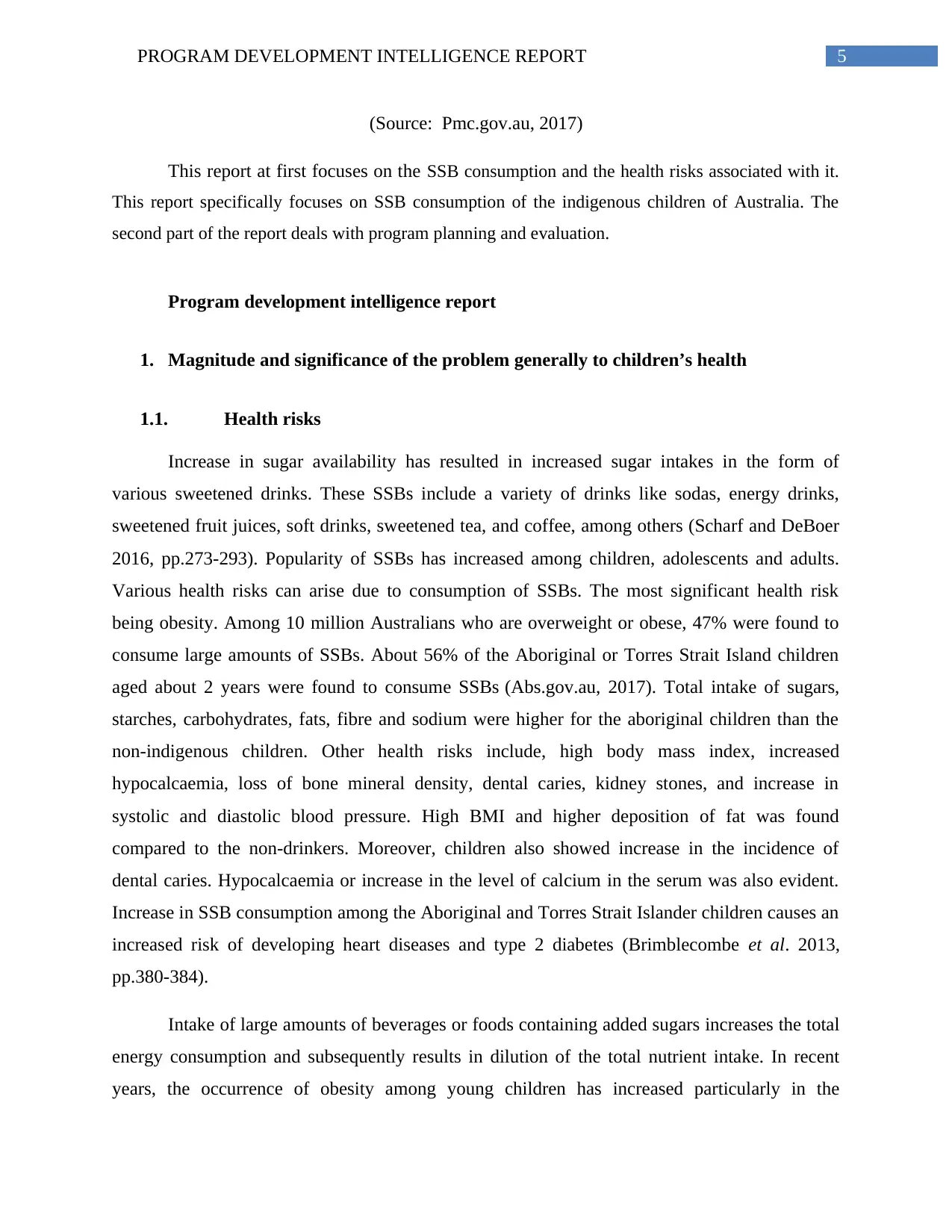

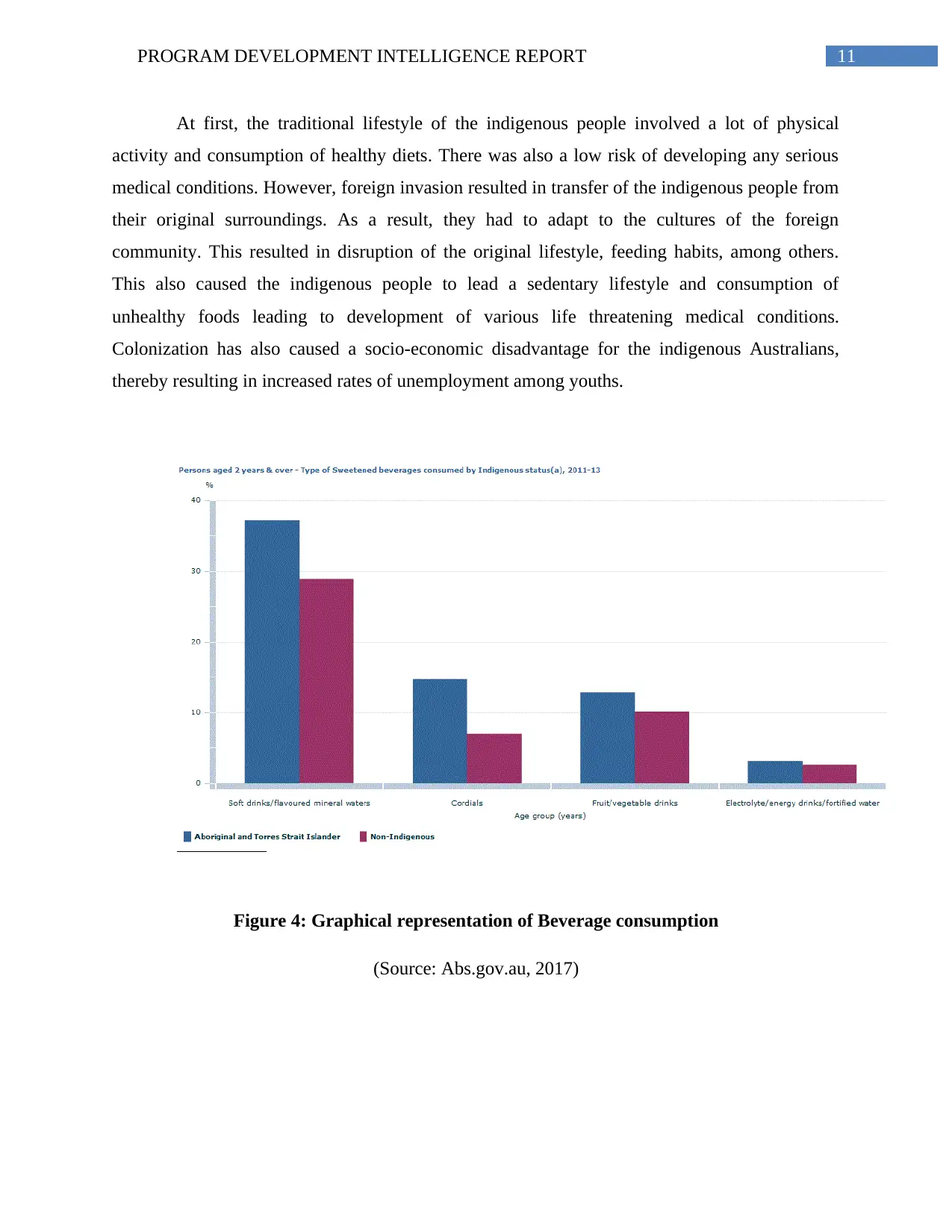

At first, the traditional lifestyle of the indigenous people involved a lot of physical

activity and consumption of healthy diets. There was also a low risk of developing any serious

medical conditions. However, foreign invasion resulted in transfer of the indigenous people from

their original surroundings. As a result, they had to adapt to the cultures of the foreign

community. This resulted in disruption of the original lifestyle, feeding habits, among others.

This also caused the indigenous people to lead a sedentary lifestyle and consumption of

unhealthy foods leading to development of various life threatening medical conditions.

Colonization has also caused a socio-economic disadvantage for the indigenous Australians,

thereby resulting in increased rates of unemployment among youths.

Figure 4: Graphical representation of Beverage consumption

(Source: Abs.gov.au, 2017)

At first, the traditional lifestyle of the indigenous people involved a lot of physical

activity and consumption of healthy diets. There was also a low risk of developing any serious

medical conditions. However, foreign invasion resulted in transfer of the indigenous people from

their original surroundings. As a result, they had to adapt to the cultures of the foreign

community. This resulted in disruption of the original lifestyle, feeding habits, among others.

This also caused the indigenous people to lead a sedentary lifestyle and consumption of

unhealthy foods leading to development of various life threatening medical conditions.

Colonization has also caused a socio-economic disadvantage for the indigenous Australians,

thereby resulting in increased rates of unemployment among youths.

Figure 4: Graphical representation of Beverage consumption

(Source: Abs.gov.au, 2017)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 19

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.