Psychological Assessment: DASS-21 Validation in North Queensland

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/17

|19

|4894

|57

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a psychometric validation study of the DASS-21 questionnaire, a self-report measure of depression, anxiety, and stress, within the North Queensland population. The study aimed to assess the reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and factor structure of the DASS-21. Participants (n=170) completed the DASS-21, the MHC-SF (a measure of well-being), and the BASIS-24 (a measure of mental illness). The results indicated high internal consistency for the DASS-21 subscales and overall scale. Convergent validity was established through positive correlations with the BASIS-24, while discriminant validity was demonstrated through negative correlations with the MHC-SF. Factor analysis confirmed the expected three-factor structure of the DASS-21. These findings support the use of the DASS-21 as a reliable and valid tool for assessing psychological distress in the North Queensland region. The study contributes to the understanding of mental health assessment in the region and provides a basis for future research and clinical applications.

Psychological Assessment – A North Queensland Case Study

By (Name of Student)

(Institutional Affiliation)

(Date of Submission)

By (Name of Student)

(Institutional Affiliation)

(Date of Submission)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Psychometric Validation of DASS21 in North-Queensland

Introduction

DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that contains a three Seven -item scale that

measures depression, stress and the anxiety (Henry & Crawford, 2005). This scale has not yet

been validated for North Queensland population despite the fact that DASS-21 was found to

have sufficient psychometric features (Antony, Bieling, Cox, Enns & Swinson, 1998). This

work thus aims to validate DASS, its internal consistency, convergent and discriminant

validity and factor structure for North Queensland population. This study established a strong

positive correlation and convergent validity with BASIS-24, a mental illness measure. Also,

DASS-21 established discriminant validity with MHC-SF, a measure of positive well-being.

Introduction

DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that contains a three Seven -item scale that

measures depression, stress and the anxiety (Henry & Crawford, 2005). This scale has not yet

been validated for North Queensland population despite the fact that DASS-21 was found to

have sufficient psychometric features (Antony, Bieling, Cox, Enns & Swinson, 1998). This

work thus aims to validate DASS, its internal consistency, convergent and discriminant

validity and factor structure for North Queensland population. This study established a strong

positive correlation and convergent validity with BASIS-24, a mental illness measure. Also,

DASS-21 established discriminant validity with MHC-SF, a measure of positive well-being.

Depression can be defined as a mood disorder bounded as a determined state of low

mood and anhedonia (Tully, 2009). According to Clark & Watson (1991), a positive effect is

either low or absent when experiencing depression and thus those people experience loss of

self-esteem, a sense of hopelessness and dysphonia.

Anxiety on the other hand is defined as a state of autonomic arousal and fearfulness

that is out of bound and proportion. Stress is well-defined by persistent muscle tension,

irritability, and a low threshold for becoming upset or frustrated (5th ed.; DSM–5; APA,

2013). It is associated to the negative effects as observed in generalized anxiety disorders

(Clark & Watson, 1991).

According to Kaspe (2005), anxiety and depression are believed to be the two primary

roots of mental illness disorders, and often co-occur, which led to explain the common

features of anxiety and depression. Many developed nations such United States and Australia,

face the problem of increasing mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety (Edmunds,

2018). Accordingly, the Australia’s estimated annual expenditure on curing mental illness has

now risen to a whopping twenty billion (National Mental Health report, 2013). Clark and

Watson (1991) thus asserted that anxiety and depression can be notable by unique

characteristics and proposed a tripartite framework of anxiety and depression that consist of

positive affect, physiological hyper arousal, and general distress. This is in conformity with

three psychometrically distinct factors namely depression, anxiety and stress which are also

primary constructs of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) (Brown, Chorpita,

Korotitsch & Barlow, 1997).

DASS-42 was developed as a screening tool for depression and anxiety disorders.

Psychometric validation has provided strong support for the scale’s internal consistency and

its convergent and discriminant validity with other existing measures like Beck Depression

and Anxiety Inventories in clinical and non-clinical samples (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995).

mood and anhedonia (Tully, 2009). According to Clark & Watson (1991), a positive effect is

either low or absent when experiencing depression and thus those people experience loss of

self-esteem, a sense of hopelessness and dysphonia.

Anxiety on the other hand is defined as a state of autonomic arousal and fearfulness

that is out of bound and proportion. Stress is well-defined by persistent muscle tension,

irritability, and a low threshold for becoming upset or frustrated (5th ed.; DSM–5; APA,

2013). It is associated to the negative effects as observed in generalized anxiety disorders

(Clark & Watson, 1991).

According to Kaspe (2005), anxiety and depression are believed to be the two primary

roots of mental illness disorders, and often co-occur, which led to explain the common

features of anxiety and depression. Many developed nations such United States and Australia,

face the problem of increasing mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety (Edmunds,

2018). Accordingly, the Australia’s estimated annual expenditure on curing mental illness has

now risen to a whopping twenty billion (National Mental Health report, 2013). Clark and

Watson (1991) thus asserted that anxiety and depression can be notable by unique

characteristics and proposed a tripartite framework of anxiety and depression that consist of

positive affect, physiological hyper arousal, and general distress. This is in conformity with

three psychometrically distinct factors namely depression, anxiety and stress which are also

primary constructs of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) (Brown, Chorpita,

Korotitsch & Barlow, 1997).

DASS-42 was developed as a screening tool for depression and anxiety disorders.

Psychometric validation has provided strong support for the scale’s internal consistency and

its convergent and discriminant validity with other existing measures like Beck Depression

and Anxiety Inventories in clinical and non-clinical samples (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of DASS-42 items have consistently

reproduced the three-factor structure in large nonclinical samples (Antony, Bieling, Cox,

Enns & Swinson, 1998). DASS-21, a shortened version of DASS-42, has fewer items, which

revealed cleaner factor structure and produced smaller inter-factor correlations, and was

subsequently adopted by numerous studies. DASS-21 has also been found to have strong

internal consistency (Henry & Crawford, 2005), convergent validity (Le et al., 2017) and

discriminant validity (Osman et al., 2012). Conducted factor analysis investigation revealed

that DASS-21 components were explicitly clustered into three sub-scales which measure

depression, anxiety and stress. The Depression scale measures symptoms associated with

worthlessness or sadness. The Anxiety scale included symptoms of fear, panic attacks, and

physical arousal. The Stress scales included symptoms such as irritability, overreaction, and

tension (Henry, & Crawford, 2005). DASS-21 has been verified across a multitude of

populations and proven useful (Azma,

Rusli, Quek, & Noah, 2014; Tran, Tran & Fisher, 2013; Teo et al., 2018).

Demographically, DASS-21 has also proven its validity through several Australian studies on

various groups to analyze the severity of depression, anxiety and stress. More recent

Australian studies include outpatient chemotherapy patients from Western Australia hospitals

(McMullen et al., 2017), patients undergoing traumatic brain injury rehabilitation from New

South Wales hospitals (Randall, Thomas, Whiting & McGrath, 2017), registered nurses

(Hegney et al., 2014), Australian mothers (Lovell, Huntsman & Hedley-Ward, 2015) as well

as younger and older adolescents (Tully, Zajac & Venning, 2009; Shaw, Campbell, Runions

& Zubrick, 2017).

Currently it is deemed that there is lack of validation in the North Queensland

population. Given the potential usefulness for research and clinical screening in North

Queensland, it is important to further examine the psychometric properties of the DASS-21

reproduced the three-factor structure in large nonclinical samples (Antony, Bieling, Cox,

Enns & Swinson, 1998). DASS-21, a shortened version of DASS-42, has fewer items, which

revealed cleaner factor structure and produced smaller inter-factor correlations, and was

subsequently adopted by numerous studies. DASS-21 has also been found to have strong

internal consistency (Henry & Crawford, 2005), convergent validity (Le et al., 2017) and

discriminant validity (Osman et al., 2012). Conducted factor analysis investigation revealed

that DASS-21 components were explicitly clustered into three sub-scales which measure

depression, anxiety and stress. The Depression scale measures symptoms associated with

worthlessness or sadness. The Anxiety scale included symptoms of fear, panic attacks, and

physical arousal. The Stress scales included symptoms such as irritability, overreaction, and

tension (Henry, & Crawford, 2005). DASS-21 has been verified across a multitude of

populations and proven useful (Azma,

Rusli, Quek, & Noah, 2014; Tran, Tran & Fisher, 2013; Teo et al., 2018).

Demographically, DASS-21 has also proven its validity through several Australian studies on

various groups to analyze the severity of depression, anxiety and stress. More recent

Australian studies include outpatient chemotherapy patients from Western Australia hospitals

(McMullen et al., 2017), patients undergoing traumatic brain injury rehabilitation from New

South Wales hospitals (Randall, Thomas, Whiting & McGrath, 2017), registered nurses

(Hegney et al., 2014), Australian mothers (Lovell, Huntsman & Hedley-Ward, 2015) as well

as younger and older adolescents (Tully, Zajac & Venning, 2009; Shaw, Campbell, Runions

& Zubrick, 2017).

Currently it is deemed that there is lack of validation in the North Queensland

population. Given the potential usefulness for research and clinical screening in North

Queensland, it is important to further examine the psychometric properties of the DASS-21

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

and its applicability in that context. To that end, DASS-21 was equated with other scales

namely MHC-SF and BASIS-24.

The four hypotheses in this study were;

H1: DASS-21 exhibits reliability

H2: There exists convergent validity with BASIS-24

H3: There exist divergent validity with MHC-SF

H4: There exist a three pure factor structure of DASS-21.

Methods

Participants

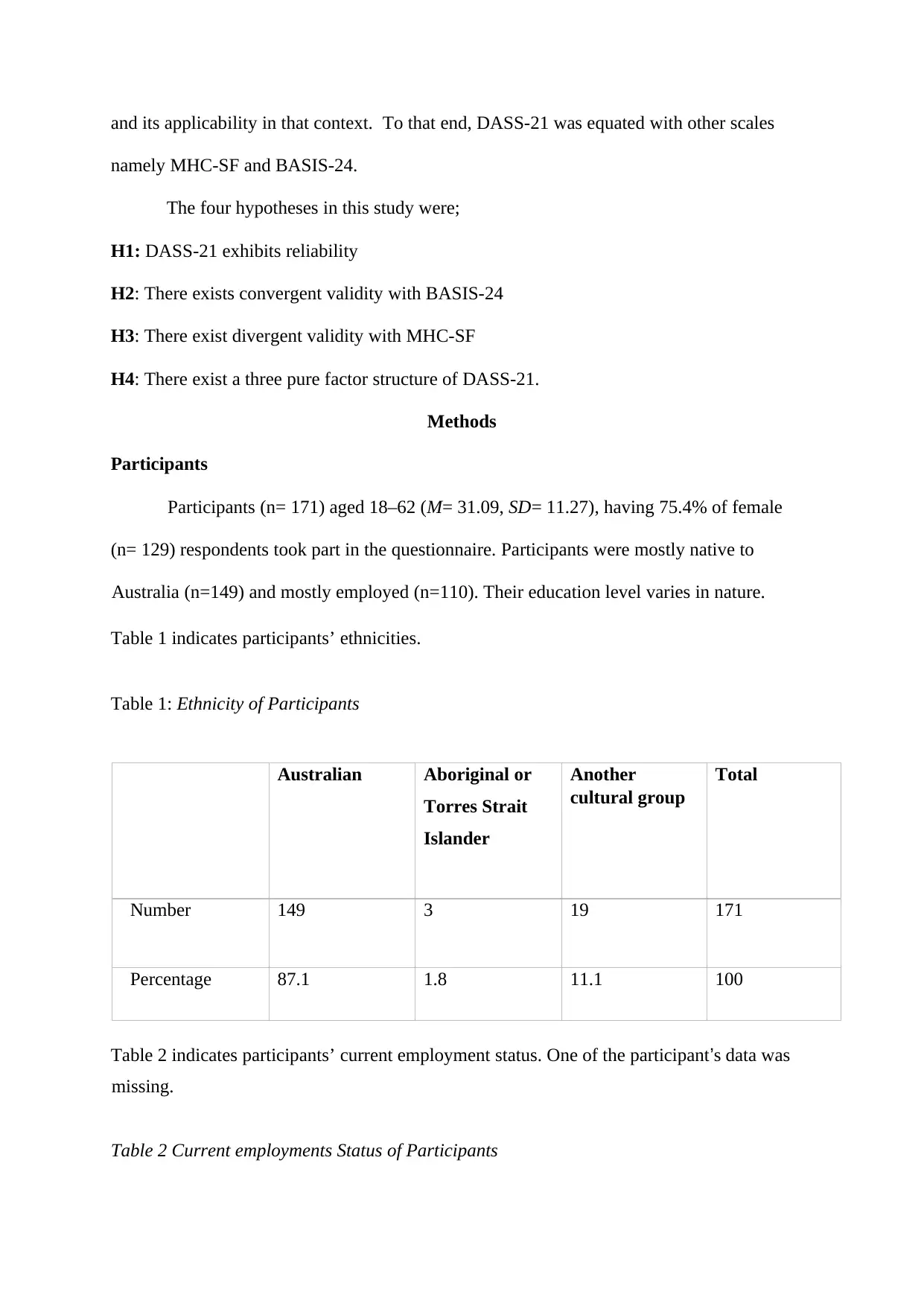

Participants (n= 171) aged 18–62 (M= 31.09, SD= 11.27), having 75.4% of female

(n= 129) respondents took part in the questionnaire. Participants were mostly native to

Australia (n=149) and mostly employed (n=110). Their education level varies in nature.

Table 1 indicates participants’ ethnicities.

Table 1: Ethnicity of Participants

Australian Aboriginal or

Torres Strait

Islander

Another

cultural group

Total

Number 149 3 19 171

Percentage 87.1 1.8 11.1 100

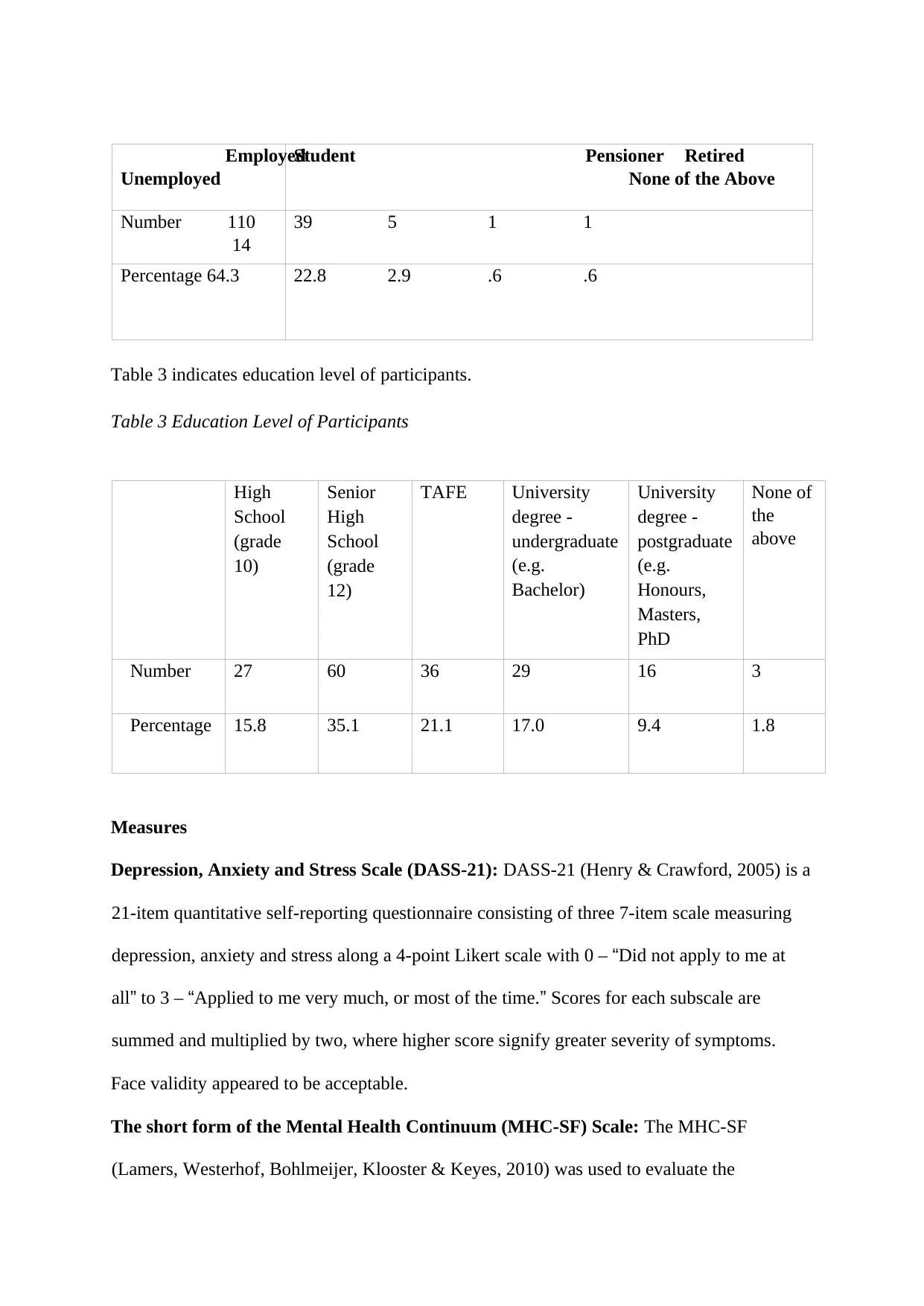

Table 2 indicates participants’ current employment status. One of the participant’s data was

missing.

Table 2 Current employments Status of Participants

namely MHC-SF and BASIS-24.

The four hypotheses in this study were;

H1: DASS-21 exhibits reliability

H2: There exists convergent validity with BASIS-24

H3: There exist divergent validity with MHC-SF

H4: There exist a three pure factor structure of DASS-21.

Methods

Participants

Participants (n= 171) aged 18–62 (M= 31.09, SD= 11.27), having 75.4% of female

(n= 129) respondents took part in the questionnaire. Participants were mostly native to

Australia (n=149) and mostly employed (n=110). Their education level varies in nature.

Table 1 indicates participants’ ethnicities.

Table 1: Ethnicity of Participants

Australian Aboriginal or

Torres Strait

Islander

Another

cultural group

Total

Number 149 3 19 171

Percentage 87.1 1.8 11.1 100

Table 2 indicates participants’ current employment status. One of the participant’s data was

missing.

Table 2 Current employments Status of Participants

Employed

Unemployed

Student Pensioner Retired

None of the Above

Number 110

14

39 5 1 1

Percentage 64.3 22.8 2.9 .6 .6

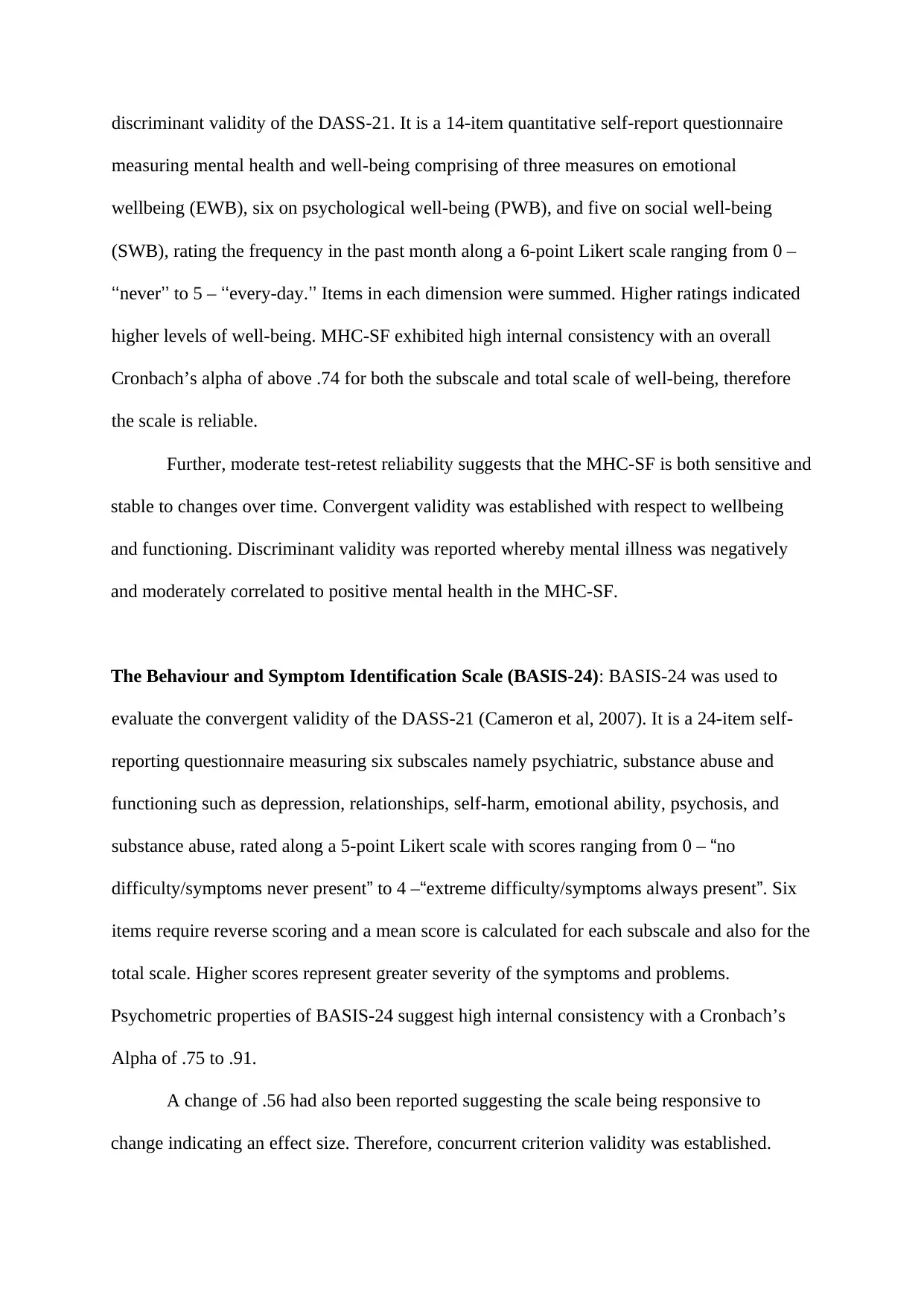

Table 3 indicates education level of participants.

Table 3 Education Level of Participants

High

School

(grade

10)

Senior

High

School

(grade

12)

TAFE University

degree -

undergraduate

(e.g.

Bachelor)

University

degree -

postgraduate

(e.g.

Honours,

Masters,

PhD

None of

the

above

Number 27 60 36 29 16 3

Percentage 15.8 35.1 21.1 17.0 9.4 1.8

Measures

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21): DASS-21 (Henry & Crawford, 2005) is a

21-item quantitative self-reporting questionnaire consisting of three 7-item scale measuring

depression, anxiety and stress along a 4-point Likert scale with 0 – “Did not apply to me at

all” to 3 – “Applied to me very much, or most of the time.” Scores for each subscale are

summed and multiplied by two, where higher score signify greater severity of symptoms.

Face validity appeared to be acceptable.

The short form of the Mental Health Continuum (MHC-SF) Scale: The MHC-SF

(Lamers, Westerhof, Bohlmeijer, Klooster & Keyes, 2010) was used to evaluate the

Unemployed

Student Pensioner Retired

None of the Above

Number 110

14

39 5 1 1

Percentage 64.3 22.8 2.9 .6 .6

Table 3 indicates education level of participants.

Table 3 Education Level of Participants

High

School

(grade

10)

Senior

High

School

(grade

12)

TAFE University

degree -

undergraduate

(e.g.

Bachelor)

University

degree -

postgraduate

(e.g.

Honours,

Masters,

PhD

None of

the

above

Number 27 60 36 29 16 3

Percentage 15.8 35.1 21.1 17.0 9.4 1.8

Measures

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21): DASS-21 (Henry & Crawford, 2005) is a

21-item quantitative self-reporting questionnaire consisting of three 7-item scale measuring

depression, anxiety and stress along a 4-point Likert scale with 0 – “Did not apply to me at

all” to 3 – “Applied to me very much, or most of the time.” Scores for each subscale are

summed and multiplied by two, where higher score signify greater severity of symptoms.

Face validity appeared to be acceptable.

The short form of the Mental Health Continuum (MHC-SF) Scale: The MHC-SF

(Lamers, Westerhof, Bohlmeijer, Klooster & Keyes, 2010) was used to evaluate the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

discriminant validity of the DASS-21. It is a 14-item quantitative self-report questionnaire

measuring mental health and well-being comprising of three measures on emotional

wellbeing (EWB), six on psychological well-being (PWB), and five on social well-being

(SWB), rating the frequency in the past month along a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 –

‘‘never’’ to 5 – ‘‘every-day.’’ Items in each dimension were summed. Higher ratings indicated

higher levels of well-being. MHC-SF exhibited high internal consistency with an overall

Cronbach’s alpha of above .74 for both the subscale and total scale of well-being, therefore

the scale is reliable.

Further, moderate test-retest reliability suggests that the MHC-SF is both sensitive and

stable to changes over time. Convergent validity was established with respect to wellbeing

and functioning. Discriminant validity was reported whereby mental illness was negatively

and moderately correlated to positive mental health in the MHC-SF.

The Behaviour and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-24): BASIS-24 was used to

evaluate the convergent validity of the DASS-21 (Cameron et al, 2007). It is a 24-item self-

reporting questionnaire measuring six subscales namely psychiatric, substance abuse and

functioning such as depression, relationships, self-harm, emotional ability, psychosis, and

substance abuse, rated along a 5-point Likert scale with scores ranging from 0 – “no

difficulty/symptoms never present” to 4 –“extreme difficulty/symptoms always present”. Six

items require reverse scoring and a mean score is calculated for each subscale and also for the

total scale. Higher scores represent greater severity of the symptoms and problems.

Psychometric properties of BASIS-24 suggest high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s

Alpha of .75 to .91.

A change of .56 had also been reported suggesting the scale being responsive to

change indicating an effect size. Therefore, concurrent criterion validity was established.

measuring mental health and well-being comprising of three measures on emotional

wellbeing (EWB), six on psychological well-being (PWB), and five on social well-being

(SWB), rating the frequency in the past month along a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 –

‘‘never’’ to 5 – ‘‘every-day.’’ Items in each dimension were summed. Higher ratings indicated

higher levels of well-being. MHC-SF exhibited high internal consistency with an overall

Cronbach’s alpha of above .74 for both the subscale and total scale of well-being, therefore

the scale is reliable.

Further, moderate test-retest reliability suggests that the MHC-SF is both sensitive and

stable to changes over time. Convergent validity was established with respect to wellbeing

and functioning. Discriminant validity was reported whereby mental illness was negatively

and moderately correlated to positive mental health in the MHC-SF.

The Behaviour and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-24): BASIS-24 was used to

evaluate the convergent validity of the DASS-21 (Cameron et al, 2007). It is a 24-item self-

reporting questionnaire measuring six subscales namely psychiatric, substance abuse and

functioning such as depression, relationships, self-harm, emotional ability, psychosis, and

substance abuse, rated along a 5-point Likert scale with scores ranging from 0 – “no

difficulty/symptoms never present” to 4 –“extreme difficulty/symptoms always present”. Six

items require reverse scoring and a mean score is calculated for each subscale and also for the

total scale. Higher scores represent greater severity of the symptoms and problems.

Psychometric properties of BASIS-24 suggest high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s

Alpha of .75 to .91.

A change of .56 had also been reported suggesting the scale being responsive to

change indicating an effect size. Therefore, concurrent criterion validity was established.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Procedure

Approval for ethical compliance was first obtained from the James Cook University

Human Research Ethics Committee. Upon approval, the DASS-21, MHC-SF and BASIS-24

questionnaire were uploaded on a web link which was provided to participants who were

recruited via snowball sampling. Informed consent was obtained from participants. Data

were collected and analyzed after response submission.

Results

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23. Out of

sample size of 171, one participant data was excluded from the analysis as it was an outlier.

Therefore, sample size for analysis was 170. Descriptive statistic, reliability analysis and

factor analysis were conducted. Convergent and discriminant validity were also conducted

using Pearson product-moment correlation analysis.

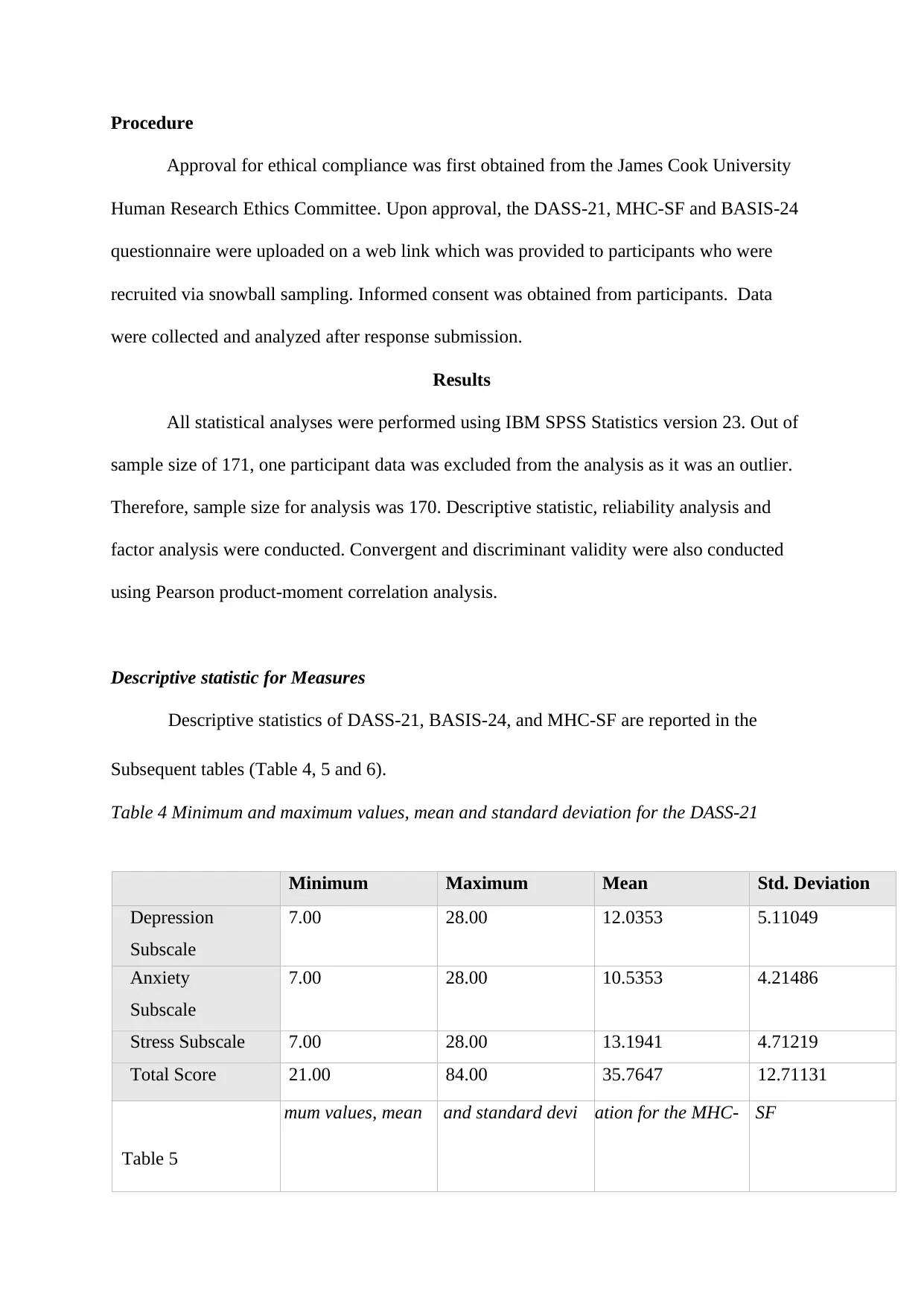

Descriptive statistic for Measures

Descriptive statistics of DASS-21, BASIS-24, and MHC-SF are reported in the

Subsequent tables (Table 4, 5 and 6).

Table 4 Minimum and maximum values, mean and standard deviation for the DASS-21

Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation

Depression

Subscale

7.00 28.00 12.0353 5.11049

Anxiety

Subscale

7.00 28.00 10.5353 4.21486

Stress Subscale 7.00 28.00 13.1941 4.71219

Total Score 21.00 84.00 35.7647 12.71131

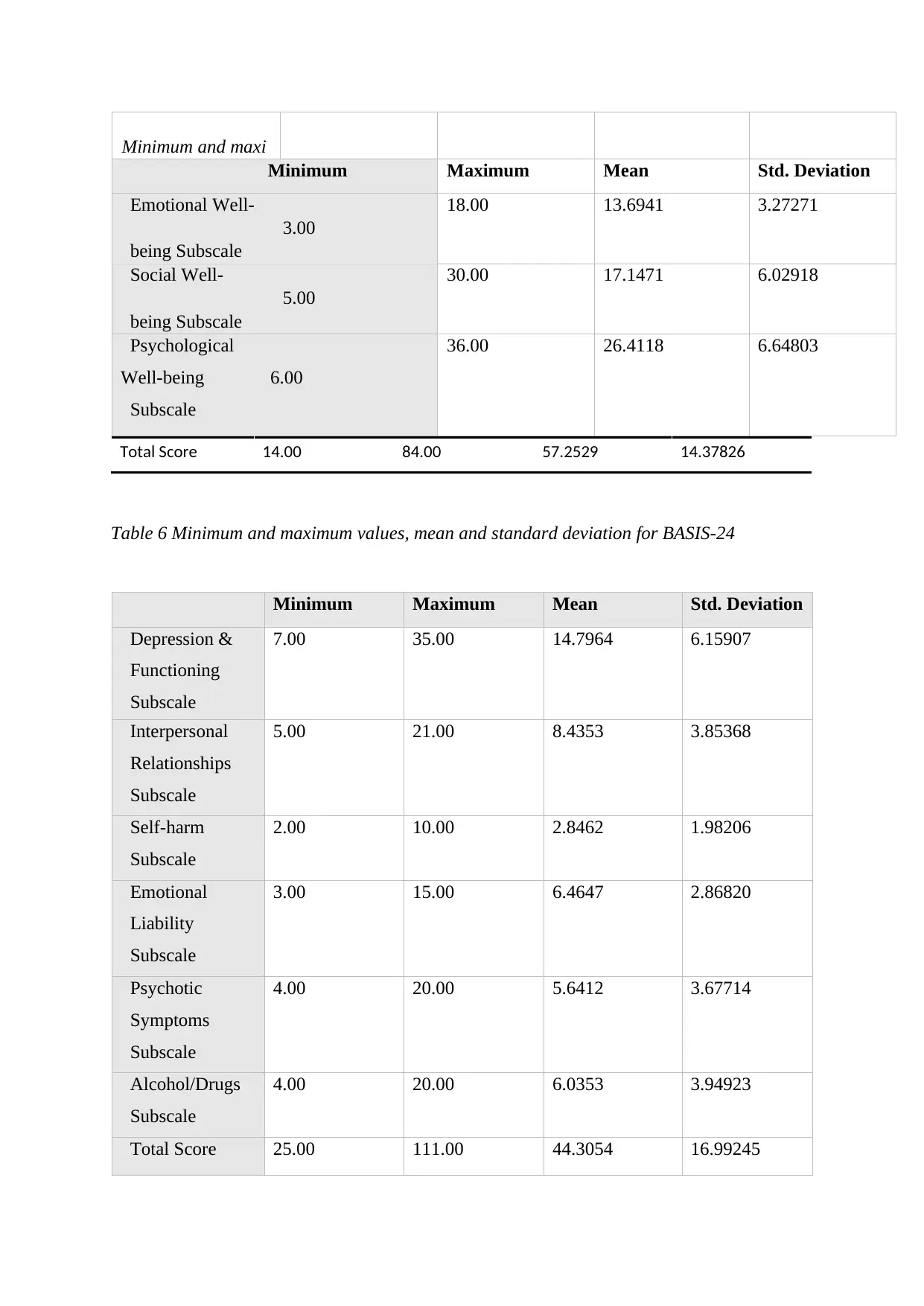

Table 5

mum values, mean and standard devi ation for the MHC- SF

Approval for ethical compliance was first obtained from the James Cook University

Human Research Ethics Committee. Upon approval, the DASS-21, MHC-SF and BASIS-24

questionnaire were uploaded on a web link which was provided to participants who were

recruited via snowball sampling. Informed consent was obtained from participants. Data

were collected and analyzed after response submission.

Results

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23. Out of

sample size of 171, one participant data was excluded from the analysis as it was an outlier.

Therefore, sample size for analysis was 170. Descriptive statistic, reliability analysis and

factor analysis were conducted. Convergent and discriminant validity were also conducted

using Pearson product-moment correlation analysis.

Descriptive statistic for Measures

Descriptive statistics of DASS-21, BASIS-24, and MHC-SF are reported in the

Subsequent tables (Table 4, 5 and 6).

Table 4 Minimum and maximum values, mean and standard deviation for the DASS-21

Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation

Depression

Subscale

7.00 28.00 12.0353 5.11049

Anxiety

Subscale

7.00 28.00 10.5353 4.21486

Stress Subscale 7.00 28.00 13.1941 4.71219

Total Score 21.00 84.00 35.7647 12.71131

Table 5

mum values, mean and standard devi ation for the MHC- SF

Minimum and maxi

Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation

Emotional Well-

3.00

being Subscale

18.00 13.6941 3.27271

Social Well-

5.00

being Subscale

30.00 17.1471 6.02918

Psychological

Well-being 6.00

Subscale

36.00 26.4118 6.64803

Table 6 Minimum and maximum values, mean and standard deviation for BASIS-24

Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation

Depression &

Functioning

Subscale

7.00 35.00 14.7964 6.15907

Interpersonal

Relationships

Subscale

5.00 21.00 8.4353 3.85368

Self-harm

Subscale

2.00 10.00 2.8462 1.98206

Emotional

Liability

Subscale

3.00 15.00 6.4647 2.86820

Psychotic

Symptoms

Subscale

4.00 20.00 5.6412 3.67714

Alcohol/Drugs

Subscale

4.00 20.00 6.0353 3.94923

Total Score 25.00 111.00 44.3054 16.99245

Total Score 14.00 84.00 57.2529 14.37826

Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation

Emotional Well-

3.00

being Subscale

18.00 13.6941 3.27271

Social Well-

5.00

being Subscale

30.00 17.1471 6.02918

Psychological

Well-being 6.00

Subscale

36.00 26.4118 6.64803

Table 6 Minimum and maximum values, mean and standard deviation for BASIS-24

Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation

Depression &

Functioning

Subscale

7.00 35.00 14.7964 6.15907

Interpersonal

Relationships

Subscale

5.00 21.00 8.4353 3.85368

Self-harm

Subscale

2.00 10.00 2.8462 1.98206

Emotional

Liability

Subscale

3.00 15.00 6.4647 2.86820

Psychotic

Symptoms

Subscale

4.00 20.00 5.6412 3.67714

Alcohol/Drugs

Subscale

4.00 20.00 6.0353 3.94923

Total Score 25.00 111.00 44.3054 16.99245

Total Score 14.00 84.00 57.2529 14.37826

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Hypothesis 1: DASS-21 exhibits reliability

The Cronbach alpha for DASS-21 on overall and individual subscales were high and positive.

Overall it is .951, for depression it is .927, for anxiety it is .860, for stress it is .892.

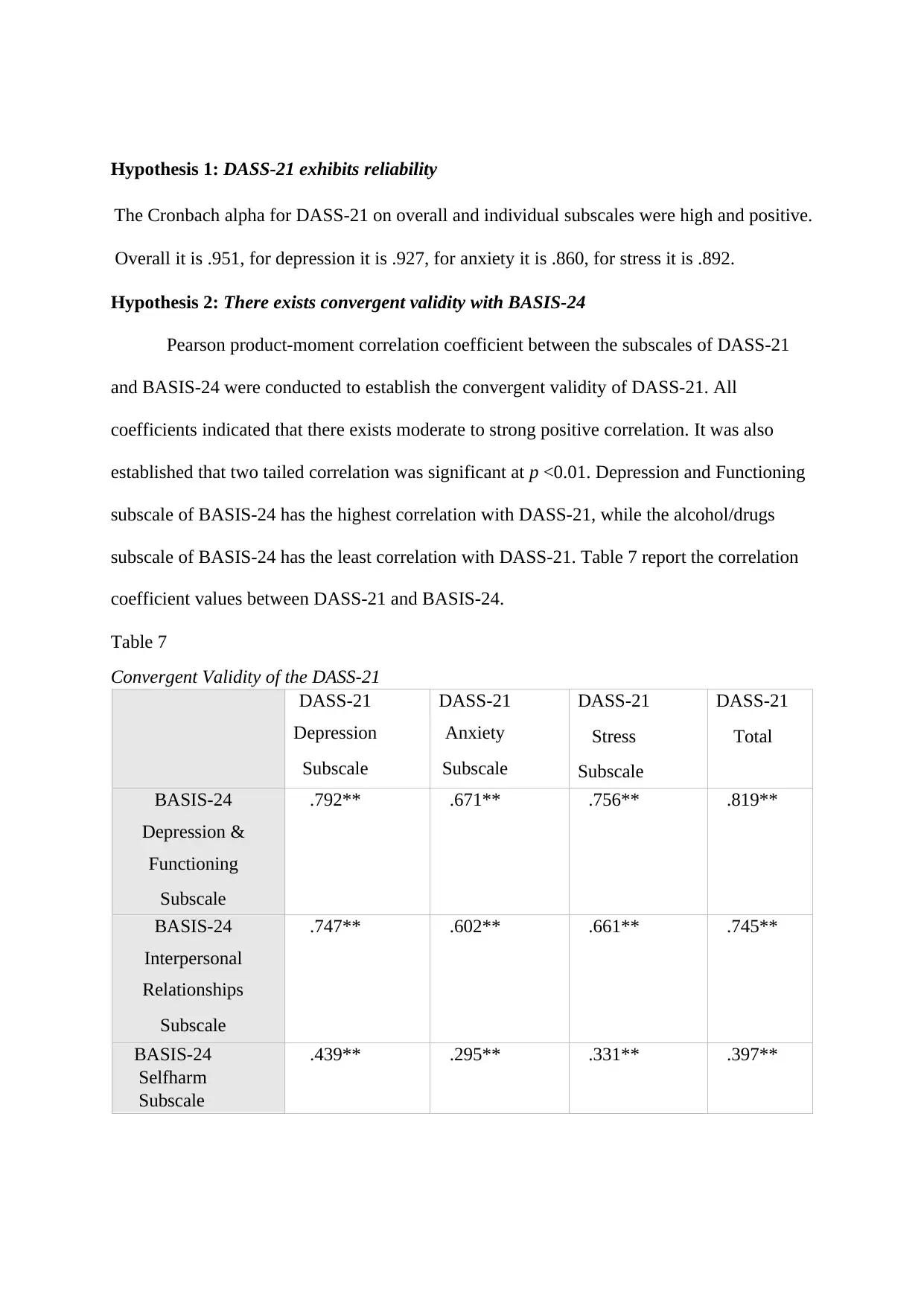

Hypothesis 2: There exists convergent validity with BASIS-24

Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient between the subscales of DASS-21

and BASIS-24 were conducted to establish the convergent validity of DASS-21. All

coefficients indicated that there exists moderate to strong positive correlation. It was also

established that two tailed correlation was significant at p <0.01. Depression and Functioning

subscale of BASIS-24 has the highest correlation with DASS-21, while the alcohol/drugs

subscale of BASIS-24 has the least correlation with DASS-21. Table 7 report the correlation

coefficient values between DASS-21 and BASIS-24.

Table 7

Convergent Validity of the DASS-21

DASS-21

Depression

Subscale

DASS-21

Anxiety

Subscale

DASS-21

Stress

Subscale

DASS-21

Total

BASIS-24

Depression &

Functioning

Subscale

.792** .671** .756** .819**

BASIS-24

Interpersonal

Relationships

Subscale

.747** .602** .661** .745**

BASIS-24

Selfharm

Subscale

.439** .295** .331** .397**

The Cronbach alpha for DASS-21 on overall and individual subscales were high and positive.

Overall it is .951, for depression it is .927, for anxiety it is .860, for stress it is .892.

Hypothesis 2: There exists convergent validity with BASIS-24

Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient between the subscales of DASS-21

and BASIS-24 were conducted to establish the convergent validity of DASS-21. All

coefficients indicated that there exists moderate to strong positive correlation. It was also

established that two tailed correlation was significant at p <0.01. Depression and Functioning

subscale of BASIS-24 has the highest correlation with DASS-21, while the alcohol/drugs

subscale of BASIS-24 has the least correlation with DASS-21. Table 7 report the correlation

coefficient values between DASS-21 and BASIS-24.

Table 7

Convergent Validity of the DASS-21

DASS-21

Depression

Subscale

DASS-21

Anxiety

Subscale

DASS-21

Stress

Subscale

DASS-21

Total

BASIS-24

Depression &

Functioning

Subscale

.792** .671** .756** .819**

BASIS-24

Interpersonal

Relationships

Subscale

.747** .602** .661** .745**

BASIS-24

Selfharm

Subscale

.439** .295** .331** .397**

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

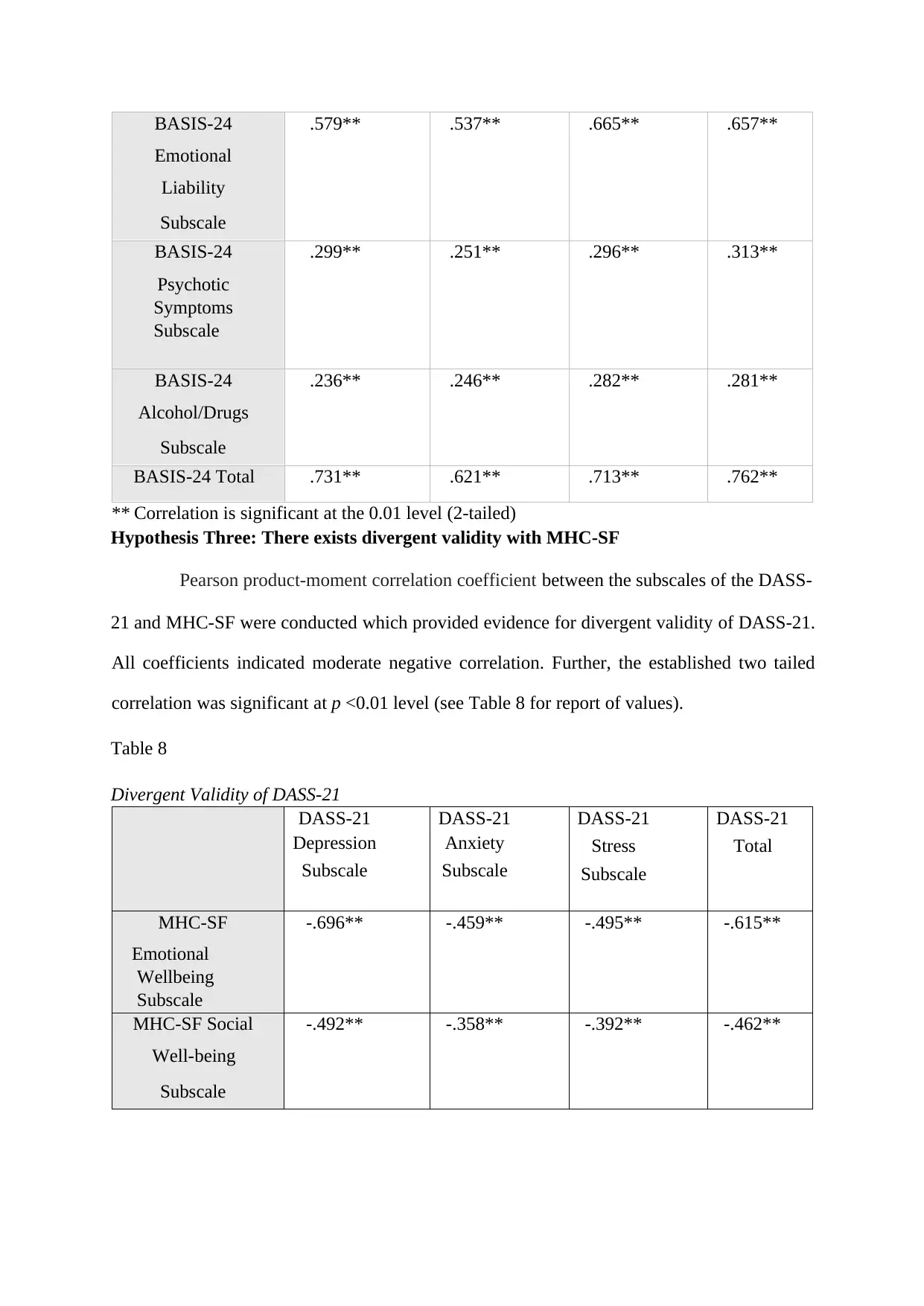

BASIS-24

Emotional

Liability

Subscale

.579** .537** .665** .657**

BASIS-24

Psychotic

Symptoms

Subscale

.299** .251** .296** .313**

BASIS-24

Alcohol/Drugs

Subscale

.236** .246** .282** .281**

BASIS-24 Total .731** .621** .713** .762**

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Hypothesis Three: There exists divergent validity with MHC-SF

Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient between the subscales of the DASS-

21 and MHC-SF were conducted which provided evidence for divergent validity of DASS-21.

All coefficients indicated moderate negative correlation. Further, the established two tailed

correlation was significant at p <0.01 level (see Table 8 for report of values).

Table 8

Divergent Validity of DASS-21

DASS-21

Depression

Subscale

DASS-21

Anxiety

Subscale

DASS-21

Stress

Subscale

DASS-21

Total

MHC-SF

Emotional

Wellbeing

Subscale

-.696** -.459** -.495** -.615**

MHC-SF Social

Well-being

Subscale

-.492** -.358** -.392** -.462**

Emotional

Liability

Subscale

.579** .537** .665** .657**

BASIS-24

Psychotic

Symptoms

Subscale

.299** .251** .296** .313**

BASIS-24

Alcohol/Drugs

Subscale

.236** .246** .282** .281**

BASIS-24 Total .731** .621** .713** .762**

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Hypothesis Three: There exists divergent validity with MHC-SF

Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient between the subscales of the DASS-

21 and MHC-SF were conducted which provided evidence for divergent validity of DASS-21.

All coefficients indicated moderate negative correlation. Further, the established two tailed

correlation was significant at p <0.01 level (see Table 8 for report of values).

Table 8

Divergent Validity of DASS-21

DASS-21

Depression

Subscale

DASS-21

Anxiety

Subscale

DASS-21

Stress

Subscale

DASS-21

Total

MHC-SF

Emotional

Wellbeing

Subscale

-.696** -.459** -.495** -.615**

MHC-SF Social

Well-being

Subscale

-.492** -.358** -.392** -.462**

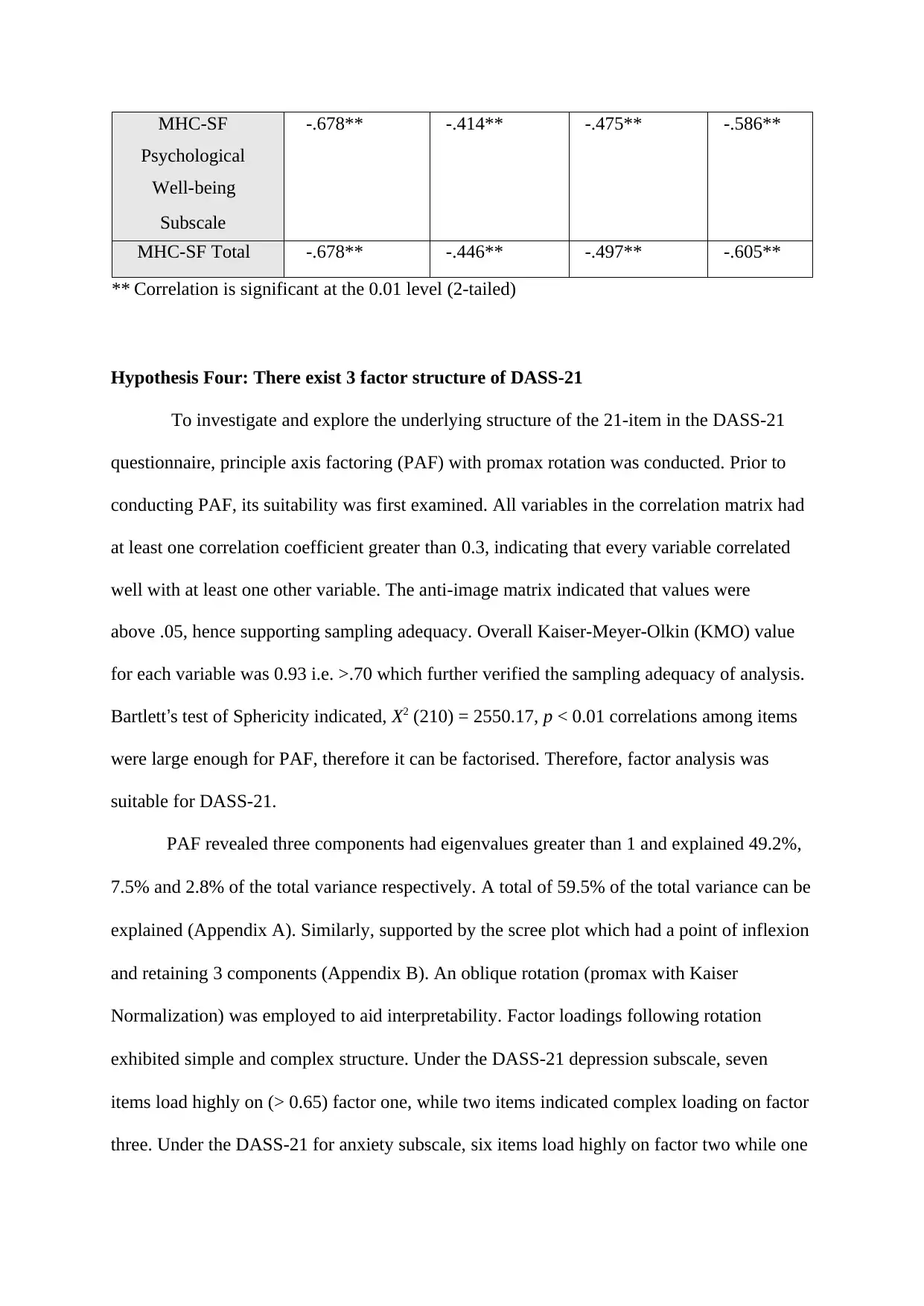

MHC-SF

Psychological

Well-being

Subscale

-.678** -.414** -.475** -.586**

MHC-SF Total -.678** -.446** -.497** -.605**

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Hypothesis Four: There exist 3 factor structure of DASS-21

To investigate and explore the underlying structure of the 21-item in the DASS-21

questionnaire, principle axis factoring (PAF) with promax rotation was conducted. Prior to

conducting PAF, its suitability was first examined. All variables in the correlation matrix had

at least one correlation coefficient greater than 0.3, indicating that every variable correlated

well with at least one other variable. The anti-image matrix indicated that values were

above .05, hence supporting sampling adequacy. Overall Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value

for each variable was 0.93 i.e. >.70 which further verified the sampling adequacy of analysis.

Bartlett’s test of Sphericity indicated, X2 (210) = 2550.17, p < 0.01 correlations among items

were large enough for PAF, therefore it can be factorised. Therefore, factor analysis was

suitable for DASS-21.

PAF revealed three components had eigenvalues greater than 1 and explained 49.2%,

7.5% and 2.8% of the total variance respectively. A total of 59.5% of the total variance can be

explained (Appendix A). Similarly, supported by the scree plot which had a point of inflexion

and retaining 3 components (Appendix B). An oblique rotation (promax with Kaiser

Normalization) was employed to aid interpretability. Factor loadings following rotation

exhibited simple and complex structure. Under the DASS-21 depression subscale, seven

items load highly on (> 0.65) factor one, while two items indicated complex loading on factor

three. Under the DASS-21 for anxiety subscale, six items load highly on factor two while one

Psychological

Well-being

Subscale

-.678** -.414** -.475** -.586**

MHC-SF Total -.678** -.446** -.497** -.605**

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Hypothesis Four: There exist 3 factor structure of DASS-21

To investigate and explore the underlying structure of the 21-item in the DASS-21

questionnaire, principle axis factoring (PAF) with promax rotation was conducted. Prior to

conducting PAF, its suitability was first examined. All variables in the correlation matrix had

at least one correlation coefficient greater than 0.3, indicating that every variable correlated

well with at least one other variable. The anti-image matrix indicated that values were

above .05, hence supporting sampling adequacy. Overall Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value

for each variable was 0.93 i.e. >.70 which further verified the sampling adequacy of analysis.

Bartlett’s test of Sphericity indicated, X2 (210) = 2550.17, p < 0.01 correlations among items

were large enough for PAF, therefore it can be factorised. Therefore, factor analysis was

suitable for DASS-21.

PAF revealed three components had eigenvalues greater than 1 and explained 49.2%,

7.5% and 2.8% of the total variance respectively. A total of 59.5% of the total variance can be

explained (Appendix A). Similarly, supported by the scree plot which had a point of inflexion

and retaining 3 components (Appendix B). An oblique rotation (promax with Kaiser

Normalization) was employed to aid interpretability. Factor loadings following rotation

exhibited simple and complex structure. Under the DASS-21 depression subscale, seven

items load highly on (> 0.65) factor one, while two items indicated complex loading on factor

three. Under the DASS-21 for anxiety subscale, six items load highly on factor two while one

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 19

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.