An Analysis of Racial/Ethnic Health Disparities in Refugee Healthcare

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/01

|13

|3894

|6

Report

AI Summary

This report delves into the critical issue of racial and ethnic health disparities affecting refugees in Australia. It highlights the vulnerability of refugees due to factors such as trauma, discrimination, and lack of protection from their native lands, emphasizing the importance of support rather than mere identification. The report examines how social determinants of health, including discrimination, racism, and distrust of the government, hinder refugees' access to the Australian healthcare system. It explores the impact of these factors on mental health, access to employment, housing, education, and the ability to afford essential needs like a balanced diet and medication. Furthermore, the report discusses health inequalities and inequities, such as differences in health status, access to basic healthcare, and affordability, which contribute to adverse health outcomes among refugees. It also addresses the role of language barriers and communication difficulties between refugees and healthcare providers. The report concludes by emphasizing the need to address these disparities and improve the healthcare experiences and outcomes for refugee populations in Australia.

Running Head: RACIAL/ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN HEALTHCARE AMONG REFUGEES

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

Institution

Student name

Date

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

Institution

Student name

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

From a health and healthcare perspective, there is no doubt that asylum seekers are

among the most vulnerable groups in Australia (Silove, Ventevogel, & Rees, 2017). As an

overall proposition, it can be reasoned that refugees are per se risk since they are outside their

native country. Their susceptibility originates from the trauma, violence, and discrimination they

have experienced and the fact that their very own state cannot offer any form of protection to

them. Silove, Ventevogel, and Rees (2017), however, argue that vulnerability should not be

based merely on one’s belonging to a certain group that is considered underprivileged, but rather

as an individual. While this paper is not insinuating that the latter perspective is indecorous, it’s

worth noting that there exists a certain degree of vulnerability to any refugee irrespective of his

or her previous or current socioeconomic status and emphasis should, therefore, be based on

support rather than identification. For purposes of this essay, the author adopts the position that

all refugees in Australia are vulnerable due to the fact that they are outside the protection of their

native land. The author will rely on a number of factors such as social determinants of health,

health inequalities, health inequities and health outcomes to reinforce this standpoint.

Taylor and Haintz (2018) assert that a surfeit of factors hinder refuges in Australia from

fully utilizing the Australian healthcare system. In their research, the duo examined several

SDHs on refugees’ access to Australian healthcare services. Social norms and attitudes such as

discrimination, racism, and distrust of government ranked top among the social determinants of

refugee health in Australia. Research shows that perceived discrimination and distrust of the

government have been identified to bear huge detrimental effect on the mental health of African

refugees currently in Australia. With increasing incidences of terrorist attacks in recent years, the

fundamental rights of asylum seekers and refugees have been violated in Australia’s interest to

fight terrorism (Taylor & Haintz, 2018). This has led to increased discrimination and racism

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

From a health and healthcare perspective, there is no doubt that asylum seekers are

among the most vulnerable groups in Australia (Silove, Ventevogel, & Rees, 2017). As an

overall proposition, it can be reasoned that refugees are per se risk since they are outside their

native country. Their susceptibility originates from the trauma, violence, and discrimination they

have experienced and the fact that their very own state cannot offer any form of protection to

them. Silove, Ventevogel, and Rees (2017), however, argue that vulnerability should not be

based merely on one’s belonging to a certain group that is considered underprivileged, but rather

as an individual. While this paper is not insinuating that the latter perspective is indecorous, it’s

worth noting that there exists a certain degree of vulnerability to any refugee irrespective of his

or her previous or current socioeconomic status and emphasis should, therefore, be based on

support rather than identification. For purposes of this essay, the author adopts the position that

all refugees in Australia are vulnerable due to the fact that they are outside the protection of their

native land. The author will rely on a number of factors such as social determinants of health,

health inequalities, health inequities and health outcomes to reinforce this standpoint.

Taylor and Haintz (2018) assert that a surfeit of factors hinder refuges in Australia from

fully utilizing the Australian healthcare system. In their research, the duo examined several

SDHs on refugees’ access to Australian healthcare services. Social norms and attitudes such as

discrimination, racism, and distrust of government ranked top among the social determinants of

refugee health in Australia. Research shows that perceived discrimination and distrust of the

government have been identified to bear huge detrimental effect on the mental health of African

refugees currently in Australia. With increasing incidences of terrorist attacks in recent years, the

fundamental rights of asylum seekers and refugees have been violated in Australia’s interest to

fight terrorism (Taylor & Haintz, 2018). This has led to increased discrimination and racism

3

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

towards these populations. Perceived segregation has negatively impacted refugee health in

several ways including reduced access to housing, education and employment and leading to

severe emotional distress and associated psychopathology (Shishehgar et al., 2017). In addition,

findings show that emotional negativity emanating from prejudiced experiences leads to

functional and structural adjustments in several physiological systems of the victim.

Discriminatory treatment as Mahimbo et al. (2017) contents, deeply affects one's self-efficacy

and self-esteem thus fettering opportunities for the victim's participation in economic and social

spheres.

The 1951 Convention on Refugee rights grants refugees employment opportunities and

participation in other economic activities. However, most host nations have been unwilling to

permit this right. Several factors influence this reluctance and include security concerns about

large numbers of refugees gaining settlement, job availability for the natives, limited capacity to

absorb labor and fear for xenophobic uprisings against the foreigners like the case of South

Africa. Although a party to the 1951 refugee convention, Australia declares reservations and the

refugee grant to work is subject to the labor market index among other stringent conditions.

Apart from mental distress, lack of access to job and economic activities bears direct

implications on refugee health as the majority are unable to afford a balanced diet due to a lack

of financial resources. Additionally, due to lack of adequate financial resources emanating from

joblessness, most refugees are unable to acquire decent housing and clean water and are thus

forced to reside in camps that are highly susceptible to airborne and infectious ailments. Lastly,

the refugee unemployed may not be able to afford proper medication in the event that they fall

sick due to a lack of monies to fund their medication (Fisher et al., 2016).

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

towards these populations. Perceived segregation has negatively impacted refugee health in

several ways including reduced access to housing, education and employment and leading to

severe emotional distress and associated psychopathology (Shishehgar et al., 2017). In addition,

findings show that emotional negativity emanating from prejudiced experiences leads to

functional and structural adjustments in several physiological systems of the victim.

Discriminatory treatment as Mahimbo et al. (2017) contents, deeply affects one's self-efficacy

and self-esteem thus fettering opportunities for the victim's participation in economic and social

spheres.

The 1951 Convention on Refugee rights grants refugees employment opportunities and

participation in other economic activities. However, most host nations have been unwilling to

permit this right. Several factors influence this reluctance and include security concerns about

large numbers of refugees gaining settlement, job availability for the natives, limited capacity to

absorb labor and fear for xenophobic uprisings against the foreigners like the case of South

Africa. Although a party to the 1951 refugee convention, Australia declares reservations and the

refugee grant to work is subject to the labor market index among other stringent conditions.

Apart from mental distress, lack of access to job and economic activities bears direct

implications on refugee health as the majority are unable to afford a balanced diet due to a lack

of financial resources. Additionally, due to lack of adequate financial resources emanating from

joblessness, most refugees are unable to acquire decent housing and clean water and are thus

forced to reside in camps that are highly susceptible to airborne and infectious ailments. Lastly,

the refugee unemployed may not be able to afford proper medication in the event that they fall

sick due to a lack of monies to fund their medication (Fisher et al., 2016).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

Most of the refugees in Australia use English as their second language with varying

levels of mastery of the same. Shishehgar et al. (2017) observe that some refugees especially

from West and Central Africa whom English is neither their first nor second language experience

a lot of difficulties when trying to access educational opportunities or health services in

Australia. With English being the language of instruction in Australia, the majority of refugees

opt not to attend Australian school because of the constraints involved in first learning the new

language before proceeding to their specific area of interest. With low literacy levels and

communication barriers already existing, most of these refugees miss out on opportunities to

attend school and gain much-needed health education and economic empowerment

(Nithianandan et al., 2016). Medical attendants also experience difficulties communicating with

the non-English speaking refugees without the services of an interpreter. With the refugee unable

to express oneself clearly to the medics, doctors may end up misinterpreting the symptoms and

giving wrong prescriptions that in some cases may turn out detrimental to the patient thus

making them even more vulnerable (Mahimbo et al., 2017).

Variations in health status among different groups of populations have been cited as one

of the factors contributing to the increased vulnerability of asylum seekers in Australia. Day

(2016) feels that health inequalities such as mortality and morbidity, healthy life expectancy,

differences in well-being, abuse and violence and risk of diseases put the lives of refugees at a

higher propensity of susceptibility. de Bocanegra et al. (2018) cite violence, abuse, and brutality

as one of the major stressors affecting mostly the mental health of refugees not only in Australia

but across the globe. Major, Dovidio, and Link (2018) claim that refugees who have been

through traumatic experiences in their native country are highly vulnerable to developing

psychological problems such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This reflection is

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

Most of the refugees in Australia use English as their second language with varying

levels of mastery of the same. Shishehgar et al. (2017) observe that some refugees especially

from West and Central Africa whom English is neither their first nor second language experience

a lot of difficulties when trying to access educational opportunities or health services in

Australia. With English being the language of instruction in Australia, the majority of refugees

opt not to attend Australian school because of the constraints involved in first learning the new

language before proceeding to their specific area of interest. With low literacy levels and

communication barriers already existing, most of these refugees miss out on opportunities to

attend school and gain much-needed health education and economic empowerment

(Nithianandan et al., 2016). Medical attendants also experience difficulties communicating with

the non-English speaking refugees without the services of an interpreter. With the refugee unable

to express oneself clearly to the medics, doctors may end up misinterpreting the symptoms and

giving wrong prescriptions that in some cases may turn out detrimental to the patient thus

making them even more vulnerable (Mahimbo et al., 2017).

Variations in health status among different groups of populations have been cited as one

of the factors contributing to the increased vulnerability of asylum seekers in Australia. Day

(2016) feels that health inequalities such as mortality and morbidity, healthy life expectancy,

differences in well-being, abuse and violence and risk of diseases put the lives of refugees at a

higher propensity of susceptibility. de Bocanegra et al. (2018) cite violence, abuse, and brutality

as one of the major stressors affecting mostly the mental health of refugees not only in Australia

but across the globe. Major, Dovidio, and Link (2018) claim that refugees who have been

through traumatic experiences in their native country are highly vulnerable to developing

psychological problems such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This reflection is

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

reiterated by Hirani, Payne, Mutch, and Cherian (2019) who notice that most migrant patients in

Australia present with typical symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder that affect how they

relate and associate with both the fellow refugees and host residents. Cullen et al. (2018) add that

poor living conditions and ardors journeys cause a myriad of health challenges and access to

primary healthcare is exceedingly difficult for those on the move. This difficulty in managing

infectious ailments implies that some asylum seekers do not get appropriate treatment which may

culminate into long term complications that significantly affect their health.

Several health inequities such as access to basic healthcare and affordability of the same

are considered another factor that makes refugee populations more vulnerable to health

complications than others. With limited opportunities for employment and stringent labor laws in

the host country, immigrants are left with wobbly means of raising enough income to cater for

their treatment and other basic needs such as proper diet (Priest et al., 2016). Access to

Australia’s insurance schemes is also made difficult due to cost implications and laborious

authentication process and paperwork needed especially from the migrant populations. Lack of

employment and refugee status makes it even more difficult for refugees to acquire these covers.

Consequently, the migrants are forced to rely on the host country’s provided healthcare services

for the refugees which is obviously not enough to meet their individual needs (Roche et al.,

2015).

The vulnerability in access to healthcare services has led to several negative health

outcomes among the refugee populations in Australia. As Tiong et al. (2006) discern,

populations are grappling with a trifle of health issues such as inadequate vaccinations, incessant

outbreaks and spread of infectious diseases such as latent tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, and

gastrointestinal infections. According to Tiong et al. (2006), out of the 258 refugee patients

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

reiterated by Hirani, Payne, Mutch, and Cherian (2019) who notice that most migrant patients in

Australia present with typical symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder that affect how they

relate and associate with both the fellow refugees and host residents. Cullen et al. (2018) add that

poor living conditions and ardors journeys cause a myriad of health challenges and access to

primary healthcare is exceedingly difficult for those on the move. This difficulty in managing

infectious ailments implies that some asylum seekers do not get appropriate treatment which may

culminate into long term complications that significantly affect their health.

Several health inequities such as access to basic healthcare and affordability of the same

are considered another factor that makes refugee populations more vulnerable to health

complications than others. With limited opportunities for employment and stringent labor laws in

the host country, immigrants are left with wobbly means of raising enough income to cater for

their treatment and other basic needs such as proper diet (Priest et al., 2016). Access to

Australia’s insurance schemes is also made difficult due to cost implications and laborious

authentication process and paperwork needed especially from the migrant populations. Lack of

employment and refugee status makes it even more difficult for refugees to acquire these covers.

Consequently, the migrants are forced to rely on the host country’s provided healthcare services

for the refugees which is obviously not enough to meet their individual needs (Roche et al.,

2015).

The vulnerability in access to healthcare services has led to several negative health

outcomes among the refugee populations in Australia. As Tiong et al. (2006) discern,

populations are grappling with a trifle of health issues such as inadequate vaccinations, incessant

outbreaks and spread of infectious diseases such as latent tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, and

gastrointestinal infections. According to Tiong et al. (2006), out of the 258 refugee patients

6

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

tested for latent tuberculosis, 25% of them were confirmed positive. Most adults also exhibited

psychological, musculoskeletal and social problems which can be attributed to age, long

journeys, injuries sustained due to war, insufficient healthcare and trauma suffered both in their

home country and in the host nation.

Racial/Ethnic disparity ranks top among the health disparities affecting migrant

populations in Australia (Shepherd et al., 2018). The trio regret that despite the factors being

attributed to racial health disparity having been identified through research and archive literature,

little or no efforts have been done to mitigate these conditions. Further, the researchers argue that

the interaction of these factors has not been explored as it should leading to unsystematic and

uniformed approach to the little effort being done to mitigate them (Shepherd et al.,2018).

A wide range of literature documents the ethnic/racial healthcare disparities between the

racial minority who in this case are the refugees and asylum seekers and the majority who are the

host residents (Philbin et al. 2018). In what the investigators term as a health paradox, the

immigrant populations that arrive in Australia with a better status of wellbeing than average

resident Australians born lose the status privilege as time progresses. For instance, Mexican

émigrés living in Australia enter the country in a healthier status than average Australian but

within a span of 10 years, about 8 percent of them are seen to have poorer health condition as

compared to the average native. It is further witnessed that after 15 years, this percentage rises to

15, raising conerns over the nature of healthcare services provided to the refugees and the

support accorded by the international community to the host nation regarding the refugee welfare

(Priest et al., 2016).

Lack of economic support and insurance cover among the immigrant’s hints towards a

probable racial/ethnic disparity. While television stations have sign language interpreters to assist

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

tested for latent tuberculosis, 25% of them were confirmed positive. Most adults also exhibited

psychological, musculoskeletal and social problems which can be attributed to age, long

journeys, injuries sustained due to war, insufficient healthcare and trauma suffered both in their

home country and in the host nation.

Racial/Ethnic disparity ranks top among the health disparities affecting migrant

populations in Australia (Shepherd et al., 2018). The trio regret that despite the factors being

attributed to racial health disparity having been identified through research and archive literature,

little or no efforts have been done to mitigate these conditions. Further, the researchers argue that

the interaction of these factors has not been explored as it should leading to unsystematic and

uniformed approach to the little effort being done to mitigate them (Shepherd et al.,2018).

A wide range of literature documents the ethnic/racial healthcare disparities between the

racial minority who in this case are the refugees and asylum seekers and the majority who are the

host residents (Philbin et al. 2018). In what the investigators term as a health paradox, the

immigrant populations that arrive in Australia with a better status of wellbeing than average

resident Australians born lose the status privilege as time progresses. For instance, Mexican

émigrés living in Australia enter the country in a healthier status than average Australian but

within a span of 10 years, about 8 percent of them are seen to have poorer health condition as

compared to the average native. It is further witnessed that after 15 years, this percentage rises to

15, raising conerns over the nature of healthcare services provided to the refugees and the

support accorded by the international community to the host nation regarding the refugee welfare

(Priest et al., 2016).

Lack of economic support and insurance cover among the immigrant’s hints towards a

probable racial/ethnic disparity. While television stations have sign language interpreters to assist

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

the visually impaired during news broadcasts, Bostos and Yaradies (2018) lament that most

health facilities in Australia do not have special needs assistants and language interpreters. While

the natives easily and fluently express themselves to medics, the non-English speaking refugees

find it difficult to express themselves to the doctors since the host government does not provide

language interpreters. The communication barrier between the medics and the patients creates a

health crisis among the immigrants that is yet to be addressed by the government (Bostos &

Yaradies, 2018).

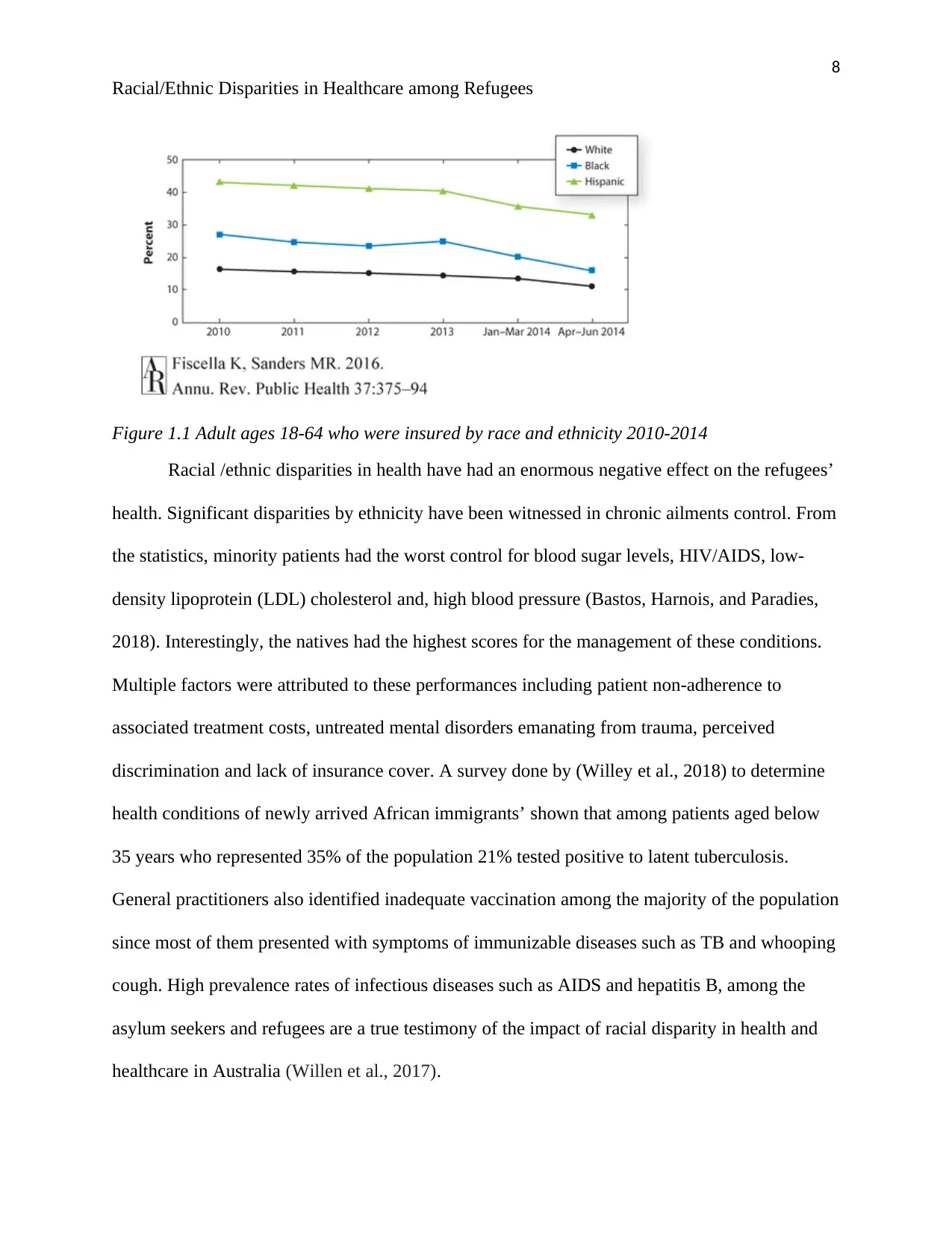

The Australian policy for protection has since early 90s restricted access to healthcare

services by refugees and asylum seekers with stringent conditions and terms to be fulfilled by the

applicant (Roche et al., 2015). While the natives have quick and efficient insurance cover

application and enrolment procedure, the immigrants are subjected to a lengthy and laborious

multiple-stage processes that only see a handful gain access to the country’s healthcare system.

While this paper is not blaming the country’s measures on security background, it is worth

noting that from a humanitarian background, much still needs to be achieved more so on access

to insurance policies. Fiscella and Sanders (2016) revealed that the majority of uninsured adults

between the age of 18 and 64 years were immigrants. According to their findings, blacks were

the least insured while Hispanic immigrants were the highest among the immigrants. However,

none of the immigrant groups had 50 % of its population insured as attested in Figure 1.1.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

the visually impaired during news broadcasts, Bostos and Yaradies (2018) lament that most

health facilities in Australia do not have special needs assistants and language interpreters. While

the natives easily and fluently express themselves to medics, the non-English speaking refugees

find it difficult to express themselves to the doctors since the host government does not provide

language interpreters. The communication barrier between the medics and the patients creates a

health crisis among the immigrants that is yet to be addressed by the government (Bostos &

Yaradies, 2018).

The Australian policy for protection has since early 90s restricted access to healthcare

services by refugees and asylum seekers with stringent conditions and terms to be fulfilled by the

applicant (Roche et al., 2015). While the natives have quick and efficient insurance cover

application and enrolment procedure, the immigrants are subjected to a lengthy and laborious

multiple-stage processes that only see a handful gain access to the country’s healthcare system.

While this paper is not blaming the country’s measures on security background, it is worth

noting that from a humanitarian background, much still needs to be achieved more so on access

to insurance policies. Fiscella and Sanders (2016) revealed that the majority of uninsured adults

between the age of 18 and 64 years were immigrants. According to their findings, blacks were

the least insured while Hispanic immigrants were the highest among the immigrants. However,

none of the immigrant groups had 50 % of its population insured as attested in Figure 1.1.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

Figure 1.1 Adult ages 18-64 who were insured by race and ethnicity 2010-2014

Racial /ethnic disparities in health have had an enormous negative effect on the refugees’

health. Significant disparities by ethnicity have been witnessed in chronic ailments control. From

the statistics, minority patients had the worst control for blood sugar levels, HIV/AIDS, low-

density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and, high blood pressure (Bastos, Harnois, and Paradies,

2018). Interestingly, the natives had the highest scores for the management of these conditions.

Multiple factors were attributed to these performances including patient non-adherence to

associated treatment costs, untreated mental disorders emanating from trauma, perceived

discrimination and lack of insurance cover. A survey done by (Willey et al., 2018) to determine

health conditions of newly arrived African immigrants’ shown that among patients aged below

35 years who represented 35% of the population 21% tested positive to latent tuberculosis.

General practitioners also identified inadequate vaccination among the majority of the population

since most of them presented with symptoms of immunizable diseases such as TB and whooping

cough. High prevalence rates of infectious diseases such as AIDS and hepatitis B, among the

asylum seekers and refugees are a true testimony of the impact of racial disparity in health and

healthcare in Australia (Willen et al., 2017).

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

Figure 1.1 Adult ages 18-64 who were insured by race and ethnicity 2010-2014

Racial /ethnic disparities in health have had an enormous negative effect on the refugees’

health. Significant disparities by ethnicity have been witnessed in chronic ailments control. From

the statistics, minority patients had the worst control for blood sugar levels, HIV/AIDS, low-

density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and, high blood pressure (Bastos, Harnois, and Paradies,

2018). Interestingly, the natives had the highest scores for the management of these conditions.

Multiple factors were attributed to these performances including patient non-adherence to

associated treatment costs, untreated mental disorders emanating from trauma, perceived

discrimination and lack of insurance cover. A survey done by (Willey et al., 2018) to determine

health conditions of newly arrived African immigrants’ shown that among patients aged below

35 years who represented 35% of the population 21% tested positive to latent tuberculosis.

General practitioners also identified inadequate vaccination among the majority of the population

since most of them presented with symptoms of immunizable diseases such as TB and whooping

cough. High prevalence rates of infectious diseases such as AIDS and hepatitis B, among the

asylum seekers and refugees are a true testimony of the impact of racial disparity in health and

healthcare in Australia (Willen et al., 2017).

9

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

The selected audience for this insight is the Bangladesh Rural and Advancement

Committee (BRAC) Australian chapter. BRAC is arguably the largest non-governmental

organization in the world with its headquarters in Dhaka, Bangladesh and reaches out to over

126million people across the planet. Established in 1972 the organization is said to employee

over 100000 people across the world and received over 212.7 million from AusAID (Gramling et

al., 2016). It is against this background that the author settled on BRAC as it is believed to

possess both financial and manpower capacity to address the issue of immigration racial

disparities. Although there are already existing mechanisms by several other organizations, this

paper assumes the position of a new initiative since the approach and strategies to be employed

herein are different from the normal. As such it is presumed that there is not even a single

resource allocated towards mitigating the racial disparity in Australian healthcare. In addition,

BRAC is an accredited NGO in Australia and has a reputation to influence the government

towards making adjustments to its existing policies on refugee healthcare (Salami et al., 2017).

This proposal, therefore, seeks to solicit for both financial and human resource support from the

exchequer.

In order to successfully execute the initiative, this paper suggests the approach of

working for and with the refugees. Since most of the problems affecting refugee healthcare

emanate from financial constraints, perhaps it is a time the NGO management considered

recruiting refugee nurses to work with its existing nursing personne. This will change the

dimension of the public towards them and in the long run, minimize the much haunting

discrimination and inequities. In addition, the organization management could think of

employing volunteer language interpreters in all of its facilities to aid the practitioners and

refugee communication. The interpreters could as well be the refugees themselves since we have

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

The selected audience for this insight is the Bangladesh Rural and Advancement

Committee (BRAC) Australian chapter. BRAC is arguably the largest non-governmental

organization in the world with its headquarters in Dhaka, Bangladesh and reaches out to over

126million people across the planet. Established in 1972 the organization is said to employee

over 100000 people across the world and received over 212.7 million from AusAID (Gramling et

al., 2016). It is against this background that the author settled on BRAC as it is believed to

possess both financial and manpower capacity to address the issue of immigration racial

disparities. Although there are already existing mechanisms by several other organizations, this

paper assumes the position of a new initiative since the approach and strategies to be employed

herein are different from the normal. As such it is presumed that there is not even a single

resource allocated towards mitigating the racial disparity in Australian healthcare. In addition,

BRAC is an accredited NGO in Australia and has a reputation to influence the government

towards making adjustments to its existing policies on refugee healthcare (Salami et al., 2017).

This proposal, therefore, seeks to solicit for both financial and human resource support from the

exchequer.

In order to successfully execute the initiative, this paper suggests the approach of

working for and with the refugees. Since most of the problems affecting refugee healthcare

emanate from financial constraints, perhaps it is a time the NGO management considered

recruiting refugee nurses to work with its existing nursing personne. This will change the

dimension of the public towards them and in the long run, minimize the much haunting

discrimination and inequities. In addition, the organization management could think of

employing volunteer language interpreters in all of its facilities to aid the practitioners and

refugee communication. The interpreters could as well be the refugees themselves since we have

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

some of them who are multilingual. Offering employment opportunities to refugees will go a

long way in mitigating racial discrimination and enhancing their economic status.

By allowing the organizations' Australian nurses to work with refugee nurses or

community health personnel, both BRAC and the Australian government stand to win big on the

war against ethnic/racial segregation in Australian health services. The government will gain an

opportunity to boost its already stretched healthcare workforce since most of the refugee

healthcare services are not usually part of the government’s healthcare workforce plan. Of all the

winners in this arrangement, the greatest of them is the medical practitioners from the host

country moreso the nurses working with the refugee nurses. The nurses will get an opportunity to

share knowledge and experiences with foreign nurses thus practising in line to standard 2.7 of the

Australia’s nursing and midwifery board professional standards for registered nurse which

provides that a registered nurse “actively fosters a culture of safety and learning that includes

engaging with health professionals and others, to share knowledge and practice that supports

person-centered care”. By working with nursing from different professional and cultural

background, the native nurses will have a rare opportunity to appreciate the practice of nursing

from different cultural background as provided for in standard 1.3 that requires nursing personnel

to respect all cultures and experiences for the people they are offering support to and colleagues.

Besides, this integration will foster cohesion among the natives and the immigrants thus

gradually changing the perception of the public towards the refugees and in the long run avert

ethnic/racial disparities in healthcare.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

some of them who are multilingual. Offering employment opportunities to refugees will go a

long way in mitigating racial discrimination and enhancing their economic status.

By allowing the organizations' Australian nurses to work with refugee nurses or

community health personnel, both BRAC and the Australian government stand to win big on the

war against ethnic/racial segregation in Australian health services. The government will gain an

opportunity to boost its already stretched healthcare workforce since most of the refugee

healthcare services are not usually part of the government’s healthcare workforce plan. Of all the

winners in this arrangement, the greatest of them is the medical practitioners from the host

country moreso the nurses working with the refugee nurses. The nurses will get an opportunity to

share knowledge and experiences with foreign nurses thus practising in line to standard 2.7 of the

Australia’s nursing and midwifery board professional standards for registered nurse which

provides that a registered nurse “actively fosters a culture of safety and learning that includes

engaging with health professionals and others, to share knowledge and practice that supports

person-centered care”. By working with nursing from different professional and cultural

background, the native nurses will have a rare opportunity to appreciate the practice of nursing

from different cultural background as provided for in standard 1.3 that requires nursing personnel

to respect all cultures and experiences for the people they are offering support to and colleagues.

Besides, this integration will foster cohesion among the natives and the immigrants thus

gradually changing the perception of the public towards the refugees and in the long run avert

ethnic/racial disparities in healthcare.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

References

Bastos, J. L., Harnois, C. E., & Paradies, Y. C. (2018). Health care barriers, racism, and

intersectionality in Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 209-218.

Cullen, P., Clapham, K., Hunter, K., Porykali, B., & Ivers, R. (2018). PW 1898 Embedding

multi-sectoral solutions to address transport injury and social determinants of health in

aboriginal communities in australia.

Day, G. E. (2016). Migrant and Refugee Health: Advance Australia Fair?. Australian Health

Review, 40(1), 1-2.

de Bocanegra, H. T., Carter-Pokras, O., Ingleby, J. D., Pottie, K., Tchangalova, N., Allen, S.

I., ... & Hidalgo, B. (2018). Addressing refugee health through evidence-based policies: a

case study. Annals of epidemiology, 28(6), 411-419.

Fiscella, K., & Sanders, M. R. (2016). Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of health

care. Annual review of public health, 37, 375-394.

Fisher, M., Baum, F. E., MacDougall, C., Newman, L., & McDermott, D. (2016). To what extent

do Australian health policy documents address social determinants of health and health

equity?. Journal of Social Policy, 45(3), 545-564.

Gramling, R., Fiscella, K., Xing, G., Hoerger, M., Duberstein, P., Plumb, S., & Epstein, R. M.

(2016). Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced

cancer. JAMA oncology, 2(11), 1421-1426.

Hirani, K., Payne, D. N., Mutch, R., & Cherian, S. (2019). Medical needs of adolescent refugees

resettling in Western Australia. Archives of disease in childhood, 104(9), 880-883.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

References

Bastos, J. L., Harnois, C. E., & Paradies, Y. C. (2018). Health care barriers, racism, and

intersectionality in Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 209-218.

Cullen, P., Clapham, K., Hunter, K., Porykali, B., & Ivers, R. (2018). PW 1898 Embedding

multi-sectoral solutions to address transport injury and social determinants of health in

aboriginal communities in australia.

Day, G. E. (2016). Migrant and Refugee Health: Advance Australia Fair?. Australian Health

Review, 40(1), 1-2.

de Bocanegra, H. T., Carter-Pokras, O., Ingleby, J. D., Pottie, K., Tchangalova, N., Allen, S.

I., ... & Hidalgo, B. (2018). Addressing refugee health through evidence-based policies: a

case study. Annals of epidemiology, 28(6), 411-419.

Fiscella, K., & Sanders, M. R. (2016). Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of health

care. Annual review of public health, 37, 375-394.

Fisher, M., Baum, F. E., MacDougall, C., Newman, L., & McDermott, D. (2016). To what extent

do Australian health policy documents address social determinants of health and health

equity?. Journal of Social Policy, 45(3), 545-564.

Gramling, R., Fiscella, K., Xing, G., Hoerger, M., Duberstein, P., Plumb, S., & Epstein, R. M.

(2016). Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced

cancer. JAMA oncology, 2(11), 1421-1426.

Hirani, K., Payne, D. N., Mutch, R., & Cherian, S. (2019). Medical needs of adolescent refugees

resettling in Western Australia. Archives of disease in childhood, 104(9), 880-883.

12

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

Mahimbo, A., Seale, H., Smith, M., & Heywood, A. (2017). Challenges in immunisation service

delivery for refugees in Australia: a health system perspective. Vaccine, 35(38), 5148-

5155.

Major, B., Dovidio, J. F., & Link, B. G. (Eds.). (2018). The oxford handbook of stigma,

discrimination, and health. Oxford University Press.

Nithianandan, N., Gibson-Helm, M., McBride, J., Binny, A., Gray, K. M., East, C., & Boyle, J.

A. (2016). Factors affecting implementation of perinatal mental health screening in women

of refugee background. Implementation Science, 11(1), 150.

Philbin, M. M., Flake, M., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Hirsch, J. S. (2018). State-level immigration

and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United

States. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 29-38.

Priest, N., King, T., Bécares, L., & Kavanagh, A. M. (2016). Bullying victimization and racial

discrimination among Australian children. American journal of public health, 106(10),

1882-1884.

Roche, A., Kostadinov, V., Fischer, J., & Nicholas, R. (2015). Evidence review: The social

determinants of inequities in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health

outcomes. Australian's National Research Centre on AOD Workforce Development and

Flinders University.

Salami, B., Yaskina, M., Hegadoren, K., Diaz, E., Meherali, S., Rammohan, A., & Ben-Shlomo,

Y. (2017). Migration and social determinants of mental health: results from the Canadian

health measures survey. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 108(4), 362-367.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare among Refugees

Mahimbo, A., Seale, H., Smith, M., & Heywood, A. (2017). Challenges in immunisation service

delivery for refugees in Australia: a health system perspective. Vaccine, 35(38), 5148-

5155.

Major, B., Dovidio, J. F., & Link, B. G. (Eds.). (2018). The oxford handbook of stigma,

discrimination, and health. Oxford University Press.

Nithianandan, N., Gibson-Helm, M., McBride, J., Binny, A., Gray, K. M., East, C., & Boyle, J.

A. (2016). Factors affecting implementation of perinatal mental health screening in women

of refugee background. Implementation Science, 11(1), 150.

Philbin, M. M., Flake, M., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Hirsch, J. S. (2018). State-level immigration

and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United

States. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 29-38.

Priest, N., King, T., Bécares, L., & Kavanagh, A. M. (2016). Bullying victimization and racial

discrimination among Australian children. American journal of public health, 106(10),

1882-1884.

Roche, A., Kostadinov, V., Fischer, J., & Nicholas, R. (2015). Evidence review: The social

determinants of inequities in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health

outcomes. Australian's National Research Centre on AOD Workforce Development and

Flinders University.

Salami, B., Yaskina, M., Hegadoren, K., Diaz, E., Meherali, S., Rammohan, A., & Ben-Shlomo,

Y. (2017). Migration and social determinants of mental health: results from the Canadian

health measures survey. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 108(4), 362-367.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.