Using realist synthesis to understand the mechanisms of interprofessional teamwork in health and social care

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|7

|7593

|384

AI Summary

This article introduces realist synthesis and its approach to identifying and testing the underpinning processes (or mechanisms) that make an intervention work, the contexts that trigger those mechanisms and their subsequent outcomes. A realist synthesis of the evidence on interprofessional teamwork is described. Thirteen mechanisms were identified in the synthesis and findings for one mechanism, called ‘‘Support and value’’ are presented in this paper.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

http://informahealthcare.com/jic

ISSN:1356-1820 (print),1469-9567 (electronic)

J Interprof Care,2014;28(6):501–506

! 2014 Informa UK Ltd.DOI:10.3109/13561820.2014.939744

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Using realist synthesis to understand the mechanisms of

interprofessionalteamwork in health and social care

Gillian Hewitt1, Sarah Sims2 and Ruth Harris2

1Cardiff Schoolof SocialSciences,Cardiff University,Cardiff,UK and2Faculty of Health,SocialCare and Education,Kingston University and

St George’s,University of London,Kingston Upon Thames,Surrey,UK

Abstract

Realistsynthesisoffersa novel and innovative way to interrogate the large literature on

interprofessionalteamwork in health and socialcare teams.This article introducesrealist

synthesisand its approach to identifying and testing theunderpinning processes(or

‘‘mechanisms’’)that make an intervention work,the contexts that trigger those mechanisms

and their subsequentoutcomes.A realist synthesisof the evidence on interprofessional

teamwork is described.Thirteen mechanisms were identified in the synthesis and findings for

one mechanism,called ‘‘Support and value’’are presented in this paper.The evidence for the

other twelve mechanisms (‘‘collaboration and coordination’’, ‘‘pooling of resources’’, ‘‘individual

learning’’,‘‘role blurring’’,‘‘efficient,open and equitable communication’’,‘‘tacticalcommuni-

cation’’, ‘‘shared responsibility and influence’’, ‘‘team behavioural norms’’, ‘‘shared responsibility

and influence’’,‘‘critically reviewing performance and decisions’’,‘‘generating and implement-

ing new ideas’’and ‘‘leadership’’)are reported in a furtherthree papers in this series.The

‘‘support and value’’mechanism referred to the ways in which team members supported one

another,respected other’s skills and abilities and valued each other’s contributions.‘‘Support

and value’’was presentin some,but far from all,teams and a numberof contexts that

explained thisvariation were identified.The article concludeswith a discussion of the

challenges and benefits of undertaking this realist synthesis.

Keywords

Interprofessionalpractice,realist synthesis,

teamwork

History

Received 5 November 2013

Revised 20 February 2014

Accepted 25 June 2014

Published online 21 July 2014

Introduction

Interprofessionalteams are a common feature of modern health

and social care,where they are perceived as a means to enhance

care quality and efficiency and patientsafety and therefore

strongly advocated within the healthcare policy of many countries

(Reeves,Lewin, Espin, & Zwarenstein,2010).Increasingly,

patientshave complex and long term conditionsthatrequire

treatments from a range of health professionals and good quality

care is dependent upon those professionals collaborating together

in teams.Although there are numerous definitions of ‘‘teams’’,

a generalconsensus exists thatthey are ‘‘comprised of a small,

manageable number of members with an appropriate mix of skills

and expertise, who are all committed to a meaningful purpose and

have collective responsibility to achieve performance objectives

and outcomes’’(Harriset al., 2013,p. 22). A large body of

research on interprofessional teamwork exists,much of which is

descriptive and unempirical(Reeves etal., 2010).Furthermore,

the rapidly changing health and social care landscape in the UK

means the need persists for innovative research thatwill inform

the developmentand managementof increasinglycomplex

interprofessionalteams.The authorsand colleaguestherefore

adopted therealistapproach (Pawson & Tilley,1997)in a

multi-method study ofinterprofessionalteamwork along the

stroke care pathway (the Teams Study) (Harris et al.,2013).

The realistapproach wasdeveloped to evaluatecomplex

social interventions,namelyprogrammesthat offer one or

moreresources,but depend upon people’sresponsesto the

resourceto generatethe anticipatedoutcomes(Pawson,

Greenhalgh,Harvey,& Walshe,2005).Interprofessionalteam-

work was considered to be a complex social intervention becau

it provides individual professionals with a resource (the team a

its members),butthe impacts of teamwork depend on the ways

in which individualsrespond to theirteam membership.For

example,therapists and nurses might respond to being in a team

together by sharing their knowledge of a patient more frequent

or in greaterdepth.Such a responseis referredto as a

‘‘mechanism’’and realist researchersseek to identify the

mechanismsthat underpin complex social interventions.

Contexts thatdetermine whetheror notmechanisms are ‘‘trig-

gered’’ for particular groups of people or in particular situations

are also identified,along with context-dependentoutcomes.

Context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations can then be

generated and used to address the realist question of, ‘‘What is

about teamwork that works for whom, in what circumstances a

why?’’(Pawson etal., 2005).This novelway ofinterrogating

interprofessional teamwork was used to identify the mechanism

of teamwork,thereby creating a conceptualframework foruse

in this study and others. As far as we are aware, this is the first

of the realistsynthesis method in the teamwork literature and

builds on earlier work with the method undertaken by Hammick

Correspondence:Professor Ruth Harris,Faculty of Health,SocialCare

and Education,Kingston University and StGeorge’s,University of

London,Kingston Hill Campus,Kingston Upon Thames,KT2 7LB,

Surrey,UK. E-mail: Ruth.Harris@sgul.kingston.ac.uk

ISSN:1356-1820 (print),1469-9567 (electronic)

J Interprof Care,2014;28(6):501–506

! 2014 Informa UK Ltd.DOI:10.3109/13561820.2014.939744

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Using realist synthesis to understand the mechanisms of

interprofessionalteamwork in health and social care

Gillian Hewitt1, Sarah Sims2 and Ruth Harris2

1Cardiff Schoolof SocialSciences,Cardiff University,Cardiff,UK and2Faculty of Health,SocialCare and Education,Kingston University and

St George’s,University of London,Kingston Upon Thames,Surrey,UK

Abstract

Realistsynthesisoffersa novel and innovative way to interrogate the large literature on

interprofessionalteamwork in health and socialcare teams.This article introducesrealist

synthesisand its approach to identifying and testing theunderpinning processes(or

‘‘mechanisms’’)that make an intervention work,the contexts that trigger those mechanisms

and their subsequentoutcomes.A realist synthesisof the evidence on interprofessional

teamwork is described.Thirteen mechanisms were identified in the synthesis and findings for

one mechanism,called ‘‘Support and value’’are presented in this paper.The evidence for the

other twelve mechanisms (‘‘collaboration and coordination’’, ‘‘pooling of resources’’, ‘‘individual

learning’’,‘‘role blurring’’,‘‘efficient,open and equitable communication’’,‘‘tacticalcommuni-

cation’’, ‘‘shared responsibility and influence’’, ‘‘team behavioural norms’’, ‘‘shared responsibility

and influence’’,‘‘critically reviewing performance and decisions’’,‘‘generating and implement-

ing new ideas’’and ‘‘leadership’’)are reported in a furtherthree papers in this series.The

‘‘support and value’’mechanism referred to the ways in which team members supported one

another,respected other’s skills and abilities and valued each other’s contributions.‘‘Support

and value’’was presentin some,but far from all,teams and a numberof contexts that

explained thisvariation were identified.The article concludeswith a discussion of the

challenges and benefits of undertaking this realist synthesis.

Keywords

Interprofessionalpractice,realist synthesis,

teamwork

History

Received 5 November 2013

Revised 20 February 2014

Accepted 25 June 2014

Published online 21 July 2014

Introduction

Interprofessionalteams are a common feature of modern health

and social care,where they are perceived as a means to enhance

care quality and efficiency and patientsafety and therefore

strongly advocated within the healthcare policy of many countries

(Reeves,Lewin, Espin, & Zwarenstein,2010).Increasingly,

patientshave complex and long term conditionsthatrequire

treatments from a range of health professionals and good quality

care is dependent upon those professionals collaborating together

in teams.Although there are numerous definitions of ‘‘teams’’,

a generalconsensus exists thatthey are ‘‘comprised of a small,

manageable number of members with an appropriate mix of skills

and expertise, who are all committed to a meaningful purpose and

have collective responsibility to achieve performance objectives

and outcomes’’(Harriset al., 2013,p. 22). A large body of

research on interprofessional teamwork exists,much of which is

descriptive and unempirical(Reeves etal., 2010).Furthermore,

the rapidly changing health and social care landscape in the UK

means the need persists for innovative research thatwill inform

the developmentand managementof increasinglycomplex

interprofessionalteams.The authorsand colleaguestherefore

adopted therealistapproach (Pawson & Tilley,1997)in a

multi-method study ofinterprofessionalteamwork along the

stroke care pathway (the Teams Study) (Harris et al.,2013).

The realistapproach wasdeveloped to evaluatecomplex

social interventions,namelyprogrammesthat offer one or

moreresources,but depend upon people’sresponsesto the

resourceto generatethe anticipatedoutcomes(Pawson,

Greenhalgh,Harvey,& Walshe,2005).Interprofessionalteam-

work was considered to be a complex social intervention becau

it provides individual professionals with a resource (the team a

its members),butthe impacts of teamwork depend on the ways

in which individualsrespond to theirteam membership.For

example,therapists and nurses might respond to being in a team

together by sharing their knowledge of a patient more frequent

or in greaterdepth.Such a responseis referredto as a

‘‘mechanism’’and realist researchersseek to identify the

mechanismsthat underpin complex social interventions.

Contexts thatdetermine whetheror notmechanisms are ‘‘trig-

gered’’ for particular groups of people or in particular situations

are also identified,along with context-dependentoutcomes.

Context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations can then be

generated and used to address the realist question of, ‘‘What is

about teamwork that works for whom, in what circumstances a

why?’’(Pawson etal., 2005).This novelway ofinterrogating

interprofessional teamwork was used to identify the mechanism

of teamwork,thereby creating a conceptualframework foruse

in this study and others. As far as we are aware, this is the first

of the realistsynthesis method in the teamwork literature and

builds on earlier work with the method undertaken by Hammick

Correspondence:Professor Ruth Harris,Faculty of Health,SocialCare

and Education,Kingston University and StGeorge’s,University of

London,Kingston Hill Campus,Kingston Upon Thames,KT2 7LB,

Surrey,UK. E-mail: Ruth.Harris@sgul.kingston.ac.uk

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Freeth,Koppel,Reeves,and Barr(2007)on interprofessional

education.

This article introducesthe realistapproachto evidence

synthesis and describes the realistsynthesis undertaken forthe

Teams Study.It presents findings for one mechanism (‘‘support

and value’’)as an example and concludes with reflections on

the process of undertaking a realist synthesis.This is the first in

a seriesof four articlesreporting the findingsof the realist

synthesis.The secondarticle reportsthe findingsfor the

‘‘collaborationand coordination’’,‘‘pooling of resources’’,

Individuallearning’’and ‘‘role blurring’’mechanisms(Sims,

Hewitt,& Harris, in press a). The third articlereportsthe

‘‘efficient,open and equitable communication’’,‘‘tacticalcom-

munication’’,‘‘shared responsibility and influence’’ and ‘‘team

behaviouralnorms’’mechanisms(Hewitt,Sims,& Harris, in

press). The fourth and final article reports ‘‘shared responsibility

and influence’’,‘‘critically reviewing performanceand deci-

sions’’,‘‘generating and implementing new ideas’’ and ‘‘leader-

ship’’ mechanisms drawing overall conclusions from the findings

of the synthesis and their implications for healthcare delivery and

further research (Sims,Hewitt, & Harris,in press b).

Realist synthesis

Realistsynthesis identifies and tests CMO configurations using

evidence from the literature.For a comprehensive description

readers are referred to Pawson,Greenhalgh,Harvey,and Walshe

(2004).Briefly,realist synthesis:

Identifies the mechanisms thatprogramme designers thought

would underpin the intervention.

Tests those mechanisms using empiricalevidence from the

literature.

Identifies and tests other,unforeseen mechanisms thatmight

underpin the intervention once it is implemented.

Explores which contexts ‘‘trigger’’ the mechanisms for which

people and in which circumstances.

Identifies positive and negative outcomes of the intervention,

depending on which contextsand mechanismsare present

(CMO configurations).

Synthesisesthe evidence in orderto refine the theory the

intervention rests on.

Realist synthesis is a more flexible and iterative process than

conventional systematic review. Its focus, for example, is directed

by the emerging evidence rather than being tightly defined at the

outset and the reviewer iteratively develops the search strategy as

the review progresses, meaning multiple, responsive searches are

conducted.There are,however,two main stages to the search

process.The first identifiesthe purportedmechanismsthat

underpin the intervention,using diverse sources such as policy

documents,editorials,otherreviewsand interviewswith key

informants. The second looks for empirical evidence that supports

or refutes the mechanisms.The reviewer now looks for contexts

thattriggerthe purported mechanisms and the outcomesthey

generate and also looksfor unforeseen mechanismsand their

associated contexts and outcomes.

Anotherarea in which realistsynthesis differs significantly

from conventional systematic review is in its approach to quality

appraisalof potentially relevantstudies.Instead ofassessing

methodologicalquality and judging a study’s acceptability for

inclusion on that basis, the realist reviewer looks at the quality of

the inference the author is making from their data and asks if their

inference makes a credible contribution to the mechanism being

tested (see Pawson,2006 forfurtherdetail).Realistsynthesis

thereforedrawson a much wider rangeof evidencethan

conventionalsystematic review and makes criticaland cautious

use of ‘‘methodologically weak’’ studies.

Methods

The realist synthesis,conducted in 2008–2010, aimed to identify

and explore the mechanisms of interprofessionalteamwork.The

initial review question was:‘‘Through whatmechanisms does

interprofessionalteam workingaffectclinical outcomesand

patientexperience,and how does contextinfluencethose

mechanisms?’’

The first stagesearch strategy (TableI), to identify the

purportedmechanismsof teamwork,was run throughthe

electronicdatabasesAMED, CINAHL, MEDLINE and IBSS

with the English language limiter. The resulting 301 records we

screened by the authors, who read any potentially relevant arti

in full. This included any type ofarticle (theoretical,opinion,

research,etc) thatfocused on the functioning orbenefitsof

interprofessionalteams in health and socialcare.Recenthealth

policy documents were also read. Each author then independen

identified provisional mechanisms of interprofessional teamwor

Discussion with the research team and study advisory group

which included senior academics and clinicians from a range of

disciplines including socialscience,psychology,physiotherapy

and nursing,on the meaning of ‘‘mechanism’’,led to the review

question being modified slightly to ‘‘Through what mechanisms

does team working affect outcomes and experience (patient, ca

staff and service),and how does contextinfluencethose

mechanismsand outcomes?’’The authorsthen pooled their

provisional mechanisms and agreed and defined nine (Table II)

These were circulated to the advisory group who, on the basis o

their research expertise in teamwork,suggested a tenth mechan-

ism of ‘‘Leadership’’.

The second stage search aimed to identify empirical evidenc

that could be used to testthe ten provisionalmechanisms.

Additional mechanisms were also sought.A new search strategy

was developed,using free text termsand subjectheadings

appropriate foreach database.The search combined terms for

inter/multi/trans-disciplinary or -professional with terms for tea

and teamwork and with health-related terms such as rehabilita

and community care.English language and study type limiters

were used.A furtherfour electronic databases were included:

HMIC, Psychinfo,ASSIA and Scopus.

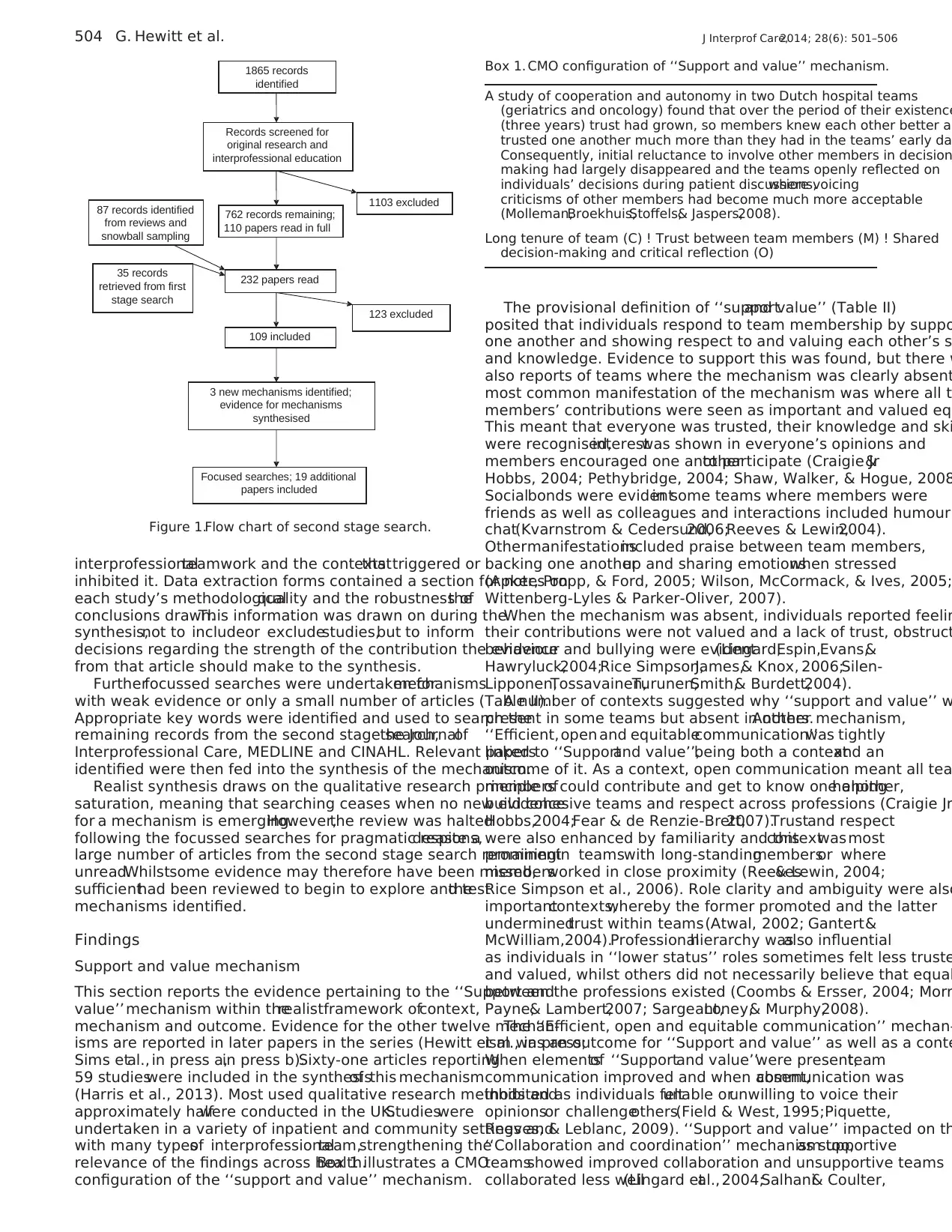

Searchesretrieved 1865 records,which were screened for

reports of originalresearch on teams thatcared for adultclient

groups.Recordswhere thisinformation wasambiguouswere

retained.Studies of pre-qualification interprofessionaleducation

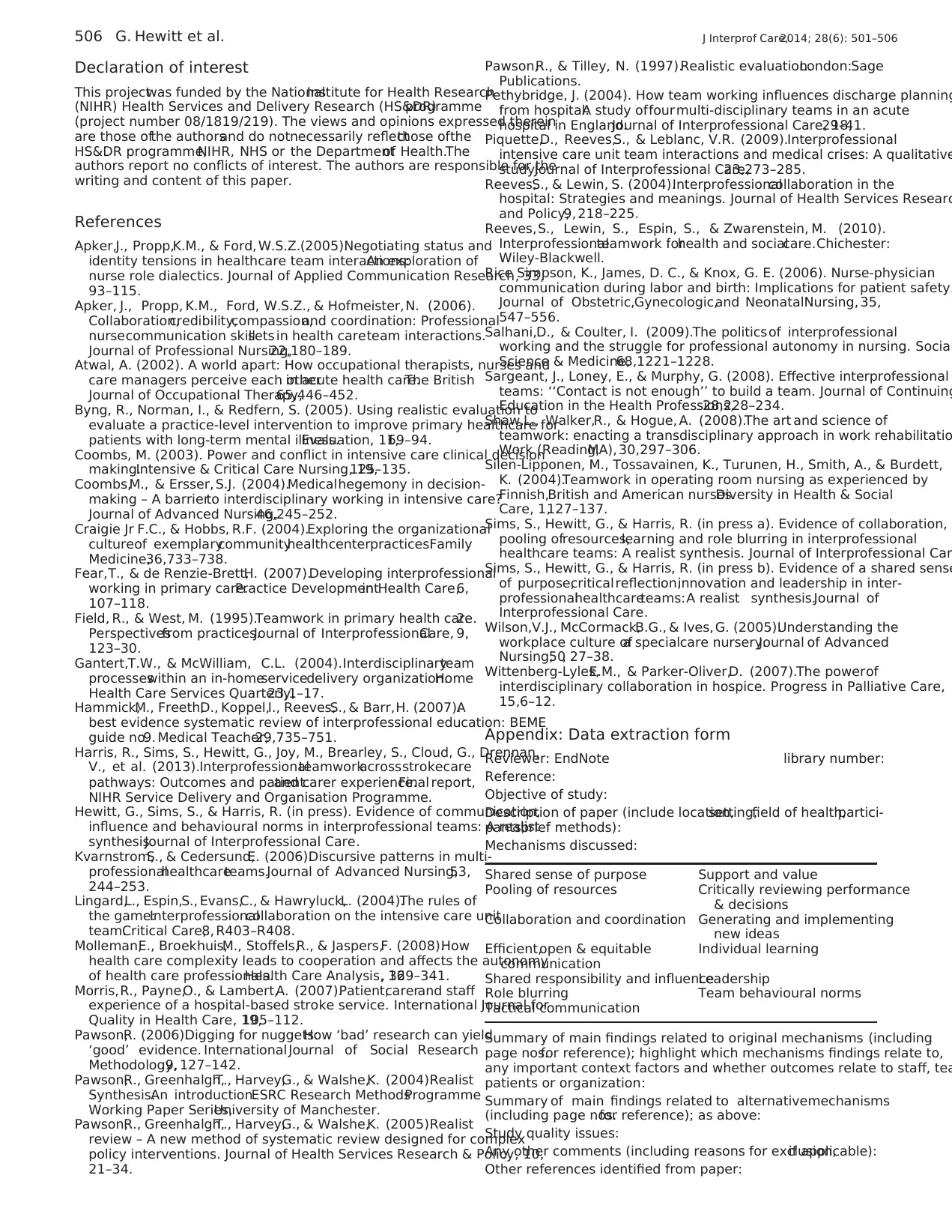

were excluded.A total of 762 records remained (Figure 1).

Originalresearch studiesfrom the firststage search were

retrieved,along with any relevant reviews.Reference lists of the

latter were screened and potentially relevanttitles followed up.

Further, snowball sampling was undertaken throughout the rev

whereby thereferencelist of every articleread in full was

screened for further relevant articles.

Two of the authors began reading the collected articles in ful

Detailed inclusion criteria were notapplied,butarticles had to

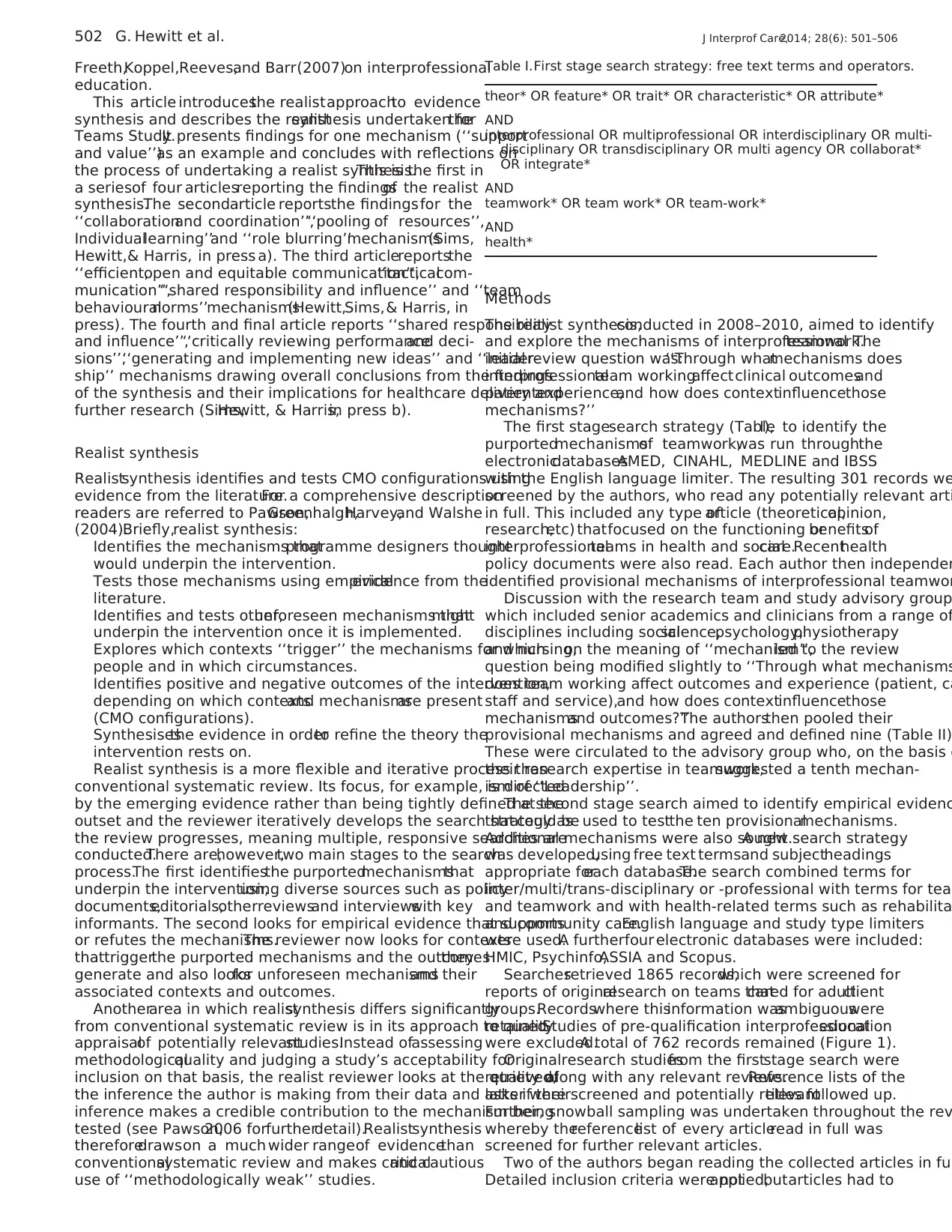

Table I.First stage search strategy: free text terms and operators.

theor* OR feature* OR trait* OR characteristic* OR attribute*

AND

interprofessional OR multiprofessional OR interdisciplinary OR multi-

disciplinary OR transdisciplinary OR multi agency OR collaborat*

OR integrate*

AND

teamwork* OR team work* OR team-work*

AND

health*

502 G. Hewitt et al. J Interprof Care,2014; 28(6): 501–506

education.

This article introducesthe realistapproachto evidence

synthesis and describes the realistsynthesis undertaken forthe

Teams Study.It presents findings for one mechanism (‘‘support

and value’’)as an example and concludes with reflections on

the process of undertaking a realist synthesis.This is the first in

a seriesof four articlesreporting the findingsof the realist

synthesis.The secondarticle reportsthe findingsfor the

‘‘collaborationand coordination’’,‘‘pooling of resources’’,

Individuallearning’’and ‘‘role blurring’’mechanisms(Sims,

Hewitt,& Harris, in press a). The third articlereportsthe

‘‘efficient,open and equitable communication’’,‘‘tacticalcom-

munication’’,‘‘shared responsibility and influence’’ and ‘‘team

behaviouralnorms’’mechanisms(Hewitt,Sims,& Harris, in

press). The fourth and final article reports ‘‘shared responsibility

and influence’’,‘‘critically reviewing performanceand deci-

sions’’,‘‘generating and implementing new ideas’’ and ‘‘leader-

ship’’ mechanisms drawing overall conclusions from the findings

of the synthesis and their implications for healthcare delivery and

further research (Sims,Hewitt, & Harris,in press b).

Realist synthesis

Realistsynthesis identifies and tests CMO configurations using

evidence from the literature.For a comprehensive description

readers are referred to Pawson,Greenhalgh,Harvey,and Walshe

(2004).Briefly,realist synthesis:

Identifies the mechanisms thatprogramme designers thought

would underpin the intervention.

Tests those mechanisms using empiricalevidence from the

literature.

Identifies and tests other,unforeseen mechanisms thatmight

underpin the intervention once it is implemented.

Explores which contexts ‘‘trigger’’ the mechanisms for which

people and in which circumstances.

Identifies positive and negative outcomes of the intervention,

depending on which contextsand mechanismsare present

(CMO configurations).

Synthesisesthe evidence in orderto refine the theory the

intervention rests on.

Realist synthesis is a more flexible and iterative process than

conventional systematic review. Its focus, for example, is directed

by the emerging evidence rather than being tightly defined at the

outset and the reviewer iteratively develops the search strategy as

the review progresses, meaning multiple, responsive searches are

conducted.There are,however,two main stages to the search

process.The first identifiesthe purportedmechanismsthat

underpin the intervention,using diverse sources such as policy

documents,editorials,otherreviewsand interviewswith key

informants. The second looks for empirical evidence that supports

or refutes the mechanisms.The reviewer now looks for contexts

thattriggerthe purported mechanisms and the outcomesthey

generate and also looksfor unforeseen mechanismsand their

associated contexts and outcomes.

Anotherarea in which realistsynthesis differs significantly

from conventional systematic review is in its approach to quality

appraisalof potentially relevantstudies.Instead ofassessing

methodologicalquality and judging a study’s acceptability for

inclusion on that basis, the realist reviewer looks at the quality of

the inference the author is making from their data and asks if their

inference makes a credible contribution to the mechanism being

tested (see Pawson,2006 forfurtherdetail).Realistsynthesis

thereforedrawson a much wider rangeof evidencethan

conventionalsystematic review and makes criticaland cautious

use of ‘‘methodologically weak’’ studies.

Methods

The realist synthesis,conducted in 2008–2010, aimed to identify

and explore the mechanisms of interprofessionalteamwork.The

initial review question was:‘‘Through whatmechanisms does

interprofessionalteam workingaffectclinical outcomesand

patientexperience,and how does contextinfluencethose

mechanisms?’’

The first stagesearch strategy (TableI), to identify the

purportedmechanismsof teamwork,was run throughthe

electronicdatabasesAMED, CINAHL, MEDLINE and IBSS

with the English language limiter. The resulting 301 records we

screened by the authors, who read any potentially relevant arti

in full. This included any type ofarticle (theoretical,opinion,

research,etc) thatfocused on the functioning orbenefitsof

interprofessionalteams in health and socialcare.Recenthealth

policy documents were also read. Each author then independen

identified provisional mechanisms of interprofessional teamwor

Discussion with the research team and study advisory group

which included senior academics and clinicians from a range of

disciplines including socialscience,psychology,physiotherapy

and nursing,on the meaning of ‘‘mechanism’’,led to the review

question being modified slightly to ‘‘Through what mechanisms

does team working affect outcomes and experience (patient, ca

staff and service),and how does contextinfluencethose

mechanismsand outcomes?’’The authorsthen pooled their

provisional mechanisms and agreed and defined nine (Table II)

These were circulated to the advisory group who, on the basis o

their research expertise in teamwork,suggested a tenth mechan-

ism of ‘‘Leadership’’.

The second stage search aimed to identify empirical evidenc

that could be used to testthe ten provisionalmechanisms.

Additional mechanisms were also sought.A new search strategy

was developed,using free text termsand subjectheadings

appropriate foreach database.The search combined terms for

inter/multi/trans-disciplinary or -professional with terms for tea

and teamwork and with health-related terms such as rehabilita

and community care.English language and study type limiters

were used.A furtherfour electronic databases were included:

HMIC, Psychinfo,ASSIA and Scopus.

Searchesretrieved 1865 records,which were screened for

reports of originalresearch on teams thatcared for adultclient

groups.Recordswhere thisinformation wasambiguouswere

retained.Studies of pre-qualification interprofessionaleducation

were excluded.A total of 762 records remained (Figure 1).

Originalresearch studiesfrom the firststage search were

retrieved,along with any relevant reviews.Reference lists of the

latter were screened and potentially relevanttitles followed up.

Further, snowball sampling was undertaken throughout the rev

whereby thereferencelist of every articleread in full was

screened for further relevant articles.

Two of the authors began reading the collected articles in ful

Detailed inclusion criteria were notapplied,butarticles had to

Table I.First stage search strategy: free text terms and operators.

theor* OR feature* OR trait* OR characteristic* OR attribute*

AND

interprofessional OR multiprofessional OR interdisciplinary OR multi-

disciplinary OR transdisciplinary OR multi agency OR collaborat*

OR integrate*

AND

teamwork* OR team work* OR team-work*

AND

health*

502 G. Hewitt et al. J Interprof Care,2014; 28(6): 501–506

report empirical studies from the health literature that addressed

interprofessionalteamwork and wererelevantto one of the

provisional mechanisms or suggested a new mechanism. Bespoke

data extraction forms were designed to summarise articles and

record CMO configurationsidentified in thestudy findings.

Forms were also completed for excluded articles, with the reason

for exclusion recorded.Mostoften this was because the article

was not relevant,i.e. did not addressany mechanisms;other

reasons included lack of useful detail about mechanisms, unclear

methods and not reporting original research.

Early on, nine articles were read and discussed by the authors

to check consistency of data extraction. Discussion of all articles

read up to thatpointraised three more potentialmechanisms

(Table II) and these were defined and incorporated into the data

extraction form (Appendix).

As reading and data extraction progressed it became clear that

following the realistsynthesis method exactly as described by

Pawson etal. (2004)was too ambitiouswith the resources

available as numerous CMO configurations were being identified.

Instead,main findingspertainingto each mechanism were

summarised.Informationon contextsand on outcomesfor

patients,teams,staff and organisations was noted,but individual

CMO configurations (as in Box 1) were not recorded. A narrative

approach to synthesising the findings on mechanisms,contexts

and outcomes could then be adopted.The data extraction form

was amended accordingly.

After reviewing 232 articles,of which 109 were included

(Figure 1),evidence foreach mechanism wassynthesised by

drawing togetherthe information on contexts,mechanisms and

outcomes from the data extraction forms. The aim was to test a

develop the provisional definitions of the mechanisms (Table II)

Synthesis of the evidence started atthis pointratherthan after

reviewing all 762 records because the realist synthesis method

an iterative and cyclicalprocess,where reading,searching and

synthesis occur together and inform each other.

For each mechanism, relevant sections of articles were re-re

and similarities and differences in their findings sought in order

build a comprehensive description of the mechanism,its role in

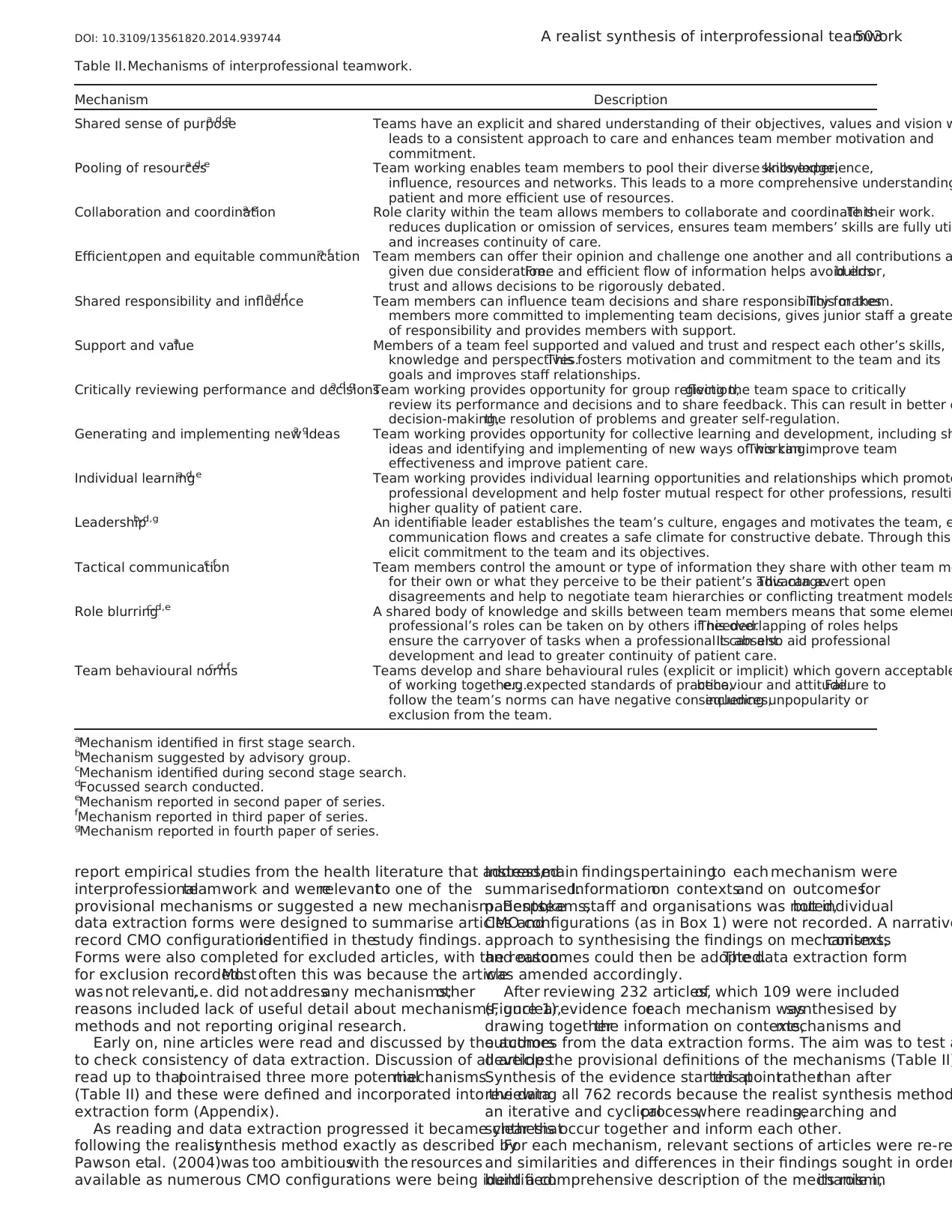

Table II.Mechanisms of interprofessional teamwork.

Mechanism Description

Shared sense of purposea,d,g Teams have an explicit and shared understanding of their objectives, values and vision w

leads to a consistent approach to care and enhances team member motivation and

commitment.

Pooling of resourcesa,d,e Team working enables team members to pool their diverse knowledge,skills,experience,

influence, resources and networks. This leads to a more comprehensive understanding

patient and more efficient use of resources.

Collaboration and coordinationa,e Role clarity within the team allows members to collaborate and coordinate their work.This

reduces duplication or omission of services, ensures team members’ skills are fully uti

and increases continuity of care.

Efficient,open and equitable communicationa,f Team members can offer their opinion and challenge one another and all contributions a

given due consideration.Free and efficient flow of information helps avoid error,builds

trust and allows decisions to be rigorously debated.

Shared responsibility and influencea,d,f Team members can influence team decisions and share responsibility for them.This makes

members more committed to implementing team decisions, gives junior staff a greate

of responsibility and provides members with support.

Support and valuea Members of a team feel supported and valued and trust and respect each other’s skills,

knowledge and perspectives.This fosters motivation and commitment to the team and its

goals and improves staff relationships.

Critically reviewing performance and decisionsa,d,g Team working provides opportunity for group reflection,giving the team space to critically

review its performance and decisions and to share feedback. This can result in better q

decision-making,the resolution of problems and greater self-regulation.

Generating and implementing new ideasa,g Team working provides opportunity for collective learning and development, including sh

ideas and identifying and implementing of new ways of working.This can improve team

effectiveness and improve patient care.

Individual learninga,d,e Team working provides individual learning opportunities and relationships which promote

professional development and help foster mutual respect for other professions, resulti

higher quality of patient care.

Leadershipb,d,g An identifiable leader establishes the team’s culture, engages and motivates the team, e

communication flows and creates a safe climate for constructive debate. Through this

elicit commitment to the team and its objectives.

Tactical communicationc,f Team members control the amount or type of information they share with other team me

for their own or what they perceive to be their patient’s advantage.This can avert open

disagreements and help to negotiate team hierarchies or conflicting treatment models

Role blurringc,d,e A shared body of knowledge and skills between team members means that some elemen

professional’s roles can be taken on by others if needed.This overlapping of roles helps

ensure the carryover of tasks when a professional is absent.It can also aid professional

development and lead to greater continuity of patient care.

Team behavioural normsc,d,f Teams develop and share behavioural rules (explicit or implicit) which govern acceptable

of working together,e.g.expected standards of practice,behaviour and attitude.Failure to

follow the team’s norms can have negative consequences,including unpopularity or

exclusion from the team.

aMechanism identified in first stage search.

bMechanism suggested by advisory group.

cMechanism identified during second stage search.

dFocussed search conducted.

eMechanism reported in second paper of series.

fMechanism reported in third paper of series.

gMechanism reported in fourth paper of series.

DOI: 10.3109/13561820.2014.939744 A realist synthesis of interprofessional teamwork503

interprofessionalteamwork and wererelevantto one of the

provisional mechanisms or suggested a new mechanism. Bespoke

data extraction forms were designed to summarise articles and

record CMO configurationsidentified in thestudy findings.

Forms were also completed for excluded articles, with the reason

for exclusion recorded.Mostoften this was because the article

was not relevant,i.e. did not addressany mechanisms;other

reasons included lack of useful detail about mechanisms, unclear

methods and not reporting original research.

Early on, nine articles were read and discussed by the authors

to check consistency of data extraction. Discussion of all articles

read up to thatpointraised three more potentialmechanisms

(Table II) and these were defined and incorporated into the data

extraction form (Appendix).

As reading and data extraction progressed it became clear that

following the realistsynthesis method exactly as described by

Pawson etal. (2004)was too ambitiouswith the resources

available as numerous CMO configurations were being identified.

Instead,main findingspertainingto each mechanism were

summarised.Informationon contextsand on outcomesfor

patients,teams,staff and organisations was noted,but individual

CMO configurations (as in Box 1) were not recorded. A narrative

approach to synthesising the findings on mechanisms,contexts

and outcomes could then be adopted.The data extraction form

was amended accordingly.

After reviewing 232 articles,of which 109 were included

(Figure 1),evidence foreach mechanism wassynthesised by

drawing togetherthe information on contexts,mechanisms and

outcomes from the data extraction forms. The aim was to test a

develop the provisional definitions of the mechanisms (Table II)

Synthesis of the evidence started atthis pointratherthan after

reviewing all 762 records because the realist synthesis method

an iterative and cyclicalprocess,where reading,searching and

synthesis occur together and inform each other.

For each mechanism, relevant sections of articles were re-re

and similarities and differences in their findings sought in order

build a comprehensive description of the mechanism,its role in

Table II.Mechanisms of interprofessional teamwork.

Mechanism Description

Shared sense of purposea,d,g Teams have an explicit and shared understanding of their objectives, values and vision w

leads to a consistent approach to care and enhances team member motivation and

commitment.

Pooling of resourcesa,d,e Team working enables team members to pool their diverse knowledge,skills,experience,

influence, resources and networks. This leads to a more comprehensive understanding

patient and more efficient use of resources.

Collaboration and coordinationa,e Role clarity within the team allows members to collaborate and coordinate their work.This

reduces duplication or omission of services, ensures team members’ skills are fully uti

and increases continuity of care.

Efficient,open and equitable communicationa,f Team members can offer their opinion and challenge one another and all contributions a

given due consideration.Free and efficient flow of information helps avoid error,builds

trust and allows decisions to be rigorously debated.

Shared responsibility and influencea,d,f Team members can influence team decisions and share responsibility for them.This makes

members more committed to implementing team decisions, gives junior staff a greate

of responsibility and provides members with support.

Support and valuea Members of a team feel supported and valued and trust and respect each other’s skills,

knowledge and perspectives.This fosters motivation and commitment to the team and its

goals and improves staff relationships.

Critically reviewing performance and decisionsa,d,g Team working provides opportunity for group reflection,giving the team space to critically

review its performance and decisions and to share feedback. This can result in better q

decision-making,the resolution of problems and greater self-regulation.

Generating and implementing new ideasa,g Team working provides opportunity for collective learning and development, including sh

ideas and identifying and implementing of new ways of working.This can improve team

effectiveness and improve patient care.

Individual learninga,d,e Team working provides individual learning opportunities and relationships which promote

professional development and help foster mutual respect for other professions, resulti

higher quality of patient care.

Leadershipb,d,g An identifiable leader establishes the team’s culture, engages and motivates the team, e

communication flows and creates a safe climate for constructive debate. Through this

elicit commitment to the team and its objectives.

Tactical communicationc,f Team members control the amount or type of information they share with other team me

for their own or what they perceive to be their patient’s advantage.This can avert open

disagreements and help to negotiate team hierarchies or conflicting treatment models

Role blurringc,d,e A shared body of knowledge and skills between team members means that some elemen

professional’s roles can be taken on by others if needed.This overlapping of roles helps

ensure the carryover of tasks when a professional is absent.It can also aid professional

development and lead to greater continuity of patient care.

Team behavioural normsc,d,f Teams develop and share behavioural rules (explicit or implicit) which govern acceptable

of working together,e.g.expected standards of practice,behaviour and attitude.Failure to

follow the team’s norms can have negative consequences,including unpopularity or

exclusion from the team.

aMechanism identified in first stage search.

bMechanism suggested by advisory group.

cMechanism identified during second stage search.

dFocussed search conducted.

eMechanism reported in second paper of series.

fMechanism reported in third paper of series.

gMechanism reported in fourth paper of series.

DOI: 10.3109/13561820.2014.939744 A realist synthesis of interprofessional teamwork503

interprofessionalteamwork and the contextsthattriggered or

inhibited it. Data extraction forms contained a section for notes on

each study’s methodologicalquality and the robustness ofthe

conclusions drawn.This information was drawn on during the

synthesis,not to includeor excludestudies,but to inform

decisions regarding the strength of the contribution the evidence

from that article should make to the synthesis.

Furtherfocussed searches were undertaken formechanisms

with weak evidence or only a small number of articles (Table II).

Appropriate key words were identified and used to search the

remaining records from the second stage search,the Journalof

Interprofessional Care, MEDLINE and CINAHL. Relevant papers

identified were then fed into the synthesis of the mechanism.

Realist synthesis draws on the qualitative research principle of

saturation, meaning that searching ceases when no new evidence

for a mechanism is emerging.However,the review was halted

following the focussed searches for pragmatic reasons,despite a

large number of articles from the second stage search remaining

unread.Whilstsome evidence may therefore have been missed,

sufficienthad been reviewed to begin to explore and testthe

mechanisms identified.

Findings

Support and value mechanism

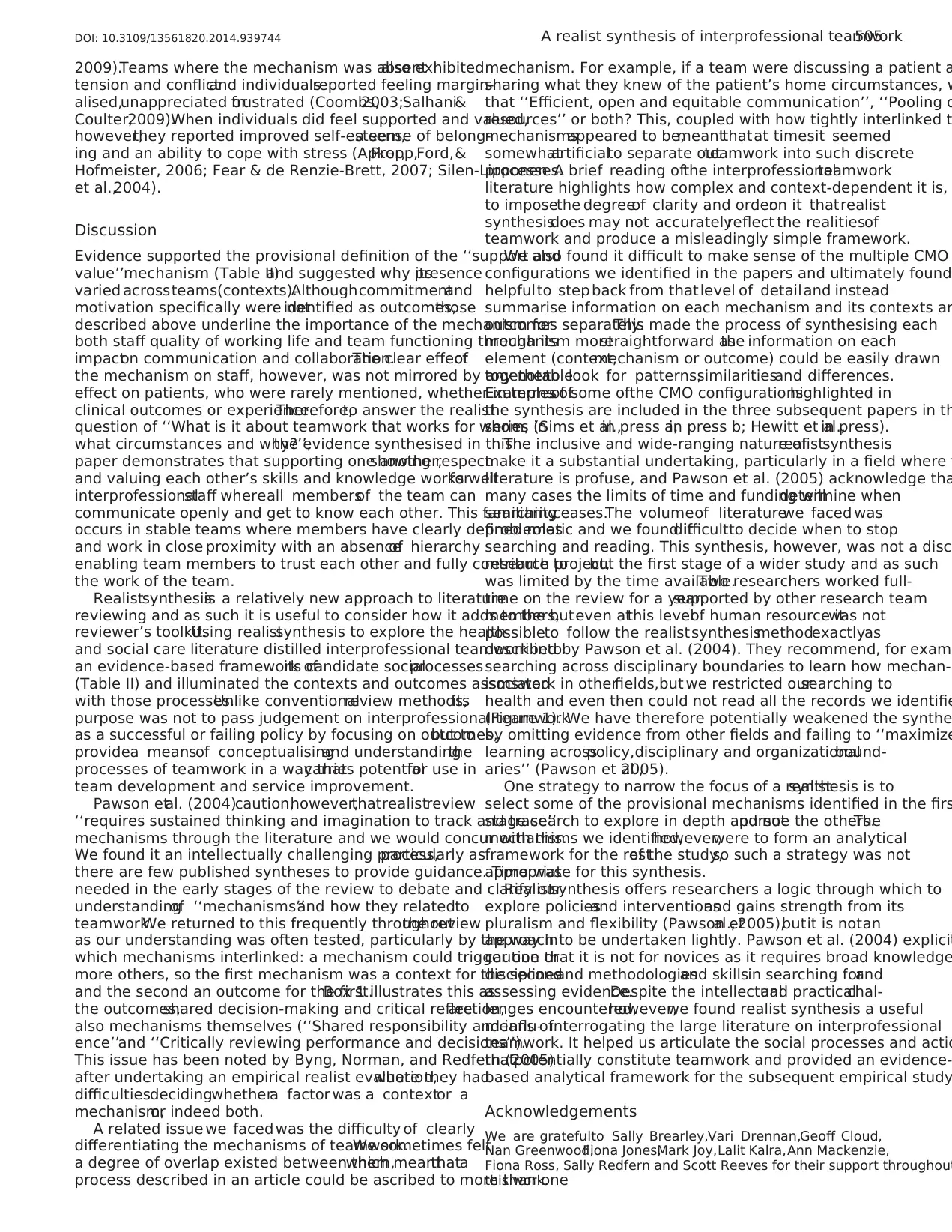

This section reports the evidence pertaining to the ‘‘Support and

value’’ mechanism within therealistframework ofcontext,

mechanism and outcome. Evidence for the other twelve mechan-

isms are reported in later papers in the series (Hewitt et al., in press;

Sims etal., in press a,in press b).Sixty-one articles reporting

59 studieswere included in the synthesisof this mechanism

(Harris et al., 2013). Most used qualitative research methods and

approximately halfwere conducted in the UK.Studieswere

undertaken in a variety of inpatient and community settings and

with many typesof interprofessionalteam,strengthening the

relevance of the findings across health.Box 1 illustrates a CMO

configuration of the ‘‘support and value’’ mechanism.

The provisional definition of ‘‘supportand value’’ (Table II)

posited that individuals respond to team membership by suppo

one another and showing respect to and valuing each other’s s

and knowledge. Evidence to support this was found, but there w

also reports of teams where the mechanism was clearly absent

most common manifestation of the mechanism was where all t

members’ contributions were seen as important and valued eq

This meant that everyone was trusted, their knowledge and ski

were recognised,interestwas shown in everyone’s opinions and

members encouraged one anotherto participate (Craigie Jr&

Hobbs, 2004; Pethybridge, 2004; Shaw, Walker, & Hogue, 2008

Socialbonds were evidentin some teams where members were

friends as well as colleagues and interactions included humour

chat(Kvarnstrom & Cedersund,2006;Reeves & Lewin,2004).

Othermanifestationsincluded praise between team members,

backing one anotherup and sharing emotionswhen stressed

(Apker, Propp, & Ford, 2005; Wilson, McCormack, & Ives, 2005;

Wittenberg-Lyles & Parker-Oliver, 2007).

When the mechanism was absent, individuals reported feelin

their contributions were not valued and a lack of trust, obstruct

behaviour and bullying were evident(Lingard,Espin,Evans,&

Hawryluck,2004;Rice Simpson,James,& Knox, 2006;Silen-

Lipponen,Tossavainen,Turunen,Smith,& Burdett,2004).

A number of contexts suggested why ‘‘support and value’’ w

present in some teams but absent in others.Another mechanism,

‘‘Efficient,open and equitablecommunication’’was tightly

linked to ‘‘Supportand value’’,being both a contextand an

outcome of it. As a context, open communication meant all tea

members could contribute and get to know one another,helping

build cohesive teams and respect across professions (Craigie Jr

Hobbs,2004;Fear & de Renzie-Brett,2007).Trustand respect

were also enhanced by familiarity and thiscontextwas most

prominentin teamswith long-standingmembersor where

membersworked in close proximity (Reeves& Lewin, 2004;

Rice Simpson et al., 2006). Role clarity and ambiguity were also

importantcontexts,whereby the former promoted and the latter

underminedtrust within teams(Atwal, 2002; Gantert&

McWilliam,2004).Professionalhierarchy wasalso influential

as individuals in ‘‘lower status’’ roles sometimes felt less truste

and valued, whilst others did not necessarily believe that equal

between the professions existed (Coombs & Ersser, 2004; Morr

Payne,& Lambert,2007; Sargeant,Loney,& Murphy,2008).

The ‘‘Efficient, open and equitable communication’’ mechan-

ism was an outcome for ‘‘Support and value’’ as well as a conte

When elementsof ‘‘Supportand value’’were present,team

communication improved and when absent,communication was

inhibited as individuals feltunable orunwilling to voice their

opinionsor challengeothers(Field & West, 1995;Piquette,

Reeves, & Leblanc, 2009). ‘‘Support and value’’ impacted on th

‘‘Collaboration and coordination’’ mechanism too,as supportive

teamsshowed improved collaboration and unsupportive teams

collaborated less well(Lingard etal., 2004;Salhani& Coulter,

Records screened for

original research and

interprofessional education

232 papers read

87 records identified

from reviews and

snowball sampling

109 included

123 excluded

3 new mechanisms identified;

evidence for mechanisms

synthesised

Focused searches; 19 additional

papers included

35 records

retrieved from first

stage search

1103 excluded

762 records remaining;

110 papers read in full

1865 records

identified

Figure 1.Flow chart of second stage search.

Box 1. CMO configuration of ‘‘Support and value’’ mechanism.

A study of cooperation and autonomy in two Dutch hospital teams

(geriatrics and oncology) found that over the period of their existence

(three years) trust had grown, so members knew each other better a

trusted one another much more than they had in the teams’ early da

Consequently, initial reluctance to involve other members in decision

making had largely disappeared and the teams openly reflected on

individuals’ decisions during patient discussions,where voicing

criticisms of other members had become much more acceptable

(Molleman,Broekhuis,Stoffels,& Jaspers,2008).

Long tenure of team (C) ! Trust between team members (M) ! Shared

decision-making and critical reflection (O)

504 G. Hewitt et al. J Interprof Care,2014; 28(6): 501–506

inhibited it. Data extraction forms contained a section for notes on

each study’s methodologicalquality and the robustness ofthe

conclusions drawn.This information was drawn on during the

synthesis,not to includeor excludestudies,but to inform

decisions regarding the strength of the contribution the evidence

from that article should make to the synthesis.

Furtherfocussed searches were undertaken formechanisms

with weak evidence or only a small number of articles (Table II).

Appropriate key words were identified and used to search the

remaining records from the second stage search,the Journalof

Interprofessional Care, MEDLINE and CINAHL. Relevant papers

identified were then fed into the synthesis of the mechanism.

Realist synthesis draws on the qualitative research principle of

saturation, meaning that searching ceases when no new evidence

for a mechanism is emerging.However,the review was halted

following the focussed searches for pragmatic reasons,despite a

large number of articles from the second stage search remaining

unread.Whilstsome evidence may therefore have been missed,

sufficienthad been reviewed to begin to explore and testthe

mechanisms identified.

Findings

Support and value mechanism

This section reports the evidence pertaining to the ‘‘Support and

value’’ mechanism within therealistframework ofcontext,

mechanism and outcome. Evidence for the other twelve mechan-

isms are reported in later papers in the series (Hewitt et al., in press;

Sims etal., in press a,in press b).Sixty-one articles reporting

59 studieswere included in the synthesisof this mechanism

(Harris et al., 2013). Most used qualitative research methods and

approximately halfwere conducted in the UK.Studieswere

undertaken in a variety of inpatient and community settings and

with many typesof interprofessionalteam,strengthening the

relevance of the findings across health.Box 1 illustrates a CMO

configuration of the ‘‘support and value’’ mechanism.

The provisional definition of ‘‘supportand value’’ (Table II)

posited that individuals respond to team membership by suppo

one another and showing respect to and valuing each other’s s

and knowledge. Evidence to support this was found, but there w

also reports of teams where the mechanism was clearly absent

most common manifestation of the mechanism was where all t

members’ contributions were seen as important and valued eq

This meant that everyone was trusted, their knowledge and ski

were recognised,interestwas shown in everyone’s opinions and

members encouraged one anotherto participate (Craigie Jr&

Hobbs, 2004; Pethybridge, 2004; Shaw, Walker, & Hogue, 2008

Socialbonds were evidentin some teams where members were

friends as well as colleagues and interactions included humour

chat(Kvarnstrom & Cedersund,2006;Reeves & Lewin,2004).

Othermanifestationsincluded praise between team members,

backing one anotherup and sharing emotionswhen stressed

(Apker, Propp, & Ford, 2005; Wilson, McCormack, & Ives, 2005;

Wittenberg-Lyles & Parker-Oliver, 2007).

When the mechanism was absent, individuals reported feelin

their contributions were not valued and a lack of trust, obstruct

behaviour and bullying were evident(Lingard,Espin,Evans,&

Hawryluck,2004;Rice Simpson,James,& Knox, 2006;Silen-

Lipponen,Tossavainen,Turunen,Smith,& Burdett,2004).

A number of contexts suggested why ‘‘support and value’’ w

present in some teams but absent in others.Another mechanism,

‘‘Efficient,open and equitablecommunication’’was tightly

linked to ‘‘Supportand value’’,being both a contextand an

outcome of it. As a context, open communication meant all tea

members could contribute and get to know one another,helping

build cohesive teams and respect across professions (Craigie Jr

Hobbs,2004;Fear & de Renzie-Brett,2007).Trustand respect

were also enhanced by familiarity and thiscontextwas most

prominentin teamswith long-standingmembersor where

membersworked in close proximity (Reeves& Lewin, 2004;

Rice Simpson et al., 2006). Role clarity and ambiguity were also

importantcontexts,whereby the former promoted and the latter

underminedtrust within teams(Atwal, 2002; Gantert&

McWilliam,2004).Professionalhierarchy wasalso influential

as individuals in ‘‘lower status’’ roles sometimes felt less truste

and valued, whilst others did not necessarily believe that equal

between the professions existed (Coombs & Ersser, 2004; Morr

Payne,& Lambert,2007; Sargeant,Loney,& Murphy,2008).

The ‘‘Efficient, open and equitable communication’’ mechan-

ism was an outcome for ‘‘Support and value’’ as well as a conte

When elementsof ‘‘Supportand value’’were present,team

communication improved and when absent,communication was

inhibited as individuals feltunable orunwilling to voice their

opinionsor challengeothers(Field & West, 1995;Piquette,

Reeves, & Leblanc, 2009). ‘‘Support and value’’ impacted on th

‘‘Collaboration and coordination’’ mechanism too,as supportive

teamsshowed improved collaboration and unsupportive teams

collaborated less well(Lingard etal., 2004;Salhani& Coulter,

Records screened for

original research and

interprofessional education

232 papers read

87 records identified

from reviews and

snowball sampling

109 included

123 excluded

3 new mechanisms identified;

evidence for mechanisms

synthesised

Focused searches; 19 additional

papers included

35 records

retrieved from first

stage search

1103 excluded

762 records remaining;

110 papers read in full

1865 records

identified

Figure 1.Flow chart of second stage search.

Box 1. CMO configuration of ‘‘Support and value’’ mechanism.

A study of cooperation and autonomy in two Dutch hospital teams

(geriatrics and oncology) found that over the period of their existence

(three years) trust had grown, so members knew each other better a

trusted one another much more than they had in the teams’ early da

Consequently, initial reluctance to involve other members in decision

making had largely disappeared and the teams openly reflected on

individuals’ decisions during patient discussions,where voicing

criticisms of other members had become much more acceptable

(Molleman,Broekhuis,Stoffels,& Jaspers,2008).

Long tenure of team (C) ! Trust between team members (M) ! Shared

decision-making and critical reflection (O)

504 G. Hewitt et al. J Interprof Care,2014; 28(6): 501–506

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

2009).Teams where the mechanism was absentalso exhibited

tension and conflictand individualsreported feeling margin-

alised,unappreciated orfrustrated (Coombs,2003;Salhani&

Coulter,2009).When individuals did feel supported and valued,

however,they reported improved self-esteem,a sense of belong-

ing and an ability to cope with stress (Apker,Propp,Ford,&

Hofmeister, 2006; Fear & de Renzie-Brett, 2007; Silen-Lipponen

et al.,2004).

Discussion

Evidence supported the provisional definition of the ‘‘support and

value’’mechanism (Table II)and suggested why itspresence

varied acrossteams(contexts).Althoughcommitmentand

motivation specifically were notidentified as outcomes,those

described above underline the importance of the mechanism for

both staff quality of working life and team functioning through its

impacton communication and collaboration.The clear effectof

the mechanism on staff, however, was not mirrored by any notable

effect on patients, who were rarely mentioned, whether in terms of

clinical outcomes or experience.Therefore,to answer the realist

question of ‘‘What is it about teamwork that works for whom, in

what circumstances and why?’’,the evidence synthesised in this

paper demonstrates that supporting one another,showing respect

and valuing each other’s skills and knowledge works wellfor

interprofessionalstaff whereall membersof the team can

communicate openly and get to know each other. This familiarity

occurs in stable teams where members have clearly defined roles

and work in close proximity with an absenceof hierarchy

enabling team members to trust each other and fully contribute to

the work of the team.

Realistsynthesisis a relatively new approach to literature

reviewing and as such it is useful to consider how it adds to the

reviewer’s toolkit.Using realistsynthesis to explore the health

and social care literature distilled interprofessional teamwork into

an evidence-based framework ofits candidate socialprocesses

(Table II) and illuminated the contexts and outcomes associated

with those processes.Unlike conventionalreview methods,its

purpose was not to pass judgement on interprofessional teamwork

as a successful or failing policy by focusing on outcomes,but to

providea meansof conceptualisingand understandingthe

processes of teamwork in a way thatcarries potentialfor use in

team development and service improvement.

Pawson etal. (2004)caution,however,thatrealistreview

‘‘requires sustained thinking and imagination to track and trace’’

mechanisms through the literature and we would concur with this.

We found it an intellectually challenging process,particularly as

there are few published syntheses to provide guidance. Time was

needed in the early stages of the review to debate and clarify our

understandingof ‘‘mechanisms’’and how they relatedto

teamwork.We returned to this frequently throughoutthe review

as our understanding was often tested, particularly by the way in

which mechanisms interlinked: a mechanism could trigger one or

more others, so the first mechanism was a context for the second

and the second an outcome for the first.Box 1 illustrates this as

the outcomes,shared decision-making and critical reflection,are

also mechanisms themselves (‘‘Shared responsibility and influ-

ence’’and ‘‘Critically reviewing performance and decisions’’).

This issue has been noted by Byng, Norman, and Redfern (2005)

after undertaking an empirical realist evaluation,where they had

difficultiesdecidingwhethera factor was a contextor a

mechanism,or indeed both.

A related issue we faced was the difficulty of clearly

differentiating the mechanisms of teamwork.We sometimes felt

a degree of overlap existed between them,which meantthata

process described in an article could be ascribed to more than one

mechanism. For example, if a team were discussing a patient a

sharing what they knew of the patient’s home circumstances, w

that ‘‘Efficient, open and equitable communication’’, ‘‘Pooling o

resources’’ or both? This, coupled with how tightly interlinked t

mechanismsappeared to be,meantthatat timesit seemed

somewhatartificialto separate outteamwork into such discrete

processes.A brief reading ofthe interprofessionalteamwork

literature highlights how complex and context-dependent it is,

to imposethe degreeof clarity and orderon it thatrealist

synthesisdoes may not accuratelyreflect the realitiesof

teamwork and produce a misleadingly simple framework.

We also found it difficult to make sense of the multiple CMO

configurations we identified in the papers and ultimately found

helpfulto step back from thatlevel of detailand instead

summarise information on each mechanism and its contexts an

outcomes separately.This made the process of synthesising each

mechanism morestraightforward asthe information on each

element (context,mechanism or outcome) could be easily drawn

togetherto look for patterns,similaritiesand differences.

Examplesof some ofthe CMO configurationshighlighted in

the synthesis are included in the three subsequent papers in th

series (Sims et al.,in press a,in press b; Hewitt et al.,in press).

The inclusive and wide-ranging nature ofrealistsynthesis

make it a substantial undertaking, particularly in a field where t

literature is profuse, and Pawson et al. (2005) acknowledge tha

many cases the limits of time and funding willdetermine when

searchingceases.The volumeof literaturewe faced was

problematic and we found itdifficultto decide when to stop

searching and reading. This synthesis, however, was not a disc

research project,but the first stage of a wider study and as such

was limited by the time available.Two researchers worked full-

time on the review for a year,supported by other research team

members,buteven atthis levelof human resource itwas not

possibleto follow the realistsynthesismethodexactlyas

described by Pawson et al. (2004). They recommend, for exam

searching across disciplinary boundaries to learn how mechan-

ismswork in otherfields,but we restricted oursearching to

health and even then could not read all the records we identifie

(Figure 1). We have therefore potentially weakened the synthe

by omitting evidence from other fields and failing to ‘‘maximize

learning acrosspolicy,disciplinary and organizationalbound-

aries’’ (Pawson et al.,2005).

One strategy to narrow the focus of a realistsynthesis is to

select some of the provisional mechanisms identified in the firs

stage search to explore in depth and notpursue the others.The

mechanisms we identified,however,were to form an analytical

framework for the restof the study,so such a strategy was not

appropriate for this synthesis.

Realistsynthesis offers researchers a logic through which to

explore policiesand interventionsand gains strength from its

pluralism and flexibility (Pawson etal., 2005),butit is notan

approach to be undertaken lightly. Pawson et al. (2004) explicit

caution that it is not for novices as it requires broad knowledge

disciplinesand methodologiesand skillsin searching forand

assessing evidence.Despite the intellectualand practicalchal-

lenges encountered,however,we found realist synthesis a useful

means ofinterrogating the large literature on interprofessional

teamwork. It helped us articulate the social processes and actio

thatpotentially constitute teamwork and provided an evidence-

based analytical framework for the subsequent empirical study

Acknowledgements

We are gratefulto Sally Brearley,Vari Drennan,Geoff Cloud,

Nan Greenwood,Fiona Jones,Mark Joy,Lalit Kalra,Ann Mackenzie,

Fiona Ross, Sally Redfern and Scott Reeves for their support throughout

this work.

DOI: 10.3109/13561820.2014.939744 A realist synthesis of interprofessional teamwork505

tension and conflictand individualsreported feeling margin-

alised,unappreciated orfrustrated (Coombs,2003;Salhani&

Coulter,2009).When individuals did feel supported and valued,

however,they reported improved self-esteem,a sense of belong-

ing and an ability to cope with stress (Apker,Propp,Ford,&

Hofmeister, 2006; Fear & de Renzie-Brett, 2007; Silen-Lipponen

et al.,2004).

Discussion

Evidence supported the provisional definition of the ‘‘support and

value’’mechanism (Table II)and suggested why itspresence

varied acrossteams(contexts).Althoughcommitmentand

motivation specifically were notidentified as outcomes,those

described above underline the importance of the mechanism for

both staff quality of working life and team functioning through its

impacton communication and collaboration.The clear effectof

the mechanism on staff, however, was not mirrored by any notable

effect on patients, who were rarely mentioned, whether in terms of

clinical outcomes or experience.Therefore,to answer the realist

question of ‘‘What is it about teamwork that works for whom, in

what circumstances and why?’’,the evidence synthesised in this

paper demonstrates that supporting one another,showing respect

and valuing each other’s skills and knowledge works wellfor

interprofessionalstaff whereall membersof the team can

communicate openly and get to know each other. This familiarity

occurs in stable teams where members have clearly defined roles

and work in close proximity with an absenceof hierarchy

enabling team members to trust each other and fully contribute to

the work of the team.

Realistsynthesisis a relatively new approach to literature

reviewing and as such it is useful to consider how it adds to the

reviewer’s toolkit.Using realistsynthesis to explore the health

and social care literature distilled interprofessional teamwork into

an evidence-based framework ofits candidate socialprocesses

(Table II) and illuminated the contexts and outcomes associated

with those processes.Unlike conventionalreview methods,its

purpose was not to pass judgement on interprofessional teamwork

as a successful or failing policy by focusing on outcomes,but to

providea meansof conceptualisingand understandingthe

processes of teamwork in a way thatcarries potentialfor use in

team development and service improvement.

Pawson etal. (2004)caution,however,thatrealistreview

‘‘requires sustained thinking and imagination to track and trace’’

mechanisms through the literature and we would concur with this.

We found it an intellectually challenging process,particularly as

there are few published syntheses to provide guidance. Time was

needed in the early stages of the review to debate and clarify our

understandingof ‘‘mechanisms’’and how they relatedto

teamwork.We returned to this frequently throughoutthe review

as our understanding was often tested, particularly by the way in

which mechanisms interlinked: a mechanism could trigger one or

more others, so the first mechanism was a context for the second

and the second an outcome for the first.Box 1 illustrates this as

the outcomes,shared decision-making and critical reflection,are

also mechanisms themselves (‘‘Shared responsibility and influ-

ence’’and ‘‘Critically reviewing performance and decisions’’).

This issue has been noted by Byng, Norman, and Redfern (2005)

after undertaking an empirical realist evaluation,where they had

difficultiesdecidingwhethera factor was a contextor a

mechanism,or indeed both.

A related issue we faced was the difficulty of clearly

differentiating the mechanisms of teamwork.We sometimes felt

a degree of overlap existed between them,which meantthata

process described in an article could be ascribed to more than one

mechanism. For example, if a team were discussing a patient a

sharing what they knew of the patient’s home circumstances, w

that ‘‘Efficient, open and equitable communication’’, ‘‘Pooling o

resources’’ or both? This, coupled with how tightly interlinked t

mechanismsappeared to be,meantthatat timesit seemed

somewhatartificialto separate outteamwork into such discrete

processes.A brief reading ofthe interprofessionalteamwork

literature highlights how complex and context-dependent it is,

to imposethe degreeof clarity and orderon it thatrealist

synthesisdoes may not accuratelyreflect the realitiesof

teamwork and produce a misleadingly simple framework.

We also found it difficult to make sense of the multiple CMO

configurations we identified in the papers and ultimately found

helpfulto step back from thatlevel of detailand instead

summarise information on each mechanism and its contexts an

outcomes separately.This made the process of synthesising each

mechanism morestraightforward asthe information on each

element (context,mechanism or outcome) could be easily drawn

togetherto look for patterns,similaritiesand differences.

Examplesof some ofthe CMO configurationshighlighted in

the synthesis are included in the three subsequent papers in th

series (Sims et al.,in press a,in press b; Hewitt et al.,in press).

The inclusive and wide-ranging nature ofrealistsynthesis

make it a substantial undertaking, particularly in a field where t

literature is profuse, and Pawson et al. (2005) acknowledge tha

many cases the limits of time and funding willdetermine when

searchingceases.The volumeof literaturewe faced was

problematic and we found itdifficultto decide when to stop

searching and reading. This synthesis, however, was not a disc

research project,but the first stage of a wider study and as such

was limited by the time available.Two researchers worked full-

time on the review for a year,supported by other research team

members,buteven atthis levelof human resource itwas not

possibleto follow the realistsynthesismethodexactlyas

described by Pawson et al. (2004). They recommend, for exam

searching across disciplinary boundaries to learn how mechan-

ismswork in otherfields,but we restricted oursearching to

health and even then could not read all the records we identifie

(Figure 1). We have therefore potentially weakened the synthe

by omitting evidence from other fields and failing to ‘‘maximize

learning acrosspolicy,disciplinary and organizationalbound-

aries’’ (Pawson et al.,2005).

One strategy to narrow the focus of a realistsynthesis is to

select some of the provisional mechanisms identified in the firs

stage search to explore in depth and notpursue the others.The

mechanisms we identified,however,were to form an analytical

framework for the restof the study,so such a strategy was not

appropriate for this synthesis.

Realistsynthesis offers researchers a logic through which to

explore policiesand interventionsand gains strength from its

pluralism and flexibility (Pawson etal., 2005),butit is notan

approach to be undertaken lightly. Pawson et al. (2004) explicit

caution that it is not for novices as it requires broad knowledge

disciplinesand methodologiesand skillsin searching forand

assessing evidence.Despite the intellectualand practicalchal-

lenges encountered,however,we found realist synthesis a useful

means ofinterrogating the large literature on interprofessional

teamwork. It helped us articulate the social processes and actio

thatpotentially constitute teamwork and provided an evidence-

based analytical framework for the subsequent empirical study

Acknowledgements

We are gratefulto Sally Brearley,Vari Drennan,Geoff Cloud,

Nan Greenwood,Fiona Jones,Mark Joy,Lalit Kalra,Ann Mackenzie,

Fiona Ross, Sally Redfern and Scott Reeves for their support throughout

this work.

DOI: 10.3109/13561820.2014.939744 A realist synthesis of interprofessional teamwork505

Declaration of interest

This projectwas funded by the NationalInstitute for Health Research

(NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR)programme

(project number 08/1819/219). The views and opinions expressed therein

are those ofthe authorsand do notnecessarily reflectthose ofthe

HS&DR programme,NIHR, NHS or the Departmentof Health.The

authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors are responsible for the

writing and content of this paper.

References

Apker,J., Propp,K.M., & Ford, W.S.Z.(2005).Negotiating status and

identity tensions in healthcare team interactions:An exploration of

nurse role dialectics. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 33,

93–115.

Apker, J., Propp, K.M., Ford, W.S.Z., & Hofmeister,N. (2006).

Collaboration,credibility,compassion,and coordination: Professional

nursecommunication skillsets in health careteam interactions.

Journal of Professional Nursing,22,180–189.

Atwal, A. (2002). A world apart: How occupational therapists, nurses and

care managers perceive each otherin acute health care.The British

Journal of Occupational Therapy,65,446–452.

Byng, R., Norman, I., & Redfern, S. (2005). Using realistic evaluation to

evaluate a practice-level intervention to improve primary healthcare for

patients with long-term mental illness.Evaluation, 11,69–94.

Coombs, M. (2003). Power and conflict in intensive care clinical decision

making.Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 19,125–135.

Coombs,M., & Ersser, S.J. (2004).Medicalhegemony in decision-

making – A barrierto interdisciplinary working in intensive care?

Journal of Advanced Nursing,46,245–252.

Craigie Jr F.C., & Hobbs, R.F. (2004).Exploring the organizational

cultureof exemplarycommunityhealthcenterpractices.Family

Medicine,36,733–738.

Fear,T., & de Renzie-Brett,H. (2007).Developing interprofessional

working in primary care.Practice Developmentin Health Care,6,

107–118.

Field, R., & West, M. (1995).Teamwork in primary health care.2.

Perspectivesfrom practices.Journal of InterprofessionalCare, 9,

123–30.

Gantert,T.W., & McWilliam, C.L. (2004).Interdisciplinaryteam

processeswithin an in-homeservicedelivery organization.Home

Health Care Services Quarterly,23,1–17.

Hammick,M., Freeth,D., Koppel,I., Reeves,S., & Barr,H. (2007).A

best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME

guide no.9. Medical Teacher,29,735–751.

Harris, R., Sims, S., Hewitt, G., Joy, M., Brearley, S., Cloud, G., Drennan,

V., et al. (2013).Interprofessionalteamworkacrossstrokecare

pathways: Outcomes and patientand carer experience.Final report,

NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme.

Hewitt, G., Sims, S., & Harris, R. (in press). Evidence of communication,

influence and behavioural norms in interprofessional teams: A realist

synthesis.Journal of Interprofessional Care.

Kvarnstrom,S., & Cedersund,E. (2006).Discursive patterns in multi-

professionalhealthcareteams.Journal of Advanced Nursing,53,

244–253.

Lingard,L., Espin,S., Evans,C., & Hawryluck,L. (2004).The rules of

the game:Interprofessionalcollaboration on the intensive care unit

team.Critical Care,8, R403–R408.

Molleman,E., Broekhuis,M., Stoffels,R., & Jaspers,F. (2008).How

health care complexity leads to cooperation and affects the autonomy

of health care professionals.Health Care Analysis, 16, 329–341.

Morris,R., Payne,O., & Lambert,A. (2007).Patient,carerand staff

experience of a hospital-based stroke service. International Journal for

Quality in Health Care, 19,105–112.

Pawson,R. (2006).Digging for nuggets:How ‘bad’ research can yield

‘good’ evidence. International Journal of Social Research

Methodology,9, 127–142.

Pawson,R., Greenhalgh,T., Harvey,G., & Walshe,K. (2004).Realist

Synthesis:An introduction.ESRC Research MethodsProgramme

Working Paper Series,University of Manchester.

Pawson,R., Greenhalgh,T., Harvey,G., & Walshe,K. (2005).Realist

review – A new method of systematic review designed for complex

policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10,

21–34.

Pawson,R., & Tilley, N. (1997).Realistic evaluation.London:Sage

Publications.

Pethybridge, J. (2004). How team working influences discharge planning

from hospital:A study offour multi-disciplinary teams in an acute

hospital in England.Journal of Interprofessional Care, 18,29–41.

Piquette,D., Reeves,S., & Leblanc, V.R. (2009).Interprofessional

intensive care unit team interactions and medical crises: A qualitative

study.Journal of Interprofessional Care,23,273–285.

Reeves,S., & Lewin, S. (2004).Interprofessionalcollaboration in the

hospital: Strategies and meanings. Journal of Health Services Researc

and Policy,9, 218–225.

Reeves,S., Lewin, S., Espin, S., & Zwarenstein, M. (2010).

Interprofessionalteamwork forhealth and socialcare.Chichester:

Wiley-Blackwell.

Rice Simpson, K., James, D. C., & Knox, G. E. (2006). Nurse-physician

communication during labor and birth: Implications for patient safety.

Journal of Obstetric,Gynecologic,and NeonatalNursing, 35,

547–556.

Salhani,D., & Coulter, I. (2009).The politicsof interprofessional

working and the struggle for professional autonomy in nursing. Social

Science & Medicine,68,1221–1228.

Sargeant, J., Loney, E., & Murphy, G. (2008). Effective interprofessional

teams: ‘‘Contact is not enough’’ to build a team. Journal of Continuing

Education in the Health Professions,28,228–234.

Shaw,L., Walker,R., & Hogue, A. (2008).The art and science of

teamwork: enacting a transdisciplinary approach in work rehabilitatio

Work (Reading,MA), 30,297–306.

Silen-Lipponen, M., Tossavainen, K., Turunen, H., Smith, A., & Burdett,

K. (2004).Teamwork in operating room nursing as experienced by

Finnish,British and American nurses.Diversity in Health & Social

Care, 1,127–137.

Sims, S., Hewitt, G., & Harris, R. (in press a). Evidence of collaboration,

pooling ofresources,learning and role blurring in interprofessional

healthcare teams: A realist synthesis. Journal of Interprofessional Car

Sims, S., Hewitt, G., & Harris, R. (in press b). Evidence of a shared sense

of purpose,criticalreflection,innovation and leadership in inter-

professionalhealthcareteams:A realist synthesis.Journal of

Interprofessional Care.

Wilson,V.J., McCormack,B.G., & Ives, G. (2005).Understanding the

workplace culture ofa specialcare nursery.Journal of Advanced

Nursing,50, 27–38.

Wittenberg-Lyles,E.M., & Parker-Oliver,D. (2007).The powerof

interdisciplinary collaboration in hospice. Progress in Palliative Care,

15,6–12.

Appendix: Data extraction form

Reviewer: EndNote library number:

Reference:

Objective of study:

Description of paper (include location,setting,field of health,partici-

pants,brief methods):

Mechanisms discussed:

Shared sense of purpose Support and value

Pooling of resources Critically reviewing performance

& decisions