REDD+ Finance Policy for Reduction of Emissions and Carbon Sequestration

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/30

|10

|2330

|199

AI Summary

This article discusses REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration. It highlights the strengths and weaknesses of the policy and its implementation in the Brazilian Amazon. The article also discusses the significance of forest protection in confronting climate change.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration1

REDD+ FINANCE POLICY FOR REDUCTION OF EMISSIONS AND CARBON

SEQUESTRATION

Name:

Department:

School:

Date:

REDD+ FINANCE POLICY FOR REDUCTION OF EMISSIONS AND CARBON

SEQUESTRATION

Name:

Department:

School:

Date:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration2

Introduction

Forest and trees store carbon and when they are completely cleared or degraded, the stored

carbon has the prospect to be released back into the stratosphere as carbon dioxide and contribute

to climate variation. Deforestation contributes up to 10% to carbon dioxide emission caused by

human actions, according to a 2013 figure from the intergovernmental panel on climate change

(Hoang et al. 2013). Tropic forest now discharge more carbon than they capture, due to

degradation and deforestation, so that they are no longer a carbon sink, according to a study

released in 2017 using satellite data from 2003 to 2014 (GRICC 2018).

REDD+ finance policy

Experts have acknowledged the significance of shielding the forest in confronting climate

change. In reaction, legislators have established a family of dogma collectively known is

reducing emission from deforestation and degradation (REDD) to offers a monetary incentive to

agribusiness, government, and societies to uphold and probably upsurge, rather than minimise

the forest protection (Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2015). Under REDD+, incentives for forest

protection are provided to nations, individual’s landowners, and communities in exchange for

slowing deforestation, and carrying out routines that aid reforestation, and sustainable forest

management (Bayrak, Tu and Marafa 2014). REDD+ policies function over a range of

mechanism, including those managed by the United Nations (UN-REDD) and the World Bank

(the Forest carbon partnership facility) (UN-REDD Programme 2012).

While specialists have demonstrated how REDD+ has the potential to minimise C02 emissions, it

is not without its problems (Bayrak, Tu and Marafa 2014). Some developing nations may be

suspicious of foreign intrusion in their land use plans. Investigators also highlight operative

Introduction

Forest and trees store carbon and when they are completely cleared or degraded, the stored

carbon has the prospect to be released back into the stratosphere as carbon dioxide and contribute

to climate variation. Deforestation contributes up to 10% to carbon dioxide emission caused by

human actions, according to a 2013 figure from the intergovernmental panel on climate change

(Hoang et al. 2013). Tropic forest now discharge more carbon than they capture, due to

degradation and deforestation, so that they are no longer a carbon sink, according to a study

released in 2017 using satellite data from 2003 to 2014 (GRICC 2018).

REDD+ finance policy

Experts have acknowledged the significance of shielding the forest in confronting climate

change. In reaction, legislators have established a family of dogma collectively known is

reducing emission from deforestation and degradation (REDD) to offers a monetary incentive to

agribusiness, government, and societies to uphold and probably upsurge, rather than minimise

the forest protection (Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2015). Under REDD+, incentives for forest

protection are provided to nations, individual’s landowners, and communities in exchange for

slowing deforestation, and carrying out routines that aid reforestation, and sustainable forest

management (Bayrak, Tu and Marafa 2014). REDD+ policies function over a range of

mechanism, including those managed by the United Nations (UN-REDD) and the World Bank

(the Forest carbon partnership facility) (UN-REDD Programme 2012).

While specialists have demonstrated how REDD+ has the potential to minimise C02 emissions, it

is not without its problems (Bayrak, Tu and Marafa 2014). Some developing nations may be

suspicious of foreign intrusion in their land use plans. Investigators also highlight operative

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration3

apprehensions such as the exertion in measuring and monitoring deforestation proportions or

accrediting variation in deforestation to REDD finance. Variation in local institutional volumes

and local circumstances mean that not all nations that have tropical forests possess the abilities to

address these challenges (Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2016).

REDD+ finance on emerging nations is still fairly restricted in scale. This is major barriers to the

scaling up and hence the effectiveness of REDD+ to minimise from degradation and

deforestation. Estimates of the international cost of REDD+ vary hugely but at least

US$15billion would be required yearly to address humid deforestation across the globe (Lyster,

MacKenzie and McDermott 2013).

In last year, Brazil declared the voluntary promise to minimise its greenhouse gas emission from

36.1% to 38.9% by 2020 and, to this conclusion, such pledge necessitate reducing 80% of the

deforestation in the Amazon tropical forest (Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2016). REDD+. Much

of a doubt on the roles of forests for carbon discharges is due to the lack of consistent

deforestation statistics. The Brazilians’ national institute for space research (INPE) carried on,

since 1988, yearly analyses of deforestation in the Amazon, a zone of approximately 5 million

km2(Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2016). The presence of remarkable info on deforestation permits

researchers to compel the impact of land cover variation to greenhouse gases emission for 40

years (Espinoza and Feather 2011).

Reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration in the Brazilian Amazon

The Amazon area in South America, being hugest nonstop parts of remaining tropical

rain forest in the biosphere, and has a critical part in the worldwide carbon financial plan. The

Brazilian Amazon only comprises more carbon stowed in its biodiversity than the quantity on

apprehensions such as the exertion in measuring and monitoring deforestation proportions or

accrediting variation in deforestation to REDD finance. Variation in local institutional volumes

and local circumstances mean that not all nations that have tropical forests possess the abilities to

address these challenges (Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2016).

REDD+ finance on emerging nations is still fairly restricted in scale. This is major barriers to the

scaling up and hence the effectiveness of REDD+ to minimise from degradation and

deforestation. Estimates of the international cost of REDD+ vary hugely but at least

US$15billion would be required yearly to address humid deforestation across the globe (Lyster,

MacKenzie and McDermott 2013).

In last year, Brazil declared the voluntary promise to minimise its greenhouse gas emission from

36.1% to 38.9% by 2020 and, to this conclusion, such pledge necessitate reducing 80% of the

deforestation in the Amazon tropical forest (Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2016). REDD+. Much

of a doubt on the roles of forests for carbon discharges is due to the lack of consistent

deforestation statistics. The Brazilians’ national institute for space research (INPE) carried on,

since 1988, yearly analyses of deforestation in the Amazon, a zone of approximately 5 million

km2(Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2016). The presence of remarkable info on deforestation permits

researchers to compel the impact of land cover variation to greenhouse gases emission for 40

years (Espinoza and Feather 2011).

Reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration in the Brazilian Amazon

The Amazon area in South America, being hugest nonstop parts of remaining tropical

rain forest in the biosphere, and has a critical part in the worldwide carbon financial plan. The

Brazilian Amazon only comprises more carbon stowed in its biodiversity than the quantity on

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration4

international human-induced CO-emission of a whole decade (Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2016.

Land use routine, whether changing natural sceneries for human usage or varying management

activities on human-dominated lands, have changed a great share of the earth’s land superficial

(Lyster, MacKenzie and McDermott 2013). By dissipating tropical forests, practising subsistence

cultivation, increasing farmland invention or growing urban centres, are altering the scenery in a

universal manner. Most of the dilapidation courses are focused in the eastern and southern parts

of Amazonia (Hoang et al. 2013).

Figure 1: Brazilian amazon map showing (i) pink (non-forested zones; (ii) light blue (forest;

clouds) (iii) yellow and orange (deforestation after 1997 over 2004) (Hoang et al. 2013).

international human-induced CO-emission of a whole decade (Loaiza, Nehren and Gerold 2016.

Land use routine, whether changing natural sceneries for human usage or varying management

activities on human-dominated lands, have changed a great share of the earth’s land superficial

(Lyster, MacKenzie and McDermott 2013). By dissipating tropical forests, practising subsistence

cultivation, increasing farmland invention or growing urban centres, are altering the scenery in a

universal manner. Most of the dilapidation courses are focused in the eastern and southern parts

of Amazonia (Hoang et al. 2013).

Figure 1: Brazilian amazon map showing (i) pink (non-forested zones; (ii) light blue (forest;

clouds) (iii) yellow and orange (deforestation after 1997 over 2004) (Hoang et al. 2013).

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration5

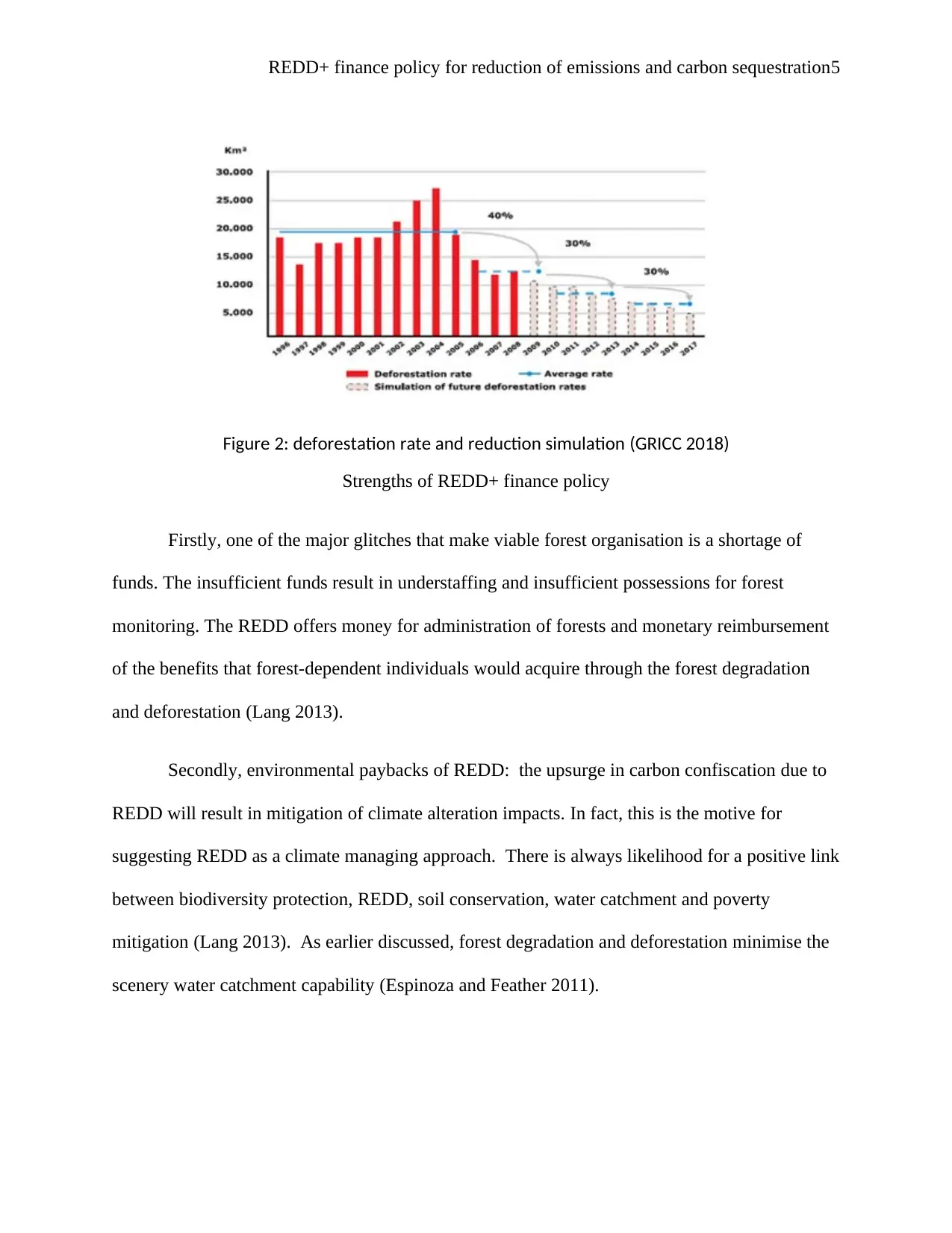

Figure 2: deforestation rate and reduction simulation (GRICC 2018)

Strengths of REDD+ finance policy

Firstly, one of the major glitches that make viable forest organisation is a shortage of

funds. The insufficient funds result in understaffing and insufficient possessions for forest

monitoring. The REDD offers money for administration of forests and monetary reimbursement

of the benefits that forest-dependent individuals would acquire through the forest degradation

and deforestation (Lang 2013).

Secondly, environmental paybacks of REDD: the upsurge in carbon confiscation due to

REDD will result in mitigation of climate alteration impacts. In fact, this is the motive for

suggesting REDD as a climate managing approach. There is always likelihood for a positive link

between biodiversity protection, REDD, soil conservation, water catchment and poverty

mitigation (Lang 2013). As earlier discussed, forest degradation and deforestation minimise the

scenery water catchment capability (Espinoza and Feather 2011).

Figure 2: deforestation rate and reduction simulation (GRICC 2018)

Strengths of REDD+ finance policy

Firstly, one of the major glitches that make viable forest organisation is a shortage of

funds. The insufficient funds result in understaffing and insufficient possessions for forest

monitoring. The REDD offers money for administration of forests and monetary reimbursement

of the benefits that forest-dependent individuals would acquire through the forest degradation

and deforestation (Lang 2013).

Secondly, environmental paybacks of REDD: the upsurge in carbon confiscation due to

REDD will result in mitigation of climate alteration impacts. In fact, this is the motive for

suggesting REDD as a climate managing approach. There is always likelihood for a positive link

between biodiversity protection, REDD, soil conservation, water catchment and poverty

mitigation (Lang 2013). As earlier discussed, forest degradation and deforestation minimise the

scenery water catchment capability (Espinoza and Feather 2011).

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration6

Finally, the REDD can back to poverty mitigation over the provision of employment, the

sale of carbon credits and the sale of other ecological facilities that are improved by an execution

of REDD (Lang 2013).

Weaknesses of REDD+ finance policy

First, ecological versus an economic rate of operation: As a climate change alleviation

approach, REDD falls far inadequate of what is required. Even though REDD is 100% operative,

it will only give to 20% of the required answer to the perils of climate variation. The remaining

80% has to be realised by addressing carbon emission due to other aspects (Sunderlin et al.

2014).

Second, are three-dimensional and sectorial leaks: when there is active REDD in a space,

forest-connected livelihood wants of individuals in the zone may require to be protected from

other parts. Since the full substitution of forestry as sources of livelihood in developed and even

in developing nations is almost unbearable, REDD will always be supplemented by particular

sort of spatial seepage (Sunderlin et al. 2014).

Third, REDD can result in unintentional positive impacts such has populace rise due to

minimised shortage and the subsequent development of social services, upsurge in a populace of

wild animals due to effective forest preservation and more severe unintended fires due to lone

fire breaks (Sheng, Cao, Han and Miao 2016). If the REDD succeeds in defending deciduous

forests to the scope of creating them transform to more evergreen forests, then the difficult of

augmented fire may be stopped (Sheng et al. 2016).

Finally, the REDD can back to poverty mitigation over the provision of employment, the

sale of carbon credits and the sale of other ecological facilities that are improved by an execution

of REDD (Lang 2013).

Weaknesses of REDD+ finance policy

First, ecological versus an economic rate of operation: As a climate change alleviation

approach, REDD falls far inadequate of what is required. Even though REDD is 100% operative,

it will only give to 20% of the required answer to the perils of climate variation. The remaining

80% has to be realised by addressing carbon emission due to other aspects (Sunderlin et al.

2014).

Second, are three-dimensional and sectorial leaks: when there is active REDD in a space,

forest-connected livelihood wants of individuals in the zone may require to be protected from

other parts. Since the full substitution of forestry as sources of livelihood in developed and even

in developing nations is almost unbearable, REDD will always be supplemented by particular

sort of spatial seepage (Sunderlin et al. 2014).

Third, REDD can result in unintentional positive impacts such has populace rise due to

minimised shortage and the subsequent development of social services, upsurge in a populace of

wild animals due to effective forest preservation and more severe unintended fires due to lone

fire breaks (Sheng, Cao, Han and Miao 2016). If the REDD succeeds in defending deciduous

forests to the scope of creating them transform to more evergreen forests, then the difficult of

augmented fire may be stopped (Sheng et al. 2016).

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration7

Fourth, unreliability, insufficiency and complication of REDD finance: centred on

experience with charitable funding for climate alteration, it is going to be hard to acquire enough

voluntary coffers for REDD (Sunderlin et al. 2014).

Finally, the propensity to validate REDD on the base of the lower-end of its charges.

Operation, opportunity and administration cost of REDD are viable reliant on the situations and

the assumptions utilised in the calculations. The REDD costs may hinge on such technical

aspects as how land clearing cost and timber harvesting are handled, what kind of woodland

land is deliberated, how substitution land application are modelled, which carbon mass

approximations are applied and whether rate curves estimate for carbon reduction are planned

(Sunderlin et al. 2014).

Conclusion

Even though REDD may back to viable forest management, poverty reduction,

environmental protection, the full alleviation of climate variation that can result from the fruitful

REDD execution is only a trivial portion of what can be realised through alleviation in the

industrial segments. With an appropriate design and execution, REDD can generate a win-win

condition and can result in a leakage-free everlasting reduction in forest degradation and

deforestation.

Fourth, unreliability, insufficiency and complication of REDD finance: centred on

experience with charitable funding for climate alteration, it is going to be hard to acquire enough

voluntary coffers for REDD (Sunderlin et al. 2014).

Finally, the propensity to validate REDD on the base of the lower-end of its charges.

Operation, opportunity and administration cost of REDD are viable reliant on the situations and

the assumptions utilised in the calculations. The REDD costs may hinge on such technical

aspects as how land clearing cost and timber harvesting are handled, what kind of woodland

land is deliberated, how substitution land application are modelled, which carbon mass

approximations are applied and whether rate curves estimate for carbon reduction are planned

(Sunderlin et al. 2014).

Conclusion

Even though REDD may back to viable forest management, poverty reduction,

environmental protection, the full alleviation of climate variation that can result from the fruitful

REDD execution is only a trivial portion of what can be realised through alleviation in the

industrial segments. With an appropriate design and execution, REDD can generate a win-win

condition and can result in a leakage-free everlasting reduction in forest degradation and

deforestation.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration8

References

Bayrak, M.M., Tu, T.N. and Marafa, L.M., 2014. Creating social safeguards for REDD+:

Lessons learned from benefit sharing mechanisms in Vietnam. Land, 3(3), pp.1037-1058.

[Online]. Retrieved from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/3/3/1037/html, [Accessed on 24

November 2018].

Espinoza L, R.and Feather, C. 2011. The reality of REDD+ in Peru: Between Theory and

Practice. Indigenous Amazonian Peoples’ Analyses and Alternatives, Forest Peoples Forest

Progrmme. [Online]. Retrieved from:

http://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/fpp/files/publication/2011/11/reality-redd-peru-

betweentheory-and-practice-website-english-low-res.pdf, [Accessed on 24 November 2018].

GRICC,. 2018. What is the role of deforestation in climate change and how can ‘Reducing

Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation’ (REDD+) help? Grantham Research Institute on

Climate change. [Online]. Retrieved from: http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/faqs/whats-

redd-and-will-it-help-tackle-climate-change/, [Accessed on 24 November 2018].

Hoang, M.H., Do, T.H., Pham, M.T., van Noordwijk, M. and Minang, P.A., 2013. Benefit

distribution across scales to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation

(REDD+) in Vietnam. Land Use Policy, 31, pp.48-60. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837711001323, [Accessed on 24

November 2018].

References

Bayrak, M.M., Tu, T.N. and Marafa, L.M., 2014. Creating social safeguards for REDD+:

Lessons learned from benefit sharing mechanisms in Vietnam. Land, 3(3), pp.1037-1058.

[Online]. Retrieved from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/3/3/1037/html, [Accessed on 24

November 2018].

Espinoza L, R.and Feather, C. 2011. The reality of REDD+ in Peru: Between Theory and

Practice. Indigenous Amazonian Peoples’ Analyses and Alternatives, Forest Peoples Forest

Progrmme. [Online]. Retrieved from:

http://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/fpp/files/publication/2011/11/reality-redd-peru-

betweentheory-and-practice-website-english-low-res.pdf, [Accessed on 24 November 2018].

GRICC,. 2018. What is the role of deforestation in climate change and how can ‘Reducing

Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation’ (REDD+) help? Grantham Research Institute on

Climate change. [Online]. Retrieved from: http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/faqs/whats-

redd-and-will-it-help-tackle-climate-change/, [Accessed on 24 November 2018].

Hoang, M.H., Do, T.H., Pham, M.T., van Noordwijk, M. and Minang, P.A., 2013. Benefit

distribution across scales to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation

(REDD+) in Vietnam. Land Use Policy, 31, pp.48-60. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837711001323, [Accessed on 24

November 2018].

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration9

Lang, C. 2013. The Warsaw Framework for REDD Plus: The Decision on Summary of

Information on

Safeguards. REDD Monitor. [Online]. Retrieved from:

http://www.redd-monitor.org/2013/12/17/thewarsaw-framework-for-redd-plus-the-decision-on-

summary-of-information-on-safeguards, [Accessed on 24 November 2018].

Loaiza, T., Nehren, U. and Gerold, G., 2015. REDD+ and incentives: An analysis of income

generation in forest-dependent communities of the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve, Ecuador. Applied

Geography, 62, pp.225-236. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0143622815001034,[Accessed on 24

November 2018].

Loaiza, T., Nehren, U. and Gerold, G., 2016. REDD+ implementation in the Ecuadorian

Amazon: Why land configuration and common-pool resources management matter. Forest

Policy and Economics, 70, pp.67-79. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389934116301034,[Accessed, [Accessed on

24 November 2018].

Lyster, R., MacKenzie, C. and McDermott, C. eds., 2013. Law, Tropical forests and carbon: the

case of REDD+. Cambridge University Press. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=J-

8fAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Fisher,+R.%3B+Lyster,+R.+Land+resource+tenure:

+The+rights+of+indigenous+peoples+and+forest+dwellers.+In+Law,+Tropical+Forests,

+and+Carbon:+The+Case+for+REDD%2B,+1st+ed.%3B+Lyster,+R.,+MacKenzie,+C.,

+McDermott,+C.,+Eds.%3B+Cambridge+University+Press:+New+York,+NY,

Lang, C. 2013. The Warsaw Framework for REDD Plus: The Decision on Summary of

Information on

Safeguards. REDD Monitor. [Online]. Retrieved from:

http://www.redd-monitor.org/2013/12/17/thewarsaw-framework-for-redd-plus-the-decision-on-

summary-of-information-on-safeguards, [Accessed on 24 November 2018].

Loaiza, T., Nehren, U. and Gerold, G., 2015. REDD+ and incentives: An analysis of income

generation in forest-dependent communities of the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve, Ecuador. Applied

Geography, 62, pp.225-236. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0143622815001034,[Accessed on 24

November 2018].

Loaiza, T., Nehren, U. and Gerold, G., 2016. REDD+ implementation in the Ecuadorian

Amazon: Why land configuration and common-pool resources management matter. Forest

Policy and Economics, 70, pp.67-79. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389934116301034,[Accessed, [Accessed on

24 November 2018].

Lyster, R., MacKenzie, C. and McDermott, C. eds., 2013. Law, Tropical forests and carbon: the

case of REDD+. Cambridge University Press. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=J-

8fAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Fisher,+R.%3B+Lyster,+R.+Land+resource+tenure:

+The+rights+of+indigenous+peoples+and+forest+dwellers.+In+Law,+Tropical+Forests,

+and+Carbon:+The+Case+for+REDD%2B,+1st+ed.%3B+Lyster,+R.,+MacKenzie,+C.,

+McDermott,+C.,+Eds.%3B+Cambridge+University+Press:+New+York,+NY,

REDD+ finance policy for reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration10

+&ots=DiWSpDhPC0&sig=coM-qANPISynW4iRJMS2rmYvVNQ, [Accessed on 24 November

2018].

Sheng, J., Cao, J., Han, X. and Miao, Z., 2016. Incentive modes and reducing emissions from

deforestation and degradation: who can benefit most?. Journal of cleaner production, 129,

pp.395-409. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652616303109, [Accessed on 24

November 2018].

Sunderlin, W.D., Larson, A.M., Duchelle, A.E., Resosudarmo, I.A.P., Huynh, T.B., Awono, A.

and Dokken, T., 2014. How are REDD+ proponents addressing tenure problems? Evidence from

Brazil, Cameroon, Tanzania, Indonesia, and Vietnam. World Development, 55, pp.37-52.

[Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X13000193, [Accessed on 24

November 2018].

UN-REDD Programme., 2012. The Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Guidelines on

Stakeholder Engagement in REDD+ Readiness with a Focus on the Participation of Indigenous

Peoples and Other Forest-Dependent Communities; FAO: Rome, Italy; UNDP: New York, NY,

USA; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya; [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/sites/fcp/files/2013/May2013/Guidelines%20on

%20Stakeholder%

20Engagement%20April%2020,%202012%20(revision%20of%20March%2025th

%20version).pdf, [Accessed on 24 November 2018].

+&ots=DiWSpDhPC0&sig=coM-qANPISynW4iRJMS2rmYvVNQ, [Accessed on 24 November

2018].

Sheng, J., Cao, J., Han, X. and Miao, Z., 2016. Incentive modes and reducing emissions from

deforestation and degradation: who can benefit most?. Journal of cleaner production, 129,

pp.395-409. [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652616303109, [Accessed on 24

November 2018].

Sunderlin, W.D., Larson, A.M., Duchelle, A.E., Resosudarmo, I.A.P., Huynh, T.B., Awono, A.

and Dokken, T., 2014. How are REDD+ proponents addressing tenure problems? Evidence from

Brazil, Cameroon, Tanzania, Indonesia, and Vietnam. World Development, 55, pp.37-52.

[Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X13000193, [Accessed on 24

November 2018].

UN-REDD Programme., 2012. The Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Guidelines on

Stakeholder Engagement in REDD+ Readiness with a Focus on the Participation of Indigenous

Peoples and Other Forest-Dependent Communities; FAO: Rome, Italy; UNDP: New York, NY,

USA; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya; [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/sites/fcp/files/2013/May2013/Guidelines%20on

%20Stakeholder%

20Engagement%20April%2020,%202012%20(revision%20of%20March%2025th

%20version).pdf, [Accessed on 24 November 2018].

1 out of 10

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.