Consumer Behavior and Marketing Psychology: Survey Sample and Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/19

|14

|15834

|82

Report

AI Summary

This report presents an analysis of a consumer behavior survey, focusing on the factors that influence consumer purchasing decisions. The assignment, completed for the MBA404 course, explores the consumer buying process, including need recognition, information search, and evaluation of alternatives. The survey, conducted using Survey Monkey, includes 10 questions and targets consumers who have recently purchased a chosen product or service. The analysis section examines the driving forces behind consumer behavior, such as perception, attitudes, motivation, and cultural influences, with specific consideration of the Lamborghini Aventador as a case study. The report aims to provide insights into how these factors impact consumer choices and the application of marketing strategies.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rser

Adoption of PHEV/EV in Malaysia: A critical review on predicting

consumer behaviour

Nadia Adnana,⁎, Shahrina Md Nordina, Imran Rahmanb

a Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS (UTP), Department of Management and Humanities,32610 Bandar Seri Iskandar, Perak, Malaysia

b School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Engineering Campus, 14300 Nibong Tebal, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Consumer behaviour

Electric vehicle

Adoption

Intention

Personal norm

Environmental concern

Hyperbolic discounting

PHEV

EV

Malaysia

A B S T R A C T

Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs)/Electric vehicles (EVs)have recently been re-established in the

transportation sector worldwide.These are enhancements over their ancestors in terms of both performance

and electric driving range.Although the uptake ofPHEV/EVs has been noteworthy in a shorttime frame

amongst most governmental strategies, however, adoption is still a challenge. To date, public attitudes towa

PHEV/EVs have been considered under very diverse conceptual frameworks. This paper reviews a growing bo

of peer-reviewed literatures assessing the factors affecting PHEV/EVs adoption.Malaysia is a major energy

consuming country and,given the rapid growth in its economy,the energy consumption levelis expected to

continue growth. Hence, it is imperative that steps are taken to reduce harmful carbon emissions. Consequen

attempts are being initiated to popularise the use of PHEV/EVs as the main mode of transportation. However

is important to take the three main features ofthe Theory ofPlanned Behaviour (TPB) model,namely the

attitude towards the PHEV/EVs’ adoption, Subjective Norm (SN), and Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) int

account. The consumers’ concerns regarding the harmful effect of carbon emissions should be addressed. In

paper, the significance of encouraging the adoption of PHEVs/EVs is explained and some guidelines that migh

be followed in the upcoming researchers are mentioned.Furthermore,the implications for the design of

effective measures to change the frail social and personal norms to choose PHEVs/EVs are also discussed. Th

collective outcome of‘hyperbolic discounting’has a direct effectbetween the consumers’environmental

concern-based intention and the actual adoption of PHEVs/EVs. Hence, this paper is aimed to conceptualise a

framework created by amending the environmentalconcerns towards PHEVs/EVs.This will allow more

academic consideration, and it may direct future researchers towards the empirical findings on environment

concerns and hyperbolic discounting through the proposed conceptual framework.

1. Introduction

The world is going through crucialissues like energy scarcity,air

pollution, and emission ofgreenhouse gas (GHG).Electric Vehicles,

which use both electrical and internal combustion engines for propul-

sion purposes,appear to be a very promising prospect [1].Moreover,

PHEVs/EVs are presently emerging as an answerfor the issue of

reliance on traditional fuels, emissions of growing CO2, as well as other

eco-friendly concerns [2]. Hence, this sort of vehicle offers an

advantage in the questto reduce carbon emissions by as much as

30–50%, and be able to attain 40–60% improvement in fuel efficiency.

[3–5] mentioned that these figures are provided by the manufacturers.

Though, Bonges and Lusk [6] stated that in actual fact, they are going

to be somewhat on the lower side. Several researchers have proved that

a great amount of reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and the

increasing dependence on oil could be accomplished by the electrifica-

tion of the transport sector which further needs proper understanding

and adoption from the consumer's point of view [7,8].Certainly,the

emergence of Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs) has received substantial

industrial accomplishment starting from the last decade. However, all

the vehicles are categorised into 3 major groups,such as Internal

Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICEVs), Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs),

and All-Electric Vehicles (AEVs) [9,10].Moreover,the very recently

introduced Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, PHEVs, have the potential

to improve the totalfuel efficiency.Nonetheless,Rahman et al.[11]

specified that a PHEV/EV has less CO2 emission and its helps towards

environmentalsustainability.Nevertheless,Schuitema et al. [12]

argued that the disadvantage of PHEV/EV batteries is that they cannot

offer the same mileage that a pure EVs would offer as batteries are

easily drained off for PHEVs. Furthermore, Hosseini et al. [13] claimed

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.121

Received 6 March 2016; Received in revised form 30 November 2016; Accepted 18 January 2017

⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +60169101486; fax:+6053654075.

E-mail addresses: nadia.adnan233@gmail.com (N. Adnan), shahrina_mnordin@petronas.com.my (S.M. Nordin), imran.iutoic@gmail.com (I. Rahman).

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

Available online 24 January 2017

1364-0321/ © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

MARK

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rser

Adoption of PHEV/EV in Malaysia: A critical review on predicting

consumer behaviour

Nadia Adnana,⁎, Shahrina Md Nordina, Imran Rahmanb

a Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS (UTP), Department of Management and Humanities,32610 Bandar Seri Iskandar, Perak, Malaysia

b School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Engineering Campus, 14300 Nibong Tebal, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Consumer behaviour

Electric vehicle

Adoption

Intention

Personal norm

Environmental concern

Hyperbolic discounting

PHEV

EV

Malaysia

A B S T R A C T

Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs)/Electric vehicles (EVs)have recently been re-established in the

transportation sector worldwide.These are enhancements over their ancestors in terms of both performance

and electric driving range.Although the uptake ofPHEV/EVs has been noteworthy in a shorttime frame

amongst most governmental strategies, however, adoption is still a challenge. To date, public attitudes towa

PHEV/EVs have been considered under very diverse conceptual frameworks. This paper reviews a growing bo

of peer-reviewed literatures assessing the factors affecting PHEV/EVs adoption.Malaysia is a major energy

consuming country and,given the rapid growth in its economy,the energy consumption levelis expected to

continue growth. Hence, it is imperative that steps are taken to reduce harmful carbon emissions. Consequen

attempts are being initiated to popularise the use of PHEV/EVs as the main mode of transportation. However

is important to take the three main features ofthe Theory ofPlanned Behaviour (TPB) model,namely the

attitude towards the PHEV/EVs’ adoption, Subjective Norm (SN), and Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) int

account. The consumers’ concerns regarding the harmful effect of carbon emissions should be addressed. In

paper, the significance of encouraging the adoption of PHEVs/EVs is explained and some guidelines that migh

be followed in the upcoming researchers are mentioned.Furthermore,the implications for the design of

effective measures to change the frail social and personal norms to choose PHEVs/EVs are also discussed. Th

collective outcome of‘hyperbolic discounting’has a direct effectbetween the consumers’environmental

concern-based intention and the actual adoption of PHEVs/EVs. Hence, this paper is aimed to conceptualise a

framework created by amending the environmentalconcerns towards PHEVs/EVs.This will allow more

academic consideration, and it may direct future researchers towards the empirical findings on environment

concerns and hyperbolic discounting through the proposed conceptual framework.

1. Introduction

The world is going through crucialissues like energy scarcity,air

pollution, and emission ofgreenhouse gas (GHG).Electric Vehicles,

which use both electrical and internal combustion engines for propul-

sion purposes,appear to be a very promising prospect [1].Moreover,

PHEVs/EVs are presently emerging as an answerfor the issue of

reliance on traditional fuels, emissions of growing CO2, as well as other

eco-friendly concerns [2]. Hence, this sort of vehicle offers an

advantage in the questto reduce carbon emissions by as much as

30–50%, and be able to attain 40–60% improvement in fuel efficiency.

[3–5] mentioned that these figures are provided by the manufacturers.

Though, Bonges and Lusk [6] stated that in actual fact, they are going

to be somewhat on the lower side. Several researchers have proved that

a great amount of reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and the

increasing dependence on oil could be accomplished by the electrifica-

tion of the transport sector which further needs proper understanding

and adoption from the consumer's point of view [7,8].Certainly,the

emergence of Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs) has received substantial

industrial accomplishment starting from the last decade. However, all

the vehicles are categorised into 3 major groups,such as Internal

Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICEVs), Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs),

and All-Electric Vehicles (AEVs) [9,10].Moreover,the very recently

introduced Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, PHEVs, have the potential

to improve the totalfuel efficiency.Nonetheless,Rahman et al.[11]

specified that a PHEV/EV has less CO2 emission and its helps towards

environmentalsustainability.Nevertheless,Schuitema et al. [12]

argued that the disadvantage of PHEV/EV batteries is that they cannot

offer the same mileage that a pure EVs would offer as batteries are

easily drained off for PHEVs. Furthermore, Hosseini et al. [13] claimed

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.121

Received 6 March 2016; Received in revised form 30 November 2016; Accepted 18 January 2017

⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +60169101486; fax:+6053654075.

E-mail addresses: nadia.adnan233@gmail.com (N. Adnan), shahrina_mnordin@petronas.com.my (S.M. Nordin), imran.iutoic@gmail.com (I. Rahman).

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

Available online 24 January 2017

1364-0321/ © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

MARK

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

that there are very few plug-in facilities that such vehicles may require.

Rezvani et al. [14] highlighted that the PHEV/EV is the combination of

a gasoline or diesel engine with an electric motor and it also carries a

large rechargeable battery.Khooban et al.[15] emphasised that since

they use less gas,they also cost less to fuel: driving a PHEV can save

hundreds of dollars a year in gasoline and diesel costs and helps to save

the environmental sustainability. In order to gain the main goal of this

study, there is a need to resolve the shortcomings, i.e., limited mileage

offered by the batteries as well as the inability to charge the batteries

with the frequency required,that have hindered the acceptability of

PHEVs/EVs [16]. However,Johansson and Mattsson [17] suggested

that the adoption of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles is gaining

popularity and increasing acceptability.Because of EVs/PHEVs being

more practicable,they are becoming more popular in the developed

nations,such as the U.S.,Japan, and Europe [18].However,in the

context of the developing countries likewise, such as in Malaysia where

the government has noted the advantages offered by PHEVs/EVs and

has taken measures to promote its use [19].

The motivation behind this study based on the Malaysian vision

2020 whereas,Dato Seri Dr. Mahathir Bin Mohamad stated that

sustainability is critical concerns for the development of each country

worldwide, especiallyin Malaysia (Malaysian: The Way Forward

Vision2020). Malaysian economic development has been coupled with

rapid environmentaldegradation.With the rapid increase of EVs/

PHEVs more attention should be paid to whether they would be

reinforced or structured.As such, a vehicle with identicalemission

factors of a particular pollutant could have different health impacts and

environmentaljustice implications,depending on the location ofthe

pollution source. Malaysian government focuses more of EV/PHEV in

order to reduce the environmentalpollution which caused by the

transportation sector.

The Malaysian higher authority had fixed the goal of 500,000

PHEVs/EVs being driven on Malaysian roads at the end of 2015 and

around five million by the year 2020 (The National Council of Malaysia,

2012). In order to promote the usage of PHEVs/EVs, the government

has initiated a number ofpolicies,including subsidising the sale of

PHEVs/EVs. The government has also paid special consideration to the

advancement and manufacture of PHEVs/EVs in the eleventh 5 year-

long Plan. The government has also planned to invest RMB 100 billion

($ 16 billion) for the improvement of technologies in the 25 yearlong

planning [20,21].The government did indicate a ‘10 cities-thousand

Vehicles’ initiative in 2009 to give a boost to the growth of PHEVs/EVs

and to popularise their use. However, the consumer reaction fell short

of expectations [22], [20]. According to the Malaysian Associations of

Automobile ManufacturersAssociations,the cumulative saleswere

27,400 EVs in 2012. Of these, 23,000 were acquired by the governing

agency and the community service sector whilst 4400 were bought by

individuals.It was seen thatthe ordinary Malaysian considered the

performance of the conventional vehicle to be superior to the PHEV/

EV. The consumer did,however,show his/her preference to have a

PHEV/EV as a second vehicle [20]. Currently, it is estimated that 13%

of households have a second car. This figure may rise as the economy

continues to expand.Likewise, the PHEV/EV technology may also

improve and consumers may prefer the new innovations [23].In any

case,there are bright prospects of PHEVs/EVs gaining popularity in

Malaysia.

The penetration of electric vehicles into the market of Malaysia has

directed the vehicular industry to an entirely new dimension which is

based on less dependency on fueland improved fuelefficiency [14].

Though Falvo et al.[24] declared that electric vehicles may decrease

the overall tailpipe emission,the benefits in the contextof entire

emission are slightly marginal if the traditional power generation still

uses coalas a primary source.So, the governing agency has substan-

tially sponsored the vastusage of alternative energy like solar and

biomass in order to lessen the dependency on coal [25] Although the

use of PHEVs/EVs as a cleaner alternative [26] is well sponsored by the

government through many programs and policies,less information is

provided from the social perspective regarding the PHEV/EV's public

acceptance [27]. As the exposure to PHEVs/EVs is comparatively new

in Malaysia, there has been no former research study oranalysis

carried out on Malaysian drivers to measure the public acceptance as

well as user intentions of this innovative and recent technology [9,20].

Actually, communalacceptance appears to be one ofthe powerful

impedimentsfor successfulmarket diffusion and can hinder the

improvement of Malaysian PHEV/EV adoption.Researchers propose

that the consequences offera noteworthy influence in offering the

visions to benefit the policy makers and consumers to better compre-

hend the significance offortifying the environmentalsustainability

ingenuities to recover the achievement of such initiatives [28,29].

2. Contribution of this study

PHEVs/EVs require funding from different governmental agencies

for successful market penetration [30,31]. Although, Sang and Bekhet

[20] suggested thatit is important that customers ‘also targetfor

buying PHEVs/EVs. Many researchers have studied the intention of

customersconsidering theirpurchase of environment-friendly cars

[9,32,33]. For example, Ahmad and Tahar [34] discovered the affecting

factors for the adoption behaviouramongst the PHEV consumer

community.In 2013, Schuitema et al.explored the effect of the EV's

adoption intention due to private vehicle owners’perception of EVs’

qualities. Ahn et al. [35] presented a review to examine the intention of

consumers to accept the PHEV; as well, they noticed some vital factors

influencing the adoption intention of consumers, such as performance

features,economicbenefits,environmentalconsciousnessand the

psychologicalrequirements.PHEV characteristics are thatthey are

rechargeable by plugging in, have a higher electric drive during charge

depletion period and reduced refueling.Whilst the characteristics of

the BEV are: only plug-in recharge,purely electric mode,and no

refueling.This study is focused exclusively on introducing the experi-

ence of Malaysians on the adoption ofPHEVs/EVs. This study has

motivated the researchers in a rigorous behavioural framework on the

basis of the TPB literature by signifying the presence of a reasoning

prejudice and hyperbolic discounting (Given 2 similar type of rewards,

people show a preference for the one that arrives sooner instead of

later) to possibly increase the overall TPB predictability.Thus produ-

cing deeper knowledge about the internal and external motivations of

environmentalconcern amongstMalaysian consumerstowards the

adoption of the PHEV/EV. To date, this study comprises5 main

segments.The “Literature review”section givesdetailed literature

Nomenclature

GHG Greenhouse gas

EVs Electric vehicles

HEVs Hybrid electric vehicles

PHEVs Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles

BEVs Battery electric vehicles

AFVs Alternative fuel vehicles

ICEVs Internal combustion engine vehicles

AEVs All-electric vehicles

HEVs Hybrid electric vehicles

TRA Theory of Reasoned Action

TPB Theory of planned behaviour

PBC Perceived behavioural control

EC Environment concern

SN Subjective Norm

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

850

Rezvani et al. [14] highlighted that the PHEV/EV is the combination of

a gasoline or diesel engine with an electric motor and it also carries a

large rechargeable battery.Khooban et al.[15] emphasised that since

they use less gas,they also cost less to fuel: driving a PHEV can save

hundreds of dollars a year in gasoline and diesel costs and helps to save

the environmental sustainability. In order to gain the main goal of this

study, there is a need to resolve the shortcomings, i.e., limited mileage

offered by the batteries as well as the inability to charge the batteries

with the frequency required,that have hindered the acceptability of

PHEVs/EVs [16]. However,Johansson and Mattsson [17] suggested

that the adoption of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles is gaining

popularity and increasing acceptability.Because of EVs/PHEVs being

more practicable,they are becoming more popular in the developed

nations,such as the U.S.,Japan, and Europe [18].However,in the

context of the developing countries likewise, such as in Malaysia where

the government has noted the advantages offered by PHEVs/EVs and

has taken measures to promote its use [19].

The motivation behind this study based on the Malaysian vision

2020 whereas,Dato Seri Dr. Mahathir Bin Mohamad stated that

sustainability is critical concerns for the development of each country

worldwide, especiallyin Malaysia (Malaysian: The Way Forward

Vision2020). Malaysian economic development has been coupled with

rapid environmentaldegradation.With the rapid increase of EVs/

PHEVs more attention should be paid to whether they would be

reinforced or structured.As such, a vehicle with identicalemission

factors of a particular pollutant could have different health impacts and

environmentaljustice implications,depending on the location ofthe

pollution source. Malaysian government focuses more of EV/PHEV in

order to reduce the environmentalpollution which caused by the

transportation sector.

The Malaysian higher authority had fixed the goal of 500,000

PHEVs/EVs being driven on Malaysian roads at the end of 2015 and

around five million by the year 2020 (The National Council of Malaysia,

2012). In order to promote the usage of PHEVs/EVs, the government

has initiated a number ofpolicies,including subsidising the sale of

PHEVs/EVs. The government has also paid special consideration to the

advancement and manufacture of PHEVs/EVs in the eleventh 5 year-

long Plan. The government has also planned to invest RMB 100 billion

($ 16 billion) for the improvement of technologies in the 25 yearlong

planning [20,21].The government did indicate a ‘10 cities-thousand

Vehicles’ initiative in 2009 to give a boost to the growth of PHEVs/EVs

and to popularise their use. However, the consumer reaction fell short

of expectations [22], [20]. According to the Malaysian Associations of

Automobile ManufacturersAssociations,the cumulative saleswere

27,400 EVs in 2012. Of these, 23,000 were acquired by the governing

agency and the community service sector whilst 4400 were bought by

individuals.It was seen thatthe ordinary Malaysian considered the

performance of the conventional vehicle to be superior to the PHEV/

EV. The consumer did,however,show his/her preference to have a

PHEV/EV as a second vehicle [20]. Currently, it is estimated that 13%

of households have a second car. This figure may rise as the economy

continues to expand.Likewise, the PHEV/EV technology may also

improve and consumers may prefer the new innovations [23].In any

case,there are bright prospects of PHEVs/EVs gaining popularity in

Malaysia.

The penetration of electric vehicles into the market of Malaysia has

directed the vehicular industry to an entirely new dimension which is

based on less dependency on fueland improved fuelefficiency [14].

Though Falvo et al.[24] declared that electric vehicles may decrease

the overall tailpipe emission,the benefits in the contextof entire

emission are slightly marginal if the traditional power generation still

uses coalas a primary source.So, the governing agency has substan-

tially sponsored the vastusage of alternative energy like solar and

biomass in order to lessen the dependency on coal [25] Although the

use of PHEVs/EVs as a cleaner alternative [26] is well sponsored by the

government through many programs and policies,less information is

provided from the social perspective regarding the PHEV/EV's public

acceptance [27]. As the exposure to PHEVs/EVs is comparatively new

in Malaysia, there has been no former research study oranalysis

carried out on Malaysian drivers to measure the public acceptance as

well as user intentions of this innovative and recent technology [9,20].

Actually, communalacceptance appears to be one ofthe powerful

impedimentsfor successfulmarket diffusion and can hinder the

improvement of Malaysian PHEV/EV adoption.Researchers propose

that the consequences offera noteworthy influence in offering the

visions to benefit the policy makers and consumers to better compre-

hend the significance offortifying the environmentalsustainability

ingenuities to recover the achievement of such initiatives [28,29].

2. Contribution of this study

PHEVs/EVs require funding from different governmental agencies

for successful market penetration [30,31]. Although, Sang and Bekhet

[20] suggested thatit is important that customers ‘also targetfor

buying PHEVs/EVs. Many researchers have studied the intention of

customersconsidering theirpurchase of environment-friendly cars

[9,32,33]. For example, Ahmad and Tahar [34] discovered the affecting

factors for the adoption behaviouramongst the PHEV consumer

community.In 2013, Schuitema et al.explored the effect of the EV's

adoption intention due to private vehicle owners’perception of EVs’

qualities. Ahn et al. [35] presented a review to examine the intention of

consumers to accept the PHEV; as well, they noticed some vital factors

influencing the adoption intention of consumers, such as performance

features,economicbenefits,environmentalconsciousnessand the

psychologicalrequirements.PHEV characteristics are thatthey are

rechargeable by plugging in, have a higher electric drive during charge

depletion period and reduced refueling.Whilst the characteristics of

the BEV are: only plug-in recharge,purely electric mode,and no

refueling.This study is focused exclusively on introducing the experi-

ence of Malaysians on the adoption ofPHEVs/EVs. This study has

motivated the researchers in a rigorous behavioural framework on the

basis of the TPB literature by signifying the presence of a reasoning

prejudice and hyperbolic discounting (Given 2 similar type of rewards,

people show a preference for the one that arrives sooner instead of

later) to possibly increase the overall TPB predictability.Thus produ-

cing deeper knowledge about the internal and external motivations of

environmentalconcern amongstMalaysian consumerstowards the

adoption of the PHEV/EV. To date, this study comprises5 main

segments.The “Literature review”section givesdetailed literature

Nomenclature

GHG Greenhouse gas

EVs Electric vehicles

HEVs Hybrid electric vehicles

PHEVs Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles

BEVs Battery electric vehicles

AFVs Alternative fuel vehicles

ICEVs Internal combustion engine vehicles

AEVs All-electric vehicles

HEVs Hybrid electric vehicles

TRA Theory of Reasoned Action

TPB Theory of planned behaviour

PBC Perceived behavioural control

EC Environment concern

SN Subjective Norm

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

850

studies directly linked to the extended TPB model.Grounded in this

specific review study,firstly, a detailed discussion on the conceptual

framework has been provided followed by the suggestion of hypotheses

in the “Conceptual framework and research hypotheses” segment.

3. Literature review

3.1. Adoption of PHEVs/EVs

A Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV)/Electric Vehicle (EV) is a

car that utilises 2 unlike sources ofpower,which are a battery and

petrol/ diesel. In modern days, electric vehicles are regarded as one of

the most state-of-the-art innovations in the automotive business.As

the first EV in the world, Toyota Prius was produced worldwide early in

the year 2000. Here, Fig. 1 shows petrol versus electric vehicle emission

in a graph.The results are certainly clear,in that the better the fuel

economy of a traditional car (running on petrol), the lower its

emissions willbe. Regarding electric vehicles,the major difference is

the source of electricity. The lowest emissions by a distance are electric

vehicles that use solar energy.

Various governmental efforts worldwide have already been initiated

in order to reduce CO2 emissions.Whereas,there is an increasing

literature concentrating on CO2 emissions which influence financial

incentives on the sales of electric vehicles [36].Nevertheless,author

Zhang et al. [21] concluded thatthere is no indication of lawful

agencies’ encouragements as an influential factor in the electric vehicle

purchase by a statistical investigation carried out in Nanjing, China. In

contrast,Sierzchula et al.[37] found financial incentives as a slightly

positive as wellas statistically influenced.They carried out a multi-

national research (statisticalpoint of view) study of the elements

influencing the rates ofadoption towards Electric Vehicles for thirty

countries in the year 2012.According to Graham-Rowe etal. [33],

incentives less than two thousand dollars had a very little influence

towards the adoption of the PHEV/EV. In the Asia Pacific region, there

are various national-levelinitiatives and programs to promote the

awarenessof electric vehicles(EVs). These programs include the

establishmentof aggressive goals,subsidies for EV purchasers,re-

search and development support and demonstration projects,regula-

tion, tax incentives,and standardization,and public education pro-

grams. According to a new report from Pike Research, these initiatives

will help fuela burgeoning market for PHEVs within the region,and

cumulative sales of PHEV and AEV will exceed 1.4 million units in Asia

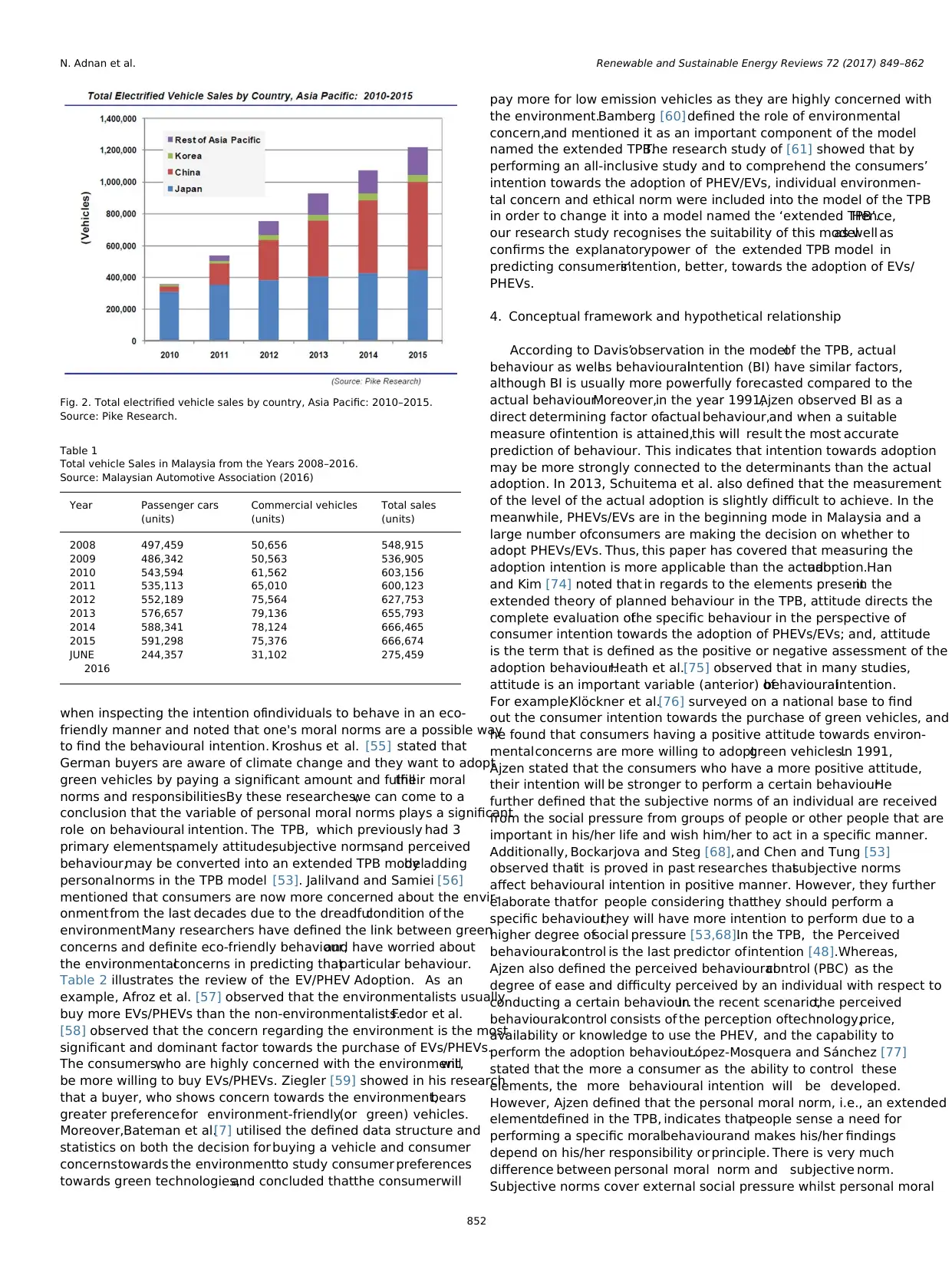

Pacific region during the period from 2010 to 2015. Here, Fig. 2 sums

up the core outcomes conducted by ‘Pike Research’by displaying the

total electrified vehicle sales by country, Asia Pacific.

Moreover, the overall sales of PHEVs/EVs in Malaysia are projected

to rise in the next few years, mainly becauseof the increasing

popularity of hybrid vehicles,increasing awareness amongstconsu-

mers towards PHEV/EV extended incentives of tax by the government

of Malaysia,and the latest model promoted by vehicle manufacturing

companies.Moreover,PHEVs/EVs are designed to deliver better in

terms of fuel efficiency [38,39] and cost savings (The Star Newspaper,

2008). Moreover, in 2012, the overall trades of PHEVs/EVs in Malaysia

were about 15,355 units as related to 8334 units in the year 2011 (The

Star Newspaper, 2013). The topmost 3 PHEV/EV suppliers were Lexus

(266 units), Toyota (2456 units) and Honda (4595 units) [40]. PHEVs/

EVs in Malaysia are yet to be considered very new in the automotive

industry unlike Japan, USA or Europe [41]. In emerging countries like

Malaysia,the shift from traditionalvehicles to PHEVs/EVs requires

taking an extended time as there are vast challenges and obstacles that

must be tackled by the government officials [20,42]. For the establish-

ment of an appropriate as well as a sustainable commercial model for

the PHEV/EV trade, the automobile industry and the government

should harmonise closely to dealwith those technicalglitches.In

addition, regulations, policies, and inducements are some of the main

drivers for the developmentof PHEVs/EVs amongst consumers.

Though the trades ofPHEVs/EVs are predicted to be improved in

the coming years, the overall trades in Malaysia are still measured very

low compared to Non-hybrid vehicles in the automotive industry.At

the same time, the penetration rate was still very low in the years 2011

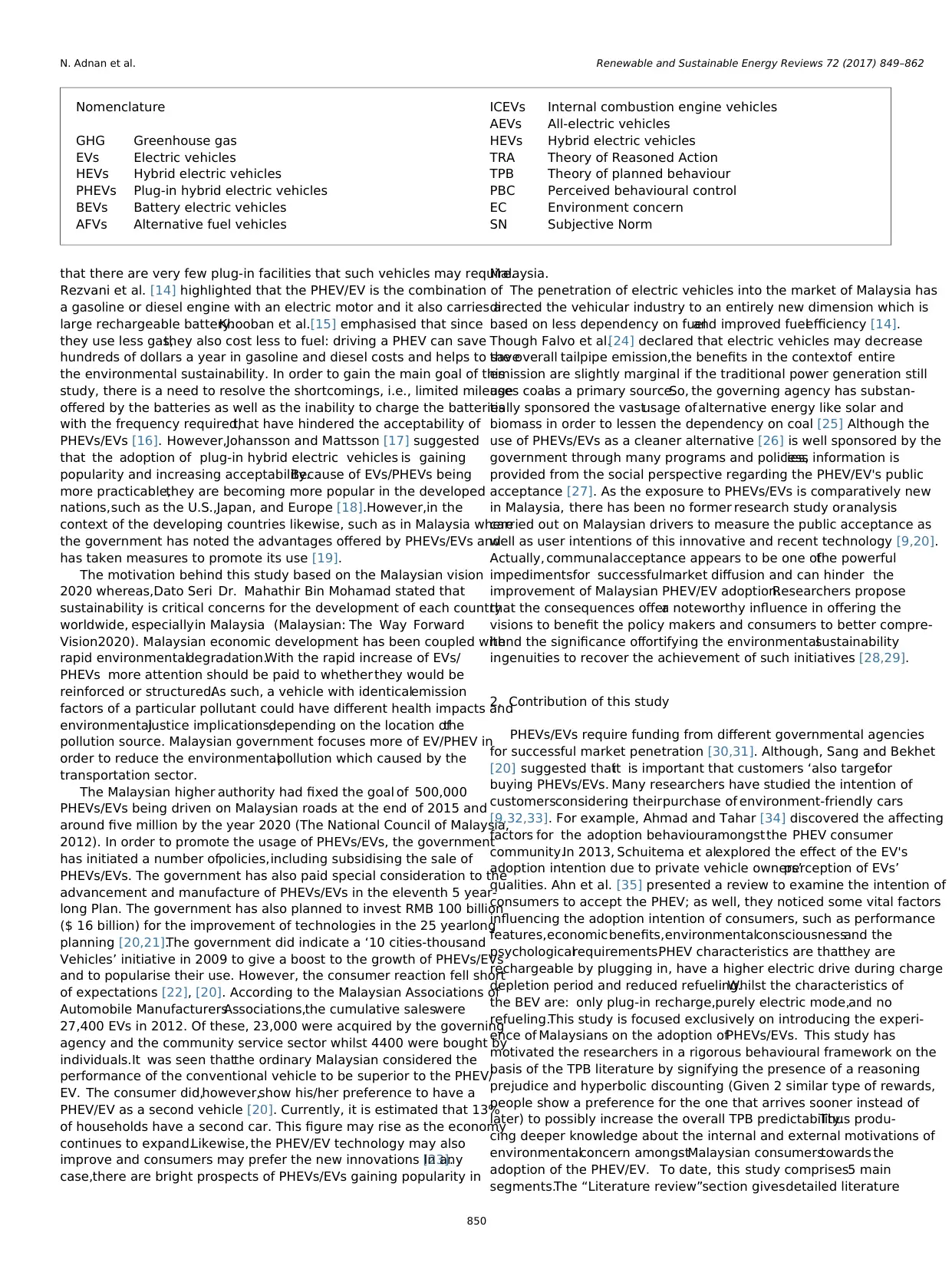

(1.39%) and 2012 (2.45) (Hong et al. [41]). Table 1 below indicates the

total vehicle sales in Malaysia from the years 2008–2016.

Although there is an increasing demand forgreen products in

Malaysia [43,44] the actual purchase level is low in Malaysia. Again, in

spite of the increase in the hybrid car sales year by year, the hybrid car

has only taken up 3% (approximately 50,000 units sold since 2008) of

the market share in the automotive industry [45].Besides that,as a

comparison with an ASEAN partner country,Thailand, the ASEAN

automotive marketleader,there were 37,530 units ofa hybrid car

registered in Thailand [46]. However, only 18,967 units of hybrid cars

were sold in Malaysia in 2013 [47].On the other hand,the sale of

hybrid cars in the US (which was available for more than fifteen years)

hit around 88,000 units in the year of 2014 [47]. So, in recent years, the

PHEV/EV has shown greater market success in Western countries. One

of the main reasons for this success is linked with the consumption

behaviour ofthe consumers (Adnan etal. [2]). Thus, this study is

carried out with the aim to use the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

which explains the prediction, description, and explanation in affecting

consumers’consumption behaviour.Apart from that, attitudes have

been included as a mediator in this study which will contribute as a new

dimension for the theory of consumption value.

3.2. Theory based on the Adoption of the electric vehicle

The behavioural intention and behaviour are widely defined in the

Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [48] which is an extension of the

Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) model.Actual behaviour is found

from this modelby defining the behaviouralintention.After that,3

elementscontrol the behaviouralintention: subjective norm (SN),

attitude towardsthe behaviour,and perceived behaviouralcontrol

(PBC) [48]. Now, researchers also utilise the TPB structure in order to

discover eco-friendly and green consumer behaviour. For instance, the

TPB model proposed by [49] extracts consumers’behaviouralinten-

tions towards waste recycling,and defines consumer recycling inten-

tion. Macintosh and Lockshin [50] and Sigurdardottir et al. [51]

utilised the TPB to predict the purposes of teenagers to commute by

car or bicycle. M.-F. Chen and Tung [53] worked on the TPB model by

means of psychologicalfactors, for example,attitudesand norms,

having a major influence on green cars acceptance. All these research

researchers concluded that the TPB model is an appropriate concept to

predict eco-friendly communication and increase the overall explana-

tory power by adding some variableslike moral beliefs [52]. For

example,Beck and Ajzen as well as other researchers[49,53,54]

specified thatthe TBP's explanatory powerhas been increased by

personal approaches of moral accountability or individual moral ethics

Fig. 1. Petrol versus Electric vehicle emission.

Source: DEFRA (emission factors), EPA (ratings), IPCC. Year: 2014.

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

851

specific review study,firstly, a detailed discussion on the conceptual

framework has been provided followed by the suggestion of hypotheses

in the “Conceptual framework and research hypotheses” segment.

3. Literature review

3.1. Adoption of PHEVs/EVs

A Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV)/Electric Vehicle (EV) is a

car that utilises 2 unlike sources ofpower,which are a battery and

petrol/ diesel. In modern days, electric vehicles are regarded as one of

the most state-of-the-art innovations in the automotive business.As

the first EV in the world, Toyota Prius was produced worldwide early in

the year 2000. Here, Fig. 1 shows petrol versus electric vehicle emission

in a graph.The results are certainly clear,in that the better the fuel

economy of a traditional car (running on petrol), the lower its

emissions willbe. Regarding electric vehicles,the major difference is

the source of electricity. The lowest emissions by a distance are electric

vehicles that use solar energy.

Various governmental efforts worldwide have already been initiated

in order to reduce CO2 emissions.Whereas,there is an increasing

literature concentrating on CO2 emissions which influence financial

incentives on the sales of electric vehicles [36].Nevertheless,author

Zhang et al. [21] concluded thatthere is no indication of lawful

agencies’ encouragements as an influential factor in the electric vehicle

purchase by a statistical investigation carried out in Nanjing, China. In

contrast,Sierzchula et al.[37] found financial incentives as a slightly

positive as wellas statistically influenced.They carried out a multi-

national research (statisticalpoint of view) study of the elements

influencing the rates ofadoption towards Electric Vehicles for thirty

countries in the year 2012.According to Graham-Rowe etal. [33],

incentives less than two thousand dollars had a very little influence

towards the adoption of the PHEV/EV. In the Asia Pacific region, there

are various national-levelinitiatives and programs to promote the

awarenessof electric vehicles(EVs). These programs include the

establishmentof aggressive goals,subsidies for EV purchasers,re-

search and development support and demonstration projects,regula-

tion, tax incentives,and standardization,and public education pro-

grams. According to a new report from Pike Research, these initiatives

will help fuela burgeoning market for PHEVs within the region,and

cumulative sales of PHEV and AEV will exceed 1.4 million units in Asia

Pacific region during the period from 2010 to 2015. Here, Fig. 2 sums

up the core outcomes conducted by ‘Pike Research’by displaying the

total electrified vehicle sales by country, Asia Pacific.

Moreover, the overall sales of PHEVs/EVs in Malaysia are projected

to rise in the next few years, mainly becauseof the increasing

popularity of hybrid vehicles,increasing awareness amongstconsu-

mers towards PHEV/EV extended incentives of tax by the government

of Malaysia,and the latest model promoted by vehicle manufacturing

companies.Moreover,PHEVs/EVs are designed to deliver better in

terms of fuel efficiency [38,39] and cost savings (The Star Newspaper,

2008). Moreover, in 2012, the overall trades of PHEVs/EVs in Malaysia

were about 15,355 units as related to 8334 units in the year 2011 (The

Star Newspaper, 2013). The topmost 3 PHEV/EV suppliers were Lexus

(266 units), Toyota (2456 units) and Honda (4595 units) [40]. PHEVs/

EVs in Malaysia are yet to be considered very new in the automotive

industry unlike Japan, USA or Europe [41]. In emerging countries like

Malaysia,the shift from traditionalvehicles to PHEVs/EVs requires

taking an extended time as there are vast challenges and obstacles that

must be tackled by the government officials [20,42]. For the establish-

ment of an appropriate as well as a sustainable commercial model for

the PHEV/EV trade, the automobile industry and the government

should harmonise closely to dealwith those technicalglitches.In

addition, regulations, policies, and inducements are some of the main

drivers for the developmentof PHEVs/EVs amongst consumers.

Though the trades ofPHEVs/EVs are predicted to be improved in

the coming years, the overall trades in Malaysia are still measured very

low compared to Non-hybrid vehicles in the automotive industry.At

the same time, the penetration rate was still very low in the years 2011

(1.39%) and 2012 (2.45) (Hong et al. [41]). Table 1 below indicates the

total vehicle sales in Malaysia from the years 2008–2016.

Although there is an increasing demand forgreen products in

Malaysia [43,44] the actual purchase level is low in Malaysia. Again, in

spite of the increase in the hybrid car sales year by year, the hybrid car

has only taken up 3% (approximately 50,000 units sold since 2008) of

the market share in the automotive industry [45].Besides that,as a

comparison with an ASEAN partner country,Thailand, the ASEAN

automotive marketleader,there were 37,530 units ofa hybrid car

registered in Thailand [46]. However, only 18,967 units of hybrid cars

were sold in Malaysia in 2013 [47].On the other hand,the sale of

hybrid cars in the US (which was available for more than fifteen years)

hit around 88,000 units in the year of 2014 [47]. So, in recent years, the

PHEV/EV has shown greater market success in Western countries. One

of the main reasons for this success is linked with the consumption

behaviour ofthe consumers (Adnan etal. [2]). Thus, this study is

carried out with the aim to use the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

which explains the prediction, description, and explanation in affecting

consumers’consumption behaviour.Apart from that, attitudes have

been included as a mediator in this study which will contribute as a new

dimension for the theory of consumption value.

3.2. Theory based on the Adoption of the electric vehicle

The behavioural intention and behaviour are widely defined in the

Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [48] which is an extension of the

Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) model.Actual behaviour is found

from this modelby defining the behaviouralintention.After that,3

elementscontrol the behaviouralintention: subjective norm (SN),

attitude towardsthe behaviour,and perceived behaviouralcontrol

(PBC) [48]. Now, researchers also utilise the TPB structure in order to

discover eco-friendly and green consumer behaviour. For instance, the

TPB model proposed by [49] extracts consumers’behaviouralinten-

tions towards waste recycling,and defines consumer recycling inten-

tion. Macintosh and Lockshin [50] and Sigurdardottir et al. [51]

utilised the TPB to predict the purposes of teenagers to commute by

car or bicycle. M.-F. Chen and Tung [53] worked on the TPB model by

means of psychologicalfactors, for example,attitudesand norms,

having a major influence on green cars acceptance. All these research

researchers concluded that the TPB model is an appropriate concept to

predict eco-friendly communication and increase the overall explana-

tory power by adding some variableslike moral beliefs [52]. For

example,Beck and Ajzen as well as other researchers[49,53,54]

specified thatthe TBP's explanatory powerhas been increased by

personal approaches of moral accountability or individual moral ethics

Fig. 1. Petrol versus Electric vehicle emission.

Source: DEFRA (emission factors), EPA (ratings), IPCC. Year: 2014.

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

851

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

when inspecting the intention ofindividuals to behave in an eco-

friendly manner and noted that one's moral norms are a possible way

to find the behavioural intention. Kroshus et al. [55] stated that

German buyers are aware of climate change and they want to adopt

green vehicles by paying a significant amount and fulfilltheir moral

norms and responsibilities.By these researches,we can come to a

conclusion that the variable of personal moral norms plays a significant

role on behavioural intention. The TPB, which previously had 3

primary elements,namely attitude,subjective norms,and perceived

behaviour,may be converted into an extended TPB modelby adding

personalnorms in the TPB model [53]. Jalilvand and Samiei [56]

mentioned that consumers are now more concerned about the envir-

onmentfrom the last decades due to the dreadfulcondition of the

environment.Many researchers have defined the link between green

concerns and definite eco-friendly behaviour,and have worried about

the environmentalconcerns in predicting thatparticular behaviour.

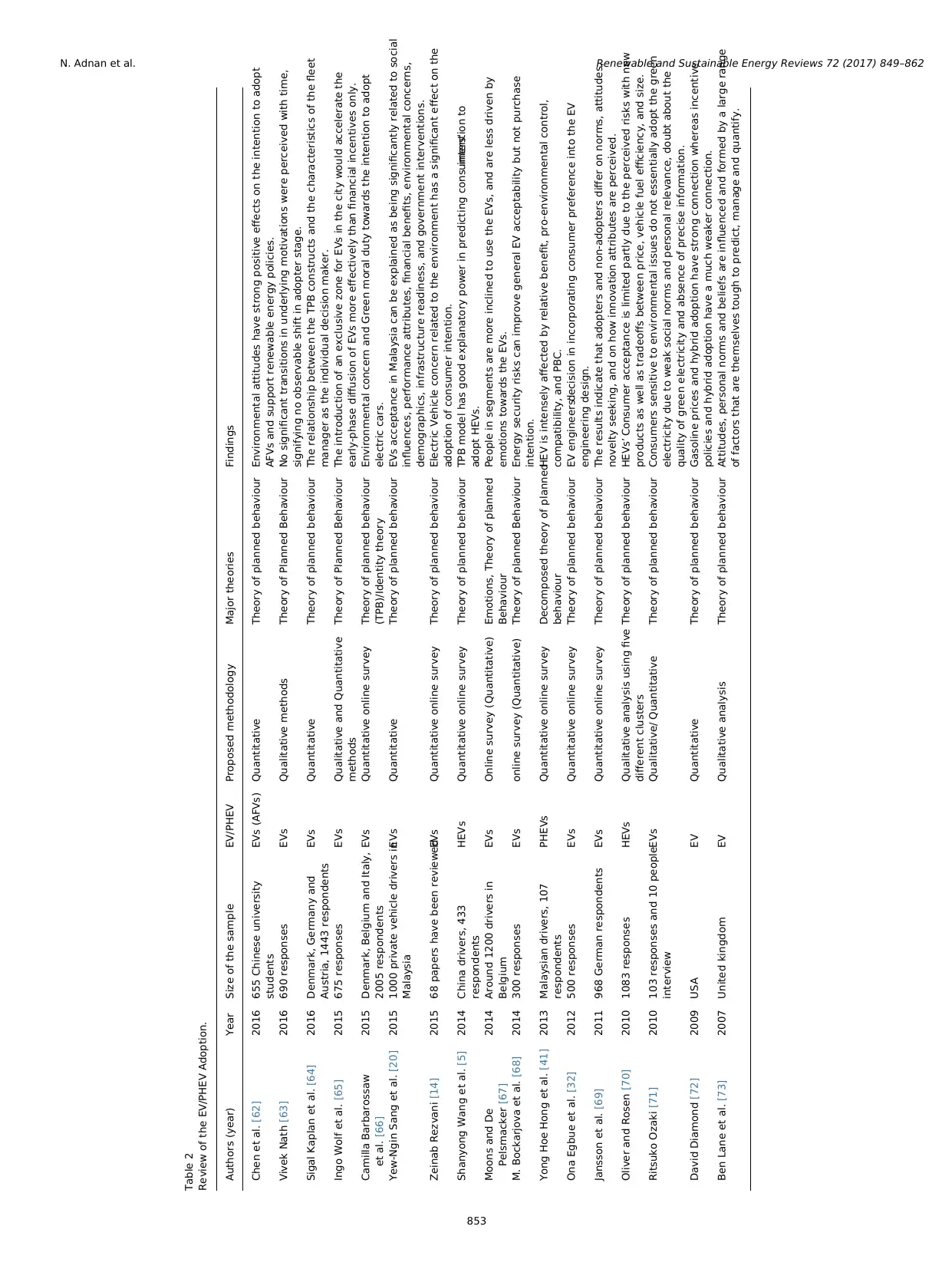

Table 2 illustrates the review of the EV/PHEV Adoption. As an

example, Afroz et al. [57] observed that the environmentalists usually

buy more EVs/PHEVs than the non-environmentalists.Fedor et al.

[58] observed that the concern regarding the environment is the most

significant and dominant factor towards the purchase of EVs/PHEVs.

The consumers,who are highly concerned with the environment,will

be more willing to buy EVs/PHEVs. Ziegler [59] showed in his research

that a buyer, who shows concern towards the environment,bears

greater preferencefor environment-friendly(or green) vehicles.

Moreover,Bateman et al.[7] utilised the defined data structure and

statistics on both the decision for buying a vehicle and consumer

concernstowards the environmentto study consumer preferences

towards green technologies,and concluded thatthe consumerwill

pay more for low emission vehicles as they are highly concerned with

the environment.Bamberg [60]defined the role of environmental

concern,and mentioned it as an important component of the model

named the extended TPB.The research study of [61] showed that by

performing an all-inclusive study and to comprehend the consumers’

intention towards the adoption of PHEV/EVs, individual environmen-

tal concern and ethical norm were included into the model of the TPB

in order to change it into a model named the ‘extended TPB’.Hence,

our research study recognises the suitability of this modelas well as

confirms the explanatorypower of the extended TPB model in

predicting consumers’intention, better, towards the adoption of EVs/

PHEVs.

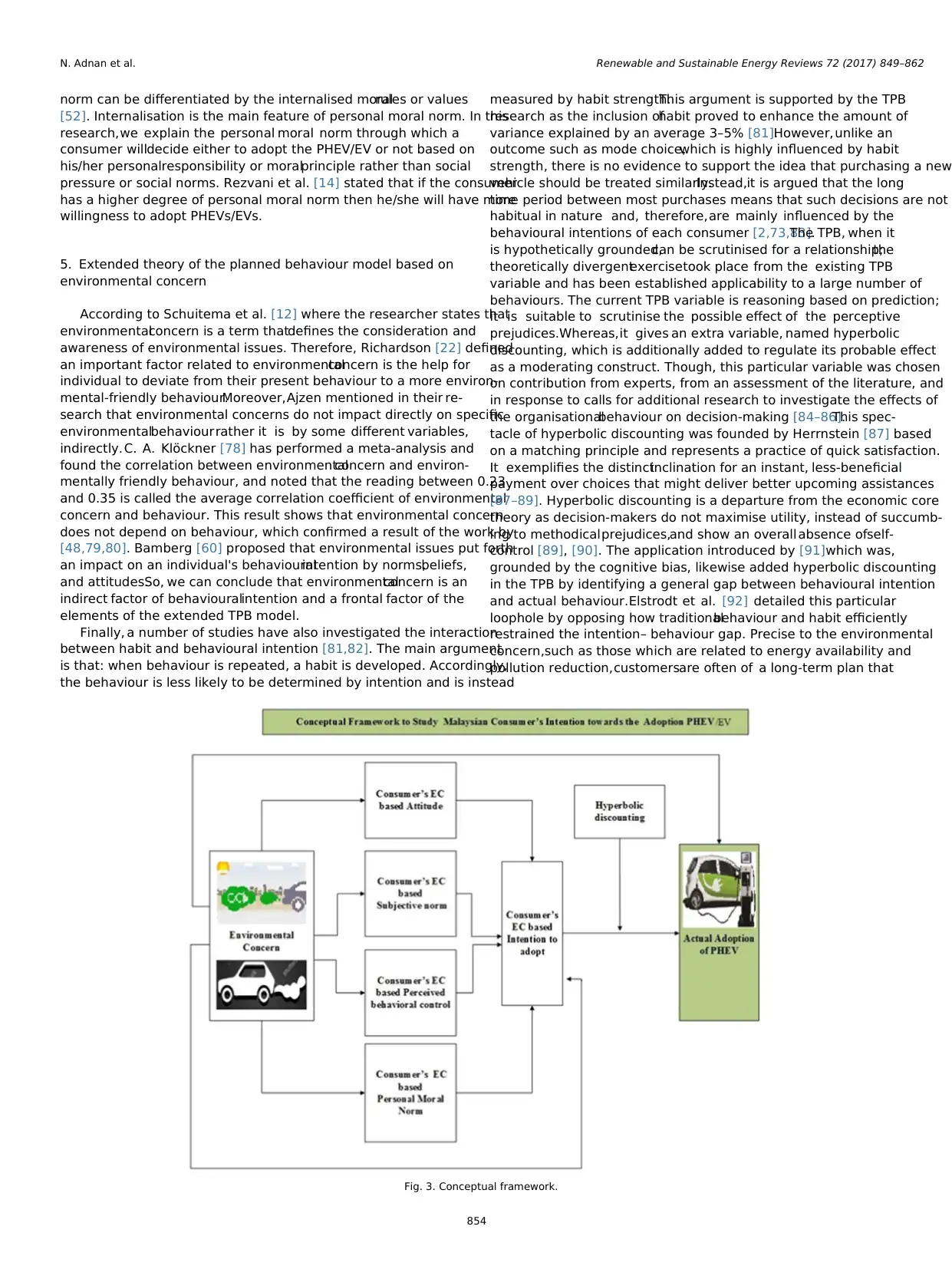

4. Conceptual framework and hypothetical relationship

According to Davis’observation in the modelof the TPB, actual

behaviour as wellas behaviouralintention (BI) have similar factors,

although BI is usually more powerfully forecasted compared to the

actual behaviour.Moreover,in the year 1991,Ajzen observed BI as a

direct determining factor ofactual behaviour,and when a suitable

measure ofintention is attained,this will result the most accurate

prediction of behaviour. This indicates that intention towards adoption

may be more strongly connected to the determinants than the actual

adoption. In 2013, Schuitema et al. also defined that the measurement

of the level of the actual adoption is slightly difficult to achieve. In the

meanwhile, PHEVs/EVs are in the beginning mode in Malaysia and a

large number ofconsumers are making the decision on whether to

adopt PHEVs/EVs. Thus, this paper has covered that measuring the

adoption intention is more applicable than the actualadoption.Han

and Kim [74] noted that in regards to the elements presentin the

extended theory of planned behaviour in the TPB, attitude directs the

complete evaluation ofthe specific behaviour in the perspective of

consumer intention towards the adoption of PHEVs/EVs; and, attitude

is the term that is defined as the positive or negative assessment of the

adoption behaviour.Heath et al.[75] observed that in many studies,

attitude is an important variable (anterior) ofbehaviouralintention.

For example,Klöckner et al.[76] surveyed on a national base to find

out the consumer intention towards the purchase of green vehicles, and

he found that consumers having a positive attitude towards environ-

mentalconcerns are more willing to adoptgreen vehicles.In 1991,

Ajzen stated that the consumers who have a more positive attitude,

their intention will be stronger to perform a certain behaviour.He

further defined that the subjective norms of an individual are received

from the social pressure from groups of people or other people that are

important in his/her life and wish him/her to act in a specific manner.

Additionally, Bockarjova and Steg [68],and Chen and Tung [53]

observed thatit is proved in past researches thatsubjective norms

affect behavioural intention in positive manner. However, they further

elaborate thatfor people considering thatthey should perform a

specific behaviour,they will have more intention to perform due to a

higher degree ofsocial pressure [53,68].In the TPB, the Perceived

behaviouralcontrol is the last predictor ofintention [48].Whereas,

Ajzen also defined the perceived behaviouralcontrol (PBC) as the

degree of ease and difficulty perceived by an individual with respect to

conducting a certain behaviour.In the recent scenario,the perceived

behaviouralcontrol consists of the perception oftechnology,price,

availability or knowledge to use the PHEV, and the capability to

perform the adoption behaviour.López-Mosquera and Sánchez [77]

stated that the more a consumer as the ability to control these

elements, the more behavioural intention will be developed.

However, Ajzen defined that the personal moral norm, i.e., an extended

elementdefined in the TPB, indicates thatpeople sense a need for

performing a specific moralbehaviourand makes his/her findings

depend on his/her responsibility or principle. There is very much

difference between personal moral norm and subjective norm.

Subjective norms cover external social pressure whilst personal moral

Fig. 2. Total electrified vehicle sales by country, Asia Pacific: 2010–2015.

Source: Pike Research.

Table 1

Total vehicle Sales in Malaysia from the Years 2008–2016.

Source: Malaysian Automotive Association (2016)

Year Passenger cars

(units)

Commercial vehicles

(units)

Total sales

(units)

2008 497,459 50,656 548,915

2009 486,342 50,563 536,905

2010 543,594 61,562 603,156

2011 535,113 65,010 600,123

2012 552,189 75,564 627,753

2013 576,657 79,136 655,793

2014 588,341 78,124 666,465

2015 591,298 75,376 666,674

JUNE

2016

244,357 31,102 275,459

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

852

friendly manner and noted that one's moral norms are a possible way

to find the behavioural intention. Kroshus et al. [55] stated that

German buyers are aware of climate change and they want to adopt

green vehicles by paying a significant amount and fulfilltheir moral

norms and responsibilities.By these researches,we can come to a

conclusion that the variable of personal moral norms plays a significant

role on behavioural intention. The TPB, which previously had 3

primary elements,namely attitude,subjective norms,and perceived

behaviour,may be converted into an extended TPB modelby adding

personalnorms in the TPB model [53]. Jalilvand and Samiei [56]

mentioned that consumers are now more concerned about the envir-

onmentfrom the last decades due to the dreadfulcondition of the

environment.Many researchers have defined the link between green

concerns and definite eco-friendly behaviour,and have worried about

the environmentalconcerns in predicting thatparticular behaviour.

Table 2 illustrates the review of the EV/PHEV Adoption. As an

example, Afroz et al. [57] observed that the environmentalists usually

buy more EVs/PHEVs than the non-environmentalists.Fedor et al.

[58] observed that the concern regarding the environment is the most

significant and dominant factor towards the purchase of EVs/PHEVs.

The consumers,who are highly concerned with the environment,will

be more willing to buy EVs/PHEVs. Ziegler [59] showed in his research

that a buyer, who shows concern towards the environment,bears

greater preferencefor environment-friendly(or green) vehicles.

Moreover,Bateman et al.[7] utilised the defined data structure and

statistics on both the decision for buying a vehicle and consumer

concernstowards the environmentto study consumer preferences

towards green technologies,and concluded thatthe consumerwill

pay more for low emission vehicles as they are highly concerned with

the environment.Bamberg [60]defined the role of environmental

concern,and mentioned it as an important component of the model

named the extended TPB.The research study of [61] showed that by

performing an all-inclusive study and to comprehend the consumers’

intention towards the adoption of PHEV/EVs, individual environmen-

tal concern and ethical norm were included into the model of the TPB

in order to change it into a model named the ‘extended TPB’.Hence,

our research study recognises the suitability of this modelas well as

confirms the explanatorypower of the extended TPB model in

predicting consumers’intention, better, towards the adoption of EVs/

PHEVs.

4. Conceptual framework and hypothetical relationship

According to Davis’observation in the modelof the TPB, actual

behaviour as wellas behaviouralintention (BI) have similar factors,

although BI is usually more powerfully forecasted compared to the

actual behaviour.Moreover,in the year 1991,Ajzen observed BI as a

direct determining factor ofactual behaviour,and when a suitable

measure ofintention is attained,this will result the most accurate

prediction of behaviour. This indicates that intention towards adoption

may be more strongly connected to the determinants than the actual

adoption. In 2013, Schuitema et al. also defined that the measurement

of the level of the actual adoption is slightly difficult to achieve. In the

meanwhile, PHEVs/EVs are in the beginning mode in Malaysia and a

large number ofconsumers are making the decision on whether to

adopt PHEVs/EVs. Thus, this paper has covered that measuring the

adoption intention is more applicable than the actualadoption.Han

and Kim [74] noted that in regards to the elements presentin the

extended theory of planned behaviour in the TPB, attitude directs the

complete evaluation ofthe specific behaviour in the perspective of

consumer intention towards the adoption of PHEVs/EVs; and, attitude

is the term that is defined as the positive or negative assessment of the

adoption behaviour.Heath et al.[75] observed that in many studies,

attitude is an important variable (anterior) ofbehaviouralintention.

For example,Klöckner et al.[76] surveyed on a national base to find

out the consumer intention towards the purchase of green vehicles, and

he found that consumers having a positive attitude towards environ-

mentalconcerns are more willing to adoptgreen vehicles.In 1991,

Ajzen stated that the consumers who have a more positive attitude,

their intention will be stronger to perform a certain behaviour.He

further defined that the subjective norms of an individual are received

from the social pressure from groups of people or other people that are

important in his/her life and wish him/her to act in a specific manner.

Additionally, Bockarjova and Steg [68],and Chen and Tung [53]

observed thatit is proved in past researches thatsubjective norms

affect behavioural intention in positive manner. However, they further

elaborate thatfor people considering thatthey should perform a

specific behaviour,they will have more intention to perform due to a

higher degree ofsocial pressure [53,68].In the TPB, the Perceived

behaviouralcontrol is the last predictor ofintention [48].Whereas,

Ajzen also defined the perceived behaviouralcontrol (PBC) as the

degree of ease and difficulty perceived by an individual with respect to

conducting a certain behaviour.In the recent scenario,the perceived

behaviouralcontrol consists of the perception oftechnology,price,

availability or knowledge to use the PHEV, and the capability to

perform the adoption behaviour.López-Mosquera and Sánchez [77]

stated that the more a consumer as the ability to control these

elements, the more behavioural intention will be developed.

However, Ajzen defined that the personal moral norm, i.e., an extended

elementdefined in the TPB, indicates thatpeople sense a need for

performing a specific moralbehaviourand makes his/her findings

depend on his/her responsibility or principle. There is very much

difference between personal moral norm and subjective norm.

Subjective norms cover external social pressure whilst personal moral

Fig. 2. Total electrified vehicle sales by country, Asia Pacific: 2010–2015.

Source: Pike Research.

Table 1

Total vehicle Sales in Malaysia from the Years 2008–2016.

Source: Malaysian Automotive Association (2016)

Year Passenger cars

(units)

Commercial vehicles

(units)

Total sales

(units)

2008 497,459 50,656 548,915

2009 486,342 50,563 536,905

2010 543,594 61,562 603,156

2011 535,113 65,010 600,123

2012 552,189 75,564 627,753

2013 576,657 79,136 655,793

2014 588,341 78,124 666,465

2015 591,298 75,376 666,674

JUNE

2016

244,357 31,102 275,459

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

852

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 2

Review of the EV/PHEV Adoption.

Authors (year) Year Size of the sample EV/PHEV Proposed methodology Major theories Findings

Chen et al. [62] 2016 655 Chinese university

students

EVs (AFVs) Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour Environmental attitudes have strong positive effects on the intention to adopt

AFVs and support renewable energy policies.

Vivek Nath [63] 2016 690 responses EVs Qualitative methods Theory of Planned Behaviour No significant transitions in underlying motivations were perceived with time,

signifying no observable shift in adopter stage.

Sigal Kaplan et al. [64] 2016 Denmark, Germany and

Austria, 1443 respondents

EVs Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour The relationship between the TPB constructs and the characteristics of the fleet

manager as the individual decision maker.

Ingo Wolf et al. [65] 2015 675 responses EVs Qualitative and Quantitative

methods

Theory of Planned Behaviour The introduction of an exclusive zone for EVs in the city would accelerate the

early-phase diffusion of EVs more effectively than financial incentives only.

Camilla Barbarossaw

et al. [66]

2015 Denmark, Belgium and Italy,

2005 respondents

EVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour

(TPB)/Identity theory

Environmental concern and Green moral duty towards the intention to adopt

electric cars.

Yew-Ngin Sang et al. [20] 2015 1000 private vehicle drivers in

Malaysia

EVs Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour EVs acceptance in Malaysia can be explained as being significantly related to social

influences, performance attributes, financial benefits, environmental concerns,

demographics, infrastructure readiness, and government interventions.

Zeinab Rezvani [14] 2015 68 papers have been reviewedEVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour Electric Vehicle concern related to the environment has a significant effect on the

adoption of consumer intention.

Shanyong Wang et al. [5] 2014 China drivers, 433

respondents

HEVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour TPB model has good explanatory power in predicting consumers’intention to

adopt HEVs.

Moons and De

Pelsmacker [67]

2014 Around 1200 drivers in

Belgium

EVs Online survey (Quantitative) Emotions, Theory of planned

Behaviour

People in segments are more inclined to use the EVs, and are less driven by

emotions towards the EVs.

M. Bockarjova et al. [68] 2014 300 responses EVs online survey (Quantitative) Theory of planned Behaviour Energy security risks can improve general EV acceptability but not purchase

intention.

Yong Hoe Hong et al. [41] 2013 Malaysian drivers, 107

respondents

PHEVs Quantitative online survey Decomposed theory of planned

behaviour

HEV is intensely affected by relative benefit, pro-environmental control,

compatibility, and PBC.

Ona Egbue et al. [32] 2012 500 responses EVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour EV engineers'decision in incorporating consumer preference into the EV

engineering design.

Jansson et al. [69] 2011 968 German respondents EVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour The results indicate that adopters and non-adopters differ on norms, attitudes,

novelty seeking, and on how innovation attributes are perceived.

Oliver and Rosen [70] 2010 1083 responses HEVs Qualitative analysis using five

different clusters

Theory of planned behaviour HEVs’ Consumer acceptance is limited partly due to the perceived risks with new

products as well as tradeoffs between price, vehicle fuel efficiency, and size.

Ritsuko Ozaki [71] 2010 103 responses and 10 people

interview

EVs Qualitative/ Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour Consumers sensitive to environmental issues do not essentially adopt the green

electricity due to weak social norms and personal relevance, doubt about the

quality of green electricity and absence of precise information.

David Diamond [72] 2009 USA EV Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour Gasoline prices and hybrid adoption have strong connection whereas incentive

policies and hybrid adoption have a much weaker connection.

Ben Lane et al. [73] 2007 United kingdom EV Qualitative analysis Theory of planned behaviour Attitudes, personal norms and beliefs are influenced and formed by a large range

of factors that are themselves tough to predict, manage and quantify.

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

853

Review of the EV/PHEV Adoption.

Authors (year) Year Size of the sample EV/PHEV Proposed methodology Major theories Findings

Chen et al. [62] 2016 655 Chinese university

students

EVs (AFVs) Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour Environmental attitudes have strong positive effects on the intention to adopt

AFVs and support renewable energy policies.

Vivek Nath [63] 2016 690 responses EVs Qualitative methods Theory of Planned Behaviour No significant transitions in underlying motivations were perceived with time,

signifying no observable shift in adopter stage.

Sigal Kaplan et al. [64] 2016 Denmark, Germany and

Austria, 1443 respondents

EVs Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour The relationship between the TPB constructs and the characteristics of the fleet

manager as the individual decision maker.

Ingo Wolf et al. [65] 2015 675 responses EVs Qualitative and Quantitative

methods

Theory of Planned Behaviour The introduction of an exclusive zone for EVs in the city would accelerate the

early-phase diffusion of EVs more effectively than financial incentives only.

Camilla Barbarossaw

et al. [66]

2015 Denmark, Belgium and Italy,

2005 respondents

EVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour

(TPB)/Identity theory

Environmental concern and Green moral duty towards the intention to adopt

electric cars.

Yew-Ngin Sang et al. [20] 2015 1000 private vehicle drivers in

Malaysia

EVs Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour EVs acceptance in Malaysia can be explained as being significantly related to social

influences, performance attributes, financial benefits, environmental concerns,

demographics, infrastructure readiness, and government interventions.

Zeinab Rezvani [14] 2015 68 papers have been reviewedEVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour Electric Vehicle concern related to the environment has a significant effect on the

adoption of consumer intention.

Shanyong Wang et al. [5] 2014 China drivers, 433

respondents

HEVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour TPB model has good explanatory power in predicting consumers’intention to

adopt HEVs.

Moons and De

Pelsmacker [67]

2014 Around 1200 drivers in

Belgium

EVs Online survey (Quantitative) Emotions, Theory of planned

Behaviour

People in segments are more inclined to use the EVs, and are less driven by

emotions towards the EVs.

M. Bockarjova et al. [68] 2014 300 responses EVs online survey (Quantitative) Theory of planned Behaviour Energy security risks can improve general EV acceptability but not purchase

intention.

Yong Hoe Hong et al. [41] 2013 Malaysian drivers, 107

respondents

PHEVs Quantitative online survey Decomposed theory of planned

behaviour

HEV is intensely affected by relative benefit, pro-environmental control,

compatibility, and PBC.

Ona Egbue et al. [32] 2012 500 responses EVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour EV engineers'decision in incorporating consumer preference into the EV

engineering design.

Jansson et al. [69] 2011 968 German respondents EVs Quantitative online survey Theory of planned behaviour The results indicate that adopters and non-adopters differ on norms, attitudes,

novelty seeking, and on how innovation attributes are perceived.

Oliver and Rosen [70] 2010 1083 responses HEVs Qualitative analysis using five

different clusters

Theory of planned behaviour HEVs’ Consumer acceptance is limited partly due to the perceived risks with new

products as well as tradeoffs between price, vehicle fuel efficiency, and size.

Ritsuko Ozaki [71] 2010 103 responses and 10 people

interview

EVs Qualitative/ Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour Consumers sensitive to environmental issues do not essentially adopt the green

electricity due to weak social norms and personal relevance, doubt about the

quality of green electricity and absence of precise information.

David Diamond [72] 2009 USA EV Quantitative Theory of planned behaviour Gasoline prices and hybrid adoption have strong connection whereas incentive

policies and hybrid adoption have a much weaker connection.

Ben Lane et al. [73] 2007 United kingdom EV Qualitative analysis Theory of planned behaviour Attitudes, personal norms and beliefs are influenced and formed by a large range

of factors that are themselves tough to predict, manage and quantify.

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

853

norm can be differentiated by the internalised moralrules or values

[52]. Internalisation is the main feature of personal moral norm. In this

research,we explain the personal moral norm through which a

consumer willdecide either to adopt the PHEV/EV or not based on

his/her personalresponsibility or moralprinciple rather than social

pressure or social norms. Rezvani et al. [14] stated that if the consumer

has a higher degree of personal moral norm then he/she will have more

willingness to adopt PHEVs/EVs.

5. Extended theory of the planned behaviour model based on

environmental concern

According to Schuitema et al. [12] where the researcher states that

environmentalconcern is a term thatdefines the consideration and

awareness of environmental issues. Therefore, Richardson [22] defined

an important factor related to environmentalconcern is the help for

individual to deviate from their present behaviour to a more environ-

mental-friendly behaviour.Moreover,Ajzen mentioned in their re-

search that environmental concerns do not impact directly on specific

environmentalbehaviourrather it is by some different variables,

indirectly.C. A. Klöckner [78] has performed a meta-analysis and

found the correlation between environmentalconcern and environ-

mentally friendly behaviour, and noted that the reading between 0.23

and 0.35 is called the average correlation coefficient of environmental

concern and behaviour. This result shows that environmental concern

does not depend on behaviour, which confirmed a result of the work by

[48,79,80]. Bamberg [60] proposed that environmental issues put forth

an impact on an individual's behaviouralintention by norms,beliefs,

and attitudes.So, we can conclude that environmentalconcern is an

indirect factor of behaviouralintention and a frontal factor of the

elements of the extended TPB model.

Finally, a number of studies have also investigated the interaction

between habit and behavioural intention [81,82]. The main argument

is that: when behaviour is repeated, a habit is developed. Accordingly,

the behaviour is less likely to be determined by intention and is instead

measured by habit strength.This argument is supported by the TPB

research as the inclusion ofhabit proved to enhance the amount of

variance explained by an average 3–5% [81].However,unlike an

outcome such as mode choice,which is highly influenced by habit

strength, there is no evidence to support the idea that purchasing a new

vehicle should be treated similarly.Instead,it is argued that the long

time period between most purchases means that such decisions are not

habitual in nature and, therefore,are mainly influenced by the

behavioural intentions of each consumer [2,73,83].The TPB, when it

is hypothetically grounded,can be scrutinised for a relationship;the

theoretically divergentexercisetook place from the existing TPB

variable and has been established applicability to a large number of

behaviours. The current TPB variable is reasoning based on prediction;

it is suitable to scrutinise the possible effect of the perceptive

prejudices.Whereas,it gives an extra variable, named hyperbolic

discounting, which is additionally added to regulate its probable effect

as a moderating construct. Though, this particular variable was chosen

on contribution from experts, from an assessment of the literature, and

in response to calls for additional research to investigate the effects of

the organisationalbehaviour on decision-making [84–86].This spec-

tacle of hyperbolic discounting was founded by Herrnstein [87] based

on a matching principle and represents a practice of quick satisfaction.

It exemplifies the distinctinclination for an instant, less-beneficial

payment over choices that might deliver better upcoming assistances

[87–89]. Hyperbolic discounting is a departure from the economic core

theory as decision-makers do not maximise utility, instead of succumb-

ing to methodicalprejudices,and show an overall absence ofself-

control [89], [90]. The application introduced by [91]which was,

grounded by the cognitive bias, likewise added hyperbolic discounting

in the TPB by identifying a general gap between behavioural intention

and actual behaviour.Elstrodt et al. [92] detailed this particular

loophole by opposing how traditionalbehaviour and habit efficiently

restrained the intention– behaviour gap. Precise to the environmental

concern,such as those which are related to energy availability and

pollution reduction,customersare often of a long-term plan that

Fig. 3. Conceptual framework.

N. Adnan et al. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72 (2017) 849–862

854

[52]. Internalisation is the main feature of personal moral norm. In this

research,we explain the personal moral norm through which a

consumer willdecide either to adopt the PHEV/EV or not based on

his/her personalresponsibility or moralprinciple rather than social

pressure or social norms. Rezvani et al. [14] stated that if the consumer

has a higher degree of personal moral norm then he/she will have more

willingness to adopt PHEVs/EVs.

5. Extended theory of the planned behaviour model based on

environmental concern

According to Schuitema et al. [12] where the researcher states that

environmentalconcern is a term thatdefines the consideration and

awareness of environmental issues. Therefore, Richardson [22] defined

an important factor related to environmentalconcern is the help for

individual to deviate from their present behaviour to a more environ-

mental-friendly behaviour.Moreover,Ajzen mentioned in their re-

search that environmental concerns do not impact directly on specific

environmentalbehaviourrather it is by some different variables,

indirectly.C. A. Klöckner [78] has performed a meta-analysis and

found the correlation between environmentalconcern and environ-

mentally friendly behaviour, and noted that the reading between 0.23

and 0.35 is called the average correlation coefficient of environmental

concern and behaviour. This result shows that environmental concern

does not depend on behaviour, which confirmed a result of the work by

[48,79,80]. Bamberg [60] proposed that environmental issues put forth

an impact on an individual's behaviouralintention by norms,beliefs,

and attitudes.So, we can conclude that environmentalconcern is an

indirect factor of behaviouralintention and a frontal factor of the

elements of the extended TPB model.

Finally, a number of studies have also investigated the interaction

between habit and behavioural intention [81,82]. The main argument

is that: when behaviour is repeated, a habit is developed. Accordingly,

the behaviour is less likely to be determined by intention and is instead

measured by habit strength.This argument is supported by the TPB

research as the inclusion ofhabit proved to enhance the amount of

variance explained by an average 3–5% [81].However,unlike an

outcome such as mode choice,which is highly influenced by habit

strength, there is no evidence to support the idea that purchasing a new

vehicle should be treated similarly.Instead,it is argued that the long

time period between most purchases means that such decisions are not

habitual in nature and, therefore,are mainly influenced by the

behavioural intentions of each consumer [2,73,83].The TPB, when it

is hypothetically grounded,can be scrutinised for a relationship;the

theoretically divergentexercisetook place from the existing TPB

variable and has been established applicability to a large number of

behaviours. The current TPB variable is reasoning based on prediction;

it is suitable to scrutinise the possible effect of the perceptive

prejudices.Whereas,it gives an extra variable, named hyperbolic

discounting, which is additionally added to regulate its probable effect

as a moderating construct. Though, this particular variable was chosen

on contribution from experts, from an assessment of the literature, and

in response to calls for additional research to investigate the effects of

the organisationalbehaviour on decision-making [84–86].This spec-

tacle of hyperbolic discounting was founded by Herrnstein [87] based

on a matching principle and represents a practice of quick satisfaction.

It exemplifies the distinctinclination for an instant, less-beneficial

payment over choices that might deliver better upcoming assistances

[87–89]. Hyperbolic discounting is a departure from the economic core

theory as decision-makers do not maximise utility, instead of succumb-

ing to methodicalprejudices,and show an overall absence ofself-

control [89], [90]. The application introduced by [91]which was,

grounded by the cognitive bias, likewise added hyperbolic discounting

in the TPB by identifying a general gap between behavioural intention

and actual behaviour.Elstrodt et al. [92] detailed this particular

loophole by opposing how traditionalbehaviour and habit efficiently

restrained the intention– behaviour gap. Precise to the environmental

concern,such as those which are related to energy availability and

pollution reduction,customersare often of a long-term plan that

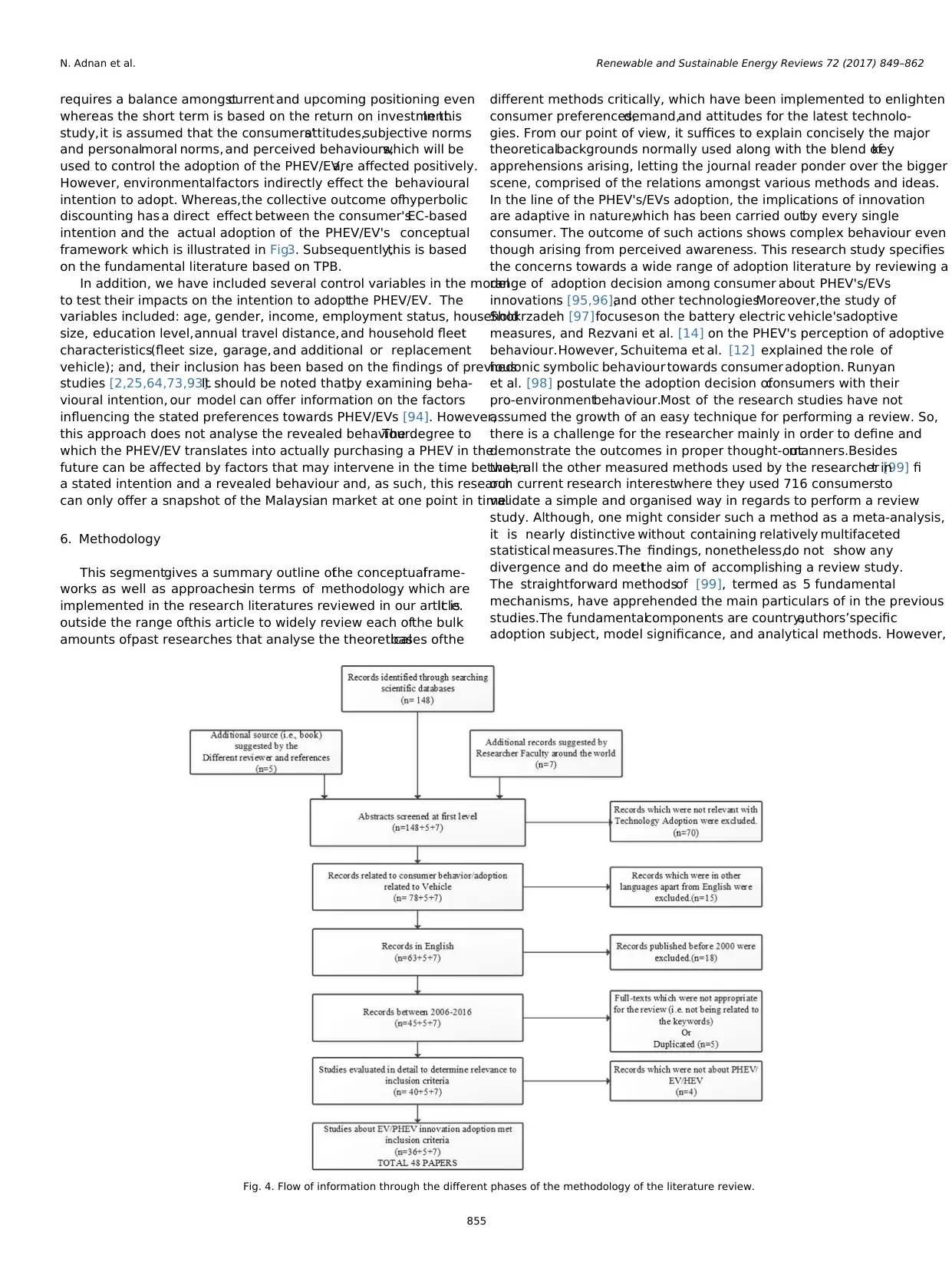

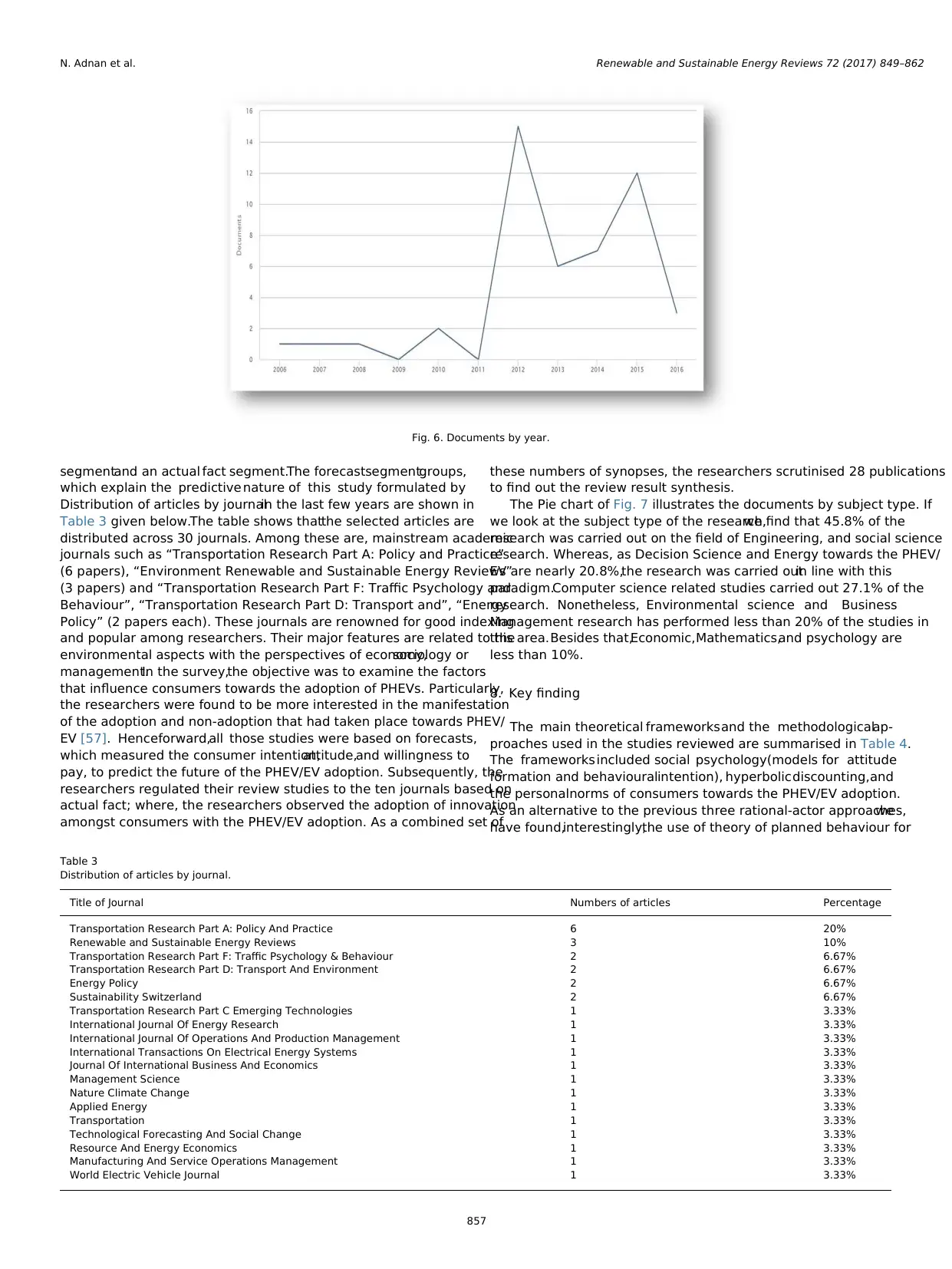

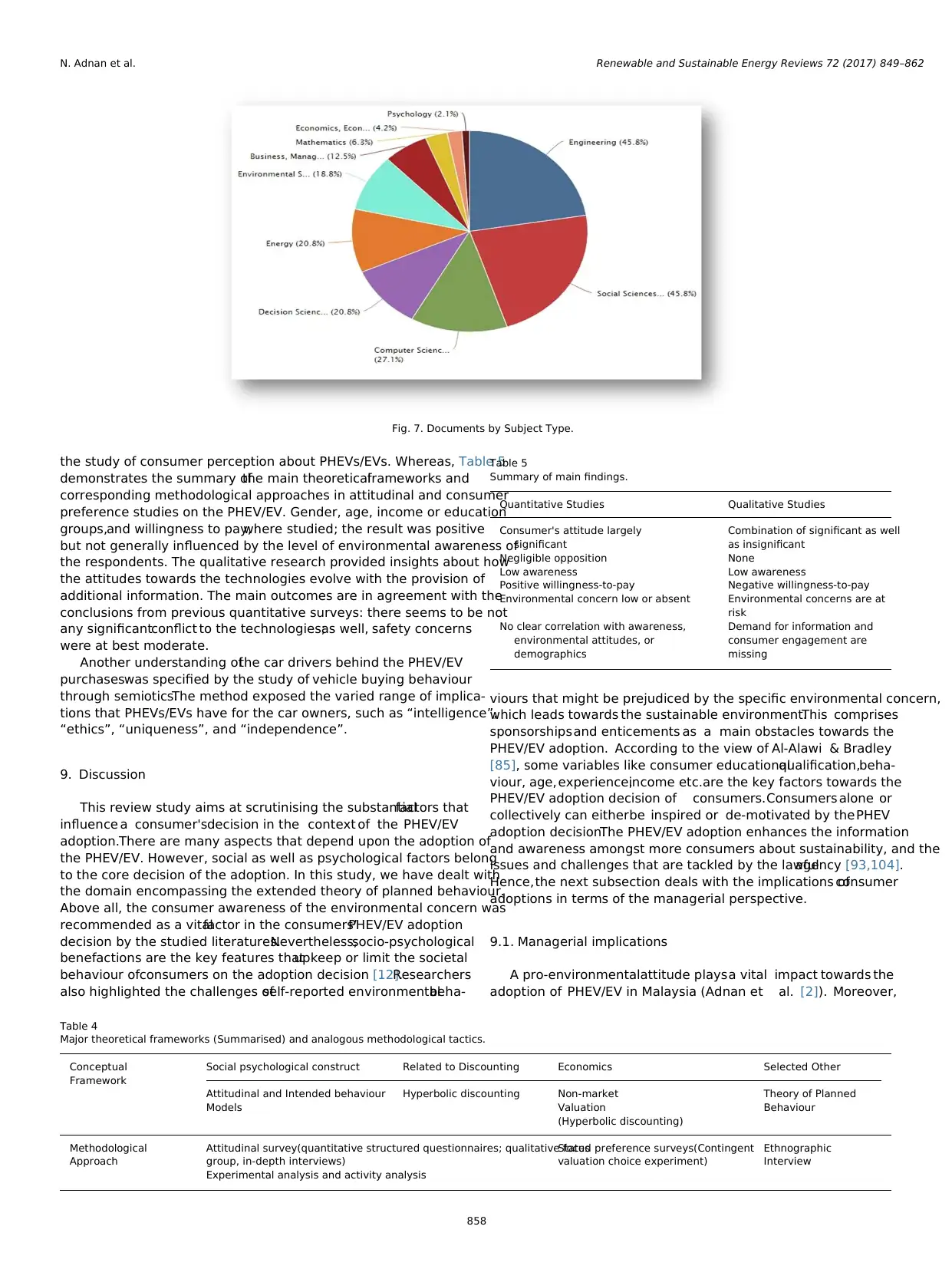

Fig. 3. Conceptual framework.