Cross-Sectional Survey: Vaccine Perception and Leaders' Influence

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|8

|7303

|16

Report

AI Summary

This report presents the findings of a cross-sectional survey conducted in Australia, investigating the influence of political and medical leaders on parental perceptions of vaccination. The study aimed to understand how messages from figures like Donald Trump, Pauline Hanson, and Michael Gannon impact parents' attitudes towards childhood immunizations. Participants were categorized as having 'fixed' or 'susceptible' views on vaccination. The results indicated that susceptible parents, who constituted a majority of the sample, were more likely to report a change in their willingness to vaccinate after viewing vaccine-related messages, regardless of the message's content. Furthermore, susceptible parents showed increased vaccine hesitancy after viewing negative messages. The study highlights the importance of understanding parental susceptibility to vaccine messaging and suggests categorizing parents as 'fixed-view' or 'susceptible' can be a useful strategy for designing and implementing future vaccine promotion interventions.

1Zhang EJ, et al. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866

Open access

Influence of political and medical

leaders on parental perception of

vaccination: a cross-sectional survey

in Australia

Elissa J Zhang,1 Abrar Ahmad Chughtai,1 Anita Heywood,1

Chandini Raina MacIntyre1,2

To cite: Zhang EJ, Chughtai AA,

Heywood A, et al. Influence of

political and medical leaders

on parental perception of

vaccination: a cross-sectional

survey in Australia. BMJ Open

2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/

bmjopen-2018-025866

► Prepublication history and

additional material for this

paper are available online. To

view these files, please visit

the journal online (http:// dx. doi.

org/10. 1136/bmjopen- 2018-

025866).

Received 24 August 2018

Revised 13 January 2019

Accepted 14 February 2019

1School of Public Health and

Community Medicine, UNSW

Medicine, University of New

South Wales, Sydney, New South

Wales, Australia

2Kirby Institute, University of

New South Wales, Sydney, New

South Wales, Australia

Correspondence to

Abrar Ahmad Chughtai;

abrar. chughtai@unsw. edu.au

Research

© Author(s) (or their

employer(s)) 2019. Re-use

permitted under CC BY-NC. No

commercial re-use. See rights

and permissions. Published by

BMJ.

AbstrACt

Objectives The aim of this survey was to investigate

parental vaccination attitudes and responses to vaccine-

related media messages from political and medical

leaders.

Design This was a cross-sectional study using a

semiquantitative questionnaire. Data were analysed using

descriptive statistics, X2 tests and logistic regression.

setting Data were collected from a web-based

questionnaire distributed in Australia by a market research

company in May of 2017.

Participants 411 participants with at least one child

under 5 were included in this study. The sample was

designed to be representative of Australia in terms of

gender and state of residence.

Primary and secondary outcome measures The

primary outcome measures were parental attitudes

towards childhood immunisation before and after viewing

vaccine-related messages from political and medical

leaders, including Donald Trump (USA), Pauline Hanson

(Australia) and Michael Gannon (Australia). Parents were

classified as having ‘susceptible’ (not fixed) or ‘fixed’

(positive or negative) views towards vaccination based on

a series of questions.

results Parents with fixed vaccination views constituted

23.8% (n=98) of the total sample; 21.7% (n=89) were

pro-vaccination and 2.2% (n=9) were anti-vaccination.

The remaining 76.2% of participants were classified as

having susceptible views towards vaccination. Susceptible

parents were more likely to report a change in their

willingness to vaccinate after watching vaccine-related

messages compared with fixed-view parents, regardless

of whether the messaging was positive or negative (Trump

OR 2.54, 95% CI (1.29 to 5.00); Hanson OR 2.64, 95% CI

(1.26 to 5.52); Gannon OR 2.64, 95% CI (1.26 to 5.52)).

Susceptible parents were more likely than fixed-view

parents to report increased vaccine hesitancy after viewing

negative vaccine messages (Trump OR 2.14, 95% CI (1.11

to 4.14), Hanson OR 2.34, 95% CI (1.21 to 4.50)).

Conclusions The findings suggest that most parents

including the vaccinating majorty are susceptible to

vaccine messaging from political and medical leaders.

Categorising parents as ‘fixed-view’ or ‘susceptible’ can

be a useful strategy for designing and implementing future

vaccine promotion interventions.

bACkgrOunD

Vaccines are one of the greatest successes

in public health1 but have been questioned

by prominent antivaccination celebrities in

the media2 3 contributing to vaccine-related

controversy and parental vaccine hesitancy.

The added voice of political leaders in the

media such as US President Donald Trump4

and Australian Senator Pauline Hanson5 may

have additional influence on parents, but

have not been studied.

Public figures ranging from media, sports

and political celebrities have used their

fame to direct media attention towards a

diverse range of health issues including

cancer screening and treatment, HIV disclo-

sure, drug addiction, multiple sclerosis and

Alzheimer’s disease,6–12 reducing stigma

and increasingawareness.Over a quarter

of parents indicated trust in vaccine-related

information from celebrities according to a

US study.13 Most celebrities are not formally

qualified or trained to deliver health commu-

nication and their personal experiences can

be misrepresented when broadcasted on a

population level.12 Some celebritieseven

strengths and limitations of this study

► This study used a novel method of classifying pa

ents as having either ‘fixed’ or ‘susceptible’ view

towards vaccination, rather than ‘acceptance’

‘refusal’.

► The study sample was representative of Aust

in terms of gender, state residence and country

birth.

► Data on participants’ socioeconomic status were

collected and the survey was only administered

English, so there may be some degree of bias.

► Proportion of fixed antivaccine parents was t

small to determine conclusions about the impact

media messages.

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

Open access

Influence of political and medical

leaders on parental perception of

vaccination: a cross-sectional survey

in Australia

Elissa J Zhang,1 Abrar Ahmad Chughtai,1 Anita Heywood,1

Chandini Raina MacIntyre1,2

To cite: Zhang EJ, Chughtai AA,

Heywood A, et al. Influence of

political and medical leaders

on parental perception of

vaccination: a cross-sectional

survey in Australia. BMJ Open

2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/

bmjopen-2018-025866

► Prepublication history and

additional material for this

paper are available online. To

view these files, please visit

the journal online (http:// dx. doi.

org/10. 1136/bmjopen- 2018-

025866).

Received 24 August 2018

Revised 13 January 2019

Accepted 14 February 2019

1School of Public Health and

Community Medicine, UNSW

Medicine, University of New

South Wales, Sydney, New South

Wales, Australia

2Kirby Institute, University of

New South Wales, Sydney, New

South Wales, Australia

Correspondence to

Abrar Ahmad Chughtai;

abrar. chughtai@unsw. edu.au

Research

© Author(s) (or their

employer(s)) 2019. Re-use

permitted under CC BY-NC. No

commercial re-use. See rights

and permissions. Published by

BMJ.

AbstrACt

Objectives The aim of this survey was to investigate

parental vaccination attitudes and responses to vaccine-

related media messages from political and medical

leaders.

Design This was a cross-sectional study using a

semiquantitative questionnaire. Data were analysed using

descriptive statistics, X2 tests and logistic regression.

setting Data were collected from a web-based

questionnaire distributed in Australia by a market research

company in May of 2017.

Participants 411 participants with at least one child

under 5 were included in this study. The sample was

designed to be representative of Australia in terms of

gender and state of residence.

Primary and secondary outcome measures The

primary outcome measures were parental attitudes

towards childhood immunisation before and after viewing

vaccine-related messages from political and medical

leaders, including Donald Trump (USA), Pauline Hanson

(Australia) and Michael Gannon (Australia). Parents were

classified as having ‘susceptible’ (not fixed) or ‘fixed’

(positive or negative) views towards vaccination based on

a series of questions.

results Parents with fixed vaccination views constituted

23.8% (n=98) of the total sample; 21.7% (n=89) were

pro-vaccination and 2.2% (n=9) were anti-vaccination.

The remaining 76.2% of participants were classified as

having susceptible views towards vaccination. Susceptible

parents were more likely to report a change in their

willingness to vaccinate after watching vaccine-related

messages compared with fixed-view parents, regardless

of whether the messaging was positive or negative (Trump

OR 2.54, 95% CI (1.29 to 5.00); Hanson OR 2.64, 95% CI

(1.26 to 5.52); Gannon OR 2.64, 95% CI (1.26 to 5.52)).

Susceptible parents were more likely than fixed-view

parents to report increased vaccine hesitancy after viewing

negative vaccine messages (Trump OR 2.14, 95% CI (1.11

to 4.14), Hanson OR 2.34, 95% CI (1.21 to 4.50)).

Conclusions The findings suggest that most parents

including the vaccinating majorty are susceptible to

vaccine messaging from political and medical leaders.

Categorising parents as ‘fixed-view’ or ‘susceptible’ can

be a useful strategy for designing and implementing future

vaccine promotion interventions.

bACkgrOunD

Vaccines are one of the greatest successes

in public health1 but have been questioned

by prominent antivaccination celebrities in

the media2 3 contributing to vaccine-related

controversy and parental vaccine hesitancy.

The added voice of political leaders in the

media such as US President Donald Trump4

and Australian Senator Pauline Hanson5 may

have additional influence on parents, but

have not been studied.

Public figures ranging from media, sports

and political celebrities have used their

fame to direct media attention towards a

diverse range of health issues including

cancer screening and treatment, HIV disclo-

sure, drug addiction, multiple sclerosis and

Alzheimer’s disease,6–12 reducing stigma

and increasingawareness.Over a quarter

of parents indicated trust in vaccine-related

information from celebrities according to a

US study.13 Most celebrities are not formally

qualified or trained to deliver health commu-

nication and their personal experiences can

be misrepresented when broadcasted on a

population level.12 Some celebritieseven

strengths and limitations of this study

► This study used a novel method of classifying pa

ents as having either ‘fixed’ or ‘susceptible’ view

towards vaccination, rather than ‘acceptance’

‘refusal’.

► The study sample was representative of Aust

in terms of gender, state residence and country

birth.

► Data on participants’ socioeconomic status were

collected and the survey was only administered

English, so there may be some degree of bias.

► Proportion of fixed antivaccine parents was t

small to determine conclusions about the impact

media messages.

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2 Zhang EJ, et al. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-201

Open access

actively condemn childhood vaccination, such as former

model Jenny McCarthy.2 3 Television host Katie Couric,

an established bowel cancer screening spokesperson,11

portrayed doubts14 about the safety of Human Papilloma-

virus Vaccine on her talk show.

As politicians both occupy media attention and have

the authority to direct public health policy on the

issue, their influence is potentially greater than that of

entertainment and sports celebrities. For example, the

mealses, mumps and rubella vaccine-autism controversy

sparked by the discredited Wakefield study15 in 2001 was

influenced when the UK prime minister at the time Tony

Blair refused to disclose the vaccination status of his own

child,16 contributing to parental anxiety and fear, and

impeding the efforts of public health officials.17

US President Trump’s call for a commissioninto

vaccine safety in early 2017 led by vaccine sceptics Robert

Kennedy Jr and Robert De Niro has concerned health

professionals around the world.18 In Australia, Senator

Pauline Hanson created controversyin March 2017

when she advised parents to disregard the advice of their

doctors and ‘do their own research’ into vaccine safety and

promoted a non-existent ‘vaccination reaction test’ which

she subsequently retracted.5 When such views are made

public, they are often countered by medical experts, yet

there is little research on the impact of political messages

and how best to ensure optimal public health messaging.

Parental vaccine hesitancy is well studied, and gener-

ally defined as a delay in acceptance or refusal of vacci-

nation despite availabilityof vaccination services.19

This definition encompasses parents with a spectrum

of vaccine-hesitant opinions, including those with fixed

antivaccinationviews,who generallydo not change

their opinions, and uncertain parents that are not

fully compliant with vaccine schedules but could be

persuaded to change.20 While WHO SAGE definition21

refers to parents who are fully or mostly compliant with

vaccine schedules but experience caution or uncertainty

in doing so, the emphasis of research and health inter-

vention is rather focused on those who refuse some or

all vaccines. These vaccinating parents nevertheless may

be influenced to doubt childhood vaccination and delay

or refuse vaccinations in the future and may still be

susceptible to negative vaccine messages.22 While health

promotion and intervention tend to focus on parents at

the hesitant end of the spectrum, it is currently unknown

how easily influenced the silent majority of vaccinating

parents are, whose continued compliance is necessary

for upholding effective vaccination coverage rates. Hesi-

tant but compliant parents in Australia are influenced by

vaccine-related events and news coverage, contributing

to complex unresolved concerns regarding the safety

of vaccines, and could potentially reduce their future

compliance accordingly.23 The aim of this survey was to

investigate parental vaccination attitudes and responses

to vaccine-related media messages from political and

medical leaders of all types of parents through an alter-

nate model of classifying parental vaccine opinions by

susceptibility to change rather than their behaviour o

vaccine refusal.

MethODs

This study was designed to measure parental attitudes at

baseline and following viewing of vaccine messaging from

public figures through a 15–20 min online questionnaire

of parents of children aged 0–5 years in Australia. Th

questions used in the online survey were formulated by th

authors of this paper to answer the research questions of

this paper and to obtain a range of qualitative and quanti-

tative data on parental attitudes towards childhood vacci-

nations and sociodemographic information. Short video

clips and corresponding transcripts of vaccine messages

from US President Donald Trump, Australian Senator

Pauline Hanson and head of the Australian Medical

Association Michael Gannon were then shown to partic-

ipants and responses collected. The first two message

(Trump, Hanson) questionedvaccinesafety,whereas

the last message (Gannon) affirmed vaccine safety (fo

transcripts, see online supplementary appendix 1). The

impact of these messages on parental willingness to vacc

nate and perception of vaccine safety was compared

against baseline views.

recruitment

A market research company Survey Sampling Interna-

tional was employed to randomly distribute the survey lin

to representative sample (see table 1) aged 18–60 years

stratified by gender and state/territory of residence from

a database of registered panel members (n=400 000)

Distribution of points redeemable for gift cards, cash out

or charity donation provided incentive.

A total of 1727 potential participants clicked on the

survey link. A total of 1316 of these participants had no

children or only had children over 5 years of age an

were ineligible; 411 parents comprised the final eligible

sample.

sample size calculation

The study was powered for a separate study, assessi

acceptanceof a new vaccine policy. Assuming50%

support for vaccination, 385 participants were required,

with alpha=0.05 and power of 80%. The study aimed to

recruit 400 participants, with sampling designed to be

proportionate to the population of states and territories

in Australia.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted on the responses from

the population survey. Influences on parental vaccina-

tion attitudes (eg, doctors, health professionals, personal

experiences,familial/friend advice, media/internet)

were determined prior to exposure to political media

messages (see online supplementary appendix 2). X2

test and OR were used to evaluate the change in parental

views following exposure to vaccine messages from t

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

Open access

actively condemn childhood vaccination, such as former

model Jenny McCarthy.2 3 Television host Katie Couric,

an established bowel cancer screening spokesperson,11

portrayed doubts14 about the safety of Human Papilloma-

virus Vaccine on her talk show.

As politicians both occupy media attention and have

the authority to direct public health policy on the

issue, their influence is potentially greater than that of

entertainment and sports celebrities. For example, the

mealses, mumps and rubella vaccine-autism controversy

sparked by the discredited Wakefield study15 in 2001 was

influenced when the UK prime minister at the time Tony

Blair refused to disclose the vaccination status of his own

child,16 contributing to parental anxiety and fear, and

impeding the efforts of public health officials.17

US President Trump’s call for a commissioninto

vaccine safety in early 2017 led by vaccine sceptics Robert

Kennedy Jr and Robert De Niro has concerned health

professionals around the world.18 In Australia, Senator

Pauline Hanson created controversyin March 2017

when she advised parents to disregard the advice of their

doctors and ‘do their own research’ into vaccine safety and

promoted a non-existent ‘vaccination reaction test’ which

she subsequently retracted.5 When such views are made

public, they are often countered by medical experts, yet

there is little research on the impact of political messages

and how best to ensure optimal public health messaging.

Parental vaccine hesitancy is well studied, and gener-

ally defined as a delay in acceptance or refusal of vacci-

nation despite availabilityof vaccination services.19

This definition encompasses parents with a spectrum

of vaccine-hesitant opinions, including those with fixed

antivaccinationviews,who generallydo not change

their opinions, and uncertain parents that are not

fully compliant with vaccine schedules but could be

persuaded to change.20 While WHO SAGE definition21

refers to parents who are fully or mostly compliant with

vaccine schedules but experience caution or uncertainty

in doing so, the emphasis of research and health inter-

vention is rather focused on those who refuse some or

all vaccines. These vaccinating parents nevertheless may

be influenced to doubt childhood vaccination and delay

or refuse vaccinations in the future and may still be

susceptible to negative vaccine messages.22 While health

promotion and intervention tend to focus on parents at

the hesitant end of the spectrum, it is currently unknown

how easily influenced the silent majority of vaccinating

parents are, whose continued compliance is necessary

for upholding effective vaccination coverage rates. Hesi-

tant but compliant parents in Australia are influenced by

vaccine-related events and news coverage, contributing

to complex unresolved concerns regarding the safety

of vaccines, and could potentially reduce their future

compliance accordingly.23 The aim of this survey was to

investigate parental vaccination attitudes and responses

to vaccine-related media messages from political and

medical leaders of all types of parents through an alter-

nate model of classifying parental vaccine opinions by

susceptibility to change rather than their behaviour o

vaccine refusal.

MethODs

This study was designed to measure parental attitudes at

baseline and following viewing of vaccine messaging from

public figures through a 15–20 min online questionnaire

of parents of children aged 0–5 years in Australia. Th

questions used in the online survey were formulated by th

authors of this paper to answer the research questions of

this paper and to obtain a range of qualitative and quanti-

tative data on parental attitudes towards childhood vacci-

nations and sociodemographic information. Short video

clips and corresponding transcripts of vaccine messages

from US President Donald Trump, Australian Senator

Pauline Hanson and head of the Australian Medical

Association Michael Gannon were then shown to partic-

ipants and responses collected. The first two message

(Trump, Hanson) questionedvaccinesafety,whereas

the last message (Gannon) affirmed vaccine safety (fo

transcripts, see online supplementary appendix 1). The

impact of these messages on parental willingness to vacc

nate and perception of vaccine safety was compared

against baseline views.

recruitment

A market research company Survey Sampling Interna-

tional was employed to randomly distribute the survey lin

to representative sample (see table 1) aged 18–60 years

stratified by gender and state/territory of residence from

a database of registered panel members (n=400 000)

Distribution of points redeemable for gift cards, cash out

or charity donation provided incentive.

A total of 1727 potential participants clicked on the

survey link. A total of 1316 of these participants had no

children or only had children over 5 years of age an

were ineligible; 411 parents comprised the final eligible

sample.

sample size calculation

The study was powered for a separate study, assessi

acceptanceof a new vaccine policy. Assuming50%

support for vaccination, 385 participants were required,

with alpha=0.05 and power of 80%. The study aimed to

recruit 400 participants, with sampling designed to be

proportionate to the population of states and territories

in Australia.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted on the responses from

the population survey. Influences on parental vaccina-

tion attitudes (eg, doctors, health professionals, personal

experiences,familial/friend advice, media/internet)

were determined prior to exposure to political media

messages (see online supplementary appendix 2). X2

test and OR were used to evaluate the change in parental

views following exposure to vaccine messages from t

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

3Zhang EJ, et al. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866

Open access

selected three public figures. All analyses were performed

with IBM SPSS Statistics V.24.0.24

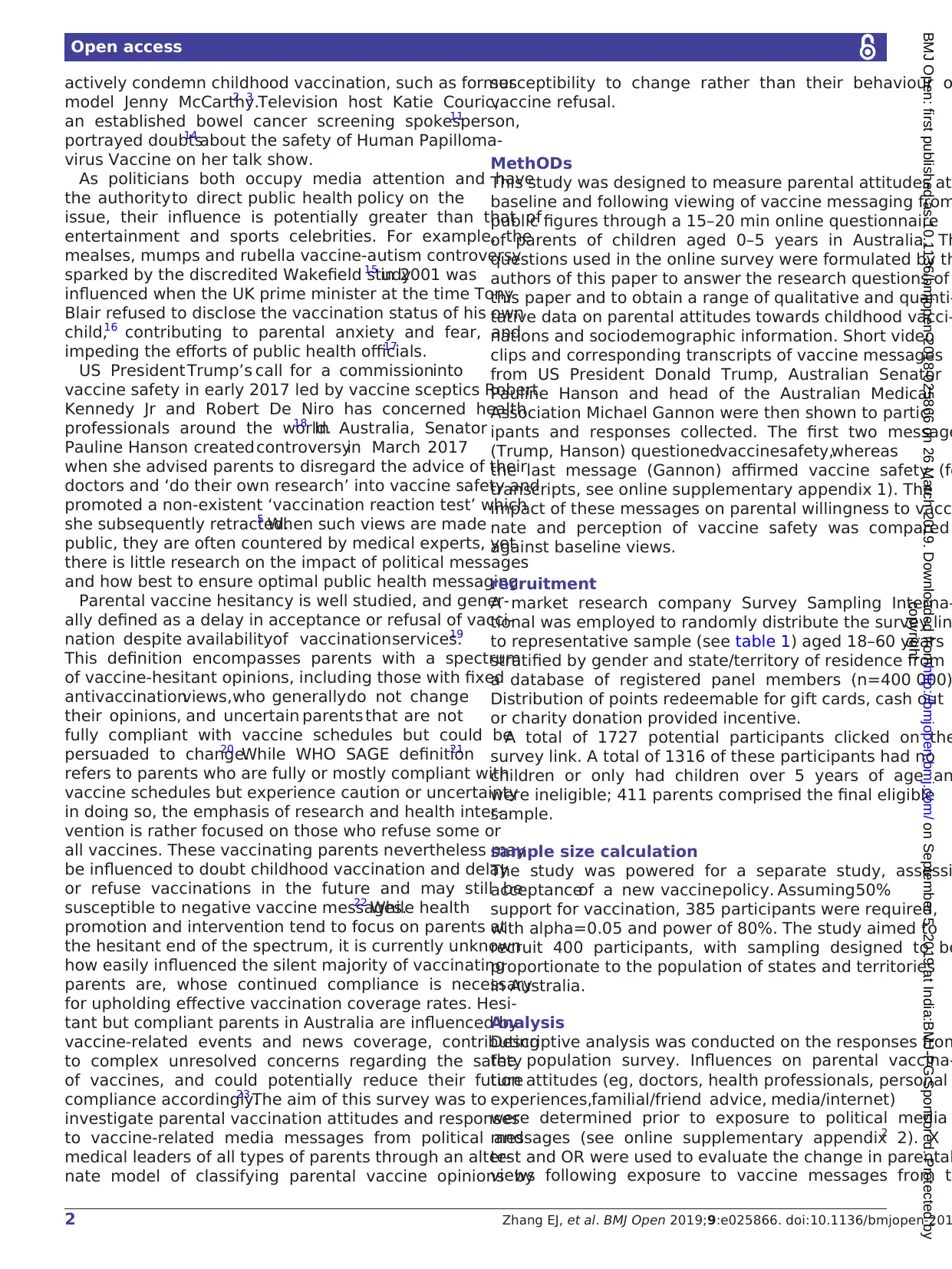

Parents were then categorised according to the fixed-

ness of their baseline vaccination views either for or

against into ‘fixed-view’ and ‘susceptible’ groups, the

rationale being that vaccine attitudes lie on a spectrum25

between complete baseline vaccine rejection and vaccine

acceptance, which we defined as fixed anti-vaccination

and pro-vaccination views (see figure 1). We defined

‘susceptible parents’ by excluding those who expresse

fixed vaccination views in the baseline questions,

including parents who expressed hesitancy or concern

towards vaccines. The remaining parents who did not

have firmly fixed views, even if they were fully vaccinating

we defined as ‘susceptible’. Parents were categorised a

fixed pro-vaccine or anti-vaccine based on their views of

childhood vaccination as ‘very important for children’ or

‘not important for children/risky for children’, respec-

tively, and these views not changing during the surve

The data from the quantitative survey were then inte

nally validated by checking against qualitative comments

in particular, the use of strong language like ‘never’ or

‘always’, and ensuring these were consistent with the cate

gorisation of fixed or susceptible by the agreement two

study authors (EJZ and AAC).

The influence of messaging from the selected public

figures on susceptibleparents was determined by

comparing their views at baseline with views after being

exposed to the messaging. The analysis first noted positiv

and negative change in willingness to vaccinate. Subs

quently, change in either direction was combined into

one single variable ‘change’ and unchanged positive or

negative pre-existing attitudes into a ‘no change’ variable

for further analysis. Closed-ended questions were asked

if the media messages presented in this survey increased

vaccine safety concerns, with optional open-ended elabo-

ration. The difference in response between the subgroups

was evaluated using p values from bivariate X2 analysis and

OR. Qualitative analysis was also performed by manually

collating optional open-ended responses regarding the

persuasiveness of the public figures.

Participant involvement

Parents were not involved in the design of this study.

results

Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics o

the participants, compared against data from the Austra-

lian Bureau of Statistics.26 27The majority of participants

were aged 25–44 years old (n=314, 76.4%).

The percentage of parents born overseas (n=89, 21.7%)

in the sample is slightly less than the population propor-

tion of 28.5%. The majority of surveyed parents (n=327,

79.6%) had completed some form of tertiary education.

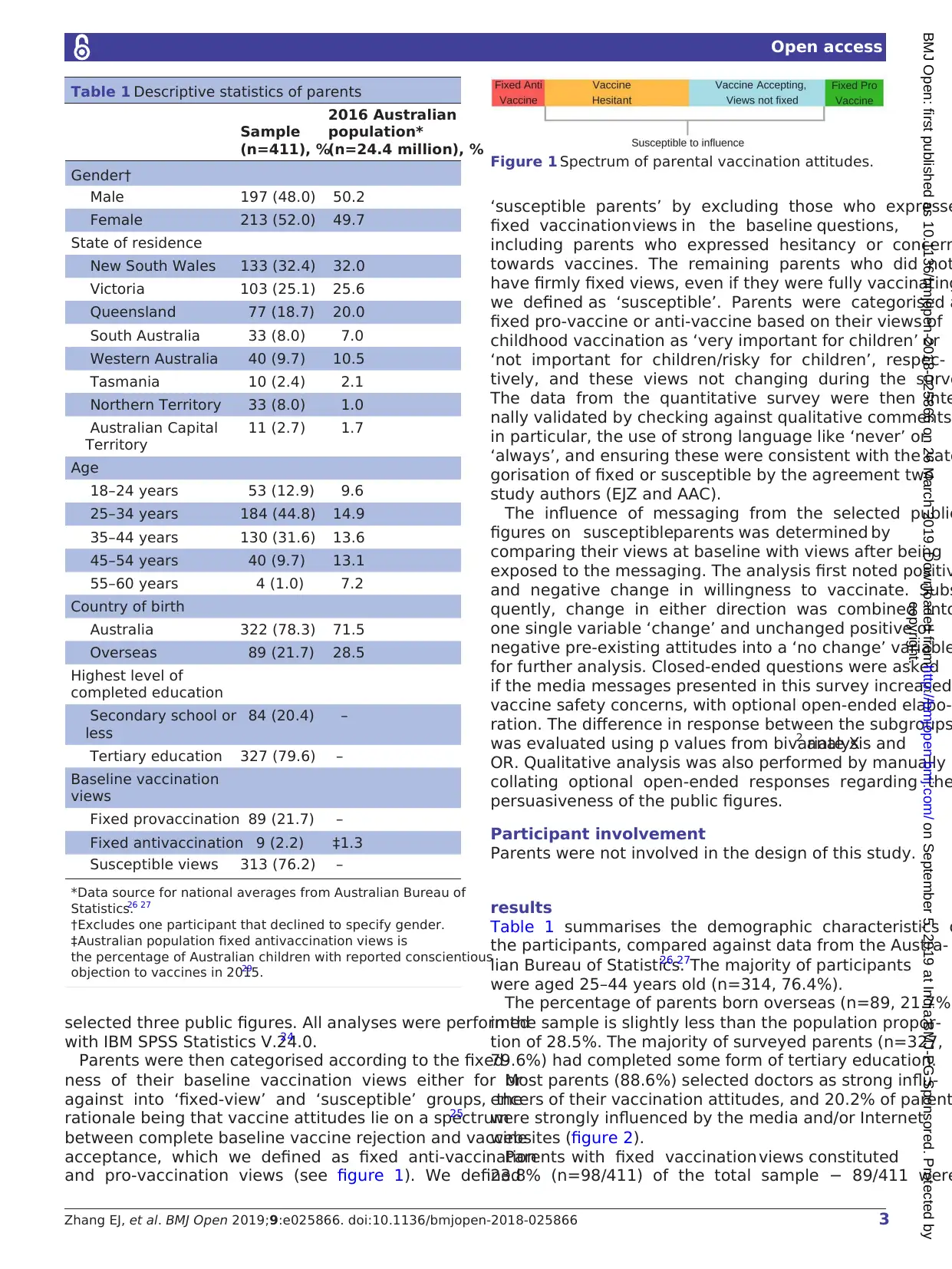

Most parents (88.6%) selected doctors as strong influ-

encers of their vaccination attitudes, and 20.2% of parent

were strongly influenced by the media and/or Internet

websites (figure 2).

Parents with fixed vaccination views constituted

23.8% (n=98/411) of the total sample − 89/411 were

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of parents

Sample

(n=411), %

2016 Australian

population*

(n=24.4 million), %

Gender†

Male 197 (48.0) 50.2

Female 213 (52.0) 49.7

State of residence

New South Wales 133 (32.4) 32.0

Victoria 103 (25.1) 25.6

Queensland 77 (18.7) 20.0

South Australia 33 (8.0) 7.0

Western Australia 40 (9.7) 10.5

Tasmania 10 (2.4) 2.1

Northern Territory 33 (8.0) 1.0

Australian Capital

Territory

11 (2.7) 1.7

Age

18–24 years 53 (12.9) 9.6

25–34 years 184 (44.8) 14.9

35–44 years 130 (31.6) 13.6

45–54 years 40 (9.7) 13.1

55–60 years 4 (1.0) 7.2

Country of birth

Australia 322 (78.3) 71.5

Overseas 89 (21.7) 28.5

Highest level of

completed education

Secondary school or

less

84 (20.4) –

Tertiary education 327 (79.6) –

Baseline vaccination

views

Fixed provaccination 89 (21.7) –

Fixed antivaccination 9 (2.2) ‡1.3

Susceptible views 313 (76.2) –

*Data source for national averages from Australian Bureau of

Statistics.26 27

†Excludes one participant that declined to specify gender.

‡Australian population fixed antivaccination views is

the percentage of Australian children with reported conscientious

objection to vaccines in 2015.29

Figure 1 Spectrum of parental vaccination attitudes.

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

Open access

selected three public figures. All analyses were performed

with IBM SPSS Statistics V.24.0.24

Parents were then categorised according to the fixed-

ness of their baseline vaccination views either for or

against into ‘fixed-view’ and ‘susceptible’ groups, the

rationale being that vaccine attitudes lie on a spectrum25

between complete baseline vaccine rejection and vaccine

acceptance, which we defined as fixed anti-vaccination

and pro-vaccination views (see figure 1). We defined

‘susceptible parents’ by excluding those who expresse

fixed vaccination views in the baseline questions,

including parents who expressed hesitancy or concern

towards vaccines. The remaining parents who did not

have firmly fixed views, even if they were fully vaccinating

we defined as ‘susceptible’. Parents were categorised a

fixed pro-vaccine or anti-vaccine based on their views of

childhood vaccination as ‘very important for children’ or

‘not important for children/risky for children’, respec-

tively, and these views not changing during the surve

The data from the quantitative survey were then inte

nally validated by checking against qualitative comments

in particular, the use of strong language like ‘never’ or

‘always’, and ensuring these were consistent with the cate

gorisation of fixed or susceptible by the agreement two

study authors (EJZ and AAC).

The influence of messaging from the selected public

figures on susceptibleparents was determined by

comparing their views at baseline with views after being

exposed to the messaging. The analysis first noted positiv

and negative change in willingness to vaccinate. Subs

quently, change in either direction was combined into

one single variable ‘change’ and unchanged positive or

negative pre-existing attitudes into a ‘no change’ variable

for further analysis. Closed-ended questions were asked

if the media messages presented in this survey increased

vaccine safety concerns, with optional open-ended elabo-

ration. The difference in response between the subgroups

was evaluated using p values from bivariate X2 analysis and

OR. Qualitative analysis was also performed by manually

collating optional open-ended responses regarding the

persuasiveness of the public figures.

Participant involvement

Parents were not involved in the design of this study.

results

Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics o

the participants, compared against data from the Austra-

lian Bureau of Statistics.26 27The majority of participants

were aged 25–44 years old (n=314, 76.4%).

The percentage of parents born overseas (n=89, 21.7%)

in the sample is slightly less than the population propor-

tion of 28.5%. The majority of surveyed parents (n=327,

79.6%) had completed some form of tertiary education.

Most parents (88.6%) selected doctors as strong influ-

encers of their vaccination attitudes, and 20.2% of parent

were strongly influenced by the media and/or Internet

websites (figure 2).

Parents with fixed vaccination views constituted

23.8% (n=98/411) of the total sample − 89/411 were

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of parents

Sample

(n=411), %

2016 Australian

population*

(n=24.4 million), %

Gender†

Male 197 (48.0) 50.2

Female 213 (52.0) 49.7

State of residence

New South Wales 133 (32.4) 32.0

Victoria 103 (25.1) 25.6

Queensland 77 (18.7) 20.0

South Australia 33 (8.0) 7.0

Western Australia 40 (9.7) 10.5

Tasmania 10 (2.4) 2.1

Northern Territory 33 (8.0) 1.0

Australian Capital

Territory

11 (2.7) 1.7

Age

18–24 years 53 (12.9) 9.6

25–34 years 184 (44.8) 14.9

35–44 years 130 (31.6) 13.6

45–54 years 40 (9.7) 13.1

55–60 years 4 (1.0) 7.2

Country of birth

Australia 322 (78.3) 71.5

Overseas 89 (21.7) 28.5

Highest level of

completed education

Secondary school or

less

84 (20.4) –

Tertiary education 327 (79.6) –

Baseline vaccination

views

Fixed provaccination 89 (21.7) –

Fixed antivaccination 9 (2.2) ‡1.3

Susceptible views 313 (76.2) –

*Data source for national averages from Australian Bureau of

Statistics.26 27

†Excludes one participant that declined to specify gender.

‡Australian population fixed antivaccination views is

the percentage of Australian children with reported conscientious

objection to vaccines in 2015.29

Figure 1 Spectrum of parental vaccination attitudes.

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4 Zhang EJ, et al. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-201

Open access

pro-vaccination and 9/411 were anti-vaccination. The

remaining 313 parents (76.2%) were defined as suscep-

tible. There were no significantdifferencesbetween

fixed-view and susceptible parents with regard to the

demographic characteristics of gender (p=0.544), age

(p=0.299), country of birth (p=0.827) and education

(p=0.247).

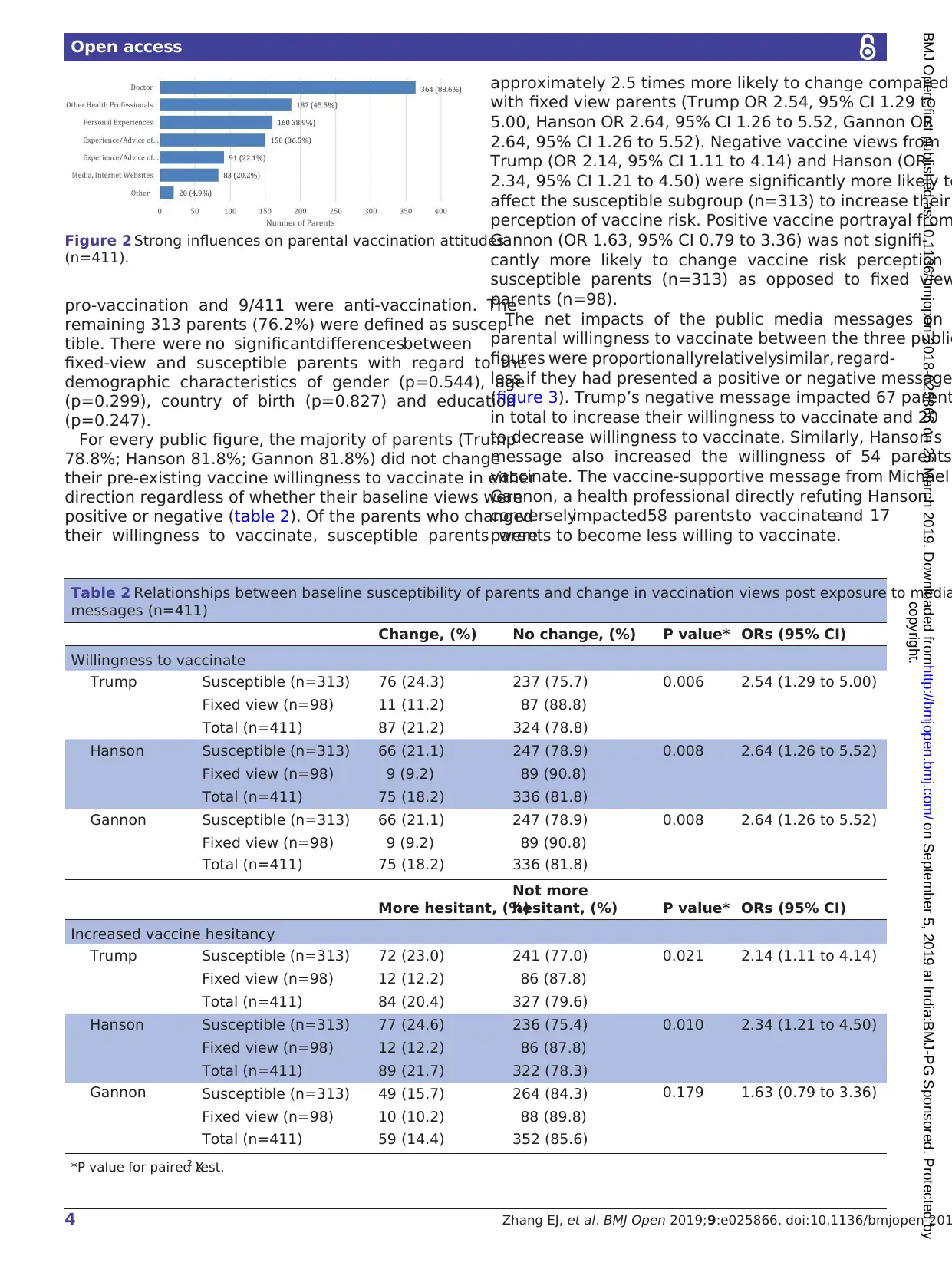

For every public figure, the majority of parents (Trump

78.8%; Hanson 81.8%; Gannon 81.8%) did not change

their pre-existing vaccine willingness to vaccinate in either

direction regardless of whether their baseline views were

positive or negative (table 2). Of the parents who changed

their willingness to vaccinate, susceptible parents were

approximately 2.5 times more likely to change compared

with fixed view parents (Trump OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.29 to

5.00, Hanson OR 2.64, 95% CI 1.26 to 5.52, Gannon OR

2.64, 95% CI 1.26 to 5.52). Negative vaccine views from

Trump (OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.11 to 4.14) and Hanson (OR

2.34, 95% CI 1.21 to 4.50) were significantly more likely to

affect the susceptible subgroup (n=313) to increase their

perception of vaccine risk. Positive vaccine portrayal from

Gannon (OR 1.63, 95% CI 0.79 to 3.36) was not signifi-

cantly more likely to change vaccine risk perception

susceptible parents (n=313) as opposed to fixed view

parents (n=98).

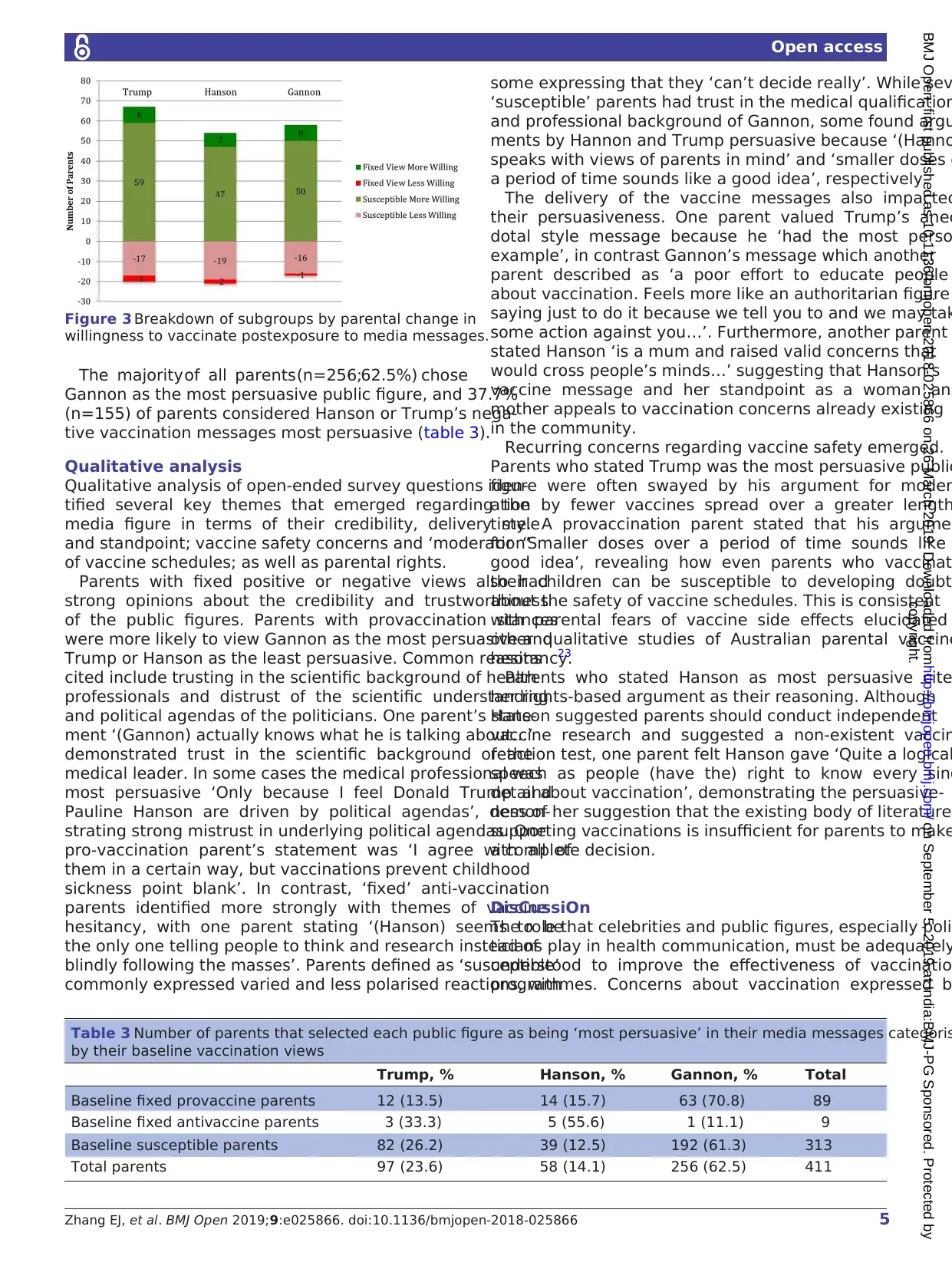

The net impacts of the public media messages on

parental willingness to vaccinate between the three public

figures were proportionallyrelativelysimilar, regard-

less if they had presented a positive or negative message

(figure 3). Trump’s negative message impacted 67 parent

in total to increase their willingness to vaccinate and 20

to decrease willingness to vaccinate. Similarly, Hanson’s

message also increased the willingness of 54 parents

vaccinate. The vaccine-supportive message from Michael

Gannon, a health professional directly refuting Hanson

converselyimpacted58 parents to vaccinateand 17

parents to become less willing to vaccinate.

Figure 2 Strong influences on parental vaccination attitudes

(n=411).

Table 2 Relationships between baseline susceptibility of parents and change in vaccination views post exposure to media

messages (n=411)

Change, (%) No change, (%) P value* ORs (95% CI)

Willingness to vaccinate

Trump Susceptible (n=313) 76 (24.3) 237 (75.7) 0.006 2.54 (1.29 to 5.00)

Fixed view (n=98) 11 (11.2) 87 (88.8)

Total (n=411) 87 (21.2) 324 (78.8)

Hanson Susceptible (n=313) 66 (21.1) 247 (78.9) 0.008 2.64 (1.26 to 5.52)

Fixed view (n=98) 9 (9.2) 89 (90.8)

Total (n=411) 75 (18.2) 336 (81.8)

Gannon Susceptible (n=313) 66 (21.1) 247 (78.9) 0.008 2.64 (1.26 to 5.52)

Fixed view (n=98) 9 (9.2) 89 (90.8)

Total (n=411) 75 (18.2) 336 (81.8)

More hesitant, (%)

Not more

hesitant, (%) P value* ORs (95% CI)

Increased vaccine hesitancy

Trump Susceptible (n=313) 72 (23.0) 241 (77.0) 0.021 2.14 (1.11 to 4.14)

Fixed view (n=98) 12 (12.2) 86 (87.8)

Total (n=411) 84 (20.4) 327 (79.6)

Hanson Susceptible (n=313) 77 (24.6) 236 (75.4) 0.010 2.34 (1.21 to 4.50)

Fixed view (n=98) 12 (12.2) 86 (87.8)

Total (n=411) 89 (21.7) 322 (78.3)

Gannon Susceptible (n=313) 49 (15.7) 264 (84.3) 0.179 1.63 (0.79 to 3.36)

Fixed view (n=98) 10 (10.2) 88 (89.8)

Total (n=411) 59 (14.4) 352 (85.6)

*P value for paired X2 test.

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

Open access

pro-vaccination and 9/411 were anti-vaccination. The

remaining 313 parents (76.2%) were defined as suscep-

tible. There were no significantdifferencesbetween

fixed-view and susceptible parents with regard to the

demographic characteristics of gender (p=0.544), age

(p=0.299), country of birth (p=0.827) and education

(p=0.247).

For every public figure, the majority of parents (Trump

78.8%; Hanson 81.8%; Gannon 81.8%) did not change

their pre-existing vaccine willingness to vaccinate in either

direction regardless of whether their baseline views were

positive or negative (table 2). Of the parents who changed

their willingness to vaccinate, susceptible parents were

approximately 2.5 times more likely to change compared

with fixed view parents (Trump OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.29 to

5.00, Hanson OR 2.64, 95% CI 1.26 to 5.52, Gannon OR

2.64, 95% CI 1.26 to 5.52). Negative vaccine views from

Trump (OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.11 to 4.14) and Hanson (OR

2.34, 95% CI 1.21 to 4.50) were significantly more likely to

affect the susceptible subgroup (n=313) to increase their

perception of vaccine risk. Positive vaccine portrayal from

Gannon (OR 1.63, 95% CI 0.79 to 3.36) was not signifi-

cantly more likely to change vaccine risk perception

susceptible parents (n=313) as opposed to fixed view

parents (n=98).

The net impacts of the public media messages on

parental willingness to vaccinate between the three public

figures were proportionallyrelativelysimilar, regard-

less if they had presented a positive or negative message

(figure 3). Trump’s negative message impacted 67 parent

in total to increase their willingness to vaccinate and 20

to decrease willingness to vaccinate. Similarly, Hanson’s

message also increased the willingness of 54 parents

vaccinate. The vaccine-supportive message from Michael

Gannon, a health professional directly refuting Hanson

converselyimpacted58 parents to vaccinateand 17

parents to become less willing to vaccinate.

Figure 2 Strong influences on parental vaccination attitudes

(n=411).

Table 2 Relationships between baseline susceptibility of parents and change in vaccination views post exposure to media

messages (n=411)

Change, (%) No change, (%) P value* ORs (95% CI)

Willingness to vaccinate

Trump Susceptible (n=313) 76 (24.3) 237 (75.7) 0.006 2.54 (1.29 to 5.00)

Fixed view (n=98) 11 (11.2) 87 (88.8)

Total (n=411) 87 (21.2) 324 (78.8)

Hanson Susceptible (n=313) 66 (21.1) 247 (78.9) 0.008 2.64 (1.26 to 5.52)

Fixed view (n=98) 9 (9.2) 89 (90.8)

Total (n=411) 75 (18.2) 336 (81.8)

Gannon Susceptible (n=313) 66 (21.1) 247 (78.9) 0.008 2.64 (1.26 to 5.52)

Fixed view (n=98) 9 (9.2) 89 (90.8)

Total (n=411) 75 (18.2) 336 (81.8)

More hesitant, (%)

Not more

hesitant, (%) P value* ORs (95% CI)

Increased vaccine hesitancy

Trump Susceptible (n=313) 72 (23.0) 241 (77.0) 0.021 2.14 (1.11 to 4.14)

Fixed view (n=98) 12 (12.2) 86 (87.8)

Total (n=411) 84 (20.4) 327 (79.6)

Hanson Susceptible (n=313) 77 (24.6) 236 (75.4) 0.010 2.34 (1.21 to 4.50)

Fixed view (n=98) 12 (12.2) 86 (87.8)

Total (n=411) 89 (21.7) 322 (78.3)

Gannon Susceptible (n=313) 49 (15.7) 264 (84.3) 0.179 1.63 (0.79 to 3.36)

Fixed view (n=98) 10 (10.2) 88 (89.8)

Total (n=411) 59 (14.4) 352 (85.6)

*P value for paired X2 test.

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5Zhang EJ, et al. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866

Open access

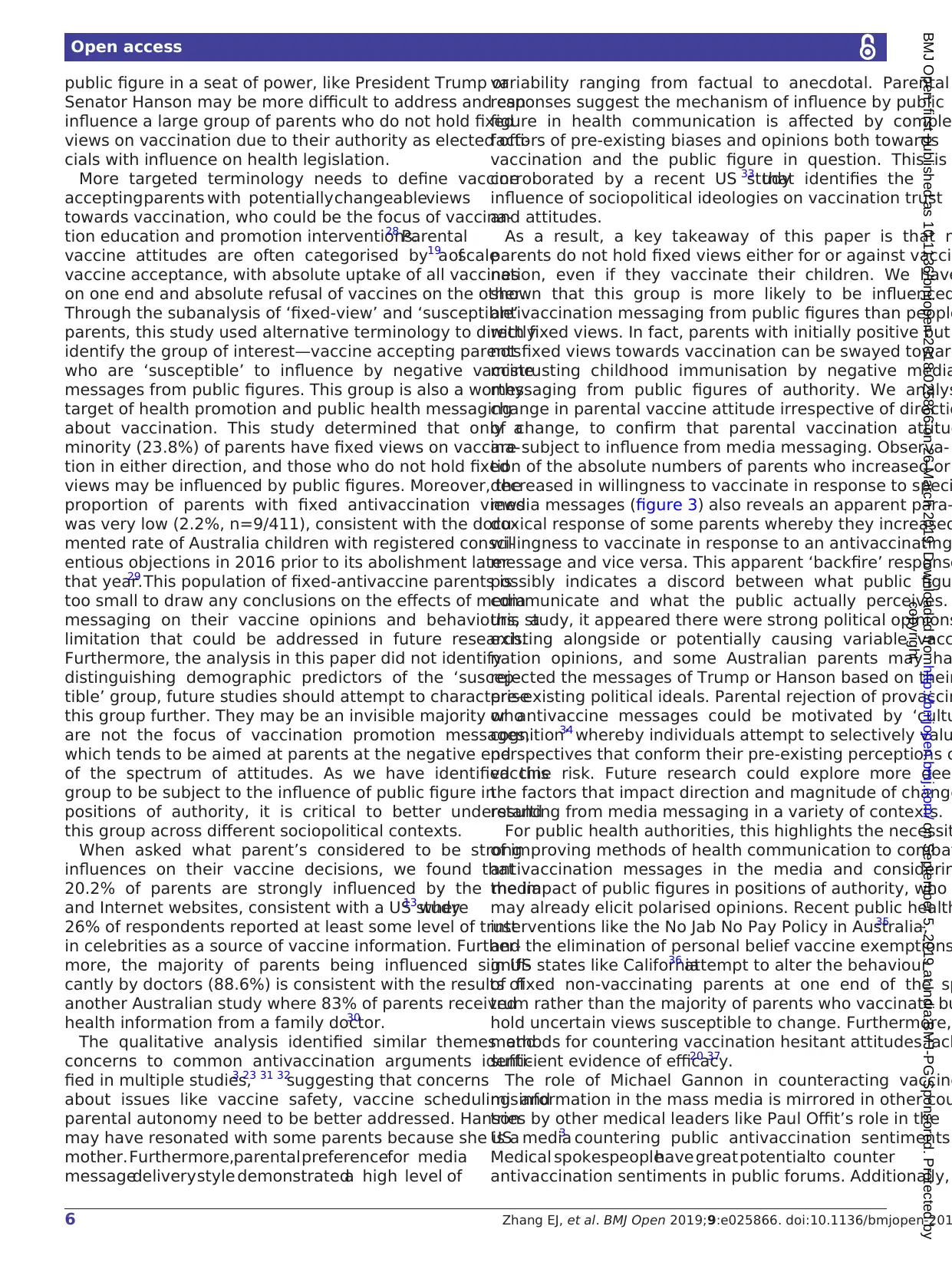

The majority of all parents (n=256;62.5%) chose

Gannon as the most persuasive public figure, and 37.7%

(n=155) of parents considered Hanson or Trump’s nega-

tive vaccination messages most persuasive (table 3).

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis of open-ended survey questions iden-

tified several key themes that emerged regarding the

media figure in terms of their credibility, delivery style

and standpoint; vaccine safety concerns and ‘moderation’

of vaccine schedules; as well as parental rights.

Parents with fixed positive or negative views also had

strong opinions about the credibility and trustworthiness

of the public figures. Parents with provaccination stances

were more likely to view Gannon as the most persuasive and

Trump or Hanson as the least persuasive. Common reasons

cited include trusting in the scientific background of health

professionals and distrust of the scientific understanding

and political agendas of the politicians. One parent’s state-

ment ‘(Gannon) actually knows what he is talking about…’

demonstrated trust in the scientific background of the

medical leader. In some cases the medical professional was

most persuasive ‘Only because I feel Donald Trump and

Pauline Hanson are driven by political agendas’, demon-

strating strong mistrust in underlying political agendas. One

pro-vaccination parent’s statement was ‘I agree with all of

them in a certain way, but vaccinations prevent childhood

sickness point blank’. In contrast, ‘fixed’ anti-vaccination

parents identified more strongly with themes of vaccine

hesitancy, with one parent stating ‘(Hanson) seems to be

the only one telling people to think and research instead of

blindly following the masses’. Parents defined as ‘susceptible’

commonly expressed varied and less polarised reactions, with

some expressing that they ‘can’t decide really’. While sev

‘susceptible’ parents had trust in the medical qualification

and professional background of Gannon, some found argu

ments by Hannon and Trump persuasive because ‘(Hanno

speaks with views of parents in mind’ and ‘smaller doses o

a period of time sounds like a good idea’, respectively.

The delivery of the vaccine messages also impacted

their persuasiveness. One parent valued Trump’s anec

dotal style message because he ‘had the most perso

example’, in contrast Gannon’s message which another

parent described as ‘a poor effort to educate people

about vaccination. Feels more like an authoritarian figure

saying just to do it because we tell you to and we may tak

some action against you…’. Furthermore, another parent

stated Hanson ‘is a mum and raised valid concerns that

would cross people’s minds…’ suggesting that Hanson’s

vaccine message and her standpoint as a woman and

mother appeals to vaccination concerns already existing

in the community.

Recurring concerns regarding vaccine safety emerged.

Parents who stated Trump was the most persuasive public

figure were often swayed by his argument for moder

ation by fewer vaccines spread over a greater length

time. A provaccination parent stated that his argumen

for ‘Smaller doses over a period of time sounds like

good idea’, revealing how even parents who vaccinat

their children can be susceptible to developing doubt

about the safety of vaccine schedules. This is consistent

with parental fears of vaccine side effects elucidated

other qualitative studies of Australian parental vaccine

hesitancy.23

Parents who stated Hanson as most persuasive cite

her rights-based argument as their reasoning. Although

Hanson suggested parents should conduct independent

vaccine research and suggested a non-existent vaccin

reaction test, one parent felt Hanson gave ‘Quite a logical

speech as people (have the) right to know every sing

detail about vaccination’, demonstrating the persuasive-

ness of her suggestion that the existing body of literature

supporting vaccinations is insufficient for parents to make

a complete decision.

DisCussiOn

The role that celebrities and public figures, especially poli

ticians play in health communication, must be adequately

understood to improve the effectiveness of vaccinatio

programmes. Concerns about vaccination expressed b

Figure 3 Breakdown of subgroups by parental change in

willingness to vaccinate postexposure to media messages.

Table 3 Number of parents that selected each public figure as being ‘most persuasive’ in their media messages categoris

by their baseline vaccination views

Trump, % Hanson, % Gannon, % Total

Baseline fixed provaccine parents 12 (13.5) 14 (15.7) 63 (70.8) 89

Baseline fixed antivaccine parents 3 (33.3) 5 (55.6) 1 (11.1) 9

Baseline susceptible parents 82 (26.2) 39 (12.5) 192 (61.3) 313

Total parents 97 (23.6) 58 (14.1) 256 (62.5) 411

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

Open access

The majority of all parents (n=256;62.5%) chose

Gannon as the most persuasive public figure, and 37.7%

(n=155) of parents considered Hanson or Trump’s nega-

tive vaccination messages most persuasive (table 3).

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis of open-ended survey questions iden-

tified several key themes that emerged regarding the

media figure in terms of their credibility, delivery style

and standpoint; vaccine safety concerns and ‘moderation’

of vaccine schedules; as well as parental rights.

Parents with fixed positive or negative views also had

strong opinions about the credibility and trustworthiness

of the public figures. Parents with provaccination stances

were more likely to view Gannon as the most persuasive and

Trump or Hanson as the least persuasive. Common reasons

cited include trusting in the scientific background of health

professionals and distrust of the scientific understanding

and political agendas of the politicians. One parent’s state-

ment ‘(Gannon) actually knows what he is talking about…’

demonstrated trust in the scientific background of the

medical leader. In some cases the medical professional was

most persuasive ‘Only because I feel Donald Trump and

Pauline Hanson are driven by political agendas’, demon-

strating strong mistrust in underlying political agendas. One

pro-vaccination parent’s statement was ‘I agree with all of

them in a certain way, but vaccinations prevent childhood

sickness point blank’. In contrast, ‘fixed’ anti-vaccination

parents identified more strongly with themes of vaccine

hesitancy, with one parent stating ‘(Hanson) seems to be

the only one telling people to think and research instead of

blindly following the masses’. Parents defined as ‘susceptible’

commonly expressed varied and less polarised reactions, with

some expressing that they ‘can’t decide really’. While sev

‘susceptible’ parents had trust in the medical qualification

and professional background of Gannon, some found argu

ments by Hannon and Trump persuasive because ‘(Hanno

speaks with views of parents in mind’ and ‘smaller doses o

a period of time sounds like a good idea’, respectively.

The delivery of the vaccine messages also impacted

their persuasiveness. One parent valued Trump’s anec

dotal style message because he ‘had the most perso

example’, in contrast Gannon’s message which another

parent described as ‘a poor effort to educate people

about vaccination. Feels more like an authoritarian figure

saying just to do it because we tell you to and we may tak

some action against you…’. Furthermore, another parent

stated Hanson ‘is a mum and raised valid concerns that

would cross people’s minds…’ suggesting that Hanson’s

vaccine message and her standpoint as a woman and

mother appeals to vaccination concerns already existing

in the community.

Recurring concerns regarding vaccine safety emerged.

Parents who stated Trump was the most persuasive public

figure were often swayed by his argument for moder

ation by fewer vaccines spread over a greater length

time. A provaccination parent stated that his argumen

for ‘Smaller doses over a period of time sounds like

good idea’, revealing how even parents who vaccinat

their children can be susceptible to developing doubt

about the safety of vaccine schedules. This is consistent

with parental fears of vaccine side effects elucidated

other qualitative studies of Australian parental vaccine

hesitancy.23

Parents who stated Hanson as most persuasive cite

her rights-based argument as their reasoning. Although

Hanson suggested parents should conduct independent

vaccine research and suggested a non-existent vaccin

reaction test, one parent felt Hanson gave ‘Quite a logical

speech as people (have the) right to know every sing

detail about vaccination’, demonstrating the persuasive-

ness of her suggestion that the existing body of literature

supporting vaccinations is insufficient for parents to make

a complete decision.

DisCussiOn

The role that celebrities and public figures, especially poli

ticians play in health communication, must be adequately

understood to improve the effectiveness of vaccinatio

programmes. Concerns about vaccination expressed b

Figure 3 Breakdown of subgroups by parental change in

willingness to vaccinate postexposure to media messages.

Table 3 Number of parents that selected each public figure as being ‘most persuasive’ in their media messages categoris

by their baseline vaccination views

Trump, % Hanson, % Gannon, % Total

Baseline fixed provaccine parents 12 (13.5) 14 (15.7) 63 (70.8) 89

Baseline fixed antivaccine parents 3 (33.3) 5 (55.6) 1 (11.1) 9

Baseline susceptible parents 82 (26.2) 39 (12.5) 192 (61.3) 313

Total parents 97 (23.6) 58 (14.1) 256 (62.5) 411

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

6 Zhang EJ, et al. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-201

Open access

public figure in a seat of power, like President Trump or

Senator Hanson may be more difficult to address and can

influence a large group of parents who do not hold fixed

views on vaccination due to their authority as elected offi-

cials with influence on health legislation.

More targeted terminology needs to define vaccine

accepting parents with potentially changeableviews

towards vaccination, who could be the focus of vaccina-

tion education and promotion interventions.28 Parental

vaccine attitudes are often categorised by a scale19 of

vaccine acceptance, with absolute uptake of all vaccines

on one end and absolute refusal of vaccines on the other.

Through the subanalysis of ‘fixed-view’ and ‘susceptible’

parents, this study used alternative terminology to directly

identify the group of interest—vaccine accepting parents

who are ‘susceptible’ to influence by negative vaccine

messages from public figures. This group is also a worthy

target of health promotion and public health messaging

about vaccination. This study determined that only a

minority (23.8%) of parents have fixed views on vaccina-

tion in either direction, and those who do not hold fixed

views may be influenced by public figures. Moreover, the

proportion of parents with fixed antivaccination views

was very low (2.2%, n=9/411), consistent with the docu-

mented rate of Australia children with registered consci-

entious objections in 2016 prior to its abolishment later

that year.29 This population of fixed-antivaccine parents is

too small to draw any conclusions on the effects of media

messaging on their vaccine opinions and behaviours, a

limitation that could be addressed in future research.

Furthermore, the analysis in this paper did not identify

distinguishing demographic predictors of the ‘suscep-

tible’ group, future studies should attempt to characterise

this group further. They may be an invisible majority who

are not the focus of vaccination promotion messages,

which tends to be aimed at parents at the negative end

of the spectrum of attitudes. As we have identified this

group to be subject to the influence of public figure in

positions of authority, it is critical to better understand

this group across different sociopolitical contexts.

When asked what parent’s considered to be strong

influences on their vaccine decisions, we found that

20.2% of parents are strongly influenced by the media

and Internet websites, consistent with a US study13 where

26% of respondents reported at least some level of trust

in celebrities as a source of vaccine information. Further-

more, the majority of parents being influenced signifi-

cantly by doctors (88.6%) is consistent with the results of

another Australian study where 83% of parents received

health information from a family doctor.30

The qualitative analysis identified similar themes and

concerns to common antivaccination arguments identi-

fied in multiple studies,3 23 31 32

suggesting that concerns

about issues like vaccine safety, vaccine scheduling and

parental autonomy need to be better addressed. Hanson

may have resonated with some parents because she is a

mother. Furthermore,parental preferencefor media

messagedelivery style demonstrateda high level of

variability ranging from factual to anecdotal. Parental

responses suggest the mechanism of influence by public

figure in health communication is affected by comple

factors of pre-existing biases and opinions both towards

vaccination and the public figure in question. This is

corroborated by a recent US study33 that identifies the

influence of sociopolitical ideologies on vaccination trust

and attitudes.

As a result, a key takeaway of this paper is that m

parents do not hold fixed views either for or against vacci

nation, even if they vaccinate their children. We have

shown that this group is more likely to be influenced

antivaccination messaging from public figures than people

with fixed views. In fact, parents with initially positive but

not fixed views towards vaccination can be swayed toward

mistrusting childhood immunisation by negative media

messaging from public figures of authority. We analys

change in parental vaccine attitude irrespective of directio

of change, to confirm that parental vaccination attitud

are subject to influence from media messaging. Observa-

tion of the absolute numbers of parents who increased or

decreased in willingness to vaccinate in response to speci

media messages (figure 3) also reveals an apparent para-

doxical response of some parents whereby they increased

willingness to vaccinate in response to an antivaccinating

message and vice versa. This apparent ‘backfire’ response

possibly indicates a discord between what public figu

communicate and what the public actually perceives.

this study, it appeared there were strong political opinions

existing alongside or potentially causing variable vacc

nation opinions, and some Australian parents may ha

rejected the messages of Trump or Hanson based on their

pre-existing political ideals. Parental rejection of provaccin

or antivaccine messages could be motivated by ‘cultu

cognition’34 whereby individuals attempt to selectively valu

perspectives that conform their pre-existing perceptions o

vaccine risk. Future research could explore more deep

the factors that impact direction and magnitude of change

resulting from media messaging in a variety of contexts.

For public health authorities, this highlights the necessit

of improving methods of health communication to combat

antivaccination messages in the media and considerin

the impact of public figures in positions of authority, who

may already elicit polarised opinions. Recent public health

interventions like the No Jab No Pay Policy in Australia,35

and the elimination of personal belief vaccine exemptions

in US states like California36 attempt to alter the behaviour

of fixed non-vaccinating parents at one end of the sp

trum rather than the majority of parents who vaccinate bu

hold uncertain views susceptible to change. Furthermore,

methods for countering vaccination hesitant attitudes lack

sufficient evidence of efficacy.20 37

The role of Michael Gannon in counteracting vaccine

misinformation in the mass media is mirrored in other cou

tries by other medical leaders like Paul Offit’s role in the

US media3 countering public antivaccination sentiments.

Medical spokespeoplehave great potentialto counter

antivaccination sentiments in public forums. Additionally,

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

Open access

public figure in a seat of power, like President Trump or

Senator Hanson may be more difficult to address and can

influence a large group of parents who do not hold fixed

views on vaccination due to their authority as elected offi-

cials with influence on health legislation.

More targeted terminology needs to define vaccine

accepting parents with potentially changeableviews

towards vaccination, who could be the focus of vaccina-

tion education and promotion interventions.28 Parental

vaccine attitudes are often categorised by a scale19 of

vaccine acceptance, with absolute uptake of all vaccines

on one end and absolute refusal of vaccines on the other.

Through the subanalysis of ‘fixed-view’ and ‘susceptible’

parents, this study used alternative terminology to directly

identify the group of interest—vaccine accepting parents

who are ‘susceptible’ to influence by negative vaccine

messages from public figures. This group is also a worthy

target of health promotion and public health messaging

about vaccination. This study determined that only a

minority (23.8%) of parents have fixed views on vaccina-

tion in either direction, and those who do not hold fixed

views may be influenced by public figures. Moreover, the

proportion of parents with fixed antivaccination views

was very low (2.2%, n=9/411), consistent with the docu-

mented rate of Australia children with registered consci-

entious objections in 2016 prior to its abolishment later

that year.29 This population of fixed-antivaccine parents is

too small to draw any conclusions on the effects of media

messaging on their vaccine opinions and behaviours, a

limitation that could be addressed in future research.

Furthermore, the analysis in this paper did not identify

distinguishing demographic predictors of the ‘suscep-

tible’ group, future studies should attempt to characterise

this group further. They may be an invisible majority who

are not the focus of vaccination promotion messages,

which tends to be aimed at parents at the negative end

of the spectrum of attitudes. As we have identified this

group to be subject to the influence of public figure in

positions of authority, it is critical to better understand

this group across different sociopolitical contexts.

When asked what parent’s considered to be strong

influences on their vaccine decisions, we found that

20.2% of parents are strongly influenced by the media

and Internet websites, consistent with a US study13 where

26% of respondents reported at least some level of trust

in celebrities as a source of vaccine information. Further-

more, the majority of parents being influenced signifi-

cantly by doctors (88.6%) is consistent with the results of

another Australian study where 83% of parents received

health information from a family doctor.30

The qualitative analysis identified similar themes and

concerns to common antivaccination arguments identi-

fied in multiple studies,3 23 31 32

suggesting that concerns

about issues like vaccine safety, vaccine scheduling and

parental autonomy need to be better addressed. Hanson

may have resonated with some parents because she is a

mother. Furthermore,parental preferencefor media

messagedelivery style demonstrateda high level of

variability ranging from factual to anecdotal. Parental

responses suggest the mechanism of influence by public

figure in health communication is affected by comple

factors of pre-existing biases and opinions both towards

vaccination and the public figure in question. This is

corroborated by a recent US study33 that identifies the

influence of sociopolitical ideologies on vaccination trust

and attitudes.

As a result, a key takeaway of this paper is that m

parents do not hold fixed views either for or against vacci

nation, even if they vaccinate their children. We have

shown that this group is more likely to be influenced

antivaccination messaging from public figures than people

with fixed views. In fact, parents with initially positive but

not fixed views towards vaccination can be swayed toward

mistrusting childhood immunisation by negative media

messaging from public figures of authority. We analys

change in parental vaccine attitude irrespective of directio

of change, to confirm that parental vaccination attitud

are subject to influence from media messaging. Observa-

tion of the absolute numbers of parents who increased or

decreased in willingness to vaccinate in response to speci

media messages (figure 3) also reveals an apparent para-

doxical response of some parents whereby they increased

willingness to vaccinate in response to an antivaccinating

message and vice versa. This apparent ‘backfire’ response

possibly indicates a discord between what public figu

communicate and what the public actually perceives.

this study, it appeared there were strong political opinions

existing alongside or potentially causing variable vacc

nation opinions, and some Australian parents may ha

rejected the messages of Trump or Hanson based on their

pre-existing political ideals. Parental rejection of provaccin

or antivaccine messages could be motivated by ‘cultu

cognition’34 whereby individuals attempt to selectively valu

perspectives that conform their pre-existing perceptions o

vaccine risk. Future research could explore more deep

the factors that impact direction and magnitude of change

resulting from media messaging in a variety of contexts.

For public health authorities, this highlights the necessit

of improving methods of health communication to combat

antivaccination messages in the media and considerin

the impact of public figures in positions of authority, who

may already elicit polarised opinions. Recent public health

interventions like the No Jab No Pay Policy in Australia,35

and the elimination of personal belief vaccine exemptions

in US states like California36 attempt to alter the behaviour

of fixed non-vaccinating parents at one end of the sp

trum rather than the majority of parents who vaccinate bu

hold uncertain views susceptible to change. Furthermore,

methods for countering vaccination hesitant attitudes lack

sufficient evidence of efficacy.20 37

The role of Michael Gannon in counteracting vaccine

misinformation in the mass media is mirrored in other cou

tries by other medical leaders like Paul Offit’s role in the

US media3 countering public antivaccination sentiments.

Medical spokespeoplehave great potentialto counter

antivaccination sentiments in public forums. Additionally,

copyright.

on September 5, 2019 at India:BMJ-PG Sponsored. Protected byhttp://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866 on 26 March 2019. Downloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7Zhang EJ, et al. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025866. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025866

Open access

other politicians may counter the antivaccination senti-

ments publicly, such as Barack Obama’s public response38

to the 2015 multistate US outbreak of measles, and the

bipartisan refutal of Hansons’ antivaccination comments by

Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and opposi-

tion leader Bill Shorten.39 In our study, Gannon’s provacci-

nation message did not make parents more hesitant about

vaccine safety, indicating that there is no significant back-

fire effect from provaccine messaging on these parents.

For parents with fixed views, positive vaccine messages

can backfire, causing vaccine-hesitant parents to entrench

their views, and conversely,antivaccinationmessages

can strengthen the views of vaccine-supporting parents,

confirmed by our study. Furthermore, many parents have

strong personal opinions regarding childhood vaccinations

and vaccination attitudes may be linked to the expression

of broader political and social views. It appears that political

polarisation plays a role in influencing vaccination attitudes

and behaviours in some parents.

COnClusiOn

Vaccine hesitancy research has focused on parents at one

end of the spectrum, with negative vaccination views. We

have shown that even vaccine-accepting parents with posi-

tive views can be influenced negatively by public figures

in positions of authority. Health communication should

be designed to target parents without fixed views, even

if they vaccinate their children. We suggest a different

lens through which to view parents and plan vaccination

messaging, as ‘fixed view’ and ‘susceptible’, respectively.

Politicians and public figures can influence parents’ views

of vaccination and are in a unique position of also being

able to directly influence health policy. They, therefore,

have a responsibility to provide carefully informed health

information. Politicians play a crucial role in upholding

community confidence in public health policies including

childhood vaccination.

Contributors We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all

named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for

authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed

in the manuscript has been approved by all of us. We confirm that we have given

due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this

work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of

publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we

have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property.

EJZ contributed to conception and design of the study, overseeing the whole study,

data management and writing the first draft of manuscript report; AAC and AH

contributed to statistical analysis and manuscript writing; CRM was responsible for

conception and design of the study, survey design, data analysis and manuscript

writing; All authors reviewed the final draft of manuscript.

Funding This study was supported by the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence,

Integrated Systems for Epidemic Response (ISER).

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

ethics approval The University of New South Wales ethics committee approved

(approval number: HC17045) the survey instrument and study protocol prior to data

collection.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement No additional data are available.

Open access This is an open access article distributed in accordance w

Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license,

permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-com

and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the origin

properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated

is non-commercial. See: http:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/by- nc/4. 0/.

reFerenCes

1. Salmon DA, Teret SP, MacIntyre CR, et al. Compulsory vaccination

and conscientious or philosophical exemptions: past, present, and

future. Lancet 2006;367:436–42.

2. Greenfeld KT. Who's afraid of Jenny McCarthy? Time 2010;175:40-5.

3. Gottlieb SD. Vaccine resistances reconsidered: Vaccine skeptics and

the Jenny McCarthy effect. Biosocieties 2016;11:152–74.

4. Beckwith RT. Transcript: Read the Full Text of the Second Republican

Debate. 2015 http:// time. com/ 4037239/ second- republican- debate-

transcript- cnn/.

5. Hanson P. In: Cassidy B, ed. Pauline Hanson joins Insiders: ABC

Insiders: Australian Broadcasting Company, 2017.

6. Beck CS, Aubuchon SM, McKenna TP, et al. Blurring personal health

and public priorities: an analysis of celebrity health narratives in the

public sphere. Health Commun 2014;29:244–56.

7. Noar SM, Willoughby JF, Myrick JG, et al. Public figure

announcements about cancer and opportunities for cancer

communication: a review and research agenda. Health Commun

2014;29:445–61.

8. Evans DGR, Barwell J, Eccles DM, et al. The Angelina Jolie effect:

how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of

cancer related services. Breast Cancer Research 2014;16.

9. Brown WJ, Basil MD. Media Celebrities and Public Health:

Responses to 'Magic' Johnson's HIV Disclosure and Its Impact on

AIDS Risk and High-Risk Behaviors. Health Commun 1995;7:345–70.

10. Chapman S, McLeod K, Wakefield M, et al. Impact of news of

celebrity illness on breast cancer screening: Kylie Minogue's breast

cancer diagnosis. Med J Aust 2005;183:247–50.

11. Cram P, Fendrick AM, Inadomi J, et al. The impact of a celebrity

promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: the

Katie Couric effect. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1601–5.

12. Borzekowski DL, Guan Y, Smith KC, et al. The Angelina effect:

immediate reach, grasp, and impact of going public. Genet Med

2014;16:516–21.

13. Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, et al. Sources and perceived

credibility of vaccine-safety information for parents. Pediatrics

2011;127(Suppl 1):S107–12.

14. Hiltzik M. Katie Couric backs off from her anti-vaccine show-but not

enough. Los Angeles Times 2013.

15. Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, et al. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular

hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental

disorder in children. Lancet 1998;351:637–41.

16. Womack S. Blair silent over Leo's MMR jab. The Telegraph 2001.

17. Meikle J. Tony Blair should have gone public over Leo's MMR jab,

says Sir Liam Donaldson. The Guardian 2013.

18. Phillip A, Sun LH, Bernstein L. Vaccine skeptic Robert Kennedy Jr.

says Trump asked him to lead commission on ‘vaccine safety’. The

Washington Post 2017.

19. MacDonald NE. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine

hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015;33:4161–4

20. Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, et al. Effective messages in vaccine

promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2014;133:e835–42.

21. SAGE Working Group. Report of the SAGE working group on vaccine

hesitancy: WHO, 2014.

22. Bedford H, Attwell K, Danchin M, et al. Vaccine hesitancy, refusal

and access barriers: The need for clarity in terminology. Vaccine

2018;36:6556–8.

23. Enkel SL, Attwell K, Snelling TL, et al. 'Hesitant compliers':

Qualitative analysis of concerned fully-vaccinating parents. Vaccine

2018;36:6459–63.

24. IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 24.0. Armonk,

NY: IBM Corp, 2016.

25. Gowda C, Dempsey AF. The rise (and fall?) of parental vaccine

hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013;9:1755–62.

26. Statistics ABo. Australian Demographic Statistics. Canberra:

Commonwealth of Australia, 2017:36–8.

27. Perreault L. Obesity in adults: Overview of management: UpToDate.

2017 https://www.uptodate. com/ contents/ obesity- in- adults-

overview- of- management? search=obesity& source= search_ result&