ECC NCS1102D Interview Analysis Essay: Professional Conduct & Comm.

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/21

|7

|8001

|86

Essay

AI Summary

This essay presents an analysis of an interview conducted for the NCS1102D course, focusing on professional conduct and communication. The analysis adheres to the specified format, including an ECC cover sheet, title page, contents page, and end-text reference list. The essay emphasizes logical presentation, clear and concise expression, and proper paraphrasing with appropriate referencing. It avoids direct quotes and lecture notes as primary sources. The structure includes well-formed paragraphs and sentences, ensuring a comprehensive and insightful exploration of the interview's key aspects within the context of professional communication.

A New, Evidence-based Estimate of Patient Harms

Associated with HospitalCare

John T.James,PhD

Objectives:Based on 1984 data developed from reviews of medical

records of patients treated in New York hospitals, the Institute of Med-

icine estimated that up to 98,000 Americans die each year from medical

errors.The basis of this estimate is nearly 3 decades old;herein,an

updated estimate is developed from modern studies published from

2008 to 2011.

Methods:A literature review identified 4 limited studies thatused

primarily the Global Trigger Tool to flag specific evidence in medical

records, such as medication stop orders or abnormal laboratory results,

which point to an adverse event that may have harmed a patient.Ulti-

mately, a physician must concur on the findings of an adverse event and

then classify the severity of patient harm.

Results:Using a weighted average of the 4 studies,a lower limitof

210,000 deaths per year was associated with preventable harm in hos-

pitals.Given limitations in the search capability of the Global Trigger

Tool and the incompleteness of medical records on which the Tool de-

pends, the true number of premature deaths associated with preventable

harm to patients was estimated at more than 400,000 per year. Serious

harm seems to be 10- to 20-fold more common than lethal harm.

Conclusions:The epidemic of patient harm in hospitals must be taken

more seriously if it is to be curtailed. Fully engaging patients and their

advocatesduring hospitalcare,systematically seeking the patients’

voice in identifying harms,transparentaccountability forharm,and

intentionalcorrection of rootcauses of harm willbe necessary to ac-

complish this goal.

Key Words: patient harm,preventable adverse events,transparency,

patient-centered care,Global Trigger Tool,medical errors

(J Patient Saf 2013;9: 122Y128)

‘‘Allmen make mistakes, but a good man

yields when he knows his course is wrong,

and repairs the evil. The only crime is

pride.’’V Sophocles, Antigone’’

M edical care in the United States is technically complex at

the individualprovider level,atthe system level,and at

the nationallevel.The amountof new knowledge generated

each year by clinical research that applies directly to patien

can easily overwhelm the individualphysician trying to opti-

mize the care of his patients.1 Furthermore, the lack of a well-

integrated and comprehensive continuing education system

the health professions is a major contributing factor to know

edge and performance deficiencies at the individual and sys

level.2 Guidelines forphysicians to optimize patientcare are

quickly outof date and can be biased by those who write the

guidelines.3Y5At the system level,hospitals struggle with staff-

ing issues, making suitable technology available for patient

and executing effective handoffs between shifts and also be

inpatient and outpatient care.6 Increased production demands in

cost-driven institutions may increase the risk of preventable

verse events (PAEs). The United States trails behind other d

oped nations in implementing electronic medical records fo

citizens.7 Hence,the information a physician needs to optimize

care of a patient is often unavailable.

At the nationallevel,our country is distinguished for its

patchwork of medical care subsystems that can require pat

to bounce around in a complex maze of providers as they se

effective and affordable care.Because of increased production

demands, providers may be expected to give care in subop

working conditions,with decreased staff,and a shortage of

physicians, which leads to fatigue and burnout. It should be

surprise that PAEs that harm patients are frighteningly com

in this highly technical, rapidly changing, and poorly integra

industry.The picture is further complicated by a lack of trans-

parency and limited accountability for errors that harm pati8,9

There are at least 3 time-based categories of PAEs reco

nized in patients that are or have been hospitalized. The bro

definition encompasses allunexpected and harmfulexperience

thata patientencounters as a resultof being in the care of a

medicalprofessionalor system because high quality,evidence-

based medical care was not delivered during hospitalization

harmful outcomes may be realized immediately, delayed fo

or months, or even delayed many years. An example of imm

harm is excess bleeding because of an overdose of an antic

lant drug such as that which occurred to the twins born to D

Quaid and his wife.10 An example of harm that is not apparent

for weeks or months is infection with Hepatitis C virus as a r

of contaminated chemotherapy equipment.11 Harm thatoccurs

years later is exemplified by a nearly lethal pneumococcal i

tion in a patient that had had a splenectomy many years ag

was never vaccinated against this infection risk as guideline

prompts require.12

METHODS

The approach to the problem ofidentifying and enumer-

ating PAEs was 4-fold: (1) distinguish types of PAEs that ma

occur in hospitals, (2) characterize preventability in the con

of the GlobalTriggerTool (GTT), (3) search contemporary

medical literature for the prevalence and severity of PAEs th

have been enumerated by credible investigators based on m

REVIEW ARTICLE

122 www.journalpatientsafety.com J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013

From the Patient Safety America, Houston, Texas.

Correspondence: John T. James, PhD, Patient Safety America,

14503 Windy Ridge Lane, Suite 200, Houston, TX 77062

(email: john.t.james@earthlink.net).

The author discloses no conflict of interest.

Sources of support: none.

Copyright * 2013 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Associated with HospitalCare

John T.James,PhD

Objectives:Based on 1984 data developed from reviews of medical

records of patients treated in New York hospitals, the Institute of Med-

icine estimated that up to 98,000 Americans die each year from medical

errors.The basis of this estimate is nearly 3 decades old;herein,an

updated estimate is developed from modern studies published from

2008 to 2011.

Methods:A literature review identified 4 limited studies thatused

primarily the Global Trigger Tool to flag specific evidence in medical

records, such as medication stop orders or abnormal laboratory results,

which point to an adverse event that may have harmed a patient.Ulti-

mately, a physician must concur on the findings of an adverse event and

then classify the severity of patient harm.

Results:Using a weighted average of the 4 studies,a lower limitof

210,000 deaths per year was associated with preventable harm in hos-

pitals.Given limitations in the search capability of the Global Trigger

Tool and the incompleteness of medical records on which the Tool de-

pends, the true number of premature deaths associated with preventable

harm to patients was estimated at more than 400,000 per year. Serious

harm seems to be 10- to 20-fold more common than lethal harm.

Conclusions:The epidemic of patient harm in hospitals must be taken

more seriously if it is to be curtailed. Fully engaging patients and their

advocatesduring hospitalcare,systematically seeking the patients’

voice in identifying harms,transparentaccountability forharm,and

intentionalcorrection of rootcauses of harm willbe necessary to ac-

complish this goal.

Key Words: patient harm,preventable adverse events,transparency,

patient-centered care,Global Trigger Tool,medical errors

(J Patient Saf 2013;9: 122Y128)

‘‘Allmen make mistakes, but a good man

yields when he knows his course is wrong,

and repairs the evil. The only crime is

pride.’’V Sophocles, Antigone’’

M edical care in the United States is technically complex at

the individualprovider level,atthe system level,and at

the nationallevel.The amountof new knowledge generated

each year by clinical research that applies directly to patien

can easily overwhelm the individualphysician trying to opti-

mize the care of his patients.1 Furthermore, the lack of a well-

integrated and comprehensive continuing education system

the health professions is a major contributing factor to know

edge and performance deficiencies at the individual and sys

level.2 Guidelines forphysicians to optimize patientcare are

quickly outof date and can be biased by those who write the

guidelines.3Y5At the system level,hospitals struggle with staff-

ing issues, making suitable technology available for patient

and executing effective handoffs between shifts and also be

inpatient and outpatient care.6 Increased production demands in

cost-driven institutions may increase the risk of preventable

verse events (PAEs). The United States trails behind other d

oped nations in implementing electronic medical records fo

citizens.7 Hence,the information a physician needs to optimize

care of a patient is often unavailable.

At the nationallevel,our country is distinguished for its

patchwork of medical care subsystems that can require pat

to bounce around in a complex maze of providers as they se

effective and affordable care.Because of increased production

demands, providers may be expected to give care in subop

working conditions,with decreased staff,and a shortage of

physicians, which leads to fatigue and burnout. It should be

surprise that PAEs that harm patients are frighteningly com

in this highly technical, rapidly changing, and poorly integra

industry.The picture is further complicated by a lack of trans-

parency and limited accountability for errors that harm pati8,9

There are at least 3 time-based categories of PAEs reco

nized in patients that are or have been hospitalized. The bro

definition encompasses allunexpected and harmfulexperience

thata patientencounters as a resultof being in the care of a

medicalprofessionalor system because high quality,evidence-

based medical care was not delivered during hospitalization

harmful outcomes may be realized immediately, delayed fo

or months, or even delayed many years. An example of imm

harm is excess bleeding because of an overdose of an antic

lant drug such as that which occurred to the twins born to D

Quaid and his wife.10 An example of harm that is not apparent

for weeks or months is infection with Hepatitis C virus as a r

of contaminated chemotherapy equipment.11 Harm thatoccurs

years later is exemplified by a nearly lethal pneumococcal i

tion in a patient that had had a splenectomy many years ag

was never vaccinated against this infection risk as guideline

prompts require.12

METHODS

The approach to the problem ofidentifying and enumer-

ating PAEs was 4-fold: (1) distinguish types of PAEs that ma

occur in hospitals, (2) characterize preventability in the con

of the GlobalTriggerTool (GTT), (3) search contemporary

medical literature for the prevalence and severity of PAEs th

have been enumerated by credible investigators based on m

REVIEW ARTICLE

122 www.journalpatientsafety.com J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013

From the Patient Safety America, Houston, Texas.

Correspondence: John T. James, PhD, Patient Safety America,

14503 Windy Ridge Lane, Suite 200, Houston, TX 77062

(email: john.t.james@earthlink.net).

The author discloses no conflict of interest.

Sources of support: none.

Copyright * 2013 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

records assessed by the GTT, and (4) compare the studies found

by the literature search.

Types of PAEs

The cause of PAEs in hospitals may be separated into these

categories:

& Errors of commission,

& Errors of omission,

& Errors of communication,

& Errors of context, and

& Diagnostic errors

Thesedistinctionsare importantbecauseinvestigators

searching for preventable harm must be aware of what they can

find and whatthey cannotfind.The easiesterror to detectin

medical records is an error of commission. This occurs when a

mistaken action harms a patient either because it was the wrong

action or it was the right action but performed improperly. For

example,the patientmay need his gallbladderremoved,but

during the surgery,the intestine is nicked,and the patientde-

velops a serious infection,such as was alleged to be the cause

leading to the death of Representative John Murtha.Errors of

omission can be detected in medical records when an obvious

action was necessary to healthe patient,yetit was notper-

formed at all. For example, a patient may need a A-blocker, but

because itwas notprescribed,the patientdied prematurely.13

Errors of omission because of failure to follow evidence-based

guidelines are much more difficultto detect,partly because

there are many complex guidelines and also because adverse

consequences of failure to follow guidelines may be delayed

until after discharge.14,15

Errors ofcommunication can occurbetween 2 ormore

providers or between providers and patient.One example of a

lethalerrorof communication between providerand patient

occurred when cardiologists failed to warn their19-year-old

patient not to run.The patient had experienced syncope while

running,and 5 days ofinpatient,diagnostic testing were in-

conclusive;however,his cardiologists knew he was notready

to return to running butfailed to warn him againstthis risk.

Having not been warned against running,he resumed running

and died 3 weeks later while running.15

Contextual errors occur when a physician fails to take into

account unique constraints in a patient’s life that could bear on

successful,postdischarge treatment.For example,the patient

may lack the cognitive ability to comply with a medicaltreat-

mentplan ormay nothave reasonable accessto follow-up

care.16 Diagnostic errorsresulting in delayed treatment,the

wrong treatment,or no effective treatmentmay also be con-

sidered separately,although a smallsubsetof these mightbe

included as errors of commission or omission.For example,a

diagnostic error may lead to harm from errors of commission by

overtreatment or mistreatment of the patient until the mistake is

discovered.The apparent eagerness of the U.S.health-care in-

dustry to over diagnose patients often leads to harmful conse-

quences for patients.17

Preventability and the Global Trigger Tool

The prevailing view is that ‘‘preventability’’ of an adverse

eventlinks to the commission ofan identifiable errorthat

caused an adverse event. Adverse events that cannot be traced to

a likely error should not be called ‘‘preventable.’’ The portion of

adverse events thatare deemed preventable tends to be about

50% to 60%;however,recently,experts have postulated that

virtually alladverse events they identified with the ‘‘GTT are

preventable.’’18 The GTT dependson systematic review of

medicalrecords by persons trained to find specific clues or

triggers suggesting thatan adverse eventhas taken place.For

example, triggers might include orders to stop a medication

abnormallab result,or prescription of an antidote medication

such as naloxone. As a final step, the examination of the rec

mustbe validated by 1 or more physicians.As will be shown

shortly,the methods used to find adverse events in hospital

medicalrecords targetprimarily errors of commission and are

much less likely to find harm from errors of omission,com-

munication,context,or missed diagnosis.19 There are some

overlaps in these categories and cascades of harmful events

ensue from a single rootcause.A ‘‘perfectstorm’’ of unrec-

ognized butcorrectable medicalerrors can resultin serious

harm or death.15,20

Literature Search

Our literature search included the following three terms:

medicalerror,globaltriggertool,and hospital.We searched

Pub Med and ‘‘reports and publications’’ from the governme

Web site http://oig.hhs.gov. Those searches turned up 20 ar

published between 2006 and 2012, of which, 4 were found t

suitable for the present analysis. The unsuitable studies incl

studies of populations outside the United States,studies con-

fined to narrow hospital populations (e.g., intensive care uni

studies of ambulatory patients,studies involving only method-

ologicalcomparisons,adverse-eventissue papers,failures of

incident reporting systems, and studies that did not classify

severity of the harm associated with adverse events.

Characterization of the Core Studies

The 4 key studies were reviewed for similarity and differ

ence in methods used to find adverse events. It was found t

each one employed similar methods to flag,confirm, and then

classify adverse events according to level of harm.All studies

used a 2-tier approach thatconsisted of screening of medical

records by nonphysicians, usually nurses or pharmacists, to

suspectevents.In the second tier,physiciansexamined the

suspect events to determine if a genuine adverse event had

curred and,if so, the levelof seriousness of the event.In all

studies, the GTT from the Institute for Healthcare Improvem

was the primary screening tool;21however, there were variations

in the supplementary tools used to detect potential adverse

A 2008 pilotstudy by the Office ofInspectorGeneral

(OIG) of the Department of Health and Human Services used

5 methods in its search for adverse eventsVnurse reviews us

the GTT, conditions that were not present on admission (POA

beneficiary interviews,hospitalincidence reports,and patient

safety indicators.22 The pilot study revealed that the GTT cap-

tured the highestpercentage (78%)of the events ultimately

deemed to be adverse events in the second tier review by p

sicians.The use ofPOA indicatorcodes was second bestat

61%.Together,these methods were found to identify 94% of

the flags thatled physicians to declare thatan adverse event

had taken place.A more comprehensive OIG study in 2010

employed these 2 screening methodsand a third based on

whetherthe patienthad been readmitted to the hospitalwith

30 days of discharge from the last discharge during the Octo

2008 index period.23

A study by Classen and colleagues also employed the GT

along with Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patie

Safety Indicators (PSIs) and hospital reports of adverse even

Of the 167 flagged events thatultimately were deemed true

adverse events by physician review,the GTT detected 90% in

the severity levels F through I(Table 1).18 The longitudinal

J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013 Patient Harms Associated with HospitalCare

* 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins www.journalpatientsafety.com123

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

by the literature search.

Types of PAEs

The cause of PAEs in hospitals may be separated into these

categories:

& Errors of commission,

& Errors of omission,

& Errors of communication,

& Errors of context, and

& Diagnostic errors

Thesedistinctionsare importantbecauseinvestigators

searching for preventable harm must be aware of what they can

find and whatthey cannotfind.The easiesterror to detectin

medical records is an error of commission. This occurs when a

mistaken action harms a patient either because it was the wrong

action or it was the right action but performed improperly. For

example,the patientmay need his gallbladderremoved,but

during the surgery,the intestine is nicked,and the patientde-

velops a serious infection,such as was alleged to be the cause

leading to the death of Representative John Murtha.Errors of

omission can be detected in medical records when an obvious

action was necessary to healthe patient,yetit was notper-

formed at all. For example, a patient may need a A-blocker, but

because itwas notprescribed,the patientdied prematurely.13

Errors of omission because of failure to follow evidence-based

guidelines are much more difficultto detect,partly because

there are many complex guidelines and also because adverse

consequences of failure to follow guidelines may be delayed

until after discharge.14,15

Errors ofcommunication can occurbetween 2 ormore

providers or between providers and patient.One example of a

lethalerrorof communication between providerand patient

occurred when cardiologists failed to warn their19-year-old

patient not to run.The patient had experienced syncope while

running,and 5 days ofinpatient,diagnostic testing were in-

conclusive;however,his cardiologists knew he was notready

to return to running butfailed to warn him againstthis risk.

Having not been warned against running,he resumed running

and died 3 weeks later while running.15

Contextual errors occur when a physician fails to take into

account unique constraints in a patient’s life that could bear on

successful,postdischarge treatment.For example,the patient

may lack the cognitive ability to comply with a medicaltreat-

mentplan ormay nothave reasonable accessto follow-up

care.16 Diagnostic errorsresulting in delayed treatment,the

wrong treatment,or no effective treatmentmay also be con-

sidered separately,although a smallsubsetof these mightbe

included as errors of commission or omission.For example,a

diagnostic error may lead to harm from errors of commission by

overtreatment or mistreatment of the patient until the mistake is

discovered.The apparent eagerness of the U.S.health-care in-

dustry to over diagnose patients often leads to harmful conse-

quences for patients.17

Preventability and the Global Trigger Tool

The prevailing view is that ‘‘preventability’’ of an adverse

eventlinks to the commission ofan identifiable errorthat

caused an adverse event. Adverse events that cannot be traced to

a likely error should not be called ‘‘preventable.’’ The portion of

adverse events thatare deemed preventable tends to be about

50% to 60%;however,recently,experts have postulated that

virtually alladverse events they identified with the ‘‘GTT are

preventable.’’18 The GTT dependson systematic review of

medicalrecords by persons trained to find specific clues or

triggers suggesting thatan adverse eventhas taken place.For

example, triggers might include orders to stop a medication

abnormallab result,or prescription of an antidote medication

such as naloxone. As a final step, the examination of the rec

mustbe validated by 1 or more physicians.As will be shown

shortly,the methods used to find adverse events in hospital

medicalrecords targetprimarily errors of commission and are

much less likely to find harm from errors of omission,com-

munication,context,or missed diagnosis.19 There are some

overlaps in these categories and cascades of harmful events

ensue from a single rootcause.A ‘‘perfectstorm’’ of unrec-

ognized butcorrectable medicalerrors can resultin serious

harm or death.15,20

Literature Search

Our literature search included the following three terms:

medicalerror,globaltriggertool,and hospital.We searched

Pub Med and ‘‘reports and publications’’ from the governme

Web site http://oig.hhs.gov. Those searches turned up 20 ar

published between 2006 and 2012, of which, 4 were found t

suitable for the present analysis. The unsuitable studies incl

studies of populations outside the United States,studies con-

fined to narrow hospital populations (e.g., intensive care uni

studies of ambulatory patients,studies involving only method-

ologicalcomparisons,adverse-eventissue papers,failures of

incident reporting systems, and studies that did not classify

severity of the harm associated with adverse events.

Characterization of the Core Studies

The 4 key studies were reviewed for similarity and differ

ence in methods used to find adverse events. It was found t

each one employed similar methods to flag,confirm, and then

classify adverse events according to level of harm.All studies

used a 2-tier approach thatconsisted of screening of medical

records by nonphysicians, usually nurses or pharmacists, to

suspectevents.In the second tier,physiciansexamined the

suspect events to determine if a genuine adverse event had

curred and,if so, the levelof seriousness of the event.In all

studies, the GTT from the Institute for Healthcare Improvem

was the primary screening tool;21however, there were variations

in the supplementary tools used to detect potential adverse

A 2008 pilotstudy by the Office ofInspectorGeneral

(OIG) of the Department of Health and Human Services used

5 methods in its search for adverse eventsVnurse reviews us

the GTT, conditions that were not present on admission (POA

beneficiary interviews,hospitalincidence reports,and patient

safety indicators.22 The pilot study revealed that the GTT cap-

tured the highestpercentage (78%)of the events ultimately

deemed to be adverse events in the second tier review by p

sicians.The use ofPOA indicatorcodes was second bestat

61%.Together,these methods were found to identify 94% of

the flags thatled physicians to declare thatan adverse event

had taken place.A more comprehensive OIG study in 2010

employed these 2 screening methodsand a third based on

whetherthe patienthad been readmitted to the hospitalwith

30 days of discharge from the last discharge during the Octo

2008 index period.23

A study by Classen and colleagues also employed the GT

along with Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patie

Safety Indicators (PSIs) and hospital reports of adverse even

Of the 167 flagged events thatultimately were deemed true

adverse events by physician review,the GTT detected 90% in

the severity levels F through I(Table 1).18 The longitudinal

J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013 Patient Harms Associated with HospitalCare

* 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins www.journalpatientsafety.com123

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

study by Landrigan and colleagues relied on the GTT and POA

indicators to flag possible adverse events. Like the other studies,

the ultimate determination of a genuine adverse event and the

severity ofthe eventwere judged by physicians during the

second-tieranalysis.24 Although there are slightvariations in

the approach used to discover flags in the records examined by

the 4 studies, the GTT was the core method placed in the hands

of trained and experienced nurses. All studies used a second tier

requiring physicians to determine whethera flag signaled a

genuine adverse event and, if so, then assign a severity level to

that event.All studies used the National Coordinating Council

for Medication Reporting and Prevention scale (Table 1).

RESULTS

Recentdata from the 4 key studies provide a more com-

prehensive, evidence-based estimate of the number of lethal and

serious medical errors than the one provided by the Institute of

Medicine (IOM).25These data are compiled in Table 2, and the

studies are described below.

A pilot study by the OIG was published in 2008 in an effort

to explore the effectivenessof search methodsfor adverse

events.21As noted in the methods section, this study relied on 5

search methods for flagging potential adverse events in medical

records but did not specify whether such events were prevent-

able. The 278 medical records reviewed by screeners and phy-

sicianswere notrandomly selected to be representative of

Medicare hospitalizations; instead, they originated from hospi-

tals in 2 unspecified counties. Of the 51 serious adverse events

identified,only 3 were on the National Quality Forum’s list of

serious reportable events and only 11 were on Medicare’s Hospital

Acquired Condition (HAC) list. In 2010, the OIG estimated ad-

verse events in hospitalized Medicare patients.23

Investigators looked atthe medicalrecords of780 ran-

domly selected patients chosen to represent the 1 million Medi-

care patients‘‘discharged’’from hospitals in the month of

October 2008.The total number of hospital stays for the 780

patients during this period was 838 because some of the ben-

eficiaries were hospitalized and discharged more than once

during the 1-month index period.Using primarily the GTT

developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to find

adverse events, investigators found 128 serious adverse events

(level of harm F, G, H, or I) that caused harm to patients, and an

adverse event contributed to the deaths of 12 of those patients.

Seven of these deaths were medication related,2 were from

blood stream infections,2 were from aspiration,and the 12th

one was linked to ventilator-associated pneumonia. Only 2 of

these events were on the National Quality Forum list, and none

were on the Medicare HAC list.The authors ofthis report

estimated that ‘‘events’’ contributed to the deaths of 1.5 % (12/

780) of the 1 million Medicare patients hospitalized in October

2008.Thatamounts to 15,000 per month or 180,000 per year.

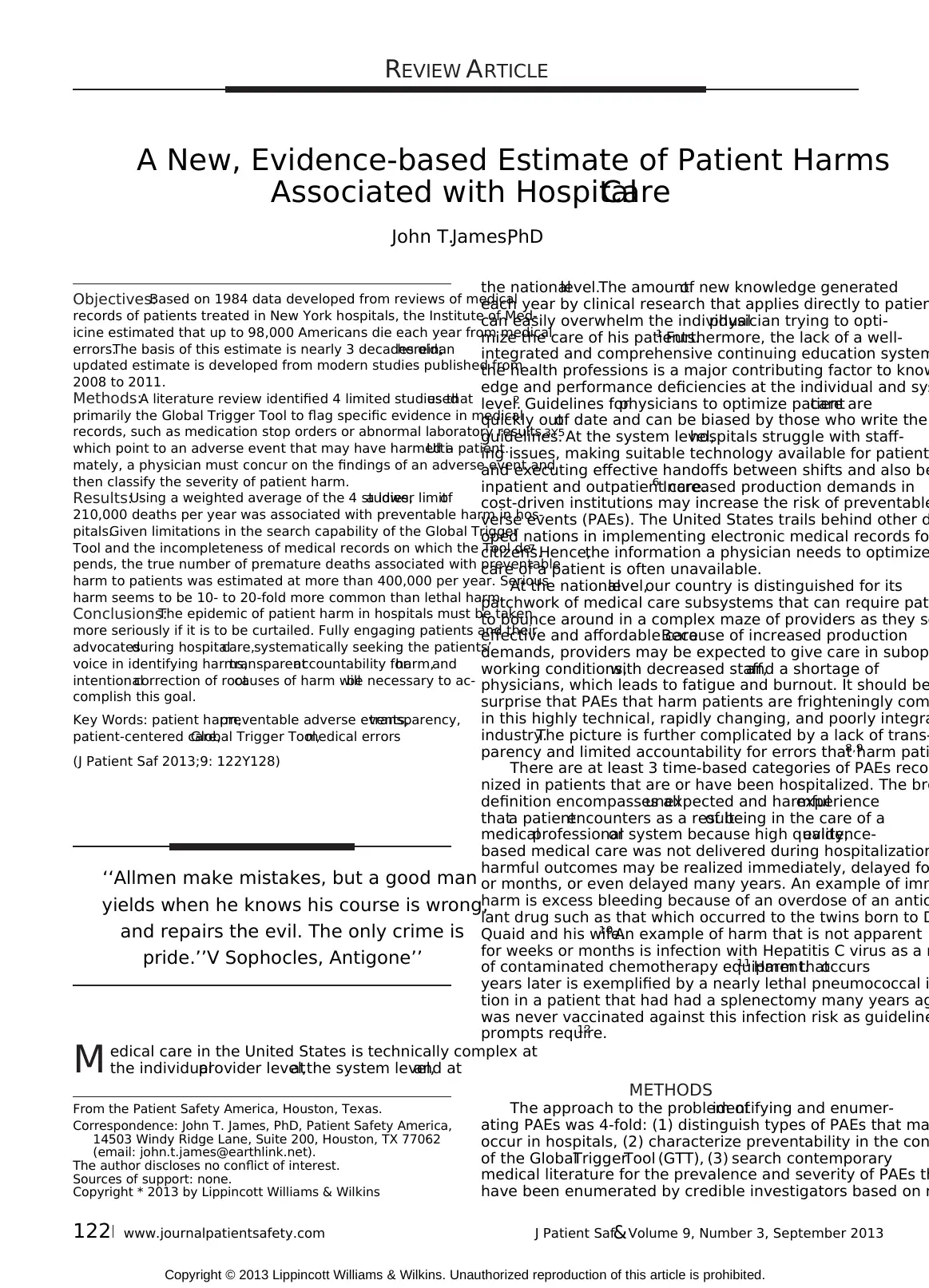

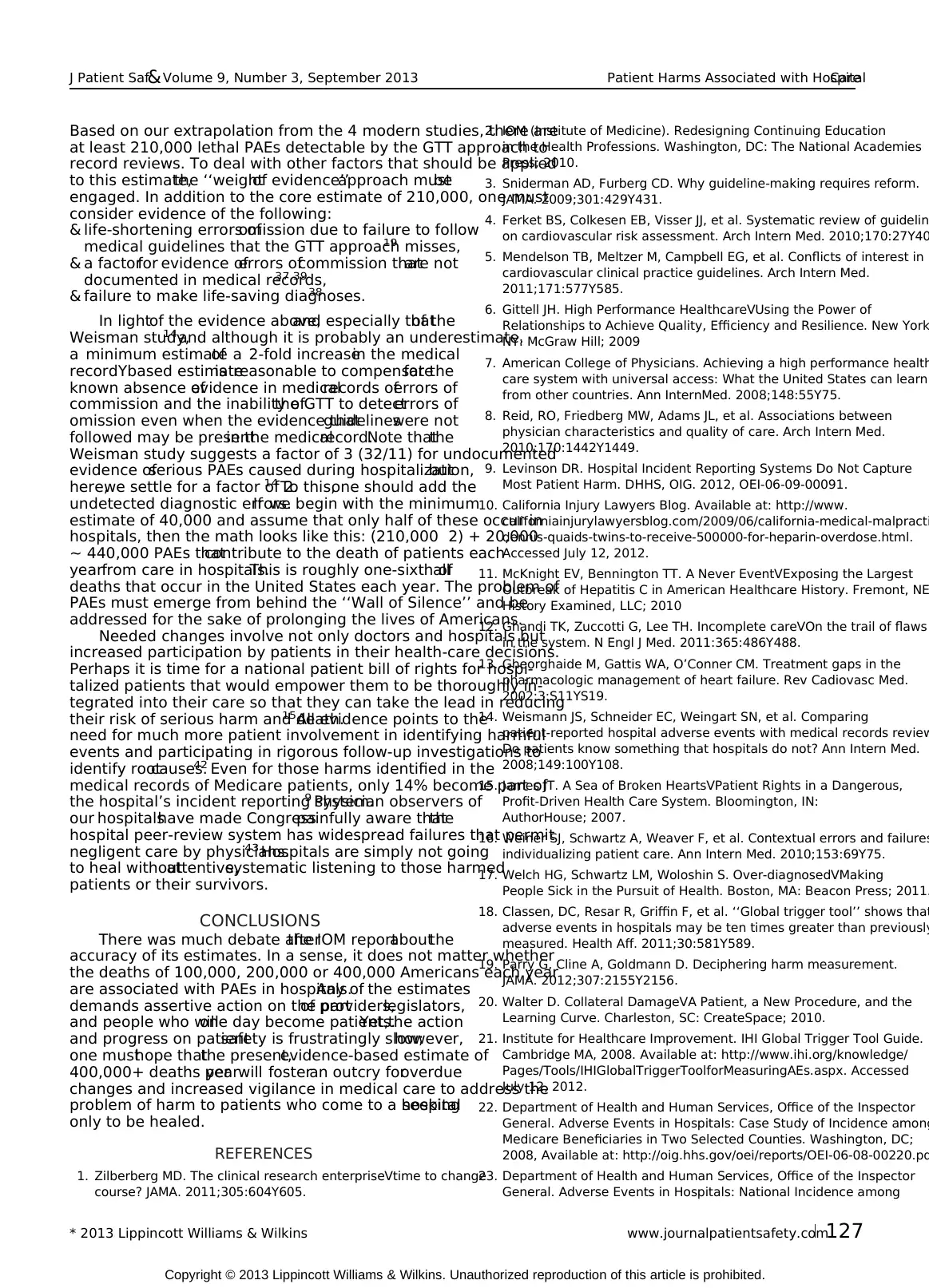

TABLE 1. Adverse Events Classified as Serious

Level of Harm Description

F Required prolonged hospital stay

G Permanent harm

H Life sustaining intervention required

I Contributing to death of patient

Adapted from the National Coordinating Council for Medication

Errors Reporting and Prevention.

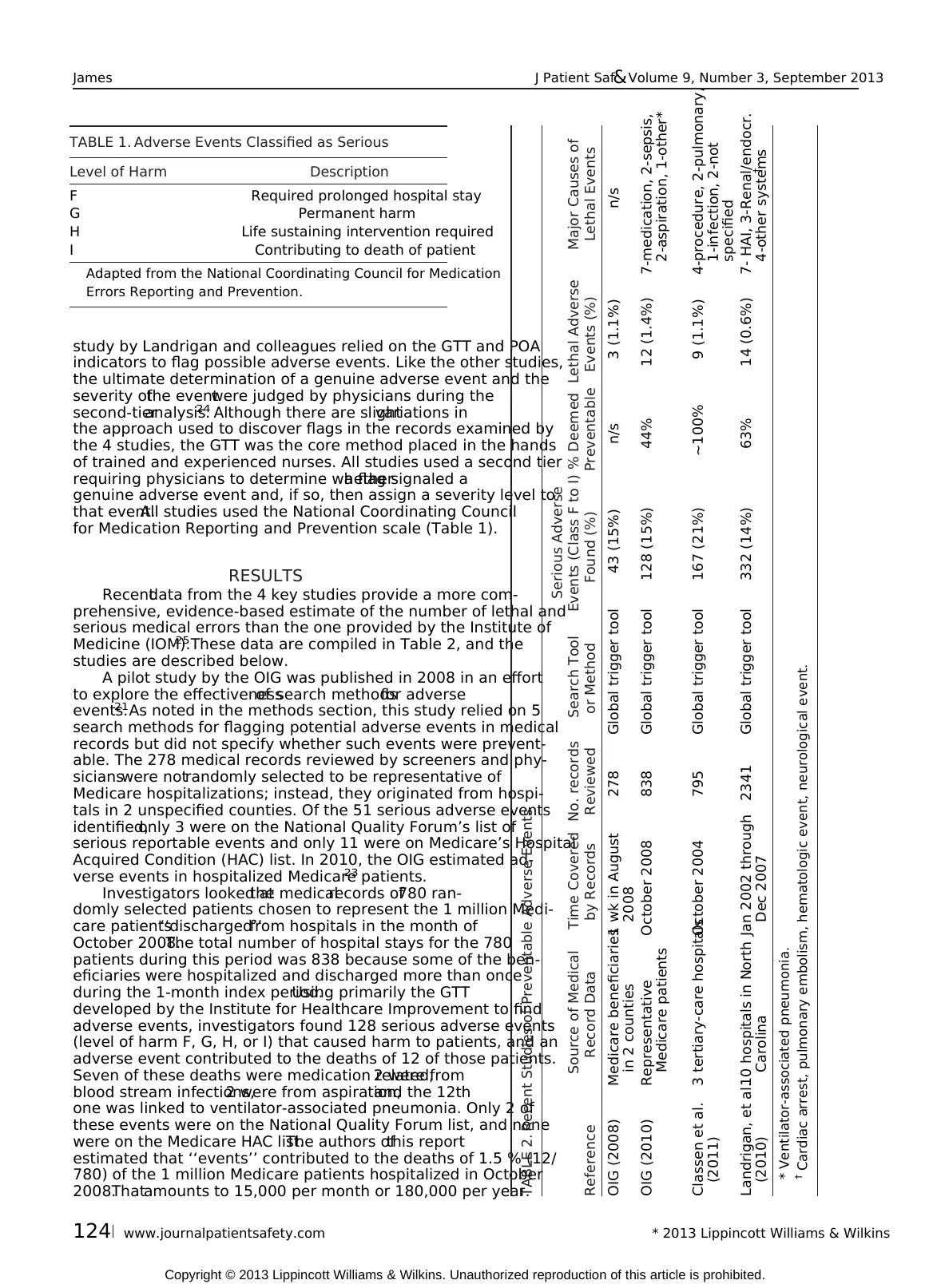

TABLE 2. Recent Studies of Preventable Adverse Events

Reference

Source of Medical

Record Data

Time Covered

by Records

No. records

Reviewed

Search Tool

or Method

Serious Adverse

Events (Class F to I)

Found (%)

% Deemed

Preventable

Lethal Adverse

Events (%)

Major Causes of

Lethal Events

OIG (2008) Medicare beneficiaries

in 2 counties

1 wk in August

2008

278 Global trigger tool 43 (15%) n/s 3 (1.1%) n/s

OIG (2010) Representative

Medicare patients

October 2008 838 Global trigger tool 128 (15%) 44% 12 (1.4%) 7-medication, 2-sepsis,

2-aspiration, 1-other*

Classen et al.

(2011)

3 tertiary-care hospitalsOctober 2004 795 Global trigger tool 167 (21%) ~100% 9 (1.1%) 4-procedure, 2-pulmonary,

1-infection, 2-not

specified

Landrigan, et al.

(2010)

10 hospitals in North

Carolina

Jan 2002 through

Dec 2007

2341 Global trigger tool 332 (14%) 63% 14 (0.6%) 7- HAI, 3-Renal/endocr.

4-other systems†

* Ventilator-associated pneumonia.

† Cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolism, hematologic event, neurological event.

James J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013

124 www.journalpatientsafety.com * 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

indicators to flag possible adverse events. Like the other studies,

the ultimate determination of a genuine adverse event and the

severity ofthe eventwere judged by physicians during the

second-tieranalysis.24 Although there are slightvariations in

the approach used to discover flags in the records examined by

the 4 studies, the GTT was the core method placed in the hands

of trained and experienced nurses. All studies used a second tier

requiring physicians to determine whethera flag signaled a

genuine adverse event and, if so, then assign a severity level to

that event.All studies used the National Coordinating Council

for Medication Reporting and Prevention scale (Table 1).

RESULTS

Recentdata from the 4 key studies provide a more com-

prehensive, evidence-based estimate of the number of lethal and

serious medical errors than the one provided by the Institute of

Medicine (IOM).25These data are compiled in Table 2, and the

studies are described below.

A pilot study by the OIG was published in 2008 in an effort

to explore the effectivenessof search methodsfor adverse

events.21As noted in the methods section, this study relied on 5

search methods for flagging potential adverse events in medical

records but did not specify whether such events were prevent-

able. The 278 medical records reviewed by screeners and phy-

sicianswere notrandomly selected to be representative of

Medicare hospitalizations; instead, they originated from hospi-

tals in 2 unspecified counties. Of the 51 serious adverse events

identified,only 3 were on the National Quality Forum’s list of

serious reportable events and only 11 were on Medicare’s Hospital

Acquired Condition (HAC) list. In 2010, the OIG estimated ad-

verse events in hospitalized Medicare patients.23

Investigators looked atthe medicalrecords of780 ran-

domly selected patients chosen to represent the 1 million Medi-

care patients‘‘discharged’’from hospitals in the month of

October 2008.The total number of hospital stays for the 780

patients during this period was 838 because some of the ben-

eficiaries were hospitalized and discharged more than once

during the 1-month index period.Using primarily the GTT

developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to find

adverse events, investigators found 128 serious adverse events

(level of harm F, G, H, or I) that caused harm to patients, and an

adverse event contributed to the deaths of 12 of those patients.

Seven of these deaths were medication related,2 were from

blood stream infections,2 were from aspiration,and the 12th

one was linked to ventilator-associated pneumonia. Only 2 of

these events were on the National Quality Forum list, and none

were on the Medicare HAC list.The authors ofthis report

estimated that ‘‘events’’ contributed to the deaths of 1.5 % (12/

780) of the 1 million Medicare patients hospitalized in October

2008.Thatamounts to 15,000 per month or 180,000 per year.

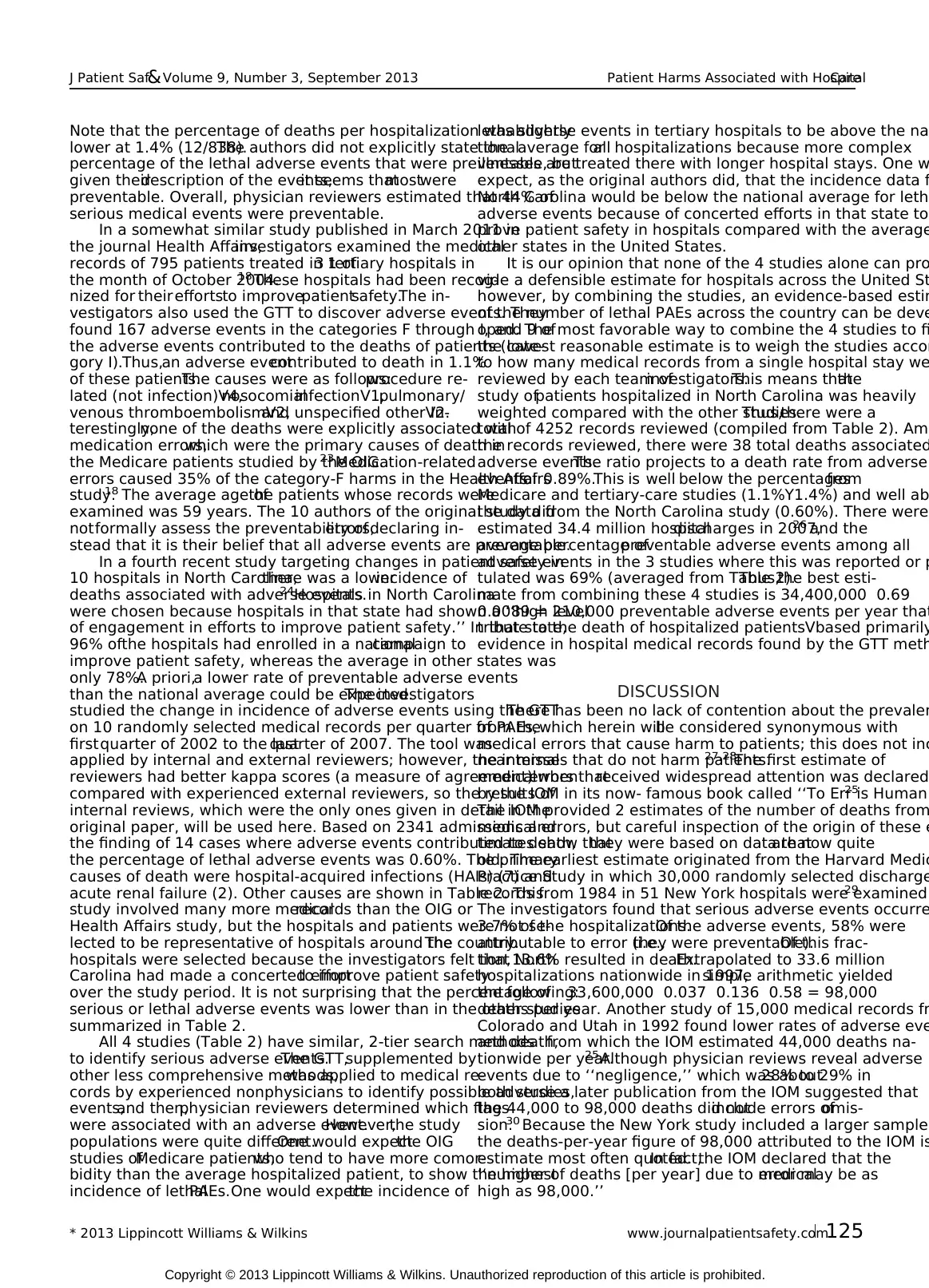

TABLE 1. Adverse Events Classified as Serious

Level of Harm Description

F Required prolonged hospital stay

G Permanent harm

H Life sustaining intervention required

I Contributing to death of patient

Adapted from the National Coordinating Council for Medication

Errors Reporting and Prevention.

TABLE 2. Recent Studies of Preventable Adverse Events

Reference

Source of Medical

Record Data

Time Covered

by Records

No. records

Reviewed

Search Tool

or Method

Serious Adverse

Events (Class F to I)

Found (%)

% Deemed

Preventable

Lethal Adverse

Events (%)

Major Causes of

Lethal Events

OIG (2008) Medicare beneficiaries

in 2 counties

1 wk in August

2008

278 Global trigger tool 43 (15%) n/s 3 (1.1%) n/s

OIG (2010) Representative

Medicare patients

October 2008 838 Global trigger tool 128 (15%) 44% 12 (1.4%) 7-medication, 2-sepsis,

2-aspiration, 1-other*

Classen et al.

(2011)

3 tertiary-care hospitalsOctober 2004 795 Global trigger tool 167 (21%) ~100% 9 (1.1%) 4-procedure, 2-pulmonary,

1-infection, 2-not

specified

Landrigan, et al.

(2010)

10 hospitals in North

Carolina

Jan 2002 through

Dec 2007

2341 Global trigger tool 332 (14%) 63% 14 (0.6%) 7- HAI, 3-Renal/endocr.

4-other systems†

* Ventilator-associated pneumonia.

† Cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolism, hematologic event, neurological event.

James J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013

124 www.journalpatientsafety.com * 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Note that the percentage of deaths per hospitalization was slightly

lower at 1.4% (12/838).The authors did not explicitly state the

percentage of the lethal adverse events that were preventable, but

given theirdescription of the events,it seems thatmostwere

preventable. Overall, physician reviewers estimated that 44% of

serious medical events were preventable.

In a somewhat similar study published in March 2011 in

the journal Health Affairs,investigators examined the medical

records of 795 patients treated in 1 of3 tertiary hospitals in

the month of October 2004.18 These hospitals had been recog-

nized for theireffortsto improvepatientsafety.The in-

vestigators also used the GTT to discover adverse events. They

found 167 adverse events in the categories F through I, and 9 of

the adverse events contributed to the deaths of patients (cate-

gory I).Thus,an adverse eventcontributed to death in 1.1%

of these patients.The causes were as follows:procedure re-

lated (not infection)V4,nosocomialinfectionV1,pulmonary/

venous thromboembolismV2,and unspecified otherV2.In-

terestingly,none of the deaths were explicitly associated with

medication errors,which were the primary causes of death in

the Medicare patients studied by the OIG.23 Medication-related

errors caused 35% of the category-F harms in the Health Affairs

study.18 The average age ofthe patients whose records were

examined was 59 years. The 10 authors of the original study did

notformally assess the preventability oferrors,declaring in-

stead that it is their belief that all adverse events are preventable.

In a fourth recent study targeting changes in patient safety in

10 hospitals in North Carolina,there was a lowerincidence of

deaths associated with adverse events.24Hospitals in North Carolina

were chosen because hospitals in that state had shown a ‘‘high level

of engagement in efforts to improve patient safety.’’ In that state,

96% ofthe hospitals had enrolled in a nationalcampaign to

improve patient safety, whereas the average in other states was

only 78%.A priori,a lower rate of preventable adverse events

than the national average could be expected.The investigators

studied the change in incidence of adverse events using the GTT

on 10 randomly selected medical records per quarter from the

firstquarter of 2002 to the lastquarter of 2007. The tool was

applied by internal and external reviewers; however, the internal

reviewers had better kappa scores (a measure of agreement) when

compared with experienced external reviewers, so the results of

internal reviews, which were the only ones given in detail in the

original paper, will be used here. Based on 2341 admissions and

the finding of 14 cases where adverse events contributed to death,

the percentage of lethal adverse events was 0.60%. The primary

causes of death were hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) (7) and

acute renal failure (2). Other causes are shown in Table 2. This

study involved many more medicalrecords than the OIG or

Health Affairs study, but the hospitals and patients were not se-

lected to be representative of hospitals around the country.The

hospitals were selected because the investigators felt that North

Carolina had made a concerted effortto improve patient safety

over the study period. It is not surprising that the percentage of

serious or lethal adverse events was lower than in the other studies

summarized in Table 2.

All 4 studies (Table 2) have similar, 2-tier search methods

to identify serious adverse events.The GTT,supplemented by

other less comprehensive methods,was applied to medical re-

cords by experienced nonphysicians to identify possible adverse

events,and then,physician reviewers determined which flags

were associated with an adverse event.However,the study

populations were quite different.One would expectthe OIG

studies ofMedicare patients,who tend to have more comor-

bidity than the average hospitalized patient, to show the highest

incidence of lethalPAEs.One would expectthe incidence of

lethaladverse events in tertiary hospitals to be above the na

tionalaverage forall hospitalizations because more complex

illnesses are treated there with longer hospital stays. One w

expect, as the original authors did, that the incidence data f

North Carolina would be below the national average for leth

adverse events because of concerted efforts in that state to

prove patient safety in hospitals compared with the average

other states in the United States.

It is our opinion that none of the 4 studies alone can pro

vide a defensible estimate for hospitals across the United St

however, by combining the studies, an evidence-based estim

of the number of lethal PAEs across the country can be deve

oped. The most favorable way to combine the 4 studies to fi

the lowest reasonable estimate is to weigh the studies accor

to how many medical records from a single hospital stay we

reviewed by each team ofinvestigators.This means thatthe

study ofpatients hospitalized in North Carolina was heavily

weighted compared with the other studies.Thus,there were a

total of 4252 records reviewed (compiled from Table 2). Amo

the records reviewed, there were 38 total deaths associated

adverse events.The ratio projects to a death rate from adverse

eventsof 0.89%.This is well below the percentagesfrom

Medicare and tertiary-care studies (1.1%Y1.4%) and well ab

the data from the North Carolina study (0.60%). There were

estimated 34.4 million hospitaldischarges in 2007,26 and the

average percentage ofpreventable adverse events among all

adverse events in the 3 studies where this was reported or p

tulated was 69% (averaged from Table 2).Thus,the best esti-

mate from combining these 4 studies is 34,400,000 0.69

0.0089 = 210,000 preventable adverse events per year that

tribute to the death of hospitalized patientsVbased primarily

evidence in hospital medical records found by the GTT meth

DISCUSSION

There has been no lack of contention about the prevalen

of PAEs,which herein willbe considered synonymous with

medical errors that cause harm to patients; this does not inc

near misses that do not harm patients.27,28

The first estimate of

medicalerrors thatreceived widespread attention was declared

by the IOM in its now- famous book called ‘‘To Err is Human.25

The IOM provided 2 estimates of the number of deaths from

medical errors, but careful inspection of the origin of these e

timates show thatthey were based on data thatare now quite

old. The earliest estimate originated from the Harvard Medic

Practice Study in which 30,000 randomly selected discharge

records from 1984 in 51 New York hospitals were examined.29

The investigators found that serious adverse events occurre

3.7% of the hospitalizations.Of the adverse events, 58% were

attributable to error (i.e.,they were preventable).Of this frac-

tion,13.6% resulted in death.Extrapolated to 33.6 million

hospitalizations nationwide in 1997,simple arithmetic yielded

the following:33,600,000 0.037 0.136 0.58 = 98,000

deaths per year. Another study of 15,000 medical records fr

Colorado and Utah in 1992 found lower rates of adverse eve

and death,from which the IOM estimated 44,000 deaths na-

tionwide per year.25 Although physician reviews reveal adverse

events due to ‘‘negligence,’’ which was about28% to 29% in

both studies,a later publication from the IOM suggested that

the 44,000 to 98,000 deaths did notinclude errors ofomis-

sion.30 Because the New York study included a larger sample,

the deaths-per-year figure of 98,000 attributed to the IOM is

estimate most often quoted.In fact,the IOM declared that the

‘‘number of deaths [per year] due to medicalerror may be as

high as 98,000.’’

J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013 Patient Harms Associated with HospitalCare

* 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins www.journalpatientsafety.com125

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

lower at 1.4% (12/838).The authors did not explicitly state the

percentage of the lethal adverse events that were preventable, but

given theirdescription of the events,it seems thatmostwere

preventable. Overall, physician reviewers estimated that 44% of

serious medical events were preventable.

In a somewhat similar study published in March 2011 in

the journal Health Affairs,investigators examined the medical

records of 795 patients treated in 1 of3 tertiary hospitals in

the month of October 2004.18 These hospitals had been recog-

nized for theireffortsto improvepatientsafety.The in-

vestigators also used the GTT to discover adverse events. They

found 167 adverse events in the categories F through I, and 9 of

the adverse events contributed to the deaths of patients (cate-

gory I).Thus,an adverse eventcontributed to death in 1.1%

of these patients.The causes were as follows:procedure re-

lated (not infection)V4,nosocomialinfectionV1,pulmonary/

venous thromboembolismV2,and unspecified otherV2.In-

terestingly,none of the deaths were explicitly associated with

medication errors,which were the primary causes of death in

the Medicare patients studied by the OIG.23 Medication-related

errors caused 35% of the category-F harms in the Health Affairs

study.18 The average age ofthe patients whose records were

examined was 59 years. The 10 authors of the original study did

notformally assess the preventability oferrors,declaring in-

stead that it is their belief that all adverse events are preventable.

In a fourth recent study targeting changes in patient safety in

10 hospitals in North Carolina,there was a lowerincidence of

deaths associated with adverse events.24Hospitals in North Carolina

were chosen because hospitals in that state had shown a ‘‘high level

of engagement in efforts to improve patient safety.’’ In that state,

96% ofthe hospitals had enrolled in a nationalcampaign to

improve patient safety, whereas the average in other states was

only 78%.A priori,a lower rate of preventable adverse events

than the national average could be expected.The investigators

studied the change in incidence of adverse events using the GTT

on 10 randomly selected medical records per quarter from the

firstquarter of 2002 to the lastquarter of 2007. The tool was

applied by internal and external reviewers; however, the internal

reviewers had better kappa scores (a measure of agreement) when

compared with experienced external reviewers, so the results of

internal reviews, which were the only ones given in detail in the

original paper, will be used here. Based on 2341 admissions and

the finding of 14 cases where adverse events contributed to death,

the percentage of lethal adverse events was 0.60%. The primary

causes of death were hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) (7) and

acute renal failure (2). Other causes are shown in Table 2. This

study involved many more medicalrecords than the OIG or

Health Affairs study, but the hospitals and patients were not se-

lected to be representative of hospitals around the country.The

hospitals were selected because the investigators felt that North

Carolina had made a concerted effortto improve patient safety

over the study period. It is not surprising that the percentage of

serious or lethal adverse events was lower than in the other studies

summarized in Table 2.

All 4 studies (Table 2) have similar, 2-tier search methods

to identify serious adverse events.The GTT,supplemented by

other less comprehensive methods,was applied to medical re-

cords by experienced nonphysicians to identify possible adverse

events,and then,physician reviewers determined which flags

were associated with an adverse event.However,the study

populations were quite different.One would expectthe OIG

studies ofMedicare patients,who tend to have more comor-

bidity than the average hospitalized patient, to show the highest

incidence of lethalPAEs.One would expectthe incidence of

lethaladverse events in tertiary hospitals to be above the na

tionalaverage forall hospitalizations because more complex

illnesses are treated there with longer hospital stays. One w

expect, as the original authors did, that the incidence data f

North Carolina would be below the national average for leth

adverse events because of concerted efforts in that state to

prove patient safety in hospitals compared with the average

other states in the United States.

It is our opinion that none of the 4 studies alone can pro

vide a defensible estimate for hospitals across the United St

however, by combining the studies, an evidence-based estim

of the number of lethal PAEs across the country can be deve

oped. The most favorable way to combine the 4 studies to fi

the lowest reasonable estimate is to weigh the studies accor

to how many medical records from a single hospital stay we

reviewed by each team ofinvestigators.This means thatthe

study ofpatients hospitalized in North Carolina was heavily

weighted compared with the other studies.Thus,there were a

total of 4252 records reviewed (compiled from Table 2). Amo

the records reviewed, there were 38 total deaths associated

adverse events.The ratio projects to a death rate from adverse

eventsof 0.89%.This is well below the percentagesfrom

Medicare and tertiary-care studies (1.1%Y1.4%) and well ab

the data from the North Carolina study (0.60%). There were

estimated 34.4 million hospitaldischarges in 2007,26 and the

average percentage ofpreventable adverse events among all

adverse events in the 3 studies where this was reported or p

tulated was 69% (averaged from Table 2).Thus,the best esti-

mate from combining these 4 studies is 34,400,000 0.69

0.0089 = 210,000 preventable adverse events per year that

tribute to the death of hospitalized patientsVbased primarily

evidence in hospital medical records found by the GTT meth

DISCUSSION

There has been no lack of contention about the prevalen

of PAEs,which herein willbe considered synonymous with

medical errors that cause harm to patients; this does not inc

near misses that do not harm patients.27,28

The first estimate of

medicalerrors thatreceived widespread attention was declared

by the IOM in its now- famous book called ‘‘To Err is Human.25

The IOM provided 2 estimates of the number of deaths from

medical errors, but careful inspection of the origin of these e

timates show thatthey were based on data thatare now quite

old. The earliest estimate originated from the Harvard Medic

Practice Study in which 30,000 randomly selected discharge

records from 1984 in 51 New York hospitals were examined.29

The investigators found that serious adverse events occurre

3.7% of the hospitalizations.Of the adverse events, 58% were

attributable to error (i.e.,they were preventable).Of this frac-

tion,13.6% resulted in death.Extrapolated to 33.6 million

hospitalizations nationwide in 1997,simple arithmetic yielded

the following:33,600,000 0.037 0.136 0.58 = 98,000

deaths per year. Another study of 15,000 medical records fr

Colorado and Utah in 1992 found lower rates of adverse eve

and death,from which the IOM estimated 44,000 deaths na-

tionwide per year.25 Although physician reviews reveal adverse

events due to ‘‘negligence,’’ which was about28% to 29% in

both studies,a later publication from the IOM suggested that

the 44,000 to 98,000 deaths did notinclude errors ofomis-

sion.30 Because the New York study included a larger sample,

the deaths-per-year figure of 98,000 attributed to the IOM is

estimate most often quoted.In fact,the IOM declared that the

‘‘number of deaths [per year] due to medicalerror may be as

high as 98,000.’’

J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013 Patient Harms Associated with HospitalCare

* 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins www.journalpatientsafety.com125

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Why is the present estimate of the number of lethal PAEs

so much higherthan the highestestimate (98,000)from the

IOM? It is likely that the bar for identification of a PAE in the

New York/IOM study was much higher than in the 4 modern

studies and that the GTT is better able to identify adverse events

than general reviews by physicians, which was the method used

in the older studies cited by the IOM.19 It is also possible that

the frequency of preventable and lethalpatientharms has in-

creased from 1984 to 2002Y2008 because ofthe increased

complexity of medicalpractice and technology,the increased

incidence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, overuse/misuse of med-

ications,an aging population, and the movement of the medical

industry toward higherproductivity and expensive technology,

which encourages rapid patient flow and overuse of risky, inva-

sive, revenue-generating procedures.31Y33

Several observations aboutthe 4 varied studies described

in the ‘‘Results’’ section are in order. Although they used varied

selection criteria for the patientpopulations and hospitals,the

results in terms of the portion of adverse events found and the

portion ofdeath-associated events are notremarkably varied.

The percentage of serious adverse events (class F to I) ranged

from 14% to 21%,and the percentage of death-associated ad-

verse events (class I) varied from 0.60% to 1.4%.The result

found in records from North Carolina hospitals (0.60%) is likely

to be below the national average because patient safety efforts in

thatstate have been more intense when compared with other

states. The results from the other studies would be expected to

be above the national average because of the age of the patients

and seriousness of the illnesses. This dispersion of percentages

makes sense and gives one confidence that the estimate of the

average number of preventable, lethal adverse events based on

hospital medical records screened by the GTT approach is rep-

resentative of the nation as a whole. The portion of serious ad-

verse eventsthatwere notlethal(classF, G, and H) were

roughly 10- to 20-fold larger than the portion of lethalPAEs.

This leads to a rough estimate of 2 to 4 million serious,PAEs

per year that would be discoverable in medical records using the

GTT approach.

There are important limitations to the 4 modern studies that

mustbe considered.Premature deaths as a resultof medical

errors may occur many years after the hospital stay because the

patient’s care was notoptimalor did notfollow guidelines.12

Furthermore,lethal PAEs can been missed by the GTT and by

physician reviews. The GTT does not detect diagnostic errors or

errors of omission,especially those involving failure to follow

guidelines.19 Lethaldiagnostic errors have been estimated to

affect 40,000 to 80,000 people per year including outpatients.34

Physicians have been indefensibly slow to adopt guidelines that

would potentially preventpremature deathsor harm.35 One

egregious example is the estimated 100,000 heartfailure pa-

tients that died prematurely each year in the late 1990s because

they did notreceive beta-blockers.13 The efficacy ofbeta-

blockers was established by a study published in the JAMA

in 1982.36

The 4 modern studies also rely heavily on information in

medicalrecords.One study ofmedicalrecords showed that

quality scores of607 randomly selected medicalrecords on

cardiac patients treated in 219 hospitals from January 2004 to

June 2005 averaged 12.5/20 points, which suggests rather poor

medical record keeping.37 The quality scores were determined

based on the medical records including cardiac history, perfor-

mance and cognition levels, current medications and medication

allergies,differentialdiagnosis,and planned use of evidence-

based medicine.Hospitalswith low-scoring records(0Y10

points) had a 40% higher in-hospital death rate than those that

scored high (15Y20 points). Furthermore, the larger OIG stu

noted that‘‘To the extentthatthe study did notidentify an

event, it was likely because the three screening methods fa

to flag the case for physicians review or because document

in the medical records was incomplete.’’23

A few years afterthe seminalpublication by the IOM,

another IOM panel recognized the limitations of using medic

records provided by medicalinstitutions as the basis for iden-

tifying medical errors. When an adverse event is alleged an

evaluation is undertaken,the ‘‘sentineleffectcan significantly

alter the data that are recorded.’’30There are anecdotal accounts

of data altering or omission of critical data when mistakes a

alleged;however,to our knowledge,scientific studies of this

phenomenon have been lacking until recently.

In a study thatbroke pastthe wallof silence aboutdis-

covery of medicalerrors thatwere missing from medicalre-

cords, Weissman and colleagues found that 6 to 12 months

their discharge, patients could recall 3 times as many seriou

preventable adverse events as were reflected in their medic

records.14 This study involved review of 998 medical records

of patients hospitalized in Massachusetts for medicalor sur-

gical treatment from April to October 2003. Record reviews

specially trained nursesand doctorsidentified 11 serious

PAEs from the records.The method was one adapted from

the Harvard Medical Practice Study, which is the method us

by the core result in the report from the IOM asserting up to

98,000 deaths per year occur from medical errors.25 However,

interviews with patients identified 21 additional serious PAE

thatwere notdocumented in the medicalrecords.Of the

21 undiscovered, serious PAEs,12 occurred predischarge and

9 occurred postdischarge.The predischarge serious PAEs in-

cluded the following: adverse drug events (3), nerve or vess

injury orwrong operation (4),deep venous thrombosis (2),

hospitalacquired infection (2),and postoperative respiratory

distress (1). The serious PAEs postdischarge included the fo

lowing: wound infection (6), deep venous thrombosis (1), op

erative wound dehiscence (1),and operative organ injury (1).

Even in this study,the investigators found only those errors

that patients were aware had happened. There certainly ma

more serious errors thatwentundocumented and were un-

known to patients. Weismann’s finding that evidence of ma

serious adverse events is notapparentin medicalrecords is

reinforced by some olderstudies.For example,it has been

pointed out that some medical errors are not known by clini

cians and only come to lightduring autopsies,which have

found misdiagnoses in 20% to 40% of cases.38 ‘‘Aggressive’’

searches foradverse drug events and prompted self-reports

from clinicians have shown a much higherrate ofadverse

drug events than are evident in the medical records.39 A com-

parison of direct observation for medication errors with revi

of documentation in medicalrecordsin 36 hospitalsand

skilled-nursing facilities found that far more errors were fou

by direct observation than by inspection of medical records40

A recent national survey showed that physicians often r

fuse to report a serious adverse event to anyone in authorit41

In the case of cardiologists,the highest nonreporting group of

the specialtiesstudied,nearly two-thirdsof the respondents

admitted thatthey had recently refused to reportat leastone

serious medical error, of which they had first-hand knowled

to anyone in authority.It is reasonable to suspectthatclear

evidence of such unreported medical errors often did not fin

their way into the medicalrecords of the patients who were

harmed.

The bottom line on total, lethal PAEs as a result of care

hospitals cannotbe estimated in a statistically rigorous way.

James J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013

126 www.journalpatientsafety.com * 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

so much higherthan the highestestimate (98,000)from the

IOM? It is likely that the bar for identification of a PAE in the

New York/IOM study was much higher than in the 4 modern

studies and that the GTT is better able to identify adverse events

than general reviews by physicians, which was the method used

in the older studies cited by the IOM.19 It is also possible that

the frequency of preventable and lethalpatientharms has in-

creased from 1984 to 2002Y2008 because ofthe increased

complexity of medicalpractice and technology,the increased

incidence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, overuse/misuse of med-

ications,an aging population, and the movement of the medical

industry toward higherproductivity and expensive technology,

which encourages rapid patient flow and overuse of risky, inva-

sive, revenue-generating procedures.31Y33

Several observations aboutthe 4 varied studies described

in the ‘‘Results’’ section are in order. Although they used varied

selection criteria for the patientpopulations and hospitals,the

results in terms of the portion of adverse events found and the

portion ofdeath-associated events are notremarkably varied.

The percentage of serious adverse events (class F to I) ranged

from 14% to 21%,and the percentage of death-associated ad-

verse events (class I) varied from 0.60% to 1.4%.The result

found in records from North Carolina hospitals (0.60%) is likely

to be below the national average because patient safety efforts in

thatstate have been more intense when compared with other

states. The results from the other studies would be expected to

be above the national average because of the age of the patients

and seriousness of the illnesses. This dispersion of percentages

makes sense and gives one confidence that the estimate of the

average number of preventable, lethal adverse events based on

hospital medical records screened by the GTT approach is rep-

resentative of the nation as a whole. The portion of serious ad-

verse eventsthatwere notlethal(classF, G, and H) were

roughly 10- to 20-fold larger than the portion of lethalPAEs.

This leads to a rough estimate of 2 to 4 million serious,PAEs

per year that would be discoverable in medical records using the

GTT approach.

There are important limitations to the 4 modern studies that

mustbe considered.Premature deaths as a resultof medical

errors may occur many years after the hospital stay because the

patient’s care was notoptimalor did notfollow guidelines.12

Furthermore,lethal PAEs can been missed by the GTT and by

physician reviews. The GTT does not detect diagnostic errors or

errors of omission,especially those involving failure to follow

guidelines.19 Lethaldiagnostic errors have been estimated to

affect 40,000 to 80,000 people per year including outpatients.34

Physicians have been indefensibly slow to adopt guidelines that

would potentially preventpremature deathsor harm.35 One

egregious example is the estimated 100,000 heartfailure pa-

tients that died prematurely each year in the late 1990s because

they did notreceive beta-blockers.13 The efficacy ofbeta-

blockers was established by a study published in the JAMA

in 1982.36

The 4 modern studies also rely heavily on information in

medicalrecords.One study ofmedicalrecords showed that

quality scores of607 randomly selected medicalrecords on

cardiac patients treated in 219 hospitals from January 2004 to

June 2005 averaged 12.5/20 points, which suggests rather poor

medical record keeping.37 The quality scores were determined

based on the medical records including cardiac history, perfor-

mance and cognition levels, current medications and medication

allergies,differentialdiagnosis,and planned use of evidence-

based medicine.Hospitalswith low-scoring records(0Y10

points) had a 40% higher in-hospital death rate than those that

scored high (15Y20 points). Furthermore, the larger OIG stu

noted that‘‘To the extentthatthe study did notidentify an

event, it was likely because the three screening methods fa

to flag the case for physicians review or because document

in the medical records was incomplete.’’23

A few years afterthe seminalpublication by the IOM,

another IOM panel recognized the limitations of using medic

records provided by medicalinstitutions as the basis for iden-

tifying medical errors. When an adverse event is alleged an

evaluation is undertaken,the ‘‘sentineleffectcan significantly

alter the data that are recorded.’’30There are anecdotal accounts

of data altering or omission of critical data when mistakes a

alleged;however,to our knowledge,scientific studies of this

phenomenon have been lacking until recently.

In a study thatbroke pastthe wallof silence aboutdis-

covery of medicalerrors thatwere missing from medicalre-

cords, Weissman and colleagues found that 6 to 12 months

their discharge, patients could recall 3 times as many seriou

preventable adverse events as were reflected in their medic

records.14 This study involved review of 998 medical records

of patients hospitalized in Massachusetts for medicalor sur-

gical treatment from April to October 2003. Record reviews

specially trained nursesand doctorsidentified 11 serious

PAEs from the records.The method was one adapted from

the Harvard Medical Practice Study, which is the method us

by the core result in the report from the IOM asserting up to

98,000 deaths per year occur from medical errors.25 However,

interviews with patients identified 21 additional serious PAE

thatwere notdocumented in the medicalrecords.Of the

21 undiscovered, serious PAEs,12 occurred predischarge and

9 occurred postdischarge.The predischarge serious PAEs in-

cluded the following: adverse drug events (3), nerve or vess

injury orwrong operation (4),deep venous thrombosis (2),

hospitalacquired infection (2),and postoperative respiratory

distress (1). The serious PAEs postdischarge included the fo

lowing: wound infection (6), deep venous thrombosis (1), op

erative wound dehiscence (1),and operative organ injury (1).

Even in this study,the investigators found only those errors

that patients were aware had happened. There certainly ma

more serious errors thatwentundocumented and were un-

known to patients. Weismann’s finding that evidence of ma

serious adverse events is notapparentin medicalrecords is

reinforced by some olderstudies.For example,it has been

pointed out that some medical errors are not known by clini

cians and only come to lightduring autopsies,which have

found misdiagnoses in 20% to 40% of cases.38 ‘‘Aggressive’’

searches foradverse drug events and prompted self-reports

from clinicians have shown a much higherrate ofadverse

drug events than are evident in the medical records.39 A com-

parison of direct observation for medication errors with revi

of documentation in medicalrecordsin 36 hospitalsand

skilled-nursing facilities found that far more errors were fou

by direct observation than by inspection of medical records40

A recent national survey showed that physicians often r

fuse to report a serious adverse event to anyone in authorit41

In the case of cardiologists,the highest nonreporting group of

the specialtiesstudied,nearly two-thirdsof the respondents

admitted thatthey had recently refused to reportat leastone

serious medical error, of which they had first-hand knowled

to anyone in authority.It is reasonable to suspectthatclear

evidence of such unreported medical errors often did not fin

their way into the medicalrecords of the patients who were

harmed.

The bottom line on total, lethal PAEs as a result of care

hospitals cannotbe estimated in a statistically rigorous way.

James J Patient Saf&Volume 9, Number 3, September 2013

126 www.journalpatientsafety.com * 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Based on our extrapolation from the 4 modern studies, there are

at least 210,000 lethal PAEs detectable by the GTT approach to

record reviews. To deal with other factors that should be applied

to this estimate,the ‘‘weightof evidence’’approach mustbe

engaged. In addition to the core estimate of 210,000, one must

consider evidence of the following:

& life-shortening errors ofomission due to failure to follow

medical guidelines that the GTT approach misses,19

& a factorfor evidence oferrors ofcommission thatare not

documented in medical records,37,39

& failure to make life-saving diagnoses.38

In lightof the evidence above,and especially thatof the

Weisman study,14and although it is probably an underestimate,

a minimum estimateof a 2-fold increasein the medical

recordYbased estimateis reasonable to compensatefor the

known absence ofevidence in medicalrecords oferrors of

commission and the inability ofthe GTT to detecterrors of

omission even when the evidence thatguidelineswere not

followed may be presentin the medicalrecord.Note thatthe

Weisman study suggests a factor of 3 (32/11) for undocumented

evidence ofserious PAEs caused during hospitalization,but

here,we settle for a factor of 2.14 To this,one should add the

undetected diagnostic errors.If we begin with the minimum

estimate of 40,000 and assume that only half of these occur in

hospitals, then the math looks like this: (210,000 2) + 20,000

~ 440,000 PAEs thatcontribute to the death of patients each

yearfrom care in hospitals.This is roughly one-sixth ofall

deaths that occur in the United States each year. The problem of

PAEs must emerge from behind the ‘‘Wall of Silence’’ and be

addressed for the sake of prolonging the lives of Americans.

Needed changes involve not only doctors and hospitals but

increased participation by patients in their health-care decisions.

Perhaps it is time for a national patient bill of rights for hospi-

talized patients that would empower them to be thoroughly in-

tegrated into their care so that they can take the lead in reducing

their risk of serious harm and death.15All evidence points to the

need for much more patient involvement in identifying harmful

events and participating in rigorous follow-up investigations to

identify rootcauses.42 Even for those harms identified in the

medical records of Medicare patients, only 14% become part of

the hospital’s incident reporting system.9 Physician observers of

our hospitalshave made Congresspainfully aware thatthe

hospital peer-review system has widespread failures that permit

negligent care by physicians.43 Hospitals are simply not going

to heal withoutattentive,systematic listening to those harmed

patients or their survivors.

CONCLUSIONS

There was much debate afterthe IOM reportaboutthe

accuracy of its estimates. In a sense, it does not matter whether

the deaths of 100,000, 200,000 or 400,000 Americans each year

are associated with PAEs in hospitals.Any of the estimates

demands assertive action on the partof providers,legislators,

and people who willone day become patients.Yet,the action

and progress on patientsafety is frustratingly slow;however,

one musthope thatthe present,evidence-based estimate of

400,000+ deaths peryearwill fosteran outcry foroverdue

changes and increased vigilance in medical care to address the

problem of harm to patients who come to a hospitalseeking

only to be healed.

REFERENCES

1. Zilberberg MD. The clinical research enterpriseVtime to change

course? JAMA. 2011;305:604Y605.

2. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Redesigning Continuing Education

in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: The National Academies

Press; 2010.

3. Sniderman AD, Furberg CD. Why guideline-making requires reform.

JAMA. 2009;301:429Y431.

4. Ferket BS, Colkesen EB, Visser JJ, et al. Systematic review of guidelin

on cardiovascular risk assessment. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:27Y40

5. Mendelson TB, Meltzer M, Campbell EG, et al. Conflicts of interest in

cardiovascular clinical practice guidelines. Arch Intern Med.

2011;171:577Y585.

6. Gittell JH. High Performance HealthcareVUsing the Power of

Relationships to Achieve Quality, Efficiency and Resilience. New York

NY: McGraw Hill; 2009

7. American College of Physicians. Achieving a high performance health

care system with universal access: What the United States can learn

from other countries. Ann InternMed. 2008;148:55Y75.

8. Reid, RO, Friedberg MW, Adams JL, et al. Associations between

physician characteristics and quality of care. Arch Intern Med.

2010;170:1442Y1449.

9. Levinson DR. Hospital Incident Reporting Systems Do Not Capture

Most Patient Harm. DHHS, OIG. 2012, OEI-06-09-00091.

10. California Injury Lawyers Blog. Available at: http://www.

californiainjurylawyersblog.com/2009/06/california-medical-malpracti

dennis-quaids-twins-to-receive-500000-for-heparin-overdose.html.

Accessed July 12, 2012.

11. McKnight EV, Bennington TT. A Never EventVExposing the Largest

Outbreak of Hepatitis C in American Healthcare History. Fremont, NE