RMLE Online Research in Middle Level Education

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/09

|17

|12875

|46

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=umle20

RMLE Online

Research in Middle Level Education

ISSN: (Print) 1940-4476 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/umle20

The Intersection between 1:1 Laptop

Implementation and the Characteristics of

Effective Middle Level Schools

John M. Downes & Penny A. Bishop

To cite this article: John M. Downes & Penny A. Bishop (2015) The Intersection between 1:1

Laptop Implementation and the Characteristics of Effective Middle Level Schools, RMLE Online,

38:7, 1-16, DOI: 10.1080/19404476.2015.11462120

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2015.11462120

Published online: 25 Aug 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 843

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Citing articles: 3 View citing articles

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=umle20

RMLE Online

Research in Middle Level Education

ISSN: (Print) 1940-4476 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/umle20

The Intersection between 1:1 Laptop

Implementation and the Characteristics of

Effective Middle Level Schools

John M. Downes & Penny A. Bishop

To cite this article: John M. Downes & Penny A. Bishop (2015) The Intersection between 1:1

Laptop Implementation and the Characteristics of Effective Middle Level Schools, RMLE Online,

38:7, 1-16, DOI: 10.1080/19404476.2015.11462120

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2015.11462120

Published online: 25 Aug 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 843

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Citing articles: 3 View citing articles

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

RMLE Online— Volume 38, No. 7

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 11

David C. Virtue, Ph.D., Editor

University of South Carolina

Columbia, South Carolina

2015 • Volume 38 • Number 7 ISSN 1940-4476

The Intersection between 1:1 Laptop Implementation and the

Characteristics of Effective Middle Level Schools

John M. Downes

Penny A. Bishop

University of Vermont

Abstract

The number of middle level schools adopting 1:1

laptop programs has increased considerably during

the past decade (e.g., Lowther, Strahl, Inan, &

Bates, 2007; Storz & Hoffman, 2013; Texas Center

for Educational Research, 2009). The cornerstone

practices of the middle school concept (National

Middle School Association, 2010), therefore, often

serve as the backdrop for 1:1 implementation. The

purpose of this qualitative study was to examine the

intersection between 1:1 program implementation

and the characteristics of effective middle schools

associated with the middle school concept over a four-

year period. Through ongoing participant observation,

individual interviews, focus groups, and reviews of

digital student work and documents, we explored the

implementation of a 1:1 program by one middle school

team that also espoused the middle school concept.

We begin by providing perspectives on 1:1 programs

and on the middle school concept from research and

theoretical lenses. We then describe the qualitative

methodology we employed to conduct this study. Next,

we present an analysis of our findings, illustrating the

opportunities, tensions, and trajectories that appeared

when we examined 1:1 implementation alongside

the characteristics of effective middle level schools.

Finally, we explore the implications of these findings

for middle level educators, school leaders, and other

stakeholders as they adopt 1:1 programs in schools for

young adolescents.

Keywords: middle school concept, technology

integration, 1:1 computing

Introduction

The number of schools adopting 1:1 computing

programs in which each student has access to his/

her own Internet-enabled device has increased

considerably over the past decade (Lowther, Strahl,

Inan, & Bates, 2007; Project Tomorrow, 2014; Storz

& Hoffman, 2013; Texas Center for Educational

Research, 2009). As digital technology becomes

more affordable and as communities recognize the

importance of educational technology, proponents

assert that providing students with ubiquitous

access to computing devices holds great promise for

personalized instruction and enriched curriculum

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 11

David C. Virtue, Ph.D., Editor

University of South Carolina

Columbia, South Carolina

2015 • Volume 38 • Number 7 ISSN 1940-4476

The Intersection between 1:1 Laptop Implementation and the

Characteristics of Effective Middle Level Schools

John M. Downes

Penny A. Bishop

University of Vermont

Abstract

The number of middle level schools adopting 1:1

laptop programs has increased considerably during

the past decade (e.g., Lowther, Strahl, Inan, &

Bates, 2007; Storz & Hoffman, 2013; Texas Center

for Educational Research, 2009). The cornerstone

practices of the middle school concept (National

Middle School Association, 2010), therefore, often

serve as the backdrop for 1:1 implementation. The

purpose of this qualitative study was to examine the

intersection between 1:1 program implementation

and the characteristics of effective middle schools

associated with the middle school concept over a four-

year period. Through ongoing participant observation,

individual interviews, focus groups, and reviews of

digital student work and documents, we explored the

implementation of a 1:1 program by one middle school

team that also espoused the middle school concept.

We begin by providing perspectives on 1:1 programs

and on the middle school concept from research and

theoretical lenses. We then describe the qualitative

methodology we employed to conduct this study. Next,

we present an analysis of our findings, illustrating the

opportunities, tensions, and trajectories that appeared

when we examined 1:1 implementation alongside

the characteristics of effective middle level schools.

Finally, we explore the implications of these findings

for middle level educators, school leaders, and other

stakeholders as they adopt 1:1 programs in schools for

young adolescents.

Keywords: middle school concept, technology

integration, 1:1 computing

Introduction

The number of schools adopting 1:1 computing

programs in which each student has access to his/

her own Internet-enabled device has increased

considerably over the past decade (Lowther, Strahl,

Inan, & Bates, 2007; Project Tomorrow, 2014; Storz

& Hoffman, 2013; Texas Center for Educational

Research, 2009). As digital technology becomes

more affordable and as communities recognize the

importance of educational technology, proponents

assert that providing students with ubiquitous

access to computing devices holds great promise for

personalized instruction and enriched curriculum

RMLE Online— Volume 38, No. 7

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 2

(Hansen, 2012). One-to-one programs are particularly

abundant in the middle grades (e.g. Lowther et al.,

2007; Storz & Hoffman, 2013; Texas Center for

Educational Research, 2009), when young adolescents

demonstrate a strong affinity for technology and

reflect in their own lives the technological changes

occurring in their cultures and communities (Bishop

& Downes, 2013; Project Tomorrow, 2014).

Because 1:1 initiatives are increasingly prevalent in

the middle grades, they may often be implemented

concurrently with the middle school concept. In its

seminal position statement, This We Believe: Keys

to Educating Young Adolescents, National Middle

School Association (NMSA, now Association for

Middle Level Education [AMLE]) outlined the

middle school concept by grouping the characteristics

of effective middle level schools into three categories:

(1) Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment; (2)

Leadership and Organization; and (3) Culture and

Community (NMSA, 2010). Because the success of

implementing both the middle school concept and

1:1 initiatives hinges on similar components, such as

collaborative decision making and responsive school

structures, educators might benefit from a deeper

understanding of the ways in which characteristics

of the middle school concept intersect with the

implementation of effective 1:1 programs.

The purpose of this qualitative study was to examine

over a four-year period the intersection between 1:1

program implementation and the characteristics of

effective middle level schools. The research was

guided by the following questions:

1. How does 1:1 program implementation intersect

with the characteristics of effective middle level

schools?

2. What tensions and opportunities arise when

teachers committed to effective middle level

practices confront the challenges of 1:1?

We begin by providing perspectives on 1:1 programs

and on the middle school concept from research and

theoretical lenses. We then describe the qualitative

methodology we employed to conduct this study. Next,

we present an analysis of our findings, illustrating the

opportunities, tensions, and trajectories that appeared

when we examined 1:1 implementation alongside

the characteristics of effective middle level schools.

Finally, we explore the implications of these findings

for middle level educators, school leaders, and other

stakeholders as they adopt 1:1 programs in schools for

young adolescents.

Theoretical and Research Perspectives

Technology Integration

The use of technology in schools has both strong

support and considerable opposition. One of the great

challenges with research on 1:1 programs in particular

is that 1:1 computing, by definition, signifies the level

at which access to technology is available to students.

It declares nothing about actual educational practices.

One-to-one programs are, therefore, problematic

to study and compare, as they describe the ratio

of technology access, not necessarily how that

technology is being used to promote learning.

Because of this challenge, the research on 1:1

programs is understandably polarized. In some cases,

strong evidence of improved student outcomes exists.

For example, researchers have claimed that student

engagement has increased “dramatically in response

to the enhanced educational access and opportunities

afforded by 1:1 computing” (Bebell & Kay, 2010, p.

3). In one of the earliest and largest 1:1 initiatives,

middle level students in Maine demonstrated

increased engagement and reduced behavior referrals

(Muir, Knezek, & Christensen, 2004) as well as a

7.7% increase in attendance during the first year of

the program (Lemke & Martin, 2003). Other studies

similarly have documented improved attendance

(Lane, 2003; Texas Center for Educational Research,

2009), increased engagement (Bebell & Kay, 2010)

and decreased disciplinary problems (Bebell, 2005).

Researchers have also observed relationships between

technology use in schools and improvements in

students’ attitudes toward learning, self-efficacy,

behavior, and technology proficiency (Hsieh, Cho,

Liu, & Schallert, 2008; Shapley, Sheehan, Maloney, &

Caranikas-Walker, 2011; Storz & Hoffman, 2013).

Researchers have suggested that a link exists between

1:1 programs and student achievement, specifically

that students in 1:1 programs earn significantly higher

test scores and grades for writing, English language

arts, mathematics, and overall grade point averages

compared to students in non-1:1 programs (Lemke &

Fadel, 2006). Many others have noted similar positive

findings (Campuzano, Dynarski, Agodini, & Rall,

2009; Eden, Shamir, & Fershtman, 2011; Shapley et

al., 2011; Suhr, Hernandez, Grimes, & Warschauer,

2010; Weston & Bain, 2010).

Yet efforts to link 1:1 computing with positive

student outcomes are inconsistent and complex

(Storz & Hoffman, 2013). Hur and Oh’s (2012)

research indicated greater student engagement, but

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 2

(Hansen, 2012). One-to-one programs are particularly

abundant in the middle grades (e.g. Lowther et al.,

2007; Storz & Hoffman, 2013; Texas Center for

Educational Research, 2009), when young adolescents

demonstrate a strong affinity for technology and

reflect in their own lives the technological changes

occurring in their cultures and communities (Bishop

& Downes, 2013; Project Tomorrow, 2014).

Because 1:1 initiatives are increasingly prevalent in

the middle grades, they may often be implemented

concurrently with the middle school concept. In its

seminal position statement, This We Believe: Keys

to Educating Young Adolescents, National Middle

School Association (NMSA, now Association for

Middle Level Education [AMLE]) outlined the

middle school concept by grouping the characteristics

of effective middle level schools into three categories:

(1) Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment; (2)

Leadership and Organization; and (3) Culture and

Community (NMSA, 2010). Because the success of

implementing both the middle school concept and

1:1 initiatives hinges on similar components, such as

collaborative decision making and responsive school

structures, educators might benefit from a deeper

understanding of the ways in which characteristics

of the middle school concept intersect with the

implementation of effective 1:1 programs.

The purpose of this qualitative study was to examine

over a four-year period the intersection between 1:1

program implementation and the characteristics of

effective middle level schools. The research was

guided by the following questions:

1. How does 1:1 program implementation intersect

with the characteristics of effective middle level

schools?

2. What tensions and opportunities arise when

teachers committed to effective middle level

practices confront the challenges of 1:1?

We begin by providing perspectives on 1:1 programs

and on the middle school concept from research and

theoretical lenses. We then describe the qualitative

methodology we employed to conduct this study. Next,

we present an analysis of our findings, illustrating the

opportunities, tensions, and trajectories that appeared

when we examined 1:1 implementation alongside

the characteristics of effective middle level schools.

Finally, we explore the implications of these findings

for middle level educators, school leaders, and other

stakeholders as they adopt 1:1 programs in schools for

young adolescents.

Theoretical and Research Perspectives

Technology Integration

The use of technology in schools has both strong

support and considerable opposition. One of the great

challenges with research on 1:1 programs in particular

is that 1:1 computing, by definition, signifies the level

at which access to technology is available to students.

It declares nothing about actual educational practices.

One-to-one programs are, therefore, problematic

to study and compare, as they describe the ratio

of technology access, not necessarily how that

technology is being used to promote learning.

Because of this challenge, the research on 1:1

programs is understandably polarized. In some cases,

strong evidence of improved student outcomes exists.

For example, researchers have claimed that student

engagement has increased “dramatically in response

to the enhanced educational access and opportunities

afforded by 1:1 computing” (Bebell & Kay, 2010, p.

3). In one of the earliest and largest 1:1 initiatives,

middle level students in Maine demonstrated

increased engagement and reduced behavior referrals

(Muir, Knezek, & Christensen, 2004) as well as a

7.7% increase in attendance during the first year of

the program (Lemke & Martin, 2003). Other studies

similarly have documented improved attendance

(Lane, 2003; Texas Center for Educational Research,

2009), increased engagement (Bebell & Kay, 2010)

and decreased disciplinary problems (Bebell, 2005).

Researchers have also observed relationships between

technology use in schools and improvements in

students’ attitudes toward learning, self-efficacy,

behavior, and technology proficiency (Hsieh, Cho,

Liu, & Schallert, 2008; Shapley, Sheehan, Maloney, &

Caranikas-Walker, 2011; Storz & Hoffman, 2013).

Researchers have suggested that a link exists between

1:1 programs and student achievement, specifically

that students in 1:1 programs earn significantly higher

test scores and grades for writing, English language

arts, mathematics, and overall grade point averages

compared to students in non-1:1 programs (Lemke &

Fadel, 2006). Many others have noted similar positive

findings (Campuzano, Dynarski, Agodini, & Rall,

2009; Eden, Shamir, & Fershtman, 2011; Shapley et

al., 2011; Suhr, Hernandez, Grimes, & Warschauer,

2010; Weston & Bain, 2010).

Yet efforts to link 1:1 computing with positive

student outcomes are inconsistent and complex

(Storz & Hoffman, 2013). Hur and Oh’s (2012)

research indicated greater student engagement, but

RMLE Online— Volume 38, No. 7

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 3

no significant difference in test scores, between

students who had been given laptops and those who

had not. Moreover, as the novelty wore off, student

engagement decreased and inappropriate use of

laptops increased. Donovan, Green, and Hartley

(2010) found that increased access to laptops did not

always equate to increased student engagement and,

at times, led to an accompanying range of off-task

behaviors. Still others have identified few or neutral

effects of 1:1 programs (Shapley, Sheehan, Maloney,

& Caranikas-Walker, 2010; Weston & Bain, 2010).

Even when promising interventions are designed and

implemented, the integrity of implementation, not

surprisingly, seems to strongly affect the ultimate

impact. Further, Johnson and Maddux (2006) argued

that implementation is only one of many conditions

that must be satisfied for technology integration.

Middle School Concept

The middle grades are increasingly viewed as a

crucial time for identifying and intervening with

potential dropouts, reinforcing the idea that school

experiences during early adolescence greatly

influence later life outcomes (Balfanz et al., 2014;

Balfanz, Herzog, & Mac Iver, 2007). For decades,

AMLE has underscored the centrality of this

developmental stage for middle level school programs

and has called for them to be developmentally

responsive, challenging, empowering, and equitable

(NMSA, 1982; 1995; 2003; 2010). According to

AMLE, effective middle level schools exhibit

three categories of characteristics that, together,

constitute the middle school concept: (1) relevant and

integrative curricula taught and assessed in varied

ways (Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment);

(2) schools that are organized to foster healthy

relationships across stakeholder groups and are led

by courageous and collaborative leaders (Leadership

and Organization); and (3) school cultures that are

safe, supportive and inclusive, in which all students’

personal and social needs are addressed by caring

adults specifically prepared to work with the age

group (Culture and Community) (NMSA, 2010).

Although relatively sparse, existing research on

schools employing the middle school concept has

found promising results related to academic and

affective student outcomes (Felner et al., 1997;

Mertens & Anfara, 2006). Students in schools

demonstrating fidelity to the middle school concept,

for example, were found to academically outperform

and exhibit fewer behavior problems than their

peers in schools not implementing the middle school

concept (Felner et al., 1997). Lee and Smith (1993)

also found certain aspects of the middle school

concept to be positively associated with students’

academic achievement and engagement, and the

Center for Prevention Research and Development’s

research suggested that implementing the middle

school concept could positively impact student

achievement (Mertens & Flowers, 2006; Mertens,

Flowers, & Mulhall, 2002).

The majority of research on the middle school concept

has focused on individual aspects of the concept, such

as advisory (e.g., Niska, 2013), principal leadership

(e.g., Gale & Bishop, 2014), teacher dispositions

(e.g., Thornton, 2013), and common planning time

(e.g., Cook & Faulkner, 2010), rather than on holistic

implementation of the concept. Mertens and Anfara

(2006) argued:

In order to answer questions related to the

middle school concept and its effects on student

achievement and socio-emotional development,

middle grades practitioners, researchers, and

policymakers must move beyond this focus on

individual components and look at research that

addresses the reform as an integrated model.

To that end, we chose a holistic approach, using the

three general categories of the middle school concept

delineated in This We Believe (i.e., Curriculum,

Instruction, and Assessment; Leadership and

Organization; and Culture and Community) (NMSA,

2010) as lenses to understand relationships between

1:1 implementation and the middle school concept.

Methodology

This study was conducted over the course of four

years and used a qualitative, instrumental case

study design (Stake, 1995). We relied on participant

observation, teacher and student interviews, meeting

transcripts, and samples of student work to explore

what happens when a team that enacts the middle

school concept tackles the challenge of integrating 1:1

into teaching and learning.

Site and Participants

The site for this research was one team in a middle

school serving a town of roughly 10,000 residents

in the state of Vermont. Compared to other schools

in the same county, the school scored at or near the

bottom in reading, writing, and math on statewide

standardized tests, even accounting for the 20% of

students who receive free and reduced lunch. The

town also consistently ranked near the bottom for

average teacher salary and per pupil expenditures.

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 3

no significant difference in test scores, between

students who had been given laptops and those who

had not. Moreover, as the novelty wore off, student

engagement decreased and inappropriate use of

laptops increased. Donovan, Green, and Hartley

(2010) found that increased access to laptops did not

always equate to increased student engagement and,

at times, led to an accompanying range of off-task

behaviors. Still others have identified few or neutral

effects of 1:1 programs (Shapley, Sheehan, Maloney,

& Caranikas-Walker, 2010; Weston & Bain, 2010).

Even when promising interventions are designed and

implemented, the integrity of implementation, not

surprisingly, seems to strongly affect the ultimate

impact. Further, Johnson and Maddux (2006) argued

that implementation is only one of many conditions

that must be satisfied for technology integration.

Middle School Concept

The middle grades are increasingly viewed as a

crucial time for identifying and intervening with

potential dropouts, reinforcing the idea that school

experiences during early adolescence greatly

influence later life outcomes (Balfanz et al., 2014;

Balfanz, Herzog, & Mac Iver, 2007). For decades,

AMLE has underscored the centrality of this

developmental stage for middle level school programs

and has called for them to be developmentally

responsive, challenging, empowering, and equitable

(NMSA, 1982; 1995; 2003; 2010). According to

AMLE, effective middle level schools exhibit

three categories of characteristics that, together,

constitute the middle school concept: (1) relevant and

integrative curricula taught and assessed in varied

ways (Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment);

(2) schools that are organized to foster healthy

relationships across stakeholder groups and are led

by courageous and collaborative leaders (Leadership

and Organization); and (3) school cultures that are

safe, supportive and inclusive, in which all students’

personal and social needs are addressed by caring

adults specifically prepared to work with the age

group (Culture and Community) (NMSA, 2010).

Although relatively sparse, existing research on

schools employing the middle school concept has

found promising results related to academic and

affective student outcomes (Felner et al., 1997;

Mertens & Anfara, 2006). Students in schools

demonstrating fidelity to the middle school concept,

for example, were found to academically outperform

and exhibit fewer behavior problems than their

peers in schools not implementing the middle school

concept (Felner et al., 1997). Lee and Smith (1993)

also found certain aspects of the middle school

concept to be positively associated with students’

academic achievement and engagement, and the

Center for Prevention Research and Development’s

research suggested that implementing the middle

school concept could positively impact student

achievement (Mertens & Flowers, 2006; Mertens,

Flowers, & Mulhall, 2002).

The majority of research on the middle school concept

has focused on individual aspects of the concept, such

as advisory (e.g., Niska, 2013), principal leadership

(e.g., Gale & Bishop, 2014), teacher dispositions

(e.g., Thornton, 2013), and common planning time

(e.g., Cook & Faulkner, 2010), rather than on holistic

implementation of the concept. Mertens and Anfara

(2006) argued:

In order to answer questions related to the

middle school concept and its effects on student

achievement and socio-emotional development,

middle grades practitioners, researchers, and

policymakers must move beyond this focus on

individual components and look at research that

addresses the reform as an integrated model.

To that end, we chose a holistic approach, using the

three general categories of the middle school concept

delineated in This We Believe (i.e., Curriculum,

Instruction, and Assessment; Leadership and

Organization; and Culture and Community) (NMSA,

2010) as lenses to understand relationships between

1:1 implementation and the middle school concept.

Methodology

This study was conducted over the course of four

years and used a qualitative, instrumental case

study design (Stake, 1995). We relied on participant

observation, teacher and student interviews, meeting

transcripts, and samples of student work to explore

what happens when a team that enacts the middle

school concept tackles the challenge of integrating 1:1

into teaching and learning.

Site and Participants

The site for this research was one team in a middle

school serving a town of roughly 10,000 residents

in the state of Vermont. Compared to other schools

in the same county, the school scored at or near the

bottom in reading, writing, and math on statewide

standardized tests, even accounting for the 20% of

students who receive free and reduced lunch. The

town also consistently ranked near the bottom for

average teacher salary and per pupil expenditures.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

RMLE Online— Volume 38, No. 7

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 4

The research took place over the course of four

years and focused on a two-teacher or “partner”

team called “Engagers” (all names are pseudonyms)

serving approximately 50 seventh and eighth graders

each year. The teachers brought to their classrooms

a deep understanding of the middle school concept.

Both were licensed specifically for middle grades

teaching; both earned these licenses through a

teacher preparation program built on AMLE program

standards that was nationally accredited for middle

grades teaching. One teacher had seven years of

experience prior to the study. She was licensed to

teach English language arts and social studies in the

middle grades. The other was a new teacher who was

licensed to teach middle grades mathematics and

science and whose first year of teaching was the first

year in the study. A special educator with six years of

experience was added to the team midway through

the study, and his addition brought the total number

of educators on this team to three.

As a result of a university/private foundation

partnership, this team received extensive technology

resources and professional development to infuse

its practice with 21st century tools. In contrast to

other teams in the school, each student and teacher

on the Engagers received laptops for 1:1 wireless

computing. The team space was outfitted with media

production technology, presentation equipment, and a

wide variety of software. A Web portal served as the

program’s Web presence and as a central location for

curriculum resources. The team teachers were chosen

because of their commitment to using technology

within an integrative curriculum that emphasized

individualization, choice, and project-based learning.

The teachers were free to pursue any learning

objectives consistent with these commitments and

their appreciation for the needs and capacities of

young adolescents. There were no explicit standards

or objectives added to those already in place across

the school. One of the team teachers described the

purpose of the project: “I guess I feel like it’s adding

the 21st century learner to what is already good

middle school, middle level practice.”

The teachers participated in long term, embedded

professional development focused on integrating

technology in meaningful ways. A coach provided

by the university offered modeling, support, and

mentoring twice weekly through the first two years

of implementation. The coach came to the project

with 10 years of experience providing professional

development focused on the middle school concept

and on the integration of technology across the

curriculum and in classrooms with ready access to

personal computers and mobile technologies.

Data Collection

The university coach acted as an embedded

researcher who engaged in participant observation,

recording field notes twice weekly during the first

two years of the program and twice monthly for the

latter two years. Teachers and students participated in

formal interviews and focus groups twice per year for

these four years, averaging approximately one hour

per session. Further, informal interviews, reviews

of school and district documents, and examinations

of digital data were ongoing throughout the four

years. Digital data played a particularly important

role as much of the students’ work was in this

form, including photo stories, digital movies, blogs,

podcasts, and the team’s Web portal.

Data Analysis

We used NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software

package, to analyze the digital data, interview and

focus group transcriptions, and field notes. This

tool enabled rich analysis of the large volume of

data generated over four years. We used NVivo to

conduct open and axial coding (Strauss & Corbin,

1998) and to identify codes and categories across the

multiple data sets to classify emerging patterns. We

then created an indexing system to identify themes

within and across data sets (Patton, 2002). We

aligned the pertinent findings with three categories

of characteristics associated with effective middle

level schools (NMSA, 2010). Finally, we examined

the themes for trustworthiness in light of related

literature, triangulation across data types, and

member-checking through subsequent interviews

and consultations with participants and colleagues

(Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. A qualitative

methodology was appropriate for the descriptive and

analytical purposes of this research, but the findings

should not be generalized to other populations or

settings. For example, the study occurred in a rural

location with a predominantly White population.

Because the sample reflected a relatively low level of

racial/ethnic diversity, one might anticipate different

themes and issues arising from urban or diverse

settings. Further, the presence and participation of the

researchers at the site may have affected participants’

actions and responses. The rapport researchers

developed with participants over the course of four

years may have helped alleviate some of this effect, yet

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 4

The research took place over the course of four

years and focused on a two-teacher or “partner”

team called “Engagers” (all names are pseudonyms)

serving approximately 50 seventh and eighth graders

each year. The teachers brought to their classrooms

a deep understanding of the middle school concept.

Both were licensed specifically for middle grades

teaching; both earned these licenses through a

teacher preparation program built on AMLE program

standards that was nationally accredited for middle

grades teaching. One teacher had seven years of

experience prior to the study. She was licensed to

teach English language arts and social studies in the

middle grades. The other was a new teacher who was

licensed to teach middle grades mathematics and

science and whose first year of teaching was the first

year in the study. A special educator with six years of

experience was added to the team midway through

the study, and his addition brought the total number

of educators on this team to three.

As a result of a university/private foundation

partnership, this team received extensive technology

resources and professional development to infuse

its practice with 21st century tools. In contrast to

other teams in the school, each student and teacher

on the Engagers received laptops for 1:1 wireless

computing. The team space was outfitted with media

production technology, presentation equipment, and a

wide variety of software. A Web portal served as the

program’s Web presence and as a central location for

curriculum resources. The team teachers were chosen

because of their commitment to using technology

within an integrative curriculum that emphasized

individualization, choice, and project-based learning.

The teachers were free to pursue any learning

objectives consistent with these commitments and

their appreciation for the needs and capacities of

young adolescents. There were no explicit standards

or objectives added to those already in place across

the school. One of the team teachers described the

purpose of the project: “I guess I feel like it’s adding

the 21st century learner to what is already good

middle school, middle level practice.”

The teachers participated in long term, embedded

professional development focused on integrating

technology in meaningful ways. A coach provided

by the university offered modeling, support, and

mentoring twice weekly through the first two years

of implementation. The coach came to the project

with 10 years of experience providing professional

development focused on the middle school concept

and on the integration of technology across the

curriculum and in classrooms with ready access to

personal computers and mobile technologies.

Data Collection

The university coach acted as an embedded

researcher who engaged in participant observation,

recording field notes twice weekly during the first

two years of the program and twice monthly for the

latter two years. Teachers and students participated in

formal interviews and focus groups twice per year for

these four years, averaging approximately one hour

per session. Further, informal interviews, reviews

of school and district documents, and examinations

of digital data were ongoing throughout the four

years. Digital data played a particularly important

role as much of the students’ work was in this

form, including photo stories, digital movies, blogs,

podcasts, and the team’s Web portal.

Data Analysis

We used NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software

package, to analyze the digital data, interview and

focus group transcriptions, and field notes. This

tool enabled rich analysis of the large volume of

data generated over four years. We used NVivo to

conduct open and axial coding (Strauss & Corbin,

1998) and to identify codes and categories across the

multiple data sets to classify emerging patterns. We

then created an indexing system to identify themes

within and across data sets (Patton, 2002). We

aligned the pertinent findings with three categories

of characteristics associated with effective middle

level schools (NMSA, 2010). Finally, we examined

the themes for trustworthiness in light of related

literature, triangulation across data types, and

member-checking through subsequent interviews

and consultations with participants and colleagues

(Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. A qualitative

methodology was appropriate for the descriptive and

analytical purposes of this research, but the findings

should not be generalized to other populations or

settings. For example, the study occurred in a rural

location with a predominantly White population.

Because the sample reflected a relatively low level of

racial/ethnic diversity, one might anticipate different

themes and issues arising from urban or diverse

settings. Further, the presence and participation of the

researchers at the site may have affected participants’

actions and responses. The rapport researchers

developed with participants over the course of four

years may have helped alleviate some of this effect, yet

RMLE Online— Volume 38, No. 7

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 5

it may also have introduced other complicating factors.

We attempted to minimize potential bias through the

ongoing use of triangulation and member-checking.

Findings

We discuss our findings in three sections aligned

with the categories of characteristics of effective

middle level schools in This We Believe (NMSA,

2010): (1) Culture and Community Characteristics;

(2) Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment

Characteristics; and (3) Leadership and Organizational

Characteristics. Rather than provide an exhaustive

review of how each This We Believe characteristic

intersects with the implementation of the 1:1 initiative,

we highlight the intersections we believe have the

greatest potential to inform efforts to integrate

technology in the best interest of young adolescents.

Culture and Community Characteristics

Efforts of Engagers teachers to implement team

development strategies varied considerably and

met with mixed results during the four years of the

study. When the teachers viewed team development

as a high priority and a prerequisite to student

learning, both teachers and students reported a more

welcoming and inclusive classroom climate and

greater satisfaction and success with teaching and

learning. However, team development was not always

a high priority. Throughout the study, technology

played a critical role in shaping team culture and

community but did not, in itself, compensate for a

lack of attention to intentional team building and

development.

Years 1–3 and the struggle for team culture. In

interviews and planning meetings, the teachers

regularly discussed their common belief in the

importance of team building as central to effective

teaming, teaching, and student learning. However,

during the first two years of the study, the teachers

did not implement a comprehensive team-building

program. Minimal attention was given to team-

building tasks or to the collaborative development

of norms. Symptoms of a poor team climate

were particularly evident in Year 2. According to

observation notes from a planning day halfway into

that school year, for instance, teachers described

turning to the building principal to intervene in

serious social conflicts, particularly among girls on

the team. In addition, the teachers enlisted the help of

an outside consultant to meet with the girls and design

opportunities for them to work and play effectively

together. In a planning meeting three months later,

the team was still wishing for a better support system

from beyond the team, including from the building

principal, psychologist and behavior interventionist,

and special educator. At that meeting, teachers were

already voicing concerns about the impact of current

students on incoming students in the next school year.

In a focus group with eighth graders a month later,

students appeared to share their teachers’ perceptions

of the climate, referring to pervasive “slacking off,”

routine off-task computer use, and group project work

described by one student as “a living hell.” With only

six weeks left in the school year, the lead teacher

conceded, “Things are calmer lately.”

As the teachers anticipated, Year 3 team building

suffered from the effects of returning students

carrying the weak culture from the previous year.

As one teacher observed, “Seventh graders coming

into a new environment, watching some of the eighth

graders, got into some bad habits that way.” Although

teachers designed an appropriate team-building

agenda, including technology-rich projects, such

as Portrait of a Teen podcasts, and My Home Town

videos, the team building process was implemented

slowly due to conflicting demands on teachers’ time

and attention. One Engagers teacher described the

dilemma he perceived in Year 3:

The beginning of the year seems like it’s kind

of a balance because … you want to do team

building [but] we have the [NCLB-mandated

standardized testing in October] and it’s …

really kind of hard to get in a rhythm in terms of

actually doing, producing work.

The conflicting demands of testing and team building

led teachers to delay critical team-building activities,

such as a field trip to a ropes course, until after the

testing. However, by the time teachers were able to

implement the team-building field trip, they observed

“some disrespect toward adults. There was just

kind of a lack of high expectations in terms of work

production, standards of work.” By mid-December,

after the field trip and the culmination of the podcast

and video projects, teachers reported that they

finally were seeing a more positive climate develop.

“Looking at the seventh graders and kind of where

they’ve come,” one teacher noted, “I see some strong

interests, adding to the culture of the team, adding

to that kind of culture of a work ethic and higher

expectations. … I’d say there’s more kind of this

collective sense of belonging.”

We observed a clear intersection between the

implementation of technology and the team climate.

Marked by behavior problems and a lack of trust

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 5

it may also have introduced other complicating factors.

We attempted to minimize potential bias through the

ongoing use of triangulation and member-checking.

Findings

We discuss our findings in three sections aligned

with the categories of characteristics of effective

middle level schools in This We Believe (NMSA,

2010): (1) Culture and Community Characteristics;

(2) Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment

Characteristics; and (3) Leadership and Organizational

Characteristics. Rather than provide an exhaustive

review of how each This We Believe characteristic

intersects with the implementation of the 1:1 initiative,

we highlight the intersections we believe have the

greatest potential to inform efforts to integrate

technology in the best interest of young adolescents.

Culture and Community Characteristics

Efforts of Engagers teachers to implement team

development strategies varied considerably and

met with mixed results during the four years of the

study. When the teachers viewed team development

as a high priority and a prerequisite to student

learning, both teachers and students reported a more

welcoming and inclusive classroom climate and

greater satisfaction and success with teaching and

learning. However, team development was not always

a high priority. Throughout the study, technology

played a critical role in shaping team culture and

community but did not, in itself, compensate for a

lack of attention to intentional team building and

development.

Years 1–3 and the struggle for team culture. In

interviews and planning meetings, the teachers

regularly discussed their common belief in the

importance of team building as central to effective

teaming, teaching, and student learning. However,

during the first two years of the study, the teachers

did not implement a comprehensive team-building

program. Minimal attention was given to team-

building tasks or to the collaborative development

of norms. Symptoms of a poor team climate

were particularly evident in Year 2. According to

observation notes from a planning day halfway into

that school year, for instance, teachers described

turning to the building principal to intervene in

serious social conflicts, particularly among girls on

the team. In addition, the teachers enlisted the help of

an outside consultant to meet with the girls and design

opportunities for them to work and play effectively

together. In a planning meeting three months later,

the team was still wishing for a better support system

from beyond the team, including from the building

principal, psychologist and behavior interventionist,

and special educator. At that meeting, teachers were

already voicing concerns about the impact of current

students on incoming students in the next school year.

In a focus group with eighth graders a month later,

students appeared to share their teachers’ perceptions

of the climate, referring to pervasive “slacking off,”

routine off-task computer use, and group project work

described by one student as “a living hell.” With only

six weeks left in the school year, the lead teacher

conceded, “Things are calmer lately.”

As the teachers anticipated, Year 3 team building

suffered from the effects of returning students

carrying the weak culture from the previous year.

As one teacher observed, “Seventh graders coming

into a new environment, watching some of the eighth

graders, got into some bad habits that way.” Although

teachers designed an appropriate team-building

agenda, including technology-rich projects, such

as Portrait of a Teen podcasts, and My Home Town

videos, the team building process was implemented

slowly due to conflicting demands on teachers’ time

and attention. One Engagers teacher described the

dilemma he perceived in Year 3:

The beginning of the year seems like it’s kind

of a balance because … you want to do team

building [but] we have the [NCLB-mandated

standardized testing in October] and it’s …

really kind of hard to get in a rhythm in terms of

actually doing, producing work.

The conflicting demands of testing and team building

led teachers to delay critical team-building activities,

such as a field trip to a ropes course, until after the

testing. However, by the time teachers were able to

implement the team-building field trip, they observed

“some disrespect toward adults. There was just

kind of a lack of high expectations in terms of work

production, standards of work.” By mid-December,

after the field trip and the culmination of the podcast

and video projects, teachers reported that they

finally were seeing a more positive climate develop.

“Looking at the seventh graders and kind of where

they’ve come,” one teacher noted, “I see some strong

interests, adding to the culture of the team, adding

to that kind of culture of a work ethic and higher

expectations. … I’d say there’s more kind of this

collective sense of belonging.”

We observed a clear intersection between the

implementation of technology and the team climate.

Marked by behavior problems and a lack of trust

RMLE Online— Volume 38, No. 7

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 6

between teachers and students, the poor climate

in Year 3 undermined teachers’ confidence that

they could implement technology-rich projects,

particularly those that might emphasize independent

or community-based learning. In turn, students

expressed disappointment that projects weren’t more

purposeful and meaningful, as in this exchange

among eighth graders in Year 3:

Student 1: Me and [my friend] really wanted

to do like an Audacity [audio software] project

about a place that we chose but [the teacher said]

we have to choose a place in the school, but we

wanted to do outside the school because her

grandfather and my dad works at [a hardware

store in town].

Student 2: We were supposed to do something

outside of school but we never did.

Student 3: My mom keeps driving me crazy

about that; it’s like, when are you going out in the

community?

Student 2: And they said clearly that we were.

Student 4: They said a lot of stuff and it never

really works out.

In short, neglecting key culture and community

characteristics nominally embraced by the teachers

triggered a downward spiral that undermined the

team’s efforts: teachers didn’t emphasize team

development; team climate suffered accordingly;

frustrated with student behavior, teachers backed away

from intensive, student-directed technology projects;

and students felt betrayed that teachers’ promises of

engaging, technology-rich learning were not fulfilled.

Year 4 and a renewed commitment. In contrast to the

previous years, in Year 4 Engagers teachers planned

and implemented intensive team building at the start of

the school year. One teacher described the process of

just the taking first three weeks … we didn’t

initiate any true academics. We did a lot of

academic type things but taking the first three

weeks, going to [a nearby summer camp] for

overnight was the absolute key, I think, to starting

the year off really, really, really well. Being able

to have meals together not in the school building.

Outdoors, playing. It was gorgeous weather. And

it was just—it just let everybody’s shoulders

down at the beginning of the year, especially. …

They weren’t trusting at first—some were, but

not all. But that trip was the key.

During the fourth year, technology strongly

supported the community building efforts. Instead

of withholding technology due to a difficult climate,

as in earlier years, teachers integrated it as a way

to establish the team culture. Students generated

personal timelines using xTimeline (xtimeline.

com); explored digital photography and Voicethread

(voicethread.com) to identify an image to represent

the team; created personal speaking avatars using

Voki (voki.com); and chose from Prezi (prezi.com),

PowerPoint, or Moviemaker to create presentations

about what they wanted to be when they grow up.

The impact of the teachers’ efforts, including a winter

outing to a ski area, lasted throughout the year. As

one teacher indicated in an April interview,

Just the effort at community building and

whatnot, it lends itself to strong relationships

between students. And I’ve heard students just

kind of hanging out together with each other and

saying, “This is the best team; this is us, I love

this team. I love hanging out with you guys.”

The team’s identity as a high-tech team was further

bolstered by the use of Evernote (evernote.com) for

personal note taking, Google Docs for collaborative file

sharing, and a Google Domain that included student

e-mail accounts and collaboratively constructed web

pages. This package of tools provided a communication

and workflow system among students and teachers

that was almost entirely electronic. This was widely

described as having transformed the organizational

lives of students, to their great relief. It also provided

a team culture based on common language,

communication patterns, and processes.

The teachers suggested that these efforts early in

the year contributed to an almost complete cultural

turnaround from the tumult of previous years. As one

teacher said,

Taking the first three weeks and having big …

character-building, identity-building projects

really helped. … I mean, just from seeing how the

students felt about themselves and the team from

the start of things ‘til now. … There’s some people

that are just extremely proud of what they do.

Using technology in team building appeared to

hold substantial benefits for students, particularly

those who had trouble engaging with their peers.

Technology introduced a new dimension of relevance

that made a difference in the schooling experience of

otherwise disengaged students. For example, while

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 6

between teachers and students, the poor climate

in Year 3 undermined teachers’ confidence that

they could implement technology-rich projects,

particularly those that might emphasize independent

or community-based learning. In turn, students

expressed disappointment that projects weren’t more

purposeful and meaningful, as in this exchange

among eighth graders in Year 3:

Student 1: Me and [my friend] really wanted

to do like an Audacity [audio software] project

about a place that we chose but [the teacher said]

we have to choose a place in the school, but we

wanted to do outside the school because her

grandfather and my dad works at [a hardware

store in town].

Student 2: We were supposed to do something

outside of school but we never did.

Student 3: My mom keeps driving me crazy

about that; it’s like, when are you going out in the

community?

Student 2: And they said clearly that we were.

Student 4: They said a lot of stuff and it never

really works out.

In short, neglecting key culture and community

characteristics nominally embraced by the teachers

triggered a downward spiral that undermined the

team’s efforts: teachers didn’t emphasize team

development; team climate suffered accordingly;

frustrated with student behavior, teachers backed away

from intensive, student-directed technology projects;

and students felt betrayed that teachers’ promises of

engaging, technology-rich learning were not fulfilled.

Year 4 and a renewed commitment. In contrast to the

previous years, in Year 4 Engagers teachers planned

and implemented intensive team building at the start of

the school year. One teacher described the process of

just the taking first three weeks … we didn’t

initiate any true academics. We did a lot of

academic type things but taking the first three

weeks, going to [a nearby summer camp] for

overnight was the absolute key, I think, to starting

the year off really, really, really well. Being able

to have meals together not in the school building.

Outdoors, playing. It was gorgeous weather. And

it was just—it just let everybody’s shoulders

down at the beginning of the year, especially. …

They weren’t trusting at first—some were, but

not all. But that trip was the key.

During the fourth year, technology strongly

supported the community building efforts. Instead

of withholding technology due to a difficult climate,

as in earlier years, teachers integrated it as a way

to establish the team culture. Students generated

personal timelines using xTimeline (xtimeline.

com); explored digital photography and Voicethread

(voicethread.com) to identify an image to represent

the team; created personal speaking avatars using

Voki (voki.com); and chose from Prezi (prezi.com),

PowerPoint, or Moviemaker to create presentations

about what they wanted to be when they grow up.

The impact of the teachers’ efforts, including a winter

outing to a ski area, lasted throughout the year. As

one teacher indicated in an April interview,

Just the effort at community building and

whatnot, it lends itself to strong relationships

between students. And I’ve heard students just

kind of hanging out together with each other and

saying, “This is the best team; this is us, I love

this team. I love hanging out with you guys.”

The team’s identity as a high-tech team was further

bolstered by the use of Evernote (evernote.com) for

personal note taking, Google Docs for collaborative file

sharing, and a Google Domain that included student

e-mail accounts and collaboratively constructed web

pages. This package of tools provided a communication

and workflow system among students and teachers

that was almost entirely electronic. This was widely

described as having transformed the organizational

lives of students, to their great relief. It also provided

a team culture based on common language,

communication patterns, and processes.

The teachers suggested that these efforts early in

the year contributed to an almost complete cultural

turnaround from the tumult of previous years. As one

teacher said,

Taking the first three weeks and having big …

character-building, identity-building projects

really helped. … I mean, just from seeing how the

students felt about themselves and the team from

the start of things ‘til now. … There’s some people

that are just extremely proud of what they do.

Using technology in team building appeared to

hold substantial benefits for students, particularly

those who had trouble engaging with their peers.

Technology introduced a new dimension of relevance

that made a difference in the schooling experience of

otherwise disengaged students. For example, while

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

RMLE Online— Volume 38, No. 7

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 7

discussing one of these disengaged students, an

Engagers teacher shared the following:

[The student’s guardian] just said as far as socially

and emotionally this year, he has completely

come up. He’s still very shy. He’s still not

one to take social risks but she said his social

development has just been exponential. I think [the

explanation is] two pronged. I think, one, he loves

technology. He’s so into what he’s doing. He’s had

opportunities to contribute, not so much … on an

academic level, but beyond, been able to make

contributions to the team, whether it’s updating

the website or having a little bit higher purpose.

But the other thing is that I think it’s been socially

responsive for him. He feels safer with the students

that he’s around and the teachers.

In this case, technology motivated a reluctant student

to participate in school and offered him an outlet

through which he could shine.

Team-building activities infused with technology

also helped convey the team’s democratic educational

philosophy:

We started with [digital] photography and

Voicethread [for] team building, identifying an

image that represents the team. We voted on it and

talked about being democratic and that kind of set

the stage for how this team was going to work—

nothing happens without your say, nothing works

without your input—and we meant it. And it was

nice to have that real, authentic, human-to-human,

not teacher-to-student, but just like hey, we have

an organization to run here and the three of us

[teachers] aren’t going to run it. We’re all going to

run it together if it’s going to work.

In this study, we observed frequent interplay between

effective team building and thoughtful technology

integration. Members of the Engagers spoke of

how these high-tech projects immediately engaged

students, helped team members know each other

and learn to work together, and shaped their overall

identity as a high-tech team. Team building activities

contributed to a more positive team climate and led

to more ambitious use of technology. The decision

to begin the school year with an intensive agenda

of technology and team-building activities was

particularly beneficial to the team and its students.

Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment

According to This We Believe, effective middle

level schools exhibit certain characteristics related

to curriculum, instruction, and assessment (NMSA,

2010). We observed numerous intersections between

these characteristics and 1:1 implementation with

the Engagers team. From the time the Engagers

team was formed, the curriculum was designed to

be technologically ambitious. During individual

interviews and focus groups, students consistently

identified technology-rich projects as their favorite

learning activities. Their preferences ranged across

all projects rather than with one particular project,

and nearly all students believed they learned more

through the technology-rich work.

Students consistently emphasized how technology

marked their team as unique. “A lot of our projects

aren’t really like a lot of other teams,” said one

student. “Like we use a lot of technology during

the year. It’s like I can only think of one or two

projects where we didn’t use technology.” In Year 4,

students used more—and more varied—technology

than ever. Students were given more flexibility in

choosing technologies to use for each project. Some

students openly admitted that they sometimes chose

a particular approach—creating a PowerPoint, for

instance—because it was easier and faster than

creating a Prezi or video. Yet, they were quick

to acknowledge that the latter are more rich and

interesting; and when they were motivated by the

topic and had adequate time in their work schedules,

they enjoyed more complicated technologies.

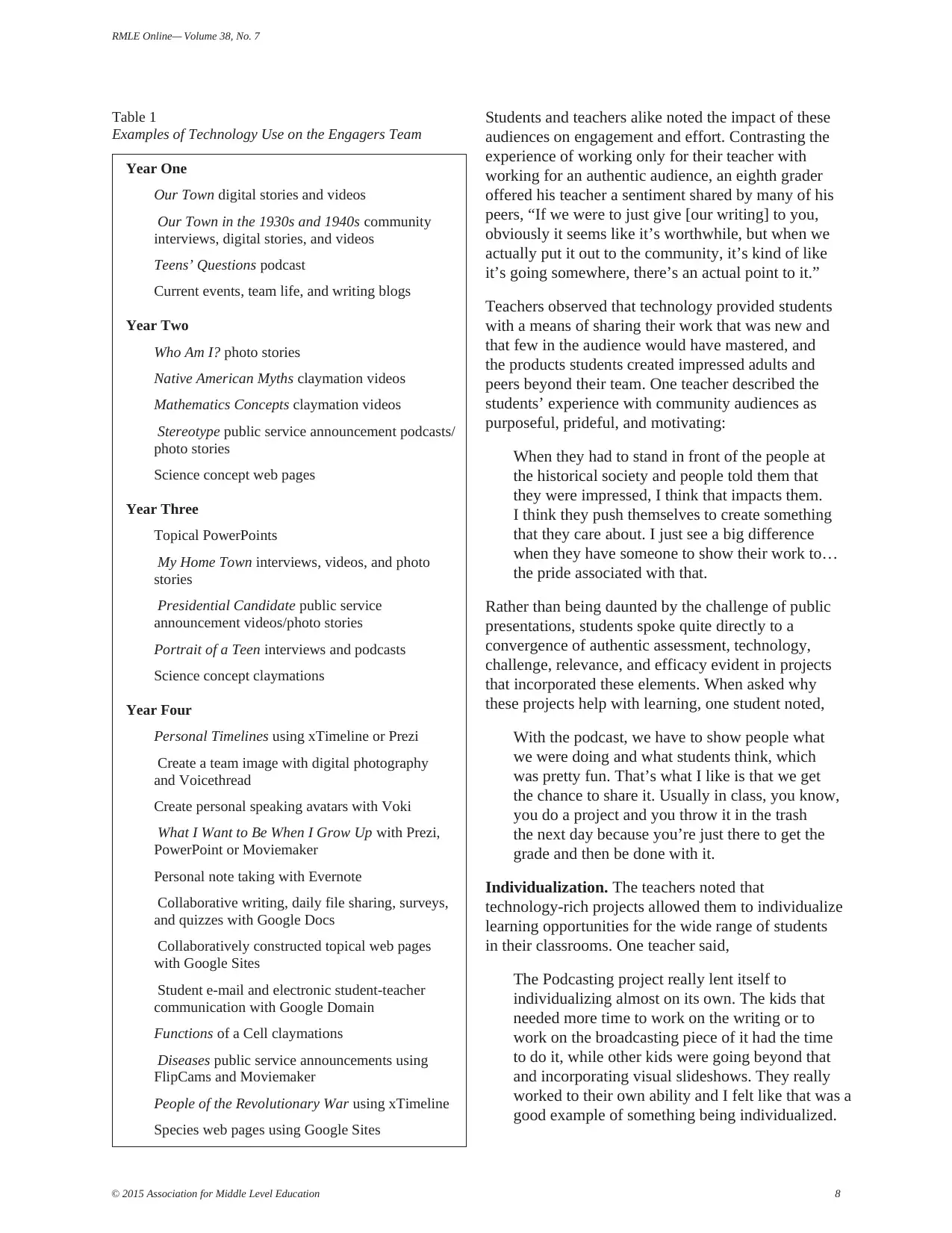

Table 1 depicts examples of technology the Engagers

team used during the four years of this study. The use

of technology within the curriculum connected with

the middle school concept in four key ways: authentic

assessment, opportunities for individualization,

substantial engagement, and a sense of purposeful

learning and meaningful student involvement.

Authentic assessment. The surrounding town played

an important role as an authentic audience for the

team’s work, and technology was particularly well

suited to sharing student work with audiences beyond

the school. Senior citizens and other guests assembled

in the town’s historical society, for example, to watch

and listen to students’ Photo Stories and videos about

town life in the years of depression and war during

the 20th century. The team also hosted an evening

at a local coffee house to share with the community

podcasts students developed for inquiries into issues

of personal concern to them, such as bullying,

stereotypes applied to their town, and safety in online

social networks. Parents, neighbors, schoolmates,

administrators, other teachers, and a reporter for the

town newspaper were among the guests.

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 7

discussing one of these disengaged students, an

Engagers teacher shared the following:

[The student’s guardian] just said as far as socially

and emotionally this year, he has completely

come up. He’s still very shy. He’s still not

one to take social risks but she said his social

development has just been exponential. I think [the

explanation is] two pronged. I think, one, he loves

technology. He’s so into what he’s doing. He’s had

opportunities to contribute, not so much … on an

academic level, but beyond, been able to make

contributions to the team, whether it’s updating

the website or having a little bit higher purpose.

But the other thing is that I think it’s been socially

responsive for him. He feels safer with the students

that he’s around and the teachers.

In this case, technology motivated a reluctant student

to participate in school and offered him an outlet

through which he could shine.

Team-building activities infused with technology

also helped convey the team’s democratic educational

philosophy:

We started with [digital] photography and

Voicethread [for] team building, identifying an

image that represents the team. We voted on it and

talked about being democratic and that kind of set

the stage for how this team was going to work—

nothing happens without your say, nothing works

without your input—and we meant it. And it was

nice to have that real, authentic, human-to-human,

not teacher-to-student, but just like hey, we have

an organization to run here and the three of us

[teachers] aren’t going to run it. We’re all going to

run it together if it’s going to work.

In this study, we observed frequent interplay between

effective team building and thoughtful technology

integration. Members of the Engagers spoke of

how these high-tech projects immediately engaged

students, helped team members know each other

and learn to work together, and shaped their overall

identity as a high-tech team. Team building activities

contributed to a more positive team climate and led

to more ambitious use of technology. The decision

to begin the school year with an intensive agenda

of technology and team-building activities was

particularly beneficial to the team and its students.

Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment

According to This We Believe, effective middle

level schools exhibit certain characteristics related

to curriculum, instruction, and assessment (NMSA,

2010). We observed numerous intersections between

these characteristics and 1:1 implementation with

the Engagers team. From the time the Engagers

team was formed, the curriculum was designed to

be technologically ambitious. During individual

interviews and focus groups, students consistently

identified technology-rich projects as their favorite

learning activities. Their preferences ranged across

all projects rather than with one particular project,

and nearly all students believed they learned more

through the technology-rich work.

Students consistently emphasized how technology

marked their team as unique. “A lot of our projects

aren’t really like a lot of other teams,” said one

student. “Like we use a lot of technology during

the year. It’s like I can only think of one or two

projects where we didn’t use technology.” In Year 4,

students used more—and more varied—technology

than ever. Students were given more flexibility in

choosing technologies to use for each project. Some

students openly admitted that they sometimes chose

a particular approach—creating a PowerPoint, for

instance—because it was easier and faster than

creating a Prezi or video. Yet, they were quick

to acknowledge that the latter are more rich and

interesting; and when they were motivated by the

topic and had adequate time in their work schedules,

they enjoyed more complicated technologies.

Table 1 depicts examples of technology the Engagers

team used during the four years of this study. The use

of technology within the curriculum connected with

the middle school concept in four key ways: authentic

assessment, opportunities for individualization,

substantial engagement, and a sense of purposeful

learning and meaningful student involvement.

Authentic assessment. The surrounding town played

an important role as an authentic audience for the

team’s work, and technology was particularly well

suited to sharing student work with audiences beyond

the school. Senior citizens and other guests assembled

in the town’s historical society, for example, to watch

and listen to students’ Photo Stories and videos about

town life in the years of depression and war during

the 20th century. The team also hosted an evening

at a local coffee house to share with the community

podcasts students developed for inquiries into issues

of personal concern to them, such as bullying,

stereotypes applied to their town, and safety in online

social networks. Parents, neighbors, schoolmates,

administrators, other teachers, and a reporter for the

town newspaper were among the guests.

RMLE Online— Volume 38, No. 7

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 8

Students and teachers alike noted the impact of these

audiences on engagement and effort. Contrasting the

experience of working only for their teacher with

working for an authentic audience, an eighth grader

offered his teacher a sentiment shared by many of his

peers, “If we were to just give [our writing] to you,

obviously it seems like it’s worthwhile, but when we

actually put it out to the community, it’s kind of like

it’s going somewhere, there’s an actual point to it.”

Teachers observed that technology provided students

with a means of sharing their work that was new and

that few in the audience would have mastered, and

the products students created impressed adults and

peers beyond their team. One teacher described the

students’ experience with community audiences as

purposeful, prideful, and motivating:

When they had to stand in front of the people at

the historical society and people told them that

they were impressed, I think that impacts them.

I think they push themselves to create something

that they care about. I just see a big difference

when they have someone to show their work to…

the pride associated with that.

Rather than being daunted by the challenge of public

presentations, students spoke quite directly to a

convergence of authentic assessment, technology,

challenge, relevance, and efficacy evident in projects

that incorporated these elements. When asked why

these projects help with learning, one student noted,

With the podcast, we have to show people what

we were doing and what students think, which

was pretty fun. That’s what I like is that we get

the chance to share it. Usually in class, you know,

you do a project and you throw it in the trash

the next day because you’re just there to get the

grade and then be done with it.

Individualization. The teachers noted that

technology-rich projects allowed them to individualize

learning opportunities for the wide range of students

in their classrooms. One teacher said,

The Podcasting project really lent itself to

individualizing almost on its own. The kids that

needed more time to work on the writing or to

work on the broadcasting piece of it had the time

to do it, while other kids were going beyond that

and incorporating visual slideshows. They really

worked to their own ability and I felt like that was a

good example of something being individualized.

Table 1

Examples of Technology Use on the Engagers Team

Year One

Our Town digital stories and videos

Our Town in the 1930s and 1940s community

interviews, digital stories, and videos

Teens’ Questions podcast

Current events, team life, and writing blogs

Year Two

Who Am I? photo stories

Native American Myths claymation videos

Mathematics Concepts claymation videos

Stereotype public service announcement podcasts/

photo stories

Science concept web pages

Year Three

Topical PowerPoints

My Home Town interviews, videos, and photo

stories

Presidential Candidate public service

announcement videos/photo stories

Portrait of a Teen interviews and podcasts

Science concept claymations

Year Four

Personal Timelines using xTimeline or Prezi

Create a team image with digital photography

and Voicethread

Create personal speaking avatars with Voki

What I Want to Be When I Grow Up with Prezi,

PowerPoint or Moviemaker

Personal note taking with Evernote

Collaborative writing, daily file sharing, surveys,

and quizzes with Google Docs

Collaboratively constructed topical web pages

with Google Sites

Student e-mail and electronic student-teacher

communication with Google Domain

Functions of a Cell claymations

Diseases public service announcements using

FlipCams and Moviemaker

People of the Revolutionary War using xTimeline

Species web pages using Google Sites

© 2015 Association for Middle Level Education 8