Schoolyard Renovation & Children's Physical Activity: A Study

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/30

|9

|7869

|263

Report

AI Summary

This report evaluates the impact of schoolyard renovation strategies, specifically the Learning Landscapes (LL) program in Denver, on children's physical activity levels. The study uses the System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity (SOPLAY) to compare utilization and activity rates in renovated L...

RESEARCH Open Access

An assessment of schoolyard renovation

strategies to encourage children’s physical

activity

Peter Anthamatten1*

, Lois Brink2

, Sarah Lampe3

, Emily Greenwood2

, Beverly Kingston4 and Claudio Nigg5

Abstract

Background:Children in poor and minority neighborhoods often lack adequate environmentalsupport for healthy

physicaldevelopment and community interventions designed to improve physicalactivity resources serve as an

important approach to addressing obesity.In Denver,the Learning Landscapes (LL)program has constructed over

98 culturally-tailored schoolyard play spaces at elementary schools with the goalto encourage utilization of play

spaces and physicalactivity.In spite of enthusiasm about such projects to improve urban environments,little work

has evaluated their impact or success in achieving their stated objectives.This study evaluates the impacts of LL

construction and recency of renovation on schoolyard utilization and the physicalactivity rates of children,both

during and outside of school,using an observationalstudy design.

Methods:This study employs a quantitative method for evaluating levels of physicalactivity of individuals and

associated environmentalcharacteristics in play and leisure environments.Schools were selected on the basis of

their participation in the LL program,the recency of schoolyard renovation,the size of the school,and the social

and demographic characteristics of the schoolpopulation.Activity in the schoolyards was measured using the

System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity (SOPLAY),a validated quantitative method for evaluating levels of

physicalactivity of individuals in play and leisure environments.Trained observers collected measurements before

school,during schoolrecess,after school,and on weekends.Overallutilization (the totalnumber of children

observed on the grounds) and the rate of activity (the percentage of children observed who were physicall

active)were analyzed.Observations were compared using t-tests and the data were stratified by gender for fur

analysis.In order to assess the impacts of LL renovation,recently-constructed LL schoolyards were compared to LL

schoolyards with older construction,as wellas un-renovated schoolyards.

Results:Overallutilization was significantly higher at LL schools than at un-renovated schools for most observ

periods.Notably,LL renovation had no impact on girl’s utilization on the weekends,although differences were

observed for allother periods.There were no differences in rates of activity for any comparison.With the exception

of the number of boys observed,there was no statistically significant difference in activity when recently-

constructed LL schools are compared to LL schools with older construction dates and there was no differen

observed in comparisons of older LL with unrenovated sites.

Conclusions:While we observed greater utilization and physicalactivity in schools with LL,the impact of specific

features of LL renovation is not clear.However,schoolyard renovation and programs to encourage schoolyard use

before and after schoolmay offer a means to encourage greater physicalactivity among children,and girls in

particular.Additionalstudy of schoolyard renovation may shed light on the specific reasons for these findings o

suggest effective policies to improve the physicalactivity resources of poor and minority neighborhoods.

* Correspondence:peter.anthamatten@ucdenver.edu

1Department of Geography and EnvironmentalSciences,University of

Colorado Denver,Denver,CO,USA

Fulllist of author information is available at the end ofthe article

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

© 2011 Anthamatten et al;licensee BioMed CentralLtd.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms ofthe Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided the originalwork is properly cited.

An assessment of schoolyard renovation

strategies to encourage children’s physical

activity

Peter Anthamatten1*

, Lois Brink2

, Sarah Lampe3

, Emily Greenwood2

, Beverly Kingston4 and Claudio Nigg5

Abstract

Background:Children in poor and minority neighborhoods often lack adequate environmentalsupport for healthy

physicaldevelopment and community interventions designed to improve physicalactivity resources serve as an

important approach to addressing obesity.In Denver,the Learning Landscapes (LL)program has constructed over

98 culturally-tailored schoolyard play spaces at elementary schools with the goalto encourage utilization of play

spaces and physicalactivity.In spite of enthusiasm about such projects to improve urban environments,little work

has evaluated their impact or success in achieving their stated objectives.This study evaluates the impacts of LL

construction and recency of renovation on schoolyard utilization and the physicalactivity rates of children,both

during and outside of school,using an observationalstudy design.

Methods:This study employs a quantitative method for evaluating levels of physicalactivity of individuals and

associated environmentalcharacteristics in play and leisure environments.Schools were selected on the basis of

their participation in the LL program,the recency of schoolyard renovation,the size of the school,and the social

and demographic characteristics of the schoolpopulation.Activity in the schoolyards was measured using the

System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity (SOPLAY),a validated quantitative method for evaluating levels of

physicalactivity of individuals in play and leisure environments.Trained observers collected measurements before

school,during schoolrecess,after school,and on weekends.Overallutilization (the totalnumber of children

observed on the grounds) and the rate of activity (the percentage of children observed who were physicall

active)were analyzed.Observations were compared using t-tests and the data were stratified by gender for fur

analysis.In order to assess the impacts of LL renovation,recently-constructed LL schoolyards were compared to LL

schoolyards with older construction,as wellas un-renovated schoolyards.

Results:Overallutilization was significantly higher at LL schools than at un-renovated schools for most observ

periods.Notably,LL renovation had no impact on girl’s utilization on the weekends,although differences were

observed for allother periods.There were no differences in rates of activity for any comparison.With the exception

of the number of boys observed,there was no statistically significant difference in activity when recently-

constructed LL schools are compared to LL schools with older construction dates and there was no differen

observed in comparisons of older LL with unrenovated sites.

Conclusions:While we observed greater utilization and physicalactivity in schools with LL,the impact of specific

features of LL renovation is not clear.However,schoolyard renovation and programs to encourage schoolyard use

before and after schoolmay offer a means to encourage greater physicalactivity among children,and girls in

particular.Additionalstudy of schoolyard renovation may shed light on the specific reasons for these findings o

suggest effective policies to improve the physicalactivity resources of poor and minority neighborhoods.

* Correspondence:peter.anthamatten@ucdenver.edu

1Department of Geography and EnvironmentalSciences,University of

Colorado Denver,Denver,CO,USA

Fulllist of author information is available at the end ofthe article

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

© 2011 Anthamatten et al;licensee BioMed CentralLtd.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms ofthe Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided the originalwork is properly cited.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Background

Obesity has become an increasingly troublesome health

problem in both wealthy and poor regions around the

world [1];the World Health Organization reports that

there are now over one billion overweightadults,at

least 300 million ofwhom are obese [2].Obesity pre-

sents a particularly alarming health concern in the Uni-

ted States, where recent estimates are that

approximately one third of children in the United States

are considered overweight or obese [3].

Policy designed to change obesogenic environments

aims to implementchange thatboth reduce energy

intake (by encouraging a healthy diet)and provide

opportunities for increased energy output (by encoura-

ging physicalactivity) [4].Although behavioralchange is

a criticalcomponent to addressing obesity,interventions

designed to modify individualbehavior to reduce caloric

intake have had limited success in preventing obesity on

a long-term basis [3].Although there is disagreement

about which side ofthe energy equation is the most

effective in terms ofpolicy, extensive research has

demonstrated that the built environment plays a key

role in obesity-related behavior (e.g.,[5-8]).

While there may be only a weak to moderate link

between physicalactivity and obesity rates,there are

numerous additionalhealth benefits associated with

increased physicalactivity.A recent literature review

reports thatphysicalactivity is linked with reduced

blood pressure,lower levels ofcholesteroland blood

lipids, reduced incidenceof metabolic syndrome,

increased bone mineraldensity,as wellas reduced rates

of depression [9]. Understanding the relationship

between the built environment and physicalactivity and

the specific implications of particular modifications to

the built environment may contribute to strategies to

reduce obesity prevalence [10] in addition to these other

health benefits.

Along with transportation patterns and land-use pat-

terns,design features are one of the key areas of inquiry

in studies of the built environment and physicalactivity

[11-13].A number of specific design features pertaining

to children’s environments have been investigated in

previous research.Time spent outdoors, accessto

recreationalfacilities and schoolyards [8,14] and proxi-

mity and number of play spaces and facilities to home

[15] are associated with higher levels of physicalactivity

in children and adolescents.Adding an additionalrecess

period each day is associated with greater physical activ-

ity [16],while limited outdoor play time has been found

to correlate with a high body mass index in young chil-

dren [17].If it is designed well,the outdoor built envir-

onment can create opportunities for healthy behavior

change among children.

Compared to white children,children from African-

American and Hispanic ethnicities are particularly likely

to suffer from obesity,experience abnormally high glu-

cose levels,and suffer from a higher prevalence of dia-

betes [18-20].These observations could be attributed in

part to the socialand built environments of many min-

ority children living in impoverished urban neighbor-

hoods,which often failto support healthy development

and provide limited opportunities for healthy behavior,

especially with respect to physicalactivity.Poor and

minority children often have limited access to outdoor

play spaces and structured opportunities for involve-

ment in organized sports and other activities [19] and

are more likely to have lower fitness levels.The reasons

behind these disparities are nuanced and complex,but it

might be possible to develop planning and design poli-

cies to address geographic inequality.Some research has

shown that parents in low-income neighbourhoods have

increasingly restricted their children’s activity out of

concerns for safety [21],and that design policies can

have an impact on this concern [22].Interventions to

improve the safety ofschoolyards have been shown to

improve schoolyard utilization [23].Indeed,commu-

nities that are designed to support physicalactivity have

been found to have 100% higher rates of sufficient phy-

sicalactivity than those with no supportive attributes

[8].Facets of the built environment,such as the density

of residences [24],general walkability [25],and the avail-

ability of recreational spaces and facilities [26,27] may be

also linked to physicalactivity,although research often

yields mixed results [21].

With the average child spending 1300 hours at school

each year,schools are a valuable physical environment

and social resource in efforts to promote physical activity.

School wellness policies,community building initiatives,

and walk-to-school programs [21] are a few examples of

school-based strategies designed to encourage physical

activity.In spite of a flourishing body of social-scientific

and public health literature examining the relationship

between physical activity and urban environments,there

remains little work that specifically examines the impacts

of recreational space renovation at schools.There is evi-

dence that renovated schoolyards are more widely used

by adults and children (especially boys) than un-reno-

vated schoolyards [28].Small,inexpensive interventions

that have changed the structure of the physical environ-

ment,especially within the schoolenvironment,have

shown significant positive correlations with physical

activity levels.These interventions include painting the

schoolyards [29],providing game equipment [30],and

even increasing the number of balls available to youth

[31]. Higher physical activity levels have been observed in

schoolyards that have multicolored painting compared to

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 2 of 9

Obesity has become an increasingly troublesome health

problem in both wealthy and poor regions around the

world [1];the World Health Organization reports that

there are now over one billion overweightadults,at

least 300 million ofwhom are obese [2].Obesity pre-

sents a particularly alarming health concern in the Uni-

ted States, where recent estimates are that

approximately one third of children in the United States

are considered overweight or obese [3].

Policy designed to change obesogenic environments

aims to implementchange thatboth reduce energy

intake (by encouraging a healthy diet)and provide

opportunities for increased energy output (by encoura-

ging physicalactivity) [4].Although behavioralchange is

a criticalcomponent to addressing obesity,interventions

designed to modify individualbehavior to reduce caloric

intake have had limited success in preventing obesity on

a long-term basis [3].Although there is disagreement

about which side ofthe energy equation is the most

effective in terms ofpolicy, extensive research has

demonstrated that the built environment plays a key

role in obesity-related behavior (e.g.,[5-8]).

While there may be only a weak to moderate link

between physicalactivity and obesity rates,there are

numerous additionalhealth benefits associated with

increased physicalactivity.A recent literature review

reports thatphysicalactivity is linked with reduced

blood pressure,lower levels ofcholesteroland blood

lipids, reduced incidenceof metabolic syndrome,

increased bone mineraldensity,as wellas reduced rates

of depression [9]. Understanding the relationship

between the built environment and physicalactivity and

the specific implications of particular modifications to

the built environment may contribute to strategies to

reduce obesity prevalence [10] in addition to these other

health benefits.

Along with transportation patterns and land-use pat-

terns,design features are one of the key areas of inquiry

in studies of the built environment and physicalactivity

[11-13].A number of specific design features pertaining

to children’s environments have been investigated in

previous research.Time spent outdoors, accessto

recreationalfacilities and schoolyards [8,14] and proxi-

mity and number of play spaces and facilities to home

[15] are associated with higher levels of physicalactivity

in children and adolescents.Adding an additionalrecess

period each day is associated with greater physical activ-

ity [16],while limited outdoor play time has been found

to correlate with a high body mass index in young chil-

dren [17].If it is designed well,the outdoor built envir-

onment can create opportunities for healthy behavior

change among children.

Compared to white children,children from African-

American and Hispanic ethnicities are particularly likely

to suffer from obesity,experience abnormally high glu-

cose levels,and suffer from a higher prevalence of dia-

betes [18-20].These observations could be attributed in

part to the socialand built environments of many min-

ority children living in impoverished urban neighbor-

hoods,which often failto support healthy development

and provide limited opportunities for healthy behavior,

especially with respect to physicalactivity.Poor and

minority children often have limited access to outdoor

play spaces and structured opportunities for involve-

ment in organized sports and other activities [19] and

are more likely to have lower fitness levels.The reasons

behind these disparities are nuanced and complex,but it

might be possible to develop planning and design poli-

cies to address geographic inequality.Some research has

shown that parents in low-income neighbourhoods have

increasingly restricted their children’s activity out of

concerns for safety [21],and that design policies can

have an impact on this concern [22].Interventions to

improve the safety ofschoolyards have been shown to

improve schoolyard utilization [23].Indeed,commu-

nities that are designed to support physicalactivity have

been found to have 100% higher rates of sufficient phy-

sicalactivity than those with no supportive attributes

[8].Facets of the built environment,such as the density

of residences [24],general walkability [25],and the avail-

ability of recreational spaces and facilities [26,27] may be

also linked to physicalactivity,although research often

yields mixed results [21].

With the average child spending 1300 hours at school

each year,schools are a valuable physical environment

and social resource in efforts to promote physical activity.

School wellness policies,community building initiatives,

and walk-to-school programs [21] are a few examples of

school-based strategies designed to encourage physical

activity.In spite of a flourishing body of social-scientific

and public health literature examining the relationship

between physical activity and urban environments,there

remains little work that specifically examines the impacts

of recreational space renovation at schools.There is evi-

dence that renovated schoolyards are more widely used

by adults and children (especially boys) than un-reno-

vated schoolyards [28].Small,inexpensive interventions

that have changed the structure of the physical environ-

ment,especially within the schoolenvironment,have

shown significant positive correlations with physical

activity levels.These interventions include painting the

schoolyards [29],providing game equipment [30],and

even increasing the number of balls available to youth

[31]. Higher physical activity levels have been observed in

schoolyards that have multicolored painting compared to

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 2 of 9

those without [32].The incorporation of culturally-tai-

lored schoolyard elements may also encourage physical

activity and ultimately contribute to the reduction of obe-

sity [33],which is especially important in communities

with large ethnic minority populations.In a study that

used the same observation method as the current one,

Sallis et al. conclude that making improvements to school

environments could increase the physical activity of stu-

dents throughout the schoolday [34].After observing

physical activity across twenty-four middle schools in San

Diego,they determined that physical amenities,such as

area type,area size,and permanent improvements (such

as basketball courts and football goals) were associated

with increased physicalactivity among both boys and

girls.The authors conclude that “if we build it,they will

come” [34];that schooldesign and renovation efforts

may improve physical activity among children.

Learning Landscapes

A Learning Landscape (LL) is a noveltype of schoolyard

that offers a diversity of elements lacking in traditional

schoolyards.Such elements include schoolyard gateways,

shade structures,banners,gardens,public art,student

art,and art tile projects.LLs are designed and built by a

non-profit partnership between the University of Color-

ado Denver’s College of Architecture and Planning and

a local,urban schooldistrict.Since its inception,LLs

has attracted the involvementof 8,000 community

volunteers,18,000 students,250,000 community mem-

bers,250 Americorps volunteers,and 20 volunteer orga-

nizations.The initiative has raised 47 million dollars for

the completion of 82 new LL schoolyard sites.

After six years of collaboration between parents,ele-

mentary schoolstudents,staff,faculty,neighbors,local

businesses and landscape architecture graduate students,

the first schoolyard was completed in 1998.Although

the project merely constructed redesigned schoolyards

initially,it has since evolved into a city-wide initiative

that redefines traditionalschool grounds and opens

them up for community use outside of schoolhours.LL

projects fulfilled a fundamentalgoalof landscape archi-

tecture:“to engage in scholarly activities that strike a

balance between traditionalacademic and professional

endeavors,while at the same time stretching the bound-

aries of landscape architecture design” [35].

The LL Initiative has transformed 82 neglected Denver

elementary schoolschoolyards into attractive and safe

multi-use schoolyards that are tailored to the needs and

desires of the localcommunity.This program has been

sponsored by a broad-based,public-private partnership

and is directed by expert faculty and masters-levelstu-

dents from the Department of Landscape Architecture

at the University of Colorado at Denver.In 2000,Brink’s

UC Denver Program partnered with a localschool

district and private foundations to raise funds to con-

struct 22 inner-city schoolyards.Since that time,local

bonds have been passed to secure funding for additional

LLs for a total of 98 by the end of 2012.

Successof LLs has traditionally been evaluated

through a collaborative effort between LLs,the school

district,students,community leaders,and city officials,

using pre- and post-construction surveys and focus

groups.The extent of this program produces a valuable

opportunity to assess the impacts of schoolyard renova-

tion on children’s physicalactivity patterns.The goalof

this study is to investigate the effect of these schoolyard

renovations in low-income urban areas on physical

activity among children by comparing utilization of LL

schoolyards with matched controlschoolyards.Specifi-

cally,we wish to consider 1) whether LL schoolyards are

utilized more than non-LL schoolyards and 2) whether

children utilizing LL schoolyards are more likely to exhi-

bit moderate- to vigorous physicalactivity behaviour.A

secondary objective is to evaluate whether the recency

of schoolyard renovation has an impact on utilization

and physicalactivity.

Methods

Owing to the fact that the localschooldistrict selected

which schools participated in the LL program,randomi-

zation was not possible.Constructed LLs were matched

with schools possessing recently-built LLs (constructed

within the past year),as wellas controlsites lacking

schoolyard renovation.Case selection criteria included

the percentage ofstudents receiving free or reduced

lunch, students’race and ethnicity,and schoolsize,

based on the totalnumber ofstudents enrolled in the

school(table 1).After permission was obtained from the

school district, principles ofcandidate schools were

approached and permission was requested to conduct

the study on their grounds.All the schools that were

approached agreed to participate in the study.The study

was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional

Review Board.

Because inclusion in the LL program was initially pro-

vided for low-income schools,the schools eligible for this

study were located in deprived neighborhoods,populated

largely by ethnic minorities.Study schools are therefore

located in Denver neighborhoods facing significant social,

economic,and educational challenges.Study sites were

chosen from three different locations in Denver.Group A

schools are from a predominately African-American

neighborhoods characterized by significant gang activity.

Group B and C schools are in neighborhoods located

between three and five miles from downtown Denver and

are comprised of poor,predominately Latino neighbour-

hoods. Schools in groups B and C are similar with respect

to income and ethnicity,but are distinguished by school

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 3 of 9

lored schoolyard elements may also encourage physical

activity and ultimately contribute to the reduction of obe-

sity [33],which is especially important in communities

with large ethnic minority populations.In a study that

used the same observation method as the current one,

Sallis et al. conclude that making improvements to school

environments could increase the physical activity of stu-

dents throughout the schoolday [34].After observing

physical activity across twenty-four middle schools in San

Diego,they determined that physical amenities,such as

area type,area size,and permanent improvements (such

as basketball courts and football goals) were associated

with increased physicalactivity among both boys and

girls.The authors conclude that “if we build it,they will

come” [34];that schooldesign and renovation efforts

may improve physical activity among children.

Learning Landscapes

A Learning Landscape (LL) is a noveltype of schoolyard

that offers a diversity of elements lacking in traditional

schoolyards.Such elements include schoolyard gateways,

shade structures,banners,gardens,public art,student

art,and art tile projects.LLs are designed and built by a

non-profit partnership between the University of Color-

ado Denver’s College of Architecture and Planning and

a local,urban schooldistrict.Since its inception,LLs

has attracted the involvementof 8,000 community

volunteers,18,000 students,250,000 community mem-

bers,250 Americorps volunteers,and 20 volunteer orga-

nizations.The initiative has raised 47 million dollars for

the completion of 82 new LL schoolyard sites.

After six years of collaboration between parents,ele-

mentary schoolstudents,staff,faculty,neighbors,local

businesses and landscape architecture graduate students,

the first schoolyard was completed in 1998.Although

the project merely constructed redesigned schoolyards

initially,it has since evolved into a city-wide initiative

that redefines traditionalschool grounds and opens

them up for community use outside of schoolhours.LL

projects fulfilled a fundamentalgoalof landscape archi-

tecture:“to engage in scholarly activities that strike a

balance between traditionalacademic and professional

endeavors,while at the same time stretching the bound-

aries of landscape architecture design” [35].

The LL Initiative has transformed 82 neglected Denver

elementary schoolschoolyards into attractive and safe

multi-use schoolyards that are tailored to the needs and

desires of the localcommunity.This program has been

sponsored by a broad-based,public-private partnership

and is directed by expert faculty and masters-levelstu-

dents from the Department of Landscape Architecture

at the University of Colorado at Denver.In 2000,Brink’s

UC Denver Program partnered with a localschool

district and private foundations to raise funds to con-

struct 22 inner-city schoolyards.Since that time,local

bonds have been passed to secure funding for additional

LLs for a total of 98 by the end of 2012.

Successof LLs has traditionally been evaluated

through a collaborative effort between LLs,the school

district,students,community leaders,and city officials,

using pre- and post-construction surveys and focus

groups.The extent of this program produces a valuable

opportunity to assess the impacts of schoolyard renova-

tion on children’s physicalactivity patterns.The goalof

this study is to investigate the effect of these schoolyard

renovations in low-income urban areas on physical

activity among children by comparing utilization of LL

schoolyards with matched controlschoolyards.Specifi-

cally,we wish to consider 1) whether LL schoolyards are

utilized more than non-LL schoolyards and 2) whether

children utilizing LL schoolyards are more likely to exhi-

bit moderate- to vigorous physicalactivity behaviour.A

secondary objective is to evaluate whether the recency

of schoolyard renovation has an impact on utilization

and physicalactivity.

Methods

Owing to the fact that the localschooldistrict selected

which schools participated in the LL program,randomi-

zation was not possible.Constructed LLs were matched

with schools possessing recently-built LLs (constructed

within the past year),as wellas controlsites lacking

schoolyard renovation.Case selection criteria included

the percentage ofstudents receiving free or reduced

lunch, students’race and ethnicity,and schoolsize,

based on the totalnumber ofstudents enrolled in the

school(table 1).After permission was obtained from the

school district, principles ofcandidate schools were

approached and permission was requested to conduct

the study on their grounds.All the schools that were

approached agreed to participate in the study.The study

was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional

Review Board.

Because inclusion in the LL program was initially pro-

vided for low-income schools,the schools eligible for this

study were located in deprived neighborhoods,populated

largely by ethnic minorities.Study schools are therefore

located in Denver neighborhoods facing significant social,

economic,and educational challenges.Study sites were

chosen from three different locations in Denver.Group A

schools are from a predominately African-American

neighborhoods characterized by significant gang activity.

Group B and C schools are in neighborhoods located

between three and five miles from downtown Denver and

are comprised of poor,predominately Latino neighbour-

hoods. Schools in groups B and C are similar with respect

to income and ethnicity,but are distinguished by school

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 3 of 9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

size (group B schools have an average attendance of 559

and group C schools an average attendance of 395). These

groups were formed in order to select adequate controls

on the basis of income,ethnicity,and school size.Each of

the groups contains one school that had LL construction

within a year before the data were collected,one school

with older LL construction (constructed two or more

years prior to the newly-renovated schoolyards) and one

school without renovated school grounds (i.e.,with no LL

construction).Children observed in this study were ele-

mentary school students, between six and eleven years old.

Children were observed using the System for Obser-

ving Play and Leisure Activity in Youth (SOPLAY).

SOPLAY is a quantitative method for evaluating levels

of physical activity of individuals and associated environ-

mentalcharacteristics in play and leisure environment

[36].Target areas are predetermined and defined as

“locations likely to provide opportunities for students to

be physically active” [37] in which observers record the

number of individuals present,their activity levels,and

their gender.Each schoolyard was divided into activity

zones that expressed the ground plane condition and

the type of activity occurring.The observation protocol

requires the identification of schoolyard variables with

the greatest impact on children’s physicalactivity based

on area type,size,and permanent improvements.Obser-

vers were trained in SOPLAY observation methodology

by a certified SOPLAY instructor.Children who are

observed to be sedentary or walking are not considered

to be physically active and children who are observed

engaging in vigorous physicalactivity or in a “primary

activity” such as using the schoolyard equipment such

as a swing or jungle gym,are considered to be physically

active.While the observers are able to distinguish

between children and adults,they were notable to

account for the age of specific children.

Observations were conducted over four days at each

schoolto obtain accurate measurements.Two obser-

vers simultaneously observed the activity area for 20%

of the totaldata collection time to test the reliability

of the data,resulting in a reliability estimate of87%.

Observers were not part of the research team to

ensure accuracy ofthe data collected.Data were col-

lected from schoolyards atparticipating elementary

schools in Denver between September 19 and October

29,2005 and between September 29 and October 19,

2006 at regular time periods before the beginning of

school,during schoolrecess,after the schoolfinished,

and during the weekends.Because the observations

covered the entire schoolyards,total schoolyard use

and the number ofchildren on the schoolyard at any

particular observation point could be estimated from

these surveys.Observationalscans capturing activity

on the entire schoolyard were treated as the unitof

analysis.Between 28 and 30 schoolyard observations

were conducted at each site.

Study Design

While utilization of the schoolyards is more or less

mandatory for the children during schoolrecess,chil-

dren may optionally use the schoolyard facilities before

or after schoolor on weekends.It is hypothesized that

by building innovative,culturally-sensitive schoolyard

facilities,more children willbe attracted to using the

schoolyard facilities,particularly during these optional

periods.In order to address this question,the number

of children observed utilizing the schoolyards before

school,during lunch recess,after school,and on week-

ends is compared across LL and non-LL schools in t-

tests.Additionally,the data were stratified by gender to

examine whether there were gender-based differences in

utilization.In order to account for the enrollment differ-

ences within the study groups,all observations are stan-

dardized against totalschoolenrollment and figures are

reported as the number ofchildren observed per 100

children enrolled (children attending the school).

Although children attending the schoolmay utilize

schoolyards,particularly on weekends,schoolyard use is

predominately by children from the school.Because the

intent of this study is to evaluate schoolyards as means

of encouraging schoolyard utilization and physical

activity among children,two different outcome measures

are reported:1) the number of children observed on the

playground and 2) the percentage of children engaged in

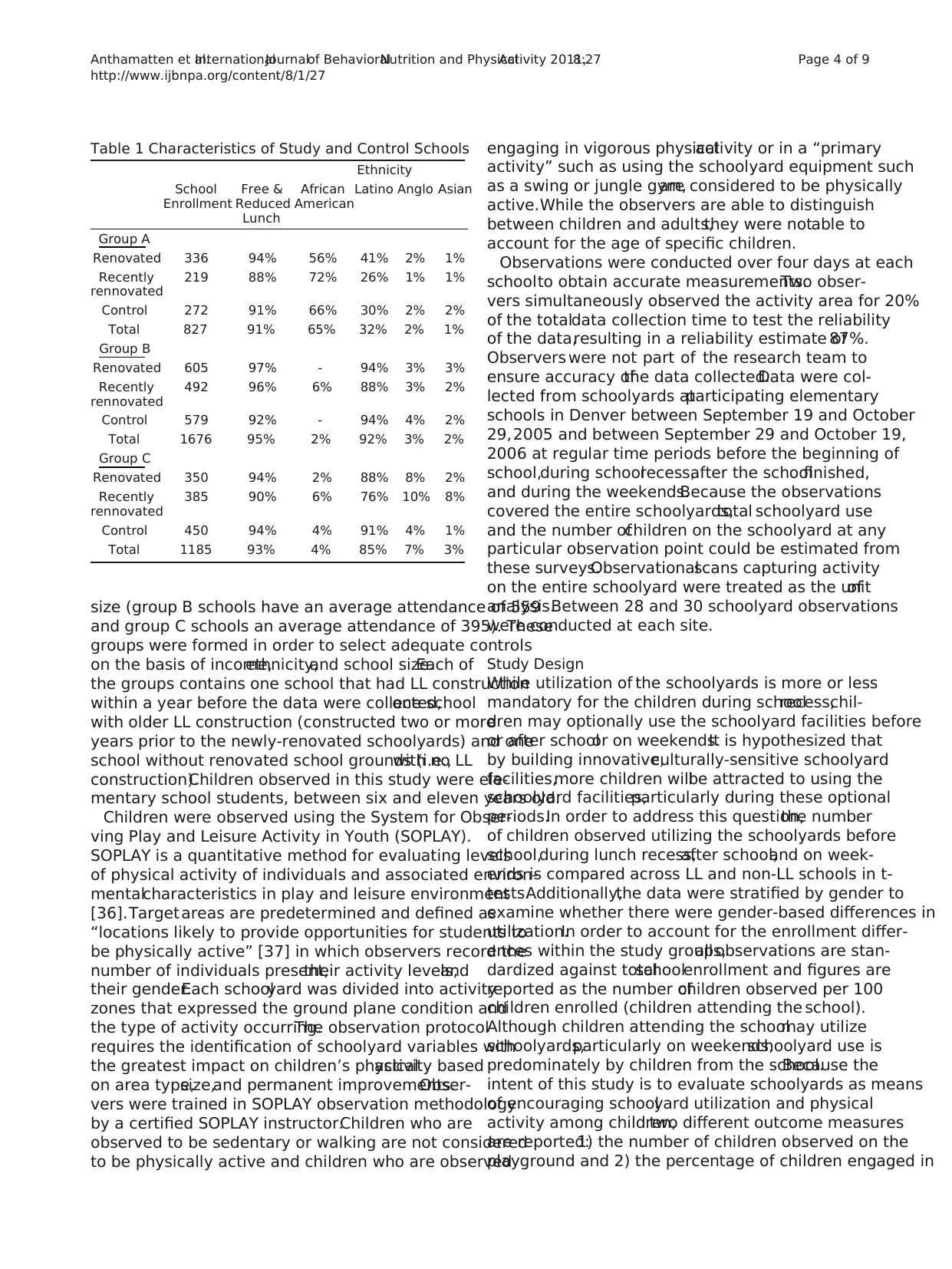

Table 1 Characteristics of Study and Control Schools

Ethnicity

School

Enrollment

Free &

Reduced

Lunch

African

American

Latino Anglo Asian

Group A

Renovated 336 94% 56% 41% 2% 1%

Recently

rennovated

219 88% 72% 26% 1% 1%

Control 272 91% 66% 30% 2% 2%

Total 827 91% 65% 32% 2% 1%

Group B

Renovated 605 97% - 94% 3% 3%

Recently

rennovated

492 96% 6% 88% 3% 2%

Control 579 92% - 94% 4% 2%

Total 1676 95% 2% 92% 3% 2%

Group C

Renovated 350 94% 2% 88% 8% 2%

Recently

rennovated

385 90% 6% 76% 10% 8%

Control 450 94% 4% 91% 4% 1%

Total 1185 93% 4% 85% 7% 3%

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 4 of 9

and group C schools an average attendance of 395). These

groups were formed in order to select adequate controls

on the basis of income,ethnicity,and school size.Each of

the groups contains one school that had LL construction

within a year before the data were collected,one school

with older LL construction (constructed two or more

years prior to the newly-renovated schoolyards) and one

school without renovated school grounds (i.e.,with no LL

construction).Children observed in this study were ele-

mentary school students, between six and eleven years old.

Children were observed using the System for Obser-

ving Play and Leisure Activity in Youth (SOPLAY).

SOPLAY is a quantitative method for evaluating levels

of physical activity of individuals and associated environ-

mentalcharacteristics in play and leisure environment

[36].Target areas are predetermined and defined as

“locations likely to provide opportunities for students to

be physically active” [37] in which observers record the

number of individuals present,their activity levels,and

their gender.Each schoolyard was divided into activity

zones that expressed the ground plane condition and

the type of activity occurring.The observation protocol

requires the identification of schoolyard variables with

the greatest impact on children’s physicalactivity based

on area type,size,and permanent improvements.Obser-

vers were trained in SOPLAY observation methodology

by a certified SOPLAY instructor.Children who are

observed to be sedentary or walking are not considered

to be physically active and children who are observed

engaging in vigorous physicalactivity or in a “primary

activity” such as using the schoolyard equipment such

as a swing or jungle gym,are considered to be physically

active.While the observers are able to distinguish

between children and adults,they were notable to

account for the age of specific children.

Observations were conducted over four days at each

schoolto obtain accurate measurements.Two obser-

vers simultaneously observed the activity area for 20%

of the totaldata collection time to test the reliability

of the data,resulting in a reliability estimate of87%.

Observers were not part of the research team to

ensure accuracy ofthe data collected.Data were col-

lected from schoolyards atparticipating elementary

schools in Denver between September 19 and October

29,2005 and between September 29 and October 19,

2006 at regular time periods before the beginning of

school,during schoolrecess,after the schoolfinished,

and during the weekends.Because the observations

covered the entire schoolyards,total schoolyard use

and the number ofchildren on the schoolyard at any

particular observation point could be estimated from

these surveys.Observationalscans capturing activity

on the entire schoolyard were treated as the unitof

analysis.Between 28 and 30 schoolyard observations

were conducted at each site.

Study Design

While utilization of the schoolyards is more or less

mandatory for the children during schoolrecess,chil-

dren may optionally use the schoolyard facilities before

or after schoolor on weekends.It is hypothesized that

by building innovative,culturally-sensitive schoolyard

facilities,more children willbe attracted to using the

schoolyard facilities,particularly during these optional

periods.In order to address this question,the number

of children observed utilizing the schoolyards before

school,during lunch recess,after school,and on week-

ends is compared across LL and non-LL schools in t-

tests.Additionally,the data were stratified by gender to

examine whether there were gender-based differences in

utilization.In order to account for the enrollment differ-

ences within the study groups,all observations are stan-

dardized against totalschoolenrollment and figures are

reported as the number ofchildren observed per 100

children enrolled (children attending the school).

Although children attending the schoolmay utilize

schoolyards,particularly on weekends,schoolyard use is

predominately by children from the school.Because the

intent of this study is to evaluate schoolyards as means

of encouraging schoolyard utilization and physical

activity among children,two different outcome measures

are reported:1) the number of children observed on the

playground and 2) the percentage of children engaged in

Table 1 Characteristics of Study and Control Schools

Ethnicity

School

Enrollment

Free &

Reduced

Lunch

African

American

Latino Anglo Asian

Group A

Renovated 336 94% 56% 41% 2% 1%

Recently

rennovated

219 88% 72% 26% 1% 1%

Control 272 91% 66% 30% 2% 2%

Total 827 91% 65% 32% 2% 1%

Group B

Renovated 605 97% - 94% 3% 3%

Recently

rennovated

492 96% 6% 88% 3% 2%

Control 579 92% - 94% 4% 2%

Total 1676 95% 2% 92% 3% 2%

Group C

Renovated 350 94% 2% 88% 8% 2%

Recently

rennovated

385 90% 6% 76% 10% 8%

Control 450 94% 4% 91% 4% 1%

Total 1185 93% 4% 85% 7% 3%

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 4 of 9

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

moderate to vigorous physicalactivity.The first measure

is intended to evaluate the impacts of LL renovation on

schoolyard utilization,while the second is intended to

estimate how schoolyards are utilized with respect to

physicalactivity.

Some previous work has indicated that renovation of

park features,such as trails [38] and playgrounds [28],

results in greater utilization.In order to examine the

specific impacts ofLLs–independent ofwhether con-

struction occurred recently–we repeated the same series

of t-tests,but compared LL schoolyards built within a

year prior to the study with those built two or more

years prior,and also separately compared both groups

of LL (recently and not-recently constructed) school-

yards to the unrenovated controls.Stratifying the sites

this way allowed us to evaluate whether utilization is

associated with the recency ofconstruction,if differ-

ences persist among older LL schoolyards,or perhaps if

observed differences are due instead to some combina-

tion of the two factors.Due to the even greater loss of

statisticalpower resulting from additionalstratification,

schools are not stratified into separate observational per-

iods for this finalanalysis.

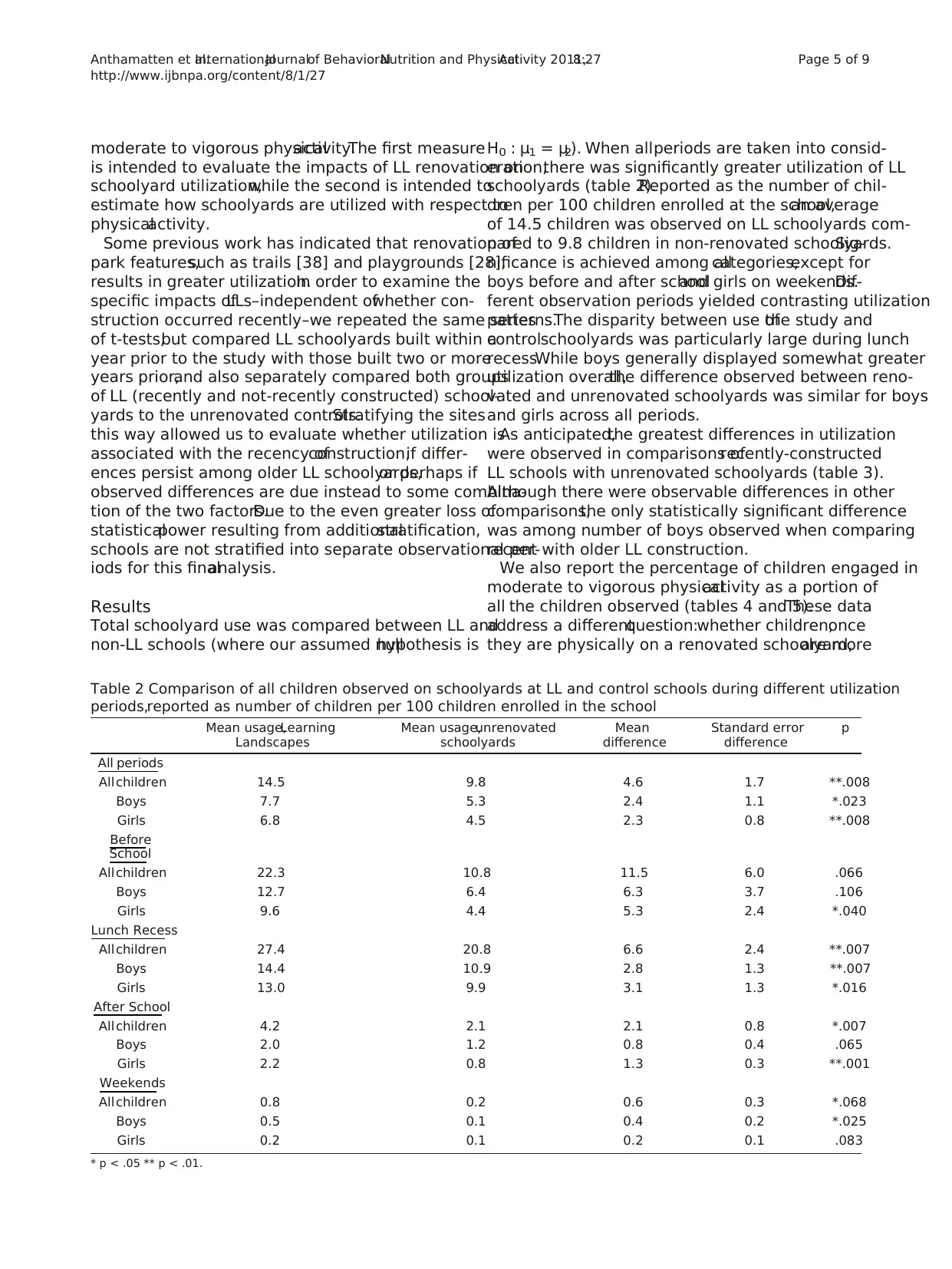

Results

Total schoolyard use was compared between LL and

non-LL schools (where our assumed nullhypothesis is

H 0 : μ1 = μ2). When allperiods are taken into consid-

eration,there was significantly greater utilization of LL

schoolyards (table 2).Reported as the number of chil-

dren per 100 children enrolled at the school,an average

of 14.5 children was observed on LL schoolyards com-

pared to 9.8 children in non-renovated schoolyards.Sig-

nificance is achieved among allcategories,except for

boys before and after schooland girls on weekends.Dif-

ferent observation periods yielded contrasting utilization

patterns.The disparity between use ofthe study and

controlschoolyards was particularly large during lunch

recess.While boys generally displayed somewhat greater

utilization overall,the difference observed between reno-

vated and unrenovated schoolyards was similar for boys

and girls across all periods.

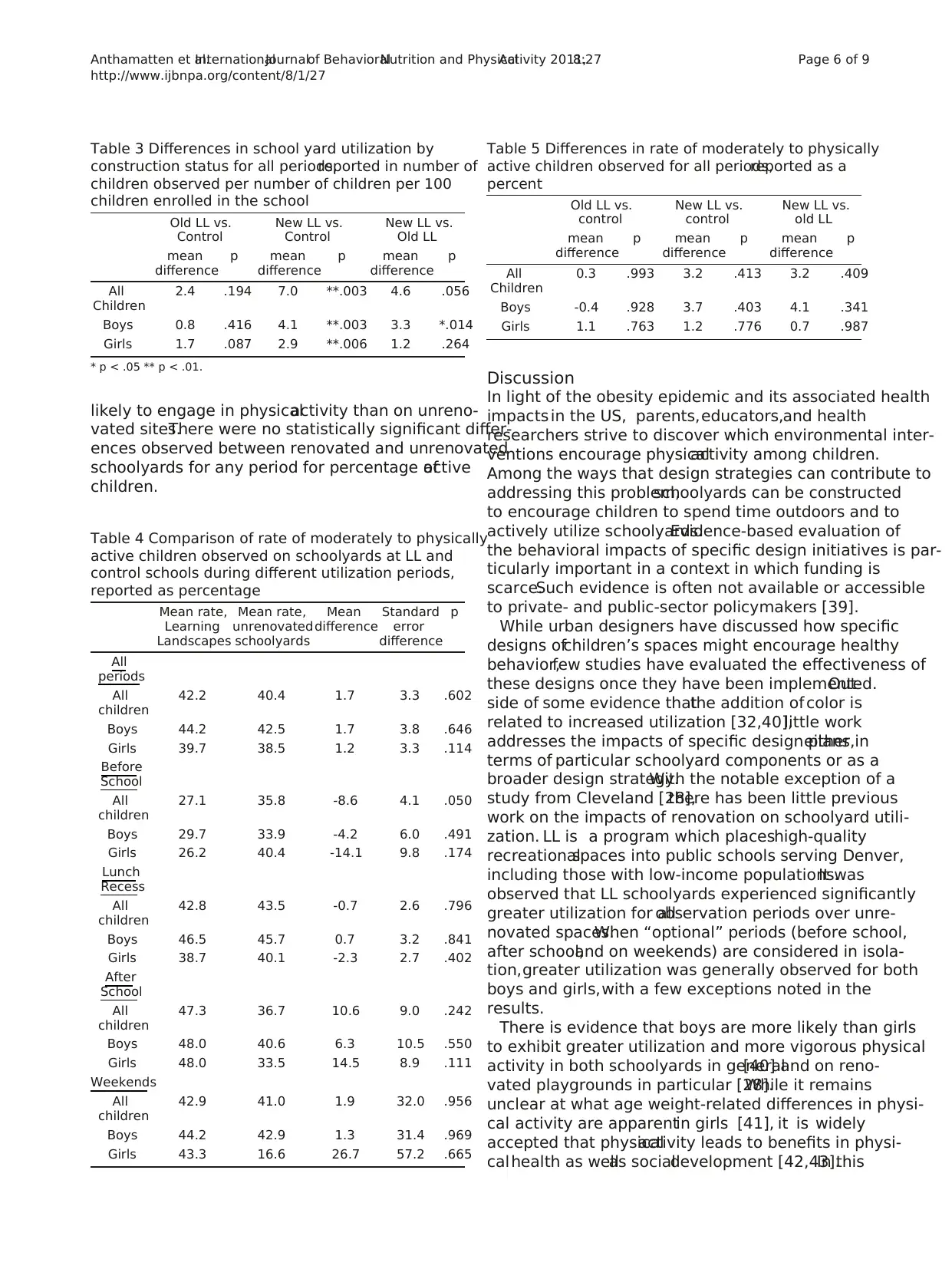

As anticipated,the greatest differences in utilization

were observed in comparisons ofrecently-constructed

LL schools with unrenovated schoolyards (table 3).

Although there were observable differences in other

comparisons,the only statistically significant difference

was among number of boys observed when comparing

recent with older LL construction.

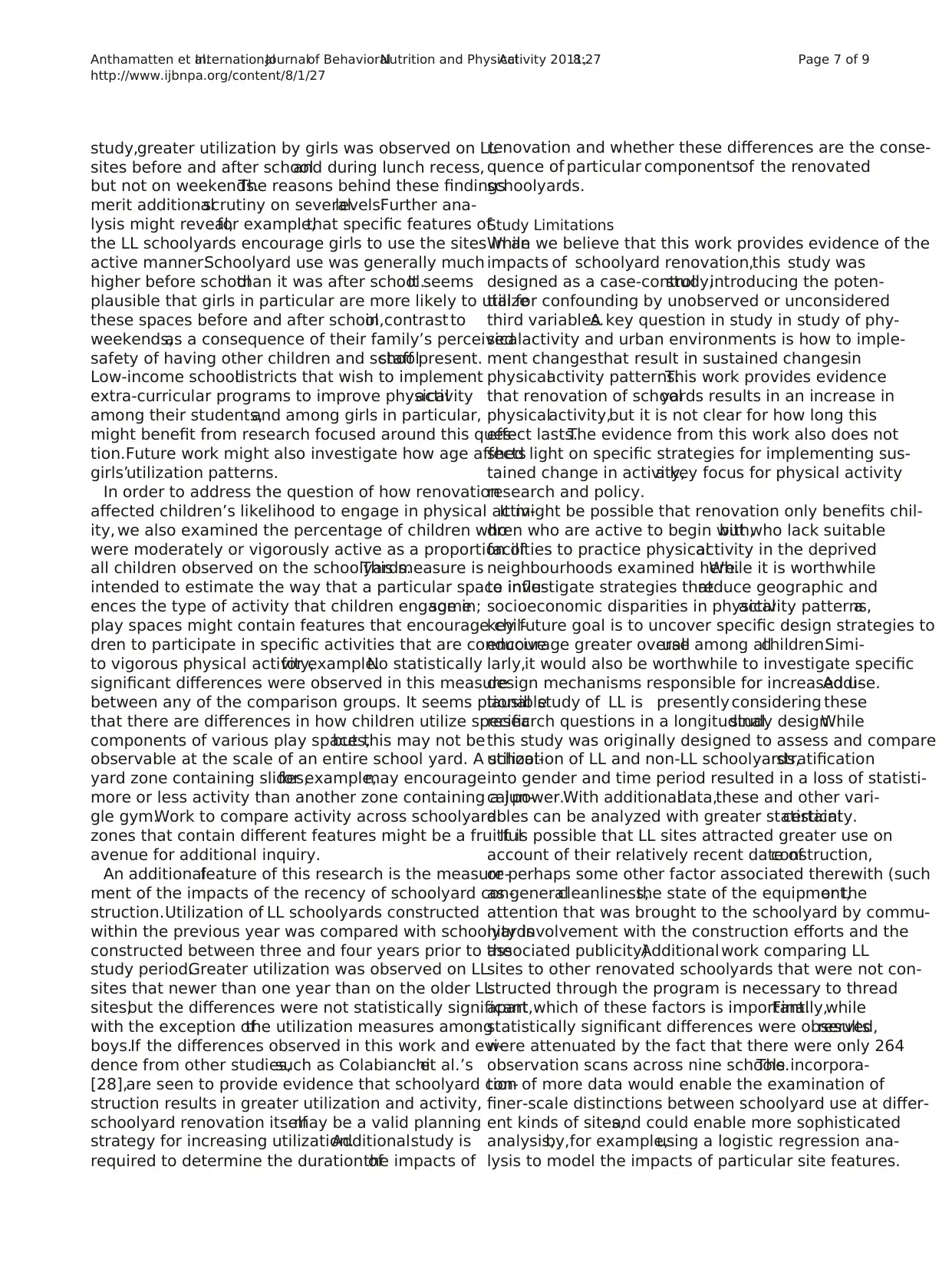

We also report the percentage of children engaged in

moderate to vigorous physicalactivity as a portion of

all the children observed (tables 4 and 5).These data

address a differentquestion:whether children,once

they are physically on a renovated schoolyard,are more

Table 2 Comparison of all children observed on schoolyards at LL and control schools during different utilization

periods,reported as number of children per 100 children enrolled in the school

Mean usage,Learning

Landscapes

Mean usage,unrenovated

schoolyards

Mean

difference

Standard error

difference

p

All periods

All children 14.5 9.8 4.6 1.7 **.008

Boys 7.7 5.3 2.4 1.1 *.023

Girls 6.8 4.5 2.3 0.8 **.008

Before

School

All children 22.3 10.8 11.5 6.0 .066

Boys 12.7 6.4 6.3 3.7 .106

Girls 9.6 4.4 5.3 2.4 *.040

Lunch Recess

All children 27.4 20.8 6.6 2.4 **.007

Boys 14.4 10.9 2.8 1.3 **.007

Girls 13.0 9.9 3.1 1.3 *.016

After School

All children 4.2 2.1 2.1 0.8 *.007

Boys 2.0 1.2 0.8 0.4 .065

Girls 2.2 0.8 1.3 0.3 **.001

Weekends

All children 0.8 0.2 0.6 0.3 *.068

Boys 0.5 0.1 0.4 0.2 *.025

Girls 0.2 0.1 0.2 0.1 .083

* p < .05 ** p < .01.

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 5 of 9

is intended to evaluate the impacts of LL renovation on

schoolyard utilization,while the second is intended to

estimate how schoolyards are utilized with respect to

physicalactivity.

Some previous work has indicated that renovation of

park features,such as trails [38] and playgrounds [28],

results in greater utilization.In order to examine the

specific impacts ofLLs–independent ofwhether con-

struction occurred recently–we repeated the same series

of t-tests,but compared LL schoolyards built within a

year prior to the study with those built two or more

years prior,and also separately compared both groups

of LL (recently and not-recently constructed) school-

yards to the unrenovated controls.Stratifying the sites

this way allowed us to evaluate whether utilization is

associated with the recency ofconstruction,if differ-

ences persist among older LL schoolyards,or perhaps if

observed differences are due instead to some combina-

tion of the two factors.Due to the even greater loss of

statisticalpower resulting from additionalstratification,

schools are not stratified into separate observational per-

iods for this finalanalysis.

Results

Total schoolyard use was compared between LL and

non-LL schools (where our assumed nullhypothesis is

H 0 : μ1 = μ2). When allperiods are taken into consid-

eration,there was significantly greater utilization of LL

schoolyards (table 2).Reported as the number of chil-

dren per 100 children enrolled at the school,an average

of 14.5 children was observed on LL schoolyards com-

pared to 9.8 children in non-renovated schoolyards.Sig-

nificance is achieved among allcategories,except for

boys before and after schooland girls on weekends.Dif-

ferent observation periods yielded contrasting utilization

patterns.The disparity between use ofthe study and

controlschoolyards was particularly large during lunch

recess.While boys generally displayed somewhat greater

utilization overall,the difference observed between reno-

vated and unrenovated schoolyards was similar for boys

and girls across all periods.

As anticipated,the greatest differences in utilization

were observed in comparisons ofrecently-constructed

LL schools with unrenovated schoolyards (table 3).

Although there were observable differences in other

comparisons,the only statistically significant difference

was among number of boys observed when comparing

recent with older LL construction.

We also report the percentage of children engaged in

moderate to vigorous physicalactivity as a portion of

all the children observed (tables 4 and 5).These data

address a differentquestion:whether children,once

they are physically on a renovated schoolyard,are more

Table 2 Comparison of all children observed on schoolyards at LL and control schools during different utilization

periods,reported as number of children per 100 children enrolled in the school

Mean usage,Learning

Landscapes

Mean usage,unrenovated

schoolyards

Mean

difference

Standard error

difference

p

All periods

All children 14.5 9.8 4.6 1.7 **.008

Boys 7.7 5.3 2.4 1.1 *.023

Girls 6.8 4.5 2.3 0.8 **.008

Before

School

All children 22.3 10.8 11.5 6.0 .066

Boys 12.7 6.4 6.3 3.7 .106

Girls 9.6 4.4 5.3 2.4 *.040

Lunch Recess

All children 27.4 20.8 6.6 2.4 **.007

Boys 14.4 10.9 2.8 1.3 **.007

Girls 13.0 9.9 3.1 1.3 *.016

After School

All children 4.2 2.1 2.1 0.8 *.007

Boys 2.0 1.2 0.8 0.4 .065

Girls 2.2 0.8 1.3 0.3 **.001

Weekends

All children 0.8 0.2 0.6 0.3 *.068

Boys 0.5 0.1 0.4 0.2 *.025

Girls 0.2 0.1 0.2 0.1 .083

* p < .05 ** p < .01.

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 5 of 9

likely to engage in physicalactivity than on unreno-

vated sites.There were no statistically significant differ-

ences observed between renovated and unrenovated

schoolyards for any period for percentage ofactive

children.

Discussion

In light of the obesity epidemic and its associated health

impacts in the US, parents,educators,and health

researchers strive to discover which environmental inter-

ventions encourage physicalactivity among children.

Among the ways that design strategies can contribute to

addressing this problem,schoolyards can be constructed

to encourage children to spend time outdoors and to

actively utilize schoolyards.Evidence-based evaluation of

the behavioral impacts of specific design initiatives is par-

ticularly important in a context in which funding is

scarce.Such evidence is often not available or accessible

to private- and public-sector policymakers [39].

While urban designers have discussed how specific

designs ofchildren’s spaces might encourage healthy

behavior,few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of

these designs once they have been implemented.Out-

side of some evidence thatthe addition of color is

related to increased utilization [32,40],little work

addresses the impacts of specific design plans,either in

terms of particular schoolyard components or as a

broader design strategy.With the notable exception of a

study from Cleveland [28],there has been little previous

work on the impacts of renovation on schoolyard utili-

zation. LL is a program which placeshigh-quality

recreationalspaces into public schools serving Denver,

including those with low-income populations.It was

observed that LL schoolyards experienced significantly

greater utilization for allobservation periods over unre-

novated spaces.When “optional” periods (before school,

after school,and on weekends) are considered in isola-

tion,greater utilization was generally observed for both

boys and girls,with a few exceptions noted in the

results.

There is evidence that boys are more likely than girls

to exhibit greater utilization and more vigorous physical

activity in both schoolyards in general[40] and on reno-

vated playgrounds in particular [28].While it remains

unclear at what age weight-related differences in physi-

cal activity are apparentin girls [41], it is widely

accepted that physicalactivity leads to benefits in physi-

calhealth as wellas socialdevelopment [42,43].In this

Table 3 Differences in school yard utilization by

construction status for all periods,reported in number of

children observed per number of children per 100

children enrolled in the school

Old LL vs.

Control

New LL vs.

Control

New LL vs.

Old LL

mean

difference

p mean

difference

p mean

difference

p

All

Children

2.4 .194 7.0 **.003 4.6 .056

Boys 0.8 .416 4.1 **.003 3.3 *.014

Girls 1.7 .087 2.9 **.006 1.2 .264

* p < .05 ** p < .01.

Table 4 Comparison of rate of moderately to physically

active children observed on schoolyards at LL and

control schools during different utilization periods,

reported as percentage

Mean rate,

Learning

Landscapes

Mean rate,

unrenovated

schoolyards

Mean

difference

Standard

error

difference

p

All

periods

All

children

42.2 40.4 1.7 3.3 .602

Boys 44.2 42.5 1.7 3.8 .646

Girls 39.7 38.5 1.2 3.3 .114

Before

School

All

children

27.1 35.8 -8.6 4.1 .050

Boys 29.7 33.9 -4.2 6.0 .491

Girls 26.2 40.4 -14.1 9.8 .174

Lunch

Recess

All

children

42.8 43.5 -0.7 2.6 .796

Boys 46.5 45.7 0.7 3.2 .841

Girls 38.7 40.1 -2.3 2.7 .402

After

School

All

children

47.3 36.7 10.6 9.0 .242

Boys 48.0 40.6 6.3 10.5 .550

Girls 48.0 33.5 14.5 8.9 .111

Weekends

All

children

42.9 41.0 1.9 32.0 .956

Boys 44.2 42.9 1.3 31.4 .969

Girls 43.3 16.6 26.7 57.2 .665

Table 5 Differences in rate of moderately to physically

active children observed for all periods,reported as a

percent

Old LL vs.

control

New LL vs.

control

New LL vs.

old LL

mean

difference

p mean

difference

p mean

difference

p

All

Children

0.3 .993 3.2 .413 3.2 .409

Boys -0.4 .928 3.7 .403 4.1 .341

Girls 1.1 .763 1.2 .776 0.7 .987

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 6 of 9

vated sites.There were no statistically significant differ-

ences observed between renovated and unrenovated

schoolyards for any period for percentage ofactive

children.

Discussion

In light of the obesity epidemic and its associated health

impacts in the US, parents,educators,and health

researchers strive to discover which environmental inter-

ventions encourage physicalactivity among children.

Among the ways that design strategies can contribute to

addressing this problem,schoolyards can be constructed

to encourage children to spend time outdoors and to

actively utilize schoolyards.Evidence-based evaluation of

the behavioral impacts of specific design initiatives is par-

ticularly important in a context in which funding is

scarce.Such evidence is often not available or accessible

to private- and public-sector policymakers [39].

While urban designers have discussed how specific

designs ofchildren’s spaces might encourage healthy

behavior,few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of

these designs once they have been implemented.Out-

side of some evidence thatthe addition of color is

related to increased utilization [32,40],little work

addresses the impacts of specific design plans,either in

terms of particular schoolyard components or as a

broader design strategy.With the notable exception of a

study from Cleveland [28],there has been little previous

work on the impacts of renovation on schoolyard utili-

zation. LL is a program which placeshigh-quality

recreationalspaces into public schools serving Denver,

including those with low-income populations.It was

observed that LL schoolyards experienced significantly

greater utilization for allobservation periods over unre-

novated spaces.When “optional” periods (before school,

after school,and on weekends) are considered in isola-

tion,greater utilization was generally observed for both

boys and girls,with a few exceptions noted in the

results.

There is evidence that boys are more likely than girls

to exhibit greater utilization and more vigorous physical

activity in both schoolyards in general[40] and on reno-

vated playgrounds in particular [28].While it remains

unclear at what age weight-related differences in physi-

cal activity are apparentin girls [41], it is widely

accepted that physicalactivity leads to benefits in physi-

calhealth as wellas socialdevelopment [42,43].In this

Table 3 Differences in school yard utilization by

construction status for all periods,reported in number of

children observed per number of children per 100

children enrolled in the school

Old LL vs.

Control

New LL vs.

Control

New LL vs.

Old LL

mean

difference

p mean

difference

p mean

difference

p

All

Children

2.4 .194 7.0 **.003 4.6 .056

Boys 0.8 .416 4.1 **.003 3.3 *.014

Girls 1.7 .087 2.9 **.006 1.2 .264

* p < .05 ** p < .01.

Table 4 Comparison of rate of moderately to physically

active children observed on schoolyards at LL and

control schools during different utilization periods,

reported as percentage

Mean rate,

Learning

Landscapes

Mean rate,

unrenovated

schoolyards

Mean

difference

Standard

error

difference

p

All

periods

All

children

42.2 40.4 1.7 3.3 .602

Boys 44.2 42.5 1.7 3.8 .646

Girls 39.7 38.5 1.2 3.3 .114

Before

School

All

children

27.1 35.8 -8.6 4.1 .050

Boys 29.7 33.9 -4.2 6.0 .491

Girls 26.2 40.4 -14.1 9.8 .174

Lunch

Recess

All

children

42.8 43.5 -0.7 2.6 .796

Boys 46.5 45.7 0.7 3.2 .841

Girls 38.7 40.1 -2.3 2.7 .402

After

School

All

children

47.3 36.7 10.6 9.0 .242

Boys 48.0 40.6 6.3 10.5 .550

Girls 48.0 33.5 14.5 8.9 .111

Weekends

All

children

42.9 41.0 1.9 32.0 .956

Boys 44.2 42.9 1.3 31.4 .969

Girls 43.3 16.6 26.7 57.2 .665

Table 5 Differences in rate of moderately to physically

active children observed for all periods,reported as a

percent

Old LL vs.

control

New LL vs.

control

New LL vs.

old LL

mean

difference

p mean

difference

p mean

difference

p

All

Children

0.3 .993 3.2 .413 3.2 .409

Boys -0.4 .928 3.7 .403 4.1 .341

Girls 1.1 .763 1.2 .776 0.7 .987

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 6 of 9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

study,greater utilization by girls was observed on LL

sites before and after schooland during lunch recess,

but not on weekends.The reasons behind these findings

merit additionalscrutiny on severallevels.Further ana-

lysis might reveal,for example,that specific features of

the LL schoolyards encourage girls to use the sites in an

active manner.Schoolyard use was generally much

higher before schoolthan it was after school.It seems

plausible that girls in particular are more likely to utilize

these spaces before and after school,in contrast to

weekends,as a consequence of their family’s perceived

safety of having other children and schoolstaff present.

Low-income schooldistricts that wish to implement

extra-curricular programs to improve physicalactivity

among their students,and among girls in particular,

might benefit from research focused around this ques-

tion.Future work might also investigate how age affects

girls’utilization patterns.

In order to address the question of how renovation

affected children’s likelihood to engage in physical activ-

ity, we also examined the percentage of children who

were moderately or vigorously active as a proportion of

all children observed on the schoolyards.This measure is

intended to estimate the way that a particular space influ-

ences the type of activity that children engage in;some

play spaces might contain features that encourage chil-

dren to participate in specific activities that are conducive

to vigorous physical activity,for example.No statistically

significant differences were observed in this measure

between any of the comparison groups. It seems plausible

that there are differences in how children utilize specific

components of various play spaces,but this may not be

observable at the scale of an entire school yard. A school-

yard zone containing slides,for example,may encourage

more or less activity than another zone containing a jun-

gle gym.Work to compare activity across schoolyard

zones that contain different features might be a fruitful

avenue for additional inquiry.

An additionalfeature of this research is the measure-

ment of the impacts of the recency of schoolyard con-

struction.Utilization of LL schoolyards constructed

within the previous year was compared with schoolyards

constructed between three and four years prior to the

study period.Greater utilization was observed on LL

sites that newer than one year than on the older LL

sites,but the differences were not statistically significant,

with the exception ofthe utilization measures among

boys.If the differences observed in this work and evi-

dence from other studies,such as Colabianchiet al.’s

[28],are seen to provide evidence that schoolyard con-

struction results in greater utilization and activity,

schoolyard renovation itselfmay be a valid planning

strategy for increasing utilization.Additionalstudy is

required to determine the duration ofthe impacts of

renovation and whether these differences are the conse-

quence of particular componentsof the renovated

schoolyards.

Study Limitations

While we believe that this work provides evidence of the

impacts of schoolyard renovation,this study was

designed as a case-controlstudy,introducing the poten-

tial for confounding by unobserved or unconsidered

third variables.A key question in study in study of phy-

sicalactivity and urban environments is how to imple-

ment changesthat result in sustained changesin

physicalactivity patterns.This work provides evidence

that renovation of schoolyards results in an increase in

physicalactivity,but it is not clear for how long this

effect lasts.The evidence from this work also does not

shed light on specific strategies for implementing sus-

tained change in activity,a key focus for physical activity

research and policy.

It might be possible that renovation only benefits chil-

dren who are active to begin with,but who lack suitable

facilities to practice physicalactivity in the deprived

neighbourhoods examined here.While it is worthwhile

to investigate strategies thatreduce geographic and

socioeconomic disparities in physicalactivity patterns,a

key future goal is to uncover specific design strategies to

encourage greater overalluse among allchildren.Simi-

larly,it would also be worthwhile to investigate specific

design mechanisms responsible for increased use.Addi-

tional study of LL is presently considering these

research questions in a longitudinalstudy design.While

this study was originally designed to assess and compare

utilization of LL and non-LL schoolyards,stratification

into gender and time period resulted in a loss of statisti-

cal power.With additionaldata,these and other vari-

ables can be analyzed with greater statisticalcertainty.

It is possible that LL sites attracted greater use on

account of their relatively recent date ofconstruction,

or perhaps some other factor associated therewith (such

as generalcleanliness,the state of the equipment,or the

attention that was brought to the schoolyard by commu-

nity involvement with the construction efforts and the

associated publicity).Additional work comparing LL

sites to other renovated schoolyards that were not con-

structed through the program is necessary to thread

apart which of these factors is important.Finally,while

statistically significant differences were observed,results

were attenuated by the fact that there were only 264

observation scans across nine schools.The incorpora-

tion of more data would enable the examination of

finer-scale distinctions between schoolyard use at differ-

ent kinds of sites,and could enable more sophisticated

analysis,by,for example,using a logistic regression ana-

lysis to model the impacts of particular site features.

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 7 of 9

sites before and after schooland during lunch recess,

but not on weekends.The reasons behind these findings

merit additionalscrutiny on severallevels.Further ana-

lysis might reveal,for example,that specific features of

the LL schoolyards encourage girls to use the sites in an

active manner.Schoolyard use was generally much

higher before schoolthan it was after school.It seems

plausible that girls in particular are more likely to utilize

these spaces before and after school,in contrast to

weekends,as a consequence of their family’s perceived

safety of having other children and schoolstaff present.

Low-income schooldistricts that wish to implement

extra-curricular programs to improve physicalactivity

among their students,and among girls in particular,

might benefit from research focused around this ques-

tion.Future work might also investigate how age affects

girls’utilization patterns.

In order to address the question of how renovation

affected children’s likelihood to engage in physical activ-

ity, we also examined the percentage of children who

were moderately or vigorously active as a proportion of

all children observed on the schoolyards.This measure is

intended to estimate the way that a particular space influ-

ences the type of activity that children engage in;some

play spaces might contain features that encourage chil-

dren to participate in specific activities that are conducive

to vigorous physical activity,for example.No statistically

significant differences were observed in this measure

between any of the comparison groups. It seems plausible

that there are differences in how children utilize specific

components of various play spaces,but this may not be

observable at the scale of an entire school yard. A school-

yard zone containing slides,for example,may encourage

more or less activity than another zone containing a jun-

gle gym.Work to compare activity across schoolyard

zones that contain different features might be a fruitful

avenue for additional inquiry.

An additionalfeature of this research is the measure-

ment of the impacts of the recency of schoolyard con-

struction.Utilization of LL schoolyards constructed

within the previous year was compared with schoolyards

constructed between three and four years prior to the

study period.Greater utilization was observed on LL

sites that newer than one year than on the older LL

sites,but the differences were not statistically significant,

with the exception ofthe utilization measures among

boys.If the differences observed in this work and evi-

dence from other studies,such as Colabianchiet al.’s

[28],are seen to provide evidence that schoolyard con-

struction results in greater utilization and activity,

schoolyard renovation itselfmay be a valid planning

strategy for increasing utilization.Additionalstudy is

required to determine the duration ofthe impacts of

renovation and whether these differences are the conse-

quence of particular componentsof the renovated

schoolyards.

Study Limitations

While we believe that this work provides evidence of the

impacts of schoolyard renovation,this study was

designed as a case-controlstudy,introducing the poten-

tial for confounding by unobserved or unconsidered

third variables.A key question in study in study of phy-

sicalactivity and urban environments is how to imple-

ment changesthat result in sustained changesin

physicalactivity patterns.This work provides evidence

that renovation of schoolyards results in an increase in

physicalactivity,but it is not clear for how long this

effect lasts.The evidence from this work also does not

shed light on specific strategies for implementing sus-

tained change in activity,a key focus for physical activity

research and policy.

It might be possible that renovation only benefits chil-

dren who are active to begin with,but who lack suitable

facilities to practice physicalactivity in the deprived

neighbourhoods examined here.While it is worthwhile

to investigate strategies thatreduce geographic and

socioeconomic disparities in physicalactivity patterns,a

key future goal is to uncover specific design strategies to

encourage greater overalluse among allchildren.Simi-

larly,it would also be worthwhile to investigate specific

design mechanisms responsible for increased use.Addi-

tional study of LL is presently considering these

research questions in a longitudinalstudy design.While

this study was originally designed to assess and compare

utilization of LL and non-LL schoolyards,stratification

into gender and time period resulted in a loss of statisti-

cal power.With additionaldata,these and other vari-

ables can be analyzed with greater statisticalcertainty.

It is possible that LL sites attracted greater use on

account of their relatively recent date ofconstruction,

or perhaps some other factor associated therewith (such

as generalcleanliness,the state of the equipment,or the

attention that was brought to the schoolyard by commu-

nity involvement with the construction efforts and the

associated publicity).Additional work comparing LL

sites to other renovated schoolyards that were not con-

structed through the program is necessary to thread

apart which of these factors is important.Finally,while

statistically significant differences were observed,results

were attenuated by the fact that there were only 264

observation scans across nine schools.The incorpora-

tion of more data would enable the examination of

finer-scale distinctions between schoolyard use at differ-

ent kinds of sites,and could enable more sophisticated

analysis,by,for example,using a logistic regression ana-

lysis to model the impacts of particular site features.

Anthamatten et al.InternationalJournalof BehavioralNutrition and PhysicalActivity 2011,8:27

http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/8/1/27

Page 7 of 9

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Conclusions

While encouraging physicalactivity among children is

an important public health goalthat may be addressed

through a carefulplanning and design process,it is

essentialthat specific strategies be explored and evalu-

ated in order to determine how and to whatextent

these strategies encourage physicalactivity among chil-

dren.This study provides evidence that schoolyard reno-

vation from Learning Landscapesincreasesactive

utilization by schoolchildren during both mandatory

and optionalplay periods,contributing to a nascent

body of work [28,44] that suggests that such renovation

may be an effective method to encouraging physical

activity among children.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson

Foundation.

Author details

1Department of Geography and EnvironmentalSciences,University of

Colorado Denver,Denver,CO,USA.2Department of Landscape Architecture,

University of Colorado Denver,Denver,CO,USA.3Colorado Center for

Community Development,College of Architecture and Planning,University

of Colorado Denver,Denver,CO,USA.4Adams County Youth Initiative,

Denver,CO,USA.5Department of Public Health Sciences,University of