Complex Project Management as Complex Problem Solving Report

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/20

|12

|13247

|69

Report

AI Summary

This report examines complex project management, particularly focusing on how it can be understood as complex problem solving. The study draws from an empirical investigation of two Irish state-owned organizations, highlighting the importance of knowledge management under uncertainty. The paper proposes that a 'common will of mutual interest' is a key mechanism for coordinating emergent knowledge in complex projects, fostered around project goals and paced by the project life cycle. The report reviews literature on complex PM, contrasting traditional and pragmatist perspectives, and discusses implications for governance, planning, leadership, and knowledge transfer. The research emphasizes the need for distributed governance approaches to manage incomplete pre-given knowledge and coordinate emergent knowledge, advocating for a shift from 'total planning' to 'bounded planning' in complex project environments. The study emphasizes the importance of fostering a team spirit to the extent that it becomes self-reproducing as a common will around an interest that is mutually desired and experienced.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306344720

Complex project management as complex problem solving: A distributed

knowledge management perspective

Article in International Journal of Project Management · December 2014

DOI: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.06.007

CITATIONS

38

READS

1,016

3 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

CACTOS - Context Aware Cloud Topology Optimisation and SimulationView project

SIMCT - Simulation-based Contract Costing for Outsourcing EnterprisesView project

Terence Ahern

Dublin City University

5 PUBLICATIONS71CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

P. J. Byrne

Dublin City University

82PUBLICATIONS865CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Complex project management as complex problem solving: A distributed

knowledge management perspective

Article in International Journal of Project Management · December 2014

DOI: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.06.007

CITATIONS

38

READS

1,016

3 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

CACTOS - Context Aware Cloud Topology Optimisation and SimulationView project

SIMCT - Simulation-based Contract Costing for Outsourcing EnterprisesView project

Terence Ahern

Dublin City University

5 PUBLICATIONS71CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

P. J. Byrne

Dublin City University

82PUBLICATIONS865CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Complex project management as complex problem solving:

A distributed knowledge management perspective

Terence Ahern⁎, Brian Leavy, P.J. Byrne

Dublin City University Business School, Dublin City University, Ireland

Available online 2 July 2013

Abstract

Traditional project management (PM) privileges planning and downplays the role of learning even in more complex proj

paper draws inspiration from two organisations that were found to have developed complex PM expertise as a form of com

(CPS), a practice with implicit learning because complex projects are unable to be completely specified in advance (Hayek

view of complex projectmanagementas a form of complex problem solving is the governance challenge of knowledge managemunder

uncertainty. This paper proposes that the distributed coordination mechanism which both organisations evolved for this co

be characterised as a ‘common willof mutualinterest’,a self-organising process thatwas fostered around projectgoals and paced by the

project life cycle (Kogut and Zander, 1992). The implications for theory, research, and practice in complex PM knowledge m

examined.

© 2013 Elsevier Ltd. APM and IPMA. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Complex project management; Distributed knowledge management; Bounded planning; Problem solving; Common will

1. Introduction

In the project management (PM) literature, the management of

complex projectsas an importantfocusfor more intensive

research isan emerging tradition,along with theneed to

understand the particular governance challenges associated with

it (Baccarini, 1996; Miller and Hobbs, 2005; Morris and Hough,

1987;Müller, 2009).This researchpaperhighlightsand

examines knowledge management as a key aspect of governance

in the case of complex projects, based on an empirical study of

complex projectmanagementfeaturing two Irish state-owned

organisations, referred to here as GovCo-1 and GovCo-2. In the

late 1990s and early 2000s, each of these complex organisations

(Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2000; Thompson, 1967) was challenged

to take on major infrastructural development projects of a scale

and complexity well beyond what had been the norm for

organisation up to then. In GovCo-1, the stimulus was pro

by the government's National Development Plans for infr

ture investment (NDP, 2000, 2007) and the stimulus for G

was provided through EU deregulation in the energy sectIn

this context,GovCo 1&2 provided a valuable opportunity to

explore more closely in what ways the management of ‘c

projects differs most from that of other kinds of projects r

in the mainstream PM literature (APM, 2011, 2012; PMI, 2

The main empiricalfindingwas that complexproject

management(PM), as manifested in thetwo organisations

understudy,could bestbe understood as a form of complex

problem solving (CPS)thatdoesnot lend itselfto being

completelyspecifiablein advance.In the mainstream PM

literature,such projects undertaken by GovCo 1&2 tend to

viewed asjustmore ‘complicated’projects thatcan stillbe

planned and managed in the traditional way as “the appl

of knowledge,skills,tools,and techniques to projectactivities

to meet the project requirements” (PMI, 2013, p. 5, italics

In this approach,there is little learning anticipated beyond

the application of prior knowledge.In contrast,the empirical

finding that complex PM is a form of complex problem so

⁎ Corresponding author at: Dublin City University Business School, Dublin

City University, Ireland. Tel.: + 353 1 7031752.

E-mail addresses: terence.ahern3@mail.dcu.ie (T. Ahern),

brian.leavy@dcu.ie (B. Leavy), pj.byrne@dcu.ie (P.J. Byrne).

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijproman

0263-7863/$36.00 © 2013 Elsevier Ltd. APM and IPMA. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.06.007

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371 – 1381

A distributed knowledge management perspective

Terence Ahern⁎, Brian Leavy, P.J. Byrne

Dublin City University Business School, Dublin City University, Ireland

Available online 2 July 2013

Abstract

Traditional project management (PM) privileges planning and downplays the role of learning even in more complex proj

paper draws inspiration from two organisations that were found to have developed complex PM expertise as a form of com

(CPS), a practice with implicit learning because complex projects are unable to be completely specified in advance (Hayek

view of complex projectmanagementas a form of complex problem solving is the governance challenge of knowledge managemunder

uncertainty. This paper proposes that the distributed coordination mechanism which both organisations evolved for this co

be characterised as a ‘common willof mutualinterest’,a self-organising process thatwas fostered around projectgoals and paced by the

project life cycle (Kogut and Zander, 1992). The implications for theory, research, and practice in complex PM knowledge m

examined.

© 2013 Elsevier Ltd. APM and IPMA. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Complex project management; Distributed knowledge management; Bounded planning; Problem solving; Common will

1. Introduction

In the project management (PM) literature, the management of

complex projectsas an importantfocusfor more intensive

research isan emerging tradition,along with theneed to

understand the particular governance challenges associated with

it (Baccarini, 1996; Miller and Hobbs, 2005; Morris and Hough,

1987;Müller, 2009).This researchpaperhighlightsand

examines knowledge management as a key aspect of governance

in the case of complex projects, based on an empirical study of

complex projectmanagementfeaturing two Irish state-owned

organisations, referred to here as GovCo-1 and GovCo-2. In the

late 1990s and early 2000s, each of these complex organisations

(Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2000; Thompson, 1967) was challenged

to take on major infrastructural development projects of a scale

and complexity well beyond what had been the norm for

organisation up to then. In GovCo-1, the stimulus was pro

by the government's National Development Plans for infr

ture investment (NDP, 2000, 2007) and the stimulus for G

was provided through EU deregulation in the energy sectIn

this context,GovCo 1&2 provided a valuable opportunity to

explore more closely in what ways the management of ‘c

projects differs most from that of other kinds of projects r

in the mainstream PM literature (APM, 2011, 2012; PMI, 2

The main empiricalfindingwas that complexproject

management(PM), as manifested in thetwo organisations

understudy,could bestbe understood as a form of complex

problem solving (CPS)thatdoesnot lend itselfto being

completelyspecifiablein advance.In the mainstream PM

literature,such projects undertaken by GovCo 1&2 tend to

viewed asjustmore ‘complicated’projects thatcan stillbe

planned and managed in the traditional way as “the appl

of knowledge,skills,tools,and techniques to projectactivities

to meet the project requirements” (PMI, 2013, p. 5, italics

In this approach,there is little learning anticipated beyond

the application of prior knowledge.In contrast,the empirical

finding that complex PM is a form of complex problem so

⁎ Corresponding author at: Dublin City University Business School, Dublin

City University, Ireland. Tel.: + 353 1 7031752.

E-mail addresses: terence.ahern3@mail.dcu.ie (T. Ahern),

brian.leavy@dcu.ie (B. Leavy), pj.byrne@dcu.ie (P.J. Byrne).

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijproman

0263-7863/$36.00 © 2013 Elsevier Ltd. APM and IPMA. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.06.007

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371 – 1381

(CPS) means that managing project knowledge becomes more

problematic.

In terms of governance,this alternative perspective means

that a central aspect of knowledge management in complex PM

settingsinvolvesmanaging intrinsic knowledge uncertainty.

This is manifest as incomplete pre-given knowledge in complex

projectsthat necessarilylimits complexPM to ‘bounded

planning’,which implies the need in complexPM to

continuously create knowledge over the project life cycle that

is notspecifiable atthe outset(Engwall,2002).This,in turn,

requiresthe developmentof an effectivemechanism for

coordinating this emergent knowledge.In the cases of GovCo

1&2, both were found to have evolved a distributed governance

approach to knowledgemanagementthatrevolved around

problem solving as a mode of learning and organising. In effect,

in order to create project knowledge that was unspecifiable at

the outsetin projectdesigns,plans,etc.,the projectteam

became a community of learners that was learning the project

though organisational CPS. In order to coordinate this emergent

knowledge,GovCo 1&2 harnessed the agency ofwhatthis

papertermsa ‘common willof mutualinterest’thatwas

fostered around projectgoals and paced by the projectlife

cycle.This can be thoughtof as a high-levelorganising

principle that is irreducible to individual project actors (Kogut

and Zander, 1992), by which the project team can know more

than itcan tell(Polanyi,1967)and can know more than its

individual members can know separately.

The full empiricalinquiry thatled to these findingsis

reported elsewhere (Ahern, 2013), which is an exploratory case

study investigation of two complex organisations in the public

sector using a Contextualist research perspective that includes

51 semi-structured interviews (Pepper, 1942). This longitudinal

process approach facilitates the study ofthe developmentof

organisationalprocesses thatare ‘in flight’ during periods of

importantchangein organisations(Pettigrew,1990,1997,

2012). The primary purpose of this paper is to examine some of

the main conceptualand practicalimplicationsfor the

traditionalPM literatureassociatedwith the abovetwo

importantempiricalinsights in complex PM,namely,incom-

plete pre-given knowledge and coordinating emergentknowl-

edge.This will be done by reviewing the literature on related

themesand drawingon furtherfindingsfrom the data

(Siggelkow, 2007).

The remainderof the paperis organisedas follows:

Section 2 reviews the literature on complex PM with particular

attention to the contrastin knowledge managementassump-

tions between traditionalPM and those implied by viewing

complex PM as complex problem solving (CPS).In addition,

learning modesare reviewed forgenerating knowledgein

complex PM,which can be coordinated through a distributed

organising approach.Section 3 discusses the implications for

governance in complex PM ofknowledge managementas a

process of learning and organising under ‘bounded planning’

ratherthan ‘totalplanning’assumptions.This includesthe

scaffoldingof distributedlearningand organisingusing

documented procedures as well as the fostering and pacing of

a common willof mutualinterestfor coordinating emergent

projectknowledge.In Section 4,the concluding section,the

implicationsof inherentknowledge uncertainty in complex

PM as a form of organisationalCPS are discussed in relation

to the following areas of research and practice:(i) planning,

knowledge creation,and knowledge coordination;(ii) leader-

ship; (iii) knowledge transfer; and (iv) PM complexity.

2. Complex project management as complex problem solvi

Informed by the two empirical findings highlighted earlie

section will review the literature on complex projects in rela

the managementof knowledgeunderthe traditionalPM

paradigm,which assumes full pre-given knowledge,and under

more recent pragmatist perspectives of PM, which accept t

of incomplete pre-given knowledge in projects and the nee

learning. In this, a distinction will be made between ‘compl

projectsthatcan be completelyspecifiedin advanceand

‘complex’ projects that are unable to be completely specifi

advance. Finally, different modes of problem solving learnin

discussed,including complex PM as a form of organisational

CPS, which facilitates the creation of emergent knowledge

un-specifiable at the outset; and the coordination of this em

knowledge through whatthis paperterms a ‘common willof

mutual interest’ as a distributed tacit dimension. This term

to the literature and is inspired by an interaction between t

study data and the literature to representthe synergy thatis

achieved in projects when a team spirit is successfully foste

the extentthatit becomes self-reproducing as a common will

around an interest that is mutually desired and experience

way,it becomes a self-organising process for coordinating t

behaviour and, hence, the collective learning of project tea

complex PM settings.

2.1. Complex PM as applied science — planned knowledge

In early work on the complexity of project settings, Shen

al.(1995) distinguish two dimensions of projectcomplexity—

‘technological uncertainty’ and ‘system scope’. This typolo

used in advocating a contingency approach to PM (Lawrenc

and Lorsch,1967;Shenhar,1998,2001;Shenharand Dvir,

1996), rather than the “one size fits all” approach of traditi

PM (Shenhar,2001,p. 394).In subsequentresearch,Shenhar

et al. (2002)extend the framework to encompassthree di-

mensions of projectcomplexity,namely,‘uncertainty’,‘pace’,

and ‘complexity/scope’ (UPC Model), where ‘pace’ is added

reflectthe “speed and criticality of time goals” (ibid.,p. 101).

Implicit in this research is the assumption that knowledge r

to projectcomplexity can be analysed and integrated as ‘tec

nical’ complexity underthe normsof technicalrationality

(Ashby, 1956; Cleland and King, 1968; von Bertalanffy, 195

rather than as ‘social’ complexity that requires a socio-tech

approach (Davies and Hobday,2005;Nightingale and Brady,

2011; Sapolsky, 1972; Williams, 1999, 2005). Under the for

approach, knowledge is detached from the knowing subjec

commodity and is pre-given at the outset, while, under the

knowledge is integrated with the knower as a process of kn

over time, because it is not completely pre-given at the ou

1372 T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

problematic.

In terms of governance,this alternative perspective means

that a central aspect of knowledge management in complex PM

settingsinvolvesmanaging intrinsic knowledge uncertainty.

This is manifest as incomplete pre-given knowledge in complex

projectsthat necessarilylimits complexPM to ‘bounded

planning’,which implies the need in complexPM to

continuously create knowledge over the project life cycle that

is notspecifiable atthe outset(Engwall,2002).This,in turn,

requiresthe developmentof an effectivemechanism for

coordinating this emergent knowledge.In the cases of GovCo

1&2, both were found to have evolved a distributed governance

approach to knowledgemanagementthatrevolved around

problem solving as a mode of learning and organising. In effect,

in order to create project knowledge that was unspecifiable at

the outsetin projectdesigns,plans,etc.,the projectteam

became a community of learners that was learning the project

though organisational CPS. In order to coordinate this emergent

knowledge,GovCo 1&2 harnessed the agency ofwhatthis

papertermsa ‘common willof mutualinterest’thatwas

fostered around projectgoals and paced by the projectlife

cycle.This can be thoughtof as a high-levelorganising

principle that is irreducible to individual project actors (Kogut

and Zander, 1992), by which the project team can know more

than itcan tell(Polanyi,1967)and can know more than its

individual members can know separately.

The full empiricalinquiry thatled to these findingsis

reported elsewhere (Ahern, 2013), which is an exploratory case

study investigation of two complex organisations in the public

sector using a Contextualist research perspective that includes

51 semi-structured interviews (Pepper, 1942). This longitudinal

process approach facilitates the study ofthe developmentof

organisationalprocesses thatare ‘in flight’ during periods of

importantchangein organisations(Pettigrew,1990,1997,

2012). The primary purpose of this paper is to examine some of

the main conceptualand practicalimplicationsfor the

traditionalPM literatureassociatedwith the abovetwo

importantempiricalinsights in complex PM,namely,incom-

plete pre-given knowledge and coordinating emergentknowl-

edge.This will be done by reviewing the literature on related

themesand drawingon furtherfindingsfrom the data

(Siggelkow, 2007).

The remainderof the paperis organisedas follows:

Section 2 reviews the literature on complex PM with particular

attention to the contrastin knowledge managementassump-

tions between traditionalPM and those implied by viewing

complex PM as complex problem solving (CPS).In addition,

learning modesare reviewed forgenerating knowledgein

complex PM,which can be coordinated through a distributed

organising approach.Section 3 discusses the implications for

governance in complex PM ofknowledge managementas a

process of learning and organising under ‘bounded planning’

ratherthan ‘totalplanning’assumptions.This includesthe

scaffoldingof distributedlearningand organisingusing

documented procedures as well as the fostering and pacing of

a common willof mutualinterestfor coordinating emergent

projectknowledge.In Section 4,the concluding section,the

implicationsof inherentknowledge uncertainty in complex

PM as a form of organisationalCPS are discussed in relation

to the following areas of research and practice:(i) planning,

knowledge creation,and knowledge coordination;(ii) leader-

ship; (iii) knowledge transfer; and (iv) PM complexity.

2. Complex project management as complex problem solvi

Informed by the two empirical findings highlighted earlie

section will review the literature on complex projects in rela

the managementof knowledgeunderthe traditionalPM

paradigm,which assumes full pre-given knowledge,and under

more recent pragmatist perspectives of PM, which accept t

of incomplete pre-given knowledge in projects and the nee

learning. In this, a distinction will be made between ‘compl

projectsthatcan be completelyspecifiedin advanceand

‘complex’ projects that are unable to be completely specifi

advance. Finally, different modes of problem solving learnin

discussed,including complex PM as a form of organisational

CPS, which facilitates the creation of emergent knowledge

un-specifiable at the outset; and the coordination of this em

knowledge through whatthis paperterms a ‘common willof

mutual interest’ as a distributed tacit dimension. This term

to the literature and is inspired by an interaction between t

study data and the literature to representthe synergy thatis

achieved in projects when a team spirit is successfully foste

the extentthatit becomes self-reproducing as a common will

around an interest that is mutually desired and experience

way,it becomes a self-organising process for coordinating t

behaviour and, hence, the collective learning of project tea

complex PM settings.

2.1. Complex PM as applied science — planned knowledge

In early work on the complexity of project settings, Shen

al.(1995) distinguish two dimensions of projectcomplexity—

‘technological uncertainty’ and ‘system scope’. This typolo

used in advocating a contingency approach to PM (Lawrenc

and Lorsch,1967;Shenhar,1998,2001;Shenharand Dvir,

1996), rather than the “one size fits all” approach of traditi

PM (Shenhar,2001,p. 394).In subsequentresearch,Shenhar

et al. (2002)extend the framework to encompassthree di-

mensions of projectcomplexity,namely,‘uncertainty’,‘pace’,

and ‘complexity/scope’ (UPC Model), where ‘pace’ is added

reflectthe “speed and criticality of time goals” (ibid.,p. 101).

Implicit in this research is the assumption that knowledge r

to projectcomplexity can be analysed and integrated as ‘tec

nical’ complexity underthe normsof technicalrationality

(Ashby, 1956; Cleland and King, 1968; von Bertalanffy, 195

rather than as ‘social’ complexity that requires a socio-tech

approach (Davies and Hobday,2005;Nightingale and Brady,

2011; Sapolsky, 1972; Williams, 1999, 2005). Under the for

approach, knowledge is detached from the knowing subjec

commodity and is pre-given at the outset, while, under the

knowledge is integrated with the knower as a process of kn

over time, because it is not completely pre-given at the ou

1372 T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

In recentliterature on complex PM,scholars have soughtto

incorporate insightsfrom research in complexity,chaos,self-

organising,and evolution with traditional PM (Cooke-Davies et

al., 2007; Geraldi et al., 2011). This emerging area in PM is termed

‘complex projectmanagement’ (Whitty and Maylor,2009).For

example,Saynisch (2010a,b) analyses complexity using the two

dimensions of ‘project complexity’ and ‘environmental complex-

ity’ and calls for a governance approach thatintegrates the two

cybernetic cyclesof traditionalPM and the managementof

complexity (evolution, self-organisation, edge of chaos). Interest-

ingly, he maintains that getting the balance right between these two

“will be the future management art” (Saynisch, 2010b, p. 8, italics

added),which suggests that,in order to dealwith situations of

project complexity, PM may have to reposition its self-image to

one of a craft with implied learning rather than an applied science

under the traditional PM paradigm with little learning anticipated

(Mintzberg, 1979, 1987).

2.2. ComplexPM as organisationalpractice— emergent

knowledge

In a paperthatrecognises the limitations ofthe planned

approachesof traditionalPM in complex projectsettings,

Berggren etal. (2008) advocate a practice-oriented approach,

termed ‘neo-realistic’,which involvesthree key managerial

practices. These include “reducing complexity by transforming

expectations”,understanding ofinterdependenciesfor better

“systemsintegration”,and,importantly,“publicarenasfor

handling theunknown amountof errors”in complex PM

settings (ibid.,p. S112,italics added).This analysis implicitly

acknowledges Hayek’s (1945) ‘specification problem’,which

here applies to complex projects thatare unable to be fully

specified in advance,by recommending organic integration

for coordinating distributed contextual knowledge.In a recent

publicationon knowledgeintegrationin a complexPM

setting,Enberg etal. (2010) also encounter Hayek's ‘specifi-

cation problem’ in terms of “unforeseeable and unimaginable

multiplying effects ofsmallchanges” (p.762).Informed by

Weick's (1995)sense-making and Polanyi’s (1967)tacitdi-

mension ofknowledge,they adopta ‘segregated team’ap-

proach to knowledge integration that relies in part on the “gut

feelings” ofseniorprojectteam members,which this paper

views as a distributed tacitdimension (Polanyi,1967,1974).

Both these empiricalpapershighlightthe need to generate

emergentknowledgein complex PM settingsthatis un-

specifiableat the outsetand theneed to coordinatethis

knowledgein a distributed approach through higher-order

principles that are self-organising (Kogut and Zander, 1992).

2.3.Complicated PM versus complex PM — planned versus

emergent

Once Hayek's (1945)‘specification problem’is acknowl-

edged in complex PM settings,it is no longertenable to

proceed under the assumption of ‘total planning’ of traditional

PM. In his classic paper on the workings of markets as complex

phenomena,Hayek (1945)highlighted a practicaldifficulty

with a centralised governance approach to knowledge.This is

because the complete data are never given “to a single m

which could work outthe implications,and can never be so

given” (ibid., p. 519), which he describes as “a problem o

utilization ofknowledge notgiven to anyone in its totality”

(ibid., p. 520). The knowledge Hayek (1945) had in mind

knowledge that was specific to the “man on the spot” (p.

which can be viewed as contextual ‘knowing’ knowledge.He

recommendedthat any solutionto this practicalproblem

needed to harnesscontextualknowledge “thatis dispersed

among many people” (ibid., p. 530).

This insight draws attention to an important difference

the terms‘complicated’and ‘complex’.An aircraftis a

complicated machine thatrelies on a large numberof servo-

mechanisms (single-loop) and crew members (double-loo

to operate the machine system within normalparameters.In

aviation history, aircraft design progressed from being a

project, when the technology was poorly understood, to b

complicated project, when detailed designs could be doc

for production assembly and, therefore, comprehensible

mind. However, like an emerging prototype that is only p

understood,a one-off complex projectmay nottransition from

complex to complicated until after it is delivered and retr

tively comprehended in its entirety (Snowden, 2002). Eve

team of planners on a complex project, if no single individ

comprehend the project interconnectivity in its entirety, t

one can preclude the possibility ofknowledge gaps between

constituentparts ofthe plan (Lenfle and Loch,2010).While

adjacent interfaces can be specified between parts of a li

like links in a chain, this approach may reduce but not eli

the potential for gaps in a complex network plan that no

individual comprehends in its entirety, e.g., PERT diagram1

Thesepotentialgapsare like untappedknowledge,or

‘unknown knowns’ (Cleden, 2009), that may exist at the

of the project or emerge over time. Using metaphors, vie

complex projectas complex problem solving (CPS)is more

like painting a landscape than the mechanicalassembly of an

elaborate jigsaw. In a jigsaw, the pieces and their connec

are known in advance but,in a landscape painting,while the

major features may be known in outline in advance,the final

connectivity has yetto emerge due to shifting light,clouds,

shadows,etc.This emphasisesthe contextualspecificity of

complex projects(Engwall,2003),which operateson the

contextualknowledge ofthe community oflearnersthatis

delivering the project by learning the project (Wenger, 20

2.4. Organisational learning under knowledge uncertainty

If complex projectsare distinguished from complicated

projects by unspecifiable pre-given knowledge thatmustbe

continuously generated overthe projectlife cycle,then,the

creation of new knowledge and its coordination become c

aspectsfor governancein complex PM. Becauseof this

incompleteness of projectplans,delivering a projectis partly

about discovering its hidden reality through “tacit forekn

1 Project Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT).

1373T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

incorporate insightsfrom research in complexity,chaos,self-

organising,and evolution with traditional PM (Cooke-Davies et

al., 2007; Geraldi et al., 2011). This emerging area in PM is termed

‘complex projectmanagement’ (Whitty and Maylor,2009).For

example,Saynisch (2010a,b) analyses complexity using the two

dimensions of ‘project complexity’ and ‘environmental complex-

ity’ and calls for a governance approach thatintegrates the two

cybernetic cyclesof traditionalPM and the managementof

complexity (evolution, self-organisation, edge of chaos). Interest-

ingly, he maintains that getting the balance right between these two

“will be the future management art” (Saynisch, 2010b, p. 8, italics

added),which suggests that,in order to dealwith situations of

project complexity, PM may have to reposition its self-image to

one of a craft with implied learning rather than an applied science

under the traditional PM paradigm with little learning anticipated

(Mintzberg, 1979, 1987).

2.2. ComplexPM as organisationalpractice— emergent

knowledge

In a paperthatrecognises the limitations ofthe planned

approachesof traditionalPM in complex projectsettings,

Berggren etal. (2008) advocate a practice-oriented approach,

termed ‘neo-realistic’,which involvesthree key managerial

practices. These include “reducing complexity by transforming

expectations”,understanding ofinterdependenciesfor better

“systemsintegration”,and,importantly,“publicarenasfor

handling theunknown amountof errors”in complex PM

settings (ibid.,p. S112,italics added).This analysis implicitly

acknowledges Hayek’s (1945) ‘specification problem’,which

here applies to complex projects thatare unable to be fully

specified in advance,by recommending organic integration

for coordinating distributed contextual knowledge.In a recent

publicationon knowledgeintegrationin a complexPM

setting,Enberg etal. (2010) also encounter Hayek's ‘specifi-

cation problem’ in terms of “unforeseeable and unimaginable

multiplying effects ofsmallchanges” (p.762).Informed by

Weick's (1995)sense-making and Polanyi’s (1967)tacitdi-

mension ofknowledge,they adopta ‘segregated team’ap-

proach to knowledge integration that relies in part on the “gut

feelings” ofseniorprojectteam members,which this paper

views as a distributed tacitdimension (Polanyi,1967,1974).

Both these empiricalpapershighlightthe need to generate

emergentknowledgein complex PM settingsthatis un-

specifiableat the outsetand theneed to coordinatethis

knowledgein a distributed approach through higher-order

principles that are self-organising (Kogut and Zander, 1992).

2.3.Complicated PM versus complex PM — planned versus

emergent

Once Hayek's (1945)‘specification problem’is acknowl-

edged in complex PM settings,it is no longertenable to

proceed under the assumption of ‘total planning’ of traditional

PM. In his classic paper on the workings of markets as complex

phenomena,Hayek (1945)highlighted a practicaldifficulty

with a centralised governance approach to knowledge.This is

because the complete data are never given “to a single m

which could work outthe implications,and can never be so

given” (ibid., p. 519), which he describes as “a problem o

utilization ofknowledge notgiven to anyone in its totality”

(ibid., p. 520). The knowledge Hayek (1945) had in mind

knowledge that was specific to the “man on the spot” (p.

which can be viewed as contextual ‘knowing’ knowledge.He

recommendedthat any solutionto this practicalproblem

needed to harnesscontextualknowledge “thatis dispersed

among many people” (ibid., p. 530).

This insight draws attention to an important difference

the terms‘complicated’and ‘complex’.An aircraftis a

complicated machine thatrelies on a large numberof servo-

mechanisms (single-loop) and crew members (double-loo

to operate the machine system within normalparameters.In

aviation history, aircraft design progressed from being a

project, when the technology was poorly understood, to b

complicated project, when detailed designs could be doc

for production assembly and, therefore, comprehensible

mind. However, like an emerging prototype that is only p

understood,a one-off complex projectmay nottransition from

complex to complicated until after it is delivered and retr

tively comprehended in its entirety (Snowden, 2002). Eve

team of planners on a complex project, if no single individ

comprehend the project interconnectivity in its entirety, t

one can preclude the possibility ofknowledge gaps between

constituentparts ofthe plan (Lenfle and Loch,2010).While

adjacent interfaces can be specified between parts of a li

like links in a chain, this approach may reduce but not eli

the potential for gaps in a complex network plan that no

individual comprehends in its entirety, e.g., PERT diagram1

Thesepotentialgapsare like untappedknowledge,or

‘unknown knowns’ (Cleden, 2009), that may exist at the

of the project or emerge over time. Using metaphors, vie

complex projectas complex problem solving (CPS)is more

like painting a landscape than the mechanicalassembly of an

elaborate jigsaw. In a jigsaw, the pieces and their connec

are known in advance but,in a landscape painting,while the

major features may be known in outline in advance,the final

connectivity has yetto emerge due to shifting light,clouds,

shadows,etc.This emphasisesthe contextualspecificity of

complex projects(Engwall,2003),which operateson the

contextualknowledge ofthe community oflearnersthatis

delivering the project by learning the project (Wenger, 20

2.4. Organisational learning under knowledge uncertainty

If complex projectsare distinguished from complicated

projects by unspecifiable pre-given knowledge thatmustbe

continuously generated overthe projectlife cycle,then,the

creation of new knowledge and its coordination become c

aspectsfor governancein complex PM. Becauseof this

incompleteness of projectplans,delivering a projectis partly

about discovering its hidden reality through “tacit forekn

1 Project Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT).

1373T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

(Polanyi,1967,p. 22),where “projectexecution is seldom a

process of implementation; rather it is a journey of knowledge

creation” that involves learning (Engwall, 2002, p. 277, italics

added).In this view, a projectis bettercharacterised as

‘becoming’than ‘being’,or better‘actor’than ‘object’,res-

pectively (Engwall,1998;Linehan and Kavanagh,2006;

Whitehead, 1985).

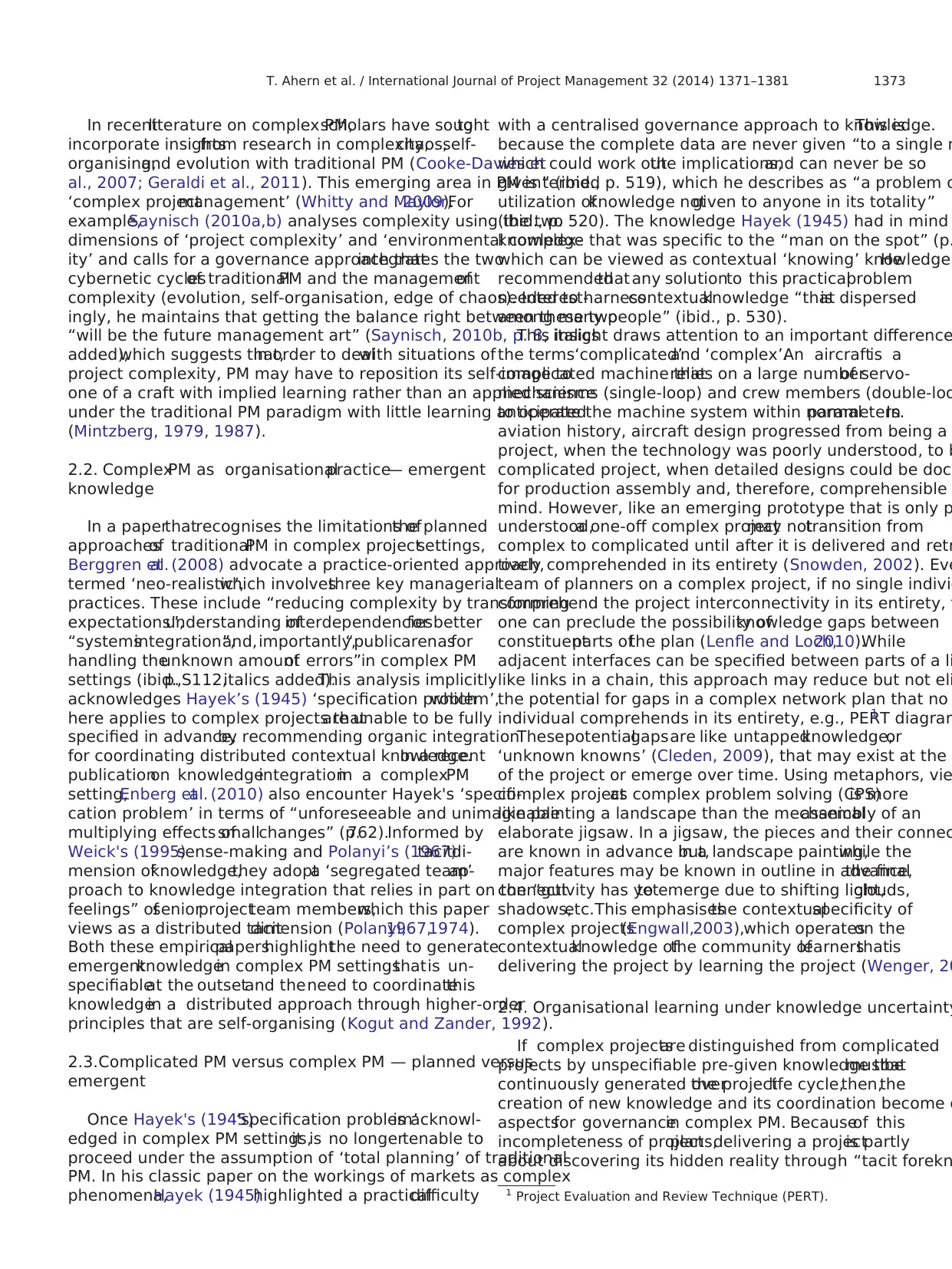

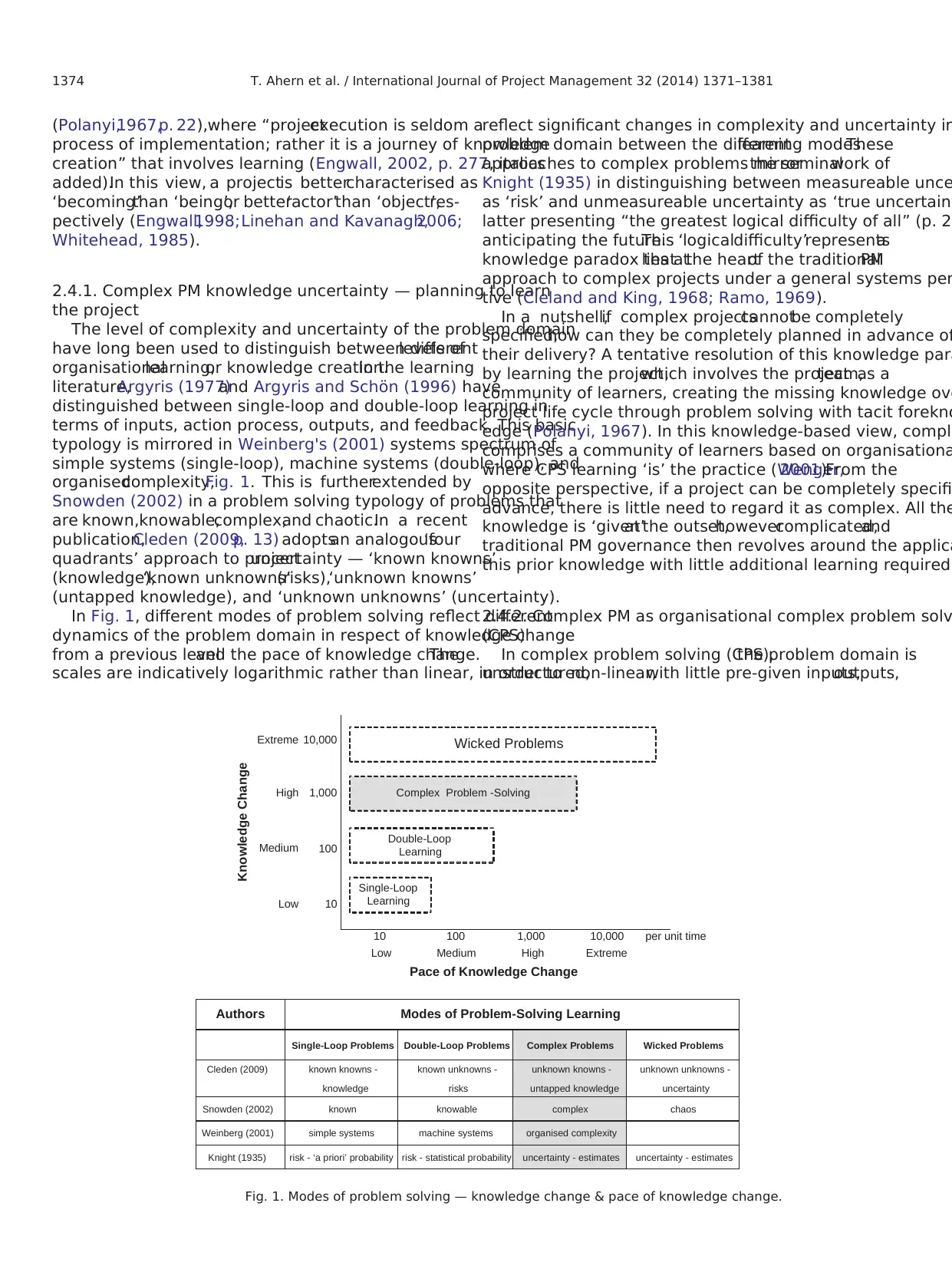

2.4.1. Complex PM knowledge uncertainty — planning to learn

the project

The level of complexity and uncertainty of the problem domain

have long been used to distinguish between differentlevels of

organisationallearning,or knowledge creation.In the learning

literature,Argyris (1977)and Argyris and Schön (1996) have

distinguished between single-loop and double-loop learning in

terms of inputs, action process, outputs, and feedback. This basic

typology is mirrored in Weinberg's (2001) systems spectrum of

simple systems (single-loop), machine systems (double-loop), and

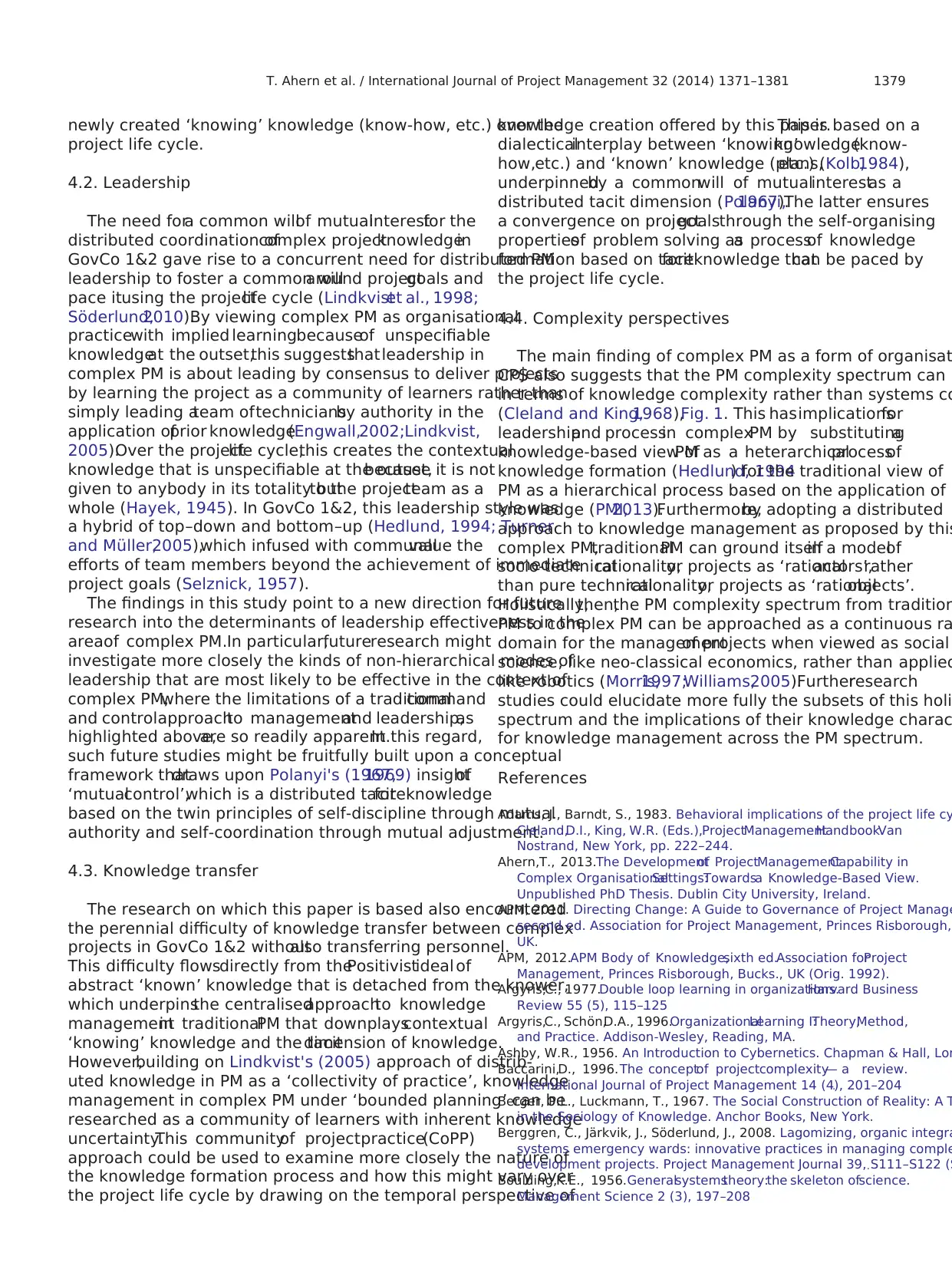

organisedcomplexity,Fig. 1. This is furtherextended by

Snowden (2002) in a problem solving typology of problems that

are known,knowable,complex,and chaotic.In a recent

publication,Cleden (2009,p. 13) adoptsan analogous‘four

quadrants’ approach to projectuncertainty — ‘known knowns’

(knowledge),‘known unknowns’(risks),‘unknown knowns’

(untapped knowledge), and ‘unknown unknowns’ (uncertainty).

In Fig. 1, different modes of problem solving reflect different

dynamics of the problem domain in respect of knowledge change

from a previous leveland the pace of knowledge change.The

scales are indicatively logarithmic rather than linear, in order to

reflect significant changes in complexity and uncertainty in

problem domain between the differentlearning modes.These

approaches to complex problems mirrorthe seminalwork of

Knight (1935) in distinguishing between measureable unce

as ‘risk’ and unmeasureable uncertainty as ‘true uncertain

latter presenting “the greatest logical difficulty of all” (p. 2

anticipating the future.This ‘logicaldifficulty’representsa

knowledge paradox thatlies atthe heartof the traditionalPM

approach to complex projects under a general systems per

tive (Cleland and King, 1968; Ramo, 1969).

In a nutshell,if complex projectscannotbe completely

specified,how can they be completely planned in advance of

their delivery? A tentative resolution of this knowledge para

by learning the project,which involves the projectteam,as a

community of learners, creating the missing knowledge ove

project life cycle through problem solving with tacit forekno

edge (Polanyi, 1967). In this knowledge-based view, comple

comprises a community of learners based on organisationa

where CPS learning ‘is’ the practice (Wenger,2001).From the

opposite perspective, if a project can be completely specifi

advance, there is little need to regard it as complex. All the

knowledge is ‘given’at the outset,howevercomplicated,and

traditional PM governance then revolves around the applica

this prior knowledge with little additional learning required.

2.4.2. Complex PM as organisational complex problem solv

(CPS)

In complex problem solving (CPS),the problem domain is

unstructured,non-linear,with little pre-given inputs,outputs,

Extreme 10,000

High 1,000

Medium 100

Low 10

10 100 1,000 10,000 per unit time

Low Medium High Extreme

Pace of Knowledge Change

Knowledge Change

Single-Loop

Learning

Double-Loop

Learning

Complex Problem -Solving

Wicked Problems

Authors

Single-Loop Problems Double-Loop Problems Complex Problems Wicked Problems

Cleden (2009) known knowns - known unknowns - unknown knowns - unknown unknowns -

knowledge risks untapped knowledge uncertainty

Snowden (2002) known knowable complex chaos

Weinberg (2001) simple systems machine systems organised complexity

Knight (1935) risk - ‘a priori’ probability risk - statistical probability uncertainty - estimates uncertainty - estimates

Modes of Problem-Solving Learning

Fig. 1. Modes of problem solving — knowledge change & pace of knowledge change.

1374 T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

process of implementation; rather it is a journey of knowledge

creation” that involves learning (Engwall, 2002, p. 277, italics

added).In this view, a projectis bettercharacterised as

‘becoming’than ‘being’,or better‘actor’than ‘object’,res-

pectively (Engwall,1998;Linehan and Kavanagh,2006;

Whitehead, 1985).

2.4.1. Complex PM knowledge uncertainty — planning to learn

the project

The level of complexity and uncertainty of the problem domain

have long been used to distinguish between differentlevels of

organisationallearning,or knowledge creation.In the learning

literature,Argyris (1977)and Argyris and Schön (1996) have

distinguished between single-loop and double-loop learning in

terms of inputs, action process, outputs, and feedback. This basic

typology is mirrored in Weinberg's (2001) systems spectrum of

simple systems (single-loop), machine systems (double-loop), and

organisedcomplexity,Fig. 1. This is furtherextended by

Snowden (2002) in a problem solving typology of problems that

are known,knowable,complex,and chaotic.In a recent

publication,Cleden (2009,p. 13) adoptsan analogous‘four

quadrants’ approach to projectuncertainty — ‘known knowns’

(knowledge),‘known unknowns’(risks),‘unknown knowns’

(untapped knowledge), and ‘unknown unknowns’ (uncertainty).

In Fig. 1, different modes of problem solving reflect different

dynamics of the problem domain in respect of knowledge change

from a previous leveland the pace of knowledge change.The

scales are indicatively logarithmic rather than linear, in order to

reflect significant changes in complexity and uncertainty in

problem domain between the differentlearning modes.These

approaches to complex problems mirrorthe seminalwork of

Knight (1935) in distinguishing between measureable unce

as ‘risk’ and unmeasureable uncertainty as ‘true uncertain

latter presenting “the greatest logical difficulty of all” (p. 2

anticipating the future.This ‘logicaldifficulty’representsa

knowledge paradox thatlies atthe heartof the traditionalPM

approach to complex projects under a general systems per

tive (Cleland and King, 1968; Ramo, 1969).

In a nutshell,if complex projectscannotbe completely

specified,how can they be completely planned in advance of

their delivery? A tentative resolution of this knowledge para

by learning the project,which involves the projectteam,as a

community of learners, creating the missing knowledge ove

project life cycle through problem solving with tacit forekno

edge (Polanyi, 1967). In this knowledge-based view, comple

comprises a community of learners based on organisationa

where CPS learning ‘is’ the practice (Wenger,2001).From the

opposite perspective, if a project can be completely specifi

advance, there is little need to regard it as complex. All the

knowledge is ‘given’at the outset,howevercomplicated,and

traditional PM governance then revolves around the applica

this prior knowledge with little additional learning required.

2.4.2. Complex PM as organisational complex problem solv

(CPS)

In complex problem solving (CPS),the problem domain is

unstructured,non-linear,with little pre-given inputs,outputs,

Extreme 10,000

High 1,000

Medium 100

Low 10

10 100 1,000 10,000 per unit time

Low Medium High Extreme

Pace of Knowledge Change

Knowledge Change

Single-Loop

Learning

Double-Loop

Learning

Complex Problem -Solving

Wicked Problems

Authors

Single-Loop Problems Double-Loop Problems Complex Problems Wicked Problems

Cleden (2009) known knowns - known unknowns - unknown knowns - unknown unknowns -

knowledge risks untapped knowledge uncertainty

Snowden (2002) known knowable complex chaos

Weinberg (2001) simple systems machine systems organised complexity

Knight (1935) risk - ‘a priori’ probability risk - statistical probability uncertainty - estimates uncertainty - estimates

Modes of Problem-Solving Learning

Fig. 1. Modes of problem solving — knowledge change & pace of knowledge change.

1374 T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

action process,or feedback (Argyris and Schön,1996;Newell

and Simon, 1972).As a key driver of change in organisational

knowledge, a volatile external environment can be viewed as a

stimulus with a high levelof knowledge change and pace of

knowledge change. Moreover, the volatility of the environment is

largely unknowable ex ante as a dynamic phenomenon, except in

outline or in part,even though itcan be known ex postas a

sequence of static phenomena or comparative statics (Boulding,

1956;March, 1994).The characteristicsof organisational

complex problems in Weinberg (2001),Snowden (2002),and

Cleden (2009) resonate with an earlier contribution by Swinth

(1971, pp. B68-9, italics added) as follows:

(1) Usually the solution must serve a variety of organizational

objectives.

(2) Thereis typically ahigh degreeof interdependence

between parts.

(3) Such tasks are too complex to be readily understood and

solved by one person or group.

(4) The cause of the novelty is typically a changing world …

[or] the unknowns at the frontier of knowledge or at the

interfacearising from combining existingideasand

techniques in a new way.

With complex problem solving (CPS),a key role of senior

managementis framing the problem to be resolved (Daftand

Weick, 1984; Teece et al., 1997). As Morris (1997) points out,

this is the difference between ‘projectmanagement’and the

‘managementof projects’,the latterbeing a more strategic

approach that encompasses the economic life cycle, rather than

just the project life cycle (Jugdev and Müller, 2005; Munns and

Bjeirmi, 1996). Beyond complex problems are so-called ‘wicked

problems’, Fig. 1, which are chaotic and intractable problems that

usually require crisis project management and are not considered

relevantfor complex PM in thispaper(Churchman,1967;

Mumford, 1998; Snowden, 2002).

2.4.3.ComplexPM knowledgemanagementas distributed

knowledge organising

As a way of dealing with complex problems, Swinth (1971)

proposes ‘organizationaljointproblem-solving’,based on the

‘organic’approachof Burns and Stalker(1961).In the

innovation literature,the same approach isused by Brown

and Eisenhardt (1997) for “high-velocity” (p.1) environments

of radicaland rapid change,which isanalogousto a CPS

environment with a high level of knowledge change and pace

of change,Fig. 1. This ‘organic’ approach is viewed by this

paper as one based on a common willof mutualinterestas a

distributed tacitdimension (Polanyi,1967),where the actor

participates in the overall goals to be achieved. This is akin to

Adam Smith's (1981)‘invisible hand’ of self-interestin The

Wealth ofNations,where the actoris focused on personal

economic goals rather than mutual goals.

However, in order to achieve the centralised coordination of

abstract ‘known’ knowledge (designs, plans, etc.), it needs to be

facilitatedby the distributedcoordinationof contextual

‘knowing’ knowledge (know-how,etc.) under a common will

of mutual interest. This is based on tacit pre-suppositions

following the rules of a practice (Wittgenstein, 1988). It is

self-organisingpropertyof problem solvingthroughtacit

foreknowledge,which is beyond centralised planning contro

(Kolb,1984; Orlikowski,2006; Tsoukas,1996),that provides

the requisite order for dealing with complex problems tha

“too complex to be readily understood and solved by one

personor group”(Swinth,1971,p. B69). In this way,

contextualdynamicknowledge(know-how,etc.)coalesces

any gaps in pre-given static knowledge (plans, etc.) that

overtime as ‘unknown knowns’,which are unknowable in

advanceundertraditionalPM becauseof the contextual

specificity of‘knowing’knowledge (Dewey,1966;Dewey

and Bentley, 1949; Hayek, 1945).

Temporary organisationaldynamics thatinvolve distributed

learning and organising have been investigated in compl

projectsettingsthat resonatewith the characteristicsof

organisationalCPS. This previous research revolves around a

largely unspecifiable problem situation ex ante and subse

problem solving with distributed knowledge organising us

common will of mutual interest as a distributed tacit dime

(Polanyi,1967).Thus,Meyerson etal. (1996)identify ‘swift

trust’ as a self-organising coordinating mechanism in tem

conference groups, Weick and Roberts (1993) identify ‘he

interrelating’ for coordinating on flight decks, and Weick

investigates the breakdown ofa common understanding in a

situation of novel high-level complexity. In the strategy li

Eisenhardt (1999) identifies ‘collective intuition’ as an ing

for successful strategy building and, in the PM literature,

(1996)indentifies‘team mind’in relation to localdecision-

making among projectteam membersbased on “taken-for-

granted protocols” (p. 261) that is often the result of goo

leadership.

3. Managing distributed knowledge under uncertainty —

fostering and pacing a common will of mutual interest

The empiricalfinding thatcomplex PM is a form of

organisationalCPS with knowledge uncertainty as a defining

characteristicmeansthatknowledgegovernanceis a key

challenge for the emerging research in complex PM gove

(Pemseland Müller, 2012) and this includesmanaging

incomplete pre-given knowledge under a ‘bounded plann

approach.This involves continuously creating the contextu

knowledgethat is un-specifiableat the outsetover the

remaining projectlife cycle and coordinating thisemergent

knowledge through the agency ofa common willof mutual

interest, as proposed here, or through other means.

Using a distributed organising perspective,these related

findings are now examined in the following sections as as

of learning and organising in a distributed approach to co

PM knowledge management in GovCo 1&2. In this distrib

perspective, the tools and techniques of traditional PM ar

used buttheirrole is reinterpreted in a learning approach to

complex PM as organisational CPS.For example,planning is

seen to includeplans to learn the project,documented

procedures are viewed as ‘scaffolding’ for creating emerg

1375T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

and Simon, 1972).As a key driver of change in organisational

knowledge, a volatile external environment can be viewed as a

stimulus with a high levelof knowledge change and pace of

knowledge change. Moreover, the volatility of the environment is

largely unknowable ex ante as a dynamic phenomenon, except in

outline or in part,even though itcan be known ex postas a

sequence of static phenomena or comparative statics (Boulding,

1956;March, 1994).The characteristicsof organisational

complex problems in Weinberg (2001),Snowden (2002),and

Cleden (2009) resonate with an earlier contribution by Swinth

(1971, pp. B68-9, italics added) as follows:

(1) Usually the solution must serve a variety of organizational

objectives.

(2) Thereis typically ahigh degreeof interdependence

between parts.

(3) Such tasks are too complex to be readily understood and

solved by one person or group.

(4) The cause of the novelty is typically a changing world …

[or] the unknowns at the frontier of knowledge or at the

interfacearising from combining existingideasand

techniques in a new way.

With complex problem solving (CPS),a key role of senior

managementis framing the problem to be resolved (Daftand

Weick, 1984; Teece et al., 1997). As Morris (1997) points out,

this is the difference between ‘projectmanagement’and the

‘managementof projects’,the latterbeing a more strategic

approach that encompasses the economic life cycle, rather than

just the project life cycle (Jugdev and Müller, 2005; Munns and

Bjeirmi, 1996). Beyond complex problems are so-called ‘wicked

problems’, Fig. 1, which are chaotic and intractable problems that

usually require crisis project management and are not considered

relevantfor complex PM in thispaper(Churchman,1967;

Mumford, 1998; Snowden, 2002).

2.4.3.ComplexPM knowledgemanagementas distributed

knowledge organising

As a way of dealing with complex problems, Swinth (1971)

proposes ‘organizationaljointproblem-solving’,based on the

‘organic’approachof Burns and Stalker(1961).In the

innovation literature,the same approach isused by Brown

and Eisenhardt (1997) for “high-velocity” (p.1) environments

of radicaland rapid change,which isanalogousto a CPS

environment with a high level of knowledge change and pace

of change,Fig. 1. This ‘organic’ approach is viewed by this

paper as one based on a common willof mutualinterestas a

distributed tacitdimension (Polanyi,1967),where the actor

participates in the overall goals to be achieved. This is akin to

Adam Smith's (1981)‘invisible hand’ of self-interestin The

Wealth ofNations,where the actoris focused on personal

economic goals rather than mutual goals.

However, in order to achieve the centralised coordination of

abstract ‘known’ knowledge (designs, plans, etc.), it needs to be

facilitatedby the distributedcoordinationof contextual

‘knowing’ knowledge (know-how,etc.) under a common will

of mutual interest. This is based on tacit pre-suppositions

following the rules of a practice (Wittgenstein, 1988). It is

self-organisingpropertyof problem solvingthroughtacit

foreknowledge,which is beyond centralised planning contro

(Kolb,1984; Orlikowski,2006; Tsoukas,1996),that provides

the requisite order for dealing with complex problems tha

“too complex to be readily understood and solved by one

personor group”(Swinth,1971,p. B69). In this way,

contextualdynamicknowledge(know-how,etc.)coalesces

any gaps in pre-given static knowledge (plans, etc.) that

overtime as ‘unknown knowns’,which are unknowable in

advanceundertraditionalPM becauseof the contextual

specificity of‘knowing’knowledge (Dewey,1966;Dewey

and Bentley, 1949; Hayek, 1945).

Temporary organisationaldynamics thatinvolve distributed

learning and organising have been investigated in compl

projectsettingsthat resonatewith the characteristicsof

organisationalCPS. This previous research revolves around a

largely unspecifiable problem situation ex ante and subse

problem solving with distributed knowledge organising us

common will of mutual interest as a distributed tacit dime

(Polanyi,1967).Thus,Meyerson etal. (1996)identify ‘swift

trust’ as a self-organising coordinating mechanism in tem

conference groups, Weick and Roberts (1993) identify ‘he

interrelating’ for coordinating on flight decks, and Weick

investigates the breakdown ofa common understanding in a

situation of novel high-level complexity. In the strategy li

Eisenhardt (1999) identifies ‘collective intuition’ as an ing

for successful strategy building and, in the PM literature,

(1996)indentifies‘team mind’in relation to localdecision-

making among projectteam membersbased on “taken-for-

granted protocols” (p. 261) that is often the result of goo

leadership.

3. Managing distributed knowledge under uncertainty —

fostering and pacing a common will of mutual interest

The empiricalfinding thatcomplex PM is a form of

organisationalCPS with knowledge uncertainty as a defining

characteristicmeansthatknowledgegovernanceis a key

challenge for the emerging research in complex PM gove

(Pemseland Müller, 2012) and this includesmanaging

incomplete pre-given knowledge under a ‘bounded plann

approach.This involves continuously creating the contextu

knowledgethat is un-specifiableat the outsetover the

remaining projectlife cycle and coordinating thisemergent

knowledge through the agency ofa common willof mutual

interest, as proposed here, or through other means.

Using a distributed organising perspective,these related

findings are now examined in the following sections as as

of learning and organising in a distributed approach to co

PM knowledge management in GovCo 1&2. In this distrib

perspective, the tools and techniques of traditional PM ar

used buttheirrole is reinterpreted in a learning approach to

complex PM as organisational CPS.For example,planning is

seen to includeplans to learn the project,documented

procedures are viewed as ‘scaffolding’ for creating emerg

1375T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

knowledge,and projectgoals are used to fosterand pace a

common will of mutual interest.

3.1. ComplexPM knowledgemanagementas distributed

learning and organising

In descriptive terms, the need for a common will of mutual

interest to coordinate knowledge in complex PM as a form of

organisationalCPS does not meanthatcomplexprojects

cannot,or should not,be planned butthatcomplex projects

cannotbe completely planned in advance oftheirdelivery

(Geraldi et al., 2011; Nightingale and Brady, 2011). Borrowing

from Simon (1997),this paper suggests that complex projects

may only be ‘boundedly’ planned as emergent prototypes with

incomplete knowledge. For example, not every element of the

space mission to the Moon, or the voyage of Columbus to the

New World,was planned in advance nor could it be,because

the totalcomplexity could notbe completelyspecified or

comprehended in advance by a single individual,exceptin

outline or in part (Hayek, 1945; Smith, 1981). However, in both

cases,when the abstract but static ‘known’ knowledge (plans,

etc.) of the preparatory planning was coupled with the common

will of mutualinterestof the projectteam as a mechanism of

mutual control, this ensured a convergence on the mission goals

at all times.In turn, this facilitated thegeneration,when

required,of the dynamic but contextual ‘knowing’ knowledge

(know-how,etc.)thatwas unspecifiable atthe outset,which

completed the knowledge setfor projectdelivery of ‘known’

knowledge,‘knowing’knowledge,and theircommon tacit

dimension.

Nevertheless,as with the developmentof the US Polaris

submarine projectin the 1950s,the sensibilities ofWestern

attitudes to knowledge based on technical rationality require an

emphasis on abstract‘known’knowledge atthe outsetof a

projectthatis detached from the knowing subject(Sapolsky,

1972;Spinardi,1994).This is to the detrimentof a more

realisticsocio-technicalperspectivebasedon higher-order

principlesfor organising knowledge thatare irreducible to

individuals (Kogutand Zander,1992),which is empirically

supported by this paper.It is not a choice between objectivity

based on abstract‘known’ knowledge and subjectivity based

on ‘knowing’knowledge but,rather,a necessary synthesis

of both overthe projectlife cycle,which is largely absent

from the business and PM literatures (Cook and Brown, 1999).

The bounded planning ofcomplex projectswas implicitly

recognisedin GovCo-1,by acknowledgingthe needfor

exploratory projectsto createintermediateknowledgethat

reduced overall knowledge uncertainty before undertaking major

projects (Lenfle and Loch, 2010), as observed by a Programme

Manager in GovCo-1:

[In ProjectX], if the company had undertaken pre-tender

shutdowns for a month to completely flesh-out the design …

it would have been better for the project. In [Project Y], they

did better pre-tender site investigations … so that, when the

contractorhit the site,therewereless surprises,delay,

disruption, and cost.

In normativeterms,if complex projectsare limited to

bounded planning,this recallsEisenhower'saphorism that

“plansare worthless,but planning iseverything”,2 which

suggests that Eisenhower felt that abstract ‘known’ knowle

in plansmay notbe capable ofmapping complex military

environmentsor adequate forcoordinating a response to a

changing complex environment. This might be better achie

throughthe ‘knowing’knowledgeof the lived planning

process,which impliesthatknowledgeability isdifficultto

separate from knowing subjects.Borrowing from Eisenhower

for organisations,this papersuggests that‘organisations are

nothing butorganising is everything’.And because organisa-

tions are aboutorganising and sense-making (Weick,1979,

1995),this papersupportsthe view thatsense-making in

projectsas temporary organisationsoccurslargely through

learning based on problem solving (Lundin and Söderholm,

1995;Packendorff,1995).As a manifestation ofdistributed

organising and learning from the data, the project manage

office arrangementsin GovCo-1 often changed during the

2000s,becausedelivering complex projectsleading to the

developmentof new PM expertise was more emergentthan

deliberate,althoughit was plannedon its own terms

(Mintzberg,1990;Okhuysen and Eisenhardt,2002).In this

community oflearners approach to learning and organising

based on organisationalCPS, complex PM is “as much about

doing in order to think as thinking in order to do” (Mintzber

2004, p. 10).

3.2. The scaffolding of distributed learning and organising

In GovCo 1&2, documented procedures for complex PM d

notexistto the same extentbefore the developmentof their

respective complex PM expertise. Using the lens of structur

agency (Giddens,2007),the value ofthe new documented

procedureswas their structuralrole as ‘scaffolding’for

establishing a consensus for delivering complex projects am

project team members as actors (Bruner, 1986). Over time

facilitated the developmentof PM expertise by coordinating

the behaviourof projectteam membersas a distributed or-

ganisationalpractice (Nightingale and Brady,2011).This was

underpinned by thecreation ofemergentknowledgeby a

dialectical interplay of abstract ‘known’ knowledge (proced

etc.)with contextual‘knowing’knowledge (know-how,etc.)

(Kolb, 1984; Orlikowski, 2002, 2006; Tsoukas, 1996) throug

common will of mutual interest as a distributed tacit dimen

(Polanyi, 1967). As observed by a Project Manager in GovCo

Prior to that[Procedures],if you spoke to any of our staff

about scope, or bills of quantities, or schedules of rates,

were an alien language./…/Afterthis was rolled out[Pro-

cedures] … it became the common language and it supp

the interchange of information.

Nevertheless, experienced project managers in GovCo 1&

appreciatethe limitationsof documentedproceduresand

2 Speech delivered to the NationalDefense Executive Reserve Conference,

Washington, D.C., on 14 November 1957.

1376 T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

common will of mutual interest.

3.1. ComplexPM knowledgemanagementas distributed

learning and organising

In descriptive terms, the need for a common will of mutual

interest to coordinate knowledge in complex PM as a form of

organisationalCPS does not meanthatcomplexprojects

cannot,or should not,be planned butthatcomplex projects

cannotbe completely planned in advance oftheirdelivery

(Geraldi et al., 2011; Nightingale and Brady, 2011). Borrowing

from Simon (1997),this paper suggests that complex projects

may only be ‘boundedly’ planned as emergent prototypes with

incomplete knowledge. For example, not every element of the

space mission to the Moon, or the voyage of Columbus to the

New World,was planned in advance nor could it be,because

the totalcomplexity could notbe completelyspecified or

comprehended in advance by a single individual,exceptin

outline or in part (Hayek, 1945; Smith, 1981). However, in both

cases,when the abstract but static ‘known’ knowledge (plans,

etc.) of the preparatory planning was coupled with the common

will of mutualinterestof the projectteam as a mechanism of

mutual control, this ensured a convergence on the mission goals

at all times.In turn, this facilitated thegeneration,when

required,of the dynamic but contextual ‘knowing’ knowledge

(know-how,etc.)thatwas unspecifiable atthe outset,which

completed the knowledge setfor projectdelivery of ‘known’

knowledge,‘knowing’knowledge,and theircommon tacit

dimension.

Nevertheless,as with the developmentof the US Polaris

submarine projectin the 1950s,the sensibilities ofWestern

attitudes to knowledge based on technical rationality require an

emphasis on abstract‘known’knowledge atthe outsetof a

projectthatis detached from the knowing subject(Sapolsky,

1972;Spinardi,1994).This is to the detrimentof a more

realisticsocio-technicalperspectivebasedon higher-order

principlesfor organising knowledge thatare irreducible to

individuals (Kogutand Zander,1992),which is empirically

supported by this paper.It is not a choice between objectivity

based on abstract‘known’ knowledge and subjectivity based

on ‘knowing’knowledge but,rather,a necessary synthesis

of both overthe projectlife cycle,which is largely absent

from the business and PM literatures (Cook and Brown, 1999).

The bounded planning ofcomplex projectswas implicitly

recognisedin GovCo-1,by acknowledgingthe needfor

exploratory projectsto createintermediateknowledgethat

reduced overall knowledge uncertainty before undertaking major

projects (Lenfle and Loch, 2010), as observed by a Programme

Manager in GovCo-1:

[In ProjectX], if the company had undertaken pre-tender

shutdowns for a month to completely flesh-out the design …

it would have been better for the project. In [Project Y], they

did better pre-tender site investigations … so that, when the

contractorhit the site,therewereless surprises,delay,

disruption, and cost.

In normativeterms,if complex projectsare limited to

bounded planning,this recallsEisenhower'saphorism that

“plansare worthless,but planning iseverything”,2 which

suggests that Eisenhower felt that abstract ‘known’ knowle

in plansmay notbe capable ofmapping complex military

environmentsor adequate forcoordinating a response to a

changing complex environment. This might be better achie

throughthe ‘knowing’knowledgeof the lived planning

process,which impliesthatknowledgeability isdifficultto

separate from knowing subjects.Borrowing from Eisenhower

for organisations,this papersuggests that‘organisations are

nothing butorganising is everything’.And because organisa-

tions are aboutorganising and sense-making (Weick,1979,

1995),this papersupportsthe view thatsense-making in

projectsas temporary organisationsoccurslargely through

learning based on problem solving (Lundin and Söderholm,

1995;Packendorff,1995).As a manifestation ofdistributed

organising and learning from the data, the project manage

office arrangementsin GovCo-1 often changed during the

2000s,becausedelivering complex projectsleading to the

developmentof new PM expertise was more emergentthan

deliberate,althoughit was plannedon its own terms

(Mintzberg,1990;Okhuysen and Eisenhardt,2002).In this

community oflearners approach to learning and organising

based on organisationalCPS, complex PM is “as much about

doing in order to think as thinking in order to do” (Mintzber

2004, p. 10).

3.2. The scaffolding of distributed learning and organising

In GovCo 1&2, documented procedures for complex PM d

notexistto the same extentbefore the developmentof their

respective complex PM expertise. Using the lens of structur

agency (Giddens,2007),the value ofthe new documented

procedureswas their structuralrole as ‘scaffolding’for

establishing a consensus for delivering complex projects am

project team members as actors (Bruner, 1986). Over time

facilitated the developmentof PM expertise by coordinating

the behaviourof projectteam membersas a distributed or-

ganisationalpractice (Nightingale and Brady,2011).This was

underpinned by thecreation ofemergentknowledgeby a

dialectical interplay of abstract ‘known’ knowledge (proced

etc.)with contextual‘knowing’knowledge (know-how,etc.)

(Kolb, 1984; Orlikowski, 2002, 2006; Tsoukas, 1996) throug

common will of mutual interest as a distributed tacit dimen

(Polanyi, 1967). As observed by a Project Manager in GovCo

Prior to that[Procedures],if you spoke to any of our staff

about scope, or bills of quantities, or schedules of rates,

were an alien language./…/Afterthis was rolled out[Pro-

cedures] … it became the common language and it supp

the interchange of information.

Nevertheless, experienced project managers in GovCo 1&

appreciatethe limitationsof documentedproceduresand

2 Speech delivered to the NationalDefense Executive Reserve Conference,

Washington, D.C., on 14 November 1957.

1376 T. Ahern et al. / International Journal of Project Management 32 (2014) 1371–1381

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

understandthat expertknowledgeis embodiedin expert

practitionerswhose expertiseis on display but largely

undocumented (Wittgenstein,1988).In both GovCo 1&2,the

relative ineffability of ‘knowing’ knowledge (know-how,etc.)

compared to ‘known’ knowledge (plans,etc.) often proved to

be an impedimentto the transferof PM expertise without

transferring personnel(Szulanski,1996;von Hippel,1994).

Such individualsfill the missing gapsin documented pro-

cedures for new practitioners, “because they had the reasoning

and thought process of why things were done” in certain ways

in the procedures(ProgrammeManager,GovCo-1).What

remains invisible to the naked eye is the communication of the

tacitdimension of expertknowledge between practitioners at

different levels of expertise, which is driven by a common will

to commune their experiences as a shared identity (Czarniawska-

Joerges, 1989, 1992; Polanyi, 1969).

3.3. Pacing logic for distributed learning and organising

In a practice-oriented approach, delivering complex projects

in GovCo 1&2 that develops PM expertise can be understood

as problem solving cyclesof goals,practice,and learning,

which togetherpromote development(Brown and Duguid,

1991). The project life cycle (PLC) is a defining characteristic

that demarcatesprojectmanagementfrom otherareasof

management(Morris,2002).In this,projectgoal-setting is an

important driver of the means–end process of problem solving

that underpinsthe deliveryof complexprojectsand the

development of PM expertise throughout the project life cycle

(Van de Ven,1992).Accordingly,it is usefulto think of the

PLC as a phased meta-level goal, or metronome, or entrainment

device, which sets the pace for the goal-driven problem solving

and learning thatunderpins the developmentof PM expertise

throughout the project life cycle (Lindkvist et al., 1998; Sayles

and Chandler,1971; Söderlund,2010).This PLC pace-setting

is termed ‘PLC-entrainment’ and is manifest in the tacit pulse

of the traditionalPM process group of goal-setting,planning,

executing,and closure (APM,2012;PMI, 2013),which this

paper reinterprets from the case study data as a learning process

group, basedon problem solving,of goals, formation,

integration, and normalisation (Popper, 1979). When combined

with pace-setting,it appears thatgoals have a Doppler effect

thatfocuses problem solving learning,because approaching

goals have a higher stimulus pitch than the same goals that are

moving away towards completion.

In GovCo 1&2, the latterprocessgroup underpinsthe

development of PM expertise through cycles of goals, practice,

and learning (Enberg et al., 2006; Kreiner, 2002), where PM is

now viewed as an organisationalpractice based on learning

(Wenger, 2001) rather than an applied science (PMI, 2013). If the

projectlife cycle is divided into differentphases (Adams and

Barndt,1983;King and Cleland,1983;PMI, 2013),the

PLC-entrainment triggers in each phase a learning mini-cycle of

goals, formation, integration, and normalisation. This underpins

interactive cycles of PM developmentthrough goals,practice,

learning, and development as an organisational practice in each

phase of the project life cycle. The achievement of this collective

action asa shared commitmentreliesmore on sharing the

experience of collective action than having a shared colle

meaning in itself(Czarniawska-Joerges,1992,p. 33). For

example,people of a similar culture can share the commun

experience of its enactment but can have different interp

of its meaning, resulting in either a broad or narrow chur

GovCo 1&2,the developmentof a common willof mutual

interestas a distributed tacitdimension (Polanyi,1967)was

fostered around projectgoals thatwere challenging forboth

organisations.This enabled the convergence of multiple mea

ings,or “subuniversesof meaning” (Bergerand Luckmann,

1967,p. 86),to a narrow distribution around agreed projec

targets,which was paced by the PLC-entrainmentof ongoing

project delivery.

3.4. Fostering a common will of mutual interest

Using the lens of tacit foreknowledge, a complex probl

one that is unspecifiable, except in outline or in part, whi

be held in common by a group of people. Its detailed solu

generally notknown in advancebut, rather,relieson an

emergentdistributed foreknowledge thatis marshalled by a

commonwill of mutualinterestthatis not reducibleto

individuals(Kogutand Zander,1992).A key aspectof a