Self-Concept & Gender: Impact on IQ Estimation - A University Study

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/12

|14

|3141

|76

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the influence of self-concept and gender stereotyping on self-estimated intelligence scores. Forty university students participated in the study, estimating their own IQ scores as well as those of their mothers and fathers. The results indicated a persistent societal bias favoring masculinity, with fathers generally estimated to have higher IQs than mothers. Independent t-tests revealed a significant difference between participants' self-estimated IQs and their estimations of their mothers' IQs, but no significant difference between their self-estimations and their fathers' IQs. While no significant gender-based differences were observed among the participants' self-estimations, the study highlights the continued impact of gender stereotypes on perceived intelligence. The report also acknowledges limitations, such as the lack of consideration for cultural background and childhood experiences, suggesting avenues for future research. Desklib provides access to this report and many other solved assignments to aid students in their studies.

1

A comparison of self-estimated IQ scores

Student Name: Student ID:

Unit Name: Unit ID:

Date Due: Professor Name:

A comparison of self-estimated IQ scores

Student Name: Student ID:

Unit Name: Unit ID:

Date Due: Professor Name:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Abstract

The spatial capability of human being indicates its intelligence level. The self-concept, gender

stereotype society assesses itself based on self-determined parameters. The purpose of the study

was to scrutinize the effect of self-concept and gender stereotyping in estimating intelligence

scores of the participants. Forty participants were chosen from the university campus for the

purpose of the study (Marcia, 2017). Estimated IQ scores of self along with that of their fathers

and mothers revealed that human society is still in favor of masculinity rather than femininity.

Independent t-tests found a significant difference in estimated IQ scores between participants and

their mothers. Fathers were estimated to be more intelligent than mothers, but no significant

difference in estimated IQ scores was observed between the participants and their fathers.

Gender wise comparison did not yield any significant result.

Keywords: Intelligence, gender, Self-estimated IQ, Gender stereotype, Self-concept

Abstract

The spatial capability of human being indicates its intelligence level. The self-concept, gender

stereotype society assesses itself based on self-determined parameters. The purpose of the study

was to scrutinize the effect of self-concept and gender stereotyping in estimating intelligence

scores of the participants. Forty participants were chosen from the university campus for the

purpose of the study (Marcia, 2017). Estimated IQ scores of self along with that of their fathers

and mothers revealed that human society is still in favor of masculinity rather than femininity.

Independent t-tests found a significant difference in estimated IQ scores between participants and

their mothers. Fathers were estimated to be more intelligent than mothers, but no significant

difference in estimated IQ scores was observed between the participants and their fathers.

Gender wise comparison did not yield any significant result.

Keywords: Intelligence, gender, Self-estimated IQ, Gender stereotype, Self-concept

3

Introduction:

Intelligence and cognitive skills are interrelated characteristics of the human brain. Qualitative

and quantitative powers of analysis are the two abilities by which information gets channelized

and categorized in the brain. The arithmetic logical part of the brain analyses the numerical sets

of information whereas the emotional processor recognizes the social behavioral activities,

intelligence is an accumulation of all these activities. From the very beginning of civilization,

self-concept has been a spiritual yet behavioral viewpoint. The power of cognitive skills or

influence of intelligence has relentlessly struggled to assert the idea of the self-concept from the

very beginning of social structuring. The logical part of the brain has religiously failed to arrest

the elusive perception of self-concept in humans. Another fallacy of human social system is

gender stereotyping; this infectious characteristic has imparted some preset responsibility for

both the genders due to which personal attributes of men have injected some norms and

profoundly ingrained attitudes towards the opposite sex. The sensitiveness of gender stereotyping

has enhanced the attributes of self-concept in men compared to women. In an earlier study by

Torrance in 1963 the effect of gender stereotyping was observed. In The self-concept of

supremacy in numerical and logical ability by men was clearly identified in his experiment. In

the year 2002, Thomas H. Rammsayer re-established self-estimates of exceptional aspects of

intelligence in men which was mainly due to gender-role orientation. Roland Neumann (2015) in

his research work on gender role orientation reassessed the difference in masculinity and

femininity by a task-oriented approach. Gender stereotyping was a relevant outcome of his study.

In a rare study, stereotype lift effect was studied and performance of both the genders exhibited a

male stereotype effect for a mental rotation test by school children of 9 to 10 years (Sarah

Neuburger et al., 2014).

Introduction:

Intelligence and cognitive skills are interrelated characteristics of the human brain. Qualitative

and quantitative powers of analysis are the two abilities by which information gets channelized

and categorized in the brain. The arithmetic logical part of the brain analyses the numerical sets

of information whereas the emotional processor recognizes the social behavioral activities,

intelligence is an accumulation of all these activities. From the very beginning of civilization,

self-concept has been a spiritual yet behavioral viewpoint. The power of cognitive skills or

influence of intelligence has relentlessly struggled to assert the idea of the self-concept from the

very beginning of social structuring. The logical part of the brain has religiously failed to arrest

the elusive perception of self-concept in humans. Another fallacy of human social system is

gender stereotyping; this infectious characteristic has imparted some preset responsibility for

both the genders due to which personal attributes of men have injected some norms and

profoundly ingrained attitudes towards the opposite sex. The sensitiveness of gender stereotyping

has enhanced the attributes of self-concept in men compared to women. In an earlier study by

Torrance in 1963 the effect of gender stereotyping was observed. In The self-concept of

supremacy in numerical and logical ability by men was clearly identified in his experiment. In

the year 2002, Thomas H. Rammsayer re-established self-estimates of exceptional aspects of

intelligence in men which was mainly due to gender-role orientation. Roland Neumann (2015) in

his research work on gender role orientation reassessed the difference in masculinity and

femininity by a task-oriented approach. Gender stereotyping was a relevant outcome of his study.

In a rare study, stereotype lift effect was studied and performance of both the genders exhibited a

male stereotype effect for a mental rotation test by school children of 9 to 10 years (Sarah

Neuburger et al., 2014).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

The effect of self-concept on both the genders, while judging their parent’s intelligence, is an

interesting field of psychology. In the late eighties, Hogan (1978) revealed that irrespective of

category of gender, children rated their father's intelligence considerably higher judged against

their mother. Another study by Furnham et al. in 2002 presented the other side of Hogan’s study.

Using a primary survey with British parents and their wards, it was ascertained that parents

thought, that their sons had higher IQ levels compared to their daughters, especially in spatial

abilities (McKinney & Renk, 2008). In another theory, psychological distress was enlightened by

Elise Whitley et al. in 2011, where the relation between childhood IQ and their intellectual

anarchy in adulthood was correlated. Parent's absence during childhood days, poor economic

condition or adverse social behavior was some of the reasons for behavioral disorders. Self-

concept of this special category of children about their own IQ or their parents IQ resulted in

anomalous conclusion (Mazar, Amir & Ariely, 2008). To assess the loopholes in earlier studies,

20 male participants with an average age of 25.5 years (SD = 4.58 years) and 20 female

participants with an average of 24.1 years (SD = 4.15 years) were interviewed about their own

IQ level and their parent’s (father and mother) IQ level. The results were in line with previous

works (Black, Devereux & Salvanes, 2009). Males estimated their own IQ compared to the self-

estimation of female IQ. Both the genders estimated their father’s IQ greater than that of their

mother’s.

Hypotheses

Four two-tailed hypotheses were tested in the research work. For the first assumption, it was

hypothesized that there was no statistically significant difference in IQ scores of self-estimation

for males and females, irrespective of their genders. Secondly, it was hypothesized that there was

no difference in estimated IQ scores of fathers and mothers by their children. The third null

The effect of self-concept on both the genders, while judging their parent’s intelligence, is an

interesting field of psychology. In the late eighties, Hogan (1978) revealed that irrespective of

category of gender, children rated their father's intelligence considerably higher judged against

their mother. Another study by Furnham et al. in 2002 presented the other side of Hogan’s study.

Using a primary survey with British parents and their wards, it was ascertained that parents

thought, that their sons had higher IQ levels compared to their daughters, especially in spatial

abilities (McKinney & Renk, 2008). In another theory, psychological distress was enlightened by

Elise Whitley et al. in 2011, where the relation between childhood IQ and their intellectual

anarchy in adulthood was correlated. Parent's absence during childhood days, poor economic

condition or adverse social behavior was some of the reasons for behavioral disorders. Self-

concept of this special category of children about their own IQ or their parents IQ resulted in

anomalous conclusion (Mazar, Amir & Ariely, 2008). To assess the loopholes in earlier studies,

20 male participants with an average age of 25.5 years (SD = 4.58 years) and 20 female

participants with an average of 24.1 years (SD = 4.15 years) were interviewed about their own

IQ level and their parent’s (father and mother) IQ level. The results were in line with previous

works (Black, Devereux & Salvanes, 2009). Males estimated their own IQ compared to the self-

estimation of female IQ. Both the genders estimated their father’s IQ greater than that of their

mother’s.

Hypotheses

Four two-tailed hypotheses were tested in the research work. For the first assumption, it was

hypothesized that there was no statistically significant difference in IQ scores of self-estimation

for males and females, irrespective of their genders. Secondly, it was hypothesized that there was

no difference in estimated IQ scores of fathers and mothers by their children. The third null

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

hypothesis was that there will be no statistical difference between estimated IQ scores of

participant’s own and that of their father’s. Fourthly, it was hypothesized that there was no

statistically significant difference in IQ scores of their own scores and the estimate of their

mother’s IQ.

Method

The scholar of the study conducted a workshop where students and teachers of the university

were invited. An advertisement was used for this purpose, describing the aim of the research.

Total 60 aspiring participants turned up in the workshop. The scholar briefed about the entire

study and its purpose. Participants were allowed a break of half an hour to decide and finalize

about their participation in the study. Those who already knew about their and their parent’s IQ

scores were excluded from the scope of the study. Finally, 40 willing participants aged between

18 to 35 years were selected, 20 of them were males and rests were females. The average age of

males was recorded as 25.5 years (SD = 4.58 years) and that of females as 24.1 years (SD = 4.15

years). Maximum age of male participants was 34 years and the minimum was 18 years. The

range of the age of female participants was 18-32 years. The willing participants were given the

debrief sheet to read, and they were made aware of the fact that the study was done under the

supervision of the ethical committee of the university. All of the participants were then

interviewed individually by the scholar. The scholar explained all the participants about the

concept of IQ scores and afterward asked three open-ended questions related to the research

work. The three questions were as follows,

hypothesis was that there will be no statistical difference between estimated IQ scores of

participant’s own and that of their father’s. Fourthly, it was hypothesized that there was no

statistically significant difference in IQ scores of their own scores and the estimate of their

mother’s IQ.

Method

The scholar of the study conducted a workshop where students and teachers of the university

were invited. An advertisement was used for this purpose, describing the aim of the research.

Total 60 aspiring participants turned up in the workshop. The scholar briefed about the entire

study and its purpose. Participants were allowed a break of half an hour to decide and finalize

about their participation in the study. Those who already knew about their and their parent’s IQ

scores were excluded from the scope of the study. Finally, 40 willing participants aged between

18 to 35 years were selected, 20 of them were males and rests were females. The average age of

males was recorded as 25.5 years (SD = 4.58 years) and that of females as 24.1 years (SD = 4.15

years). Maximum age of male participants was 34 years and the minimum was 18 years. The

range of the age of female participants was 18-32 years. The willing participants were given the

debrief sheet to read, and they were made aware of the fact that the study was done under the

supervision of the ethical committee of the university. All of the participants were then

interviewed individually by the scholar. The scholar explained all the participants about the

concept of IQ scores and afterward asked three open-ended questions related to the research

work. The three questions were as follows,

6

1. Please estimate your own IQ score on a scale of 100, where 100 is maximum national average IQ

score.

2. Please estimate your father’s IQ score on a scale of 100, where 100 is maximum national average

IQ score.

3. Please estimate your mother’s IQ score on a scale of 100, where 100 is maximum national

average IQ score.

The answers were recorded and were kept in the secret locker of the university, only to be used

for the purpose of the study.

Results

The IQ scores estimated by the participants were used to test the four null hypotheses of the

study. SPSS software package was used as the instrument of the research work and independent

t-test was chosen as the statistic for comparison.

The self-estimated IQ scores were analyzed to find that average self-estimated score of males

was 121.35 (SD = 6.6) and that of females was 116.9 (SD = 9.67). An independent two-tailed t-

test was performed. The t-value for the difference in estimated IQ score for males and females

was 1.7 with the p-value (0.097) greater than 0.05. There was no significant difference in

estimated IQ scores of the two genders.

The second hypothesis was tested by independent t-test by comparing average estimated IQ

scores for participant's fathers and mothers. Average estimated IQ score for fathers was 117.95

(SD = 7.2) and for mothers was 107.38 (SD = 6.08). The independent t-test value for the t-

statistic was -7.1 with the p-value (0.00) less than 0.05. Hence the null hypothesis was rejected,

1. Please estimate your own IQ score on a scale of 100, where 100 is maximum national average IQ

score.

2. Please estimate your father’s IQ score on a scale of 100, where 100 is maximum national average

IQ score.

3. Please estimate your mother’s IQ score on a scale of 100, where 100 is maximum national

average IQ score.

The answers were recorded and were kept in the secret locker of the university, only to be used

for the purpose of the study.

Results

The IQ scores estimated by the participants were used to test the four null hypotheses of the

study. SPSS software package was used as the instrument of the research work and independent

t-test was chosen as the statistic for comparison.

The self-estimated IQ scores were analyzed to find that average self-estimated score of males

was 121.35 (SD = 6.6) and that of females was 116.9 (SD = 9.67). An independent two-tailed t-

test was performed. The t-value for the difference in estimated IQ score for males and females

was 1.7 with the p-value (0.097) greater than 0.05. There was no significant difference in

estimated IQ scores of the two genders.

The second hypothesis was tested by independent t-test by comparing average estimated IQ

scores for participant's fathers and mothers. Average estimated IQ score for fathers was 117.95

(SD = 7.2) and for mothers was 107.38 (SD = 6.08). The independent t-test value for the t-

statistic was -7.1 with the p-value (0.00) less than 0.05. Hence the null hypothesis was rejected,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

and it was concluded that estimation of mother’s average IQ score was less than father’s

estimated average IQ score.

The average estimated score for IQ of all the participants, irrespective of their genders was

119.13 (SD = 8.5). The t-statistic value for independent t-test comparing estimated own IQ

scores and estimated IQ score of fathers was 0.67 with the p-value (0.51) greater than 0.05.

There was no significant difference was observed between estimated IQ score of own self and

fathers.

The independent t-test was used for comparing estimated IQ scores for participants about their

own self and that about their mothers. The t-value of the test was 7.13 with the p-value (0.00)

less than 0.05. Therefore, a significant difference in average estimated IQ scores of the

participants about their own self and mothers was noticed. The average estimated IQ score of the

participants about their own self-was greater than that of their mothers.

Discussion

The results of the four t-tests revealed some interesting facts for this study. The first test did not

find any significant difference in self-estimated IQ scores of the male and female participants 9

Petrides & Furnham, 2000). The result was in contrast with the study result of A Furnham

(2000), where average self-estimated IQ score of men was higher compared to that of the

women. Barbara Mandell in 2003 conducted a gender comparison for assessing the relationship

between leadership style and emotional intelligence but did not get any significant difference in

scores between the two genders. The scholar got the t-test result similar to that work. The

difference in self-estimated average IQ score for fathers and mothers was significantly different

and it was concluded that estimation of mother’s average IQ score was less than father’s

estimated average IQ score.

The average estimated score for IQ of all the participants, irrespective of their genders was

119.13 (SD = 8.5). The t-statistic value for independent t-test comparing estimated own IQ

scores and estimated IQ score of fathers was 0.67 with the p-value (0.51) greater than 0.05.

There was no significant difference was observed between estimated IQ score of own self and

fathers.

The independent t-test was used for comparing estimated IQ scores for participants about their

own self and that about their mothers. The t-value of the test was 7.13 with the p-value (0.00)

less than 0.05. Therefore, a significant difference in average estimated IQ scores of the

participants about their own self and mothers was noticed. The average estimated IQ score of the

participants about their own self-was greater than that of their mothers.

Discussion

The results of the four t-tests revealed some interesting facts for this study. The first test did not

find any significant difference in self-estimated IQ scores of the male and female participants 9

Petrides & Furnham, 2000). The result was in contrast with the study result of A Furnham

(2000), where average self-estimated IQ score of men was higher compared to that of the

women. Barbara Mandell in 2003 conducted a gender comparison for assessing the relationship

between leadership style and emotional intelligence but did not get any significant difference in

scores between the two genders. The scholar got the t-test result similar to that work. The

difference in self-estimated average IQ score for fathers and mothers was significantly different

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

and resembled with the study results of Hogan (1978). The trend of judging fathers as more

intelligent, compared to mothers was still visible in the study. The comparative study between

self-estimated IQ scores and estimated fathers IQ scores indicated that participants in the study

were a bit egotist, there was no significant difference between participants self-estimated score

and estimated scores of their fathers. James E.Marcia (2017) worked on identity crisis of

humans in the age of adolescence. The discoveries revealed that attitude problems of a person in

his/her adolescence force the third type of result. The third null hypothesis of the study got failed

to be rejected based on the value of the statistics. The fourth t-test result was obvious and in line

with the previous works (Higgins, 1987). Participants estimated their own IQ scores significantly

greater than that of their mothers’.

The null hypothesis was significantly rejected, which was about the equality of estimated own IQ

scores with that of their mothers. The last result reflected the parenting pattern of the parents for

the participants as well as the psychological well being in the adolescence.

The study was short of addressing some issues. The cultural background of the participants was

not considered, neither, information about their childhood was taken. The peer attachment in the

age of adolescence was also not considered (Huesmann, Dubow & Boxer, 2009). The age group

of the participants was such that effect of these criterions was important in the self-estimation of

IQ of their fathers and mothers. Self-estimation of multiple types of intelligence, especially

emotional and logical traits were not included in the scope of the work (Behm-Morawitz &

Mastro, 2009). The collected set of data, therefore, was random in nature and thus the results of

independent t-tests reflected a general trend, earlier obtained in various studies. In 2016, Anthony

J. Amorose conducted a research work on the psychology of sport and exercise. The self-

determined motivation of the high school athletes and individual assessment of their father,

and resembled with the study results of Hogan (1978). The trend of judging fathers as more

intelligent, compared to mothers was still visible in the study. The comparative study between

self-estimated IQ scores and estimated fathers IQ scores indicated that participants in the study

were a bit egotist, there was no significant difference between participants self-estimated score

and estimated scores of their fathers. James E.Marcia (2017) worked on identity crisis of

humans in the age of adolescence. The discoveries revealed that attitude problems of a person in

his/her adolescence force the third type of result. The third null hypothesis of the study got failed

to be rejected based on the value of the statistics. The fourth t-test result was obvious and in line

with the previous works (Higgins, 1987). Participants estimated their own IQ scores significantly

greater than that of their mothers’.

The null hypothesis was significantly rejected, which was about the equality of estimated own IQ

scores with that of their mothers. The last result reflected the parenting pattern of the parents for

the participants as well as the psychological well being in the adolescence.

The study was short of addressing some issues. The cultural background of the participants was

not considered, neither, information about their childhood was taken. The peer attachment in the

age of adolescence was also not considered (Huesmann, Dubow & Boxer, 2009). The age group

of the participants was such that effect of these criterions was important in the self-estimation of

IQ of their fathers and mothers. Self-estimation of multiple types of intelligence, especially

emotional and logical traits were not included in the scope of the work (Behm-Morawitz &

Mastro, 2009). The collected set of data, therefore, was random in nature and thus the results of

independent t-tests reflected a general trend, earlier obtained in various studies. In 2016, Anthony

J. Amorose conducted a research work on the psychology of sport and exercise. The self-

determined motivation of the high school athletes and individual assessment of their father,

9

mother and playing coach was collected. The results went to show the positive effect of sports on

the personal and professional relations. The participants of this study were within the age

bracket of 18 to 34. Therefore, these important factors could have influenced their perception

about their parents. Any future study regarding self-estimated IQ score comparison has a scope

to include these above-mentioned factors (Duell et al., 2016).

mother and playing coach was collected. The results went to show the positive effect of sports on

the personal and professional relations. The participants of this study were within the age

bracket of 18 to 34. Therefore, these important factors could have influenced their perception

about their parents. Any future study regarding self-estimated IQ score comparison has a scope

to include these above-mentioned factors (Duell et al., 2016).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

Reference

Marcia, J. E. (2017). Ego-Identity Status: Relationship to Change in Self-Esteem. Social

Encounters: Contributions to Social Interaction, 340.

Duell, N., Steinberg, L., Chein, J., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Lei, C., ... & Lansford, J. E.

(2016). Interaction of reward seeking and self-regulation in the prediction of risk taking:

A cross-national test of the dual systems model. Developmental psychology, 52(10),

1593.

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2000). Gender differences in measured and self-estimated trait

emotional intelligence. Sex roles, 42(5-6), 449-461.

McKinney, C., & Renk, K. (2008). Differential parenting between mothers and fathers:

Implications for late adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 29(6), 806-827.

Huesmann, L. R., Dubow, E. F., & Boxer, P. (2009). Continuity of aggression from childhood to

early adulthood as a predictor of life outcomes: Implications for the adolescent‐limited

and life‐course‐persistent models. Aggressive behavior, 35(2), 136-149.

Hogan, H. W. (1978). I.Q. Self-estimates of males and females. Journal of Social Psychology,

106, 137-138.

Higgins, L. T. (1987, February 10). The unknowing of intelligence. The Guardian.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-

concept maintenance. Journal of marketing research, 45(6), 633-644.

Behm-Morawitz, E., & Mastro, D. (2009). The effects of the sexualization of female video game

characters on gender stereotyping and female self-concept. Sex roles, 61(11-12), 808-823.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2009). Like father, like son? A note on the

intergenerational transmission of IQ scores. Economics Letters, 105(1), 138-140.

Reference

Marcia, J. E. (2017). Ego-Identity Status: Relationship to Change in Self-Esteem. Social

Encounters: Contributions to Social Interaction, 340.

Duell, N., Steinberg, L., Chein, J., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Lei, C., ... & Lansford, J. E.

(2016). Interaction of reward seeking and self-regulation in the prediction of risk taking:

A cross-national test of the dual systems model. Developmental psychology, 52(10),

1593.

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2000). Gender differences in measured and self-estimated trait

emotional intelligence. Sex roles, 42(5-6), 449-461.

McKinney, C., & Renk, K. (2008). Differential parenting between mothers and fathers:

Implications for late adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 29(6), 806-827.

Huesmann, L. R., Dubow, E. F., & Boxer, P. (2009). Continuity of aggression from childhood to

early adulthood as a predictor of life outcomes: Implications for the adolescent‐limited

and life‐course‐persistent models. Aggressive behavior, 35(2), 136-149.

Hogan, H. W. (1978). I.Q. Self-estimates of males and females. Journal of Social Psychology,

106, 137-138.

Higgins, L. T. (1987, February 10). The unknowing of intelligence. The Guardian.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-

concept maintenance. Journal of marketing research, 45(6), 633-644.

Behm-Morawitz, E., & Mastro, D. (2009). The effects of the sexualization of female video game

characters on gender stereotyping and female self-concept. Sex roles, 61(11-12), 808-823.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2009). Like father, like son? A note on the

intergenerational transmission of IQ scores. Economics Letters, 105(1), 138-140.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

Noble, H., Whitley, E., Norton, S., & Thompson, M. (2011). A study of preoperative factors

associated with a poor outcome following laparoscopic bile duct exploration. Surgical

endoscopy, 25(1), 130-139.

Noble, H., Whitley, E., Norton, S., & Thompson, M. (2011). A study of preoperative factors

associated with a poor outcome following laparoscopic bile duct exploration. Surgical

endoscopy, 25(1), 130-139.

12

Appendix

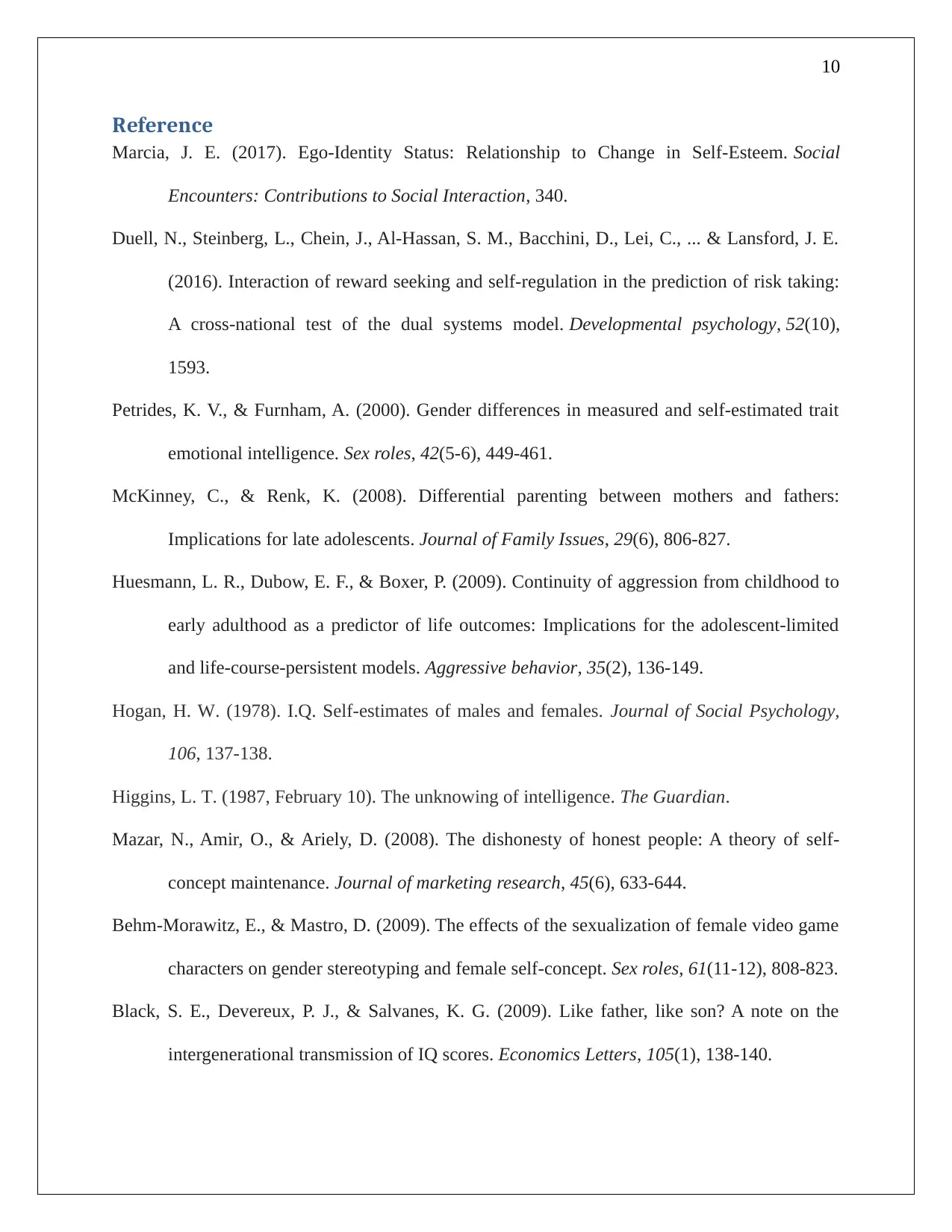

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for Participants

Table 2: Own IQ Gender wise

Gender N Mean

Std.

Deviation

Std.

Error

Mean

Q1_Self Male 20 121.35 6.596 1.475

Femal

e

20 116.90 9.673 2.163

Table 3: Father vs Mother IQ

Subject_Father_Mothe

r N Mean

Std.

Deviation

Std.

Error

Mean

Score_Q2 mother 40 107.38 6.075 .961

father 40 117.95 7.197 1.138

Table 4: Father vs Own IQ

Subject_Self_Father N Mean

Std.

Deviation

Std.

Error

Mean

Score_Q3 self 40 119.13 8.477 1.340

father 40 117.95 7.197 1.138

Table 5: Own vs Mother IQ

Subject_Self_Mother N Mean

Std.

Deviation

Std.

Error

Mean

Score_Q4 Self 40 119.13 8.477 1.340

Mother 40 107.38 6.075 .961

N Minimum Maximum Mean

Std.

Deviation

Age 40 18 34 24.80 4.375

Participant 40 1 40 20.50 11.690

Valid N

(listwise)

40

Appendix

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for Participants

Table 2: Own IQ Gender wise

Gender N Mean

Std.

Deviation

Std.

Error

Mean

Q1_Self Male 20 121.35 6.596 1.475

Femal

e

20 116.90 9.673 2.163

Table 3: Father vs Mother IQ

Subject_Father_Mothe

r N Mean

Std.

Deviation

Std.

Error

Mean

Score_Q2 mother 40 107.38 6.075 .961

father 40 117.95 7.197 1.138

Table 4: Father vs Own IQ

Subject_Self_Father N Mean

Std.

Deviation

Std.

Error

Mean

Score_Q3 self 40 119.13 8.477 1.340

father 40 117.95 7.197 1.138

Table 5: Own vs Mother IQ

Subject_Self_Mother N Mean

Std.

Deviation

Std.

Error

Mean

Score_Q4 Self 40 119.13 8.477 1.340

Mother 40 107.38 6.075 .961

N Minimum Maximum Mean

Std.

Deviation

Age 40 18 34 24.80 4.375

Participant 40 1 40 20.50 11.690

Valid N

(listwise)

40

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

13

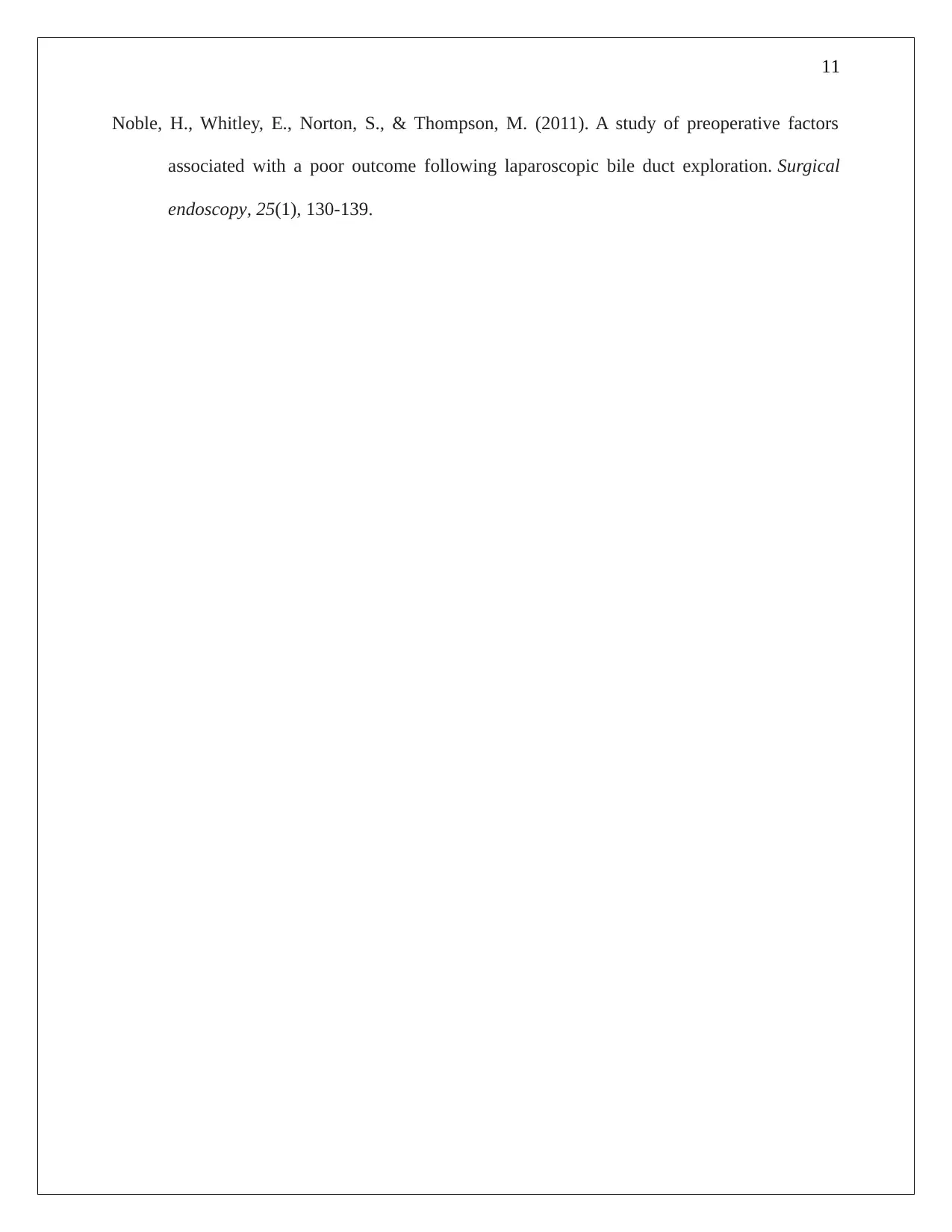

Table 6: Independent Samples Test for Own IQ Gender wise

Own IQ Gender wise

Levene's Test

for Equality of

Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig.

(2-

tailed)

Mean

Difference

Std. Error

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Lower Upper

Q1_Sel

f

Equal

variances

assumed

3.812 .058 1.700 38 .097 4.450 2.618 -.850 9.750

Equal

variances

not

assumed

1.700 33.52

7 .098 4.450 2.618 -.873 9.773

Table 7: Independent Samples Test for Mother vs Father IQ

Mother vs Father IQ

Levene's Test

for Equality of

Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig.

(2-

tailed)

Mean

Difference

Std. Error

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Lower Upper

Score_Q2

Equal

variances

assumed

2.472 .120 -

7.102 78 .000 -10.575 1.489 -13.540 -7.610

Equal

variances

not

assumed

-

7.102 75.863 .000 -10.575 1.489 -13.541 -7.609

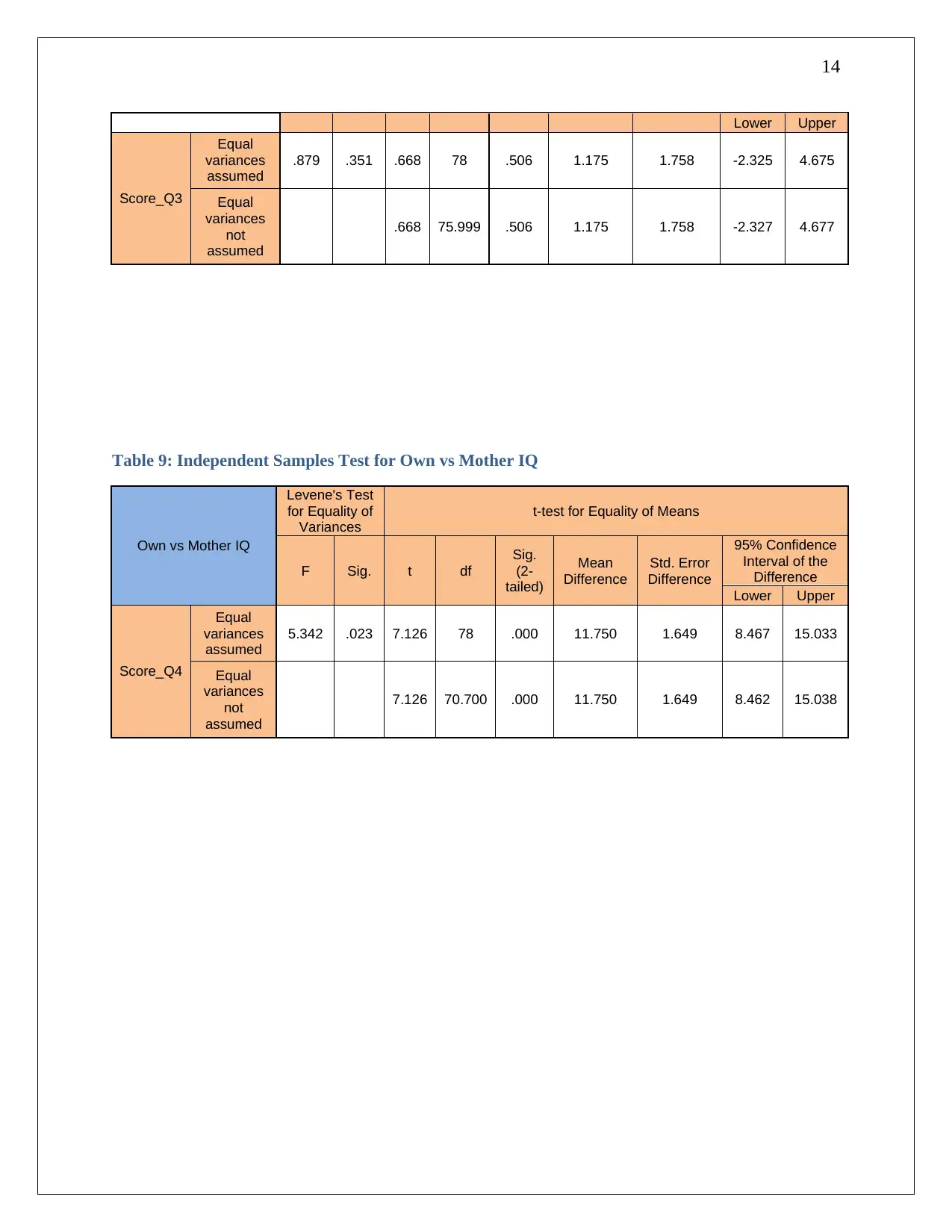

Table 8: Independent Samples Test for Father vs Own IQ

Father vs Own IQ Levene's Test

for Equality of

Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df Sig.

(2-

tailed)

Mean

Difference

Std. Error

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Table 6: Independent Samples Test for Own IQ Gender wise

Own IQ Gender wise

Levene's Test

for Equality of

Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig.

(2-

tailed)

Mean

Difference

Std. Error

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Lower Upper

Q1_Sel

f

Equal

variances

assumed

3.812 .058 1.700 38 .097 4.450 2.618 -.850 9.750

Equal

variances

not

assumed

1.700 33.52

7 .098 4.450 2.618 -.873 9.773

Table 7: Independent Samples Test for Mother vs Father IQ

Mother vs Father IQ

Levene's Test

for Equality of

Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig.

(2-

tailed)

Mean

Difference

Std. Error

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Lower Upper

Score_Q2

Equal

variances

assumed

2.472 .120 -

7.102 78 .000 -10.575 1.489 -13.540 -7.610

Equal

variances

not

assumed

-

7.102 75.863 .000 -10.575 1.489 -13.541 -7.609

Table 8: Independent Samples Test for Father vs Own IQ

Father vs Own IQ Levene's Test

for Equality of

Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df Sig.

(2-

tailed)

Mean

Difference

Std. Error

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

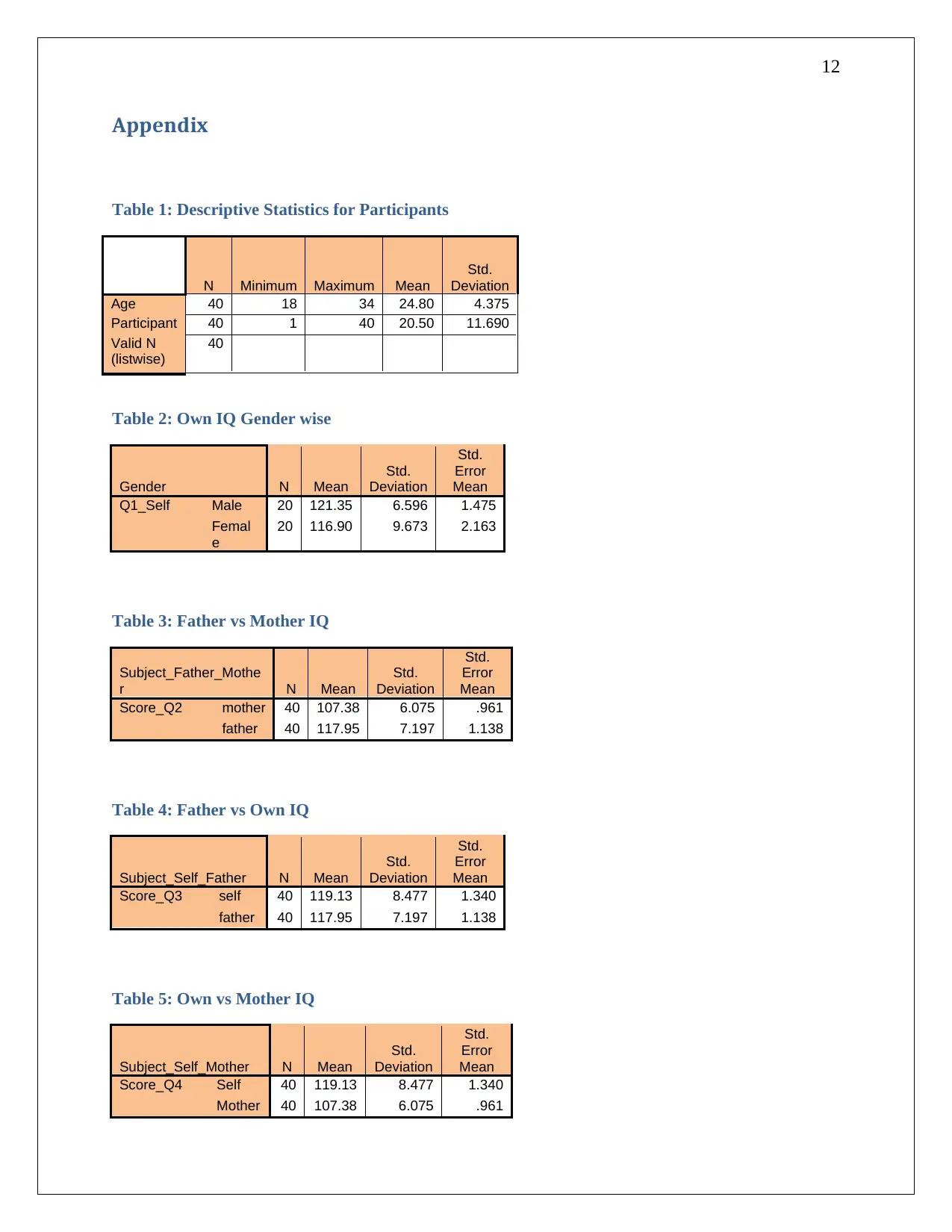

14

Lower Upper

Score_Q3

Equal

variances

assumed

.879 .351 .668 78 .506 1.175 1.758 -2.325 4.675

Equal

variances

not

assumed

.668 75.999 .506 1.175 1.758 -2.327 4.677

Table 9: Independent Samples Test for Own vs Mother IQ

Own vs Mother IQ

Levene's Test

for Equality of

Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig.

(2-

tailed)

Mean

Difference

Std. Error

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Lower Upper

Score_Q4

Equal

variances

assumed

5.342 .023 7.126 78 .000 11.750 1.649 8.467 15.033

Equal

variances

not

assumed

7.126 70.700 .000 11.750 1.649 8.462 15.038

Lower Upper

Score_Q3

Equal

variances

assumed

.879 .351 .668 78 .506 1.175 1.758 -2.325 4.675

Equal

variances

not

assumed

.668 75.999 .506 1.175 1.758 -2.327 4.677

Table 9: Independent Samples Test for Own vs Mother IQ

Own vs Mother IQ

Levene's Test

for Equality of

Variances

t-test for Equality of Means

F Sig. t df

Sig.

(2-

tailed)

Mean

Difference

Std. Error

Difference

95% Confidence

Interval of the

Difference

Lower Upper

Score_Q4

Equal

variances

assumed

5.342 .023 7.126 78 .000 11.750 1.649 8.467 15.033

Equal

variances

not

assumed

7.126 70.700 .000 11.750 1.649 8.462 15.038

1 out of 14

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.