Internal Governance and Real Earnings Management

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/18

|73

|28682

|2

AI Summary

This research paper examines the impact of internal governance on the extent of real earnings management in U.S. corporations. The study finds that the extent of real earnings management decreases with key subordinate executives' horizon and influence. The results are robust to alternative measures of internal governance and various approaches to address potential endogeneity. The paper contributes to the literature by shedding light on how the members of the management team work together in shaping financial reporting quality.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Singapore Management University

Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management U

Research Collection School Of Accountancy School of Accountancy

7-2016

Internal Governance and Real Earnings

Management

Qiang CHENG

Singapore Management University, qcheng@smu.edu.sg

Jimmy LEE

Singapore Management University, jimmylee@smu.edu.sg

Terry J. SHEVLIN

University of California-Irvine

Follow this and additional works at: http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soa_research

Part of the Accounting Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Com

and the Corporate Finance Commons

This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Accountancy at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore

University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School Of Accountancy by an authorized administrator of Institu

Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email libIR@smu.edu.sg.

Citation

CHENG, Qiang; LEE, Jimmy; and SHEVLIN, Terry J.. Internal Governance and Real Earnings Management. (2016). Acco

Review. 91, (4), 1051-1085. Research Collection School Of Accountancy.

Available at: http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soa_research/987

Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management U

Research Collection School Of Accountancy School of Accountancy

7-2016

Internal Governance and Real Earnings

Management

Qiang CHENG

Singapore Management University, qcheng@smu.edu.sg

Jimmy LEE

Singapore Management University, jimmylee@smu.edu.sg

Terry J. SHEVLIN

University of California-Irvine

Follow this and additional works at: http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soa_research

Part of the Accounting Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Com

and the Corporate Finance Commons

This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Accountancy at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore

University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School Of Accountancy by an authorized administrator of Institu

Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email libIR@smu.edu.sg.

Citation

CHENG, Qiang; LEE, Jimmy; and SHEVLIN, Terry J.. Internal Governance and Real Earnings Management. (2016). Acco

Review. 91, (4), 1051-1085. Research Collection School Of Accountancy.

Available at: http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soa_research/987

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Internal governance and real earnings management

Qiang Cheng

qcheng@smu.edu.sg

Singapore Management University

Jimmy Lee

jimmylee@smu.edu.sg

Singapore Management University

Terry Shevlin

tshevlin@uci.edu

University of California at Irvine

August 2015

ABSTRACT

We examine whether internal governance affects the extent of real earnings management in U.S.

corporations. Internal governance refers to the process through which key subordinate executives

provide checks and balances in the organization and affect corporate decisions. Using the

number of years to retirement to capture key subordinate executives’ horizon incentives and

using their compensation relative to CEO compensation to capture their influence within the

firm, we find that the extent of real earnings management decreases with key subordinate

executives’ horizon and influence. The results are robust to alternative measures of internal

governance and to various approaches used to address potential endogeneity including a

difference-in-differences approach. In cross-sectional analyses, we find that the effect of internal

governance is stronger for firms with more complex operations where key subordinate

executives’ contribution is higher, is enhanced when CEOs are less powerful, is weaker when the

capital markets benefit of meeting or beating earnings benchmarks is higher, and is stronger in

the post-SOX period. This paper contributes to the literature by examining how internal

governance affects the extent of real earnings management and by shedding light on how the

members of the management team work together in shaping financial reporting quality.

Key words: internal governance, real earnings management, top management team

JEL codes: G32, M40

We thank Xia Chen, Richard Frankel, Weili Ge, Frank Hodge, Bin Ke, Jim Naughton, Dan Segal, Holly Skaife,

Terry Warfield, Anne Wyatt, Huai Zhang, and workshop and conference participants at the 2012 Singapore three-

school research conference, the 2013 Financial Accounting and Reporting Section mid-year conference, the 2013

University of Technology, Sydney Conference, the 2013 AAA annual meeting, Southern Methodist University, and

the University of Wisconsin – Madison for helpful comments. Cheng and Lee thank the School of Accountancy

Research Center (SOAR) at Singapore Management University for financial support. Shevlin acknowledges

financial support from the Paul Merage School of Business at the University of California-Irvine.

Published in Accounting Review, In-Press, 2015 August

http://dx.doi.org/10.2308/accr-51275

Qiang Cheng

qcheng@smu.edu.sg

Singapore Management University

Jimmy Lee

jimmylee@smu.edu.sg

Singapore Management University

Terry Shevlin

tshevlin@uci.edu

University of California at Irvine

August 2015

ABSTRACT

We examine whether internal governance affects the extent of real earnings management in U.S.

corporations. Internal governance refers to the process through which key subordinate executives

provide checks and balances in the organization and affect corporate decisions. Using the

number of years to retirement to capture key subordinate executives’ horizon incentives and

using their compensation relative to CEO compensation to capture their influence within the

firm, we find that the extent of real earnings management decreases with key subordinate

executives’ horizon and influence. The results are robust to alternative measures of internal

governance and to various approaches used to address potential endogeneity including a

difference-in-differences approach. In cross-sectional analyses, we find that the effect of internal

governance is stronger for firms with more complex operations where key subordinate

executives’ contribution is higher, is enhanced when CEOs are less powerful, is weaker when the

capital markets benefit of meeting or beating earnings benchmarks is higher, and is stronger in

the post-SOX period. This paper contributes to the literature by examining how internal

governance affects the extent of real earnings management and by shedding light on how the

members of the management team work together in shaping financial reporting quality.

Key words: internal governance, real earnings management, top management team

JEL codes: G32, M40

We thank Xia Chen, Richard Frankel, Weili Ge, Frank Hodge, Bin Ke, Jim Naughton, Dan Segal, Holly Skaife,

Terry Warfield, Anne Wyatt, Huai Zhang, and workshop and conference participants at the 2012 Singapore three-

school research conference, the 2013 Financial Accounting and Reporting Section mid-year conference, the 2013

University of Technology, Sydney Conference, the 2013 AAA annual meeting, Southern Methodist University, and

the University of Wisconsin – Madison for helpful comments. Cheng and Lee thank the School of Accountancy

Research Center (SOAR) at Singapore Management University for financial support. Shevlin acknowledges

financial support from the Paul Merage School of Business at the University of California-Irvine.

Published in Accounting Review, In-Press, 2015 August

http://dx.doi.org/10.2308/accr-51275

1

I. INTRODUCTION

We examine whether internal governance affects the extent of real earnings management. 1

Internal governance refers to the process through which key subordinate executives provide

checks and balances in the organization and affect corporate decisions.2 We focus on key

subordinate executives, or specifically the top four executives with the highest compensation

other than the CEO, because we hypothesize that they are the most likely group of employees

that have both the incentive and the ability to influence the CEO in corporate decisions. As

argued in Acharya, Myers, and Rajan (2011), key subordinate executives have strong incentives

not to take actions that increase short-term performance at the expense of long-term firm value.

This tradeoff between current and future firm value is particularly salient in the case of real

earnings management because overproduction and cutting of R&D expenditures are costly and

can reduce the long-term value of the firm (e.g., Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal 2005; Bhojraj,

Hribar, Picconi, and McInnis 2009; Cohen and Zarowin 2010). In addition, we expect these key

subordinate executives to have more direct impact on corporate decisions, such as research and

development, production, and other activities that affect operating cash flows, and as a result, the

extent of real earnings management. In contrast, these executives, with the exception of the CFO,

have little direct influence on the accrual process. Thus, we focus on real earnings management

in this paper.

The motivation for the research question is two-fold. First, the majority of the papers in the

literature explicitly or implicitly assume that the CEO is the sole decision maker for financial

1 Following Roychowdhury (2006, 336), we define real earnings management as “management actions that deviate

from normal business practices, undertaken with the primary objective of meeting certain earnings thresholds.”

Some papers in the literature refer to “real earnings management” as “real activities management.”

2 We use the term “internal governance” to be consistent with some of the closely related studies (e.g., Acharya et al.

2011). We refer to governance mechanisms other than the monitoring by the key subordinate executives broadly as

“other governance mechanisms.”

I. INTRODUCTION

We examine whether internal governance affects the extent of real earnings management. 1

Internal governance refers to the process through which key subordinate executives provide

checks and balances in the organization and affect corporate decisions.2 We focus on key

subordinate executives, or specifically the top four executives with the highest compensation

other than the CEO, because we hypothesize that they are the most likely group of employees

that have both the incentive and the ability to influence the CEO in corporate decisions. As

argued in Acharya, Myers, and Rajan (2011), key subordinate executives have strong incentives

not to take actions that increase short-term performance at the expense of long-term firm value.

This tradeoff between current and future firm value is particularly salient in the case of real

earnings management because overproduction and cutting of R&D expenditures are costly and

can reduce the long-term value of the firm (e.g., Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal 2005; Bhojraj,

Hribar, Picconi, and McInnis 2009; Cohen and Zarowin 2010). In addition, we expect these key

subordinate executives to have more direct impact on corporate decisions, such as research and

development, production, and other activities that affect operating cash flows, and as a result, the

extent of real earnings management. In contrast, these executives, with the exception of the CFO,

have little direct influence on the accrual process. Thus, we focus on real earnings management

in this paper.

The motivation for the research question is two-fold. First, the majority of the papers in the

literature explicitly or implicitly assume that the CEO is the sole decision maker for financial

1 Following Roychowdhury (2006, 336), we define real earnings management as “management actions that deviate

from normal business practices, undertaken with the primary objective of meeting certain earnings thresholds.”

Some papers in the literature refer to “real earnings management” as “real activities management.”

2 We use the term “internal governance” to be consistent with some of the closely related studies (e.g., Acharya et al.

2011). We refer to governance mechanisms other than the monitoring by the key subordinate executives broadly as

“other governance mechanisms.”

2

reporting quality, which includes both accrual and real earnings management.3 Focusing only on

the CEO does not provide a complete picture because firm management is typically a shared

effort of all top executives (Finkelstein 1992). Recent literature starts to examine how CFOs

affect the quality of financial reporting (e.g., Jiang, Petroni, and Wang 2010; Feng, Ge, Luo, and

Shevlin 2011). However, the impact of other executives has been largely overlooked. As

discussed briefly below and in detail in Section II, recent studies argue that subordinate

executives usually have longer decision horizons and they can influence corporate decisions

through various means. We hypothesize that differential preferences arising from differential

horizons can affect the extent of real earnings management.

Second, while there are studies focusing on the impact of various corporate governance

mechanisms on corporate decisions (e.g., board independence and institutional ownership), little

is known about whether there are checks and balances within the management team. This lack of

knowledge is an important omission because control is not just imposed from the top-down or

from the outside, but also from the bottom-up (Fama 1980).

Key subordinate executives usually care more about the long-term firm value than the CEO

for several important reasons. First, as argued in Acharya et al. (2011), some of these executives

desire to become the CEO in the future. As candidates for the CEO position in the future, key

subordinate executives care about cash flows that the firm can generate in the future, which are

in turn a function of the firm’s current investments. As a result, these executives are less likely to

sacrifice long-term investments to meet short-term earnings targets. Second, key subordinate

executives have more to lose relative to their total wealth from corporate underperformance than

the CEO. They are usually younger and have more remaining years of employment. As such, the

3 Some papers pool all top five executives covered in the ExecuComp database together and examine their collective

influence on financial reporting (e.g., Cheng and Warfield 2005). The distinct impact of other executives is not

identified in such analyses.

reporting quality, which includes both accrual and real earnings management.3 Focusing only on

the CEO does not provide a complete picture because firm management is typically a shared

effort of all top executives (Finkelstein 1992). Recent literature starts to examine how CFOs

affect the quality of financial reporting (e.g., Jiang, Petroni, and Wang 2010; Feng, Ge, Luo, and

Shevlin 2011). However, the impact of other executives has been largely overlooked. As

discussed briefly below and in detail in Section II, recent studies argue that subordinate

executives usually have longer decision horizons and they can influence corporate decisions

through various means. We hypothesize that differential preferences arising from differential

horizons can affect the extent of real earnings management.

Second, while there are studies focusing on the impact of various corporate governance

mechanisms on corporate decisions (e.g., board independence and institutional ownership), little

is known about whether there are checks and balances within the management team. This lack of

knowledge is an important omission because control is not just imposed from the top-down or

from the outside, but also from the bottom-up (Fama 1980).

Key subordinate executives usually care more about the long-term firm value than the CEO

for several important reasons. First, as argued in Acharya et al. (2011), some of these executives

desire to become the CEO in the future. As candidates for the CEO position in the future, key

subordinate executives care about cash flows that the firm can generate in the future, which are

in turn a function of the firm’s current investments. As a result, these executives are less likely to

sacrifice long-term investments to meet short-term earnings targets. Second, key subordinate

executives have more to lose relative to their total wealth from corporate underperformance than

the CEO. They are usually younger and have more remaining years of employment. As such, the

3 Some papers pool all top five executives covered in the ExecuComp database together and examine their collective

influence on financial reporting (e.g., Cheng and Warfield 2005). The distinct impact of other executives is not

identified in such analyses.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

3

potential loss of income for failing to find a comparable job in the future is high for younger

executives and increases with horizon. Third, Fama (1980) argues that in general, a manager’s

outside opportunity wage depends on other managers’, including the CEO’s, actions and firm

performance. This effect can motivate the key subordinate executives to be more long-term

oriented and to exert monitoring on the CEO.

Not only do key subordinate executives have incentives to increase long-term firm value,

they also have the means to influence corporate decisions toward their preferences. Prior

research argues that because key subordinate executives’ effort is an important determinant of

current cash flows and the CEO’s welfare, the CEO will consider key subordinate executives’

preferences when making important corporate decisions; otherwise, subordinate executives

might not work hard, hence reducing current and future cash flows and the CEO’s welfare (Allen

and Gale 2000; Acharya et al. 2011).

The above discussion implies that the effectiveness of internal governance depends on the

decision horizon of key subordinate executives and the influence they have on the CEO. In this

paper, we use the number of years until retirement age (assumed to be 65) to capture these

executives’ decision horizon and we use the level of their compensation relative to the CEO’s to

capture their influence. We expect that the longer the horizon and the higher the relative

compensation, the more effective is internal governance, and the lower the extent of real earnings

management. Of course, subordinate executives might have the same incentives as the CEO to

increase short-term performance at the expense of long-term value. Or, subordinate executives

might be afraid of the consequences of disobeying the CEO (e.g., being demoted or fired) and

hence do not exert monitoring on the CEO.4 In addition, it is possible that the key subordinate

4 See Feng et al. (2011) for evidence on the role of powerful CEOs in influencing CFOs to undertake material

accounting manipulations.

potential loss of income for failing to find a comparable job in the future is high for younger

executives and increases with horizon. Third, Fama (1980) argues that in general, a manager’s

outside opportunity wage depends on other managers’, including the CEO’s, actions and firm

performance. This effect can motivate the key subordinate executives to be more long-term

oriented and to exert monitoring on the CEO.

Not only do key subordinate executives have incentives to increase long-term firm value,

they also have the means to influence corporate decisions toward their preferences. Prior

research argues that because key subordinate executives’ effort is an important determinant of

current cash flows and the CEO’s welfare, the CEO will consider key subordinate executives’

preferences when making important corporate decisions; otherwise, subordinate executives

might not work hard, hence reducing current and future cash flows and the CEO’s welfare (Allen

and Gale 2000; Acharya et al. 2011).

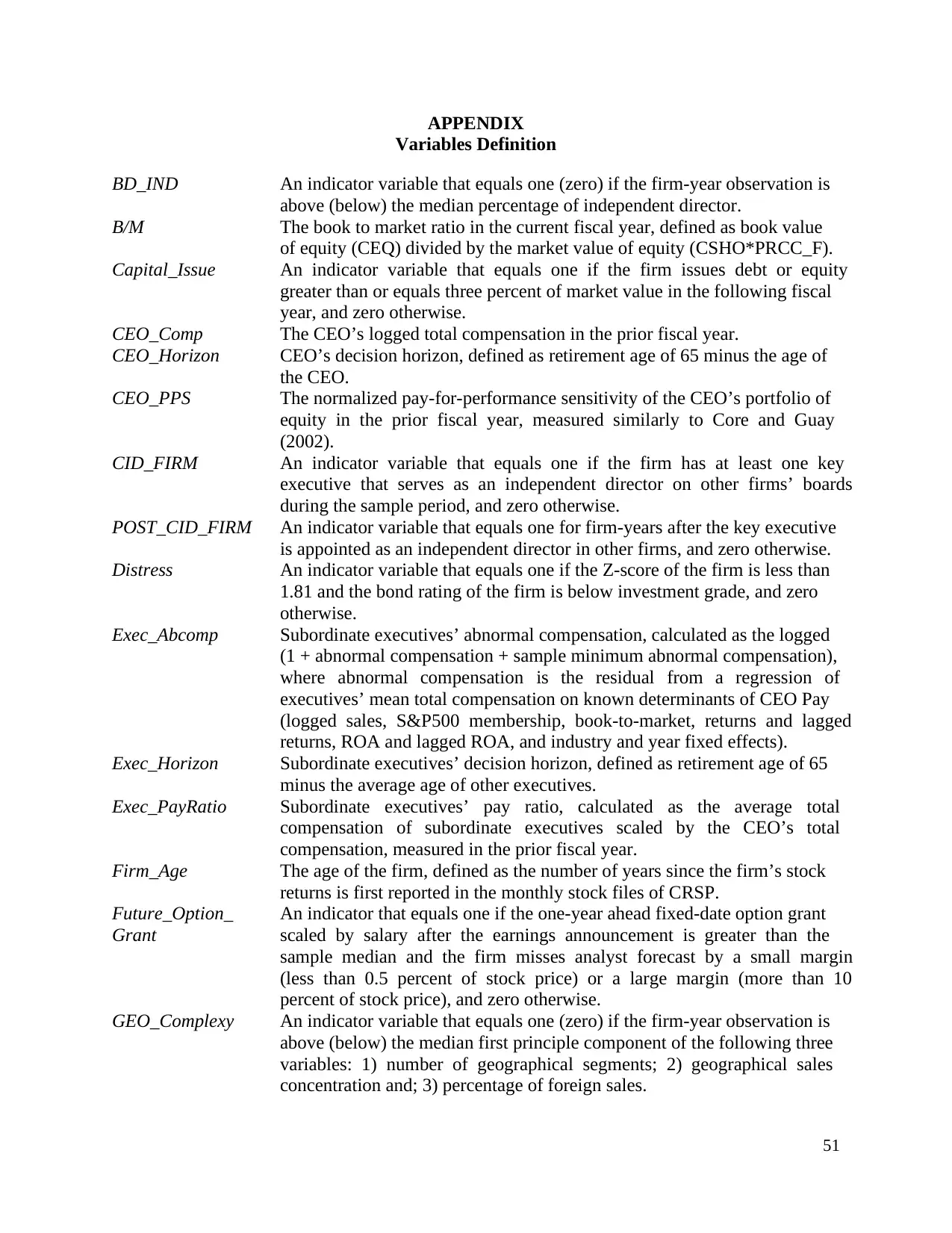

The above discussion implies that the effectiveness of internal governance depends on the

decision horizon of key subordinate executives and the influence they have on the CEO. In this

paper, we use the number of years until retirement age (assumed to be 65) to capture these

executives’ decision horizon and we use the level of their compensation relative to the CEO’s to

capture their influence. We expect that the longer the horizon and the higher the relative

compensation, the more effective is internal governance, and the lower the extent of real earnings

management. Of course, subordinate executives might have the same incentives as the CEO to

increase short-term performance at the expense of long-term value. Or, subordinate executives

might be afraid of the consequences of disobeying the CEO (e.g., being demoted or fired) and

hence do not exert monitoring on the CEO.4 In addition, it is possible that the key subordinate

4 See Feng et al. (2011) for evidence on the role of powerful CEOs in influencing CFOs to undertake material

accounting manipulations.

4

executives are in a tournament or competition for the CEO’s job with external candidates; as a

result, they could undertake real earnings management to increase short-term earnings and/or to

curry favor with the CEO who likely plays an important role in selecting his/her successor. These

possibilities introduce tension to our research question and thus whether internal governance can

effectively reduce the extent of real earnings management is an empirical question.

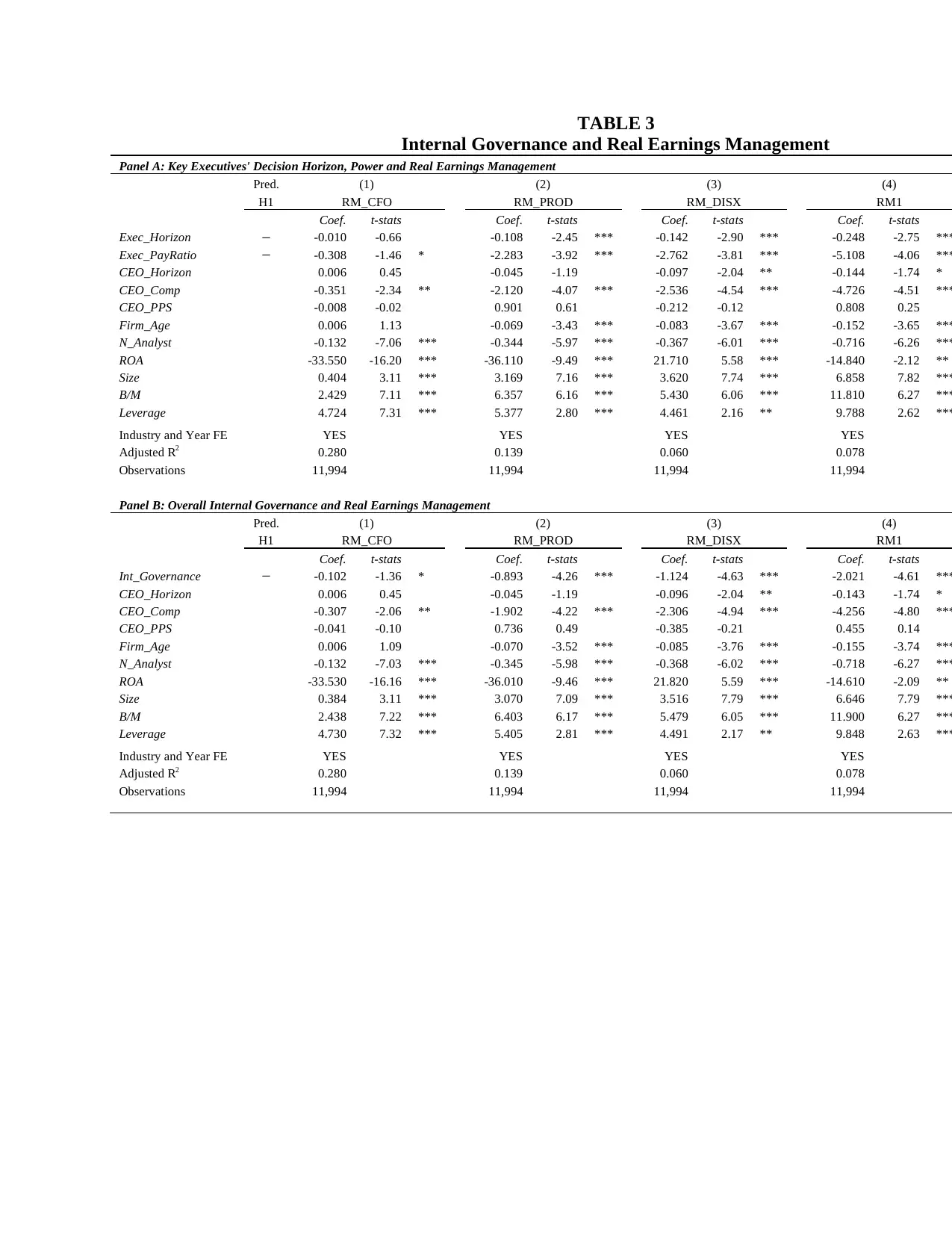

We test our hypothesis using 11,994 firm-year observations from the S&P 1500 firms in

the period 1993-2011. The empirical results are consistent with our prediction. We find that the

extent of real earnings management decreases with subordinate executives’ horizon and relative

compensation. The results hold after we control for CEO and firm characteristics that might

affect the extent of real earnings management (e.g., CEO horizon, CEO compensation structure,

firm age, analyst coverage, firm size, firm performance, leverage, firm growth opportunities, and

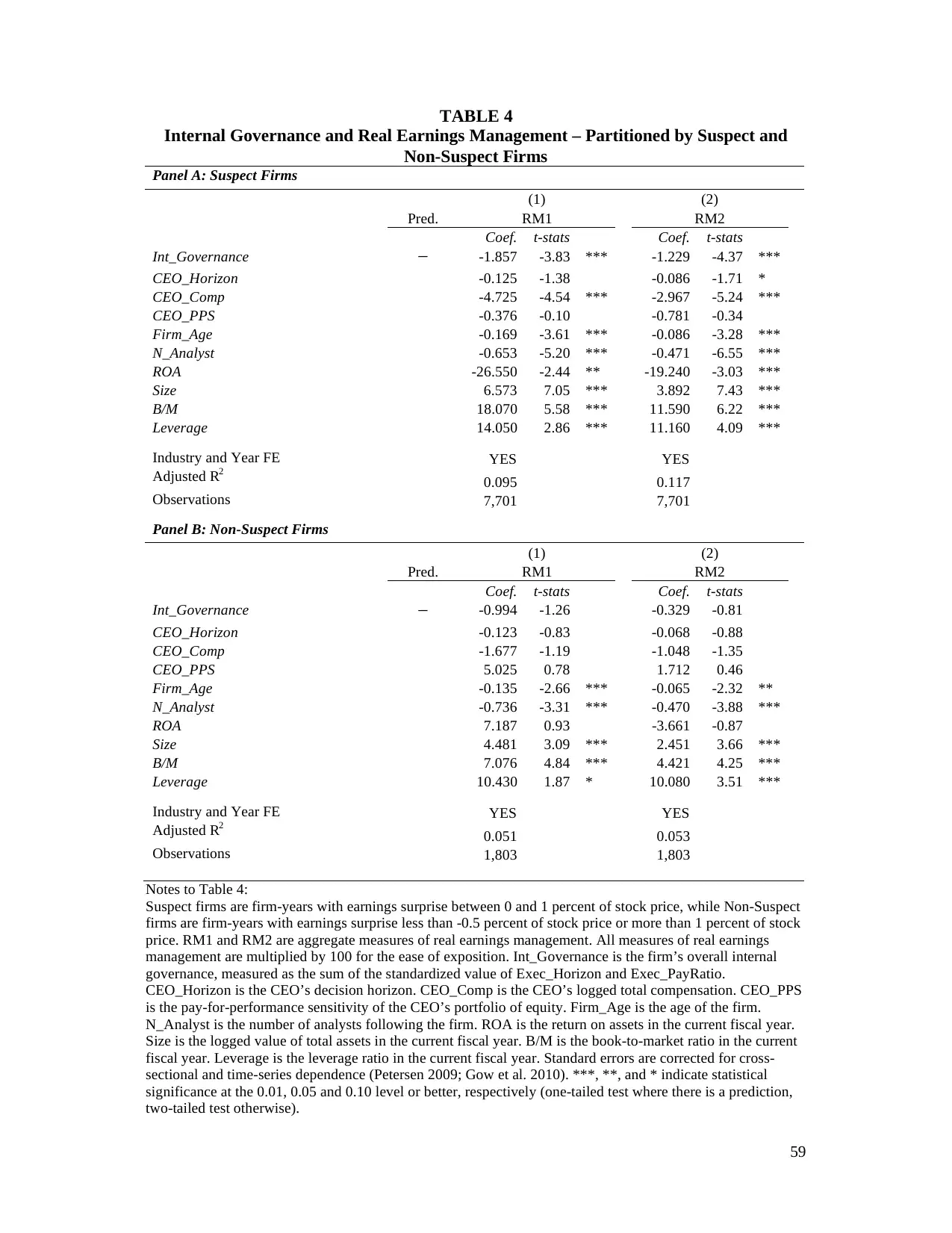

other governance mechanisms). When we split the sample firms into suspect firms – the

subsample of firms that meet or just beat analysts’ forecasts – and other firms, we find that the

results only hold for the suspect firms, where CEOs have incentives to engage in upward real

earnings management. We do not find results for the other firms. The remaining analyses are

thus based on the sample of suspect firms.

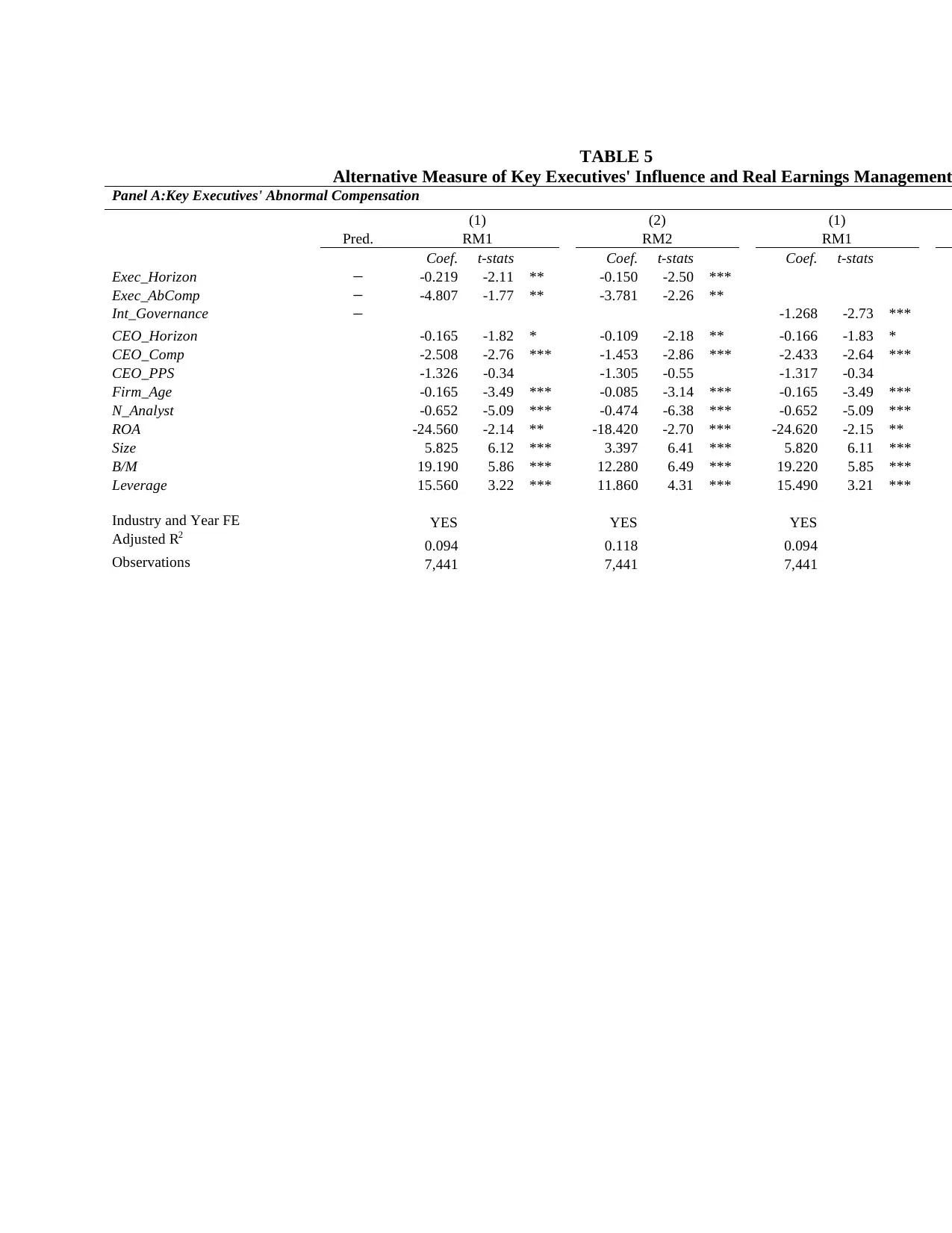

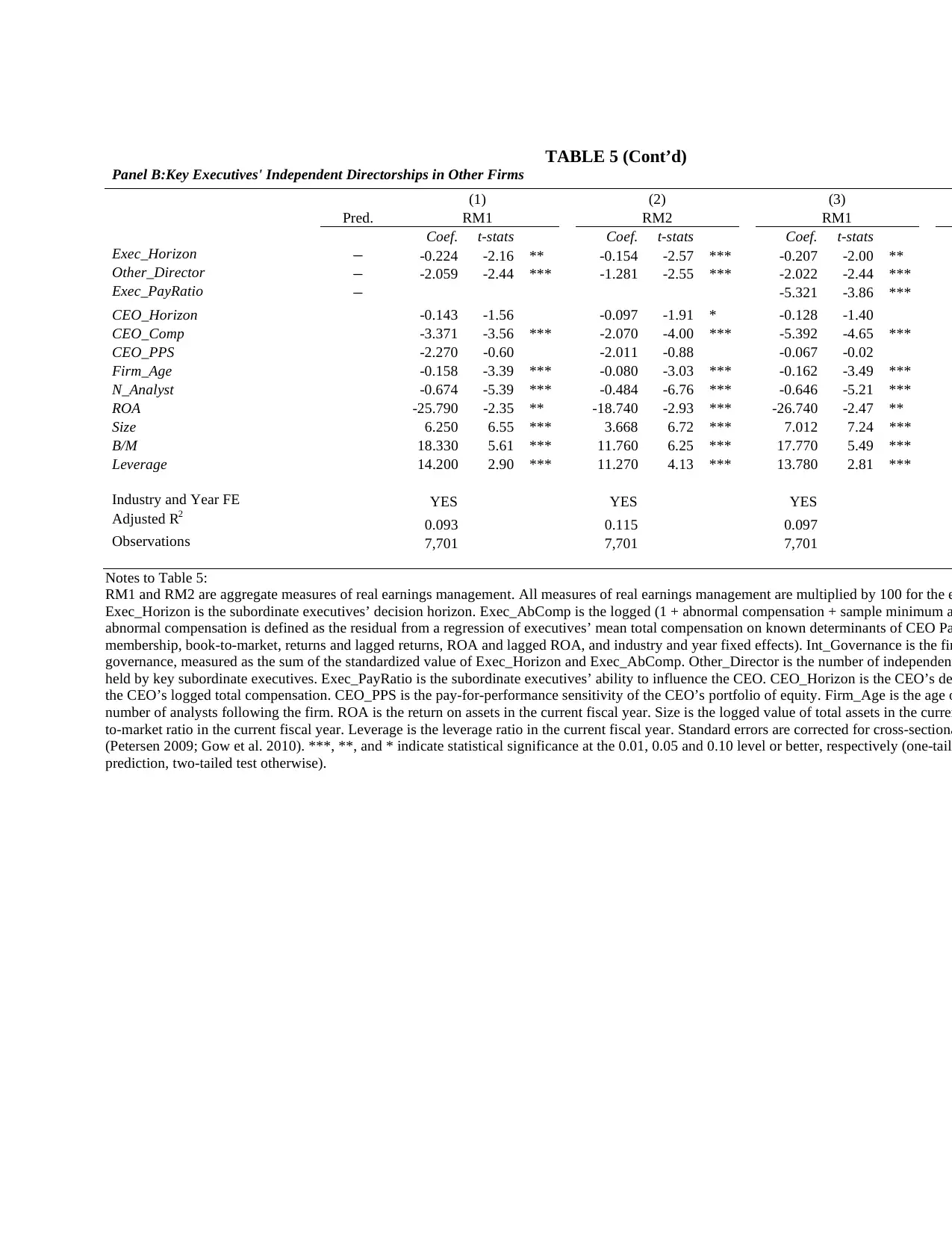

In the main analyses, we use the relative compensation of the key subordinate executives to

capture their ability to influence the CEO on key corporate decisions. An alternative

interpretation of our results is that this proxy captures CEO entrenchment, not internal

governance per se, and entrenched CEOs engage in more real earnings management. In an

additional analysis, we use two alternative measures to investigate the robustness of our results

and to address this alternative explanation. More specifically, we use the abnormal compensation

of subordinate executives and whether the subordinate executives sit on other companies’ boards

executives are in a tournament or competition for the CEO’s job with external candidates; as a

result, they could undertake real earnings management to increase short-term earnings and/or to

curry favor with the CEO who likely plays an important role in selecting his/her successor. These

possibilities introduce tension to our research question and thus whether internal governance can

effectively reduce the extent of real earnings management is an empirical question.

We test our hypothesis using 11,994 firm-year observations from the S&P 1500 firms in

the period 1993-2011. The empirical results are consistent with our prediction. We find that the

extent of real earnings management decreases with subordinate executives’ horizon and relative

compensation. The results hold after we control for CEO and firm characteristics that might

affect the extent of real earnings management (e.g., CEO horizon, CEO compensation structure,

firm age, analyst coverage, firm size, firm performance, leverage, firm growth opportunities, and

other governance mechanisms). When we split the sample firms into suspect firms – the

subsample of firms that meet or just beat analysts’ forecasts – and other firms, we find that the

results only hold for the suspect firms, where CEOs have incentives to engage in upward real

earnings management. We do not find results for the other firms. The remaining analyses are

thus based on the sample of suspect firms.

In the main analyses, we use the relative compensation of the key subordinate executives to

capture their ability to influence the CEO on key corporate decisions. An alternative

interpretation of our results is that this proxy captures CEO entrenchment, not internal

governance per se, and entrenched CEOs engage in more real earnings management. In an

additional analysis, we use two alternative measures to investigate the robustness of our results

and to address this alternative explanation. More specifically, we use the abnormal compensation

of subordinate executives and whether the subordinate executives sit on other companies’ boards

5

as alternative proxies for their influence. Our inferences based on these two alternative proxies

remain the same.

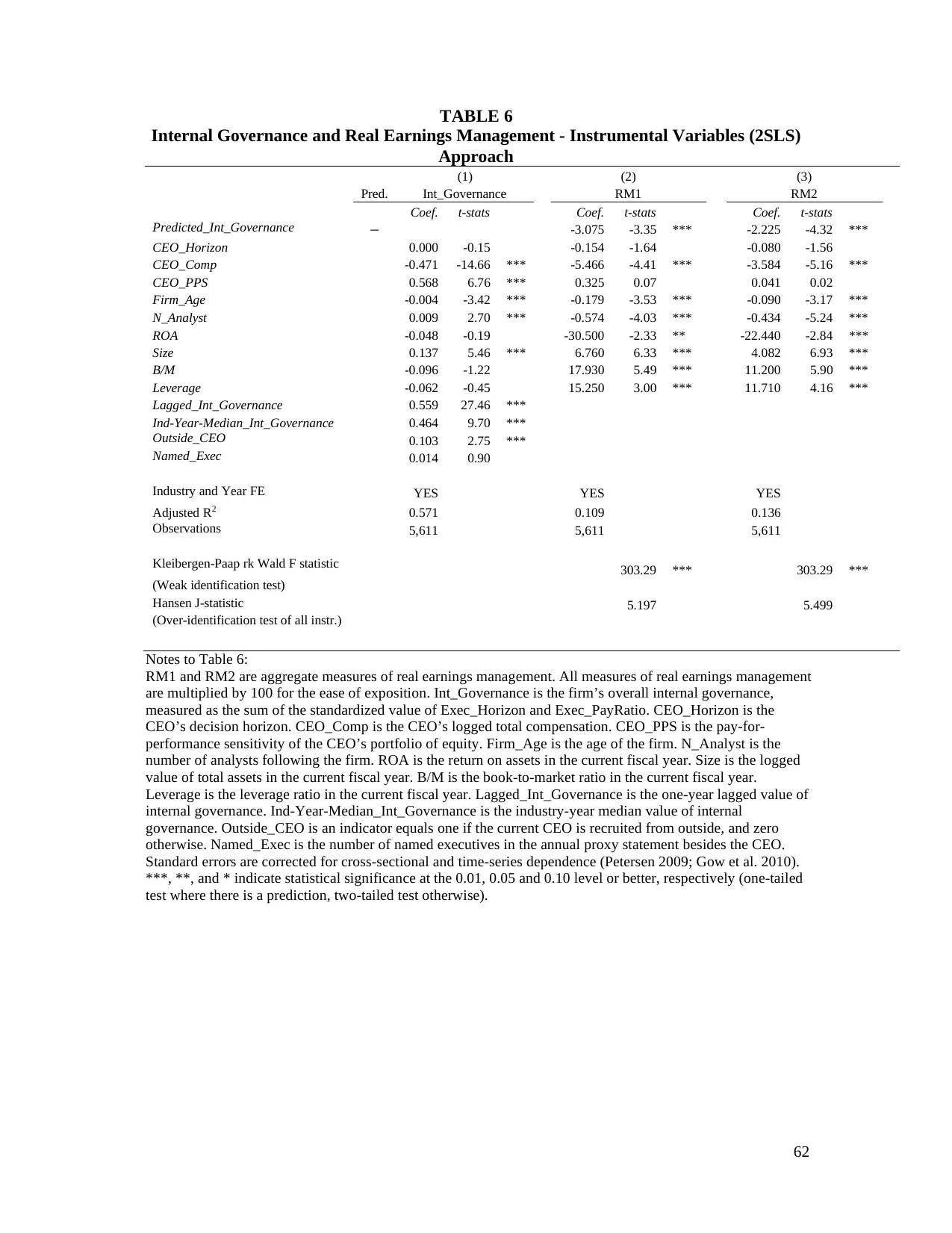

As with many corporate governance studies, we recognize that our analyses might be

subject to endogeneity concerns because firms’ internal governance is arguably endogenously

determined. The factors that affect the strength of internal governance might also affect the

extent of real earnings management. We address this endogeneity concern using a number of

approaches. First, we use the lagged values of internal governance in all our analyses and include

a comprehensive list of control variables that are likely correlated with both internal governance

and the extent of real earnings management. Second, we use an instrumental variable approach to

further control for potential endogeneity concerns. Specifically, following related prior studies

(e.g., Coles, Daniel, and Naveen 2006; Boone, Field, Karpoff, and Raheja 2007; Kale, Reis, and

Venkateswaran 2009; Bebchuk, Cremers, and Peyer 2011), we use the two-year lagged value of

internal governance, the industry-year median of internal governance, the number of named

executives in the proxy statement, and an indicator for outside CEOs as instruments. Our

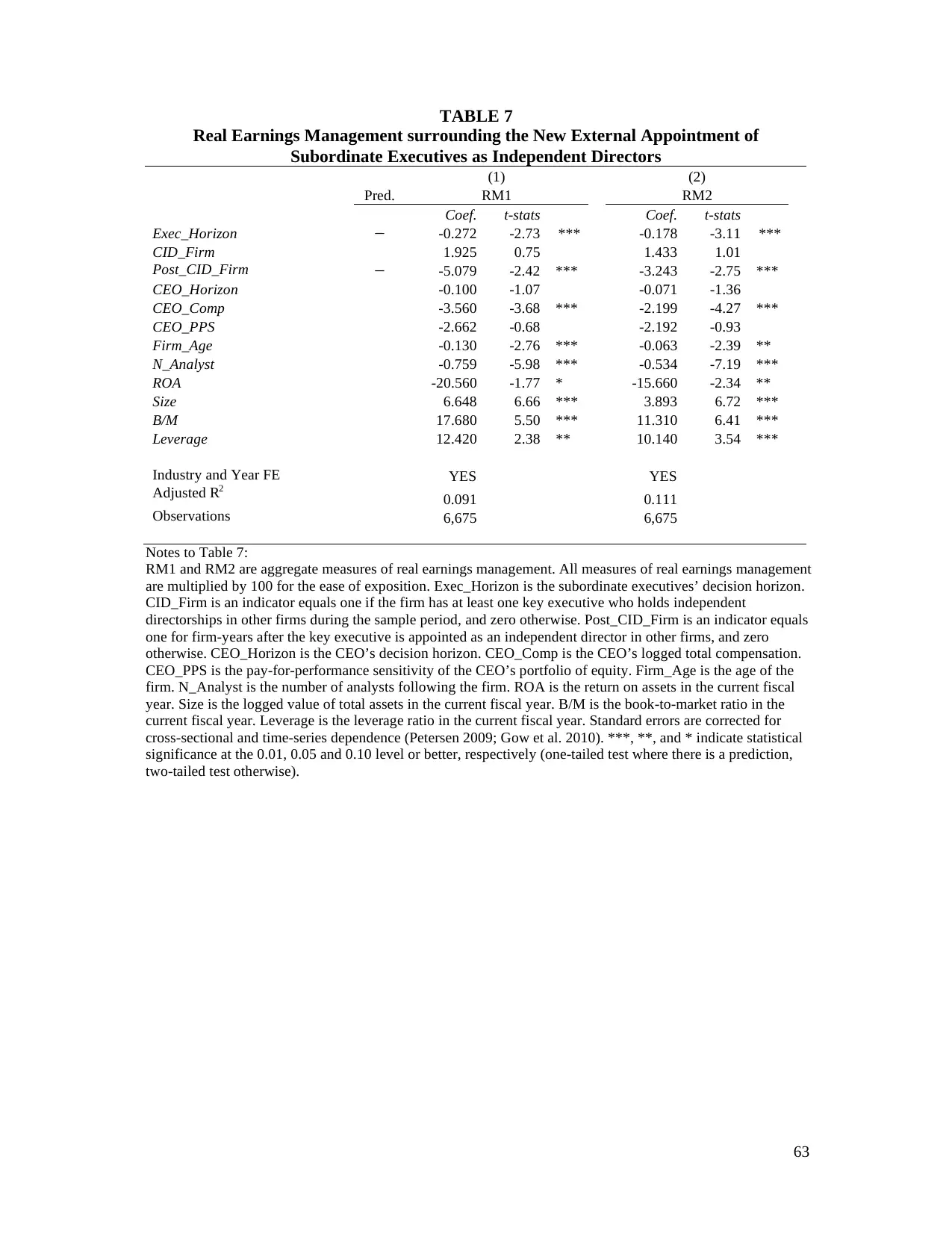

inferences remain the same. Third, we adopt a difference-in-differences design by examining the

impact on the extent of real earnings management of the appointment of a subordinate executive

as an independent director of another company (one of our alternative proxies for internal

governance). We find that before such appointments, firms that later on have subordinate

executives serving as independent directors of other companies do not differ in the extent of real

earnings management from the firms without such subordinate executives. However, after such

appointments, firms with subordinate executives serving as independent directors experience a

significant decrease in the extent of real earnings management compared to other firms. These

as alternative proxies for their influence. Our inferences based on these two alternative proxies

remain the same.

As with many corporate governance studies, we recognize that our analyses might be

subject to endogeneity concerns because firms’ internal governance is arguably endogenously

determined. The factors that affect the strength of internal governance might also affect the

extent of real earnings management. We address this endogeneity concern using a number of

approaches. First, we use the lagged values of internal governance in all our analyses and include

a comprehensive list of control variables that are likely correlated with both internal governance

and the extent of real earnings management. Second, we use an instrumental variable approach to

further control for potential endogeneity concerns. Specifically, following related prior studies

(e.g., Coles, Daniel, and Naveen 2006; Boone, Field, Karpoff, and Raheja 2007; Kale, Reis, and

Venkateswaran 2009; Bebchuk, Cremers, and Peyer 2011), we use the two-year lagged value of

internal governance, the industry-year median of internal governance, the number of named

executives in the proxy statement, and an indicator for outside CEOs as instruments. Our

inferences remain the same. Third, we adopt a difference-in-differences design by examining the

impact on the extent of real earnings management of the appointment of a subordinate executive

as an independent director of another company (one of our alternative proxies for internal

governance). We find that before such appointments, firms that later on have subordinate

executives serving as independent directors of other companies do not differ in the extent of real

earnings management from the firms without such subordinate executives. However, after such

appointments, firms with subordinate executives serving as independent directors experience a

significant decrease in the extent of real earnings management compared to other firms. These

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

6

tests indicate that our results are not driven by the potential endogeneity concern.5

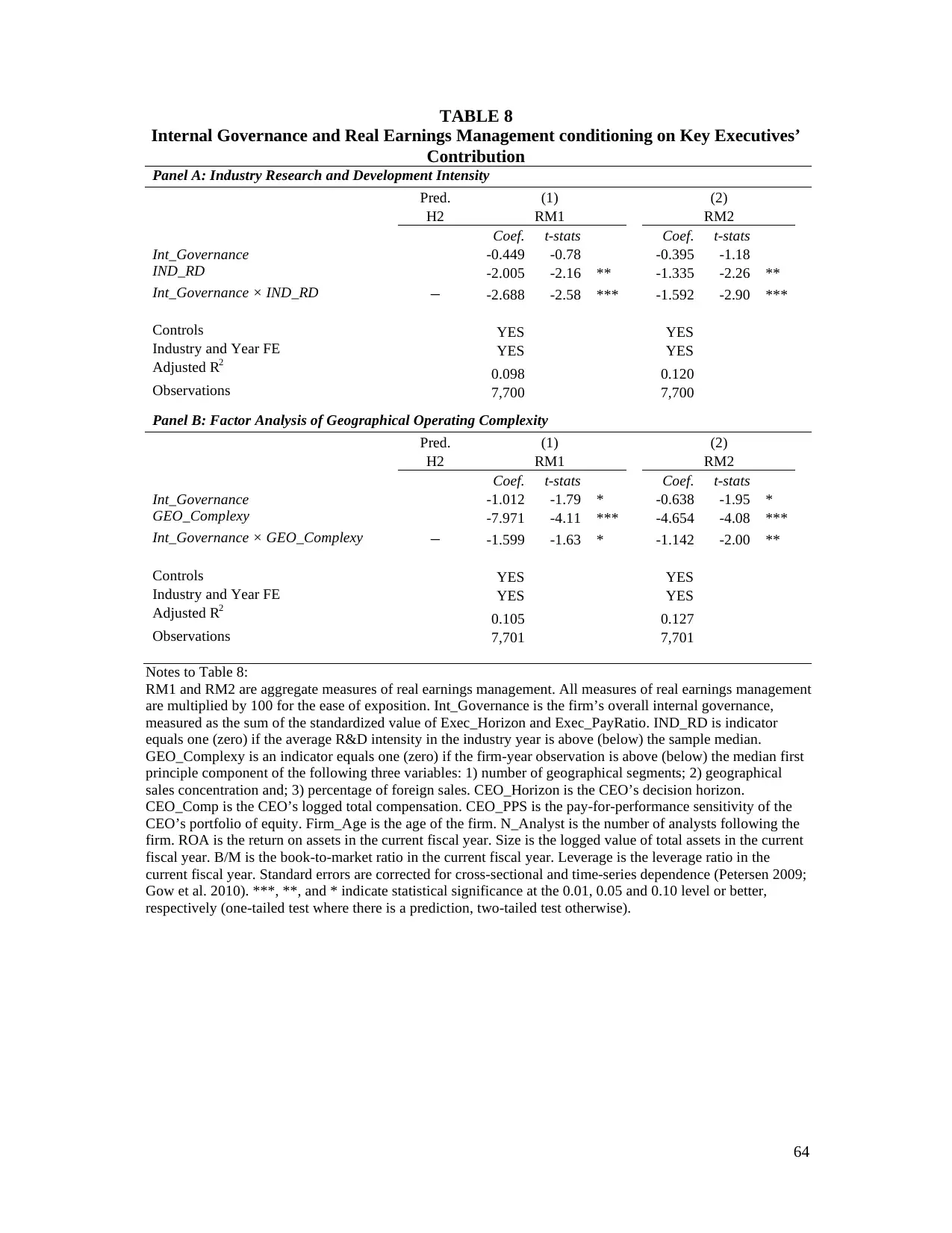

To corroborate the inference from the main analyses, we conduct a series of cross-sectional

analyses. First, key subordinate executives’ ability to influence the CEO’s decision hinges on

their contribution to firm performance and we argue that their contribution is greater when the

firm’s operations are more complex. Accordingly, we expect that the impact of internal

governance is higher when operation complexity is higher. We use industry R&D intensity and a

common factor based on the number of geographical segments, geographical sales concentration,

and foreign sales to capture the complexity of a firm’s operations. The results are consistent with

our prediction that the impact of internal governance is stronger when operation complexity is

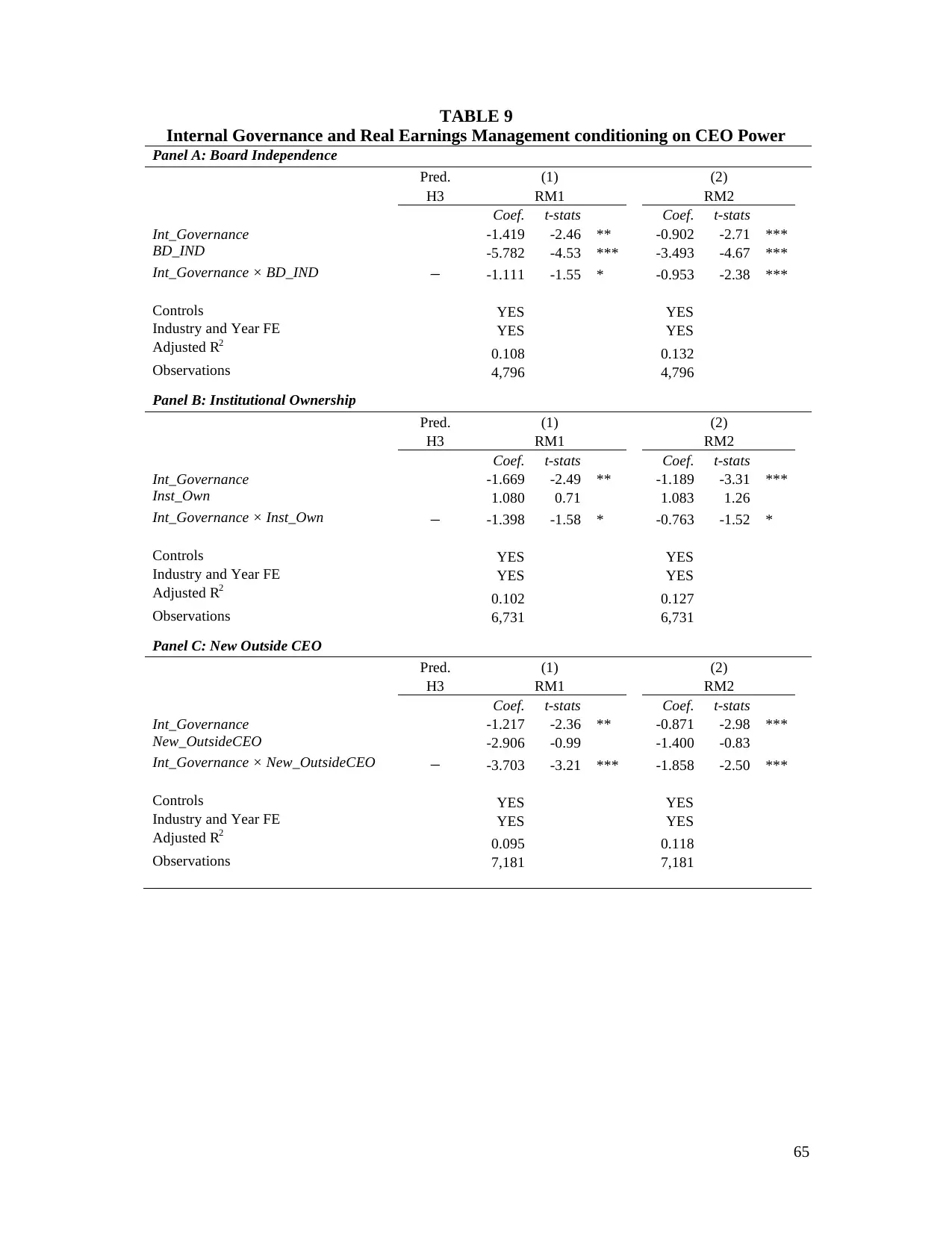

higher. Second, we find that the effect of internal governance is stronger when the CEO is more

effectively monitored and less powerful, proxied for by higher board independence, higher

institutional ownership, and an indicator for newly appointed outside CEOs. This result also

indicates that other governance mechanisms can enhance subordinate executives’ ability to

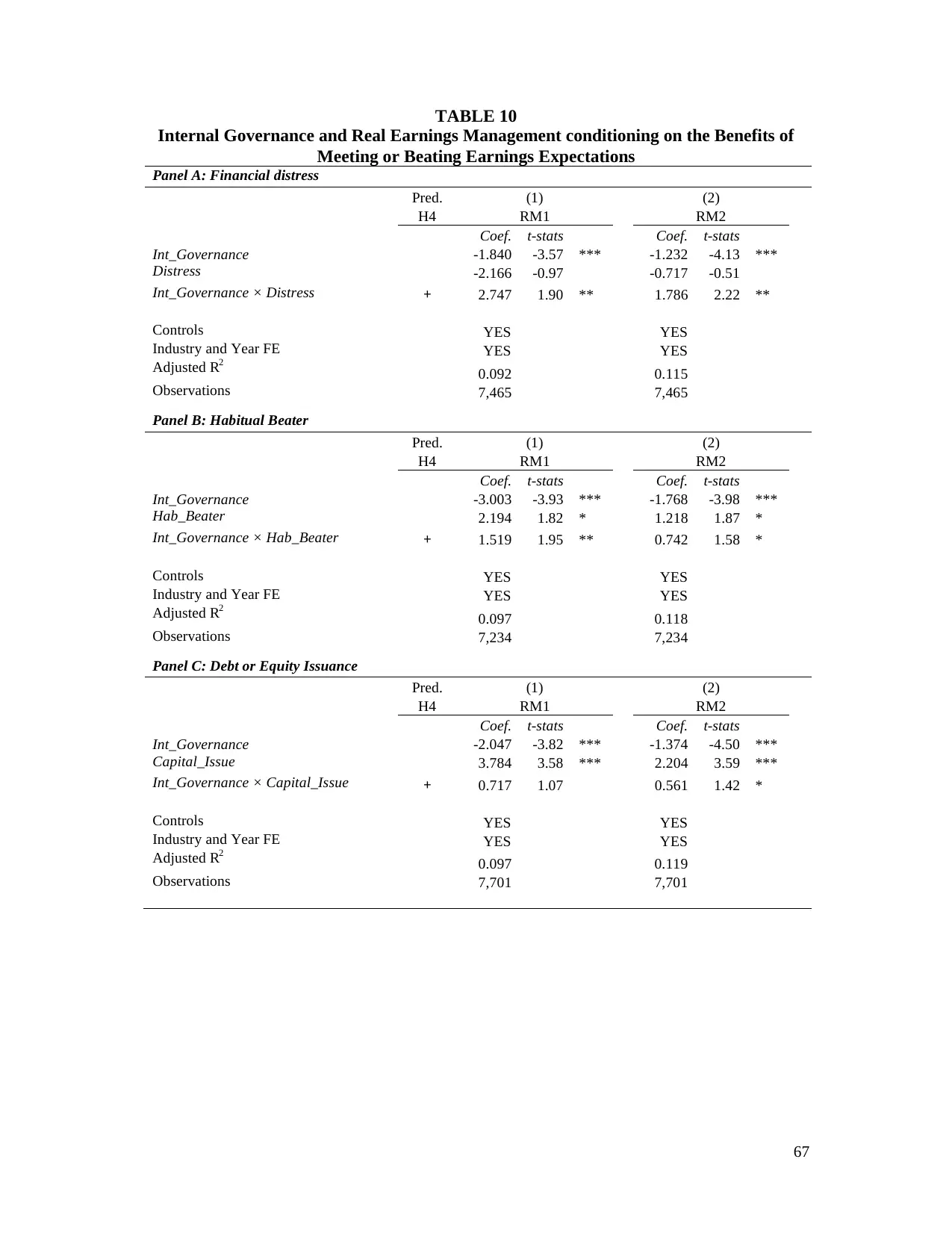

influence the CEO’s decisions. Third, we find that the effect of internal governance is attenuated

for firms in financial distress, for firms that routinely meet or beat earnings targets, and for firms

with upcoming financing activities, presumably because subordinate executives have weaker

incentives to constrain real earnings management when the capital markets benefit of meeting or

beating earnings benchmarks is higher.

We also conduct a series of additional tests to ensure the robustness of our results and to

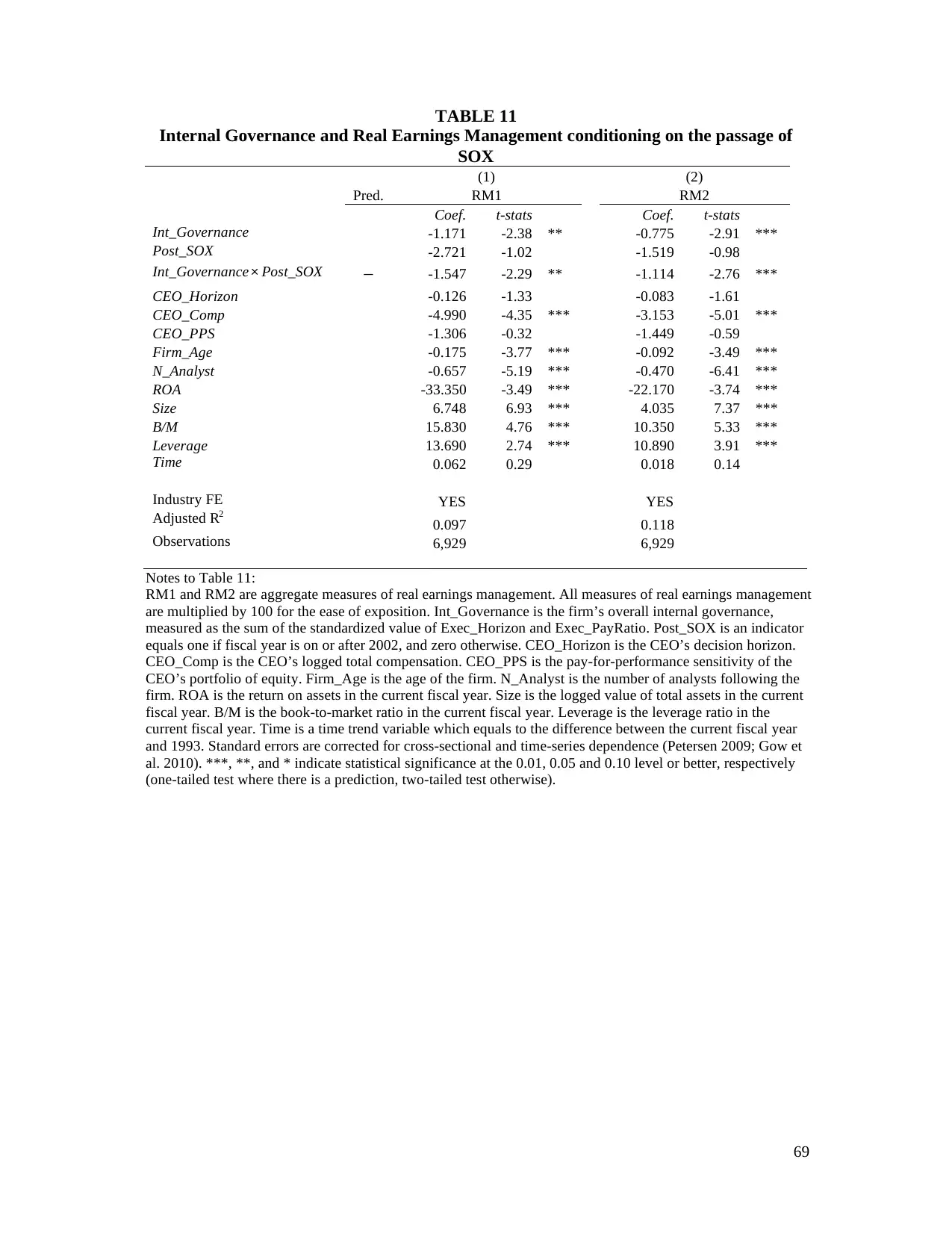

provide additional insights. First, the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act exerts a shock to firms’

governance (e.g., requiring higher board independence) and the extent of real earnings

management (Cohen, Dey, and Lys 2008). As such, we expect internal governance to be more

5 Our cross-sectional analyses also mitigate the endogeneity concern because it is arguably harder for an omitted

variable to explain both our main and cross-sectional findings.

tests indicate that our results are not driven by the potential endogeneity concern.5

To corroborate the inference from the main analyses, we conduct a series of cross-sectional

analyses. First, key subordinate executives’ ability to influence the CEO’s decision hinges on

their contribution to firm performance and we argue that their contribution is greater when the

firm’s operations are more complex. Accordingly, we expect that the impact of internal

governance is higher when operation complexity is higher. We use industry R&D intensity and a

common factor based on the number of geographical segments, geographical sales concentration,

and foreign sales to capture the complexity of a firm’s operations. The results are consistent with

our prediction that the impact of internal governance is stronger when operation complexity is

higher. Second, we find that the effect of internal governance is stronger when the CEO is more

effectively monitored and less powerful, proxied for by higher board independence, higher

institutional ownership, and an indicator for newly appointed outside CEOs. This result also

indicates that other governance mechanisms can enhance subordinate executives’ ability to

influence the CEO’s decisions. Third, we find that the effect of internal governance is attenuated

for firms in financial distress, for firms that routinely meet or beat earnings targets, and for firms

with upcoming financing activities, presumably because subordinate executives have weaker

incentives to constrain real earnings management when the capital markets benefit of meeting or

beating earnings benchmarks is higher.

We also conduct a series of additional tests to ensure the robustness of our results and to

provide additional insights. First, the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act exerts a shock to firms’

governance (e.g., requiring higher board independence) and the extent of real earnings

management (Cohen, Dey, and Lys 2008). As such, we expect internal governance to be more

5 Our cross-sectional analyses also mitigate the endogeneity concern because it is arguably harder for an omitted

variable to explain both our main and cross-sectional findings.

7

effective in constraining the extent of real earnings management in the post-SOX period.

Consistent with our prediction, we find that our results are stronger in the post-SOX period than

in the pre-SOX period.

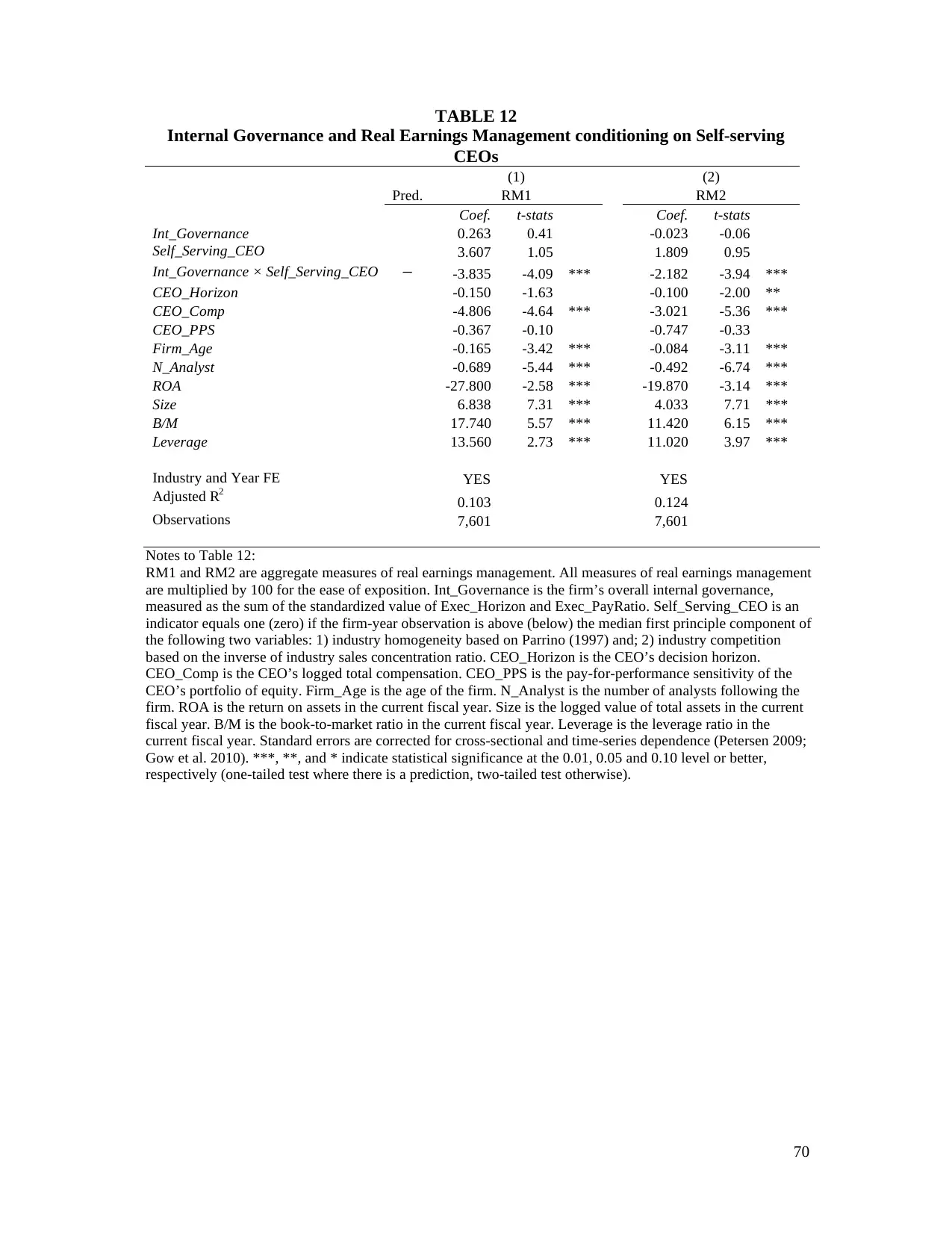

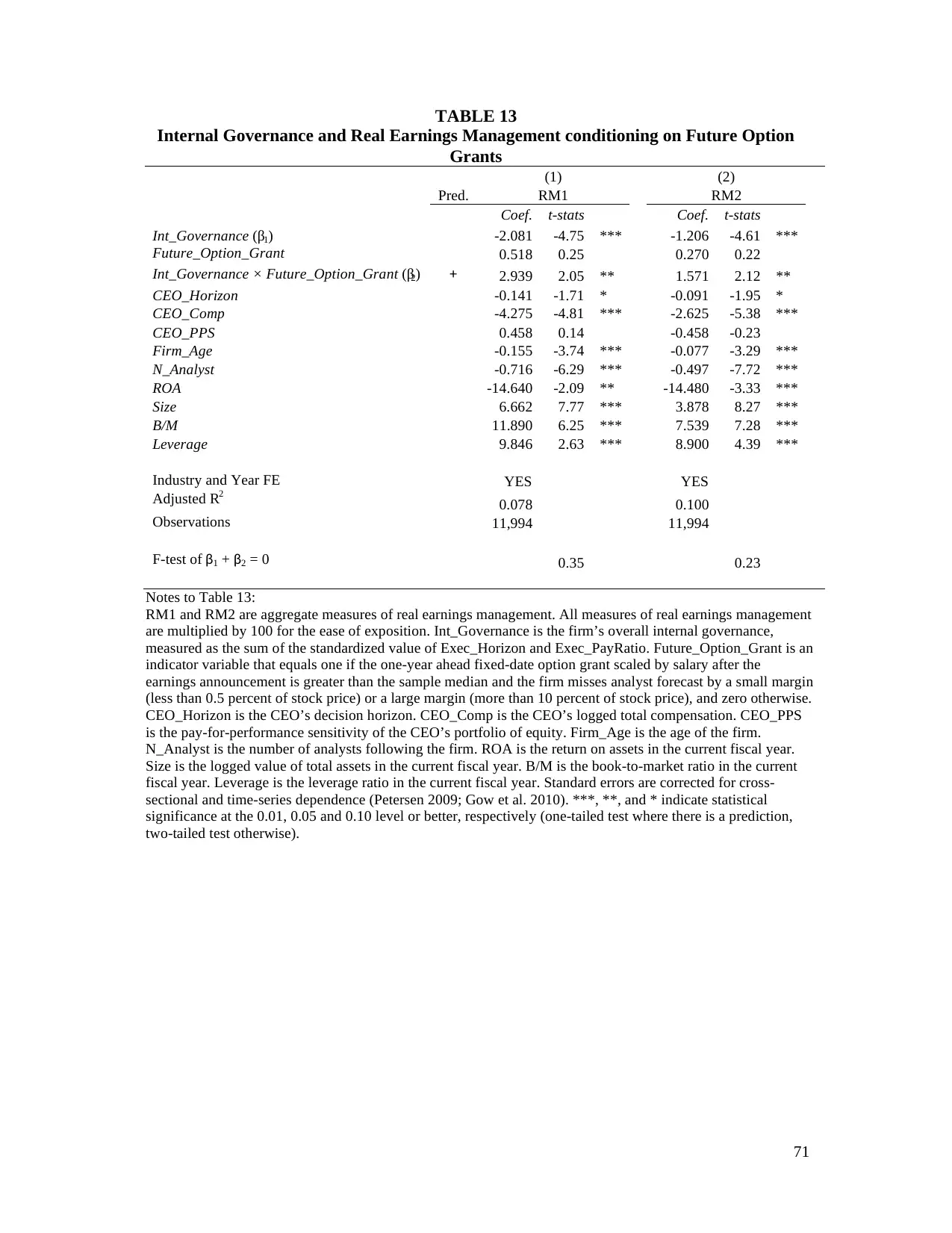

Second, we find that internal governance is more effective in constraining real earnings

management for firms in more homogeneous and competitive industries, where CEOs

presumably have greater career concerns and thus have stronger incentives to manage earnings to

report better financial performance (Parrino 1997; DeFond and Park 1999). Lastly, we find that

internal governance is less effective in constraining real earnings management for firms with

large forthcoming fixed-date option grants, where CEOs presumably have incentives to engage

in downward earnings management in order to reduce the exercise price of option grants (e.g.,

McAnally, Srivastava, and Weaver 2008).

This paper contributes to the literature in two important ways. First, this paper is the first to

examine the association between internal governance and the extent of real earnings

management. This examination is important as it sheds light on how the members of the

management team work together and shape financial reporting. This paper differs from and

complements studies on the impact of CFOs’ characteristics on accrual quality or the likelihood

of earnings restatements/frauds by focusing on all key subordinate executives and by focusing on

real earnings management.

Second, our examination of internal governance helps provide a more complete picture of

how firms work. Unlike prior research which generally views top executives as a unified team,

this paper provides evidence that key subordinate executives can serve an important monitoring

role and that effective internal governance can reduce the extent of CEOs’ myopic behavior. Our

study answers Fama’s (1980, 293) call for research on internal governance. He argues that while

effective in constraining the extent of real earnings management in the post-SOX period.

Consistent with our prediction, we find that our results are stronger in the post-SOX period than

in the pre-SOX period.

Second, we find that internal governance is more effective in constraining real earnings

management for firms in more homogeneous and competitive industries, where CEOs

presumably have greater career concerns and thus have stronger incentives to manage earnings to

report better financial performance (Parrino 1997; DeFond and Park 1999). Lastly, we find that

internal governance is less effective in constraining real earnings management for firms with

large forthcoming fixed-date option grants, where CEOs presumably have incentives to engage

in downward earnings management in order to reduce the exercise price of option grants (e.g.,

McAnally, Srivastava, and Weaver 2008).

This paper contributes to the literature in two important ways. First, this paper is the first to

examine the association between internal governance and the extent of real earnings

management. This examination is important as it sheds light on how the members of the

management team work together and shape financial reporting. This paper differs from and

complements studies on the impact of CFOs’ characteristics on accrual quality or the likelihood

of earnings restatements/frauds by focusing on all key subordinate executives and by focusing on

real earnings management.

Second, our examination of internal governance helps provide a more complete picture of

how firms work. Unlike prior research which generally views top executives as a unified team,

this paper provides evidence that key subordinate executives can serve an important monitoring

role and that effective internal governance can reduce the extent of CEOs’ myopic behavior. Our

study answers Fama’s (1980, 293) call for research on internal governance. He argues that while

8

each manager is concerned with the performance of others in the firm and as a consequence,

undertakes certain monitoring of other managers, both above or below, “less well appreciated,

however, is the monitoring that takes place from bottom to top.”

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section II provides a summary of prior

research and develops hypotheses. Section III describes the sample and data and presents the

research design. Section IV reports the main analysis of the impact of internal governance on the

extent of real earnings management, the analysis based on alternative proxies for internal

governance, and analyses addressing the potential endogeneity concerns. Section V reports the

cross-sectional analyses and Section VI additional analyses. Section VII concludes.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

Literature Review

We rely and build on two steams of the earnings management literature: the impact of

individual executives on financial reporting quality and real earnings management.

One of the fundamental drivers of earnings management is the pressure on managers to

deliver short-term performance that is used in contracting and firm valuation. See, for examples,

DeFond and Park (1997) on the pressure related to job security, Matsunaga and Park (2001) on

the pressure related to meeting earnings benchmarks, and Bartov, Givoly, and Hayn (2002) and

Kasznik and McNichols (2002) on the capital market pressure to deliver short-term performance.

A recent survey study, Dichev, Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal (2013), concludes that “about 20

percent of firms manage earnings to misrepresent economic performance, and for such firms 10

percent of EPS is typically managed.” Using a different research methodology, Dyck, Morse,

and Zingales (2013) also conclude that earnings management and accounting frauds are

each manager is concerned with the performance of others in the firm and as a consequence,

undertakes certain monitoring of other managers, both above or below, “less well appreciated,

however, is the monitoring that takes place from bottom to top.”

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section II provides a summary of prior

research and develops hypotheses. Section III describes the sample and data and presents the

research design. Section IV reports the main analysis of the impact of internal governance on the

extent of real earnings management, the analysis based on alternative proxies for internal

governance, and analyses addressing the potential endogeneity concerns. Section V reports the

cross-sectional analyses and Section VI additional analyses. Section VII concludes.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

Literature Review

We rely and build on two steams of the earnings management literature: the impact of

individual executives on financial reporting quality and real earnings management.

One of the fundamental drivers of earnings management is the pressure on managers to

deliver short-term performance that is used in contracting and firm valuation. See, for examples,

DeFond and Park (1997) on the pressure related to job security, Matsunaga and Park (2001) on

the pressure related to meeting earnings benchmarks, and Bartov, Givoly, and Hayn (2002) and

Kasznik and McNichols (2002) on the capital market pressure to deliver short-term performance.

A recent survey study, Dichev, Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal (2013), concludes that “about 20

percent of firms manage earnings to misrepresent economic performance, and for such firms 10

percent of EPS is typically managed.” Using a different research methodology, Dyck, Morse,

and Zingales (2013) also conclude that earnings management and accounting frauds are

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

9

prevalent. Given the vast literature on earnings management, we do not provide a detailed

literature review here and we refer readers to the review papers that discuss in greater detail the

demand for earnings management and how managers benefit from this activity (e.g., Schipper

1989; Healy and Wahlen 1999; Dechow and Skinner 2000; Fields, Lys, and Vincent 2001;

Dechow, Ge, and Schrand 2010).6

Most prior studies tend to focus on the management team as a whole or solely on the CEO

as the person(s) held primarily responsible for earnings management within the firm. Recently,

the literature starts to examine the effect of CFOs on earnings quality. For example, Geiger and

North (2006) find that the appointment of new CFOs is associated with a decrease in

discretionary accruals and that the result is largely driven by new CFOs who are hired from

outside. Focusing on CFO directors, Bedard, Hoitash, and Hoitash (2014) find that firms with

CFOs who sit on their own board exhibit higher reporting quality (e.g., lower likelihood of

internal control weaknesses, lower likelihood of restatements, and higher accruals quality). Ge,

Matsumoto, and Zhang (2011) find that CFOs matter for various accounting choices, such as

discretionary accruals, the likelihood of meeting or just beating earnings expectations, and the

likelihood of restatements.7

There are also studies contrasting the impact of CFOs’ incentives with that of CEOs’ on

earnings management. Jiang et al. (2010) find that the magnitude of accruals and the likelihood

of meeting or just beating analysts’ forecast are more sensitive to CFOs’ than to CEOs’ equity

incentives in the pre-SOX period. In contrast, Feng et al. (2011) find that while CEOs of firms

6 While the literature focusses primarily on accrual-based earnings management, the argument on the demand for

and the benefit (to managers) of earnings management apply to real earnings management as well. Indeed, the recent

development of the real earnings management literature builds on prior studies of accrual-based earnings

management.

7 Ge et al. (2011) capture the effect of CFO style by using a fixed effect model to track CFOs who work in multiple

companies over their sample period.

prevalent. Given the vast literature on earnings management, we do not provide a detailed

literature review here and we refer readers to the review papers that discuss in greater detail the

demand for earnings management and how managers benefit from this activity (e.g., Schipper

1989; Healy and Wahlen 1999; Dechow and Skinner 2000; Fields, Lys, and Vincent 2001;

Dechow, Ge, and Schrand 2010).6

Most prior studies tend to focus on the management team as a whole or solely on the CEO

as the person(s) held primarily responsible for earnings management within the firm. Recently,

the literature starts to examine the effect of CFOs on earnings quality. For example, Geiger and

North (2006) find that the appointment of new CFOs is associated with a decrease in

discretionary accruals and that the result is largely driven by new CFOs who are hired from

outside. Focusing on CFO directors, Bedard, Hoitash, and Hoitash (2014) find that firms with

CFOs who sit on their own board exhibit higher reporting quality (e.g., lower likelihood of

internal control weaknesses, lower likelihood of restatements, and higher accruals quality). Ge,

Matsumoto, and Zhang (2011) find that CFOs matter for various accounting choices, such as

discretionary accruals, the likelihood of meeting or just beating earnings expectations, and the

likelihood of restatements.7

There are also studies contrasting the impact of CFOs’ incentives with that of CEOs’ on

earnings management. Jiang et al. (2010) find that the magnitude of accruals and the likelihood

of meeting or just beating analysts’ forecast are more sensitive to CFOs’ than to CEOs’ equity

incentives in the pre-SOX period. In contrast, Feng et al. (2011) find that while CEOs of firms

6 While the literature focusses primarily on accrual-based earnings management, the argument on the demand for

and the benefit (to managers) of earnings management apply to real earnings management as well. Indeed, the recent

development of the real earnings management literature builds on prior studies of accrual-based earnings

management.

7 Ge et al. (2011) capture the effect of CFO style by using a fixed effect model to track CFOs who work in multiple

companies over their sample period.

10

that are involved in material accounting manipulations (manipulations that violate GAAP) have

higher equity incentives than their counterparts in other firms, CFOs of these accounting

manipulation firms have similar levels of equity incentives as their counterparts in other firms.

Despite their lack of incentives, CFOs who are involved in material accounting manipulations

suffer substantial losses. Feng et al. conclude that the direct financial gain is not the main

motivation for CFOs to be involved in earnings manipulation. Rather, CFOs likely succumb to

powerful CEOs’ pressure to manipulate financial statements.

We extend this line of research by focusing on a broader set of key subordinate executives,

including not only CFOs but also other top executives, and examine their impact on the extent of

real earnings management. We focus on real earnings management for two reasons. 8 First, the

tradeoff between increasing short-term performance and increasing long-term firm value is

important for real earnings management. For example, cutting R&D expenditures now to meet

current year’s earnings targets will lead to lower long-term investment and likely reduce the

company’s ability to compete in the product markets and to generate profits in the future.

Consistent with this notion, Bhojraj et al. (2009), Leggett, Parsons, and Reitenga (2009), and

Mizik (2010) report that firms that reduce discretionary spending to beat earnings benchmark

exhibit long-term underperformance. Cohen and Zarowin (2010) and Mizik and Jacobson (2008)

document that firms engaging in real earnings management prior to seasoned equity offerings

have poorer operating performance in the future. Graham et al. (2005) also provide supporting

8 In an untabulated analysis, we examine the impact of internal governance on accrual earnings management. Ex-

ante, whether non-CFO subordinate executives can influence the extent of accrual earnings management is unclear.

On one hand, key subordinate executives do not play a direct role in accrual management because unlike the CFO,

they are not directly involved in the financial reporting process. On the other hand, they likely have an important

influence over the corporate culture and the overall corporate attitude toward earnings management. If the key

subordinate executives focus on the long-term value of the firm, their preference might manifest in less accrual-

based earnings management. After considering the interrelationship between real and accrual earnings management,

we do not find robust evidence that subordinate executives have a significant impact on the extent of accrual

earnings management, consistent with these executives playing a more limited role in the financial reporting

process.

that are involved in material accounting manipulations (manipulations that violate GAAP) have

higher equity incentives than their counterparts in other firms, CFOs of these accounting

manipulation firms have similar levels of equity incentives as their counterparts in other firms.

Despite their lack of incentives, CFOs who are involved in material accounting manipulations

suffer substantial losses. Feng et al. conclude that the direct financial gain is not the main

motivation for CFOs to be involved in earnings manipulation. Rather, CFOs likely succumb to

powerful CEOs’ pressure to manipulate financial statements.

We extend this line of research by focusing on a broader set of key subordinate executives,

including not only CFOs but also other top executives, and examine their impact on the extent of

real earnings management. We focus on real earnings management for two reasons. 8 First, the

tradeoff between increasing short-term performance and increasing long-term firm value is

important for real earnings management. For example, cutting R&D expenditures now to meet

current year’s earnings targets will lead to lower long-term investment and likely reduce the

company’s ability to compete in the product markets and to generate profits in the future.

Consistent with this notion, Bhojraj et al. (2009), Leggett, Parsons, and Reitenga (2009), and

Mizik (2010) report that firms that reduce discretionary spending to beat earnings benchmark

exhibit long-term underperformance. Cohen and Zarowin (2010) and Mizik and Jacobson (2008)

document that firms engaging in real earnings management prior to seasoned equity offerings

have poorer operating performance in the future. Graham et al. (2005) also provide supporting

8 In an untabulated analysis, we examine the impact of internal governance on accrual earnings management. Ex-

ante, whether non-CFO subordinate executives can influence the extent of accrual earnings management is unclear.

On one hand, key subordinate executives do not play a direct role in accrual management because unlike the CFO,

they are not directly involved in the financial reporting process. On the other hand, they likely have an important

influence over the corporate culture and the overall corporate attitude toward earnings management. If the key

subordinate executives focus on the long-term value of the firm, their preference might manifest in less accrual-

based earnings management. After considering the interrelationship between real and accrual earnings management,

we do not find robust evidence that subordinate executives have a significant impact on the extent of accrual

earnings management, consistent with these executives playing a more limited role in the financial reporting

process.

11

evidence based on their surveys of CFOs.9 Second and importantly, key subordinate executives

have more direct control and influence over real activities, such as R&D expenditures,

production volumes, and sales decisions, than over accrual-based earnings management.

To our knowledge, ours is the first study that explicitly examines the impact of subordinate

executives on the extent of real earnings management. The extant literature on real earnings

management has focused primarily on documenting the existence of real earnings management.

For example, Graham et al. (2005) report that 80 percent of surveyed CFOs stated that, in order

to deliver earnings, they would decrease research and development (R&D), advertising, and

maintenance expenditures, while 55 percent said they would postpone a new project, both of

which are real activities manipulation. Roychowdhury (2006) documents the existence of real

earnings management in firms that meet or just beat earnings benchmarks. Cohen et al. (2008)

find that the extent of real earnings management is higher in the post-SOX period than in the pre-

SOX period. We extend this line of research by examining how internal governance affects the

extent of real earnings management, complementing studies that examine the impact on real

earnings management of other governance mechanisms, such as institutional ownership, board

independence, and employment agreement (e.g., Bushee 1998; Carcello, Hollingsworth, Klein,

and Neal 2006; Zhao 2011; Chen, Cheng, Lo, and Wang 2015).

Hypothesis Development

Main Hypothesis

In this section, we discuss why key subordinate executives have both the incentive and

9 In contrast, Gunny (2010) finds that firms engaging in real earnings management to report small positive earnings

exhibit better subsequent performance and she attributes this result to the signaling role of real earnings

management. In light of this contradictory evidence, in an untabulated analysis we examine the association between

our real earnings management proxies and future performance in our sample. Unlike Gunny (2010), we find that our

measures of real earnings management are associated with significantly lower one-year-ahead returns on assets and

cash flow from operations.

evidence based on their surveys of CFOs.9 Second and importantly, key subordinate executives

have more direct control and influence over real activities, such as R&D expenditures,

production volumes, and sales decisions, than over accrual-based earnings management.

To our knowledge, ours is the first study that explicitly examines the impact of subordinate

executives on the extent of real earnings management. The extant literature on real earnings

management has focused primarily on documenting the existence of real earnings management.

For example, Graham et al. (2005) report that 80 percent of surveyed CFOs stated that, in order

to deliver earnings, they would decrease research and development (R&D), advertising, and

maintenance expenditures, while 55 percent said they would postpone a new project, both of

which are real activities manipulation. Roychowdhury (2006) documents the existence of real

earnings management in firms that meet or just beat earnings benchmarks. Cohen et al. (2008)

find that the extent of real earnings management is higher in the post-SOX period than in the pre-

SOX period. We extend this line of research by examining how internal governance affects the

extent of real earnings management, complementing studies that examine the impact on real

earnings management of other governance mechanisms, such as institutional ownership, board

independence, and employment agreement (e.g., Bushee 1998; Carcello, Hollingsworth, Klein,

and Neal 2006; Zhao 2011; Chen, Cheng, Lo, and Wang 2015).

Hypothesis Development

Main Hypothesis

In this section, we discuss why key subordinate executives have both the incentive and

9 In contrast, Gunny (2010) finds that firms engaging in real earnings management to report small positive earnings

exhibit better subsequent performance and she attributes this result to the signaling role of real earnings

management. In light of this contradictory evidence, in an untabulated analysis we examine the association between

our real earnings management proxies and future performance in our sample. Unlike Gunny (2010), we find that our

measures of real earnings management are associated with significantly lower one-year-ahead returns on assets and

cash flow from operations.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

12

ability to provide monitoring and reduce the extent of real earnings management.

As discussed above, one of the fundamental drivers of earnings management is the pressure

on CEOs to deliver short-term performance. While it is possible that key subordinate executives

are under similar or even greater pressure to deliver short-term performance, yet as compared to

CEOs, key subordinate executives have longer horizons that induce them to care more about

long-term firm value for three reasons. First, one of the career objectives of many key

subordinate executives is to become the next CEO when the current CEO retires or resigns. As

documented in Cremers and Grinstein (2011), 68.6 percent of CEOs are promoted within the

firm; in other words, in 68.6 percent of the CEO turnover cases, one of the key subordinate

executives becomes the next CEO.10 As the potential CEO in the future, these subordinate

executives care about the cash flows that the firm can generate in the future. Since a company’s

performance depends critically on the capital stock (i.e., value enhancing assets), how the

company performs when the subordinate manager becomes the CEO depends on current

investment. Thus, subordinate executives are hypothesized to care more about long-term

investment and therefore less likely to support activities that sacrifice long-term positive NPV

investments to meet short-term earnings targets.

Second, subordinate executives have more to lose in the event of corporate

underperformance and operational failures. Key subordinate executives are usually younger than

the CEO. In our sample, they are three years younger at the sample median, and this difference

represents a 30 percent increase in the number of years of remaining employment (i.e., the

number of years until the assumed retirement age of 65). Their future compensation likely

10 Based on data from ExecuComp, we find that 59.7 percent of the CEOs in our sample were promoted within the

company. Within this group of CEOs, 36.0 percent were the Chief Operating Officer, 40.8 percent were the

President, and 7.5 percent were the Vice President. These statistics confirm that inside-CEOs are generally selected

from the set of key subordinate executives we study.

ability to provide monitoring and reduce the extent of real earnings management.

As discussed above, one of the fundamental drivers of earnings management is the pressure

on CEOs to deliver short-term performance. While it is possible that key subordinate executives

are under similar or even greater pressure to deliver short-term performance, yet as compared to

CEOs, key subordinate executives have longer horizons that induce them to care more about

long-term firm value for three reasons. First, one of the career objectives of many key

subordinate executives is to become the next CEO when the current CEO retires or resigns. As

documented in Cremers and Grinstein (2011), 68.6 percent of CEOs are promoted within the

firm; in other words, in 68.6 percent of the CEO turnover cases, one of the key subordinate

executives becomes the next CEO.10 As the potential CEO in the future, these subordinate

executives care about the cash flows that the firm can generate in the future. Since a company’s

performance depends critically on the capital stock (i.e., value enhancing assets), how the

company performs when the subordinate manager becomes the CEO depends on current

investment. Thus, subordinate executives are hypothesized to care more about long-term

investment and therefore less likely to support activities that sacrifice long-term positive NPV

investments to meet short-term earnings targets.

Second, subordinate executives have more to lose in the event of corporate

underperformance and operational failures. Key subordinate executives are usually younger than

the CEO. In our sample, they are three years younger at the sample median, and this difference

represents a 30 percent increase in the number of years of remaining employment (i.e., the

number of years until the assumed retirement age of 65). Their future compensation likely

10 Based on data from ExecuComp, we find that 59.7 percent of the CEOs in our sample were promoted within the

company. Within this group of CEOs, 36.0 percent were the Chief Operating Officer, 40.8 percent were the

President, and 7.5 percent were the Vice President. These statistics confirm that inside-CEOs are generally selected

from the set of key subordinate executives we study.

13

represents a larger proportion of their overall income and wealth. While the CEO might also

suffer from poor firm performance, the concept of diminishing marginal utility suggests that the

relative impact, i.e., the impact of the potential loss related to the individual’s total wealth, is

important. As such, lower compensation due to poor firm performance in the future or loss of

income due to the difficulty of finding a comparable job is higher for younger executives and

increases with their horizon. This is the same idea underlying the horizon problem discussed in

Dechow and Sloan (1991).

Third, Fama (1980) argues that in general, a manager’s outside opportunity wage depends

on other managers’, including the CEO’s, actions and firm performance. This effect can motivate

the key subordinate executives to be more long-term oriented and to exert monitoring on the

CEO.

The above discussion implies that subordinate executives have longer horizons than the

CEO. The longer the subordinate executives’ horizon, the stronger their incentives not to

sacrifice long-term value for short-term goals.

Not only do subordinate executives have incentives, they also have the means to influence

the CEO’s decision. The current CEO’s welfare depends on the cash flow in the current period,

which is affected by the key subordinate executives’ effort levels.11 If the CEO does not consider

the subordinate executives’ interests, subordinate executives can work less diligently, hence

reducing the current cash flow and the CEO’s welfare (Allen and Gale 2000; Acharya et al.

2011).12 Anticipating this, it is in the best interest of the CEO to consider subordinate executives’

11 The importance of these key subordinate executives is self-evident. In a recent study, Graham, Harvey, and Puri

(2013) find that only about 15 percent of the surveyed CEOs and CFOs indicate that the CEO is the sole-decision

maker in their firms regarding important corporate decisions, such as M&A, capital allocation and investments.

12 This argument is plausible because an individual’s effort level is usually unobservable and subordinate executives

have the best information to decide the appropriate effort level. (This is the same reason why top executives are

given performance-based bonus and stock-based compensation, not just a fixed salary).

represents a larger proportion of their overall income and wealth. While the CEO might also

suffer from poor firm performance, the concept of diminishing marginal utility suggests that the

relative impact, i.e., the impact of the potential loss related to the individual’s total wealth, is

important. As such, lower compensation due to poor firm performance in the future or loss of

income due to the difficulty of finding a comparable job is higher for younger executives and

increases with their horizon. This is the same idea underlying the horizon problem discussed in

Dechow and Sloan (1991).

Third, Fama (1980) argues that in general, a manager’s outside opportunity wage depends

on other managers’, including the CEO’s, actions and firm performance. This effect can motivate

the key subordinate executives to be more long-term oriented and to exert monitoring on the

CEO.

The above discussion implies that subordinate executives have longer horizons than the

CEO. The longer the subordinate executives’ horizon, the stronger their incentives not to

sacrifice long-term value for short-term goals.

Not only do subordinate executives have incentives, they also have the means to influence

the CEO’s decision. The current CEO’s welfare depends on the cash flow in the current period,

which is affected by the key subordinate executives’ effort levels.11 If the CEO does not consider

the subordinate executives’ interests, subordinate executives can work less diligently, hence

reducing the current cash flow and the CEO’s welfare (Allen and Gale 2000; Acharya et al.

2011).12 Anticipating this, it is in the best interest of the CEO to consider subordinate executives’

11 The importance of these key subordinate executives is self-evident. In a recent study, Graham, Harvey, and Puri

(2013) find that only about 15 percent of the surveyed CEOs and CFOs indicate that the CEO is the sole-decision

maker in their firms regarding important corporate decisions, such as M&A, capital allocation and investments.

12 This argument is plausible because an individual’s effort level is usually unobservable and subordinate executives

have the best information to decide the appropriate effort level. (This is the same reason why top executives are

given performance-based bonus and stock-based compensation, not just a fixed salary).

14

interests, motivating subordinate executives to work harder (Landier, Sraer, and Thesmar 2009).

Applying the above general discussion to the real earnings management setting, if the CEO

chooses real activity manipulation that decreases long-term firm value, key subordinate

executives will choose a lower effort level. Anticipating this, the CEO will be less likely to

engage in real earnings management. In other words, if the CEO does not engage in real earnings

management, then the subordinate executives’ interest is aligned and they will work harder to

improve both current and future firm performance.

In addition, the CEO needs the subordinate executives’ cooperation to engage in real

earnings management because subordinate executives are usually more informed than the CEO

in their own functional areas. For example, the president in charge of production likely has more

information about the supply of raw materials and the demand from customers. Hence, he or she

will play an important role if the firm decides to overproduce in order to increase the current

period’s earnings. Similarly, the executive in charge of R&D is better informed and can

influence whether and how much the firm can reduce the current period’s R&D. That is, while

the CEO has the formal authority to make the decision, subordinate executives have the real

authority, e.g., effective control over the decisions, due to their information advantage (Aghion

and Tirole 1997). As such, the CEO will have to take the subordinate executives’ preferences

into consideration.

Overall, the effectiveness of key subordinate executives’ influence in curbing myopic

behavior depends on their horizon and their ability to influence CEOs’ decisions. The longer the

horizon and the more influence the key subordinate executives have, the more effective the

internal governance, and the less likely that the company will engage in real earnings

management. Thus, our first hypothesis (in alternative form) is as follows:

interests, motivating subordinate executives to work harder (Landier, Sraer, and Thesmar 2009).

Applying the above general discussion to the real earnings management setting, if the CEO

chooses real activity manipulation that decreases long-term firm value, key subordinate

executives will choose a lower effort level. Anticipating this, the CEO will be less likely to

engage in real earnings management. In other words, if the CEO does not engage in real earnings

management, then the subordinate executives’ interest is aligned and they will work harder to

improve both current and future firm performance.

In addition, the CEO needs the subordinate executives’ cooperation to engage in real

earnings management because subordinate executives are usually more informed than the CEO

in their own functional areas. For example, the president in charge of production likely has more

information about the supply of raw materials and the demand from customers. Hence, he or she

will play an important role if the firm decides to overproduce in order to increase the current

period’s earnings. Similarly, the executive in charge of R&D is better informed and can

influence whether and how much the firm can reduce the current period’s R&D. That is, while

the CEO has the formal authority to make the decision, subordinate executives have the real

authority, e.g., effective control over the decisions, due to their information advantage (Aghion

and Tirole 1997). As such, the CEO will have to take the subordinate executives’ preferences

into consideration.

Overall, the effectiveness of key subordinate executives’ influence in curbing myopic

behavior depends on their horizon and their ability to influence CEOs’ decisions. The longer the

horizon and the more influence the key subordinate executives have, the more effective the

internal governance, and the less likely that the company will engage in real earnings

management. Thus, our first hypothesis (in alternative form) is as follows:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

15

H1: The extent of upward real earnings management is negatively associated with the

effectiveness of internal governance.

As discussed below, we use key subordinate executives’ horizon (i.e., the number of years until

retirement) and their relative pay (i.e., the average pay of subordinate executives divided by CEO

pay) to capture the effectiveness of internal governance.

There are two critical assumptions underlying H1. First, we rely on prior research to argue

that the CEO has incentives to increase short-term performance at the expense of long-term

value, such as to increase job security (DeFond and Park 1997) and to increase compensation

(e.g., Healy 1985; Cheng and Warfield 2005). One might argue that subordinate executives

might be as myopic as the CEO. In addition, it is possible that the key subordinate executives are

in a tournament or competition for the CEO’s position with external candidates. As a result, they

might undertake real earnings management to increase short-term earnings and/or to curry favor

with the CEO who likely plays a role in selecting his/her successor. If this is the case, we will not

find results consistent with H1. Second, while prior research indicates that key subordinate

executives have the ability to influence CEOs’ decisions, CEOs have the power to demote or fire

these subordinate executives. Job security concerns can motivate subordinates to cooperate with

CEOs in carrying out myopic behavior (Feng et al. 2011). Of course, firing key subordinate

executives because they do not cooperate in myopic behavior can backfire. Having nothing to

lose after being fired, subordinate executives can become “whistle-blowers” and reveal the

inappropriate behavior to the board, investors, and the press, or seek legal action against the firm

for inappropriate dismissal. This potential outcome will deter CEOs from freely firing

subordinate executives who choose not to engage in myopic behavior. Again, if subordinate

executives have no influence on CEOs’ myopic behavior or if CEOs have no incentive to engage

in earnings management, we will not find results consistent with H1. Thus, whether we find

H1: The extent of upward real earnings management is negatively associated with the

effectiveness of internal governance.

As discussed below, we use key subordinate executives’ horizon (i.e., the number of years until

retirement) and their relative pay (i.e., the average pay of subordinate executives divided by CEO

pay) to capture the effectiveness of internal governance.

There are two critical assumptions underlying H1. First, we rely on prior research to argue

that the CEO has incentives to increase short-term performance at the expense of long-term

value, such as to increase job security (DeFond and Park 1997) and to increase compensation

(e.g., Healy 1985; Cheng and Warfield 2005). One might argue that subordinate executives

might be as myopic as the CEO. In addition, it is possible that the key subordinate executives are

in a tournament or competition for the CEO’s position with external candidates. As a result, they

might undertake real earnings management to increase short-term earnings and/or to curry favor

with the CEO who likely plays a role in selecting his/her successor. If this is the case, we will not

find results consistent with H1. Second, while prior research indicates that key subordinate

executives have the ability to influence CEOs’ decisions, CEOs have the power to demote or fire

these subordinate executives. Job security concerns can motivate subordinates to cooperate with

CEOs in carrying out myopic behavior (Feng et al. 2011). Of course, firing key subordinate

executives because they do not cooperate in myopic behavior can backfire. Having nothing to

lose after being fired, subordinate executives can become “whistle-blowers” and reveal the

inappropriate behavior to the board, investors, and the press, or seek legal action against the firm

for inappropriate dismissal. This potential outcome will deter CEOs from freely firing

subordinate executives who choose not to engage in myopic behavior. Again, if subordinate

executives have no influence on CEOs’ myopic behavior or if CEOs have no incentive to engage

in earnings management, we will not find results consistent with H1. Thus, whether we find

16

results consistent with H1 is an empirical question.

Cross-sectional Analyses

To corroborate our theory and main hypothesis that key subordinate executives have the

ability and incentive to influence the extent of real earnings management, we propose several

cross-sectional predictions that exploit the variation in subordinate executives’ ability and

incentive. These cross-sectional tests also help rule out competing explanations for the main

result.

Variation in subordinate executives’ contribution

One key assumption underlying H1 is that subordinate executives can influence corporate