Snack food advertising in stores around public schools in Guatemala

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/30

|9

|5091

|117

AI Summary

This study describes the type of snack foods advertised to children in stores in and around public schools and assesses if there is an association between child-oriented snack food advertising and proximity to schools. The food industry is flooding the market, taking advantage of the lack of strict regulation in Guatemala. Child-oriented advertisements are available in almost all stores within a short walking distance from schools, exposing children to an obesogenic environment.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Snack food advertising in stores around public schools in

Guatemala

Violeta Chacona, Paola Letonaa, Eduardo Villamorb, and Joaquin Barnoyaa,c,*

aDepartment of Research, Cardiovascular Surgery Unit of Guatemala, Guatemala City,

Guatemala.

bDepartment of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor,

Michigan, USA.

cDivision of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis,

School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Abstract

Obesity in school-age children is emerging as a public heath concern. Food marketing influences

preferences and increases children's requests for food. This study sought to describe the type of

snack foods advertised to children in stores in and around public schools and assess if there is an

association between child-oriented snack food advertising and proximity to schools. All food

stores located inside and within a 200 square meter radius from two preschools and two primary

schools were surveyed. We assessed store type, number and type of snack food advertisements

including those child-oriented inside and outside stores. We surveyed 55 stores and found 321

snack food advertisements. Most were on sweetened beverages (37%) and soft drinks (30%).

Ninety-two (29%) were child-oriented. Atoles (100.0%), cereals (94.1%), and ice cream and

frozen desserts (71.4%) had the greatest proportion of child-oriented advertising. We found more

child-oriented advertisements in stores that were closer (<170 m) to schools compared to those

farther away. In conclusion, the food industry is flooding the market, taking advantage of the lack

of strict regulation in Guatemala. Child-oriented advertisements are available in almost all stores

within a short walking distance from schools, exposing children to an obesogenic environment.

Keywords

children; marketing; food industry

Introduction

Childhood obesity is emerging as a public health concern in Latin America (Rivera et al.

2013). Guatemala is experiencing the double burden of disease that combines a high

prevalence of childhood stunting (54.5%) (World Health Organization 2008) with a rising

childhood overweight prevalence (27.1%) (World Health Organization 2009). Overweight

results from a combination of genetics, psychosocial variables and environmental factors

*Corresponding author. barnoyaj@wudosis.wustl.edu Postal address: 9a avenida 8-00 zona 11, Guatemala City, Guatemala..

HHS Public Access

Author manuscript

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Published in final edited form as:

Crit Public Health. 2015 ; 25(3): 291–298. doi:10.1080/09581596.2014.953035.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Guatemala

Violeta Chacona, Paola Letonaa, Eduardo Villamorb, and Joaquin Barnoyaa,c,*

aDepartment of Research, Cardiovascular Surgery Unit of Guatemala, Guatemala City,

Guatemala.

bDepartment of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor,

Michigan, USA.

cDivision of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis,

School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Abstract

Obesity in school-age children is emerging as a public heath concern. Food marketing influences

preferences and increases children's requests for food. This study sought to describe the type of

snack foods advertised to children in stores in and around public schools and assess if there is an

association between child-oriented snack food advertising and proximity to schools. All food

stores located inside and within a 200 square meter radius from two preschools and two primary

schools were surveyed. We assessed store type, number and type of snack food advertisements

including those child-oriented inside and outside stores. We surveyed 55 stores and found 321

snack food advertisements. Most were on sweetened beverages (37%) and soft drinks (30%).

Ninety-two (29%) were child-oriented. Atoles (100.0%), cereals (94.1%), and ice cream and

frozen desserts (71.4%) had the greatest proportion of child-oriented advertising. We found more

child-oriented advertisements in stores that were closer (<170 m) to schools compared to those

farther away. In conclusion, the food industry is flooding the market, taking advantage of the lack

of strict regulation in Guatemala. Child-oriented advertisements are available in almost all stores

within a short walking distance from schools, exposing children to an obesogenic environment.

Keywords

children; marketing; food industry

Introduction

Childhood obesity is emerging as a public health concern in Latin America (Rivera et al.

2013). Guatemala is experiencing the double burden of disease that combines a high

prevalence of childhood stunting (54.5%) (World Health Organization 2008) with a rising

childhood overweight prevalence (27.1%) (World Health Organization 2009). Overweight

results from a combination of genetics, psychosocial variables and environmental factors

*Corresponding author. barnoyaj@wudosis.wustl.edu Postal address: 9a avenida 8-00 zona 11, Guatemala City, Guatemala..

HHS Public Access

Author manuscript

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Published in final edited form as:

Crit Public Health. 2015 ; 25(3): 291–298. doi:10.1080/09581596.2014.953035.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

that affect diet and physical activity (Bouchard 2007; Schwartz and Puhl 2003). Among the

environmental factors, food marketing is key to promote childhood weight gain (Harris et al.

2009).

Child-oriented food marketing influences brand preferences and increases children's requests

for food (Hastings G et al. 2005; Letona et al. 2014). Overweight and obese children have

higher recognition of food advertisements and therefore food consumption, compared to

their non-counterparts (Halford et al. 2004). A direct correlation between television

advertising exposure and childhood obesity has also been documented (Robinson 1999;

Gortmaker et al. 1999). Similarly, food displays and advertisements in school kiosks are

strongly associated with purchase by primary and secondary school children (Mazur et al.

2008). Furthermore, consumer segmentation, a marketing strategy that involves dividing the

market into different groups with similar characteristics (e.g., age) has proven a useful tool

for the food industry to increase sales (McGinnis, Appleton, and Kraak 2006). In addition,

trade liberalization policies promoting worldwide expansion of unhealthy food industry may

also contribute to obesity (De Vogli, Kouvonen, and Gimeno 2011).

In 2007, the United Kingdom was the first country to restrict television child-oriented

advertising of high fat foods on all children's and non-children's channels before 9:00 PM

(Ofcom 2007). Quebec, Norway and Sweden have also implemented bans on television food

advertising and in-school marketing oriented to children (World Health Organization 2007).

Although not yet conclusive (Adams et al. 2012), a combination of interventions, in addition

to restricting television advertising, holds the most promise to decrease children's

advertising exposure (Bogart 2013; McGinnis, Appleton, and Kraak 2006). Examples

include regulation of all marketing types of unhealthy foods and implementation of nutrition

standards for foods and beverages sold in school kiosks (McGinnis, Appleton, and Kraak

2006).

In Guatemala, packaged foods nutrition labeling is regulated by the Food Control and

Regulation Department of the Ministry of Health. According to the Department, nutrition

health claims should be consistent with the nutrition information on the label (Consejo de

Ministros de Integración Económica 2012). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is

no enforcement and no regulation of child-oriented food advertising (Hawkes and Lobstein

2011). Furthermore, the types and quantity of snack foods advertised to children at the point

of sale have not been documented. Moreover, the association between child-oriented snack

food advertising and proximity to schools is yet unknown. Therefore, this study sought to

describe the type of snack foods advertised to children in stores in and around public schools

and assess if there was an association between child-oriented snack food advertising and

proximity to schools.

Methods

Out of 95 public schools, two preschools and two primary schools (students between 4 to 12

years old) located in the Municipality of Mixco were conveniently selected for this study.

Mixco is a city with 483,705 inhabitants (Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Guatemala

2012) in the Department of Guatemala. Since public schools in Mixco have similar

Chacon et al. Page 2

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

environmental factors, food marketing is key to promote childhood weight gain (Harris et al.

2009).

Child-oriented food marketing influences brand preferences and increases children's requests

for food (Hastings G et al. 2005; Letona et al. 2014). Overweight and obese children have

higher recognition of food advertisements and therefore food consumption, compared to

their non-counterparts (Halford et al. 2004). A direct correlation between television

advertising exposure and childhood obesity has also been documented (Robinson 1999;

Gortmaker et al. 1999). Similarly, food displays and advertisements in school kiosks are

strongly associated with purchase by primary and secondary school children (Mazur et al.

2008). Furthermore, consumer segmentation, a marketing strategy that involves dividing the

market into different groups with similar characteristics (e.g., age) has proven a useful tool

for the food industry to increase sales (McGinnis, Appleton, and Kraak 2006). In addition,

trade liberalization policies promoting worldwide expansion of unhealthy food industry may

also contribute to obesity (De Vogli, Kouvonen, and Gimeno 2011).

In 2007, the United Kingdom was the first country to restrict television child-oriented

advertising of high fat foods on all children's and non-children's channels before 9:00 PM

(Ofcom 2007). Quebec, Norway and Sweden have also implemented bans on television food

advertising and in-school marketing oriented to children (World Health Organization 2007).

Although not yet conclusive (Adams et al. 2012), a combination of interventions, in addition

to restricting television advertising, holds the most promise to decrease children's

advertising exposure (Bogart 2013; McGinnis, Appleton, and Kraak 2006). Examples

include regulation of all marketing types of unhealthy foods and implementation of nutrition

standards for foods and beverages sold in school kiosks (McGinnis, Appleton, and Kraak

2006).

In Guatemala, packaged foods nutrition labeling is regulated by the Food Control and

Regulation Department of the Ministry of Health. According to the Department, nutrition

health claims should be consistent with the nutrition information on the label (Consejo de

Ministros de Integración Económica 2012). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is

no enforcement and no regulation of child-oriented food advertising (Hawkes and Lobstein

2011). Furthermore, the types and quantity of snack foods advertised to children at the point

of sale have not been documented. Moreover, the association between child-oriented snack

food advertising and proximity to schools is yet unknown. Therefore, this study sought to

describe the type of snack foods advertised to children in stores in and around public schools

and assess if there was an association between child-oriented snack food advertising and

proximity to schools.

Methods

Out of 95 public schools, two preschools and two primary schools (students between 4 to 12

years old) located in the Municipality of Mixco were conveniently selected for this study.

Mixco is a city with 483,705 inhabitants (Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Guatemala

2012) in the Department of Guatemala. Since public schools in Mixco have similar

Chacon et al. Page 2

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

characteristics, selected schools were not likely to be atypical (Ministerio de Educación

2012). Most children enrolled in public schools are from low socioeconomic status (World

Bank 2009) and enrollment in primary education is 95.8% (60% completion) (Guatemala

Human Rights Commission 2010). We obtained permission from the School District

Supervisor and each school principal to survey kiosks inside the schools for food

advertising.

All food kiosks located inside schools were surveyed. Using Google™ Earth, we identified

all stores located in a 200 meters radius centered on each school's entrance and surveyed the

distance in meters between the school entrance and each store. We arbitrarily categorized

the distance between the school entrance and stores as less than 170 meters and equal or

more than 170 meters as we considered this a reasonable distance for children between 4 to

12 years of age to walk to and from school.

We adapted the tobacco point of sale advertisement checklist by Cohen et al (Cohen et al.

2008), and adapted by Barnoya et al (Barnoya et al. 2010) to assess the store type (i.e., small

store, large store, school kiosk, street vendor, pharmacy, service station), total number of

snack food advertisements and those child-oriented inside and outside stores. We also

assessed the number of stores with snack foods displayed at the counter or snack foods less

than 50 cm from tobacco products, and in-store marketing techniques (display racks,

refrigerators, containers, and shelves). The checklist was pilot tested in seven stores located

in Mixco and found to be appropriate to assess child-oriented snack food advertisements and

in-store marketing techniques. In addition, training was conducted with two research

assistants one week prior to data collection.

Advertisements were defined as any posters, stickers, free-standing signs, banners, painting

on walls, or flags inside or outside stores. They were considered child-oriented if they had

images of promotional characters (i.e., licensed, brand-specific or sports character, cartoon,

animal/creature, or celebrity), premium offers (i.e., collectibles, toys, or raffles), children's

television or movie tie-ins, sports references (e.g., soccer balls, team logo), or the word

“child” or synonym (e.g., junior). To allow for comparisons with previously published data

(Bragg et al. 2013) on packaged snack food marketing, we included sweetened beverages

(i.e., fruit and energy drinks), soft drinks, pastries and cookies, savory snacks, dairy

products, cereals, ice cream and frozen desserts, and bottled water. Considering that atoles

(traditional fortified cereal-based drink) are one of the most frequently consumed beverages

among Guatemalan children (Montenegro-Bethancourt et al. 2010), we also included

packaged atoles as a category.

For data entry we used REDCap™ web-based application. Descriptive statistics were used

to summarize total and child-oriented advertisements. Median (25th – 75th percentiles) was

used to describe the distribution of advertisements (total, child-oriented, interior and

exterior) per store. Analyses were done with Fisher's exact and Chi-square tests for

categorical variables, and Wilcoxon ranksum test for continuous variables, using STATA®

software (version 11.1, 2009).

Chacon et al. Page 3

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

2012). Most children enrolled in public schools are from low socioeconomic status (World

Bank 2009) and enrollment in primary education is 95.8% (60% completion) (Guatemala

Human Rights Commission 2010). We obtained permission from the School District

Supervisor and each school principal to survey kiosks inside the schools for food

advertising.

All food kiosks located inside schools were surveyed. Using Google™ Earth, we identified

all stores located in a 200 meters radius centered on each school's entrance and surveyed the

distance in meters between the school entrance and each store. We arbitrarily categorized

the distance between the school entrance and stores as less than 170 meters and equal or

more than 170 meters as we considered this a reasonable distance for children between 4 to

12 years of age to walk to and from school.

We adapted the tobacco point of sale advertisement checklist by Cohen et al (Cohen et al.

2008), and adapted by Barnoya et al (Barnoya et al. 2010) to assess the store type (i.e., small

store, large store, school kiosk, street vendor, pharmacy, service station), total number of

snack food advertisements and those child-oriented inside and outside stores. We also

assessed the number of stores with snack foods displayed at the counter or snack foods less

than 50 cm from tobacco products, and in-store marketing techniques (display racks,

refrigerators, containers, and shelves). The checklist was pilot tested in seven stores located

in Mixco and found to be appropriate to assess child-oriented snack food advertisements and

in-store marketing techniques. In addition, training was conducted with two research

assistants one week prior to data collection.

Advertisements were defined as any posters, stickers, free-standing signs, banners, painting

on walls, or flags inside or outside stores. They were considered child-oriented if they had

images of promotional characters (i.e., licensed, brand-specific or sports character, cartoon,

animal/creature, or celebrity), premium offers (i.e., collectibles, toys, or raffles), children's

television or movie tie-ins, sports references (e.g., soccer balls, team logo), or the word

“child” or synonym (e.g., junior). To allow for comparisons with previously published data

(Bragg et al. 2013) on packaged snack food marketing, we included sweetened beverages

(i.e., fruit and energy drinks), soft drinks, pastries and cookies, savory snacks, dairy

products, cereals, ice cream and frozen desserts, and bottled water. Considering that atoles

(traditional fortified cereal-based drink) are one of the most frequently consumed beverages

among Guatemalan children (Montenegro-Bethancourt et al. 2010), we also included

packaged atoles as a category.

For data entry we used REDCap™ web-based application. Descriptive statistics were used

to summarize total and child-oriented advertisements. Median (25th – 75th percentiles) was

used to describe the distribution of advertisements (total, child-oriented, interior and

exterior) per store. Analyses were done with Fisher's exact and Chi-square tests for

categorical variables, and Wilcoxon ranksum test for continuous variables, using STATA®

software (version 11.1, 2009).

Chacon et al. Page 3

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Results

We found 64 stores inside (n=2) and around (n=62) two preschools and two primary schools

in Mixco. Nine were closed at the time of the assessment; therefore 55 stores were surveyed.

Among these, 58.2% (n=32) were small stores, 32.7% (n=18) large stores, 5.5% (n=3) street

vendors, and 3.6% (n=2) school kiosks. Thirteen stores (20.3%) had no advertising (6 small,

4 large, and 3 street vendors).

There were 321 snack food advertisements and most were on sweetened beverages (37%)

and soft drinks (30%). Twenty-eight advertisements (8.7%) were on pastries and cookies, 25

(7.8%) on savory snacks, 24 (7.5%) on dairy products, 17 (5.3%) on cereals, and 7 (2.2%)

on ice cream and frozen desserts. Twenty-nine percent (n=92) of all snack food

advertisements found in stores were child-oriented. We found 3 water advertisements (no

child-oriented). Atoles (100.0%), cereals (94.1%), and ice cream and frozen desserts

(71.4%) had the greatest proportion of child-oriented advertising, while 9 (36%) of savory

snacks were child-oriented (p<0.0001).

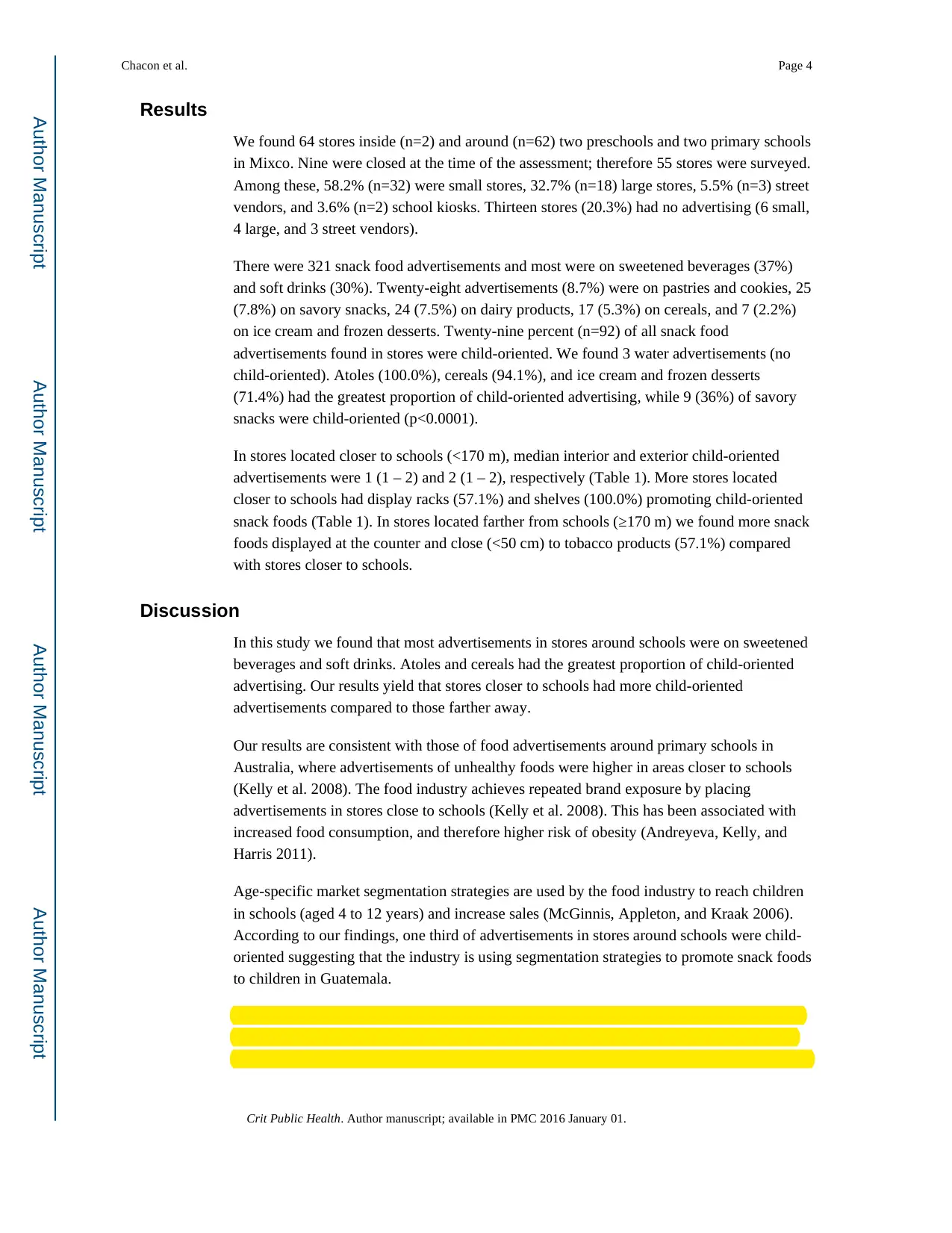

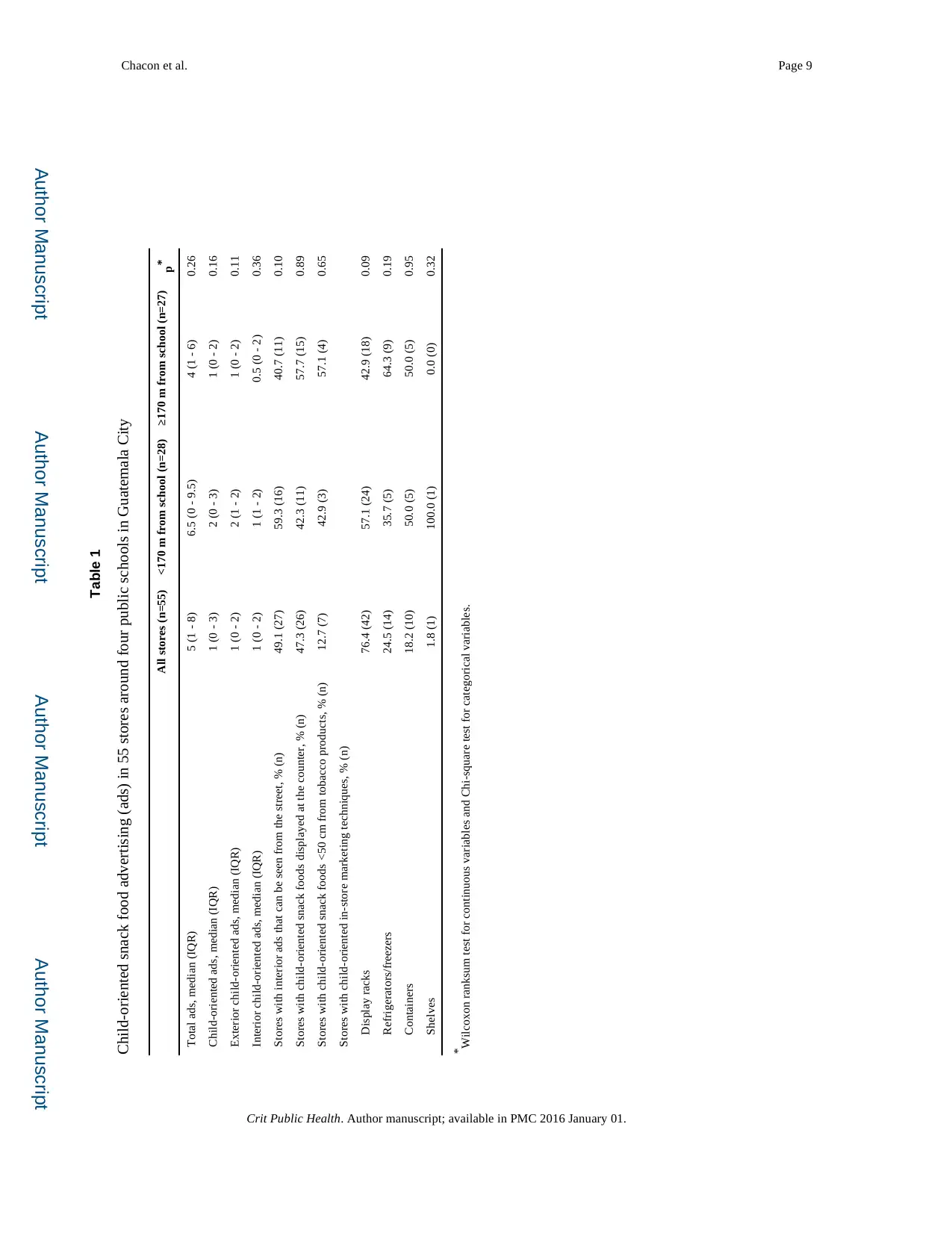

In stores located closer to schools (<170 m), median interior and exterior child-oriented

advertisements were 1 (1 – 2) and 2 (1 – 2), respectively (Table 1). More stores located

closer to schools had display racks (57.1%) and shelves (100.0%) promoting child-oriented

snack foods (Table 1). In stores located farther from schools (≥170 m) we found more snack

foods displayed at the counter and close (<50 cm) to tobacco products (57.1%) compared

with stores closer to schools.

Discussion

In this study we found that most advertisements in stores around schools were on sweetened

beverages and soft drinks. Atoles and cereals had the greatest proportion of child-oriented

advertising. Our results yield that stores closer to schools had more child-oriented

advertisements compared to those farther away.

Our results are consistent with those of food advertisements around primary schools in

Australia, where advertisements of unhealthy foods were higher in areas closer to schools

(Kelly et al. 2008). The food industry achieves repeated brand exposure by placing

advertisements in stores close to schools (Kelly et al. 2008). This has been associated with

increased food consumption, and therefore higher risk of obesity (Andreyeva, Kelly, and

Harris 2011).

Age-specific market segmentation strategies are used by the food industry to reach children

in schools (aged 4 to 12 years) and increase sales (McGinnis, Appleton, and Kraak 2006).

According to our findings, one third of advertisements in stores around schools were child-

oriented suggesting that the industry is using segmentation strategies to promote snack foods

to children in Guatemala.

Product placement at the point-of-sale influences choice and increases sales (Glanz, Bader,

and Iyer 2012). In our sample, stores located closer to schools had more display racks and

shelves promoting child-oriented snack foods, compared to those farther away. This in-store

Chacon et al. Page 4

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

We found 64 stores inside (n=2) and around (n=62) two preschools and two primary schools

in Mixco. Nine were closed at the time of the assessment; therefore 55 stores were surveyed.

Among these, 58.2% (n=32) were small stores, 32.7% (n=18) large stores, 5.5% (n=3) street

vendors, and 3.6% (n=2) school kiosks. Thirteen stores (20.3%) had no advertising (6 small,

4 large, and 3 street vendors).

There were 321 snack food advertisements and most were on sweetened beverages (37%)

and soft drinks (30%). Twenty-eight advertisements (8.7%) were on pastries and cookies, 25

(7.8%) on savory snacks, 24 (7.5%) on dairy products, 17 (5.3%) on cereals, and 7 (2.2%)

on ice cream and frozen desserts. Twenty-nine percent (n=92) of all snack food

advertisements found in stores were child-oriented. We found 3 water advertisements (no

child-oriented). Atoles (100.0%), cereals (94.1%), and ice cream and frozen desserts

(71.4%) had the greatest proportion of child-oriented advertising, while 9 (36%) of savory

snacks were child-oriented (p<0.0001).

In stores located closer to schools (<170 m), median interior and exterior child-oriented

advertisements were 1 (1 – 2) and 2 (1 – 2), respectively (Table 1). More stores located

closer to schools had display racks (57.1%) and shelves (100.0%) promoting child-oriented

snack foods (Table 1). In stores located farther from schools (≥170 m) we found more snack

foods displayed at the counter and close (<50 cm) to tobacco products (57.1%) compared

with stores closer to schools.

Discussion

In this study we found that most advertisements in stores around schools were on sweetened

beverages and soft drinks. Atoles and cereals had the greatest proportion of child-oriented

advertising. Our results yield that stores closer to schools had more child-oriented

advertisements compared to those farther away.

Our results are consistent with those of food advertisements around primary schools in

Australia, where advertisements of unhealthy foods were higher in areas closer to schools

(Kelly et al. 2008). The food industry achieves repeated brand exposure by placing

advertisements in stores close to schools (Kelly et al. 2008). This has been associated with

increased food consumption, and therefore higher risk of obesity (Andreyeva, Kelly, and

Harris 2011).

Age-specific market segmentation strategies are used by the food industry to reach children

in schools (aged 4 to 12 years) and increase sales (McGinnis, Appleton, and Kraak 2006).

According to our findings, one third of advertisements in stores around schools were child-

oriented suggesting that the industry is using segmentation strategies to promote snack foods

to children in Guatemala.

Product placement at the point-of-sale influences choice and increases sales (Glanz, Bader,

and Iyer 2012). In our sample, stores located closer to schools had more display racks and

shelves promoting child-oriented snack foods, compared to those farther away. This in-store

Chacon et al. Page 4

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

marketing technique is likely to influence children's purchase of unhealthy snacks at the

point of sale. Regarding tobacco products, most stores had tobacco products displayed near

snack foods. Therefore, as tobacco, the food industry is using the point of sale as yet

unregulated marketing strategy in Guatemala. Placing both products is associated with

increased brand recognition and consumption (or initiation in the case of cigarettes) (Hosler

and Kammer 2012; Henriksen et al. 2010; Barnoya et al. 2010).

Snack food advertising has been previously documented near schools and in neighborhoods

of different socioeconomic status in different countries (Maher, Wilson, and Signal 2005;

Batada et al. 2008; Gebauer and Laska 2011). Unhealthy snack food and beverage

advertising has been found to be higher in stores (including near schools) and in low

socioeconomic status neighborhoods (Yancey et al. 2009). However, only one has focused

on child-oriented advertising and distance from school, and included all advertising (Kelly et

al. 2008). Our findings are in agreement with what has been previously published and add

that child-oriented snack food advertising is highly prevalent near schools in Guatemala, a

LMIC.

Even though data on the companies responsible for advertising snack foods in Guatemala is

lacking, multinational companies (e.g., PepsiCo, The Coca-Cola Company) dominate the

beverage market as in the rest of Latin America (Comision Economica para América Latina

y el Caribe 2005). Therefore, globalization is disproportionately benefiting multinational

companies, promoting economic inequality and fueling the obesity epidemic (De Vogli et al.

2013).

Our study should be viewed in light of some limitations. We only described child-oriented

snack food advertisements and not all food advertisements. Similar to the Bragg, et al. study

(Bragg et al. 2013), advertising of confectioneries were not included and therefore our

results cannot be generalized to these snacks also marketed to children. Additionally, even

though our sample was not intended to be representative of the entire country, child-oriented

advertisements are likely to be the same nationwide considering convenience stores are

found in almost every neighborhood nationwide.

In conclusion, child-oriented snack food advertising at the point of sale is a strategy widely

used by the food industry to reach children. Just as the tobacco industry takes advantage of

the unregulated environment in Guatemala, point of sale advertising is only one of several

channels the food industry uses. Any effort to promote healthy eating inside schools would

be ruled out by the heavy exposure to this pervasive form of marketing in stores around

schools. Therefore, any comprehensive population strategy aiming to decrease exposure to

unhealthy snack food advertising should include the point of sale just as other traditional

advertising venues. While the food industry would likely oppose, a ban on snack food

advertisements in stores around schools is possible, similar to tobacco advertising

restrictions.

Supplementary Material

Refer to Web version on PubMed Central for supplementary material.

Chacon et al. Page 5

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

point of sale. Regarding tobacco products, most stores had tobacco products displayed near

snack foods. Therefore, as tobacco, the food industry is using the point of sale as yet

unregulated marketing strategy in Guatemala. Placing both products is associated with

increased brand recognition and consumption (or initiation in the case of cigarettes) (Hosler

and Kammer 2012; Henriksen et al. 2010; Barnoya et al. 2010).

Snack food advertising has been previously documented near schools and in neighborhoods

of different socioeconomic status in different countries (Maher, Wilson, and Signal 2005;

Batada et al. 2008; Gebauer and Laska 2011). Unhealthy snack food and beverage

advertising has been found to be higher in stores (including near schools) and in low

socioeconomic status neighborhoods (Yancey et al. 2009). However, only one has focused

on child-oriented advertising and distance from school, and included all advertising (Kelly et

al. 2008). Our findings are in agreement with what has been previously published and add

that child-oriented snack food advertising is highly prevalent near schools in Guatemala, a

LMIC.

Even though data on the companies responsible for advertising snack foods in Guatemala is

lacking, multinational companies (e.g., PepsiCo, The Coca-Cola Company) dominate the

beverage market as in the rest of Latin America (Comision Economica para América Latina

y el Caribe 2005). Therefore, globalization is disproportionately benefiting multinational

companies, promoting economic inequality and fueling the obesity epidemic (De Vogli et al.

2013).

Our study should be viewed in light of some limitations. We only described child-oriented

snack food advertisements and not all food advertisements. Similar to the Bragg, et al. study

(Bragg et al. 2013), advertising of confectioneries were not included and therefore our

results cannot be generalized to these snacks also marketed to children. Additionally, even

though our sample was not intended to be representative of the entire country, child-oriented

advertisements are likely to be the same nationwide considering convenience stores are

found in almost every neighborhood nationwide.

In conclusion, child-oriented snack food advertising at the point of sale is a strategy widely

used by the food industry to reach children. Just as the tobacco industry takes advantage of

the unregulated environment in Guatemala, point of sale advertising is only one of several

channels the food industry uses. Any effort to promote healthy eating inside schools would

be ruled out by the heavy exposure to this pervasive form of marketing in stores around

schools. Therefore, any comprehensive population strategy aiming to decrease exposure to

unhealthy snack food advertising should include the point of sale just as other traditional

advertising venues. While the food industry would likely oppose, a ban on snack food

advertisements in stores around schools is possible, similar to tobacco advertising

restrictions.

Supplementary Material

Refer to Web version on PubMed Central for supplementary material.

Chacon et al. Page 5

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa,

Canada [Project number 106883-001]. Joaquin Barnoya receives additional support from an unrestricted grant from

the American Cancer Society and from Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation. Additional support was received from

NIH Research Grant # D43 TW009315 funded by the Fogarty International Center.

References

Adams J, Tyrrell R, Adamson AJ, White M. Effect of restrictions on television food advertising to

children on exposure to advertisements for ‘less healthy’ foods: repeat cross-sectional study. PLoS

One. 2012; 7(2):e31578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031578PONE-D-11-21779 [pii]. [PubMed:

22355376]

Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: associations with

children's fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2011; 9(3):221–33.

doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.02.004S1570-677X(11)00029-3 [pii. [PubMed: 21439918]

Barnoya J, Mejia R, Szeinman D, Kummerfeldt CE. Tobacco point-of-sale advertising in Guatemala

City, Guatemala and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Tob Control. 2010; 19(4):338–41. doi: 10.1136/tc.

2009.031898tc.2009.031898 [pii]. [PubMed: 20530136]

Batada A, Seitz MD, Wootan MG, Story M. Nine out of 10 food advertisements shown during

Saturday morning children's television programming are for foods high in fat, sodium, or added

sugars, or low in nutrients. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008; 108(4):673–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.015

S0002-8223(08)00016-3 [pii]. [PubMed: 18375225]

Bogart WA. Law as a tool in “the war on obesity”: useful interventions, maybe, but, first, what's the

problem? J Law Med Ethics. 2013; 41(1):28–41. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12003. [PubMed: 23581655]

Bouchard C. The biological predisposition to obesity: beyond the thrifty genotype scenario. Int J Obes

(Lond). 2007; 31(9):1337–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803610. [PubMed: 17356524]

Bragg MA, Liu PJ, Roberto CA, Sarda V, Harris JL, Brownell KD. The use of sports references in

marketing of food and beverage products in supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2013; 16(4):738–42.

doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003163 S1368980012003163 [pii]. [PubMed: 22874497]

Cohen JE, Planinac LC, Griffin K, Robinson DJ, O'Connor SC, Lavack A, Thompson FE, Di Nardo J.

Tobacco promotions at point-of-sale: the last hurrah. Can J Public Health. 2008; 99(3):166–71.

[PubMed: 18615934]

Comision Economica para América Latina y el Caribe. Las translatinas en la industria de los alimentos

y bebidas. 2005. Retrieved from: http://www.cepal.org/publicaciones/xml/4/24294/

lcg2309e_Cap_V.pdf

Consejo de Ministros de Integración Económica. Reglamento técnico centroamericano del etiquetado

de productos alimenticios preenvasados para consumo humano para la población a partir de 3 años

de edad. 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.dgrs.gob.hn/documents/Resoluciones/

AlimentosBebidas/17990000004172 RTCA Etiq Nutricional.pdf

De Vogli R, Kouvonen A, Elovainio M, Marmot M. Economic globalization, inequality and body

mass index: a cross-national analysis of 127 countries. Critical Public Health. 2013; 24(1)

De Vogli R, Kouvonen A, Gimeno D. “Globesization”: Ecological evidence on the relationship

between fast food outlets and obesity among 26 advanced economies. Critical Public Health. 2011;

21(4)

Gebauer H, Laska MN. Convenience stores surrounding urban schools: an assessment of healthy food

availability, advertising, and product placement. J Urban Health. 2011; 88(4):616–22. doi:

10.1007/s11524-011-9576-3. [PubMed: 21491151]

Glanz K, Bader MD, Iyer S. Retail grocery store marketing strategies and obesity: an integrative

review. Am J Prev Med. 2012; 42(5):503–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.

2012.01.013S0749-3797(12)00058-X [pii]. [PubMed: 22516491]

Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Fox MK, Laird N. Reducing obesity via a

school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med. 1999; 153(4):409–18. [PubMed: 10201726]

Chacon et al. Page 6

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa,

Canada [Project number 106883-001]. Joaquin Barnoya receives additional support from an unrestricted grant from

the American Cancer Society and from Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation. Additional support was received from

NIH Research Grant # D43 TW009315 funded by the Fogarty International Center.

References

Adams J, Tyrrell R, Adamson AJ, White M. Effect of restrictions on television food advertising to

children on exposure to advertisements for ‘less healthy’ foods: repeat cross-sectional study. PLoS

One. 2012; 7(2):e31578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031578PONE-D-11-21779 [pii]. [PubMed:

22355376]

Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: associations with

children's fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2011; 9(3):221–33.

doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.02.004S1570-677X(11)00029-3 [pii. [PubMed: 21439918]

Barnoya J, Mejia R, Szeinman D, Kummerfeldt CE. Tobacco point-of-sale advertising in Guatemala

City, Guatemala and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Tob Control. 2010; 19(4):338–41. doi: 10.1136/tc.

2009.031898tc.2009.031898 [pii]. [PubMed: 20530136]

Batada A, Seitz MD, Wootan MG, Story M. Nine out of 10 food advertisements shown during

Saturday morning children's television programming are for foods high in fat, sodium, or added

sugars, or low in nutrients. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008; 108(4):673–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.015

S0002-8223(08)00016-3 [pii]. [PubMed: 18375225]

Bogart WA. Law as a tool in “the war on obesity”: useful interventions, maybe, but, first, what's the

problem? J Law Med Ethics. 2013; 41(1):28–41. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12003. [PubMed: 23581655]

Bouchard C. The biological predisposition to obesity: beyond the thrifty genotype scenario. Int J Obes

(Lond). 2007; 31(9):1337–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803610. [PubMed: 17356524]

Bragg MA, Liu PJ, Roberto CA, Sarda V, Harris JL, Brownell KD. The use of sports references in

marketing of food and beverage products in supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2013; 16(4):738–42.

doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003163 S1368980012003163 [pii]. [PubMed: 22874497]

Cohen JE, Planinac LC, Griffin K, Robinson DJ, O'Connor SC, Lavack A, Thompson FE, Di Nardo J.

Tobacco promotions at point-of-sale: the last hurrah. Can J Public Health. 2008; 99(3):166–71.

[PubMed: 18615934]

Comision Economica para América Latina y el Caribe. Las translatinas en la industria de los alimentos

y bebidas. 2005. Retrieved from: http://www.cepal.org/publicaciones/xml/4/24294/

lcg2309e_Cap_V.pdf

Consejo de Ministros de Integración Económica. Reglamento técnico centroamericano del etiquetado

de productos alimenticios preenvasados para consumo humano para la población a partir de 3 años

de edad. 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.dgrs.gob.hn/documents/Resoluciones/

AlimentosBebidas/17990000004172 RTCA Etiq Nutricional.pdf

De Vogli R, Kouvonen A, Elovainio M, Marmot M. Economic globalization, inequality and body

mass index: a cross-national analysis of 127 countries. Critical Public Health. 2013; 24(1)

De Vogli R, Kouvonen A, Gimeno D. “Globesization”: Ecological evidence on the relationship

between fast food outlets and obesity among 26 advanced economies. Critical Public Health. 2011;

21(4)

Gebauer H, Laska MN. Convenience stores surrounding urban schools: an assessment of healthy food

availability, advertising, and product placement. J Urban Health. 2011; 88(4):616–22. doi:

10.1007/s11524-011-9576-3. [PubMed: 21491151]

Glanz K, Bader MD, Iyer S. Retail grocery store marketing strategies and obesity: an integrative

review. Am J Prev Med. 2012; 42(5):503–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.

2012.01.013S0749-3797(12)00058-X [pii]. [PubMed: 22516491]

Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Fox MK, Laird N. Reducing obesity via a

school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med. 1999; 153(4):409–18. [PubMed: 10201726]

Chacon et al. Page 6

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Guatemala Human Rights Commission. Education in Guatemala Fact Sheet. http://www.ghrc-usa.org/

Publications/factsheet_education.pdf

Halford JC, Gillespie J, Brown V, Pontin EE, Dovey TM. Effect of television advertisements for foods

on food consumption in children. Appetite. 2004; 42(2):221–5. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.

2003.11.006S0195666303001910 [pii]. [PubMed: 15010186]

Harris JL, Pomeranz JL, Lobstein T, Brownell KD. A crisis in the marketplace: how food marketing

contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009; 30:211–25.

doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100304. [PubMed: 18976142]

Hastings, G.; Stead, M.; McDermott, L.; Forsyth, A.; MacKintosh, A.; Rayner, M.; Godfrey, C.;

Caraher, M.; Angus, K. The extent, nature and effects of food promotion to children: A review of

the evidence. 2005. Retrieved from: http://libdoc.who.int/publications/

2007/9789241595247_eng.pdf

Hawkes C, Lobstein T. Regulating the commercial promotion of food to children: a survey of actions

worldwide. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011; 6(2):83–94. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.486836. [PubMed:

20874086]

Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail

cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010; 126(2):232–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.

2009-3021peds.2009-3021 [pii]. [PubMed: 20643725]

Hosler AS, Kammer JR. Point-of-purchase tobacco access and advertisement in food stores. Tob

Control. 2012; 21(4):451–2. doi: 10.1136/

tobaccocontrol-2011-050221tobaccocontrol-2011-050221 [pii]. [PubMed: 22411730]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Guatemala. Estimaciones de la Población Total por Municipio.

http://www.ine.gob.gt/

Kelly B, Cretikos M, Rogers K, King L. The commercial food landscape: outdoor food advertising

around primary schools in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008; 32(6):522–8. doi: 10.1111/j.

1753-6405.2008.00303.xAZPH303 [pii]. [PubMed: 19076742]

Letona P, Chacon V, Roberto C, Barnoya J. Effects of licensed characters on children's taste and snack

preferences in Guatemala, a low/middle income country. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014 doi: 10.1038/ijo.

2014.38.

Maher A, Wilson N, Signal L. Advertising and availability of 'obesogenic' foods around New Zealand

secondary schools: a pilot study. N Z Med J. 2005; 118(1218):U1556. [PubMed: 16027747]

Mazur A, Telega G, Kotowicz A, Malek H, Jarochowicz S, Gierczak B, Mazurkiewicz M, et al. Impact

of food advertising on food purchases by students in primary and secondary schools in south-

eastern Poland. Public Health Nutr. 2008; 11(9):978–81. doi: 10.1017/

S1368980008002000S1368980008002000 [pii]. [PubMed: 18353194]

McGinnis, JM.; Appleton, J.; Kraak, V. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or

Opportunity?. The National Academies Press.; Washington, D.C.: 2006.

Ministerio de Educación. Anuario Estadístico. 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.mineduc.gob.gt/

estadistica/2012/main.html

Montenegro-Bethancourt G, Vossenaar M, Doak CM, Solomons NW. Contribution of beverages to

energy, macronutrient and micronutrient intake of third- and fourth-grade schoolchildren in

Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Matern Child Nutr. 2010; 6(2):174–89. doi: 10.1111/j.

1740-8709.2009.00193.xMCN193 [pii]. [PubMed: 20624213]

Ofcom. Television advertising of food and drink products to children. Final statement. http://

stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/consultations/foodads_new/statement/statement.pdf

Rivera JA, Cossio T, Pedraza L, Aburto T, Sanchez T, Martorell R. Childhood and adolescent

overweight and obesity in Latin America: a systematic review. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/

S2213-8587(13)70173-6.

Robinson TN. Reducing children's television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial.

JAMA. 1999; 282(16):1561–7. doi: joc90434 [pii]. [PubMed: 10546696]

Schwartz MB, Puhl R. Childhood obesity: a societal problem to solve. Obes Rev. 2003; 4(1):57–71.

[PubMed: 12608527]

Chacon et al. Page 7

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Publications/factsheet_education.pdf

Halford JC, Gillespie J, Brown V, Pontin EE, Dovey TM. Effect of television advertisements for foods

on food consumption in children. Appetite. 2004; 42(2):221–5. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.

2003.11.006S0195666303001910 [pii]. [PubMed: 15010186]

Harris JL, Pomeranz JL, Lobstein T, Brownell KD. A crisis in the marketplace: how food marketing

contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009; 30:211–25.

doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100304. [PubMed: 18976142]

Hastings, G.; Stead, M.; McDermott, L.; Forsyth, A.; MacKintosh, A.; Rayner, M.; Godfrey, C.;

Caraher, M.; Angus, K. The extent, nature and effects of food promotion to children: A review of

the evidence. 2005. Retrieved from: http://libdoc.who.int/publications/

2007/9789241595247_eng.pdf

Hawkes C, Lobstein T. Regulating the commercial promotion of food to children: a survey of actions

worldwide. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011; 6(2):83–94. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.486836. [PubMed:

20874086]

Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail

cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010; 126(2):232–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.

2009-3021peds.2009-3021 [pii]. [PubMed: 20643725]

Hosler AS, Kammer JR. Point-of-purchase tobacco access and advertisement in food stores. Tob

Control. 2012; 21(4):451–2. doi: 10.1136/

tobaccocontrol-2011-050221tobaccocontrol-2011-050221 [pii]. [PubMed: 22411730]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Guatemala. Estimaciones de la Población Total por Municipio.

http://www.ine.gob.gt/

Kelly B, Cretikos M, Rogers K, King L. The commercial food landscape: outdoor food advertising

around primary schools in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008; 32(6):522–8. doi: 10.1111/j.

1753-6405.2008.00303.xAZPH303 [pii]. [PubMed: 19076742]

Letona P, Chacon V, Roberto C, Barnoya J. Effects of licensed characters on children's taste and snack

preferences in Guatemala, a low/middle income country. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014 doi: 10.1038/ijo.

2014.38.

Maher A, Wilson N, Signal L. Advertising and availability of 'obesogenic' foods around New Zealand

secondary schools: a pilot study. N Z Med J. 2005; 118(1218):U1556. [PubMed: 16027747]

Mazur A, Telega G, Kotowicz A, Malek H, Jarochowicz S, Gierczak B, Mazurkiewicz M, et al. Impact

of food advertising on food purchases by students in primary and secondary schools in south-

eastern Poland. Public Health Nutr. 2008; 11(9):978–81. doi: 10.1017/

S1368980008002000S1368980008002000 [pii]. [PubMed: 18353194]

McGinnis, JM.; Appleton, J.; Kraak, V. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or

Opportunity?. The National Academies Press.; Washington, D.C.: 2006.

Ministerio de Educación. Anuario Estadístico. 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.mineduc.gob.gt/

estadistica/2012/main.html

Montenegro-Bethancourt G, Vossenaar M, Doak CM, Solomons NW. Contribution of beverages to

energy, macronutrient and micronutrient intake of third- and fourth-grade schoolchildren in

Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Matern Child Nutr. 2010; 6(2):174–89. doi: 10.1111/j.

1740-8709.2009.00193.xMCN193 [pii]. [PubMed: 20624213]

Ofcom. Television advertising of food and drink products to children. Final statement. http://

stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/consultations/foodads_new/statement/statement.pdf

Rivera JA, Cossio T, Pedraza L, Aburto T, Sanchez T, Martorell R. Childhood and adolescent

overweight and obesity in Latin America: a systematic review. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/

S2213-8587(13)70173-6.

Robinson TN. Reducing children's television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial.

JAMA. 1999; 282(16):1561–7. doi: joc90434 [pii]. [PubMed: 10546696]

Schwartz MB, Puhl R. Childhood obesity: a societal problem to solve. Obes Rev. 2003; 4(1):57–71.

[PubMed: 12608527]

Chacon et al. Page 7

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

World Bank. Guatemala poverty assessment good performance at low levels. 2009. Retrieved from:

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLACREGTOPPOVANA/Resources/

GuatemalaPovertyAssessmentEnglish.pdf

World Health Organization. Marketing food to children: Changes in the global regulatory environment

2004 - 2006. 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/

regulatory_environment_CHawkes07.pdf

World Health Organization. Malnutrition in infants and young children in Latin America and the

Caribbean: Achieving the Millennium Development Goals. 2008. Retrieved from: http://

www.unscn.org/layout/modules/resources/files/

Malnutrition_in_Infants_and_Young_Children_in_LAC,__Achieving_the_MDGs.pdf

World Health Organization. Guatemala Global School-Based Student Health Survey. 2009. Retrieved

from: http://www.who.int/chp/gshs/2009_Guatemala_GSHS_Questionnaire.pdf

Yancey AK, Cole BL, Brown R, Williams JD, Hillier A, Kline RS, Ashe M, Grier SA, Backman D,

McCarthy WJ. A cross-sectional prevalence study of ethnically targeted and general audience

outdoor obesity-related advertising. Milbank Q. 2009; 87(1):155–84. doi: 10.1111/j.

1468-0009.2009.00551.xMILQ551 [pii]. [PubMed: 19298419]

Chacon et al. Page 8

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLACREGTOPPOVANA/Resources/

GuatemalaPovertyAssessmentEnglish.pdf

World Health Organization. Marketing food to children: Changes in the global regulatory environment

2004 - 2006. 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/

regulatory_environment_CHawkes07.pdf

World Health Organization. Malnutrition in infants and young children in Latin America and the

Caribbean: Achieving the Millennium Development Goals. 2008. Retrieved from: http://

www.unscn.org/layout/modules/resources/files/

Malnutrition_in_Infants_and_Young_Children_in_LAC,__Achieving_the_MDGs.pdf

World Health Organization. Guatemala Global School-Based Student Health Survey. 2009. Retrieved

from: http://www.who.int/chp/gshs/2009_Guatemala_GSHS_Questionnaire.pdf

Yancey AK, Cole BL, Brown R, Williams JD, Hillier A, Kline RS, Ashe M, Grier SA, Backman D,

McCarthy WJ. A cross-sectional prevalence study of ethnically targeted and general audience

outdoor obesity-related advertising. Milbank Q. 2009; 87(1):155–84. doi: 10.1111/j.

1468-0009.2009.00551.xMILQ551 [pii]. [PubMed: 19298419]

Chacon et al. Page 8

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Chacon et al. Page 9

Table 1

Child-oriented snack food advertising (ads) in 55 stores around four public schools in Guatemala City

All stores (n=55) <170 m from school (n=28) ≥170 m from school (n=27) p*

Total ads, median (IQR) 5 (1 - 8) 6.5 (0 - 9.5) 4 (1 - 6) 0.26

Child-oriented ads, median (IQR) 1 (0 - 3) 2 (0 - 3) 1 (0 - 2) 0.16

Exterior child-oriented ads, median (IQR) 1 (0 - 2) 2 (1 - 2) 1 (0 - 2) 0.11

Interior child-oriented ads, median (IQR) 1 (0 - 2) 1 (1 - 2) 0.5 (0 - 2) 0.36

Stores with interior ads that can be seen from the street, % (n) 49.1 (27) 59.3 (16) 40.7 (11) 0.10

Stores with child-oriented snack foods displayed at the counter, % (n) 47.3 (26) 42.3 (11) 57.7 (15) 0.89

Stores with child-oriented snack foods <50 cm from tobacco products, % (n) 12.7 (7) 42.9 (3) 57.1 (4) 0.65

Stores with child-oriented in-store marketing techniques, % (n)

Display racks 76.4 (42) 57.1 (24) 42.9 (18) 0.09

Refrigerators/freezers 24.5 (14) 35.7 (5) 64.3 (9) 0.19

Containers 18.2 (10) 50.0 (5) 50.0 (5) 0.95

Shelves 1.8 (1) 100.0 (1) 0.0 (0) 0.32

*Wilcoxon ranksum test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

Chacon et al. Page 9

Table 1

Child-oriented snack food advertising (ads) in 55 stores around four public schools in Guatemala City

All stores (n=55) <170 m from school (n=28) ≥170 m from school (n=27) p*

Total ads, median (IQR) 5 (1 - 8) 6.5 (0 - 9.5) 4 (1 - 6) 0.26

Child-oriented ads, median (IQR) 1 (0 - 3) 2 (0 - 3) 1 (0 - 2) 0.16

Exterior child-oriented ads, median (IQR) 1 (0 - 2) 2 (1 - 2) 1 (0 - 2) 0.11

Interior child-oriented ads, median (IQR) 1 (0 - 2) 1 (1 - 2) 0.5 (0 - 2) 0.36

Stores with interior ads that can be seen from the street, % (n) 49.1 (27) 59.3 (16) 40.7 (11) 0.10

Stores with child-oriented snack foods displayed at the counter, % (n) 47.3 (26) 42.3 (11) 57.7 (15) 0.89

Stores with child-oriented snack foods <50 cm from tobacco products, % (n) 12.7 (7) 42.9 (3) 57.1 (4) 0.65

Stores with child-oriented in-store marketing techniques, % (n)

Display racks 76.4 (42) 57.1 (24) 42.9 (18) 0.09

Refrigerators/freezers 24.5 (14) 35.7 (5) 64.3 (9) 0.19

Containers 18.2 (10) 50.0 (5) 50.0 (5) 0.95

Shelves 1.8 (1) 100.0 (1) 0.0 (0) 0.32

*Wilcoxon ranksum test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Crit Public Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 January 01.

1 out of 9

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.