Research Report: Social Engagement & Antipsychotic Use in LTCFs

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/09

|9

|7533

|133

Report

AI Summary

This research report, published in the Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, investigates the association between social engagement (SE) and the use of antipsychotics in addressing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in newly admitted residents to long-term care facilities (LTCFs). The cross-sectional study utilized administrative data from the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Data Set (RAI-MDS) collected between 2008 and 2011 in the Fraser Health region, British Columbia, Canada. The study included 2,639 residents aged 65 or older diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to predict antipsychotic use based on SE. Results showed that SE was a statistically significant predictor of antipsychotic use when controlling for sociodemographic variables, but this association disappeared when controlling for health variables. The report concludes that the relationship between SE and antipsychotic use is complex and warrants further research. The study highlights the need for alternative approaches to manage BPSD and improve the quality of life for residents in LTCFs.

OriginalResearch Report

Social Engagement and Antipsychotic

Use in Addressing the Behavioral and

Psychological Symptoms of Dementia

in Long-Term Care Facilities

Nasrin Saleh1, Margaret Penning2, Denise Cloutier3,

Anastasia Mallidou1, Kim Nuernberger4, and Deanne Taylor5

Abstract

Objectives: The use of antipsychotics,mainly to address the behavioraland psychologicalsymptoms of dementia (BPSD),

remains a common and frequent practice in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) despite their associated risks.The objective of

this study was to explore the association between socialengagement (SE) and the use ofantipsychotics in addressing the

BPSD in newly admitted residents to LTCFs.

Methods:A cross-sectionalstudy was undertaken using administrative data,primarily the ResidentAssessmentInstrument

Minimum Data Set (Version 2.0) that collected between 2008 and 2011 (Fraser Health region, British Columbia

data analysis conducted on a sample of2,639 newly admitted residents aged 65 or older with a diagnosis ofAlzheimer’s

disease or other dementias as oftheir first fullor first quarterly assessment.Multivariate logistic regression analyses were

undertaken to predict antipsychotic use based on SE.

Results: SE was found to be a statistically significant predictor of antipsychotic use when controlling for sociod

variables (odds ratio (OR) ¼ .86, p < .0001, confidence interval (CI) [0.82, 0.90]). However, the association dis

controlling for health variables (OR ¼ .97,p ¼ .21,CI [0.97,1.0]).

Conclusion: The prediction of antipsychotic use in newly admitted residents to LTCFs by SE is complex. Furthe

warranted for further examination ofthe association ofantipsychotic use in newly admitted residents to LTCFs.

Keywords

long-term care facilities,residentialcare,socialengagement,antipsychotics

Background

Demand on long-term care facilities (LTCFs) in Canada

is increasing due to the rise of life expectancy and the

numberof personswith dementia.In 2011, 5 million

Canadianswere 65 years of age or older, which is

expected to double by the year 2036 (Canadian Nurses

Association,2013).Almost one million Canadians will

be living with dementia by the year 2036 compared to

450,000 in 2012 (Canadian Life and Health Insurance

Association,2012).This is presenting major challenges

to policy makers and the health-care system and requir-

ing a shift of priorities, adapting innovative approaches

to keep older adults healthy and independent.

1Schoolof Nursing,University ofVictoria,British Columbia,Canada

2Department ofSociology and Institute on Aging and Lifelong Health,

University ofVictoria,British Columbia,Canada

3Department ofGeography and Institute on Aging and Lifelong Health,

University ofVictoria,British Columbia,Canada

4British Columbia Trajectories in Care Project,University ofVictoria,

British Columbia,Canada

5Research and Knowledge Translation,Interior Health Authority,Research

Affiliate,Fraser Health Authority,British Columbia,Canada

Corresponding Author:

Nasrin Saleh,Schoolof Nursing,University ofVictoria,2833 Dufferin

Avenue,Victoria,British Columbia,Canada V8R 3L6.

Email:nasrin@uvic.ca

Canadian Journal of Nursing Research

0(0):1–9

! The Author(s) 2017

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0844562117726253

journals.sagepub.com/home/cjn

Social Engagement and Antipsychotic

Use in Addressing the Behavioral and

Psychological Symptoms of Dementia

in Long-Term Care Facilities

Nasrin Saleh1, Margaret Penning2, Denise Cloutier3,

Anastasia Mallidou1, Kim Nuernberger4, and Deanne Taylor5

Abstract

Objectives: The use of antipsychotics,mainly to address the behavioraland psychologicalsymptoms of dementia (BPSD),

remains a common and frequent practice in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) despite their associated risks.The objective of

this study was to explore the association between socialengagement (SE) and the use ofantipsychotics in addressing the

BPSD in newly admitted residents to LTCFs.

Methods:A cross-sectionalstudy was undertaken using administrative data,primarily the ResidentAssessmentInstrument

Minimum Data Set (Version 2.0) that collected between 2008 and 2011 (Fraser Health region, British Columbia

data analysis conducted on a sample of2,639 newly admitted residents aged 65 or older with a diagnosis ofAlzheimer’s

disease or other dementias as oftheir first fullor first quarterly assessment.Multivariate logistic regression analyses were

undertaken to predict antipsychotic use based on SE.

Results: SE was found to be a statistically significant predictor of antipsychotic use when controlling for sociod

variables (odds ratio (OR) ¼ .86, p < .0001, confidence interval (CI) [0.82, 0.90]). However, the association dis

controlling for health variables (OR ¼ .97,p ¼ .21,CI [0.97,1.0]).

Conclusion: The prediction of antipsychotic use in newly admitted residents to LTCFs by SE is complex. Furthe

warranted for further examination ofthe association ofantipsychotic use in newly admitted residents to LTCFs.

Keywords

long-term care facilities,residentialcare,socialengagement,antipsychotics

Background

Demand on long-term care facilities (LTCFs) in Canada

is increasing due to the rise of life expectancy and the

numberof personswith dementia.In 2011, 5 million

Canadianswere 65 years of age or older, which is

expected to double by the year 2036 (Canadian Nurses

Association,2013).Almost one million Canadians will

be living with dementia by the year 2036 compared to

450,000 in 2012 (Canadian Life and Health Insurance

Association,2012).This is presenting major challenges

to policy makers and the health-care system and requir-

ing a shift of priorities, adapting innovative approaches

to keep older adults healthy and independent.

1Schoolof Nursing,University ofVictoria,British Columbia,Canada

2Department ofSociology and Institute on Aging and Lifelong Health,

University ofVictoria,British Columbia,Canada

3Department ofGeography and Institute on Aging and Lifelong Health,

University ofVictoria,British Columbia,Canada

4British Columbia Trajectories in Care Project,University ofVictoria,

British Columbia,Canada

5Research and Knowledge Translation,Interior Health Authority,Research

Affiliate,Fraser Health Authority,British Columbia,Canada

Corresponding Author:

Nasrin Saleh,Schoolof Nursing,University ofVictoria,2833 Dufferin

Avenue,Victoria,British Columbia,Canada V8R 3L6.

Email:nasrin@uvic.ca

Canadian Journal of Nursing Research

0(0):1–9

! The Author(s) 2017

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0844562117726253

journals.sagepub.com/home/cjn

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Since the early 1990s,LTCFs have moved from a

medicalmodelfocusing on treatmenttoward a social

modelof care emphasizing a home-like environment.

Moreover, the culturechangemovementin LTCFs,

based on the philosophy of person-centered care, focuses

on well-being and quality of life as defined by the resi-

dent.However,the prevalence ofantipsychotic use in

LTCFs remains high (Fischer, Cohen, Forrest,

Schweizer,& Wasylenki,2011),mainly to address the

behavioraland psychologicalsymptomsof dementia

(BPSD) that include aggression,agitation,restlessness,

wandering,hoarding, sleep disturbances,psychosis,

delusions, hallucinations, and sundowning

(Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, & Rosenthal, 1989).

Recently,British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Health

reviewed antipsychotic use in LTCFs and recommended

its use for the treatment of BPSD under severalcondi-

tions (MoH, 2011).These conditions include weighing

the risks againstthe benefits,using those drugsas a

last resort,obtaining informed consentprior to use,

and following the clinical guidelinesof a low dose,

slow titration, and over a short period with close moni-

toring. Yet, the review illustrated that over half (50.3%)

of the residents were prescribed antipsychotics between

April 2010 and June 2011,an increase of 37% within a

decade(MoH, 2011),with similar increasesreported

across Canadian health authorities. While newly

admitted residents are more likely than other residents

to be prescribed at least one antipsychotic during the first

90 days of admission (Huybrechts,Rothman,Silliman,

Brookhart,& Schneeweiss, 2011), antipsychotic use can

be as twice ashigh in residentswith BPSD (Alanen,

Finne-Soveri,Noro, & Leinonen,2006).Antipsychotic

use in older adults,particularly with dementia,is asso-

ciated with multipleside effects(Perucca & Gilliam,

2012)such as increased risksof mortality,falls, and

hip fractures.Furthermore,antipsychotics may worsen

cognition and increase sedative load (Perucca & Gilliam,

2012) that, in turn, may reduce the level of social engage-

ment (SE).

SE is considered essentialto the psychologicaland

physicalwell-being (Bennett,2002)of older adultsin

LTCFs due to challenges within the setting in keeping

older adults active and stimulated.Scholars have pro-

posed that SE might be an alternative to antipsychotics

use (Mallidou, Oliveira, & Borycki, 2013). Socially enga-

ging residents has positive health outcomes,such as a

protectiveeffecton mortality (Bennett,2002;Kiely,

Simon,Jones,& Morris, 2000),and improved function

and cognition (Chen et al.,2013).SE is also associated

with decreased symptomsof depression (Lou,Chi,

Kwan, & Leung, 2013) and is an indicator of quality of

life, as it relates to positive emotions,sense of purpose,

and life satisfaction.Conversely,lonely older adults

often have low self-rated health and low life satisfaction.

Design and Method

Design and Sample

This is a cross-sectional study using administrative data.

Data from the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum

Data Set (RAI-MDS, Version 2.0) and the Continuing

Care Information ManagementSystem were collected

between 2008 and 2011 in the FraserHealth region,

BC, Canada (accessiblepopulation).Fraser Health

operates 7,800 residentialcare beds and has systematic-

ally collected RAI-MDS data on residents since 2007.

The RAI-MDS has been rigorously tested for reliability

and validity in Canada and internationally (Hawes et al.,

1995;Lawton etal., 1998;Mor et al., 2003),enabling

comparison between countries and institutions.Trained

clinicians complete the MDS 2.0 upon residentadmis-

sion and ideally every 3 monthsthereafter.It also is

completed ifchangesin health statusare experienced

by residents.In this study,all measureswere drawn

from assessments undertaken 90 days following admis-

sion to LTCFs.

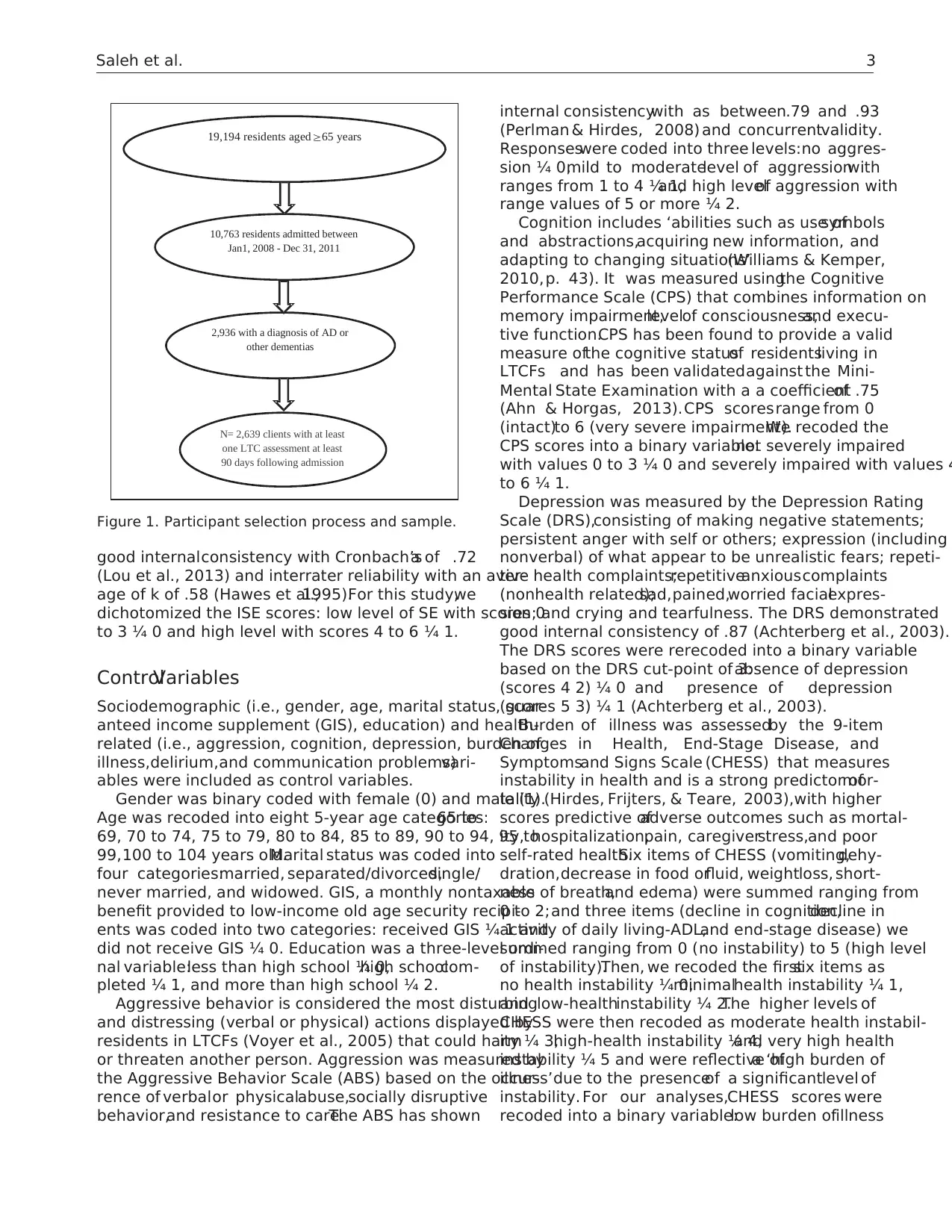

Our initial sample included 10,763 newly admitted

residents(from January 1, 2008, to December31,

2011), aged 65 or older. The final study sample included

2,639 residents who upon admission or in their first full

or quarterly assessment had a diagnosis of dementia and

who had at least one LTC assessment within 90 days of

admission (Figure 1).

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is antipsychotic use,which was

defined as the use of atypicaland typicalantipsychotic

agent(s).It was coded into a binary variable:did not

receive antipsychotic drugs ¼ 0 and received antipsychotics

(one drug atleastonce,regardless ofthe numbers of

drugs or days the drug is received)in the past7 days

prior to the assessment date ¼ 1.

Independent Variable

The independentvariablewas SE, which within the

contextof LTCFs, was defined as those who have ‘a

high sense of initiative and involvement and can respond

adequately to socialstimuliin the socialenvironment,

participate in socialactivitiesand interactwith other

residents and staff’ (Achterberg et al.,2003, p. 213). SE

was measured using the Index ofSocial Engagement

(ISE), an observationalscale that measures the positive

social behavior of residents. It includes six dichotomous

items reflecting whether the resident is at ease interacting

with others, with planned or structured activities, doing

self-initiatedactivities,establishingtheir own goals,

pursuing involvement in facility life, and accepting invi-

tations into most group activities.The ISE has shown

2 Canadian Journalof Nursing Research 0(0)

medicalmodelfocusing on treatmenttoward a social

modelof care emphasizing a home-like environment.

Moreover, the culturechangemovementin LTCFs,

based on the philosophy of person-centered care, focuses

on well-being and quality of life as defined by the resi-

dent.However,the prevalence ofantipsychotic use in

LTCFs remains high (Fischer, Cohen, Forrest,

Schweizer,& Wasylenki,2011),mainly to address the

behavioraland psychologicalsymptomsof dementia

(BPSD) that include aggression,agitation,restlessness,

wandering,hoarding, sleep disturbances,psychosis,

delusions, hallucinations, and sundowning

(Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, & Rosenthal, 1989).

Recently,British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Health

reviewed antipsychotic use in LTCFs and recommended

its use for the treatment of BPSD under severalcondi-

tions (MoH, 2011).These conditions include weighing

the risks againstthe benefits,using those drugsas a

last resort,obtaining informed consentprior to use,

and following the clinical guidelinesof a low dose,

slow titration, and over a short period with close moni-

toring. Yet, the review illustrated that over half (50.3%)

of the residents were prescribed antipsychotics between

April 2010 and June 2011,an increase of 37% within a

decade(MoH, 2011),with similar increasesreported

across Canadian health authorities. While newly

admitted residents are more likely than other residents

to be prescribed at least one antipsychotic during the first

90 days of admission (Huybrechts,Rothman,Silliman,

Brookhart,& Schneeweiss, 2011), antipsychotic use can

be as twice ashigh in residentswith BPSD (Alanen,

Finne-Soveri,Noro, & Leinonen,2006).Antipsychotic

use in older adults,particularly with dementia,is asso-

ciated with multipleside effects(Perucca & Gilliam,

2012)such as increased risksof mortality,falls, and

hip fractures.Furthermore,antipsychotics may worsen

cognition and increase sedative load (Perucca & Gilliam,

2012) that, in turn, may reduce the level of social engage-

ment (SE).

SE is considered essentialto the psychologicaland

physicalwell-being (Bennett,2002)of older adultsin

LTCFs due to challenges within the setting in keeping

older adults active and stimulated.Scholars have pro-

posed that SE might be an alternative to antipsychotics

use (Mallidou, Oliveira, & Borycki, 2013). Socially enga-

ging residents has positive health outcomes,such as a

protectiveeffecton mortality (Bennett,2002;Kiely,

Simon,Jones,& Morris, 2000),and improved function

and cognition (Chen et al.,2013).SE is also associated

with decreased symptomsof depression (Lou,Chi,

Kwan, & Leung, 2013) and is an indicator of quality of

life, as it relates to positive emotions,sense of purpose,

and life satisfaction.Conversely,lonely older adults

often have low self-rated health and low life satisfaction.

Design and Method

Design and Sample

This is a cross-sectional study using administrative data.

Data from the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum

Data Set (RAI-MDS, Version 2.0) and the Continuing

Care Information ManagementSystem were collected

between 2008 and 2011 in the FraserHealth region,

BC, Canada (accessiblepopulation).Fraser Health

operates 7,800 residentialcare beds and has systematic-

ally collected RAI-MDS data on residents since 2007.

The RAI-MDS has been rigorously tested for reliability

and validity in Canada and internationally (Hawes et al.,

1995;Lawton etal., 1998;Mor et al., 2003),enabling

comparison between countries and institutions.Trained

clinicians complete the MDS 2.0 upon residentadmis-

sion and ideally every 3 monthsthereafter.It also is

completed ifchangesin health statusare experienced

by residents.In this study,all measureswere drawn

from assessments undertaken 90 days following admis-

sion to LTCFs.

Our initial sample included 10,763 newly admitted

residents(from January 1, 2008, to December31,

2011), aged 65 or older. The final study sample included

2,639 residents who upon admission or in their first full

or quarterly assessment had a diagnosis of dementia and

who had at least one LTC assessment within 90 days of

admission (Figure 1).

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is antipsychotic use,which was

defined as the use of atypicaland typicalantipsychotic

agent(s).It was coded into a binary variable:did not

receive antipsychotic drugs ¼ 0 and received antipsychotics

(one drug atleastonce,regardless ofthe numbers of

drugs or days the drug is received)in the past7 days

prior to the assessment date ¼ 1.

Independent Variable

The independentvariablewas SE, which within the

contextof LTCFs, was defined as those who have ‘a

high sense of initiative and involvement and can respond

adequately to socialstimuliin the socialenvironment,

participate in socialactivitiesand interactwith other

residents and staff’ (Achterberg et al.,2003, p. 213). SE

was measured using the Index ofSocial Engagement

(ISE), an observationalscale that measures the positive

social behavior of residents. It includes six dichotomous

items reflecting whether the resident is at ease interacting

with others, with planned or structured activities, doing

self-initiatedactivities,establishingtheir own goals,

pursuing involvement in facility life, and accepting invi-

tations into most group activities.The ISE has shown

2 Canadian Journalof Nursing Research 0(0)

good internalconsistency with Cronbach’sa of .72

(Lou et al., 2013) and interrater reliability with an aver-

age of k of .58 (Hawes et al.,1995).For this study,we

dichotomized the ISE scores: low level of SE with scores 0

to 3 ¼ 0 and high level with scores 4 to 6 ¼ 1.

ControlVariables

Sociodemographic (i.e., gender, age, marital status, guar-

anteed income supplement (GIS), education) and health-

related (i.e., aggression, cognition, depression, burden of

illness,delirium,and communication problems)vari-

ables were included as control variables.

Gender was binary coded with female (0) and male (1).

Age was recoded into eight 5-year age categories:65 to

69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, 85 to 89, 90 to 94, 95 to

99,100 to 104 years old.Marital status was coded into

four categories:married, separated/divorced,single/

never married, and widowed. GIS, a monthly nontaxable

benefit provided to low-income old age security recipi-

ents was coded into two categories: received GIS ¼ 1 and

did not receive GIS ¼ 0. Education was a three-level ordi-

nal variable:less than high school ¼ 0,high schoolcom-

pleted ¼ 1, and more than high school ¼ 2.

Aggressive behavior is considered the most disturbing

and distressing (verbal or physical) actions displayed by

residents in LTCFs (Voyer et al., 2005) that could harm

or threaten another person. Aggression was measured by

the Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS) based on the occur-

rence of verbalor physicalabuse,socially disruptive

behavior,and resistance to care.The ABS has shown

internal consistencywith as between.79 and .93

(Perlman & Hirdes, 2008) and concurrentvalidity.

Responseswere coded into three levels:no aggres-

sion ¼ 0,mild to moderatelevel of aggressionwith

ranges from 1 to 4 ¼ 1,and high levelof aggression with

range values of 5 or more ¼ 2.

Cognition includes ‘abilities such as use ofsymbols

and abstractions,acquiring new information, and

adapting to changing situations’(Williams & Kemper,

2010,p. 43). It was measured usingthe Cognitive

Performance Scale (CPS) that combines information on

memory impairment,levelof consciousness,and execu-

tive function.CPS has been found to provide a valid

measure ofthe cognitive statusof residentsliving in

LTCFs and has been validatedagainst the Mini-

Mental State Examination with a a coefficientof .75

(Ahn & Horgas, 2013).CPS scoresrange from 0

(intact)to 6 (very severe impairment).We recoded the

CPS scores into a binary variable:not severely impaired

with values 0 to 3 ¼ 0 and severely impaired with values 4

to 6 ¼ 1.

Depression was measured by the Depression Rating

Scale (DRS),consisting of making negative statements;

persistent anger with self or others; expression (including

nonverbal) of what appear to be unrealistic fears; repeti-

tive health complaints;repetitiveanxiouscomplaints

(nonhealth related);sad,pained,worried facialexpres-

sion; and crying and tearfulness. The DRS demonstrated

good internal consistency of .87 (Achterberg et al., 2003).

The DRS scores were rerecoded into a binary variable

based on the DRS cut-point of 3:absence of depression

(scores 4 2) ¼ 0 and presence of depression

(scores 5 3) ¼ 1 (Achterberg et al., 2003).

Burden of illness was assessedby the 9-item

Changes in Health, End-Stage Disease, and

Symptomsand Signs Scale (CHESS) that measures

instability in health and is a strong predictor ofmor-

tality (Hirdes, Frijters, & Teare, 2003),with higher

scores predictive ofadverse outcomes such as mortal-

ity, hospitalization,pain, caregiverstress,and poor

self-rated health.Six items of CHESS (vomiting,dehy-

dration,decrease in food orfluid, weightloss, short-

ness of breath,and edema) were summed ranging from

0 to 2;and three items (decline in cognition,decline in

activity of daily living-ADL,and end-stage disease) we

summed ranging from 0 (no instability) to 5 (high level

of instability).Then, we recoded the firstsix items as

no health instability ¼ 0,minimalhealth instability ¼ 1,

and low-healthinstability ¼ 2.The higher levels of

CHESS were then recoded as moderate health instabil-

ity ¼ 3,high-health instability ¼ 4,and very high health

instability ¼ 5 and were reflective ofa ‘high burden of

illness’due to the presenceof a significantlevel of

instability. For our analyses,CHESS scores were

recoded into a binary variable:low burden ofillness

19,194 residents aged ≥65 years

10,763 residents admitted between

Jan1, 2008 - Dec 31, 2011

2,936 with a diagnosis of AD or

other dementias

N= 2,639 clients with at least

one LTC assessment at least

90 days following admission

Figure 1. Participant selection process and sample.

Saleh et al. 3

(Lou et al., 2013) and interrater reliability with an aver-

age of k of .58 (Hawes et al.,1995).For this study,we

dichotomized the ISE scores: low level of SE with scores 0

to 3 ¼ 0 and high level with scores 4 to 6 ¼ 1.

ControlVariables

Sociodemographic (i.e., gender, age, marital status, guar-

anteed income supplement (GIS), education) and health-

related (i.e., aggression, cognition, depression, burden of

illness,delirium,and communication problems)vari-

ables were included as control variables.

Gender was binary coded with female (0) and male (1).

Age was recoded into eight 5-year age categories:65 to

69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, 85 to 89, 90 to 94, 95 to

99,100 to 104 years old.Marital status was coded into

four categories:married, separated/divorced,single/

never married, and widowed. GIS, a monthly nontaxable

benefit provided to low-income old age security recipi-

ents was coded into two categories: received GIS ¼ 1 and

did not receive GIS ¼ 0. Education was a three-level ordi-

nal variable:less than high school ¼ 0,high schoolcom-

pleted ¼ 1, and more than high school ¼ 2.

Aggressive behavior is considered the most disturbing

and distressing (verbal or physical) actions displayed by

residents in LTCFs (Voyer et al., 2005) that could harm

or threaten another person. Aggression was measured by

the Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS) based on the occur-

rence of verbalor physicalabuse,socially disruptive

behavior,and resistance to care.The ABS has shown

internal consistencywith as between.79 and .93

(Perlman & Hirdes, 2008) and concurrentvalidity.

Responseswere coded into three levels:no aggres-

sion ¼ 0,mild to moderatelevel of aggressionwith

ranges from 1 to 4 ¼ 1,and high levelof aggression with

range values of 5 or more ¼ 2.

Cognition includes ‘abilities such as use ofsymbols

and abstractions,acquiring new information, and

adapting to changing situations’(Williams & Kemper,

2010,p. 43). It was measured usingthe Cognitive

Performance Scale (CPS) that combines information on

memory impairment,levelof consciousness,and execu-

tive function.CPS has been found to provide a valid

measure ofthe cognitive statusof residentsliving in

LTCFs and has been validatedagainst the Mini-

Mental State Examination with a a coefficientof .75

(Ahn & Horgas, 2013).CPS scoresrange from 0

(intact)to 6 (very severe impairment).We recoded the

CPS scores into a binary variable:not severely impaired

with values 0 to 3 ¼ 0 and severely impaired with values 4

to 6 ¼ 1.

Depression was measured by the Depression Rating

Scale (DRS),consisting of making negative statements;

persistent anger with self or others; expression (including

nonverbal) of what appear to be unrealistic fears; repeti-

tive health complaints;repetitiveanxiouscomplaints

(nonhealth related);sad,pained,worried facialexpres-

sion; and crying and tearfulness. The DRS demonstrated

good internal consistency of .87 (Achterberg et al., 2003).

The DRS scores were rerecoded into a binary variable

based on the DRS cut-point of 3:absence of depression

(scores 4 2) ¼ 0 and presence of depression

(scores 5 3) ¼ 1 (Achterberg et al., 2003).

Burden of illness was assessedby the 9-item

Changes in Health, End-Stage Disease, and

Symptomsand Signs Scale (CHESS) that measures

instability in health and is a strong predictor ofmor-

tality (Hirdes, Frijters, & Teare, 2003),with higher

scores predictive ofadverse outcomes such as mortal-

ity, hospitalization,pain, caregiverstress,and poor

self-rated health.Six items of CHESS (vomiting,dehy-

dration,decrease in food orfluid, weightloss, short-

ness of breath,and edema) were summed ranging from

0 to 2;and three items (decline in cognition,decline in

activity of daily living-ADL,and end-stage disease) we

summed ranging from 0 (no instability) to 5 (high level

of instability).Then, we recoded the firstsix items as

no health instability ¼ 0,minimalhealth instability ¼ 1,

and low-healthinstability ¼ 2.The higher levels of

CHESS were then recoded as moderate health instabil-

ity ¼ 3,high-health instability ¼ 4,and very high health

instability ¼ 5 and were reflective ofa ‘high burden of

illness’due to the presenceof a significantlevel of

instability. For our analyses,CHESS scores were

recoded into a binary variable:low burden ofillness

19,194 residents aged ≥65 years

10,763 residents admitted between

Jan1, 2008 - Dec 31, 2011

2,936 with a diagnosis of AD or

other dementias

N= 2,639 clients with at least

one LTC assessment at least

90 days following admission

Figure 1. Participant selection process and sample.

Saleh et al. 3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

in which we combined the scores of 0 to 2 and recoded

as 0 and high burdenof illnesswhich a combined

scores of3 to 5 that were recoded to 1.

Data were selected thatassessed six delirium symp-

toms: easily distracted, periods of altered perception, dis-

organized speech,periodsof restlessness,periodsof

lethargy,and mental function that varies over the

course of the day. Each symptom was scored as not pre-

sent ¼ 0,present but not of recent onset ¼ 1,and present

that appears different from usuallevelof functioning ¼ 2.

Then,following Voyer and colleagues (2008),we coded

the absence of delirium symptoms as 0) and we combined

the scores of1 and 2 and gave ita score of1, which

indicates positive presence of delirium.

Communication problemsweremeasured by three

items: making oneself understood (1 ¼ sometimes

understood; 2 ¼ rarely or never understood), speech clarity

(1 ¼ unclear speech; 2 ¼ no speech), and ability to under-

stand others (1 ¼ sometimes understand; 2 ¼ rarely or never

understands). The scores were summed into single scores,

ranging from 0 to 3, with a higher score reflecting greater

difficulty communicating with and understanding others.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS (9.2). Descriptive analysis

was completed and included cross-tabulation evaluated

with Wald 2. Variablesmeeting minimalsignificance

(p < .25)were included in the multivariateanalysis.

Covariateswere removed from the modelif they are

nonsignificantand not a confounder. Therefore,

models contained only significant covariatesand

confounders. The criterion to establish statistical signifi-

cance for the multivariate analysis was an a of .05.We

conducted logistic regression in a series of three nested

models exploring the effect of SE on antipsychotic use.

We first entered the variable SE followed by the socio-

demographic characteristics,and finally,health-related

variables.

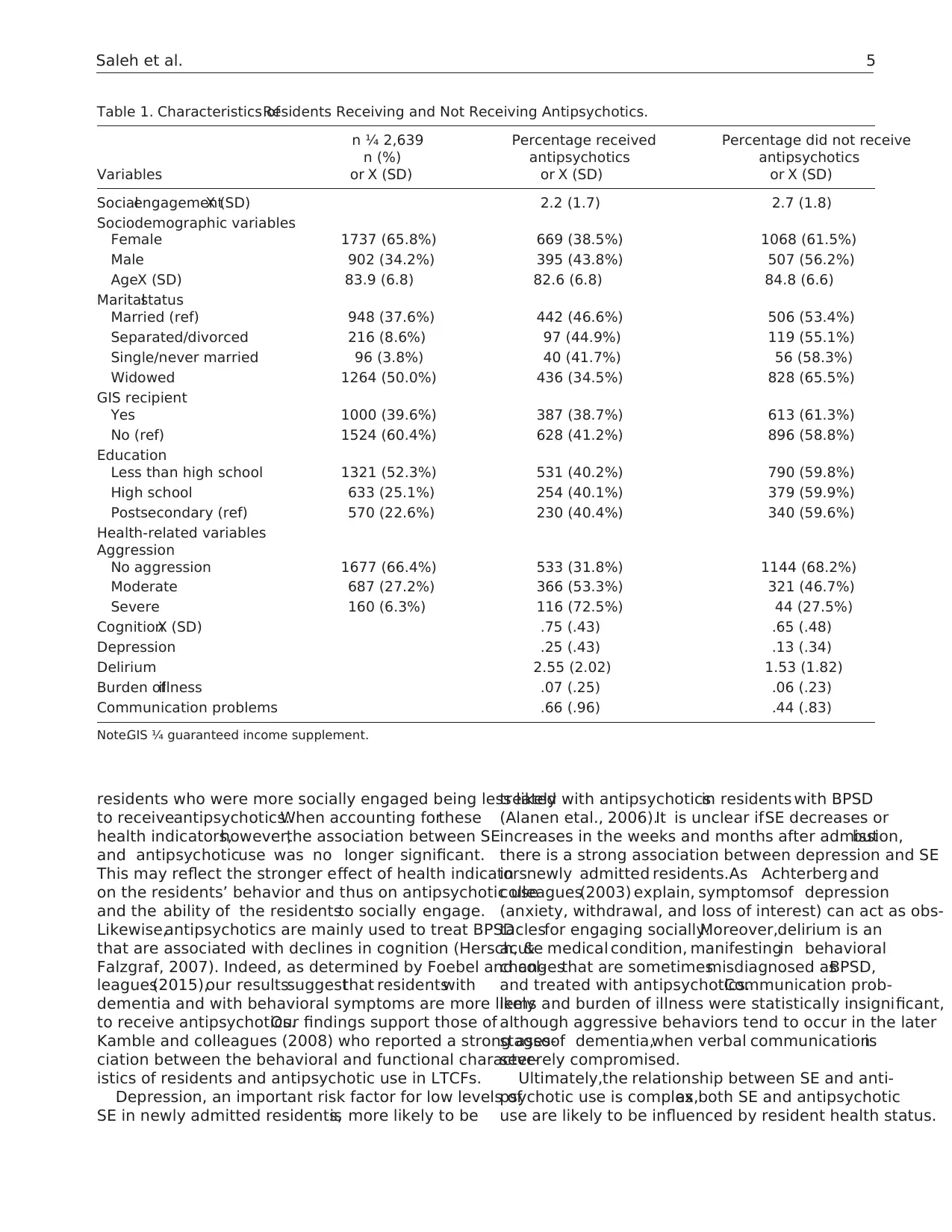

Results

The average age of the study participants was just under

84 years (Table 1).Half of the sample was widowed,

60.4% received GIS,and 52.3% had less than a high

schooleducation.Antipsychoticsreceiverswere males

(43.8%),younger (mean age ¼ 82.6 years),and married

(46.6%),GIS no-recipients(41.2%)and were mildly

aggressive(53.3%) or severelyaggressiveresidents

(72.5%). An interesting finding is that 31.8% of residents

who had no aggressive behavior received antipsychotics,

while 27.5% of participantswith severeaggressive

behaviordid not receive antipsychotics.Furthermore,

residentswho receivedantipsychoticshad a lower

mean level of SE ( X ¼ 2.2,SD ¼ 1.7),experienced

cognitiveissues(.75, SD ¼ .43),depression (X ¼ .25,

SD ¼ .43),delirium (X ¼ 2.55,SD ¼ 2.02),burden of ill-

ness (X ¼ .07,SD ¼ .25),and communication problems

(X ¼ .66, SD ¼ .96).

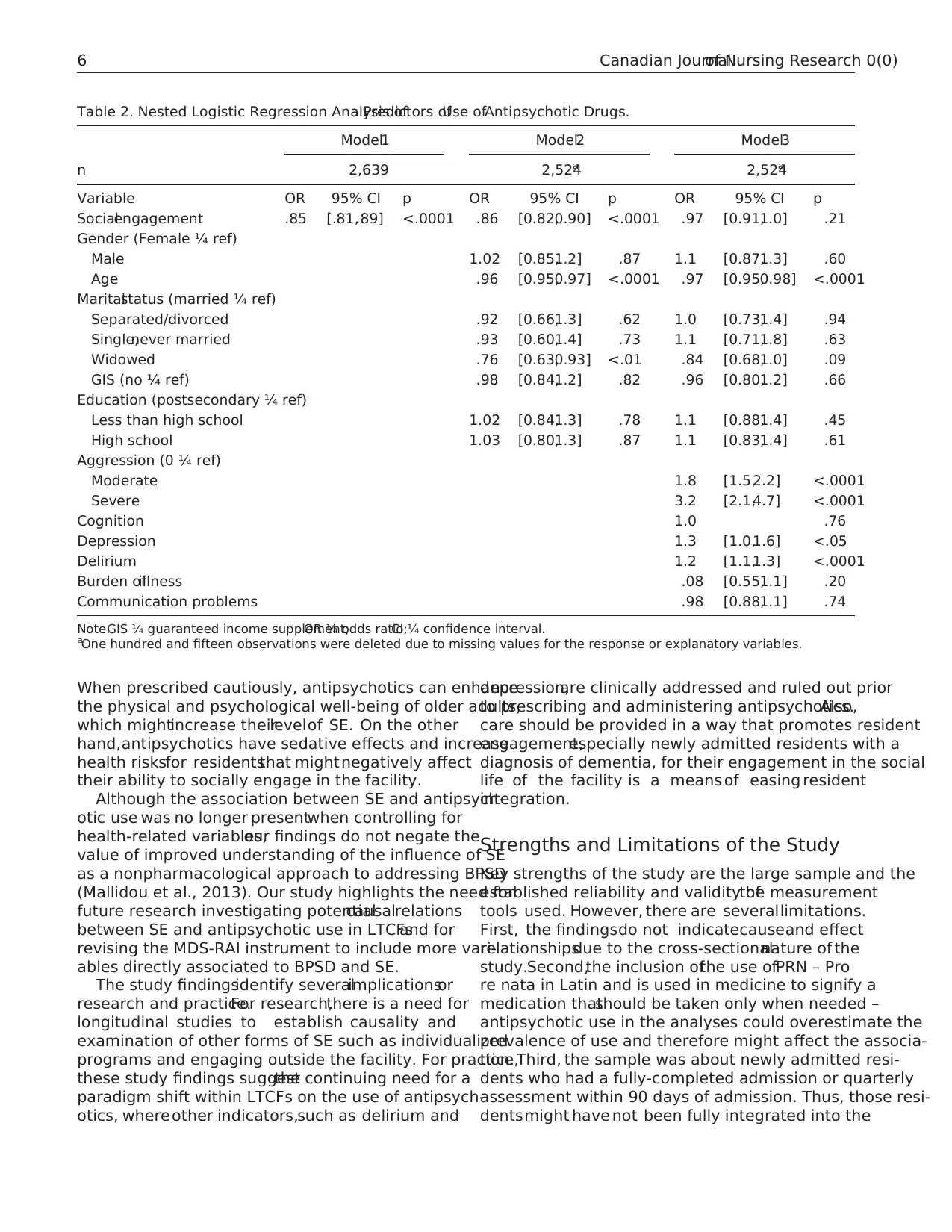

We used logistic regression analyses to predict anti-

psychotic use based on the SE level while we controlled

for sociodemographic-and health-relatedvariables

(Table 2). In both Model 1 and Model 2, a greater

levelof engagementwas associated with a lower level

of antipsychotic use (odds ratio (OR) ¼ .85,p < .0001,

confidenceinterval(CI) [0.81,0.89])and (OR ¼ .86,

p < .0001, CI [0.82, 0.90]), respectively. In addition, find-

ings showed that older age (OR ¼ .96, p < .0001, CI [0.95,

0.97])and widowhood rather than married (OR ¼ .76,

p < .01,CI [0.63,0.93])were associated with lower

likelihood of antipsychotic use.

In Model 3, controlling for both sociodemographic-

and health-related indicators,SE and widowhood were

no longer significantly associated with antipsychotics use

(OR ¼ .97, p ¼ .21, CI [0.91, 1.0]) and (OR ¼ .84, p ¼ .09,

CI [0.68,1.0]),respectively.However,age (OR ¼ .97,

p < .0001, CI [0.95, 0.98]) and several health status indi-

cators remained statisticallysignificant predictors.

Notably, residents with moderate or severe aggressive

behavior were 1.8 times and 3.2 times more likely to

receive antipsychotics (OR ¼ 1.8,p < .0001,CI [1.5,2.2]

and OR ¼ 3.2,p < .0001,CI [2.1, 4.7]), respectively.

Furthermore,residentsdiagnosed with depression or

delirium were 1.3 times (OR ¼ 1.3, p < .05, CI [1.0, 1.6])

or 1.2 times(OR ¼ 1.2,p < .0001,CI [1.1,1.3])more

likely to receive antipsychotics, respectively.

Discussion

The aim of this study wasto explore the association

between SE and antipsychotic use in addressing BPSD

in residentsnewly admitted to LTCFs.Severalnote-

worthy factors were associated with antipsychotic use.

Consistentwith otherstudies,females(65.8% in our

sample)live longer than males and are more likely to

receive LTC services.Also, consistent with the study of

Kamble etal. (2008),the likelihood ofreceiving anti-

psychoticswas lower for femalethan maleresidents

(38.5% vs.43.8%);and as Krueger et al.(2009) found,

the percentageof residentsreceivingantipsychotics

decreased with age (the lowest percentage of those receiv-

ing antipsychotics aged 585). However, gender was not

statistically significant when controlling for other socio-

demographicfactors and health-relatedvariables.

Conversely,age remained statistically significantwhen

controlling for both sociodemographiccharacteristics

and health indicators.

Prior to the introduction of controls for factors such as

aggression,depression,and delirium,SE was found to

have an inverse association with antipsychotic use, with

4 Canadian Journalof Nursing Research 0(0)

as 0 and high burdenof illnesswhich a combined

scores of3 to 5 that were recoded to 1.

Data were selected thatassessed six delirium symp-

toms: easily distracted, periods of altered perception, dis-

organized speech,periodsof restlessness,periodsof

lethargy,and mental function that varies over the

course of the day. Each symptom was scored as not pre-

sent ¼ 0,present but not of recent onset ¼ 1,and present

that appears different from usuallevelof functioning ¼ 2.

Then,following Voyer and colleagues (2008),we coded

the absence of delirium symptoms as 0) and we combined

the scores of1 and 2 and gave ita score of1, which

indicates positive presence of delirium.

Communication problemsweremeasured by three

items: making oneself understood (1 ¼ sometimes

understood; 2 ¼ rarely or never understood), speech clarity

(1 ¼ unclear speech; 2 ¼ no speech), and ability to under-

stand others (1 ¼ sometimes understand; 2 ¼ rarely or never

understands). The scores were summed into single scores,

ranging from 0 to 3, with a higher score reflecting greater

difficulty communicating with and understanding others.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS (9.2). Descriptive analysis

was completed and included cross-tabulation evaluated

with Wald 2. Variablesmeeting minimalsignificance

(p < .25)were included in the multivariateanalysis.

Covariateswere removed from the modelif they are

nonsignificantand not a confounder. Therefore,

models contained only significant covariatesand

confounders. The criterion to establish statistical signifi-

cance for the multivariate analysis was an a of .05.We

conducted logistic regression in a series of three nested

models exploring the effect of SE on antipsychotic use.

We first entered the variable SE followed by the socio-

demographic characteristics,and finally,health-related

variables.

Results

The average age of the study participants was just under

84 years (Table 1).Half of the sample was widowed,

60.4% received GIS,and 52.3% had less than a high

schooleducation.Antipsychoticsreceiverswere males

(43.8%),younger (mean age ¼ 82.6 years),and married

(46.6%),GIS no-recipients(41.2%)and were mildly

aggressive(53.3%) or severelyaggressiveresidents

(72.5%). An interesting finding is that 31.8% of residents

who had no aggressive behavior received antipsychotics,

while 27.5% of participantswith severeaggressive

behaviordid not receive antipsychotics.Furthermore,

residentswho receivedantipsychoticshad a lower

mean level of SE ( X ¼ 2.2,SD ¼ 1.7),experienced

cognitiveissues(.75, SD ¼ .43),depression (X ¼ .25,

SD ¼ .43),delirium (X ¼ 2.55,SD ¼ 2.02),burden of ill-

ness (X ¼ .07,SD ¼ .25),and communication problems

(X ¼ .66, SD ¼ .96).

We used logistic regression analyses to predict anti-

psychotic use based on the SE level while we controlled

for sociodemographic-and health-relatedvariables

(Table 2). In both Model 1 and Model 2, a greater

levelof engagementwas associated with a lower level

of antipsychotic use (odds ratio (OR) ¼ .85,p < .0001,

confidenceinterval(CI) [0.81,0.89])and (OR ¼ .86,

p < .0001, CI [0.82, 0.90]), respectively. In addition, find-

ings showed that older age (OR ¼ .96, p < .0001, CI [0.95,

0.97])and widowhood rather than married (OR ¼ .76,

p < .01,CI [0.63,0.93])were associated with lower

likelihood of antipsychotic use.

In Model 3, controlling for both sociodemographic-

and health-related indicators,SE and widowhood were

no longer significantly associated with antipsychotics use

(OR ¼ .97, p ¼ .21, CI [0.91, 1.0]) and (OR ¼ .84, p ¼ .09,

CI [0.68,1.0]),respectively.However,age (OR ¼ .97,

p < .0001, CI [0.95, 0.98]) and several health status indi-

cators remained statisticallysignificant predictors.

Notably, residents with moderate or severe aggressive

behavior were 1.8 times and 3.2 times more likely to

receive antipsychotics (OR ¼ 1.8,p < .0001,CI [1.5,2.2]

and OR ¼ 3.2,p < .0001,CI [2.1, 4.7]), respectively.

Furthermore,residentsdiagnosed with depression or

delirium were 1.3 times (OR ¼ 1.3, p < .05, CI [1.0, 1.6])

or 1.2 times(OR ¼ 1.2,p < .0001,CI [1.1,1.3])more

likely to receive antipsychotics, respectively.

Discussion

The aim of this study wasto explore the association

between SE and antipsychotic use in addressing BPSD

in residentsnewly admitted to LTCFs.Severalnote-

worthy factors were associated with antipsychotic use.

Consistentwith otherstudies,females(65.8% in our

sample)live longer than males and are more likely to

receive LTC services.Also, consistent with the study of

Kamble etal. (2008),the likelihood ofreceiving anti-

psychoticswas lower for femalethan maleresidents

(38.5% vs.43.8%);and as Krueger et al.(2009) found,

the percentageof residentsreceivingantipsychotics

decreased with age (the lowest percentage of those receiv-

ing antipsychotics aged 585). However, gender was not

statistically significant when controlling for other socio-

demographicfactors and health-relatedvariables.

Conversely,age remained statistically significantwhen

controlling for both sociodemographiccharacteristics

and health indicators.

Prior to the introduction of controls for factors such as

aggression,depression,and delirium,SE was found to

have an inverse association with antipsychotic use, with

4 Canadian Journalof Nursing Research 0(0)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

residents who were more socially engaged being less likely

to receiveantipsychotics.When accounting forthese

health indicators,however,the association between SE

and antipsychoticuse was no longer significant.

This may reflect the stronger effect of health indicators

on the residents’ behavior and thus on antipsychotic use

and the ability of the residentsto socially engage.

Likewise,antipsychotics are mainly used to treat BPSD

that are associated with declines in cognition (Hersch, &

Falzgraf, 2007). Indeed, as determined by Foebel and col-

leagues(2015),our resultssuggestthat residentswith

dementia and with behavioral symptoms are more likely

to receive antipsychotics.Our findings support those of

Kamble and colleagues (2008) who reported a strong asso-

ciation between the behavioral and functional character-

istics of residents and antipsychotic use in LTCFs.

Depression, an important risk factor for low levels of

SE in newly admitted residents,is more likely to be

treated with antipsychoticsin residents with BPSD

(Alanen etal., 2006).It is unclear ifSE decreases or

increases in the weeks and months after admission,but

there is a strong association between depression and SE

in newly admitted residents.As Achterberg and

colleagues(2003) explain, symptomsof depression

(anxiety, withdrawal, and loss of interest) can act as obs-

taclesfor engaging socially.Moreover,delirium is an

acute medical condition, manifestingin behavioral

changesthat are sometimesmisdiagnosed asBPSD,

and treated with antipsychotics.Communication prob-

lems and burden of illness were statistically insignificant,

although aggressive behaviors tend to occur in the later

stagesof dementia,when verbal communicationis

severely compromised.

Ultimately,the relationship between SE and anti-

psychotic use is complex,as both SE and antipsychotic

use are likely to be influenced by resident health status.

Table 1. Characteristics ofResidents Receiving and Not Receiving Antipsychotics.

Variables

n ¼ 2,639

n (%)

or X (SD)

Percentage received

antipsychotics

or X (SD)

Percentage did not receive

antipsychotics

or X (SD)

SocialengagementX (SD) 2.2 (1.7) 2.7 (1.8)

Sociodemographic variables

Female 1737 (65.8%) 669 (38.5%) 1068 (61.5%)

Male 902 (34.2%) 395 (43.8%) 507 (56.2%)

AgeX (SD) 83.9 (6.8) 82.6 (6.8) 84.8 (6.6)

Maritalstatus

Married (ref) 948 (37.6%) 442 (46.6%) 506 (53.4%)

Separated/divorced 216 (8.6%) 97 (44.9%) 119 (55.1%)

Single/never married 96 (3.8%) 40 (41.7%) 56 (58.3%)

Widowed 1264 (50.0%) 436 (34.5%) 828 (65.5%)

GIS recipient

Yes 1000 (39.6%) 387 (38.7%) 613 (61.3%)

No (ref) 1524 (60.4%) 628 (41.2%) 896 (58.8%)

Education

Less than high school 1321 (52.3%) 531 (40.2%) 790 (59.8%)

High school 633 (25.1%) 254 (40.1%) 379 (59.9%)

Postsecondary (ref) 570 (22.6%) 230 (40.4%) 340 (59.6%)

Health-related variables

Aggression

No aggression 1677 (66.4%) 533 (31.8%) 1144 (68.2%)

Moderate 687 (27.2%) 366 (53.3%) 321 (46.7%)

Severe 160 (6.3%) 116 (72.5%) 44 (27.5%)

CognitionX (SD) .75 (.43) .65 (.48)

Depression .25 (.43) .13 (.34)

Delirium 2.55 (2.02) 1.53 (1.82)

Burden ofillness .07 (.25) .06 (.23)

Communication problems .66 (.96) .44 (.83)

Note.GIS ¼ guaranteed income supplement.

Saleh et al. 5

to receiveantipsychotics.When accounting forthese

health indicators,however,the association between SE

and antipsychoticuse was no longer significant.

This may reflect the stronger effect of health indicators

on the residents’ behavior and thus on antipsychotic use

and the ability of the residentsto socially engage.

Likewise,antipsychotics are mainly used to treat BPSD

that are associated with declines in cognition (Hersch, &

Falzgraf, 2007). Indeed, as determined by Foebel and col-

leagues(2015),our resultssuggestthat residentswith

dementia and with behavioral symptoms are more likely

to receive antipsychotics.Our findings support those of

Kamble and colleagues (2008) who reported a strong asso-

ciation between the behavioral and functional character-

istics of residents and antipsychotic use in LTCFs.

Depression, an important risk factor for low levels of

SE in newly admitted residents,is more likely to be

treated with antipsychoticsin residents with BPSD

(Alanen etal., 2006).It is unclear ifSE decreases or

increases in the weeks and months after admission,but

there is a strong association between depression and SE

in newly admitted residents.As Achterberg and

colleagues(2003) explain, symptomsof depression

(anxiety, withdrawal, and loss of interest) can act as obs-

taclesfor engaging socially.Moreover,delirium is an

acute medical condition, manifestingin behavioral

changesthat are sometimesmisdiagnosed asBPSD,

and treated with antipsychotics.Communication prob-

lems and burden of illness were statistically insignificant,

although aggressive behaviors tend to occur in the later

stagesof dementia,when verbal communicationis

severely compromised.

Ultimately,the relationship between SE and anti-

psychotic use is complex,as both SE and antipsychotic

use are likely to be influenced by resident health status.

Table 1. Characteristics ofResidents Receiving and Not Receiving Antipsychotics.

Variables

n ¼ 2,639

n (%)

or X (SD)

Percentage received

antipsychotics

or X (SD)

Percentage did not receive

antipsychotics

or X (SD)

SocialengagementX (SD) 2.2 (1.7) 2.7 (1.8)

Sociodemographic variables

Female 1737 (65.8%) 669 (38.5%) 1068 (61.5%)

Male 902 (34.2%) 395 (43.8%) 507 (56.2%)

AgeX (SD) 83.9 (6.8) 82.6 (6.8) 84.8 (6.6)

Maritalstatus

Married (ref) 948 (37.6%) 442 (46.6%) 506 (53.4%)

Separated/divorced 216 (8.6%) 97 (44.9%) 119 (55.1%)

Single/never married 96 (3.8%) 40 (41.7%) 56 (58.3%)

Widowed 1264 (50.0%) 436 (34.5%) 828 (65.5%)

GIS recipient

Yes 1000 (39.6%) 387 (38.7%) 613 (61.3%)

No (ref) 1524 (60.4%) 628 (41.2%) 896 (58.8%)

Education

Less than high school 1321 (52.3%) 531 (40.2%) 790 (59.8%)

High school 633 (25.1%) 254 (40.1%) 379 (59.9%)

Postsecondary (ref) 570 (22.6%) 230 (40.4%) 340 (59.6%)

Health-related variables

Aggression

No aggression 1677 (66.4%) 533 (31.8%) 1144 (68.2%)

Moderate 687 (27.2%) 366 (53.3%) 321 (46.7%)

Severe 160 (6.3%) 116 (72.5%) 44 (27.5%)

CognitionX (SD) .75 (.43) .65 (.48)

Depression .25 (.43) .13 (.34)

Delirium 2.55 (2.02) 1.53 (1.82)

Burden ofillness .07 (.25) .06 (.23)

Communication problems .66 (.96) .44 (.83)

Note.GIS ¼ guaranteed income supplement.

Saleh et al. 5

When prescribed cautiously, antipsychotics can enhance

the physical and psychological well-being of older adults,

which mightincrease theirlevelof SE. On the other

hand,antipsychotics have sedative effects and increase

health risksfor residentsthat mightnegatively affect

their ability to socially engage in the facility.

Although the association between SE and antipsych-

otic use was no longer presentwhen controlling for

health-related variables,our findings do not negate the

value of improved understanding of the influence of SE

as a nonpharmacological approach to addressing BPSD

(Mallidou et al., 2013). Our study highlights the need for

future research investigating potentialcausalrelations

between SE and antipsychotic use in LTCFsand for

revising the MDS-RAI instrument to include more vari-

ables directly associated to BPSD and SE.

The study findingsidentify severalimplicationsor

research and practice.For research,there is a need for

longitudinal studies to establish causality and

examination of other forms of SE such as individualized

programs and engaging outside the facility. For practice,

these study findings suggestthe continuing need for a

paradigm shift within LTCFs on the use of antipsych-

otics, where other indicators,such as delirium and

depression,are clinically addressed and ruled out prior

to prescribing and administering antipsychotics.Also,

care should be provided in a way that promotes resident

engagement,especially newly admitted residents with a

diagnosis of dementia, for their engagement in the social

life of the facility is a means of easing resident

integration.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Key strengths of the study are the large sample and the

established reliability and validity ofthe measurement

tools used. However, there are severallimitations.

First, the findingsdo not indicatecauseand effect

relationshipsdue to the cross-sectionalnature of the

study.Second,the inclusion ofthe use ofPRN – Pro

re nata in Latin and is used in medicine to signify a

medication thatshould be taken only when needed –

antipsychotic use in the analyses could overestimate the

prevalence of use and therefore might affect the associa-

tion. Third, the sample was about newly admitted resi-

dents who had a fully-completed admission or quarterly

assessment within 90 days of admission. Thus, those resi-

dentsmight have not been fully integrated into the

Table 2. Nested Logistic Regression Analysis ofPredictors ofUse ofAntipsychotic Drugs.

Model1 Model2 Model3

n 2,639 2,524a 2,524a

Variable OR 95% CI p OR 95% CI p OR 95% CI p

Socialengagement .85 [.81,.89] <.0001 .86 [0.82,0.90] <.0001 .97 [0.91,1.0] .21

Gender (Female ¼ ref)

Male 1.02 [0.85,1.2] .87 1.1 [0.87,1.3] .60

Age .96 [0.95,0.97] <.0001 .97 [0.95,0.98] <.0001

Maritalstatus (married ¼ ref)

Separated/divorced .92 [0.66,1.3] .62 1.0 [0.73,1.4] .94

Single,never married .93 [0.60,1.4] .73 1.1 [0.71,1.8] .63

Widowed .76 [0.63,0.93] <.01 .84 [0.68,1.0] .09

GIS (no ¼ ref) .98 [0.84,1.2] .82 .96 [0.80,1.2] .66

Education (postsecondary ¼ ref)

Less than high school 1.02 [0.84,1.3] .78 1.1 [0.88,1.4] .45

High school 1.03 [0.80,1.3] .87 1.1 [0.83,1.4] .61

Aggression (0 ¼ ref)

Moderate 1.8 [1.5,2.2] <.0001

Severe 3.2 [2.1,4.7] <.0001

Cognition 1.0 .76

Depression 1.3 [1.0,1.6] <.05

Delirium 1.2 [1.1,1.3] <.0001

Burden ofillness .08 [0.55,1.1] .20

Communication problems .98 [0.88,1.1] .74

Note.GIS ¼ guaranteed income supplement;OR ¼ odds ratio;CI ¼ confidence interval.

aOne hundred and fifteen observations were deleted due to missing values for the response or explanatory variables.

6 Canadian Journalof Nursing Research 0(0)

the physical and psychological well-being of older adults,

which mightincrease theirlevelof SE. On the other

hand,antipsychotics have sedative effects and increase

health risksfor residentsthat mightnegatively affect

their ability to socially engage in the facility.

Although the association between SE and antipsych-

otic use was no longer presentwhen controlling for

health-related variables,our findings do not negate the

value of improved understanding of the influence of SE

as a nonpharmacological approach to addressing BPSD

(Mallidou et al., 2013). Our study highlights the need for

future research investigating potentialcausalrelations

between SE and antipsychotic use in LTCFsand for

revising the MDS-RAI instrument to include more vari-

ables directly associated to BPSD and SE.

The study findingsidentify severalimplicationsor

research and practice.For research,there is a need for

longitudinal studies to establish causality and

examination of other forms of SE such as individualized

programs and engaging outside the facility. For practice,

these study findings suggestthe continuing need for a

paradigm shift within LTCFs on the use of antipsych-

otics, where other indicators,such as delirium and

depression,are clinically addressed and ruled out prior

to prescribing and administering antipsychotics.Also,

care should be provided in a way that promotes resident

engagement,especially newly admitted residents with a

diagnosis of dementia, for their engagement in the social

life of the facility is a means of easing resident

integration.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Key strengths of the study are the large sample and the

established reliability and validity ofthe measurement

tools used. However, there are severallimitations.

First, the findingsdo not indicatecauseand effect

relationshipsdue to the cross-sectionalnature of the

study.Second,the inclusion ofthe use ofPRN – Pro

re nata in Latin and is used in medicine to signify a

medication thatshould be taken only when needed –

antipsychotic use in the analyses could overestimate the

prevalence of use and therefore might affect the associa-

tion. Third, the sample was about newly admitted resi-

dents who had a fully-completed admission or quarterly

assessment within 90 days of admission. Thus, those resi-

dentsmight have not been fully integrated into the

Table 2. Nested Logistic Regression Analysis ofPredictors ofUse ofAntipsychotic Drugs.

Model1 Model2 Model3

n 2,639 2,524a 2,524a

Variable OR 95% CI p OR 95% CI p OR 95% CI p

Socialengagement .85 [.81,.89] <.0001 .86 [0.82,0.90] <.0001 .97 [0.91,1.0] .21

Gender (Female ¼ ref)

Male 1.02 [0.85,1.2] .87 1.1 [0.87,1.3] .60

Age .96 [0.95,0.97] <.0001 .97 [0.95,0.98] <.0001

Maritalstatus (married ¼ ref)

Separated/divorced .92 [0.66,1.3] .62 1.0 [0.73,1.4] .94

Single,never married .93 [0.60,1.4] .73 1.1 [0.71,1.8] .63

Widowed .76 [0.63,0.93] <.01 .84 [0.68,1.0] .09

GIS (no ¼ ref) .98 [0.84,1.2] .82 .96 [0.80,1.2] .66

Education (postsecondary ¼ ref)

Less than high school 1.02 [0.84,1.3] .78 1.1 [0.88,1.4] .45

High school 1.03 [0.80,1.3] .87 1.1 [0.83,1.4] .61

Aggression (0 ¼ ref)

Moderate 1.8 [1.5,2.2] <.0001

Severe 3.2 [2.1,4.7] <.0001

Cognition 1.0 .76

Depression 1.3 [1.0,1.6] <.05

Delirium 1.2 [1.1,1.3] <.0001

Burden ofillness .08 [0.55,1.1] .20

Communication problems .98 [0.88,1.1] .74

Note.GIS ¼ guaranteed income supplement;OR ¼ odds ratio;CI ¼ confidence interval.

aOne hundred and fifteen observations were deleted due to missing values for the response or explanatory variables.

6 Canadian Journalof Nursing Research 0(0)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

routine of the facility,thereby negatively affecting their

SE scores. Finally, the content validity of the ISE items

of ‘at ease doing self-initiated activities’ and ‘establishes

own goals’ (Gerritsen et al., 2008, p. 41) reflect resident

autonomy,which does not have a socialorientation as

expected in a scale that measures SE.

In conclusion, SE is associated with less likelihood of

antipsychotic use when controlling for sociodemographic

variables of older adults residing in LTCFs that contrib-

utes to their health status and well-being.Although SE

was no longersignificantwhen controlling forhealth

variables,we argue thatthis finding suggestsfurther

research attention to thecomplexityof SE and its

effect on other dimensions of older adults’ health.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried outin partnership with the Michael

Smith Foundation for Health Researchand the Fraser

Health Authority, Province of British Columbia. Their support

and assistance is gratefully acknowledged as is that provided by

the older adults, family members, practitioners, advocates, and

others who participated in the research.The authors would

also like to acknowledge the contributions ofRonald Kelly,

PhD; Laura Funk, PhD; Francis Lau, PhD; and Taylor

Hainstock,BA, to the larger project within which this article

was developed.

Authors’ Contributions

N. Saleh planned the study, conducted the data analyses, and

wrote the article. M. J. Penning helped to plan the study, made

the data available, reviewed the article, and helped to revise the

article.D. Cloutier made the data available and helped revise

the article. A. Mallidou reviewed the manuscript and helped to

revise the article.K. Nuernberger provided access to the data

and assistance with statisticalanalyses.D. Taylor facilitated

access to the data through Fraser Health Authority.

Authors’ Note

The interpretations expressed herein are those of the authors

and do notnecessarily representthose of the FHA or other

participants.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect

to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financialsup-

port for the research,authorship,and/or publication ofthis

article:This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes

for Health Research: Partnershipsin Health System

Improvement Grant Program (#122184) to (MJP, DC et al.).

References

Achterberg, W., Pot, A. M., Kerkstra, A., Ooms, M., Muller,

M., & Ribbe, M. (2003). The effect of depression on social

engagementin newly admitted Dutch nursing home resi-

dents. The Gerontologist, 43, 213–218.

Ahn, H., & Horgas,A. (2013).The relationship between pain

and disruptive behaviorsin nursing home residentswith

dementia. BMC geriatrics, 13(1), 1471–1476.

Alanen,H. M., Finne-Soveri,H., Noro, A., & Leinonen,E.

(2006). Use of antipsychotic medications among elderly resi-

dents in long-term institutionalcare:A three-year follow-

up. InternationalJournal of Geriatric Psychiatry,21,

288–295.

Bennett,K. M. (2002).Low levelsocialengagement as a pre-

cursor of mortality among people in later life. Age Ageing,

31, 165–168.

Canadian Nurses Association.(2013).Three strategies to help

Canada’s most vulnerable. Retrieved from https://www.cna-

aiic.ca//media/cna/files/en/pre_budget_brief_to_house_

of_commons_2013_e.pdf.

Chen,L. Y., Liu, L. K., Liu, C. L., Peng,L. N., Lin, M. H.,

Chen, L. K., . . . ;Chang, P. L. (2013). Predicting functional

decline of older men living in veteran homes by minimum

data set: Implications for disability prevention programs in

long term care settings. JAMDA, 14, 309e9–e13.

Canadian Life and Health InsuranceAssociation.(2012).

CLHIA report on long-term care policy: Improving the acces-

sibility, quality and sustainability of long-term care in Canada

long-term care. (June). Retrieved from http://www.clhia.ca/

domino/html/clhia/CLHIA_LP4W_LND_Webstation.nsf/

resources/Content_PDFs/$file/LTC_Policy_Paper.pdf.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Marx, M. S., & Rosenthal, A. S. (1989).

A description ofagitation in a nursing home.Journal of

Gerontology, 44, M77–M84.

Fischer,C. E., Cohen,C., Forrest,L., Schweizer,T. A., &

Wasylenki,D. (2011).Psychotropicmedicationuse in

Canadian long-term care patients referred for psychogeriat-

ric consultation. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 14, 73–77.

Foebel, A., Ballokova, A., Wellens, N. I., Fialova, D., Milisen,

K., Liperoti,R., & Hirdes, J. P. (2015).A retrospective,

longitudinal study of factors associated with new antipsych-

otic medication useamong recently admitted long-term

care residents.BMC Geriatrics,15. doi: 10.1186/s12877-

015-0127-8.

Gerritsen,D. L., Steverink,N., Frijters,D. H. M., Hirdes,J.

P., Ooms, M. E., & Ribbe, M. W. (2008). A Revised Index

for social engagementfor longterm care.Journal of

Gerontological Nursing, 34(4), 40–48.

Hawes, C., Morris, J. N., Phillips, C. D., Mor, V., Fries, B. E.,

& Nonemaker, S. (1995).Reliability estimatesfor the

Minimum Data Set for nursing home resident assessment

and care screening (MDS). Gerontologist, 35, 172–178.

Hersch,E. C., & Falzgraf, S. (2007).Managementof the

behavioraland psychologicalsymptomsof dementia.

Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2, 611–621.

Hirdes, J., Frijters, D., & Teare, G. (2003). The MDS CHESS

scale: A new measure to predict mortality in the institutio-

nalized elderly.Journalof the American Geriatrics Society,

51, 96–100.

Huybrechts,K. F., Rothman, K. J., Silliman, R. A.,

Brookhart, M. A., & Schneeweiss, S. (2011). Risk of death

and hospital admission for major medical events after initi-

ation of psychotropic medications in older adults admitted

Saleh et al. 7

SE scores. Finally, the content validity of the ISE items

of ‘at ease doing self-initiated activities’ and ‘establishes

own goals’ (Gerritsen et al., 2008, p. 41) reflect resident

autonomy,which does not have a socialorientation as

expected in a scale that measures SE.

In conclusion, SE is associated with less likelihood of

antipsychotic use when controlling for sociodemographic

variables of older adults residing in LTCFs that contrib-

utes to their health status and well-being.Although SE

was no longersignificantwhen controlling forhealth

variables,we argue thatthis finding suggestsfurther

research attention to thecomplexityof SE and its

effect on other dimensions of older adults’ health.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried outin partnership with the Michael

Smith Foundation for Health Researchand the Fraser

Health Authority, Province of British Columbia. Their support

and assistance is gratefully acknowledged as is that provided by

the older adults, family members, practitioners, advocates, and

others who participated in the research.The authors would

also like to acknowledge the contributions ofRonald Kelly,

PhD; Laura Funk, PhD; Francis Lau, PhD; and Taylor

Hainstock,BA, to the larger project within which this article

was developed.

Authors’ Contributions

N. Saleh planned the study, conducted the data analyses, and

wrote the article. M. J. Penning helped to plan the study, made

the data available, reviewed the article, and helped to revise the

article.D. Cloutier made the data available and helped revise

the article. A. Mallidou reviewed the manuscript and helped to

revise the article.K. Nuernberger provided access to the data

and assistance with statisticalanalyses.D. Taylor facilitated

access to the data through Fraser Health Authority.

Authors’ Note

The interpretations expressed herein are those of the authors

and do notnecessarily representthose of the FHA or other

participants.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect

to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financialsup-

port for the research,authorship,and/or publication ofthis

article:This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes

for Health Research: Partnershipsin Health System

Improvement Grant Program (#122184) to (MJP, DC et al.).

References

Achterberg, W., Pot, A. M., Kerkstra, A., Ooms, M., Muller,

M., & Ribbe, M. (2003). The effect of depression on social

engagementin newly admitted Dutch nursing home resi-

dents. The Gerontologist, 43, 213–218.

Ahn, H., & Horgas,A. (2013).The relationship between pain

and disruptive behaviorsin nursing home residentswith

dementia. BMC geriatrics, 13(1), 1471–1476.

Alanen,H. M., Finne-Soveri,H., Noro, A., & Leinonen,E.

(2006). Use of antipsychotic medications among elderly resi-

dents in long-term institutionalcare:A three-year follow-

up. InternationalJournal of Geriatric Psychiatry,21,

288–295.

Bennett,K. M. (2002).Low levelsocialengagement as a pre-

cursor of mortality among people in later life. Age Ageing,

31, 165–168.

Canadian Nurses Association.(2013).Three strategies to help

Canada’s most vulnerable. Retrieved from https://www.cna-

aiic.ca//media/cna/files/en/pre_budget_brief_to_house_

of_commons_2013_e.pdf.

Chen,L. Y., Liu, L. K., Liu, C. L., Peng,L. N., Lin, M. H.,

Chen, L. K., . . . ;Chang, P. L. (2013). Predicting functional

decline of older men living in veteran homes by minimum

data set: Implications for disability prevention programs in

long term care settings. JAMDA, 14, 309e9–e13.

Canadian Life and Health InsuranceAssociation.(2012).

CLHIA report on long-term care policy: Improving the acces-

sibility, quality and sustainability of long-term care in Canada

long-term care. (June). Retrieved from http://www.clhia.ca/

domino/html/clhia/CLHIA_LP4W_LND_Webstation.nsf/

resources/Content_PDFs/$file/LTC_Policy_Paper.pdf.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Marx, M. S., & Rosenthal, A. S. (1989).

A description ofagitation in a nursing home.Journal of

Gerontology, 44, M77–M84.

Fischer,C. E., Cohen,C., Forrest,L., Schweizer,T. A., &

Wasylenki,D. (2011).Psychotropicmedicationuse in

Canadian long-term care patients referred for psychogeriat-

ric consultation. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 14, 73–77.

Foebel, A., Ballokova, A., Wellens, N. I., Fialova, D., Milisen,

K., Liperoti,R., & Hirdes, J. P. (2015).A retrospective,

longitudinal study of factors associated with new antipsych-

otic medication useamong recently admitted long-term

care residents.BMC Geriatrics,15. doi: 10.1186/s12877-

015-0127-8.

Gerritsen,D. L., Steverink,N., Frijters,D. H. M., Hirdes,J.

P., Ooms, M. E., & Ribbe, M. W. (2008). A Revised Index

for social engagementfor longterm care.Journal of

Gerontological Nursing, 34(4), 40–48.

Hawes, C., Morris, J. N., Phillips, C. D., Mor, V., Fries, B. E.,

& Nonemaker, S. (1995).Reliability estimatesfor the

Minimum Data Set for nursing home resident assessment

and care screening (MDS). Gerontologist, 35, 172–178.

Hersch,E. C., & Falzgraf, S. (2007).Managementof the

behavioraland psychologicalsymptomsof dementia.

Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2, 611–621.

Hirdes, J., Frijters, D., & Teare, G. (2003). The MDS CHESS

scale: A new measure to predict mortality in the institutio-

nalized elderly.Journalof the American Geriatrics Society,

51, 96–100.

Huybrechts,K. F., Rothman, K. J., Silliman, R. A.,

Brookhart, M. A., & Schneeweiss, S. (2011). Risk of death

and hospital admission for major medical events after initi-

ation of psychotropic medications in older adults admitted

Saleh et al. 7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

to nursing homes.Canadian MedicalAssociation Journal,

183, 411– 419.

Kamble,P., Chen,H., Sherer,J., & Aparasu,R. R. (2008).

Antipsychotic drug use among elderly nursing home resi-

dents in the United States.The AmericanJournal of

Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 6, 187–197.

Kiely, D. K., Simon,S. E., Jones, R. N., & Morris, J. N.

(2000).The protective effect of socialengagement on mor-

tality in long-term care.Journalof the American Geriatrics

Society, 48.doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02624.x.

Krueger, K. R., Wilson, R. S., Kamenetsky, J. M., Barnes, L.

L., Bienias,J. L., & Bennett,D. A. (2009).Socialengage-

ment and cognitive function in old age. Experimental Aging

Research, 35, 45–60.

Lawton, M. P., Casten, R., Parmelee, P. A., Van Haitsma, K.,

Corn, J., & Kleban, M. H. (1998). Psychometric character-

istics of the minimum data set II:Validity.Journalof the

American Geriatrics Society, 46(6), 736–744.

Lou, V. W., Chi, I., Kwan, C. W., & Leung, A. Y. (2013).

Trajectories of social engagement and depressive symptoms

among long-term care facility residents in Hong Kong. Age

Ageing, 42, 215–22.

Mallidou,A., Oliveira,N., & Borycki,E. (2013).Behavioural

and psychologicalsymptoms ofdementia:Are there any

effective alternative-to-antipsychoticsstrategies? OA

Family Medicine, 1, 1–6.

Ministry of Health. (2011). A review of the use of antipsychotic drugs

in British Columbia ResidentialCare Facilities (December).

Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publica-

tions/year/2011/use-of-antipsychotic-drugs.pdf.

Mor, V., Angelelli, J., Jones, R., Roy, J., Moore, T., & Morris,

J. (2003). Inter-rater reliability of nursing home quality indi-

cators in the U.S.BMC Health Services Research,3(20).

doi:10.1186/1472-6963-3-20.

Perlman, C. M., & Hirdes, J. P. (2008). The aggressive behavior

scale: A new scale to measure aggression based on the min-

imum data set.Journalof the American Geriatrics Society,

56, 2298–2303.

Perucca,P., & Gilliam, F. G. (2012).Adverseeffectsof

antiepilepticdrugs.The LancetNeurology,11, 792–802.

Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(12)

70153-9.

Voyer, P., Richard, S., Doucet, L., Danjou, C., & Carmichael,

P. H. (2008).Detection of delirium by nurses among long-

term care residentswith dementia.BMC Nursing, 7.

doi:10.1186/1472-6955-7-4.

Voyer, P., Verreault,R., Azizah, G. M., Desrosiers,J.,

Champoux, N., & Be´dard, A. (2005). Prevalence of physical

and verbalaggressivebehavioursand associated factors

among older adults in long-term care facilities.BMC geri-

atrics, 5.doi:10.1186/1471-2318-5-13.

Williams, K. N., & Kemper, S. (2011). Exploring interventions

to reduce cognitive decline in aging. Journal of Psychosocial

Nursing and Mental Health Services, 48, 42–51.

Author Biographies

Nasrin Saleh is a PhD student in the Nursing program,

University of Victoria.Her main research interest is in

the area of older adults living in long-term care facilities

and the role of socialengagementin improving their

quality of life.

Margaret Penningis a professorof Sociology and

research affiliate in the Institute on Aging and Lifelong

Health at the University of Victoria in British Columbia,

Canada. Her research interests include aging, health and

health care with a focus on issues of family life,social

support,caregiving and care receiving,health-care sys-

tems, and health services use.

DeniseCloutieris a professorin the Departmentof

Geography and a research affiliate with the Institute on

Aging and Lifelong Health at the University of Victoria.

As a health and social geographer, she studies models of

health service delivery and the continuum ofcare for

older adults.Her research has focused on the care of

populationswho are living in rural environments,

socially isolated,stroke affected,at the end of life,and

clients of home care and institutional long-term care. In

conducting community-based and collaborative

research, she employs mixed methods, both quantitative

and qualitative.This work has been funded by the

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Social Sciences

and Humanities Research Councilof Canada,Michael

Smith Foundation for Health Research,and World

Health Organization.She has published her research in

leading interdisciplinary and geographical journals such

as the Journal of Gerontology,The Gerontologist,

Progressin Human Geography,Social and Cultural

Geography,Health and Place,and SocialSciences and

Medicine.

Anastasia Mallidou is an assistant professor,Schoolof

Nursing and research affiliate of the Institute on Aging

and Lifelong Health at the University of Victoria,

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. She is also research

affiliateof the Fraser Health Authority, Vancouver,

British Columbia. Her research interests include applied

health services research (e.g.,impactof work environ-

ment/context on safety practices, organizational culture),

leadership and managementin health organizations,

knowledgetranslation (KT) and utilization, healthy

aging,and health policy uptake.Dr Mallidou currently

works on optimizing residential care facilities to improve

quality of care, and quality of life and well-being of older

adults using applied arts (i.e., individualized music, dan-

cing,and theater),and in severalknowledge syntheses

studies on knowledge translation,evidence-based prac-

tice (EBP) issues, and patient-oriented research.

Kim Nuernbergeris a program consultantfor the

Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI)

Western Office.Kim has more than 10 years of experi-

ence as a health data analyst,much of it working with

large administrativehealth data sets.Her experience

spans a broad range ofhealth service issues covering

8 Canadian Journalof Nursing Research 0(0)

183, 411– 419.

Kamble,P., Chen,H., Sherer,J., & Aparasu,R. R. (2008).

Antipsychotic drug use among elderly nursing home resi-

dents in the United States.The AmericanJournal of

Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 6, 187–197.

Kiely, D. K., Simon,S. E., Jones, R. N., & Morris, J. N.

(2000).The protective effect of socialengagement on mor-

tality in long-term care.Journalof the American Geriatrics

Society, 48.doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02624.x.

Krueger, K. R., Wilson, R. S., Kamenetsky, J. M., Barnes, L.

L., Bienias,J. L., & Bennett,D. A. (2009).Socialengage-

ment and cognitive function in old age. Experimental Aging

Research, 35, 45–60.

Lawton, M. P., Casten, R., Parmelee, P. A., Van Haitsma, K.,

Corn, J., & Kleban, M. H. (1998). Psychometric character-

istics of the minimum data set II:Validity.Journalof the

American Geriatrics Society, 46(6), 736–744.

Lou, V. W., Chi, I., Kwan, C. W., & Leung, A. Y. (2013).

Trajectories of social engagement and depressive symptoms

among long-term care facility residents in Hong Kong. Age

Ageing, 42, 215–22.

Mallidou,A., Oliveira,N., & Borycki,E. (2013).Behavioural

and psychologicalsymptoms ofdementia:Are there any

effective alternative-to-antipsychoticsstrategies? OA

Family Medicine, 1, 1–6.

Ministry of Health. (2011). A review of the use of antipsychotic drugs

in British Columbia ResidentialCare Facilities (December).

Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publica-

tions/year/2011/use-of-antipsychotic-drugs.pdf.

Mor, V., Angelelli, J., Jones, R., Roy, J., Moore, T., & Morris,

J. (2003). Inter-rater reliability of nursing home quality indi-

cators in the U.S.BMC Health Services Research,3(20).

doi:10.1186/1472-6963-3-20.

Perlman, C. M., & Hirdes, J. P. (2008). The aggressive behavior