Social Engagement and Antipsychotic Use in Addressing the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Long-Term Care Facilities

Added on 2023-06-09

9 Pages7533 Words133 Views

Original Research Report

Social Engagement and Antipsychotic

Use in Addressing the Behavioral and

Psychological Symptoms of Dementia

in Long-Term Care Facilities

Nasrin Saleh 1

, Margaret Penning 2 , Denise Cloutier 3

,

Anastasia Mallidou 1 , Kim Nuernberger4 , and Deanne Taylor 5

Abstract

Objectives: The use of antipsychotics, mainly to address the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD),

remains a common and frequent practice in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) despite their associated risks. The objective of

this study was to explore the association between social engagement (SE) and the use of antipsychotics in addressing the

BPSD in newly admitted residents to LTCFs.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was undertaken using administrative data, primarily the Resident Assessment Instrument

Minimum Data Set (Version 2.0) that collected between 2008 and 2011 (Fraser Health region, British Columbia, Canada). The

data analysis conducted on a sample of 2,639 newly admitted residents aged 65 or older with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s

disease or other dementias as of their first full or first quarterly assessment. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were

undertaken to predict antipsychotic use based on SE.

Results: SE was found to be a statistically significant predictor of antipsychotic use when controlling for sociodemographic

variables (odds ratio (OR) ¼ .86, p < .0001, confidence interval (CI) [0.82, 0.90]). However, the association disappeared when

controlling for health variables (OR ¼ .97, p ¼ .21, CI [0.97, 1.0]).

Conclusion: The prediction of antipsychotic use in newly admitted residents to LTCFs by SE is complex. Further research is

warranted for further examination of the association of antipsychotic use in newly admitted residents to LTCFs.

Keywords

long-term care facilities, residential care, social engagement, antipsychotics

Background

Demand on long-term care facilities (LTCFs) in Canada

is increasing due to the rise of life expectancy and the

number of persons with dementia. In 2011, 5 million

Canadians were 65 years of age or older, which is

expected to double by the year 2036 (Canadian Nurses

Association, 2013). Almost one million Canadians will

be living with dementia by the year 2036 compared to

450,000 in 2012 (Canadian Life and Health Insurance

Association, 2012). This is presenting major challenges

to policy makers and the health-care system and requir-

ing a shift of priorities, adapting innovative approaches

to keep older adults healthy and independent.

1 School of Nursing, University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

2 Department of Sociology and Institute on Aging and Lifelong Health,

University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

3 Department of Geography and Institute on Aging and Lifelong Health,

University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

4 British Columbia Trajectories in Care Project, University of Victoria,

British Columbia, Canada

5 Research and Knowledge Translation, Interior Health Authority, Research

Affiliate, Fraser Health Authority, British Columbia, Canada

Corresponding Author:

Nasrin Saleh, School of Nursing, University of Victoria, 2833 Dufferin

Avenue, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V8R 3L6.

Email: nasrin@uvic.ca

Canadian Journal of Nursing Research

0(0): 1–9

! The Author(s) 2017

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0844562117726253

journals.sagepub.com/home/cjn

Social Engagement and Antipsychotic

Use in Addressing the Behavioral and

Psychological Symptoms of Dementia

in Long-Term Care Facilities

Nasrin Saleh 1

, Margaret Penning 2 , Denise Cloutier 3

,

Anastasia Mallidou 1 , Kim Nuernberger4 , and Deanne Taylor 5

Abstract

Objectives: The use of antipsychotics, mainly to address the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD),

remains a common and frequent practice in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) despite their associated risks. The objective of

this study was to explore the association between social engagement (SE) and the use of antipsychotics in addressing the

BPSD in newly admitted residents to LTCFs.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was undertaken using administrative data, primarily the Resident Assessment Instrument

Minimum Data Set (Version 2.0) that collected between 2008 and 2011 (Fraser Health region, British Columbia, Canada). The

data analysis conducted on a sample of 2,639 newly admitted residents aged 65 or older with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s

disease or other dementias as of their first full or first quarterly assessment. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were

undertaken to predict antipsychotic use based on SE.

Results: SE was found to be a statistically significant predictor of antipsychotic use when controlling for sociodemographic

variables (odds ratio (OR) ¼ .86, p < .0001, confidence interval (CI) [0.82, 0.90]). However, the association disappeared when

controlling for health variables (OR ¼ .97, p ¼ .21, CI [0.97, 1.0]).

Conclusion: The prediction of antipsychotic use in newly admitted residents to LTCFs by SE is complex. Further research is

warranted for further examination of the association of antipsychotic use in newly admitted residents to LTCFs.

Keywords

long-term care facilities, residential care, social engagement, antipsychotics

Background

Demand on long-term care facilities (LTCFs) in Canada

is increasing due to the rise of life expectancy and the

number of persons with dementia. In 2011, 5 million

Canadians were 65 years of age or older, which is

expected to double by the year 2036 (Canadian Nurses

Association, 2013). Almost one million Canadians will

be living with dementia by the year 2036 compared to

450,000 in 2012 (Canadian Life and Health Insurance

Association, 2012). This is presenting major challenges

to policy makers and the health-care system and requir-

ing a shift of priorities, adapting innovative approaches

to keep older adults healthy and independent.

1 School of Nursing, University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

2 Department of Sociology and Institute on Aging and Lifelong Health,

University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

3 Department of Geography and Institute on Aging and Lifelong Health,

University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

4 British Columbia Trajectories in Care Project, University of Victoria,

British Columbia, Canada

5 Research and Knowledge Translation, Interior Health Authority, Research

Affiliate, Fraser Health Authority, British Columbia, Canada

Corresponding Author:

Nasrin Saleh, School of Nursing, University of Victoria, 2833 Dufferin

Avenue, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V8R 3L6.

Email: nasrin@uvic.ca

Canadian Journal of Nursing Research

0(0): 1–9

! The Author(s) 2017

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0844562117726253

journals.sagepub.com/home/cjn

Since the early 1990s, LTCFs have moved from a

medical model focusing on treatment toward a social

model of care emphasizing a home-like environment.

Moreover, the culture change movement in LTCFs,

based on the philosophy of person-centered care, focuses

on well-being and quality of life as defined by the resi-

dent. However, the prevalence of antipsychotic use in

LTCFs remains high (Fischer, Cohen, Forrest,

Schweizer, & Wasylenki, 2011), mainly to address the

behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia

(BPSD) that include aggression, agitation, restlessness,

wandering, hoarding, sleep disturbances, psychosis,

delusions, hallucinations, and sundowning

(Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, & Rosenthal, 1989).

Recently, British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Health

reviewed antipsychotic use in LTCFs and recommended

its use for the treatment of BPSD under several condi-

tions (MoH, 2011). These conditions include weighing

the risks against the benefits, using those drugs as a

last resort, obtaining informed consent prior to use,

and following the clinical guidelines of a low dose,

slow titration, and over a short period with close moni-

toring. Yet, the review illustrated that over half (50.3%)

of the residents were prescribed antipsychotics between

April 2010 and June 2011, an increase of 37% within a

decade (MoH, 2011), with similar increases reported

across Canadian health authorities. While newly

admitted residents are more likely than other residents

to be prescribed at least one antipsychotic during the first

90 days of admission (Huybrechts, Rothman, Silliman,

Brookhart, & Schneeweiss, 2011), antipsychotic use can

be as twice as high in residents with BPSD (Alanen,

Finne-Soveri, Noro, & Leinonen, 2006). Antipsychotic

use in older adults, particularly with dementia, is asso-

ciated with multiple side effects (Perucca & Gilliam,

2012) such as increased risks of mortality, falls, and

hip fractures. Furthermore, antipsychotics may worsen

cognition and increase sedative load (Perucca & Gilliam,

2012) that, in turn, may reduce the level of social engage-

ment (SE).

SE is considered essential to the psychological and

physical well-being (Bennett, 2002) of older adults in

LTCFs due to challenges within the setting in keeping

older adults active and stimulated. Scholars have pro-

posed that SE might be an alternative to antipsychotics

use (Mallidou, Oliveira, & Borycki, 2013). Socially enga-

ging residents has positive health outcomes, such as a

protective effect on mortality (Bennett, 2002; Kiely,

Simon, Jones, & Morris, 2000), and improved function

and cognition (Chen et al., 2013). SE is also associated

with decreased symptoms of depression (Lou, Chi,

Kwan, & Leung, 2013) and is an indicator of quality of

life, as it relates to positive emotions, sense of purpose,

and life satisfaction. Conversely, lonely older adults

often have low self-rated health and low life satisfaction.

Design and Method

Design and Sample

This is a cross-sectional study using administrative data.

Data from the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum

Data Set (RAI-MDS, Version 2.0) and the Continuing

Care Information Management System were collected

between 2008 and 2011 in the Fraser Health region,

BC, Canada (accessible population). Fraser Health

operates 7,800 residential care beds and has systematic-

ally collected RAI-MDS data on residents since 2007.

The RAI-MDS has been rigorously tested for reliability

and validity in Canada and internationally (Hawes et al.,

1995; Lawton et al., 1998; Mor et al., 2003), enabling

comparison between countries and institutions. Trained

clinicians complete the MDS 2.0 upon resident admis-

sion and ideally every 3 months thereafter. It also is

completed if changes in health status are experienced

by residents. In this study, all measures were drawn

from assessments undertaken 90 days following admis-

sion to LTCFs.

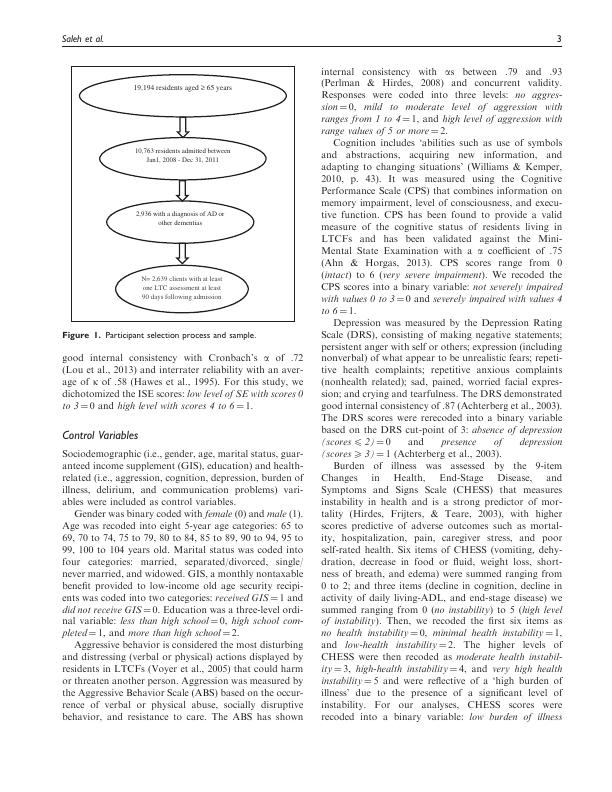

Our initial sample included 10,763 newly admitted

residents (from January 1, 2008, to December 31,

2011), aged 65 or older. The final study sample included

2,639 residents who upon admission or in their first full

or quarterly assessment had a diagnosis of dementia and

who had at least one LTC assessment within 90 days of

admission (Figure 1).

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is antipsychotic use, which was

defined as the use of atypical and typical antipsychotic

agent(s). It was coded into a binary variable: did not

receive antipsychotic drugs ¼ 0 and received antipsychotics

(one drug at least once, regardless of the numbers of

drugs or days the drug is received) in the past 7 days

prior to the assessment date ¼ 1.

Independent Variable

The independent variable was SE, which within the

context of LTCFs, was defined as those who have ‘a

high sense of initiative and involvement and can respond

adequately to social stimuli in the social environment,

participate in social activities and interact with other

residents and staff’ (Achterberg et al., 2003, p. 213). SE

was measured using the Index of Social Engagement

(ISE), an observational scale that measures the positive

social behavior of residents. It includes six dichotomous

items reflecting whether the resident is at ease interacting

with others, with planned or structured activities, doing

self-initiated activities, establishing their own goals,

pursuing involvement in facility life, and accepting invi-

tations into most group activities. The ISE has shown

2 Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 0(0)

medical model focusing on treatment toward a social

model of care emphasizing a home-like environment.

Moreover, the culture change movement in LTCFs,

based on the philosophy of person-centered care, focuses

on well-being and quality of life as defined by the resi-

dent. However, the prevalence of antipsychotic use in

LTCFs remains high (Fischer, Cohen, Forrest,

Schweizer, & Wasylenki, 2011), mainly to address the

behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia

(BPSD) that include aggression, agitation, restlessness,

wandering, hoarding, sleep disturbances, psychosis,

delusions, hallucinations, and sundowning

(Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, & Rosenthal, 1989).

Recently, British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Health

reviewed antipsychotic use in LTCFs and recommended

its use for the treatment of BPSD under several condi-

tions (MoH, 2011). These conditions include weighing

the risks against the benefits, using those drugs as a

last resort, obtaining informed consent prior to use,

and following the clinical guidelines of a low dose,

slow titration, and over a short period with close moni-

toring. Yet, the review illustrated that over half (50.3%)

of the residents were prescribed antipsychotics between

April 2010 and June 2011, an increase of 37% within a

decade (MoH, 2011), with similar increases reported

across Canadian health authorities. While newly

admitted residents are more likely than other residents

to be prescribed at least one antipsychotic during the first

90 days of admission (Huybrechts, Rothman, Silliman,

Brookhart, & Schneeweiss, 2011), antipsychotic use can

be as twice as high in residents with BPSD (Alanen,

Finne-Soveri, Noro, & Leinonen, 2006). Antipsychotic

use in older adults, particularly with dementia, is asso-

ciated with multiple side effects (Perucca & Gilliam,

2012) such as increased risks of mortality, falls, and

hip fractures. Furthermore, antipsychotics may worsen

cognition and increase sedative load (Perucca & Gilliam,

2012) that, in turn, may reduce the level of social engage-

ment (SE).

SE is considered essential to the psychological and

physical well-being (Bennett, 2002) of older adults in

LTCFs due to challenges within the setting in keeping

older adults active and stimulated. Scholars have pro-

posed that SE might be an alternative to antipsychotics

use (Mallidou, Oliveira, & Borycki, 2013). Socially enga-

ging residents has positive health outcomes, such as a

protective effect on mortality (Bennett, 2002; Kiely,

Simon, Jones, & Morris, 2000), and improved function

and cognition (Chen et al., 2013). SE is also associated

with decreased symptoms of depression (Lou, Chi,

Kwan, & Leung, 2013) and is an indicator of quality of

life, as it relates to positive emotions, sense of purpose,

and life satisfaction. Conversely, lonely older adults

often have low self-rated health and low life satisfaction.

Design and Method

Design and Sample

This is a cross-sectional study using administrative data.

Data from the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum

Data Set (RAI-MDS, Version 2.0) and the Continuing

Care Information Management System were collected

between 2008 and 2011 in the Fraser Health region,

BC, Canada (accessible population). Fraser Health

operates 7,800 residential care beds and has systematic-

ally collected RAI-MDS data on residents since 2007.

The RAI-MDS has been rigorously tested for reliability

and validity in Canada and internationally (Hawes et al.,

1995; Lawton et al., 1998; Mor et al., 2003), enabling

comparison between countries and institutions. Trained

clinicians complete the MDS 2.0 upon resident admis-

sion and ideally every 3 months thereafter. It also is

completed if changes in health status are experienced

by residents. In this study, all measures were drawn

from assessments undertaken 90 days following admis-

sion to LTCFs.

Our initial sample included 10,763 newly admitted

residents (from January 1, 2008, to December 31,

2011), aged 65 or older. The final study sample included

2,639 residents who upon admission or in their first full

or quarterly assessment had a diagnosis of dementia and

who had at least one LTC assessment within 90 days of

admission (Figure 1).

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is antipsychotic use, which was

defined as the use of atypical and typical antipsychotic

agent(s). It was coded into a binary variable: did not

receive antipsychotic drugs ¼ 0 and received antipsychotics

(one drug at least once, regardless of the numbers of

drugs or days the drug is received) in the past 7 days

prior to the assessment date ¼ 1.

Independent Variable

The independent variable was SE, which within the

context of LTCFs, was defined as those who have ‘a

high sense of initiative and involvement and can respond

adequately to social stimuli in the social environment,

participate in social activities and interact with other

residents and staff’ (Achterberg et al., 2003, p. 213). SE

was measured using the Index of Social Engagement

(ISE), an observational scale that measures the positive

social behavior of residents. It includes six dichotomous

items reflecting whether the resident is at ease interacting

with others, with planned or structured activities, doing

self-initiated activities, establishing their own goals,

pursuing involvement in facility life, and accepting invi-

tations into most group activities. The ISE has shown

2 Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 0(0)

good internal consistency with Cronbach’s a of .72

(Lou et al., 2013) and interrater reliability with an aver-

age of k of .58 (Hawes et al., 1995). For this study, we

dichotomized the ISE scores: low level of SE with scores 0

to 3 ¼ 0 and high level with scores 4 to 6 ¼ 1.

Control Variables

Sociodemographic (i.e., gender, age, marital status, guar-

anteed income supplement (GIS), education) and health-

related (i.e., aggression, cognition, depression, burden of

illness, delirium, and communication problems) vari-

ables were included as control variables.

Gender was binary coded with female (0) and male (1).

Age was recoded into eight 5-year age categories: 65 to

69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, 85 to 89, 90 to 94, 95 to

99, 100 to 104 years old. Marital status was coded into

four categories: married, separated/divorced, single/

never married, and widowed. GIS, a monthly nontaxable

benefit provided to low-income old age security recipi-

ents was coded into two categories: received GIS ¼ 1 and

did not receive GIS ¼ 0. Education was a three-level ordi-

nal variable: less than high school ¼ 0, high school com-

pleted ¼ 1, and more than high school ¼ 2.

Aggressive behavior is considered the most disturbing

and distressing (verbal or physical) actions displayed by

residents in LTCFs (Voyer et al., 2005) that could harm

or threaten another person. Aggression was measured by

the Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS) based on the occur-

rence of verbal or physical abuse, socially disruptive

behavior, and resistance to care. The ABS has shown

internal consistency with as between .79 and .93

(Perlman & Hirdes, 2008) and concurrent validity.

Responses were coded into three levels: no aggres-

sion ¼ 0, mild to moderate level of aggression with

ranges from 1 to 4 ¼ 1, and high level of aggression with

range values of 5 or more ¼ 2.

Cognition includes ‘abilities such as use of symbols

and abstractions, acquiring new information, and

adapting to changing situations’ (Williams & Kemper,

2010, p. 43). It was measured using the Cognitive

Performance Scale (CPS) that combines information on

memory impairment, level of consciousness, and execu-

tive function. CPS has been found to provide a valid

measure of the cognitive status of residents living in

LTCFs and has been validated against the Mini-

Mental State Examination with a a coefficient of .75

(Ahn & Horgas, 2013). CPS scores range from 0

(intact) to 6 (very severe impairment). We recoded the

CPS scores into a binary variable: not severely impaired

with values 0 to 3 ¼ 0 and severely impaired with values 4

to 6 ¼ 1.

Depression was measured by the Depression Rating

Scale (DRS), consisting of making negative statements;

persistent anger with self or others; expression (including

nonverbal) of what appear to be unrealistic fears; repeti-

tive health complaints; repetitive anxious complaints

(nonhealth related); sad, pained, worried facial expres-

sion; and crying and tearfulness. The DRS demonstrated

good internal consistency of .87 (Achterberg et al., 2003).

The DRS scores were rerecoded into a binary variable

based on the DRS cut-point of 3: absence of depression

(scores 4 2) ¼ 0 and presence of depression

(scores 5 3) ¼ 1 (Achterberg et al., 2003).

Burden of illness was assessed by the 9-item

Changes in Health, End-Stage Disease, and

Symptoms and Signs Scale (CHESS) that measures

instability in health and is a strong predictor of mor-

tality (Hirdes, Frijters, & Teare, 2003), with higher

scores predictive of adverse outcomes such as mortal-

ity, hospitalization, pain, caregiver stress, and poor

self-rated health. Six items of CHESS (vomiting, dehy-

dration, decrease in food or fluid, weight loss, short-

ness of breath, and edema) were summed ranging from

0 to 2; and three items (decline in cognition, decline in

activity of daily living-ADL, and end-stage disease) we

summed ranging from 0 (no instability) to 5 (high level

of instability). Then, we recoded the first six items as

no health instability ¼ 0, minimal health instability ¼ 1,

and low-health instability ¼ 2. The higher levels of

CHESS were then recoded as moderate health instabil-

ity ¼ 3, high-health instability ¼ 4, and very high health

instability ¼ 5 and were reflective of a ‘high burden of

illness’ due to the presence of a significant level of

instability. For our analyses, CHESS scores were

recoded into a binary variable: low burden of illness

19,194 residents aged ≥ 65 years

10,763 residents admitted between

Jan1, 2008 - Dec 31, 2011

2,936 with a diagnosis of AD or

other dementias

N= 2,639 clients with at least

one LTC assessment at least

90 days following admission

Figure 1. Participant selection process and sample.

Saleh et al. 3

(Lou et al., 2013) and interrater reliability with an aver-

age of k of .58 (Hawes et al., 1995). For this study, we

dichotomized the ISE scores: low level of SE with scores 0

to 3 ¼ 0 and high level with scores 4 to 6 ¼ 1.

Control Variables

Sociodemographic (i.e., gender, age, marital status, guar-

anteed income supplement (GIS), education) and health-

related (i.e., aggression, cognition, depression, burden of

illness, delirium, and communication problems) vari-

ables were included as control variables.

Gender was binary coded with female (0) and male (1).

Age was recoded into eight 5-year age categories: 65 to

69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, 85 to 89, 90 to 94, 95 to

99, 100 to 104 years old. Marital status was coded into

four categories: married, separated/divorced, single/

never married, and widowed. GIS, a monthly nontaxable

benefit provided to low-income old age security recipi-

ents was coded into two categories: received GIS ¼ 1 and

did not receive GIS ¼ 0. Education was a three-level ordi-

nal variable: less than high school ¼ 0, high school com-

pleted ¼ 1, and more than high school ¼ 2.

Aggressive behavior is considered the most disturbing

and distressing (verbal or physical) actions displayed by

residents in LTCFs (Voyer et al., 2005) that could harm

or threaten another person. Aggression was measured by

the Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS) based on the occur-

rence of verbal or physical abuse, socially disruptive

behavior, and resistance to care. The ABS has shown

internal consistency with as between .79 and .93

(Perlman & Hirdes, 2008) and concurrent validity.

Responses were coded into three levels: no aggres-

sion ¼ 0, mild to moderate level of aggression with

ranges from 1 to 4 ¼ 1, and high level of aggression with

range values of 5 or more ¼ 2.

Cognition includes ‘abilities such as use of symbols

and abstractions, acquiring new information, and

adapting to changing situations’ (Williams & Kemper,

2010, p. 43). It was measured using the Cognitive

Performance Scale (CPS) that combines information on

memory impairment, level of consciousness, and execu-

tive function. CPS has been found to provide a valid

measure of the cognitive status of residents living in

LTCFs and has been validated against the Mini-

Mental State Examination with a a coefficient of .75

(Ahn & Horgas, 2013). CPS scores range from 0

(intact) to 6 (very severe impairment). We recoded the

CPS scores into a binary variable: not severely impaired

with values 0 to 3 ¼ 0 and severely impaired with values 4

to 6 ¼ 1.

Depression was measured by the Depression Rating

Scale (DRS), consisting of making negative statements;

persistent anger with self or others; expression (including

nonverbal) of what appear to be unrealistic fears; repeti-

tive health complaints; repetitive anxious complaints

(nonhealth related); sad, pained, worried facial expres-

sion; and crying and tearfulness. The DRS demonstrated

good internal consistency of .87 (Achterberg et al., 2003).

The DRS scores were rerecoded into a binary variable

based on the DRS cut-point of 3: absence of depression

(scores 4 2) ¼ 0 and presence of depression

(scores 5 3) ¼ 1 (Achterberg et al., 2003).

Burden of illness was assessed by the 9-item

Changes in Health, End-Stage Disease, and

Symptoms and Signs Scale (CHESS) that measures

instability in health and is a strong predictor of mor-

tality (Hirdes, Frijters, & Teare, 2003), with higher

scores predictive of adverse outcomes such as mortal-

ity, hospitalization, pain, caregiver stress, and poor

self-rated health. Six items of CHESS (vomiting, dehy-

dration, decrease in food or fluid, weight loss, short-

ness of breath, and edema) were summed ranging from

0 to 2; and three items (decline in cognition, decline in

activity of daily living-ADL, and end-stage disease) we

summed ranging from 0 (no instability) to 5 (high level

of instability). Then, we recoded the first six items as

no health instability ¼ 0, minimal health instability ¼ 1,

and low-health instability ¼ 2. The higher levels of

CHESS were then recoded as moderate health instabil-

ity ¼ 3, high-health instability ¼ 4, and very high health

instability ¼ 5 and were reflective of a ‘high burden of

illness’ due to the presence of a significant level of

instability. For our analyses, CHESS scores were

recoded into a binary variable: low burden of illness

19,194 residents aged ≥ 65 years

10,763 residents admitted between

Jan1, 2008 - Dec 31, 2011

2,936 with a diagnosis of AD or

other dementias

N= 2,639 clients with at least

one LTC assessment at least

90 days following admission

Figure 1. Participant selection process and sample.

Saleh et al. 3

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Social Engagement and Antipsychotic Use in Addressing the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Long-Term Care Facilitieslg...

|5

|850

|468