The Social Psychology of Discrimination: Theory, Measurement and Consequences

Added on 2023-06-10

29 Pages10948 Words361 Views

84

Chapter 5

The Social Psychology of Discrimination:

Theory, Measurement and Consequences

Ananthi Al Ramiah, Miles Hewstone,

John F. Dovidio and Louis A. Penner

ocial psychologists engage with the prevalence and problems

of discrimination by studying the processes that underlie it.

Understanding when discrimination is likely to occur suggests

ways that we can overcome it. In this chapter, we begin by dis‐

cussing the ways in which social psychologists talk about dis‐

crimination and discuss its prevalence. Second, we outline some

theories underlying the phenomenon. Third, we consider the

ways in which social psychological studies have measured dis‐

crimination, discussing findings from laboratory and field stud‐

ies with explicit and implicit measures. Fourth, we consider the

systemic consequences of discrimination and their implications

for intergroup relations, social mobility and personal wellbeing.

Finally, we provide a summary and some conclusions.

Defining Discrimination

Social psychologists are careful to disentangle discrimination

from its close cousins of prejudice and stereotypes. Prejudice re‐

fers to an unjustifiable negative attitude toward a group and its

individual members. Stereotypes are beliefs about the personal

S

Chapter 5

The Social Psychology of Discrimination:

Theory, Measurement and Consequences

Ananthi Al Ramiah, Miles Hewstone,

John F. Dovidio and Louis A. Penner

ocial psychologists engage with the prevalence and problems

of discrimination by studying the processes that underlie it.

Understanding when discrimination is likely to occur suggests

ways that we can overcome it. In this chapter, we begin by dis‐

cussing the ways in which social psychologists talk about dis‐

crimination and discuss its prevalence. Second, we outline some

theories underlying the phenomenon. Third, we consider the

ways in which social psychological studies have measured dis‐

crimination, discussing findings from laboratory and field stud‐

ies with explicit and implicit measures. Fourth, we consider the

systemic consequences of discrimination and their implications

for intergroup relations, social mobility and personal wellbeing.

Finally, we provide a summary and some conclusions.

Defining Discrimination

Social psychologists are careful to disentangle discrimination

from its close cousins of prejudice and stereotypes. Prejudice re‐

fers to an unjustifiable negative attitude toward a group and its

individual members. Stereotypes are beliefs about the personal

S

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

85

attributes of a group of people, and can be over‐generalised, inac‐

curate, and resistant to change in the presence of new informa‐

tion. Discrimination refers to unjustifiable negative behaviour to‐

wards a group or its members, where behaviour is adjudged to

include both actions towards, and judgements/decisions about,

group members. Correll et al. (2010, p. 46) provide a very useful

definition of discrimination as ‘behaviour directed towards cate‐

gory members that is consequential for their outcomes and that is

directed towards them not because of any particular deserving‐

ness or reciprocity, but simply because they happen to be mem‐

bers of that category’. The notion of ‘deservingness’ is central to

the expression and experience of discrimination. It is not an ob‐

jectively defined criterion but one that has its roots in historical

and present‐day inequalities and societal norms. Perpetrators

may see their behaviours as justified by the deservingness of the

targets, while the targets themselves may disagree. Thus the be‐

haviours, which some judge to be discriminatory, will not be seen

as such by others.

The expression of discrimination can broadly be classified

into two types: overt or direct, and subtle, unconscious or auto‐

matic. Manifestations include verbal and non‐verbal hostility

(Darley and Fazio, 1980; Word et al., 1974), avoidance of contact

(Cuddy et al., 2007; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006), aggressive ap‐

proach behaviours (Cuddy, et al., 2007) and the denial of oppor‐

tunities and access or equal treatment (Bobo, 2001; Sidanius and

Pratto, 1999).

Across a range of domains, cultures and historical periods,

there are and have been systemic disparities between members

of dominant and non‐dominant groups (Sidaniuis and Pratto,

1999). For example, ethnic minorities consistently experience

worse health outcomes (Barnett and Halverson, 2001;

Underwood et al., 2004), worse school performance (Cohen et

al., 2006), and harsher treatment in the justice system

(Steffensmeier and Demuth, 2000). In both business and aca‐

85

attributes of a group of people, and can be over‐generalised, inac‐

curate, and resistant to change in the presence of new informa‐

tion. Discrimination refers to unjustifiable negative behaviour to‐

wards a group or its members, where behaviour is adjudged to

include both actions towards, and judgements/decisions about,

group members. Correll et al. (2010, p. 46) provide a very useful

definition of discrimination as ‘behaviour directed towards cate‐

gory members that is consequential for their outcomes and that is

directed towards them not because of any particular deserving‐

ness or reciprocity, but simply because they happen to be mem‐

bers of that category’. The notion of ‘deservingness’ is central to

the expression and experience of discrimination. It is not an ob‐

jectively defined criterion but one that has its roots in historical

and present‐day inequalities and societal norms. Perpetrators

may see their behaviours as justified by the deservingness of the

targets, while the targets themselves may disagree. Thus the be‐

haviours, which some judge to be discriminatory, will not be seen

as such by others.

The expression of discrimination can broadly be classified

into two types: overt or direct, and subtle, unconscious or auto‐

matic. Manifestations include verbal and non‐verbal hostility

(Darley and Fazio, 1980; Word et al., 1974), avoidance of contact

(Cuddy et al., 2007; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006), aggressive ap‐

proach behaviours (Cuddy, et al., 2007) and the denial of oppor‐

tunities and access or equal treatment (Bobo, 2001; Sidanius and

Pratto, 1999).

Across a range of domains, cultures and historical periods,

there are and have been systemic disparities between members

of dominant and non‐dominant groups (Sidaniuis and Pratto,

1999). For example, ethnic minorities consistently experience

worse health outcomes (Barnett and Halverson, 2001;

Underwood et al., 2004), worse school performance (Cohen et

al., 2006), and harsher treatment in the justice system

(Steffensmeier and Demuth, 2000). In both business and aca‐

Making Equality Count

86

demic domains, women are paid less and hold positions of lower

status than men, controlling for occupation and qualifications

(Goldman et al., 2006). In terms of the labour market, sociologi‐

cal research shows that ethnic minority applicants tend to suffer

from a phenomenon known as the ethnic penalty. Ethnic penal‐

ties are defined as the net disadvantages experienced by ethnic

minorities after controlling for their educational qualifications,

age and experience in the labour market (Heath and McMahon,

1997). While the ethnic penalty cannot be equated with dis‐

crimination, discrimination is likely to be a major factor respon‐

sible for its existence. This discrimination ranges from unequal

treatment that minority group members receive during the ap‐

plication process, and over the course of their education and so‐

cialisation, which can have grave consequences for the existence

of ‘bridging’ social networks, ‘spatial mismatch’ between labour

availability and opportunity, and differences in aspirations and

preferences (Heath and McMahon, 1997).

Theories of Discrimination

Several theories have shaped our understanding of intergroup

relations, prejudice and discrimination, and we focus on four

here: the social identity perspective, the ‘behaviours from inter‐

group affect and stereotypes’ map, aversive racism theory and

system justification theory.

As individuals living in a social context, we traverse the

continuum between our personal and collective selves. Differ‐

ent social contexts lead to the salience of particular group

memberships (Turner et al., 1987). The first theoretical frame‐

work that we outline, the social identity perspective (Tajfel and

Turner, 1979) holds that group members are motivated to pro‐

tect their self‐esteem and achieve a positive and distinct social

identity. This drive for a positive social identity can result in

discrimination, which is expressed as either direct harm to the

86

demic domains, women are paid less and hold positions of lower

status than men, controlling for occupation and qualifications

(Goldman et al., 2006). In terms of the labour market, sociologi‐

cal research shows that ethnic minority applicants tend to suffer

from a phenomenon known as the ethnic penalty. Ethnic penal‐

ties are defined as the net disadvantages experienced by ethnic

minorities after controlling for their educational qualifications,

age and experience in the labour market (Heath and McMahon,

1997). While the ethnic penalty cannot be equated with dis‐

crimination, discrimination is likely to be a major factor respon‐

sible for its existence. This discrimination ranges from unequal

treatment that minority group members receive during the ap‐

plication process, and over the course of their education and so‐

cialisation, which can have grave consequences for the existence

of ‘bridging’ social networks, ‘spatial mismatch’ between labour

availability and opportunity, and differences in aspirations and

preferences (Heath and McMahon, 1997).

Theories of Discrimination

Several theories have shaped our understanding of intergroup

relations, prejudice and discrimination, and we focus on four

here: the social identity perspective, the ‘behaviours from inter‐

group affect and stereotypes’ map, aversive racism theory and

system justification theory.

As individuals living in a social context, we traverse the

continuum between our personal and collective selves. Differ‐

ent social contexts lead to the salience of particular group

memberships (Turner et al., 1987). The first theoretical frame‐

work that we outline, the social identity perspective (Tajfel and

Turner, 1979) holds that group members are motivated to pro‐

tect their self‐esteem and achieve a positive and distinct social

identity. This drive for a positive social identity can result in

discrimination, which is expressed as either direct harm to the

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

87

outgroup, or more commonly and spontaneously, as giving

preferential treatment to the ingroup, a phenomenon known as

ingroup bias.

Going further, and illustrating the general tendency that

humans have to discriminate, the minimal group paradigm stud‐

ies (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) reveal how mere categorisation as a

group member can lead to ingroup bias, the favouring of in‐

group members over outgroup members in evaluations and allo‐

cation of resources (Turner, 1978). In the minimal group para‐

digm studies, participants are classified as belonging to arbitrary

groups (e.g. people who tend to overestimate or underestimate

the number of dots presented to them) and evaluate members of

the ingroup and outgroup, and take part in a reward allocation

task (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) between the two groups. Results

across hundreds of studies show that participants rate ingroup

members more positively, exhibit preference for ingroup mem‐

bers in allocation of resources, and want to maintain maximal

difference in allocation between ingroup and outgroup mem‐

bers, thereby giving outgroup members less than an equality

norm would require. Given the fact that group membership in

this paradigm does not involve a deeply‐held attachment and

operates within the wider context of equality norms, this ten‐

dency to discriminate is an important finding, and indicative of

the spontaneous nature of prejudice and discrimination in inter‐

group contexts (Al Ramiah et al., in press). Whereas social cate‐

gorisation is sufficient to create discriminatory treatment, often

motivated by ingroup favouritism, direct competition between

groups exacerbates this bias, typically generating responses di‐

rectly to disadvantage the outgroup, as well (Sherif et al., 1961).

Whereas social identity theory examines basic, general proc‐

esses leading to intergroup discrimination, the BIAS map (Be‐

haviours from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes; see Cuddy, et

al., 2007) offers insights into the specific ways that we discrimi‐

nate against members of particular types of groups. The BIAS

87

outgroup, or more commonly and spontaneously, as giving

preferential treatment to the ingroup, a phenomenon known as

ingroup bias.

Going further, and illustrating the general tendency that

humans have to discriminate, the minimal group paradigm stud‐

ies (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) reveal how mere categorisation as a

group member can lead to ingroup bias, the favouring of in‐

group members over outgroup members in evaluations and allo‐

cation of resources (Turner, 1978). In the minimal group para‐

digm studies, participants are classified as belonging to arbitrary

groups (e.g. people who tend to overestimate or underestimate

the number of dots presented to them) and evaluate members of

the ingroup and outgroup, and take part in a reward allocation

task (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) between the two groups. Results

across hundreds of studies show that participants rate ingroup

members more positively, exhibit preference for ingroup mem‐

bers in allocation of resources, and want to maintain maximal

difference in allocation between ingroup and outgroup mem‐

bers, thereby giving outgroup members less than an equality

norm would require. Given the fact that group membership in

this paradigm does not involve a deeply‐held attachment and

operates within the wider context of equality norms, this ten‐

dency to discriminate is an important finding, and indicative of

the spontaneous nature of prejudice and discrimination in inter‐

group contexts (Al Ramiah et al., in press). Whereas social cate‐

gorisation is sufficient to create discriminatory treatment, often

motivated by ingroup favouritism, direct competition between

groups exacerbates this bias, typically generating responses di‐

rectly to disadvantage the outgroup, as well (Sherif et al., 1961).

Whereas social identity theory examines basic, general proc‐

esses leading to intergroup discrimination, the BIAS map (Be‐

haviours from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes; see Cuddy, et

al., 2007) offers insights into the specific ways that we discrimi‐

nate against members of particular types of groups. The BIAS

Making Equality Count

88

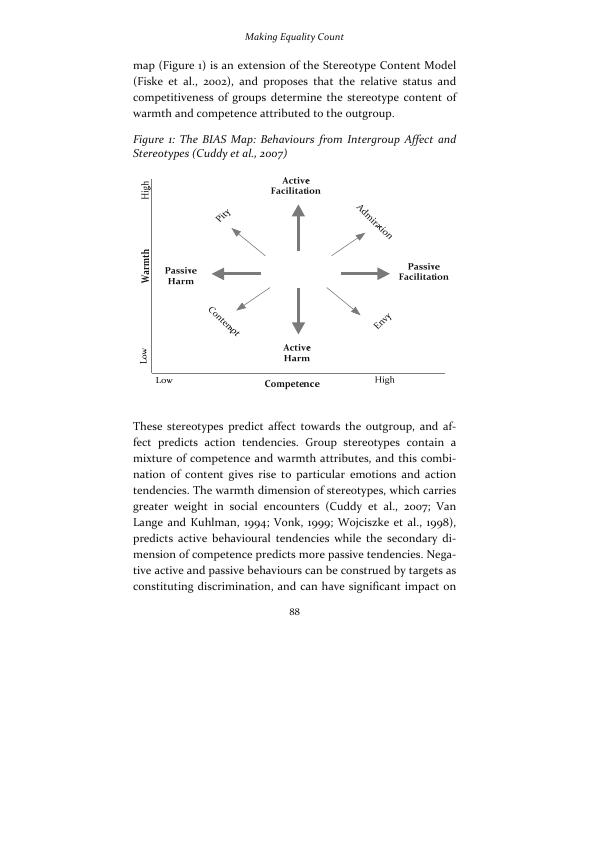

map (Figure 1) is an extension of the Stereotype Content Model

(Fiske et al., 2002), and proposes that the relative status and

competitiveness of groups determine the stereotype content of

warmth and competence attributed to the outgroup.

Figure 1: The BIAS Map: Behaviours from Intergroup Affect and

Stereotypes (Cuddy et al., 2007)

These stereotypes predict affect towards the outgroup, and af‐

fect predicts action tendencies. Group stereotypes contain a

mixture of competence and warmth attributes, and this combi‐

nation of content gives rise to particular emotions and action

tendencies. The warmth dimension of stereotypes, which carries

greater weight in social encounters (Cuddy et al., 2007; Van

Lange and Kuhlman, 1994; Vonk, 1999; Wojciszke et al., 1998),

predicts active behavioural tendencies while the secondary di‐

mension of competence predicts more passive tendencies. Nega‐

tive active and passive behaviours can be construed by targets as

constituting discrimination, and can have significant impact on

88

map (Figure 1) is an extension of the Stereotype Content Model

(Fiske et al., 2002), and proposes that the relative status and

competitiveness of groups determine the stereotype content of

warmth and competence attributed to the outgroup.

Figure 1: The BIAS Map: Behaviours from Intergroup Affect and

Stereotypes (Cuddy et al., 2007)

These stereotypes predict affect towards the outgroup, and af‐

fect predicts action tendencies. Group stereotypes contain a

mixture of competence and warmth attributes, and this combi‐

nation of content gives rise to particular emotions and action

tendencies. The warmth dimension of stereotypes, which carries

greater weight in social encounters (Cuddy et al., 2007; Van

Lange and Kuhlman, 1994; Vonk, 1999; Wojciszke et al., 1998),

predicts active behavioural tendencies while the secondary di‐

mension of competence predicts more passive tendencies. Nega‐

tive active and passive behaviours can be construed by targets as

constituting discrimination, and can have significant impact on

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

89

the quality of their lives. Examples of negative passive behav‐

iours are ignoring another’s presence, not making eye contact

with them, excluding members of certain groups from getting

opportunities, and so on, while examples of negative active be‐

haviours include supporting institutional racism or voting for

anti‐immigration political parties. These examples show that

discriminatory behaviours can range from the subtle to the

overt, and the particular views that we have about each out‐

group determines the manifestation of discrimination.

The third theory that we consider, aversive racism (Dovidio

and Gaertner, 2004) complements social identity theory (which

suggests the pervasiveness of intergroup discrimination) and the

BIAS map (which helps identify the form in which discrimina‐

tion will be manifested) by further identifying when discrimina‐

tion will be manifested or inhibited. The aversive racism frame‐

work essentially evolved to understand the psychological con‐

flict that afflicts many White Americans with regard to their ra‐

cial attitudes. Changing social norms increasingly prohibit

prejudice and discrimination towards minority and other stig‐

matised groups (Crandall et al., 2002), and work in the United

States has shown that appearing racist has become aversive to

many White Americans (Dovidio and Gaertner, 2004; Gaertner

and Dovidio, 1986; Katz and Hass, 1988; McConahay, 1986) in

terms not only of their public image but also of their private self

concept. However, a multitude of individual and societal factors

continue to reinforce stereotypes and negative evaluative biases

(which are rooted, in part, in biases identified by social identity

theory), which result in continued expression and experience of

discrimination. Equality norms give rise to considerable psycho‐

logical conflict in which people regard prejudice as unjust and

offensive, but remain unable to fully suppress their own biases.

Thus ethnic and racial attitudes have become more complex

than they were in the past.

89

the quality of their lives. Examples of negative passive behav‐

iours are ignoring another’s presence, not making eye contact

with them, excluding members of certain groups from getting

opportunities, and so on, while examples of negative active be‐

haviours include supporting institutional racism or voting for

anti‐immigration political parties. These examples show that

discriminatory behaviours can range from the subtle to the

overt, and the particular views that we have about each out‐

group determines the manifestation of discrimination.

The third theory that we consider, aversive racism (Dovidio

and Gaertner, 2004) complements social identity theory (which

suggests the pervasiveness of intergroup discrimination) and the

BIAS map (which helps identify the form in which discrimina‐

tion will be manifested) by further identifying when discrimina‐

tion will be manifested or inhibited. The aversive racism frame‐

work essentially evolved to understand the psychological con‐

flict that afflicts many White Americans with regard to their ra‐

cial attitudes. Changing social norms increasingly prohibit

prejudice and discrimination towards minority and other stig‐

matised groups (Crandall et al., 2002), and work in the United

States has shown that appearing racist has become aversive to

many White Americans (Dovidio and Gaertner, 2004; Gaertner

and Dovidio, 1986; Katz and Hass, 1988; McConahay, 1986) in

terms not only of their public image but also of their private self

concept. However, a multitude of individual and societal factors

continue to reinforce stereotypes and negative evaluative biases

(which are rooted, in part, in biases identified by social identity

theory), which result in continued expression and experience of

discrimination. Equality norms give rise to considerable psycho‐

logical conflict in which people regard prejudice as unjust and

offensive, but remain unable to fully suppress their own biases.

Thus ethnic and racial attitudes have become more complex

than they were in the past.

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Managing diversity and equality in the workplacelg...

|5

|800

|132