Societies within peace systems avoid war and build positive intergroup relationships

VerifiedAdded on 2024/06/24

|9

|9591

|403

AI Summary

This study examines the factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of peace systems, defined as clusters of neighboring societies that do not engage in war with each other. The research compares a sample of peace systems with a randomly derived comparison group of non-peace systems, analyzing eight hypothesized peace-related factors. The findings demonstrate that peace systems exhibit significantly higher levels of overarching common identity, positive social interconnectedness, interdependence, non-warring values and norms, non-warring myths, rituals, and symbols, and peace leadership compared to non-peace systems. The study also employs a machine learning technique to assess the relative importance of these factors, revealing that non-warring norms, rituals, and values are the most significant contributors to a peace system outcome. The results have policy implications for promoting and sustaining peace, cohesion, and cooperation among neighboring societies in various social contexts, including among nations.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

ARTICLE

Societies within peace systems avoid war and

positive intergroup relationships

Douglas P.Fry 1✉, Geneviève Souillac1, Larry Liebovitch2, Peter T.Coleman3, Kane Agan4,

Elliot Nicholson-Cox4, DaniMason4, Frank Palma Gomez2 & Susie Strauss4

A comparative anthropologicalperspective reveals not only that some human societies do

not engage in war,but also that peacefulsocial systems exist.Peace systems are defined as

clusters of neighbouring societies that do not make war with each other.The mere existence

of peace systems is importantbecause itdemonstrates thatcreating peacefulintergroup

relationships is possible whether the social units are tribal societies, nations, or actors within

a regionalsystem.Peace systems have received scant scientific attention despite holding

potentially useful knowledge and principles about how to successfully cooperate to keep the

peace.Thus,the mechanisms through which peace systems maintain peacefulrelationships

are largely unknown. It is also unknown to what degree peace systems may differ from other

types of socialsystems.This study shows that certain factors hypothesised to contribute to

intergroup peace are more developed within peace systems than elsewhere.A sample

consisting of peace systems scored significantly higher than a comparison group regarding

overarching common identity;positive socialinterconnectedness;interdependence;non-

warring values and norms;non-warring myths,rituals,and symbols;and peace leadership.

Additionally,a machine learning analysis found non-warring norms,rituals,and values to

have the greatest relative importance for a peace system outcome. These results have policy

implications forhow to promote and sustain peace,cohesion,and cooperation among

neighbouring societies in various socialcontexts,including among nations.For example,the

purposefulpromotion of peace system features may facilitate the internationalcooperation

necessary to address interwoven globalchallenges such as globalpandemics,oceanic pol-

lution,loss of biodiversity,nuclear proliferation,and climate change.

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 OPEN

1University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, USA.2City University of New York, New York, NY, USA.3Columbia University, New York, NY,

USA.4 University of Alabama at Birmingham,Birmingham,AL, USA. ✉email:dpfry@uncg.edu

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS |(2021) 8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 1

1234567890():,;

Societies within peace systems avoid war and

positive intergroup relationships

Douglas P.Fry 1✉, Geneviève Souillac1, Larry Liebovitch2, Peter T.Coleman3, Kane Agan4,

Elliot Nicholson-Cox4, DaniMason4, Frank Palma Gomez2 & Susie Strauss4

A comparative anthropologicalperspective reveals not only that some human societies do

not engage in war,but also that peacefulsocial systems exist.Peace systems are defined as

clusters of neighbouring societies that do not make war with each other.The mere existence

of peace systems is importantbecause itdemonstrates thatcreating peacefulintergroup

relationships is possible whether the social units are tribal societies, nations, or actors within

a regionalsystem.Peace systems have received scant scientific attention despite holding

potentially useful knowledge and principles about how to successfully cooperate to keep the

peace.Thus,the mechanisms through which peace systems maintain peacefulrelationships

are largely unknown. It is also unknown to what degree peace systems may differ from other

types of socialsystems.This study shows that certain factors hypothesised to contribute to

intergroup peace are more developed within peace systems than elsewhere.A sample

consisting of peace systems scored significantly higher than a comparison group regarding

overarching common identity;positive socialinterconnectedness;interdependence;non-

warring values and norms;non-warring myths,rituals,and symbols;and peace leadership.

Additionally,a machine learning analysis found non-warring norms,rituals,and values to

have the greatest relative importance for a peace system outcome. These results have policy

implications forhow to promote and sustain peace,cohesion,and cooperation among

neighbouring societies in various socialcontexts,including among nations.For example,the

purposefulpromotion of peace system features may facilitate the internationalcooperation

necessary to address interwoven globalchallenges such as globalpandemics,oceanic pol-

lution,loss of biodiversity,nuclear proliferation,and climate change.

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 OPEN

1University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, USA.2City University of New York, New York, NY, USA.3Columbia University, New York, NY,

USA.4 University of Alabama at Birmingham,Birmingham,AL, USA. ✉email:dpfry@uncg.edu

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS |(2021) 8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 1

1234567890():,;

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Introduction

A recurring assumption is that allsocieties engage in war

(Wilson,2001;Wright,1942).However,anthropological

data show that this is not the case (Fry,2006;Montagu,

1978; Sponsel, 2018; Souillac and Fry, 2014, 2015). In some cases,

non-warring societies are organised into peace systems, defined as

clusters of neighbouring societies that do not make war with each

other, and sometimes not at all (Fry, 2006; 2012; Souillac and Fry,

2015).An ethnographically comparative view suggests that over

time reciprocal prosocial relationships develop and link the non-

warring societies within a larger common socialsystem wherein

cooperation and unity prevailand waramong themembers

simply becomes unfathomable.For example,the Nordic Nations

have notwarred among each other for over 200 years as they

developed “the conceptof socialpeace based on a culture of

conflict resolution and societalsolidarity” (Archer,2003:p. 16).

Over time, the Nordic nations evolved a propensity for peace and

strengthened non-warring values thatfavour negotiation,coop-

eration,and the rule of law.Many times,wars could have been

fought, but were not, such as when Norway gained independence

from Sweden in 1905 without firing a shot or during a dispute

between Finland and Sweden over the Åland Islands (see Fig.1).

The Nordic nations set-up overarching institutions such as the

Nordic Council to address common concerns, and an overarching

Nordic identity emerged (Archer,2003).

We propose that gaining an understanding of how peace sys-

tems develop and how they function without war holds important

implicationsfor promoting positive,cooperativeinter-societal

relationships in a variety of other social contexts, including within

regionaland globalspheres.Compared to scientific advances in

many areas,we know surprisingly little aboutthe overarching

dynamics and principles through which human societies build

and maintain peacefulrelations.Therefore,we sought to explore

how societies operating within non-warring peace systems sustain

peace.We tested whether certain factors hypothesised to con-

tribute to intergroup peace were in fact more developed within

peace systemsthan elsewhere.The research also employed a

machine learning technique called Random Forest to assess the

relative importance of the hypothesised peace variables.Investi-

gating which processes recur across socially disparate,and geo-

graphically diverse,non-warring systems may contribute both to

basicknowledgeand to practicalapplicationsfor facilitating

peaceful relationships among societies. A scientific understan

of how societies within peace systems cooperatively and pros

cially interact in the absence ofwar has policy implications for

promotingthe collaboration necessaryto meetoverarching

challengessuch as climatechangeor pandemicswithin an

interdependent globalsystem.

Anthropology shows that peace systems can be found in dif

ferentparts ofthe world and at various levels ofsocialorgani-

sation.Anthropologicaland historicaldescriptionsof non-

warringsocialsystemsincludeAustralian Aboriginesof the

GreatWestern Desert,mobileforagersof Canada’sLabrador

Peninsula, tribes of Brazil’s Upper Xingu River basin, the Iroqu

Confederacy,the Swiss cantons that unified into Switzerland in

1848,and the United States since 1865,among others (Dennis,

1993;Fry,2006,2009,2012;Gregor,1994;Hendrickson,2003;

Parent,2011;Souillac and Fry,2015).When speaking ofpeace

systemsas lacking warfare,we are defining waras “relatively

impersonallethalaggression between communities,” a definition

of intergroup violence that applies across social types from ba

and tribes to kingdoms and nations (Fry,2006:p. 91).

A consideration of the theoreticalliterature and ethnographic

descriptionssuggeststhat variousfactorscontributeto inter-

societalpeace (Archer,2003;Cronin,1999;Fry, 2012;Nowak

et al., 2012; Parent, 2011; Rubin et al., 1994; Souillac, 2020).

are archaeologicalindicationsof peacesystemsin prehistory

(Ferguson,2013;Fry,2012;Haas,1999) and ethnographic and

historicaldescriptionsof non-warring socialsystems,but the

peacesystem concepthas only recently taken shape.Gregor

(1994) applied the term peace system to ten neighbouring tri

representing fourdifferentlanguagegroups,from theUpper

Xingu River region of Brazil wherein “the politically autonomo

tribes actsomewhatlike linguistically distinctand residentially

separate ethnic groups within a larger socialframework of com-

mon institutionsand values”(Gregor,1994:p. 244).Gregor

(1990,1994) proposed thatthe interdependentrelationships in

trade among the tribes,the patterns of intermarriage,participa-

tion in common rituals and ceremonies,and the strong anti-war

values taught to each new generation combine to keep this sy

self-sustaining.

Fry (2009,2012)expanded the peace system constructcon-

ceptually and geographically beyond the UpperXingu case by

providing descriptionsof the IroquoisConfederacy,Aboriginal

Australia,and the European Union as additionalpeace systems.

For example,prior to the formation of the Iroquois Confederacy,

the originalfive member tribes,the Seneca,Cayuga,Onondaga,

Oneida,and Mohawk,werelocked into chronicwarring and

feuding (Dennis,1993;Fenton,1998;Fry,2012).The Iroquoian

peoples developed a new overarching identity in addition to t

tribal identities, which they expressed metaphorically as five

familiesliving in harmony in the same longhouse (see Fig.2;

Fenton,1998).They expanded the tried-and-true institutions of

the village council and tribal council to create the new higher-

institution,the Councilof Chiefs,as an intertribalmechanism of

governance and conflictmanagementbased on discussion and

consensus (Dennis,1993;Fenton,1998).Peace values and norms

werereinforced bynarratives,symbols,and rituals,such as

through the legend ofthe Peacemaker bringing tranquility and

unity to the five tribes and the enactment of unifying condole

rites (Dennis,1993;Fenton,1998;Fry,2012).Are such features

generally found in peace systems?

Peace system hypotheses

We hypothesise multiple contributors to peace (Fry, 2012; No

et al.,2012;Souillac,2012;Souillac and Fry,2015).Drawing on

Fig. 1 The five Nordic Nations, Norden, have not engaged in war with one

another since 1815.A dispute between Finland and Sweden over the

strategically located Åland Islands was resolved through mediation.The

Åland Islands remain a demilitarised and neutralarea.Reproduced with

permission of Douglas P.Fry;copyright © Douglas P.Fry,all rights

reserved.

ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

2 H U M A N I T I E S A N D S O C I A L S C I E N C E S C O M M U N I C A T I O N S |(2021)8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

A recurring assumption is that allsocieties engage in war

(Wilson,2001;Wright,1942).However,anthropological

data show that this is not the case (Fry,2006;Montagu,

1978; Sponsel, 2018; Souillac and Fry, 2014, 2015). In some cases,

non-warring societies are organised into peace systems, defined as

clusters of neighbouring societies that do not make war with each

other, and sometimes not at all (Fry, 2006; 2012; Souillac and Fry,

2015).An ethnographically comparative view suggests that over

time reciprocal prosocial relationships develop and link the non-

warring societies within a larger common socialsystem wherein

cooperation and unity prevailand waramong themembers

simply becomes unfathomable.For example,the Nordic Nations

have notwarred among each other for over 200 years as they

developed “the conceptof socialpeace based on a culture of

conflict resolution and societalsolidarity” (Archer,2003:p. 16).

Over time, the Nordic nations evolved a propensity for peace and

strengthened non-warring values thatfavour negotiation,coop-

eration,and the rule of law.Many times,wars could have been

fought, but were not, such as when Norway gained independence

from Sweden in 1905 without firing a shot or during a dispute

between Finland and Sweden over the Åland Islands (see Fig.1).

The Nordic nations set-up overarching institutions such as the

Nordic Council to address common concerns, and an overarching

Nordic identity emerged (Archer,2003).

We propose that gaining an understanding of how peace sys-

tems develop and how they function without war holds important

implicationsfor promoting positive,cooperativeinter-societal

relationships in a variety of other social contexts, including within

regionaland globalspheres.Compared to scientific advances in

many areas,we know surprisingly little aboutthe overarching

dynamics and principles through which human societies build

and maintain peacefulrelations.Therefore,we sought to explore

how societies operating within non-warring peace systems sustain

peace.We tested whether certain factors hypothesised to con-

tribute to intergroup peace were in fact more developed within

peace systemsthan elsewhere.The research also employed a

machine learning technique called Random Forest to assess the

relative importance of the hypothesised peace variables.Investi-

gating which processes recur across socially disparate,and geo-

graphically diverse,non-warring systems may contribute both to

basicknowledgeand to practicalapplicationsfor facilitating

peaceful relationships among societies. A scientific understan

of how societies within peace systems cooperatively and pros

cially interact in the absence ofwar has policy implications for

promotingthe collaboration necessaryto meetoverarching

challengessuch as climatechangeor pandemicswithin an

interdependent globalsystem.

Anthropology shows that peace systems can be found in dif

ferentparts ofthe world and at various levels ofsocialorgani-

sation.Anthropologicaland historicaldescriptionsof non-

warringsocialsystemsincludeAustralian Aboriginesof the

GreatWestern Desert,mobileforagersof Canada’sLabrador

Peninsula, tribes of Brazil’s Upper Xingu River basin, the Iroqu

Confederacy,the Swiss cantons that unified into Switzerland in

1848,and the United States since 1865,among others (Dennis,

1993;Fry,2006,2009,2012;Gregor,1994;Hendrickson,2003;

Parent,2011;Souillac and Fry,2015).When speaking ofpeace

systemsas lacking warfare,we are defining waras “relatively

impersonallethalaggression between communities,” a definition

of intergroup violence that applies across social types from ba

and tribes to kingdoms and nations (Fry,2006:p. 91).

A consideration of the theoreticalliterature and ethnographic

descriptionssuggeststhat variousfactorscontributeto inter-

societalpeace (Archer,2003;Cronin,1999;Fry, 2012;Nowak

et al., 2012; Parent, 2011; Rubin et al., 1994; Souillac, 2020).

are archaeologicalindicationsof peacesystemsin prehistory

(Ferguson,2013;Fry,2012;Haas,1999) and ethnographic and

historicaldescriptionsof non-warring socialsystems,but the

peacesystem concepthas only recently taken shape.Gregor

(1994) applied the term peace system to ten neighbouring tri

representing fourdifferentlanguagegroups,from theUpper

Xingu River region of Brazil wherein “the politically autonomo

tribes actsomewhatlike linguistically distinctand residentially

separate ethnic groups within a larger socialframework of com-

mon institutionsand values”(Gregor,1994:p. 244).Gregor

(1990,1994) proposed thatthe interdependentrelationships in

trade among the tribes,the patterns of intermarriage,participa-

tion in common rituals and ceremonies,and the strong anti-war

values taught to each new generation combine to keep this sy

self-sustaining.

Fry (2009,2012)expanded the peace system constructcon-

ceptually and geographically beyond the UpperXingu case by

providing descriptionsof the IroquoisConfederacy,Aboriginal

Australia,and the European Union as additionalpeace systems.

For example,prior to the formation of the Iroquois Confederacy,

the originalfive member tribes,the Seneca,Cayuga,Onondaga,

Oneida,and Mohawk,werelocked into chronicwarring and

feuding (Dennis,1993;Fenton,1998;Fry,2012).The Iroquoian

peoples developed a new overarching identity in addition to t

tribal identities, which they expressed metaphorically as five

familiesliving in harmony in the same longhouse (see Fig.2;

Fenton,1998).They expanded the tried-and-true institutions of

the village council and tribal council to create the new higher-

institution,the Councilof Chiefs,as an intertribalmechanism of

governance and conflictmanagementbased on discussion and

consensus (Dennis,1993;Fenton,1998).Peace values and norms

werereinforced bynarratives,symbols,and rituals,such as

through the legend ofthe Peacemaker bringing tranquility and

unity to the five tribes and the enactment of unifying condole

rites (Dennis,1993;Fenton,1998;Fry,2012).Are such features

generally found in peace systems?

Peace system hypotheses

We hypothesise multiple contributors to peace (Fry, 2012; No

et al.,2012;Souillac,2012;Souillac and Fry,2015).Drawing on

Fig. 1 The five Nordic Nations, Norden, have not engaged in war with one

another since 1815.A dispute between Finland and Sweden over the

strategically located Åland Islands was resolved through mediation.The

Åland Islands remain a demilitarised and neutralarea.Reproduced with

permission of Douglas P.Fry;copyright © Douglas P.Fry,all rights

reserved.

ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

2 H U M A N I T I E S A N D S O C I A L S C I E N C E S C O M M U N I C A T I O N S |(2021)8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

ethnographic data from the Upper Xingu peace system (Gregor,

1990,1994;Ireland,1986),the IroquoisConfederacy (Dennis,

1993;Fenton,1998),the peaceablesocietiesof peninsular

Malaysia (Dentan,2004;Endicott,2017;Endicott and Endicott,

2008;Howell,1989),the non-warring neighbours ofthe Nilgiri

Hills in India (Rivers,1986;Walker,1986),the European Union

(Bellier and Wilson,2000;Hill, 2010;Staab,2008),and other

cases,Fry (2012)hypothesised thatmultiplefactorspromote

peacewithin dynamicpeacesystems.Theseinclude(1) an

overarching common identity in addition to local identities,(2) a

high degree ofprosocialinterconnectednessamong the social

unitswithin a system,(3) interdependenceamong the social

units,(4) core values and norms that are non-warring and peace

favouring,(5) narratives,rituals,ceremonies,and symbols that

reinforcepeacefulvalues,norms,beliefs,and conduct,(6)

superordinate institutions,(7) mechanisms for nonviolent inter-

group conflictmanagement,and (8) visionary peace leadership

(Fry,2009,2012;Souillac and Fry,2015;Souillac,2020).This list

of hypothesised peace-related factors stems both from case stu-

dies ofpeace systems and from a diverse setof socialscience

studies on intergroup conflictand peacemaking (Coleman and

Deutsch,2012;Dennis,1993;Dovidio etal., 2000;Fry, 2006;

Goldschmidt, 1994; Gregor, 1994; Parent, 2011; Rubin et al., 1994;

Schirch,2014;Souillac,2020).In this study,we compared sta-

tistically a group ofethnographically and historically described

peacesystemswith a randomlyderivedcomparison group

regarding the above peace hypotheses and also regarding several

war-related variables (e.g.,war norms and values and war lea-

dership) predicted to be less manifested within peace systems.

Methods

Samples.We soughtpeace systems in the anthropologicaland

historicalliterature to compare with a sample of non-peace sys-

tems regardingvarious featureshypothesisedto promote

dynamic peace among neighbouring social units (Fry,2012).We

were able to locate 16 well-documented examples ofpeace sys-

temsin the literature thatcomprise the experimentalsample.

Undoubtedly,additionalpeace systems exist and willbe uncov-

ered in the future.

The task offinding clusters of neighbouring societies that do

not make war with each other is complicated by the paucity of

scholarly attention that has been paid to this phenomenon. Si

our research group operationally defined peace systems for th

first time (Fry,2009,2012;Souillac and Fry,2015),there was no

catalogue,list,or database ofknown peace systems before we

began this line of research.The cases located represent different

levels of socialorganisation (e.g.,bands,tribes,nations) across a

world-wide distribution and include nearly allknown anthro-

pologicalexamplesof peace systems(Supplementary Table S1

online).

Extracting data for each peace system and comparison case

from the literature is a time-consuming process.The location of

sources,careful review of the material,and coding of each case is

labour intensive, which also limits the sample size due to prac

considerations.An implication of small sample size is that some

of the results may reflect type two errors,for example,regarding

the non-significantdifferencesfor intermarriage asa form of

interconnectedness or conflict management overall.

To derive a geographically diverse comparison group of non

peace systems,cases were randomly derived from the Standard

Cross-CulturalSample (SCCS) in order to focus on the selected

societiesand theiradjacentneighbours(Murdock and White,

1969,2006;White,1989).The SCCS represents186 cultural

provinces from around the world and various types of societie

(White,1989).The range of SCCS case numbers—that is,from 1

to 186 to represent each case number in the SCCS—was ente

as the sampling poolinto an online random number generator

(Haarh, 2020). Our target number for the comparison sample

at least 30 to balance a reasonable number ofcases against the

labour-intensive coding process for each case, and we genera

list of 33 randomly selected cases from the SCCS.Any duplicate

occurring random numbers were simply tossed outand a new

number generated to represent a novel society from the pool.

randomly generated case represented one ofthe known peace

systems, it was also eliminated and replaced by a newly gene

random number.We over-sampled by three cases with the idea

thata few ofthe key bibliographic sources mightprove to be

unavailable or only available in a non-English language.In fact,

such constraints reduced the originalrandomly derived compar-

ison cases from 33 to 30,as listed in Supplementary Table S2

online.

Procedure.A coding sheet(seeSupplementaryInformation

online) was designed for use in scoring the entire sample of 4

cases (peace systems and non-peace systems) regarding vari

hypothesisedto contributeto peacefulrelationshipsamong

neighbouring socialunits (Ember and Ember,2001).The list of

hypothesised featuresthatcontribute to the origin and main-

tenance of peace systems consisted of those features listed in

(2012),plus a new variable on visionary peace leadership.Addi-

tionally,severalvariables that focused on war were included for

comparative purposes.

For each peacesystem in the sample,we developeda

bibliography ofculturalsourcesto use forcoding.The peace

system reference citationsare included in the Supplementary

Information online asbibliographiesfor each system.For the

cases in the non-peace system comparison sample,we reviewed

the ethnographic materialranked by White (1989) in the SCCS

bibliography as principalauthority sources (PAS),meaning that

these are high-quality primary sources.We used only the PAS

listed in White’s(1989)bibliography to acquirethe relevant

information on each non-peacesystem case(Supplementary

Table S2 online).

Statisticalanalyses.Coded data were entered into a numerical

database(SupplementaryInformation online, Data file).

Fig. 2 An Iroquois village showing longhouses. The member tribes of the

Iroquois Confederacy,which lasted over 300 years,gave up warring with

one another.The revered peacemaker-prophet named Diganawidah is

reputed to have drawn an analogy between the families of a longhouse

living harmoniously under one shared roof and the tribes of the confederacy

living in unity and peace under the law.Reproduced with permission of

Douglas P.Fry;copyright © Douglas P.Fry,all rights reserved.

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 ARTICLE

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS |(2021) 8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 3

1990,1994;Ireland,1986),the IroquoisConfederacy (Dennis,

1993;Fenton,1998),the peaceablesocietiesof peninsular

Malaysia (Dentan,2004;Endicott,2017;Endicott and Endicott,

2008;Howell,1989),the non-warring neighbours ofthe Nilgiri

Hills in India (Rivers,1986;Walker,1986),the European Union

(Bellier and Wilson,2000;Hill, 2010;Staab,2008),and other

cases,Fry (2012)hypothesised thatmultiplefactorspromote

peacewithin dynamicpeacesystems.Theseinclude(1) an

overarching common identity in addition to local identities,(2) a

high degree ofprosocialinterconnectednessamong the social

unitswithin a system,(3) interdependenceamong the social

units,(4) core values and norms that are non-warring and peace

favouring,(5) narratives,rituals,ceremonies,and symbols that

reinforcepeacefulvalues,norms,beliefs,and conduct,(6)

superordinate institutions,(7) mechanisms for nonviolent inter-

group conflictmanagement,and (8) visionary peace leadership

(Fry,2009,2012;Souillac and Fry,2015;Souillac,2020).This list

of hypothesised peace-related factors stems both from case stu-

dies ofpeace systems and from a diverse setof socialscience

studies on intergroup conflictand peacemaking (Coleman and

Deutsch,2012;Dennis,1993;Dovidio etal., 2000;Fry, 2006;

Goldschmidt, 1994; Gregor, 1994; Parent, 2011; Rubin et al., 1994;

Schirch,2014;Souillac,2020).In this study,we compared sta-

tistically a group ofethnographically and historically described

peacesystemswith a randomlyderivedcomparison group

regarding the above peace hypotheses and also regarding several

war-related variables (e.g.,war norms and values and war lea-

dership) predicted to be less manifested within peace systems.

Methods

Samples.We soughtpeace systems in the anthropologicaland

historicalliterature to compare with a sample of non-peace sys-

tems regardingvarious featureshypothesisedto promote

dynamic peace among neighbouring social units (Fry,2012).We

were able to locate 16 well-documented examples ofpeace sys-

temsin the literature thatcomprise the experimentalsample.

Undoubtedly,additionalpeace systems exist and willbe uncov-

ered in the future.

The task offinding clusters of neighbouring societies that do

not make war with each other is complicated by the paucity of

scholarly attention that has been paid to this phenomenon. Si

our research group operationally defined peace systems for th

first time (Fry,2009,2012;Souillac and Fry,2015),there was no

catalogue,list,or database ofknown peace systems before we

began this line of research.The cases located represent different

levels of socialorganisation (e.g.,bands,tribes,nations) across a

world-wide distribution and include nearly allknown anthro-

pologicalexamplesof peace systems(Supplementary Table S1

online).

Extracting data for each peace system and comparison case

from the literature is a time-consuming process.The location of

sources,careful review of the material,and coding of each case is

labour intensive, which also limits the sample size due to prac

considerations.An implication of small sample size is that some

of the results may reflect type two errors,for example,regarding

the non-significantdifferencesfor intermarriage asa form of

interconnectedness or conflict management overall.

To derive a geographically diverse comparison group of non

peace systems,cases were randomly derived from the Standard

Cross-CulturalSample (SCCS) in order to focus on the selected

societiesand theiradjacentneighbours(Murdock and White,

1969,2006;White,1989).The SCCS represents186 cultural

provinces from around the world and various types of societie

(White,1989).The range of SCCS case numbers—that is,from 1

to 186 to represent each case number in the SCCS—was ente

as the sampling poolinto an online random number generator

(Haarh, 2020). Our target number for the comparison sample

at least 30 to balance a reasonable number ofcases against the

labour-intensive coding process for each case, and we genera

list of 33 randomly selected cases from the SCCS.Any duplicate

occurring random numbers were simply tossed outand a new

number generated to represent a novel society from the pool.

randomly generated case represented one ofthe known peace

systems, it was also eliminated and replaced by a newly gene

random number.We over-sampled by three cases with the idea

thata few ofthe key bibliographic sources mightprove to be

unavailable or only available in a non-English language.In fact,

such constraints reduced the originalrandomly derived compar-

ison cases from 33 to 30,as listed in Supplementary Table S2

online.

Procedure.A coding sheet(seeSupplementaryInformation

online) was designed for use in scoring the entire sample of 4

cases (peace systems and non-peace systems) regarding vari

hypothesisedto contributeto peacefulrelationshipsamong

neighbouring socialunits (Ember and Ember,2001).The list of

hypothesised featuresthatcontribute to the origin and main-

tenance of peace systems consisted of those features listed in

(2012),plus a new variable on visionary peace leadership.Addi-

tionally,severalvariables that focused on war were included for

comparative purposes.

For each peacesystem in the sample,we developeda

bibliography ofculturalsourcesto use forcoding.The peace

system reference citationsare included in the Supplementary

Information online asbibliographiesfor each system.For the

cases in the non-peace system comparison sample,we reviewed

the ethnographic materialranked by White (1989) in the SCCS

bibliography as principalauthority sources (PAS),meaning that

these are high-quality primary sources.We used only the PAS

listed in White’s(1989)bibliography to acquirethe relevant

information on each non-peacesystem case(Supplementary

Table S2 online).

Statisticalanalyses.Coded data were entered into a numerical

database(SupplementaryInformation online, Data file).

Fig. 2 An Iroquois village showing longhouses. The member tribes of the

Iroquois Confederacy,which lasted over 300 years,gave up warring with

one another.The revered peacemaker-prophet named Diganawidah is

reputed to have drawn an analogy between the families of a longhouse

living harmoniously under one shared roof and the tribes of the confederacy

living in unity and peace under the law.Reproduced with permission of

Douglas P.Fry;copyright © Douglas P.Fry,all rights reserved.

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 ARTICLE

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS |(2021) 8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 3

Correlations and Mann–Whitney U-tests were run using IBM’s

StatisticalPackage for the SocialSciences (SPSS),version 26.0

(IBM, 2019).Since correlationsinvolveordinalvariablesand

smallgroup sizes,the reported p-values are for Kendall’s Tau

statistic.Since normality could not be assumed for the variables

in this relatively smallsample,Mann–Whitney U-testswere

considered more appropriate (and conservative) than Student’s

t-tests for comparing the two sub-samples.Missing values were

replaced by mean values in SPSS.

The data science classification algorithm called Random Forest

was used to assessthe relativeimportanceof variables

hypothesisedto contributeto peace.Random Forestis a

supervisedmachinelearningmethodthat can be used to

determinethe relativeimportanceof differentvariablesin

reaching a classification decision,in this case to separate peace

systems from non-peaceful systems (Raschka and Mirjalili,2017;

Yiu, 2019).During a training phase,Random Forest constructs

many individualdecision trees.The processusesa randomly

selected subset of the data and variables to construct this “random

forest” of decision trees. The using of different subsets of the data

and different variables to generate individualtrees increases the

variation among trees in the ensemble.The prediction from the

individualdecision treesare then pooled formaking a final

predictionabout the relativeimportanceof variables.The

combined decision treesconstituting thisRandom Foresthas

the capacityto makemore accuratepredictionsthan any

individualdecision tree alone.The procedure also ensures that

the final Random Forest does not overfit the original training set.

We used theRandom Forestclassifierfrom the scikit-learn

python library (Pedregosa etal.,2011) with the parameter that

specifies the number of the decision trees,“n estimators,” set to

2000 and the initial random seed set to “random_state=42.” After

the classifierwastrained,we used the“feature_importances”

attribute to extractthe importance score for each peace-related

variable,which allows the ranking ofthe variables as to their

relative importance for a peace system outcome.We applied the

machine learning analysis to allthe peace-related variables that

showedstatisticallysignificantdifferencesbetweenthe two

samples by Mann–Whitney U-tests and included one additional

variable that showed only a non-significant trend in the predicted

direction,overarching governance,to have atleastone variable

represented in the analysisfor each ofthe eighthypothesised

peace system features.

Results

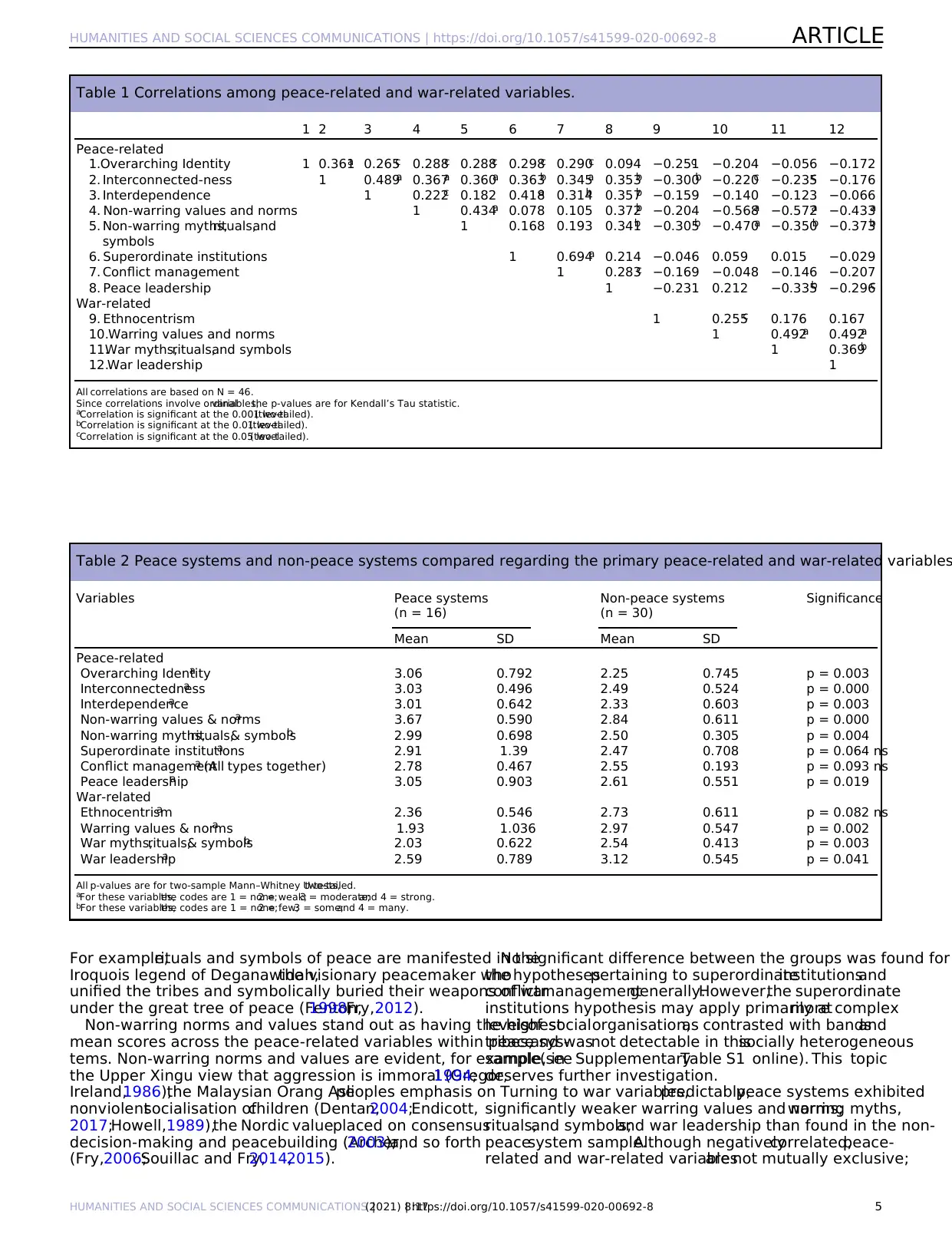

We firstran correlation analyses across the entire sample and

found many significantcorrelationsamong the eightfeatures

hypothesised to be elements of dynamic peace systems (Table 1).

All significantcorrelationsamong peace-related variableswere

positive.Common overarching identity and interconnectedness

werepositively correlated with allseven otherpeacesystem

variables.On the other hand,all significant correlations between

peace variables and war variables were negative.We found some

of the strongest negative correlations between peace norms and

values,peace myths,rituals,and symbols,and peace leadership,

on the one hand,and war norms and values,war myths,rituals,

and symbols,and war leadership on the other.Finally,with the

partial exception of ethnocentrism, war features were found to be

positively correlated with each other.

To address whether the features hypothesised to be important

elements ofpeace systems were manifested to a greater extent

within peace systems than within non-peace systems, we ran two-

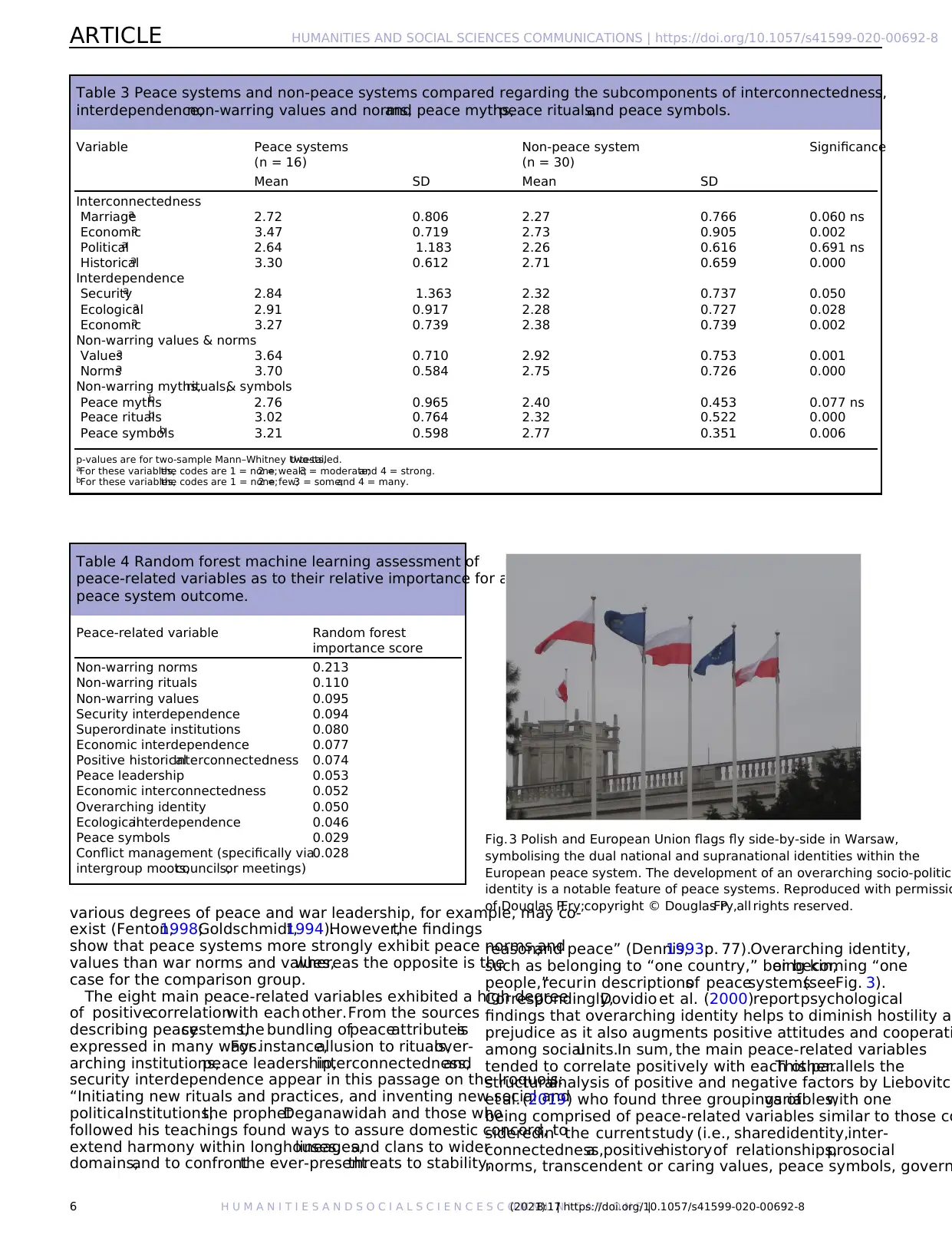

sample Mann–Whitney U-tests (Table 2).Inaccordance with six-

out-of-eightof the main predictions,the peace system sample

scored significantly higher than the non-peace system sample for

overarchingidentity; positive interconnectedness;inter-

dependence;non-warring values and norms;non-warring myths,

rituals,and symbols;and peace leadership.The two variables

superordinate institutions and nonviolentconflictmanagement

overallwere notsignificantly differentbetween the samples.By

contrast,non-peace systems scored significantly higher for war

ring values and norms;war myths,rituals,and symbols;and war

leadership.Ethnocentrism was not significantly different betwee

the samples.

We also performed a more granular analysis (Table 3).When

four measuresof prosocialinterconnectedness(intermarriage,

trade, politics, and positive history) were analysed separately

economicand historicalinterconnectednessweresignificantly

greaterin peace systems than in non-peace systems,although

intermarriageapproached significance.All threesubtypesof

interdependence (security,ecological,and economic)were sig-

nificantly greater in the peace system sample than in the com

parison sample,with economicinterdependencebeing highly

significant.When non-warring values and non-warring norms

weredisaggregated forseparateanalysis,both variableswere

found to be significantly more pronounced in peace systems t

in non-peace systems.Finally,when we analysed the three sub-

elements of non-warring myths,rituals,and symbols separately,

peace rituals and symbols turned out to be significantly differ

between the two samples,but peace myths were not.

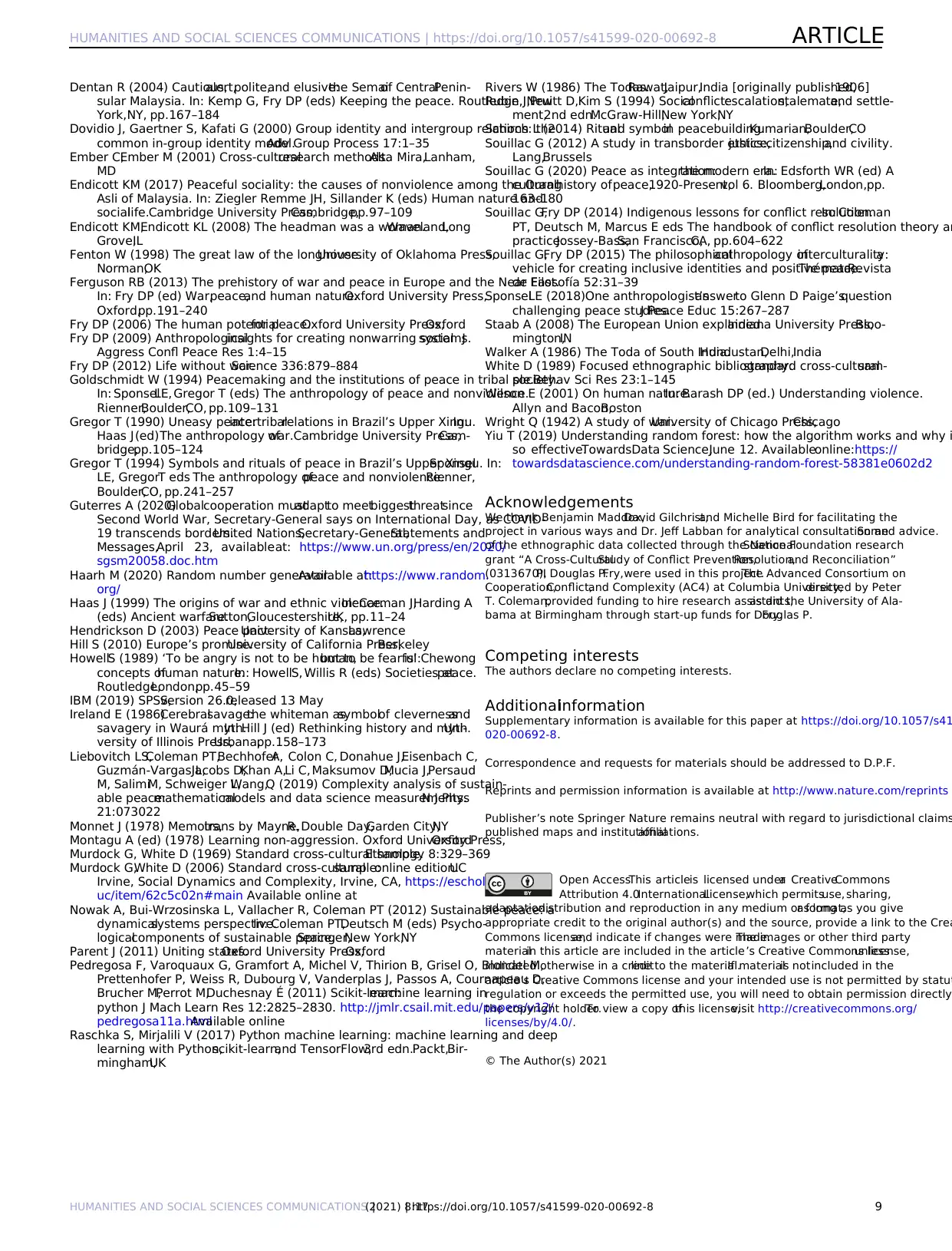

To address the question of which hypothesised variables we

relatively more important contributors to peace, we employed

machine learning technique called Random Forest. We found

the mostimportantcontributing factor to a peace system out-

come was the existence of non-warring norms,followed in order

of decreasing importance by non-warring rituals,non-warring

values, security interdependence, and so forth (Table 4). Thus, the

Random Forestanalysisprovided amethod forranking the

relative importance of the peace-related variables for leading

peacesystem outcomeas opposedto a non-peacesystem

outcome.

Discussion

Peace systems research challenges the assumption thatsocieties

everywhereare inclined to makewar with theirneighbours.

Science-based understanding ofhow peace systems emerge and

are maintained may have implications for creating and promo

peace and cooperation in variouscontexts,whetherwithin a

nation,among nations,regionally,or globally (Coleman and

Deutsch,2012;Fry,2012).Our findings demonstrate that peace

systems,definedbehaviourallyas clustersof neighbouring

societies that do not make war on each other, differ on a varie

dimensions from societies that are not part of such social syst

We found most of the main hypothesised peace contributors t

present to a greater degree in peace systems than in a rando

selected comparison sample across various levels of socialcom-

plexity.This suggests there are recurring features that can con

tributeto the developmentand maintenanceof non-warring

relationships among societies.Consequently,an analysis of peace

systems may offer transferable insights abouthow to promote

prosocial,cooperative inter-societalrelations at various levels of

socialorganisation.

When the eight peace-related hypotheses were partitioned

more granular predictions,differences between the peace systems

and the comparison sample were significantfor economic and

positivehistoricalinterconnectionsbut not for intermarriage

and politicalinterconnections.Both non-warringnormsand

non-warring values were significant,as were peace rituals and

symbols. Peace rituals and symbols may reflect and reinforce

values and norms (Dennis,1993;Gregor,1994;Schirch,2014).

ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

4 H U M A N I T I E S A N D S O C I A L S C I E N C E S C O M M U N I C A T I O N S |(2021)8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

StatisticalPackage for the SocialSciences (SPSS),version 26.0

(IBM, 2019).Since correlationsinvolveordinalvariablesand

smallgroup sizes,the reported p-values are for Kendall’s Tau

statistic.Since normality could not be assumed for the variables

in this relatively smallsample,Mann–Whitney U-testswere

considered more appropriate (and conservative) than Student’s

t-tests for comparing the two sub-samples.Missing values were

replaced by mean values in SPSS.

The data science classification algorithm called Random Forest

was used to assessthe relativeimportanceof variables

hypothesisedto contributeto peace.Random Forestis a

supervisedmachinelearningmethodthat can be used to

determinethe relativeimportanceof differentvariablesin

reaching a classification decision,in this case to separate peace

systems from non-peaceful systems (Raschka and Mirjalili,2017;

Yiu, 2019).During a training phase,Random Forest constructs

many individualdecision trees.The processusesa randomly

selected subset of the data and variables to construct this “random

forest” of decision trees. The using of different subsets of the data

and different variables to generate individualtrees increases the

variation among trees in the ensemble.The prediction from the

individualdecision treesare then pooled formaking a final

predictionabout the relativeimportanceof variables.The

combined decision treesconstituting thisRandom Foresthas

the capacityto makemore accuratepredictionsthan any

individualdecision tree alone.The procedure also ensures that

the final Random Forest does not overfit the original training set.

We used theRandom Forestclassifierfrom the scikit-learn

python library (Pedregosa etal.,2011) with the parameter that

specifies the number of the decision trees,“n estimators,” set to

2000 and the initial random seed set to “random_state=42.” After

the classifierwastrained,we used the“feature_importances”

attribute to extractthe importance score for each peace-related

variable,which allows the ranking ofthe variables as to their

relative importance for a peace system outcome.We applied the

machine learning analysis to allthe peace-related variables that

showedstatisticallysignificantdifferencesbetweenthe two

samples by Mann–Whitney U-tests and included one additional

variable that showed only a non-significant trend in the predicted

direction,overarching governance,to have atleastone variable

represented in the analysisfor each ofthe eighthypothesised

peace system features.

Results

We firstran correlation analyses across the entire sample and

found many significantcorrelationsamong the eightfeatures

hypothesised to be elements of dynamic peace systems (Table 1).

All significantcorrelationsamong peace-related variableswere

positive.Common overarching identity and interconnectedness

werepositively correlated with allseven otherpeacesystem

variables.On the other hand,all significant correlations between

peace variables and war variables were negative.We found some

of the strongest negative correlations between peace norms and

values,peace myths,rituals,and symbols,and peace leadership,

on the one hand,and war norms and values,war myths,rituals,

and symbols,and war leadership on the other.Finally,with the

partial exception of ethnocentrism, war features were found to be

positively correlated with each other.

To address whether the features hypothesised to be important

elements ofpeace systems were manifested to a greater extent

within peace systems than within non-peace systems, we ran two-

sample Mann–Whitney U-tests (Table 2).Inaccordance with six-

out-of-eightof the main predictions,the peace system sample

scored significantly higher than the non-peace system sample for

overarchingidentity; positive interconnectedness;inter-

dependence;non-warring values and norms;non-warring myths,

rituals,and symbols;and peace leadership.The two variables

superordinate institutions and nonviolentconflictmanagement

overallwere notsignificantly differentbetween the samples.By

contrast,non-peace systems scored significantly higher for war

ring values and norms;war myths,rituals,and symbols;and war

leadership.Ethnocentrism was not significantly different betwee

the samples.

We also performed a more granular analysis (Table 3).When

four measuresof prosocialinterconnectedness(intermarriage,

trade, politics, and positive history) were analysed separately

economicand historicalinterconnectednessweresignificantly

greaterin peace systems than in non-peace systems,although

intermarriageapproached significance.All threesubtypesof

interdependence (security,ecological,and economic)were sig-

nificantly greater in the peace system sample than in the com

parison sample,with economicinterdependencebeing highly

significant.When non-warring values and non-warring norms

weredisaggregated forseparateanalysis,both variableswere

found to be significantly more pronounced in peace systems t

in non-peace systems.Finally,when we analysed the three sub-

elements of non-warring myths,rituals,and symbols separately,

peace rituals and symbols turned out to be significantly differ

between the two samples,but peace myths were not.

To address the question of which hypothesised variables we

relatively more important contributors to peace, we employed

machine learning technique called Random Forest. We found

the mostimportantcontributing factor to a peace system out-

come was the existence of non-warring norms,followed in order

of decreasing importance by non-warring rituals,non-warring

values, security interdependence, and so forth (Table 4). Thus, the

Random Forestanalysisprovided amethod forranking the

relative importance of the peace-related variables for leading

peacesystem outcomeas opposedto a non-peacesystem

outcome.

Discussion

Peace systems research challenges the assumption thatsocieties

everywhereare inclined to makewar with theirneighbours.

Science-based understanding ofhow peace systems emerge and

are maintained may have implications for creating and promo

peace and cooperation in variouscontexts,whetherwithin a

nation,among nations,regionally,or globally (Coleman and

Deutsch,2012;Fry,2012).Our findings demonstrate that peace

systems,definedbehaviourallyas clustersof neighbouring

societies that do not make war on each other, differ on a varie

dimensions from societies that are not part of such social syst

We found most of the main hypothesised peace contributors t

present to a greater degree in peace systems than in a rando

selected comparison sample across various levels of socialcom-

plexity.This suggests there are recurring features that can con

tributeto the developmentand maintenanceof non-warring

relationships among societies.Consequently,an analysis of peace

systems may offer transferable insights abouthow to promote

prosocial,cooperative inter-societalrelations at various levels of

socialorganisation.

When the eight peace-related hypotheses were partitioned

more granular predictions,differences between the peace systems

and the comparison sample were significantfor economic and

positivehistoricalinterconnectionsbut not for intermarriage

and politicalinterconnections.Both non-warringnormsand

non-warring values were significant,as were peace rituals and

symbols. Peace rituals and symbols may reflect and reinforce

values and norms (Dennis,1993;Gregor,1994;Schirch,2014).

ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

4 H U M A N I T I E S A N D S O C I A L S C I E N C E S C O M M U N I C A T I O N S |(2021)8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

For example,rituals and symbols of peace are manifested in the

Iroquois legend of Deganawidah,the visionary peacemaker who

unified the tribes and symbolically buried their weapons of war

under the great tree of peace (Fenton,1998;Fry,2012).

Non-warring norms and values stand out as having the highest

mean scores across the peace-related variables within peace sys-

tems. Non-warring norms and values are evident, for example, in

the Upper Xingu view that aggression is immoral (Gregor,1994;

Ireland,1986),the Malaysian Orang Aslipeoples emphasis on

nonviolentsocialisation ofchildren (Dentan,2004;Endicott,

2017;Howell,1989),the Nordic valueplaced on consensus

decision-making and peacebuilding (Archer,2003),and so forth

(Fry,2006;Souillac and Fry,2014,2015).

No significant difference between the groups was found for

the hypothesespertaining to superordinateinstitutionsand

conflictmanagementgenerally.However,the superordinate

institutions hypothesis may apply primarily atmore complex

levelsof socialorganisation,as contrasted with bandsand

tribes,and wasnot detectable in thissocially heterogeneous

sample(see SupplementaryTable S1 online). This topic

deserves further investigation.

Turning to war variables,predictably,peace systems exhibited

significantly weaker warring values and norms;warring myths,

rituals,and symbols;and war leadership than found in the non-

peacesystem sample.Although negativelycorrelated,peace-

related and war-related variablesare not mutually exclusive;

Table 1 Correlations among peace-related and war-related variables.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Peace-related

1.Overarching Identity 1 0.361a 0.265c 0.288c 0.288c 0.298c 0.290c 0.094 −0.251c −0.204 −0.056 −0.172

2. Interconnected-ness 1 0.489a 0.367a 0.360a 0.363b 0.345a 0.353b −0.300b −0.220c −0.235c −0.176

3. Interdependence 1 0.222c 0.182 0.418a 0.314b 0.357b −0.159 −0.140 −0.123 −0.066

4. Non-warring values and norms 1 0.434a 0.078 0.105 0.372b −0.204 −0.568a −0.572a −0.433a

5. Non-warring myths,rituals,and

symbols

1 0.168 0.193 0.341b −0.305b −0.470a −0.350b −0.373b

6. Superordinate institutions 1 0.694a 0.214 −0.046 0.059 0.015 −0.029

7. Conflict management 1 0.283c −0.169 −0.048 −0.146 −0.207

8. Peace leadership 1 −0.231 0.212 −0.335b −0.296c

War-related

9. Ethnocentrism 1 0.255c 0.176 0.167

10.Warring values and norms 1 0.492a 0.492a

11.War myths,rituals,and symbols 1 0.369b

12.War leadership 1

All correlations are based on N = 46.

Since correlations involve ordinalvariables,the p-values are for Kendall’s Tau statistic.

aCorrelation is significant at the 0.001 level(two-tailed).

bCorrelation is significant at the 0.01 level(two-tailed).

cCorrelation is significant at the 0.05 level(two-tailed).

Table 2 Peace systems and non-peace systems compared regarding the primary peace-related and war-related variables

Variables Peace systems

(n = 16)

Non-peace systems

(n = 30)

Significance

Mean SD Mean SD

Peace-related

Overarching Identitya 3.06 0.792 2.25 0.745 p = 0.003

Interconnectednessa 3.03 0.496 2.49 0.524 p = 0.000

Interdependencea 3.01 0.642 2.33 0.603 p = 0.003

Non-warring values & normsa 3.67 0.590 2.84 0.611 p = 0.000

Non-warring myths,rituals,& symbolsb 2.99 0.698 2.50 0.305 p = 0.004

Superordinate institutionsa 2.91 1.39 2.47 0.708 p = 0.064 ns

Conflict managementa (All types together) 2.78 0.467 2.55 0.193 p = 0.093 ns

Peace leadershipa 3.05 0.903 2.61 0.551 p = 0.019

War-related

Ethnocentrisma 2.36 0.546 2.73 0.611 p = 0.082 ns

Warring values & normsa 1.93 1.036 2.97 0.547 p = 0.002

War myths,rituals,& symbolsb 2.03 0.622 2.54 0.413 p = 0.003

War leadershipa 2.59 0.789 3.12 0.545 p = 0.041

All p-values are for two-sample Mann–Whitney U-tests,two-tailed.

aFor these variables,the codes are 1 = none;2 = weak;3 = moderate;and 4 = strong.

bFor these variables,the codes are 1 = none;2 = few;3 = some;and 4 = many.

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 ARTICLE

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS |(2021) 8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 5

Iroquois legend of Deganawidah,the visionary peacemaker who

unified the tribes and symbolically buried their weapons of war

under the great tree of peace (Fenton,1998;Fry,2012).

Non-warring norms and values stand out as having the highest

mean scores across the peace-related variables within peace sys-

tems. Non-warring norms and values are evident, for example, in

the Upper Xingu view that aggression is immoral (Gregor,1994;

Ireland,1986),the Malaysian Orang Aslipeoples emphasis on

nonviolentsocialisation ofchildren (Dentan,2004;Endicott,

2017;Howell,1989),the Nordic valueplaced on consensus

decision-making and peacebuilding (Archer,2003),and so forth

(Fry,2006;Souillac and Fry,2014,2015).

No significant difference between the groups was found for

the hypothesespertaining to superordinateinstitutionsand

conflictmanagementgenerally.However,the superordinate

institutions hypothesis may apply primarily atmore complex

levelsof socialorganisation,as contrasted with bandsand

tribes,and wasnot detectable in thissocially heterogeneous

sample(see SupplementaryTable S1 online). This topic

deserves further investigation.

Turning to war variables,predictably,peace systems exhibited

significantly weaker warring values and norms;warring myths,

rituals,and symbols;and war leadership than found in the non-

peacesystem sample.Although negativelycorrelated,peace-

related and war-related variablesare not mutually exclusive;

Table 1 Correlations among peace-related and war-related variables.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Peace-related

1.Overarching Identity 1 0.361a 0.265c 0.288c 0.288c 0.298c 0.290c 0.094 −0.251c −0.204 −0.056 −0.172

2. Interconnected-ness 1 0.489a 0.367a 0.360a 0.363b 0.345a 0.353b −0.300b −0.220c −0.235c −0.176

3. Interdependence 1 0.222c 0.182 0.418a 0.314b 0.357b −0.159 −0.140 −0.123 −0.066

4. Non-warring values and norms 1 0.434a 0.078 0.105 0.372b −0.204 −0.568a −0.572a −0.433a

5. Non-warring myths,rituals,and

symbols

1 0.168 0.193 0.341b −0.305b −0.470a −0.350b −0.373b

6. Superordinate institutions 1 0.694a 0.214 −0.046 0.059 0.015 −0.029

7. Conflict management 1 0.283c −0.169 −0.048 −0.146 −0.207

8. Peace leadership 1 −0.231 0.212 −0.335b −0.296c

War-related

9. Ethnocentrism 1 0.255c 0.176 0.167

10.Warring values and norms 1 0.492a 0.492a

11.War myths,rituals,and symbols 1 0.369b

12.War leadership 1

All correlations are based on N = 46.

Since correlations involve ordinalvariables,the p-values are for Kendall’s Tau statistic.

aCorrelation is significant at the 0.001 level(two-tailed).

bCorrelation is significant at the 0.01 level(two-tailed).

cCorrelation is significant at the 0.05 level(two-tailed).

Table 2 Peace systems and non-peace systems compared regarding the primary peace-related and war-related variables

Variables Peace systems

(n = 16)

Non-peace systems

(n = 30)

Significance

Mean SD Mean SD

Peace-related

Overarching Identitya 3.06 0.792 2.25 0.745 p = 0.003

Interconnectednessa 3.03 0.496 2.49 0.524 p = 0.000

Interdependencea 3.01 0.642 2.33 0.603 p = 0.003

Non-warring values & normsa 3.67 0.590 2.84 0.611 p = 0.000

Non-warring myths,rituals,& symbolsb 2.99 0.698 2.50 0.305 p = 0.004

Superordinate institutionsa 2.91 1.39 2.47 0.708 p = 0.064 ns

Conflict managementa (All types together) 2.78 0.467 2.55 0.193 p = 0.093 ns

Peace leadershipa 3.05 0.903 2.61 0.551 p = 0.019

War-related

Ethnocentrisma 2.36 0.546 2.73 0.611 p = 0.082 ns

Warring values & normsa 1.93 1.036 2.97 0.547 p = 0.002

War myths,rituals,& symbolsb 2.03 0.622 2.54 0.413 p = 0.003

War leadershipa 2.59 0.789 3.12 0.545 p = 0.041

All p-values are for two-sample Mann–Whitney U-tests,two-tailed.

aFor these variables,the codes are 1 = none;2 = weak;3 = moderate;and 4 = strong.

bFor these variables,the codes are 1 = none;2 = few;3 = some;and 4 = many.

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 ARTICLE

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS |(2021) 8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 5

various degrees of peace and war leadership, for example, may co-

exist (Fenton,1998;Goldschmidt,1994).However,the findings

show that peace systems more strongly exhibit peace norms and

values than war norms and values,whereas the opposite is the

case for the comparison group.

The eight main peace-related variables exhibited a high degree

of positivecorrelationwith each other.From the sources

describing peacesystems,the bundling ofpeaceattributesis

expressed in many ways.For instance,allusion to rituals,over-

arching institutions,peace leadership,interconnectedness,and

security interdependence appear in this passage on the Iroquois:

“Initiating new rituals and practices, and inventing new social and

politicalinstitutions,the prophetDeganawidah and those who

followed his teachings found ways to assure domestic concord, to

extend harmony within longhouses,lineages,and clans to wider

domains,and to confrontthe ever-presentthreats to stability,

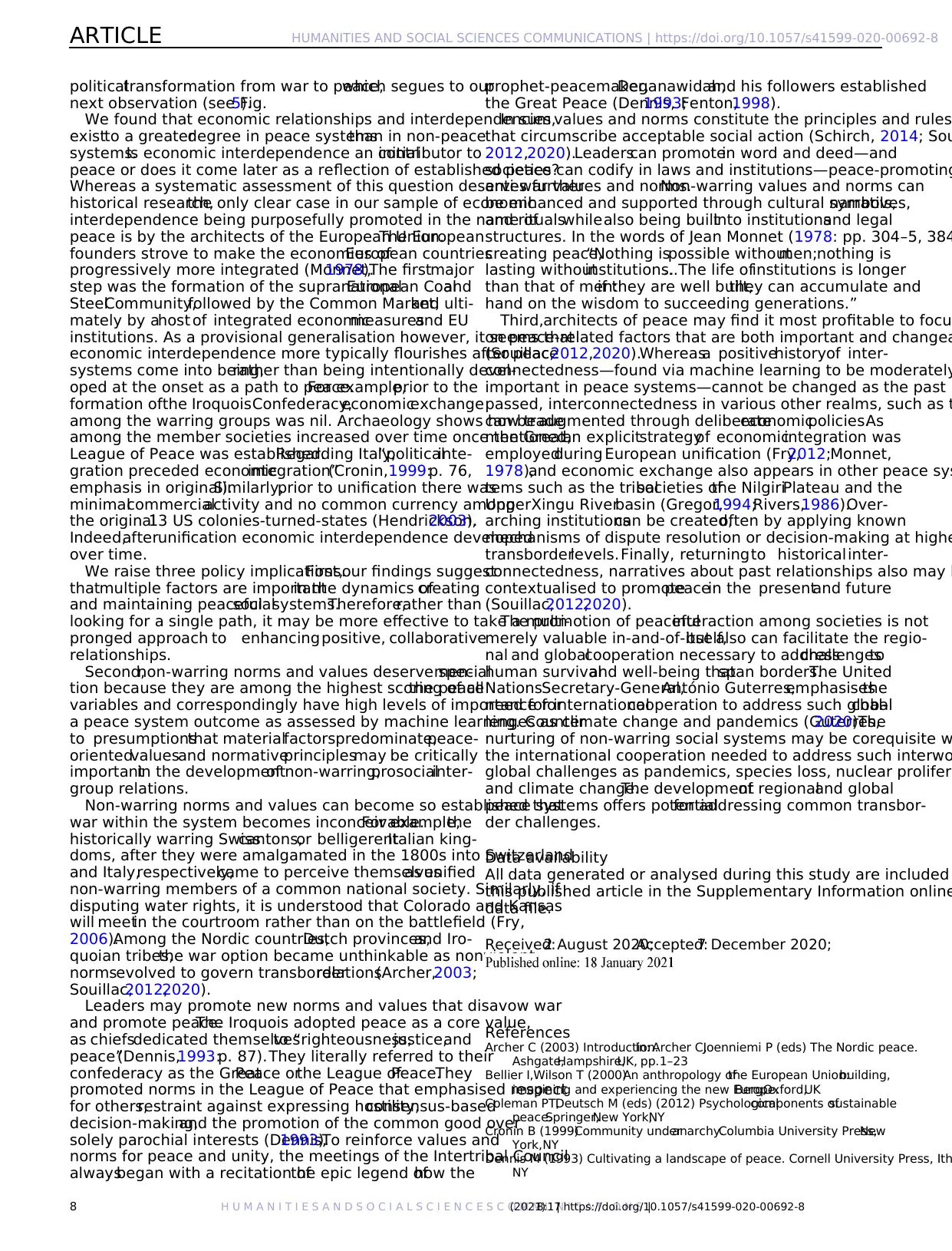

reason,and peace” (Dennis,1993:p. 77).Overarching identity,

such as belonging to “one country,” being kin,or becoming “one

people,”recurin descriptionsof peacesystems(seeFig. 3).

Correspondingly,Dovidio et al. (2000)reportpsychological

findings that overarching identity helps to diminish hostility a

prejudice as it also augments positive attitudes and cooperati

among socialunits.In sum, the main peace-related variables

tended to correlate positively with each other.This parallels the

structuralanalysis of positive and negative factors by Liebovitch

et al. (2019) who found three groupings ofvariables,with one

being comprised of peace-related variables similar to those co

sideredin the currentstudy (i.e., sharedidentity,inter-

connectedness,a positivehistoryof relationships,prosocial

norms, transcendent or caring values, peace symbols, govern

Table 3 Peace systems and non-peace systems compared regarding the subcomponents of interconnectedness,

interdependence,non-warring values and norms,and peace myths,peace rituals,and peace symbols.

Variable Peace systems

(n = 16)

Non-peace system

(n = 30)

Significance

Mean SD Mean SD

Interconnectedness

Marriagea 2.72 0.806 2.27 0.766 0.060 ns

Economica 3.47 0.719 2.73 0.905 0.002

Politicala 2.64 1.183 2.26 0.616 0.691 ns

Historicala 3.30 0.612 2.71 0.659 0.000

Interdependence

Securitya 2.84 1.363 2.32 0.737 0.050

Ecologicala 2.91 0.917 2.28 0.727 0.028

Economica 3.27 0.739 2.38 0.739 0.002

Non-warring values & norms

Valuesa 3.64 0.710 2.92 0.753 0.001

Normsa 3.70 0.584 2.75 0.726 0.000

Non-warring myths,rituals,& symbols

Peace mythsb 2.76 0.965 2.40 0.453 0.077 ns

Peace ritualsb 3.02 0.764 2.32 0.522 0.000

Peace symbolsb 3.21 0.598 2.77 0.351 0.006

p-values are for two-sample Mann–Whitney U-tests,two-tailed.

aFor these variables,the codes are 1 = none;2 = weak;3 = moderate;and 4 = strong.

bFor these variables,the codes are 1 = none;2 = few;3 = some;and 4 = many.

Table 4 Random forest machine learning assessment of

peace-related variables as to their relative importance for a

peace system outcome.

Peace-related variable Random forest

importance score

Non-warring norms 0.213

Non-warring rituals 0.110

Non-warring values 0.095

Security interdependence 0.094

Superordinate institutions 0.080

Economic interdependence 0.077

Positive historicalInterconnectedness 0.074

Peace leadership 0.053

Economic interconnectedness 0.052

Overarching identity 0.050

Ecologicalinterdependence 0.046

Peace symbols 0.029

Conflict management (specifically via

intergroup moots,councils,or meetings)

0.028

Fig.3 Polish and European Union flags fly side-by-side in Warsaw,

symbolising the dual national and supranational identities within the

European peace system. The development of an overarching socio-politic

identity is a notable feature of peace systems. Reproduced with permissio

of Douglas P.Fry;copyright © Douglas P.Fry,all rights reserved.

ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

6 H U M A N I T I E S A N D S O C I A L S C I E N C E S C O M M U N I C A T I O N S |(2021)8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

exist (Fenton,1998;Goldschmidt,1994).However,the findings

show that peace systems more strongly exhibit peace norms and

values than war norms and values,whereas the opposite is the

case for the comparison group.

The eight main peace-related variables exhibited a high degree

of positivecorrelationwith each other.From the sources

describing peacesystems,the bundling ofpeaceattributesis

expressed in many ways.For instance,allusion to rituals,over-

arching institutions,peace leadership,interconnectedness,and

security interdependence appear in this passage on the Iroquois:

“Initiating new rituals and practices, and inventing new social and

politicalinstitutions,the prophetDeganawidah and those who

followed his teachings found ways to assure domestic concord, to

extend harmony within longhouses,lineages,and clans to wider

domains,and to confrontthe ever-presentthreats to stability,

reason,and peace” (Dennis,1993:p. 77).Overarching identity,

such as belonging to “one country,” being kin,or becoming “one

people,”recurin descriptionsof peacesystems(seeFig. 3).

Correspondingly,Dovidio et al. (2000)reportpsychological

findings that overarching identity helps to diminish hostility a

prejudice as it also augments positive attitudes and cooperati

among socialunits.In sum, the main peace-related variables

tended to correlate positively with each other.This parallels the

structuralanalysis of positive and negative factors by Liebovitch

et al. (2019) who found three groupings ofvariables,with one

being comprised of peace-related variables similar to those co

sideredin the currentstudy (i.e., sharedidentity,inter-

connectedness,a positivehistoryof relationships,prosocial

norms, transcendent or caring values, peace symbols, govern

Table 3 Peace systems and non-peace systems compared regarding the subcomponents of interconnectedness,

interdependence,non-warring values and norms,and peace myths,peace rituals,and peace symbols.

Variable Peace systems

(n = 16)

Non-peace system

(n = 30)

Significance

Mean SD Mean SD

Interconnectedness

Marriagea 2.72 0.806 2.27 0.766 0.060 ns

Economica 3.47 0.719 2.73 0.905 0.002

Politicala 2.64 1.183 2.26 0.616 0.691 ns

Historicala 3.30 0.612 2.71 0.659 0.000

Interdependence

Securitya 2.84 1.363 2.32 0.737 0.050

Ecologicala 2.91 0.917 2.28 0.727 0.028

Economica 3.27 0.739 2.38 0.739 0.002

Non-warring values & norms

Valuesa 3.64 0.710 2.92 0.753 0.001

Normsa 3.70 0.584 2.75 0.726 0.000

Non-warring myths,rituals,& symbols

Peace mythsb 2.76 0.965 2.40 0.453 0.077 ns

Peace ritualsb 3.02 0.764 2.32 0.522 0.000

Peace symbolsb 3.21 0.598 2.77 0.351 0.006

p-values are for two-sample Mann–Whitney U-tests,two-tailed.

aFor these variables,the codes are 1 = none;2 = weak;3 = moderate;and 4 = strong.

bFor these variables,the codes are 1 = none;2 = few;3 = some;and 4 = many.

Table 4 Random forest machine learning assessment of

peace-related variables as to their relative importance for a

peace system outcome.

Peace-related variable Random forest

importance score

Non-warring norms 0.213

Non-warring rituals 0.110

Non-warring values 0.095

Security interdependence 0.094

Superordinate institutions 0.080

Economic interdependence 0.077

Positive historicalInterconnectedness 0.074

Peace leadership 0.053

Economic interconnectedness 0.052

Overarching identity 0.050

Ecologicalinterdependence 0.046

Peace symbols 0.029

Conflict management (specifically via

intergroup moots,councils,or meetings)

0.028

Fig.3 Polish and European Union flags fly side-by-side in Warsaw,

symbolising the dual national and supranational identities within the

European peace system. The development of an overarching socio-politic

identity is a notable feature of peace systems. Reproduced with permissio

of Douglas P.Fry;copyright © Douglas P.Fry,all rights reserved.

ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

6 H U M A N I T I E S A N D S O C I A L S C I E N C E S C O M M U N I C A T I O N S |(2021)8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

and peace leaders, and additionally, peace education, peace vision,

positive reciprocity,and positive goals).

With the partial exception of ethnocentrism, war variables also

positively correlated with one another. All significant correlations

between peace and war variables were negative, with peace versus

war values and norms showing a very a strong negative correla-

tion. Additionally,peacesystemstend to havesignificantly

strongerpeace valuesand norms,whereasnon-peace systems

tend to have significantly stronger war values and norms.

Perhaps, once established, either war or peace orientations may

stabiliseamongneighbouringsocieties.However,over time

conditions ofwar among neighbours can be transformed into

non-warring relationships, such as among the Swiss cantons after

Switzerland was formed,Italian states and kingdoms after uni-

fication,or the tribes of Iroquoia after the creation of their con-

federacy (Archer,2003;Fry, 2006;Sponsel,2018).The Nordic

countries transitioned “from a region rife with warfare to an area

whose conflicts are ‘non-wars’embracing diplomatic solutions”

(Archer,2003:p. 8).

An important topic for future research would be the investi-

gation ofwhich features found in peace systems have been key

driversof transformationsovertime from warto peace.The

collection of longitudinaldata,when available,on the nature of

historicaltransformationswould be necessary to addressthis

topic.Some peace systems such as the ten Upper Xingu peoples,

the Montagnais-Naskapi-EastMain Cree,the Malaysian Orang

Asli, and the Nigiri Plateau tribes were already in operation when

early ethnographic information was gathered,so the historical

roots of the non-warringintergroup relationsprobablywill

remain obscure.However,historicaland ethnohistoricaldata do

existfor some cases such as the formation ofSwitzerland,the

United States,and the Iroquois confederacy.The findings of this

study lead to severalprovisionalobservations thatare ripe for

further historicalinvestigation.

First,it seems thata sense ofoverarching identity develops

gradually over time,becoming,as found in our study,a main-

taining feature of peace systems but not necessarily an early driver

of peace.For example,it took time for an overarching Italian

identity to emerge following unification (Cronin, 1999). Likewise,

at the time of the US Constitutional Convention, people perceived

themselvesfirst-and-foremostas New Yorkers,North Car-

olinians, Virginians, and so on, not members of the United States

as a whole (Hendrickson,2003;Parent,2011).This overarching

US identity developed over time.

Second,our research suggests that security interdependence

often drives historicaltransformations toward unity,coopera-

tion,and peace.Parent (2011:p. 91) succinctly concludes that

“Switzerland is a country because foreign threats forged it into

one”.Concerns about Austrian domination drove Italian inte-

gration (Cronin,1999).Hendrickson (2003) makes a convin-

cing casethat concernsover externalthreatscontributed

substantially to the “peace pact” among the original13 United

States.As GeorgeWashington remarked,if Georgia,“with

powerful tribes of Indians in its rear, & the Spanish on its flank,

do not incline to embrace a strong generalGovernment,there

must,I should think,be either wickedness,or insanity in their

conduct” (Washington quoted in Parent,2011:p. 45).In fact,

Georgia was one of the first states to ratify the US Constitution.

In sum,when the history is known,a recurring theme is that a

common externalthreatis one factorthatcan facilitate the

formation of a peace system.This leads us to raise the question

by analogy whether common threats to humanity such as cli-

mate change,ecologicalcollapse,or globalpandemicscould

spur among globalneighbours the type ofunity,cooperation,

and peacefulpractices thatare the hallmark ofpeace systems

existing at other sociallevels (see Fig.4).

Third, anotherfactorthatmay give initialimpetusto the

developmentof a peace system is visionary peace-focused lea-

dership. Such leadership was clearly present at the founding o

United States among the Federalists as they pointed out the p

of anarchy and the benefits ofunification (Hendrickson,2003;

Parent,2011).The legendary peacemaker of the Iroquois,Dega-

nawidah,advocated a new vision with peace and unity at its co

and voiced the explicit goalof replacing chronic warfare with a

confederation,the League of Peace.In a similar vein and driven

by a vision ofabolishing future wars in Europe,Jean Monnet

(1978) and his colleagues conceptualised a new order with ce

tralised,supranationalinstitutions.Like Deganawidah,the peace

leadership ofMonnetand his contemporarieswascriticalin

promoting a transformation in thinking and acting thatsuc-

cessfully turned a continent away from war (Fry,2012).Monnet

not only gave the people and politicians ofEurope a vision of

peace,but also provided a plan on how to achieve the socio-

Fig. 4 A wounded planet is conveyed by Sphere within Sphere by Arnaldo

Pomodoro,1996, just outside the United Nations Headquarters in New

York. Extant peace systems demonstrate the human capacities to create

non-warring socialsystems and to solve common challenges through

collaboration.An understanding of peace systems holds promise for

facilitating cooperation and solidarity in addressing globalpandemics,

climate change,and ecosystem collapse.Reproduced with permission of

Douglas P.Fry;copyright © Douglas P.Fry,allrights reserved.

Fig. 5 Jean Monnet (1888–1979), avid promoter of European integration,

epitomises the type of visionary peace leadership sometimes seen in

peace systems that can unify hostile neighbours and guide them on a

new path away from the scourge of war.Reproduced with permission of

Douglas P.Fry;copyright © Douglas P.Fry,allrights reserved.

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 ARTICLE

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS |(2021) 8:17| https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8 7

positive reciprocity,and positive goals).

With the partial exception of ethnocentrism, war variables also

positively correlated with one another. All significant correlations

between peace and war variables were negative, with peace versus

war values and norms showing a very a strong negative correla-

tion. Additionally,peacesystemstend to havesignificantly

strongerpeace valuesand norms,whereasnon-peace systems

tend to have significantly stronger war values and norms.

Perhaps, once established, either war or peace orientations may

stabiliseamongneighbouringsocieties.However,over time

conditions ofwar among neighbours can be transformed into

non-warring relationships, such as among the Swiss cantons after

Switzerland was formed,Italian states and kingdoms after uni-

fication,or the tribes of Iroquoia after the creation of their con-

federacy (Archer,2003;Fry, 2006;Sponsel,2018).The Nordic

countries transitioned “from a region rife with warfare to an area

whose conflicts are ‘non-wars’embracing diplomatic solutions”

(Archer,2003:p. 8).

An important topic for future research would be the investi-

gation ofwhich features found in peace systems have been key

driversof transformationsovertime from warto peace.The

collection of longitudinaldata,when available,on the nature of

historicaltransformationswould be necessary to addressthis

topic.Some peace systems such as the ten Upper Xingu peoples,

the Montagnais-Naskapi-EastMain Cree,the Malaysian Orang

Asli, and the Nigiri Plateau tribes were already in operation when

early ethnographic information was gathered,so the historical

roots of the non-warringintergroup relationsprobablywill

remain obscure.However,historicaland ethnohistoricaldata do

existfor some cases such as the formation ofSwitzerland,the

United States,and the Iroquois confederacy.The findings of this

study lead to severalprovisionalobservations thatare ripe for

further historicalinvestigation.

First,it seems thata sense ofoverarching identity develops

gradually over time,becoming,as found in our study,a main-