Sonic Nozzle: Theory, Operation and Applications

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

|11

|3184

|98

AI Summary

This report provides an in-depth understanding of Sonic Nozzle, its theory, operation and applications. It includes the derivation of theoretical flow rate equation, graphs showing mass flow rate against inlet pressure and pressure ratio, and explains the advantages of Sonic Nozzles over subsonic flow-meters. Useful thermodynamic properties of air are also provided. The report is based on experiments conducted on a Sonic Nozzle unit and is word-processed.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

COURSEWORK BRIEF:

• THE SONIC NOZZLE (CRITICAL FLOW NOZZLE, CRITICAL FLOW VENTURI OR SONIC VENTURI)

CONSISTS OF A SMOOTH ROUNDED INLET SECTION CONVERGING TO A MINIMUM THROAT AREA AND

THEN DIVERGING ALONG A PRESSURE RECOVERY SECTION OR EXIT CONE (CONVERGING-DIVERGING

NOZZLE). AS A GAS ACCELERATES THROUGH THE NOZZLE, ITS VELOCITY INCREASES AND ITS

DENSITY DECREASES. THE MAXIMUM VELOCITY IS ACHIEVED AT THE THROAT, THE MINIMUM AREA,

WHERE IT REACHES THE DESIRED SPEED OF SOUND (MACH NO.=1).

• THE SONIC NOZZLE IS OPERATED BY PRESSURIZING THE INLET (PI) OR EVACUATING THE EXIT (PO).

THIS RATIO MAINTAINS THE NOZZLE IN A "CHOKED" OR "SONIC" STATE. IN THIS STATE, ONLY THE

UPSTREAM PRESSURE (PI) AND TEMPERATURE ARE INFLUENCING THE FLOW-RATE THROUGH

THE NOZZLE. THE FLOW-RATE THROUGH THE NOZZLE BECOMES NEARLY A LINEAR FUNCTION OF

THE INLET PRESSURE. DOUBLING THE INLET PRESSURE DOUBLES THE FLOW-RATE.

• THE SIMPLEST FLOW SYSTEM WOULD USE AN INLET PRESSURE REGULATOR TO CONTROL AIR

PRESSURE AND A THERMOCOUPLE TO MEASURE TEMPERATURE. ADJUSTING THE PRESSURE

REGULATOR WILL CHANGE AND MAINTAIN THE FLOW THROUGH THE NOZZLE.

• PRESSURE DIFFERENCES WITHIN A PIPING SYSTEM TRAVEL AT THE SPEED OF SOUND AND

GENERATE FLOW. DOWNSTREAM PRESSURE DISTURBANCES CANNOT MOVE UPSTREAM PAST THE

THROAT OF THE NOZZLE BECAUSE THE THROAT VELOCITY IS HIGHER AND IN THE OPPOSITE

DIRECTION. SINCE THESE PRESSURE DISTURBANCES CANNOT MOVE UPSTREAM PAST THE THROAT,

THEY CANNOT AFFECT THE VELOCITY OR THE DENSITY OF THE FLOW THROUGH THE NOZZLE. THIS

IS WHAT IS REFERRED TO AS A CHOKED OR SONIC STATE OF OPERATION. THIS IS ONE OF THE

GREATEST ADVANTAGES OF SONIC NOZZLES WHEN COMPARED TO SUBSONIC FLOW-METERS

(VENTURIS OR ORIFICE PLATES WHERE ANY CHANGE IN DOWNSTREAM PRESSURE WILL AFFECT

THE DIFFERENTIAL PRESSURE ACROSS THE FLOW-METER, WHICH IN TURN, AFFECTS THE FLOW).

• AS A RESULT, SONIC NOZZLES ARE IDEAL FOR APPLICATIONS WHERE STEADY INLET FLOW IS

REQUIRED EVEN THOUGH THERE IS PULSATING OR VARYING GAS CONSUMPTION DOWNSTREAM.

THEY ARE ALSO IDEAL AS FLOW LIMITERS SINCE WITH A FIXED UPSTREAM PRESSURE BOTH MASS

AND VOLUMETRIC FLOWS ARE FIXED.

• ACCURACY LEVELS OF ±0.25% OF READING OR BETTER CAN ROUTINELY BE ACHIEVED SINCE

THERE ARE NO MOVING PARTS.

• THE MAIN BODY OF THE REPORT SHOULD BE WORD-PROCESSES (HAND-WRITING NOT ACCEPTED!)

AND THE DATA SHOULD BE PRESENTED IN A TABLE, AND GRAPHS SHOULD BE COMPLETED IN EXCEL,

MINITAB OR MATLAB.

• DERIVE THEORETICAL FLOW RATE EQUATION AT THE CHOKED OR SONIC CONDITION (DISCHARGE

COEFFICIENT CAN BE NEGLIGIBLE). (20 MARKS)

• USING THE DATA FROM THE FIRST SET OF TESTS, PLOT GRAPH SHOWING THE MASS FLOW RATE

AGAINST THE INLET PRESSURE WITH COMPARISON TO THEORETICAL VALUE. (20 MARKS)

• DERIVE THE CRITICAL PRESSURE RATIO AT THE CHOKED OR SONIC CONDITION. (20 MARKS)

• USING THE DATA FROM THE SECOND SET OF TESTS, PLOT GRAPH SHOWING THE MASS FLOW RATE

AGAINST THE PRESSURE RATIO (PO/PI) WITH COMPARISON TO THEORETICAL VALUE AND CRITICAL

PRESSURE RATIO DERIVED. (20 MARKS)

• EXPLAIN WHY THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EXPERIMENTAL AND THEORETICAL VALUES EXISTS. (20

MARKS)

• MAKE SURE YOUR NAME, ID NO. AND GROUP NO. ON THE COVER SHEET.

• USEFUL THERMODYNAMIC PROPERTIES OF AIR:

Page i of iii

• THE SONIC NOZZLE (CRITICAL FLOW NOZZLE, CRITICAL FLOW VENTURI OR SONIC VENTURI)

CONSISTS OF A SMOOTH ROUNDED INLET SECTION CONVERGING TO A MINIMUM THROAT AREA AND

THEN DIVERGING ALONG A PRESSURE RECOVERY SECTION OR EXIT CONE (CONVERGING-DIVERGING

NOZZLE). AS A GAS ACCELERATES THROUGH THE NOZZLE, ITS VELOCITY INCREASES AND ITS

DENSITY DECREASES. THE MAXIMUM VELOCITY IS ACHIEVED AT THE THROAT, THE MINIMUM AREA,

WHERE IT REACHES THE DESIRED SPEED OF SOUND (MACH NO.=1).

• THE SONIC NOZZLE IS OPERATED BY PRESSURIZING THE INLET (PI) OR EVACUATING THE EXIT (PO).

THIS RATIO MAINTAINS THE NOZZLE IN A "CHOKED" OR "SONIC" STATE. IN THIS STATE, ONLY THE

UPSTREAM PRESSURE (PI) AND TEMPERATURE ARE INFLUENCING THE FLOW-RATE THROUGH

THE NOZZLE. THE FLOW-RATE THROUGH THE NOZZLE BECOMES NEARLY A LINEAR FUNCTION OF

THE INLET PRESSURE. DOUBLING THE INLET PRESSURE DOUBLES THE FLOW-RATE.

• THE SIMPLEST FLOW SYSTEM WOULD USE AN INLET PRESSURE REGULATOR TO CONTROL AIR

PRESSURE AND A THERMOCOUPLE TO MEASURE TEMPERATURE. ADJUSTING THE PRESSURE

REGULATOR WILL CHANGE AND MAINTAIN THE FLOW THROUGH THE NOZZLE.

• PRESSURE DIFFERENCES WITHIN A PIPING SYSTEM TRAVEL AT THE SPEED OF SOUND AND

GENERATE FLOW. DOWNSTREAM PRESSURE DISTURBANCES CANNOT MOVE UPSTREAM PAST THE

THROAT OF THE NOZZLE BECAUSE THE THROAT VELOCITY IS HIGHER AND IN THE OPPOSITE

DIRECTION. SINCE THESE PRESSURE DISTURBANCES CANNOT MOVE UPSTREAM PAST THE THROAT,

THEY CANNOT AFFECT THE VELOCITY OR THE DENSITY OF THE FLOW THROUGH THE NOZZLE. THIS

IS WHAT IS REFERRED TO AS A CHOKED OR SONIC STATE OF OPERATION. THIS IS ONE OF THE

GREATEST ADVANTAGES OF SONIC NOZZLES WHEN COMPARED TO SUBSONIC FLOW-METERS

(VENTURIS OR ORIFICE PLATES WHERE ANY CHANGE IN DOWNSTREAM PRESSURE WILL AFFECT

THE DIFFERENTIAL PRESSURE ACROSS THE FLOW-METER, WHICH IN TURN, AFFECTS THE FLOW).

• AS A RESULT, SONIC NOZZLES ARE IDEAL FOR APPLICATIONS WHERE STEADY INLET FLOW IS

REQUIRED EVEN THOUGH THERE IS PULSATING OR VARYING GAS CONSUMPTION DOWNSTREAM.

THEY ARE ALSO IDEAL AS FLOW LIMITERS SINCE WITH A FIXED UPSTREAM PRESSURE BOTH MASS

AND VOLUMETRIC FLOWS ARE FIXED.

• ACCURACY LEVELS OF ±0.25% OF READING OR BETTER CAN ROUTINELY BE ACHIEVED SINCE

THERE ARE NO MOVING PARTS.

• THE MAIN BODY OF THE REPORT SHOULD BE WORD-PROCESSES (HAND-WRITING NOT ACCEPTED!)

AND THE DATA SHOULD BE PRESENTED IN A TABLE, AND GRAPHS SHOULD BE COMPLETED IN EXCEL,

MINITAB OR MATLAB.

• DERIVE THEORETICAL FLOW RATE EQUATION AT THE CHOKED OR SONIC CONDITION (DISCHARGE

COEFFICIENT CAN BE NEGLIGIBLE). (20 MARKS)

• USING THE DATA FROM THE FIRST SET OF TESTS, PLOT GRAPH SHOWING THE MASS FLOW RATE

AGAINST THE INLET PRESSURE WITH COMPARISON TO THEORETICAL VALUE. (20 MARKS)

• DERIVE THE CRITICAL PRESSURE RATIO AT THE CHOKED OR SONIC CONDITION. (20 MARKS)

• USING THE DATA FROM THE SECOND SET OF TESTS, PLOT GRAPH SHOWING THE MASS FLOW RATE

AGAINST THE PRESSURE RATIO (PO/PI) WITH COMPARISON TO THEORETICAL VALUE AND CRITICAL

PRESSURE RATIO DERIVED. (20 MARKS)

• EXPLAIN WHY THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EXPERIMENTAL AND THEORETICAL VALUES EXISTS. (20

MARKS)

• MAKE SURE YOUR NAME, ID NO. AND GROUP NO. ON THE COVER SHEET.

• USEFUL THERMODYNAMIC PROPERTIES OF AIR:

Page i of iii

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

GAS CONSTANT OF AIR: R = 0.2871 KJ/(KGK)

RATIO OF SPECIFIC HEAT:

= 1.4 (CP/CV)

SPECIFIC HEAT OF AIR AT CONSTANT PRESSURE: CP = 1.005 KJ//(KGK)

• REFERENCE: CHAPTER 17_INTRODUCTION TO COMPRESSIBLE FLOW IN “THERMODYNAMICS: AN

ENGINEERING APPROACH”, CENGEL, Y. A. ET. AL.

Hand-in date is Monday, 18th of December, 2017.

Only online submission through turnitin is

accepted. Scan your handwriting document if

necessary, and upload it. Don’t photoshoot it.

Page ii of iii

RATIO OF SPECIFIC HEAT:

= 1.4 (CP/CV)

SPECIFIC HEAT OF AIR AT CONSTANT PRESSURE: CP = 1.005 KJ//(KGK)

• REFERENCE: CHAPTER 17_INTRODUCTION TO COMPRESSIBLE FLOW IN “THERMODYNAMICS: AN

ENGINEERING APPROACH”, CENGEL, Y. A. ET. AL.

Hand-in date is Monday, 18th of December, 2017.

Only online submission through turnitin is

accepted. Scan your handwriting document if

necessary, and upload it. Don’t photoshoot it.

Page ii of iii

MARKING CRITERIA:

COURSEWORK WILL BE MARKED ACCORDING TO THE FOLLOWING UNIVERSITY CRITERIA.

90-100%: a range of marks consistent with a first where the work is exceptional in all areas;

80-89%: a range of marks consistent with a first where the work is exceptional in most areas.

70-79%: a range of marks consistent with a first. Work which shows excellent content, organisation and presentation,

reasoning and originality; evidence of independent reading and thinking and a clear and authoritative grasp of

theoretical positions; ability to sustain an argument, to think analytically and/or critically and to synthesise material

effectively.

60-69%: a range of marks consistent with an upper second. Well-organised and lucid coverage of the main points in

an answer; intelligent interpretation and confident use of evidence, examples and references; clear evidence of critical

judgement in selecting, ordering and analysing content; demonstrates some ability to synthesise material and to

construct responses, which reveal insight and may offer some originality.

50-59%: a range of marks consistent with lower second; shows a grasp of the main issues and uses relevant

materials in a generally business-like approach, restricted evidence of additional reading; possible unevenness in

structure of answers and failure to understand the more subtle points: some critical analysis and a modest degree of

insight should be present.

40-49%: a range of marks which is consistent with third class; demonstrates limited understanding with no enrichment

of the basic course material presented in classes; superficial lines of argument and muddled presentation; little or no

attempt to relate issues to a broader framework; lower end of the range equates to a minimum or threshold pass.

35-39%: achieves many of the learning outcomes required for a mark of 40% but falls short in one or more areas.

30-34%: a fail; may achieve some learning outcomes but falls short in most areas; shows considerable lack of

understanding of basic course material and little evidence of research.

0-29%: a fail; basic factual errors of considerable magnitude showing little understanding of basic course material;

falls substantially short of the learning outcomes for compensation.

MARKING SCHEME:

SEE COURSEWORK BRIEF FOR DETAILS ON HOW MARKS ARE ALLOCATED.

BEGIN YOUR WORK ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE IF YOU ARE WORD PROCESSING YOUR COURSEWORK

Page iii of iii

COURSEWORK WILL BE MARKED ACCORDING TO THE FOLLOWING UNIVERSITY CRITERIA.

90-100%: a range of marks consistent with a first where the work is exceptional in all areas;

80-89%: a range of marks consistent with a first where the work is exceptional in most areas.

70-79%: a range of marks consistent with a first. Work which shows excellent content, organisation and presentation,

reasoning and originality; evidence of independent reading and thinking and a clear and authoritative grasp of

theoretical positions; ability to sustain an argument, to think analytically and/or critically and to synthesise material

effectively.

60-69%: a range of marks consistent with an upper second. Well-organised and lucid coverage of the main points in

an answer; intelligent interpretation and confident use of evidence, examples and references; clear evidence of critical

judgement in selecting, ordering and analysing content; demonstrates some ability to synthesise material and to

construct responses, which reveal insight and may offer some originality.

50-59%: a range of marks consistent with lower second; shows a grasp of the main issues and uses relevant

materials in a generally business-like approach, restricted evidence of additional reading; possible unevenness in

structure of answers and failure to understand the more subtle points: some critical analysis and a modest degree of

insight should be present.

40-49%: a range of marks which is consistent with third class; demonstrates limited understanding with no enrichment

of the basic course material presented in classes; superficial lines of argument and muddled presentation; little or no

attempt to relate issues to a broader framework; lower end of the range equates to a minimum or threshold pass.

35-39%: achieves many of the learning outcomes required for a mark of 40% but falls short in one or more areas.

30-34%: a fail; may achieve some learning outcomes but falls short in most areas; shows considerable lack of

understanding of basic course material and little evidence of research.

0-29%: a fail; basic factual errors of considerable magnitude showing little understanding of basic course material;

falls substantially short of the learning outcomes for compensation.

MARKING SCHEME:

SEE COURSEWORK BRIEF FOR DETAILS ON HOW MARKS ARE ALLOCATED.

BEGIN YOUR WORK ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE IF YOU ARE WORD PROCESSING YOUR COURSEWORK

Page iii of iii

UNIVERSITY AFFILIATION

DEPARTMENT OR FACULTY

ADVANCED THERMOFLUIDS

COURSE CODE

LAB REPORT

STUDENT NAME

STUDENT ID

DATE OF SUBMISSION

INTRODUCTION

Page 1 of 8

DEPARTMENT OR FACULTY

ADVANCED THERMOFLUIDS

COURSE CODE

LAB REPORT

STUDENT NAME

STUDENT ID

DATE OF SUBMISSION

INTRODUCTION

Page 1 of 8

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

A nozzle is a tube of varying cross-sectional area that increases the speed of an outflow and controls

its direction and shape. It generates forces associated to the change in flow momentum. It consists of

a smooth rounded inlet section. The fluid that flows tends to accelerate at the nozzle such that the

velocity of the fluid increases while its density decreases. At the throat, the maximum velocity is

achieved at the minimum area where it reaches the desired speed of sound. The sonic nozzles are

ideal for application where steady inlet flow is required even though there is pulsating or varying gas

consumption downstream. They are ideal as flow limiters owing to the fixed upstream pressure for

both mass and volumetric flows which tend to be fixed. A rise in kinetic energy accompanies a

decrease in the pressure of the fluids and is undertaken by an appropriate variation in the flow area.

The device operates on the principle that the flow of gases accelerates to the critical velocity at the

throat of the nozzle where the gas’ mass flow rate through the venture nozzle is at its peak.

Some useful thermodynamic properties of air:

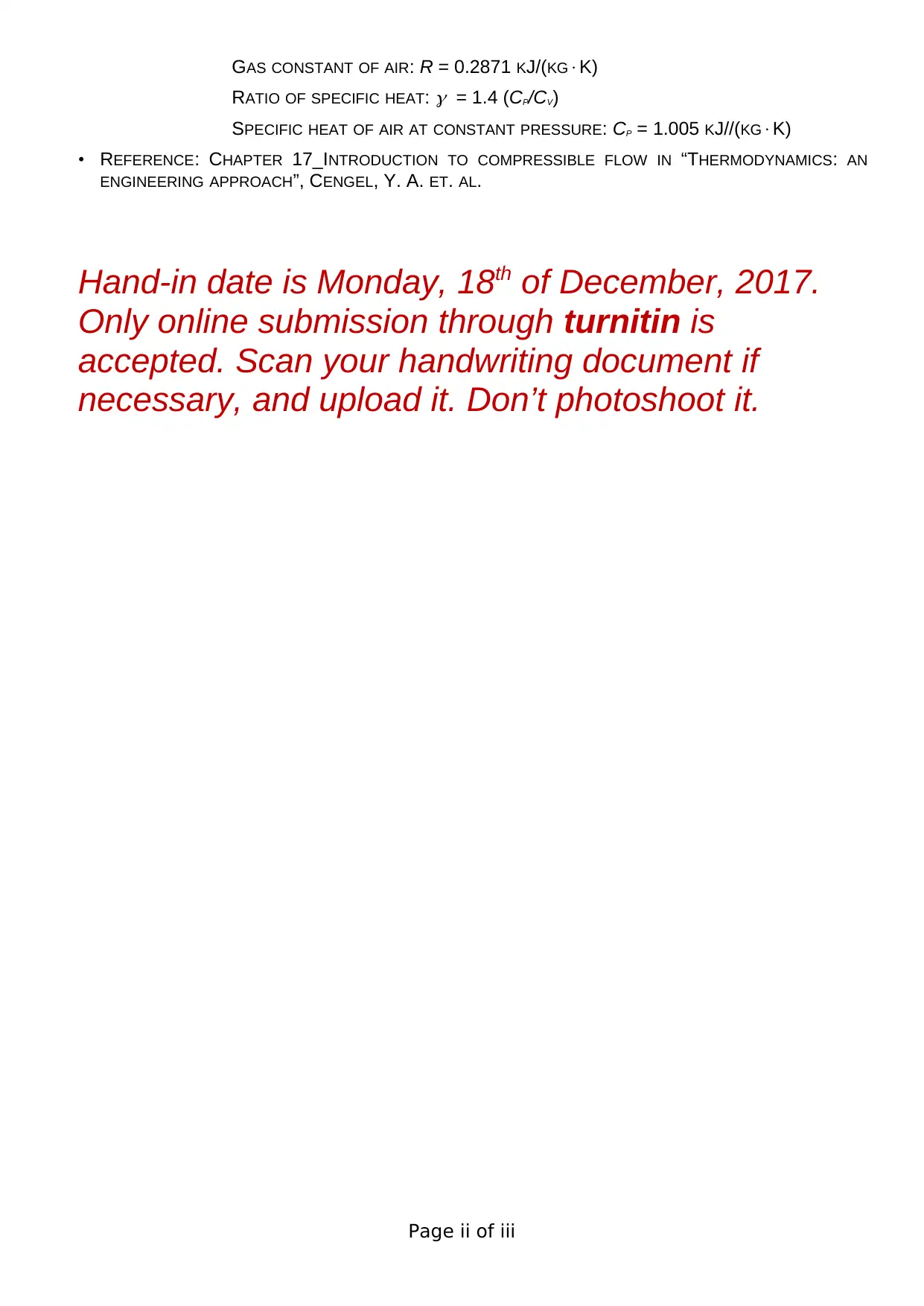

Table 1 Reference: Cengel, et all, n.d

Property Value

1. Gas constant of air (R) 0.2871kj/(Kg.K)

2. Ratio of Specific Heat (γ) 1.4 (Cp/Cv)

3. Specific Heat of air at constant Pressure (Cp) 1.005 kj/kg.K

EXPERIMENT 1

Effect of inlet pressure of the mass flow rate compared to the theoretical prediction.

(i) The inlet pressure was regulated to about 700-900 kN/m2 using a pressure regulator. Prior

to this, the inlet air throttle value is tightly closed.

(ii) The valves are later opened fully. The back pressure was measured to approximately 20-

50 kN/M2 and the necessary observations of the inlet and outlet pressures and

temperatures were recorded alongside the mass flow rates.

(iii) The pressure regulator was adjusted reducing the inlet pressure just before the back-

pressure valve was regulated so as to attain the initial back pressure as highlighted above.

RESULTS

Data recorded

Temperature (K) = Temperature (C) +273

Atmospheric pressure = 100.6 KPa

Absolute pressure= gauge pressure + atmospheric pressure

Sonic nozzle unit Operation sheet

Date: 20 November 2017 Group: 2 Atmospheric pressure: 100.6 KPa

Nozzle: A, All pressure shown in kPa

Pipe inlet diameter: 7

mm

Throat diameter: 2.02

mm

Inlet Ti K 291.9 292 292.1 292.3 292.3 292.4 292.4 292.4

5

292.5

0

292.60

Outlet To K 290.55 290.90 291.20 291.30 291.50 291.7 291.8 292 292.2 292.30

Page 2 of 8

its direction and shape. It generates forces associated to the change in flow momentum. It consists of

a smooth rounded inlet section. The fluid that flows tends to accelerate at the nozzle such that the

velocity of the fluid increases while its density decreases. At the throat, the maximum velocity is

achieved at the minimum area where it reaches the desired speed of sound. The sonic nozzles are

ideal for application where steady inlet flow is required even though there is pulsating or varying gas

consumption downstream. They are ideal as flow limiters owing to the fixed upstream pressure for

both mass and volumetric flows which tend to be fixed. A rise in kinetic energy accompanies a

decrease in the pressure of the fluids and is undertaken by an appropriate variation in the flow area.

The device operates on the principle that the flow of gases accelerates to the critical velocity at the

throat of the nozzle where the gas’ mass flow rate through the venture nozzle is at its peak.

Some useful thermodynamic properties of air:

Table 1 Reference: Cengel, et all, n.d

Property Value

1. Gas constant of air (R) 0.2871kj/(Kg.K)

2. Ratio of Specific Heat (γ) 1.4 (Cp/Cv)

3. Specific Heat of air at constant Pressure (Cp) 1.005 kj/kg.K

EXPERIMENT 1

Effect of inlet pressure of the mass flow rate compared to the theoretical prediction.

(i) The inlet pressure was regulated to about 700-900 kN/m2 using a pressure regulator. Prior

to this, the inlet air throttle value is tightly closed.

(ii) The valves are later opened fully. The back pressure was measured to approximately 20-

50 kN/M2 and the necessary observations of the inlet and outlet pressures and

temperatures were recorded alongside the mass flow rates.

(iii) The pressure regulator was adjusted reducing the inlet pressure just before the back-

pressure valve was regulated so as to attain the initial back pressure as highlighted above.

RESULTS

Data recorded

Temperature (K) = Temperature (C) +273

Atmospheric pressure = 100.6 KPa

Absolute pressure= gauge pressure + atmospheric pressure

Sonic nozzle unit Operation sheet

Date: 20 November 2017 Group: 2 Atmospheric pressure: 100.6 KPa

Nozzle: A, All pressure shown in kPa

Pipe inlet diameter: 7

mm

Throat diameter: 2.02

mm

Inlet Ti K 291.9 292 292.1 292.3 292.3 292.4 292.4 292.4

5

292.5

0

292.60

Outlet To K 290.55 290.90 291.20 291.30 291.50 291.7 291.8 292 292.2 292.30

Page 2 of 8

0 0

Inlet Pi Gaug

e

700 650 600 550 500 450 400 350 300 250

Abs 800.6 750.6 700.6 650.6 600.7 550.7 500.6 450.6 400.6 350.6

Outlet Po Gaug

e

40 40 40 40 40 40 40 40 40 40

Abs 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6

Air flow g/s 5.9 5.4 5.1 4.8 4.4 4 3.6 3.3 2.9 2.6

EXPERIMENT 2

Effects of back pressure on the mass flow rate as compared to the prediction done theoretically

Procedure

(i) The inlet pressure was regulated to about 700-900 kN/m2 using a pressure regulator. Prior

to this, the inlet air throttle value is tightly closed.

(ii) The valves are later opened fully. The back pressure was measured to approximately 20-

50 kN/M2 and the necessary observations of the inlet and outlet pressures and

temperatures were recorded alongside the mass flow rates.

(iii) The pressure regulator was adjusted reducing the inlet pressure just before the back-

pressure valve was regulated so as to attain the initial back pressure as highlighted above.

Sonic Nozzle unit Operation sh

Date: 20th November 2017 Group: 2 Atmospheric Pressure: k

100

Nozzle: A, All pressures shown in kPa Pipe Inlet Diameter: 7mm, Throat Diameter:2.02m

Inlet T1 K 243.30 243.35 243.40 243.40 243.50 243.40 243.60 243.45 243.55 243.

Outlet

To

K 292 292.3 292.4 292.50 292.60 292.80 292.80 292/90 293 293.

Inlet P1 Gauge 650 650 650 650 650 650 650 650 650 650

Abs

Outlet

Po

Gauge 60 100 140 180 220 260 300 340 380 420

Page 3 of 8

Inlet Pi Gaug

e

700 650 600 550 500 450 400 350 300 250

Abs 800.6 750.6 700.6 650.6 600.7 550.7 500.6 450.6 400.6 350.6

Outlet Po Gaug

e

40 40 40 40 40 40 40 40 40 40

Abs 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6 140.6

Air flow g/s 5.9 5.4 5.1 4.8 4.4 4 3.6 3.3 2.9 2.6

EXPERIMENT 2

Effects of back pressure on the mass flow rate as compared to the prediction done theoretically

Procedure

(i) The inlet pressure was regulated to about 700-900 kN/m2 using a pressure regulator. Prior

to this, the inlet air throttle value is tightly closed.

(ii) The valves are later opened fully. The back pressure was measured to approximately 20-

50 kN/M2 and the necessary observations of the inlet and outlet pressures and

temperatures were recorded alongside the mass flow rates.

(iii) The pressure regulator was adjusted reducing the inlet pressure just before the back-

pressure valve was regulated so as to attain the initial back pressure as highlighted above.

Sonic Nozzle unit Operation sh

Date: 20th November 2017 Group: 2 Atmospheric Pressure: k

100

Nozzle: A, All pressures shown in kPa Pipe Inlet Diameter: 7mm, Throat Diameter:2.02m

Inlet T1 K 243.30 243.35 243.40 243.40 243.50 243.40 243.60 243.45 243.55 243.

Outlet

To

K 292 292.3 292.4 292.50 292.60 292.80 292.80 292/90 293 293.

Inlet P1 Gauge 650 650 650 650 650 650 650 650 650 650

Abs

Outlet

Po

Gauge 60 100 140 180 220 260 300 340 380 420

Page 3 of 8

Abs

Airflow g/s 5.4 5.4 5.45 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.4

(i) Derive the theoretical flow rate equation at the choked or sonic condition (discharge

coefficient can be negligible).

The mass flow rate is given by

The velocity of the flow is related to the static and stagnation enthalpies,

And

The mass flow rate is given as,

The ideal gas relations are given as,

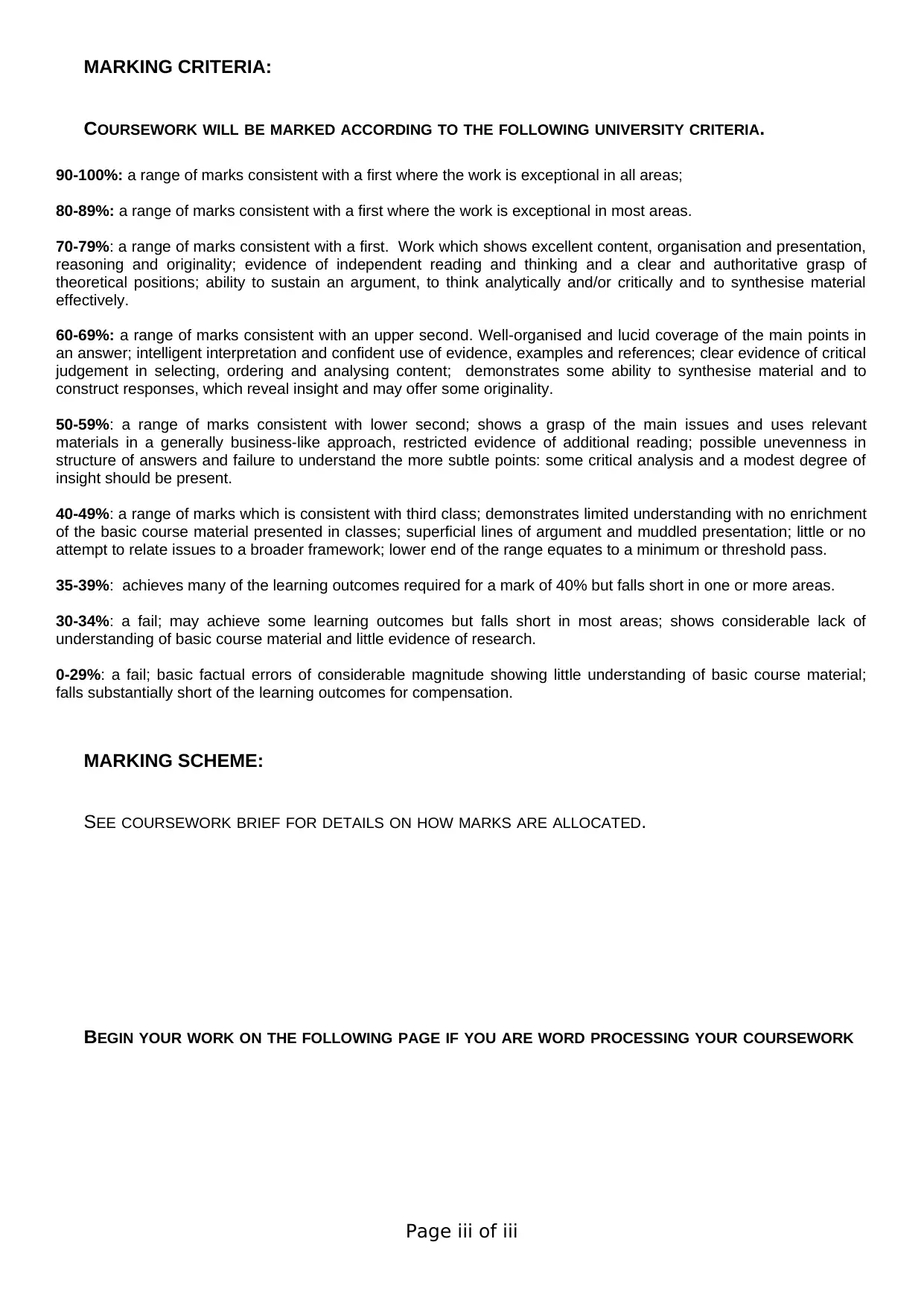

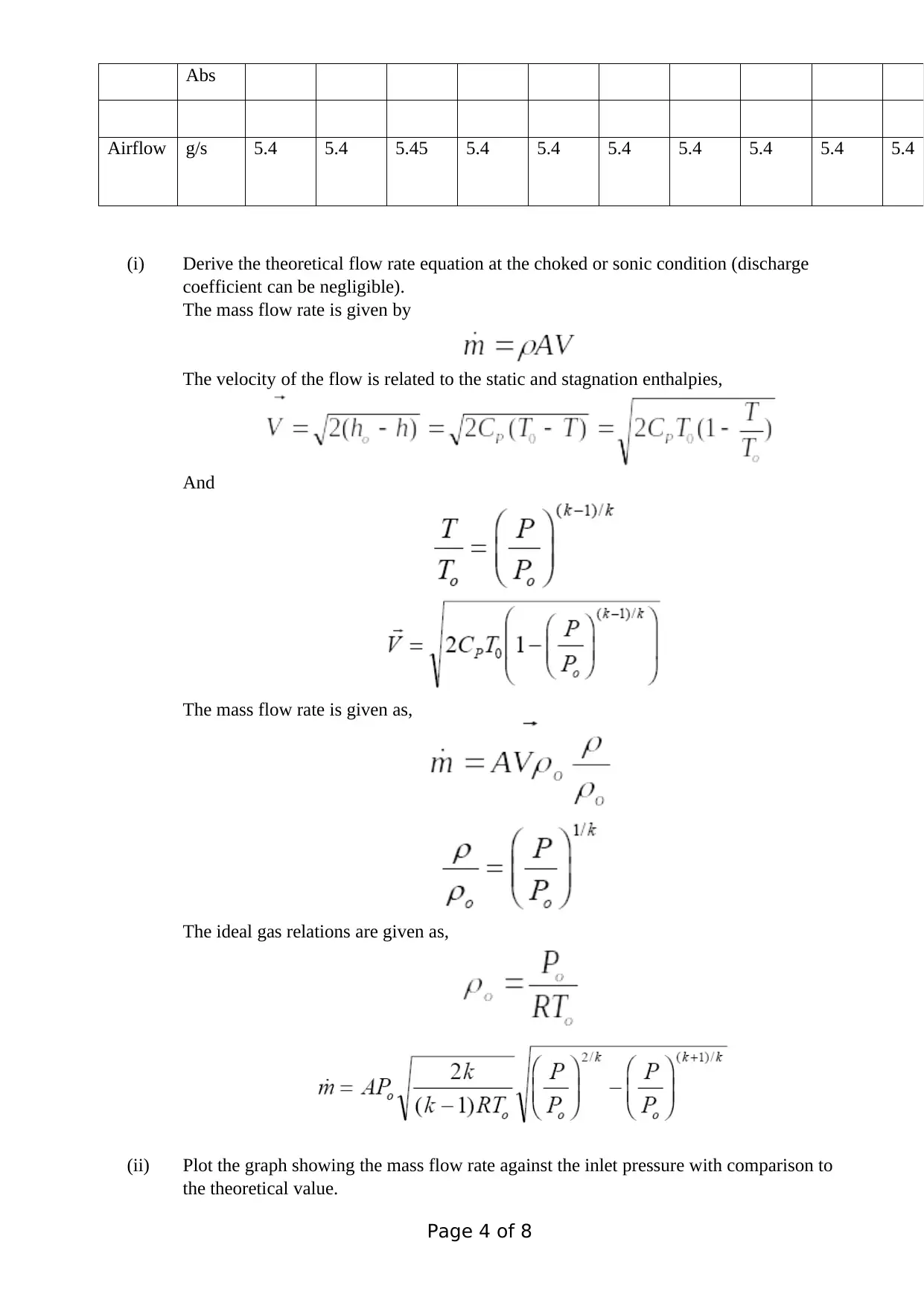

(ii) Plot the graph showing the mass flow rate against the inlet pressure with comparison to

the theoretical value.

Page 4 of 8

Airflow g/s 5.4 5.4 5.45 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.4

(i) Derive the theoretical flow rate equation at the choked or sonic condition (discharge

coefficient can be negligible).

The mass flow rate is given by

The velocity of the flow is related to the static and stagnation enthalpies,

And

The mass flow rate is given as,

The ideal gas relations are given as,

(ii) Plot the graph showing the mass flow rate against the inlet pressure with comparison to

the theoretical value.

Page 4 of 8

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

(iii) Derive the critical pressure ratio at the chocked or sonic condition.

Enthalpy ho = h + v ²

2 where ho is a constant

Implying that, ho = h1 + v12

2 = h2 + v22

2

The nozzle velocity v2 is thus calculated as follows;

v2 = √ 2 ( h1−h2 ) +v12

At stagnated conditions v1 = 0

Therefore ho = h1 and thus v2 = √ 2 ( h0−h2 )

For a fluid with constant specific heats,

P = ρRT and h = CpT

Substituting for the value of velocity in the above equation

v2 = √ 2C p ( T 0−T 2 ) = √2C p T0 (1− T2

T 0 )

But remember C p= kR

k−1 and the specific heat ratio k = Cp

Cv

Page 5 of 8

200 300 400 500 600 700 800

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

f(x) = 0.0072969696969697 x + 0.733939393939394

R² = 0.998358126721763

Mass flow rate Vs Inlet Pressure

Air flow

Linear (Air flow)

Linear (Air flow)

Inlet Pressure

Air Flow (g/s)

Enthalpy ho = h + v ²

2 where ho is a constant

Implying that, ho = h1 + v12

2 = h2 + v22

2

The nozzle velocity v2 is thus calculated as follows;

v2 = √ 2 ( h1−h2 ) +v12

At stagnated conditions v1 = 0

Therefore ho = h1 and thus v2 = √ 2 ( h0−h2 )

For a fluid with constant specific heats,

P = ρRT and h = CpT

Substituting for the value of velocity in the above equation

v2 = √ 2C p ( T 0−T 2 ) = √2C p T0 (1− T2

T 0 )

But remember C p= kR

k−1 and the specific heat ratio k = Cp

Cv

Page 5 of 8

200 300 400 500 600 700 800

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

f(x) = 0.0072969696969697 x + 0.733939393939394

R² = 0.998358126721763

Mass flow rate Vs Inlet Pressure

Air flow

Linear (Air flow)

Linear (Air flow)

Inlet Pressure

Air Flow (g/s)

According to general isotropy,

T1

T2

= ( P1

P2

¿^ k−1

k

Implying that T2

T0

= ( P2

P0

¿^ k−1

k and therefore v2 = √ 2C p T0 ( 1− T2

T 0 ) is evaluated to get

v2 = √ 2 kR

k −1 T 0 ( 1− P2

P0 )^ k−1

k

The above equation represents the exit velocity for an isentropic nozzle

Maximum theoretical exit velocity is achieved when P2

P0

= 0

Therefore, v2max = √ 2 kR

k −1 T 0

Recall that ho = h + v ²

2

Making the assumption that h = CpT implying that CpT0 = CpT + v ²

2

Making T0 the subject of the formula, T0 = T + v ²

2C p

T0

T = 1 + v ²

2C p T implying that T0

T = 1 +

v ²

2 kRT

k −1

But a2 = kRT and Mach number M = v

a

Therefore T0

T = 1 + k−1

2 × v ²

a ² thus T0

T = 1 + k−1

2 × M ²

Note that the stagnation temperature does not change in an adiabatic process.

Also P0

P = ( T0

T ¿^ k

k−1 implying that P0

P = (1 + k−1

2 M2 ¿ ^ k

k−1

And thus ρ0

ρ = ( T0

T ¿^ 1

k−1 implying that ρ0

ρ = (1 + k−1

2 M2 ¿ ^ 1

k−1

Critical pressure ratio is thus calculated as shown below

P0

P = (1 + 1

2 (k – 1) M2) ^ k

k−1 (Heming et al., 2012, p. 740)

Page 6 of 8

T1

T2

= ( P1

P2

¿^ k−1

k

Implying that T2

T0

= ( P2

P0

¿^ k−1

k and therefore v2 = √ 2C p T0 ( 1− T2

T 0 ) is evaluated to get

v2 = √ 2 kR

k −1 T 0 ( 1− P2

P0 )^ k−1

k

The above equation represents the exit velocity for an isentropic nozzle

Maximum theoretical exit velocity is achieved when P2

P0

= 0

Therefore, v2max = √ 2 kR

k −1 T 0

Recall that ho = h + v ²

2

Making the assumption that h = CpT implying that CpT0 = CpT + v ²

2

Making T0 the subject of the formula, T0 = T + v ²

2C p

T0

T = 1 + v ²

2C p T implying that T0

T = 1 +

v ²

2 kRT

k −1

But a2 = kRT and Mach number M = v

a

Therefore T0

T = 1 + k−1

2 × v ²

a ² thus T0

T = 1 + k−1

2 × M ²

Note that the stagnation temperature does not change in an adiabatic process.

Also P0

P = ( T0

T ¿^ k

k−1 implying that P0

P = (1 + k−1

2 M2 ¿ ^ k

k−1

And thus ρ0

ρ = ( T0

T ¿^ 1

k−1 implying that ρ0

ρ = (1 + k−1

2 M2 ¿ ^ 1

k−1

Critical pressure ratio is thus calculated as shown below

P0

P = (1 + 1

2 (k – 1) M2) ^ k

k−1 (Heming et al., 2012, p. 740)

Page 6 of 8

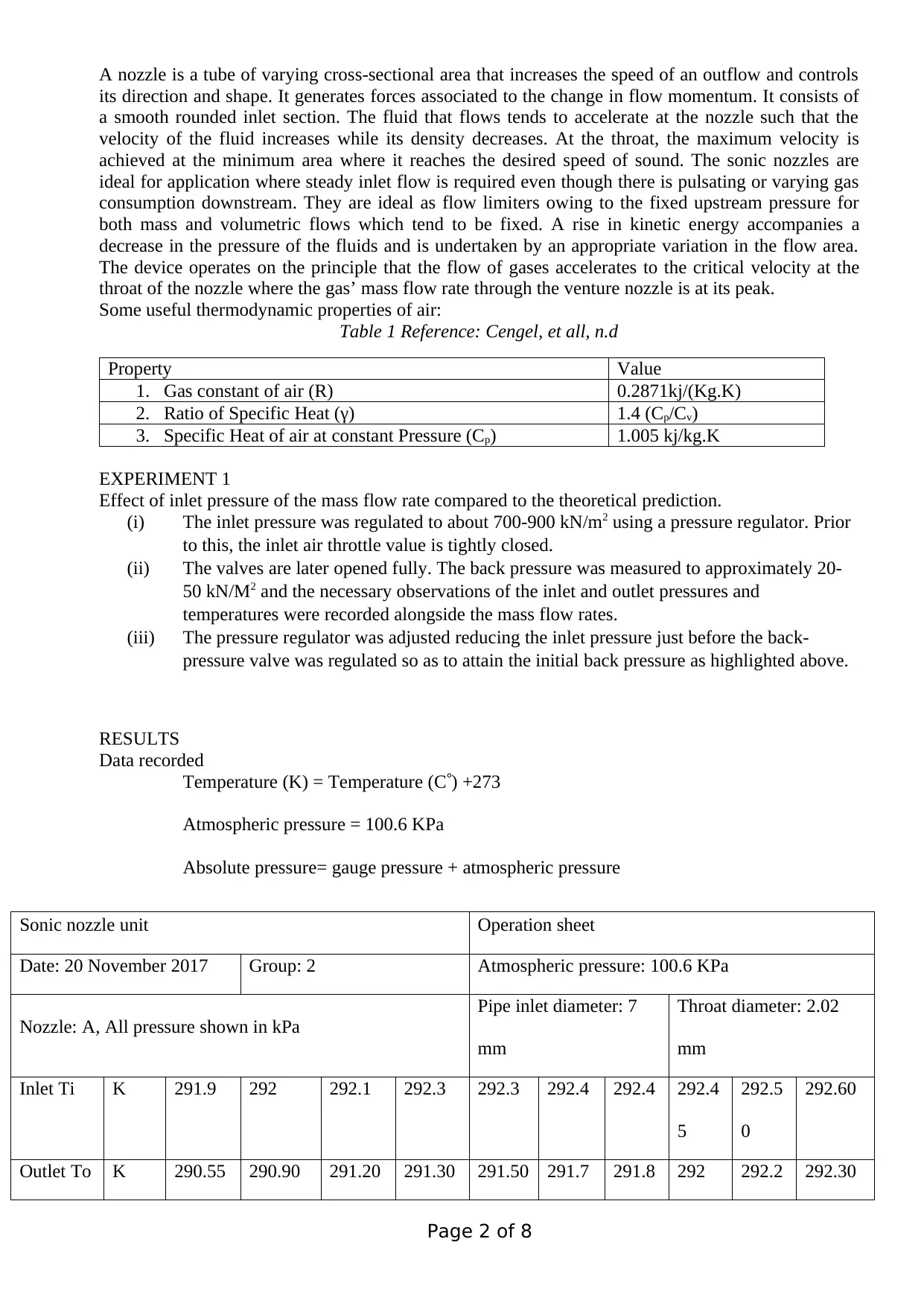

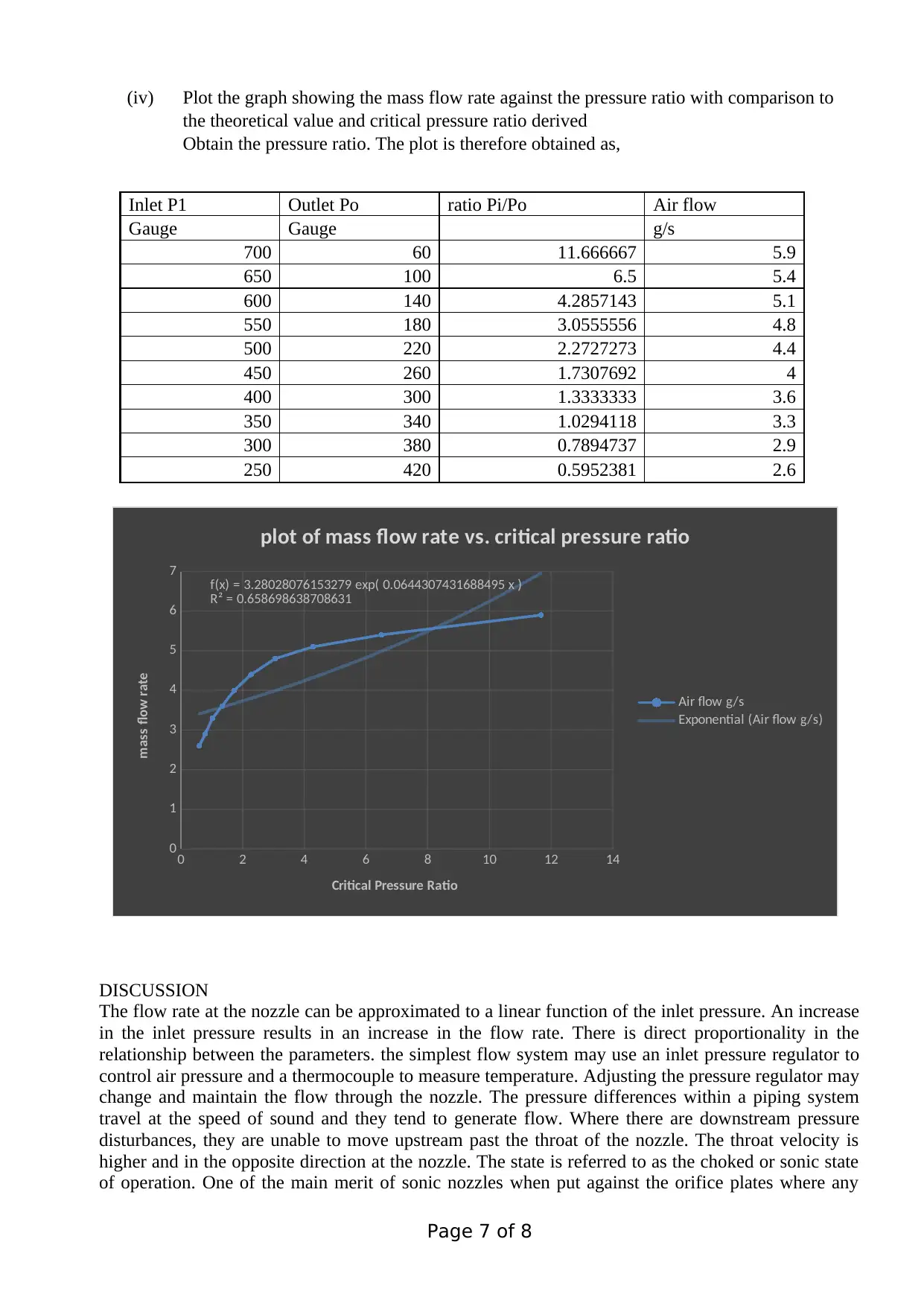

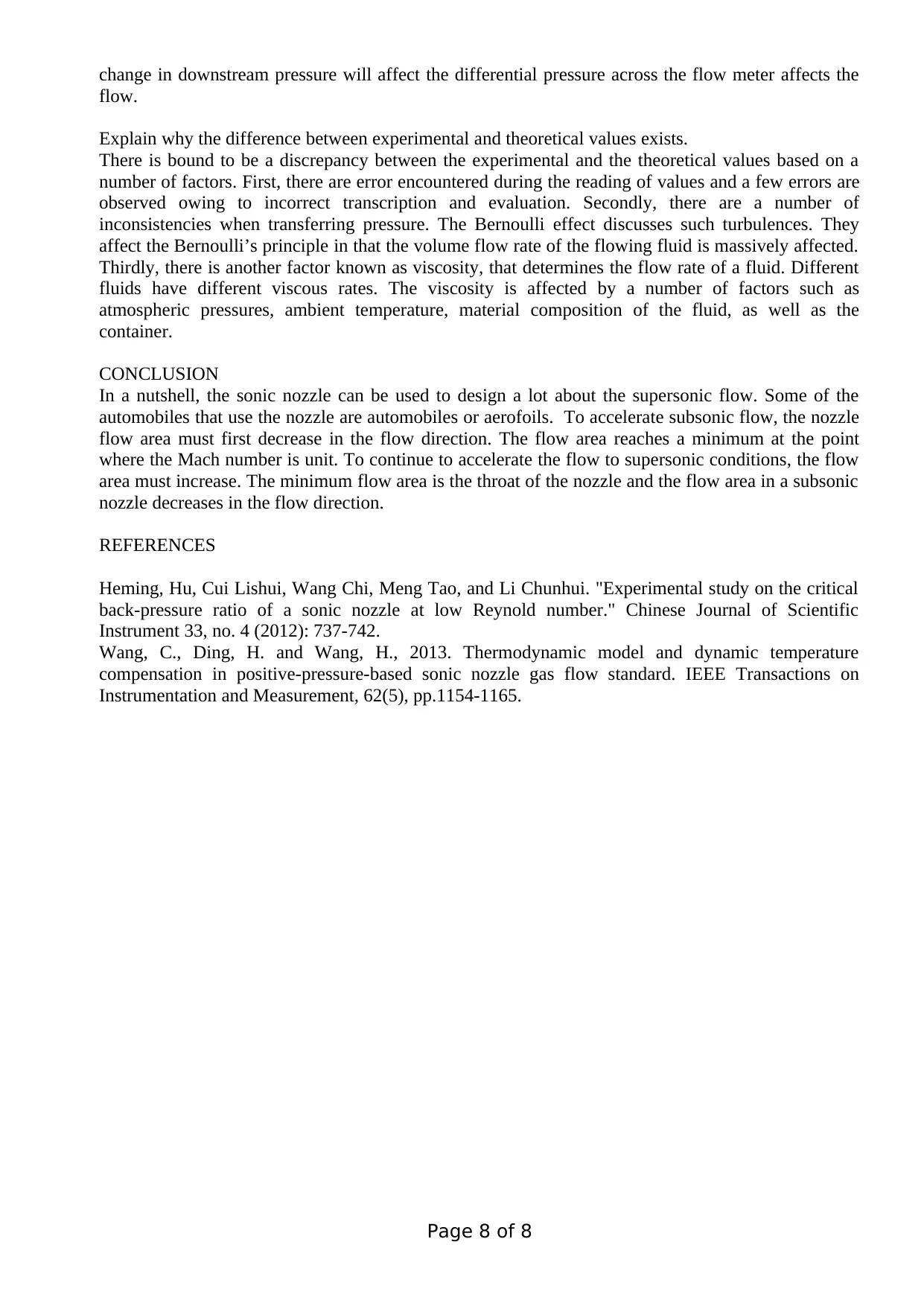

(iv) Plot the graph showing the mass flow rate against the pressure ratio with comparison to

the theoretical value and critical pressure ratio derived

Obtain the pressure ratio. The plot is therefore obtained as,

Inlet P1 Outlet Po ratio Pi/Po Air flow

Gauge Gauge g/s

700 60 11.666667 5.9

650 100 6.5 5.4

600 140 4.2857143 5.1

550 180 3.0555556 4.8

500 220 2.2727273 4.4

450 260 1.7307692 4

400 300 1.3333333 3.6

350 340 1.0294118 3.3

300 380 0.7894737 2.9

250 420 0.5952381 2.6

DISCUSSION

The flow rate at the nozzle can be approximated to a linear function of the inlet pressure. An increase

in the inlet pressure results in an increase in the flow rate. There is direct proportionality in the

relationship between the parameters. the simplest flow system may use an inlet pressure regulator to

control air pressure and a thermocouple to measure temperature. Adjusting the pressure regulator may

change and maintain the flow through the nozzle. The pressure differences within a piping system

travel at the speed of sound and they tend to generate flow. Where there are downstream pressure

disturbances, they are unable to move upstream past the throat of the nozzle. The throat velocity is

higher and in the opposite direction at the nozzle. The state is referred to as the choked or sonic state

of operation. One of the main merit of sonic nozzles when put against the orifice plates where any

Page 7 of 8

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

f(x) = 3.28028076153279 exp( 0.0644307431688495 x )

R² = 0.658698638708631

plot of mass flow rate vs. critical pressure ratio

Air flow g/s

Exponential (Air flow g/s)

Critical Pressure Ratio

mass flow rate

the theoretical value and critical pressure ratio derived

Obtain the pressure ratio. The plot is therefore obtained as,

Inlet P1 Outlet Po ratio Pi/Po Air flow

Gauge Gauge g/s

700 60 11.666667 5.9

650 100 6.5 5.4

600 140 4.2857143 5.1

550 180 3.0555556 4.8

500 220 2.2727273 4.4

450 260 1.7307692 4

400 300 1.3333333 3.6

350 340 1.0294118 3.3

300 380 0.7894737 2.9

250 420 0.5952381 2.6

DISCUSSION

The flow rate at the nozzle can be approximated to a linear function of the inlet pressure. An increase

in the inlet pressure results in an increase in the flow rate. There is direct proportionality in the

relationship between the parameters. the simplest flow system may use an inlet pressure regulator to

control air pressure and a thermocouple to measure temperature. Adjusting the pressure regulator may

change and maintain the flow through the nozzle. The pressure differences within a piping system

travel at the speed of sound and they tend to generate flow. Where there are downstream pressure

disturbances, they are unable to move upstream past the throat of the nozzle. The throat velocity is

higher and in the opposite direction at the nozzle. The state is referred to as the choked or sonic state

of operation. One of the main merit of sonic nozzles when put against the orifice plates where any

Page 7 of 8

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

f(x) = 3.28028076153279 exp( 0.0644307431688495 x )

R² = 0.658698638708631

plot of mass flow rate vs. critical pressure ratio

Air flow g/s

Exponential (Air flow g/s)

Critical Pressure Ratio

mass flow rate

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

change in downstream pressure will affect the differential pressure across the flow meter affects the

flow.

Explain why the difference between experimental and theoretical values exists.

There is bound to be a discrepancy between the experimental and the theoretical values based on a

number of factors. First, there are error encountered during the reading of values and a few errors are

observed owing to incorrect transcription and evaluation. Secondly, there are a number of

inconsistencies when transferring pressure. The Bernoulli effect discusses such turbulences. They

affect the Bernoulli’s principle in that the volume flow rate of the flowing fluid is massively affected.

Thirdly, there is another factor known as viscosity, that determines the flow rate of a fluid. Different

fluids have different viscous rates. The viscosity is affected by a number of factors such as

atmospheric pressures, ambient temperature, material composition of the fluid, as well as the

container.

CONCLUSION

In a nutshell, the sonic nozzle can be used to design a lot about the supersonic flow. Some of the

automobiles that use the nozzle are automobiles or aerofoils. To accelerate subsonic flow, the nozzle

flow area must first decrease in the flow direction. The flow area reaches a minimum at the point

where the Mach number is unit. To continue to accelerate the flow to supersonic conditions, the flow

area must increase. The minimum flow area is the throat of the nozzle and the flow area in a subsonic

nozzle decreases in the flow direction.

REFERENCES

Heming, Hu, Cui Lishui, Wang Chi, Meng Tao, and Li Chunhui. "Experimental study on the critical

back-pressure ratio of a sonic nozzle at low Reynold number." Chinese Journal of Scientific

Instrument 33, no. 4 (2012): 737-742.

Wang, C., Ding, H. and Wang, H., 2013. Thermodynamic model and dynamic temperature

compensation in positive-pressure-based sonic nozzle gas flow standard. IEEE Transactions on

Instrumentation and Measurement, 62(5), pp.1154-1165.

Page 8 of 8

flow.

Explain why the difference between experimental and theoretical values exists.

There is bound to be a discrepancy between the experimental and the theoretical values based on a

number of factors. First, there are error encountered during the reading of values and a few errors are

observed owing to incorrect transcription and evaluation. Secondly, there are a number of

inconsistencies when transferring pressure. The Bernoulli effect discusses such turbulences. They

affect the Bernoulli’s principle in that the volume flow rate of the flowing fluid is massively affected.

Thirdly, there is another factor known as viscosity, that determines the flow rate of a fluid. Different

fluids have different viscous rates. The viscosity is affected by a number of factors such as

atmospheric pressures, ambient temperature, material composition of the fluid, as well as the

container.

CONCLUSION

In a nutshell, the sonic nozzle can be used to design a lot about the supersonic flow. Some of the

automobiles that use the nozzle are automobiles or aerofoils. To accelerate subsonic flow, the nozzle

flow area must first decrease in the flow direction. The flow area reaches a minimum at the point

where the Mach number is unit. To continue to accelerate the flow to supersonic conditions, the flow

area must increase. The minimum flow area is the throat of the nozzle and the flow area in a subsonic

nozzle decreases in the flow direction.

REFERENCES

Heming, Hu, Cui Lishui, Wang Chi, Meng Tao, and Li Chunhui. "Experimental study on the critical

back-pressure ratio of a sonic nozzle at low Reynold number." Chinese Journal of Scientific

Instrument 33, no. 4 (2012): 737-742.

Wang, C., Ding, H. and Wang, H., 2013. Thermodynamic model and dynamic temperature

compensation in positive-pressure-based sonic nozzle gas flow standard. IEEE Transactions on

Instrumentation and Measurement, 62(5), pp.1154-1165.

Page 8 of 8

1 out of 11

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.