Stress and Well-Being at Work: A Century of Empirical Trends Reflecting Theoretical and Societal Influences

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|14

|17361

|173

AI Summary

This review examines the history of stress research in the Journal of Applied Psychology (JAP) by tracking word frequencies from 606 abstracts of published articles in the journal. The article defines key terms, examines significant historic events and macro societal trends that frame stress research, identifies important developments in theory related to stress and well-being, and examines articles published in the journal during the past 100 years and consider how these publications relate to events in society and advances in theory.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Stress and Well-Being at Work: A Century of Empirical Trends Reflecting

Theoretical and Societal Influences

Paul D. Bliese

University of South Carolina

Jeffrey R. Edwards

University of North Carolina

Sabine Sonnentag

University of Mannheim

In various forms, research on stress and well-being has been a part of the Journal of Applied Psychology

(JAP) since its inception. In this review, we examine the history of stress research in JAP by tracking

word frequencies from 606 abstracts of published articles in the journal. From these abstracts, we define

3 eras: a 50 year-era from 1917 to 1966, a 30-year era from 1967 to 1996, and a 20-year era from 1997

to the present. Each era is distinct in terms of the number of articles published and the general themes

of the topic areas examined. We show that advances in theory are a major impetus underlying research

topics and the number of publications. Our review also suggests that articles have increasingly tended to

reflect broader events occurring in society such as recessions and workforce changes. We conclude by

offering ideas about the future of stress and well-being research.

Keywords: stress, stressors, strain, health, well-being

Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000109.supp

April 6, 1917: the U.S. enters the Great War—a war that

required another global war before earning the name “World War

I.” Roughly 1 year later, an influenza epidemic kills over 500,000

U.S. citizens. In the following year, the nation’s concerns about

alcohol abuse lead to a 14-year period of prohibition. Twelve years

after 1917, the stock market crash of 1929 triggers the great

depression, and tens of thousands remain unemployed for years.

By most objective standards, the decades following the incep-

tion of the Journal of Applied Psychology (JAP) were a remark-

ably stressful period for workers (and citizens) in the U.S. and

much of the world. With these events as backdrop, one would

expect to find that the topic of stress dominated the early pages of

JAP. Perhaps not surprisingly, the story is more complicated: The

journal does indeed reflect the influence of stressors occurring

within society, but research on stress and well-being in work

contexts was relatively rare for approximately the first 50 years,

though traces of what we now view as stress research can be seen

as early as 1917.

For instance, Fish (1917) discussed the challenges of maintain-

ing a skilled workforce “as the country is drawn into war” (p. 161)

and noted concerns about alcohol consumption by stating that

[i]t goes without saying in these days that no employer wishes to have

any of his men under the influence of liquor . . . because we all realize

now that a man is stupefied to some extent even by what is known as

moderate drinking. (p. 165)

Fish went on to write that the “first essential” for meeting labor

demands is that the “shop shall be comfortable in both a physical

and a mental way” (p. 162). Fish’s interests in stress and well-

being were consistent with the broader “mental hygiene” move-

ment of the time (e.g., Martin, 1917). Martin advocated an expan-

sive agenda, arguing that

[b]y mental hygiene I mean the psychological work to be done in

creating, maintaining, and restoring normal mental activity in a given

individual. There are many reasons why our association should im-

mediately take the lead, set the pace as it were, in this matter of mental

hygiene. (p. 67)

A final example of the traces of what we recognize as stress

research is reflected in Hall’s (1917) description of soldiers’ stress

reactions to the demands of war. Hall wrote

We shall surely have a new and larger psychology of war. The older

literature on it is already more or less obsolete from almost every

point of view, and James’ theory of a moral, and Cannon’s of a

physiological, equivalent of war seem now pallid and academic. (p.

12)

Although there was clearly an early impetus to focus on factors

related to stress and well-being, the research evidence suggests the

This article was published Online First January 26, 2017.

Paul D. Bliese, Department of Management, Darla Moore School of

Business, University of South Carolina; Jeffrey R. Edwards, Kenan-Flagler

Business School, University of North Carolina; Sabine Sonnentag, Depart-

ment of Psychology, University of Mannheim.

We thank Patrick Flynn and Charlotte H. Larson for their help with this

article.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Paul D.

Bliese, Department of Management, Darla Moore School of Business,

University of South Carolina, 1014 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208.

E-mail: paul.bliese@moore.sc.edu

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Journal of Applied Psychology © 2017 American Psychological Association

2017, Vol. 102, No. 3, 389 – 402 0021-9010/17/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000109

389

Theoretical and Societal Influences

Paul D. Bliese

University of South Carolina

Jeffrey R. Edwards

University of North Carolina

Sabine Sonnentag

University of Mannheim

In various forms, research on stress and well-being has been a part of the Journal of Applied Psychology

(JAP) since its inception. In this review, we examine the history of stress research in JAP by tracking

word frequencies from 606 abstracts of published articles in the journal. From these abstracts, we define

3 eras: a 50 year-era from 1917 to 1966, a 30-year era from 1967 to 1996, and a 20-year era from 1997

to the present. Each era is distinct in terms of the number of articles published and the general themes

of the topic areas examined. We show that advances in theory are a major impetus underlying research

topics and the number of publications. Our review also suggests that articles have increasingly tended to

reflect broader events occurring in society such as recessions and workforce changes. We conclude by

offering ideas about the future of stress and well-being research.

Keywords: stress, stressors, strain, health, well-being

Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000109.supp

April 6, 1917: the U.S. enters the Great War—a war that

required another global war before earning the name “World War

I.” Roughly 1 year later, an influenza epidemic kills over 500,000

U.S. citizens. In the following year, the nation’s concerns about

alcohol abuse lead to a 14-year period of prohibition. Twelve years

after 1917, the stock market crash of 1929 triggers the great

depression, and tens of thousands remain unemployed for years.

By most objective standards, the decades following the incep-

tion of the Journal of Applied Psychology (JAP) were a remark-

ably stressful period for workers (and citizens) in the U.S. and

much of the world. With these events as backdrop, one would

expect to find that the topic of stress dominated the early pages of

JAP. Perhaps not surprisingly, the story is more complicated: The

journal does indeed reflect the influence of stressors occurring

within society, but research on stress and well-being in work

contexts was relatively rare for approximately the first 50 years,

though traces of what we now view as stress research can be seen

as early as 1917.

For instance, Fish (1917) discussed the challenges of maintain-

ing a skilled workforce “as the country is drawn into war” (p. 161)

and noted concerns about alcohol consumption by stating that

[i]t goes without saying in these days that no employer wishes to have

any of his men under the influence of liquor . . . because we all realize

now that a man is stupefied to some extent even by what is known as

moderate drinking. (p. 165)

Fish went on to write that the “first essential” for meeting labor

demands is that the “shop shall be comfortable in both a physical

and a mental way” (p. 162). Fish’s interests in stress and well-

being were consistent with the broader “mental hygiene” move-

ment of the time (e.g., Martin, 1917). Martin advocated an expan-

sive agenda, arguing that

[b]y mental hygiene I mean the psychological work to be done in

creating, maintaining, and restoring normal mental activity in a given

individual. There are many reasons why our association should im-

mediately take the lead, set the pace as it were, in this matter of mental

hygiene. (p. 67)

A final example of the traces of what we recognize as stress

research is reflected in Hall’s (1917) description of soldiers’ stress

reactions to the demands of war. Hall wrote

We shall surely have a new and larger psychology of war. The older

literature on it is already more or less obsolete from almost every

point of view, and James’ theory of a moral, and Cannon’s of a

physiological, equivalent of war seem now pallid and academic. (p.

12)

Although there was clearly an early impetus to focus on factors

related to stress and well-being, the research evidence suggests the

This article was published Online First January 26, 2017.

Paul D. Bliese, Department of Management, Darla Moore School of

Business, University of South Carolina; Jeffrey R. Edwards, Kenan-Flagler

Business School, University of North Carolina; Sabine Sonnentag, Depart-

ment of Psychology, University of Mannheim.

We thank Patrick Flynn and Charlotte H. Larson for their help with this

article.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Paul D.

Bliese, Department of Management, Darla Moore School of Business,

University of South Carolina, 1014 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208.

E-mail: paul.bliese@moore.sc.edu

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Journal of Applied Psychology © 2017 American Psychological Association

2017, Vol. 102, No. 3, 389 – 402 0021-9010/17/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000109

389

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

agenda was not widely adopted in the early years of JAP. Further-

more, published articles during the early decades failed to reflect

the broad visions proposed by individuals such as Hall, Martin,

and Fish. Instead, articles we recognize as stress research tended to

examine demographic variables such as age, race, profession, and

physical activity as predictors of outcomes such as mental fatigue

and psychoneurotic symptoms (e.g., Garth, 1920; Elwood, 1927).

While these types of articles laid the foundations for future work,

they did not really capture the calls to “immediately take the lead”

with respect to “maintaining and restoring” mental hygiene by

Martin, meeting the “first essential” for “comfortable” shops ad-

vocated by Fish, or advancing a “new and larger psychology of

war” anticipated by Hall.

Based on our review, it took 16 years for the journal to publish

a study that can be clearly identified as having both a work-

relevant stressor and strain. Laird (1933) experimentally examined

the effects of loud noise (an organizational stressor) and noted that

loud noise appeared to cause somatic complaints (a strain). Laird

wrote that “[w]ith the more intense noises muscular stiffness was

noted, especially in the neck and legs” (p. 328) and speculated that

the stiffness was due to an accumulation of lactates, given that

“[n]either of these groups of muscles was used during the work

period . . .” (p. 328). Laird’s examination of work stressors and

strains associated with the industrial age was followed by others,

but the number of publications was relatively small for another 30

or so years at which point (the mid to late 1960s) the rate of

publications increased substantially. 1

In this review, we follow the development of stress and well-

being research published in JAP over the past 100 years. We

examine how publication trends were influenced by larger societal

events and developments in stress theory. The foundation of our

review is based upon 606 stress-related articles published in JAP

from 1917 to present.

The structure is as follows: First, we define key terms that fall

within the domain of our review. Second, we examine significant

historic events and macro societal trends that frame stress research.

Third, we identify important developments in theory related to

stress and well-being. Fourth, we examine articles published in the

journal during the past 100 years and consider how these publica-

tions relate to events in society and advances in theory. As part of

our review, we identify articles that we consider exemplary and

influential. Finally, we summarize the first century, take stock of

theoretical and empirical research, and discuss future directions.

Defining Key Terms

When summarizing theory and empirical research on stress

and well-being, one of the key challenges involves the varied

interpretations of key terms. The term “stress,” in particular,

has multiple meanings, referring to a condition or event in the

situation, the person’s reaction to the situation, or the relation-

ship between the person and situation (Hobfoll, 1989; Jex,

Beehr, & Roberts, 1992; McGrath, 1970). For this reason, stress

research often differentiates stressors (conditions and events

causing subsequent reactions), perceived stress (perception and

appraisal of the stressors), and strains (psychological, physio-

logical, and behavioral outcomes). Research in the domain of

stress and well-being has also focused extensively on modera-

tors—attributes of the individual or work environment that alter

the strength of links between stressors, perceived stress, and

strains. Therefore, in this review, we differentiate among stres-

sors, perceived stress, strain, and moderators and reserve the

term “stress” to designate the domain of stress research (cf.

Beehr & Newman, 1978; Kahn & Byosiere, 1992).

Historic Events and Macro Societal Trends

Scientific journals vary in the degree to which published articles

are expected to mirror broad societal events. However, it is rea-

sonable to assume that, as an applied journal, JAP would publish

articles that reflect societal events. Based on this assumption, we

assembled a chronology of major events that would ostensibly

have signified stressors and engendered strain in the working

population. Online Appendix A lists these events, and we supple-

ment these events by identifying systemic changes in society that

span the time frame of our review.

Macro Societal Trends

As a whole, the century between 1917 and 2017 represented a

period of major political, economic, technological, and societal

change. Major historic events include two world wars and other

significant conflicts (e.g., Korean War, Vietnam War). The century

also witnessed the emergence of new nations, mainly in Africa and

Asia, along with the rise and fall of the Soviet Union. Concurrent

with these events, people faced economic turbulence. The Great

Depression (1929 –1939) had major impacts on many countries,

and in the U.S., the gross national product dropped substantially

while the unemployment rate exceeded 20%.

Technology transformed how people lived and worked. In the

early 20th century, industrial work was dominated by mass pro-

duction, enabled by the assembly line popularized by the Ford

Motor Company in 1913. During the subsequent decades, ratio-

nalization of tasks and jobs continued (Davis & Taylor, 1972).

These developments triggered employee reactions such as alien-

ation invoking feelings of powerlessness, meaninglessness, social

isolation, and self-estrangement (Shepard, 1977). Signs of these

effects include large-scale strikes in 1946 and the seizure of U.S.

steel mills to avoid strikes in 1952 (online Appendix A).

Throughout the century, information and communication tech-

nology influenced all areas of the economy. The introduction of

mainframe computers in the 1960s had relatively limited effects,

but the subsequent development of microprocessors led to perva-

sive changes. For instance, the manufacturing industry witnessed

the introduction of computer-aided design, computerized numeri-

cally controlled machine tools, and industrial robots. Administra-

tive jobs substantially changed with the advent of personal com-

puters following the release of the IBM PC in 1981. The use of

computerized communication technologies accelerated after com-

mercial Internet providers increasingly entered the market in the

late 1980s documented by the increase in Internet users worldwide

from 394 million in 2000 to 2.94 billion in 2014 (Statista, 2015).

With these technological changes, many jobs were no longer

restricted to one location (e.g., onsite offices) and could instead be

1 As a point of interest, we note that Laird is one of the top 25

stress-related articles for citation rates in the first 50 years of the journal

(see online Appendix B).

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

390 BLIESE, EDWARDS, AND SONNENTAG

more, published articles during the early decades failed to reflect

the broad visions proposed by individuals such as Hall, Martin,

and Fish. Instead, articles we recognize as stress research tended to

examine demographic variables such as age, race, profession, and

physical activity as predictors of outcomes such as mental fatigue

and psychoneurotic symptoms (e.g., Garth, 1920; Elwood, 1927).

While these types of articles laid the foundations for future work,

they did not really capture the calls to “immediately take the lead”

with respect to “maintaining and restoring” mental hygiene by

Martin, meeting the “first essential” for “comfortable” shops ad-

vocated by Fish, or advancing a “new and larger psychology of

war” anticipated by Hall.

Based on our review, it took 16 years for the journal to publish

a study that can be clearly identified as having both a work-

relevant stressor and strain. Laird (1933) experimentally examined

the effects of loud noise (an organizational stressor) and noted that

loud noise appeared to cause somatic complaints (a strain). Laird

wrote that “[w]ith the more intense noises muscular stiffness was

noted, especially in the neck and legs” (p. 328) and speculated that

the stiffness was due to an accumulation of lactates, given that

“[n]either of these groups of muscles was used during the work

period . . .” (p. 328). Laird’s examination of work stressors and

strains associated with the industrial age was followed by others,

but the number of publications was relatively small for another 30

or so years at which point (the mid to late 1960s) the rate of

publications increased substantially. 1

In this review, we follow the development of stress and well-

being research published in JAP over the past 100 years. We

examine how publication trends were influenced by larger societal

events and developments in stress theory. The foundation of our

review is based upon 606 stress-related articles published in JAP

from 1917 to present.

The structure is as follows: First, we define key terms that fall

within the domain of our review. Second, we examine significant

historic events and macro societal trends that frame stress research.

Third, we identify important developments in theory related to

stress and well-being. Fourth, we examine articles published in the

journal during the past 100 years and consider how these publica-

tions relate to events in society and advances in theory. As part of

our review, we identify articles that we consider exemplary and

influential. Finally, we summarize the first century, take stock of

theoretical and empirical research, and discuss future directions.

Defining Key Terms

When summarizing theory and empirical research on stress

and well-being, one of the key challenges involves the varied

interpretations of key terms. The term “stress,” in particular,

has multiple meanings, referring to a condition or event in the

situation, the person’s reaction to the situation, or the relation-

ship between the person and situation (Hobfoll, 1989; Jex,

Beehr, & Roberts, 1992; McGrath, 1970). For this reason, stress

research often differentiates stressors (conditions and events

causing subsequent reactions), perceived stress (perception and

appraisal of the stressors), and strains (psychological, physio-

logical, and behavioral outcomes). Research in the domain of

stress and well-being has also focused extensively on modera-

tors—attributes of the individual or work environment that alter

the strength of links between stressors, perceived stress, and

strains. Therefore, in this review, we differentiate among stres-

sors, perceived stress, strain, and moderators and reserve the

term “stress” to designate the domain of stress research (cf.

Beehr & Newman, 1978; Kahn & Byosiere, 1992).

Historic Events and Macro Societal Trends

Scientific journals vary in the degree to which published articles

are expected to mirror broad societal events. However, it is rea-

sonable to assume that, as an applied journal, JAP would publish

articles that reflect societal events. Based on this assumption, we

assembled a chronology of major events that would ostensibly

have signified stressors and engendered strain in the working

population. Online Appendix A lists these events, and we supple-

ment these events by identifying systemic changes in society that

span the time frame of our review.

Macro Societal Trends

As a whole, the century between 1917 and 2017 represented a

period of major political, economic, technological, and societal

change. Major historic events include two world wars and other

significant conflicts (e.g., Korean War, Vietnam War). The century

also witnessed the emergence of new nations, mainly in Africa and

Asia, along with the rise and fall of the Soviet Union. Concurrent

with these events, people faced economic turbulence. The Great

Depression (1929 –1939) had major impacts on many countries,

and in the U.S., the gross national product dropped substantially

while the unemployment rate exceeded 20%.

Technology transformed how people lived and worked. In the

early 20th century, industrial work was dominated by mass pro-

duction, enabled by the assembly line popularized by the Ford

Motor Company in 1913. During the subsequent decades, ratio-

nalization of tasks and jobs continued (Davis & Taylor, 1972).

These developments triggered employee reactions such as alien-

ation invoking feelings of powerlessness, meaninglessness, social

isolation, and self-estrangement (Shepard, 1977). Signs of these

effects include large-scale strikes in 1946 and the seizure of U.S.

steel mills to avoid strikes in 1952 (online Appendix A).

Throughout the century, information and communication tech-

nology influenced all areas of the economy. The introduction of

mainframe computers in the 1960s had relatively limited effects,

but the subsequent development of microprocessors led to perva-

sive changes. For instance, the manufacturing industry witnessed

the introduction of computer-aided design, computerized numeri-

cally controlled machine tools, and industrial robots. Administra-

tive jobs substantially changed with the advent of personal com-

puters following the release of the IBM PC in 1981. The use of

computerized communication technologies accelerated after com-

mercial Internet providers increasingly entered the market in the

late 1980s documented by the increase in Internet users worldwide

from 394 million in 2000 to 2.94 billion in 2014 (Statista, 2015).

With these technological changes, many jobs were no longer

restricted to one location (e.g., onsite offices) and could instead be

1 As a point of interest, we note that Laird is one of the top 25

stress-related articles for citation rates in the first 50 years of the journal

(see online Appendix B).

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

390 BLIESE, EDWARDS, AND SONNENTAG

conducted in other places, such as the home. On the one hand, this

trend contributed to telecommuting arrangements that had the

potential to increase individual autonomy and reduce work–family

conflict and role stress (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007). On the other

hand, mobile devices enabled employees in many jobs to work

“anywhere, anytime” and stay electronically tethered to work

outside formal working hours. These changes in work patterns

created situations in which the boundaries between work and life

became permeable, a development with both positive and negative

implications for stress experiences.

Several other major changes occurred during the 20th century.

First, jobs in the primary and secondary economic sectors (extract-

ing raw materials and producing goods) steadily declined, while

jobs in the tertiary (or service sector) increased, particularly in the

Western world. Notably, in the U.S. the percentage of employees

working in the service sector increased from around 65% in 1961

to over 85% in 2010. This shift accompanied changes in job

requirements and job stressors, such as reduced physical and

environmental stressors (e.g., Laird, 1933) and increased stressors

related to emotional labor (Pugliesi, 1999).

Second, the participation of women in the labor market grew

dramatically. In 1920, about 20% of the female U.S. population

was employed. This figure rose to 60% in 2000, with the largest

increase occurring between 1960 and 1980. As a result, men and

women living in dual-earner families had to deal with changes in

work and nonwork roles and responsibilities, leading to increases

in conflict between work and family (e.g., Higgins, Duxbury, &

Irving, 1992).

Third, during the second half of the 20th century, the economy

became increasingly global. This development was accompanied

by global competition that arguably contributed to an increase in

stressors such as workload, job insecurity, and downsizing. Glo-

balization was also associated with increased international mobil-

ity of individuals, often leading to stressful experiences for those

adjusting to new cultures and work environments (Silbiger &

Pines, 2014).

Taken together, these political, economic, technological, and

societal developments had broad and significant effects on peo-

ple’s lives in and outside of work. These events provide a backdrop

against which theoretical and empirical research on work-related

stress grew and developed over the century.

Key Theoretical Models

General Theories of Psychological Stress

The founding of JAP in 1917 roughly coincided with the be-

ginnings of theory development in contemporary stress research.

Most of these early developments originated outside of the orga-

nizational literature but were eventually integrated into research on

stress in work settings. We first summarize key theoretical models

in the literature on psychological stress in general and then turn to

models devoted to stress in work settings.

Historical accounts of the stress field (e.g., Cooper & Dewe,

2004; Lazarus, 1993; Mason, 1975a, 1975b) often trace the origins

of stress research to Cannon (1915), who coined the phrase “fight

or flight” to describe an organism’s response to an external threat.

Cannon (1932) later indicated that the response to threat represents

deviation from homeostasis, which he viewed as the self-regulation of

physiological processes. A subsequent landmark is the work of

Selye (1936), who described reactions to stress in terms of the

general adaptation syndrome (GAS), which referred to the non-

specific response of the body to any demand. According to Selye,

the GAS comprised three stages that included alarm, resistance,

and exhaustion—the first two of which involved attempts to adapt

to the demand, and the third indicating depletion of adaptive

energy. Like Cannon, Selye focused on physiological responses to

stress, such as changes in adrenaline, cortisol, and other hormones.

In the 1960s, the field of stress research experienced a notice-

able shift as it began to focus on major life events that required

adjustment and led to psychological and physical illness (Dohren-

wend & Dohrenwend, 1981; Thoits, 1983). This research was

stimulated by the development of the Social Readjustment Rating

Scale (SRRS; Holmes & Rahe, 1967), a checklist that comprised

43 stressful life events. Scores on the SRRS were weighted by the

amount of readjustment each event was deemed to require and

summed to derive an overall measure of life stress. The SRRS has

been used in numerous studies (Dohrenwend, 2006), although its

relationships with mental and physical symptoms were generally

modest, with correlations rarely exceeding .30.

The modest relationships between life events and illness prompted

investigations into factors that might moderate these relationships,

such as personality, self-esteem, social support, Type-A behavior, and

the meaning of the event to the individual (Cohen & Edwards,

1989; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Kessler, Price, & Wortman, 1985).

Research showed that the relationship between life events and

outcomes depended on event timing and magnitude as well as the

undesirability and perceived control over the events (Mullen &

Suls, 1982; Thoits, 1983; Vinokur & Selzer, 1975). As such, this

research began to underscore the essential role of individual dif-

ferences in the stress process, a theme that permeated subsequent

theoretical work.

Arguably, one of the most influential theoretical models of

psychological stress was the transactional theory presented by

Lazarus in 1966 and later expanded by Lazarus and Folkman in

1984 (Lazarus, 1966; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Lazarus’ theory

reinforced the importance of subjective factors in the stress process

and asserted that the effects of potential stressors on well-being

were largely determined by how they were cognitively appraised

by the individual. Lazarus distinguished two forms of cognitive

appraisal: (a) primary appraisal, which determined whether a po-

tential stressor was viewed as harmful, threatening, or challenging;

and (b) secondary appraisal, which considered what individuals

might do to manage the stressful transaction. Lazarus’ work also

placed particular emphasis on the ways in which individuals cope

with stress (e.g., Lazarus, 1993; Lazarus, Averill, & Opton, 1974).

Lazarus contrasted coping styles, which are individual differences

that characterize how people cope, with coping processes, which

focus on the particular approaches people use to manage stressful

transactions between the person and situation. This work stimu-

lated the development of measures designed to assess the variety

of processes by which people cope with stress, of which the Ways

of Coping Questionnaire (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988) became the

most widely used.

The central importance of cognitive appraisal underscored by

Lazarus was maintained in subsequent theoretical work. A prime

example is the conservation of resources (COR) theory proposed

by Hobfoll (1989). This theory posits that stress occurs when

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

391STRESS AND WELL-BEING

trend contributed to telecommuting arrangements that had the

potential to increase individual autonomy and reduce work–family

conflict and role stress (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007). On the other

hand, mobile devices enabled employees in many jobs to work

“anywhere, anytime” and stay electronically tethered to work

outside formal working hours. These changes in work patterns

created situations in which the boundaries between work and life

became permeable, a development with both positive and negative

implications for stress experiences.

Several other major changes occurred during the 20th century.

First, jobs in the primary and secondary economic sectors (extract-

ing raw materials and producing goods) steadily declined, while

jobs in the tertiary (or service sector) increased, particularly in the

Western world. Notably, in the U.S. the percentage of employees

working in the service sector increased from around 65% in 1961

to over 85% in 2010. This shift accompanied changes in job

requirements and job stressors, such as reduced physical and

environmental stressors (e.g., Laird, 1933) and increased stressors

related to emotional labor (Pugliesi, 1999).

Second, the participation of women in the labor market grew

dramatically. In 1920, about 20% of the female U.S. population

was employed. This figure rose to 60% in 2000, with the largest

increase occurring between 1960 and 1980. As a result, men and

women living in dual-earner families had to deal with changes in

work and nonwork roles and responsibilities, leading to increases

in conflict between work and family (e.g., Higgins, Duxbury, &

Irving, 1992).

Third, during the second half of the 20th century, the economy

became increasingly global. This development was accompanied

by global competition that arguably contributed to an increase in

stressors such as workload, job insecurity, and downsizing. Glo-

balization was also associated with increased international mobil-

ity of individuals, often leading to stressful experiences for those

adjusting to new cultures and work environments (Silbiger &

Pines, 2014).

Taken together, these political, economic, technological, and

societal developments had broad and significant effects on peo-

ple’s lives in and outside of work. These events provide a backdrop

against which theoretical and empirical research on work-related

stress grew and developed over the century.

Key Theoretical Models

General Theories of Psychological Stress

The founding of JAP in 1917 roughly coincided with the be-

ginnings of theory development in contemporary stress research.

Most of these early developments originated outside of the orga-

nizational literature but were eventually integrated into research on

stress in work settings. We first summarize key theoretical models

in the literature on psychological stress in general and then turn to

models devoted to stress in work settings.

Historical accounts of the stress field (e.g., Cooper & Dewe,

2004; Lazarus, 1993; Mason, 1975a, 1975b) often trace the origins

of stress research to Cannon (1915), who coined the phrase “fight

or flight” to describe an organism’s response to an external threat.

Cannon (1932) later indicated that the response to threat represents

deviation from homeostasis, which he viewed as the self-regulation of

physiological processes. A subsequent landmark is the work of

Selye (1936), who described reactions to stress in terms of the

general adaptation syndrome (GAS), which referred to the non-

specific response of the body to any demand. According to Selye,

the GAS comprised three stages that included alarm, resistance,

and exhaustion—the first two of which involved attempts to adapt

to the demand, and the third indicating depletion of adaptive

energy. Like Cannon, Selye focused on physiological responses to

stress, such as changes in adrenaline, cortisol, and other hormones.

In the 1960s, the field of stress research experienced a notice-

able shift as it began to focus on major life events that required

adjustment and led to psychological and physical illness (Dohren-

wend & Dohrenwend, 1981; Thoits, 1983). This research was

stimulated by the development of the Social Readjustment Rating

Scale (SRRS; Holmes & Rahe, 1967), a checklist that comprised

43 stressful life events. Scores on the SRRS were weighted by the

amount of readjustment each event was deemed to require and

summed to derive an overall measure of life stress. The SRRS has

been used in numerous studies (Dohrenwend, 2006), although its

relationships with mental and physical symptoms were generally

modest, with correlations rarely exceeding .30.

The modest relationships between life events and illness prompted

investigations into factors that might moderate these relationships,

such as personality, self-esteem, social support, Type-A behavior, and

the meaning of the event to the individual (Cohen & Edwards,

1989; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Kessler, Price, & Wortman, 1985).

Research showed that the relationship between life events and

outcomes depended on event timing and magnitude as well as the

undesirability and perceived control over the events (Mullen &

Suls, 1982; Thoits, 1983; Vinokur & Selzer, 1975). As such, this

research began to underscore the essential role of individual dif-

ferences in the stress process, a theme that permeated subsequent

theoretical work.

Arguably, one of the most influential theoretical models of

psychological stress was the transactional theory presented by

Lazarus in 1966 and later expanded by Lazarus and Folkman in

1984 (Lazarus, 1966; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Lazarus’ theory

reinforced the importance of subjective factors in the stress process

and asserted that the effects of potential stressors on well-being

were largely determined by how they were cognitively appraised

by the individual. Lazarus distinguished two forms of cognitive

appraisal: (a) primary appraisal, which determined whether a po-

tential stressor was viewed as harmful, threatening, or challenging;

and (b) secondary appraisal, which considered what individuals

might do to manage the stressful transaction. Lazarus’ work also

placed particular emphasis on the ways in which individuals cope

with stress (e.g., Lazarus, 1993; Lazarus, Averill, & Opton, 1974).

Lazarus contrasted coping styles, which are individual differences

that characterize how people cope, with coping processes, which

focus on the particular approaches people use to manage stressful

transactions between the person and situation. This work stimu-

lated the development of measures designed to assess the variety

of processes by which people cope with stress, of which the Ways

of Coping Questionnaire (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988) became the

most widely used.

The central importance of cognitive appraisal underscored by

Lazarus was maintained in subsequent theoretical work. A prime

example is the conservation of resources (COR) theory proposed

by Hobfoll (1989). This theory posits that stress occurs when

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

391STRESS AND WELL-BEING

resources the individual considers valuable are threatened, lost, or

foregone. Resources in COR theory refer to objects, conditions,

and personal characteristics that are valued in their own right or

because they can help the individual achieve or protect other

valued resources. COR theory was initially framed as an alterna-

tive to appraisal-based theories, such as Lazarus’ transactional

theory, by placing greater emphasis on the objective environment

as a determinant of stress. Nonetheless, cognitive appraisal plays a

key role in the evaluation of resources, the perception that re-

sources are at risk, and other basic processes involved in COR

theory. Although some researchers have argued that certain symp-

toms of strain, such as affective arousal, might not require cogni-

tive appraisal as a precursor (Zajonc, 1984), most contemporary

theories of stress indicate that appraisal plays a key role in trans-

lating experienced stressors into strains and coping processes

(Lazarus, 1984).

Theories of Stress in Work Contexts

Many of the theoretical developments in research on psycho-

logical stress have parallels in theories that focus on stress in the

workplace. For example, Bhagat (1983) proposed a model of the

effects of stressful life events on individual performance, satisfac-

tion, and adjustment in organizational settings and developed a

checklist that distinguished potentially stressful events associated

with job and personal domains (Bhagat, McQuaid, Lindholm, &

Segovis, 1985). Other frameworks have focused on work stressors

that represent ongoing conditions rather than acute life events. For

instance, the reviews of job stress research by Cooper and Marshall

(1976) and Beehr and Newman (1978) were seminal publications

presenting frameworks that identified various job characteristics

considered sources of stress. These frameworks also include indi-

vidual differences that can modify the effects of job stressors,

many of which overlap with those examined in psychological

stress research. In a similar vein, Karasek (1979; Karasek &

Theorell, 1990) developed a model that focused on two key job

characteristics, job demands and job decision latitude, predicting

that mental strain is the product of high demands coupled with low

decision latitude. Along similar lines, Frankenhaeuser and col-

leagues (Frankenhaeuser & Gardell, 1976; Frankenhaeuser & Jo-

hansson, 1986) established a program of research that examined

stress in terms of job demands relative to worker control in

industrial settings, with particular emphasis on psychobiological

outcomes. Analogously, the challenge-hindrance approach to job

stress (Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, & Boudreau, 2000; LePine,

LePine, & Jackson, 2004) classifies work-related demands and

circumstances as challenges or hindrances based on whether they

bring about gains or losses for the employee.

Other theories of stress at work emphasize the role of cognitive

appraisal, echoing the theories of psychological stress set forth by

Lazarus, Hobfoll, and others. A notable example is the theory of

role stress by Kahn and colleagues (Kahn & Quinn, 1970; Kahn,

Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964), which examines how

characteristics of organizational roles (e.g., conflict, ambiguity,

overload) are perceived and experienced as stressors by role in-

cumbents, leading to affective and physiological symptoms as well

as coping responses. Likewise, the person– environment (P–E) fit

theory of job stress (French, Caplan, & Van Harrison, 1982)

distinguishes objective person and environment factors from their

subjective counterparts and emphasizes the fit between the sub-

jective person and environment as the key determinant of psycho-

logical, physiological, and behavioral strains along with coping

and defense mechanisms. Similarly, the cybernetic theories of

work-related stress proposed by Cummings and Cooper (1979) and

Edwards (1992) frame stress as a discrepancy between perceptions

and important desires which lead to psychological and physical

symptoms and efforts to resolve perceived discrepancies. Along

similar lines, the conceptualization of stress in organizations pre-

sented by Schuler (1980) posits that stress exists when a person is

confronted with demand, constraint, or opportunity for being,

having, or doing what he or she desires, which leads to psycho-

logical, physical, and behavioral symptoms as well as efforts to

reduce stress and its deleterious effects.

As noted above, theories of work stress that emphasize cognitive

appraisal often posit that stress not only influences strains and

illness but also triggers coping efforts directed at the sources of

stress. Strategies for coping with work-related stress have been

discussed (e.g., Dewe, O’Driscoll, & Cooper, 2010; Latack &

Havlovic, 1992), and various frameworks have been presented that

distinguish basic forms of coping, such as control, escape, and

symptom management (Latack, 1986) and rational task-oriented

behavior, emotional release, distraction, passive rationalization,

social support (Dewe & Guest, 1990). Some discussions take a

more focused approach by addressing how people cope with

specific sources of work-related stress, such as job loss (Latack,

Kinicki, & Prussia, 1995) and work–family conflict (Wiersma,

1994). Although coping with work stress has been addressed from

a theoretical standpoint, relatively few studies of work stress have

provided a detailed analysis of how people cope with stress.

As with research on stressful life events, many studies of job

stress have examined moderator variables that can influence rela-

tionships between stressors, perceived stress, and outcomes. These

variables include individual differences such as personality (Parkes,

1994), locus of control (Marino & White, 1985), self-esteem (Ganster

& Schaubroeck, 1991), and Type A behavior pattern (e.g., Edwards,

Baglioni, & Cooper, 1990, and the JAP monograph Ganster, Schau-

broeck, Sime, & Mayes, 1991) as well as contextual variables, par-

ticularly social support (House, 1981; Viswesvaran, Sanchez, &

Fisher, 1999).

In summary, the development of stress theories, both in general

and within the domain of work, has followed a progression that can

be traced using the broad classes of variables we used to define the

stress process. This progression begins with identifying stressors

and associated strains, delves into the cognitive appraisal processes

by which stress is perceived, and introduces variables that mod-

erate the linkages between stressors, perceived stress, and strains.

We use this summary of theories as a backdrop against which to

review stress research that has appeared in JAP. Our review also

takes into account the chronology of historical events that have

implications for work stress, as presented in the preceding section.

Empirical Word Counts

We examined macro trends over time using 606 JAP articles

identified using an “OR” operator on the search terms “stressor,”

“stress,” “strain,” “well-being,” “mental health,” “physical health,”

“illness,” “fatigue,” “mental hygiene,” “anxiety,” and “depres-

sion.” The abstracts from the 606 articles were subjected to word

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

392 BLIESE, EDWARDS, AND SONNENTAG

foregone. Resources in COR theory refer to objects, conditions,

and personal characteristics that are valued in their own right or

because they can help the individual achieve or protect other

valued resources. COR theory was initially framed as an alterna-

tive to appraisal-based theories, such as Lazarus’ transactional

theory, by placing greater emphasis on the objective environment

as a determinant of stress. Nonetheless, cognitive appraisal plays a

key role in the evaluation of resources, the perception that re-

sources are at risk, and other basic processes involved in COR

theory. Although some researchers have argued that certain symp-

toms of strain, such as affective arousal, might not require cogni-

tive appraisal as a precursor (Zajonc, 1984), most contemporary

theories of stress indicate that appraisal plays a key role in trans-

lating experienced stressors into strains and coping processes

(Lazarus, 1984).

Theories of Stress in Work Contexts

Many of the theoretical developments in research on psycho-

logical stress have parallels in theories that focus on stress in the

workplace. For example, Bhagat (1983) proposed a model of the

effects of stressful life events on individual performance, satisfac-

tion, and adjustment in organizational settings and developed a

checklist that distinguished potentially stressful events associated

with job and personal domains (Bhagat, McQuaid, Lindholm, &

Segovis, 1985). Other frameworks have focused on work stressors

that represent ongoing conditions rather than acute life events. For

instance, the reviews of job stress research by Cooper and Marshall

(1976) and Beehr and Newman (1978) were seminal publications

presenting frameworks that identified various job characteristics

considered sources of stress. These frameworks also include indi-

vidual differences that can modify the effects of job stressors,

many of which overlap with those examined in psychological

stress research. In a similar vein, Karasek (1979; Karasek &

Theorell, 1990) developed a model that focused on two key job

characteristics, job demands and job decision latitude, predicting

that mental strain is the product of high demands coupled with low

decision latitude. Along similar lines, Frankenhaeuser and col-

leagues (Frankenhaeuser & Gardell, 1976; Frankenhaeuser & Jo-

hansson, 1986) established a program of research that examined

stress in terms of job demands relative to worker control in

industrial settings, with particular emphasis on psychobiological

outcomes. Analogously, the challenge-hindrance approach to job

stress (Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, & Boudreau, 2000; LePine,

LePine, & Jackson, 2004) classifies work-related demands and

circumstances as challenges or hindrances based on whether they

bring about gains or losses for the employee.

Other theories of stress at work emphasize the role of cognitive

appraisal, echoing the theories of psychological stress set forth by

Lazarus, Hobfoll, and others. A notable example is the theory of

role stress by Kahn and colleagues (Kahn & Quinn, 1970; Kahn,

Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964), which examines how

characteristics of organizational roles (e.g., conflict, ambiguity,

overload) are perceived and experienced as stressors by role in-

cumbents, leading to affective and physiological symptoms as well

as coping responses. Likewise, the person– environment (P–E) fit

theory of job stress (French, Caplan, & Van Harrison, 1982)

distinguishes objective person and environment factors from their

subjective counterparts and emphasizes the fit between the sub-

jective person and environment as the key determinant of psycho-

logical, physiological, and behavioral strains along with coping

and defense mechanisms. Similarly, the cybernetic theories of

work-related stress proposed by Cummings and Cooper (1979) and

Edwards (1992) frame stress as a discrepancy between perceptions

and important desires which lead to psychological and physical

symptoms and efforts to resolve perceived discrepancies. Along

similar lines, the conceptualization of stress in organizations pre-

sented by Schuler (1980) posits that stress exists when a person is

confronted with demand, constraint, or opportunity for being,

having, or doing what he or she desires, which leads to psycho-

logical, physical, and behavioral symptoms as well as efforts to

reduce stress and its deleterious effects.

As noted above, theories of work stress that emphasize cognitive

appraisal often posit that stress not only influences strains and

illness but also triggers coping efforts directed at the sources of

stress. Strategies for coping with work-related stress have been

discussed (e.g., Dewe, O’Driscoll, & Cooper, 2010; Latack &

Havlovic, 1992), and various frameworks have been presented that

distinguish basic forms of coping, such as control, escape, and

symptom management (Latack, 1986) and rational task-oriented

behavior, emotional release, distraction, passive rationalization,

social support (Dewe & Guest, 1990). Some discussions take a

more focused approach by addressing how people cope with

specific sources of work-related stress, such as job loss (Latack,

Kinicki, & Prussia, 1995) and work–family conflict (Wiersma,

1994). Although coping with work stress has been addressed from

a theoretical standpoint, relatively few studies of work stress have

provided a detailed analysis of how people cope with stress.

As with research on stressful life events, many studies of job

stress have examined moderator variables that can influence rela-

tionships between stressors, perceived stress, and outcomes. These

variables include individual differences such as personality (Parkes,

1994), locus of control (Marino & White, 1985), self-esteem (Ganster

& Schaubroeck, 1991), and Type A behavior pattern (e.g., Edwards,

Baglioni, & Cooper, 1990, and the JAP monograph Ganster, Schau-

broeck, Sime, & Mayes, 1991) as well as contextual variables, par-

ticularly social support (House, 1981; Viswesvaran, Sanchez, &

Fisher, 1999).

In summary, the development of stress theories, both in general

and within the domain of work, has followed a progression that can

be traced using the broad classes of variables we used to define the

stress process. This progression begins with identifying stressors

and associated strains, delves into the cognitive appraisal processes

by which stress is perceived, and introduces variables that mod-

erate the linkages between stressors, perceived stress, and strains.

We use this summary of theories as a backdrop against which to

review stress research that has appeared in JAP. Our review also

takes into account the chronology of historical events that have

implications for work stress, as presented in the preceding section.

Empirical Word Counts

We examined macro trends over time using 606 JAP articles

identified using an “OR” operator on the search terms “stressor,”

“stress,” “strain,” “well-being,” “mental health,” “physical health,”

“illness,” “fatigue,” “mental hygiene,” “anxiety,” and “depres-

sion.” The abstracts from the 606 articles were subjected to word

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

392 BLIESE, EDWARDS, AND SONNENTAG

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

frequency counts using the tm package for R (Feinerer, Hornik, &

Meyer, 2008, R Core Team, 2014). While the search terms identify

the broader class of relevant literature, the word count frequencies

from abstracts provide insight into specific research topics and

contexts. That is, the key words in the search terms identified the

relevant sample of published research, and the word count fre-

quency gives specific insights into how researchers applied the

concepts. In this way, the work– count frequencies help capture

societal, theoretical, and empirical trends in stress research across

the 100 years of our review.

Our goal was to cast a broad net capturing commentaries, book

reviews, and empirical studies related to stress and well-being. The

specific search terms were selected based on: (a) an article-by-

article examination of the first 10 years of published articles; (b) an

examination of articles every fifth year through the 1960s; and (c)

our knowledge of terms used in influential books and articles. It

was important to directly examine early articles because some

relevant studies used terms such as “mental hygiene” and “mental

fatigue” that would not be identified using terms from the con-

temporary stress literature.

The original query returned 642 matches. We eliminated 36

articles that triggered false positives, as when the word “stress”

was used as a synonym for “emphasize” as in “the authors stress.”

In the early decades, we also excluded several articles that met our

search terms in ways we did not intend (e.g., “eyestrain,” “judg-

mental fatigue”). The remaining 606 articles provide a rich source

for textual analyses that we found to be consistent with other

sources of information, such as citation rates, historic reviews, and

our knowledge of the field.

Number of Publications by Year

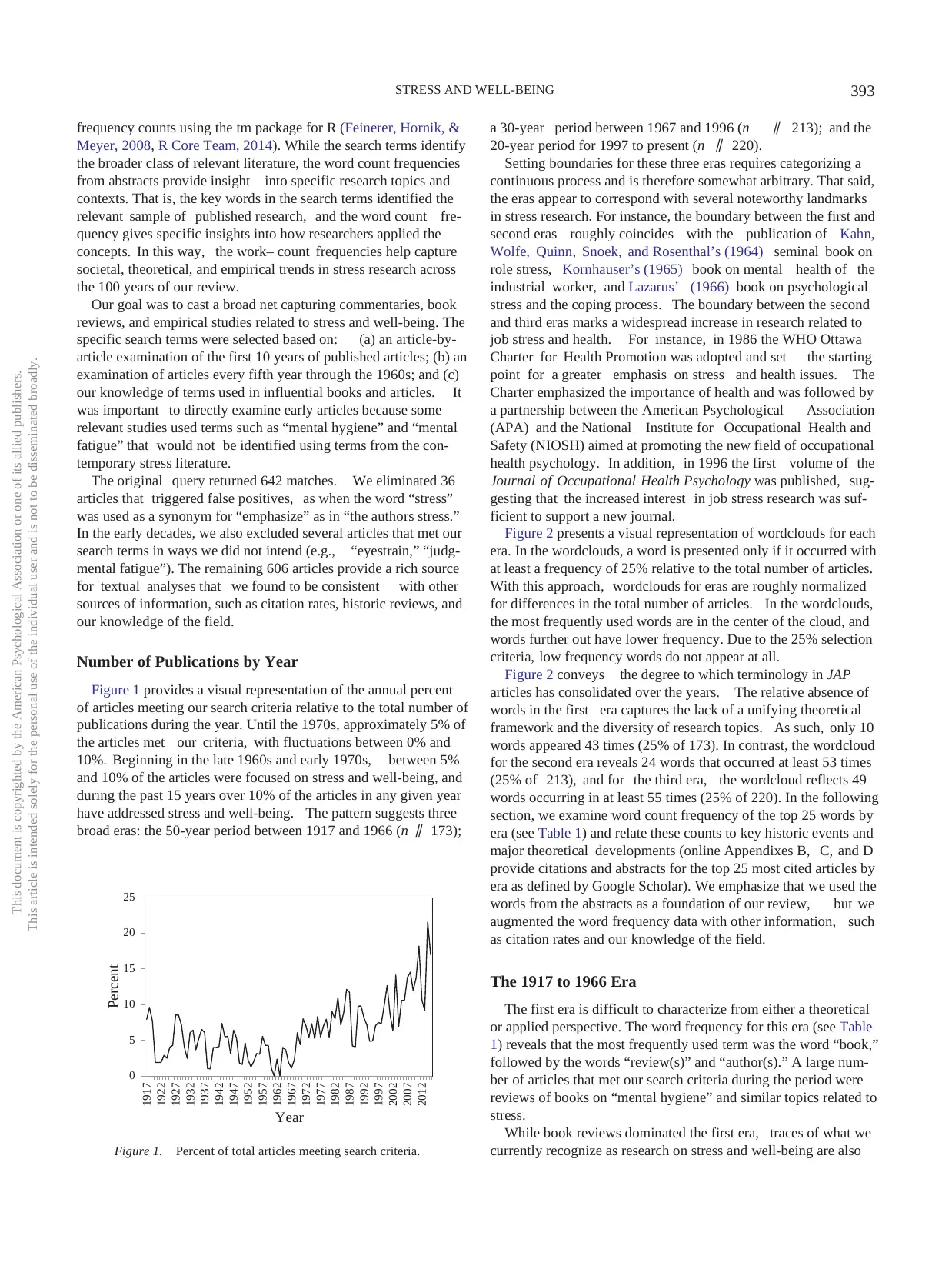

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the annual percent

of articles meeting our search criteria relative to the total number of

publications during the year. Until the 1970s, approximately 5% of

the articles met our criteria, with fluctuations between 0% and

10%. Beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, between 5%

and 10% of the articles were focused on stress and well-being, and

during the past 15 years over 10% of the articles in any given year

have addressed stress and well-being. The pattern suggests three

broad eras: the 50-year period between 1917 and 1966 (n ⫽ 173);

a 30-year period between 1967 and 1996 (n ⫽ 213); and the

20-year period for 1997 to present (n ⫽ 220).

Setting boundaries for these three eras requires categorizing a

continuous process and is therefore somewhat arbitrary. That said,

the eras appear to correspond with several noteworthy landmarks

in stress research. For instance, the boundary between the first and

second eras roughly coincides with the publication of Kahn,

Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, and Rosenthal’s (1964) seminal book on

role stress, Kornhauser’s (1965) book on mental health of the

industrial worker, and Lazarus’ (1966) book on psychological

stress and the coping process. The boundary between the second

and third eras marks a widespread increase in research related to

job stress and health. For instance, in 1986 the WHO Ottawa

Charter for Health Promotion was adopted and set the starting

point for a greater emphasis on stress and health issues. The

Charter emphasized the importance of health and was followed by

a partnership between the American Psychological Association

(APA) and the National Institute for Occupational Health and

Safety (NIOSH) aimed at promoting the new field of occupational

health psychology. In addition, in 1996 the first volume of the

Journal of Occupational Health Psychology was published, sug-

gesting that the increased interest in job stress research was suf-

ficient to support a new journal.

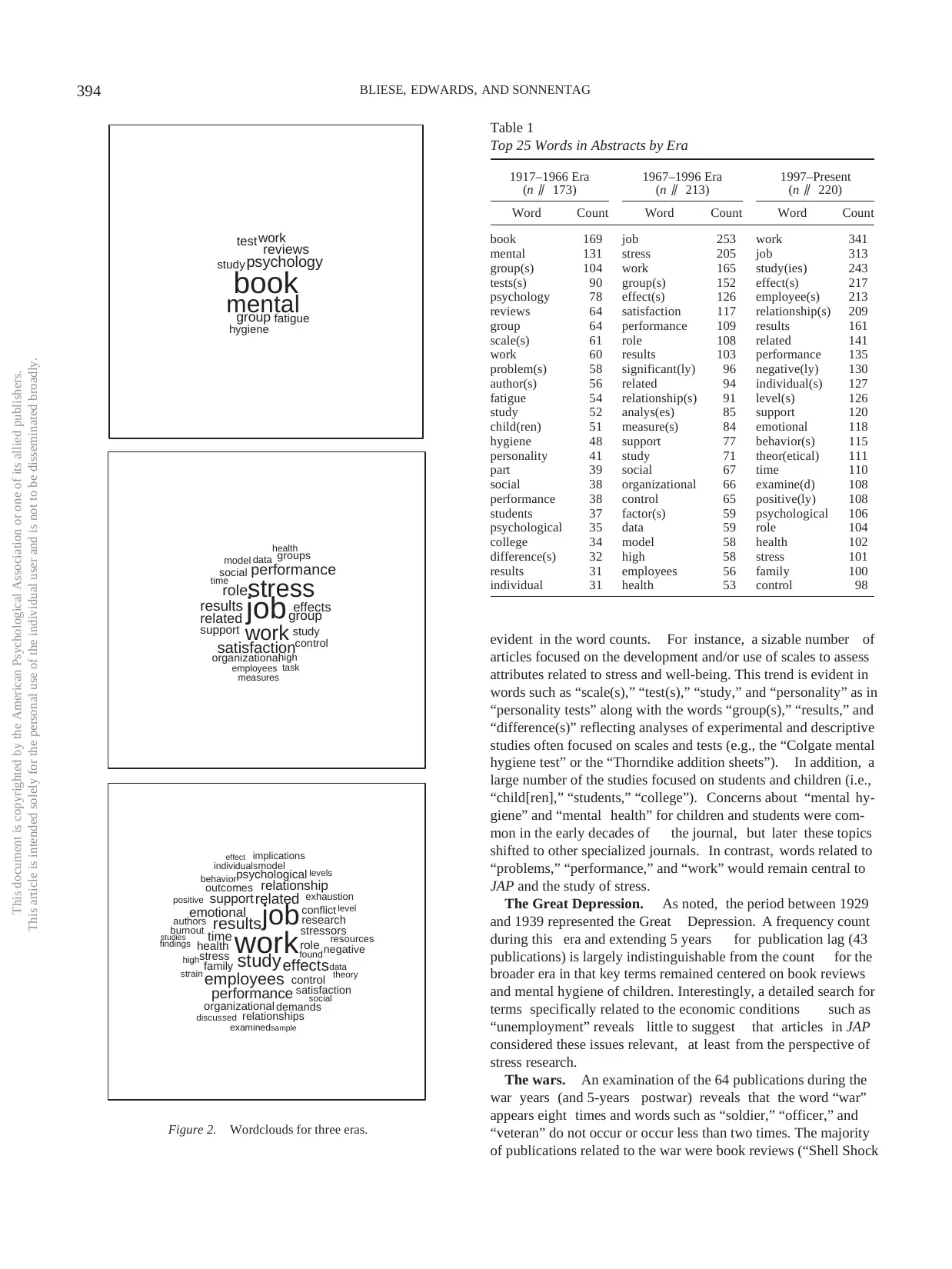

Figure 2 presents a visual representation of wordclouds for each

era. In the wordclouds, a word is presented only if it occurred with

at least a frequency of 25% relative to the total number of articles.

With this approach, wordclouds for eras are roughly normalized

for differences in the total number of articles. In the wordclouds,

the most frequently used words are in the center of the cloud, and

words further out have lower frequency. Due to the 25% selection

criteria, low frequency words do not appear at all.

Figure 2 conveys the degree to which terminology in JAP

articles has consolidated over the years. The relative absence of

words in the first era captures the lack of a unifying theoretical

framework and the diversity of research topics. As such, only 10

words appeared 43 times (25% of 173). In contrast, the wordcloud

for the second era reveals 24 words that occurred at least 53 times

(25% of 213), and for the third era, the wordcloud reflects 49

words occurring in at least 55 times (25% of 220). In the following

section, we examine word count frequency of the top 25 words by

era (see Table 1) and relate these counts to key historic events and

major theoretical developments (online Appendixes B, C, and D

provide citations and abstracts for the top 25 most cited articles by

era as defined by Google Scholar). We emphasize that we used the

words from the abstracts as a foundation of our review, but we

augmented the word frequency data with other information, such

as citation rates and our knowledge of the field.

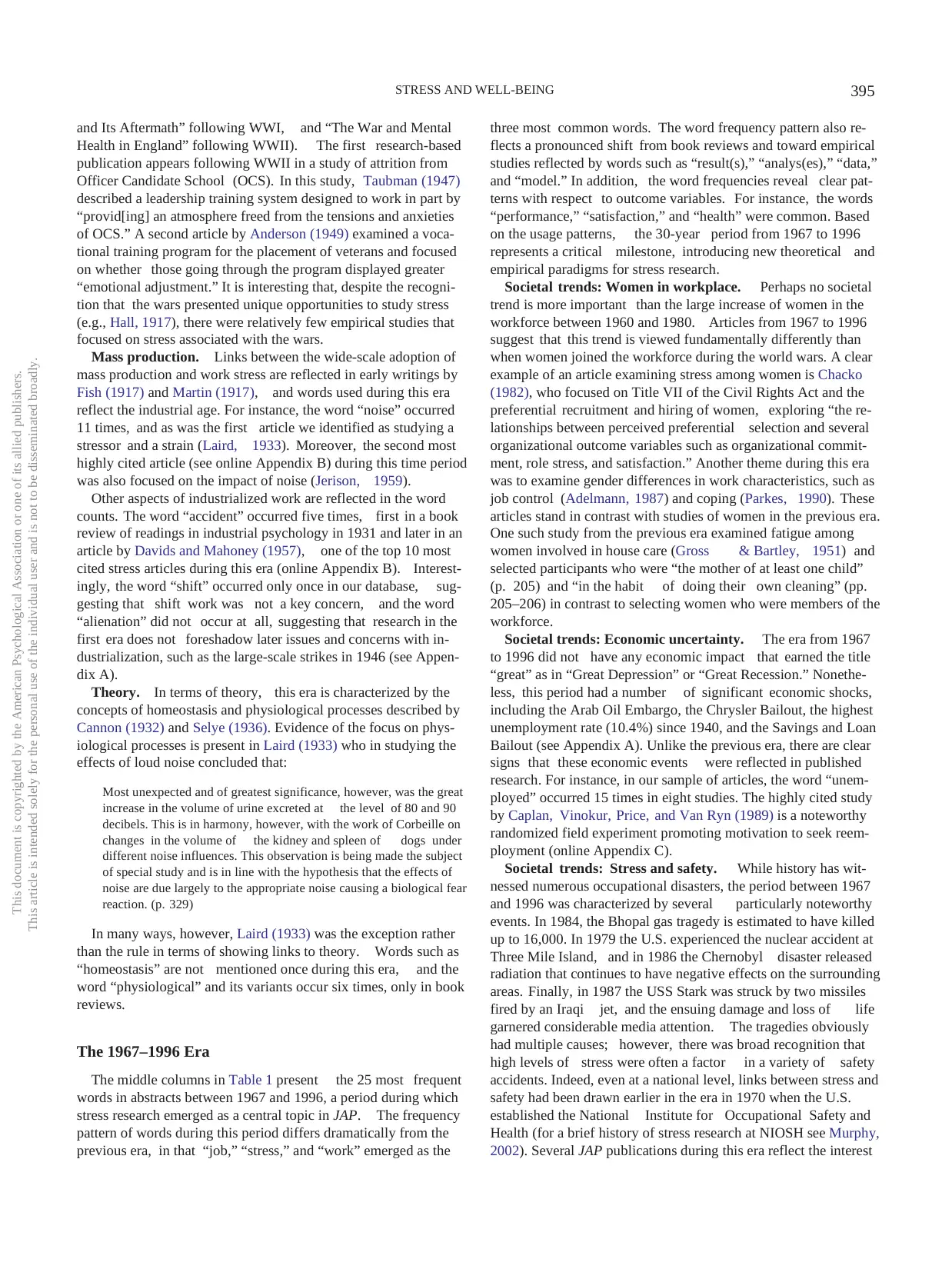

The 1917 to 1966 Era

The first era is difficult to characterize from either a theoretical

or applied perspective. The word frequency for this era (see Table

1) reveals that the most frequently used term was the word “book,”

followed by the words “review(s)” and “author(s).” A large num-

ber of articles that met our search criteria during the period were

reviews of books on “mental hygiene” and similar topics related to

stress.

While book reviews dominated the first era, traces of what we

currently recognize as research on stress and well-being are also

0

5

10

15

20

25

1917

1922

1927

1932

1937

1942

1947

1952

1957

1962

1967

1972

1977

1982

1987

1992

1997

2002

2007

2012

Percent

Year

Figure 1. Percent of total articles meeting search criteria.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

393STRESS AND WELL-BEING

Meyer, 2008, R Core Team, 2014). While the search terms identify

the broader class of relevant literature, the word count frequencies

from abstracts provide insight into specific research topics and

contexts. That is, the key words in the search terms identified the

relevant sample of published research, and the word count fre-

quency gives specific insights into how researchers applied the

concepts. In this way, the work– count frequencies help capture

societal, theoretical, and empirical trends in stress research across

the 100 years of our review.

Our goal was to cast a broad net capturing commentaries, book

reviews, and empirical studies related to stress and well-being. The

specific search terms were selected based on: (a) an article-by-

article examination of the first 10 years of published articles; (b) an

examination of articles every fifth year through the 1960s; and (c)

our knowledge of terms used in influential books and articles. It

was important to directly examine early articles because some

relevant studies used terms such as “mental hygiene” and “mental

fatigue” that would not be identified using terms from the con-

temporary stress literature.

The original query returned 642 matches. We eliminated 36

articles that triggered false positives, as when the word “stress”

was used as a synonym for “emphasize” as in “the authors stress.”

In the early decades, we also excluded several articles that met our

search terms in ways we did not intend (e.g., “eyestrain,” “judg-

mental fatigue”). The remaining 606 articles provide a rich source

for textual analyses that we found to be consistent with other

sources of information, such as citation rates, historic reviews, and

our knowledge of the field.

Number of Publications by Year

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the annual percent

of articles meeting our search criteria relative to the total number of

publications during the year. Until the 1970s, approximately 5% of

the articles met our criteria, with fluctuations between 0% and

10%. Beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, between 5%

and 10% of the articles were focused on stress and well-being, and

during the past 15 years over 10% of the articles in any given year

have addressed stress and well-being. The pattern suggests three

broad eras: the 50-year period between 1917 and 1966 (n ⫽ 173);

a 30-year period between 1967 and 1996 (n ⫽ 213); and the

20-year period for 1997 to present (n ⫽ 220).

Setting boundaries for these three eras requires categorizing a

continuous process and is therefore somewhat arbitrary. That said,

the eras appear to correspond with several noteworthy landmarks

in stress research. For instance, the boundary between the first and

second eras roughly coincides with the publication of Kahn,

Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, and Rosenthal’s (1964) seminal book on

role stress, Kornhauser’s (1965) book on mental health of the

industrial worker, and Lazarus’ (1966) book on psychological

stress and the coping process. The boundary between the second

and third eras marks a widespread increase in research related to

job stress and health. For instance, in 1986 the WHO Ottawa

Charter for Health Promotion was adopted and set the starting

point for a greater emphasis on stress and health issues. The

Charter emphasized the importance of health and was followed by

a partnership between the American Psychological Association

(APA) and the National Institute for Occupational Health and

Safety (NIOSH) aimed at promoting the new field of occupational

health psychology. In addition, in 1996 the first volume of the

Journal of Occupational Health Psychology was published, sug-

gesting that the increased interest in job stress research was suf-

ficient to support a new journal.

Figure 2 presents a visual representation of wordclouds for each

era. In the wordclouds, a word is presented only if it occurred with

at least a frequency of 25% relative to the total number of articles.

With this approach, wordclouds for eras are roughly normalized

for differences in the total number of articles. In the wordclouds,

the most frequently used words are in the center of the cloud, and

words further out have lower frequency. Due to the 25% selection

criteria, low frequency words do not appear at all.

Figure 2 conveys the degree to which terminology in JAP

articles has consolidated over the years. The relative absence of

words in the first era captures the lack of a unifying theoretical

framework and the diversity of research topics. As such, only 10

words appeared 43 times (25% of 173). In contrast, the wordcloud

for the second era reveals 24 words that occurred at least 53 times

(25% of 213), and for the third era, the wordcloud reflects 49

words occurring in at least 55 times (25% of 220). In the following

section, we examine word count frequency of the top 25 words by

era (see Table 1) and relate these counts to key historic events and

major theoretical developments (online Appendixes B, C, and D

provide citations and abstracts for the top 25 most cited articles by

era as defined by Google Scholar). We emphasize that we used the

words from the abstracts as a foundation of our review, but we

augmented the word frequency data with other information, such

as citation rates and our knowledge of the field.

The 1917 to 1966 Era

The first era is difficult to characterize from either a theoretical

or applied perspective. The word frequency for this era (see Table

1) reveals that the most frequently used term was the word “book,”

followed by the words “review(s)” and “author(s).” A large num-

ber of articles that met our search criteria during the period were

reviews of books on “mental hygiene” and similar topics related to

stress.

While book reviews dominated the first era, traces of what we

currently recognize as research on stress and well-being are also

0

5

10

15

20

25

1917

1922

1927

1932

1937

1942

1947

1952

1957

1962

1967

1972

1977

1982

1987

1992

1997

2002

2007

2012

Percent

Year

Figure 1. Percent of total articles meeting search criteria.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

393STRESS AND WELL-BEING

evident in the word counts. For instance, a sizable number of

articles focused on the development and/or use of scales to assess

attributes related to stress and well-being. This trend is evident in

words such as “scale(s),” “test(s),” “study,” and “personality” as in

“personality tests” along with the words “group(s),” “results,” and

“difference(s)” reflecting analyses of experimental and descriptive

studies often focused on scales and tests (e.g., the “Colgate mental

hygiene test” or the “Thorndike addition sheets”). In addition, a

large number of the studies focused on students and children (i.e.,

“child[ren],” “students,” “college”). Concerns about “mental hy-

giene” and “mental health” for children and students were com-

mon in the early decades of the journal, but later these topics

shifted to other specialized journals. In contrast, words related to

“problems,” “performance,” and “work” would remain central to

JAP and the study of stress.

The Great Depression. As noted, the period between 1929

and 1939 represented the Great Depression. A frequency count

during this era and extending 5 years for publication lag (43

publications) is largely indistinguishable from the count for the

broader era in that key terms remained centered on book reviews

and mental hygiene of children. Interestingly, a detailed search for

terms specifically related to the economic conditions such as

“unemployment” reveals little to suggest that articles in JAP

considered these issues relevant, at least from the perspective of

stress research.

The wars. An examination of the 64 publications during the

war years (and 5-years postwar) reveals that the word “war”

appears eight times and words such as “soldier,” “officer,” and

“veteran” do not occur or occur less than two times. The majority

of publications related to the war were book reviews (“Shell Shock

book

mental

psychology

group

reviews

worktest

fatigue

study

hygiene

job

stress

work

satisfaction

performance

role

results

related group

effects

support study

social

organizational

control

groupsdata

high

model

employees

health

measures

task

time

work

job

study

results

employeeseffects

related

performance

relationship

support

emotional

time

psychological

rolehealth

stress

family

control

organizational

stressors

research

outcomes

relationships

satisfaction

conflict

demands

negative

authors

exhaustion

resources

model

burnout

implications

examined

found

individuals

behavior

high

strain data

theory

levels

discussed

positive

social

findings

level

effect

sample

studies

Figure 2. Wordclouds for three eras.

Table 1

Top 25 Words in Abstracts by Era

1917–1966 Era

(n ⫽ 173)

1967–1996 Era

(n ⫽ 213)

1997–Present

(n ⫽ 220)

Word Count Word Count Word Count

book 169 job 253 work 341

mental 131 stress 205 job 313

group(s) 104 work 165 study(ies) 243

tests(s) 90 group(s) 152 effect(s) 217

psychology 78 effect(s) 126 employee(s) 213

reviews 64 satisfaction 117 relationship(s) 209

group 64 performance 109 results 161

scale(s) 61 role 108 related 141

work 60 results 103 performance 135

problem(s) 58 significant(ly) 96 negative(ly) 130

author(s) 56 related 94 individual(s) 127

fatigue 54 relationship(s) 91 level(s) 126

study 52 analys(es) 85 support 120

child(ren) 51 measure(s) 84 emotional 118

hygiene 48 support 77 behavior(s) 115

personality 41 study 71 theor(etical) 111

part 39 social 67 time 110

social 38 organizational 66 examine(d) 108

performance 38 control 65 positive(ly) 108

students 37 factor(s) 59 psychological 106

psychological 35 data 59 role 104

college 34 model 58 health 102

difference(s) 32 high 58 stress 101

results 31 employees 56 family 100

individual 31 health 53 control 98

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

394 BLIESE, EDWARDS, AND SONNENTAG

articles focused on the development and/or use of scales to assess

attributes related to stress and well-being. This trend is evident in

words such as “scale(s),” “test(s),” “study,” and “personality” as in

“personality tests” along with the words “group(s),” “results,” and

“difference(s)” reflecting analyses of experimental and descriptive

studies often focused on scales and tests (e.g., the “Colgate mental

hygiene test” or the “Thorndike addition sheets”). In addition, a

large number of the studies focused on students and children (i.e.,

“child[ren],” “students,” “college”). Concerns about “mental hy-

giene” and “mental health” for children and students were com-

mon in the early decades of the journal, but later these topics

shifted to other specialized journals. In contrast, words related to

“problems,” “performance,” and “work” would remain central to

JAP and the study of stress.

The Great Depression. As noted, the period between 1929