Sun Safety in Construction: Importance, Research, and Strategies

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|14

|8096

|129

AI Summary

This article discusses the importance of sun safety in construction, research on the topic, and different research strategies to tackle the issue. It includes a review of a published paper, literature review, analysis of qualitative and quantitative data, and types of research strategies. The article also provides initial research ideas and concludes with references and an appendix.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

SUN SAFETY IN CONSTRUCTION 1

Sun Safety in Construction

Sun Safety in Construction

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

SUN SAFETY IN CONSTRUCTION 2

Contents

Research on Sun Safety in construction.....................................................................................................................3

Review of Published paper........................................................................................................................................3

Literature Review......................................................................................................................................................3

Importance of literature review..................................................................................................................................3

Analysis of qualitative and quantitative data.............................................................................................................3

Qualitative data..........................................................................................................................................................3

Quantitative data........................................................................................................................................................4

Difference between Quantitative and Qualitative data...............................................................................................4

Types of research strategies.......................................................................................................................................4

Qualitative research strategy......................................................................................................................................4

Quantitative research strategy....................................................................................................................................4

Descriptive research strategy.....................................................................................................................................4

Analytic research strategy..........................................................................................................................................4

Applied research strategy..........................................................................................................................................4

Critical research strategy...........................................................................................................................................4

Initial research ideas..................................................................................................................................................4

Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................................5

References.................................................................................................................................................................6

Appendix................................................................................................................................................................... 7

Contents

Research on Sun Safety in construction.....................................................................................................................3

Review of Published paper........................................................................................................................................3

Literature Review......................................................................................................................................................3

Importance of literature review..................................................................................................................................3

Analysis of qualitative and quantitative data.............................................................................................................3

Qualitative data..........................................................................................................................................................3

Quantitative data........................................................................................................................................................4

Difference between Quantitative and Qualitative data...............................................................................................4

Types of research strategies.......................................................................................................................................4

Qualitative research strategy......................................................................................................................................4

Quantitative research strategy....................................................................................................................................4

Descriptive research strategy.....................................................................................................................................4

Analytic research strategy..........................................................................................................................................4

Applied research strategy..........................................................................................................................................4

Critical research strategy...........................................................................................................................................4

Initial research ideas..................................................................................................................................................4

Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................................5

References.................................................................................................................................................................6

Appendix................................................................................................................................................................... 7

SUN SAFETY IN CONSTRUCTION 3

Research on Sun Safety in construction

Review of Published paper

The title of this paper is Sun safety in construction: a UK intervention study was written by J. Houdmont, P. Madgwick, and

R. Randall. According to J. Houdmont, sun safety in UK construction has given skin cancer to sun exposure that is relative to

other occupational. The aim of this journal paper is to determine a change in sun safety knowledge and provide a proper

training to a construction worker. In which a number of intervention group that reported correct knowledge of sun safety was

not greater than to baseline. The biggest change in the intervention group is to use a shade when workers working in the sun

(Oxford academic, 2016).

Solar ultraviolet ray is the main reason to development of skin cancer problem. According to the data of 2010, solar ultraviolet

ray was responsible for around 90% of cases of melanoma in the UK. Skin cancer is a common problem in the UK, in

England around 56% increases in skin cancer between 2002 and 2011 (Parkin et al., 2011). The incidence rate of skin cancer

in the UK rising faster as compared to Europe. According to the THOR organization, industry workers in the UK whose age is

below 65 raised standardized ration as compared to all other industries. A total of 1279 workers completed baseline in which

around 71% of workers giving contact details. In the UK solar ultraviolet ray is main cause to raise skin cancer problem in

construction workers.

Literature Review

A literature review is a type of review article which includes knowledge, theoretical, and methodological of a particular topic.

A literature review is a type of scholarly paper which is used to give a review on a particular topic. It is also a part of a

graduate student, including in a journal article. A literature review is also provided research proposal of any journal paper.

There are four types of literature review used in research such as evaluative, instrumental, exploratory, and systematic review.

Importance of literature review

There are following importance of literature review-

Provide a brief summary of a research topic

Provide relationship of each work to other people

Identify a new path for prior research

Locate own research within the context

It creates a report with an audience

Identify data source of researched topic

Formulate research problem

Ultraviolet radiation is the main reason for skin cancer in the UK. It is calculated that UVR poses around 65% of skin cancer,

and around 99% of non-melanoma skin cancer (Armstrong, 2004). Scientists found links between MSC, NMSC, and sun

exposure, where MSC and BCC associated with sun and SSC is associated with chronic exposure (Berwick et al., 2009). In

UK skin cancer is a common type of problem, around 100,000 cases of non-melanoma cancer and around 12,818 cases of

melanoma cancer were found in 2010 (Cancer Research UK, 2012). In 2010, almost 2,749 people in the UK died from

melanoma skin cancer. According to cancer registration data, there were almost 5,440 skin cancer cases registered in England

(National Statistics, 2013).

Analysis of qualitative and quantitative data

Qualitative data

Qualitative data is defined as a data that approximates but it does not determine the properties, attributes, and characteristics

of a phenomenon. Qualitative data is used to determine where quantitative data defines. It is a type of information that is

unable to measure, and its analysis that which research performed last month. Qualitative data deals with an observation that

can be obtained through senses elements such as touch, taste, and hearing. There are many qualitative observations such as for

instance, textures, colors, and shape of an object. It cannot be expressed but generally considered on scales such as socieo

economic, religious preference, and gender.

Examples: Sight, touch, hearing, and taste.

Research on Sun Safety in construction

Review of Published paper

The title of this paper is Sun safety in construction: a UK intervention study was written by J. Houdmont, P. Madgwick, and

R. Randall. According to J. Houdmont, sun safety in UK construction has given skin cancer to sun exposure that is relative to

other occupational. The aim of this journal paper is to determine a change in sun safety knowledge and provide a proper

training to a construction worker. In which a number of intervention group that reported correct knowledge of sun safety was

not greater than to baseline. The biggest change in the intervention group is to use a shade when workers working in the sun

(Oxford academic, 2016).

Solar ultraviolet ray is the main reason to development of skin cancer problem. According to the data of 2010, solar ultraviolet

ray was responsible for around 90% of cases of melanoma in the UK. Skin cancer is a common problem in the UK, in

England around 56% increases in skin cancer between 2002 and 2011 (Parkin et al., 2011). The incidence rate of skin cancer

in the UK rising faster as compared to Europe. According to the THOR organization, industry workers in the UK whose age is

below 65 raised standardized ration as compared to all other industries. A total of 1279 workers completed baseline in which

around 71% of workers giving contact details. In the UK solar ultraviolet ray is main cause to raise skin cancer problem in

construction workers.

Literature Review

A literature review is a type of review article which includes knowledge, theoretical, and methodological of a particular topic.

A literature review is a type of scholarly paper which is used to give a review on a particular topic. It is also a part of a

graduate student, including in a journal article. A literature review is also provided research proposal of any journal paper.

There are four types of literature review used in research such as evaluative, instrumental, exploratory, and systematic review.

Importance of literature review

There are following importance of literature review-

Provide a brief summary of a research topic

Provide relationship of each work to other people

Identify a new path for prior research

Locate own research within the context

It creates a report with an audience

Identify data source of researched topic

Formulate research problem

Ultraviolet radiation is the main reason for skin cancer in the UK. It is calculated that UVR poses around 65% of skin cancer,

and around 99% of non-melanoma skin cancer (Armstrong, 2004). Scientists found links between MSC, NMSC, and sun

exposure, where MSC and BCC associated with sun and SSC is associated with chronic exposure (Berwick et al., 2009). In

UK skin cancer is a common type of problem, around 100,000 cases of non-melanoma cancer and around 12,818 cases of

melanoma cancer were found in 2010 (Cancer Research UK, 2012). In 2010, almost 2,749 people in the UK died from

melanoma skin cancer. According to cancer registration data, there were almost 5,440 skin cancer cases registered in England

(National Statistics, 2013).

Analysis of qualitative and quantitative data

Qualitative data

Qualitative data is defined as a data that approximates but it does not determine the properties, attributes, and characteristics

of a phenomenon. Qualitative data is used to determine where quantitative data defines. It is a type of information that is

unable to measure, and its analysis that which research performed last month. Qualitative data deals with an observation that

can be obtained through senses elements such as touch, taste, and hearing. There are many qualitative observations such as for

instance, textures, colors, and shape of an object. It cannot be expressed but generally considered on scales such as socieo

economic, religious preference, and gender.

Examples: Sight, touch, hearing, and taste.

SUN SAFETY IN CONSTRUCTION 4

Quantitative data

Quantitative data is defined as a data that can be verified and is responsible for statistical manipulation. It is used where

qualitative data describes. It can be expressed as a number; examples of quantitative data are a number of hours of study, and

scores archive in tests. It is used to verify any problem by producing numerical data which can be transforming into statistics

data. It includes different types of surveys such as online, paper, kiosk, and mobile surveys.

Examples: research on the percentage amount of elements on earth atmosphere, number of patients have to wait 2 hours in a

waiting room in a hospital, and research on the stock market of any company

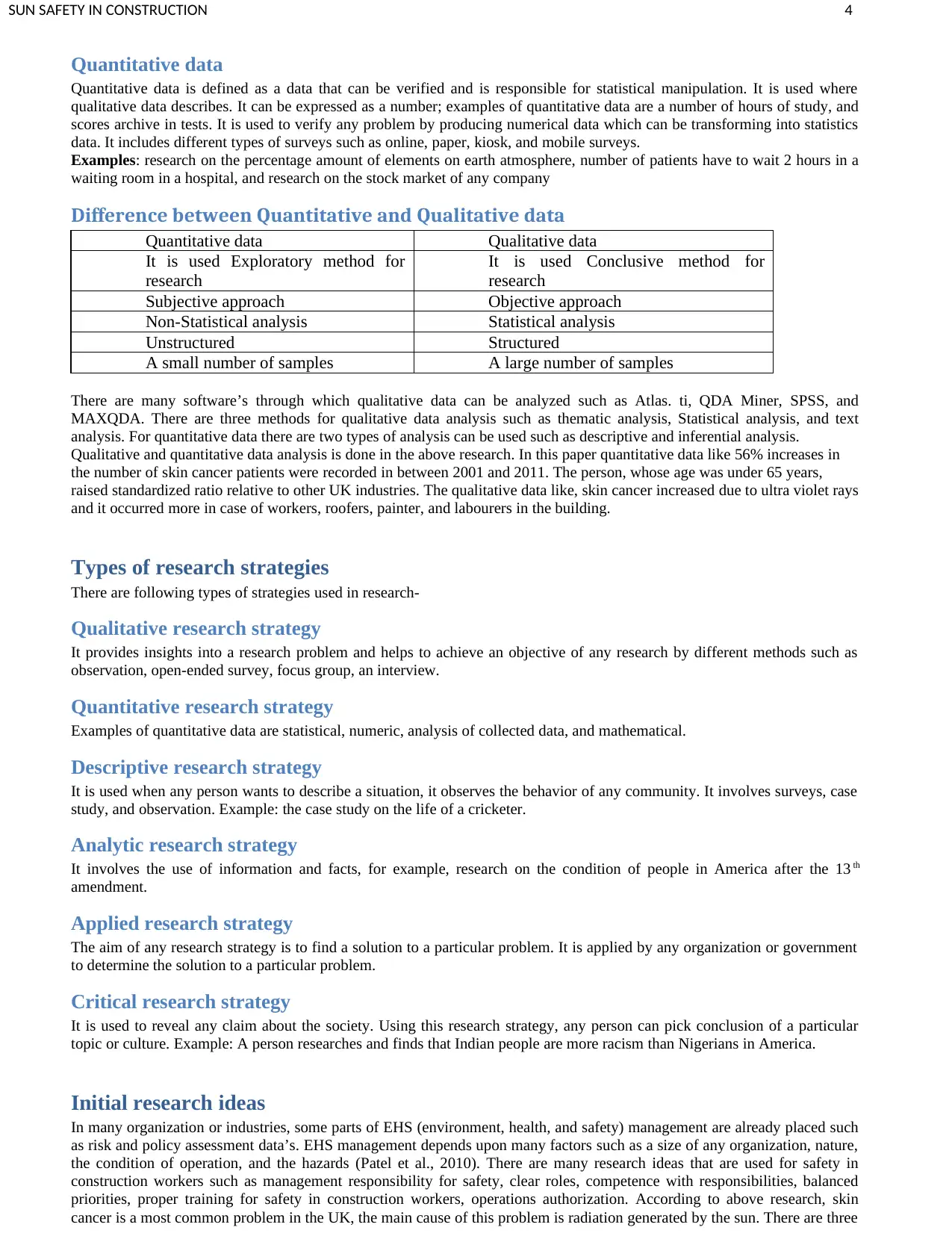

Difference between Quantitative and Qualitative data

Quantitative data Qualitative data

It is used Exploratory method for

research

It is used Conclusive method for

research

Subjective approach Objective approach

Non-Statistical analysis Statistical analysis

Unstructured Structured

A small number of samples A large number of samples

There are many software’s through which qualitative data can be analyzed such as Atlas. ti, QDA Miner, SPSS, and

MAXQDA. There are three methods for qualitative data analysis such as thematic analysis, Statistical analysis, and text

analysis. For quantitative data there are two types of analysis can be used such as descriptive and inferential analysis.

Qualitative and quantitative data analysis is done in the above research. In this paper quantitative data like 56% increases in

the number of skin cancer patients were recorded in between 2001 and 2011. The person, whose age was under 65 years,

raised standardized ratio relative to other UK industries. The qualitative data like, skin cancer increased due to ultra violet rays

and it occurred more in case of workers, roofers, painter, and labourers in the building.

Types of research strategies

There are following types of strategies used in research-

Qualitative research strategy

It provides insights into a research problem and helps to achieve an objective of any research by different methods such as

observation, open-ended survey, focus group, an interview.

Quantitative research strategy

Examples of quantitative data are statistical, numeric, analysis of collected data, and mathematical.

Descriptive research strategy

It is used when any person wants to describe a situation, it observes the behavior of any community. It involves surveys, case

study, and observation. Example: the case study on the life of a cricketer.

Analytic research strategy

It involves the use of information and facts, for example, research on the condition of people in America after the 13 th

amendment.

Applied research strategy

The aim of any research strategy is to find a solution to a particular problem. It is applied by any organization or government

to determine the solution to a particular problem.

Critical research strategy

It is used to reveal any claim about the society. Using this research strategy, any person can pick conclusion of a particular

topic or culture. Example: A person researches and finds that Indian people are more racism than Nigerians in America.

Initial research ideas

In many organization or industries, some parts of EHS (environment, health, and safety) management are already placed such

as risk and policy assessment data’s. EHS management depends upon many factors such as a size of any organization, nature,

the condition of operation, and the hazards (Patel et al., 2010). There are many research ideas that are used for safety in

construction workers such as management responsibility for safety, clear roles, competence with responsibilities, balanced

priorities, proper training for safety in construction workers, operations authorization. According to above research, skin

cancer is a most common problem in the UK, the main cause of this problem is radiation generated by the sun. There are three

Quantitative data

Quantitative data is defined as a data that can be verified and is responsible for statistical manipulation. It is used where

qualitative data describes. It can be expressed as a number; examples of quantitative data are a number of hours of study, and

scores archive in tests. It is used to verify any problem by producing numerical data which can be transforming into statistics

data. It includes different types of surveys such as online, paper, kiosk, and mobile surveys.

Examples: research on the percentage amount of elements on earth atmosphere, number of patients have to wait 2 hours in a

waiting room in a hospital, and research on the stock market of any company

Difference between Quantitative and Qualitative data

Quantitative data Qualitative data

It is used Exploratory method for

research

It is used Conclusive method for

research

Subjective approach Objective approach

Non-Statistical analysis Statistical analysis

Unstructured Structured

A small number of samples A large number of samples

There are many software’s through which qualitative data can be analyzed such as Atlas. ti, QDA Miner, SPSS, and

MAXQDA. There are three methods for qualitative data analysis such as thematic analysis, Statistical analysis, and text

analysis. For quantitative data there are two types of analysis can be used such as descriptive and inferential analysis.

Qualitative and quantitative data analysis is done in the above research. In this paper quantitative data like 56% increases in

the number of skin cancer patients were recorded in between 2001 and 2011. The person, whose age was under 65 years,

raised standardized ratio relative to other UK industries. The qualitative data like, skin cancer increased due to ultra violet rays

and it occurred more in case of workers, roofers, painter, and labourers in the building.

Types of research strategies

There are following types of strategies used in research-

Qualitative research strategy

It provides insights into a research problem and helps to achieve an objective of any research by different methods such as

observation, open-ended survey, focus group, an interview.

Quantitative research strategy

Examples of quantitative data are statistical, numeric, analysis of collected data, and mathematical.

Descriptive research strategy

It is used when any person wants to describe a situation, it observes the behavior of any community. It involves surveys, case

study, and observation. Example: the case study on the life of a cricketer.

Analytic research strategy

It involves the use of information and facts, for example, research on the condition of people in America after the 13 th

amendment.

Applied research strategy

The aim of any research strategy is to find a solution to a particular problem. It is applied by any organization or government

to determine the solution to a particular problem.

Critical research strategy

It is used to reveal any claim about the society. Using this research strategy, any person can pick conclusion of a particular

topic or culture. Example: A person researches and finds that Indian people are more racism than Nigerians in America.

Initial research ideas

In many organization or industries, some parts of EHS (environment, health, and safety) management are already placed such

as risk and policy assessment data’s. EHS management depends upon many factors such as a size of any organization, nature,

the condition of operation, and the hazards (Patel et al., 2010). There are many research ideas that are used for safety in

construction workers such as management responsibility for safety, clear roles, competence with responsibilities, balanced

priorities, proper training for safety in construction workers, operations authorization. According to above research, skin

cancer is a most common problem in the UK, the main cause of this problem is radiation generated by the sun. There are three

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

SUN SAFETY IN CONSTRUCTION 5

types of radiation generated by the sun such as infra-red, visible light, and ultraviolet radiation. Ultraviolet radiation is the

main cause of skin cancer in the UK (Payne et al., 2013). There are many research ideas to avoid skin cancer in construction

workers such as using sunscreen, wear sunglasses, avoid mid-day, use policies and regulation, use EHS management and

policies to provide sun safety in construction workers, and wear long clothing (Safety and health practitioner, 2015).

Conclusion

A research proposal is a type of process which is used to propose a research idea, review of research, applying different types

of research strategies, and finding the result. In this research paper, one journal paper related to safety measures was discussed

and analyzed. Literature related to this paper was reviewed thoroughly. There are many types of research strategies are used

such as quantitative research, qualitative research, critical research, analytic research, and applied research. In this research

paper, two types of research strategies are analysed such as quantitative and qualitative research. Different types of research

idea related to safety, health, and environment were discussed.

types of radiation generated by the sun such as infra-red, visible light, and ultraviolet radiation. Ultraviolet radiation is the

main cause of skin cancer in the UK (Payne et al., 2013). There are many research ideas to avoid skin cancer in construction

workers such as using sunscreen, wear sunglasses, avoid mid-day, use policies and regulation, use EHS management and

policies to provide sun safety in construction workers, and wear long clothing (Safety and health practitioner, 2015).

Conclusion

A research proposal is a type of process which is used to propose a research idea, review of research, applying different types

of research strategies, and finding the result. In this research paper, one journal paper related to safety measures was discussed

and analyzed. Literature related to this paper was reviewed thoroughly. There are many types of research strategies are used

such as quantitative research, qualitative research, critical research, analytic research, and applied research. In this research

paper, two types of research strategies are analysed such as quantitative and qualitative research. Different types of research

idea related to safety, health, and environment were discussed.

SUN SAFETY IN CONSTRUCTION 6

References

Armstrong, B. (2004) how sun exposure causes skin cancer: an epidemiological perspective. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic

Publishers.

Berwick, M., Lachiewicz, A., Pestak, C., and Thomas, N. (2009) Solar UV exposure and mortality from skin tumors. New

York: Landes Bioscience & Springer Science.

Cancer Research UK (2012) Skin cancer statistics [online]. Available from:

http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/skin/ [Accessed 21/06/18].

Culham centre fusion energy (2018) Safety, health & environment policy [online]. Available from:

http://www.ccfe.ac.uk/she.aspx [Accessed 21/06/18].

Office for National Statistics (2013) Cancer Registration Statistics [online]. Available from:

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_315795.pdf [Accessed 21/06/18].

Oxford academic (2016) Sun safety in construction: a UK intervention study [online]. Available from:

https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article/66/1/20/2750628 [Accessed 21/06/18].

Parkin, D., Mesher, D., and Sasieni, P. (2011) Cancers attributable to solar (ultraviolet) radiation exposure in the UK in 2010.

British Journal of Cancer, 105, pp. 566-569.

Patel, S., Nijhawan, R., Stechschulte, S., Parmet, Y., Rouhani, P., Kirsner, R., and Hu, S. (2010) Skin cancer awareness,

attitude, and sun protection behavior among medical students at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Archives

of Dermatology, 146, pp. 797-800.

Payne, N., Jones, F., and Harris, P. (2013) Employees' perceptions of the impact of work on health behaviors. Journal of

Health Psychology, 17, pp. 887-899.

Safety and health practitioner (2015) Sun exposure and skin cancer health advice for outdoor workers [online]. Available

from: https://www.shponline.co.uk/sun-exposure-skin-cancer-health-advice-outdoor-workers/ [Accessed 21/06/18].

References

Armstrong, B. (2004) how sun exposure causes skin cancer: an epidemiological perspective. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic

Publishers.

Berwick, M., Lachiewicz, A., Pestak, C., and Thomas, N. (2009) Solar UV exposure and mortality from skin tumors. New

York: Landes Bioscience & Springer Science.

Cancer Research UK (2012) Skin cancer statistics [online]. Available from:

http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/skin/ [Accessed 21/06/18].

Culham centre fusion energy (2018) Safety, health & environment policy [online]. Available from:

http://www.ccfe.ac.uk/she.aspx [Accessed 21/06/18].

Office for National Statistics (2013) Cancer Registration Statistics [online]. Available from:

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_315795.pdf [Accessed 21/06/18].

Oxford academic (2016) Sun safety in construction: a UK intervention study [online]. Available from:

https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article/66/1/20/2750628 [Accessed 21/06/18].

Parkin, D., Mesher, D., and Sasieni, P. (2011) Cancers attributable to solar (ultraviolet) radiation exposure in the UK in 2010.

British Journal of Cancer, 105, pp. 566-569.

Patel, S., Nijhawan, R., Stechschulte, S., Parmet, Y., Rouhani, P., Kirsner, R., and Hu, S. (2010) Skin cancer awareness,

attitude, and sun protection behavior among medical students at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Archives

of Dermatology, 146, pp. 797-800.

Payne, N., Jones, F., and Harris, P. (2013) Employees' perceptions of the impact of work on health behaviors. Journal of

Health Psychology, 17, pp. 887-899.

Safety and health practitioner (2015) Sun exposure and skin cancer health advice for outdoor workers [online]. Available

from: https://www.shponline.co.uk/sun-exposure-skin-cancer-health-advice-outdoor-workers/ [Accessed 21/06/18].

SUN SAFETY IN CONSTRUCTION 7

Occupational Medicine 2016;66:20–26

Advance Access publication 26 September 2015 doi:10.1093/occmed/kqv140

Appendix

Sun safety in construction: a UK intervention study

J. Houdmont1, P. Madgwick1 and R. Randall2

1Division of Psychiatry and Applied Psychology, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG8 1BB, UK,

2School of Business and Economics, Loughborough University, Loughborough LE11 3TU, UK.

Correspondence to: J. Houdmont, Division of Psychiatry and Applied Psychology, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham,

B Floor, Yang Fujia Building, Jubilee Campus, Wollaton Road, Nottingham NG8 1BB, UK. Tel: +44 (0)7977 142860;

fax: +44 (0)11 5846 6625; e-mail: jonathan.houdmont@nottingham.ac.uk

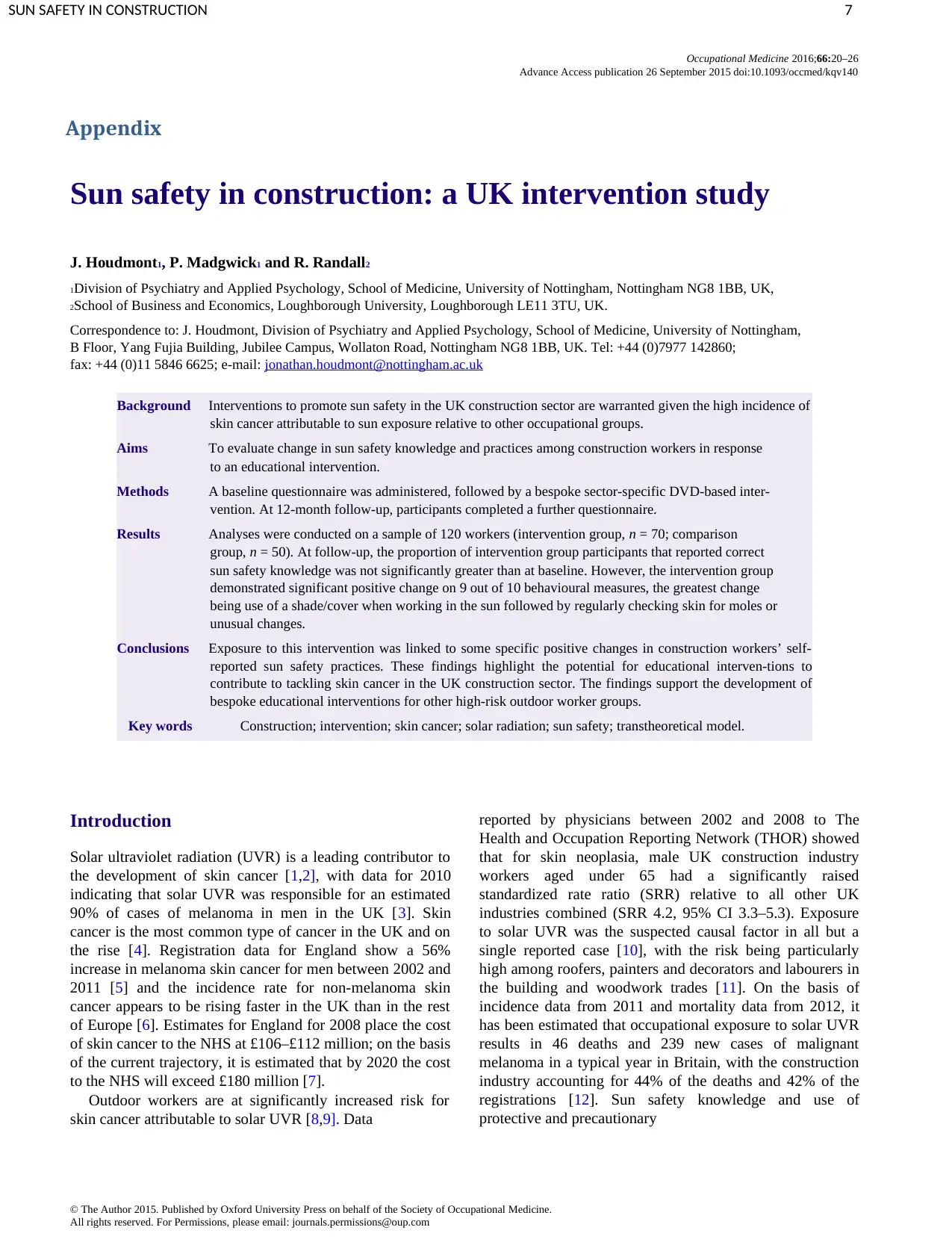

Background Interventions to promote sun safety in the UK construction sector are warranted given the high incidence of

skin cancer attributable to sun exposure relative to other occupational groups.

Aims To evaluate change in sun safety knowledge and practices among construction workers in response

to an educational intervention.

Methods A baseline questionnaire was administered, followed by a bespoke sector-specific DVD-based inter-

vention. At 12-month follow-up, participants completed a further questionnaire.

Results Analyses were conducted on a sample of 120 workers (intervention group, n = 70; comparison

group, n = 50). At follow-up, the proportion of intervention group participants that reported correct

sun safety knowledge was not significantly greater than at baseline. However, the intervention group

demonstrated significant positive change on 9 out of 10 behavioural measures, the greatest change

being use of a shade/cover when working in the sun followed by regularly checking skin for moles or

unusual changes.

Conclusions Exposure to this intervention was linked to some specific positive changes in construction workers’ self-

reported sun safety practices. These findings highlight the potential for educational interven-tions to

contribute to tackling skin cancer in the UK construction sector. The findings support the development of

bespoke educational interventions for other high-risk outdoor worker groups.

Key words Construction; intervention; skin cancer; solar radiation; sun safety; transtheoretical model.

Introduction

Solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is a leading contributor to

the development of skin cancer [1,2], with data for 2010

indicating that solar UVR was responsible for an estimated

90% of cases of melanoma in men in the UK [3]. Skin

cancer is the most common type of cancer in the UK and on

the rise [4]. Registration data for England show a 56%

increase in melanoma skin cancer for men between 2002 and

2011 [5] and the incidence rate for non-melanoma skin

cancer appears to be rising faster in the UK than in the rest

of Europe [6]. Estimates for England for 2008 place the cost

of skin cancer to the NHS at £106–£112 million; on the basis

of the current trajectory, it is estimated that by 2020 the cost

to the NHS will exceed £180 million [7].

Outdoor workers are at significantly increased risk for

skin cancer attributable to solar UVR [8,9]. Data

reported by physicians between 2002 and 2008 to The

Health and Occupation Reporting Network (THOR) showed

that for skin neoplasia, male UK construction industry

workers aged under 65 had a significantly raised

standardized rate ratio (SRR) relative to all other UK

industries combined (SRR 4.2, 95% CI 3.3–5.3). Exposure

to solar UVR was the suspected causal factor in all but a

single reported case [10], with the risk being particularly

high among roofers, painters and decorators and labourers in

the building and woodwork trades [11]. On the basis of

incidence data from 2011 and mortality data from 2012, it

has been estimated that occupational exposure to solar UVR

results in 46 deaths and 239 new cases of malignant

melanoma in a typical year in Britain, with the construction

industry accounting for 44% of the deaths and 42% of the

registrations [12]. Sun safety knowledge and use of

protective and precautionary

© The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society of Occupational Medicine.

All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

Occupational Medicine 2016;66:20–26

Advance Access publication 26 September 2015 doi:10.1093/occmed/kqv140

Appendix

Sun safety in construction: a UK intervention study

J. Houdmont1, P. Madgwick1 and R. Randall2

1Division of Psychiatry and Applied Psychology, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG8 1BB, UK,

2School of Business and Economics, Loughborough University, Loughborough LE11 3TU, UK.

Correspondence to: J. Houdmont, Division of Psychiatry and Applied Psychology, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham,

B Floor, Yang Fujia Building, Jubilee Campus, Wollaton Road, Nottingham NG8 1BB, UK. Tel: +44 (0)7977 142860;

fax: +44 (0)11 5846 6625; e-mail: jonathan.houdmont@nottingham.ac.uk

Background Interventions to promote sun safety in the UK construction sector are warranted given the high incidence of

skin cancer attributable to sun exposure relative to other occupational groups.

Aims To evaluate change in sun safety knowledge and practices among construction workers in response

to an educational intervention.

Methods A baseline questionnaire was administered, followed by a bespoke sector-specific DVD-based inter-

vention. At 12-month follow-up, participants completed a further questionnaire.

Results Analyses were conducted on a sample of 120 workers (intervention group, n = 70; comparison

group, n = 50). At follow-up, the proportion of intervention group participants that reported correct

sun safety knowledge was not significantly greater than at baseline. However, the intervention group

demonstrated significant positive change on 9 out of 10 behavioural measures, the greatest change

being use of a shade/cover when working in the sun followed by regularly checking skin for moles or

unusual changes.

Conclusions Exposure to this intervention was linked to some specific positive changes in construction workers’ self-

reported sun safety practices. These findings highlight the potential for educational interven-tions to

contribute to tackling skin cancer in the UK construction sector. The findings support the development of

bespoke educational interventions for other high-risk outdoor worker groups.

Key words Construction; intervention; skin cancer; solar radiation; sun safety; transtheoretical model.

Introduction

Solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is a leading contributor to

the development of skin cancer [1,2], with data for 2010

indicating that solar UVR was responsible for an estimated

90% of cases of melanoma in men in the UK [3]. Skin

cancer is the most common type of cancer in the UK and on

the rise [4]. Registration data for England show a 56%

increase in melanoma skin cancer for men between 2002 and

2011 [5] and the incidence rate for non-melanoma skin

cancer appears to be rising faster in the UK than in the rest

of Europe [6]. Estimates for England for 2008 place the cost

of skin cancer to the NHS at £106–£112 million; on the basis

of the current trajectory, it is estimated that by 2020 the cost

to the NHS will exceed £180 million [7].

Outdoor workers are at significantly increased risk for

skin cancer attributable to solar UVR [8,9]. Data

reported by physicians between 2002 and 2008 to The

Health and Occupation Reporting Network (THOR) showed

that for skin neoplasia, male UK construction industry

workers aged under 65 had a significantly raised

standardized rate ratio (SRR) relative to all other UK

industries combined (SRR 4.2, 95% CI 3.3–5.3). Exposure

to solar UVR was the suspected causal factor in all but a

single reported case [10], with the risk being particularly

high among roofers, painters and decorators and labourers in

the building and woodwork trades [11]. On the basis of

incidence data from 2011 and mortality data from 2012, it

has been estimated that occupational exposure to solar UVR

results in 46 deaths and 239 new cases of malignant

melanoma in a typical year in Britain, with the construction

industry accounting for 44% of the deaths and 42% of the

registrations [12]. Sun safety knowledge and use of

protective and precautionary

© The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society of Occupational Medicine.

All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

SUN SAFETY IN CONSTRUCTION 8

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

J. HOUDMONT ET AL.: SUN SAFETY IN THE UK CONSTRUCTION SECTOR 21

practices are low within the UK construction sector [13].

This indicates that relatively simple interventions could

result in significant positive health outcomes.

Sun safety interventions targeted at construction workers

and other manual outdoor worker groups (e.g. those laying

water pipes or electricity cables) have suc-cessfully

produced improvements in knowledge, attitudes and self-

reported behaviours [14–18]. However, no sun safety

intervention studies have been conducted in the UK

construction sector and it is not clear whether the existing

results can be generalized to this group. All pub-lished

intervention work has been conducted in Australia and

Israel, countries with more intense and prolonged periods of

sunshine than the UK, and findings therefore may not

transfer into the UK context. Furthermore, due to an

established sun safety culture in Australia [19], pre-

intervention attitudes towards sun protection might dif-fer

significantly from those held in the UK.

The high incidence of skin cancer attributable to solar

UVR among construction workers in the UK cou-pled with

their low levels of sun safety knowledge and associated risk-

reduction practices highlights a need for effective

interventions. The aim of this study there-fore was to

examine the effectiveness of a DVD-based sun safety

educational intervention designed specifi-cally for the UK

construction context. Several factors informed the decision

to focus on a film-based inter-vention. First, these have been

shown to be effective in promoting sunscreen knowledge

and usage and rated by study participants more positively

than alternative intervention media such as leaflets [20,21].

Second, film-based interventions can be created at relatively

little cost and delivered quickly in the workplace with little

disruption to work activities. Third, they can be administered

without expert knowledge on the part of the administrator.

Methods

The intervention was a 12-min DVD titled Sun Safety in

Construction: A Workplace Health Guidance Film. It was

developed as a low-cost educational intervention that could

be readily integrated into occupational safety and health

briefings on all types of construction sites. The intervention

is now freely available at http://www.notime-tolose.org.uk

as part of the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health’s

(IOSH) ‘No Time To Lose’ occu-pational cancer-reduction

campaign. The intervention addressed the risk of skin cancer

in the UK construc-tion sector, sun safety practices that

might be adopted on construction sites and self-checking of

skin for early signs of skin cancer.

Construction companies were contacted through the

personal contacts of the research team in addition to

advertisements in trade magazines and presenta-tions to

industry bodies. The baseline questionnaire

was administered in work time during health and safety

briefings in participating organizations (N = 22) between

May and August 2012. Questionnaire completion and return

was incentivized by a prize draw to win a sports car driving

experience. A stamped addressed envelope was provided

with each questionnaire for participants to return completed

questionnaires directly to the research team. The project

champion in each organization was provided with a copy of

the intervention and instructed to administer this only after

administration and comple-tion of the baseline

questionnaire; in most cases, these activities took place on

the same day or within a few days of one another.

Respondents who provided their contact details on the

baseline questionnaire were sent a follow-up questionnaire

along with a stamped addressed return envelope in the

summer of 2013. The mean lag between completion of

baseline and follow-up questionnaires was 12 months.

The study included an emergent comparison group,

comprising workers who completed the baseline ques-

tionnaire and follow-up questionnaire but who did not

receive the intervention [22]. Group membership was

established via an item on the follow-up question-naire that

assessed intervention exposure. Reasons for not having

received the intervention are unlikely to be related to self-

selection. Instead these included work scheduling

requirements, absence or working off-site at the time of

intervention administration, or staff turnover in the period

between baseline question-naire administration and

intervention administration. The emergent design was

adopted for three reasons. First, all participating companies

wanted to deliver the intervention as quickly as possible

ruling out the pos-sibility of populating a sizeable and

representative wait-list comparison group. Second, it was

thought unlikely that all employees who completed both the

baseline and follow-up questionnaires would be present on

the day of intervention administration for operational rea-

sons and due to the transitory nature of the workforce. These

reasons for participants being members of the comparison

group were unlikely to be related to inter-vention

effectiveness. Third, evidence from previous sun safety

intervention studies suggests that it is typi-cal that some

participating organizations fail to cor-rectly administer the

intervention [23]. Therefore, the design reduced the risk of a

type III error (erroneously concluding that an intervention

was unsuccessful when many participants had not received

the intervention as intended).

Respondents’ sun safety knowledge was assessed using

five items (Table 2) adapted from Patel et al. [24].

Respondents indicated whether they agreed or disa-greed

with each statement. We also examined respond-ents’ self-

reported use of a set of 10 sun safety practices (Table 3)

previously identified as the primary meas-ures typically

available to outdoor workers [25]. This

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

practices are low within the UK construction sector [13].

This indicates that relatively simple interventions could

result in significant positive health outcomes.

Sun safety interventions targeted at construction workers

and other manual outdoor worker groups (e.g. those laying

water pipes or electricity cables) have suc-cessfully

produced improvements in knowledge, attitudes and self-

reported behaviours [14–18]. However, no sun safety

intervention studies have been conducted in the UK

construction sector and it is not clear whether the existing

results can be generalized to this group. All pub-lished

intervention work has been conducted in Australia and

Israel, countries with more intense and prolonged periods of

sunshine than the UK, and findings therefore may not

transfer into the UK context. Furthermore, due to an

established sun safety culture in Australia [19], pre-

intervention attitudes towards sun protection might dif-fer

significantly from those held in the UK.

The high incidence of skin cancer attributable to solar

UVR among construction workers in the UK cou-pled with

their low levels of sun safety knowledge and associated risk-

reduction practices highlights a need for effective

interventions. The aim of this study there-fore was to

examine the effectiveness of a DVD-based sun safety

educational intervention designed specifi-cally for the UK

construction context. Several factors informed the decision

to focus on a film-based inter-vention. First, these have been

shown to be effective in promoting sunscreen knowledge

and usage and rated by study participants more positively

than alternative intervention media such as leaflets [20,21].

Second, film-based interventions can be created at relatively

little cost and delivered quickly in the workplace with little

disruption to work activities. Third, they can be administered

without expert knowledge on the part of the administrator.

Methods

The intervention was a 12-min DVD titled Sun Safety in

Construction: A Workplace Health Guidance Film. It was

developed as a low-cost educational intervention that could

be readily integrated into occupational safety and health

briefings on all types of construction sites. The intervention

is now freely available at http://www.notime-tolose.org.uk

as part of the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health’s

(IOSH) ‘No Time To Lose’ occu-pational cancer-reduction

campaign. The intervention addressed the risk of skin cancer

in the UK construc-tion sector, sun safety practices that

might be adopted on construction sites and self-checking of

skin for early signs of skin cancer.

Construction companies were contacted through the

personal contacts of the research team in addition to

advertisements in trade magazines and presenta-tions to

industry bodies. The baseline questionnaire

was administered in work time during health and safety

briefings in participating organizations (N = 22) between

May and August 2012. Questionnaire completion and return

was incentivized by a prize draw to win a sports car driving

experience. A stamped addressed envelope was provided

with each questionnaire for participants to return completed

questionnaires directly to the research team. The project

champion in each organization was provided with a copy of

the intervention and instructed to administer this only after

administration and comple-tion of the baseline

questionnaire; in most cases, these activities took place on

the same day or within a few days of one another.

Respondents who provided their contact details on the

baseline questionnaire were sent a follow-up questionnaire

along with a stamped addressed return envelope in the

summer of 2013. The mean lag between completion of

baseline and follow-up questionnaires was 12 months.

The study included an emergent comparison group,

comprising workers who completed the baseline ques-

tionnaire and follow-up questionnaire but who did not

receive the intervention [22]. Group membership was

established via an item on the follow-up question-naire that

assessed intervention exposure. Reasons for not having

received the intervention are unlikely to be related to self-

selection. Instead these included work scheduling

requirements, absence or working off-site at the time of

intervention administration, or staff turnover in the period

between baseline question-naire administration and

intervention administration. The emergent design was

adopted for three reasons. First, all participating companies

wanted to deliver the intervention as quickly as possible

ruling out the pos-sibility of populating a sizeable and

representative wait-list comparison group. Second, it was

thought unlikely that all employees who completed both the

baseline and follow-up questionnaires would be present on

the day of intervention administration for operational rea-

sons and due to the transitory nature of the workforce. These

reasons for participants being members of the comparison

group were unlikely to be related to inter-vention

effectiveness. Third, evidence from previous sun safety

intervention studies suggests that it is typi-cal that some

participating organizations fail to cor-rectly administer the

intervention [23]. Therefore, the design reduced the risk of a

type III error (erroneously concluding that an intervention

was unsuccessful when many participants had not received

the intervention as intended).

Respondents’ sun safety knowledge was assessed using

five items (Table 2) adapted from Patel et al. [24].

Respondents indicated whether they agreed or disa-greed

with each statement. We also examined respond-ents’ self-

reported use of a set of 10 sun safety practices (Table 3)

previously identified as the primary meas-ures typically

available to outdoor workers [25]. This

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

22 OCCUPATIONAL MEDICINE

behaviour was assessed in accordance with Prchaska and

DiClemente’s transtheoretical model of behaviour change

[26]. In this model, individuals pass through five stages of

change in relation to a particular behav-iour. Respondents

indicated which of five statements best described their usual

behaviour for each facet of sun safety. The five response

options were ‘I do not do this and I am not thinking about

starting’ (pre-contem-plation stage) (1), ‘I do not do this but

I am thinking about starting’ (contemplation stage) (2), ‘I do

not do this but am planning to start in the next month’ (pre-

paration stage) (3), ‘I do this but have only begun to do so

this year’ (action stage) (4), ‘I do this and have done so for

more than a year’ (maintenance stage) (5). The

questionnaire was also used to collect data on socio-

demographic and occupational factors (Table 1).

Pearson’s chi-square test was used to examine the

statistical significance of the link between self-reported

intervention exposure and changes in knowledge cor-

rectness. For each knowledge domain, we compared the

proportion of participants (intervention versus comparison)

that were incorrect at baseline and then correct at follow-up.

For each behavioural domain, the significance of change in

the mean score on the stage of change measure was

examined using a repeated meas-ures t-test in both the

intervention and comparison groups. The proportion of

respondents in the action or maintenance stage of change in

each group at follow-up was also examined to identify the

number of partici-pants crossing the thresholds from

inaction to action/ maintenance. This approach to reporting

is consistent with that employed in previous sun safety

intervention studies [16,17,27].

A research ethics committee at the University of

Nottingham granted ethical approval for the study and the

research adhered to the British Psychological Society’s

Code of Ethics and Conduct [28].

Results

A total of 1279 workers returned a completed baseline

questionnaire, with 906 respondents (71%) providing contact

details. A total of 160 respondents returned a completed

baseline and follow-up questionnaire, gen-erating an 18%

retention rate (Table 1). No evidence of response bias was

evident in terms of significant dif-ferences between follow-

up questionnaire responders and non-responders for gender,

age, skin type and skin cancer experience. For location,

completed follow-up questionnaires were returned from

across Britain; none were returned from Northern Ireland.

For occupational characteristics, similar proportions of

responders and non-responders indicated that they had

received sun safety training at some point in the past.

However, non-responders worked outdoors for significantly

more hours on a typical day M = 6.6; SD = 3.3 versus M =

4.4;

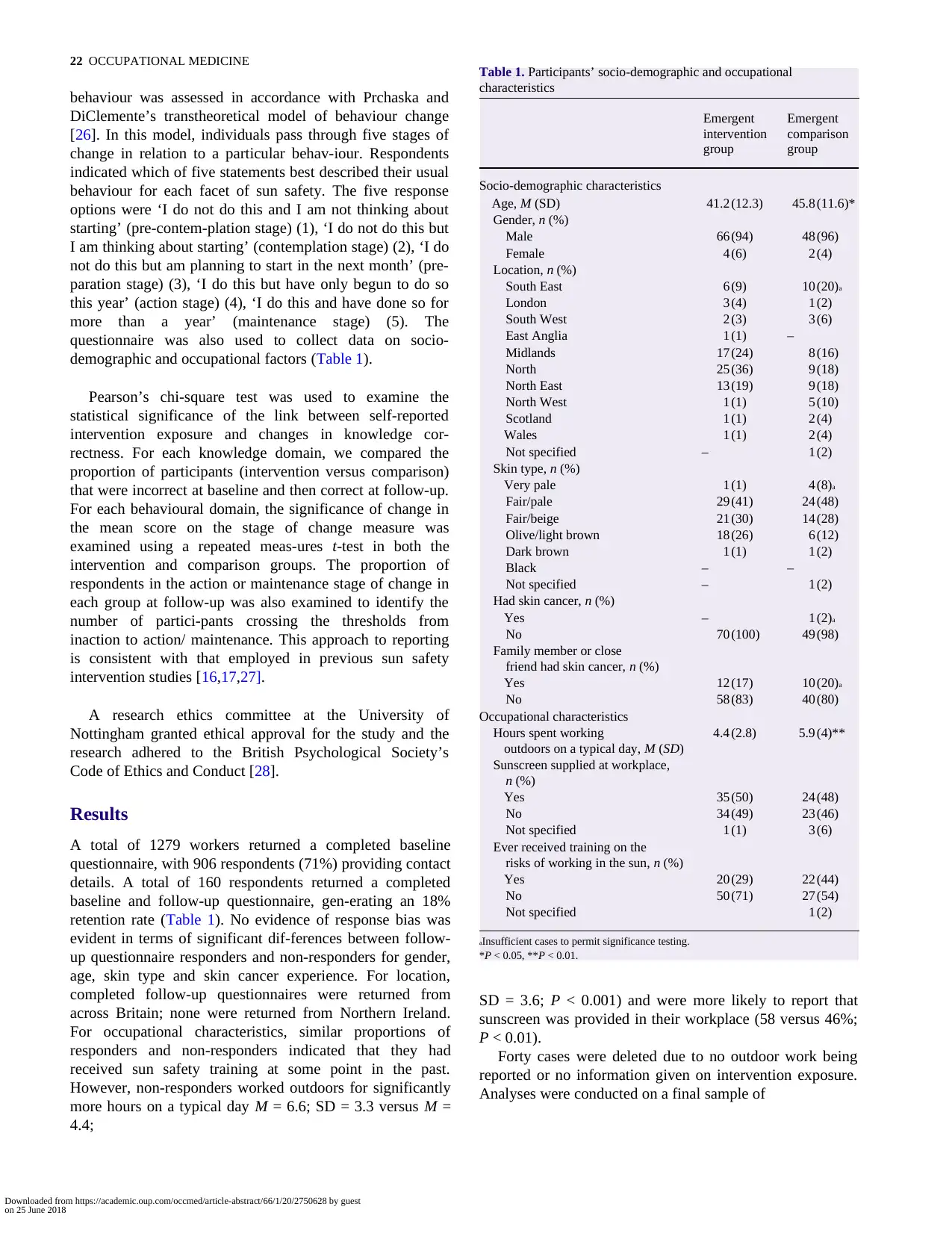

Table 1. Participants’ socio-demographic and occupational

characteristics

Emergent Emergent

intervention comparison

group group

Socio-demographic characteristics

Age, M (SD) 41.2 (12.3) 45.8 (11.6)*

Gender, n (%)

Male 66 (94) 48 (96)

Female 4 (6) 2 (4)

Location, n (%)

South East 6 (9) 10 (20)a

London 3 (4) 1 (2)

South West 2 (3) 3 (6)

East Anglia 1 (1) –

Midlands 17 (24) 8 (16)

North 25 (36) 9 (18)

North East 13 (19) 9 (18)

North West 1 (1) 5 (10)

Scotland 1 (1) 2 (4)

Wales 1 (1) 2 (4)

Not specified – 1 (2)

Skin type, n (%)

Very pale 1 (1) 4 (8)a

Fair/pale 29 (41) 24 (48)

Fair/beige 21 (30) 14 (28)

Olive/light brown 18 (26) 6 (12)

Dark brown 1 (1) 1 (2)

Black – –

Not specified – 1 (2)

Had skin cancer, n (%)

Yes – 1 (2)a

No 70 (100) 49 (98)

Family member or close

friend had skin cancer, n (%)

Yes 12 (17) 10 (20)a

No 58 (83) 40 (80)

Occupational characteristics

Hours spent working 4.4 (2.8) 5.9 (4)**

outdoors on a typical day, M (SD)

Sunscreen supplied at workplace,

n (%)

Yes 35 (50) 24 (48)

No 34 (49) 23 (46)

Not specified 1 (1) 3 (6)

Ever received training on the

risks of working in the sun, n (%)

Yes 20 (29) 22 (44)

No 50 (71) 27 (54)

Not specified 1 (2)

aInsufficient cases to permit significance testing.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

SD = 3.6; P < 0.001) and were more likely to report that

sunscreen was provided in their workplace (58 versus 46%;

P < 0.01).

Forty cases were deleted due to no outdoor work being

reported or no information given on intervention exposure.

Analyses were conducted on a final sample of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

behaviour was assessed in accordance with Prchaska and

DiClemente’s transtheoretical model of behaviour change

[26]. In this model, individuals pass through five stages of

change in relation to a particular behav-iour. Respondents

indicated which of five statements best described their usual

behaviour for each facet of sun safety. The five response

options were ‘I do not do this and I am not thinking about

starting’ (pre-contem-plation stage) (1), ‘I do not do this but

I am thinking about starting’ (contemplation stage) (2), ‘I do

not do this but am planning to start in the next month’ (pre-

paration stage) (3), ‘I do this but have only begun to do so

this year’ (action stage) (4), ‘I do this and have done so for

more than a year’ (maintenance stage) (5). The

questionnaire was also used to collect data on socio-

demographic and occupational factors (Table 1).

Pearson’s chi-square test was used to examine the

statistical significance of the link between self-reported

intervention exposure and changes in knowledge cor-

rectness. For each knowledge domain, we compared the

proportion of participants (intervention versus comparison)

that were incorrect at baseline and then correct at follow-up.

For each behavioural domain, the significance of change in

the mean score on the stage of change measure was

examined using a repeated meas-ures t-test in both the

intervention and comparison groups. The proportion of

respondents in the action or maintenance stage of change in

each group at follow-up was also examined to identify the

number of partici-pants crossing the thresholds from

inaction to action/ maintenance. This approach to reporting

is consistent with that employed in previous sun safety

intervention studies [16,17,27].

A research ethics committee at the University of

Nottingham granted ethical approval for the study and the

research adhered to the British Psychological Society’s

Code of Ethics and Conduct [28].

Results

A total of 1279 workers returned a completed baseline

questionnaire, with 906 respondents (71%) providing contact

details. A total of 160 respondents returned a completed

baseline and follow-up questionnaire, gen-erating an 18%

retention rate (Table 1). No evidence of response bias was

evident in terms of significant dif-ferences between follow-

up questionnaire responders and non-responders for gender,

age, skin type and skin cancer experience. For location,

completed follow-up questionnaires were returned from

across Britain; none were returned from Northern Ireland.

For occupational characteristics, similar proportions of

responders and non-responders indicated that they had

received sun safety training at some point in the past.

However, non-responders worked outdoors for significantly

more hours on a typical day M = 6.6; SD = 3.3 versus M =

4.4;

Table 1. Participants’ socio-demographic and occupational

characteristics

Emergent Emergent

intervention comparison

group group

Socio-demographic characteristics

Age, M (SD) 41.2 (12.3) 45.8 (11.6)*

Gender, n (%)

Male 66 (94) 48 (96)

Female 4 (6) 2 (4)

Location, n (%)

South East 6 (9) 10 (20)a

London 3 (4) 1 (2)

South West 2 (3) 3 (6)

East Anglia 1 (1) –

Midlands 17 (24) 8 (16)

North 25 (36) 9 (18)

North East 13 (19) 9 (18)

North West 1 (1) 5 (10)

Scotland 1 (1) 2 (4)

Wales 1 (1) 2 (4)

Not specified – 1 (2)

Skin type, n (%)

Very pale 1 (1) 4 (8)a

Fair/pale 29 (41) 24 (48)

Fair/beige 21 (30) 14 (28)

Olive/light brown 18 (26) 6 (12)

Dark brown 1 (1) 1 (2)

Black – –

Not specified – 1 (2)

Had skin cancer, n (%)

Yes – 1 (2)a

No 70 (100) 49 (98)

Family member or close

friend had skin cancer, n (%)

Yes 12 (17) 10 (20)a

No 58 (83) 40 (80)

Occupational characteristics

Hours spent working 4.4 (2.8) 5.9 (4)**

outdoors on a typical day, M (SD)

Sunscreen supplied at workplace,

n (%)

Yes 35 (50) 24 (48)

No 34 (49) 23 (46)

Not specified 1 (1) 3 (6)

Ever received training on the

risks of working in the sun, n (%)

Yes 20 (29) 22 (44)

No 50 (71) 27 (54)

Not specified 1 (2)

aInsufficient cases to permit significance testing.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

SD = 3.6; P < 0.001) and were more likely to report that

sunscreen was provided in their workplace (58 versus 46%;

P < 0.01).

Forty cases were deleted due to no outdoor work being

reported or no information given on intervention exposure.

Analyses were conducted on a final sample of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

J. HOUDMONT ET AL.: SUN SAFETY IN THE UK CONSTRUCTION SECTOR 23

120 cases (emergent intervention group n = 70; emer-gent

comparison group n = 50). There were no signifi-cant pre-

intervention differences between the knowledge and

practices reported by the two groups.

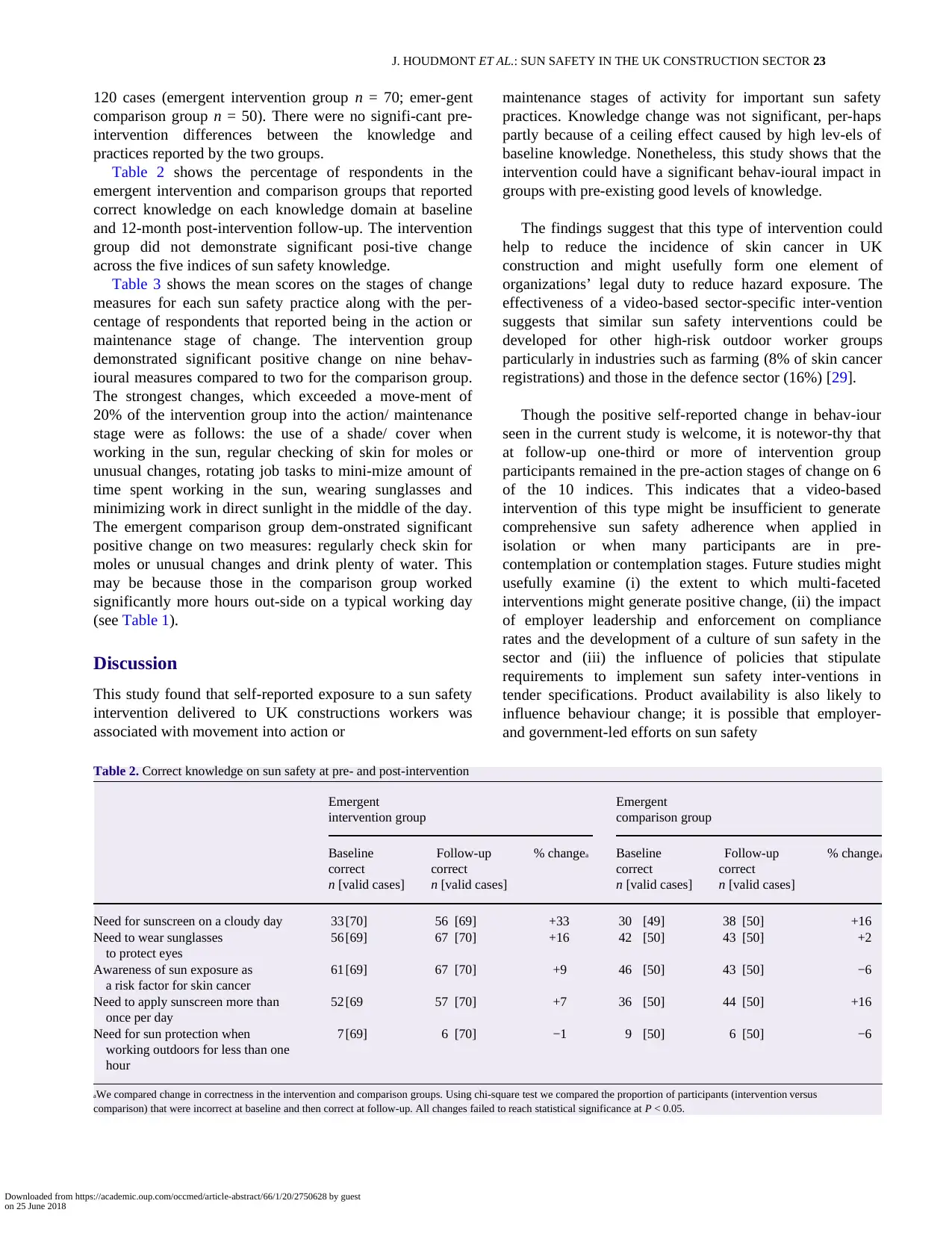

Table 2 shows the percentage of respondents in the

emergent intervention and comparison groups that reported

correct knowledge on each knowledge domain at baseline

and 12-month post-intervention follow-up. The intervention

group did not demonstrate significant posi-tive change

across the five indices of sun safety knowledge.

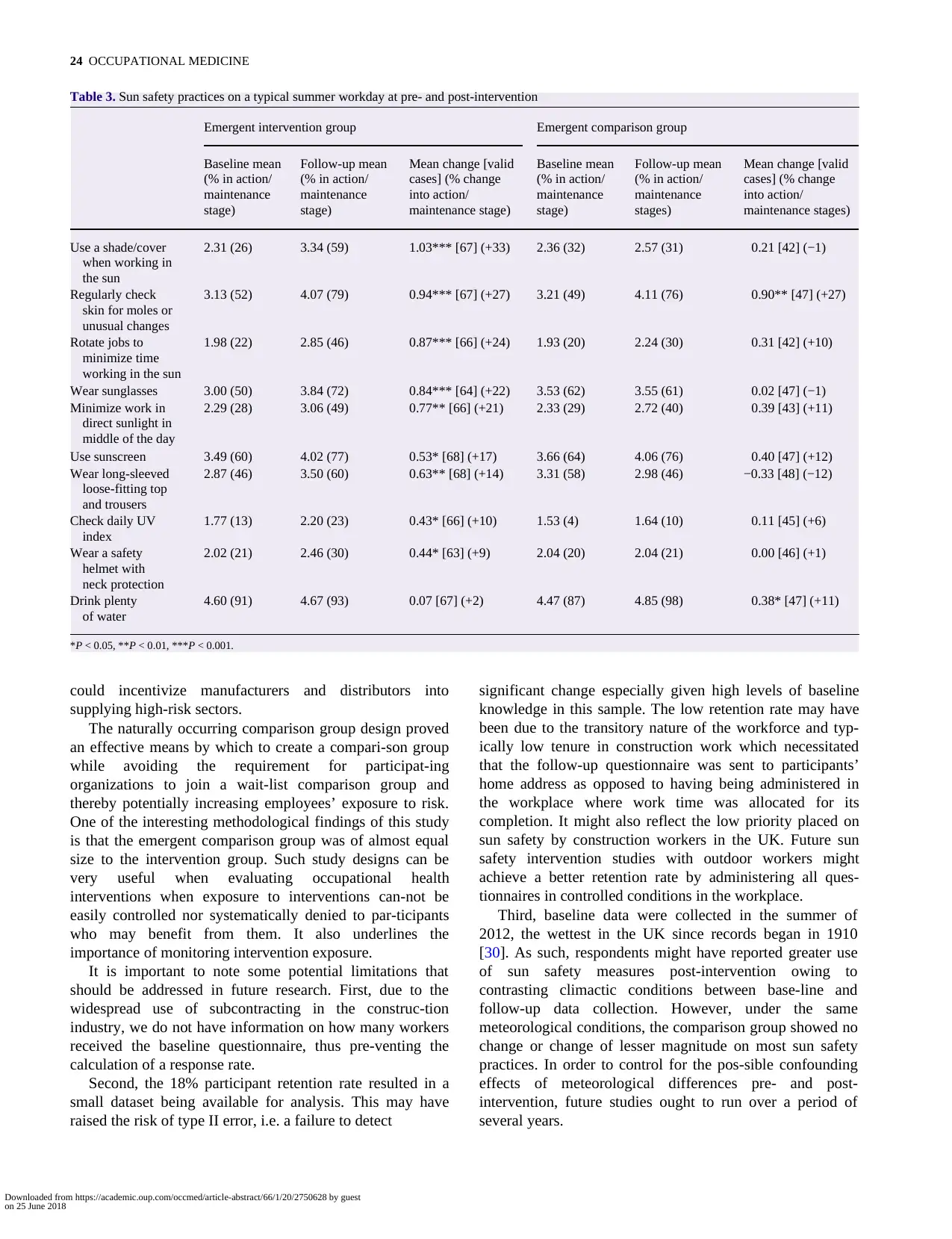

Table 3 shows the mean scores on the stages of change

measures for each sun safety practice along with the per-

centage of respondents that reported being in the action or

maintenance stage of change. The intervention group

demonstrated significant positive change on nine behav-

ioural measures compared to two for the comparison group.

The strongest changes, which exceeded a move-ment of

20% of the intervention group into the action/ maintenance

stage were as follows: the use of a shade/ cover when

working in the sun, regular checking of skin for moles or

unusual changes, rotating job tasks to mini-mize amount of

time spent working in the sun, wearing sunglasses and

minimizing work in direct sunlight in the middle of the day.

The emergent comparison group dem-onstrated significant

positive change on two measures: regularly check skin for

moles or unusual changes and drink plenty of water. This

may be because those in the comparison group worked

significantly more hours out-side on a typical working day

(see Table 1).

Discussion

This study found that self-reported exposure to a sun safety

intervention delivered to UK constructions workers was

associated with movement into action or

maintenance stages of activity for important sun safety

practices. Knowledge change was not significant, per-haps

partly because of a ceiling effect caused by high lev-els of

baseline knowledge. Nonetheless, this study shows that the

intervention could have a significant behav-ioural impact in

groups with pre-existing good levels of knowledge.

The findings suggest that this type of intervention could

help to reduce the incidence of skin cancer in UK

construction and might usefully form one element of

organizations’ legal duty to reduce hazard exposure. The

effectiveness of a video-based sector-specific inter-vention

suggests that similar sun safety interventions could be

developed for other high-risk outdoor worker groups

particularly in industries such as farming (8% of skin cancer

registrations) and those in the defence sector (16%) [29].

Though the positive self-reported change in behav-iour

seen in the current study is welcome, it is notewor-thy that

at follow-up one-third or more of intervention group

participants remained in the pre-action stages of change on 6

of the 10 indices. This indicates that a video-based

intervention of this type might be insufficient to generate

comprehensive sun safety adherence when applied in

isolation or when many participants are in pre-

contemplation or contemplation stages. Future studies might

usefully examine (i) the extent to which multi-faceted

interventions might generate positive change, (ii) the impact

of employer leadership and enforcement on compliance

rates and the development of a culture of sun safety in the

sector and (iii) the influence of policies that stipulate

requirements to implement sun safety inter-ventions in

tender specifications. Product availability is also likely to

influence behaviour change; it is possible that employer-

and government-led efforts on sun safety

Table 2. Correct knowledge on sun safety at pre- and post-intervention

Emergent Emergent

intervention group comparison group

Baseline Follow-up % changea Baseline Follow-up % changea

correct correct correct correct

n [valid cases] n [valid cases] n [valid cases] n [valid cases]

Need for sunscreen on a cloudy day 33 [70] 56 [69] +33 30 [49] 38 [50] +16

Need to wear sunglasses 56 [69] 67 [70] +16 42 [50] 43 [50] +2

to protect eyes

Awareness of sun exposure as 61 [69] 67 [70] +9 46 [50] 43 [50] −6

a risk factor for skin cancer

Need to apply sunscreen more than 52 [69 57 [70] +7 36 [50] 44 [50] +16

once per day

Need for sun protection when 7 [69] 6 [70] −1 9 [50] 6 [50] −6

working outdoors for less than one

hour

aWe compared change in correctness in the intervention and comparison groups. Using chi-square test we compared the proportion of participants (intervention versus

comparison) that were incorrect at baseline and then correct at follow-up. All changes failed to reach statistical significance at P < 0.05.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

120 cases (emergent intervention group n = 70; emer-gent

comparison group n = 50). There were no signifi-cant pre-

intervention differences between the knowledge and

practices reported by the two groups.

Table 2 shows the percentage of respondents in the

emergent intervention and comparison groups that reported

correct knowledge on each knowledge domain at baseline

and 12-month post-intervention follow-up. The intervention

group did not demonstrate significant posi-tive change

across the five indices of sun safety knowledge.

Table 3 shows the mean scores on the stages of change

measures for each sun safety practice along with the per-

centage of respondents that reported being in the action or

maintenance stage of change. The intervention group

demonstrated significant positive change on nine behav-

ioural measures compared to two for the comparison group.

The strongest changes, which exceeded a move-ment of

20% of the intervention group into the action/ maintenance

stage were as follows: the use of a shade/ cover when

working in the sun, regular checking of skin for moles or

unusual changes, rotating job tasks to mini-mize amount of

time spent working in the sun, wearing sunglasses and

minimizing work in direct sunlight in the middle of the day.

The emergent comparison group dem-onstrated significant

positive change on two measures: regularly check skin for

moles or unusual changes and drink plenty of water. This

may be because those in the comparison group worked

significantly more hours out-side on a typical working day

(see Table 1).

Discussion

This study found that self-reported exposure to a sun safety

intervention delivered to UK constructions workers was

associated with movement into action or

maintenance stages of activity for important sun safety

practices. Knowledge change was not significant, per-haps

partly because of a ceiling effect caused by high lev-els of

baseline knowledge. Nonetheless, this study shows that the

intervention could have a significant behav-ioural impact in

groups with pre-existing good levels of knowledge.

The findings suggest that this type of intervention could

help to reduce the incidence of skin cancer in UK

construction and might usefully form one element of

organizations’ legal duty to reduce hazard exposure. The

effectiveness of a video-based sector-specific inter-vention

suggests that similar sun safety interventions could be

developed for other high-risk outdoor worker groups

particularly in industries such as farming (8% of skin cancer

registrations) and those in the defence sector (16%) [29].

Though the positive self-reported change in behav-iour

seen in the current study is welcome, it is notewor-thy that

at follow-up one-third or more of intervention group

participants remained in the pre-action stages of change on 6

of the 10 indices. This indicates that a video-based

intervention of this type might be insufficient to generate

comprehensive sun safety adherence when applied in

isolation or when many participants are in pre-

contemplation or contemplation stages. Future studies might

usefully examine (i) the extent to which multi-faceted

interventions might generate positive change, (ii) the impact

of employer leadership and enforcement on compliance

rates and the development of a culture of sun safety in the

sector and (iii) the influence of policies that stipulate

requirements to implement sun safety inter-ventions in

tender specifications. Product availability is also likely to

influence behaviour change; it is possible that employer-

and government-led efforts on sun safety

Table 2. Correct knowledge on sun safety at pre- and post-intervention

Emergent Emergent

intervention group comparison group

Baseline Follow-up % changea Baseline Follow-up % changea

correct correct correct correct

n [valid cases] n [valid cases] n [valid cases] n [valid cases]

Need for sunscreen on a cloudy day 33 [70] 56 [69] +33 30 [49] 38 [50] +16

Need to wear sunglasses 56 [69] 67 [70] +16 42 [50] 43 [50] +2

to protect eyes

Awareness of sun exposure as 61 [69] 67 [70] +9 46 [50] 43 [50] −6

a risk factor for skin cancer

Need to apply sunscreen more than 52 [69 57 [70] +7 36 [50] 44 [50] +16

once per day

Need for sun protection when 7 [69] 6 [70] −1 9 [50] 6 [50] −6

working outdoors for less than one

hour

aWe compared change in correctness in the intervention and comparison groups. Using chi-square test we compared the proportion of participants (intervention versus

comparison) that were incorrect at baseline and then correct at follow-up. All changes failed to reach statistical significance at P < 0.05.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

24 OCCUPATIONAL MEDICINE

Table 3. Sun safety practices on a typical summer workday at pre- and post-intervention

Emergent intervention group Emergent comparison group

Baseline mean Follow-up mean Mean change [valid Baseline mean Follow-up mean Mean change [valid

(% in action/ (% in action/ cases] (% change (% in action/ (% in action/ cases] (% change

maintenance maintenance into action/ maintenance maintenance into action/

stage) stage) maintenance stage) stage) stages) maintenance stages)

Use a shade/cover 2.31 (26) 3.34 (59) 1.03*** [67] (+33) 2.36 (32) 2.57 (31) 0.21 [42] (−1)

when working in

the sun

Regularly check 3.13 (52) 4.07 (79) 0.94*** [67] (+27) 3.21 (49) 4.11 (76) 0.90** [47] (+27)

skin for moles or

unusual changes

Rotate jobs to 1.98 (22) 2.85 (46) 0.87*** [66] (+24) 1.93 (20) 2.24 (30) 0.31 [42] (+10)

minimize time

working in the sun

Wear sunglasses 3.00 (50) 3.84 (72) 0.84*** [64] (+22) 3.53 (62) 3.55 (61) 0.02 [47] (−1)

Minimize work in 2.29 (28) 3.06 (49) 0.77** [66] (+21) 2.33 (29) 2.72 (40) 0.39 [43] (+11)

direct sunlight in

middle of the day

Use sunscreen 3.49 (60) 4.02 (77) 0.53* [68] (+17) 3.66 (64) 4.06 (76) 0.40 [47] (+12)

Wear long-sleeved 2.87 (46) 3.50 (60) 0.63** [68] (+14) 3.31 (58) 2.98 (46) −0.33 [48] (−12)

loose-fitting top

and trousers

Check daily UV 1.77 (13) 2.20 (23) 0.43* [66] (+10) 1.53 (4) 1.64 (10) 0.11 [45] (+6)

index

Wear a safety 2.02 (21) 2.46 (30) 0.44* [63] (+9) 2.04 (20) 2.04 (21) 0.00 [46] (+1)

helmet with

neck protection

Drink plenty 4.60 (91) 4.67 (93) 0.07 [67] (+2) 4.47 (87) 4.85 (98) 0.38* [47] (+11)

of water

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

could incentivize manufacturers and distributors into

supplying high-risk sectors.

The naturally occurring comparison group design proved

an effective means by which to create a compari-son group

while avoiding the requirement for participat-ing

organizations to join a wait-list comparison group and

thereby potentially increasing employees’ exposure to risk.

One of the interesting methodological findings of this study

is that the emergent comparison group was of almost equal

size to the intervention group. Such study designs can be

very useful when evaluating occupational health

interventions when exposure to interventions can-not be

easily controlled nor systematically denied to par-ticipants

who may benefit from them. It also underlines the

importance of monitoring intervention exposure.

It is important to note some potential limitations that

should be addressed in future research. First, due to the

widespread use of subcontracting in the construc-tion

industry, we do not have information on how many workers

received the baseline questionnaire, thus pre-venting the

calculation of a response rate.

Second, the 18% participant retention rate resulted in a

small dataset being available for analysis. This may have

raised the risk of type II error, i.e. a failure to detect

significant change especially given high levels of baseline

knowledge in this sample. The low retention rate may have

been due to the transitory nature of the workforce and typ-

ically low tenure in construction work which necessitated

that the follow-up questionnaire was sent to participants’

home address as opposed to having being administered in

the workplace where work time was allocated for its

completion. It might also reflect the low priority placed on

sun safety by construction workers in the UK. Future sun

safety intervention studies with outdoor workers might

achieve a better retention rate by administering all ques-

tionnaires in controlled conditions in the workplace.

Third, baseline data were collected in the summer of

2012, the wettest in the UK since records began in 1910

[30]. As such, respondents might have reported greater use

of sun safety measures post-intervention owing to

contrasting climactic conditions between base-line and

follow-up data collection. However, under the same

meteorological conditions, the comparison group showed no

change or change of lesser magnitude on most sun safety

practices. In order to control for the pos-sible confounding

effects of meteorological differences pre- and post-

intervention, future studies ought to run over a period of

several years.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article-abstract/66/1/20/2750628 by guest

on 25 June 2018

Table 3. Sun safety practices on a typical summer workday at pre- and post-intervention

Emergent intervention group Emergent comparison group

Baseline mean Follow-up mean Mean change [valid Baseline mean Follow-up mean Mean change [valid

(% in action/ (% in action/ cases] (% change (% in action/ (% in action/ cases] (% change

maintenance maintenance into action/ maintenance maintenance into action/

stage) stage) maintenance stage) stage) stages) maintenance stages)