Annals of Internal Medicine: Nurse-Patient Ratios and Patient Safety

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/20

|7

|7222

|89

Report

AI Summary

This report summarizes a systematic review published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, focusing on the relationship between nurse-patient ratios and patient safety. The review examined existing literature, including cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, to assess the impact of nurse staffing levels on hospital mortality and other patient outcomes. The findings indicate a consistent relationship between higher RN staffing and lower hospital-related mortality, supported by both a meta-analysis and a narrative review. The strongest evidence comes from a longitudinal study that carefully accounted for nurse staffing and patient comorbid conditions. The review also highlights limitations, such as the lack of evaluations of intentional interventions to increase nurse staffing ratios. The report discusses various factors influencing patient outcomes, including nurse burnout, job satisfaction, and the overall nursing environment. The review suggests that improved surveillance, facilitated by adequate staffing, is a critical factor in reducing inpatient mortality. The review also mentions the need for further research to establish a causal relationship and explore the underlying mechanisms.

Nurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

A Systematic Review

Paul G. Shekelle, MD, PhD

A smallpercentage of patients die during hospitalization or shortly

thereafter, and it is widely believed that more or better nursing care

could preventsome of these deaths.The authorsystematically

reviewed the evidence aboutnurse staffing ratios and in-hospital

death through September 2012.From 550 titles,87 articles were

reviewed and 15 new studies thataugmented the 2 existing re-

views were selected.The strongestevidence supporting a causal

relationship between highernurse staffing levelsand decreased

inpatientmortality comesfrom a longitudinalstudy in a single

hospitalthat carefully accounted fornurse staffing and patient

comorbid conditionsand a meta-analysisthat found a “dose–

response relationship” in observationalstudies of nurse staffing and

death.No studies reported any serious harms associated with an

increase in nurse staffing.Limiting any stronger conclusions is the

lack of an evaluation of an intervention to increase nurse staffing

ratios. The formalcosts of increasing the nurse–patient ratio cannot

be calculated because there has been no evaluation ofan inten-

tionalchange in nurse staffing to improve patient outcomes.

Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:404-409. www.annals.org

For author affiliation,see end of text.

THE PROBLEM

A smallpercentage of hospitalized patients die during

or shortlyafterhospitalization.Evidencesuggeststhat

some proportion ofthese deathscould probably be pre-

vented with more nursing care.For example,in 1 early

study of 232 342 surgical discharges from several Pennsyl-

vania hospitals, 4535 patients (2%) died within 30 days of

hospitalization;the investigators estimated that the differ-

ence between 4:1 and 8:1 patient–nurse ratios may be ap-

proximately 1000 deaths in a group of this size (1). Other

studieshave produced roughly similarestimates,namely

approximately 1 to 5 fewer deaths per 1000 inpatient days

with more nurse staffing per patient (2– 4).The rationale

for suggesting that increasing the ratio of registered nurses

(RNs) to patients will lead to decreased illness or mortality

rates rests on the belief that improved attention to patients

is the criticalfactor.This systematic review examined the

evidence on the effects of interventions aimed at increasing

nurse–patient ratios on patient illness and death.

PATIENTSAFETYSTRATEGIES

There has been no evaluation of an intentional change

in RN staffing to improve patient outcomes; therefore, the

patientsafety strategy referred to in thisarticle remains

somewhat unclear.Most studies have been cross-sectional

or longitudinalassessments ofdifferences in nursing staff

variables, with the most commonly assessed measure being

the proportion of RN time per some measure of inpatient

load and the most commonly assessed outcome being mor-

tality. However, many other factors have been proposed as

being causal with respect to the relationship between nurs-

ing care and reductions in hospital mortality, potentiall

addition to orinstead ofa simplenurse–patientratio.

These factorsinclude measuresof nursing burnout,job

satisfaction,teamwork,nurse turnover,nursing leadership

in hospitals, and nurse practice environment.

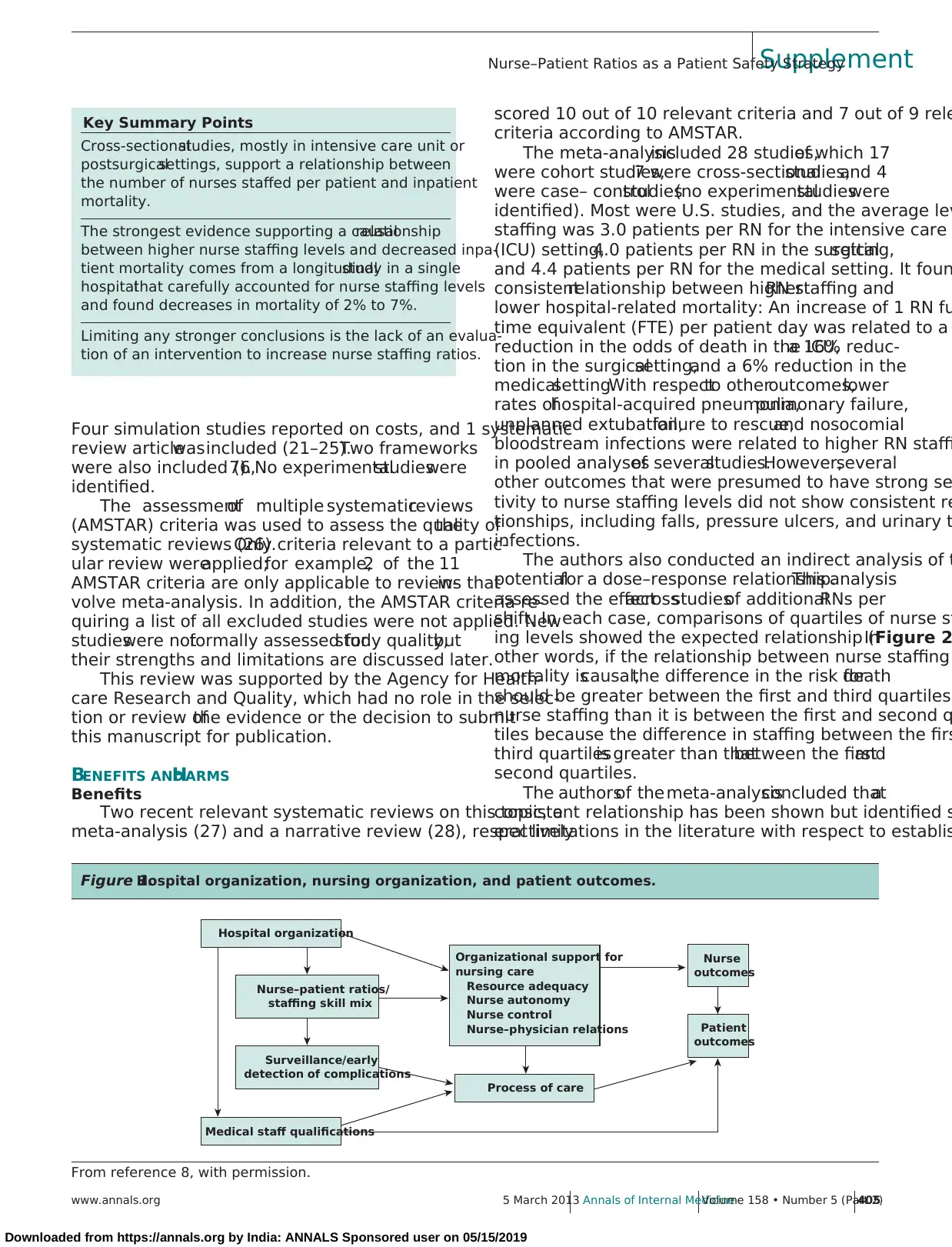

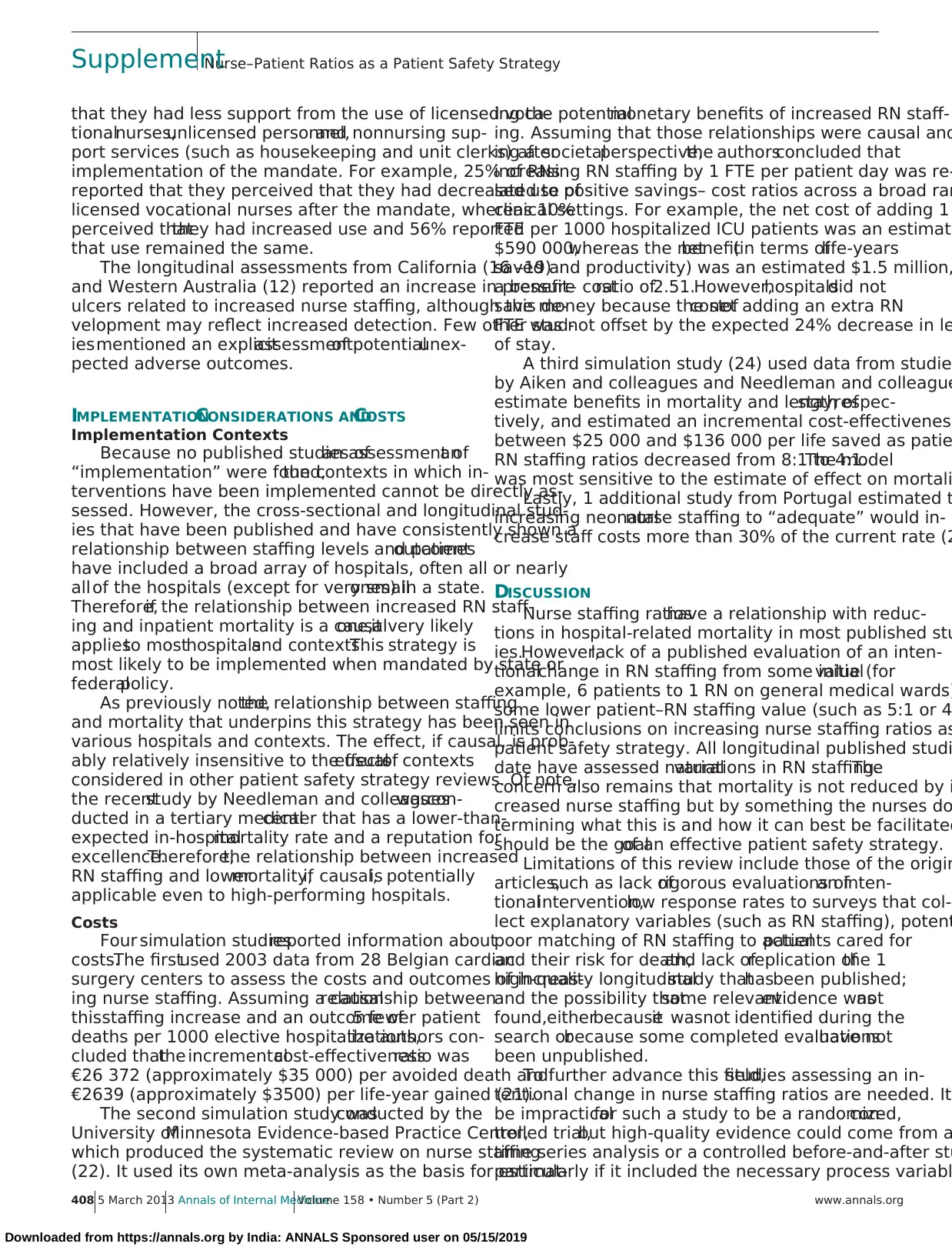

Severalresearch groupshaveproposed conceptual

frameworksto explain why more effective nursing care

may reduce inpatientmortality (5– 8).Underlying allof

these conceptualframeworks is the belief that surveillance

is a criticalfactor that can be improved with more staff,

better-educated staff, or a better working environment

A representative framework by Aiken and colleagues(8)

positsthatnurse–patientratios,along with staffing skill

mix,can lead to bettersurveillance,which,along with

many other factors,can influence the process of care and

lead to better patient outcomes (Figure 1).

REVIEWPROCESSES

Two existing reviews relevant to the topic were iden

tified,by using methods described by Whitlock and col-

leagues (10).These reviews were supplemented by search

ing the Web ofScience for articles published from 2009

(the end date of the search from the most recent revie

September2012 thatcited any of4 key articlesin this

field, including the older of the 2 reviews, and was limi

to studies published in English. For a complete descript

of the search strategies,literature flow diagram,and evi-

dence tables, see the Supplement (available at www.

.org). The update search identified 546 titles, and 4 art

came from reference mining.Titles and abstracts were re-

viewed and selected if they reported empiricaldata on the

relationship between nurse staffing ratios and mortality

nursing-sensitive outcomes, such as pressure ulcers an

ure to rescue.Because severalcross-sectionalstudies have

assessed this relationship,only 1 additionalcross-sectional

study was included for detailed review. The exception

a cross-sectionalstudy that evaluated a quasi-intervention

(11).Nine longitudinalstudieswere identified (12–20).

See also:

Web-Only

CME quiz (ProfessionalResponsibility Credit)

Supplement

Annals of Internal MediciSupplement

404 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2) www.annals.org

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

A Systematic Review

Paul G. Shekelle, MD, PhD

A smallpercentage of patients die during hospitalization or shortly

thereafter, and it is widely believed that more or better nursing care

could preventsome of these deaths.The authorsystematically

reviewed the evidence aboutnurse staffing ratios and in-hospital

death through September 2012.From 550 titles,87 articles were

reviewed and 15 new studies thataugmented the 2 existing re-

views were selected.The strongestevidence supporting a causal

relationship between highernurse staffing levelsand decreased

inpatientmortality comesfrom a longitudinalstudy in a single

hospitalthat carefully accounted fornurse staffing and patient

comorbid conditionsand a meta-analysisthat found a “dose–

response relationship” in observationalstudies of nurse staffing and

death.No studies reported any serious harms associated with an

increase in nurse staffing.Limiting any stronger conclusions is the

lack of an evaluation of an intervention to increase nurse staffing

ratios. The formalcosts of increasing the nurse–patient ratio cannot

be calculated because there has been no evaluation ofan inten-

tionalchange in nurse staffing to improve patient outcomes.

Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:404-409. www.annals.org

For author affiliation,see end of text.

THE PROBLEM

A smallpercentage of hospitalized patients die during

or shortlyafterhospitalization.Evidencesuggeststhat

some proportion ofthese deathscould probably be pre-

vented with more nursing care.For example,in 1 early

study of 232 342 surgical discharges from several Pennsyl-

vania hospitals, 4535 patients (2%) died within 30 days of

hospitalization;the investigators estimated that the differ-

ence between 4:1 and 8:1 patient–nurse ratios may be ap-

proximately 1000 deaths in a group of this size (1). Other

studieshave produced roughly similarestimates,namely

approximately 1 to 5 fewer deaths per 1000 inpatient days

with more nurse staffing per patient (2– 4).The rationale

for suggesting that increasing the ratio of registered nurses

(RNs) to patients will lead to decreased illness or mortality

rates rests on the belief that improved attention to patients

is the criticalfactor.This systematic review examined the

evidence on the effects of interventions aimed at increasing

nurse–patient ratios on patient illness and death.

PATIENTSAFETYSTRATEGIES

There has been no evaluation of an intentional change

in RN staffing to improve patient outcomes; therefore, the

patientsafety strategy referred to in thisarticle remains

somewhat unclear.Most studies have been cross-sectional

or longitudinalassessments ofdifferences in nursing staff

variables, with the most commonly assessed measure being

the proportion of RN time per some measure of inpatient

load and the most commonly assessed outcome being mor-

tality. However, many other factors have been proposed as

being causal with respect to the relationship between nurs-

ing care and reductions in hospital mortality, potentiall

addition to orinstead ofa simplenurse–patientratio.

These factorsinclude measuresof nursing burnout,job

satisfaction,teamwork,nurse turnover,nursing leadership

in hospitals, and nurse practice environment.

Severalresearch groupshaveproposed conceptual

frameworksto explain why more effective nursing care

may reduce inpatientmortality (5– 8).Underlying allof

these conceptualframeworks is the belief that surveillance

is a criticalfactor that can be improved with more staff,

better-educated staff, or a better working environment

A representative framework by Aiken and colleagues(8)

positsthatnurse–patientratios,along with staffing skill

mix,can lead to bettersurveillance,which,along with

many other factors,can influence the process of care and

lead to better patient outcomes (Figure 1).

REVIEWPROCESSES

Two existing reviews relevant to the topic were iden

tified,by using methods described by Whitlock and col-

leagues (10).These reviews were supplemented by search

ing the Web ofScience for articles published from 2009

(the end date of the search from the most recent revie

September2012 thatcited any of4 key articlesin this

field, including the older of the 2 reviews, and was limi

to studies published in English. For a complete descript

of the search strategies,literature flow diagram,and evi-

dence tables, see the Supplement (available at www.

.org). The update search identified 546 titles, and 4 art

came from reference mining.Titles and abstracts were re-

viewed and selected if they reported empiricaldata on the

relationship between nurse staffing ratios and mortality

nursing-sensitive outcomes, such as pressure ulcers an

ure to rescue.Because severalcross-sectionalstudies have

assessed this relationship,only 1 additionalcross-sectional

study was included for detailed review. The exception

a cross-sectionalstudy that evaluated a quasi-intervention

(11).Nine longitudinalstudieswere identified (12–20).

See also:

Web-Only

CME quiz (ProfessionalResponsibility Credit)

Supplement

Annals of Internal MediciSupplement

404 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2) www.annals.org

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Four simulation studies reported on costs, and 1 systematic

review articlewasincluded (21–25).Two frameworks

were also included (6,7). No experimentalstudieswere

identified.

The assessmentof multiple systematicreviews

(AMSTAR) criteria was used to assess the quality ofthe

systematic reviews (26).Only criteria relevant to a partic-

ular review wereapplied;for example,2 of the 11

AMSTAR criteria are only applicable to reviews thatin-

volve meta-analysis. In addition, the AMSTAR criteria re-

quiring a list of all excluded studies were not applied. New

studieswere notformally assessed forstudy quality,but

their strengths and limitations are discussed later.

This review was supported by the Agency for Health-

care Research and Quality, which had no role in the selec-

tion or review ofthe evidence or the decision to submit

this manuscript for publication.

BENEFITS ANDHARMS

Benefits

Two recent relevant systematic reviews on this topic, a

meta-analysis (27) and a narrative review (28), respectively

scored 10 out of 10 relevant criteria and 7 out of 9 rele

criteria according to AMSTAR.

The meta-analysisincluded 28 studies,of which 17

were cohort studies,7 were cross-sectionalstudies,and 4

were case– controlstudies(no experimentalstudieswere

identified). Most were U.S. studies, and the average lev

staffing was 3.0 patients per RN for the intensive care

(ICU) setting,4.0 patients per RN in the surgicalsetting,

and 4.4 patients per RN for the medical setting. It foun

consistentrelationship between higherRN staffing and

lower hospital-related mortality: An increase of 1 RN fu

time equivalent (FTE) per patient day was related to a

reduction in the odds of death in the ICU,a 16% reduc-

tion in the surgicalsetting,and a 6% reduction in the

medicalsetting.With respectto otheroutcomes,lower

rates ofhospital-acquired pneumonia,pulmonary failure,

unplanned extubation,failure to rescue,and nosocomial

bloodstream infections were related to higher RN staffi

in pooled analysesof severalstudies.However,several

other outcomes that were presumed to have strong se

tivity to nurse staffing levels did not show consistent re

tionships, including falls, pressure ulcers, and urinary t

infections.

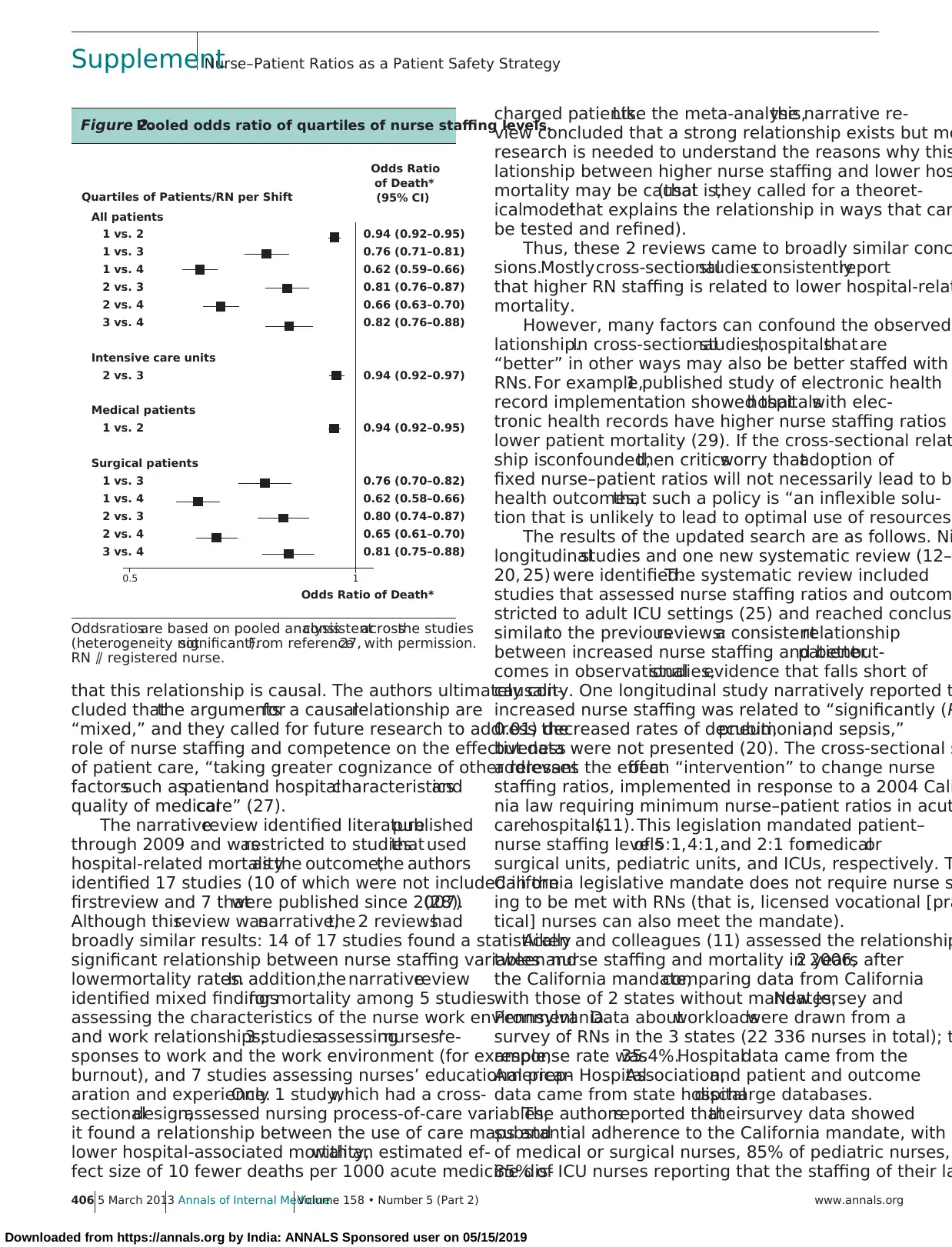

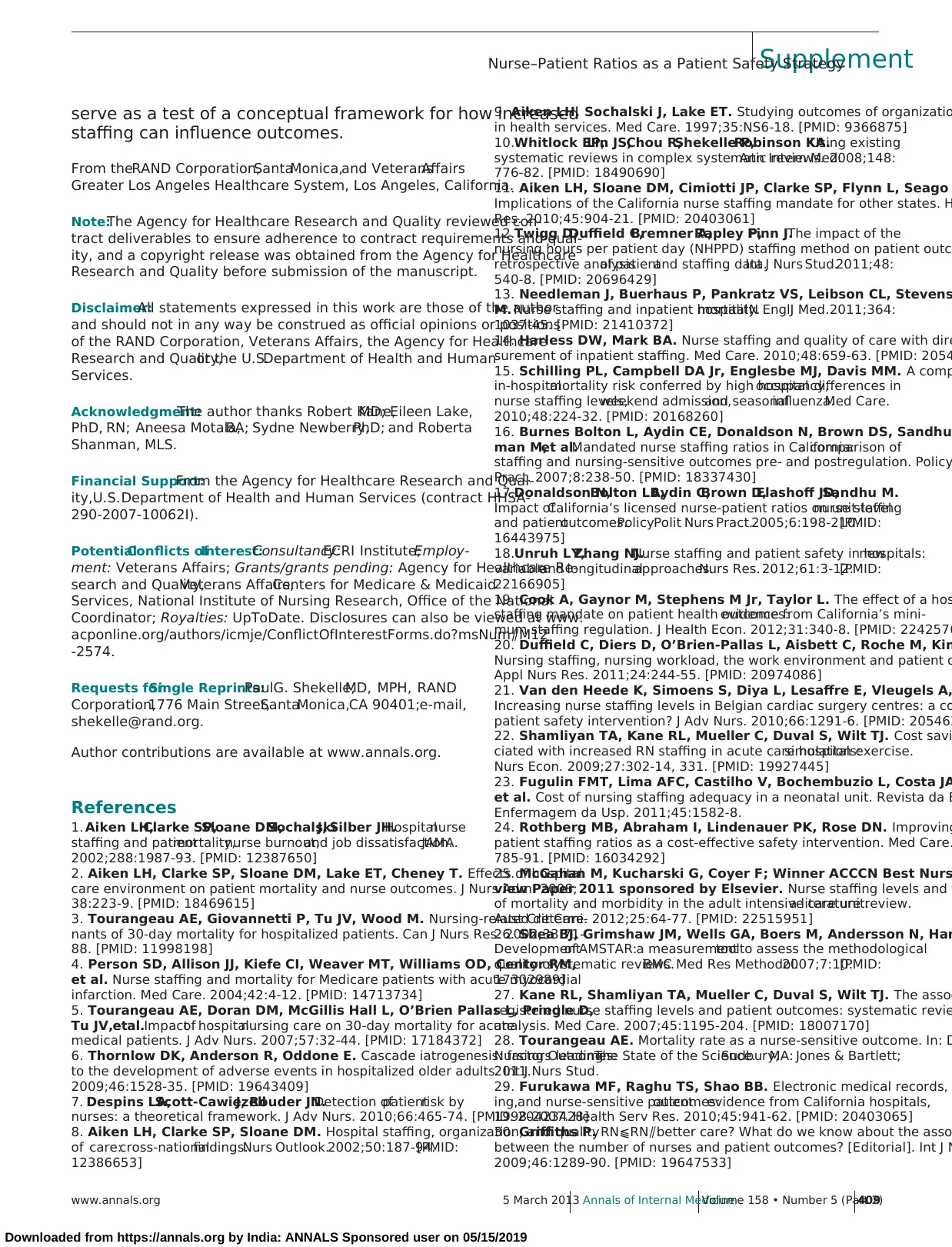

The authors also conducted an indirect analysis of t

potentialfor a dose–response relationship.This analysis

assessed the effectacrossstudiesof additionalRNs per

shift. In each case, comparisons of quartiles of nurse st

ing levels showed the expected relationship (Figure 2In

other words, if the relationship between nurse staffing

mortality iscausal,the difference in the risk fordeath

should be greater between the first and third quartiles

nurse staffing than it is between the first and second q

tiles because the difference in staffing between the firs

third quartilesis greater than thatbetween the firstand

second quartiles.

The authorsof the meta-analysisconcluded thata

consistent relationship has been shown but identified s

eral limitations in the literature with respect to establis

Key Summary Points

Cross-sectionalstudies, mostly in intensive care unit or

postsurgicalsettings, support a relationship between

the number of nurses staffed per patient and inpatient

mortality.

The strongest evidence supporting a causalrelationship

between higher nurse staffing levels and decreased inpa-

tient mortality comes from a longitudinalstudy in a single

hospitalthat carefully accounted for nurse staffing levels

and found decreases in mortality of 2% to 7%.

Limiting any stronger conclusions is the lack of an evalua-

tion of an intervention to increase nurse staffing ratios.

Figure 1.Hospital organization, nursing organization, and patient outcomes.

Hospital organization

Process of care

Medical staff qualifications

Nurse

outcomes

Patient

outcomes

Organizational support for

nursing care

Resource adequacy

Nurse autonomy

Nurse control

Nurse–physician relations

Nurse–patient ratios/

staffing skill mix

Surveillance/early

detection of complications

From reference 8, with permission.

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

www.annals.org 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2)405

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

review articlewasincluded (21–25).Two frameworks

were also included (6,7). No experimentalstudieswere

identified.

The assessmentof multiple systematicreviews

(AMSTAR) criteria was used to assess the quality ofthe

systematic reviews (26).Only criteria relevant to a partic-

ular review wereapplied;for example,2 of the 11

AMSTAR criteria are only applicable to reviews thatin-

volve meta-analysis. In addition, the AMSTAR criteria re-

quiring a list of all excluded studies were not applied. New

studieswere notformally assessed forstudy quality,but

their strengths and limitations are discussed later.

This review was supported by the Agency for Health-

care Research and Quality, which had no role in the selec-

tion or review ofthe evidence or the decision to submit

this manuscript for publication.

BENEFITS ANDHARMS

Benefits

Two recent relevant systematic reviews on this topic, a

meta-analysis (27) and a narrative review (28), respectively

scored 10 out of 10 relevant criteria and 7 out of 9 rele

criteria according to AMSTAR.

The meta-analysisincluded 28 studies,of which 17

were cohort studies,7 were cross-sectionalstudies,and 4

were case– controlstudies(no experimentalstudieswere

identified). Most were U.S. studies, and the average lev

staffing was 3.0 patients per RN for the intensive care

(ICU) setting,4.0 patients per RN in the surgicalsetting,

and 4.4 patients per RN for the medical setting. It foun

consistentrelationship between higherRN staffing and

lower hospital-related mortality: An increase of 1 RN fu

time equivalent (FTE) per patient day was related to a

reduction in the odds of death in the ICU,a 16% reduc-

tion in the surgicalsetting,and a 6% reduction in the

medicalsetting.With respectto otheroutcomes,lower

rates ofhospital-acquired pneumonia,pulmonary failure,

unplanned extubation,failure to rescue,and nosocomial

bloodstream infections were related to higher RN staffi

in pooled analysesof severalstudies.However,several

other outcomes that were presumed to have strong se

tivity to nurse staffing levels did not show consistent re

tionships, including falls, pressure ulcers, and urinary t

infections.

The authors also conducted an indirect analysis of t

potentialfor a dose–response relationship.This analysis

assessed the effectacrossstudiesof additionalRNs per

shift. In each case, comparisons of quartiles of nurse st

ing levels showed the expected relationship (Figure 2In

other words, if the relationship between nurse staffing

mortality iscausal,the difference in the risk fordeath

should be greater between the first and third quartiles

nurse staffing than it is between the first and second q

tiles because the difference in staffing between the firs

third quartilesis greater than thatbetween the firstand

second quartiles.

The authorsof the meta-analysisconcluded thata

consistent relationship has been shown but identified s

eral limitations in the literature with respect to establis

Key Summary Points

Cross-sectionalstudies, mostly in intensive care unit or

postsurgicalsettings, support a relationship between

the number of nurses staffed per patient and inpatient

mortality.

The strongest evidence supporting a causalrelationship

between higher nurse staffing levels and decreased inpa-

tient mortality comes from a longitudinalstudy in a single

hospitalthat carefully accounted for nurse staffing levels

and found decreases in mortality of 2% to 7%.

Limiting any stronger conclusions is the lack of an evalua-

tion of an intervention to increase nurse staffing ratios.

Figure 1.Hospital organization, nursing organization, and patient outcomes.

Hospital organization

Process of care

Medical staff qualifications

Nurse

outcomes

Patient

outcomes

Organizational support for

nursing care

Resource adequacy

Nurse autonomy

Nurse control

Nurse–physician relations

Nurse–patient ratios/

staffing skill mix

Surveillance/early

detection of complications

From reference 8, with permission.

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

www.annals.org 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2)405

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

that this relationship is causal. The authors ultimately con-

cluded thatthe argumentsfor a causalrelationship are

“mixed,” and they called for future research to address the

role of nurse staffing and competence on the effectiveness

of patient care, “taking greater cognizance of other relevant

factorssuch aspatientand hospitalcharacteristicsand

quality of medicalcare” (27).

The narrativereview identified literaturepublished

through 2009 and wasrestricted to studiesthat used

hospital-related mortalityas the outcome;the authors

identified 17 studies (10 of which were not included in the

firstreview and 7 thatwere published since 2007)(28).

Although thisreview wasnarrative,the 2 reviewshad

broadly similar results: 14 of 17 studies found a statistically

significant relationship between nurse staffing variables and

lowermortality rates.In addition,the narrativereview

identified mixed findingsfor mortality among 5 studies

assessing the characteristics of the nurse work environment

and work relationships,3 studiesassessingnurses’re-

sponses to work and the work environment (for example,

burnout), and 7 studies assessing nurses’ educational prep-

aration and experience.Only 1 study,which had a cross-

sectionaldesign,assessed nursing process-of-care variables;

it found a relationship between the use of care maps and

lower hospital-associated mortality,with an estimated ef-

fect size of 10 fewer deaths per 1000 acute medicine dis-

charged patients.Like the meta-analysis,the narrative re-

view concluded that a strong relationship exists but mo

research is needed to understand the reasons why this

lationship between higher nurse staffing and lower hos

mortality may be causal(that is,they called for a theoret-

icalmodelthat explains the relationship in ways that can

be tested and refined).

Thus, these 2 reviews came to broadly similar conc

sions.Mostlycross-sectionalstudiesconsistentlyreport

that higher RN staffing is related to lower hospital-relat

mortality.

However, many factors can confound the observed

lationship.In cross-sectionalstudies,hospitalsthat are

“better” in other ways may also be better staffed with

RNs.For example,1 published study of electronic health

record implementation showed thathospitalswith elec-

tronic health records have higher nurse staffing ratios

lower patient mortality (29). If the cross-sectional relat

ship isconfounded,then criticsworry thatadoption of

fixed nurse–patient ratios will not necessarily lead to b

health outcomes,that such a policy is “an inflexible solu-

tion that is unlikely to lead to optimal use of resources”

The results of the updated search are as follows. Ni

longitudinalstudies and one new systematic review (12–

20, 25) were identified.The systematic review included

studies that assessed nurse staffing ratios and outcom

stricted to adult ICU settings (25) and reached conclusi

similarto the previousreviews:a consistentrelationship

between increased nurse staffing and betterpatientout-

comes in observationalstudies,evidence that falls short of

causality. One longitudinal study narratively reported t

increased nurse staffing was related to “significantly (P

0.01) decreased rates of decubiti,pneumonia,and sepsis,”

but data were not presented (20). The cross-sectional s

addresses the effectof an “intervention” to change nurse

staffing ratios, implemented in response to a 2004 Cali

nia law requiring minimum nurse–patient ratios in acut

carehospitals(11).This legislation mandated patient–

nurse staffing levelsof 5:1,4:1,and 2:1 formedicalor

surgical units, pediatric units, and ICUs, respectively. T

California legislative mandate does not require nurse s

ing to be met with RNs (that is, licensed vocational [pra

tical] nurses can also meet the mandate).

Aiken and colleagues (11) assessed the relationship

tween nurse staffing and mortality in 2006,2 years after

the California mandate,comparing data from California

with those of 2 states without mandates,New Jersey and

Pennsylvania.Data aboutworkloadswere drawn from a

survey of RNs in the 3 states (22 336 nurses in total); t

response rate was35.4%.Hospitaldata came from the

American HospitalAssociation,and patient and outcome

data came from state hospitaldischarge databases.

The authorsreported thattheirsurvey data showed

substantial adherence to the California mandate, with 8

of medical or surgical nurses, 85% of pediatric nurses,

85% of ICU nurses reporting that the staffing of their la

Figure 2.Pooled odds ratio of quartiles of nurse staffing levels.

Quartiles of Patients/RN per Shift

All patients

1 vs. 2

1 vs. 3

1 vs. 4

2 vs. 3

2 vs. 4

3 vs. 4

Intensive care units

2 vs. 3

Medical patients

1 vs. 2

Surgical patients

1 vs. 3

1 vs. 4

2 vs. 3

2 vs. 4

3 vs. 4

Odds Ratio

of Death*

(95% CI)

Odds Ratio of Death*

0.94 (0.92–0.95)

0.76 (0.71–0.81)

0.62 (0.59–0.66)

0.81 (0.76–0.87)

0.66 (0.63–0.70)

0.82 (0.76–0.88)

0.94 (0.92–0.97)

0.94 (0.92–0.95)

0.76 (0.70–0.82)

0.62 (0.58–0.66)

0.80 (0.74–0.87)

0.65 (0.61–0.70)

0.81 (0.75–0.88)

0.5 1

Oddsratiosare based on pooled analysisconsistentacrossthe studies

(heterogeneity notsignificant).From reference27, with permission.

RN ⫽ registered nurse.

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

406 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2) www.annals.org

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

cluded thatthe argumentsfor a causalrelationship are

“mixed,” and they called for future research to address the

role of nurse staffing and competence on the effectiveness

of patient care, “taking greater cognizance of other relevant

factorssuch aspatientand hospitalcharacteristicsand

quality of medicalcare” (27).

The narrativereview identified literaturepublished

through 2009 and wasrestricted to studiesthat used

hospital-related mortalityas the outcome;the authors

identified 17 studies (10 of which were not included in the

firstreview and 7 thatwere published since 2007)(28).

Although thisreview wasnarrative,the 2 reviewshad

broadly similar results: 14 of 17 studies found a statistically

significant relationship between nurse staffing variables and

lowermortality rates.In addition,the narrativereview

identified mixed findingsfor mortality among 5 studies

assessing the characteristics of the nurse work environment

and work relationships,3 studiesassessingnurses’re-

sponses to work and the work environment (for example,

burnout), and 7 studies assessing nurses’ educational prep-

aration and experience.Only 1 study,which had a cross-

sectionaldesign,assessed nursing process-of-care variables;

it found a relationship between the use of care maps and

lower hospital-associated mortality,with an estimated ef-

fect size of 10 fewer deaths per 1000 acute medicine dis-

charged patients.Like the meta-analysis,the narrative re-

view concluded that a strong relationship exists but mo

research is needed to understand the reasons why this

lationship between higher nurse staffing and lower hos

mortality may be causal(that is,they called for a theoret-

icalmodelthat explains the relationship in ways that can

be tested and refined).

Thus, these 2 reviews came to broadly similar conc

sions.Mostlycross-sectionalstudiesconsistentlyreport

that higher RN staffing is related to lower hospital-relat

mortality.

However, many factors can confound the observed

lationship.In cross-sectionalstudies,hospitalsthat are

“better” in other ways may also be better staffed with

RNs.For example,1 published study of electronic health

record implementation showed thathospitalswith elec-

tronic health records have higher nurse staffing ratios

lower patient mortality (29). If the cross-sectional relat

ship isconfounded,then criticsworry thatadoption of

fixed nurse–patient ratios will not necessarily lead to b

health outcomes,that such a policy is “an inflexible solu-

tion that is unlikely to lead to optimal use of resources”

The results of the updated search are as follows. Ni

longitudinalstudies and one new systematic review (12–

20, 25) were identified.The systematic review included

studies that assessed nurse staffing ratios and outcom

stricted to adult ICU settings (25) and reached conclusi

similarto the previousreviews:a consistentrelationship

between increased nurse staffing and betterpatientout-

comes in observationalstudies,evidence that falls short of

causality. One longitudinal study narratively reported t

increased nurse staffing was related to “significantly (P

0.01) decreased rates of decubiti,pneumonia,and sepsis,”

but data were not presented (20). The cross-sectional s

addresses the effectof an “intervention” to change nurse

staffing ratios, implemented in response to a 2004 Cali

nia law requiring minimum nurse–patient ratios in acut

carehospitals(11).This legislation mandated patient–

nurse staffing levelsof 5:1,4:1,and 2:1 formedicalor

surgical units, pediatric units, and ICUs, respectively. T

California legislative mandate does not require nurse s

ing to be met with RNs (that is, licensed vocational [pra

tical] nurses can also meet the mandate).

Aiken and colleagues (11) assessed the relationship

tween nurse staffing and mortality in 2006,2 years after

the California mandate,comparing data from California

with those of 2 states without mandates,New Jersey and

Pennsylvania.Data aboutworkloadswere drawn from a

survey of RNs in the 3 states (22 336 nurses in total); t

response rate was35.4%.Hospitaldata came from the

American HospitalAssociation,and patient and outcome

data came from state hospitaldischarge databases.

The authorsreported thattheirsurvey data showed

substantial adherence to the California mandate, with 8

of medical or surgical nurses, 85% of pediatric nurses,

85% of ICU nurses reporting that the staffing of their la

Figure 2.Pooled odds ratio of quartiles of nurse staffing levels.

Quartiles of Patients/RN per Shift

All patients

1 vs. 2

1 vs. 3

1 vs. 4

2 vs. 3

2 vs. 4

3 vs. 4

Intensive care units

2 vs. 3

Medical patients

1 vs. 2

Surgical patients

1 vs. 3

1 vs. 4

2 vs. 3

2 vs. 4

3 vs. 4

Odds Ratio

of Death*

(95% CI)

Odds Ratio of Death*

0.94 (0.92–0.95)

0.76 (0.71–0.81)

0.62 (0.59–0.66)

0.81 (0.76–0.87)

0.66 (0.63–0.70)

0.82 (0.76–0.88)

0.94 (0.92–0.97)

0.94 (0.92–0.95)

0.76 (0.70–0.82)

0.62 (0.58–0.66)

0.80 (0.74–0.87)

0.65 (0.61–0.70)

0.81 (0.75–0.88)

0.5 1

Oddsratiosare based on pooled analysisconsistentacrossthe studies

(heterogeneity notsignificant).From reference27, with permission.

RN ⫽ registered nurse.

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

406 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2) www.annals.org

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

shift was within the mandated ratio.In logistic regression

analysesadjusted formany patientcharacteristicsand 3

hospitalcharacteristics(such asbed size,teaching status,

and technology use),Aiken and colleagues found statisti-

cally significant relationships between the estimation of the

average number of patients per nurse and 2 outcomes: 30-

day mortality and failure to rescue (11).

Although the study collected data after implementa-

tion of the California staffing mandate,it did not test the

effect of that mandate per se because it had no comparison

data from the period before the mandate went into effect.

The possibility that the relationship is causal is blunted by

longitudinalstudies thatexamined measures from before

and after the California mandate,which showed the ex-

pected changes in nurse staffing and proportion of licensed

staff per patient but no improvement in other patient out-

comes believed to be nursing-sensitive (such as falls,pres-

sure ulcers,and failure to rescue) (16,17,19).In fact,an

unexpected statistically significant increase in pressure ul-

cers was related to a greater number of hours of care for the

patient(which may have been because ofgreaterdetec-

tion). These studies did not assess mortality.

Five additionallongitudinalstudies add further infor-

mation to this picture.The firstis a longitudinalassess-

ment of nurse staffing and hospital mortality and failure to

rescue in 283 California hospitals between 1996 and 2001,

which had access to direct measures of nurse staffing (14).

In multivariable models that included many hospital mar-

ket characteristicsas well as risk adjustmentusing the

MedstatDisease Staging methodology to produce a pre-

dicted probability for complications or death,the authors

found that an increase of1 RN FTE per 1000 inpatient

dayswasrelated to a statistically significantdecrease in

mortality of 4.3%.

The second longitudinalstudy assessed careat 39

Michigan hospitalsbetween 2003 and 2006;it included

adults admitted through the emergency departmentwith

acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, pneumo-

nia,hip fracture,or gastrointestinalbleeding (15).This

study simultaneously controlled for 4 factors—high hospi-

taloccupancy on hospitalization,weekend hospitalization,

seasonal influenza, and nurse staffing levels—each of which

had a statistically significant effect on in-hospital mortality.

Each additionalRN FTE per patient day was related to a

0.25% decrease in mortality.

The third longitudinalstudy assessed the effectof a

mandate in 3 Western Australia public hospitals to imple-

ment a new staffing method,the Nursing Hours per Pa-

tient Day (12).The study assessed 3 periods:20 months

before implementation, 7 months of a “transition period,”

and 2 monthsafterimplementation.The authorsfound

that the totalnursing hours and RN hours increased dur-

ing the observation period.However,the percentage of

total nursing hours provided by RNs decreased (from 87%

to 84%). Also, the article stated that “although the nursing

hoursincreasedfor all threehospitals(in the post-

implementation period),the changes were not statistically

significant”(12). Mortalityrateswerereduced during

this period. Among many other outcomes, some impro

othersdid not, and somechangeswereinconsistent

across hospitals.Although the study was described as an

interrupted time series,it wasanalyzed asa before–after

study.

The fourth longitudinalstudyassessed changesin

nurse staffing over9 yearsin 124 Florida hospitalsand

related these to changes in Agency for Healthcare Res

and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (18). The study us

both initialstaffing ratiosand changesin staffing ratios.

Resultswere mixed butgenerally favored betterpatient

safety outcomes with higher RN staffing levels.

The methodologically strongestlongitudinalstudy is

thatof Needleman and colleagues(13).The researchers

used data overtime from a single hospitalto assessthe

relationship between naturaldifferencesin levelsof RN

staffing in the same hospitaland inpatient mortality.The

study isfurthercharacterized by a carefulmatching of

nurse staffing on a shift-by-shift basis with the actualpa-

tients cared for during that shift.Knowing the actualpa-

tients cared for allowed for more sophisticated adjustm

of risk for death at the patient level. The study was don

a tertiary academic hospitalbetween 2003 and 2006 and

included 197 691 hospitalizationsand 176 696 nursing

shifts across 43 hospital units. The patients themselves

eraged 60 years of age,and approximately 50% were cov-

ered under Medicare. The variable of interest was expo

of the patientto nursing care thatwasbelow the target

level(for that type of unit) for that shift (that is,the pro-

portion of shifts below target level staffing on a per-pat

basis).An additionalexposurevariablewas a “high-

turnover” shift (that is, a shift with many hospitalizatio

discharges,or transfers).The authors found that exposure

to each shift of below-target staffing or high turnover w

related to a 2% to 7% increase in mortality,with higher

levels of risk if the high-turnover or below-target shift o

curred in the first 5 days after hospitalization. For patie

who were not in an ICU,this risk was increased by 12%

and 15% during below-targetand high-turnovershifts,

respectively.

The data from Needleman and colleagues contribut

to the “causality” determination because the study is l

gitudinalin 1 hospital,thus controlling for the “hospital

effect” potentially present in all cross-sectional studies

has detailed measures ofexposure and confounding vari-

ables.These resultsand the dose–response analysisfrom

the meta-analysis provide the strongest evidence in su

of causality.

Harms

The survey administered as part of the cross-sectio

study previously described,which collected data 2 years

after the California mandate for minimum nurse staffin

ratios(11),found thatsome California nursesperceived

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

www.annals.org 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2)407

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

analysesadjusted formany patientcharacteristicsand 3

hospitalcharacteristics(such asbed size,teaching status,

and technology use),Aiken and colleagues found statisti-

cally significant relationships between the estimation of the

average number of patients per nurse and 2 outcomes: 30-

day mortality and failure to rescue (11).

Although the study collected data after implementa-

tion of the California staffing mandate,it did not test the

effect of that mandate per se because it had no comparison

data from the period before the mandate went into effect.

The possibility that the relationship is causal is blunted by

longitudinalstudies thatexamined measures from before

and after the California mandate,which showed the ex-

pected changes in nurse staffing and proportion of licensed

staff per patient but no improvement in other patient out-

comes believed to be nursing-sensitive (such as falls,pres-

sure ulcers,and failure to rescue) (16,17,19).In fact,an

unexpected statistically significant increase in pressure ul-

cers was related to a greater number of hours of care for the

patient(which may have been because ofgreaterdetec-

tion). These studies did not assess mortality.

Five additionallongitudinalstudies add further infor-

mation to this picture.The firstis a longitudinalassess-

ment of nurse staffing and hospital mortality and failure to

rescue in 283 California hospitals between 1996 and 2001,

which had access to direct measures of nurse staffing (14).

In multivariable models that included many hospital mar-

ket characteristicsas well as risk adjustmentusing the

MedstatDisease Staging methodology to produce a pre-

dicted probability for complications or death,the authors

found that an increase of1 RN FTE per 1000 inpatient

dayswasrelated to a statistically significantdecrease in

mortality of 4.3%.

The second longitudinalstudy assessed careat 39

Michigan hospitalsbetween 2003 and 2006;it included

adults admitted through the emergency departmentwith

acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, pneumo-

nia,hip fracture,or gastrointestinalbleeding (15).This

study simultaneously controlled for 4 factors—high hospi-

taloccupancy on hospitalization,weekend hospitalization,

seasonal influenza, and nurse staffing levels—each of which

had a statistically significant effect on in-hospital mortality.

Each additionalRN FTE per patient day was related to a

0.25% decrease in mortality.

The third longitudinalstudy assessed the effectof a

mandate in 3 Western Australia public hospitals to imple-

ment a new staffing method,the Nursing Hours per Pa-

tient Day (12).The study assessed 3 periods:20 months

before implementation, 7 months of a “transition period,”

and 2 monthsafterimplementation.The authorsfound

that the totalnursing hours and RN hours increased dur-

ing the observation period.However,the percentage of

total nursing hours provided by RNs decreased (from 87%

to 84%). Also, the article stated that “although the nursing

hoursincreasedfor all threehospitals(in the post-

implementation period),the changes were not statistically

significant”(12). Mortalityrateswerereduced during

this period. Among many other outcomes, some impro

othersdid not, and somechangeswereinconsistent

across hospitals.Although the study was described as an

interrupted time series,it wasanalyzed asa before–after

study.

The fourth longitudinalstudyassessed changesin

nurse staffing over9 yearsin 124 Florida hospitalsand

related these to changes in Agency for Healthcare Res

and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (18). The study us

both initialstaffing ratiosand changesin staffing ratios.

Resultswere mixed butgenerally favored betterpatient

safety outcomes with higher RN staffing levels.

The methodologically strongestlongitudinalstudy is

thatof Needleman and colleagues(13).The researchers

used data overtime from a single hospitalto assessthe

relationship between naturaldifferencesin levelsof RN

staffing in the same hospitaland inpatient mortality.The

study isfurthercharacterized by a carefulmatching of

nurse staffing on a shift-by-shift basis with the actualpa-

tients cared for during that shift.Knowing the actualpa-

tients cared for allowed for more sophisticated adjustm

of risk for death at the patient level. The study was don

a tertiary academic hospitalbetween 2003 and 2006 and

included 197 691 hospitalizationsand 176 696 nursing

shifts across 43 hospital units. The patients themselves

eraged 60 years of age,and approximately 50% were cov-

ered under Medicare. The variable of interest was expo

of the patientto nursing care thatwasbelow the target

level(for that type of unit) for that shift (that is,the pro-

portion of shifts below target level staffing on a per-pat

basis).An additionalexposurevariablewas a “high-

turnover” shift (that is, a shift with many hospitalizatio

discharges,or transfers).The authors found that exposure

to each shift of below-target staffing or high turnover w

related to a 2% to 7% increase in mortality,with higher

levels of risk if the high-turnover or below-target shift o

curred in the first 5 days after hospitalization. For patie

who were not in an ICU,this risk was increased by 12%

and 15% during below-targetand high-turnovershifts,

respectively.

The data from Needleman and colleagues contribut

to the “causality” determination because the study is l

gitudinalin 1 hospital,thus controlling for the “hospital

effect” potentially present in all cross-sectional studies

has detailed measures ofexposure and confounding vari-

ables.These resultsand the dose–response analysisfrom

the meta-analysis provide the strongest evidence in su

of causality.

Harms

The survey administered as part of the cross-sectio

study previously described,which collected data 2 years

after the California mandate for minimum nurse staffin

ratios(11),found thatsome California nursesperceived

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

www.annals.org 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2)407

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

that they had less support from the use of licensed voca-

tionalnurses,unlicensed personnel,and nonnursing sup-

port services (such as housekeeping and unit clerks) after

implementation of the mandate. For example, 25% of RNs

reported that they perceived that they had decreased use of

licensed vocational nurses after the mandate, whereas 10%

perceived thatthey had increased use and 56% reported

that use remained the same.

The longitudinal assessments from California (16 –19)

and Western Australia (12) reported an increase in pressure

ulcers related to increased nurse staffing, although this de-

velopment may reflect increased detection. Few other stud-

iesmentioned an explicitassessmentof potentialunex-

pected adverse outcomes.

IMPLEMENTATIONCONSIDERATIONS ANDCOSTS

Implementation Contexts

Because no published studies ofan assessment ofan

“implementation” were found,the contexts in which in-

terventions have been implemented cannot be directly as-

sessed. However, the cross-sectional and longitudinal stud-

ies that have been published and have consistently shown a

relationship between staffing levels and patientoutcomes

have included a broad array of hospitals, often all or nearly

all of the hospitals (except for very smallones) in a state.

Therefore,if the relationship between increased RN staff-

ing and inpatient mortality is a causalone,it very likely

appliesto mosthospitalsand contexts.This strategy is

most likely to be implemented when mandated by state or

federalpolicy.

As previously noted,the relationship between staffing

and mortality that underpins this strategy has been seen in

various hospitals and contexts. The effect, if causal, is prob-

ably relatively insensitive to the usualeffectsof contexts

considered in other patient safety strategy reviews. Of note,

the recentstudy by Needleman and colleagueswascon-

ducted in a tertiary medicalcenter that has a lower-than-

expected in-hospitalmortality rate and a reputation for

excellence.Therefore,the relationship between increased

RN staffing and lowermortality,if causal,is potentially

applicable even to high-performing hospitals.

Costs

Four simulation studiesreported information about

costs.The firstused 2003 data from 28 Belgian cardiac

surgery centers to assess the costs and outcomes of increas-

ing nurse staffing. Assuming a causalrelationship between

thisstaffing increase and an outcome of5 fewer patient

deaths per 1000 elective hospitalizations,the authors con-

cluded thatthe incrementalcost-effectivenessratio was

€26 372 (approximately $35 000) per avoided death and

€2639 (approximately $3500) per life-year gained (21).

The second simulation study wasconducted by the

University ofMinnesota Evidence-based Practice Center,

which produced the systematic review on nurse staffing

(22). It used its own meta-analysis as the basis for estimat-

ing the potentialmonetary benefits of increased RN staff-

ing. Assuming that those relationships were causal and

ing a societalperspective,the authorsconcluded that

increasing RN staffing by 1 FTE per patient day was re-

lated to positive savings– cost ratios across a broad ran

clinical settings. For example, the net cost of adding 1

FTE per 1000 hospitalized ICU patients was an estimate

$590 000,whereas the netbenefit(in terms oflife-years

saved and productivity) was an estimated $1.5 million,

a benefit– costratio of2.51.However,hospitalsdid not

save money because the netcostof adding an extra RN

FTE was not offset by the expected 24% decrease in le

of stay.

A third simulation study (24) used data from studie

by Aiken and colleagues and Needleman and colleague

estimate benefits in mortality and length ofstay,respec-

tively, and estimated an incremental cost-effectiveness

between $25 000 and $136 000 per life saved as patie

RN staffing ratios decreased from 8:1 to 4:1.The model

was most sensitive to the estimate of effect on mortali

Lastly, 1 additional study from Portugal estimated t

increasing neonatalnurse staffing to “adequate” would in-

crease staff costs more than 30% of the current rate (2

DISCUSSION

Nurse staffing ratioshave a relationship with reduc-

tions in hospital-related mortality in most published stu

ies.However,lack of a published evaluation of an inten-

tionalchange in RN staffing from some initialvalue (for

example, 6 patients to 1 RN on general medical wards)

some lower patient–RN staffing value (such as 5:1 or 4

limits conclusions on increasing nurse staffing ratios as

patient safety strategy. All longitudinal published studi

date have assessed naturalvariations in RN staffing.The

concern also remains that mortality is not reduced by i

creased nurse staffing but by something the nurses do

termining what this is and how it can best be facilitated

should be the goalof an effective patient safety strategy.

Limitations of this review include those of the origin

articles,such as lack ofrigorous evaluations ofan inten-

tionalintervention,low response rates to surveys that col-

lect explanatory variables (such as RN staffing), potent

poor matching of RN staffing to actualpatients cared for

and their risk for death,and lack ofreplication ofthe 1

high-quality longitudinalstudy thathasbeen published;

and the possibility thatsome relevantevidence wasnot

found,eitherbecauseit wasnot identified during the

search orbecause some completed evaluationshave not

been unpublished.

To further advance this field,studies assessing an in-

tentional change in nurse staffing ratios are needed. It

be impracticalfor such a study to be a randomized,con-

trolled trial,but high-quality evidence could come from a

time series analysis or a controlled before-and-after stu

particularly if it included the necessary process variabl

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

408 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2) www.annals.org

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

tionalnurses,unlicensed personnel,and nonnursing sup-

port services (such as housekeeping and unit clerks) after

implementation of the mandate. For example, 25% of RNs

reported that they perceived that they had decreased use of

licensed vocational nurses after the mandate, whereas 10%

perceived thatthey had increased use and 56% reported

that use remained the same.

The longitudinal assessments from California (16 –19)

and Western Australia (12) reported an increase in pressure

ulcers related to increased nurse staffing, although this de-

velopment may reflect increased detection. Few other stud-

iesmentioned an explicitassessmentof potentialunex-

pected adverse outcomes.

IMPLEMENTATIONCONSIDERATIONS ANDCOSTS

Implementation Contexts

Because no published studies ofan assessment ofan

“implementation” were found,the contexts in which in-

terventions have been implemented cannot be directly as-

sessed. However, the cross-sectional and longitudinal stud-

ies that have been published and have consistently shown a

relationship between staffing levels and patientoutcomes

have included a broad array of hospitals, often all or nearly

all of the hospitals (except for very smallones) in a state.

Therefore,if the relationship between increased RN staff-

ing and inpatient mortality is a causalone,it very likely

appliesto mosthospitalsand contexts.This strategy is

most likely to be implemented when mandated by state or

federalpolicy.

As previously noted,the relationship between staffing

and mortality that underpins this strategy has been seen in

various hospitals and contexts. The effect, if causal, is prob-

ably relatively insensitive to the usualeffectsof contexts

considered in other patient safety strategy reviews. Of note,

the recentstudy by Needleman and colleagueswascon-

ducted in a tertiary medicalcenter that has a lower-than-

expected in-hospitalmortality rate and a reputation for

excellence.Therefore,the relationship between increased

RN staffing and lowermortality,if causal,is potentially

applicable even to high-performing hospitals.

Costs

Four simulation studiesreported information about

costs.The firstused 2003 data from 28 Belgian cardiac

surgery centers to assess the costs and outcomes of increas-

ing nurse staffing. Assuming a causalrelationship between

thisstaffing increase and an outcome of5 fewer patient

deaths per 1000 elective hospitalizations,the authors con-

cluded thatthe incrementalcost-effectivenessratio was

€26 372 (approximately $35 000) per avoided death and

€2639 (approximately $3500) per life-year gained (21).

The second simulation study wasconducted by the

University ofMinnesota Evidence-based Practice Center,

which produced the systematic review on nurse staffing

(22). It used its own meta-analysis as the basis for estimat-

ing the potentialmonetary benefits of increased RN staff-

ing. Assuming that those relationships were causal and

ing a societalperspective,the authorsconcluded that

increasing RN staffing by 1 FTE per patient day was re-

lated to positive savings– cost ratios across a broad ran

clinical settings. For example, the net cost of adding 1

FTE per 1000 hospitalized ICU patients was an estimate

$590 000,whereas the netbenefit(in terms oflife-years

saved and productivity) was an estimated $1.5 million,

a benefit– costratio of2.51.However,hospitalsdid not

save money because the netcostof adding an extra RN

FTE was not offset by the expected 24% decrease in le

of stay.

A third simulation study (24) used data from studie

by Aiken and colleagues and Needleman and colleague

estimate benefits in mortality and length ofstay,respec-

tively, and estimated an incremental cost-effectiveness

between $25 000 and $136 000 per life saved as patie

RN staffing ratios decreased from 8:1 to 4:1.The model

was most sensitive to the estimate of effect on mortali

Lastly, 1 additional study from Portugal estimated t

increasing neonatalnurse staffing to “adequate” would in-

crease staff costs more than 30% of the current rate (2

DISCUSSION

Nurse staffing ratioshave a relationship with reduc-

tions in hospital-related mortality in most published stu

ies.However,lack of a published evaluation of an inten-

tionalchange in RN staffing from some initialvalue (for

example, 6 patients to 1 RN on general medical wards)

some lower patient–RN staffing value (such as 5:1 or 4

limits conclusions on increasing nurse staffing ratios as

patient safety strategy. All longitudinal published studi

date have assessed naturalvariations in RN staffing.The

concern also remains that mortality is not reduced by i

creased nurse staffing but by something the nurses do

termining what this is and how it can best be facilitated

should be the goalof an effective patient safety strategy.

Limitations of this review include those of the origin

articles,such as lack ofrigorous evaluations ofan inten-

tionalintervention,low response rates to surveys that col-

lect explanatory variables (such as RN staffing), potent

poor matching of RN staffing to actualpatients cared for

and their risk for death,and lack ofreplication ofthe 1

high-quality longitudinalstudy thathasbeen published;

and the possibility thatsome relevantevidence wasnot

found,eitherbecauseit wasnot identified during the

search orbecause some completed evaluationshave not

been unpublished.

To further advance this field,studies assessing an in-

tentional change in nurse staffing ratios are needed. It

be impracticalfor such a study to be a randomized,con-

trolled trial,but high-quality evidence could come from a

time series analysis or a controlled before-and-after stu

particularly if it included the necessary process variabl

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

408 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2) www.annals.org

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

serve as a test of a conceptual framework for how increased

staffing can influence outcomes.

From theRAND Corporation,SantaMonica,and VeteransAffairs

Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California.

Note:The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reviewed con-

tract deliverables to ensure adherence to contract requirements and qual-

ity, and a copyright release was obtained from the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality before submission of the manuscript.

Disclaimer:All statements expressed in this work are those of the author

and should not in any way be construed as official opinions or positions

of the RAND Corporation, Veterans Affairs, the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality,or the U.S.Department of Health and Human

Services.

Acknowledgment:The author thanks Robert Kane,MD; Eileen Lake,

PhD, RN; Aneesa Motala,BA; Sydne Newberry,PhD; and Roberta

Shanman, MLS.

Financial Support:From the Agency for Healthcare Research and Qual-

ity,U.S.Department of Health and Human Services (contract HHSA-

290-2007-10062I).

PotentialConflicts ofInterest:Consultancy:ECRI Institute;Employ-

ment: Veterans Affairs; Grants/grants pending: Agency for Healthcare Re-

search and Quality,Veterans Affairs,Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services, National Institute of Nursing Research, Office of the National

Coordinator; Royalties: UpToDate. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.

acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum⫽M12

-2574.

Requests forSingle Reprints:PaulG. Shekelle,MD, MPH, RAND

Corporation,1776 Main Street,SantaMonica,CA 90401;e-mail,

shekelle@rand.org.

Author contributions are available at www.annals.org.

References

1. Aiken LH,Clarke SP,Sloane DM,SochalskiJ, Silber JH.Hospitalnurse

staffing and patientmortality,nurse burnout,and job dissatisfaction.JAMA.

2002;288:1987-93. [PMID: 12387650]

2. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital

care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2008;

38:223-9. [PMID: 18469615]

3. Tourangeau AE, Giovannetti P, Tu JV, Wood M. Nursing-related determi-

nants of 30-day mortality for hospitalized patients. Can J Nurs Res. 2002;33:71-

88. [PMID: 11998198]

4. Person SD, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Weaver MT, Williams OD, Centor RM,

et al. Nurse staffing and mortality for Medicare patients with acute myocardial

infarction. Med Care. 2004;42:4-12. [PMID: 14713734]

5. Tourangeau AE, Doran DM, McGillis Hall L, O’Brien Pallas L, Pringle D,

Tu JV,etal.Impactof hospitalnursing care on 30-day mortality for acute

medical patients. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:32-44. [PMID: 17184372]

6. Thornlow DK, Anderson R, Oddone E. Cascade iatrogenesis: factors leading

to the development of adverse events in hospitalized older adults. Int J Nurs Stud.

2009;46:1528-35. [PMID: 19643409]

7. Despins LA,Scott-CawiezellJ, Rouder JN.Detection ofpatientrisk by

nurses: a theoretical framework. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:465-74. [PMID: 20423428]

8. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM. Hospital staffing, organization, and quality

of care:cross-nationalfindings.Nurs Outlook.2002;50:187-94.[PMID:

12386653]

9. Aiken LH, Sochalski J, Lake ET. Studying outcomes of organizatio

in health services. Med Care. 1997;35:NS6-18. [PMID: 9366875]

10.Whitlock EP,Lin JS,Chou R,Shekelle P,Robinson KA.Using existing

systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews.Ann Intern Med.2008;148:

776-82. [PMID: 18490690]

11. Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Clarke SP, Flynn L, Seago

Implications of the California nurse staffing mandate for other states. H

Res. 2010;45:904-21. [PMID: 20403061]

12.Twigg D,Duffield C,Bremner A,Rapley P,Finn J.The impact of the

nursing hours per patient day (NHPPD) staffing method on patient outco

retrospective analysisof patientand staffing data.Int J Nurs Stud.2011;48:

540-8. [PMID: 20696429]

13. Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Pankratz VS, Leibson CL, Stevens

M. Nurse staffing and inpatient hospitalmortality.N EnglJ Med.2011;364:

1037-45. [PMID: 21410372]

14. Harless DW, Mark BA. Nurse staffing and quality of care with dire

surement of inpatient staffing. Med Care. 2010;48:659-63. [PMID: 2054

15. Schilling PL, Campbell DA Jr, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comp

in-hospitalmortality risk conferred by high hospitaloccupancy,differences in

nurse staffing levels,weekend admission,and seasonalinfluenza.Med Care.

2010;48:224-32. [PMID: 20168260]

16. Burnes Bolton L, Aydin CE, Donaldson N, Brown DS, Sandhu

man M,et al.Mandated nurse staffing ratios in California:a comparison of

staffing and nursing-sensitive outcomes pre- and postregulation. Policy

Pract. 2007;8:238-50. [PMID: 18337430]

17.Donaldson N,Bolton LB,Aydin C,Brown D,Elashoff JD,Sandhu M.

Impact ofCalifornia’s licensed nurse-patient ratios on unit-levelnurse staffing

and patientoutcomes.PolicyPolit Nurs Pract.2005;6:198-210.[PMID:

16443975]

18.Unruh LY,Zhang NJ.Nurse staffing and patient safety in hospitals:new

variableand longitudinalapproaches.Nurs Res. 2012;61:3-12.[PMID:

22166905]

19. Cook A, Gaynor M, Stephens M Jr, Taylor L. The effect of a hos

staffing mandate on patient health outcomes:evidence from California’s mini-

mum staffing regulation. J Health Econ. 2012;31:340-8. [PMID: 2242576

20. Duffield C, Diers D, O’Brien-Pallas L, Aisbett C, Roche M, Kin

Nursing staffing, nursing workload, the work environment and patient o

Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24:244-55. [PMID: 20974086]

21. Van den Heede K, Simoens S, Diya L, Lesaffre E, Vleugels A,

Increasing nurse staffing levels in Belgian cardiac surgery centres: a co

patient safety intervention? J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1291-6. [PMID: 205463

22. Shamliyan TA, Kane RL, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ. Cost savi

ciated with increased RN staffing in acute care hospitals:simulation exercise.

Nurs Econ. 2009;27:302-14, 331. [PMID: 19927445]

23. Fugulin FMT, Lima AFC, Castilho V, Bochembuzio L, Costa JA

et al. Cost of nursing staffing adequacy in a neonatal unit. Revista da E

Enfermagem da Usp. 2011;45:1582-8.

24. Rothberg MB, Abraham I, Lindenauer PK, Rose DN. Improving

patient staffing ratios as a cost-effective safety intervention. Med Care.

785-91. [PMID: 16034292]

25. McGahan M, Kucharski G, Coyer F; Winner ACCCN Best Nurs

view Paper 2011 sponsored by Elsevier. Nurse staffing levels and t

of mortality and morbidity in the adult intensive care unit:a literature review.

Aust Crit Care. 2012;25:64-77. [PMID: 22515951]

26. Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Ham

Developmentof AMSTAR:a measurementtoolto assess the methodological

quality ofsystematic reviews.BMC Med Res Methodol.2007;7:10.[PMID:

17302989]

27. Kane RL, Shamliyan TA, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ. The assoc

registered nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: systematic revie

analysis. Med Care. 2007;45:1195-204. [PMID: 18007170]

28. Tourangeau AE. Mortality rate as a nurse-sensitive outcome. In: D

Nursing Outcomes:The State of the Science.Sudbury,MA: Jones & Bartlett;

2011.

29. Furukawa MF, Raghu TS, Shao BB. Electronic medical records,

ing,and nurse-sensitive patientoutcomes:evidence from California hospitals,

1998-2007. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:941-62. [PMID: 20403065]

30. Griffiths P. RN⫹RN⫽better care? What do we know about the asso

between the number of nurses and patient outcomes? [Editorial]. Int J N

2009;46:1289-90. [PMID: 19647533]

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

www.annals.org 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2)409

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

staffing can influence outcomes.

From theRAND Corporation,SantaMonica,and VeteransAffairs

Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California.

Note:The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reviewed con-

tract deliverables to ensure adherence to contract requirements and qual-

ity, and a copyright release was obtained from the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality before submission of the manuscript.

Disclaimer:All statements expressed in this work are those of the author

and should not in any way be construed as official opinions or positions

of the RAND Corporation, Veterans Affairs, the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality,or the U.S.Department of Health and Human

Services.

Acknowledgment:The author thanks Robert Kane,MD; Eileen Lake,

PhD, RN; Aneesa Motala,BA; Sydne Newberry,PhD; and Roberta

Shanman, MLS.

Financial Support:From the Agency for Healthcare Research and Qual-

ity,U.S.Department of Health and Human Services (contract HHSA-

290-2007-10062I).

PotentialConflicts ofInterest:Consultancy:ECRI Institute;Employ-

ment: Veterans Affairs; Grants/grants pending: Agency for Healthcare Re-

search and Quality,Veterans Affairs,Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services, National Institute of Nursing Research, Office of the National

Coordinator; Royalties: UpToDate. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.

acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum⫽M12

-2574.

Requests forSingle Reprints:PaulG. Shekelle,MD, MPH, RAND

Corporation,1776 Main Street,SantaMonica,CA 90401;e-mail,

shekelle@rand.org.

Author contributions are available at www.annals.org.

References

1. Aiken LH,Clarke SP,Sloane DM,SochalskiJ, Silber JH.Hospitalnurse

staffing and patientmortality,nurse burnout,and job dissatisfaction.JAMA.

2002;288:1987-93. [PMID: 12387650]

2. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital

care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2008;

38:223-9. [PMID: 18469615]

3. Tourangeau AE, Giovannetti P, Tu JV, Wood M. Nursing-related determi-

nants of 30-day mortality for hospitalized patients. Can J Nurs Res. 2002;33:71-

88. [PMID: 11998198]

4. Person SD, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Weaver MT, Williams OD, Centor RM,

et al. Nurse staffing and mortality for Medicare patients with acute myocardial

infarction. Med Care. 2004;42:4-12. [PMID: 14713734]

5. Tourangeau AE, Doran DM, McGillis Hall L, O’Brien Pallas L, Pringle D,

Tu JV,etal.Impactof hospitalnursing care on 30-day mortality for acute

medical patients. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:32-44. [PMID: 17184372]

6. Thornlow DK, Anderson R, Oddone E. Cascade iatrogenesis: factors leading

to the development of adverse events in hospitalized older adults. Int J Nurs Stud.

2009;46:1528-35. [PMID: 19643409]

7. Despins LA,Scott-CawiezellJ, Rouder JN.Detection ofpatientrisk by

nurses: a theoretical framework. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:465-74. [PMID: 20423428]

8. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM. Hospital staffing, organization, and quality

of care:cross-nationalfindings.Nurs Outlook.2002;50:187-94.[PMID:

12386653]

9. Aiken LH, Sochalski J, Lake ET. Studying outcomes of organizatio

in health services. Med Care. 1997;35:NS6-18. [PMID: 9366875]

10.Whitlock EP,Lin JS,Chou R,Shekelle P,Robinson KA.Using existing

systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews.Ann Intern Med.2008;148:

776-82. [PMID: 18490690]

11. Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Clarke SP, Flynn L, Seago

Implications of the California nurse staffing mandate for other states. H

Res. 2010;45:904-21. [PMID: 20403061]

12.Twigg D,Duffield C,Bremner A,Rapley P,Finn J.The impact of the

nursing hours per patient day (NHPPD) staffing method on patient outco

retrospective analysisof patientand staffing data.Int J Nurs Stud.2011;48:

540-8. [PMID: 20696429]

13. Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Pankratz VS, Leibson CL, Stevens

M. Nurse staffing and inpatient hospitalmortality.N EnglJ Med.2011;364:

1037-45. [PMID: 21410372]

14. Harless DW, Mark BA. Nurse staffing and quality of care with dire

surement of inpatient staffing. Med Care. 2010;48:659-63. [PMID: 2054

15. Schilling PL, Campbell DA Jr, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comp

in-hospitalmortality risk conferred by high hospitaloccupancy,differences in

nurse staffing levels,weekend admission,and seasonalinfluenza.Med Care.

2010;48:224-32. [PMID: 20168260]

16. Burnes Bolton L, Aydin CE, Donaldson N, Brown DS, Sandhu

man M,et al.Mandated nurse staffing ratios in California:a comparison of

staffing and nursing-sensitive outcomes pre- and postregulation. Policy

Pract. 2007;8:238-50. [PMID: 18337430]

17.Donaldson N,Bolton LB,Aydin C,Brown D,Elashoff JD,Sandhu M.

Impact ofCalifornia’s licensed nurse-patient ratios on unit-levelnurse staffing

and patientoutcomes.PolicyPolit Nurs Pract.2005;6:198-210.[PMID:

16443975]

18.Unruh LY,Zhang NJ.Nurse staffing and patient safety in hospitals:new

variableand longitudinalapproaches.Nurs Res. 2012;61:3-12.[PMID:

22166905]

19. Cook A, Gaynor M, Stephens M Jr, Taylor L. The effect of a hos

staffing mandate on patient health outcomes:evidence from California’s mini-

mum staffing regulation. J Health Econ. 2012;31:340-8. [PMID: 2242576

20. Duffield C, Diers D, O’Brien-Pallas L, Aisbett C, Roche M, Kin

Nursing staffing, nursing workload, the work environment and patient o

Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24:244-55. [PMID: 20974086]

21. Van den Heede K, Simoens S, Diya L, Lesaffre E, Vleugels A,

Increasing nurse staffing levels in Belgian cardiac surgery centres: a co

patient safety intervention? J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1291-6. [PMID: 205463

22. Shamliyan TA, Kane RL, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ. Cost savi

ciated with increased RN staffing in acute care hospitals:simulation exercise.

Nurs Econ. 2009;27:302-14, 331. [PMID: 19927445]

23. Fugulin FMT, Lima AFC, Castilho V, Bochembuzio L, Costa JA

et al. Cost of nursing staffing adequacy in a neonatal unit. Revista da E

Enfermagem da Usp. 2011;45:1582-8.

24. Rothberg MB, Abraham I, Lindenauer PK, Rose DN. Improving

patient staffing ratios as a cost-effective safety intervention. Med Care.

785-91. [PMID: 16034292]

25. McGahan M, Kucharski G, Coyer F; Winner ACCCN Best Nurs

view Paper 2011 sponsored by Elsevier. Nurse staffing levels and t

of mortality and morbidity in the adult intensive care unit:a literature review.

Aust Crit Care. 2012;25:64-77. [PMID: 22515951]

26. Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Ham

Developmentof AMSTAR:a measurementtoolto assess the methodological

quality ofsystematic reviews.BMC Med Res Methodol.2007;7:10.[PMID:

17302989]

27. Kane RL, Shamliyan TA, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ. The assoc

registered nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: systematic revie

analysis. Med Care. 2007;45:1195-204. [PMID: 18007170]

28. Tourangeau AE. Mortality rate as a nurse-sensitive outcome. In: D

Nursing Outcomes:The State of the Science.Sudbury,MA: Jones & Bartlett;

2011.

29. Furukawa MF, Raghu TS, Shao BB. Electronic medical records,

ing,and nurse-sensitive patientoutcomes:evidence from California hospitals,

1998-2007. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:941-62. [PMID: 20403065]

30. Griffiths P. RN⫹RN⫽better care? What do we know about the asso

between the number of nurses and patient outcomes? [Editorial]. Int J N

2009;46:1289-90. [PMID: 19647533]

SupplementNurse–Patient Ratios as a Patient Safety Strategy

www.annals.org 5 March 2013 Annals of Internal MedicineVolume 158 • Number 5 (Part 2)409

Downloaded from https://annals.org by India: ANNALS Sponsored user on 05/15/2019

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Author Contributions:Conception and design:P.G. Shekelle.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: P.G. Shekelle.

Drafting of the article: P.G. Shekelle.

Criticalrevisionof the articlefor importantintellectualcontent:

P.G. Shekelle.

Finalapprovalof the article: P.G. Shekelle.

Obtaining of funding: P.G. Shekelle.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: P.G. Shekelle.

Collection and assembly of data: P.G. Shekelle.

31.Stone PW,Pogorzelska M,Kunches L,Hirschhorn LR.Hospitalstaffing

and health care-associated infections:a systematic review of the literature.Clin

Infect Dis. 2008;47:937-44. [PMID: 18767987]

32. Cummings GG, MacGregor T, Davey M, Lee H, Wong CA, Lo E, et al.

Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work en-

vironment:a systematic review.Int J NursStud.2010;47:363-85.[PMID:

19781702]

33. Butler M, Collins R, Drennan J, Halligan P, O’Mathu´na DP, Schultz TJ,

et al. Hospital nurse staffing models and patient and staff-related outcomes. Co-

chrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD007019. [PMID: 21735407]