LAWS20060 Taxation Law of Australia: Comprehensive Legal Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/08

|12

|3361

|75

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment solution delves into various aspects of Australian Taxation Law, addressing key concepts such as the functions of the tax system, equity in taxation, calculation of taxable income, and the impact of progressive tax systems. It identifies relevant sections of the ITAA 1997 and tax rulings, including TR 2004/15, and analyzes tax residency rules, particularly concerning individuals like Martelle, by applying domicile, superannuation, and 183-day tests alongside the residency test considering factors like purpose of visit, ties, and asset location. Furthermore, it examines the tax treatment of different income types, computes taxable income, and calculates tax payable, including Medicare levy. The solution also discusses depreciation methods for business assets under s. 40-60 ITAA 1997, contrasting prime cost and diminishing value methods, and differentiates between business and hobby activities based on intention to profit and other factors outlined in TR 97/11. Desklib offers a platform for students to access this and many other solved assignments.

TAXATION LAW IN AUSTRALIA

STUDENT ID:

[Pick the date]

STUDENT ID:

[Pick the date]

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

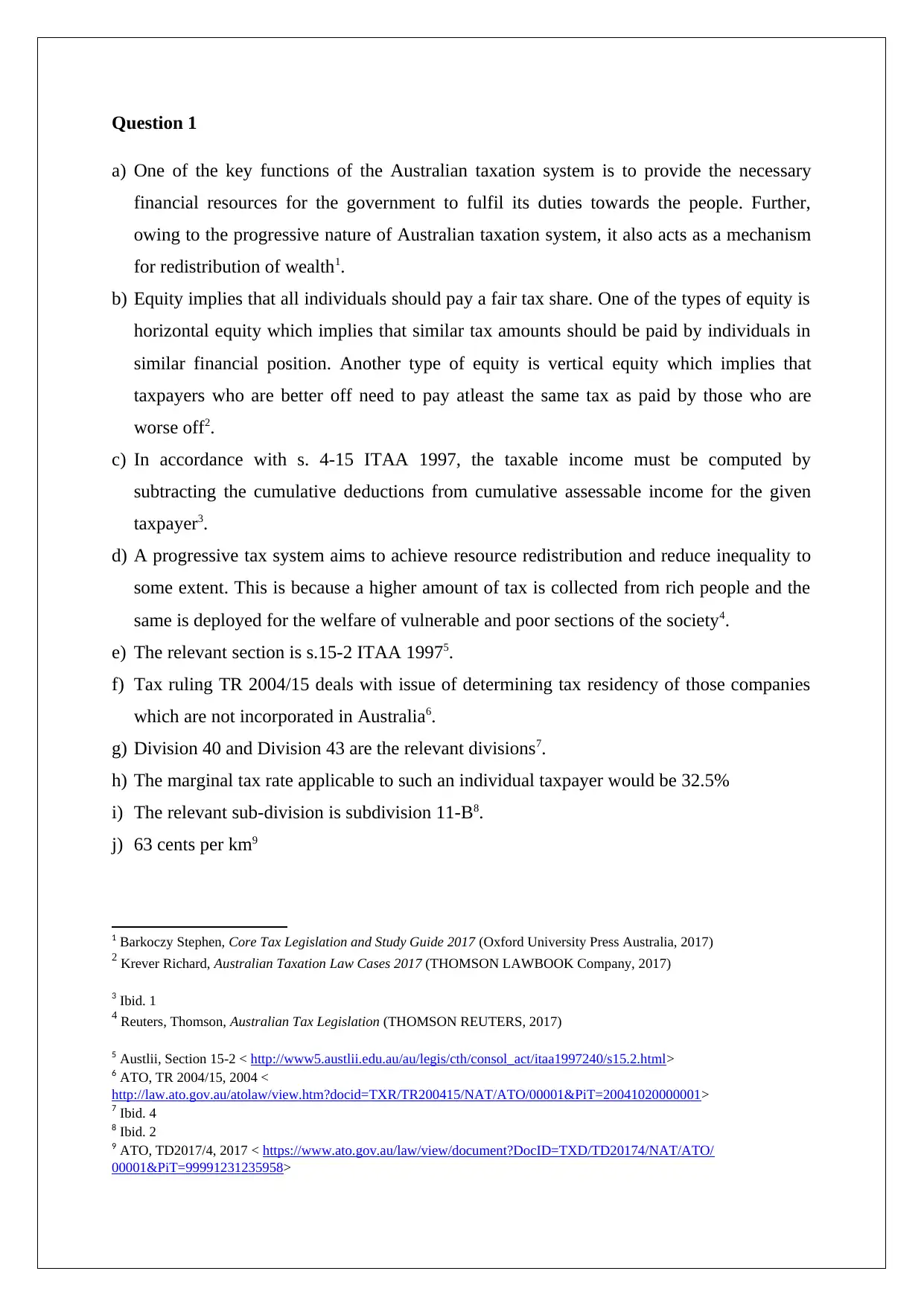

Question 1

a) One of the key functions of the Australian taxation system is to provide the necessary

financial resources for the government to fulfil its duties towards the people. Further,

owing to the progressive nature of Australian taxation system, it also acts as a mechanism

for redistribution of wealth1.

b) Equity implies that all individuals should pay a fair tax share. One of the types of equity is

horizontal equity which implies that similar tax amounts should be paid by individuals in

similar financial position. Another type of equity is vertical equity which implies that

taxpayers who are better off need to pay atleast the same tax as paid by those who are

worse off2.

c) In accordance with s. 4-15 ITAA 1997, the taxable income must be computed by

subtracting the cumulative deductions from cumulative assessable income for the given

taxpayer3.

d) A progressive tax system aims to achieve resource redistribution and reduce inequality to

some extent. This is because a higher amount of tax is collected from rich people and the

same is deployed for the welfare of vulnerable and poor sections of the society4.

e) The relevant section is s.15-2 ITAA 19975.

f) Tax ruling TR 2004/15 deals with issue of determining tax residency of those companies

which are not incorporated in Australia6.

g) Division 40 and Division 43 are the relevant divisions7.

h) The marginal tax rate applicable to such an individual taxpayer would be 32.5%

i) The relevant sub-division is subdivision 11-B8.

j) 63 cents per km9

1 Barkoczy Stephen, Core Tax Legislation and Study Guide 2017 (Oxford University Press Australia, 2017)

2 Krever Richard, Australian Taxation Law Cases 2017 (THOMSON LAWBOOK Company, 2017)

3 Ibid. 1

4 Reuters, Thomson, Australian Tax Legislation (THOMSON REUTERS, 2017)

5 Austlii, Section 15-2 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s15.2.html>

6 ATO, TR 2004/15, 2004 <

http://law.ato.gov.au/atolaw/view.htm?docid=TXR/TR200415/NAT/ATO/00001&PiT=20041020000001>

7 Ibid. 4

8 Ibid. 2

9 ATO, TD2017/4, 2017 < https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXD/TD20174/NAT/ATO/

00001&PiT=99991231235958>

a) One of the key functions of the Australian taxation system is to provide the necessary

financial resources for the government to fulfil its duties towards the people. Further,

owing to the progressive nature of Australian taxation system, it also acts as a mechanism

for redistribution of wealth1.

b) Equity implies that all individuals should pay a fair tax share. One of the types of equity is

horizontal equity which implies that similar tax amounts should be paid by individuals in

similar financial position. Another type of equity is vertical equity which implies that

taxpayers who are better off need to pay atleast the same tax as paid by those who are

worse off2.

c) In accordance with s. 4-15 ITAA 1997, the taxable income must be computed by

subtracting the cumulative deductions from cumulative assessable income for the given

taxpayer3.

d) A progressive tax system aims to achieve resource redistribution and reduce inequality to

some extent. This is because a higher amount of tax is collected from rich people and the

same is deployed for the welfare of vulnerable and poor sections of the society4.

e) The relevant section is s.15-2 ITAA 19975.

f) Tax ruling TR 2004/15 deals with issue of determining tax residency of those companies

which are not incorporated in Australia6.

g) Division 40 and Division 43 are the relevant divisions7.

h) The marginal tax rate applicable to such an individual taxpayer would be 32.5%

i) The relevant sub-division is subdivision 11-B8.

j) 63 cents per km9

1 Barkoczy Stephen, Core Tax Legislation and Study Guide 2017 (Oxford University Press Australia, 2017)

2 Krever Richard, Australian Taxation Law Cases 2017 (THOMSON LAWBOOK Company, 2017)

3 Ibid. 1

4 Reuters, Thomson, Australian Tax Legislation (THOMSON REUTERS, 2017)

5 Austlii, Section 15-2 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s15.2.html>

6 ATO, TR 2004/15, 2004 <

http://law.ato.gov.au/atolaw/view.htm?docid=TXR/TR200415/NAT/ATO/00001&PiT=20041020000001>

7 Ibid. 4

8 Ibid. 2

9 ATO, TD2017/4, 2017 < https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXD/TD20174/NAT/ATO/

00001&PiT=99991231235958>

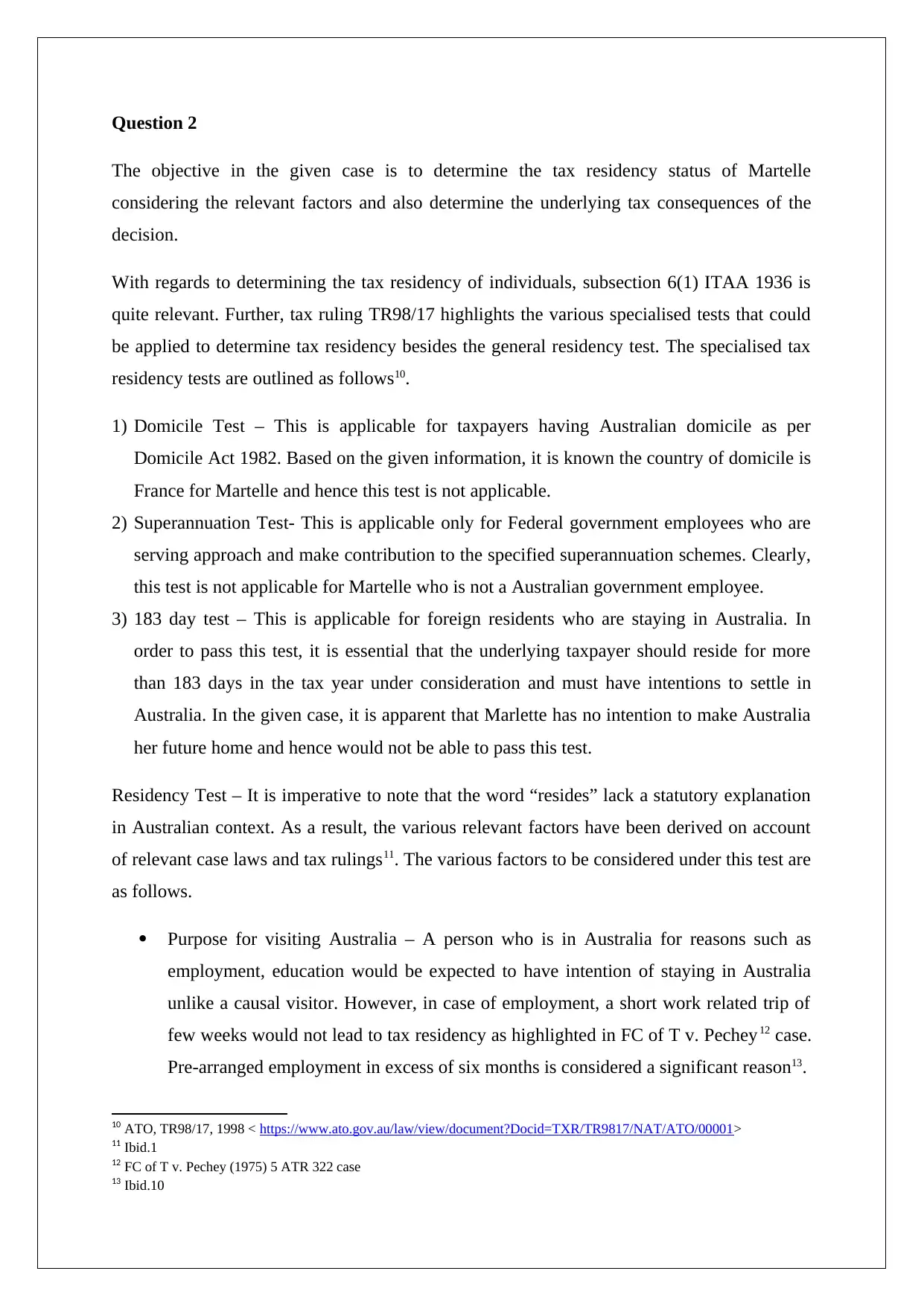

Question 2

The objective in the given case is to determine the tax residency status of Martelle

considering the relevant factors and also determine the underlying tax consequences of the

decision.

With regards to determining the tax residency of individuals, subsection 6(1) ITAA 1936 is

quite relevant. Further, tax ruling TR98/17 highlights the various specialised tests that could

be applied to determine tax residency besides the general residency test. The specialised tax

residency tests are outlined as follows10.

1) Domicile Test – This is applicable for taxpayers having Australian domicile as per

Domicile Act 1982. Based on the given information, it is known the country of domicile is

France for Martelle and hence this test is not applicable.

2) Superannuation Test- This is applicable only for Federal government employees who are

serving approach and make contribution to the specified superannuation schemes. Clearly,

this test is not applicable for Martelle who is not a Australian government employee.

3) 183 day test – This is applicable for foreign residents who are staying in Australia. In

order to pass this test, it is essential that the underlying taxpayer should reside for more

than 183 days in the tax year under consideration and must have intentions to settle in

Australia. In the given case, it is apparent that Marlette has no intention to make Australia

her future home and hence would not be able to pass this test.

Residency Test – It is imperative to note that the word “resides” lack a statutory explanation

in Australian context. As a result, the various relevant factors have been derived on account

of relevant case laws and tax rulings11. The various factors to be considered under this test are

as follows.

Purpose for visiting Australia – A person who is in Australia for reasons such as

employment, education would be expected to have intention of staying in Australia

unlike a causal visitor. However, in case of employment, a short work related trip of

few weeks would not lead to tax residency as highlighted in FC of T v. Pechey12 case.

Pre-arranged employment in excess of six months is considered a significant reason13.

10 ATO, TR98/17, 1998 < https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?Docid=TXR/TR9817/NAT/ATO/00001>

11 Ibid.1

12 FC of T v. Pechey (1975) 5 ATR 322 case

13 Ibid.10

The objective in the given case is to determine the tax residency status of Martelle

considering the relevant factors and also determine the underlying tax consequences of the

decision.

With regards to determining the tax residency of individuals, subsection 6(1) ITAA 1936 is

quite relevant. Further, tax ruling TR98/17 highlights the various specialised tests that could

be applied to determine tax residency besides the general residency test. The specialised tax

residency tests are outlined as follows10.

1) Domicile Test – This is applicable for taxpayers having Australian domicile as per

Domicile Act 1982. Based on the given information, it is known the country of domicile is

France for Martelle and hence this test is not applicable.

2) Superannuation Test- This is applicable only for Federal government employees who are

serving approach and make contribution to the specified superannuation schemes. Clearly,

this test is not applicable for Martelle who is not a Australian government employee.

3) 183 day test – This is applicable for foreign residents who are staying in Australia. In

order to pass this test, it is essential that the underlying taxpayer should reside for more

than 183 days in the tax year under consideration and must have intentions to settle in

Australia. In the given case, it is apparent that Marlette has no intention to make Australia

her future home and hence would not be able to pass this test.

Residency Test – It is imperative to note that the word “resides” lack a statutory explanation

in Australian context. As a result, the various relevant factors have been derived on account

of relevant case laws and tax rulings11. The various factors to be considered under this test are

as follows.

Purpose for visiting Australia – A person who is in Australia for reasons such as

employment, education would be expected to have intention of staying in Australia

unlike a causal visitor. However, in case of employment, a short work related trip of

few weeks would not lead to tax residency as highlighted in FC of T v. Pechey12 case.

Pre-arranged employment in excess of six months is considered a significant reason13.

10 ATO, TR98/17, 1998 < https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?Docid=TXR/TR9817/NAT/ATO/00001>

11 Ibid.1

12 FC of T v. Pechey (1975) 5 ATR 322 case

13 Ibid.10

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Personal and Professional Ties – A person having significant personal and

professional ties in Australia is more likely to be termed as a tax resident rather then

one who have more ties with the country of origin rather than Australia. The presence

of ties in Australia typically leads to longevity of stay and hence is significant.

Location of assets – The presence of assets in Australia highlights the commitment of

the taxpayer to stay in Australia for longer period of time. The act of possessing bank

account in Australia or motor vehicles also adds weight to the individual case for

being classified as Australian tax resident.

Social and living arrangement – As per tax ruling TR 98/17, if the taxpayer tends to

live in Australia in a similar manner as in country of origin and have active social

involvement, then the taxpayer is more likely to be considered as an Australian tax

resident.

Residency Status of Martelle – It is apparent that the purpose of Martelle’s visit to Australia

is significant considering she has a minimum stay of six and a half month in regards to her

employment. Further, she has purchased asset in the form of boat coupled with maintaining a

bank account in Australia where her salary is credited. Also, Martelle has a healthy social life

in Australia which is apparent from her behaviour. Hence, it would be appropriate to

conclude that Martelle is a Australian tax resident for the given year.

Tax consequences - In accordance with s. 6-5(2) ITAA 1997, for an Australian tax resident,

the income from both Australian sources as well as foreign sources would be taxable. This is

in sharp contrast with the taxation treatment for foreign tax residents who would be taxed

only on income sources located in Australia14. Additionally, the tax concessions are

comparatively much less for foreign tax residents in comparison to Australian tax residents.

Since Martelle is an Australian tax resident, hence all her income irrespective of the

underlying geography of the source would be taxed in Australia.

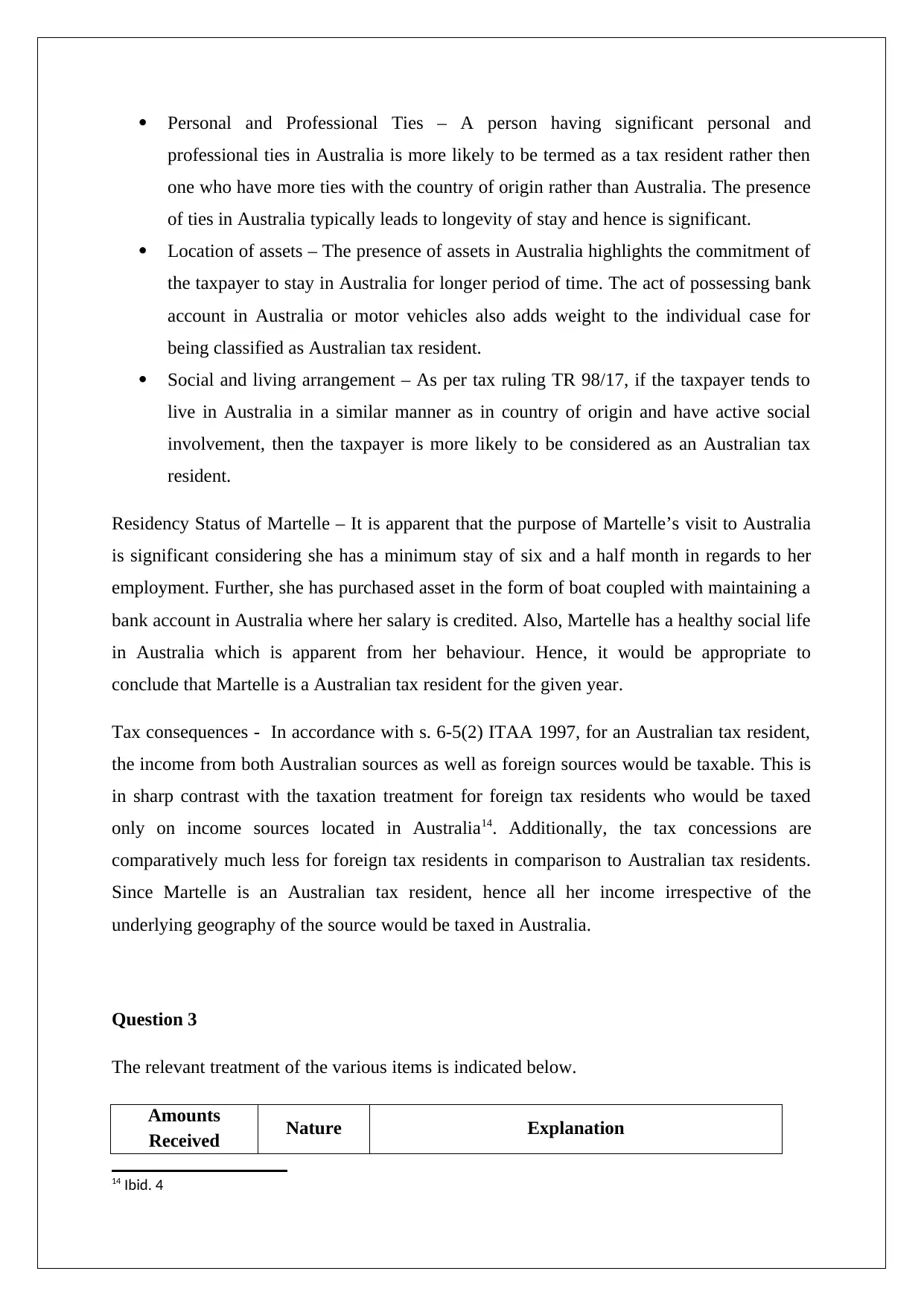

Question 3

The relevant treatment of the various items is indicated below.

Amounts

Received Nature Explanation

14 Ibid. 4

professional ties in Australia is more likely to be termed as a tax resident rather then

one who have more ties with the country of origin rather than Australia. The presence

of ties in Australia typically leads to longevity of stay and hence is significant.

Location of assets – The presence of assets in Australia highlights the commitment of

the taxpayer to stay in Australia for longer period of time. The act of possessing bank

account in Australia or motor vehicles also adds weight to the individual case for

being classified as Australian tax resident.

Social and living arrangement – As per tax ruling TR 98/17, if the taxpayer tends to

live in Australia in a similar manner as in country of origin and have active social

involvement, then the taxpayer is more likely to be considered as an Australian tax

resident.

Residency Status of Martelle – It is apparent that the purpose of Martelle’s visit to Australia

is significant considering she has a minimum stay of six and a half month in regards to her

employment. Further, she has purchased asset in the form of boat coupled with maintaining a

bank account in Australia where her salary is credited. Also, Martelle has a healthy social life

in Australia which is apparent from her behaviour. Hence, it would be appropriate to

conclude that Martelle is a Australian tax resident for the given year.

Tax consequences - In accordance with s. 6-5(2) ITAA 1997, for an Australian tax resident,

the income from both Australian sources as well as foreign sources would be taxable. This is

in sharp contrast with the taxation treatment for foreign tax residents who would be taxed

only on income sources located in Australia14. Additionally, the tax concessions are

comparatively much less for foreign tax residents in comparison to Australian tax residents.

Since Martelle is an Australian tax resident, hence all her income irrespective of the

underlying geography of the source would be taxed in Australia.

Question 3

The relevant treatment of the various items is indicated below.

Amounts

Received Nature Explanation

14 Ibid. 4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

$9,000 per

month in bank

account

Taxable Salary is ordinary income as per s.6(5)15

$425 rent on

bank account Taxable Rent is classified as ordinary income as per s.6(5)

$ 6,500 winnings

designer Taxable

The winnings does not arise on account of luck but

rather is derived from the skill of taxpayer and hence

ordinary income under s.6(5). The price is the result

of the skills possessed as designer by Ellen and not

her luck16. Relevant case law: Kelly v FCT (1985).

$ 10,000

restrictive

covenant

Not Taxable

Proceeds are capital in nature since Ellen would give

up her right to open business within one year.

Relevant case: Higgs v Olivier (1952). Capital

proceeds are not taxable although CGT may be

applicable17

$ 500 spent on

private health

insurance

No

deduction

The expense is private and not related to assessable

income production. Thus no deduction under s. 8-1

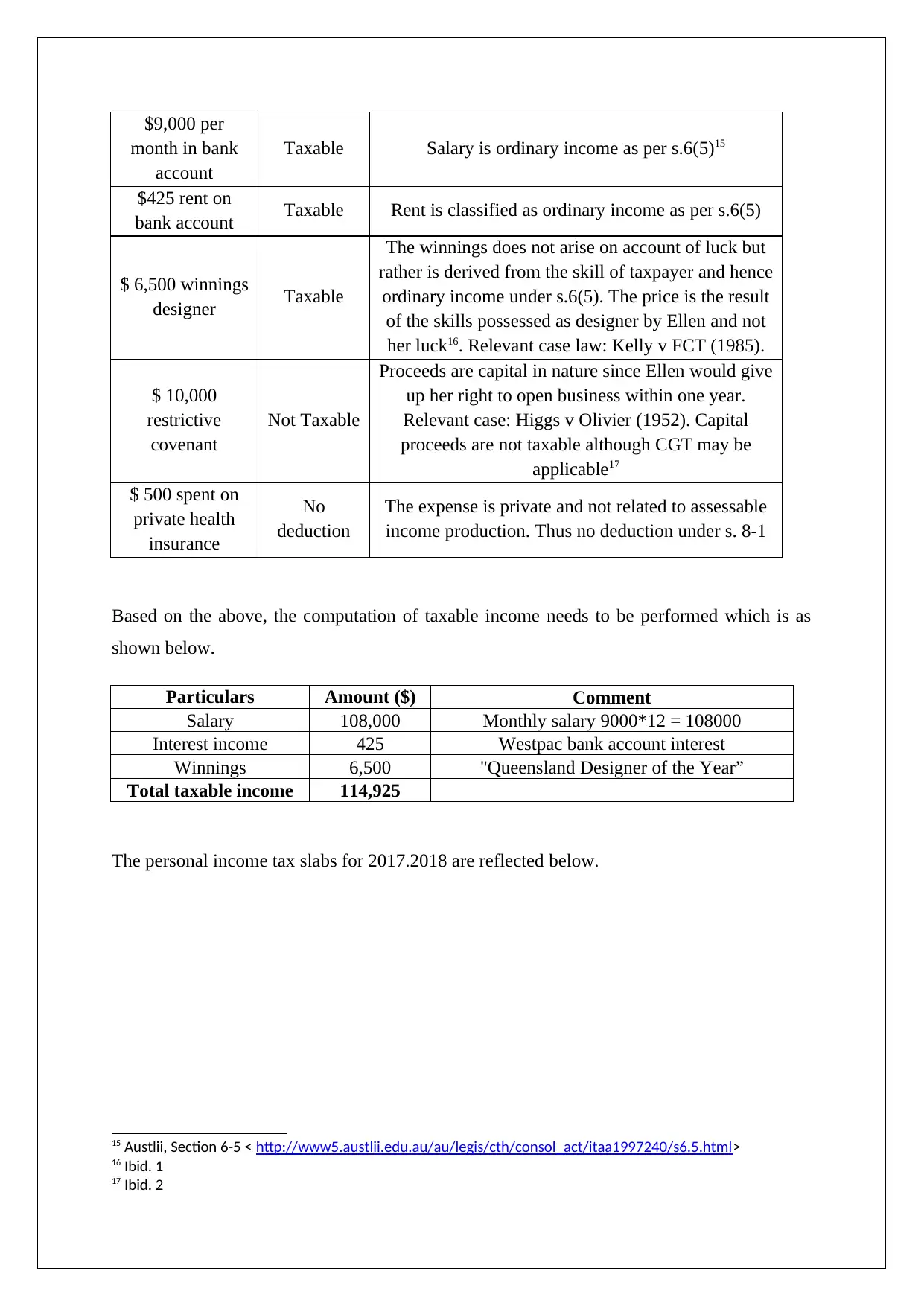

Based on the above, the computation of taxable income needs to be performed which is as

shown below.

Particulars Amount ($) Comment

Salary 108,000 Monthly salary 9000*12 = 108000

Interest income 425 Westpac bank account interest

Winnings 6,500 "Queensland Designer of the Year”

Total taxable income 114,925

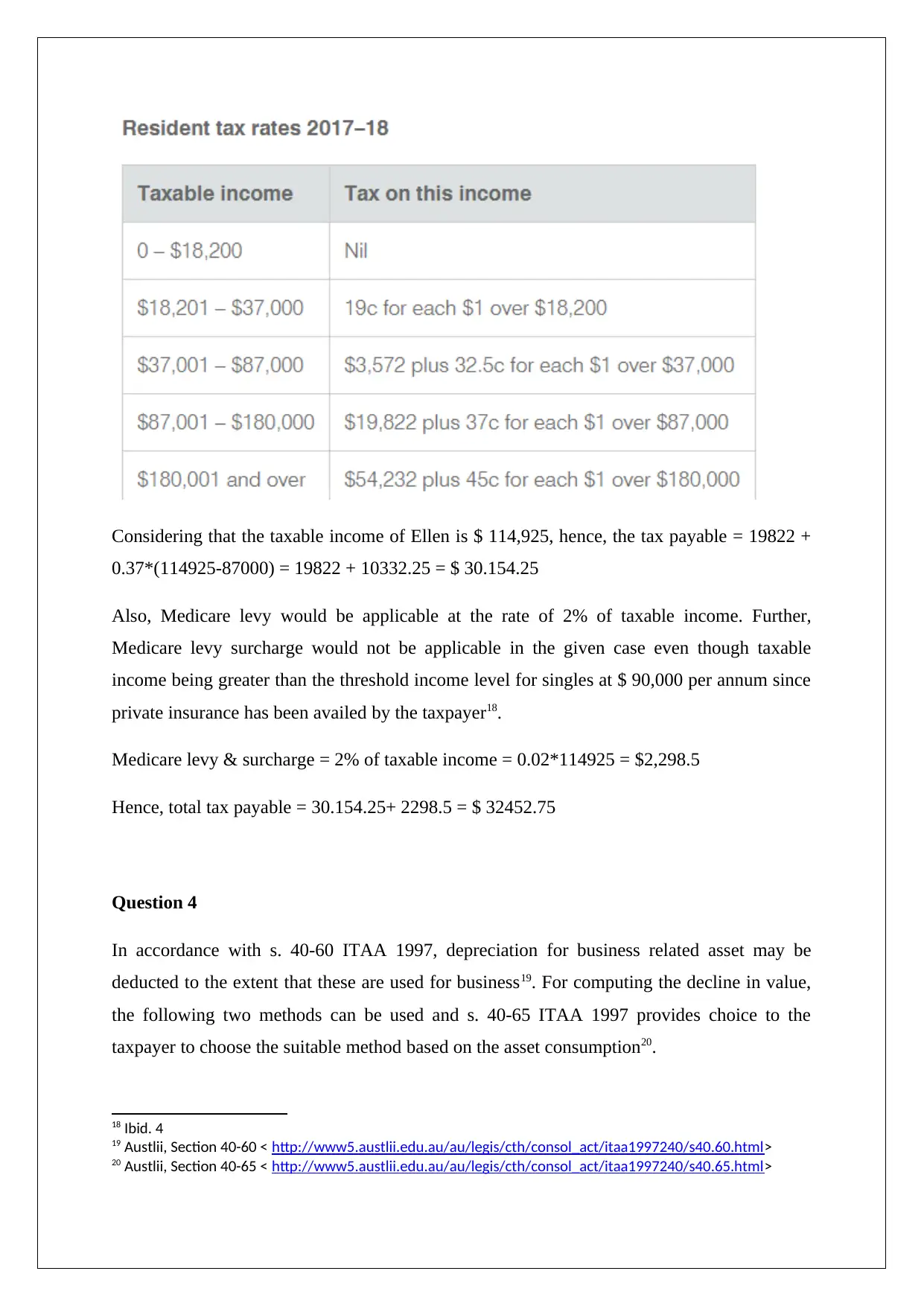

The personal income tax slabs for 2017.2018 are reflected below.

15 Austlii, Section 6-5 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s6.5.html>

16 Ibid. 1

17 Ibid. 2

month in bank

account

Taxable Salary is ordinary income as per s.6(5)15

$425 rent on

bank account Taxable Rent is classified as ordinary income as per s.6(5)

$ 6,500 winnings

designer Taxable

The winnings does not arise on account of luck but

rather is derived from the skill of taxpayer and hence

ordinary income under s.6(5). The price is the result

of the skills possessed as designer by Ellen and not

her luck16. Relevant case law: Kelly v FCT (1985).

$ 10,000

restrictive

covenant

Not Taxable

Proceeds are capital in nature since Ellen would give

up her right to open business within one year.

Relevant case: Higgs v Olivier (1952). Capital

proceeds are not taxable although CGT may be

applicable17

$ 500 spent on

private health

insurance

No

deduction

The expense is private and not related to assessable

income production. Thus no deduction under s. 8-1

Based on the above, the computation of taxable income needs to be performed which is as

shown below.

Particulars Amount ($) Comment

Salary 108,000 Monthly salary 9000*12 = 108000

Interest income 425 Westpac bank account interest

Winnings 6,500 "Queensland Designer of the Year”

Total taxable income 114,925

The personal income tax slabs for 2017.2018 are reflected below.

15 Austlii, Section 6-5 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s6.5.html>

16 Ibid. 1

17 Ibid. 2

Considering that the taxable income of Ellen is $ 114,925, hence, the tax payable = 19822 +

0.37*(114925-87000) = 19822 + 10332.25 = $ 30.154.25

Also, Medicare levy would be applicable at the rate of 2% of taxable income. Further,

Medicare levy surcharge would not be applicable in the given case even though taxable

income being greater than the threshold income level for singles at $ 90,000 per annum since

private insurance has been availed by the taxpayer18.

Medicare levy & surcharge = 2% of taxable income = 0.02*114925 = $2,298.5

Hence, total tax payable = 30.154.25+ 2298.5 = $ 32452.75

Question 4

In accordance with s. 40-60 ITAA 1997, depreciation for business related asset may be

deducted to the extent that these are used for business19. For computing the decline in value,

the following two methods can be used and s. 40-65 ITAA 1997 provides choice to the

taxpayer to choose the suitable method based on the asset consumption20.

18 Ibid. 4

19 Austlii, Section 40-60 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.60.html>

20 Austlii, Section 40-65 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.65.html>

0.37*(114925-87000) = 19822 + 10332.25 = $ 30.154.25

Also, Medicare levy would be applicable at the rate of 2% of taxable income. Further,

Medicare levy surcharge would not be applicable in the given case even though taxable

income being greater than the threshold income level for singles at $ 90,000 per annum since

private insurance has been availed by the taxpayer18.

Medicare levy & surcharge = 2% of taxable income = 0.02*114925 = $2,298.5

Hence, total tax payable = 30.154.25+ 2298.5 = $ 32452.75

Question 4

In accordance with s. 40-60 ITAA 1997, depreciation for business related asset may be

deducted to the extent that these are used for business19. For computing the decline in value,

the following two methods can be used and s. 40-65 ITAA 1997 provides choice to the

taxpayer to choose the suitable method based on the asset consumption20.

18 Ibid. 4

19 Austlii, Section 40-60 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.60.html>

20 Austlii, Section 40-65 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.65.html>

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1) Prime Cost Method – This provides for uniform decline in value of the asset over the

useful life of the asset. The relevant formula is as highlighted below21.

Decline in value = Cost of Asset * (Days Held/365)*(100%/Asset effective life)

2) Diminishing Method – This provides for decreasing decline in value and hence more

decline in value is observed during the initial period as compared to later period. The

relevant formula is as highlighted below22.

Decline in value = Base Value * (Days Held/365)*(200%/Asset effective life)

It is noteworthy that the base value of the asset would change every year after adjusting the

decline in value from the previous year.

Asset 1 – Hair Dryer

Clearly, it is a business asset which is used in hairdressing business and hence, deduction on

account of depreciation is allowed.

Cost of asset = $ 8,000

Effective life = 7 years

Since the asset has been purchased on July1, hence it would be available for the complete

year.

Decline in value (Prime Method) = 8000*(365/365)*(100%/7) = $ 1,142.86

Decline in value (Diminishing Method) = 8000*(365/365)*(200%/7) = $ 2,285.71

Asset 2: Computer Software

In accordance with s. 40-30(1) ITAA 1997, an intangible asset can be a depreciating asset if

the same is highlighted in s. 40-30(2). One of the items mentioned is in-house software which

according to the definition need not be necessarily developed inhouse and can also be

21 Ibid.1

22 Ibid. 4

useful life of the asset. The relevant formula is as highlighted below21.

Decline in value = Cost of Asset * (Days Held/365)*(100%/Asset effective life)

2) Diminishing Method – This provides for decreasing decline in value and hence more

decline in value is observed during the initial period as compared to later period. The

relevant formula is as highlighted below22.

Decline in value = Base Value * (Days Held/365)*(200%/Asset effective life)

It is noteworthy that the base value of the asset would change every year after adjusting the

decline in value from the previous year.

Asset 1 – Hair Dryer

Clearly, it is a business asset which is used in hairdressing business and hence, deduction on

account of depreciation is allowed.

Cost of asset = $ 8,000

Effective life = 7 years

Since the asset has been purchased on July1, hence it would be available for the complete

year.

Decline in value (Prime Method) = 8000*(365/365)*(100%/7) = $ 1,142.86

Decline in value (Diminishing Method) = 8000*(365/365)*(200%/7) = $ 2,285.71

Asset 2: Computer Software

In accordance with s. 40-30(1) ITAA 1997, an intangible asset can be a depreciating asset if

the same is highlighted in s. 40-30(2). One of the items mentioned is in-house software which

according to the definition need not be necessarily developed inhouse and can also be

21 Ibid.1

22 Ibid. 4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

acquired from an outside vendor23. Thus, computer software would be a depreciating asset.

Also, it would be used in business for managing booking and hence it is a business asset

owing to which deductible in nature.

Cost of the asset = $ 295

Effective Life = 3 years

Decline in value (Prime Method) = 295*(365/365)*(100%/3) = $98.33

Decline in value (Diminishing Method) =295*(365/365)*(200%/3) = $98.33

Asset 3: Audi Q5

It is apparent that the asset would fall within the definition of depreciating asset but this does

not have any business use and is essentially a personal asset24. As a result, no deduction

would be available on account of depreciation of this asset. Since no deduction is allowed,

hence no computation of the actual decline in value based on the methods. However, if the

car was used for business purposes, then to the extent of business usage decline in value

would have been deductible.

Question 5

It is imperative to distinguish between a business and hobby as the income from the former

would be taxable while normally any income derived through hobby would be non-taxable.

There are various factors which are considered so as to distinguish between hobby and

business as have been highlighted in tax ruling TR 97/1125. It is imperative to note that the

courts take into consideration the below mentioned factors collectively while making a

judgement as evident from the ruling in Evans v. FC of T26..

1) The presence of intention to profit – If the underlying activity is carried out with the

predominant objective of deriving profit, then the given activity is more likely to be

business. On the contrary, if the underlying activity is more driven by individual

23 Austlii, Section 40-30 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.30.html>

24 Ibid. 2

25 ATO, TR97/11,1997 < https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?docid=TXR/TR9711/NAT/ATO/00001>

26 Evans v. FC of T (1989) 20 ATR 922

Also, it would be used in business for managing booking and hence it is a business asset

owing to which deductible in nature.

Cost of the asset = $ 295

Effective Life = 3 years

Decline in value (Prime Method) = 295*(365/365)*(100%/3) = $98.33

Decline in value (Diminishing Method) =295*(365/365)*(200%/3) = $98.33

Asset 3: Audi Q5

It is apparent that the asset would fall within the definition of depreciating asset but this does

not have any business use and is essentially a personal asset24. As a result, no deduction

would be available on account of depreciation of this asset. Since no deduction is allowed,

hence no computation of the actual decline in value based on the methods. However, if the

car was used for business purposes, then to the extent of business usage decline in value

would have been deductible.

Question 5

It is imperative to distinguish between a business and hobby as the income from the former

would be taxable while normally any income derived through hobby would be non-taxable.

There are various factors which are considered so as to distinguish between hobby and

business as have been highlighted in tax ruling TR 97/1125. It is imperative to note that the

courts take into consideration the below mentioned factors collectively while making a

judgement as evident from the ruling in Evans v. FC of T26..

1) The presence of intention to profit – If the underlying activity is carried out with the

predominant objective of deriving profit, then the given activity is more likely to be

business. On the contrary, if the underlying activity is more driven by individual

23 Austlii, Section 40-30 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.30.html>

24 Ibid. 2

25 ATO, TR97/11,1997 < https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?docid=TXR/TR9711/NAT/ATO/00001>

26 Evans v. FC of T (1989) 20 ATR 922

satisfaction and enjoyment, then it is likely to be a hobby. In case of Julie, her activities

would more likely be business if earning money is the prime reason rather than enjoyment

and satisfaction.

2) The regularity with which the activity is repeated – Typically hobby is done in spare time

whereas a business activity tends to be more regular. Hence, for Julie also, if she does

photography on a regular basis, then it would be more a business in comparison to a

situation when she does photography occasionally only.

3) The amount of time and resources that are invested – Typically, in business there would be

more investment in terms of time, financial resources on taxpayer’s behalf. On the other

hand, in case of hobby the time and resource commitment is significantly lesser. In Julie’s

case, the buying of expensive equipment used by professionals coupled with attending

workshops of photography would indicate that the given activities would be business and

not hobby.

4) The size, scale and manner in which the activity is carried – Businesses are typically done

on a larger scale and are meticulously planned coupled with maintenance of books of

account. In case of hobby, these activities are typically lacking. In Julie’s case also, the

amount of clients that she is serving in a given time frame and the underlying financial

record maintenance of the same would reflect business.

Question 6

The deductibility of the various expenses is discussed in the tabular format shown below.

S.No

. Expenses Nature Explanation

(a) Salary cost $

300,000 Deductible

Under s.8(1) general deduction. Outgoing is

revenue in nature and used for producing

assessable income. Both positive limbs

satisfied27

(b) Salary cost $ 4000

to son Deductible

Under s.8(1) general deduction. Outgoing is

revenue in nature and used for producing

assessable income. Only assumption is that the

payment is on arm's length i.e. market price

has been paid. If not then deduction to the

extent of market rate can be availed under s.

8(1)

27 Austlii, Section 8-1 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s8.1.html>

would more likely be business if earning money is the prime reason rather than enjoyment

and satisfaction.

2) The regularity with which the activity is repeated – Typically hobby is done in spare time

whereas a business activity tends to be more regular. Hence, for Julie also, if she does

photography on a regular basis, then it would be more a business in comparison to a

situation when she does photography occasionally only.

3) The amount of time and resources that are invested – Typically, in business there would be

more investment in terms of time, financial resources on taxpayer’s behalf. On the other

hand, in case of hobby the time and resource commitment is significantly lesser. In Julie’s

case, the buying of expensive equipment used by professionals coupled with attending

workshops of photography would indicate that the given activities would be business and

not hobby.

4) The size, scale and manner in which the activity is carried – Businesses are typically done

on a larger scale and are meticulously planned coupled with maintenance of books of

account. In case of hobby, these activities are typically lacking. In Julie’s case also, the

amount of clients that she is serving in a given time frame and the underlying financial

record maintenance of the same would reflect business.

Question 6

The deductibility of the various expenses is discussed in the tabular format shown below.

S.No

. Expenses Nature Explanation

(a) Salary cost $

300,000 Deductible

Under s.8(1) general deduction. Outgoing is

revenue in nature and used for producing

assessable income. Both positive limbs

satisfied27

(b) Salary cost $ 4000

to son Deductible

Under s.8(1) general deduction. Outgoing is

revenue in nature and used for producing

assessable income. Only assumption is that the

payment is on arm's length i.e. market price

has been paid. If not then deduction to the

extent of market rate can be availed under s.

8(1)

27 Austlii, Section 8-1 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s8.1.html>

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

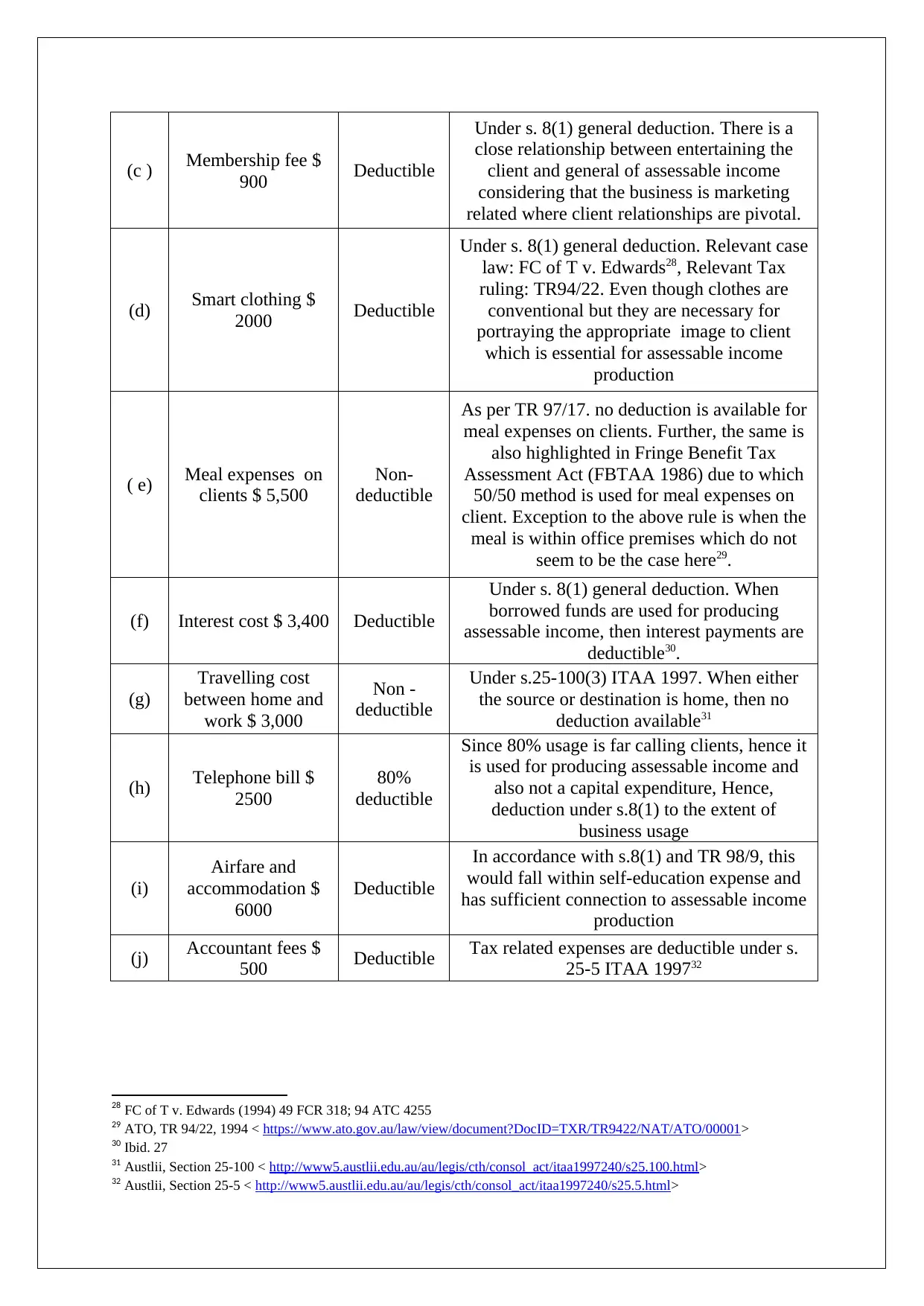

(c ) Membership fee $

900 Deductible

Under s. 8(1) general deduction. There is a

close relationship between entertaining the

client and general of assessable income

considering that the business is marketing

related where client relationships are pivotal.

(d) Smart clothing $

2000 Deductible

Under s. 8(1) general deduction. Relevant case

law: FC of T v. Edwards28, Relevant Tax

ruling: TR94/22. Even though clothes are

conventional but they are necessary for

portraying the appropriate image to client

which is essential for assessable income

production

( e) Meal expenses on

clients $ 5,500

Non-

deductible

As per TR 97/17. no deduction is available for

meal expenses on clients. Further, the same is

also highlighted in Fringe Benefit Tax

Assessment Act (FBTAA 1986) due to which

50/50 method is used for meal expenses on

client. Exception to the above rule is when the

meal is within office premises which do not

seem to be the case here29.

(f) Interest cost $ 3,400 Deductible

Under s. 8(1) general deduction. When

borrowed funds are used for producing

assessable income, then interest payments are

deductible30.

(g)

Travelling cost

between home and

work $ 3,000

Non -

deductible

Under s.25-100(3) ITAA 1997. When either

the source or destination is home, then no

deduction available31

(h) Telephone bill $

2500

80%

deductible

Since 80% usage is far calling clients, hence it

is used for producing assessable income and

also not a capital expenditure, Hence,

deduction under s.8(1) to the extent of

business usage

(i)

Airfare and

accommodation $

6000

Deductible

In accordance with s.8(1) and TR 98/9, this

would fall within self-education expense and

has sufficient connection to assessable income

production

(j) Accountant fees $

500 Deductible Tax related expenses are deductible under s.

25-5 ITAA 199732

28 FC of T v. Edwards (1994) 49 FCR 318; 94 ATC 4255

29 ATO, TR 94/22, 1994 < https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXR/TR9422/NAT/ATO/00001>

30 Ibid. 27

31 Austlii, Section 25-100 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s25.100.html>

32 Austlii, Section 25-5 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s25.5.html>

900 Deductible

Under s. 8(1) general deduction. There is a

close relationship between entertaining the

client and general of assessable income

considering that the business is marketing

related where client relationships are pivotal.

(d) Smart clothing $

2000 Deductible

Under s. 8(1) general deduction. Relevant case

law: FC of T v. Edwards28, Relevant Tax

ruling: TR94/22. Even though clothes are

conventional but they are necessary for

portraying the appropriate image to client

which is essential for assessable income

production

( e) Meal expenses on

clients $ 5,500

Non-

deductible

As per TR 97/17. no deduction is available for

meal expenses on clients. Further, the same is

also highlighted in Fringe Benefit Tax

Assessment Act (FBTAA 1986) due to which

50/50 method is used for meal expenses on

client. Exception to the above rule is when the

meal is within office premises which do not

seem to be the case here29.

(f) Interest cost $ 3,400 Deductible

Under s. 8(1) general deduction. When

borrowed funds are used for producing

assessable income, then interest payments are

deductible30.

(g)

Travelling cost

between home and

work $ 3,000

Non -

deductible

Under s.25-100(3) ITAA 1997. When either

the source or destination is home, then no

deduction available31

(h) Telephone bill $

2500

80%

deductible

Since 80% usage is far calling clients, hence it

is used for producing assessable income and

also not a capital expenditure, Hence,

deduction under s.8(1) to the extent of

business usage

(i)

Airfare and

accommodation $

6000

Deductible

In accordance with s.8(1) and TR 98/9, this

would fall within self-education expense and

has sufficient connection to assessable income

production

(j) Accountant fees $

500 Deductible Tax related expenses are deductible under s.

25-5 ITAA 199732

28 FC of T v. Edwards (1994) 49 FCR 318; 94 ATC 4255

29 ATO, TR 94/22, 1994 < https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXR/TR9422/NAT/ATO/00001>

30 Ibid. 27

31 Austlii, Section 25-100 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s25.100.html>

32 Austlii, Section 25-5 < http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s25.5.html>

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Bibliography

Websites and Books

ATO, TR 94/22, 1994 <

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXR/TR9422/NAT/ATO/00001>

Austlii, Section 25-100 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s25.100.html>

Austlii, Section 25-5 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s25.5.html>

Austlii, Section 8-1 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s8.1.html>

Austlii, Section 40-30 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.30.html>

ATO, TR97/11,1997 <

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?docid=TXR/TR9711/NAT/ATO/00001>

Austlii, Section 40-60 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.60.html>

Austlii, Section 40-65 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.65.html>

Austlii, Section 6-5 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s6.5.html>

ATO, TR98/17, 1998 <

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?Docid=TXR/TR9817/NAT/ATO/00001>

Barkoczy Stephen, Core Tax Legislation and Study Guide 2017 (Oxford University Press

Australia, 2017)

Krever Richard, Australian Taxation Law Cases 2017 (THOMSON LAWBOOK Company,

2017)

Reuters, Thomson, Australian Tax Legislation (THOMSON REUTERS, 2017)

Austlii, Section 15-2 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s15.2.html>

Websites and Books

ATO, TR 94/22, 1994 <

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXR/TR9422/NAT/ATO/00001>

Austlii, Section 25-100 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s25.100.html>

Austlii, Section 25-5 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s25.5.html>

Austlii, Section 8-1 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s8.1.html>

Austlii, Section 40-30 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.30.html>

ATO, TR97/11,1997 <

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?docid=TXR/TR9711/NAT/ATO/00001>

Austlii, Section 40-60 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.60.html>

Austlii, Section 40-65 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s40.65.html>

Austlii, Section 6-5 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s6.5.html>

ATO, TR98/17, 1998 <

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?Docid=TXR/TR9817/NAT/ATO/00001>

Barkoczy Stephen, Core Tax Legislation and Study Guide 2017 (Oxford University Press

Australia, 2017)

Krever Richard, Australian Taxation Law Cases 2017 (THOMSON LAWBOOK Company,

2017)

Reuters, Thomson, Australian Tax Legislation (THOMSON REUTERS, 2017)

Austlii, Section 15-2 <

http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/itaa1997240/s15.2.html>

ATO, TR 2004/15, 2004 <

http://law.ato.gov.au/atolaw/view.htm?docid=TXR/TR200415/NAT/ATO/00001&PiT=2004

1020000001>

ATO, TD2017/4, 2017 <

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXD/TD20174/NAT/ATO/

00001&PiT=99991231235958>

Case laws

FC of T v. Pechey (1975) 5 ATR 322 case

Evans v. FC of T (1989) 20 ATR 922

FC of T v. Edwards (1994) 49 FCR 318; 94 ATC 4255

http://law.ato.gov.au/atolaw/view.htm?docid=TXR/TR200415/NAT/ATO/00001&PiT=2004

1020000001>

ATO, TD2017/4, 2017 <

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXD/TD20174/NAT/ATO/

00001&PiT=99991231235958>

Case laws

FC of T v. Pechey (1975) 5 ATR 322 case

Evans v. FC of T (1989) 20 ATR 922

FC of T v. Edwards (1994) 49 FCR 318; 94 ATC 4255

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.