Taxation Law: Fringe Benefits, Capital Gains Tax, and Assets

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/31

|9

|2040

|205

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This taxation law assignment delves into the tax implications of providing a car to an employee, classifying it as a car fringe benefit under the FBTAA 1986 and calculating the taxable amount using both statutory and cost basis formulas. The assignment then addresses capital gains tax (CGT) concerning various assets, including a house, painting, luxury yacht, and shares. It examines CGT event H1 related to forfeited deposits, the application of CGT to collectables and personal use assets, and the treatment of capital losses, providing recommendations for tax planning, particularly regarding superannuation contributions. The analysis references relevant sections of the ITA Act 97 and FBTAA 1986, providing a comprehensive overview of the tax consequences of the asset transactions.

Taxation Law

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table of Contents

Answer to question 1:...................................................................................................3

Answer to question 2:...................................................................................................5

Answer to A:.................................................................................................................6

Answer to B:..............................................................................................................7

Answer to C:..............................................................................................................8

References:..................................................................................................................9

Answer to question 1:...................................................................................................3

Answer to question 2:...................................................................................................5

Answer to A:.................................................................................................................6

Answer to B:..............................................................................................................7

Answer to C:..............................................................................................................8

References:..................................................................................................................9

Answer to question 1:

Issues:

The principle issue that will be discussed in the current case will be the tax

consequences of providing the car to the employee.

Rule:

The fringe benefit is regarded as the regime that principally imposes tax on

the wide range of benefits that is given to the employee by the employer. The

provision of the fringe benefit tax is given in the “FBTAA 1986” (Barkoczy 2016). As

denoted in the “s136(1), FBTAA 1986” a fringe benefit happens when the benefit is

given to the employee during the year by the employer in relation to the employment

of the employee. The definition fringe benefit explains that there should be a pivotal

relation with the employment of the employee for the fringe benefit to happen. The

benefit must be provided to the employee by the employer, associated parties and

the third party arranger under the arrangement of the employer.

The court of law in “J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)”

held that there must be a material and sufficient relationship between the benefit and

the employment of the employee (Woellner et al. 2016). Under the “s7 (1), FBTAA

1986” a car fringe benefit happens when the car is given to the employee by the

employer for the purpose of employee’s private usage. “Sec 136 (1)”, denotes that

the private use of the car implies that car is not exclusively in the course of

generating assessable income.

To compute the car fringe benefits there are two important formulae that is

existent. This includes the statutory formula given under the “s9, of the FBTAA

1986” and the cost basis formula given in the “s10, FBTAA 1986”. The statutory

formula is applied in general cases however a cost basis formula is only applied

when the employer decides to make use of the cost basis (Cooper 2017). The

statutory formula mainly involves the cost base of the car less the employee

contributing multiplied by the statutory rate. On the other the cost basis generally

involves the log book records and the odometer records that are maintained by the

taxpayer. One must denote that the fringe benefit tax is paid by the employer and not

employee.

Application:

The case facts suggest that Spiceco Pty Ltd provided its employee Lucinda

with the car that was exclusively for the private of the employee. By referring to the

“sec 7 (1), FBTAA 1986” it can be stated a car fringe benefit has occurred for the

employer Spiceco Pty Ltd (Braithwaite 2017). Denoting the legislative reference of

“sec 136 (1)”, the car was provided to Lucinda by Spiceco Pty Ltd during the year in

relation to the employment of the employee.

By referring to the explanation that is made in the case of “J & G Knowles &

Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” there was a material and sufficient relationship

between the benefit and the employment of the Lucinda. The car was given to

Lucinda exclusively for making the private use (Nolan 2018). To compute the car

fringe benefit for Spiceco Pty Ltd, statutory formula has been considered under that

is given in “s9, FBTAA 1986”.

Issues:

The principle issue that will be discussed in the current case will be the tax

consequences of providing the car to the employee.

Rule:

The fringe benefit is regarded as the regime that principally imposes tax on

the wide range of benefits that is given to the employee by the employer. The

provision of the fringe benefit tax is given in the “FBTAA 1986” (Barkoczy 2016). As

denoted in the “s136(1), FBTAA 1986” a fringe benefit happens when the benefit is

given to the employee during the year by the employer in relation to the employment

of the employee. The definition fringe benefit explains that there should be a pivotal

relation with the employment of the employee for the fringe benefit to happen. The

benefit must be provided to the employee by the employer, associated parties and

the third party arranger under the arrangement of the employer.

The court of law in “J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)”

held that there must be a material and sufficient relationship between the benefit and

the employment of the employee (Woellner et al. 2016). Under the “s7 (1), FBTAA

1986” a car fringe benefit happens when the car is given to the employee by the

employer for the purpose of employee’s private usage. “Sec 136 (1)”, denotes that

the private use of the car implies that car is not exclusively in the course of

generating assessable income.

To compute the car fringe benefits there are two important formulae that is

existent. This includes the statutory formula given under the “s9, of the FBTAA

1986” and the cost basis formula given in the “s10, FBTAA 1986”. The statutory

formula is applied in general cases however a cost basis formula is only applied

when the employer decides to make use of the cost basis (Cooper 2017). The

statutory formula mainly involves the cost base of the car less the employee

contributing multiplied by the statutory rate. On the other the cost basis generally

involves the log book records and the odometer records that are maintained by the

taxpayer. One must denote that the fringe benefit tax is paid by the employer and not

employee.

Application:

The case facts suggest that Spiceco Pty Ltd provided its employee Lucinda

with the car that was exclusively for the private of the employee. By referring to the

“sec 7 (1), FBTAA 1986” it can be stated a car fringe benefit has occurred for the

employer Spiceco Pty Ltd (Braithwaite 2017). Denoting the legislative reference of

“sec 136 (1)”, the car was provided to Lucinda by Spiceco Pty Ltd during the year in

relation to the employment of the employee.

By referring to the explanation that is made in the case of “J & G Knowles &

Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” there was a material and sufficient relationship

between the benefit and the employment of the Lucinda. The car was given to

Lucinda exclusively for making the private use (Nolan 2018). To compute the car

fringe benefit for Spiceco Pty Ltd, statutory formula has been considered under that

is given in “s9, FBTAA 1986”.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

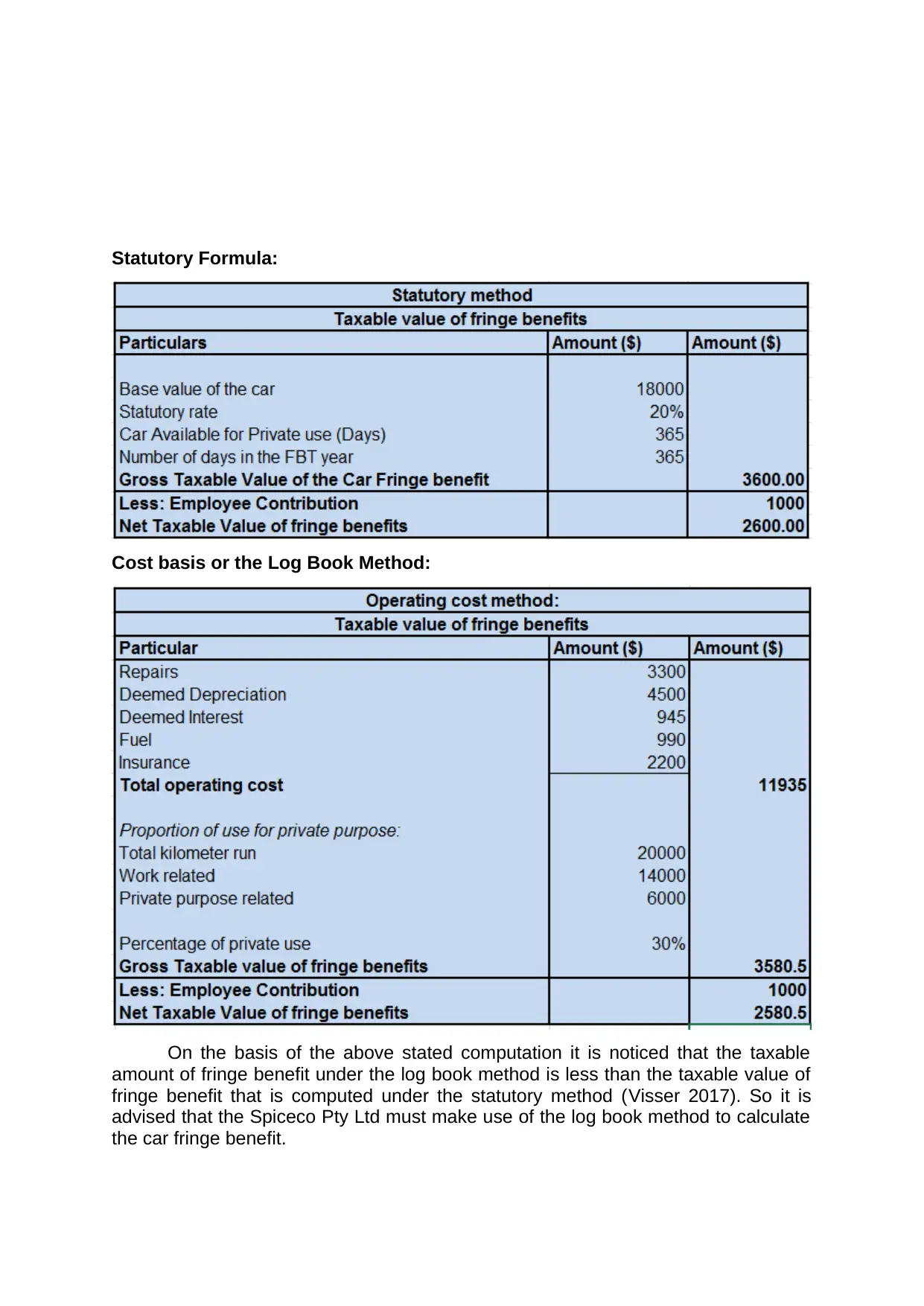

Statutory Formula:

Cost basis or the Log Book Method:

On the basis of the above stated computation it is noticed that the taxable

amount of fringe benefit under the log book method is less than the taxable value of

fringe benefit that is computed under the statutory method (Visser 2017). So it is

advised that the Spiceco Pty Ltd must make use of the log book method to calculate

the car fringe benefit.

Cost basis or the Log Book Method:

On the basis of the above stated computation it is noticed that the taxable

amount of fringe benefit under the log book method is less than the taxable value of

fringe benefit that is computed under the statutory method (Visser 2017). So it is

advised that the Spiceco Pty Ltd must make use of the log book method to calculate

the car fringe benefit.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

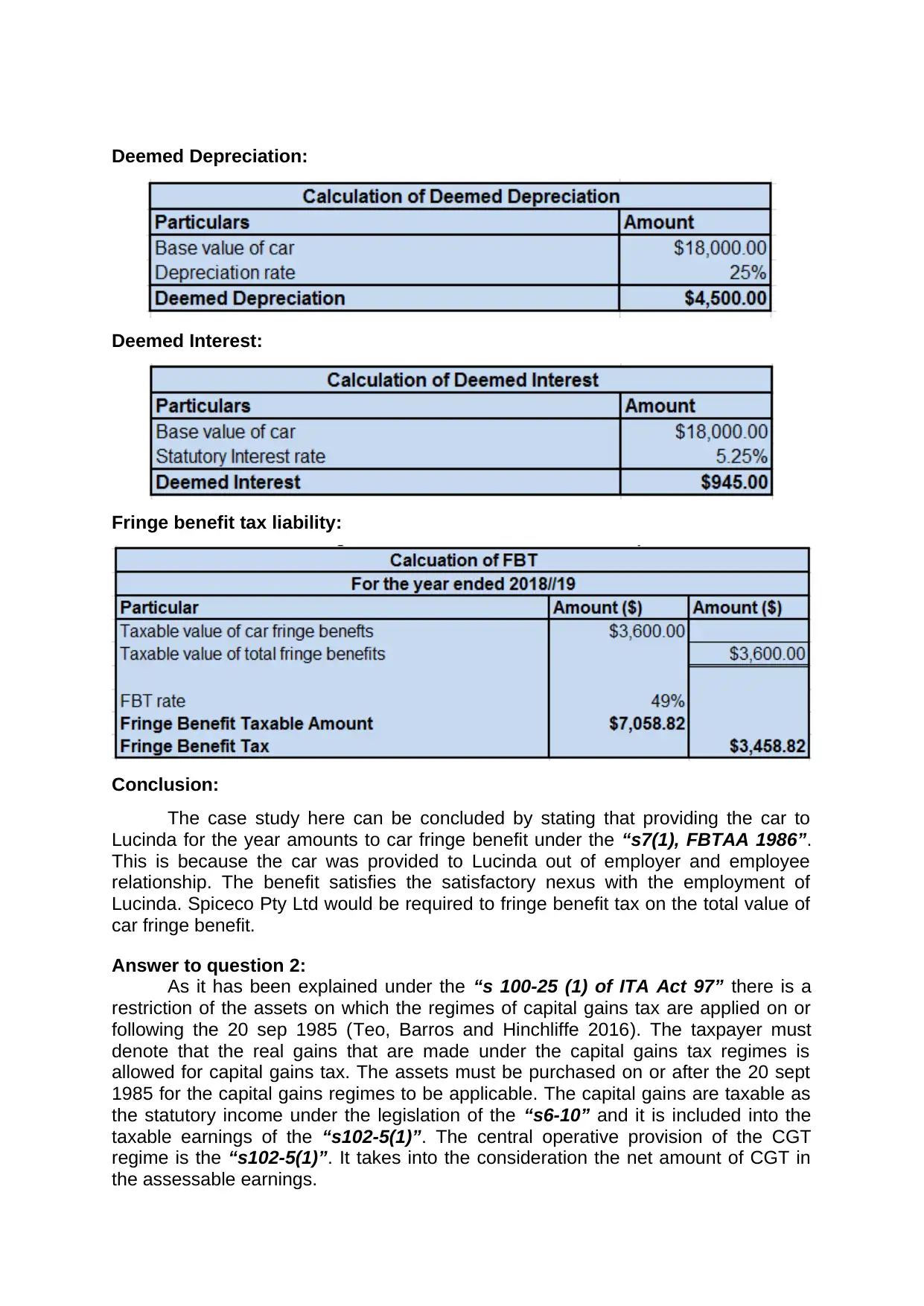

Deemed Depreciation:

Deemed Interest:

Fringe benefit tax liability:

Conclusion:

The case study here can be concluded by stating that providing the car to

Lucinda for the year amounts to car fringe benefit under the “s7(1), FBTAA 1986”.

This is because the car was provided to Lucinda out of employer and employee

relationship. The benefit satisfies the satisfactory nexus with the employment of

Lucinda. Spiceco Pty Ltd would be required to fringe benefit tax on the total value of

car fringe benefit.

Answer to question 2:

As it has been explained under the “s 100-25 (1) of ITA Act 97” there is a

restriction of the assets on which the regimes of capital gains tax are applied on or

following the 20 sep 1985 (Teo, Barros and Hinchliffe 2016). The taxpayer must

denote that the real gains that are made under the capital gains tax regimes is

allowed for capital gains tax. The assets must be purchased on or after the 20 sept

1985 for the capital gains regimes to be applicable. The capital gains are taxable as

the statutory income under the legislation of the “s6-10” and it is included into the

taxable earnings of the “s102-5(1)”. The central operative provision of the CGT

regime is the “s102-5(1)”. It takes into the consideration the net amount of CGT in

the assessable earnings.

Deemed Interest:

Fringe benefit tax liability:

Conclusion:

The case study here can be concluded by stating that providing the car to

Lucinda for the year amounts to car fringe benefit under the “s7(1), FBTAA 1986”.

This is because the car was provided to Lucinda out of employer and employee

relationship. The benefit satisfies the satisfactory nexus with the employment of

Lucinda. Spiceco Pty Ltd would be required to fringe benefit tax on the total value of

car fringe benefit.

Answer to question 2:

As it has been explained under the “s 100-25 (1) of ITA Act 97” there is a

restriction of the assets on which the regimes of capital gains tax are applied on or

following the 20 sep 1985 (Teo, Barros and Hinchliffe 2016). The taxpayer must

denote that the real gains that are made under the capital gains tax regimes is

allowed for capital gains tax. The assets must be purchased on or after the 20 sept

1985 for the capital gains regimes to be applicable. The capital gains are taxable as

the statutory income under the legislation of the “s6-10” and it is included into the

taxable earnings of the “s102-5(1)”. The central operative provision of the CGT

regime is the “s102-5(1)”. It takes into the consideration the net amount of CGT in

the assessable earnings.

Answer to A:

As understood from the case information of Daniel he is presently in aging in

late 50s and he is planning for his retirement. He has decided to make a contribution

for the super fund prior to the end of this year. Presently, Daniel has different variety

of asset that worth’s around $1 million and he is looking forward to make further

contribution in to his superannuation fund. As the part of his retirement plan there are

some of the assets that are sold by Daniel and the capital gains tax consequences

for the asset is given below;

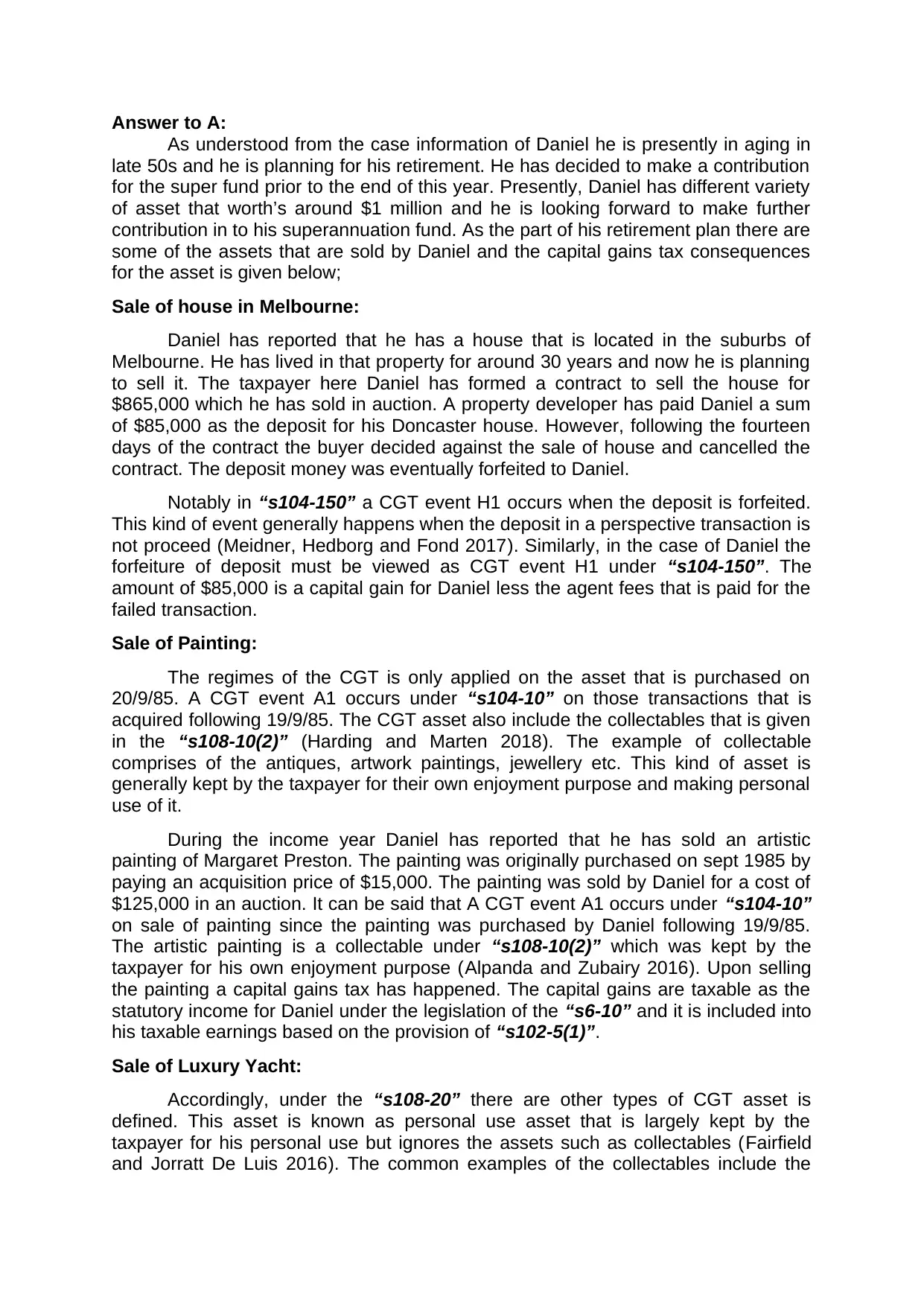

Sale of house in Melbourne:

Daniel has reported that he has a house that is located in the suburbs of

Melbourne. He has lived in that property for around 30 years and now he is planning

to sell it. The taxpayer here Daniel has formed a contract to sell the house for

$865,000 which he has sold in auction. A property developer has paid Daniel a sum

of $85,000 as the deposit for his Doncaster house. However, following the fourteen

days of the contract the buyer decided against the sale of house and cancelled the

contract. The deposit money was eventually forfeited to Daniel.

Notably in “s104-150” a CGT event H1 occurs when the deposit is forfeited.

This kind of event generally happens when the deposit in a perspective transaction is

not proceed (Meidner, Hedborg and Fond 2017). Similarly, in the case of Daniel the

forfeiture of deposit must be viewed as CGT event H1 under “s104-150”. The

amount of $85,000 is a capital gain for Daniel less the agent fees that is paid for the

failed transaction.

Sale of Painting:

The regimes of the CGT is only applied on the asset that is purchased on

20/9/85. A CGT event A1 occurs under “s104-10” on those transactions that is

acquired following 19/9/85. The CGT asset also include the collectables that is given

in the “s108-10(2)” (Harding and Marten 2018). The example of collectable

comprises of the antiques, artwork paintings, jewellery etc. This kind of asset is

generally kept by the taxpayer for their own enjoyment purpose and making personal

use of it.

During the income year Daniel has reported that he has sold an artistic

painting of Margaret Preston. The painting was originally purchased on sept 1985 by

paying an acquisition price of $15,000. The painting was sold by Daniel for a cost of

$125,000 in an auction. It can be said that A CGT event A1 occurs under “s104-10”

on sale of painting since the painting was purchased by Daniel following 19/9/85.

The artistic painting is a collectable under “s108-10(2)” which was kept by the

taxpayer for his own enjoyment purpose (Alpanda and Zubairy 2016). Upon selling

the painting a capital gains tax has happened. The capital gains are taxable as the

statutory income for Daniel under the legislation of the “s6-10” and it is included into

his taxable earnings based on the provision of “s102-5(1)”.

Sale of Luxury Yacht:

Accordingly, under the “s108-20” there are other types of CGT asset is

defined. This asset is known as personal use asset that is largely kept by the

taxpayer for his personal use but ignores the assets such as collectables (Fairfield

and Jorratt De Luis 2016). The common examples of the collectables include the

As understood from the case information of Daniel he is presently in aging in

late 50s and he is planning for his retirement. He has decided to make a contribution

for the super fund prior to the end of this year. Presently, Daniel has different variety

of asset that worth’s around $1 million and he is looking forward to make further

contribution in to his superannuation fund. As the part of his retirement plan there are

some of the assets that are sold by Daniel and the capital gains tax consequences

for the asset is given below;

Sale of house in Melbourne:

Daniel has reported that he has a house that is located in the suburbs of

Melbourne. He has lived in that property for around 30 years and now he is planning

to sell it. The taxpayer here Daniel has formed a contract to sell the house for

$865,000 which he has sold in auction. A property developer has paid Daniel a sum

of $85,000 as the deposit for his Doncaster house. However, following the fourteen

days of the contract the buyer decided against the sale of house and cancelled the

contract. The deposit money was eventually forfeited to Daniel.

Notably in “s104-150” a CGT event H1 occurs when the deposit is forfeited.

This kind of event generally happens when the deposit in a perspective transaction is

not proceed (Meidner, Hedborg and Fond 2017). Similarly, in the case of Daniel the

forfeiture of deposit must be viewed as CGT event H1 under “s104-150”. The

amount of $85,000 is a capital gain for Daniel less the agent fees that is paid for the

failed transaction.

Sale of Painting:

The regimes of the CGT is only applied on the asset that is purchased on

20/9/85. A CGT event A1 occurs under “s104-10” on those transactions that is

acquired following 19/9/85. The CGT asset also include the collectables that is given

in the “s108-10(2)” (Harding and Marten 2018). The example of collectable

comprises of the antiques, artwork paintings, jewellery etc. This kind of asset is

generally kept by the taxpayer for their own enjoyment purpose and making personal

use of it.

During the income year Daniel has reported that he has sold an artistic

painting of Margaret Preston. The painting was originally purchased on sept 1985 by

paying an acquisition price of $15,000. The painting was sold by Daniel for a cost of

$125,000 in an auction. It can be said that A CGT event A1 occurs under “s104-10”

on sale of painting since the painting was purchased by Daniel following 19/9/85.

The artistic painting is a collectable under “s108-10(2)” which was kept by the

taxpayer for his own enjoyment purpose (Alpanda and Zubairy 2016). Upon selling

the painting a capital gains tax has happened. The capital gains are taxable as the

statutory income for Daniel under the legislation of the “s6-10” and it is included into

his taxable earnings based on the provision of “s102-5(1)”.

Sale of Luxury Yacht:

Accordingly, under the “s108-20” there are other types of CGT asset is

defined. This asset is known as personal use asset that is largely kept by the

taxpayer for his personal use but ignores the assets such as collectables (Fairfield

and Jorratt De Luis 2016). The common examples of the collectables include the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

boats, racehorse, furniture vehicles etc. There are some noteworthy rules regarding

capital gains or loss made from the personal use asset. This includes that the capital

loss that is made from the personal use asset must be simply disregarded under the

provision “s108-20(1)”.

As Daniel wants fund for his retirement, he has a luxury yacht that he has sold

it for $60,000. The yacht was actually purchased by Daniel for $110,000. The luxury

yacht under the provision of “s108-20” has been categorized as the personal use

asset. As disposal yacht has led to capital loss for Daniel, more importantly denoting

the provision of “s108-20(1)” the capital loss that is made from the personal use

asset must be simply disregarded by Daniel.

Sale of Shares:

The CGT assets also includes the shares in the units or a public listed

company (Auerbach and Hassett 2015). Evidently, Daniel has the shares in the

mining company named BHP which has he has sold for 80,000. In addition to this he

has paid the stamp duty on the purchase of shares and brokerage fee while selling

the shares. The stamp duty forms the part of shares cost base while the brokerage

fees is cost of selling the shares which is subtracted from the total sales. Daniel upon

selling the BHP shares made capital gains. However, he also reports a carry forward

capital loss of $10,000 from the AZJ shares in the current year of tax. There was no

other capital loss for 2017 except the AZJ shares. It must be noted that Daniel can

reduce his capital loss from shares by offset from the capital gains made from BHP

shares. While the rest of the capital loss must be carry forward to next year by Daniel

which is only allowed to offset from future capital gains that will be earned from

shares.

capital gains or loss made from the personal use asset. This includes that the capital

loss that is made from the personal use asset must be simply disregarded under the

provision “s108-20(1)”.

As Daniel wants fund for his retirement, he has a luxury yacht that he has sold

it for $60,000. The yacht was actually purchased by Daniel for $110,000. The luxury

yacht under the provision of “s108-20” has been categorized as the personal use

asset. As disposal yacht has led to capital loss for Daniel, more importantly denoting

the provision of “s108-20(1)” the capital loss that is made from the personal use

asset must be simply disregarded by Daniel.

Sale of Shares:

The CGT assets also includes the shares in the units or a public listed

company (Auerbach and Hassett 2015). Evidently, Daniel has the shares in the

mining company named BHP which has he has sold for 80,000. In addition to this he

has paid the stamp duty on the purchase of shares and brokerage fee while selling

the shares. The stamp duty forms the part of shares cost base while the brokerage

fees is cost of selling the shares which is subtracted from the total sales. Daniel upon

selling the BHP shares made capital gains. However, he also reports a carry forward

capital loss of $10,000 from the AZJ shares in the current year of tax. There was no

other capital loss for 2017 except the AZJ shares. It must be noted that Daniel can

reduce his capital loss from shares by offset from the capital gains made from BHP

shares. While the rest of the capital loss must be carry forward to next year by Daniel

which is only allowed to offset from future capital gains that will be earned from

shares.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Answer to B:

From the assets that were sold by Daniel for the year capital gains were only

made from the forfeited deposit from the house that was located in suburbs of

Melbourne and capital gains from the artistic painting being a post-CGT asset. It is

recommended that in a bid to plan for his retirement the capital gains that is made by

Daniel must be invested in his superannuation fund.

Answer to C:

Daniel has reported a loss from the luxury yacht sale and capital loss from the

shares AZJ shares. It is recommended that the capital loss must be carry forward to

next year by Daniel which is only allowed to offset from future capital gains that will

be earned from shares.

From the assets that were sold by Daniel for the year capital gains were only

made from the forfeited deposit from the house that was located in suburbs of

Melbourne and capital gains from the artistic painting being a post-CGT asset. It is

recommended that in a bid to plan for his retirement the capital gains that is made by

Daniel must be invested in his superannuation fund.

Answer to C:

Daniel has reported a loss from the luxury yacht sale and capital loss from the

shares AZJ shares. It is recommended that the capital loss must be carry forward to

next year by Daniel which is only allowed to offset from future capital gains that will

be earned from shares.

References:

Alpanda, S. and Zubairy, S., 2016. Housing and tax policy. Journal of Money, Credit

and Banking, 48(2-3), pp.485-512.

Auerbach, A.J. and Hassett, K., 2015. Capital taxation in the twenty-first

century. American Economic Review, 105(5), pp.38-42.

Barkoczy, S., 2016. Foundations of taxation law 2016. OUP Catalogue.

Braithwaite, V., 2017. Taxing democracy: Understanding tax avoidance and evasion.

Routledge.

Cooper, R., 2017. How to tax cellphones in the workplace. Tax

Professional, 2017(29), pp.22-23.

Fairfield, T. and Jorratt De Luis, M., 2016. Top Income Shares, Business Profits, and

Effective Tax Rates in Contemporary C hile. Review of Income and Wealth, 62,

pp.S120-S144.

Harding, M. and Marten, M., 2018. Statutory tax rates on dividends, interest and

capital gains.

Meidner, R., Hedborg, A. and Fond, G., 2017. Employee investment funds: An

approach to collective capital formation. Routledge.

Nolan, M., 2018. Income Tax and Transfer Policy Changes in Australia: 1988-2013.

Teo, E., Barros, C. and Hinchliffe, S.A., 2016. Clash of the Deeming Provisions: Pre-

Capital Gains Tax Concessions, Tax Consolidation and Policy in the Federal Court.

Visser, A., 2017. Tax and employee transport. Tax Breaks Newsletter, 2017(376),

pp.8-8.

Woellner, R., Barkoczy, S., Murphy, S., Evans, C. and Pinto, D., 2016. Australian

Taxation Law 2016. OUP Catalogue.

Alpanda, S. and Zubairy, S., 2016. Housing and tax policy. Journal of Money, Credit

and Banking, 48(2-3), pp.485-512.

Auerbach, A.J. and Hassett, K., 2015. Capital taxation in the twenty-first

century. American Economic Review, 105(5), pp.38-42.

Barkoczy, S., 2016. Foundations of taxation law 2016. OUP Catalogue.

Braithwaite, V., 2017. Taxing democracy: Understanding tax avoidance and evasion.

Routledge.

Cooper, R., 2017. How to tax cellphones in the workplace. Tax

Professional, 2017(29), pp.22-23.

Fairfield, T. and Jorratt De Luis, M., 2016. Top Income Shares, Business Profits, and

Effective Tax Rates in Contemporary C hile. Review of Income and Wealth, 62,

pp.S120-S144.

Harding, M. and Marten, M., 2018. Statutory tax rates on dividends, interest and

capital gains.

Meidner, R., Hedborg, A. and Fond, G., 2017. Employee investment funds: An

approach to collective capital formation. Routledge.

Nolan, M., 2018. Income Tax and Transfer Policy Changes in Australia: 1988-2013.

Teo, E., Barros, C. and Hinchliffe, S.A., 2016. Clash of the Deeming Provisions: Pre-

Capital Gains Tax Concessions, Tax Consolidation and Policy in the Federal Court.

Visser, A., 2017. Tax and employee transport. Tax Breaks Newsletter, 2017(376),

pp.8-8.

Woellner, R., Barkoczy, S., Murphy, S., Evans, C. and Pinto, D., 2016. Australian

Taxation Law 2016. OUP Catalogue.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.