HA3042 Taxation Law: Analysis of Fringe Benefits and Capital Gains

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/31

|9

|2346

|144

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a detailed analysis of taxation law, focusing on fringe benefits and capital gains. It examines whether a car provided to an employee constitutes a fringe benefit under s7(1) of FBTAA 1986, discussing the differences between fringe benefit tax and income tax, and the conditions under which a benefit qualifies as a fringe benefit, referencing the J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000) case. The report applies both the statutory formula and the cost basis formula to calculate the fringe benefit tax for Spiceco Pty Ltd, advising on the most beneficial method. Furthermore, it analyzes Daniel's capital gains tax implications from the sale of a Doncaster house, an artistic painting, a luxury yacht, and BHP shares, referencing relevant sections of the ITAA 1997, including CGT event H1, CGT event A1, and the treatment of personal use assets. The report also addresses the carry forward loss from AZJ shares and its potential offset against future gains. Desklib provides access to similar solved assignments and study resources for students.

Running head: TAXATION LAW

Taxation Law

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Taxation Law

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1TAXATION LAW

Table of Contents

Answer to question 1:...................................................................................................2

Answer to question 2:...................................................................................................5

Answer to A:..............................................................................................................5

Answer to B:..............................................................................................................7

Answer to C:..............................................................................................................7

References:..................................................................................................................8

Table of Contents

Answer to question 1:...................................................................................................2

Answer to question 2:...................................................................................................5

Answer to A:..............................................................................................................5

Answer to B:..............................................................................................................7

Answer to C:..............................................................................................................7

References:..................................................................................................................8

2TAXATION LAW

Answer to question 1:

Issue:

Is the car that is given to the employee will be considered as fringe benefit for

the employer under the legislative provision of “s7 (1), FBTAA 1986”.

Rule:

The fringe benefit tax is regarded as the regime that necessarily imposes

taxes on the wide variety of benefits that is given to the employee by the employer.

The fringe benefit is considered useful because it overcomes the inadequacies that

are prevalent in the present regimes of the income tax (Royalty 2014). The fringe

benefit tax regimes impose taxes on the non-cash benefits that cannot be converted

into cash. The taxes are also levied on the benefits that are provided to the

employees associates such as the spouse. The most important difference between

the fringe benefit tax and the income tax is that fringe benefit tax is generally levied

on the employer. The employees are not subjected to provision of fringe benefits.

The fringe benefit tax year commences from the 1st April and ends in 31st march

which is treated as the year of tax.

The most important thing to the application of the fringe benefit tax is that

there must be a benefit given to the employee under the “sec 136 (1), FBTAA

1986”. A fringe benefit is existent when the benefit is given during the year of

taxation to the employee by the employer or by the third party arranger in

accordance with the employment of the employee (Woodbury and Hamermesh

2015). The benefit does not take into the consideration the salaries and wages.

“Sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” explains the benefit that comprises of the rights,

privilege, services or facility under the arrangement in respect of the performance of

the work. The taxpayers must denote that the definition of the fringe benefit is

considered very wide and would most likely to capture the benefits including the non-

monetary benefits.

In order to apply the fringe benefit, provision the benefits needs to be provided

by the employer to the employee or the associate by the third party associate of the

employee or the third party arranger. The definition of the fringe benefit exclusively

explains that there should be an instrumental link between the benefit that is given to

the employee and the nexus with the employee’s employment (Scott, Berger and

Black 2014). The “sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” explains that in order to qualify as the

benefit, the benefit should be given by reason of or by virtue of the employment of

the employee either directly or indirectly of the employment.

The court has stated that there must be an adequate nexus and also the main

subject of the judicial consideration. The illustration of case law can be referred to

qualify the benefit under the judicial consideration. The law court in “J & G Knowles

& Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” held that in order to qualify as fringe benefit

there should be a sufficient and material relationship between the employment of the

employee and employer (Woodbury and Huang 2014). The provision of fringe benefit

does not take into the account the salaries or wages, superannuation contribution

under “sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986”.

A car fringe benefit originates under “s7 (1), FBTAA 1986” when it is noticed

that the employer has provided the employee with the car for the private usage of it.

Answer to question 1:

Issue:

Is the car that is given to the employee will be considered as fringe benefit for

the employer under the legislative provision of “s7 (1), FBTAA 1986”.

Rule:

The fringe benefit tax is regarded as the regime that necessarily imposes

taxes on the wide variety of benefits that is given to the employee by the employer.

The fringe benefit is considered useful because it overcomes the inadequacies that

are prevalent in the present regimes of the income tax (Royalty 2014). The fringe

benefit tax regimes impose taxes on the non-cash benefits that cannot be converted

into cash. The taxes are also levied on the benefits that are provided to the

employees associates such as the spouse. The most important difference between

the fringe benefit tax and the income tax is that fringe benefit tax is generally levied

on the employer. The employees are not subjected to provision of fringe benefits.

The fringe benefit tax year commences from the 1st April and ends in 31st march

which is treated as the year of tax.

The most important thing to the application of the fringe benefit tax is that

there must be a benefit given to the employee under the “sec 136 (1), FBTAA

1986”. A fringe benefit is existent when the benefit is given during the year of

taxation to the employee by the employer or by the third party arranger in

accordance with the employment of the employee (Woodbury and Hamermesh

2015). The benefit does not take into the consideration the salaries and wages.

“Sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” explains the benefit that comprises of the rights,

privilege, services or facility under the arrangement in respect of the performance of

the work. The taxpayers must denote that the definition of the fringe benefit is

considered very wide and would most likely to capture the benefits including the non-

monetary benefits.

In order to apply the fringe benefit, provision the benefits needs to be provided

by the employer to the employee or the associate by the third party associate of the

employee or the third party arranger. The definition of the fringe benefit exclusively

explains that there should be an instrumental link between the benefit that is given to

the employee and the nexus with the employee’s employment (Scott, Berger and

Black 2014). The “sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” explains that in order to qualify as the

benefit, the benefit should be given by reason of or by virtue of the employment of

the employee either directly or indirectly of the employment.

The court has stated that there must be an adequate nexus and also the main

subject of the judicial consideration. The illustration of case law can be referred to

qualify the benefit under the judicial consideration. The law court in “J & G Knowles

& Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” held that in order to qualify as fringe benefit

there should be a sufficient and material relationship between the employment of the

employee and employer (Woodbury and Huang 2014). The provision of fringe benefit

does not take into the account the salaries or wages, superannuation contribution

under “sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986”.

A car fringe benefit originates under “s7 (1), FBTAA 1986” when it is noticed

that the employer has provided the employee with the car for the private usage of it.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3TAXATION LAW

Notably under “sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” the private use of the car means that the

use of car is not just simply restricted to the production of assessable income

(Gentry and Peress 2014). A car is said to be under the ownership of employee if the

car is garaged at the home of employee.

To calculate the fringe benefit tax of car the taxpayer must relate to the

statutory formula and the cost basis formula. Subject to “sec 10(1) of the FBTAA

1986” the statutory formula is applicable automatically unless the employer has

decided to use the cost basis (Turner 2017). Subject to “section 9, FBTAA 1986”

the statutory formula includes the cost base of the car which is multiplied with the

statutory rate. While the cost basis formula under “sec 10, FBTAA 1986” takes into

the consideration log book records and the odometer recording.

Application:

The evidences that is obtained from the case of Spiceco Pty Ltd it is very

much clear that the company provided its employee with the car that was exclusively

for the private use of the employee. The car was provided by the Spiceco Pty Ltd to

Lucinda through the FBT year and incurred cost on running expenses. The car was

used 70% of the time by Lucinda for business purpose while the remaining 30% of

the time it was used by Lucinda for her private purpose.

A car fringe benefit originates under “s7 (1), FBTAA 1986” for Spiceco Pty

Ltd when it is noticed that the employer has provided Lucinda with the car for the

private usage of it. Notably under “sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” the private use of the

car for Lucinda implies that the use of car is not just simply restricted to the

production of assessable income (Leibowitz 2013). Subject to “sec 136 (1), FBTAA

1986” the car fringe benefit is given to Lucinda by reason of or by virtue of the

employment of the employee.

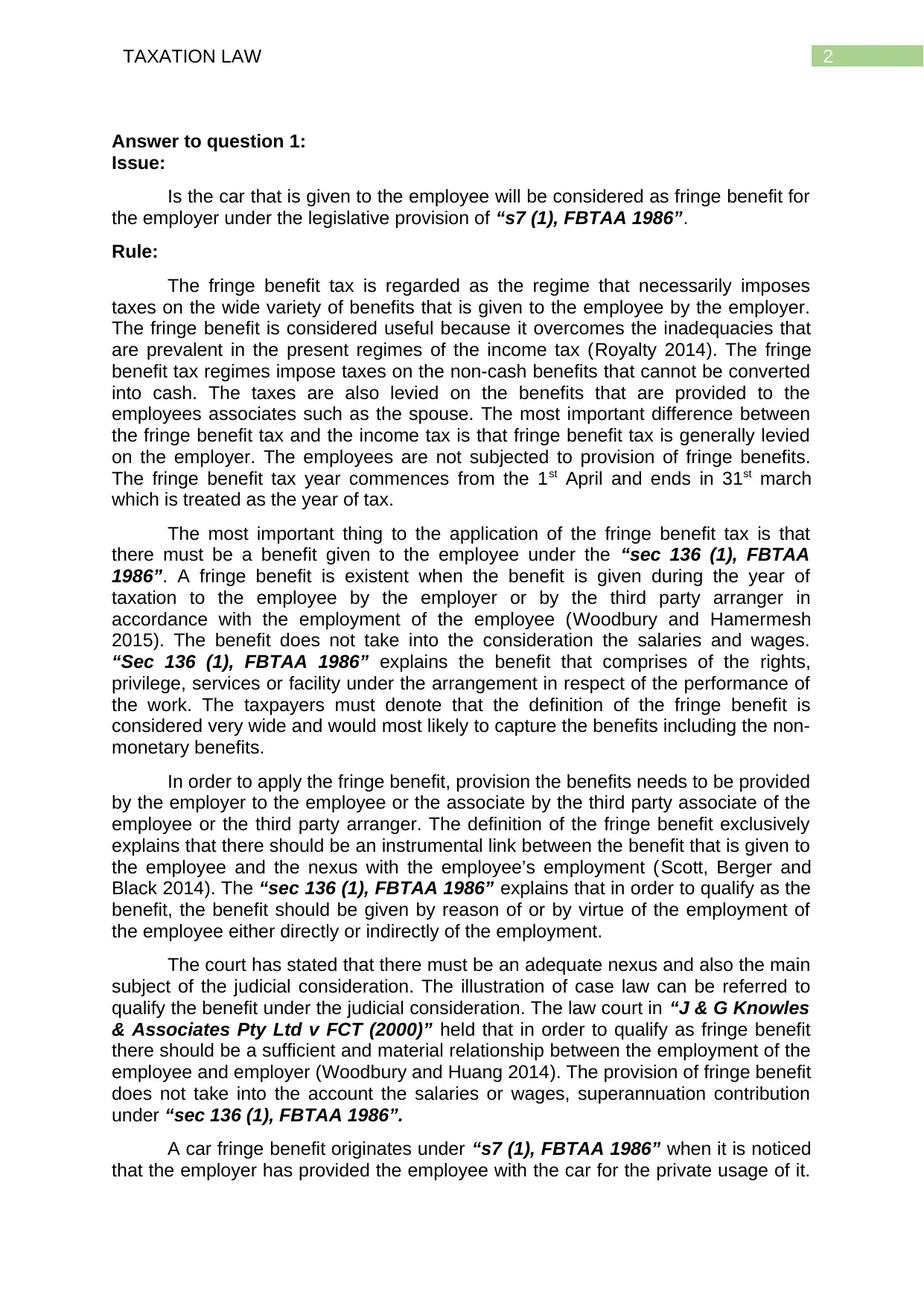

By citing “J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” the benefit

qualifies as the fringe benefit because there is a sufficient and material relationship

between the employment of Lucinda and Spiceco Pty Ltd (Katz and Mankiw 2015).

To calculate the fringe benefit tax of car statutory formula and the cost basis formula

is referred in the situation of Spiceco Pty Ltd. Subject to “section 9, FBTAA 1986”

the statutory formula includes the cost base of the car which is multiplied with the

statutory rate.

Notably under “sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” the private use of the car means that the

use of car is not just simply restricted to the production of assessable income

(Gentry and Peress 2014). A car is said to be under the ownership of employee if the

car is garaged at the home of employee.

To calculate the fringe benefit tax of car the taxpayer must relate to the

statutory formula and the cost basis formula. Subject to “sec 10(1) of the FBTAA

1986” the statutory formula is applicable automatically unless the employer has

decided to use the cost basis (Turner 2017). Subject to “section 9, FBTAA 1986”

the statutory formula includes the cost base of the car which is multiplied with the

statutory rate. While the cost basis formula under “sec 10, FBTAA 1986” takes into

the consideration log book records and the odometer recording.

Application:

The evidences that is obtained from the case of Spiceco Pty Ltd it is very

much clear that the company provided its employee with the car that was exclusively

for the private use of the employee. The car was provided by the Spiceco Pty Ltd to

Lucinda through the FBT year and incurred cost on running expenses. The car was

used 70% of the time by Lucinda for business purpose while the remaining 30% of

the time it was used by Lucinda for her private purpose.

A car fringe benefit originates under “s7 (1), FBTAA 1986” for Spiceco Pty

Ltd when it is noticed that the employer has provided Lucinda with the car for the

private usage of it. Notably under “sec 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” the private use of the

car for Lucinda implies that the use of car is not just simply restricted to the

production of assessable income (Leibowitz 2013). Subject to “sec 136 (1), FBTAA

1986” the car fringe benefit is given to Lucinda by reason of or by virtue of the

employment of the employee.

By citing “J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” the benefit

qualifies as the fringe benefit because there is a sufficient and material relationship

between the employment of Lucinda and Spiceco Pty Ltd (Katz and Mankiw 2015).

To calculate the fringe benefit tax of car statutory formula and the cost basis formula

is referred in the situation of Spiceco Pty Ltd. Subject to “section 9, FBTAA 1986”

the statutory formula includes the cost base of the car which is multiplied with the

statutory rate.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4TAXATION LAW

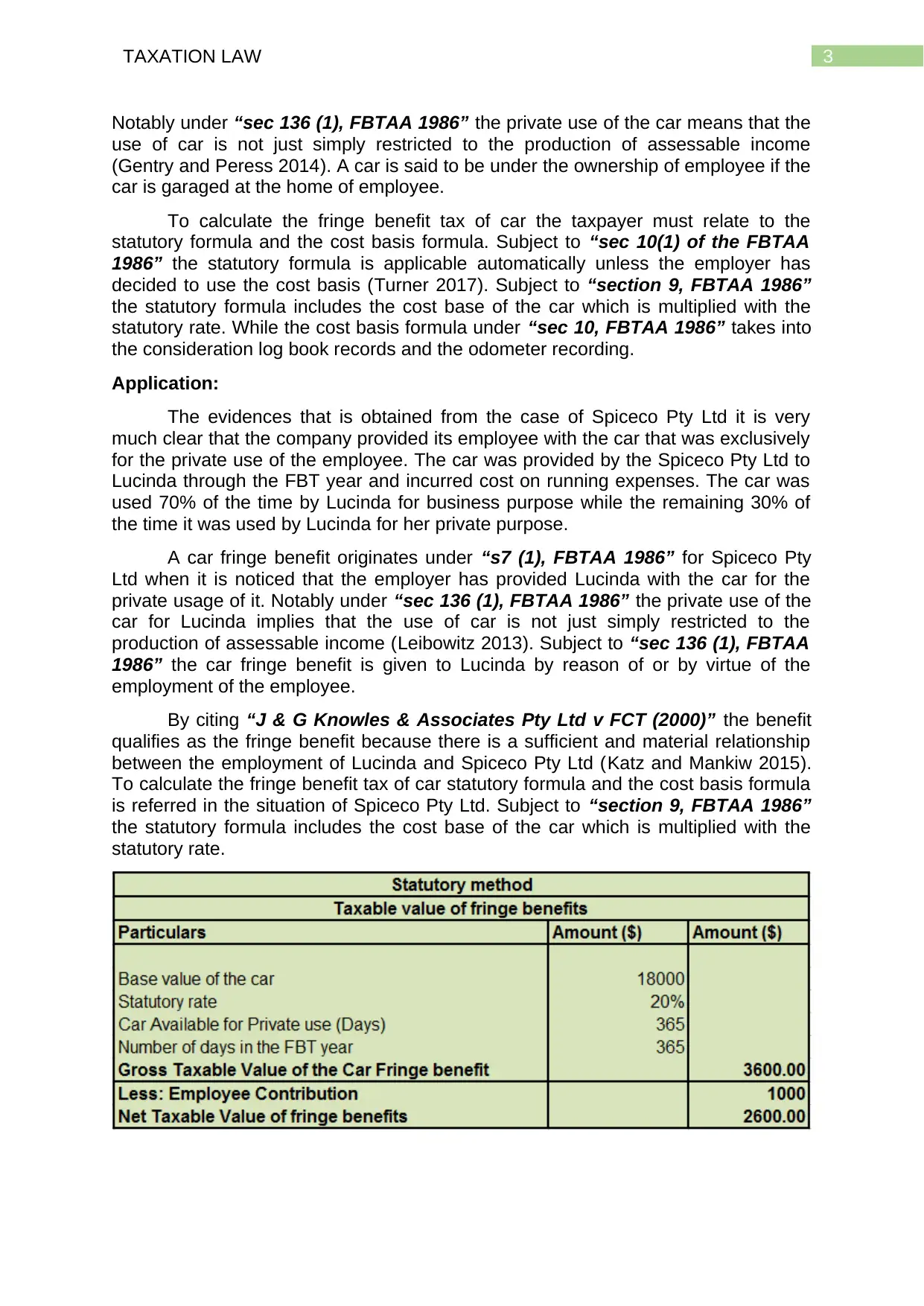

The cost basis formula under “sec 10, FBTAA 1986” takes into the

consideration log book records and the odometer recording of the car that is given to

Lucinda (Adamache and Sloan 2015).

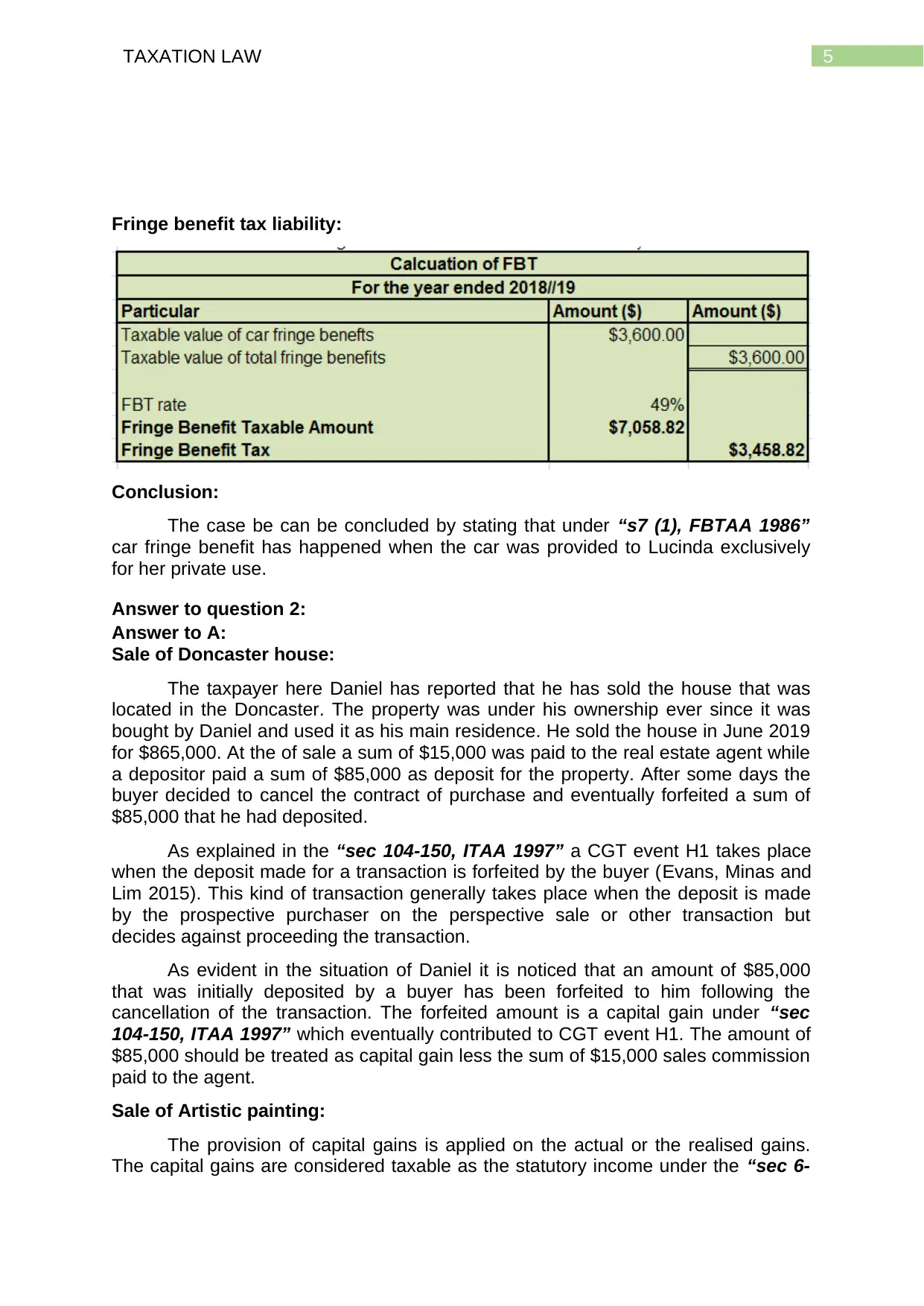

The calculation that is done above clearly shows that the amount of tax that

will be paid under the statutory formula is greater than the log book method. In other

words, total amount of tax to be paid to be paid under the log book method is lower

than the statutory method. Spiceco Pty Ltd is advised to follow the log book method

for paying lower fringe benefit tax.

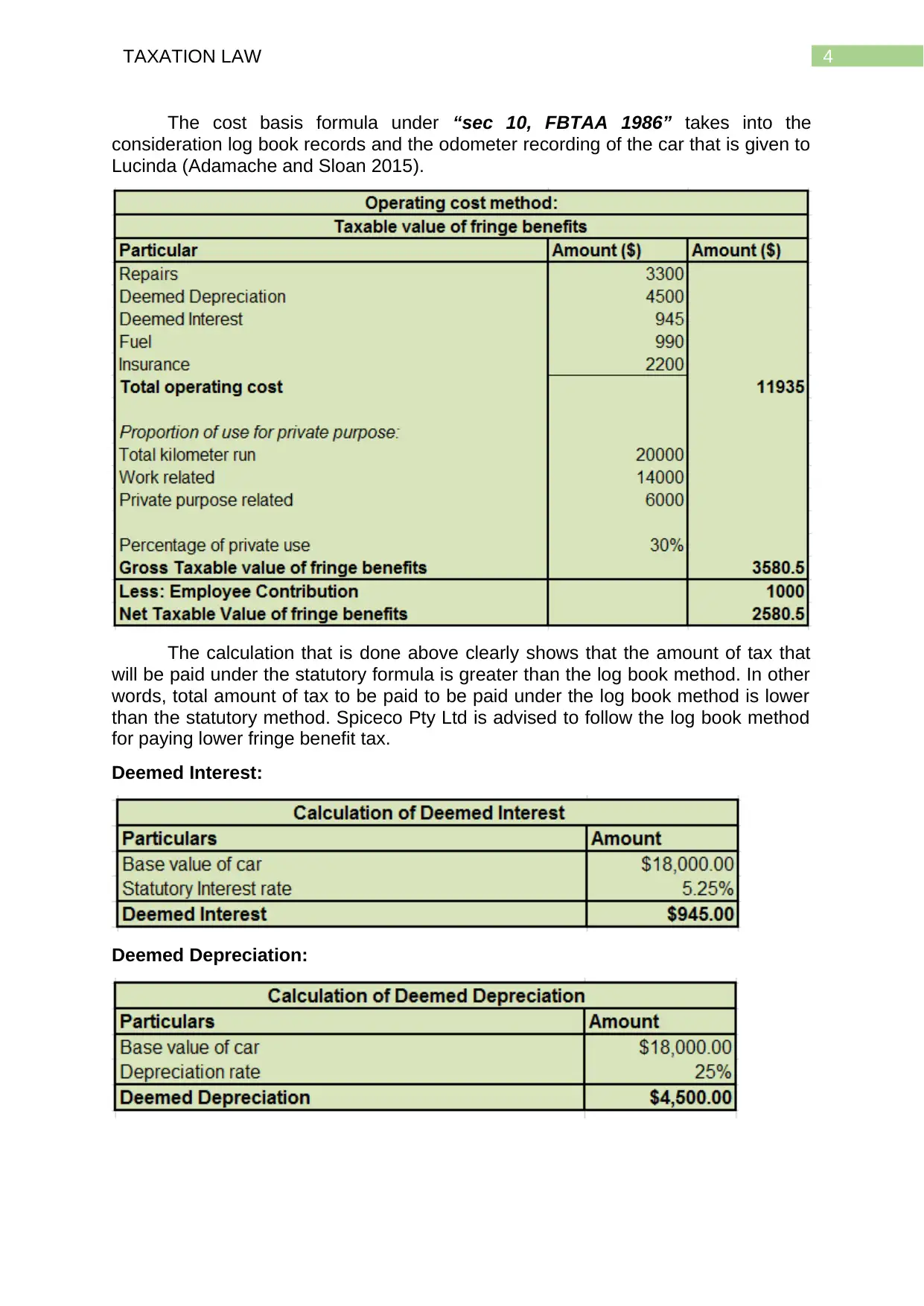

Deemed Interest:

Deemed Depreciation:

The cost basis formula under “sec 10, FBTAA 1986” takes into the

consideration log book records and the odometer recording of the car that is given to

Lucinda (Adamache and Sloan 2015).

The calculation that is done above clearly shows that the amount of tax that

will be paid under the statutory formula is greater than the log book method. In other

words, total amount of tax to be paid to be paid under the log book method is lower

than the statutory method. Spiceco Pty Ltd is advised to follow the log book method

for paying lower fringe benefit tax.

Deemed Interest:

Deemed Depreciation:

5TAXATION LAW

Fringe benefit tax liability:

Conclusion:

The case be can be concluded by stating that under “s7 (1), FBTAA 1986”

car fringe benefit has happened when the car was provided to Lucinda exclusively

for her private use.

Answer to question 2:

Answer to A:

Sale of Doncaster house:

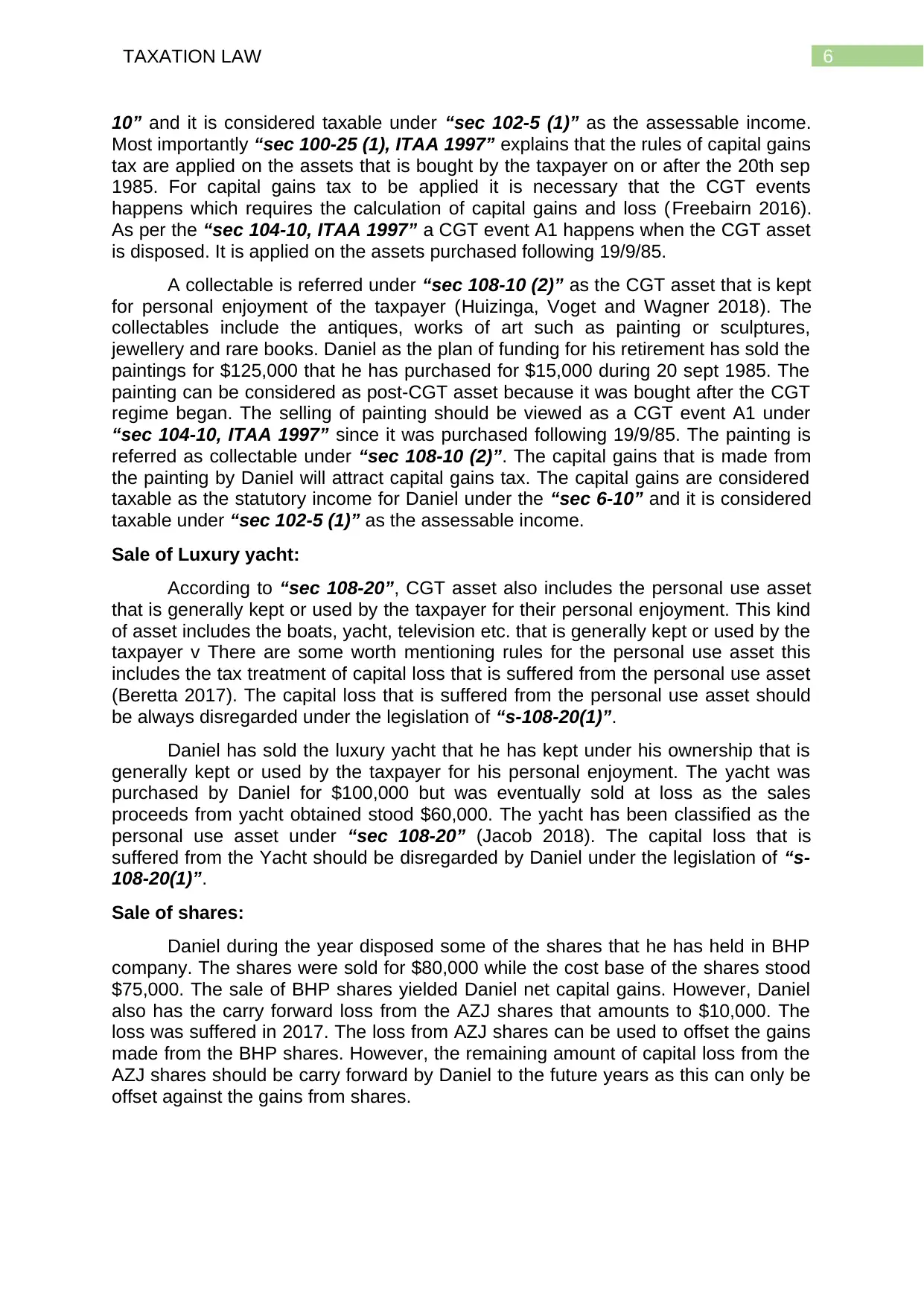

The taxpayer here Daniel has reported that he has sold the house that was

located in the Doncaster. The property was under his ownership ever since it was

bought by Daniel and used it as his main residence. He sold the house in June 2019

for $865,000. At the of sale a sum of $15,000 was paid to the real estate agent while

a depositor paid a sum of $85,000 as deposit for the property. After some days the

buyer decided to cancel the contract of purchase and eventually forfeited a sum of

$85,000 that he had deposited.

As explained in the “sec 104-150, ITAA 1997” a CGT event H1 takes place

when the deposit made for a transaction is forfeited by the buyer (Evans, Minas and

Lim 2015). This kind of transaction generally takes place when the deposit is made

by the prospective purchaser on the perspective sale or other transaction but

decides against proceeding the transaction.

As evident in the situation of Daniel it is noticed that an amount of $85,000

that was initially deposited by a buyer has been forfeited to him following the

cancellation of the transaction. The forfeited amount is a capital gain under “sec

104-150, ITAA 1997” which eventually contributed to CGT event H1. The amount of

$85,000 should be treated as capital gain less the sum of $15,000 sales commission

paid to the agent.

Sale of Artistic painting:

The provision of capital gains is applied on the actual or the realised gains.

The capital gains are considered taxable as the statutory income under the “sec 6-

Fringe benefit tax liability:

Conclusion:

The case be can be concluded by stating that under “s7 (1), FBTAA 1986”

car fringe benefit has happened when the car was provided to Lucinda exclusively

for her private use.

Answer to question 2:

Answer to A:

Sale of Doncaster house:

The taxpayer here Daniel has reported that he has sold the house that was

located in the Doncaster. The property was under his ownership ever since it was

bought by Daniel and used it as his main residence. He sold the house in June 2019

for $865,000. At the of sale a sum of $15,000 was paid to the real estate agent while

a depositor paid a sum of $85,000 as deposit for the property. After some days the

buyer decided to cancel the contract of purchase and eventually forfeited a sum of

$85,000 that he had deposited.

As explained in the “sec 104-150, ITAA 1997” a CGT event H1 takes place

when the deposit made for a transaction is forfeited by the buyer (Evans, Minas and

Lim 2015). This kind of transaction generally takes place when the deposit is made

by the prospective purchaser on the perspective sale or other transaction but

decides against proceeding the transaction.

As evident in the situation of Daniel it is noticed that an amount of $85,000

that was initially deposited by a buyer has been forfeited to him following the

cancellation of the transaction. The forfeited amount is a capital gain under “sec

104-150, ITAA 1997” which eventually contributed to CGT event H1. The amount of

$85,000 should be treated as capital gain less the sum of $15,000 sales commission

paid to the agent.

Sale of Artistic painting:

The provision of capital gains is applied on the actual or the realised gains.

The capital gains are considered taxable as the statutory income under the “sec 6-

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6TAXATION LAW

10” and it is considered taxable under “sec 102-5 (1)” as the assessable income.

Most importantly “sec 100-25 (1), ITAA 1997” explains that the rules of capital gains

tax are applied on the assets that is bought by the taxpayer on or after the 20th sep

1985. For capital gains tax to be applied it is necessary that the CGT events

happens which requires the calculation of capital gains and loss (Freebairn 2016).

As per the “sec 104-10, ITAA 1997” a CGT event A1 happens when the CGT asset

is disposed. It is applied on the assets purchased following 19/9/85.

A collectable is referred under “sec 108-10 (2)” as the CGT asset that is kept

for personal enjoyment of the taxpayer (Huizinga, Voget and Wagner 2018). The

collectables include the antiques, works of art such as painting or sculptures,

jewellery and rare books. Daniel as the plan of funding for his retirement has sold the

paintings for $125,000 that he has purchased for $15,000 during 20 sept 1985. The

painting can be considered as post-CGT asset because it was bought after the CGT

regime began. The selling of painting should be viewed as a CGT event A1 under

“sec 104-10, ITAA 1997” since it was purchased following 19/9/85. The painting is

referred as collectable under “sec 108-10 (2)”. The capital gains that is made from

the painting by Daniel will attract capital gains tax. The capital gains are considered

taxable as the statutory income for Daniel under the “sec 6-10” and it is considered

taxable under “sec 102-5 (1)” as the assessable income.

Sale of Luxury yacht:

According to “sec 108-20”, CGT asset also includes the personal use asset

that is generally kept or used by the taxpayer for their personal enjoyment. This kind

of asset includes the boats, yacht, television etc. that is generally kept or used by the

taxpayer v There are some worth mentioning rules for the personal use asset this

includes the tax treatment of capital loss that is suffered from the personal use asset

(Beretta 2017). The capital loss that is suffered from the personal use asset should

be always disregarded under the legislation of “s-108-20(1)”.

Daniel has sold the luxury yacht that he has kept under his ownership that is

generally kept or used by the taxpayer for his personal enjoyment. The yacht was

purchased by Daniel for $100,000 but was eventually sold at loss as the sales

proceeds from yacht obtained stood $60,000. The yacht has been classified as the

personal use asset under “sec 108-20” (Jacob 2018). The capital loss that is

suffered from the Yacht should be disregarded by Daniel under the legislation of “s-

108-20(1)”.

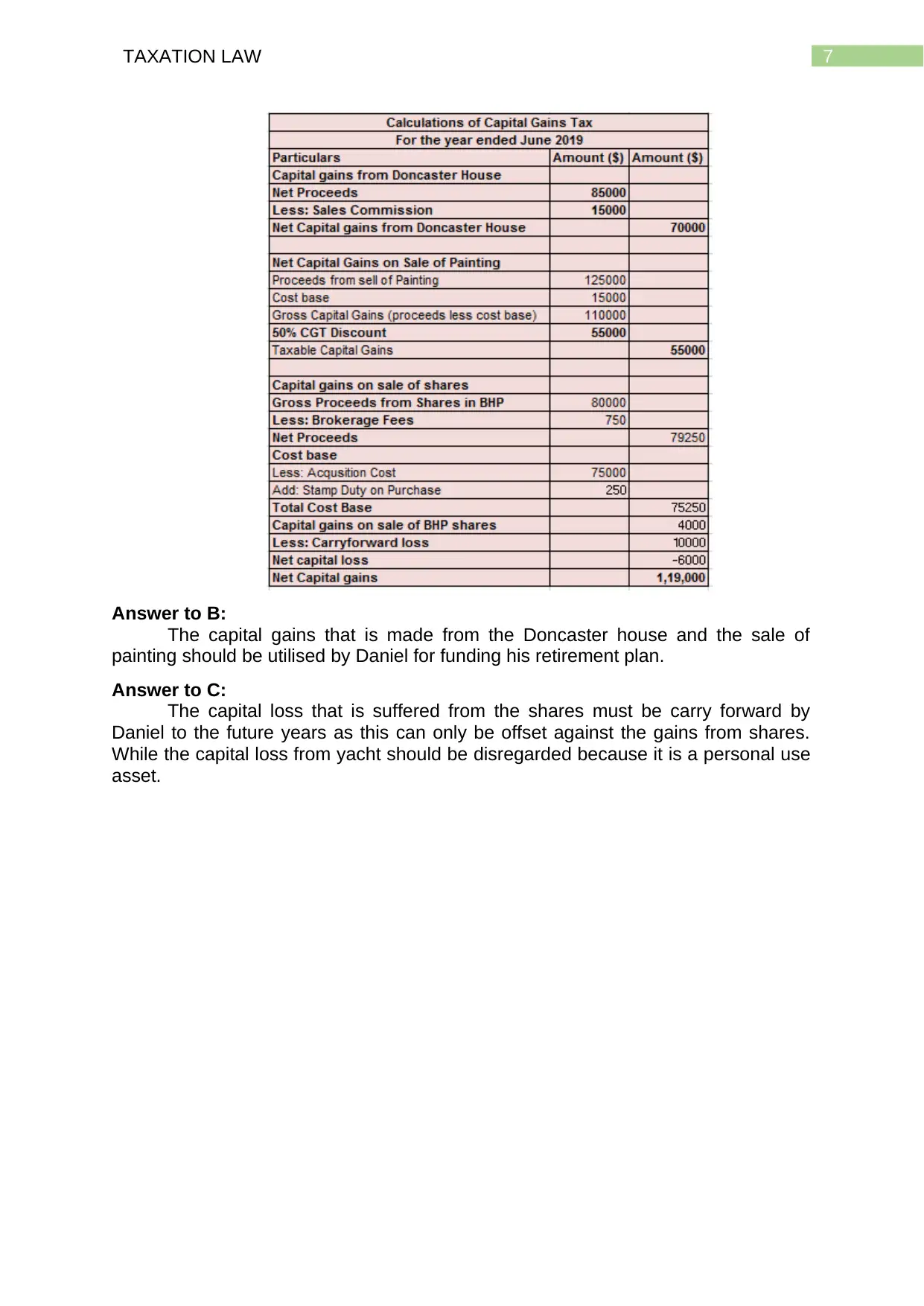

Sale of shares:

Daniel during the year disposed some of the shares that he has held in BHP

company. The shares were sold for $80,000 while the cost base of the shares stood

$75,000. The sale of BHP shares yielded Daniel net capital gains. However, Daniel

also has the carry forward loss from the AZJ shares that amounts to $10,000. The

loss was suffered in 2017. The loss from AZJ shares can be used to offset the gains

made from the BHP shares. However, the remaining amount of capital loss from the

AZJ shares should be carry forward by Daniel to the future years as this can only be

offset against the gains from shares.

10” and it is considered taxable under “sec 102-5 (1)” as the assessable income.

Most importantly “sec 100-25 (1), ITAA 1997” explains that the rules of capital gains

tax are applied on the assets that is bought by the taxpayer on or after the 20th sep

1985. For capital gains tax to be applied it is necessary that the CGT events

happens which requires the calculation of capital gains and loss (Freebairn 2016).

As per the “sec 104-10, ITAA 1997” a CGT event A1 happens when the CGT asset

is disposed. It is applied on the assets purchased following 19/9/85.

A collectable is referred under “sec 108-10 (2)” as the CGT asset that is kept

for personal enjoyment of the taxpayer (Huizinga, Voget and Wagner 2018). The

collectables include the antiques, works of art such as painting or sculptures,

jewellery and rare books. Daniel as the plan of funding for his retirement has sold the

paintings for $125,000 that he has purchased for $15,000 during 20 sept 1985. The

painting can be considered as post-CGT asset because it was bought after the CGT

regime began. The selling of painting should be viewed as a CGT event A1 under

“sec 104-10, ITAA 1997” since it was purchased following 19/9/85. The painting is

referred as collectable under “sec 108-10 (2)”. The capital gains that is made from

the painting by Daniel will attract capital gains tax. The capital gains are considered

taxable as the statutory income for Daniel under the “sec 6-10” and it is considered

taxable under “sec 102-5 (1)” as the assessable income.

Sale of Luxury yacht:

According to “sec 108-20”, CGT asset also includes the personal use asset

that is generally kept or used by the taxpayer for their personal enjoyment. This kind

of asset includes the boats, yacht, television etc. that is generally kept or used by the

taxpayer v There are some worth mentioning rules for the personal use asset this

includes the tax treatment of capital loss that is suffered from the personal use asset

(Beretta 2017). The capital loss that is suffered from the personal use asset should

be always disregarded under the legislation of “s-108-20(1)”.

Daniel has sold the luxury yacht that he has kept under his ownership that is

generally kept or used by the taxpayer for his personal enjoyment. The yacht was

purchased by Daniel for $100,000 but was eventually sold at loss as the sales

proceeds from yacht obtained stood $60,000. The yacht has been classified as the

personal use asset under “sec 108-20” (Jacob 2018). The capital loss that is

suffered from the Yacht should be disregarded by Daniel under the legislation of “s-

108-20(1)”.

Sale of shares:

Daniel during the year disposed some of the shares that he has held in BHP

company. The shares were sold for $80,000 while the cost base of the shares stood

$75,000. The sale of BHP shares yielded Daniel net capital gains. However, Daniel

also has the carry forward loss from the AZJ shares that amounts to $10,000. The

loss was suffered in 2017. The loss from AZJ shares can be used to offset the gains

made from the BHP shares. However, the remaining amount of capital loss from the

AZJ shares should be carry forward by Daniel to the future years as this can only be

offset against the gains from shares.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7TAXATION LAW

Answer to B:

The capital gains that is made from the Doncaster house and the sale of

painting should be utilised by Daniel for funding his retirement plan.

Answer to C:

The capital loss that is suffered from the shares must be carry forward by

Daniel to the future years as this can only be offset against the gains from shares.

While the capital loss from yacht should be disregarded because it is a personal use

asset.

Answer to B:

The capital gains that is made from the Doncaster house and the sale of

painting should be utilised by Daniel for funding his retirement plan.

Answer to C:

The capital loss that is suffered from the shares must be carry forward by

Daniel to the future years as this can only be offset against the gains from shares.

While the capital loss from yacht should be disregarded because it is a personal use

asset.

8TAXATION LAW

References:

Adamache, K.W. and Sloan, F.A., 2015. Fringe benefits: to tax or not to

tax?. National Tax Journal, pp.47-64.

Beretta, G., 2017. Taxation of individuals in the sharing economy. Intertax, 45(1),

pp.2-11.

Evans, C., Minas, J. and Lim, Y., 2015. Taxing personal capital gains in Australia: an

alternative way forward. Austl. Tax F., 30, p.735.

Freebairn, J., 2016. Taxation of housing. Australian Economic Review, 49(3),

pp.307-316.

Gentry, W.M. and Peress, E., 2014. Taxes and fringe benefits offered by

employers (No. w4764). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Huizinga, H., Voget, J. and Wagner, W., 2018. Capital gains taxation and the cost of

capital: Evidence from unanticipated cross-border transfers of tax base. Journal of

Financial Economics, 129(2), pp.306-328.

Jacob, M., 2018. Tax regimes and capital gains realizations. European Accounting

Review, 27(1), pp.1-21.

Katz, A. and Mankiw, N.G., 2015. How should fringe benefits be taxed?. National

Tax Journal, pp.37-46.

Leibowitz, A., 2013. Fringe benefits in employee compensation. In The

measurement of labor cost (pp. 371-394). University of Chicago Press.

Royalty, A.B., 2014. Tax preferences for fringe benefits and workers’ eligibility for

employer health insurance. Journal of Public Economics, 75(2), pp.209-227.

Scott, F.A., Berger, M.C. and Black, D.A., 2014. Effects of the tax treatment of fringe

benefits on labor market segmentation. ILR Review, 42(2), pp.216-229.

Turner, R.W., 2017. Are taxes responsible for the growth in fringe benefits?. National

Tax Journal, 40(2), p.205.

Woodbury, S.A. and Hamermesh, D.S., 2015. Taxes, fringe benefits and faculty. The

Review of Economics and Statistics, pp.287-296.

Woodbury, S.A. and Huang, W.J., 2014. The tax treatment of fringe benefits.

References:

Adamache, K.W. and Sloan, F.A., 2015. Fringe benefits: to tax or not to

tax?. National Tax Journal, pp.47-64.

Beretta, G., 2017. Taxation of individuals in the sharing economy. Intertax, 45(1),

pp.2-11.

Evans, C., Minas, J. and Lim, Y., 2015. Taxing personal capital gains in Australia: an

alternative way forward. Austl. Tax F., 30, p.735.

Freebairn, J., 2016. Taxation of housing. Australian Economic Review, 49(3),

pp.307-316.

Gentry, W.M. and Peress, E., 2014. Taxes and fringe benefits offered by

employers (No. w4764). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Huizinga, H., Voget, J. and Wagner, W., 2018. Capital gains taxation and the cost of

capital: Evidence from unanticipated cross-border transfers of tax base. Journal of

Financial Economics, 129(2), pp.306-328.

Jacob, M., 2018. Tax regimes and capital gains realizations. European Accounting

Review, 27(1), pp.1-21.

Katz, A. and Mankiw, N.G., 2015. How should fringe benefits be taxed?. National

Tax Journal, pp.37-46.

Leibowitz, A., 2013. Fringe benefits in employee compensation. In The

measurement of labor cost (pp. 371-394). University of Chicago Press.

Royalty, A.B., 2014. Tax preferences for fringe benefits and workers’ eligibility for

employer health insurance. Journal of Public Economics, 75(2), pp.209-227.

Scott, F.A., Berger, M.C. and Black, D.A., 2014. Effects of the tax treatment of fringe

benefits on labor market segmentation. ILR Review, 42(2), pp.216-229.

Turner, R.W., 2017. Are taxes responsible for the growth in fringe benefits?. National

Tax Journal, 40(2), p.205.

Woodbury, S.A. and Hamermesh, D.S., 2015. Taxes, fringe benefits and faculty. The

Review of Economics and Statistics, pp.287-296.

Woodbury, S.A. and Huang, W.J., 2014. The tax treatment of fringe benefits.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.