HA3042 Taxation Law: Fringe Benefits, CGT and Retirement Planning

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/03

|9

|2261

|470

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment solution delves into various aspects of taxation law, focusing on fringe benefit tax (FBT) and capital gains tax (CGT). It addresses the tax implications of an employer-provided car for personal use, calculating taxable values using both statutory and cost methods. Furthermore, it analyzes CGT events related to the sale of assets like a house, artistic painting, yacht, and shares, considering personal use assets and carried-forward capital losses. The document also provides recommendations for managing capital losses and investing capital gains into superannuation. Desklib offers this and many other solved assignments to help students excel in their studies.

Running head: TAXATION LAW

Taxation Law

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Taxation Law

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1TAXATION LAW

Table of Contents

Answer to question 1:.............................................................................................................2

Answer to question 2:.............................................................................................................4

Answer to A:.........................................................................................................................4

Answer to B:.........................................................................................................................7

Answer to C:.........................................................................................................................7

References:..............................................................................................................................8

Table of Contents

Answer to question 1:.............................................................................................................2

Answer to question 2:.............................................................................................................4

Answer to A:.........................................................................................................................4

Answer to B:.........................................................................................................................7

Answer to C:.........................................................................................................................7

References:..............................................................................................................................8

2TAXATION LAW

Answer to question 1:

Issues:

The central issue that is surrounding this case is the tax liability for the fringe

benefit that has been provided by the employer to the employee.

Rule:

The regimes of the fringe benefit tax are regarded as the tax that is applied on

the wide range of the benefits given to the employer to the employee. The provision

of the fringe benefit that is given in the “FBTAA 1986” lay down the key differences

amid the fringe benefit tax and the income tax (Hemmings and Tuske 2015). The key

points to remember is that taxes are levied on the employer and the employee does

not have to pay the tax on the provision of the fringe benefits. The rate of tax that is

implied is the personal marginal tax rate of the 45% along with the Medicare levy of

2%. Hence, the 47% for fringe benefit is applied at the end of the year.

Referring to “s, 136-(1), FBTAA 1986” the main fundamental that is involved

in the application of the fringe benefit tax is the benefit that is existent under this

definition (Eichfelder and Vaillancourt 2014). As explained in “s, 136 (1), FBTAA

1986” the fringe benefit that is existent includes the fringe benefit that is provided

during the year of taxation by the employer to the associate of the party arranger to

the employee in relation to the employment of the employee.

The benefit generally includes the rights or the privilege of the services that is

given to the employee under the arrangement in respect of the performance of the

work under “s, 136 (1), FBTAA 1986”. Under the “s, 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” the

term benefit generally involves the employer, associate of the employer or the third

party arranger (Daley, McGannon and Hunter 2014). It is noteworthy to denote that

there should be a connection among the employment and the benefit. A benefit

qualifies as the fringe benefit when it is provided to the employer by virtue of the

direct or indirect relation of employment.

The court in “J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” held that

the nexus requirement in relation to the employment and benefits provided is

important to establish the link with the fringe benefits (Schellekens 2016). Under the

“s, 7 (1), FBTAA 1986” the car fringe benefit happens when the employer provides

the car to the employee for their personal usage. The personal usage generally

means that the car is not wholly in the course of generating the assessable income

under “s, 136 (1), FBTAA 1986”.

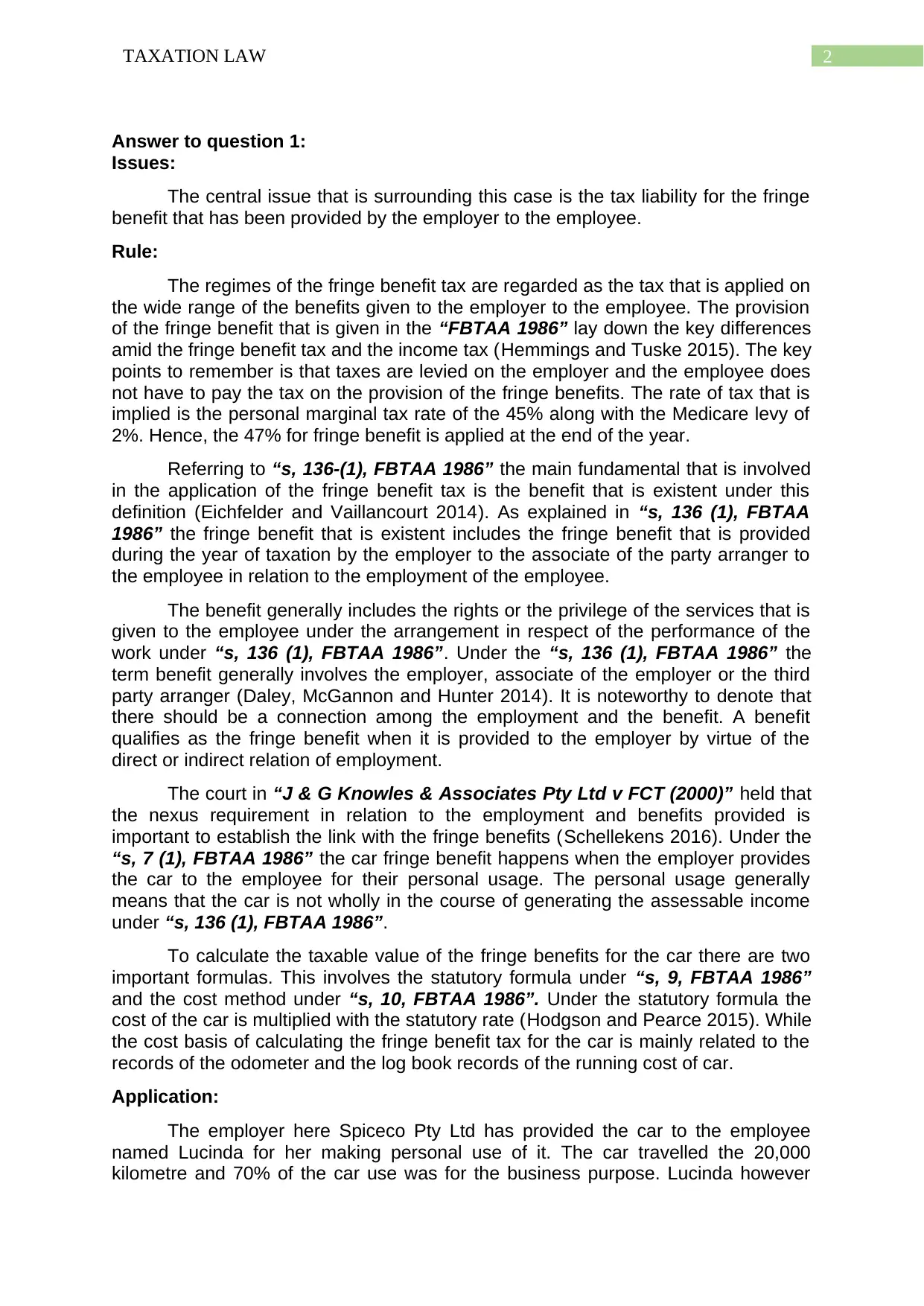

To calculate the taxable value of the fringe benefits for the car there are two

important formulas. This involves the statutory formula under “s, 9, FBTAA 1986”

and the cost method under “s, 10, FBTAA 1986”. Under the statutory formula the

cost of the car is multiplied with the statutory rate (Hodgson and Pearce 2015). While

the cost basis of calculating the fringe benefit tax for the car is mainly related to the

records of the odometer and the log book records of the running cost of car.

Application:

The employer here Spiceco Pty Ltd has provided the car to the employee

named Lucinda for her making personal use of it. The car travelled the 20,000

kilometre and 70% of the car use was for the business purpose. Lucinda however

Answer to question 1:

Issues:

The central issue that is surrounding this case is the tax liability for the fringe

benefit that has been provided by the employer to the employee.

Rule:

The regimes of the fringe benefit tax are regarded as the tax that is applied on

the wide range of the benefits given to the employer to the employee. The provision

of the fringe benefit that is given in the “FBTAA 1986” lay down the key differences

amid the fringe benefit tax and the income tax (Hemmings and Tuske 2015). The key

points to remember is that taxes are levied on the employer and the employee does

not have to pay the tax on the provision of the fringe benefits. The rate of tax that is

implied is the personal marginal tax rate of the 45% along with the Medicare levy of

2%. Hence, the 47% for fringe benefit is applied at the end of the year.

Referring to “s, 136-(1), FBTAA 1986” the main fundamental that is involved

in the application of the fringe benefit tax is the benefit that is existent under this

definition (Eichfelder and Vaillancourt 2014). As explained in “s, 136 (1), FBTAA

1986” the fringe benefit that is existent includes the fringe benefit that is provided

during the year of taxation by the employer to the associate of the party arranger to

the employee in relation to the employment of the employee.

The benefit generally includes the rights or the privilege of the services that is

given to the employee under the arrangement in respect of the performance of the

work under “s, 136 (1), FBTAA 1986”. Under the “s, 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” the

term benefit generally involves the employer, associate of the employer or the third

party arranger (Daley, McGannon and Hunter 2014). It is noteworthy to denote that

there should be a connection among the employment and the benefit. A benefit

qualifies as the fringe benefit when it is provided to the employer by virtue of the

direct or indirect relation of employment.

The court in “J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” held that

the nexus requirement in relation to the employment and benefits provided is

important to establish the link with the fringe benefits (Schellekens 2016). Under the

“s, 7 (1), FBTAA 1986” the car fringe benefit happens when the employer provides

the car to the employee for their personal usage. The personal usage generally

means that the car is not wholly in the course of generating the assessable income

under “s, 136 (1), FBTAA 1986”.

To calculate the taxable value of the fringe benefits for the car there are two

important formulas. This involves the statutory formula under “s, 9, FBTAA 1986”

and the cost method under “s, 10, FBTAA 1986”. Under the statutory formula the

cost of the car is multiplied with the statutory rate (Hodgson and Pearce 2015). While

the cost basis of calculating the fringe benefit tax for the car is mainly related to the

records of the odometer and the log book records of the running cost of car.

Application:

The employer here Spiceco Pty Ltd has provided the car to the employee

named Lucinda for her making personal use of it. The car travelled the 20,000

kilometre and 70% of the car use was for the business purpose. Lucinda however

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3TAXATION LAW

contributed $1,000 for the cost of the car. The car that is provided to Lucinda by the

employer has given rise to the car fringe benefit under “s, 7, FBTAA 1986”

(Edmonds 2015).

By referring to the “s, 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” the car has been given to the

employee because of the employment with the Spiceco Pty Ltd. Raising the verdict

given in the “J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” the nexus

requirement in relation to the employment and benefits in relation to the employment

of the employee (Braverman, Marsden and Sadiq 2015). It can be stated that the

sufficient and material relationship is existent between Spiceco Pty Ltd and Lucinda.

In addition to this, references have also been made to the statutory and cost

method to calculate the fringe benefit tax.

As evident from the above stated calculation it is noted that the net amount of

taxable value under the “s, 9, FBTAA 1986” stands $2600. On the other hand, the

net taxable value under the operating cost method stands $3,580 (Shields and

North-Samardzic 2015). As understood from the above stated calculation it can be

contributed $1,000 for the cost of the car. The car that is provided to Lucinda by the

employer has given rise to the car fringe benefit under “s, 7, FBTAA 1986”

(Edmonds 2015).

By referring to the “s, 136 (1), FBTAA 1986” the car has been given to the

employee because of the employment with the Spiceco Pty Ltd. Raising the verdict

given in the “J & G Knowles & Associates Pty Ltd v FCT (2000)” the nexus

requirement in relation to the employment and benefits in relation to the employment

of the employee (Braverman, Marsden and Sadiq 2015). It can be stated that the

sufficient and material relationship is existent between Spiceco Pty Ltd and Lucinda.

In addition to this, references have also been made to the statutory and cost

method to calculate the fringe benefit tax.

As evident from the above stated calculation it is noted that the net amount of

taxable value under the “s, 9, FBTAA 1986” stands $2600. On the other hand, the

net taxable value under the operating cost method stands $3,580 (Shields and

North-Samardzic 2015). As understood from the above stated calculation it can be

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4TAXATION LAW

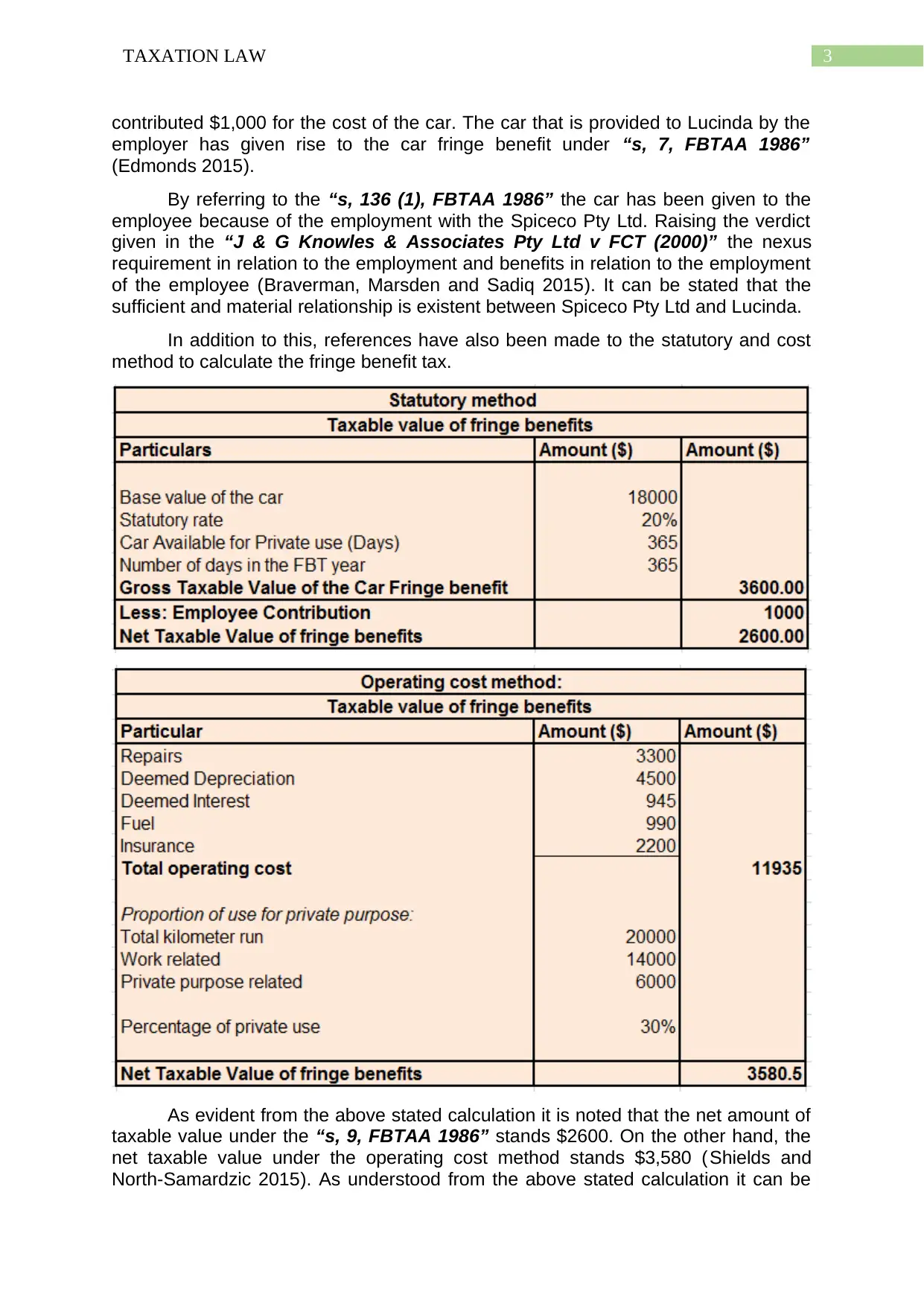

stated net taxable value under the statutory method is lower than the operating cost

method. The taxpayer here Spiceco Pty Ltd is required to consider the statutory

method than the operating cost method.

Calculation of the Deemed Interest:

Calculation of the Deemed Depreciation:

Calculation of the Fringe Benefit Tax:

Conclusion:

The analysis that evidently explains that there was the sufficient relation

among the employer and the employee. The benefit originated in respect of the

employment relationship. The car was exclusively provided to Lucinda for making the

private use of it.

Answer to question 2:

Answer to A:

A gain that is characterised as the capital will not be the subject of income tax

within the ordinary meaning. The capital gains tax began on 20th September 1985

and takes into the consideration the capital receipts in the tax base. The income tax

liability of the taxpayer also includes the net amount of capital gains that are made

(Barkoczy 2017). The capital gains tax is not the distinct tax and it is integrated in the

income tax regimes. As defined in the “sec 102-5, ITAA 1997” the net capital gains

for the income year is the assessable as the statutory income. The liability to capital

stated net taxable value under the statutory method is lower than the operating cost

method. The taxpayer here Spiceco Pty Ltd is required to consider the statutory

method than the operating cost method.

Calculation of the Deemed Interest:

Calculation of the Deemed Depreciation:

Calculation of the Fringe Benefit Tax:

Conclusion:

The analysis that evidently explains that there was the sufficient relation

among the employer and the employee. The benefit originated in respect of the

employment relationship. The car was exclusively provided to Lucinda for making the

private use of it.

Answer to question 2:

Answer to A:

A gain that is characterised as the capital will not be the subject of income tax

within the ordinary meaning. The capital gains tax began on 20th September 1985

and takes into the consideration the capital receipts in the tax base. The income tax

liability of the taxpayer also includes the net amount of capital gains that are made

(Barkoczy 2017). The capital gains tax is not the distinct tax and it is integrated in the

income tax regimes. As defined in the “sec 102-5, ITAA 1997” the net capital gains

for the income year is the assessable as the statutory income. The liability to capital

5TAXATION LAW

gains is determined on the basis of whether the taxpayer has made capital gains or

loss and also involves working out the net amount of capital gains or loss (Kenny,

Blissenden and Villios 2018). To ascertain whether the net capital gains or capital

loss has been made by the taxpayer it is necessary to determine whether the CGT

event has taken place to the taxpayer and whether the asset is the CGT asset. It

also includes whether the any exception or exemption is applicable. Under “sec,

102-20, ITAA 1997” a taxpayer only makes the capital gain or the loss if the CGT

event takes place.

The case study here provides that the Daniel Ray who is planning for

retirement has decided to make the contribution to his superannuation fund prior to

the end of this year. With the objective of collecting $1 million for his superannuation

investment, Daniel has sold some of his asset during the year. The tax treatment for

the assets are given below;

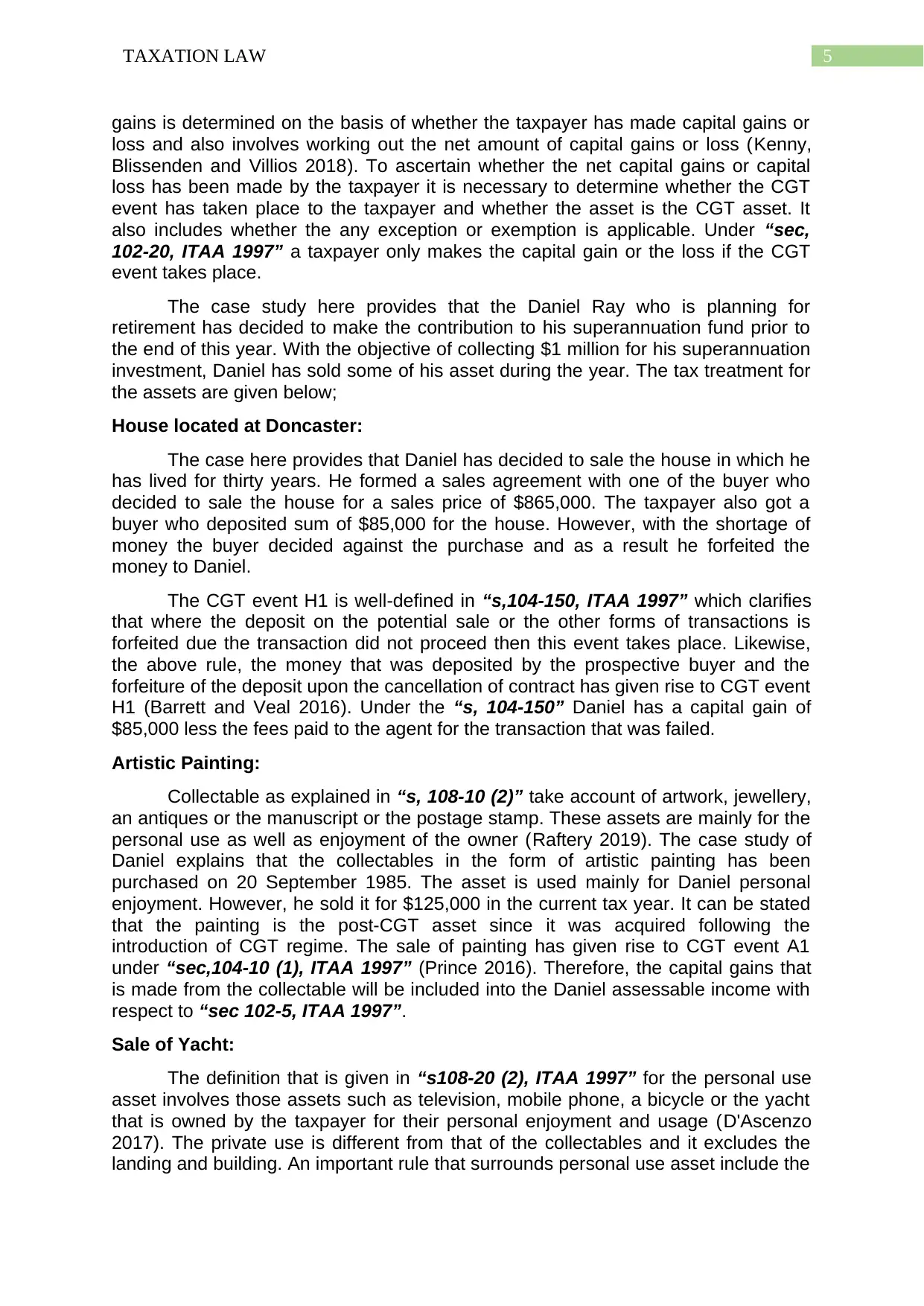

House located at Doncaster:

The case here provides that Daniel has decided to sale the house in which he

has lived for thirty years. He formed a sales agreement with one of the buyer who

decided to sale the house for a sales price of $865,000. The taxpayer also got a

buyer who deposited sum of $85,000 for the house. However, with the shortage of

money the buyer decided against the purchase and as a result he forfeited the

money to Daniel.

The CGT event H1 is well-defined in “s,104-150, ITAA 1997” which clarifies

that where the deposit on the potential sale or the other forms of transactions is

forfeited due the transaction did not proceed then this event takes place. Likewise,

the above rule, the money that was deposited by the prospective buyer and the

forfeiture of the deposit upon the cancellation of contract has given rise to CGT event

H1 (Barrett and Veal 2016). Under the “s, 104-150” Daniel has a capital gain of

$85,000 less the fees paid to the agent for the transaction that was failed.

Artistic Painting:

Collectable as explained in “s, 108-10 (2)” take account of artwork, jewellery,

an antiques or the manuscript or the postage stamp. These assets are mainly for the

personal use as well as enjoyment of the owner (Raftery 2019). The case study of

Daniel explains that the collectables in the form of artistic painting has been

purchased on 20 September 1985. The asset is used mainly for Daniel personal

enjoyment. However, he sold it for $125,000 in the current tax year. It can be stated

that the painting is the post-CGT asset since it was acquired following the

introduction of CGT regime. The sale of painting has given rise to CGT event A1

under “sec,104-10 (1), ITAA 1997” (Prince 2016). Therefore, the capital gains that

is made from the collectable will be included into the Daniel assessable income with

respect to “sec 102-5, ITAA 1997”.

Sale of Yacht:

The definition that is given in “s108-20 (2), ITAA 1997” for the personal use

asset involves those assets such as television, mobile phone, a bicycle or the yacht

that is owned by the taxpayer for their personal enjoyment and usage (D'Ascenzo

2017). The private use is different from that of the collectables and it excludes the

landing and building. An important rule that surrounds personal use asset include the

gains is determined on the basis of whether the taxpayer has made capital gains or

loss and also involves working out the net amount of capital gains or loss (Kenny,

Blissenden and Villios 2018). To ascertain whether the net capital gains or capital

loss has been made by the taxpayer it is necessary to determine whether the CGT

event has taken place to the taxpayer and whether the asset is the CGT asset. It

also includes whether the any exception or exemption is applicable. Under “sec,

102-20, ITAA 1997” a taxpayer only makes the capital gain or the loss if the CGT

event takes place.

The case study here provides that the Daniel Ray who is planning for

retirement has decided to make the contribution to his superannuation fund prior to

the end of this year. With the objective of collecting $1 million for his superannuation

investment, Daniel has sold some of his asset during the year. The tax treatment for

the assets are given below;

House located at Doncaster:

The case here provides that Daniel has decided to sale the house in which he

has lived for thirty years. He formed a sales agreement with one of the buyer who

decided to sale the house for a sales price of $865,000. The taxpayer also got a

buyer who deposited sum of $85,000 for the house. However, with the shortage of

money the buyer decided against the purchase and as a result he forfeited the

money to Daniel.

The CGT event H1 is well-defined in “s,104-150, ITAA 1997” which clarifies

that where the deposit on the potential sale or the other forms of transactions is

forfeited due the transaction did not proceed then this event takes place. Likewise,

the above rule, the money that was deposited by the prospective buyer and the

forfeiture of the deposit upon the cancellation of contract has given rise to CGT event

H1 (Barrett and Veal 2016). Under the “s, 104-150” Daniel has a capital gain of

$85,000 less the fees paid to the agent for the transaction that was failed.

Artistic Painting:

Collectable as explained in “s, 108-10 (2)” take account of artwork, jewellery,

an antiques or the manuscript or the postage stamp. These assets are mainly for the

personal use as well as enjoyment of the owner (Raftery 2019). The case study of

Daniel explains that the collectables in the form of artistic painting has been

purchased on 20 September 1985. The asset is used mainly for Daniel personal

enjoyment. However, he sold it for $125,000 in the current tax year. It can be stated

that the painting is the post-CGT asset since it was acquired following the

introduction of CGT regime. The sale of painting has given rise to CGT event A1

under “sec,104-10 (1), ITAA 1997” (Prince 2016). Therefore, the capital gains that

is made from the collectable will be included into the Daniel assessable income with

respect to “sec 102-5, ITAA 1997”.

Sale of Yacht:

The definition that is given in “s108-20 (2), ITAA 1997” for the personal use

asset involves those assets such as television, mobile phone, a bicycle or the yacht

that is owned by the taxpayer for their personal enjoyment and usage (D'Ascenzo

2017). The private use is different from that of the collectables and it excludes the

landing and building. An important rule that surrounds personal use asset include the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6TAXATION LAW

capital loss that are suffered by the taxpayer from the private use assets. This

includes that the taxpayer should simply ignore the capital loss that is made from the

personal use asset.

Situations from the case study explains that a luxury yacht was owned by

Daniel for his personal enjoyment and use. He bought it for $110,000 but he had

sold it for a loss of $50,000 with the eventual selling price of $60,000. As a loss has

been occurred by Daniel from selling the yacht, Daniel is required to disregard the

loss from his yacht since it is private use of asset.

Sale of Shares:

During the year Daniel has also reported the shares in the BHP which he

bought for $75,000 in January 2019. The shares in BHP was eventually sold by

Daniel for $80,000. Similarly, the sale of shares has given rise to the CGT event A1

under “s, 104-10 (1), ITAA 1997” (Black 2018). The taxpayer here Daniel also

reported the capital loss that he has carried forward from the previous year. The

capital loss is from the AZJ shares that amounts to $10,000. Similarly, for Daniel he

is required to offset the loss against the capital gains from BHP shares since the loss

is not permitted to be deductible. The net loss will be carried forward to the

subsequent year by Daniel.

capital loss that are suffered by the taxpayer from the private use assets. This

includes that the taxpayer should simply ignore the capital loss that is made from the

personal use asset.

Situations from the case study explains that a luxury yacht was owned by

Daniel for his personal enjoyment and use. He bought it for $110,000 but he had

sold it for a loss of $50,000 with the eventual selling price of $60,000. As a loss has

been occurred by Daniel from selling the yacht, Daniel is required to disregard the

loss from his yacht since it is private use of asset.

Sale of Shares:

During the year Daniel has also reported the shares in the BHP which he

bought for $75,000 in January 2019. The shares in BHP was eventually sold by

Daniel for $80,000. Similarly, the sale of shares has given rise to the CGT event A1

under “s, 104-10 (1), ITAA 1997” (Black 2018). The taxpayer here Daniel also

reported the capital loss that he has carried forward from the previous year. The

capital loss is from the AZJ shares that amounts to $10,000. Similarly, for Daniel he

is required to offset the loss against the capital gains from BHP shares since the loss

is not permitted to be deductible. The net loss will be carried forward to the

subsequent year by Daniel.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7TAXATION LAW

Answer to B:

As evident from the above stated computation it is understood that net capital

gains that is earned from the sale of the above stated asset stands $1,19,000. As a

result of this, the net capital gains that is earned must be invested by Daniel in his

superannuation fund for his retirement purpose.

Answer to C:

As evident from the above stated computation and case analysis, it is

understood that Daniel during the year suffered loss upon disposing the personal

use asset. In other words, he suffered losses from the sale of Yacht. He also has the

remaining amount of his carry forward loss from the AZJ shares following the offset

against the BHP shares. It is recommended that Daniel should carry forward the left

over loss to next year and he is only allowed to offset those from the future gains that

would be made from the sale of shares.

Answer to B:

As evident from the above stated computation it is understood that net capital

gains that is earned from the sale of the above stated asset stands $1,19,000. As a

result of this, the net capital gains that is earned must be invested by Daniel in his

superannuation fund for his retirement purpose.

Answer to C:

As evident from the above stated computation and case analysis, it is

understood that Daniel during the year suffered loss upon disposing the personal

use asset. In other words, he suffered losses from the sale of Yacht. He also has the

remaining amount of his carry forward loss from the AZJ shares following the offset

against the BHP shares. It is recommended that Daniel should carry forward the left

over loss to next year and he is only allowed to offset those from the future gains that

would be made from the sale of shares.

8TAXATION LAW

References:

Barkoczy, S., 2017. Core tax legislation and study guide. OUP Catalogue.

Barrett, J.M. and Veal, J.A., 2016. Tax Rationality, Politics, and Media Spin: A Case

Study of the Failed ‘Car Park Tax’Proposal. Centre for Accounting, Governance and

Taxation Research Working Paper, (102).

Black, C., 2018. Taxation of Intellectual Property Under Domestic Law and Tax

Treaties: Australia. Taxation of Intellectual Property under Domestic Law, EU Law

and Tax Treaties", IBFD: Amsterdam.

Braverman, D., Marsden, S. and Sadiq, K., 2015. Assessing Taxpayer Response to

Legislative Changes: A Case Study of In-House Fringe Benefits Rules. J. Austl.

Tax'n, 17, p.1.

Daley, J., McGannon, C. and Hunter, A., 2014. Budget pressures on Australian

governments 2014. Grattan Institute.

D'Ascenzo, M., 2017. Academia as an Influencer of Tax Policy and Tax

Administration. J. Austl. Tax'n, 19, p.1.

Edmonds, R., 2015. Structural tax reform: What should be brought to the

table. Austl. Tax F., 30, p.393.

Eichfelder, S. and Vaillancourt, F., 2014. Tax compliance costs: A review of cost

burdens and cost structures. Available at SSRN 2535664.

Hemmings, P. and Tuske, A., 2015. Improving Taxes and Transfers in Australia.

Hodgson, H. and Pearce, P., 2015. TravelSmart of Travel Tax Breaks: Is the Fringe

Benefits Tax a Barrier to Active Commuting in Australia. eJTR, 13, p.819.

Kenny, P., Blissenden, M. and Villios, S., 2018. Australian Tax 2018.

Pearce, P. and Pinto, D., 2015. An evaluation of the case for a congestion tax in

Australia. The Tax Specialist, 18(4), pp.146-153.

Prince, J.B., 2016. Tax for Australians for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons.

Raftery, A., 2019. 101 Ways to Save Money on Your Tax-Legally! 2019-2020. Wiley.

Schellekens, M., 2016. Global Corporate Tax Handbook 2016. Internat. Belasting

Documentatie.

Shields, J. and North-Samardzic, A., 2015. 10 Employee benefits. Managing

Employee Performance and Reward: Concepts, Practices, Strategies, p.218.

References:

Barkoczy, S., 2017. Core tax legislation and study guide. OUP Catalogue.

Barrett, J.M. and Veal, J.A., 2016. Tax Rationality, Politics, and Media Spin: A Case

Study of the Failed ‘Car Park Tax’Proposal. Centre for Accounting, Governance and

Taxation Research Working Paper, (102).

Black, C., 2018. Taxation of Intellectual Property Under Domestic Law and Tax

Treaties: Australia. Taxation of Intellectual Property under Domestic Law, EU Law

and Tax Treaties", IBFD: Amsterdam.

Braverman, D., Marsden, S. and Sadiq, K., 2015. Assessing Taxpayer Response to

Legislative Changes: A Case Study of In-House Fringe Benefits Rules. J. Austl.

Tax'n, 17, p.1.

Daley, J., McGannon, C. and Hunter, A., 2014. Budget pressures on Australian

governments 2014. Grattan Institute.

D'Ascenzo, M., 2017. Academia as an Influencer of Tax Policy and Tax

Administration. J. Austl. Tax'n, 19, p.1.

Edmonds, R., 2015. Structural tax reform: What should be brought to the

table. Austl. Tax F., 30, p.393.

Eichfelder, S. and Vaillancourt, F., 2014. Tax compliance costs: A review of cost

burdens and cost structures. Available at SSRN 2535664.

Hemmings, P. and Tuske, A., 2015. Improving Taxes and Transfers in Australia.

Hodgson, H. and Pearce, P., 2015. TravelSmart of Travel Tax Breaks: Is the Fringe

Benefits Tax a Barrier to Active Commuting in Australia. eJTR, 13, p.819.

Kenny, P., Blissenden, M. and Villios, S., 2018. Australian Tax 2018.

Pearce, P. and Pinto, D., 2015. An evaluation of the case for a congestion tax in

Australia. The Tax Specialist, 18(4), pp.146-153.

Prince, J.B., 2016. Tax for Australians for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons.

Raftery, A., 2019. 101 Ways to Save Money on Your Tax-Legally! 2019-2020. Wiley.

Schellekens, M., 2016. Global Corporate Tax Handbook 2016. Internat. Belasting

Documentatie.

Shields, J. and North-Samardzic, A., 2015. 10 Employee benefits. Managing

Employee Performance and Reward: Concepts, Practices, Strategies, p.218.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.