Taxation Law Assignment: Analysis of Fringe Benefits and Capital Gains

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/04

|9

|2401

|335

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment provides a comprehensive analysis of taxation law, focusing on two key areas: fringe benefits tax (FBT) and capital gains tax (CGT). The first part of the assignment examines whether providing a car to an employee constitutes a fringe benefit under the FBTAA 1986, considering relevant legislation and case facts. It calculates the taxable value of the car fringe benefit using both statutory formula and operating cost methods, concluding with a determination of the employer's tax liability. The second part of the assignment delves into capital gains tax, addressing the tax implications of various transactions. It analyzes the sale of a property, a painting, and a luxury yacht, as well as the sale of shares, determining whether capital gains or losses arise and how they are treated for tax purposes. The assignment concludes with a discussion of how capital gains can be used for retirement planning. The document includes detailed calculations, legal references, and a clear application of tax principles to real-world scenarios.

Running head: TAXATION LAW

Taxation Law

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Taxation Law

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1TAXATION LAW

Table of Contents

Answer to question 1:...................................................................................................2

Answer to question 2:...................................................................................................5

Answer to question A:...............................................................................................5

Answer to question B:...............................................................................................7

Answer to question C:...............................................................................................7

References:..................................................................................................................8

Table of Contents

Answer to question 1:...................................................................................................2

Answer to question 2:...................................................................................................5

Answer to question A:...............................................................................................5

Answer to question B:...............................................................................................7

Answer to question C:...............................................................................................7

References:..................................................................................................................8

2TAXATION LAW

Answer to question 1:

Issues:

Whether or not giving the car to the employee throughout the employment will

be considered as the fringe benefit under

“s, 136 (1)”?

Rule:

The legislation of FBTAA 1986 says that fringe benefit is a type of benefit or

the payment that is paid to the employee but it is not the same as the wages or the

salaries that are paid to employees (Royalty 2015). The legislation of the FBTAA

1986 says that an employer only gives the employee with the fringe benefit during

the course of the employee’s employment. This successfully represents that the

benefit is given to the person since they are held as the employee.

The definition of employee entails that a person who is or will be entitled to

get the salary or wages or the benefits in lieu wages and the salaries. The word

benefit and the fringe benefit have larger meaning for the fringe benefit tax purpose.

benefit generally includes the privileges, rights and the services (Cooper 2018). The

fringe benefit tax liability falls on the employer. A person will be considered employer

for the purpose of fringe benefit tax if they make the payment to the employee,

company director or the office holder that will be subjected to the withholding

obligations or if they provide the benefit in lieu of such payments. As the employer,

they are required to pay the FBT irrespective of the whether they are the sole trader,

trustee or the partnership etc. This is irrespective of whether the employee or the

another party offers the fringe benefit. The fringe benefit tax is payable whether or

not they are liable to pay the other types of taxes namely the income tax.

Denoting the explanation that has been made in the

“s, 7-1, FBTAA 1986” that

the car fringe benefit commonly happens when they make the car they hold available

for the employee’s private usage or the car is being held as the available for the

employee’s private usage (Soled and Thomas 2016). A car they hold generally

implies that the they car are having under the ownership. The employer provides the

car to the employee for their private usage during any day of the employment that

the car is actually provided to the employee for their private purpose by the employer

or the car is made available to the employee for their private usage. A car is only

allowed to the private usage of the employee only when the car is not at their

premises and the employee is permitted to make the private use of the car (Barry

and Caron 2015). A car is said to be under the private ownership of the employee if

the car is garaged at the home of the employee.

As the common rule, travel from the place of work to the place of home is

considered as the private use of the vehicle. A car that is garaged at the employee

home is being held as being available for the private usage of the employee

irrespective of whether they are having permission of using the car for private

purpose (Briegel 2019). The taxable value of the car fringe benefit can be calculated

based on the statutory formula method or the operating cost method. With respect to

the statutory formula the statutory rate is multiplied with the car base value. On the

other hand, operating cost method explains that the taxable value of the car fringe

benefit represents the percentage of total cost of operating the car during fringe

benefit tax year.

Answer to question 1:

Issues:

Whether or not giving the car to the employee throughout the employment will

be considered as the fringe benefit under

“s, 136 (1)”?

Rule:

The legislation of FBTAA 1986 says that fringe benefit is a type of benefit or

the payment that is paid to the employee but it is not the same as the wages or the

salaries that are paid to employees (Royalty 2015). The legislation of the FBTAA

1986 says that an employer only gives the employee with the fringe benefit during

the course of the employee’s employment. This successfully represents that the

benefit is given to the person since they are held as the employee.

The definition of employee entails that a person who is or will be entitled to

get the salary or wages or the benefits in lieu wages and the salaries. The word

benefit and the fringe benefit have larger meaning for the fringe benefit tax purpose.

benefit generally includes the privileges, rights and the services (Cooper 2018). The

fringe benefit tax liability falls on the employer. A person will be considered employer

for the purpose of fringe benefit tax if they make the payment to the employee,

company director or the office holder that will be subjected to the withholding

obligations or if they provide the benefit in lieu of such payments. As the employer,

they are required to pay the FBT irrespective of the whether they are the sole trader,

trustee or the partnership etc. This is irrespective of whether the employee or the

another party offers the fringe benefit. The fringe benefit tax is payable whether or

not they are liable to pay the other types of taxes namely the income tax.

Denoting the explanation that has been made in the

“s, 7-1, FBTAA 1986” that

the car fringe benefit commonly happens when they make the car they hold available

for the employee’s private usage or the car is being held as the available for the

employee’s private usage (Soled and Thomas 2016). A car they hold generally

implies that the they car are having under the ownership. The employer provides the

car to the employee for their private usage during any day of the employment that

the car is actually provided to the employee for their private purpose by the employer

or the car is made available to the employee for their private usage. A car is only

allowed to the private usage of the employee only when the car is not at their

premises and the employee is permitted to make the private use of the car (Barry

and Caron 2015). A car is said to be under the private ownership of the employee if

the car is garaged at the home of the employee.

As the common rule, travel from the place of work to the place of home is

considered as the private use of the vehicle. A car that is garaged at the employee

home is being held as being available for the private usage of the employee

irrespective of whether they are having permission of using the car for private

purpose (Briegel 2019). The taxable value of the car fringe benefit can be calculated

based on the statutory formula method or the operating cost method. With respect to

the statutory formula the statutory rate is multiplied with the car base value. On the

other hand, operating cost method explains that the taxable value of the car fringe

benefit represents the percentage of total cost of operating the car during fringe

benefit tax year.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3TAXATION LAW

Application:

Upon learning the case facts, it is noted that a car was given by the Spiceco

Pty Ltd to the Lucinda for making the personal usage of car. It can be stated that the

car was given to Lucinda due to her employer and employee relationship.

Furthermore, the employer and employee relationship has been clearly satisfied by

Lucinda and Spiceco Pty Ltd. Under

“s, 7 (1), FBTAA 1986” the car fringe benefit has

originated for the Spiceco Pty Ltd since the car was given to Lucinda during the

course of the employment so that she can make the private use of the car (Givati

2015).

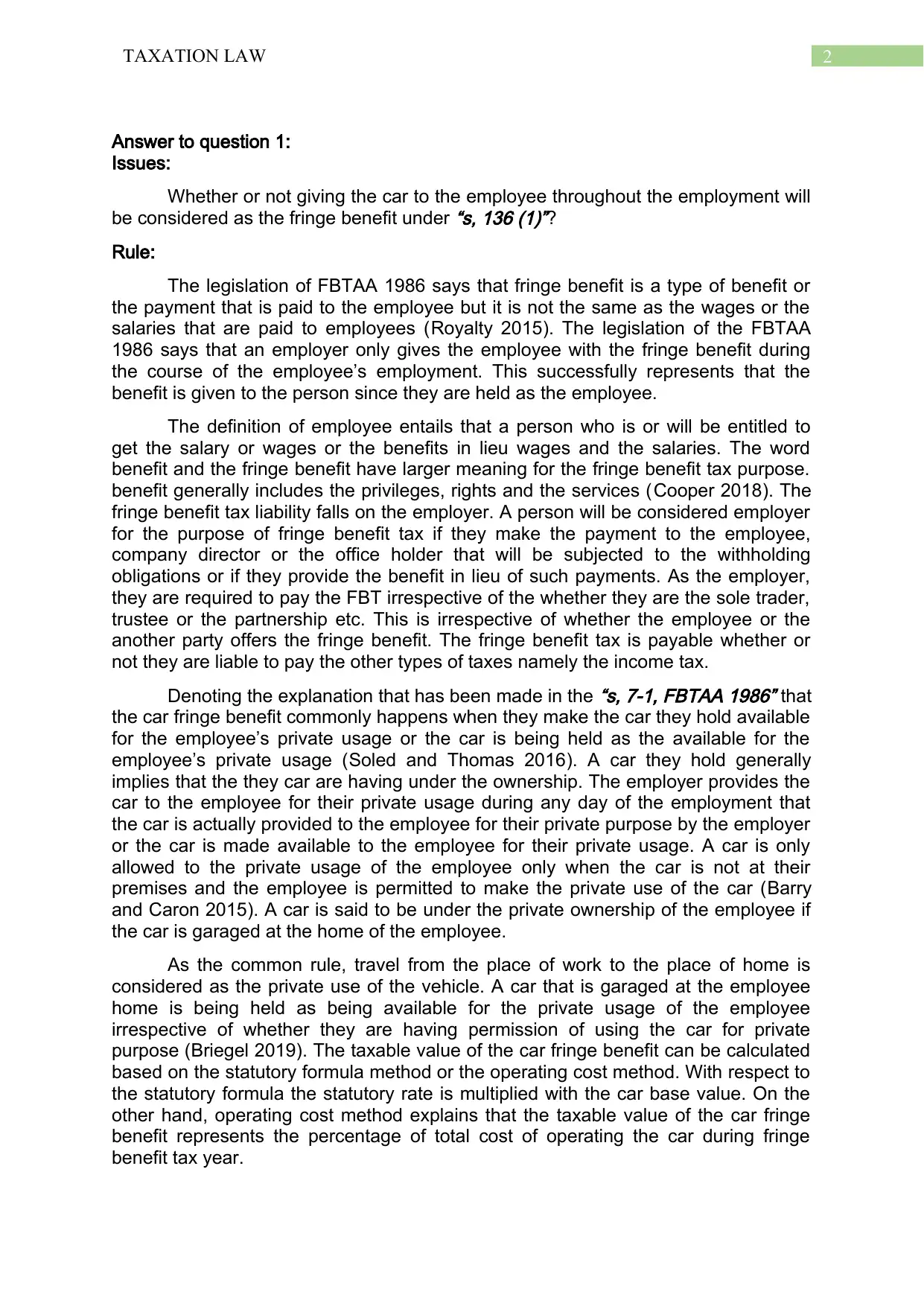

The employer here has exclusively made the car available for the Lucinda’s

personal usage when she was allowed to use it both travelling for the business as

well as employment purpose. The criteria of nexus among the benefit given to the

employee by the employer here is also satisfied (Vail 2016). As the guide to the

determine the taxable value of the car fringe benefit it is necessary to ascertain the

formula that needs to be applied in the case Spiceco Pty Ltd. Reference to the

“s, 9,

FBTAA 1986” has been made to compute the chargeable value of the fringe benefit

tax under the statutory formula for Specico Pty Ltd (Argente and García 2015). To

calculate the fringe benefit tax the statutory rate is applied and the rate is multiplied

with the base value of the car less the employee’s contribution made towards the car

during the year of FBT.

As evident from the above stated computation it is understood that the taxable

value of the car fringe benefit arises under statutory formula is $2,600. On the other

hand, the operating cost method has also been referred in the case of Specico Pty

Ltd where the records of log books and odometer reading of the car is referred to

calculate the taxable value of car fringe benefits.

Application:

Upon learning the case facts, it is noted that a car was given by the Spiceco

Pty Ltd to the Lucinda for making the personal usage of car. It can be stated that the

car was given to Lucinda due to her employer and employee relationship.

Furthermore, the employer and employee relationship has been clearly satisfied by

Lucinda and Spiceco Pty Ltd. Under

“s, 7 (1), FBTAA 1986” the car fringe benefit has

originated for the Spiceco Pty Ltd since the car was given to Lucinda during the

course of the employment so that she can make the private use of the car (Givati

2015).

The employer here has exclusively made the car available for the Lucinda’s

personal usage when she was allowed to use it both travelling for the business as

well as employment purpose. The criteria of nexus among the benefit given to the

employee by the employer here is also satisfied (Vail 2016). As the guide to the

determine the taxable value of the car fringe benefit it is necessary to ascertain the

formula that needs to be applied in the case Spiceco Pty Ltd. Reference to the

“s, 9,

FBTAA 1986” has been made to compute the chargeable value of the fringe benefit

tax under the statutory formula for Specico Pty Ltd (Argente and García 2015). To

calculate the fringe benefit tax the statutory rate is applied and the rate is multiplied

with the base value of the car less the employee’s contribution made towards the car

during the year of FBT.

As evident from the above stated computation it is understood that the taxable

value of the car fringe benefit arises under statutory formula is $2,600. On the other

hand, the operating cost method has also been referred in the case of Specico Pty

Ltd where the records of log books and odometer reading of the car is referred to

calculate the taxable value of car fringe benefits.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4TAXATION LAW

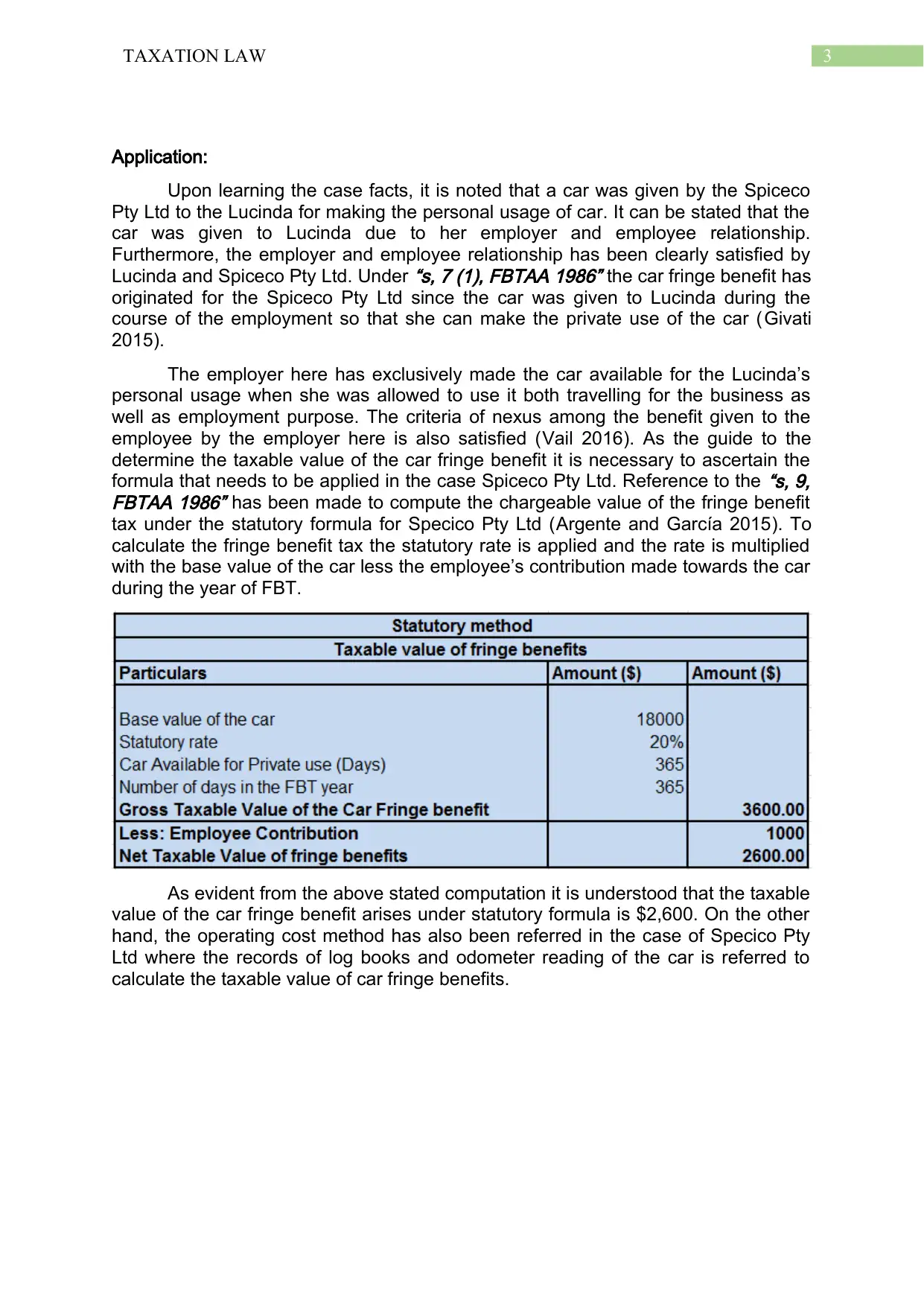

Deemed Depreciation:

Deemed Interest:

Fringe benefit tax liability:

Deemed Depreciation:

Deemed Interest:

Fringe benefit tax liability:

5TAXATION LAW

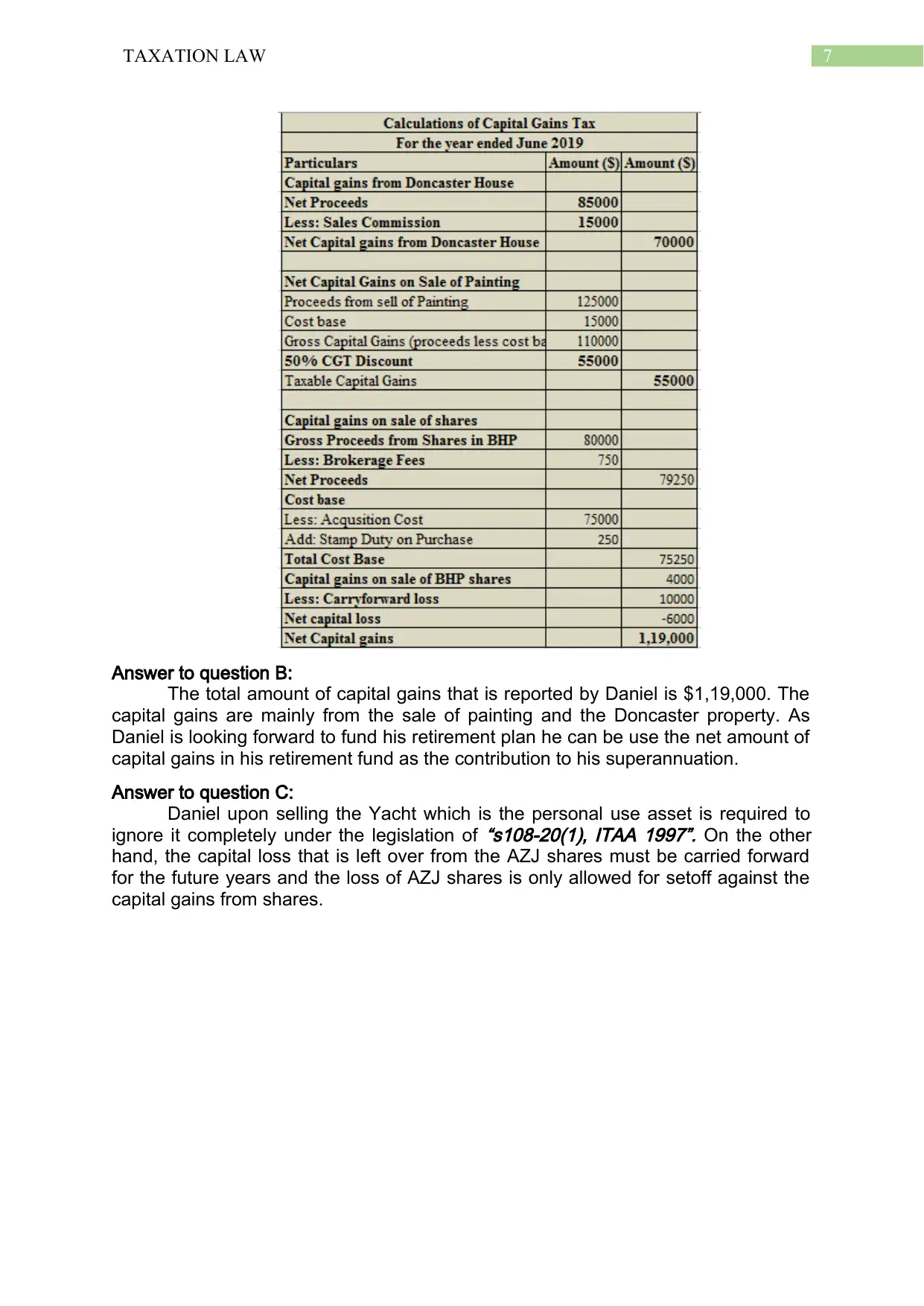

The calculation that is done above clearly shows that the under the statutory

method the net taxable amount of fringe benefit is $2,600. On the other hand, the net

taxable value of the fringe benefit under the operating cost method is $3,580.5.

Therefore, it can be stated that the statutory method should be used as the amount

of tax payable is lower under the statutory method.

Conclusion:

The case can be concluded by stating that the employer here Spiceco Pty Ltd

will be considered taxable for the value of car fringe benefit provided to Lucinda

during the course of the employment. The employer here is taxable under

“s, 7 (1),

FBTAA 1986”.

Answer to question 2:

Answer to question A:

If an individual sells the capital asset in the form of real estate or the shares,

they generally make the capital gains or the loss (Heim, Lurie and Simon 2015). This

represents the differences between what it cost to an individual to acquire the asset

and what they receive when they deposit the asset. An individual taxpayer is

required to report the capital gains and the losses in their income tax return and

should pay tax on the net capital gains. Even though it is referred as the capital gains

tax this is usually treated as the part of their income tax and not the separate tax.

When an individual makes the net capital gains, it is added into the taxable

income and might significantly increase the taxes they need to pay (Knepper 2018).

As the tax is not withheld for the capital gains purpose, an individual might want to

work out how majority of the tax that is owed and set aside the sufficient amount of

fund to cover the relevant amount.

Sale of Doncaster Property:

The CGT event H1 takes place if the deposit that is paid to the owner of the

property is forfeited due to the prospective sale or the other transactions that does

not proceed. Under the

“s-104.150, ITAA 1997” the forfeiture of deposit might include

the giving the property (Yagan 2015). The case facts that is obtained suggest that

Daniel has decided to sell the house in which he has lived for thirty years. Prior to

entering in the contract the prospective has paid Daniel a sum of $85,000 as the

deposit. The negotiations between Daniel and the prospective purchaser has failed

and the deposit is ultimately forfeited. The amount that is forfeited should be viewed

as capital gain for Daniel under

“s, 104.150, ITAA 1997” (Li, Lin and Robinson 2016).

The forfeiture of deposit by the prospective buyer has given rise to CGT event H1

and the amount is included into the assessable statutory income for Daniel.

Sale of Painting:

The CGT assets also includes the collectables. Under

“s, 118-10 to 108-17

ITAA 1997” a collectable is regarded as one of the item that is listed in

“s, 108-10

(2)” which is basically used or kept for the own use of taxpayer (Meidner, Hedborg

and Fond 2017). The collectables include the items such as antiques, artworks,

coins, rare stamps etc. While

“s, 118-10, ITAA 1997” explains that the capital gain or

the capital loss that is made by the taxpayer from the collectable is required to be

ignored if the first element of cost base is below $500. Daniel has the artistic painting

which he purchased in 1985 for $15,000. In the current tax year of 2019, Daniel sold

The calculation that is done above clearly shows that the under the statutory

method the net taxable amount of fringe benefit is $2,600. On the other hand, the net

taxable value of the fringe benefit under the operating cost method is $3,580.5.

Therefore, it can be stated that the statutory method should be used as the amount

of tax payable is lower under the statutory method.

Conclusion:

The case can be concluded by stating that the employer here Spiceco Pty Ltd

will be considered taxable for the value of car fringe benefit provided to Lucinda

during the course of the employment. The employer here is taxable under

“s, 7 (1),

FBTAA 1986”.

Answer to question 2:

Answer to question A:

If an individual sells the capital asset in the form of real estate or the shares,

they generally make the capital gains or the loss (Heim, Lurie and Simon 2015). This

represents the differences between what it cost to an individual to acquire the asset

and what they receive when they deposit the asset. An individual taxpayer is

required to report the capital gains and the losses in their income tax return and

should pay tax on the net capital gains. Even though it is referred as the capital gains

tax this is usually treated as the part of their income tax and not the separate tax.

When an individual makes the net capital gains, it is added into the taxable

income and might significantly increase the taxes they need to pay (Knepper 2018).

As the tax is not withheld for the capital gains purpose, an individual might want to

work out how majority of the tax that is owed and set aside the sufficient amount of

fund to cover the relevant amount.

Sale of Doncaster Property:

The CGT event H1 takes place if the deposit that is paid to the owner of the

property is forfeited due to the prospective sale or the other transactions that does

not proceed. Under the

“s-104.150, ITAA 1997” the forfeiture of deposit might include

the giving the property (Yagan 2015). The case facts that is obtained suggest that

Daniel has decided to sell the house in which he has lived for thirty years. Prior to

entering in the contract the prospective has paid Daniel a sum of $85,000 as the

deposit. The negotiations between Daniel and the prospective purchaser has failed

and the deposit is ultimately forfeited. The amount that is forfeited should be viewed

as capital gain for Daniel under

“s, 104.150, ITAA 1997” (Li, Lin and Robinson 2016).

The forfeiture of deposit by the prospective buyer has given rise to CGT event H1

and the amount is included into the assessable statutory income for Daniel.

Sale of Painting:

The CGT assets also includes the collectables. Under

“s, 118-10 to 108-17

ITAA 1997” a collectable is regarded as one of the item that is listed in

“s, 108-10

(2)” which is basically used or kept for the own use of taxpayer (Meidner, Hedborg

and Fond 2017). The collectables include the items such as antiques, artworks,

coins, rare stamps etc. While

“s, 118-10, ITAA 1997” explains that the capital gain or

the capital loss that is made by the taxpayer from the collectable is required to be

ignored if the first element of cost base is below $500. Daniel has the artistic painting

which he purchased in 1985 for $15,000. In the current tax year of 2019, Daniel sold

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6TAXATION LAW

the painting during the auction for $125,000. Consequently, it can be stated that the

painting has been classified as collectable under

“s, 108-10 (2)” (Faccio and Xu

2015)

. A CGT event A1 has happened when the painting was sold. So the capital

gain that is made from the painting will be liable for assessment within the provision

of capital gains tax.

Luxury Yacht:

A luxury yacht was sold by Daniel which he purchased back in 2004 for

$110,000. This should be noted that the yacht was sold by Daniel for $60,000 and

this has resulted in capital loss. The subdivision 108-C explains that the personal

use asset is mainly kept or used by the taxpayer for their own enjoyment. As per

“s,

108-20, ITAA 1997” the items of the personal use asset also include the boats,

furniture, and the household items (Alpanda and Zubairy 2016). On the other hand,

in the event of selling the personal use asset and incurring a capital loss, then the

taxpayers is not permitted to offset the capital loss against the capital gains. Under

the

“s108-20(1), ITAA 1997” the taxpayers are required to simply ignore the loss.

The taxpayer here Daniel has reported the capital loss from the Yacht which

is classified as the personal use asset under the

“s, 108-20, ITAA 1997” (Sikes and

Verrecchia 2016). Additionally, under

“s108-20(1), ITAA 1997” Daniel is required to

simply ignore the loss.

Sale of Shares:

Daniel held the shares of BHP that he has sold for $80,000. He additionally

incurred the brokerage fees on the shares. He bought it for $75,000 with stamp duty

paid of $250. The stamp duty will be included into the cost base of the shares. While

Daniel is required to subtract the brokerage fees from the sales value of shares. The

sale of BHP shares has yielded Daniel a capital gain. Furthermore, a capital loss is

bought forward from AZJ shares. The capital loss amounts to $10,000. The capital

loss is offset against the BHP shares while the rest of the capital loss is carried

forward to future years and it is only permitted for reduction from capital gains when

the future capital gains is reported from the sale of shares.

the painting during the auction for $125,000. Consequently, it can be stated that the

painting has been classified as collectable under

“s, 108-10 (2)” (Faccio and Xu

2015)

. A CGT event A1 has happened when the painting was sold. So the capital

gain that is made from the painting will be liable for assessment within the provision

of capital gains tax.

Luxury Yacht:

A luxury yacht was sold by Daniel which he purchased back in 2004 for

$110,000. This should be noted that the yacht was sold by Daniel for $60,000 and

this has resulted in capital loss. The subdivision 108-C explains that the personal

use asset is mainly kept or used by the taxpayer for their own enjoyment. As per

“s,

108-20, ITAA 1997” the items of the personal use asset also include the boats,

furniture, and the household items (Alpanda and Zubairy 2016). On the other hand,

in the event of selling the personal use asset and incurring a capital loss, then the

taxpayers is not permitted to offset the capital loss against the capital gains. Under

the

“s108-20(1), ITAA 1997” the taxpayers are required to simply ignore the loss.

The taxpayer here Daniel has reported the capital loss from the Yacht which

is classified as the personal use asset under the

“s, 108-20, ITAA 1997” (Sikes and

Verrecchia 2016). Additionally, under

“s108-20(1), ITAA 1997” Daniel is required to

simply ignore the loss.

Sale of Shares:

Daniel held the shares of BHP that he has sold for $80,000. He additionally

incurred the brokerage fees on the shares. He bought it for $75,000 with stamp duty

paid of $250. The stamp duty will be included into the cost base of the shares. While

Daniel is required to subtract the brokerage fees from the sales value of shares. The

sale of BHP shares has yielded Daniel a capital gain. Furthermore, a capital loss is

bought forward from AZJ shares. The capital loss amounts to $10,000. The capital

loss is offset against the BHP shares while the rest of the capital loss is carried

forward to future years and it is only permitted for reduction from capital gains when

the future capital gains is reported from the sale of shares.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7TAXATION LAW

Answer to question B:

The total amount of capital gains that is reported by Daniel is $1,19,000. The

capital gains are mainly from the sale of painting and the Doncaster property. As

Daniel is looking forward to fund his retirement plan he can be use the net amount of

capital gains in his retirement fund as the contribution to his superannuation.

Answer to question C:

Daniel upon selling the Yacht which is the personal use asset is required to

ignore it completely under the legislation of

“s108-20(1), ITAA 1997”. On the other

hand, the capital loss that is left over from the AZJ shares must be carried forward

for the future years and the loss of AZJ shares is only allowed for setoff against the

capital gains from shares.

Answer to question B:

The total amount of capital gains that is reported by Daniel is $1,19,000. The

capital gains are mainly from the sale of painting and the Doncaster property. As

Daniel is looking forward to fund his retirement plan he can be use the net amount of

capital gains in his retirement fund as the contribution to his superannuation.

Answer to question C:

Daniel upon selling the Yacht which is the personal use asset is required to

ignore it completely under the legislation of

“s108-20(1), ITAA 1997”. On the other

hand, the capital loss that is left over from the AZJ shares must be carried forward

for the future years and the loss of AZJ shares is only allowed for setoff against the

capital gains from shares.

8TAXATION LAW

References:

Alpanda, S. and Zubairy, S., 2016. Housing and tax policy.

Journal of Money, Credit

and Banking,

48(2-3), pp.485-512.

Argente, D. and García, J.L., 2015. The price of fringe benefits when formal and

informal labor markets coexist.

IZA Journal of Labor Economics,

4(1), p.1.

Barry, J.M. and Caron, P.L., 2015. Tax regulation, transportation innovation, and the

sharing economy.

U. Chi. L. Rev. Dialogue,

82, p.69.

Briegel, J., 2019. The Effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on Small

Businesses.

Journal of Financial Service Professionals,

73(1).

Cooper, R., 2018. Recent changes to fringe benefits.

TAXtalk,

2018(71), pp.52-55.

Faccio, M. and Xu, J., 2015. Taxes and capital structure.

Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis,

50(3), pp.277-300.

Givati, Y., 2015. Googling a Free Lunch: The Taxation of Fringe Benefits.

Tax L.

Rev.,

69, p.275.

Heim, B., Lurie, I. and Simon, K., 2015. The impact of the affordable care act young

adult provision on labor market outcomes: evidence from tax data.

Tax Policy and

Economy,

29(1), pp.133-157.

Knepper, M., 2018. From the Fringe to the Fore: Labor Unions and Employee

Compensation.

Review of Economics and Statistics, (0).

Li, O.Z., Lin, Y. and Robinson, J.R., 2016. The effect of capital gains taxes on the

initial pricing and underpricing of IPOs.

Journal of Accounting and Economics,

61(2-

3), pp.465-485.

Meidner, R., Hedborg, A. and Fond, G., 2017.

Employee investment funds: An

approach to collective capital formation. Routledge.

Royalty, A.B., 2015. Tax preferences for fringe benefits and workers’ eligibility for

employer health insurance.

Journal of Public Economics,

75(2), pp.209-227.

Sikes, S.A. and Verrecchia, R., 2016. Aggregate corporate tax avoidance and cost of

capital.

Work in progress, University of Pennsylvania.

Soled, J.A. and Thomas, K.D., 2016. Revisiting the Taxation of Fringe

Benefits.

Wash. L. Rev.,

91, p.761.

Vail, S.J., 2016. Slapping the Hand at the Dinner Table: A Practical Tax Solution to

Employer-Provided Meal Benefits.

U. Ill. L. Rev., p.689.

Yagan, D., 2015. Capital tax reform and the real economy: The effects of the 2003

dividend tax cut.

American Economic Review,

105(12), pp.3531-63.

References:

Alpanda, S. and Zubairy, S., 2016. Housing and tax policy.

Journal of Money, Credit

and Banking,

48(2-3), pp.485-512.

Argente, D. and García, J.L., 2015. The price of fringe benefits when formal and

informal labor markets coexist.

IZA Journal of Labor Economics,

4(1), p.1.

Barry, J.M. and Caron, P.L., 2015. Tax regulation, transportation innovation, and the

sharing economy.

U. Chi. L. Rev. Dialogue,

82, p.69.

Briegel, J., 2019. The Effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on Small

Businesses.

Journal of Financial Service Professionals,

73(1).

Cooper, R., 2018. Recent changes to fringe benefits.

TAXtalk,

2018(71), pp.52-55.

Faccio, M. and Xu, J., 2015. Taxes and capital structure.

Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis,

50(3), pp.277-300.

Givati, Y., 2015. Googling a Free Lunch: The Taxation of Fringe Benefits.

Tax L.

Rev.,

69, p.275.

Heim, B., Lurie, I. and Simon, K., 2015. The impact of the affordable care act young

adult provision on labor market outcomes: evidence from tax data.

Tax Policy and

Economy,

29(1), pp.133-157.

Knepper, M., 2018. From the Fringe to the Fore: Labor Unions and Employee

Compensation.

Review of Economics and Statistics, (0).

Li, O.Z., Lin, Y. and Robinson, J.R., 2016. The effect of capital gains taxes on the

initial pricing and underpricing of IPOs.

Journal of Accounting and Economics,

61(2-

3), pp.465-485.

Meidner, R., Hedborg, A. and Fond, G., 2017.

Employee investment funds: An

approach to collective capital formation. Routledge.

Royalty, A.B., 2015. Tax preferences for fringe benefits and workers’ eligibility for

employer health insurance.

Journal of Public Economics,

75(2), pp.209-227.

Sikes, S.A. and Verrecchia, R., 2016. Aggregate corporate tax avoidance and cost of

capital.

Work in progress, University of Pennsylvania.

Soled, J.A. and Thomas, K.D., 2016. Revisiting the Taxation of Fringe

Benefits.

Wash. L. Rev.,

91, p.761.

Vail, S.J., 2016. Slapping the Hand at the Dinner Table: A Practical Tax Solution to

Employer-Provided Meal Benefits.

U. Ill. L. Rev., p.689.

Yagan, D., 2015. Capital tax reform and the real economy: The effects of the 2003

dividend tax cut.

American Economic Review,

105(12), pp.3531-63.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.