Literature Review: Understanding the Team Work Engagement Model

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/25

|23

|15736

|251

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review delves into the concept of team work engagement, addressing the gap in existing research by presenting a model for its emergence within the context of team dynamics. It highlights the relevance of both individual and team-level work engagement to employee performance and well-being, emphasizing the absence of a comprehensive theoretical framework that integrates team processes. The proposed model considers team inputs, outputs, and mediators as predictors of team work engagement, acknowledging their recursive influences over time. By embedding the model within the broader literature on teams and teamwork, the review strengthens the theoretical conceptualization of work engagement at the team level, distinguishes it from individual work engagement, and sets the stage for future empirical research and intervention design. The review also touches on the job demands-resources model and affective events theory, suggesting that shared experiences and norms within teams can lead to convergent affective, cognitive, and motivational states, ultimately influencing team work engagement.

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology (2014), 87, 414–436

© 2014 The British PsychologicalSociety

www.wileyonlinelibrary.com

Team work engagement: A model of emergence

Patrıcia L. Costa1*, Ana M. Passos1 and Arnold B. Bakker2

1ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon, Portugal

2Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Research has shown that work engagement,both at the individualand team levels,is

relevant to understand employee performance and well-being. Nonetheless, there is no

theoretical model that explains the development of work engagement in teams that takes

into consideration what is already known about team dynamics and processes. This study

addresses this gap in the literature, presenting a model for the emergence of team work

engagement. The model proposes team inputs, outputs, and mediators as predictors of

team work engagementand highlightstheir recursive influencesover time.This

conceptualwork providesa startingpoint for furtherresearch on team work

engagement, allowing for distinguishing individual and team constructs.

Practitioner points

The degree of energy and enthusiasm of teams depends on the way they interact.

The affective and motivationaldynamics ofteams have consequences for their performance and

well-being.

The emergence of team work engagement is better understood within the literature of teamwork

The last decade has established work engagement as an important construct for both

employee performance and well-being (Halbesleben, 2010). Engaged employees display

positive attitude towards work and high energy levels,which leads them to actively

intervene in their work environment.They tend to show high levels ofself-efficacy

(Bakker, 2009) and organizational commitment (Demerouti, Bakker, De Jonge, Janssen, &

Schaufeli, 2001). In addition, engaged workers are inclined to work extra hours (Schaufe

Taris, & Van Rhenen, 2008) and help their colleagues if needed (Halbesleben & Wheeler,

2008); they also manage to stay healthy in stressful environments (Demerouti, Bakker,

Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001).

Parallel to the studies on work engagement at the individual level, some researchers

have also started to explore the construct at the team level(Bakker,van Emmerik,&

Euwema, 2006; Salanova, Llorens, Cifre, Martinez, & Schaufeli, 2003; Torrente, Salanova

Llorens,& Schaufeli,2012a,b).These studies suggestthat,at the team level,work

engagementhas positive relationshipswith task and team performance,collective

positive affect, and efficacy beliefs. Team work engagement is also positively related to

individual work engagement.

Despite the acknowledgement of its relevance in the context of work teams, the vast

majority of studies have not presented a theoreticalmodelframing the construct and

*Correspondence should be addressed to Patrıcia L.Costa,Av.Das Forcßas Armadas,Edifıcio ISCTE,Room 2w8,1649-026

Lisbon, Portugal (email: patricia_costa@iscte.pt).

DOI:10.1111/joop.12057

414

© 2014 The British PsychologicalSociety

www.wileyonlinelibrary.com

Team work engagement: A model of emergence

Patrıcia L. Costa1*, Ana M. Passos1 and Arnold B. Bakker2

1ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon, Portugal

2Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Research has shown that work engagement,both at the individualand team levels,is

relevant to understand employee performance and well-being. Nonetheless, there is no

theoretical model that explains the development of work engagement in teams that takes

into consideration what is already known about team dynamics and processes. This study

addresses this gap in the literature, presenting a model for the emergence of team work

engagement. The model proposes team inputs, outputs, and mediators as predictors of

team work engagementand highlightstheir recursive influencesover time.This

conceptualwork providesa startingpoint for furtherresearch on team work

engagement, allowing for distinguishing individual and team constructs.

Practitioner points

The degree of energy and enthusiasm of teams depends on the way they interact.

The affective and motivationaldynamics ofteams have consequences for their performance and

well-being.

The emergence of team work engagement is better understood within the literature of teamwork

The last decade has established work engagement as an important construct for both

employee performance and well-being (Halbesleben, 2010). Engaged employees display

positive attitude towards work and high energy levels,which leads them to actively

intervene in their work environment.They tend to show high levels ofself-efficacy

(Bakker, 2009) and organizational commitment (Demerouti, Bakker, De Jonge, Janssen, &

Schaufeli, 2001). In addition, engaged workers are inclined to work extra hours (Schaufe

Taris, & Van Rhenen, 2008) and help their colleagues if needed (Halbesleben & Wheeler,

2008); they also manage to stay healthy in stressful environments (Demerouti, Bakker,

Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001).

Parallel to the studies on work engagement at the individual level, some researchers

have also started to explore the construct at the team level(Bakker,van Emmerik,&

Euwema, 2006; Salanova, Llorens, Cifre, Martinez, & Schaufeli, 2003; Torrente, Salanova

Llorens,& Schaufeli,2012a,b).These studies suggestthat,at the team level,work

engagementhas positive relationshipswith task and team performance,collective

positive affect, and efficacy beliefs. Team work engagement is also positively related to

individual work engagement.

Despite the acknowledgement of its relevance in the context of work teams, the vast

majority of studies have not presented a theoreticalmodelframing the construct and

*Correspondence should be addressed to Patrıcia L.Costa,Av.Das Forcßas Armadas,Edifıcio ISCTE,Room 2w8,1649-026

Lisbon, Portugal (email: patricia_costa@iscte.pt).

DOI:10.1111/joop.12057

414

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

explicating the mechanisms responsible for its existence.This is one major gap in the

work engagement literature. The one commendable exception is the work by Torre

et al. (2012b)that proposes team socialresources (supportive team climate,team

work and coordination) as possible antecedents of team work engagement. The lat

idea is tightly linked to the literature on individual work engagement and rooted in

job demands–resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), the conceptual model f

individual work engagement. To our knowledge, there have been no scholars reflec

on whetherand how team work engagementcan be equated within the specific

literature on groups and teams,1 teamwork, and team effectiveness, which would allow

for a betterunderstanding ofteamwork,and create the theoreticalrationale for

studying team work engagement.The goalof this study is to present a modelfor the

emergence of team work engagement, embedded in the literature on teams. It pro

a theoreticalmodelfor the emergence ofthe collective constructthataccounts for

both team inputs and outputsand for team processes,highlighting theirdynamic

interplay overtime.

The dialogue between the two domains of individualwork engagement and team

effectiveness contributes to severalpositive outcomes.First, it will strengthen the

theoretical conceptualization of work engagement at the team level, accounting for

is already known in terms of team functioning and enriching its nomological networ

Second,it will address legitimate concerns related to eventualconstruct proliferation

(Cole, Walter, Bedeian,& O’Boyle, 2012), distinguishing team work engagement from

otherteam-levelconstructs and from individualwork engagement,by presenting a

specific team-level model of engagement. Third, this article will set the stage for fu

research on work engagement in teams, providing a model that may be tested emp

Finally, it will allow for importing the knowledge acquired by team scholars in desig

interventions to foster collective engagement.

Work engagement

Work engagementis a positive,fulfilling state ofwork-related well-being.Following

Shaufeli and Bakker (2010), we define work engagement as an affective–cognitive

characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption. Engaged employees are energ

and enthusiastic about their work, which leads them to perform better than non-en

employees, and to invest more effort in work than is formally expected (Halbeslebe

Wheeler,2008).The most often used framework for studying engagement is the job

demands–resources model (Bakker, 2011; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Studies usin

model have shown that job demands and resources trigger two different psycholog

processes that are the roots of work engagement and burnout:an energy impairment

process caused by excessive job demands and a positive motivationalprocess that is

triggered by job resources.Job resources such as performance feedback,job control/

autonomy, and supervisory support are then conceptualized as the major antecede

work engagement (Hakanen, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2006; Richardsen, Burke, & Mart

sen, 2006; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), and they appear to enhance engagement esp

when job demands are high (Bakker, Hakanen, Demerouti, & Xanthopoulou, 2007).

addition to job resources,personalresources have also been found to predictwork

engagement (Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2007). Examples of th

1Following the work by Guzzo and Dickson (1996), we use the terms groups and teams interchangeably

Team work engagement415

work engagement literature. The one commendable exception is the work by Torre

et al. (2012b)that proposes team socialresources (supportive team climate,team

work and coordination) as possible antecedents of team work engagement. The lat

idea is tightly linked to the literature on individual work engagement and rooted in

job demands–resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), the conceptual model f

individual work engagement. To our knowledge, there have been no scholars reflec

on whetherand how team work engagementcan be equated within the specific

literature on groups and teams,1 teamwork, and team effectiveness, which would allow

for a betterunderstanding ofteamwork,and create the theoreticalrationale for

studying team work engagement.The goalof this study is to present a modelfor the

emergence of team work engagement, embedded in the literature on teams. It pro

a theoreticalmodelfor the emergence ofthe collective constructthataccounts for

both team inputs and outputsand for team processes,highlighting theirdynamic

interplay overtime.

The dialogue between the two domains of individualwork engagement and team

effectiveness contributes to severalpositive outcomes.First, it will strengthen the

theoretical conceptualization of work engagement at the team level, accounting for

is already known in terms of team functioning and enriching its nomological networ

Second,it will address legitimate concerns related to eventualconstruct proliferation

(Cole, Walter, Bedeian,& O’Boyle, 2012), distinguishing team work engagement from

otherteam-levelconstructs and from individualwork engagement,by presenting a

specific team-level model of engagement. Third, this article will set the stage for fu

research on work engagement in teams, providing a model that may be tested emp

Finally, it will allow for importing the knowledge acquired by team scholars in desig

interventions to foster collective engagement.

Work engagement

Work engagementis a positive,fulfilling state ofwork-related well-being.Following

Shaufeli and Bakker (2010), we define work engagement as an affective–cognitive

characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption. Engaged employees are energ

and enthusiastic about their work, which leads them to perform better than non-en

employees, and to invest more effort in work than is formally expected (Halbeslebe

Wheeler,2008).The most often used framework for studying engagement is the job

demands–resources model (Bakker, 2011; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Studies usin

model have shown that job demands and resources trigger two different psycholog

processes that are the roots of work engagement and burnout:an energy impairment

process caused by excessive job demands and a positive motivationalprocess that is

triggered by job resources.Job resources such as performance feedback,job control/

autonomy, and supervisory support are then conceptualized as the major antecede

work engagement (Hakanen, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2006; Richardsen, Burke, & Mart

sen, 2006; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), and they appear to enhance engagement esp

when job demands are high (Bakker, Hakanen, Demerouti, & Xanthopoulou, 2007).

addition to job resources,personalresources have also been found to predictwork

engagement (Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2007). Examples of th

1Following the work by Guzzo and Dickson (1996), we use the terms groups and teams interchangeably

Team work engagement415

personal resources are personality traits, such as high extraversion and low neuroticism

(Langelaan,Bakker,Schaufeli,& Van Doornen,2006),and lower-orderpersonality

characteristicsincluding self-efficacy,optimism,hope, and resilience (Sweetman &

Luthans, 2010; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

Thus, work engagementis particularlyinfluenced byresourcesin the work

environmentand in the person. These resourceshave the strongestimpact on

engagement when job demands are high.Work engagement,in turn,is an important

predictor of positive attitudes towards the organization and job performance. In other

words, engagement mediates the impact of job and personal resources on organizationa

outcomes (Shaufeli& Bakker,2010),such as organizationalcommitment,personal

initiative, and extra-role behaviour (Bakker, Demerouti, & Verbeke, 2004).

Team work engagement

Teams are ‘a distinguishable setof two or more people who interact,dynamically,

interdependently, and adaptively towards a common and valued goal/objective/mission,

who have been assigned specific roles or functions to perform, and who have a limited

lifespan ofmembership’(Salas,Dickinson,Converse,& Tannenbaum,1992,p. 4).

Working in a team hasspecificitiesthat distinguish itfrom working alone.Team

members need to coordinate and synchronize their actions,and every member has a

critical role for their collective action. Consequently, the success of teams is dependent

on the way team members interact with each other to accomplish the work (Marks,

Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001).

These majordifferences between working alone and working in a team should

account for conceptualizing work engagement and team work engagement differently.

Whereas individualwork engagementis essentially dependenton job resources and

demands,team work engagement,as a collective construct,is dependenton the

individual actions and cycles of interaction responsible for creating a shared pattern of

behaviour (Morgeson & Hofmann, 1999). Therefore, with the same resources and in an

equally challenging environment, some teams might develop a higher level of engageme

than others,because the affective,cognitive,and motivationaloutcomes ofdifferent

patterns of interaction are likely to be different.Commenting enthusiastically on new

equipment or energetically inciting team members to suggest new marketing strategies

after the entrance ofa new competitor in the marketis significantly differentfrom

neutrally informing team members ofthat same equipmentacquisition and angrily

referring to that new competitor.

Despite these variances, the existing research on team work engagement has failed

to incorporate these team phenomena and processes. Studies either do not account for

the differences between individual and team work engagement, or do not put forward

specific team-level models of engagement. For example, Tyler and Blader (2003) depart

from the engagement definition developed by Kahn (1990) – engaged employees bring

their fullaffective,physical,and cognitive self to the workplace – and propose that a

strong identification with the group will lead members to invest personal energy to aid

group success.This identification,in turn, depends on the respectand pride team

members have for their team.Tyler and Blader’s proposalon group engagementis

heavily based on social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and does not present any

distinctive features of team work engagement that represent specific team dynamics.

Early studies such as the one by Salanova et al.(2003) and the one by Bakker et al.

416 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

(Langelaan,Bakker,Schaufeli,& Van Doornen,2006),and lower-orderpersonality

characteristicsincluding self-efficacy,optimism,hope, and resilience (Sweetman &

Luthans, 2010; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

Thus, work engagementis particularlyinfluenced byresourcesin the work

environmentand in the person. These resourceshave the strongestimpact on

engagement when job demands are high.Work engagement,in turn,is an important

predictor of positive attitudes towards the organization and job performance. In other

words, engagement mediates the impact of job and personal resources on organizationa

outcomes (Shaufeli& Bakker,2010),such as organizationalcommitment,personal

initiative, and extra-role behaviour (Bakker, Demerouti, & Verbeke, 2004).

Team work engagement

Teams are ‘a distinguishable setof two or more people who interact,dynamically,

interdependently, and adaptively towards a common and valued goal/objective/mission,

who have been assigned specific roles or functions to perform, and who have a limited

lifespan ofmembership’(Salas,Dickinson,Converse,& Tannenbaum,1992,p. 4).

Working in a team hasspecificitiesthat distinguish itfrom working alone.Team

members need to coordinate and synchronize their actions,and every member has a

critical role for their collective action. Consequently, the success of teams is dependent

on the way team members interact with each other to accomplish the work (Marks,

Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001).

These majordifferences between working alone and working in a team should

account for conceptualizing work engagement and team work engagement differently.

Whereas individualwork engagementis essentially dependenton job resources and

demands,team work engagement,as a collective construct,is dependenton the

individual actions and cycles of interaction responsible for creating a shared pattern of

behaviour (Morgeson & Hofmann, 1999). Therefore, with the same resources and in an

equally challenging environment, some teams might develop a higher level of engageme

than others,because the affective,cognitive,and motivationaloutcomes ofdifferent

patterns of interaction are likely to be different.Commenting enthusiastically on new

equipment or energetically inciting team members to suggest new marketing strategies

after the entrance ofa new competitor in the marketis significantly differentfrom

neutrally informing team members ofthat same equipmentacquisition and angrily

referring to that new competitor.

Despite these variances, the existing research on team work engagement has failed

to incorporate these team phenomena and processes. Studies either do not account for

the differences between individual and team work engagement, or do not put forward

specific team-level models of engagement. For example, Tyler and Blader (2003) depart

from the engagement definition developed by Kahn (1990) – engaged employees bring

their fullaffective,physical,and cognitive self to the workplace – and propose that a

strong identification with the group will lead members to invest personal energy to aid

group success.This identification,in turn, depends on the respectand pride team

members have for their team.Tyler and Blader’s proposalon group engagementis

heavily based on social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and does not present any

distinctive features of team work engagement that represent specific team dynamics.

Early studies such as the one by Salanova et al.(2003) and the one by Bakker et al.

416 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

(2006) lack a clear definition of the team-level construct. The first one frames team

engagement as a ‘positive aspect of collective well-being in work groups’(p. 48) and

analyses the results considering the three dimensions of individualwork engagement:

vigour,dedication,and absorption.The second one measures collective engagement

with the individual-levelscale (Schaufeli& Bakker, 2003),and the percentage of

engaged employees per team is used as a representation of collective engagement

absence of a team-specific definition,framed by the knowledge from the literature on

teams, may lead researchers to question whether team work engagement does exi

distinct construct from work engagement.

Nonetheless, work engagement is likely to be relevant at the team level, as a mo

motivational construct that comprises affective and cognitive components. Accoun

for individualtraitdifferences,work events and the work environmentare likely to

influence team members in a similar way, not only in terms of the affective experie

but also in what motivation is concerned.Team membersusually share the same

resources,the same team leader,the same customers,the same events,the same

co-workers, and even the same workspace. According to affective events theory (W

Cropanzano,1996),it is likely that people experiencing the same events have similar

affective experiences. Some evidence has been reported on mood convergence be

people who work together: group affective tone (George, 1996), mood linkage (Trot

Kellett, & Briner, 1998), or emotional contagion (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 199

Norms of emotional expression (Sutton, 1991), that are conveyed to everyone in th

team, may also be considered relevant for the emergence of a common affective st

facilitating (‘everyone should be cheerful and energetic’) or inhibiting (‘we do not ta

aboutour feelings,good or bad’) its development.Finally,severaltheories ofwork

motivation highlight the interaction of person and situation,arguing that some work

characteristics might foster motivation (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Lawler, 1994). W

sharing working characteristics,it is likely,then,that the levelof motivation of team

members will converge.

Considering these ideas, it is not unlikely that team members develop similar aff

cognitive,and motivationalstates.However,should researchers consider thatwork

engagementat the team levelis qualitatively differentthan the weighted mean of

individual work engagement?

Some authors have already started to consider certain dynamics and variables t

characterize engagement at the team level. Bakker, Albrecht, and Leiter (2011) pro

that collective engagement refers to the engagement of the team/group (team vigo

team dedication, and team absorption), as perceived by individual employees and

might exist due to emotional contagion (Hatfield et al., 1994) among team membe

perspective on team work engagement highlights essentially an affective dimensio

the collective construct, and not so much a cognitive or motivational one. Torrente

(2012a) also state that emotionalcontagion could be the mechanism underlying team

work engagement. They further propose a specific definition of team work engagem

as a positive, fulfilling, work-related, and shared psychological state characterized b

vigour, dedication, and absorption. Through structural equation modelling, and usin

teams from 13 organizations, they reported evidence for a mediation role of team w

engagement between social resources (supportive team climate, coordination, and

work) and team performance, as assessed by the supervisor. This model is the first

accounts for team-level variables in explaining the existence of team work engagem

and for its relationship with team performance. Even so, previous research had alre

linked some social resources with individual work engagement. For example, Hakan

Team work engagement417

engagement as a ‘positive aspect of collective well-being in work groups’(p. 48) and

analyses the results considering the three dimensions of individualwork engagement:

vigour,dedication,and absorption.The second one measures collective engagement

with the individual-levelscale (Schaufeli& Bakker, 2003),and the percentage of

engaged employees per team is used as a representation of collective engagement

absence of a team-specific definition,framed by the knowledge from the literature on

teams, may lead researchers to question whether team work engagement does exi

distinct construct from work engagement.

Nonetheless, work engagement is likely to be relevant at the team level, as a mo

motivational construct that comprises affective and cognitive components. Accoun

for individualtraitdifferences,work events and the work environmentare likely to

influence team members in a similar way, not only in terms of the affective experie

but also in what motivation is concerned.Team membersusually share the same

resources,the same team leader,the same customers,the same events,the same

co-workers, and even the same workspace. According to affective events theory (W

Cropanzano,1996),it is likely that people experiencing the same events have similar

affective experiences. Some evidence has been reported on mood convergence be

people who work together: group affective tone (George, 1996), mood linkage (Trot

Kellett, & Briner, 1998), or emotional contagion (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 199

Norms of emotional expression (Sutton, 1991), that are conveyed to everyone in th

team, may also be considered relevant for the emergence of a common affective st

facilitating (‘everyone should be cheerful and energetic’) or inhibiting (‘we do not ta

aboutour feelings,good or bad’) its development.Finally,severaltheories ofwork

motivation highlight the interaction of person and situation,arguing that some work

characteristics might foster motivation (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Lawler, 1994). W

sharing working characteristics,it is likely,then,that the levelof motivation of team

members will converge.

Considering these ideas, it is not unlikely that team members develop similar aff

cognitive,and motivationalstates.However,should researchers consider thatwork

engagementat the team levelis qualitatively differentthan the weighted mean of

individual work engagement?

Some authors have already started to consider certain dynamics and variables t

characterize engagement at the team level. Bakker, Albrecht, and Leiter (2011) pro

that collective engagement refers to the engagement of the team/group (team vigo

team dedication, and team absorption), as perceived by individual employees and

might exist due to emotional contagion (Hatfield et al., 1994) among team membe

perspective on team work engagement highlights essentially an affective dimensio

the collective construct, and not so much a cognitive or motivational one. Torrente

(2012a) also state that emotionalcontagion could be the mechanism underlying team

work engagement. They further propose a specific definition of team work engagem

as a positive, fulfilling, work-related, and shared psychological state characterized b

vigour, dedication, and absorption. Through structural equation modelling, and usin

teams from 13 organizations, they reported evidence for a mediation role of team w

engagement between social resources (supportive team climate, coordination, and

work) and team performance, as assessed by the supervisor. This model is the first

accounts for team-level variables in explaining the existence of team work engagem

and for its relationship with team performance. Even so, previous research had alre

linked some social resources with individual work engagement. For example, Hakan

Team work engagement417

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

et al. (2006) report higher levels of work engagement in Finnish teachers with high level

of social resources, such as supportive social climate. Schaufeli, Bakker, and Van Rhenen

(2009) replicated this finding among managers from a Dutch telecom company in a

longitudinalstudy.These findings suggest thatsocialresources are notan exclusive

antecedentof team work engagement.Also,Torrente et al.’s (2012b) modelfails to

integrate whatwe already know aboutteam processes and team effectiveness,and

essentially represents a homologous (Kozlowski& Klein, 2000) transposition ofthe

individual-level model of engagement, therefore overlooking possible important differ-

ences between levels.

Overall, previous research on work engagement in teams has some limitations. Most

studies do not present a clear definition of the construct or a theoretical model for team

work engagement that accounts for variables exclusively relevant in the context of team

Even when considering team-relevant variables and team members’ interaction, researc

on team work engagement has not yet been integrated within the specific literature on

teams. In the next section, we attempt to overcome these limitations, by presenting a

model for team work engagement emergence based on the existing team effectiveness

literature.

Defining team work engagement

Team work engagement is as a shared,positive and fulfilling,motivationalemergent

state of work-related well-being. Just like individual-level work engagement (Schaufeli &

Bakker,2004;Shaufeli& Bakker,2010),team work engagementis proposed as a

multidimensionalconstruct characterized by affective and cognitive dimensions:team

vigour,team dedication,and team absorption.Team vigour stands for high levels of

energy and for an expression of willingness to invest effort in work and persistence in

the face ofdifficulties (e.g.,conflict,bad performance feedback);for example,team

members enthusiastically encourage demoralized colleagues and explicitly express their

desire to continue working.Team dedication is a shared strong involvement in work

and an expression ofa sense of significance,enthusiasm,inspiration,pride, and

challenge while doing so; for example, team members talk to each other and to others

(external to the team) about the importance of their work and about the thrill they feel

concerning theirwork. Team absorption represents a shared focused attention on

work, whereby team members experience and express difficulties detaching them-

selvesfrom work, such as team memberstalk about their work during breaks,

commenting on time passing quickly, and not engaging in non-work-related interactions

when working.

Keeping functional equivalence with the work engagement definition proposed by

Schaufeli and Bakker (2003), this emergent state will lead to team effectiveness. Howev

this definition allows for the conceptualization of a different construct’s structure, based

on the interaction patterns among the team members and reflects two essential constru

rooted in the literature on teams and teamwork: emergent states and shared constructs

Emergent states

Whereas Torrente et al. (2012b) define team work engagement as a shared psychologica

state, we propose that team work engagement is an emergent state, something that is

exclusive to teams and cannot be found in individuals. The idea of an emergent state ha

been explored in theories of chaos,self-organization,and complexity as important to

418 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

of social resources, such as supportive social climate. Schaufeli, Bakker, and Van Rhenen

(2009) replicated this finding among managers from a Dutch telecom company in a

longitudinalstudy.These findings suggest thatsocialresources are notan exclusive

antecedentof team work engagement.Also,Torrente et al.’s (2012b) modelfails to

integrate whatwe already know aboutteam processes and team effectiveness,and

essentially represents a homologous (Kozlowski& Klein, 2000) transposition ofthe

individual-level model of engagement, therefore overlooking possible important differ-

ences between levels.

Overall, previous research on work engagement in teams has some limitations. Most

studies do not present a clear definition of the construct or a theoretical model for team

work engagement that accounts for variables exclusively relevant in the context of team

Even when considering team-relevant variables and team members’ interaction, researc

on team work engagement has not yet been integrated within the specific literature on

teams. In the next section, we attempt to overcome these limitations, by presenting a

model for team work engagement emergence based on the existing team effectiveness

literature.

Defining team work engagement

Team work engagement is as a shared,positive and fulfilling,motivationalemergent

state of work-related well-being. Just like individual-level work engagement (Schaufeli &

Bakker,2004;Shaufeli& Bakker,2010),team work engagementis proposed as a

multidimensionalconstruct characterized by affective and cognitive dimensions:team

vigour,team dedication,and team absorption.Team vigour stands for high levels of

energy and for an expression of willingness to invest effort in work and persistence in

the face ofdifficulties (e.g.,conflict,bad performance feedback);for example,team

members enthusiastically encourage demoralized colleagues and explicitly express their

desire to continue working.Team dedication is a shared strong involvement in work

and an expression ofa sense of significance,enthusiasm,inspiration,pride, and

challenge while doing so; for example, team members talk to each other and to others

(external to the team) about the importance of their work and about the thrill they feel

concerning theirwork. Team absorption represents a shared focused attention on

work, whereby team members experience and express difficulties detaching them-

selvesfrom work, such as team memberstalk about their work during breaks,

commenting on time passing quickly, and not engaging in non-work-related interactions

when working.

Keeping functional equivalence with the work engagement definition proposed by

Schaufeli and Bakker (2003), this emergent state will lead to team effectiveness. Howev

this definition allows for the conceptualization of a different construct’s structure, based

on the interaction patterns among the team members and reflects two essential constru

rooted in the literature on teams and teamwork: emergent states and shared constructs

Emergent states

Whereas Torrente et al. (2012b) define team work engagement as a shared psychologica

state, we propose that team work engagement is an emergent state, something that is

exclusive to teams and cannot be found in individuals. The idea of an emergent state ha

been explored in theories of chaos,self-organization,and complexity as important to

418 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

understand how individuals contribute to organizational effectiveness (Kozlowski, C

Grand, Braun, & Kuljanin, 2013; Kozlowski & Klein, 2000). Marks et al. (2001) distin

between team processes and team emergent states, discriminating two different a

of the life of work teams fundamentalfor their understanding.Team processes are

‘member’s interdependentacts thatconvertinputs to outcomes through cognitive,

verbal,and behaviouralactivitiesdirected towardsorganizing taskwork to achieve

collective goals’ (p. 357). Team processes involve the interaction of team members

each other and with their task environment and are used to direct, align, and monit

membersare doing.For example,strategy formulation,coordination,and tracking

resources are team processes. On the other hand, emergent states are properties o

team that are dynamic in nature and that vary as a function of:team context,inputs,

processes, and outcomes. Emergent states describe cognitive, motivational, and aff

states of teams.Constructs such as collective efficacy,cohesion,or team potency are

emergent states (Kozlowski& Chao,2012) because they refer to team qualities that

represent members’attitudes,values,cognitions,and motivations and not interaction

processes.

Team work engagementis considered an emergentstate that‘originates in the

cognition, affect, behaviours, or other characteristics of individuals, is amplified by

interactions, and manifests at a higher level’ (Kozlowski & Klein, 2000, p. 55). Its st

depends on team experiences,namely on their members’interactions during team

processes.For example,a certain sales team may have a low levelof team work

engagement (e.g., low motivation to work, low levels of persistence, and low pride

work) in a context of a diminished amount of sales,constant conflicts between team

members, a lack of feedback and orientation, and aggressive and depreciative com

from the leader. The same team’s level of engagement may start to increase when

those elements change: a new leader who is capable of clear goal setting and who

display an energetic mood,a boost of the sales, a better management of the conflicts,

among others. These changes in team work engagement are not directly dependen

objective events, but rather on the changes those events bring to the interaction b

team members.

It is the fact ofbeing an emergent state that departs the construct ofteam work

engagement from individual-level work engagement – it does not depend on job re

but essentially on the complex interplay of team’s inputs, processes, and outputs, a

team members’ interactions. This conceptualization of team work engagement is m

complex than the onespreviously presented in the literature.Yet, it reflectsthe

complexityinherentto human systemsand is embedded in actualmodelsfor

conceptualizing teamwork.

Shared

The second main difference between team and individualwork engagementis the

assumption ofsharedness,already presentin previous definitionsof team work

engagement. The implication of being a shared state is that team members must h

similar perceptions about their collective degree ofwork engagement.According to

Kozlowski and Klein (2000), emergentconstructsmay be the result either of

composition (followingadditiveor averagingcombination rules)or compilation

(following nonlinearcombination rules such asproportion orindices of variance)

processes.The combination rules ofthe lower-levelunits to form the higher-level

emergent state should be consistent with the previous theoretical conceptualizatio

Team work engagement419

Grand, Braun, & Kuljanin, 2013; Kozlowski & Klein, 2000). Marks et al. (2001) distin

between team processes and team emergent states, discriminating two different a

of the life of work teams fundamentalfor their understanding.Team processes are

‘member’s interdependentacts thatconvertinputs to outcomes through cognitive,

verbal,and behaviouralactivitiesdirected towardsorganizing taskwork to achieve

collective goals’ (p. 357). Team processes involve the interaction of team members

each other and with their task environment and are used to direct, align, and monit

membersare doing.For example,strategy formulation,coordination,and tracking

resources are team processes. On the other hand, emergent states are properties o

team that are dynamic in nature and that vary as a function of:team context,inputs,

processes, and outcomes. Emergent states describe cognitive, motivational, and aff

states of teams.Constructs such as collective efficacy,cohesion,or team potency are

emergent states (Kozlowski& Chao,2012) because they refer to team qualities that

represent members’attitudes,values,cognitions,and motivations and not interaction

processes.

Team work engagementis considered an emergentstate that‘originates in the

cognition, affect, behaviours, or other characteristics of individuals, is amplified by

interactions, and manifests at a higher level’ (Kozlowski & Klein, 2000, p. 55). Its st

depends on team experiences,namely on their members’interactions during team

processes.For example,a certain sales team may have a low levelof team work

engagement (e.g., low motivation to work, low levels of persistence, and low pride

work) in a context of a diminished amount of sales,constant conflicts between team

members, a lack of feedback and orientation, and aggressive and depreciative com

from the leader. The same team’s level of engagement may start to increase when

those elements change: a new leader who is capable of clear goal setting and who

display an energetic mood,a boost of the sales, a better management of the conflicts,

among others. These changes in team work engagement are not directly dependen

objective events, but rather on the changes those events bring to the interaction b

team members.

It is the fact ofbeing an emergent state that departs the construct ofteam work

engagement from individual-level work engagement – it does not depend on job re

but essentially on the complex interplay of team’s inputs, processes, and outputs, a

team members’ interactions. This conceptualization of team work engagement is m

complex than the onespreviously presented in the literature.Yet, it reflectsthe

complexityinherentto human systemsand is embedded in actualmodelsfor

conceptualizing teamwork.

Shared

The second main difference between team and individualwork engagementis the

assumption ofsharedness,already presentin previous definitionsof team work

engagement. The implication of being a shared state is that team members must h

similar perceptions about their collective degree ofwork engagement.According to

Kozlowski and Klein (2000), emergentconstructsmay be the result either of

composition (followingadditiveor averagingcombination rules)or compilation

(following nonlinearcombination rules such asproportion orindices of variance)

processes.The combination rules ofthe lower-levelunits to form the higher-level

emergent state should be consistent with the previous theoretical conceptualizatio

Team work engagement419

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

emergence.In the case of team work engagement,its conceptualization reflects a

composition process,because it is assumed that every team member is influenced by

what is happening to and within the team in a similar way.

When assessing theircollective energy and involvement,team membersmust

consider the behaviour ofall team members and how they allinteractduring team

processes. Therefore, every member is assessing a common observable experience and

not how they, individually, feel. Team members all base their judgement on the same cu

and,thus,are likely to display a common understanding ofwhat they perceive.For

example,if they attend a meeting where one team member is highly exited when

describing a new product,while many others are absently looking at their phones or

tablets, all are able to perceive that, collectively, their energy and dedication is not very

high. This is what Kozlowskiand Klein (2000)define as ‘convergentemergence’:

Contextualfactors and interaction processes constrain emergence in such a way that

individuals contribute the same type and amount of elemental content (the perception o

their team’s level of engagement). It follows logically that the conceptualization propose

in this study is not an isomorphic transposition of individual work engagement levels to

the team level, but rather from the perceptions of team work engagement from the lowe

units (individuals) to the higher unit (the team).

Using individuallevels of engagement to compute team work engagement (either

through composition or compilation) would be misleading. It would not to represent a

team property and researchers cannot assume its sharedness, because each member co

make a differentcontribution to the collectiveengagementlevel. Instead,the

referent-shift composition model (Chan, 1998) is consistent with the proposed rationale.

This is a composition model that uses within group consensus (the agreement of team

members’ on their team’s level of work engagement) to compose the collective construc

by asking individuals collectively formulated items (e.g., ‘we’).

Proposition1: Team work engagementis a shared motivationalemergentstate

characterized by team vigour, team dedication, and team absorption.

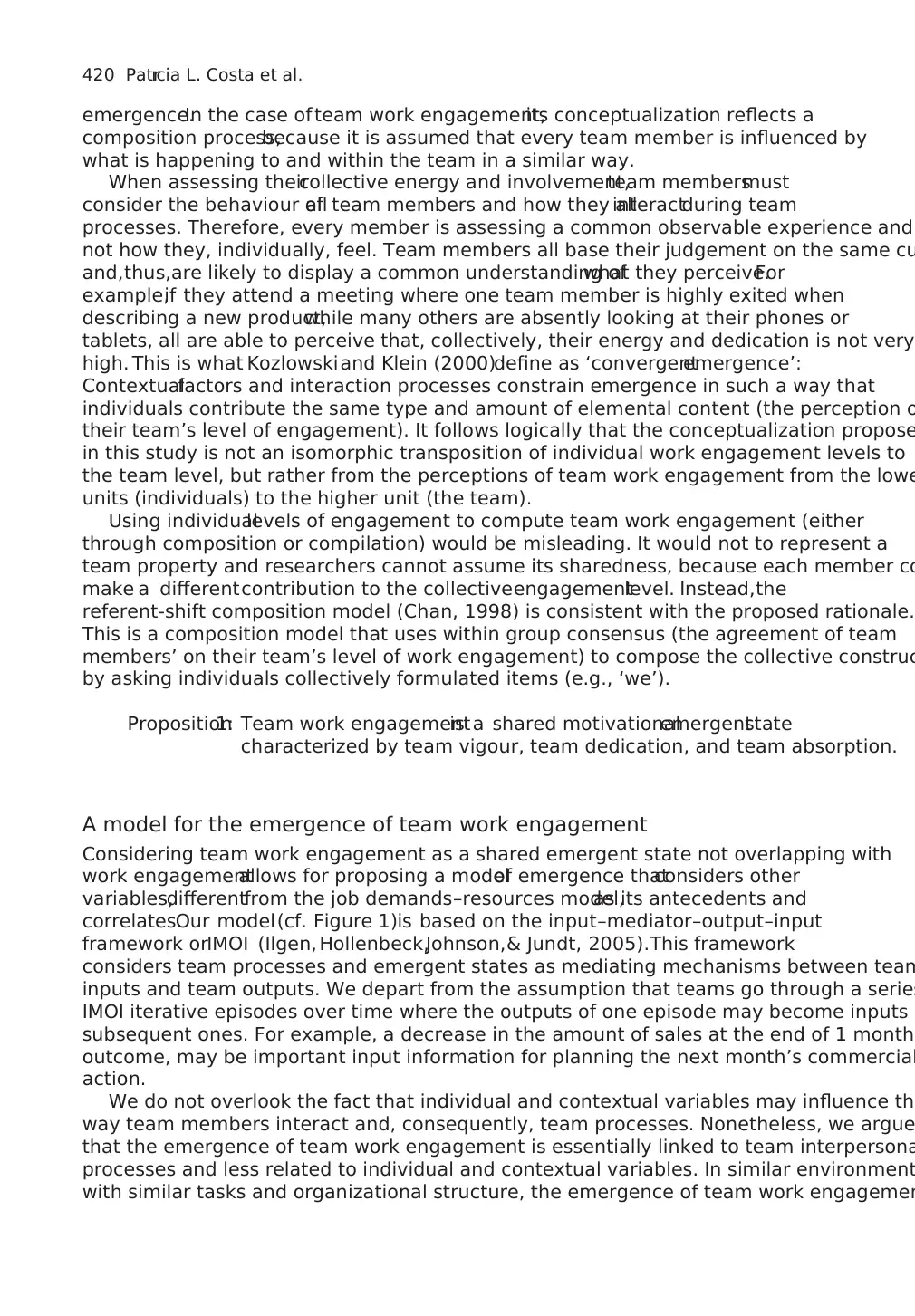

A model for the emergence of team work engagement

Considering team work engagement as a shared emergent state not overlapping with

work engagementallows for proposing a modelof emergence thatconsiders other

variables,differentfrom the job demands–resources model,as its antecedents and

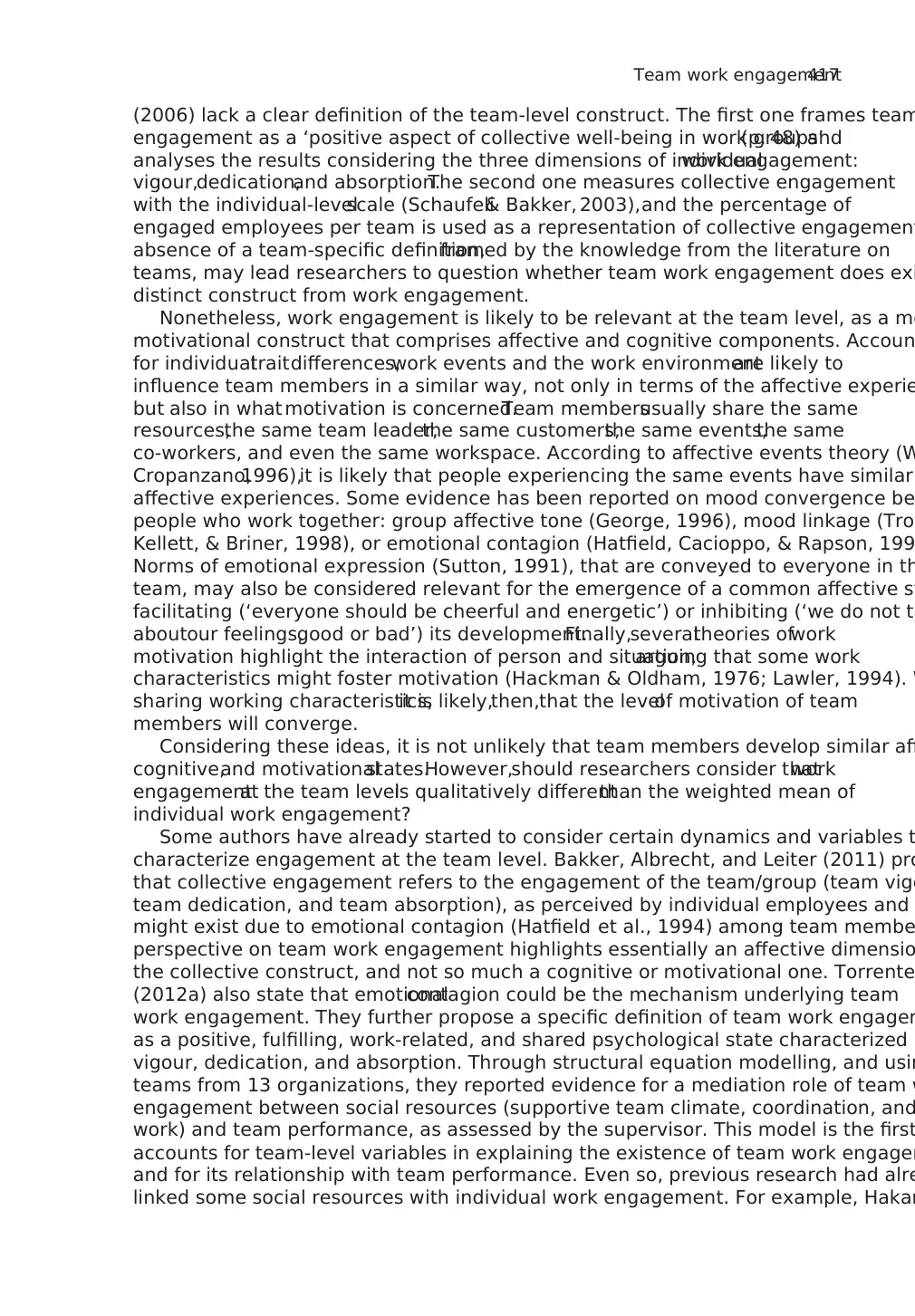

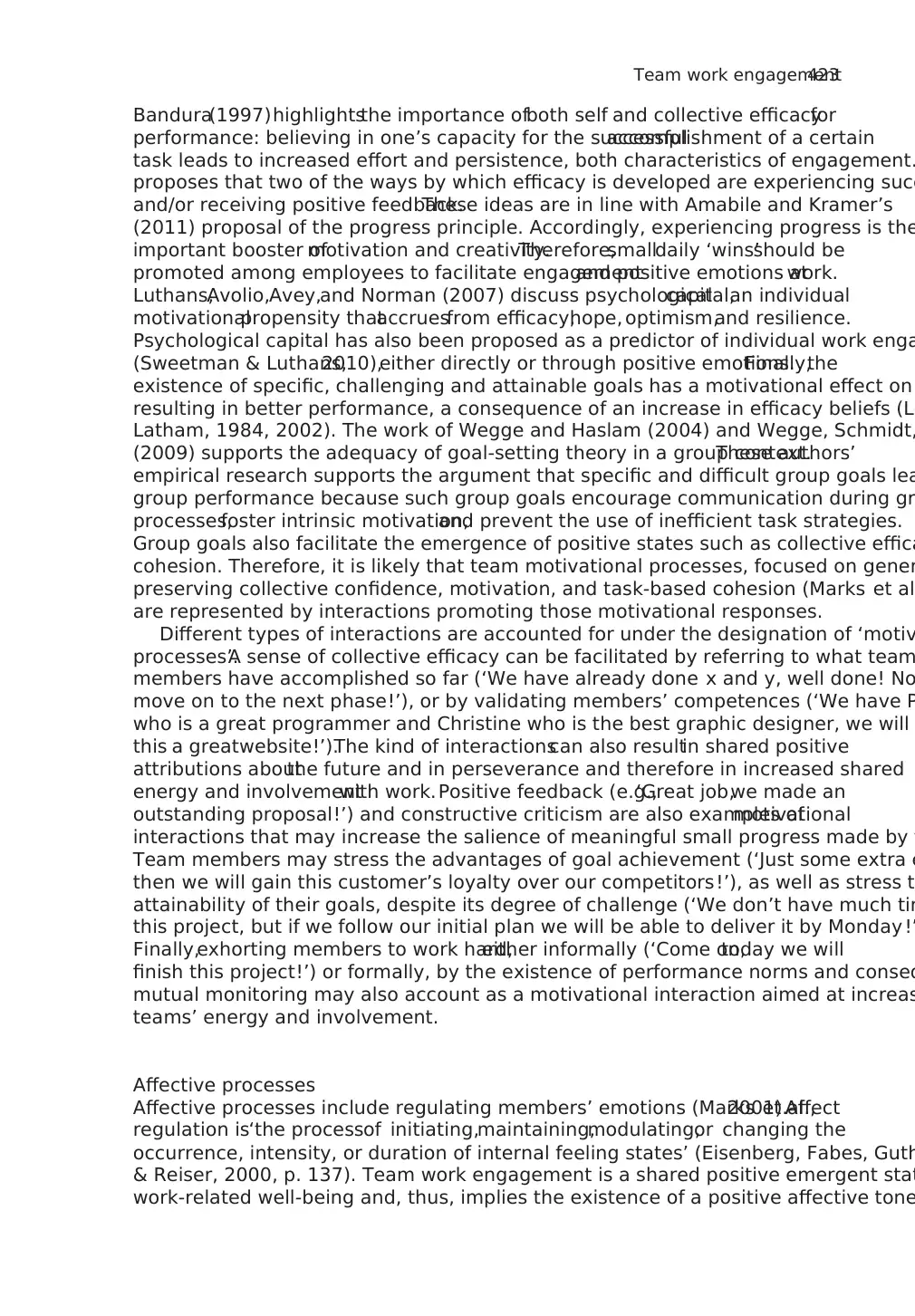

correlates.Our model(cf. Figure 1)is based on the input–mediator–output–input

framework orIMOI (Ilgen, Hollenbeck,Johnson,& Jundt, 2005).This framework

considers team processes and emergent states as mediating mechanisms between team

inputs and team outputs. We depart from the assumption that teams go through a series

IMOI iterative episodes over time where the outputs of one episode may become inputs o

subsequent ones. For example, a decrease in the amount of sales at the end of 1 month,

outcome, may be important input information for planning the next month’s commercial

action.

We do not overlook the fact that individual and contextual variables may influence the

way team members interact and, consequently, team processes. Nonetheless, we argue

that the emergence of team work engagement is essentially linked to team interpersona

processes and less related to individual and contextual variables. In similar environment

with similar tasks and organizational structure, the emergence of team work engagemen

420 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

composition process,because it is assumed that every team member is influenced by

what is happening to and within the team in a similar way.

When assessing theircollective energy and involvement,team membersmust

consider the behaviour ofall team members and how they allinteractduring team

processes. Therefore, every member is assessing a common observable experience and

not how they, individually, feel. Team members all base their judgement on the same cu

and,thus,are likely to display a common understanding ofwhat they perceive.For

example,if they attend a meeting where one team member is highly exited when

describing a new product,while many others are absently looking at their phones or

tablets, all are able to perceive that, collectively, their energy and dedication is not very

high. This is what Kozlowskiand Klein (2000)define as ‘convergentemergence’:

Contextualfactors and interaction processes constrain emergence in such a way that

individuals contribute the same type and amount of elemental content (the perception o

their team’s level of engagement). It follows logically that the conceptualization propose

in this study is not an isomorphic transposition of individual work engagement levels to

the team level, but rather from the perceptions of team work engagement from the lowe

units (individuals) to the higher unit (the team).

Using individuallevels of engagement to compute team work engagement (either

through composition or compilation) would be misleading. It would not to represent a

team property and researchers cannot assume its sharedness, because each member co

make a differentcontribution to the collectiveengagementlevel. Instead,the

referent-shift composition model (Chan, 1998) is consistent with the proposed rationale.

This is a composition model that uses within group consensus (the agreement of team

members’ on their team’s level of work engagement) to compose the collective construc

by asking individuals collectively formulated items (e.g., ‘we’).

Proposition1: Team work engagementis a shared motivationalemergentstate

characterized by team vigour, team dedication, and team absorption.

A model for the emergence of team work engagement

Considering team work engagement as a shared emergent state not overlapping with

work engagementallows for proposing a modelof emergence thatconsiders other

variables,differentfrom the job demands–resources model,as its antecedents and

correlates.Our model(cf. Figure 1)is based on the input–mediator–output–input

framework orIMOI (Ilgen, Hollenbeck,Johnson,& Jundt, 2005).This framework

considers team processes and emergent states as mediating mechanisms between team

inputs and team outputs. We depart from the assumption that teams go through a series

IMOI iterative episodes over time where the outputs of one episode may become inputs o

subsequent ones. For example, a decrease in the amount of sales at the end of 1 month,

outcome, may be important input information for planning the next month’s commercial

action.

We do not overlook the fact that individual and contextual variables may influence the

way team members interact and, consequently, team processes. Nonetheless, we argue

that the emergence of team work engagement is essentially linked to team interpersona

processes and less related to individual and contextual variables. In similar environment

with similar tasks and organizational structure, the emergence of team work engagemen

420 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

will rely heavily on team interpersonal processes. In the next section, we develop th

ideas in depth.

Inputs

Since Gladstein’s (1984) inputs–processes–outputs model of team effectiveness, th

30 years of research have provided scholars and practitioners with a multiplicity of

models to understand teams and teamwork.However,‘while there exists a general

consensus aboutthe nature ofthe broad categories ofinput variables,the specific

constructs proposed to be encapsulated within these categories varies’(Salas,Stagl,

Burke, & Goodwin, 2007). When integrating the different proposals, four major umb

variables are most commonly put forward: individual characteristics, team characte

task characteristics, and work structure (cf. Figure 1). All of these input variables ca

considered for the emergence of team work engagement,either having a more direct

influence or an indirect one, by their effect on the way team members interact.

According to Salas et al.(2007), individual characteristics include variables such as

team orientation and personality.Team orientation is the propensity to consider the

other’s behaviour when interacting and also the belief in the importance of commo

(team) goals over individual members’ ones (Salas, Sims, & Burke, 2005). Therefore

more team members are high in team orientation, the more likely they are to inves

in their work,and to avoid conflictualinteractions.In what personality is concerned,

extraversion (Costa & McCrae, 1985; Eysenck, 1998) is considered an important pre

of positive feelings (Watson & Clark, 1997). For example, Emmons and Diener (198

found that extraversion significantly correlates with positive affect but not with neg

affect. Additionally, positive affective states and a high activation are positive corre

extraverts (Kuppens,2008).Finally,the individuals’levelof work engagement might

work as an input variable for team work engagement, because individuals will alrea

more predisposed to feel and display vigour, dedication, and absorption towards wo

Team characteristics include team’s culture and climate and the power structure

team. Bakker et al. (2011) proposed that teams with a climate for engagement will

collective engagement.Climate for engagementinvolves the shared perception ofa

Motivational

processes

Affective

processes

TWE

Other emergent states:

collective efficacy, cohesion,

group affect, etc.

Individual

characteristics

Team characteristics

Task characteristics

Work structure

Team effectiveness

Conflict

management

Figure 1. Modelfor the emergence ofteam work engagement.Solid arrows signaldirect effects.

Dotted arrows signal feedback loops. Dashed arrow signals a correlational relationship.

Team work engagement421

ideas in depth.

Inputs

Since Gladstein’s (1984) inputs–processes–outputs model of team effectiveness, th

30 years of research have provided scholars and practitioners with a multiplicity of

models to understand teams and teamwork.However,‘while there exists a general

consensus aboutthe nature ofthe broad categories ofinput variables,the specific

constructs proposed to be encapsulated within these categories varies’(Salas,Stagl,

Burke, & Goodwin, 2007). When integrating the different proposals, four major umb

variables are most commonly put forward: individual characteristics, team characte

task characteristics, and work structure (cf. Figure 1). All of these input variables ca

considered for the emergence of team work engagement,either having a more direct

influence or an indirect one, by their effect on the way team members interact.

According to Salas et al.(2007), individual characteristics include variables such as

team orientation and personality.Team orientation is the propensity to consider the

other’s behaviour when interacting and also the belief in the importance of commo

(team) goals over individual members’ ones (Salas, Sims, & Burke, 2005). Therefore

more team members are high in team orientation, the more likely they are to inves

in their work,and to avoid conflictualinteractions.In what personality is concerned,

extraversion (Costa & McCrae, 1985; Eysenck, 1998) is considered an important pre

of positive feelings (Watson & Clark, 1997). For example, Emmons and Diener (198

found that extraversion significantly correlates with positive affect but not with neg

affect. Additionally, positive affective states and a high activation are positive corre

extraverts (Kuppens,2008).Finally,the individuals’levelof work engagement might

work as an input variable for team work engagement, because individuals will alrea

more predisposed to feel and display vigour, dedication, and absorption towards wo

Team characteristics include team’s culture and climate and the power structure

team. Bakker et al. (2011) proposed that teams with a climate for engagement will

collective engagement.Climate for engagementinvolves the shared perception ofa

Motivational

processes

Affective

processes

TWE

Other emergent states:

collective efficacy, cohesion,

group affect, etc.

Individual

characteristics

Team characteristics

Task characteristics

Work structure

Team effectiveness

Conflict

management

Figure 1. Modelfor the emergence ofteam work engagement.Solid arrows signaldirect effects.

Dotted arrows signal feedback loops. Dashed arrow signals a correlational relationship.

Team work engagement421

challenging, resourceful, and supportive environment and encompasses the six areas of

worklife proposed by Maslach and Leiter (2008):realistic and challenging workload,

control, reward, community and collaboration, fairness, and values.

In what task characteristics are concerned,differenttasks may require different

degreesof interdependencebetween team members,which is consideredthe

touchstone of emergent states.Being involved in team processes requires interaction,

and the more team members interact,the more likely they are to develop shared

cognitive, affective, and motivational states, such as team work engagement. The degre

of interaction between team members has been related to the affective responses of

team members. For example,Van der Vegt,Emans,and van der Vliert (2001) showed

that individual-level task interdependency and job complexity were related to individual

job satisfaction and team satisfaction, and to job and team commitment in a sample of

technicalconsultants.These relationships were moderated by the degree of outcome

interdependence ofthe work group, with high outcome interdependentgroups

showing a higher positive relationship between the variables. Also, Anderson, Keltner,

and John (2003) studied emotionalconvergence in couplesand roommatesand

concluded that their responses on emotional content scales became more similar within

a year, reflecting a longer interaction period.

Finally,the work structure is also considered importantinput.Work structure is

related to work assignment,the formaland informalnorms ofteams,and to their

communication structure. Work structure defines who has access to what information

and when,as wellas the behaviours that are considerate appropriate,and these two

aspects will shape the nature of team members’ interaction.

Proposition 2:Team work engagementwill be a function ofthe followingteam

inputs:individualcharacteristics,team characteristics,task characteris-

tics, and work structure.

Team processes

More than one proposal on what processes are fundamental for team effectiveness can b

found in the literature. For example, Zaccaro, Rittman, and Marks (2001) distinguish four

major groups of processes: cognitive (e.g., shared mental models, Cannon-Bowers, Salas

& Converse, 1990), motivational(e.g.,group cohesion,performance norms),affective

(e.g., affectiveclimate),and coordination (e.g.,orientation,systemsmonitoring)

processes.Marks et al.(2001) divide team processes in three categories,illustrating

different performance phases of teams: transition phase processes (e.g., mission analysi

goal specification), action phase processes (e.g., monitoring progress, systems monitor-

ing),and interpersonalprocesses (motivation and confidence building,affect manage-

ment, and conflict management), that occur throughout the action and transition phases

For the emergence of team work engagement, interpersonal processes, focused on

motivating, affect management, and conflict management, might be pivotal (cf. Figure 1

These processes not only denote interaction but are relatively independent from specific

tasks or performance phases.

Motivationalprocesses

At the individual level, the relevance of some motivational constructs for work engageme

has been established – directly or indirectly – over the years.For example,the work of

422 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

worklife proposed by Maslach and Leiter (2008):realistic and challenging workload,

control, reward, community and collaboration, fairness, and values.

In what task characteristics are concerned,differenttasks may require different

degreesof interdependencebetween team members,which is consideredthe

touchstone of emergent states.Being involved in team processes requires interaction,

and the more team members interact,the more likely they are to develop shared

cognitive, affective, and motivational states, such as team work engagement. The degre

of interaction between team members has been related to the affective responses of

team members. For example,Van der Vegt,Emans,and van der Vliert (2001) showed

that individual-level task interdependency and job complexity were related to individual

job satisfaction and team satisfaction, and to job and team commitment in a sample of

technicalconsultants.These relationships were moderated by the degree of outcome

interdependence ofthe work group, with high outcome interdependentgroups

showing a higher positive relationship between the variables. Also, Anderson, Keltner,

and John (2003) studied emotionalconvergence in couplesand roommatesand

concluded that their responses on emotional content scales became more similar within

a year, reflecting a longer interaction period.

Finally,the work structure is also considered importantinput.Work structure is

related to work assignment,the formaland informalnorms ofteams,and to their

communication structure. Work structure defines who has access to what information

and when,as wellas the behaviours that are considerate appropriate,and these two

aspects will shape the nature of team members’ interaction.

Proposition 2:Team work engagementwill be a function ofthe followingteam

inputs:individualcharacteristics,team characteristics,task characteris-

tics, and work structure.

Team processes

More than one proposal on what processes are fundamental for team effectiveness can b

found in the literature. For example, Zaccaro, Rittman, and Marks (2001) distinguish four

major groups of processes: cognitive (e.g., shared mental models, Cannon-Bowers, Salas

& Converse, 1990), motivational(e.g.,group cohesion,performance norms),affective

(e.g., affectiveclimate),and coordination (e.g.,orientation,systemsmonitoring)

processes.Marks et al.(2001) divide team processes in three categories,illustrating

different performance phases of teams: transition phase processes (e.g., mission analysi

goal specification), action phase processes (e.g., monitoring progress, systems monitor-

ing),and interpersonalprocesses (motivation and confidence building,affect manage-

ment, and conflict management), that occur throughout the action and transition phases

For the emergence of team work engagement, interpersonal processes, focused on

motivating, affect management, and conflict management, might be pivotal (cf. Figure 1

These processes not only denote interaction but are relatively independent from specific

tasks or performance phases.

Motivationalprocesses

At the individual level, the relevance of some motivational constructs for work engageme

has been established – directly or indirectly – over the years.For example,the work of

422 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Bandura(1997)highlightsthe importance ofboth self and collective efficacyfor

performance: believing in one’s capacity for the successfulaccomplishment of a certain

task leads to increased effort and persistence, both characteristics of engagement.

proposes that two of the ways by which efficacy is developed are experiencing succ

and/or receiving positive feedback.These ideas are in line with Amabile and Kramer’s

(2011) proposal of the progress principle. Accordingly, experiencing progress is the

important booster ofmotivation and creativity.Therefore,smalldaily ‘wins’should be

promoted among employees to facilitate engagementand positive emotions atwork.

Luthans,Avolio,Avey,and Norman (2007) discuss psychologicalcapital,an individual

motivationalpropensity thataccruesfrom efficacy,hope, optimism,and resilience.

Psychological capital has also been proposed as a predictor of individual work enga

(Sweetman & Luthans,2010),either directly or through positive emotions.Finally,the

existence of specific, challenging and attainable goals has a motivational effect on

resulting in better performance, a consequence of an increase in efficacy beliefs (Lo

Latham, 1984, 2002). The work of Wegge and Haslam (2004) and Wegge, Schmidt,

(2009) supports the adequacy of goal-setting theory in a group context.These authors’

empirical research supports the argument that specific and difficult group goals lea

group performance because such group goals encourage communication during gr

processes,foster intrinsic motivation,and prevent the use of inefficient task strategies.

Group goals also facilitate the emergence of positive states such as collective effica

cohesion. Therefore, it is likely that team motivational processes, focused on gener

preserving collective confidence, motivation, and task-based cohesion (Marks et al

are represented by interactions promoting those motivational responses.

Different types of interactions are accounted for under the designation of ‘motiv

processes’.A sense of collective efficacy can be facilitated by referring to what team

members have accomplished so far (‘We have already done x and y, well done! No

move on to the next phase!’), or by validating members’ competences (‘We have P

who is a great programmer and Christine who is the best graphic designer, we will

this a greatwebsite!’).The kind of interactionscan also resultin shared positive

attributions aboutthe future and in perseverance and therefore in increased shared

energy and involvementwith work.Positive feedback (e.g.,‘Great job,we made an

outstanding proposal!’) and constructive criticism are also examples ofmotivational

interactions that may increase the salience of meaningful small progress made by t

Team members may stress the advantages of goal achievement (‘Just some extra e

then we will gain this customer’s loyalty over our competitors!’), as well as stress t

attainability of their goals, despite its degree of challenge (‘We don’t have much tim

this project, but if we follow our initial plan we will be able to deliver it by Monday !’

Finally,exhorting members to work hard,either informally (‘Come on,today we will

finish this project!’) or formally, by the existence of performance norms and conseq

mutual monitoring may also account as a motivational interaction aimed at increas

teams’ energy and involvement.

Affective processes

Affective processes include regulating members’ emotions (Marks et al.,2001).Affect

regulation is‘the processof initiating,maintaining,modulating,or changing the

occurrence, intensity, or duration of internal feeling states’ (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guth

& Reiser, 2000, p. 137). Team work engagement is a shared positive emergent stat

work-related well-being and, thus, implies the existence of a positive affective tone

Team work engagement423

performance: believing in one’s capacity for the successfulaccomplishment of a certain

task leads to increased effort and persistence, both characteristics of engagement.

proposes that two of the ways by which efficacy is developed are experiencing succ

and/or receiving positive feedback.These ideas are in line with Amabile and Kramer’s

(2011) proposal of the progress principle. Accordingly, experiencing progress is the

important booster ofmotivation and creativity.Therefore,smalldaily ‘wins’should be

promoted among employees to facilitate engagementand positive emotions atwork.

Luthans,Avolio,Avey,and Norman (2007) discuss psychologicalcapital,an individual

motivationalpropensity thataccruesfrom efficacy,hope, optimism,and resilience.

Psychological capital has also been proposed as a predictor of individual work enga

(Sweetman & Luthans,2010),either directly or through positive emotions.Finally,the

existence of specific, challenging and attainable goals has a motivational effect on

resulting in better performance, a consequence of an increase in efficacy beliefs (Lo

Latham, 1984, 2002). The work of Wegge and Haslam (2004) and Wegge, Schmidt,

(2009) supports the adequacy of goal-setting theory in a group context.These authors’

empirical research supports the argument that specific and difficult group goals lea

group performance because such group goals encourage communication during gr

processes,foster intrinsic motivation,and prevent the use of inefficient task strategies.

Group goals also facilitate the emergence of positive states such as collective effica

cohesion. Therefore, it is likely that team motivational processes, focused on gener

preserving collective confidence, motivation, and task-based cohesion (Marks et al

are represented by interactions promoting those motivational responses.

Different types of interactions are accounted for under the designation of ‘motiv

processes’.A sense of collective efficacy can be facilitated by referring to what team

members have accomplished so far (‘We have already done x and y, well done! No

move on to the next phase!’), or by validating members’ competences (‘We have P

who is a great programmer and Christine who is the best graphic designer, we will

this a greatwebsite!’).The kind of interactionscan also resultin shared positive

attributions aboutthe future and in perseverance and therefore in increased shared

energy and involvementwith work.Positive feedback (e.g.,‘Great job,we made an

outstanding proposal!’) and constructive criticism are also examples ofmotivational

interactions that may increase the salience of meaningful small progress made by t

Team members may stress the advantages of goal achievement (‘Just some extra e

then we will gain this customer’s loyalty over our competitors!’), as well as stress t

attainability of their goals, despite its degree of challenge (‘We don’t have much tim

this project, but if we follow our initial plan we will be able to deliver it by Monday !’

Finally,exhorting members to work hard,either informally (‘Come on,today we will

finish this project!’) or formally, by the existence of performance norms and conseq

mutual monitoring may also account as a motivational interaction aimed at increas

teams’ energy and involvement.

Affective processes

Affective processes include regulating members’ emotions (Marks et al.,2001).Affect

regulation is‘the processof initiating,maintaining,modulating,or changing the

occurrence, intensity, or duration of internal feeling states’ (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guth

& Reiser, 2000, p. 137). Team work engagement is a shared positive emergent stat

work-related well-being and, thus, implies the existence of a positive affective tone

Team work engagement423

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

the team.Managing affect and promoting a positive affective tone may occur through

three (not mutually exclusive) processes.

First, team members might use controlled interpersonal affect regulation strategies of

affect improving (Niven, Totterdell, & Holman, 2009) such as positive engagement and

acceptance. Positive engagement is related to involving the other with his or hers situati

or affect in order to improve his or hers affect. When presented with a difficult task, team

members may try to change the way others think about that situation, suggesting that t

will be able to succeed and giving advice on possible courses of action; they may point o

the positive characteristics ofthe team orof specific members,following negative

feedback; faced with irritated co-workers, team members can make themselves availabl

to listen to what is bothering him or her, allowing him or her to vent his or her emotions.

Acceptance is a relationship-oriented strategy that implies communicating validation to

the other person. Team members express their caring for the team and its members and

try to make them feel special (e.g., by celebrating individual and team accomplishments

spending their off-work time doing activities with the other team members).Within

acceptance strategies, using humour and jokes may also foster an improvement in the

team members’ affect.

Affectregulation within teams can also representa controlled attemptto exert

interpersonalinfluence over attitudes and behaviours of team members,and not over

their affective experience per se.For example,teams develop a set of implicit and/or

explicit norms about which emotions should be displayed in the context of work and

abouthow those norms should be displayed (Rafaeli& Sutton,1987).For example,

Sutton (1991) found thatbill collectors were selected,socialized,and rewarded for

following the norm ofconveying high arousaland slightirritation to customers (a

sense of urgency).Focusing on the construct of team work engagement, display rules

will impact its emergence in two ways.When team members express their emotions

in a very explicit way,it will facilitate an accurate evaluation oftheir affective state

by others.Consequently,it will more likely result in a shared perception,because it

will be less contaminated by personalinterpretations,because itwill be based on

explicitinformation.At the same time,if display rules focus on the expression of

positive emotions,the emergence ofteam work engagementmay be facilitated –

more team memberswill expresspositiveaffect and act congruentlywith the

definition of team work engagement,displaying enthusiasm and energy.This display

will, in turn, reinforceteam members’perception of the teams’high level of

engagement.

Finally, the affective climate of the group may be due to emotional contagion (Bakker

et al., 2006; Torrente et al., 2012b). This is based on the transmission of non-verbal sign

of emotion (tone ofvoice,facialexpressiveness,and tempo ofdiscourse)that are

automatically and subconsciously reproduced by the other, which ends by experiencing

similar emotionalstates (Hatfield et al.,1994).Expressing emotions using non-verbal

information leads team members to become more similar in terms of affect (Barsade,

2002). When that expression is focused on positive emotions, it will enhance the teams’

level of team work engagement.

Conflict management is related to the handling of conflict situations either before or

after they have arisen (Marks et al., 2001).Interpersonalconflict may directly worsen

team members’affect,because individuals are rude to each other,accuse others of

inappropriate behaviour,or reject each other’sfeelings,and motivation,because

individuals are unable to give constructive criticism and become more self-centred and

less concerned with the teams’ collective goal accomplishment (DeWit, Greer, & Jehn,

424 Patrıcia L. Costa et al.

three (not mutually exclusive) processes.

First, team members might use controlled interpersonal affect regulation strategies of

affect improving (Niven, Totterdell, & Holman, 2009) such as positive engagement and