Accounting scandals: The dozy watchdogs

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/23

|9

|3582

|57

AI Summary

This article discusses the failure of auditors to detect accounting scandals and the need for serious reforms. It highlights the conflicts of interest and misaligned incentives built into auditing that all but guarantee that accountants will fall short of investors’ needs. The article also talks about the role of auditors in modern capitalism and the history of auditing. It mentions some of the major accounting scandals and the involvement of the Big Four global accounting networks. Desklib provides study material with solved assignments, essays, dissertations, etc. Subscribe now!

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Accounting scandals

The dozy watchdogs

Some 13 years after Enron, auditors still can’t stop managers cooking the books. Time for some serious reforms

Dec 11th 2014 | NEW YORK

Print edition | Briefing

NO ENDORSEMENT carries more weight than an investment by Warren Buffett. He became the world’s second-richest man by buying s

reliable businesses and holding them for ever. So when his company increased its stake in Tesco to 5% in 2012, it sent a strong messa

giant British grocer would rebound from its disastrous attempt to compete in America.

But it turned out that even the Oracle of Omaha can fall victim to dodgy accounting. On September 22nd Tesco announced that its pro

guidance for the first half of 2014 was £250m ($408m) too high, because it had overstated the rebate income it would receive from su

Britain’s Serious Fraud Office has begun a criminal investigation into the errors. The company’s fortunes have worsened since then: on

December 9th it cut its profit forecast by 30%, partly because its new boss said it would stop “artificially” improving results by reducin

near the end of a quarter. Mr Buffett, whose firm has lost $750m on Tesco, now calls the trade a “huge mistake”.

Get our daily newsletterGet our daily newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor's Picks.

Email address Sign up now

Latest stories

A pivotal time for embattled religious minorities in the Middle East

ERASMUS

Announcing his retirement, Andy Murray begins to get his due at last

GAME THEORY

How America’s government shutdown is affecting flyers

GULLIVER

See more

Subscribe

The dozy watchdogs

Some 13 years after Enron, auditors still can’t stop managers cooking the books. Time for some serious reforms

Dec 11th 2014 | NEW YORK

Print edition | Briefing

NO ENDORSEMENT carries more weight than an investment by Warren Buffett. He became the world’s second-richest man by buying s

reliable businesses and holding them for ever. So when his company increased its stake in Tesco to 5% in 2012, it sent a strong messa

giant British grocer would rebound from its disastrous attempt to compete in America.

But it turned out that even the Oracle of Omaha can fall victim to dodgy accounting. On September 22nd Tesco announced that its pro

guidance for the first half of 2014 was £250m ($408m) too high, because it had overstated the rebate income it would receive from su

Britain’s Serious Fraud Office has begun a criminal investigation into the errors. The company’s fortunes have worsened since then: on

December 9th it cut its profit forecast by 30%, partly because its new boss said it would stop “artificially” improving results by reducin

near the end of a quarter. Mr Buffett, whose firm has lost $750m on Tesco, now calls the trade a “huge mistake”.

Get our daily newsletterGet our daily newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor's Picks.

Email address Sign up now

Latest stories

A pivotal time for embattled religious minorities in the Middle East

ERASMUS

Announcing his retirement, Andy Murray begins to get his due at last

GAME THEORY

How America’s government shutdown is affecting flyers

GULLIVER

See more

Subscribe

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

No sooner did the news break than the spotlight fell on PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), one of the “Big Four” global accounting networ

others are Deloitte, Ernst & Young (EY) and KPMG). Tesco had paid the firm £10.4m to sign off on its 2013 financial statements. PwC m

the suspect rebates as an area of heightened scrutiny, but still gave a clean audit.

PwC’s failure to detect the problem is hardly an isolated case. If accounting scandals no longer dominate headlines as they did when E

WorldCom imploded in 2001-02, that is not because they have vanished but because they have become routine. On December 4th a S

court reported that Bankia had mis-stated its finances when it went public in 2011, ten months before it was nationalised. In 2012 Hew

Packard wrote off 80% of its $10.3 billion purchase of Autonomy, a software company, after accusing the firm of counting forecast

subscriptions as current sales (Autonomy pleads innocence). The previous year Olympus, a Japanese optical-device maker, revealed it

hidden billions of dollars in losses. In each case, Big Four auditors had given their blessing.

And although accountants have largely avoided blame for the financial crisis of 2008, at the very least they failed to raise the alarm. A

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation is suing PwC for $1 billion for not detecting fraud at Colonial Bank, which failed in 2009. (PwC d

wrongdoing and says the bank deceived the firm.) This June two KPMG auditors received suspensions for failing to scrutinise loan-loss

at TierOne, another failed bank. Just eight months before Lehman Brothers’ demise, EY’s audit kept mum about the repurchase transa

that disguised the bank’s leverage.

The situation is graver still in emerging markets. In 2009 Satyam, an Indian technology company, admitted it had faked over $1 billion

on its books. North American exchanges have de-listed more than 100 Chinese firms in recent years because of accounting problems.

Jon Carnes, a short seller, sent a cameraman to a biodiesel factory that China Integrated Energy (a KPMG client) said was producing at

and found it had been dormant for months. The next year Muddy Waters, a research firm, discovered that much of the timber Sino-For

(audited by EY) claimed to own did not exist. Both companies lost over 95% of their value.

Of course, no police force can hope to prevent every crime. But such frequent scandals call into question whether this is the best the B

can do—and if so, whether their efforts are worth the $50 billion a year they collect in audit fees. In popular imagination, auditors are t

sniff out fraud. But because the profession was historically allowed to self-regulate despite enjoying a government-guaranteed franchis

set the bar so low—formally, auditors merely opine on whether financial statements meet accounting standards—that it is all but impo

for them to fail at their jobs, as they define them. In recent years this yawning “expectations gap” has led to a pattern in which investo

disregard auditors and make little effort to learn about their work, value securities as if audited financial statements were the gospel tr

then erupt in righteous fury when the inevitable downward revisions cost them their shirts.

The stakes are high. If investors stop trusting financial statements, they will charge a higher cost of capital to honest and deceitful com

alike, reducing funds available for investment and slowing growth. Only substantial reform of the auditors’ perverse business model ca

this cycle of disappointment.

Born with the railwaysBorn with the railways

Auditors perform a central role in modern capitalism. Ever since the invention of the joint-stock corporation, shareholders have been p

by the mismatch between the interests of a firm’s owners and those of its managers. Because a company’s executives know far more

operations than its investors do, they have every incentive to line their pockets and hide its true condition. In turn, the markets will wit

capital from firms whose managers they distrust. Auditors arose to resolve this “information asymmetry”.

Early joint-stock firms like the Dutch East India Company designated a handful of investors to make sure the books added up, though t

primitive auditors generally lacked the time or expertise to provide an effective check on management. By the mid-1800s, British lend

capital-hungry American railway companies deployed chartered accountants—the first modern auditors—to investigate every aspect o

railroads’ businesses. These Anglophone roots have proved durable: 150 years later, the Big Four global networks are still essentially c

by their branches in the United States and Britain. Their current bosses are all American.

As the number of investors in companies grew, so did the inefficiency of each of them sending separate sleuths to keep management

Moreover, companies hoping to cut financing costs realised they could extract better terms by getting an auditor to vouch for them. Th

accountants in turn had an incentive to evaluate their clients fairly, in order to command the trust of the markets. By the 1920s, 80% o

companies on the New York Stock Exchange voluntarily hired an auditor.

Unfortunately, Jazz Age investors did not distinguish between audited companies and their less scrupulous peers. Among the miscrean

Swedish Match, a European firm whose skill at securing state-sanctioned monopolies was surpassed only by the aggression of its accou

After its boss, Ivar Kreuger, died in 1932 the company collapsed, costing American investors the equivalent of $4.33 billion in current d

Soon after this the Democratic Congress, cleaning up the markets after the Great Depression, instituted a rule that all publicly held firm

issue audited financial statements. Britain had already brought in a similar policy.

Just what that audit should entail, however, remained an open question. Some legislators proposed that the newly formed Securities a

Exchange Commission should conduct audits itself. However, Congress decided to let accountants determine for themselves what thei

would contain. That ill-fated choice paved the way for a watering-down of the audit report that plagues markets to this day.

others are Deloitte, Ernst & Young (EY) and KPMG). Tesco had paid the firm £10.4m to sign off on its 2013 financial statements. PwC m

the suspect rebates as an area of heightened scrutiny, but still gave a clean audit.

PwC’s failure to detect the problem is hardly an isolated case. If accounting scandals no longer dominate headlines as they did when E

WorldCom imploded in 2001-02, that is not because they have vanished but because they have become routine. On December 4th a S

court reported that Bankia had mis-stated its finances when it went public in 2011, ten months before it was nationalised. In 2012 Hew

Packard wrote off 80% of its $10.3 billion purchase of Autonomy, a software company, after accusing the firm of counting forecast

subscriptions as current sales (Autonomy pleads innocence). The previous year Olympus, a Japanese optical-device maker, revealed it

hidden billions of dollars in losses. In each case, Big Four auditors had given their blessing.

And although accountants have largely avoided blame for the financial crisis of 2008, at the very least they failed to raise the alarm. A

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation is suing PwC for $1 billion for not detecting fraud at Colonial Bank, which failed in 2009. (PwC d

wrongdoing and says the bank deceived the firm.) This June two KPMG auditors received suspensions for failing to scrutinise loan-loss

at TierOne, another failed bank. Just eight months before Lehman Brothers’ demise, EY’s audit kept mum about the repurchase transa

that disguised the bank’s leverage.

The situation is graver still in emerging markets. In 2009 Satyam, an Indian technology company, admitted it had faked over $1 billion

on its books. North American exchanges have de-listed more than 100 Chinese firms in recent years because of accounting problems.

Jon Carnes, a short seller, sent a cameraman to a biodiesel factory that China Integrated Energy (a KPMG client) said was producing at

and found it had been dormant for months. The next year Muddy Waters, a research firm, discovered that much of the timber Sino-For

(audited by EY) claimed to own did not exist. Both companies lost over 95% of their value.

Of course, no police force can hope to prevent every crime. But such frequent scandals call into question whether this is the best the B

can do—and if so, whether their efforts are worth the $50 billion a year they collect in audit fees. In popular imagination, auditors are t

sniff out fraud. But because the profession was historically allowed to self-regulate despite enjoying a government-guaranteed franchis

set the bar so low—formally, auditors merely opine on whether financial statements meet accounting standards—that it is all but impo

for them to fail at their jobs, as they define them. In recent years this yawning “expectations gap” has led to a pattern in which investo

disregard auditors and make little effort to learn about their work, value securities as if audited financial statements were the gospel tr

then erupt in righteous fury when the inevitable downward revisions cost them their shirts.

The stakes are high. If investors stop trusting financial statements, they will charge a higher cost of capital to honest and deceitful com

alike, reducing funds available for investment and slowing growth. Only substantial reform of the auditors’ perverse business model ca

this cycle of disappointment.

Born with the railwaysBorn with the railways

Auditors perform a central role in modern capitalism. Ever since the invention of the joint-stock corporation, shareholders have been p

by the mismatch between the interests of a firm’s owners and those of its managers. Because a company’s executives know far more

operations than its investors do, they have every incentive to line their pockets and hide its true condition. In turn, the markets will wit

capital from firms whose managers they distrust. Auditors arose to resolve this “information asymmetry”.

Early joint-stock firms like the Dutch East India Company designated a handful of investors to make sure the books added up, though t

primitive auditors generally lacked the time or expertise to provide an effective check on management. By the mid-1800s, British lend

capital-hungry American railway companies deployed chartered accountants—the first modern auditors—to investigate every aspect o

railroads’ businesses. These Anglophone roots have proved durable: 150 years later, the Big Four global networks are still essentially c

by their branches in the United States and Britain. Their current bosses are all American.

As the number of investors in companies grew, so did the inefficiency of each of them sending separate sleuths to keep management

Moreover, companies hoping to cut financing costs realised they could extract better terms by getting an auditor to vouch for them. Th

accountants in turn had an incentive to evaluate their clients fairly, in order to command the trust of the markets. By the 1920s, 80% o

companies on the New York Stock Exchange voluntarily hired an auditor.

Unfortunately, Jazz Age investors did not distinguish between audited companies and their less scrupulous peers. Among the miscrean

Swedish Match, a European firm whose skill at securing state-sanctioned monopolies was surpassed only by the aggression of its accou

After its boss, Ivar Kreuger, died in 1932 the company collapsed, costing American investors the equivalent of $4.33 billion in current d

Soon after this the Democratic Congress, cleaning up the markets after the Great Depression, instituted a rule that all publicly held firm

issue audited financial statements. Britain had already brought in a similar policy.

Just what that audit should entail, however, remained an open question. Some legislators proposed that the newly formed Securities a

Exchange Commission should conduct audits itself. However, Congress decided to let accountants determine for themselves what thei

would contain. That ill-fated choice paved the way for a watering-down of the audit report that plagues markets to this day.

Even in the age of voluntary audits, accountants were rarely held accountable for their clients’ sins. As a British judge declared in 1896

auditor is not bound to be a detective…he is a watchdog, not a bloodhound.” The advent of mandatory audits exacerbated this hazard

auditors no longer needed to provide value to investors in order to induce companies to buy their services. Without any external rules

the profession had to verify, it quickly began reducing its own responsibility. Having once offered a “guarantee” that statements were

auditors soon moved on to mere “opinions”.

The modern audit does not even provide an opinion on accuracy. Instead, the boilerplate one-page pass/fail report in America merely p

“reasonable assurance” that a company’s statements “present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of [the company] in

conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)”. GAAP is a 7,700-page behemoth, packed with arbitrary cut-offs and

estimate ranges, and riddled with loopholes so big that some accountants argue even Enron complied with them. (International Financ

Reporting Standards (IFRS), which are used outside the United States, rely more on broad principles). “An auditor’s opinion really says

financial information is more or less OK, in general, so far as we can tell, most of the time’,” says Jim Peterson, a former lawyer for Arth

Andersen, the now-defunct accounting firm that audited Enron. “Nobody has paid any attention or put real value on it for about 30 yea

Although auditors cannot hope to verify more than a tiny fraction of the millions of transactions their clients conduct, in order to compl

the standards they physically count inventories, match invoices with shipments and bank statements, and consult experts on the plaus

of management’s estimates. Most firms’ records are at least tweaked during the process. And even though private businesses do not h

undergo audits, most mid-size firms buy one anyway, because banks rarely lend to unaudited borrowers. The recent spate of frauds in

where auditing practices are far laxer, shows that markets are right to assign a premium to companies that receive a Western account

approval.

auditor is not bound to be a detective…he is a watchdog, not a bloodhound.” The advent of mandatory audits exacerbated this hazard

auditors no longer needed to provide value to investors in order to induce companies to buy their services. Without any external rules

the profession had to verify, it quickly began reducing its own responsibility. Having once offered a “guarantee” that statements were

auditors soon moved on to mere “opinions”.

The modern audit does not even provide an opinion on accuracy. Instead, the boilerplate one-page pass/fail report in America merely p

“reasonable assurance” that a company’s statements “present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of [the company] in

conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)”. GAAP is a 7,700-page behemoth, packed with arbitrary cut-offs and

estimate ranges, and riddled with loopholes so big that some accountants argue even Enron complied with them. (International Financ

Reporting Standards (IFRS), which are used outside the United States, rely more on broad principles). “An auditor’s opinion really says

financial information is more or less OK, in general, so far as we can tell, most of the time’,” says Jim Peterson, a former lawyer for Arth

Andersen, the now-defunct accounting firm that audited Enron. “Nobody has paid any attention or put real value on it for about 30 yea

Although auditors cannot hope to verify more than a tiny fraction of the millions of transactions their clients conduct, in order to compl

the standards they physically count inventories, match invoices with shipments and bank statements, and consult experts on the plaus

of management’s estimates. Most firms’ records are at least tweaked during the process. And even though private businesses do not h

undergo audits, most mid-size firms buy one anyway, because banks rarely lend to unaudited borrowers. The recent spate of frauds in

where auditing practices are far laxer, shows that markets are right to assign a premium to companies that receive a Western account

approval.

Those conflicts of interestThose conflicts of interest

Even so, the misaligned incentives built into auditing all but guarantee that accountants will fall short of investors’ needs. The benefici

the service—current and prospective shareholders—pay for it indirectly or not at all, while the purchasers buy it only because they are

to. As a result, companies tend to select auditors who will provide a clean opinion as cheaply and quickly as possible. Similarly, accoun

who discover irregularities may be better off asking management to make minor adjustments, rather than blowing the whistle on a mi

statement that could embroil their firm in costly litigation.

The audit industry cites four main factors that counteract this conflict of interest. One is the separation of the audit committee from

management. Ever since the Sarbanes-Oxley corporate-governance reform of 2002, American auditors have been chosen not by CEOs

but by a subcommittee of the board of directors. In theory, this should ensure they are selected and compensated with shareholders’ i

in mind. In practice, audit committees are easily captured by management. One academic study found that companies with a senior e

previously employed by a member of the Big Four are far more likely to be audited by that firm than its competitors. The head of Tesc

committee once worked at PwC.

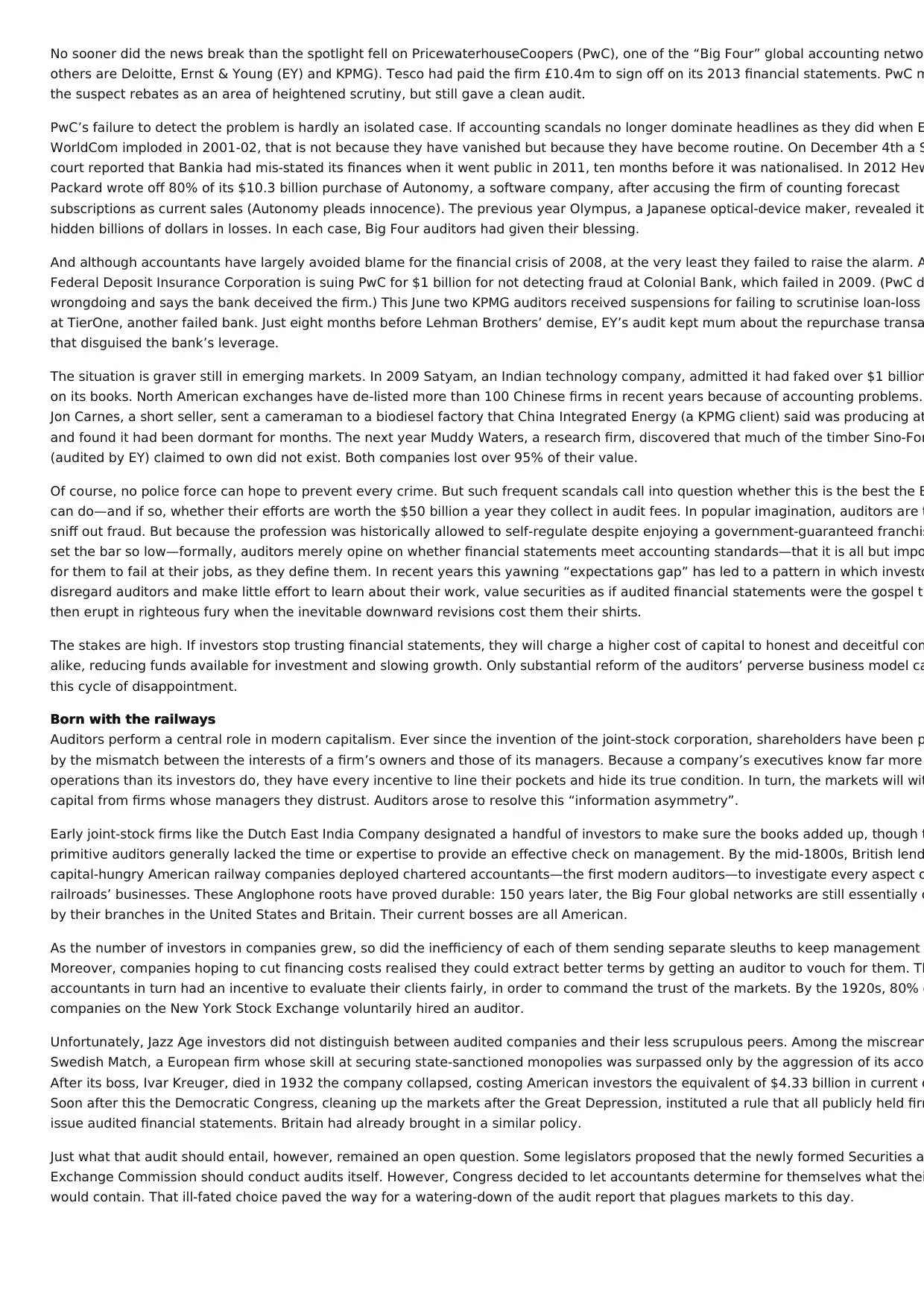

Another potential defence against conflict is reputation: an auditor known for shoddy work will lose business, because investors will no

believe its reports. That may have been true long ago, when companies could choose among many accountants. But today only the Bi

have the scale to audit giant multinationals; together, they audit firms that make up 98% of the value of American stockmarkets. And

of them have approved statements later revealed to be incorrect, none enjoys a reputation much above the others. Companies do not

Four auditors just because the firm failed to catch an error at a different client.

Even so, the misaligned incentives built into auditing all but guarantee that accountants will fall short of investors’ needs. The benefici

the service—current and prospective shareholders—pay for it indirectly or not at all, while the purchasers buy it only because they are

to. As a result, companies tend to select auditors who will provide a clean opinion as cheaply and quickly as possible. Similarly, accoun

who discover irregularities may be better off asking management to make minor adjustments, rather than blowing the whistle on a mi

statement that could embroil their firm in costly litigation.

The audit industry cites four main factors that counteract this conflict of interest. One is the separation of the audit committee from

management. Ever since the Sarbanes-Oxley corporate-governance reform of 2002, American auditors have been chosen not by CEOs

but by a subcommittee of the board of directors. In theory, this should ensure they are selected and compensated with shareholders’ i

in mind. In practice, audit committees are easily captured by management. One academic study found that companies with a senior e

previously employed by a member of the Big Four are far more likely to be audited by that firm than its competitors. The head of Tesc

committee once worked at PwC.

Another potential defence against conflict is reputation: an auditor known for shoddy work will lose business, because investors will no

believe its reports. That may have been true long ago, when companies could choose among many accountants. But today only the Bi

have the scale to audit giant multinationals; together, they audit firms that make up 98% of the value of American stockmarkets. And

of them have approved statements later revealed to be incorrect, none enjoys a reputation much above the others. Companies do not

Four auditors just because the firm failed to catch an error at a different client.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

A potentially stronger deterrent is legal risk. Ever since a 1969 Supreme Court case found auditors liable for failing to detect fraud, acc

have feared litigation from shareholders. Those concerns were vindicated when Arthur Andersen, a peer of the Big Four, was brought d

lawsuits related to the Enron scandal. But it took the biggest accounting failure in history to overcome the legal protections auditors en

Short of an Enron-scale disaster, the Big Four have generally beaten back suits or settled them for affordable sums. In America, plainti

to demonstrate intentional recklessness by the accountants in order to reach trial. And in 2005, the Supreme Court ruled that shareho

must prove a direct causal link between a defendant’s activity and a declining stock price in order to claim damages. Despite the audit

abysmal performance before the financial crisis, legal claims against them have been modest: this April an arbitration council ruled tha

not at fault in Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy.

That leaves only one truly effective force: regulation. In 1933, during a hearing on a law that helped establish mandatory audits, an ind

spokesman told Congress that auditors were fully independent from the accounting staffs of their clients. “You audit the controllers?” a

sceptical senator inquired. “Who audits you?” “Our conscience,” came the meek reply.

If there was any doubt that this was an insufficient safeguard, the Enron scandal eliminated it. In response, the Sarbanes-Oxley act lim

consulting work American accounting firms could do for audit clients, and set up the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCA

non-profit intended to play Big Brother to the Big Four. James Doty, its chairman, says that “We see [auditors] as professional people s

pressures to compromise their independence.” In 2004 Britain established a similar watchdog, which is part of the Financial Reporting

Council.

have feared litigation from shareholders. Those concerns were vindicated when Arthur Andersen, a peer of the Big Four, was brought d

lawsuits related to the Enron scandal. But it took the biggest accounting failure in history to overcome the legal protections auditors en

Short of an Enron-scale disaster, the Big Four have generally beaten back suits or settled them for affordable sums. In America, plainti

to demonstrate intentional recklessness by the accountants in order to reach trial. And in 2005, the Supreme Court ruled that shareho

must prove a direct causal link between a defendant’s activity and a declining stock price in order to claim damages. Despite the audit

abysmal performance before the financial crisis, legal claims against them have been modest: this April an arbitration council ruled tha

not at fault in Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy.

That leaves only one truly effective force: regulation. In 1933, during a hearing on a law that helped establish mandatory audits, an ind

spokesman told Congress that auditors were fully independent from the accounting staffs of their clients. “You audit the controllers?” a

sceptical senator inquired. “Who audits you?” “Our conscience,” came the meek reply.

If there was any doubt that this was an insufficient safeguard, the Enron scandal eliminated it. In response, the Sarbanes-Oxley act lim

consulting work American accounting firms could do for audit clients, and set up the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCA

non-profit intended to play Big Brother to the Big Four. James Doty, its chairman, says that “We see [auditors] as professional people s

pressures to compromise their independence.” In 2004 Britain established a similar watchdog, which is part of the Financial Reporting

Council.

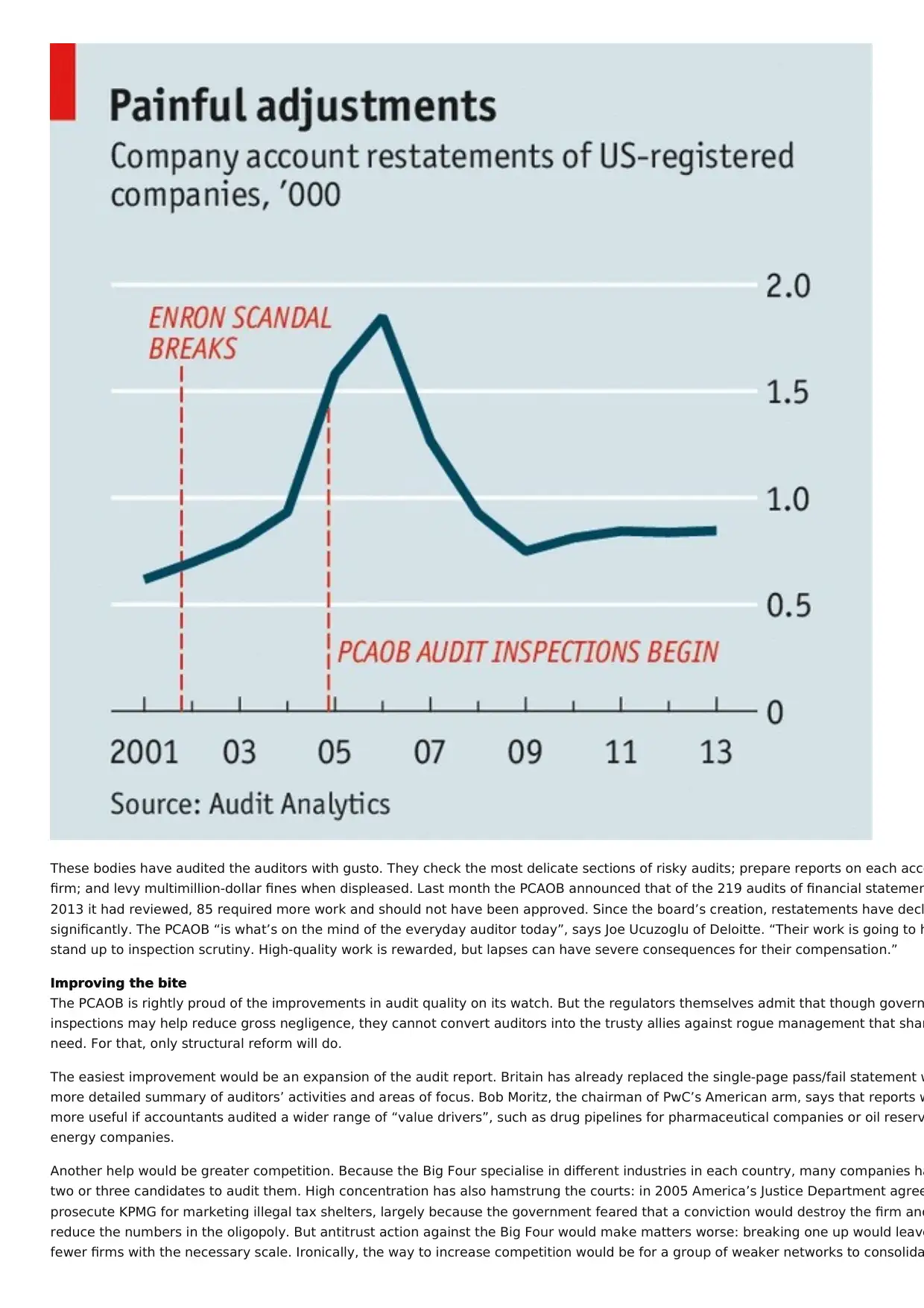

These bodies have audited the auditors with gusto. They check the most delicate sections of risky audits; prepare reports on each acco

firm; and levy multimillion-dollar fines when displeased. Last month the PCAOB announced that of the 219 audits of financial statemen

2013 it had reviewed, 85 required more work and should not have been approved. Since the board’s creation, restatements have decl

significantly. The PCAOB “is what’s on the mind of the everyday auditor today”, says Joe Ucuzoglu of Deloitte. “Their work is going to h

stand up to inspection scrutiny. High-quality work is rewarded, but lapses can have severe consequences for their compensation.”

Improving the biteImproving the bite

The PCAOB is rightly proud of the improvements in audit quality on its watch. But the regulators themselves admit that though govern

inspections may help reduce gross negligence, they cannot convert auditors into the trusty allies against rogue management that shar

need. For that, only structural reform will do.

The easiest improvement would be an expansion of the audit report. Britain has already replaced the single-page pass/fail statement w

more detailed summary of auditors’ activities and areas of focus. Bob Moritz, the chairman of PwC’s American arm, says that reports w

more useful if accountants audited a wider range of “value drivers”, such as drug pipelines for pharmaceutical companies or oil reserv

energy companies.

Another help would be greater competition. Because the Big Four specialise in different industries in each country, many companies ha

two or three candidates to audit them. High concentration has also hamstrung the courts: in 2005 America’s Justice Department agree

prosecute KPMG for marketing illegal tax shelters, largely because the government feared that a conviction would destroy the firm and

reduce the numbers in the oligopoly. But antitrust action against the Big Four would make matters worse: breaking one up would leave

fewer firms with the necessary scale. Ironically, the way to increase competition would be for a group of weaker networks to consolida

firm; and levy multimillion-dollar fines when displeased. Last month the PCAOB announced that of the 219 audits of financial statemen

2013 it had reviewed, 85 required more work and should not have been approved. Since the board’s creation, restatements have decl

significantly. The PCAOB “is what’s on the mind of the everyday auditor today”, says Joe Ucuzoglu of Deloitte. “Their work is going to h

stand up to inspection scrutiny. High-quality work is rewarded, but lapses can have severe consequences for their compensation.”

Improving the biteImproving the bite

The PCAOB is rightly proud of the improvements in audit quality on its watch. But the regulators themselves admit that though govern

inspections may help reduce gross negligence, they cannot convert auditors into the trusty allies against rogue management that shar

need. For that, only structural reform will do.

The easiest improvement would be an expansion of the audit report. Britain has already replaced the single-page pass/fail statement w

more detailed summary of auditors’ activities and areas of focus. Bob Moritz, the chairman of PwC’s American arm, says that reports w

more useful if accountants audited a wider range of “value drivers”, such as drug pipelines for pharmaceutical companies or oil reserv

energy companies.

Another help would be greater competition. Because the Big Four specialise in different industries in each country, many companies ha

two or three candidates to audit them. High concentration has also hamstrung the courts: in 2005 America’s Justice Department agree

prosecute KPMG for marketing illegal tax shelters, largely because the government feared that a conviction would destroy the firm and

reduce the numbers in the oligopoly. But antitrust action against the Big Four would make matters worse: breaking one up would leave

fewer firms with the necessary scale. Ironically, the way to increase competition would be for a group of weaker networks to consolida

Dec 11th 2014 | NEW YORK

Print edition | Briefing

Reuse this content

About The Economist

new global player. However, even KPMG, the smallest of the Big Four, is larger than the next four firms combined.

Proposals to modify how auditors are chosen or paid invariably involve trade-offs. The simplest would be to shield the audit committee

more from management influence, by having it nominated by a separate proxy vote rather than the board of directors. Whether arm’s

shareholders would know enough to do so is debatable. But the change would reduce the risk of the CFO suggesting an auditor to a co

member on the golf course.

Some critics suggest taking the selection of auditors away from companies entirely. One model would hand that responsibility to stock

exchanges. However, exchanges might be more interested in using lax audit rules to induce companies to list than in courting investor

marketing themselves as fraud-free platforms. To avoid that risk, many pundits suggest that government should appoint auditors inste

even that the profession should be nationalised. “Do people panic when the IRS descends on them, or when your friendly neighbourho

auditor that you pay does?” asks Prem Sikka of the University of Essex. “Companies should be directly audited by an arm of the regula

Small-government types hate either prospect.

The most elegant solution comes from Joshua Ronen, a professor at New York University. He suggests “financial statements insurance

which firms would buy coverage to protect shareholders against losses from accounting errors, and insurers would then hire auditors t

the odds of a mis-statement. The proposal neatly aligns the incentives of auditors and shareholders—an insurer would probably offer g

bonuses for discovering fraud. Unfortunately, no insurer has offered such coverage voluntarily. New regulation may be needed to enco

Finally, the answer for free-market purists is to scrap the legal requirement for audits. Today accountants enjoy a captive market, and

maximise profits by doing the job as cheaply as possible. If clients were no longer forced to buy audits, those rents would disappear. In

stay in business, the Big Four would then have to devise a new type of audit that investors actually found useful. This approach would

yield detailed reports designed with shareholders’ interests in mind. But it would also allow hucksters to peddle unaudited penny stock

gullible investors. Whether government should protect people from bad decisions is a question with implications far beyond accounting

Tales of self-harm

Why Imran Khan is unlikely to make life much better for Pakistanis

The army sets the agenda

Print edition | Briefing

Reuse this content

About The Economist

new global player. However, even KPMG, the smallest of the Big Four, is larger than the next four firms combined.

Proposals to modify how auditors are chosen or paid invariably involve trade-offs. The simplest would be to shield the audit committee

more from management influence, by having it nominated by a separate proxy vote rather than the board of directors. Whether arm’s

shareholders would know enough to do so is debatable. But the change would reduce the risk of the CFO suggesting an auditor to a co

member on the golf course.

Some critics suggest taking the selection of auditors away from companies entirely. One model would hand that responsibility to stock

exchanges. However, exchanges might be more interested in using lax audit rules to induce companies to list than in courting investor

marketing themselves as fraud-free platforms. To avoid that risk, many pundits suggest that government should appoint auditors inste

even that the profession should be nationalised. “Do people panic when the IRS descends on them, or when your friendly neighbourho

auditor that you pay does?” asks Prem Sikka of the University of Essex. “Companies should be directly audited by an arm of the regula

Small-government types hate either prospect.

The most elegant solution comes from Joshua Ronen, a professor at New York University. He suggests “financial statements insurance

which firms would buy coverage to protect shareholders against losses from accounting errors, and insurers would then hire auditors t

the odds of a mis-statement. The proposal neatly aligns the incentives of auditors and shareholders—an insurer would probably offer g

bonuses for discovering fraud. Unfortunately, no insurer has offered such coverage voluntarily. New regulation may be needed to enco

Finally, the answer for free-market purists is to scrap the legal requirement for audits. Today accountants enjoy a captive market, and

maximise profits by doing the job as cheaply as possible. If clients were no longer forced to buy audits, those rents would disappear. In

stay in business, the Big Four would then have to devise a new type of audit that investors actually found useful. This approach would

yield detailed reports designed with shareholders’ interests in mind. But it would also allow hucksters to peddle unaudited penny stock

gullible investors. Whether government should protect people from bad decisions is a question with implications far beyond accounting

Tales of self-harm

Why Imran Khan is unlikely to make life much better for Pakistanis

The army sets the agenda

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Subscribe Group subscriptions Contact us

Help

Keep updated

Sign up to get more from The Economist

Get 3 free articles per week, daily newsletters and more.

Email address Sign up

About The Economist

Advertise Reprints

Careers Media Centre

Terms of Use Privacy

Cookie Policy Manage Cookies

Help

Keep updated

Sign up to get more from The Economist

Get 3 free articles per week, daily newsletters and more.

Email address Sign up

About The Economist

Advertise Reprints

Careers Media Centre

Terms of Use Privacy

Cookie Policy Manage Cookies

Accessibility Modern Slavery Statement

Copyright © The Economist Newspaper Limited 2019. All rights reserved.

Each week, over one million subscribersEach week, over one million subscribers trusttrust

us to help them make sense of the world.us to help them make sense of the world.

Join them. SubscribeSubscribe toThe Economisttoday and

enjoy great savings

plus receive a free notebook.

or Sign up to continue reading three free articles

Subscribe now

Copyright © The Economist Newspaper Limited 2019. All rights reserved.

Each week, over one million subscribersEach week, over one million subscribers trusttrust

us to help them make sense of the world.us to help them make sense of the world.

Join them. SubscribeSubscribe toThe Economisttoday and

enjoy great savings

plus receive a free notebook.

or Sign up to continue reading three free articles

Subscribe now

1 out of 9

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.