Accounting scandals: The dozy watchdogs

9 Pages3582 Words57 Views

Added on 2023-04-23

About This Document

This article discusses the failure of auditors to detect accounting scandals and the need for serious reforms. It highlights the conflicts of interest and misaligned incentives built into auditing that all but guarantee that accountants will fall short of investors’ needs. The article also talks about the role of auditors in modern capitalism and the history of auditing. It mentions some of the major accounting scandals and the involvement of the Big Four global accounting networks. Desklib provides study material with solved assignments, essays, dissertations, etc. Subscribe now!

Accounting scandals: The dozy watchdogs

Added on 2023-04-23

ShareRelated Documents

Accounting scandals

The dozy watchdogsSome 13 years after Enron, auditors still can’t stop managers cooking the books. Time for some serious reforms

Dec 11th 2014 | NEW YORK

Print edition | Briefing

NO ENDORSEMENT carries more weight than an investment by Warren Buffett. He became the world’s second-richest man by buying safe,

reliable businesses and holding them for ever. So when his company increased its stake in Tesco to 5% in 2012, it sent a strong message that the

giant British grocer would rebound from its disastrous attempt to compete in America.

But it turned out that even the Oracle of Omaha can fall victim to dodgy accounting. On September 22nd Tesco announced that its profit

guidance for the first half of 2014 was £250m ($408m) too high, because it had overstated the rebate income it would receive from suppliers.

Britain’s Serious Fraud Office has begun a criminal investigation into the errors. The company’s fortunes have worsened since then: on

December 9th it cut its profit forecast by 30%, partly because its new boss said it would stop “artificially” improving results by reducing service

near the end of a quarter. Mr Buffett, whose firm has lost $750m on Tesco, now calls the trade a “huge mistake”.

Get our daily newsletterGet our daily newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor's Picks.

Email address Sign up now

Latest stories

A pivotal time for embattled religious minorities in the Middle East

ERASMUS

Announcing his retirement, Andy Murray begins to get his due at last

GAME THEORY

How America’s government shutdown is affecting flyers

GULLIVER

See more

Subscribe

The dozy watchdogsSome 13 years after Enron, auditors still can’t stop managers cooking the books. Time for some serious reforms

Dec 11th 2014 | NEW YORK

Print edition | Briefing

NO ENDORSEMENT carries more weight than an investment by Warren Buffett. He became the world’s second-richest man by buying safe,

reliable businesses and holding them for ever. So when his company increased its stake in Tesco to 5% in 2012, it sent a strong message that the

giant British grocer would rebound from its disastrous attempt to compete in America.

But it turned out that even the Oracle of Omaha can fall victim to dodgy accounting. On September 22nd Tesco announced that its profit

guidance for the first half of 2014 was £250m ($408m) too high, because it had overstated the rebate income it would receive from suppliers.

Britain’s Serious Fraud Office has begun a criminal investigation into the errors. The company’s fortunes have worsened since then: on

December 9th it cut its profit forecast by 30%, partly because its new boss said it would stop “artificially” improving results by reducing service

near the end of a quarter. Mr Buffett, whose firm has lost $750m on Tesco, now calls the trade a “huge mistake”.

Get our daily newsletterGet our daily newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor's Picks.

Email address Sign up now

Latest stories

A pivotal time for embattled religious minorities in the Middle East

ERASMUS

Announcing his retirement, Andy Murray begins to get his due at last

GAME THEORY

How America’s government shutdown is affecting flyers

GULLIVER

See more

Subscribe

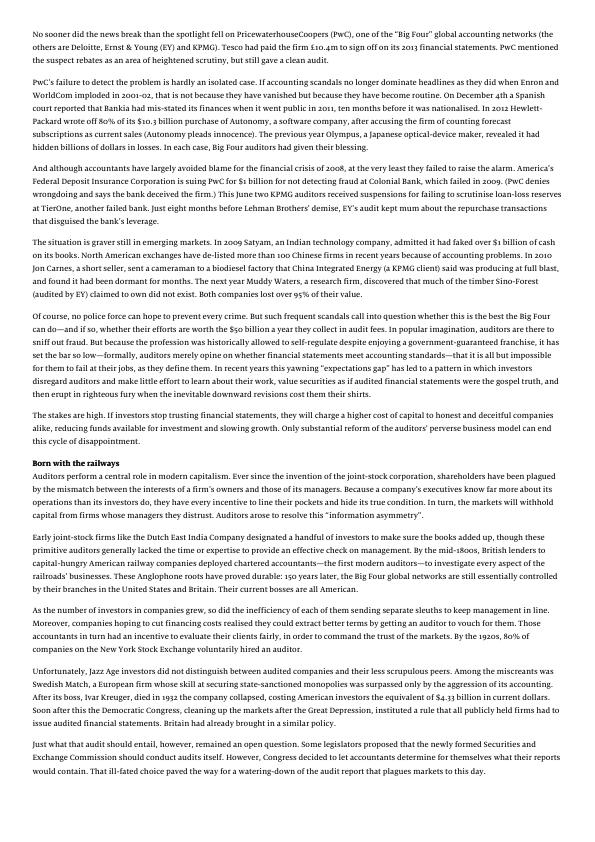

No sooner did the news break than the spotlight fell on PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), one of the “Big Four” global accounting networks (the

others are Deloitte, Ernst & Young (EY) and KPMG). Tesco had paid the firm £10.4m to sign off on its 2013 financial statements. PwC mentioned

the suspect rebates as an area of heightened scrutiny, but still gave a clean audit.

PwC’s failure to detect the problem is hardly an isolated case. If accounting scandals no longer dominate headlines as they did when Enron and

WorldCom imploded in 2001-02, that is not because they have vanished but because they have become routine. On December 4th a Spanish

court reported that Bankia had mis-stated its finances when it went public in 2011, ten months before it was nationalised. In 2012 Hewlett-

Packard wrote off 80% of its $10.3 billion purchase of Autonomy, a software company, after accusing the firm of counting forecast

subscriptions as current sales (Autonomy pleads innocence). The previous year Olympus, a Japanese optical-device maker, revealed it had

hidden billions of dollars in losses. In each case, Big Four auditors had given their blessing.

And although accountants have largely avoided blame for the financial crisis of 2008, at the very least they failed to raise the alarm. America’s

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation is suing PwC for $1 billion for not detecting fraud at Colonial Bank, which failed in 2009. (PwC denies

wrongdoing and says the bank deceived the firm.) This June two KPMG auditors received suspensions for failing to scrutinise loan-loss reserves

at TierOne, another failed bank. Just eight months before Lehman Brothers’ demise, EY’s audit kept mum about the repurchase transactions

that disguised the bank’s leverage.

The situation is graver still in emerging markets. In 2009 Satyam, an Indian technology company, admitted it had faked over $1 billion of cash

on its books. North American exchanges have de-listed more than 100 Chinese firms in recent years because of accounting problems. In 2010

Jon Carnes, a short seller, sent a cameraman to a biodiesel factory that China Integrated Energy (a KPMG client) said was producing at full blast,

and found it had been dormant for months. The next year Muddy Waters, a research firm, discovered that much of the timber Sino-Forest

(audited by EY) claimed to own did not exist. Both companies lost over 95% of their value.

Of course, no police force can hope to prevent every crime. But such frequent scandals call into question whether this is the best the Big Four

can do—and if so, whether their efforts are worth the $50 billion a year they collect in audit fees. In popular imagination, auditors are there to

sniff out fraud. But because the profession was historically allowed to self-regulate despite enjoying a government-guaranteed franchise, it has

set the bar so low—formally, auditors merely opine on whether financial statements meet accounting standards—that it is all but impossible

for them to fail at their jobs, as they define them. In recent years this yawning “expectations gap” has led to a pattern in which investors

disregard auditors and make little effort to learn about their work, value securities as if audited financial statements were the gospel truth, and

then erupt in righteous fury when the inevitable downward revisions cost them their shirts.

The stakes are high. If investors stop trusting financial statements, they will charge a higher cost of capital to honest and deceitful companies

alike, reducing funds available for investment and slowing growth. Only substantial reform of the auditors’ perverse business model can end

this cycle of disappointment.

Born with the railwaysBorn with the railways

Auditors perform a central role in modern capitalism. Ever since the invention of the joint-stock corporation, shareholders have been plagued

by the mismatch between the interests of a firm’s owners and those of its managers. Because a company’s executives know far more about its

operations than its investors do, they have every incentive to line their pockets and hide its true condition. In turn, the markets will withhold

capital from firms whose managers they distrust. Auditors arose to resolve this “information asymmetry”.

Early joint-stock firms like the Dutch East India Company designated a handful of investors to make sure the books added up, though these

primitive auditors generally lacked the time or expertise to provide an effective check on management. By the mid-1800s, British lenders to

capital-hungry American railway companies deployed chartered accountants—the first modern auditors—to investigate every aspect of the

railroads’ businesses. These Anglophone roots have proved durable: 150 years later, the Big Four global networks are still essentially controlled

by their branches in the United States and Britain. Their current bosses are all American.

As the number of investors in companies grew, so did the inefficiency of each of them sending separate sleuths to keep management in line.

Moreover, companies hoping to cut financing costs realised they could extract better terms by getting an auditor to vouch for them. Those

accountants in turn had an incentive to evaluate their clients fairly, in order to command the trust of the markets. By the 1920s, 80% of

companies on the New York Stock Exchange voluntarily hired an auditor.

Unfortunately, Jazz Age investors did not distinguish between audited companies and their less scrupulous peers. Among the miscreants was

Swedish Match, a European firm whose skill at securing state-sanctioned monopolies was surpassed only by the aggression of its accounting.

After its boss, Ivar Kreuger, died in 1932 the company collapsed, costing American investors the equivalent of $4.33 billion in current dollars.

Soon after this the Democratic Congress, cleaning up the markets after the Great Depression, instituted a rule that all publicly held firms had to

issue audited financial statements. Britain had already brought in a similar policy.

Just what that audit should entail, however, remained an open question. Some legislators proposed that the newly formed Securities and

Exchange Commission should conduct audits itself. However, Congress decided to let accountants determine for themselves what their reports

would contain. That ill-fated choice paved the way for a watering-down of the audit report that plagues markets to this day.

others are Deloitte, Ernst & Young (EY) and KPMG). Tesco had paid the firm £10.4m to sign off on its 2013 financial statements. PwC mentioned

the suspect rebates as an area of heightened scrutiny, but still gave a clean audit.

PwC’s failure to detect the problem is hardly an isolated case. If accounting scandals no longer dominate headlines as they did when Enron and

WorldCom imploded in 2001-02, that is not because they have vanished but because they have become routine. On December 4th a Spanish

court reported that Bankia had mis-stated its finances when it went public in 2011, ten months before it was nationalised. In 2012 Hewlett-

Packard wrote off 80% of its $10.3 billion purchase of Autonomy, a software company, after accusing the firm of counting forecast

subscriptions as current sales (Autonomy pleads innocence). The previous year Olympus, a Japanese optical-device maker, revealed it had

hidden billions of dollars in losses. In each case, Big Four auditors had given their blessing.

And although accountants have largely avoided blame for the financial crisis of 2008, at the very least they failed to raise the alarm. America’s

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation is suing PwC for $1 billion for not detecting fraud at Colonial Bank, which failed in 2009. (PwC denies

wrongdoing and says the bank deceived the firm.) This June two KPMG auditors received suspensions for failing to scrutinise loan-loss reserves

at TierOne, another failed bank. Just eight months before Lehman Brothers’ demise, EY’s audit kept mum about the repurchase transactions

that disguised the bank’s leverage.

The situation is graver still in emerging markets. In 2009 Satyam, an Indian technology company, admitted it had faked over $1 billion of cash

on its books. North American exchanges have de-listed more than 100 Chinese firms in recent years because of accounting problems. In 2010

Jon Carnes, a short seller, sent a cameraman to a biodiesel factory that China Integrated Energy (a KPMG client) said was producing at full blast,

and found it had been dormant for months. The next year Muddy Waters, a research firm, discovered that much of the timber Sino-Forest

(audited by EY) claimed to own did not exist. Both companies lost over 95% of their value.

Of course, no police force can hope to prevent every crime. But such frequent scandals call into question whether this is the best the Big Four

can do—and if so, whether their efforts are worth the $50 billion a year they collect in audit fees. In popular imagination, auditors are there to

sniff out fraud. But because the profession was historically allowed to self-regulate despite enjoying a government-guaranteed franchise, it has

set the bar so low—formally, auditors merely opine on whether financial statements meet accounting standards—that it is all but impossible

for them to fail at their jobs, as they define them. In recent years this yawning “expectations gap” has led to a pattern in which investors

disregard auditors and make little effort to learn about their work, value securities as if audited financial statements were the gospel truth, and

then erupt in righteous fury when the inevitable downward revisions cost them their shirts.

The stakes are high. If investors stop trusting financial statements, they will charge a higher cost of capital to honest and deceitful companies

alike, reducing funds available for investment and slowing growth. Only substantial reform of the auditors’ perverse business model can end

this cycle of disappointment.

Born with the railwaysBorn with the railways

Auditors perform a central role in modern capitalism. Ever since the invention of the joint-stock corporation, shareholders have been plagued

by the mismatch between the interests of a firm’s owners and those of its managers. Because a company’s executives know far more about its

operations than its investors do, they have every incentive to line their pockets and hide its true condition. In turn, the markets will withhold

capital from firms whose managers they distrust. Auditors arose to resolve this “information asymmetry”.

Early joint-stock firms like the Dutch East India Company designated a handful of investors to make sure the books added up, though these

primitive auditors generally lacked the time or expertise to provide an effective check on management. By the mid-1800s, British lenders to

capital-hungry American railway companies deployed chartered accountants—the first modern auditors—to investigate every aspect of the

railroads’ businesses. These Anglophone roots have proved durable: 150 years later, the Big Four global networks are still essentially controlled

by their branches in the United States and Britain. Their current bosses are all American.

As the number of investors in companies grew, so did the inefficiency of each of them sending separate sleuths to keep management in line.

Moreover, companies hoping to cut financing costs realised they could extract better terms by getting an auditor to vouch for them. Those

accountants in turn had an incentive to evaluate their clients fairly, in order to command the trust of the markets. By the 1920s, 80% of

companies on the New York Stock Exchange voluntarily hired an auditor.

Unfortunately, Jazz Age investors did not distinguish between audited companies and their less scrupulous peers. Among the miscreants was

Swedish Match, a European firm whose skill at securing state-sanctioned monopolies was surpassed only by the aggression of its accounting.

After its boss, Ivar Kreuger, died in 1932 the company collapsed, costing American investors the equivalent of $4.33 billion in current dollars.

Soon after this the Democratic Congress, cleaning up the markets after the Great Depression, instituted a rule that all publicly held firms had to

issue audited financial statements. Britain had already brought in a similar policy.

Just what that audit should entail, however, remained an open question. Some legislators proposed that the newly formed Securities and

Exchange Commission should conduct audits itself. However, Congress decided to let accountants determine for themselves what their reports

would contain. That ill-fated choice paved the way for a watering-down of the audit report that plagues markets to this day.

Even in the age of voluntary audits, accountants were rarely held accountable for their clients’ sins. As a British judge declared in 1896, “An

auditor is not bound to be a detective...he is a watchdog, not a bloodhound.” The advent of mandatory audits exacerbated this hazard, because

auditors no longer needed to provide value to investors in order to induce companies to buy their services. Without any external rules on what

the profession had to verify, it quickly began reducing its own responsibility. Having once offered a “guarantee” that statements were correct,

auditors soon moved on to mere “opinions”.

The modern audit does not even provide an opinion on accuracy. Instead, the boilerplate one-page pass/fail report in America merely provides

“reasonable assurance” that a company’s statements “present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of [the company] in

conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)”. GAAP is a 7,700-page behemoth, packed with arbitrary cut-offs and wide

estimate ranges, and riddled with loopholes so big that some accountants argue even Enron complied with them. (International Financial

Reporting Standards (IFRS), which are used outside the United States, rely more on broad principles). “An auditor’s opinion really says, ‘This

financial information is more or less OK, in general, so far as we can tell, most of the time’,” says Jim Peterson, a former lawyer for Arthur

Andersen, the now-defunct accounting firm that audited Enron. “Nobody has paid any attention or put real value on it for about 30 years.”

Although auditors cannot hope to verify more than a tiny fraction of the millions of transactions their clients conduct, in order to comply with

the standards they physically count inventories, match invoices with shipments and bank statements, and consult experts on the plausibility

of management’s estimates. Most firms’ records are at least tweaked during the process. And even though private businesses do not have to

undergo audits, most mid-size firms buy one anyway, because banks rarely lend to unaudited borrowers. The recent spate of frauds in China,

where auditing practices are far laxer, shows that markets are right to assign a premium to companies that receive a Western accountant’s

approval.

auditor is not bound to be a detective...he is a watchdog, not a bloodhound.” The advent of mandatory audits exacerbated this hazard, because

auditors no longer needed to provide value to investors in order to induce companies to buy their services. Without any external rules on what

the profession had to verify, it quickly began reducing its own responsibility. Having once offered a “guarantee” that statements were correct,

auditors soon moved on to mere “opinions”.

The modern audit does not even provide an opinion on accuracy. Instead, the boilerplate one-page pass/fail report in America merely provides

“reasonable assurance” that a company’s statements “present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of [the company] in

conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)”. GAAP is a 7,700-page behemoth, packed with arbitrary cut-offs and wide

estimate ranges, and riddled with loopholes so big that some accountants argue even Enron complied with them. (International Financial

Reporting Standards (IFRS), which are used outside the United States, rely more on broad principles). “An auditor’s opinion really says, ‘This

financial information is more or less OK, in general, so far as we can tell, most of the time’,” says Jim Peterson, a former lawyer for Arthur

Andersen, the now-defunct accounting firm that audited Enron. “Nobody has paid any attention or put real value on it for about 30 years.”

Although auditors cannot hope to verify more than a tiny fraction of the millions of transactions their clients conduct, in order to comply with

the standards they physically count inventories, match invoices with shipments and bank statements, and consult experts on the plausibility

of management’s estimates. Most firms’ records are at least tweaked during the process. And even though private businesses do not have to

undergo audits, most mid-size firms buy one anyway, because banks rarely lend to unaudited borrowers. The recent spate of frauds in China,

where auditing practices are far laxer, shows that markets are right to assign a premium to companies that receive a Western accountant’s

approval.

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.