Global Economic Analysis: Australia, UK, and Other Nations

VerifiedAdded on 2021/05/30

|22

|3600

|159

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment analyzes the global economy, focusing on macroeconomic indicators and policies in several countries including Australia, the United Kingdom, China, Japan, and South Korea. The analysis includes the examination of nominal and real GDP, inflation, unemployment, gross capital formation, and government expenditure trends. The assignment also explores the relationship between trade balances and exchange rates, particularly between the Australian dollar and currencies of the UK, China, and Japan. Additionally, the aggregate expenditure model is used to assess the impact of fiscal policy, such as tax cuts, on real GDP. The dynamic aggregate demand and aggregate supply model are also used to analyze the effect of demand shocks on the economy, illustrating the short-run and long-run adjustments of key economic variables. This assignment provides a comprehensive overview of economic performance and policy implications across various nations.

Running Head: THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

The Global Economy

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Course ID

The Global Economy

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Course ID

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

Table of Contents

Part A...............................................................................................................................................2

Answer 1......................................................................................................................................2

Answer 2......................................................................................................................................3

Answer 3....................................................................................................................................13

Part B.............................................................................................................................................13

Answer 4....................................................................................................................................13

Aggregate Expenditure model.......................................................................................................13

Answer 5....................................................................................................................................15

Policy action of central bank.....................................................................................................16

Part C.............................................................................................................................................17

Introduction................................................................................................................................17

Economics Teacher: Roles and Skills required.........................................................................17

Personal attraction towards the job............................................................................................18

Video Analysis...........................................................................................................................19

Action Plan................................................................................................................................19

References......................................................................................................................................21

Table of Contents

Part A...............................................................................................................................................2

Answer 1......................................................................................................................................2

Answer 2......................................................................................................................................3

Answer 3....................................................................................................................................13

Part B.............................................................................................................................................13

Answer 4....................................................................................................................................13

Aggregate Expenditure model.......................................................................................................13

Answer 5....................................................................................................................................15

Policy action of central bank.....................................................................................................16

Part C.............................................................................................................................................17

Introduction................................................................................................................................17

Economics Teacher: Roles and Skills required.........................................................................17

Personal attraction towards the job............................................................................................18

Video Analysis...........................................................................................................................19

Action Plan................................................................................................................................19

References......................................................................................................................................21

2THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

Part A

Answer 1

Dec-1990

Dec-1991

Dec-1992

Dec-1993

Dec-1994

Dec-1995

Dec-1996

Dec-1997

Dec-1998

Dec-1999

Dec-2000

Dec-2001

Dec-2002

Dec-2003

Dec-2004

Dec-2005

Dec-2006

Dec-2007

Dec-2008

Dec-2009

Dec-2010

Dec-2011

Dec-2012

Dec-2013

Dec-2014

Dec-2015

Dec-2016

0

100000

200000

300000

400000

500000

Nominal and Real GDP

Nominal GDP Real GDP

Year

GDP

Figure 1: Nominal and real GDP at levels

(Source: abs.gov.au 2018)

Dec-1990

Feb-1992

Apr-1993

Jun-1994

Aug-1995

Oct-1996

Dec-1997

Feb-1999

Apr-2000

Jun-2001

Aug-2002

Oct-2003

Dec-2004

Feb-2006

Apr-2007

Jun-2008

Aug-2009

Oct-2010

Dec-2011

Feb-2013

Apr-2014

Jun-2015

Aug-2016

-2

0

2

4

GDP Growth

Real GDP Nominal GDP

Quarters

Growth (%)

Figure 2: Trend growth rate of nominal and real GDP

(Source: abs.gov.au 2018)

Part A

Answer 1

Dec-1990

Dec-1991

Dec-1992

Dec-1993

Dec-1994

Dec-1995

Dec-1996

Dec-1997

Dec-1998

Dec-1999

Dec-2000

Dec-2001

Dec-2002

Dec-2003

Dec-2004

Dec-2005

Dec-2006

Dec-2007

Dec-2008

Dec-2009

Dec-2010

Dec-2011

Dec-2012

Dec-2013

Dec-2014

Dec-2015

Dec-2016

0

100000

200000

300000

400000

500000

Nominal and Real GDP

Nominal GDP Real GDP

Year

GDP

Figure 1: Nominal and real GDP at levels

(Source: abs.gov.au 2018)

Dec-1990

Feb-1992

Apr-1993

Jun-1994

Aug-1995

Oct-1996

Dec-1997

Feb-1999

Apr-2000

Jun-2001

Aug-2002

Oct-2003

Dec-2004

Feb-2006

Apr-2007

Jun-2008

Aug-2009

Oct-2010

Dec-2011

Feb-2013

Apr-2014

Jun-2015

Aug-2016

-2

0

2

4

GDP Growth

Real GDP Nominal GDP

Quarters

Growth (%)

Figure 2: Trend growth rate of nominal and real GDP

(Source: abs.gov.au 2018)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

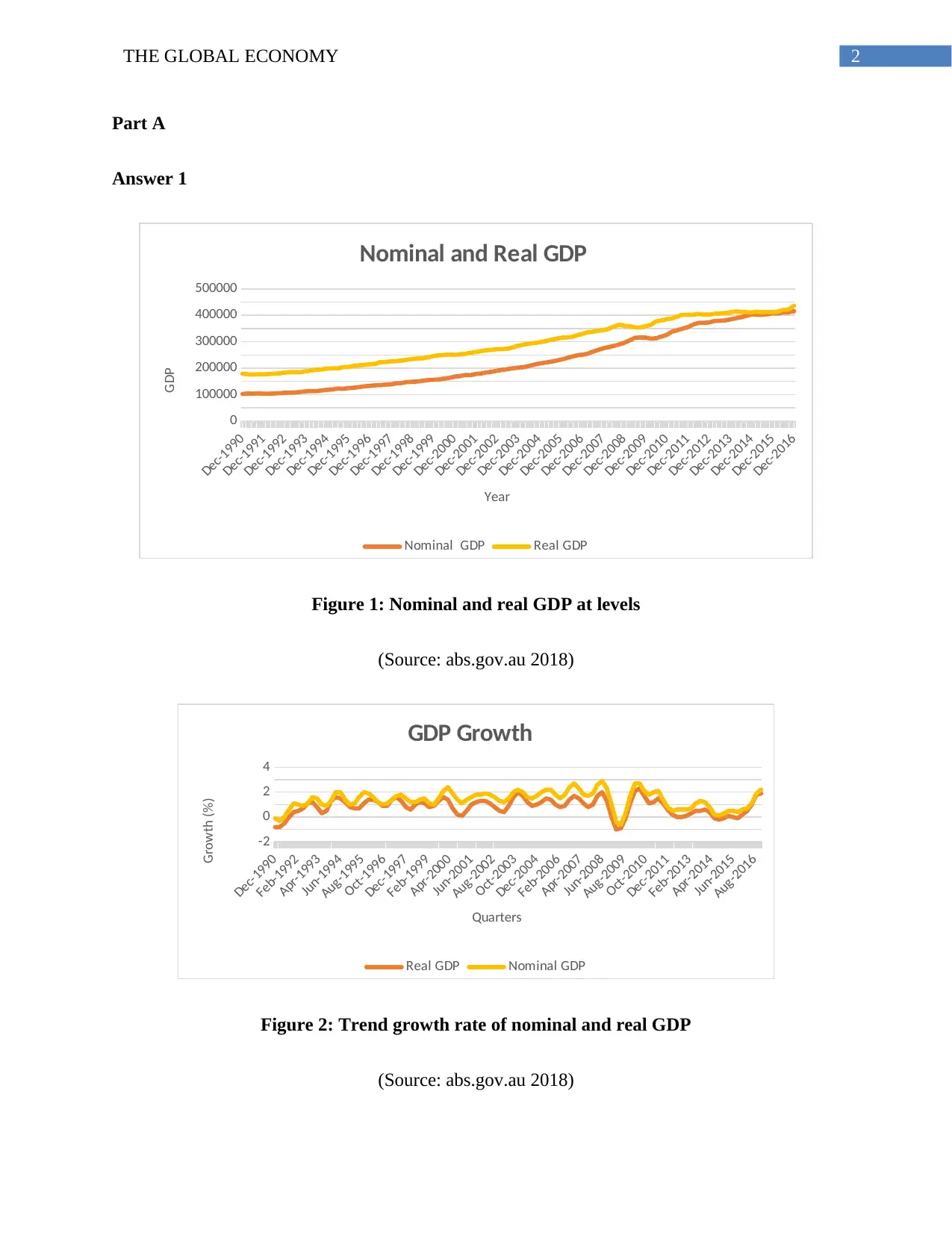

The monetary value of nation output is measured using Gross Domestic Demand. In

computation of GDP the market price of the goods or services are required along with their

volume. In case of nominal GDP, goods are valued in current prices. When output is valued in at

a constant fixed year prices, then it is called real GDP. As a fixed base year is used in computing

real GDP, the output value is adjusted for inflation giving a more accurate measure of output (De

Vroey 2016). An increase in nominal GDP cause an increase or decrease in real GDP depending

on the price level.

In Australia, both the nominal and real GDP increases overtime indicating an increase in

overall output and economic expansion. With a greater control over the level of prices, the

nominal and real GDP gradually approaching towards each other. The measure of trend growth

rate shows that nominal GDP grows faster than real GDP. The deflationary pressure caused by a

unfavorable terms of trade contributes to an increases in real GDP growth rate to catch up the

nominal GDP growth.

Answer 2

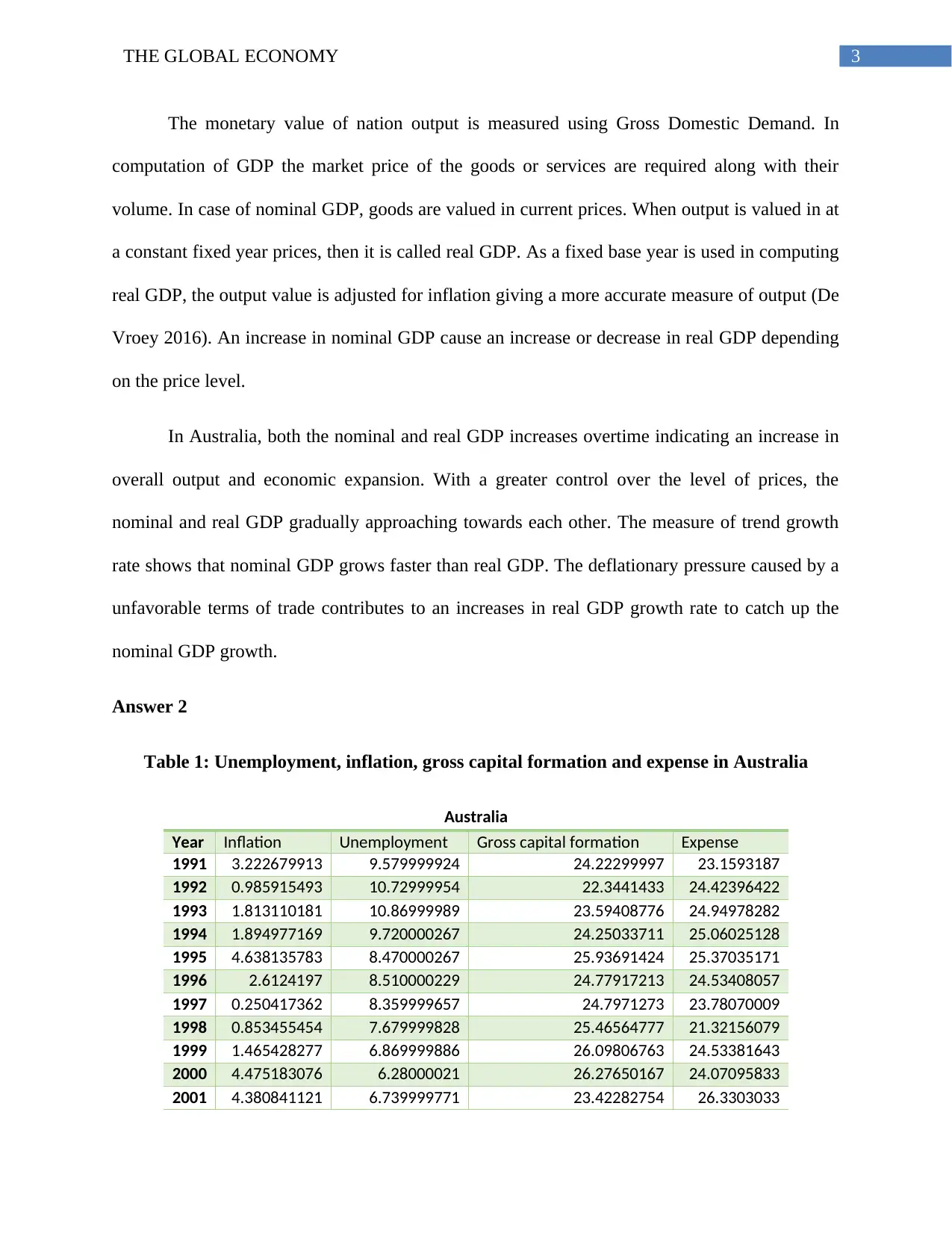

Table 1: Unemployment, inflation, gross capital formation and expense in Australia

Australia

Year Inflation Unemployment Gross capital formation Expense

1991 3.222679913 9.579999924 24.22299997 23.1593187

1992 0.985915493 10.72999954 22.3441433 24.42396422

1993 1.813110181 10.86999989 23.59408776 24.94978282

1994 1.894977169 9.720000267 24.25033711 25.06025128

1995 4.638135783 8.470000267 25.93691424 25.37035171

1996 2.6124197 8.510000229 24.77917213 24.53408057

1997 0.250417362 8.359999657 24.7971273 23.78070009

1998 0.853455454 7.679999828 25.46564777 21.32156079

1999 1.465428277 6.869999886 26.09806763 24.53381643

2000 4.475183076 6.28000021 26.27650167 24.07095833

2001 4.380841121 6.739999771 23.42282754 26.3303033

The monetary value of nation output is measured using Gross Domestic Demand. In

computation of GDP the market price of the goods or services are required along with their

volume. In case of nominal GDP, goods are valued in current prices. When output is valued in at

a constant fixed year prices, then it is called real GDP. As a fixed base year is used in computing

real GDP, the output value is adjusted for inflation giving a more accurate measure of output (De

Vroey 2016). An increase in nominal GDP cause an increase or decrease in real GDP depending

on the price level.

In Australia, both the nominal and real GDP increases overtime indicating an increase in

overall output and economic expansion. With a greater control over the level of prices, the

nominal and real GDP gradually approaching towards each other. The measure of trend growth

rate shows that nominal GDP grows faster than real GDP. The deflationary pressure caused by a

unfavorable terms of trade contributes to an increases in real GDP growth rate to catch up the

nominal GDP growth.

Answer 2

Table 1: Unemployment, inflation, gross capital formation and expense in Australia

Australia

Year Inflation Unemployment Gross capital formation Expense

1991 3.222679913 9.579999924 24.22299997 23.1593187

1992 0.985915493 10.72999954 22.3441433 24.42396422

1993 1.813110181 10.86999989 23.59408776 24.94978282

1994 1.894977169 9.720000267 24.25033711 25.06025128

1995 4.638135783 8.470000267 25.93691424 25.37035171

1996 2.6124197 8.510000229 24.77917213 24.53408057

1997 0.250417362 8.359999657 24.7971273 23.78070009

1998 0.853455454 7.679999828 25.46564777 21.32156079

1999 1.465428277 6.869999886 26.09806763 24.53381643

2000 4.475183076 6.28000021 26.27650167 24.07095833

2001 4.380841121 6.739999771 23.42282754 26.3303033

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

2002 3.00317105 6.369999886 24.39965103 26.44611444

2003 2.770735241 5.929999828 25.9254454 25.8340018

2004 2.343612335 5.389999866 27.06087433 25.67329182

2005 2.668732782 5.03000021 27.4254073 25.61578597

2006 3.538487339 4.78000021 27.65794856 24.92062761

2007 2.332361516 4.380000114 27.84585816 24.47849996

2008 4.352643242 4.230000019 29.12600769 24.31734064

2009 1.82011224 5.559999943 27.90602567 26.482355

2010 2.845225682 5.210000038 27.5528937 26.77540331

2011 3.303850156 5.079999924 27.11341551 25.96923518

2012 1.762780156 5.21999979 28.32663311 26.24604405

2013 2.449888641 5.659999847 28.44050751 25.98320556

2014 2.487922705 6.070000172 27.20492597 26.40565053

2015 1.508366722 6.059999943 26.73764514 26.86225739

2016 1.276990945 5.71999979 25.53702298 27.03986551

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

Table 2: unemployment, Inflation, gross capital formation and expense in United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Year Inflation Unemploymen

t

Gross capital

formation

Expense

1991 7.532649 8.55 19.59018 34.78408

1992 4.261548 9.78 18.83031 37.64063

1993 2.5065 10.35 18.37509 37.36898

1994 1.97849 9.65 19.37552 37.07977

1995 2.656452 8.69 18.63725 35.24609

1996 2.481101 8.19 18.84126 34.02947

1997 1.777946 7.07 18.01168 32.9629

1998 1.588924 6.2 18.62629 32.36898

1999 1.335407 6.04 18.0644 32.16804

2000 0.785269 5.56 18.46573 32.54879

2001 1.235895 4.7 17.8566 33.12253

2002 1.256192 5.04 17.76296 34.23308

2003 1.362922 4.81 17.38414 35.58366

2004 1.344596 4.59 17.02408 36.16253

2005 2.049668 4.75 17.21945 36.6333

2006 2.333528 5.35 17.59422 36.70877

2007 2.321036 5.26 18.11053 36.92255

2008 3.613499 5.62 16.99368 39.87988

2009 2.166231 7.54 14.42836 42.31741

2010 3.285714 7.79 15.67951 43.10665

2002 3.00317105 6.369999886 24.39965103 26.44611444

2003 2.770735241 5.929999828 25.9254454 25.8340018

2004 2.343612335 5.389999866 27.06087433 25.67329182

2005 2.668732782 5.03000021 27.4254073 25.61578597

2006 3.538487339 4.78000021 27.65794856 24.92062761

2007 2.332361516 4.380000114 27.84585816 24.47849996

2008 4.352643242 4.230000019 29.12600769 24.31734064

2009 1.82011224 5.559999943 27.90602567 26.482355

2010 2.845225682 5.210000038 27.5528937 26.77540331

2011 3.303850156 5.079999924 27.11341551 25.96923518

2012 1.762780156 5.21999979 28.32663311 26.24604405

2013 2.449888641 5.659999847 28.44050751 25.98320556

2014 2.487922705 6.070000172 27.20492597 26.40565053

2015 1.508366722 6.059999943 26.73764514 26.86225739

2016 1.276990945 5.71999979 25.53702298 27.03986551

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

Table 2: unemployment, Inflation, gross capital formation and expense in United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Year Inflation Unemploymen

t

Gross capital

formation

Expense

1991 7.532649 8.55 19.59018 34.78408

1992 4.261548 9.78 18.83031 37.64063

1993 2.5065 10.35 18.37509 37.36898

1994 1.97849 9.65 19.37552 37.07977

1995 2.656452 8.69 18.63725 35.24609

1996 2.481101 8.19 18.84126 34.02947

1997 1.777946 7.07 18.01168 32.9629

1998 1.588924 6.2 18.62629 32.36898

1999 1.335407 6.04 18.0644 32.16804

2000 0.785269 5.56 18.46573 32.54879

2001 1.235895 4.7 17.8566 33.12253

2002 1.256192 5.04 17.76296 34.23308

2003 1.362922 4.81 17.38414 35.58366

2004 1.344596 4.59 17.02408 36.16253

2005 2.049668 4.75 17.21945 36.6333

2006 2.333528 5.35 17.59422 36.70877

2007 2.321036 5.26 18.11053 36.92255

2008 3.613499 5.62 16.99368 39.87988

2009 2.166231 7.54 14.42836 42.31741

2010 3.285714 7.79 15.67951 43.10665

5THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

2011 4.48424 8.04 15.55917 41.83205

2012 2.82171 7.89 15.75748 42.46923

2013 2.554547 7.53 16.35796 40.15876

2014 1.460192 6.11 17.11075 39.28458

2015 0.050021 5.3 16.97235 38.41641

2016 0.641613 4.81 16.96858 37.29929

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

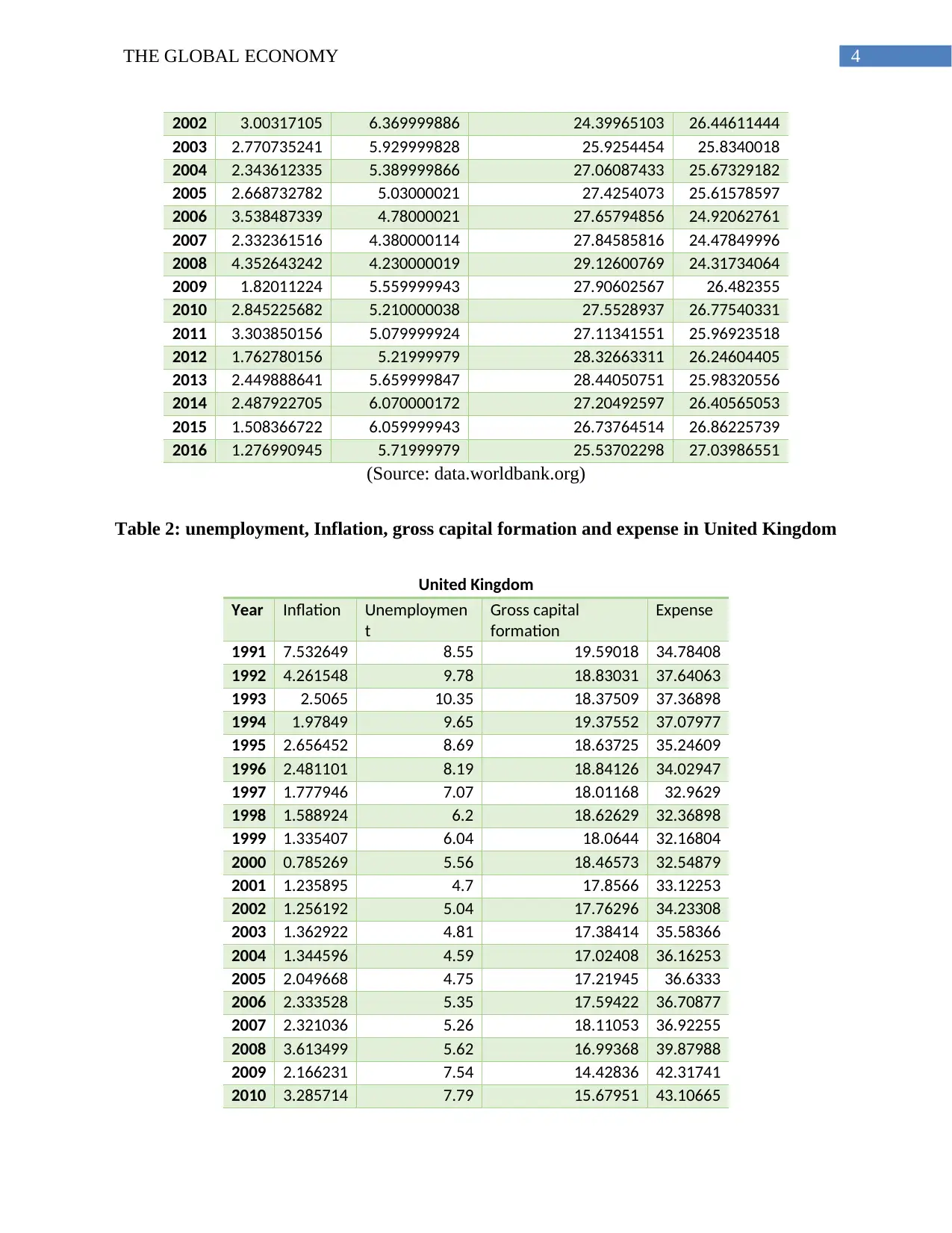

Table 3: unemployment, Inflation, gross capital formation and expense in South Korea

South Korea

Year Inflation Unemployment Gross capital formation Expense

1991 9.3 2.410000086 41.37406165 13.3792593

1992 6.306306 2.50999999 38.48519801 13.62914127

1993 4.745763 2.880000114 37.47954115 13.33489425

1994 6.256742 2.480000019 38.5391289 13.41987061

1995 4.479695 2.059999943 39.0032945 13.29596568

1996 4.923429 2.049999952 39.68096241 13.51745684

1997 4.446869 2.609999895 37.42467905 13.33786873

1998 7.51208 6.960000038 27.76189528 15.64550787

1999 0.811448 6.340000153 30.91629559 15.22116193

2000 2.265333 4.420000076 32.9417149 15.78950954

2001 4.06642 4 31.55958695 16.77824298

2002 2.762511 3.279999971 30.93958059 15.90158752

2003 3.514879 3.559999943 32.01490957 17.86543884

2004 3.590591 3.670000076 32.11707412 17.80394405

2005 2.75409 3.730000019 32.16306462 18.54888028

2006 2.241847 3.450000048 32.70068793 19.31135155

2007 2.534847 3.230000019 32.57953116 18.82266703

2008 4.673796 3.160000086 33.01850389 19.14187425

2009 2.756686 3.640000105 28.4656577 20.20127708

2010 2.939181 3.720000029 32.02287506 18.42542179

2011 4.025846 3.410000086 32.95883261 18.90133685

2012 2.187221 3.220000029 31.00122857 25.75391299

2013 1.301377 3.119999886 29.10221685 25.23258321

2014 1.2748 3.529999971 29.27691005 24.84029804

2015 0.706963 3.630000114 28.91811192 24.89953205

2016 0.97 3.710000038 29.20956543 24.98822488

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

Table 4: unemployment, Inflation, gross capital formation and expense in Japan

2011 4.48424 8.04 15.55917 41.83205

2012 2.82171 7.89 15.75748 42.46923

2013 2.554547 7.53 16.35796 40.15876

2014 1.460192 6.11 17.11075 39.28458

2015 0.050021 5.3 16.97235 38.41641

2016 0.641613 4.81 16.96858 37.29929

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

Table 3: unemployment, Inflation, gross capital formation and expense in South Korea

South Korea

Year Inflation Unemployment Gross capital formation Expense

1991 9.3 2.410000086 41.37406165 13.3792593

1992 6.306306 2.50999999 38.48519801 13.62914127

1993 4.745763 2.880000114 37.47954115 13.33489425

1994 6.256742 2.480000019 38.5391289 13.41987061

1995 4.479695 2.059999943 39.0032945 13.29596568

1996 4.923429 2.049999952 39.68096241 13.51745684

1997 4.446869 2.609999895 37.42467905 13.33786873

1998 7.51208 6.960000038 27.76189528 15.64550787

1999 0.811448 6.340000153 30.91629559 15.22116193

2000 2.265333 4.420000076 32.9417149 15.78950954

2001 4.06642 4 31.55958695 16.77824298

2002 2.762511 3.279999971 30.93958059 15.90158752

2003 3.514879 3.559999943 32.01490957 17.86543884

2004 3.590591 3.670000076 32.11707412 17.80394405

2005 2.75409 3.730000019 32.16306462 18.54888028

2006 2.241847 3.450000048 32.70068793 19.31135155

2007 2.534847 3.230000019 32.57953116 18.82266703

2008 4.673796 3.160000086 33.01850389 19.14187425

2009 2.756686 3.640000105 28.4656577 20.20127708

2010 2.939181 3.720000029 32.02287506 18.42542179

2011 4.025846 3.410000086 32.95883261 18.90133685

2012 2.187221 3.220000029 31.00122857 25.75391299

2013 1.301377 3.119999886 29.10221685 25.23258321

2014 1.2748 3.529999971 29.27691005 24.84029804

2015 0.706963 3.630000114 28.91811192 24.89953205

2016 0.97 3.710000038 29.20956543 24.98822488

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

Table 4: unemployment, Inflation, gross capital formation and expense in Japan

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

Japan

Year Inflation Unemploymen

t

Gross capital

formation

Expense

1991 3.29806 2.09 33.93256909 29.68

1992 1.707359 2.16 32.16449203 30.57

1993 1.267416 2.51 30.77640483 32.37

1994 0.68794 2.89 29.54485774 15.23929

1995 -0.12348 3.15 29.88285636 15.22473

1996 0.131872 3.35 30.86515221 15.1676

1997 1.761462 3.39 29.95099622 14.63257

1998 0.663269 4.11 28.51517087 20.39496

1999 -0.32945 4.68 27.11881302 17.542

2000 -0.65302 4.73 27.30713149 17.34241

2001 -0.74006 5.04 26.56051089 16.46877

2002 -0.92349 5.37 24.65550435 16.36226

2003 -0.25654 5.25 24.39723113 15.97741

2004 -0.00857 4.71 24.34862277 15.34087

2005 -0.28295 4.42 24.74947189 15.31547

2006 0.249355 4.13 24.74862858 15.07756

2007 0.060039 3.85 24.48344725 14.17419

2008 1.380079 3.98 24.54784828 15.46619

2009 -1.35284 5.08 21.32367452 18.40497

2010 -0.71998 5.07 21.29748564 17.39946

2011 -0.26763 4.55 22.10330102 18.8211

2012 -0.05194 4.35 22.65442345 18.33817

2013 0.34644 4.03 23.19090989 18.34244

2014 2.761954 3.58 23.91610038 17.77248

2015 0.789518 3.33 24.0053024 17.14929

2016 -0.11667 3.13 23.56428446 16.93938

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

Table 5: unemployment, Inflation, gross capital formation and expense in China

China

Year Inflation Unemployment Gross capital formation Expens

e

1991 3.556686 4.889999866 35.8658256 16.55

1992 6.353981 4.389999866 39.83722181 14.65

1993 14.61008 4.329999924 44.24292895 13.41

1994 24.25734 4.340000153 40.94850525 12.36

1995 16.78945 4.550000191 39.68463866 11.09

1996 8.312847 4.590000153 38.37235534 11.01

Japan

Year Inflation Unemploymen

t

Gross capital

formation

Expense

1991 3.29806 2.09 33.93256909 29.68

1992 1.707359 2.16 32.16449203 30.57

1993 1.267416 2.51 30.77640483 32.37

1994 0.68794 2.89 29.54485774 15.23929

1995 -0.12348 3.15 29.88285636 15.22473

1996 0.131872 3.35 30.86515221 15.1676

1997 1.761462 3.39 29.95099622 14.63257

1998 0.663269 4.11 28.51517087 20.39496

1999 -0.32945 4.68 27.11881302 17.542

2000 -0.65302 4.73 27.30713149 17.34241

2001 -0.74006 5.04 26.56051089 16.46877

2002 -0.92349 5.37 24.65550435 16.36226

2003 -0.25654 5.25 24.39723113 15.97741

2004 -0.00857 4.71 24.34862277 15.34087

2005 -0.28295 4.42 24.74947189 15.31547

2006 0.249355 4.13 24.74862858 15.07756

2007 0.060039 3.85 24.48344725 14.17419

2008 1.380079 3.98 24.54784828 15.46619

2009 -1.35284 5.08 21.32367452 18.40497

2010 -0.71998 5.07 21.29748564 17.39946

2011 -0.26763 4.55 22.10330102 18.8211

2012 -0.05194 4.35 22.65442345 18.33817

2013 0.34644 4.03 23.19090989 18.34244

2014 2.761954 3.58 23.91610038 17.77248

2015 0.789518 3.33 24.0053024 17.14929

2016 -0.11667 3.13 23.56428446 16.93938

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

Table 5: unemployment, Inflation, gross capital formation and expense in China

China

Year Inflation Unemployment Gross capital formation Expens

e

1991 3.556686 4.889999866 35.8658256 16.55

1992 6.353981 4.389999866 39.83722181 14.65

1993 14.61008 4.329999924 44.24292895 13.41

1994 24.25734 4.340000153 40.94850525 12.36

1995 16.78945 4.550000191 39.68463866 11.09

1996 8.312847 4.590000153 38.37235534 11.01

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

1997 2.787113 4.599999905 36.33715573 11.54

1998 -0.84954 4.730000019 35.67868627 12.63

1999 -1.35851 4.699999809 34.96477981 14.9

2000 0.256518 4.53000021 34.42965254 16.14

2001 0.719808 4.53000021 36.42225471 17.31

2002 -0.76672 4.409999847 37.07754181 18.32

2003 1.164518 4.300000191 40.63154952 18.07

2004 3.888816 4.300000191 42.89449013 17.72

2005 1.813995 4.139999866 41.3912114 18.12

2006 1.466078 4 40.93327269 18.2

2007 4.767211 3.75999999 41.46315155 18.07

2008 5.843024 4.360000134 43.26637446 22.39

2009 -0.70063 4.288000107 46.44130408 25.52

2010 3.325775 4.199999809 47.61226023 24.96

2011 5.410918 4.340000153 47.68586754 27.01

2012 2.643052 4.46999979 47.23453111 28.06

2013 2.628086 4.539999962 47.38775199 28.54

2014 2.000345 4.592999935 47.00771662 28.97

2015 1.437025 4.605000019 45.40088041 31.32

2016 2 4.649000168 44.31060661 31.95

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Inflation

Inflation (AUS) Inflation (China) Inflation (South Korea

Inflation (Japan) Inflation (UK)

Year

Inflation rate

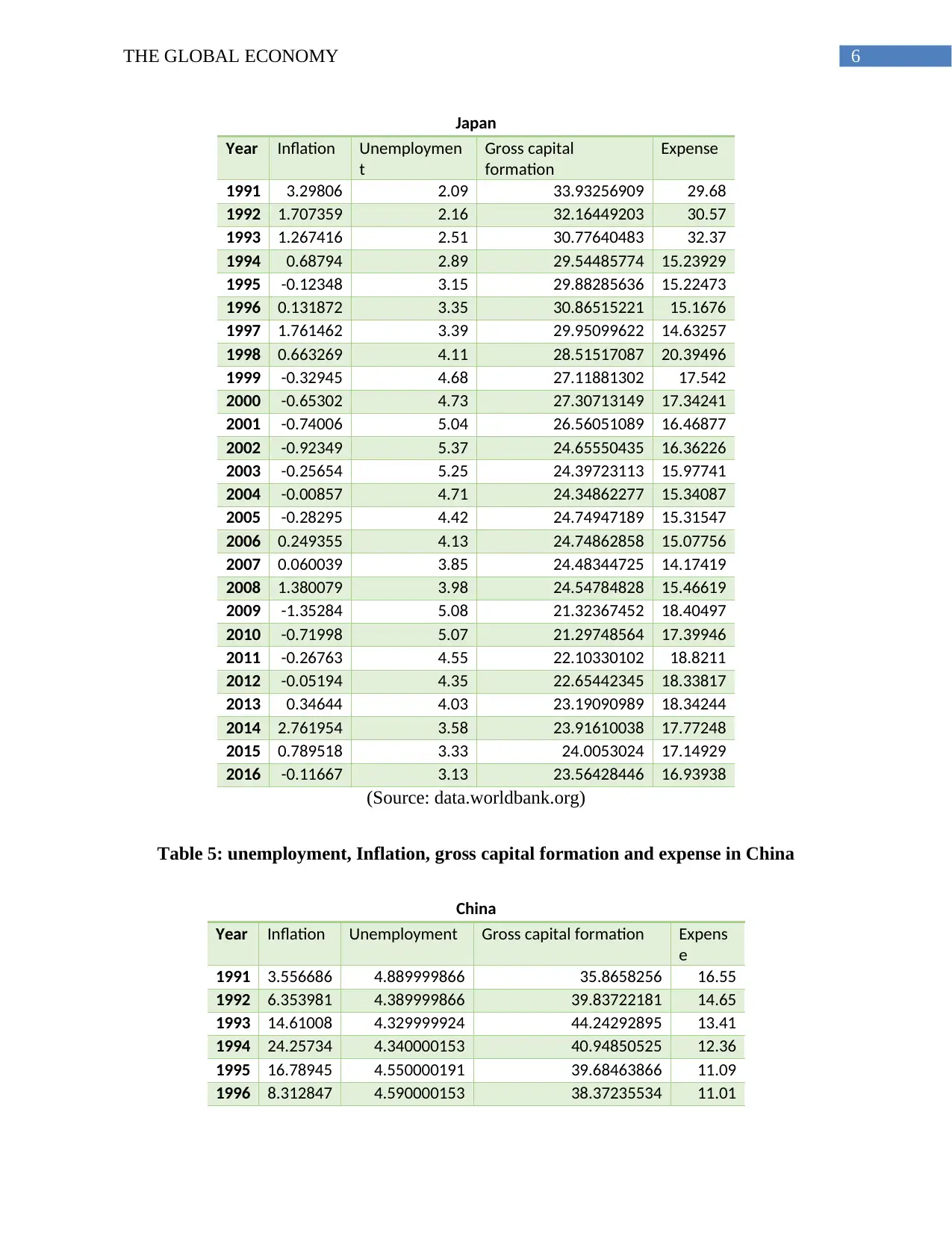

Figure 3: Trend in inflation for five countries together

1997 2.787113 4.599999905 36.33715573 11.54

1998 -0.84954 4.730000019 35.67868627 12.63

1999 -1.35851 4.699999809 34.96477981 14.9

2000 0.256518 4.53000021 34.42965254 16.14

2001 0.719808 4.53000021 36.42225471 17.31

2002 -0.76672 4.409999847 37.07754181 18.32

2003 1.164518 4.300000191 40.63154952 18.07

2004 3.888816 4.300000191 42.89449013 17.72

2005 1.813995 4.139999866 41.3912114 18.12

2006 1.466078 4 40.93327269 18.2

2007 4.767211 3.75999999 41.46315155 18.07

2008 5.843024 4.360000134 43.26637446 22.39

2009 -0.70063 4.288000107 46.44130408 25.52

2010 3.325775 4.199999809 47.61226023 24.96

2011 5.410918 4.340000153 47.68586754 27.01

2012 2.643052 4.46999979 47.23453111 28.06

2013 2.628086 4.539999962 47.38775199 28.54

2014 2.000345 4.592999935 47.00771662 28.97

2015 1.437025 4.605000019 45.40088041 31.32

2016 2 4.649000168 44.31060661 31.95

(Source: data.worldbank.org)

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Inflation

Inflation (AUS) Inflation (China) Inflation (South Korea

Inflation (Japan) Inflation (UK)

Year

Inflation rate

Figure 3: Trend in inflation for five countries together

8THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

Australia

Unemployment Gross capital formation Expense

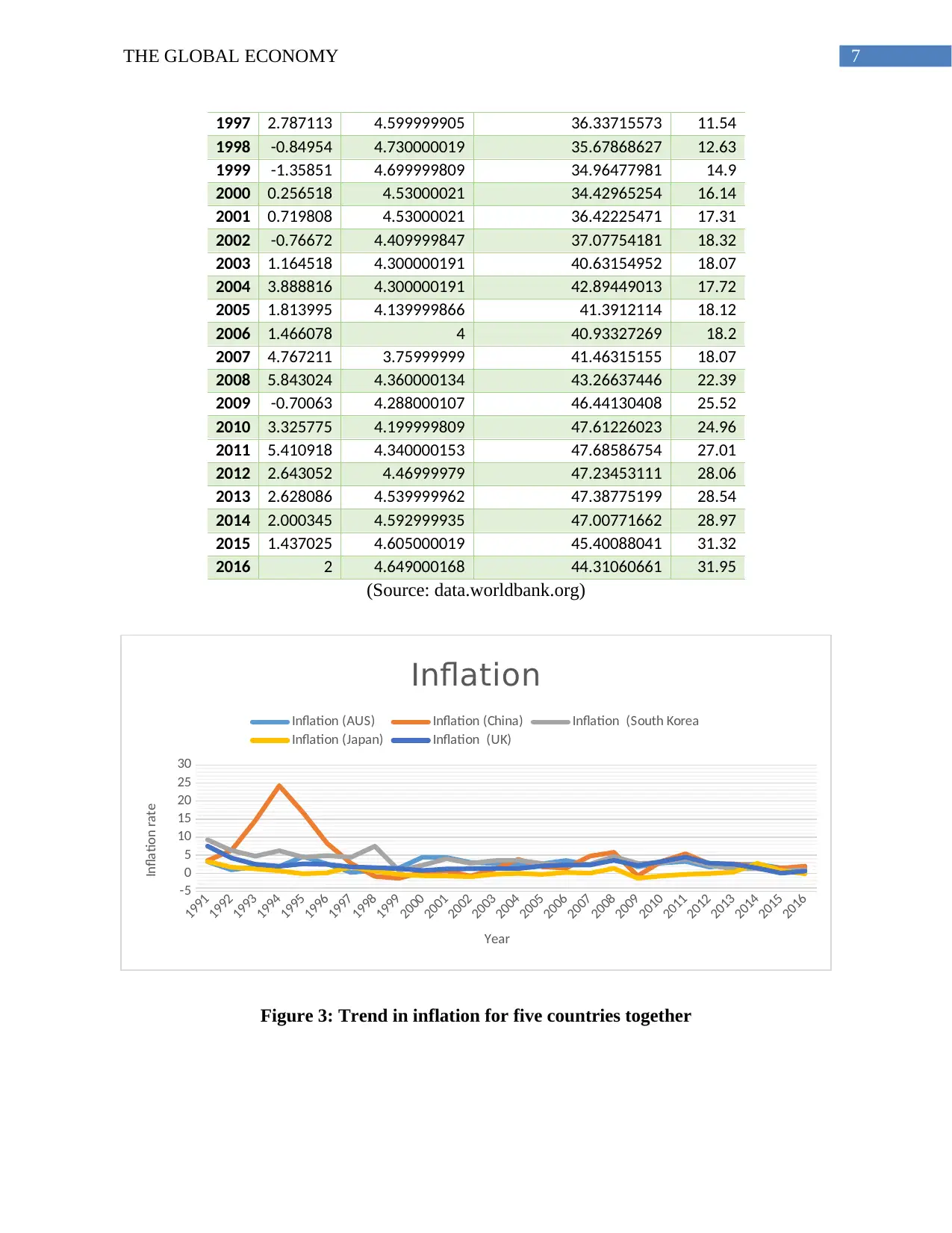

Figure 4: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in Australia

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

China

Gross capital formation Expense Unemployment

Figure 5: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in China

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

Australia

Unemployment Gross capital formation Expense

Figure 4: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in Australia

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

China

Gross capital formation Expense Unemployment

Figure 5: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in China

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

United Kingdom

Gross capital formation Expense Unemployment

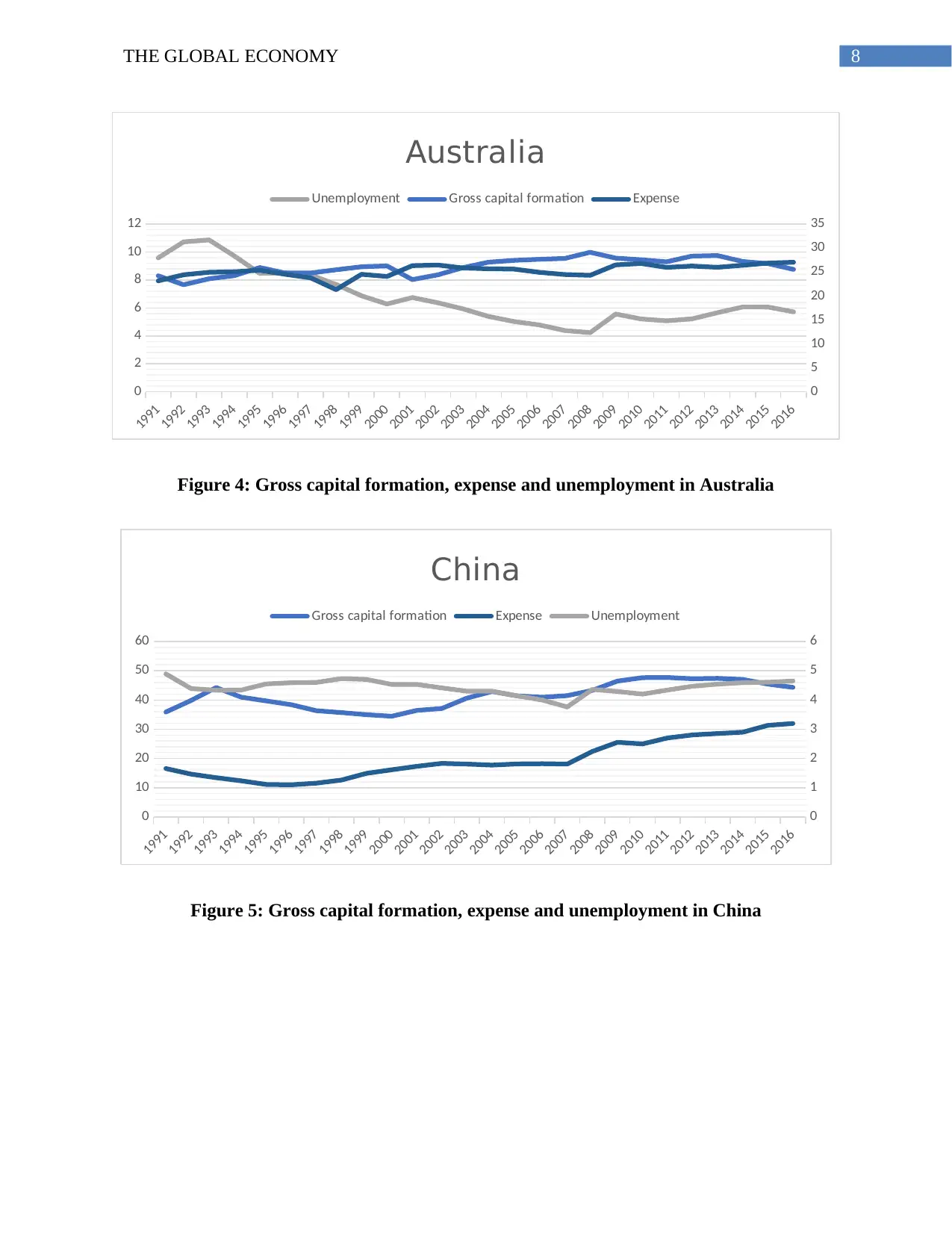

Figure 6: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in United Kingdom

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

South Korea

Gross capital formation Expense Unemployment

Figure 7: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in South Korea

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

United Kingdom

Gross capital formation Expense Unemployment

Figure 6: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in United Kingdom

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

South Korea

Gross capital formation Expense Unemployment

Figure 7: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in South Korea

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Japan

Gross capital formation Expense

Unemployment

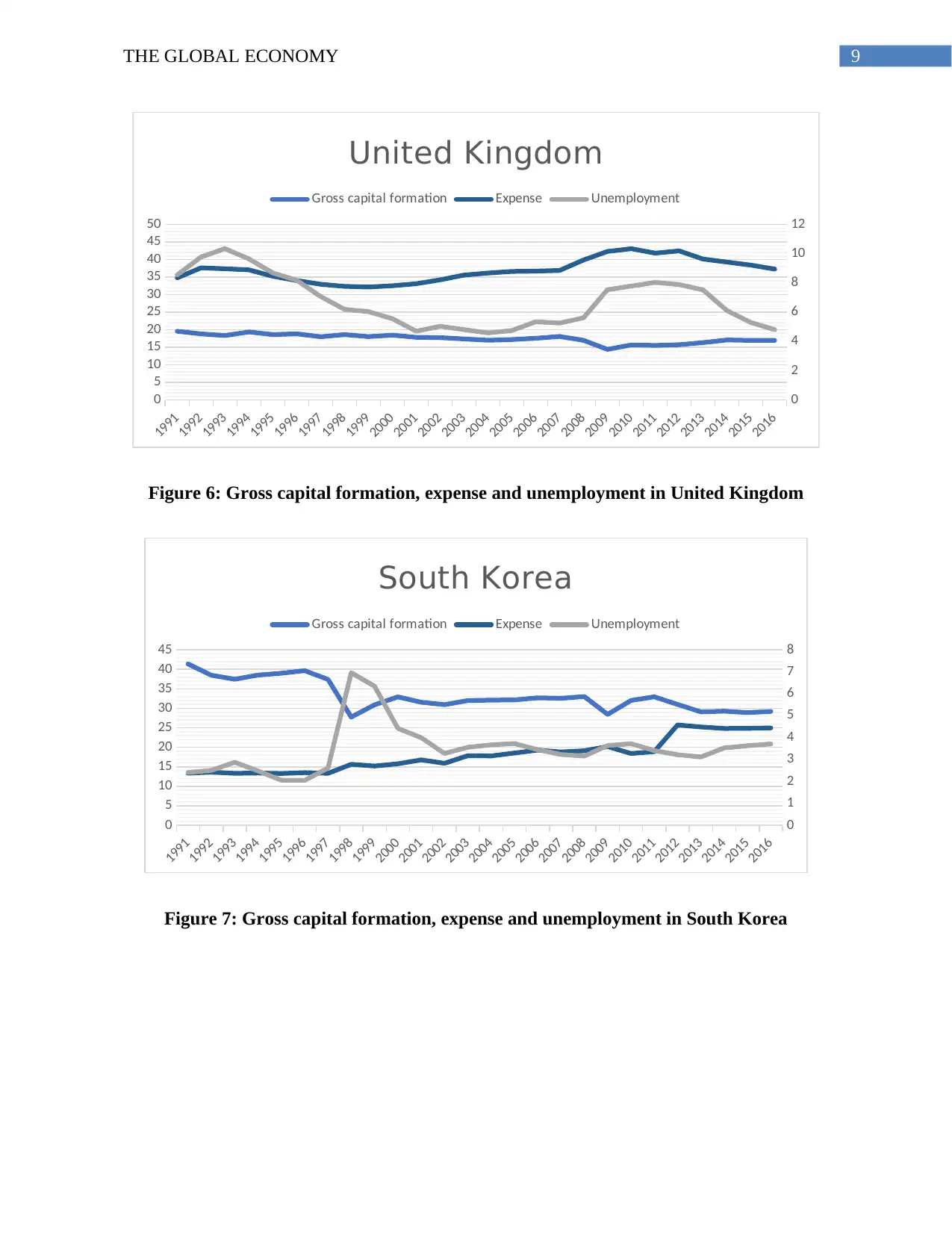

Figure 8: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in Japan

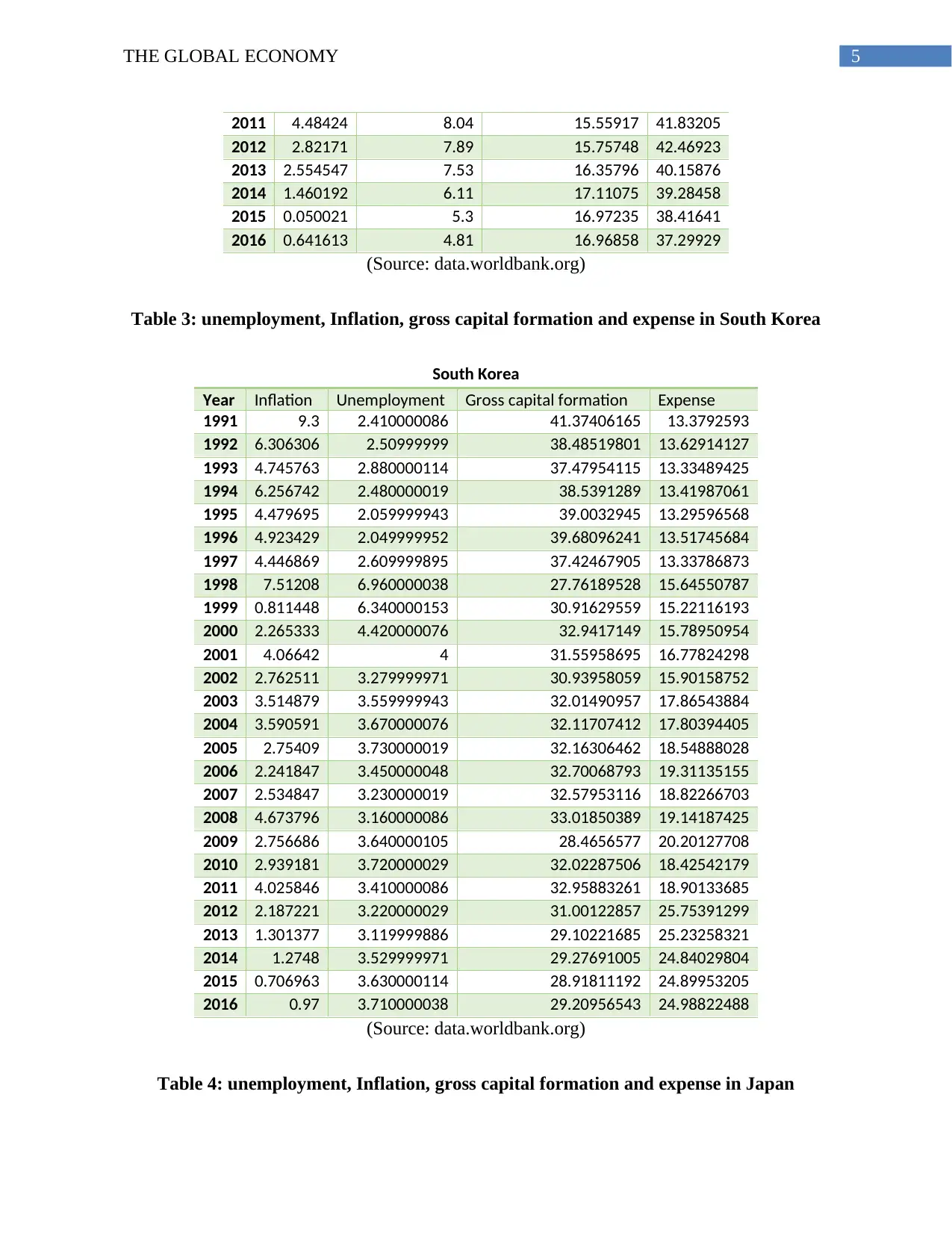

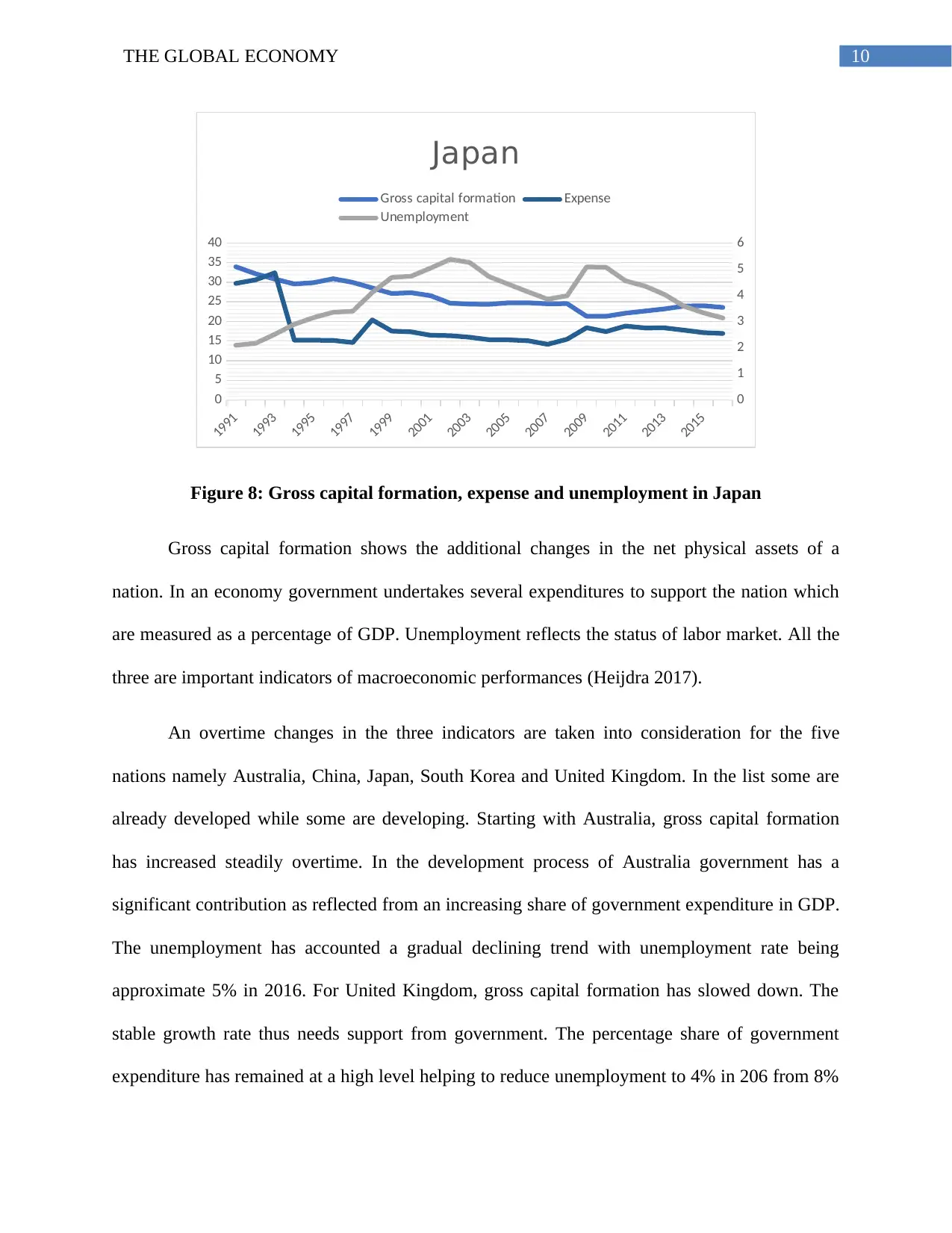

Gross capital formation shows the additional changes in the net physical assets of a

nation. In an economy government undertakes several expenditures to support the nation which

are measured as a percentage of GDP. Unemployment reflects the status of labor market. All the

three are important indicators of macroeconomic performances (Heijdra 2017).

An overtime changes in the three indicators are taken into consideration for the five

nations namely Australia, China, Japan, South Korea and United Kingdom. In the list some are

already developed while some are developing. Starting with Australia, gross capital formation

has increased steadily overtime. In the development process of Australia government has a

significant contribution as reflected from an increasing share of government expenditure in GDP.

The unemployment has accounted a gradual declining trend with unemployment rate being

approximate 5% in 2016. For United Kingdom, gross capital formation has slowed down. The

stable growth rate thus needs support from government. The percentage share of government

expenditure has remained at a high level helping to reduce unemployment to 4% in 206 from 8%

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Japan

Gross capital formation Expense

Unemployment

Figure 8: Gross capital formation, expense and unemployment in Japan

Gross capital formation shows the additional changes in the net physical assets of a

nation. In an economy government undertakes several expenditures to support the nation which

are measured as a percentage of GDP. Unemployment reflects the status of labor market. All the

three are important indicators of macroeconomic performances (Heijdra 2017).

An overtime changes in the three indicators are taken into consideration for the five

nations namely Australia, China, Japan, South Korea and United Kingdom. In the list some are

already developed while some are developing. Starting with Australia, gross capital formation

has increased steadily overtime. In the development process of Australia government has a

significant contribution as reflected from an increasing share of government expenditure in GDP.

The unemployment has accounted a gradual declining trend with unemployment rate being

approximate 5% in 2016. For United Kingdom, gross capital formation has slowed down. The

stable growth rate thus needs support from government. The percentage share of government

expenditure has remained at a high level helping to reduce unemployment to 4% in 206 from 8%

11THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

in 1991. China has recorded a stable unemployment rate of 4% with a high share of government

expenditure and gross capital formation. In Japan, government expense does not show any

significant and gross capital formation also shows a declining trend. The unemployment rate

though decreases recently but is higher than that in 1991. For South Korea, gross capital

formation declines overtime with a slow progress of the share of government expense. As like

Japan, South Korea also though the unemployment rate declines in recent years but it is higher

than the initial level.

A comparative analysis now can be made based on the performance of these indicators.

In the developed nations like Australia and United Kingdom, share of government expense is

much higher than that in China, Japan and South Korea. Despite a small share of government

expenditure, the unemployment rate in these three nation is either same or lower than that in

Australia and United Kingdom. The gross capital formation follows an increasing trend for china

and Australia while the rest three shows a declining trend.

01-Jan-1991

01-May-1992

01-Sep-1993

01-Jan-1995

01-May-1996

01-Sep-1997

01-Jan-1999

01-May-2000

01-Sep-2001

01-Jan-2003

01-May-2004

01-Sep-2005

01-Jan-2007

01-May-2008

01-Sep-2009

01-Jan-2011

01-May-2012

01-Sep-2013

01-Jan-2015

01-May-2016-5000

-4000

-3000

-2000

-1000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

0.0000

0.1000

0.2000

0.3000

0.4000

0.5000

0.6000

0.7000

0.8000

Balance of Trade AUD/GBP

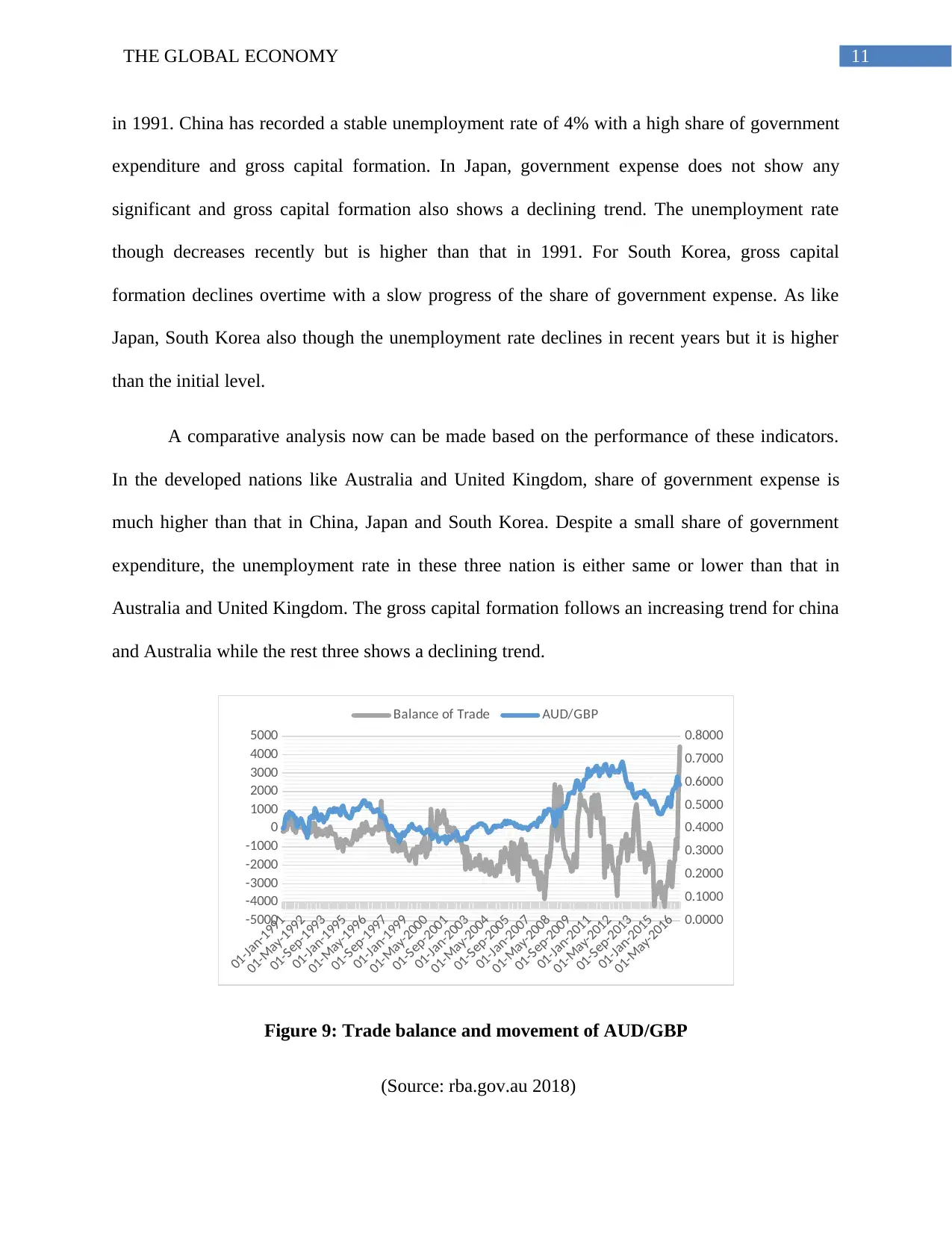

Figure 9: Trade balance and movement of AUD/GBP

(Source: rba.gov.au 2018)

in 1991. China has recorded a stable unemployment rate of 4% with a high share of government

expenditure and gross capital formation. In Japan, government expense does not show any

significant and gross capital formation also shows a declining trend. The unemployment rate

though decreases recently but is higher than that in 1991. For South Korea, gross capital

formation declines overtime with a slow progress of the share of government expense. As like

Japan, South Korea also though the unemployment rate declines in recent years but it is higher

than the initial level.

A comparative analysis now can be made based on the performance of these indicators.

In the developed nations like Australia and United Kingdom, share of government expense is

much higher than that in China, Japan and South Korea. Despite a small share of government

expenditure, the unemployment rate in these three nation is either same or lower than that in

Australia and United Kingdom. The gross capital formation follows an increasing trend for china

and Australia while the rest three shows a declining trend.

01-Jan-1991

01-May-1992

01-Sep-1993

01-Jan-1995

01-May-1996

01-Sep-1997

01-Jan-1999

01-May-2000

01-Sep-2001

01-Jan-2003

01-May-2004

01-Sep-2005

01-Jan-2007

01-May-2008

01-Sep-2009

01-Jan-2011

01-May-2012

01-Sep-2013

01-Jan-2015

01-May-2016-5000

-4000

-3000

-2000

-1000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

0.0000

0.1000

0.2000

0.3000

0.4000

0.5000

0.6000

0.7000

0.8000

Balance of Trade AUD/GBP

Figure 9: Trade balance and movement of AUD/GBP

(Source: rba.gov.au 2018)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 22

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.