Drug Legalization: Pros and Cons

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/22

|10

|6964

|225

Essay

AI Summary

This essay comprehensively examines the multifaceted debate surrounding drug legalization. It presents a framework for understanding the advantages and disadvantages of both legalization and prohibition, considering factors such as black market crime, violence, regulation costs, and effects on youth. The essay delves into the economic aspects of drug markets, including price elasticity of demand and the impact of price changes on consumption. It also explores alternative policy options, such as decriminalization and harm reduction strategies, highlighting the complexities of implementing effective drug policies. The author emphasizes the need for a balanced perspective, avoiding the rhetoric often associated with this contentious issue and aiming to provide readers with a nuanced understanding of the challenges involved.

The immense harms that drugs (illicit drugs, alcohol, and tobacco) cause both users and

nonusers have prompted many governments to impose strictly enforced bans on production and

possession of some of these substances. Such bans can help constrain drug use. However,

prohibition also causes its own harms, including harms from black market crime and

violence. Drug legalization would ameliorate the black-market harms, but increase some other

harms by decreasing price and thus increasing use and dependence. This paper gives readers a

framework for understanding the pros and cons of legalization, and some of its complexities,

including the differences between state and national level legalization, the monetary and human

costs of regulation and enforcement, and effects of different policies on youth. It also discusses

"middle path" policy options, such as decriminalization, policy changes under prohibition, and

harm reduction. The aim is to peel away the rhetoric of the drug legalization/prohibition debate,

not to argue for any specific policy.

Keywords: Substance abuse, legalization

Introduction

In a sense, drugs are just consumer goods, like doughnuts and dietary supplements. But caveat

emptor is no longer the rule for even routine consumer goods. Doughnut shops must comply with

public health inspections, and nutraceutical manufacturers must follow good manufacturing

practices, eschew false labeling, and report the adverse effects of their products. Regulation is

not the same as prohibition, though. Governments generally do not block the open market from

catering to consumer desires.

There are exceptions, often rooted in cultural or religious mores. Both Judaism and Islam

proscribe pork, a ban that several Muslim-majority states have incorporated into their national

laws. Prohibitions of consumer goods are less common in contemporary secular societies, but

still occur. Health, quality of life, ethics, and human rights concerns motivate laws forbidding

prostitution, child pornography, and human organ markets. Other bans protect non- humans,

such as those against the ivory and tropical hardwood trades. In 2006 Congress effectively

banned eating horse meat by withholding federal funds for required slaughterhouse inspections.

The prohibition remained in place for five years until the Obama Administration lifted it, even

though in many countries eating horse meat is no more controversial than eating beef.

Historically, intoxicants have been a frequent target of prohibitions. England's King James I tried

to prohibit tobacco in the 17th century, and alcohol has been subject to numerous bans. Neither

tobacco nor alcohol is prohibited in the United States today (a few "dry" counties aside), but the

Controlled Substance Act places scores of other psychoactive chemicals into one of five

"schedules" depending on their potential for abuse and their potential value in medicine.

Schedule I substances include heroin and marijuana (high potential for abuse, no recognized

medical value). Cocaine and methamphetamine are in Schedule II, despite high potential for

abuse, because they have medical uses (as a topical anesthetic and as a treatment for ADHD

and narcolepsy, respectively).

That drug use can harm users is, for some, sufficient justification for market intervention.

Consumers are usually left to deal with their own odd choices, but overdoses of pet rocks and

low-rider pants are not fatal. Drugs are different, so the argument goes, because they are so

seductive and dangerous. Drug-induced behavior can impair decision-making processes through

dependence or intoxicated reasoning; the "choice" to continue abusing drugs is something less

than completely free. Users may not fully understand the risks before initiating use. After all, the

great bulk of initiation is by adolescents and young adults, for whom immediate pleasures cloud

judgments involving probabilistic risks of adverse outcomes that are mostly in the future.

Precocious use is also a strong risk factor predicting subsequent dependence. Once users

become dependent, it can be psychologically and/or physically painful to abstain. Furthermore,

the minority of heavy users account for a disproportionate share of all drug consumption, which

means that a goodly share of all "decisions" to imbibe are made while judgment is impaired by

earlier doses.

nonusers have prompted many governments to impose strictly enforced bans on production and

possession of some of these substances. Such bans can help constrain drug use. However,

prohibition also causes its own harms, including harms from black market crime and

violence. Drug legalization would ameliorate the black-market harms, but increase some other

harms by decreasing price and thus increasing use and dependence. This paper gives readers a

framework for understanding the pros and cons of legalization, and some of its complexities,

including the differences between state and national level legalization, the monetary and human

costs of regulation and enforcement, and effects of different policies on youth. It also discusses

"middle path" policy options, such as decriminalization, policy changes under prohibition, and

harm reduction. The aim is to peel away the rhetoric of the drug legalization/prohibition debate,

not to argue for any specific policy.

Keywords: Substance abuse, legalization

Introduction

In a sense, drugs are just consumer goods, like doughnuts and dietary supplements. But caveat

emptor is no longer the rule for even routine consumer goods. Doughnut shops must comply with

public health inspections, and nutraceutical manufacturers must follow good manufacturing

practices, eschew false labeling, and report the adverse effects of their products. Regulation is

not the same as prohibition, though. Governments generally do not block the open market from

catering to consumer desires.

There are exceptions, often rooted in cultural or religious mores. Both Judaism and Islam

proscribe pork, a ban that several Muslim-majority states have incorporated into their national

laws. Prohibitions of consumer goods are less common in contemporary secular societies, but

still occur. Health, quality of life, ethics, and human rights concerns motivate laws forbidding

prostitution, child pornography, and human organ markets. Other bans protect non- humans,

such as those against the ivory and tropical hardwood trades. In 2006 Congress effectively

banned eating horse meat by withholding federal funds for required slaughterhouse inspections.

The prohibition remained in place for five years until the Obama Administration lifted it, even

though in many countries eating horse meat is no more controversial than eating beef.

Historically, intoxicants have been a frequent target of prohibitions. England's King James I tried

to prohibit tobacco in the 17th century, and alcohol has been subject to numerous bans. Neither

tobacco nor alcohol is prohibited in the United States today (a few "dry" counties aside), but the

Controlled Substance Act places scores of other psychoactive chemicals into one of five

"schedules" depending on their potential for abuse and their potential value in medicine.

Schedule I substances include heroin and marijuana (high potential for abuse, no recognized

medical value). Cocaine and methamphetamine are in Schedule II, despite high potential for

abuse, because they have medical uses (as a topical anesthetic and as a treatment for ADHD

and narcolepsy, respectively).

That drug use can harm users is, for some, sufficient justification for market intervention.

Consumers are usually left to deal with their own odd choices, but overdoses of pet rocks and

low-rider pants are not fatal. Drugs are different, so the argument goes, because they are so

seductive and dangerous. Drug-induced behavior can impair decision-making processes through

dependence or intoxicated reasoning; the "choice" to continue abusing drugs is something less

than completely free. Users may not fully understand the risks before initiating use. After all, the

great bulk of initiation is by adolescents and young adults, for whom immediate pleasures cloud

judgments involving probabilistic risks of adverse outcomes that are mostly in the future.

Precocious use is also a strong risk factor predicting subsequent dependence. Once users

become dependent, it can be psychologically and/or physically painful to abstain. Furthermore,

the minority of heavy users account for a disproportionate share of all drug consumption, which

means that a goodly share of all "decisions" to imbibe are made while judgment is impaired by

earlier doses.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

While drugs can harm users, so can other unhealthy consumer goods or high-risk activities. Yet

few laws forbid eating artery-clogging foods, competing in mixed martial arts, or bungee jumping.

Though two states, Michigan and Florida, have introduced temporary bans on bungee jumping,

and others highly regulate the activity. What makes drugs-legal and illegal-different from those

examples though, is their capacity to harm nonusers, including people completely uninvolved in

the market. Nonusers suffer when passersby breathe secondhand smoke, when drug use during

pregnancy causes congenital defects in newborns, or when impaired drivers smash their cars

into other cars, pedestrians, or property. More diffuse damage arises when drug use reduces

worker productivity orcreates healthcare costs others in the same insurance pool must bear.

Such "externalities" make otherwise private consumption decisions a matter of public concern.

However, these facts merely argue for drug policies that are distinct from, and perhaps more

assertive than, polices toward consumer goods generally. It does not imply that the policy must

be to ban all non-medical use. Still, given the problems that drug use creates, prohibition has

obvious appeal.

Difficult policy choices

Public policies often create unintended side effects or consequences. Abolishing the legal market

for drugs may reduce drug use, but it doesn't eradicate all use, and the residual consumption

sustains black markets that generate other social problems including crime, violence, and

corruption. Enforcement of prohibition can cause still other problems. The US incarcerates about

500,000 people for drug-law violations at any given time, a number higher than the total prison

population in any country save China and Russia. That burden falls disproportionately on

minorities and the poor. Human Rights Watch, among other groups, sharply criticizes the U.S. on

this point, noting that black adults are sentenced to state prisons for drug offenses at ten times

the corresponding rate for white adults (1).

Formulating drug policy is not easy. Enormous social costs, including incarceration, follow from

abuse of both illegal and legal drugs, so neither legalization nor prohibition is a panacea. In

addition, new psychoactive chemicals are appearing with a frequency that tests the capacity of

the current framework for "scheduling" substances. Given the complexities of the social problem

of drug use and the various interests at stake, it should come as no surprise that the policy

outcomes leave some people dissatisfied.

Prohibitions are not unchangeable. In 1930, the US prohibited alcohol, but not marijuana. Ten

years later the positions were reversed. Changing a drug's legal status, either legalizing

a drug that is now prohibited or prohibiting one that is now legal, such as tobacco, will not

eliminate all problems; underground markets produce one set of problems, legal markets

another. Changing the legal status of a drug is no silver bullet; it's more "trading the devil you

know for the devil you don't know."

Nevertheless, thinking hard about prohibition and legalization is valuable for three reasons: the

devil you don't know might not be as bad, the exercise can inspire ideas for improving the current

legal regime, and, as a practical matter, policy changes are happening regardless of whether or

not one wants them.

Some jurisdictions are tightening regulations on legal drugs. Atlanta's recent ban on smoking in

public parks is backed by fines of up

to 1,000andsentencesofuptosixmonthsinjail(2).Virginia

′spenaltiesforfirst−timeDWIoffensesalreadyincludedfinesofupto2,500 and

jail sentences of up to a year, but as of July 1st, 2012 those with restricted licenses were also

required to install an ignition interlock system (a breathalyzer-like tool that prevents a car engine

from starting if BAC is over a certain level) (3).

Other jurisdictions are relaxing laws pertaining to marijuana. US states started decriminalizing

marijuana in the 1970s and more are considering it now. California already treated possession of

few laws forbid eating artery-clogging foods, competing in mixed martial arts, or bungee jumping.

Though two states, Michigan and Florida, have introduced temporary bans on bungee jumping,

and others highly regulate the activity. What makes drugs-legal and illegal-different from those

examples though, is their capacity to harm nonusers, including people completely uninvolved in

the market. Nonusers suffer when passersby breathe secondhand smoke, when drug use during

pregnancy causes congenital defects in newborns, or when impaired drivers smash their cars

into other cars, pedestrians, or property. More diffuse damage arises when drug use reduces

worker productivity orcreates healthcare costs others in the same insurance pool must bear.

Such "externalities" make otherwise private consumption decisions a matter of public concern.

However, these facts merely argue for drug policies that are distinct from, and perhaps more

assertive than, polices toward consumer goods generally. It does not imply that the policy must

be to ban all non-medical use. Still, given the problems that drug use creates, prohibition has

obvious appeal.

Difficult policy choices

Public policies often create unintended side effects or consequences. Abolishing the legal market

for drugs may reduce drug use, but it doesn't eradicate all use, and the residual consumption

sustains black markets that generate other social problems including crime, violence, and

corruption. Enforcement of prohibition can cause still other problems. The US incarcerates about

500,000 people for drug-law violations at any given time, a number higher than the total prison

population in any country save China and Russia. That burden falls disproportionately on

minorities and the poor. Human Rights Watch, among other groups, sharply criticizes the U.S. on

this point, noting that black adults are sentenced to state prisons for drug offenses at ten times

the corresponding rate for white adults (1).

Formulating drug policy is not easy. Enormous social costs, including incarceration, follow from

abuse of both illegal and legal drugs, so neither legalization nor prohibition is a panacea. In

addition, new psychoactive chemicals are appearing with a frequency that tests the capacity of

the current framework for "scheduling" substances. Given the complexities of the social problem

of drug use and the various interests at stake, it should come as no surprise that the policy

outcomes leave some people dissatisfied.

Prohibitions are not unchangeable. In 1930, the US prohibited alcohol, but not marijuana. Ten

years later the positions were reversed. Changing a drug's legal status, either legalizing

a drug that is now prohibited or prohibiting one that is now legal, such as tobacco, will not

eliminate all problems; underground markets produce one set of problems, legal markets

another. Changing the legal status of a drug is no silver bullet; it's more "trading the devil you

know for the devil you don't know."

Nevertheless, thinking hard about prohibition and legalization is valuable for three reasons: the

devil you don't know might not be as bad, the exercise can inspire ideas for improving the current

legal regime, and, as a practical matter, policy changes are happening regardless of whether or

not one wants them.

Some jurisdictions are tightening regulations on legal drugs. Atlanta's recent ban on smoking in

public parks is backed by fines of up

to 1,000andsentencesofuptosixmonthsinjail(2).Virginia

′spenaltiesforfirst−timeDWIoffensesalreadyincludedfinesofupto2,500 and

jail sentences of up to a year, but as of July 1st, 2012 those with restricted licenses were also

required to install an ignition interlock system (a breathalyzer-like tool that prevents a car engine

from starting if BAC is over a certain level) (3).

Other jurisdictions are relaxing laws pertaining to marijuana. US states started decriminalizing

marijuana in the 1970s and more are considering it now. California already treated possession of

less than one ounce of marijuana as only a "citable" misdemeanor (typically leading to the

equivalent of a traffic ticket) before California SB 1449 went into effect in January 2011, which

downgraded the offense to a mere infraction. Seventeen states and the District of Columbia have

implemented medical marijuana programs, and six more are actively considering it. In November

2012, Colorado and Washington voted for full legalization, including commercial production and

sale for non-medical use.

Other countries are also considering liberalization. Uruguay's President José Mujica recently

proposed that the government supply marijuana to registered users. Current and former leaders

of a number of countries, particularly in South and Central America, want open discussion about

legalizing "hard" drugs like cocaine and heroin.

Legalizing marijuana and legalizing hard drugs are very different choices, with significantly

different stakes and likely outcomes. Marijuana is special for at least four reasons. First,

marijuana markets are associated with much less violence, and (since marijuana rarely

dominates the budgets of its users) its consumption is much less associated with income-

generating crime. Second, regardless of the merits of the matter, there is essentially no prospect

of the US legalizing cocaine/crack, heroin, or methamphetamine in the near or even medium-

term future. Such proposals would have almost no public support. In contrast, marijuana

prohibition is under active attack now. Third, 17 million Americans use marijuana in any given

month, a figure that far exceeds use of all other illegal drugscombined (except diverted

pharmaceuticals). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, marijuana use is simply much less

dangerous, in terms of risk of overdose, risk of disastrous intoxicated behavior, and risk of

dependence coming to dominate one's life.

Unfortunately, much of the literature on legalization comes from advocates and opponents of

legal change, in each case more committed to their cause than to objectivity. The following two

sections attempt to give a more balanced overview of the merits, detriments and important

considerations of first, prohibition, and second, legalization. (Space limitations necessitate an

abbreviated discussion. MacCoun and Reuter (4) remains the single best book

on legalization and we highly recommend it to those interested in further reading). The

subsequent sections ask whether "middle path" options exist that could cherry-pick the best

attributes of the two extremes.

This chapter does not advocate one position or another. Our aim is not to sway readers, but to

immunize them against naïve susceptibility to hyperbolic statements that both prohibitionists

and legalization advocates sometimes make.

Current policy: Prohibition

Prohibition constrains the number of users and the quantity they consum in four ways. First,

prohibition probably reduces demand, on net. While there can be so-called "forbidden fruits"

effects, meaning that the very act of prohibiting something can increase its allure, those are

counter-balanced by factors that discourage the consumption of prohibited substances: the black

market's poor production quality control, minimal labeling information, and social disapprobation,

not to mention the risk of arrest and other sanctions, such as loss of scholarships or opportunities

to compete in interscholastic athletics (5,6). (Both the uncertain quality in illicit drugs - uncertainty

about the amount and identity of the active agents, and the risk of dangerous impurities - and

user penalties tend to increase the harm-per-use of those drugs, compared to what it would be

under legal availability, just as they suppress the quantity consumed. The net effect on overall

health and other damage to users is uncertain.)

Second, prohibition reduces availability. While the Monitoring the Future survey famously finds

that the proportion of high school students reporting that marijuana is fairly or very easy to obtain

(82%) is nearly as high as the corresponding proportion for alcohol (89%), marijuana is the

exception. Those same surveys find much lower rates of availability for cocaine (31%), MDMA

equivalent of a traffic ticket) before California SB 1449 went into effect in January 2011, which

downgraded the offense to a mere infraction. Seventeen states and the District of Columbia have

implemented medical marijuana programs, and six more are actively considering it. In November

2012, Colorado and Washington voted for full legalization, including commercial production and

sale for non-medical use.

Other countries are also considering liberalization. Uruguay's President José Mujica recently

proposed that the government supply marijuana to registered users. Current and former leaders

of a number of countries, particularly in South and Central America, want open discussion about

legalizing "hard" drugs like cocaine and heroin.

Legalizing marijuana and legalizing hard drugs are very different choices, with significantly

different stakes and likely outcomes. Marijuana is special for at least four reasons. First,

marijuana markets are associated with much less violence, and (since marijuana rarely

dominates the budgets of its users) its consumption is much less associated with income-

generating crime. Second, regardless of the merits of the matter, there is essentially no prospect

of the US legalizing cocaine/crack, heroin, or methamphetamine in the near or even medium-

term future. Such proposals would have almost no public support. In contrast, marijuana

prohibition is under active attack now. Third, 17 million Americans use marijuana in any given

month, a figure that far exceeds use of all other illegal drugscombined (except diverted

pharmaceuticals). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, marijuana use is simply much less

dangerous, in terms of risk of overdose, risk of disastrous intoxicated behavior, and risk of

dependence coming to dominate one's life.

Unfortunately, much of the literature on legalization comes from advocates and opponents of

legal change, in each case more committed to their cause than to objectivity. The following two

sections attempt to give a more balanced overview of the merits, detriments and important

considerations of first, prohibition, and second, legalization. (Space limitations necessitate an

abbreviated discussion. MacCoun and Reuter (4) remains the single best book

on legalization and we highly recommend it to those interested in further reading). The

subsequent sections ask whether "middle path" options exist that could cherry-pick the best

attributes of the two extremes.

This chapter does not advocate one position or another. Our aim is not to sway readers, but to

immunize them against naïve susceptibility to hyperbolic statements that both prohibitionists

and legalization advocates sometimes make.

Current policy: Prohibition

Prohibition constrains the number of users and the quantity they consum in four ways. First,

prohibition probably reduces demand, on net. While there can be so-called "forbidden fruits"

effects, meaning that the very act of prohibiting something can increase its allure, those are

counter-balanced by factors that discourage the consumption of prohibited substances: the black

market's poor production quality control, minimal labeling information, and social disapprobation,

not to mention the risk of arrest and other sanctions, such as loss of scholarships or opportunities

to compete in interscholastic athletics (5,6). (Both the uncertain quality in illicit drugs - uncertainty

about the amount and identity of the active agents, and the risk of dangerous impurities - and

user penalties tend to increase the harm-per-use of those drugs, compared to what it would be

under legal availability, just as they suppress the quantity consumed. The net effect on overall

health and other damage to users is uncertain.)

Second, prohibition reduces availability. While the Monitoring the Future survey famously finds

that the proportion of high school students reporting that marijuana is fairly or very easy to obtain

(82%) is nearly as high as the corresponding proportion for alcohol (89%), marijuana is the

exception. Those same surveys find much lower rates of availability for cocaine (31%), MDMA

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

(37%), and heroin (21%) (7). Indeed, even long-term daily heroin users often report search times

approaching an hour in order to "score" their preferred drug (8).

Third, prohibition backed by even modest enforcement raises production costs by imposing what

Peter Reuter has called "the structural consequences of product illegality": a legal ban forces

suppliers to operate covertly, which creates inefficiencies. Black market producers cannot invest

in bulky machinery that would be hard to hide and easy for police to confiscate.

As a result, crack dealers' staff can package crack vials at a rate of about 100 per hour; by

contrast, sugar-packaging machines fill the sugar packets offered in restaurants at a rate of

about 1,000 per minute (9). Likewise, drug dealers cannot resolve business disputes in courts,

and while lawyers are expensive, resolving disagreements with knives and guns is even more

costly.

Fourth, drug dealers must pay extra to compensate employees for incurring the considerable

risks of experiencing arrest or violence, what economists call "compensating wage differentials"

(10). Retail drug dealers make a lot of money (when they do) notas a reward for unusual skill but

as compensation for the risks they incur.

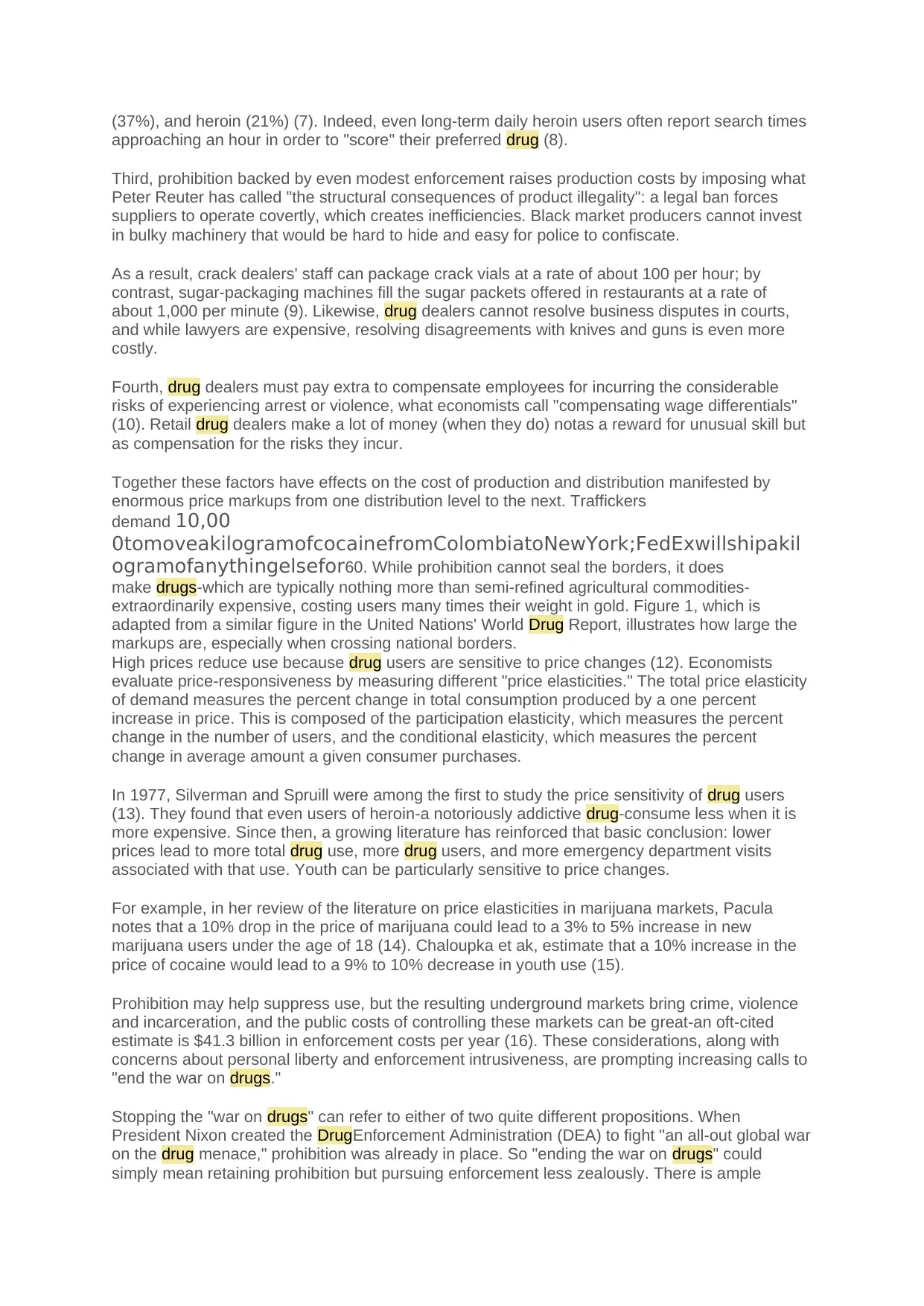

Together these factors have effects on the cost of production and distribution manifested by

enormous price markups from one distribution level to the next. Traffickers

demand 10,00

0tomoveakilogramofcocainefromColombiatoNewYork;FedExwillshipakil

ogramofanythingelsefor60. While prohibition cannot seal the borders, it does

make drugs-which are typically nothing more than semi-refined agricultural commodities-

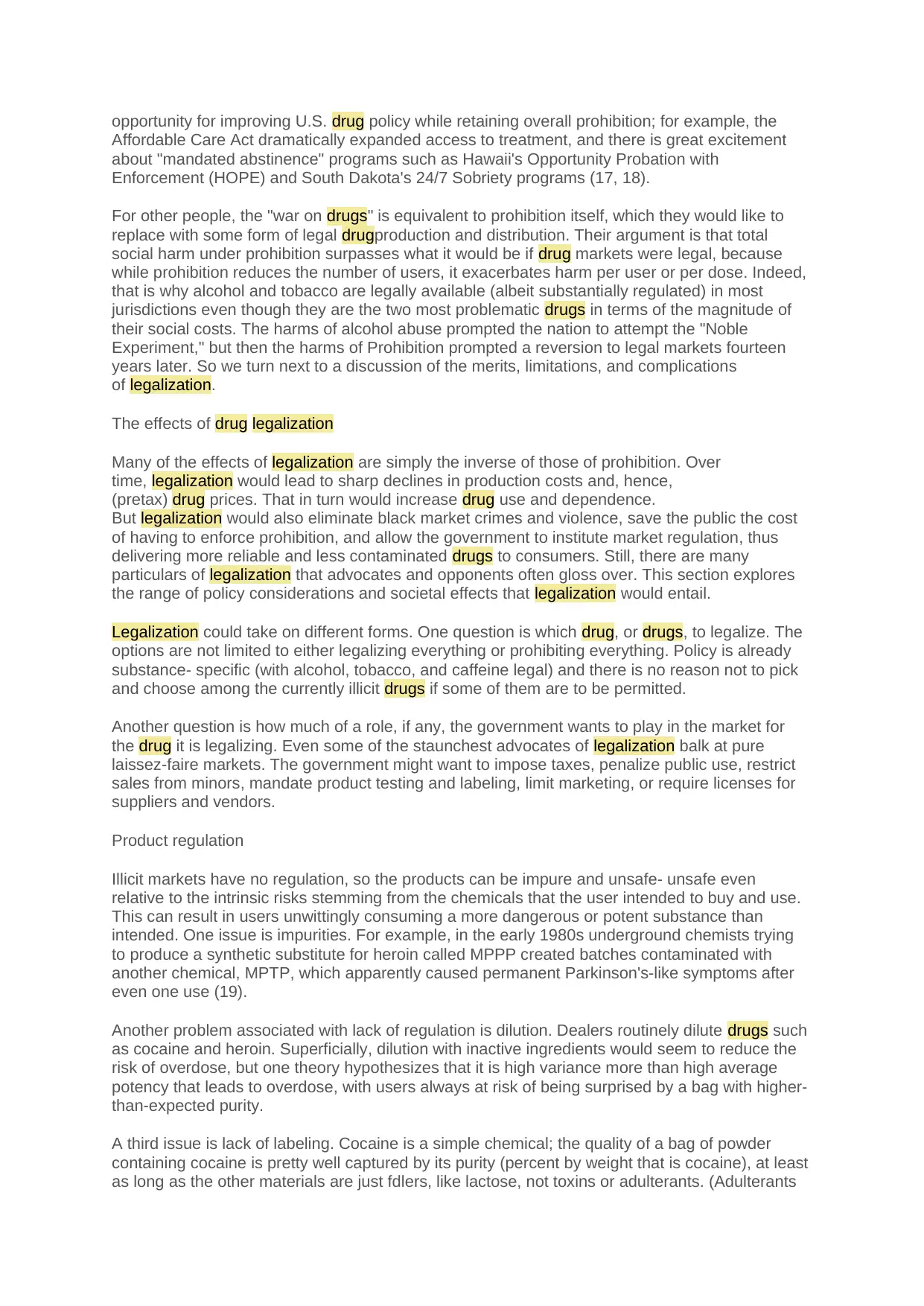

extraordinarily expensive, costing users many times their weight in gold. Figure 1, which is

adapted from a similar figure in the United Nations' World Drug Report, illustrates how large the

markups are, especially when crossing national borders.

High prices reduce use because drug users are sensitive to price changes (12). Economists

evaluate price-responsiveness by measuring different "price elasticities." The total price elasticity

of demand measures the percent change in total consumption produced by a one percent

increase in price. This is composed of the participation elasticity, which measures the percent

change in the number of users, and the conditional elasticity, which measures the percent

change in average amount a given consumer purchases.

In 1977, Silverman and Spruill were among the first to study the price sensitivity of drug users

(13). They found that even users of heroin-a notoriously addictive drug-consume less when it is

more expensive. Since then, a growing literature has reinforced that basic conclusion: lower

prices lead to more total drug use, more drug users, and more emergency department visits

associated with that use. Youth can be particularly sensitive to price changes.

For example, in her review of the literature on price elasticities in marijuana markets, Pacula

notes that a 10% drop in the price of marijuana could lead to a 3% to 5% increase in new

marijuana users under the age of 18 (14). Chaloupka et ak, estimate that a 10% increase in the

price of cocaine would lead to a 9% to 10% decrease in youth use (15).

Prohibition may help suppress use, but the resulting underground markets bring crime, violence

and incarceration, and the public costs of controlling these markets can be great-an oft-cited

estimate is $41.3 billion in enforcement costs per year (16). These considerations, along with

concerns about personal liberty and enforcement intrusiveness, are prompting increasing calls to

"end the war on drugs."

Stopping the "war on drugs" can refer to either of two quite different propositions. When

President Nixon created the DrugEnforcement Administration (DEA) to fight "an all-out global war

on the drug menace," prohibition was already in place. So "ending the war on drugs" could

simply mean retaining prohibition but pursuing enforcement less zealously. There is ample

approaching an hour in order to "score" their preferred drug (8).

Third, prohibition backed by even modest enforcement raises production costs by imposing what

Peter Reuter has called "the structural consequences of product illegality": a legal ban forces

suppliers to operate covertly, which creates inefficiencies. Black market producers cannot invest

in bulky machinery that would be hard to hide and easy for police to confiscate.

As a result, crack dealers' staff can package crack vials at a rate of about 100 per hour; by

contrast, sugar-packaging machines fill the sugar packets offered in restaurants at a rate of

about 1,000 per minute (9). Likewise, drug dealers cannot resolve business disputes in courts,

and while lawyers are expensive, resolving disagreements with knives and guns is even more

costly.

Fourth, drug dealers must pay extra to compensate employees for incurring the considerable

risks of experiencing arrest or violence, what economists call "compensating wage differentials"

(10). Retail drug dealers make a lot of money (when they do) notas a reward for unusual skill but

as compensation for the risks they incur.

Together these factors have effects on the cost of production and distribution manifested by

enormous price markups from one distribution level to the next. Traffickers

demand 10,00

0tomoveakilogramofcocainefromColombiatoNewYork;FedExwillshipakil

ogramofanythingelsefor60. While prohibition cannot seal the borders, it does

make drugs-which are typically nothing more than semi-refined agricultural commodities-

extraordinarily expensive, costing users many times their weight in gold. Figure 1, which is

adapted from a similar figure in the United Nations' World Drug Report, illustrates how large the

markups are, especially when crossing national borders.

High prices reduce use because drug users are sensitive to price changes (12). Economists

evaluate price-responsiveness by measuring different "price elasticities." The total price elasticity

of demand measures the percent change in total consumption produced by a one percent

increase in price. This is composed of the participation elasticity, which measures the percent

change in the number of users, and the conditional elasticity, which measures the percent

change in average amount a given consumer purchases.

In 1977, Silverman and Spruill were among the first to study the price sensitivity of drug users

(13). They found that even users of heroin-a notoriously addictive drug-consume less when it is

more expensive. Since then, a growing literature has reinforced that basic conclusion: lower

prices lead to more total drug use, more drug users, and more emergency department visits

associated with that use. Youth can be particularly sensitive to price changes.

For example, in her review of the literature on price elasticities in marijuana markets, Pacula

notes that a 10% drop in the price of marijuana could lead to a 3% to 5% increase in new

marijuana users under the age of 18 (14). Chaloupka et ak, estimate that a 10% increase in the

price of cocaine would lead to a 9% to 10% decrease in youth use (15).

Prohibition may help suppress use, but the resulting underground markets bring crime, violence

and incarceration, and the public costs of controlling these markets can be great-an oft-cited

estimate is $41.3 billion in enforcement costs per year (16). These considerations, along with

concerns about personal liberty and enforcement intrusiveness, are prompting increasing calls to

"end the war on drugs."

Stopping the "war on drugs" can refer to either of two quite different propositions. When

President Nixon created the DrugEnforcement Administration (DEA) to fight "an all-out global war

on the drug menace," prohibition was already in place. So "ending the war on drugs" could

simply mean retaining prohibition but pursuing enforcement less zealously. There is ample

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

opportunity for improving U.S. drug policy while retaining overall prohibition; for example, the

Affordable Care Act dramatically expanded access to treatment, and there is great excitement

about "mandated abstinence" programs such as Hawaii's Opportunity Probation with

Enforcement (HOPE) and South Dakota's 24/7 Sobriety programs (17, 18).

For other people, the "war on drugs" is equivalent to prohibition itself, which they would like to

replace with some form of legal drugproduction and distribution. Their argument is that total

social harm under prohibition surpasses what it would be if drug markets were legal, because

while prohibition reduces the number of users, it exacerbates harm per user or per dose. Indeed,

that is why alcohol and tobacco are legally available (albeit substantially regulated) in most

jurisdictions even though they are the two most problematic drugs in terms of the magnitude of

their social costs. The harms of alcohol abuse prompted the nation to attempt the "Noble

Experiment," but then the harms of Prohibition prompted a reversion to legal markets fourteen

years later. So we turn next to a discussion of the merits, limitations, and complications

of legalization.

The effects of drug legalization

Many of the effects of legalization are simply the inverse of those of prohibition. Over

time, legalization would lead to sharp declines in production costs and, hence,

(pretax) drug prices. That in turn would increase drug use and dependence.

But legalization would also eliminate black market crimes and violence, save the public the cost

of having to enforce prohibition, and allow the government to institute market regulation, thus

delivering more reliable and less contaminated drugs to consumers. Still, there are many

particulars of legalization that advocates and opponents often gloss over. This section explores

the range of policy considerations and societal effects that legalization would entail.

Legalization could take on different forms. One question is which drug, or drugs, to legalize. The

options are not limited to either legalizing everything or prohibiting everything. Policy is already

substance- specific (with alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine legal) and there is no reason not to pick

and choose among the currently illicit drugs if some of them are to be permitted.

Another question is how much of a role, if any, the government wants to play in the market for

the drug it is legalizing. Even some of the staunchest advocates of legalization balk at pure

laissez-faire markets. The government might want to impose taxes, penalize public use, restrict

sales from minors, mandate product testing and labeling, limit marketing, or require licenses for

suppliers and vendors.

Product regulation

Illicit markets have no regulation, so the products can be impure and unsafe- unsafe even

relative to the intrinsic risks stemming from the chemicals that the user intended to buy and use.

This can result in users unwittingly consuming a more dangerous or potent substance than

intended. One issue is impurities. For example, in the early 1980s underground chemists trying

to produce a synthetic substitute for heroin called MPPP created batches contaminated with

another chemical, MPTP, which apparently caused permanent Parkinson's-like symptoms after

even one use (19).

Another problem associated with lack of regulation is dilution. Dealers routinely dilute drugs such

as cocaine and heroin. Superficially, dilution with inactive ingredients would seem to reduce the

risk of overdose, but one theory hypothesizes that it is high variance more than high average

potency that leads to overdose, with users always at risk of being surprised by a bag with higher-

than-expected purity.

A third issue is lack of labeling. Cocaine is a simple chemical; the quality of a bag of powder

containing cocaine is pretty well captured by its purity (percent by weight that is cocaine), at least

as long as the other materials are just fdlers, like lactose, not toxins or adulterants. (Adulterants

Affordable Care Act dramatically expanded access to treatment, and there is great excitement

about "mandated abstinence" programs such as Hawaii's Opportunity Probation with

Enforcement (HOPE) and South Dakota's 24/7 Sobriety programs (17, 18).

For other people, the "war on drugs" is equivalent to prohibition itself, which they would like to

replace with some form of legal drugproduction and distribution. Their argument is that total

social harm under prohibition surpasses what it would be if drug markets were legal, because

while prohibition reduces the number of users, it exacerbates harm per user or per dose. Indeed,

that is why alcohol and tobacco are legally available (albeit substantially regulated) in most

jurisdictions even though they are the two most problematic drugs in terms of the magnitude of

their social costs. The harms of alcohol abuse prompted the nation to attempt the "Noble

Experiment," but then the harms of Prohibition prompted a reversion to legal markets fourteen

years later. So we turn next to a discussion of the merits, limitations, and complications

of legalization.

The effects of drug legalization

Many of the effects of legalization are simply the inverse of those of prohibition. Over

time, legalization would lead to sharp declines in production costs and, hence,

(pretax) drug prices. That in turn would increase drug use and dependence.

But legalization would also eliminate black market crimes and violence, save the public the cost

of having to enforce prohibition, and allow the government to institute market regulation, thus

delivering more reliable and less contaminated drugs to consumers. Still, there are many

particulars of legalization that advocates and opponents often gloss over. This section explores

the range of policy considerations and societal effects that legalization would entail.

Legalization could take on different forms. One question is which drug, or drugs, to legalize. The

options are not limited to either legalizing everything or prohibiting everything. Policy is already

substance- specific (with alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine legal) and there is no reason not to pick

and choose among the currently illicit drugs if some of them are to be permitted.

Another question is how much of a role, if any, the government wants to play in the market for

the drug it is legalizing. Even some of the staunchest advocates of legalization balk at pure

laissez-faire markets. The government might want to impose taxes, penalize public use, restrict

sales from minors, mandate product testing and labeling, limit marketing, or require licenses for

suppliers and vendors.

Product regulation

Illicit markets have no regulation, so the products can be impure and unsafe- unsafe even

relative to the intrinsic risks stemming from the chemicals that the user intended to buy and use.

This can result in users unwittingly consuming a more dangerous or potent substance than

intended. One issue is impurities. For example, in the early 1980s underground chemists trying

to produce a synthetic substitute for heroin called MPPP created batches contaminated with

another chemical, MPTP, which apparently caused permanent Parkinson's-like symptoms after

even one use (19).

Another problem associated with lack of regulation is dilution. Dealers routinely dilute drugs such

as cocaine and heroin. Superficially, dilution with inactive ingredients would seem to reduce the

risk of overdose, but one theory hypothesizes that it is high variance more than high average

potency that leads to overdose, with users always at risk of being surprised by a bag with higher-

than-expected purity.

A third issue is lack of labeling. Cocaine is a simple chemical; the quality of a bag of powder

containing cocaine is pretty well captured by its purity (percent by weight that is cocaine), at least

as long as the other materials are just fdlers, like lactose, not toxins or adulterants. (Adulterants

are other psychoactives; diluents just add bulk) (see chapter 10). Cannabis is different.

Depending on the plant, a gram of high-grade marijuana could contain over 20% THC, while the

same weight of low-grade would contain less than 5%. Also, while THC potency was once

thought of as a sufficient statistic for the quality of marijuana, marijuana plants contain many

other psychoactive chemicals, and it is increasingly recognized that other cannabinoids matter.

Some believe that cannabidiol (CBD) helps relieve anxiety created by THC (20), so that high

ratios of THC to CBD, not just high THC potency, might trigger adverse reactions. A few

dispensaries operating under state medical-marijuana laws report both the THC and CBD

content of their products (21); this is almost unheard of among black-market dealers.

Illegality also creates harm associated with certain methods of drug administration. Injecting

heroin is more cost-efficient than "chasing the dragon" (smoking), in the sense that a larger

proportion of the (expensive) heroin ends up in the user's bloodstream. However, users who

share needles risk transmitting blood-borne diseases like HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C. If legalized,

heroin would be cheaper, thereby reducing the incentive for intravenous use.

Advocates of legalization suggest it could bring other beneficial shifts in mode of administration.

For example, marijuana vaporization may be less toxic than smoking a joint; if marijuana were

legalized, regulations could be put in place to encourage vaporization and discourage smoking.

Availability to youth

Most proposals to legalize drugs would continue to ban use by youth, just as alcohol is only legal

in the US for those over the age of 21 years. This distinction is important because adolescents'

brains are still developing, minors are not generally trusted to consistently make choices that are

in their long-run interests, and quite simply, most drug use starts when people are young. If an

individual has not initiated use of a drug by around their mid-twenties, there is strong likelihood

the person will never use it. (So, if a 50- year-old proclaims, "Legalization wouldn't

affect drug use. It's not as if it'd make me go out and start using!" one should ask, "Yes, but the

real question is, would you have been more likely to use the substance when you were 18 if it

had been legal then?")

However, it is hard to prevent 20-year-olds from getting access to what their 21-year-old friends

can buy legally. It is instructive to look at perceptions of availability and risk for different

substances, legal and illegal, and how those vary with age. Such comparisons are not

dispositive, since correlations do not imply causality, but without data from experimental trials

that vary the legal status of drugs, cross-sectional data may be better than none.

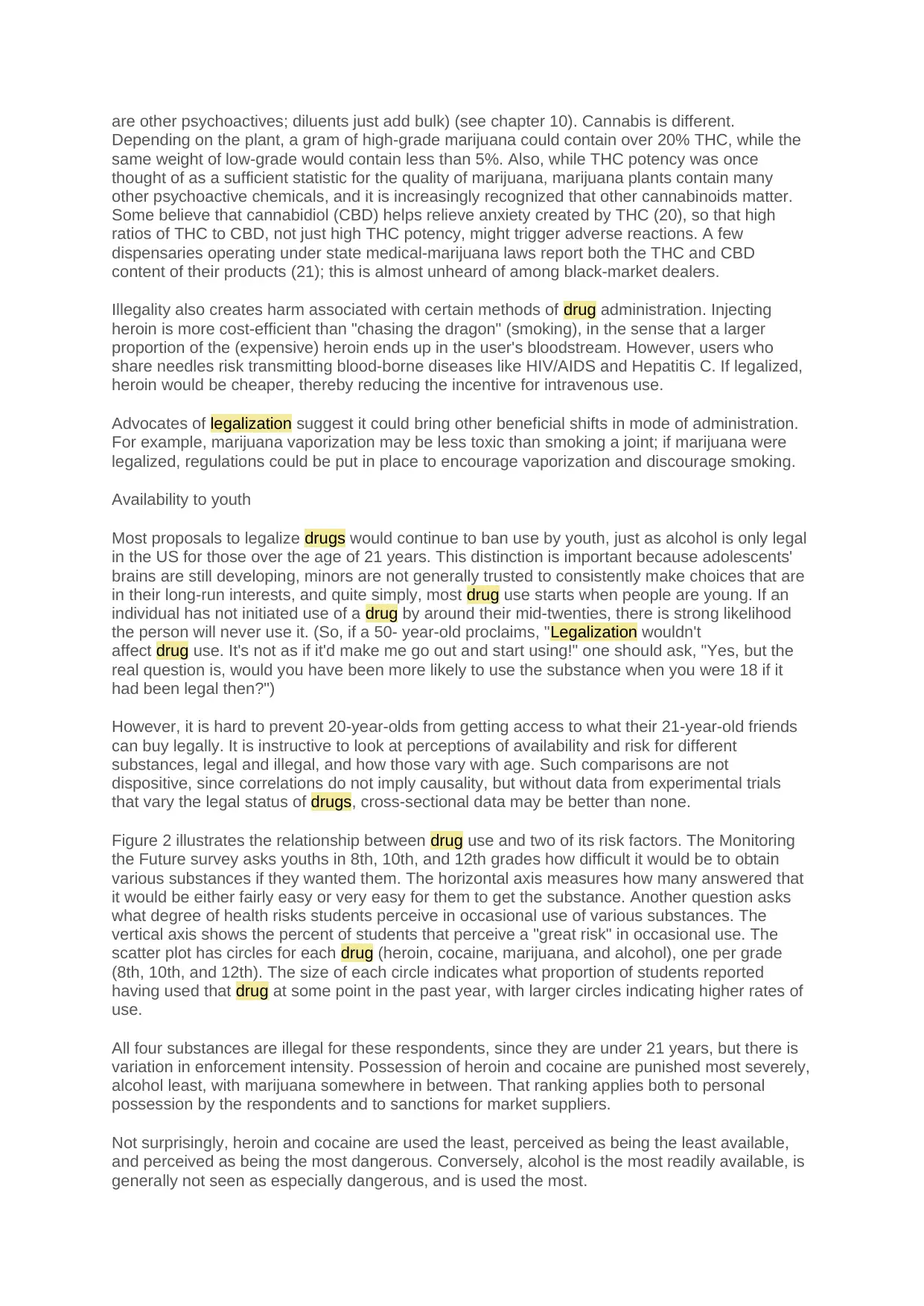

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between drug use and two of its risk factors. The Monitoring

the Future survey asks youths in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades how difficult it would be to obtain

various substances if they wanted them. The horizontal axis measures how many answered that

it would be either fairly easy or very easy for them to get the substance. Another question asks

what degree of health risks students perceive in occasional use of various substances. The

vertical axis shows the percent of students that perceive a "great risk" in occasional use. The

scatter plot has circles for each drug (heroin, cocaine, marijuana, and alcohol), one per grade

(8th, 10th, and 12th). The size of each circle indicates what proportion of students reported

having used that drug at some point in the past year, with larger circles indicating higher rates of

use.

All four substances are illegal for these respondents, since they are under 21 years, but there is

variation in enforcement intensity. Possession of heroin and cocaine are punished most severely,

alcohol least, with marijuana somewhere in between. That ranking applies both to personal

possession by the respondents and to sanctions for market suppliers.

Not surprisingly, heroin and cocaine are used the least, perceived as being the least available,

and perceived as being the most dangerous. Conversely, alcohol is the most readily available, is

generally not seen as especially dangerous, and is used the most.

Depending on the plant, a gram of high-grade marijuana could contain over 20% THC, while the

same weight of low-grade would contain less than 5%. Also, while THC potency was once

thought of as a sufficient statistic for the quality of marijuana, marijuana plants contain many

other psychoactive chemicals, and it is increasingly recognized that other cannabinoids matter.

Some believe that cannabidiol (CBD) helps relieve anxiety created by THC (20), so that high

ratios of THC to CBD, not just high THC potency, might trigger adverse reactions. A few

dispensaries operating under state medical-marijuana laws report both the THC and CBD

content of their products (21); this is almost unheard of among black-market dealers.

Illegality also creates harm associated with certain methods of drug administration. Injecting

heroin is more cost-efficient than "chasing the dragon" (smoking), in the sense that a larger

proportion of the (expensive) heroin ends up in the user's bloodstream. However, users who

share needles risk transmitting blood-borne diseases like HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C. If legalized,

heroin would be cheaper, thereby reducing the incentive for intravenous use.

Advocates of legalization suggest it could bring other beneficial shifts in mode of administration.

For example, marijuana vaporization may be less toxic than smoking a joint; if marijuana were

legalized, regulations could be put in place to encourage vaporization and discourage smoking.

Availability to youth

Most proposals to legalize drugs would continue to ban use by youth, just as alcohol is only legal

in the US for those over the age of 21 years. This distinction is important because adolescents'

brains are still developing, minors are not generally trusted to consistently make choices that are

in their long-run interests, and quite simply, most drug use starts when people are young. If an

individual has not initiated use of a drug by around their mid-twenties, there is strong likelihood

the person will never use it. (So, if a 50- year-old proclaims, "Legalization wouldn't

affect drug use. It's not as if it'd make me go out and start using!" one should ask, "Yes, but the

real question is, would you have been more likely to use the substance when you were 18 if it

had been legal then?")

However, it is hard to prevent 20-year-olds from getting access to what their 21-year-old friends

can buy legally. It is instructive to look at perceptions of availability and risk for different

substances, legal and illegal, and how those vary with age. Such comparisons are not

dispositive, since correlations do not imply causality, but without data from experimental trials

that vary the legal status of drugs, cross-sectional data may be better than none.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between drug use and two of its risk factors. The Monitoring

the Future survey asks youths in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades how difficult it would be to obtain

various substances if they wanted them. The horizontal axis measures how many answered that

it would be either fairly easy or very easy for them to get the substance. Another question asks

what degree of health risks students perceive in occasional use of various substances. The

vertical axis shows the percent of students that perceive a "great risk" in occasional use. The

scatter plot has circles for each drug (heroin, cocaine, marijuana, and alcohol), one per grade

(8th, 10th, and 12th). The size of each circle indicates what proportion of students reported

having used that drug at some point in the past year, with larger circles indicating higher rates of

use.

All four substances are illegal for these respondents, since they are under 21 years, but there is

variation in enforcement intensity. Possession of heroin and cocaine are punished most severely,

alcohol least, with marijuana somewhere in between. That ranking applies both to personal

possession by the respondents and to sanctions for market suppliers.

Not surprisingly, heroin and cocaine are used the least, perceived as being the least available,

and perceived as being the most dangerous. Conversely, alcohol is the most readily available, is

generally not seen as especially dangerous, and is used the most.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

For 8th graders marijuana is intermediate between heroin and cocaine on the one hand, and

alcohol on the other. For 10th and 12th graders, marijuana's circles almost coincide with the

circles for alcohol, being just slightly to the left (indicating slightly lower availability).

The monetary and human costs of enforcement

Legalization would save taxpayers money by reducing both the number of criminals put in prison

or jail and the time officers spend enforcing prohibition. ("Reducing," not "eliminating," because

many legalization proposals would retain prohibition for those under the age of 21 years).

Marijuana accounts for fully half of all drug arrests, so prorating total enforcement costs in

proportion to marijuana arrests would make marijuana legalization appear to be a big money

saver. However, a more careful analysis would recognize the lower rates of prosecution and

incarceration for marijuana arrests; this means that, even in a state the size of California, the cost

of enforcing marijuana prohibition on adults is probably below $200 million (22). The big savings

in law enforcement costs would come from legalizing cocaine/crack, heroin, and

methamphetamine.

Legalization would entail some regulatory enforcement costs, probably rising with the stringency

of the regulations. However, the costs for alcohol and tobacco regulation today are quite minor

compared with what is now spent trying to control illegal drugs. It is surprisingly difficult to provide

a precise figure for drug control spending. Even the federal drug control budget, which is

reported annually, is tricky to interpret, but the bigger challenge is that state and local

governments account for the majority of drug control spending, and they do not follow on any

common reporting system. It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that the costs of regulating

legalized drugs would be significantly less than the current costs of enforcing prohibition.

There is also a human cost to mass incarceration. The 500,000 person-years spent behind bars

for drug- law violations each year (23) is on a par with the number of life-years lost due to

premature death caused by street drugs, or roughly 10-15,000 deaths per year times 30-50 life-

years lost per death. (The equation would not hold if premature deaths from

prescription drugs were included, but controlling diversion of pharmaceuticals is also not

responsible for much imprisonment). Indeed, the scale of incarceration in the US and of

community-based sanctions, such as probation and parole, is so large as to be anti-democratic.

Significant numbers of well- defined subpopulations are disenfranchised (have lost voting rights)

as a result of felony convictions (24), with drug-law enforcement contributing substantially to the

overall effect.

State-level us. nationwide legalization

When discussing the effects of legalization, it is also important to distinguish

state legalization from national legalization. One state legalizing is very different from the nation

legalizing, because even if a state were to attempt to end prohibition, federal law would remain in

effect.

That does not mean state-level legalization is irrelevant. State and local enforcement agencies

are responsible for 97% of marijuana arrests (25). Removing those arrests would greatly reduce

the risks of punishment faced by dealers as well as users, unless the federal government

dramatically expanded its focus and stepped up its efforts. (Traditionally, federal prosecutors

focus on cases involving a few hundred pounds of marijuana or more, unless there are special

circumstances). Even if federal enforcement does not change, federal prohibition alone would

prevent marijuana production and distribution from getting too brazen. Kilmer et al. speculate that

unobtrusive grow houses might be able to operate below federal enforcement radar (26), but

completely outdoor farming or even large-scale greenhouse production might provide targets too

easy to detect and too tempting to seize for federal enforcement agencies to ignore.

While many advocates of legalization favor regulating rather than banning drug sales, the

ongoing federal ban might stymie certain regulatory structures. For example, permitting sales in

alcohol on the other. For 10th and 12th graders, marijuana's circles almost coincide with the

circles for alcohol, being just slightly to the left (indicating slightly lower availability).

The monetary and human costs of enforcement

Legalization would save taxpayers money by reducing both the number of criminals put in prison

or jail and the time officers spend enforcing prohibition. ("Reducing," not "eliminating," because

many legalization proposals would retain prohibition for those under the age of 21 years).

Marijuana accounts for fully half of all drug arrests, so prorating total enforcement costs in

proportion to marijuana arrests would make marijuana legalization appear to be a big money

saver. However, a more careful analysis would recognize the lower rates of prosecution and

incarceration for marijuana arrests; this means that, even in a state the size of California, the cost

of enforcing marijuana prohibition on adults is probably below $200 million (22). The big savings

in law enforcement costs would come from legalizing cocaine/crack, heroin, and

methamphetamine.

Legalization would entail some regulatory enforcement costs, probably rising with the stringency

of the regulations. However, the costs for alcohol and tobacco regulation today are quite minor

compared with what is now spent trying to control illegal drugs. It is surprisingly difficult to provide

a precise figure for drug control spending. Even the federal drug control budget, which is

reported annually, is tricky to interpret, but the bigger challenge is that state and local

governments account for the majority of drug control spending, and they do not follow on any

common reporting system. It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that the costs of regulating

legalized drugs would be significantly less than the current costs of enforcing prohibition.

There is also a human cost to mass incarceration. The 500,000 person-years spent behind bars

for drug- law violations each year (23) is on a par with the number of life-years lost due to

premature death caused by street drugs, or roughly 10-15,000 deaths per year times 30-50 life-

years lost per death. (The equation would not hold if premature deaths from

prescription drugs were included, but controlling diversion of pharmaceuticals is also not

responsible for much imprisonment). Indeed, the scale of incarceration in the US and of

community-based sanctions, such as probation and parole, is so large as to be anti-democratic.

Significant numbers of well- defined subpopulations are disenfranchised (have lost voting rights)

as a result of felony convictions (24), with drug-law enforcement contributing substantially to the

overall effect.

State-level us. nationwide legalization

When discussing the effects of legalization, it is also important to distinguish

state legalization from national legalization. One state legalizing is very different from the nation

legalizing, because even if a state were to attempt to end prohibition, federal law would remain in

effect.

That does not mean state-level legalization is irrelevant. State and local enforcement agencies

are responsible for 97% of marijuana arrests (25). Removing those arrests would greatly reduce

the risks of punishment faced by dealers as well as users, unless the federal government

dramatically expanded its focus and stepped up its efforts. (Traditionally, federal prosecutors

focus on cases involving a few hundred pounds of marijuana or more, unless there are special

circumstances). Even if federal enforcement does not change, federal prohibition alone would

prevent marijuana production and distribution from getting too brazen. Kilmer et al. speculate that

unobtrusive grow houses might be able to operate below federal enforcement radar (26), but

completely outdoor farming or even large-scale greenhouse production might provide targets too

easy to detect and too tempting to seize for federal enforcement agencies to ignore.

While many advocates of legalization favor regulating rather than banning drug sales, the

ongoing federal ban might stymie certain regulatory structures. For example, permitting sales in

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

state-run stores only (analogous to state liquor stores) might be impossible because the

operation of state stores would be judged to positively conflict with the federal Controlled

Substances Act.

Yet there is nothing to stop a state from simply repealing its laws against drugs, as the State of

New York did in 1923 when it repealed its laws against alcohol prohibition, a full decade before

federal repeal.

Middle paths and alternative approaches

Thinking about prohibition versus legalization as a binary choice is useful because a fairly sharp

line can be drawn based on whether or not it is legal to produce and distribute a substance for

non-medical use. However, seeing policy choices as existing somewhere along a continuum can

also be useful (27). From that perspective, there are many options in the territory between the

extremes of (A) aggressively enforcing full prohibition, and (B) legalizing all drugs without any

rules or regulations beyond what would apply to any other article of commerce.

Decriminalization

Decriminalization and legalization are not synonyms (28). Decriminalization retains criminal

sanctions on production and sale, but replaces criminal penalties for the possession of drugs in

small amounts with civil penalties. Several US states have decriminalized marijuana, beginning

in the 1970s.Other countries have done the same, and some extend decriminalize- tion to

other drugs as well. Colombia's Constitutional Court recently voted to decriminalize small

amounts of marijuana and cocaine, Portugal decriminalized possession of all drugs in 2001, and

Brazil's legislature is revising the penal code to possibly include the decriminalization of small

amounts of narcotics (29).

The majority of academics judge the empirical evidence as suggesting that decriminalization has

only very modest effects on prices and use (30). That non- effect is good news for drug reformers

in final-market countries, but decriminalization in those countries will do nothing to alleviate the

burden those markets create on source and transshipment countries, where the (sometimes

violent) trade would be undiminished and remain wholly illegal.

A kinder, gentler prohibition

Some negative effects of prohibition are not really the consequence of prohibition per se, but

rather of how prohibition is implemented. Legalization may not be necessary to address those

concerns. For example, opponents of current drug policy are right to criticize the disproportionate

share of punishment that poor and minority communities face, but reducing the overall intensity

of enforcement and shifting its focus rather than fully legalizing a drug could reduce the degree

and importance of that disparity. Still, as long as drugdealing is illegal, the activity will take place

in higher-crime neighborhoods, which tend to be predominantly minority. For this reason, a shift

in enforcement focus may only reduce the degree of this disparity, not eliminate it altogether, and

in any case those neighborhoods will also face disproportionate social costs from housing illicit

markets.

Mandatory minimum sentences are particularly decried, but the question of determinate

sentencing versus judicial discretion is orthogonal to the question of prohibition or legalization.

Some non-drug offenses carry mandatory minimum sentences too, notably gun law violations,

and there are many countries and even U.S. states that prohibit drugs without using mandatory

sentences.

Sometimes objections to mandatory minimum sentences are really objections to excessive

average sentence length, not to the removal of judicial discretion. Again, there is nothing intrinsic

to prohibition that requires long sentences. No one would accuse Ronald Reagan of having

operation of state stores would be judged to positively conflict with the federal Controlled

Substances Act.

Yet there is nothing to stop a state from simply repealing its laws against drugs, as the State of

New York did in 1923 when it repealed its laws against alcohol prohibition, a full decade before

federal repeal.

Middle paths and alternative approaches

Thinking about prohibition versus legalization as a binary choice is useful because a fairly sharp

line can be drawn based on whether or not it is legal to produce and distribute a substance for

non-medical use. However, seeing policy choices as existing somewhere along a continuum can

also be useful (27). From that perspective, there are many options in the territory between the

extremes of (A) aggressively enforcing full prohibition, and (B) legalizing all drugs without any

rules or regulations beyond what would apply to any other article of commerce.

Decriminalization

Decriminalization and legalization are not synonyms (28). Decriminalization retains criminal

sanctions on production and sale, but replaces criminal penalties for the possession of drugs in

small amounts with civil penalties. Several US states have decriminalized marijuana, beginning

in the 1970s.Other countries have done the same, and some extend decriminalize- tion to

other drugs as well. Colombia's Constitutional Court recently voted to decriminalize small

amounts of marijuana and cocaine, Portugal decriminalized possession of all drugs in 2001, and

Brazil's legislature is revising the penal code to possibly include the decriminalization of small

amounts of narcotics (29).

The majority of academics judge the empirical evidence as suggesting that decriminalization has

only very modest effects on prices and use (30). That non- effect is good news for drug reformers

in final-market countries, but decriminalization in those countries will do nothing to alleviate the

burden those markets create on source and transshipment countries, where the (sometimes

violent) trade would be undiminished and remain wholly illegal.

A kinder, gentler prohibition

Some negative effects of prohibition are not really the consequence of prohibition per se, but

rather of how prohibition is implemented. Legalization may not be necessary to address those

concerns. For example, opponents of current drug policy are right to criticize the disproportionate

share of punishment that poor and minority communities face, but reducing the overall intensity

of enforcement and shifting its focus rather than fully legalizing a drug could reduce the degree

and importance of that disparity. Still, as long as drugdealing is illegal, the activity will take place

in higher-crime neighborhoods, which tend to be predominantly minority. For this reason, a shift

in enforcement focus may only reduce the degree of this disparity, not eliminate it altogether, and

in any case those neighborhoods will also face disproportionate social costs from housing illicit

markets.

Mandatory minimum sentences are particularly decried, but the question of determinate

sentencing versus judicial discretion is orthogonal to the question of prohibition or legalization.

Some non-drug offenses carry mandatory minimum sentences too, notably gun law violations,

and there are many countries and even U.S. states that prohibit drugs without using mandatory

sentences.

Sometimes objections to mandatory minimum sentences are really objections to excessive

average sentence length, not to the removal of judicial discretion. Again, there is nothing intrinsic

to prohibition that requires long sentences. No one would accuse Ronald Reagan of having

legalized drugs, but when he was in office, there were only 10- 20% as many people

incarcerated for drug law violations as there are today (23).

Embracing harm reduction

For better and for worse, a principal goal of drug policy in the U.S. since the late nineteenth

century has been to discourage, or minimize, drug use. While the official rhetoric speaks of

"drug use and related consequences" the emphasis is on reducing use, and on reducing

consequences by reducing use. We can conceptualize drug harm via some very basic arithmetic:

(ProQuest: ... denotes formula omitted.)

While US policy has focused on ways to reduce use (both number of users and dosage per

user), other countries prioritize reducing the third term in the harm equation. Such so-called

"harm reduction" strategies focus on minimizing the consequences of drug use, and embrace

policies that reduce consequences even if they do not reduce use. MacCoun (31) offered an

insightful discussion of the distinction between "use reduction" and "harm reduction."

Favoring harm reduction in certain US policy circles is about as popular as was favoring

communism at the height of the McCarthy era, the phrase being seen as code for legalization or

implying that one tolerates vice. However, for many, harm reduction merely entails taking a

pragmatic public- health approach within an overall framework that continues to ban commercial

production and distribution.

Some harm reduction advocates believe that many dire consequences of our current prohibition

can be reversed without legalizing drugs, though others indeed think of harm reduction as merely

a way-station toward, or an argument supporting, legalization. Notably, some nations, such as

Australia, have embraced syringe exchange programs early and aggressively, and have largely

avoided the HIV/AIDS epidemic that has plagued drug users in the US. These programs are less

successful at constraining hepatitis because that virus is so much more virulent. Likewise,

Australia, Canada, and a number of European countries operate, or at least tolerate, "supervised

injection facilities." These are rooms where proctors permit and oversee drug injections so they

can detect and respond to any overdoses as quickly as possible.

Information campaigns that inform and encourage responsible use can substitute for programs

that preach abstinence. In a study in Washington state, death rates for former inmates in the first

two weeks after release are elevated by more than a factor of ten as compared with other state

residents (adjusted for age, sex and race), with drug overdose being the leading cause of death

(32).While incarceration can force users to abstain and thus largely reverse their acquired

tolerance to large doses, abstinence alone may not eliminate long-term craving. A variety of

ways to promote responsible use in lieu of abstinence have been suggested. One could try to

prevent some of those deaths by warning inmates before release not to return immediately to

their pre-incarceration dosages. Weeks et al (2006) suggest training active drug users to be

"Peer/Public Health Advocates" who promote safer forms of drug taking.

Conclusion

From a consequentialist perspective, prohibiting drugs is good policy only if prohibition reduces

use enough to reduce total damage (compared to legalization) despite greater harm per dose to

users and the burdens created by illicit markets. Prohibition imposes very visible harms on a

minority of identifiable individuals, most notably those whom it incarcerates and victims of black-

market crime. Its benefits are invisible, consisting primarily of all the people who are not

now drug-dependent but who would have been if drugs had been cheaper, less stigmatized, and

more available when they were younger.

There is widespread dissatisfaction with the US approach to prohibition, but the government has

alternatives other than outright legalization. Indeed, since no country (not even the Netherlands)

incarcerated for drug law violations as there are today (23).

Embracing harm reduction

For better and for worse, a principal goal of drug policy in the U.S. since the late nineteenth

century has been to discourage, or minimize, drug use. While the official rhetoric speaks of

"drug use and related consequences" the emphasis is on reducing use, and on reducing

consequences by reducing use. We can conceptualize drug harm via some very basic arithmetic:

(ProQuest: ... denotes formula omitted.)

While US policy has focused on ways to reduce use (both number of users and dosage per

user), other countries prioritize reducing the third term in the harm equation. Such so-called

"harm reduction" strategies focus on minimizing the consequences of drug use, and embrace

policies that reduce consequences even if they do not reduce use. MacCoun (31) offered an

insightful discussion of the distinction between "use reduction" and "harm reduction."

Favoring harm reduction in certain US policy circles is about as popular as was favoring

communism at the height of the McCarthy era, the phrase being seen as code for legalization or

implying that one tolerates vice. However, for many, harm reduction merely entails taking a

pragmatic public- health approach within an overall framework that continues to ban commercial

production and distribution.

Some harm reduction advocates believe that many dire consequences of our current prohibition

can be reversed without legalizing drugs, though others indeed think of harm reduction as merely

a way-station toward, or an argument supporting, legalization. Notably, some nations, such as

Australia, have embraced syringe exchange programs early and aggressively, and have largely

avoided the HIV/AIDS epidemic that has plagued drug users in the US. These programs are less

successful at constraining hepatitis because that virus is so much more virulent. Likewise,

Australia, Canada, and a number of European countries operate, or at least tolerate, "supervised

injection facilities." These are rooms where proctors permit and oversee drug injections so they

can detect and respond to any overdoses as quickly as possible.

Information campaigns that inform and encourage responsible use can substitute for programs

that preach abstinence. In a study in Washington state, death rates for former inmates in the first

two weeks after release are elevated by more than a factor of ten as compared with other state

residents (adjusted for age, sex and race), with drug overdose being the leading cause of death

(32).While incarceration can force users to abstain and thus largely reverse their acquired

tolerance to large doses, abstinence alone may not eliminate long-term craving. A variety of

ways to promote responsible use in lieu of abstinence have been suggested. One could try to

prevent some of those deaths by warning inmates before release not to return immediately to

their pre-incarceration dosages. Weeks et al (2006) suggest training active drug users to be

"Peer/Public Health Advocates" who promote safer forms of drug taking.

Conclusion

From a consequentialist perspective, prohibiting drugs is good policy only if prohibition reduces

use enough to reduce total damage (compared to legalization) despite greater harm per dose to

users and the burdens created by illicit markets. Prohibition imposes very visible harms on a

minority of identifiable individuals, most notably those whom it incarcerates and victims of black-

market crime. Its benefits are invisible, consisting primarily of all the people who are not

now drug-dependent but who would have been if drugs had been cheaper, less stigmatized, and

more available when they were younger.

There is widespread dissatisfaction with the US approach to prohibition, but the government has

alternatives other than outright legalization. Indeed, since no country (not even the Netherlands)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.