Hospital Staffing and Health Care–Associated Infections: A Systematic Review of the Literature

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/20

|10

|8786

|72

AI Summary

This systematic review examines the relationship between hospital staffing and the risk of acquiring health care–associated infections (HAIs). The review found that increased staffing is related to a decreased risk of acquiring HAIs. More rigorous and consistent research designs, definitions, and risk-adjusted HAI data are needed in future studies exploring this area.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Hospital Staffing and Health Care–Associated Infections:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac; Anne Gardner, PhD; Patricia W. Stone, PhD, RN, FAAN; Lisa Hall, PhD;

Monika Pogorzelska-Maziarz, PhD

Background:Previous literature has linked the level and types of staffing of health facilities to the risk of acquiring a health

care–associated infection (HAI). Investigating this relationship is challenging because of the lack of rigorous study designs

and the use of varying definitions and measures of both staffing and HAIs.

Methods:The objective of this study was to understand and synthesize the most recent research on the relationship of

hospital staffing and HAI risk. A systematic review was undertaken. Electronic databases MEDLINE, PubMed, and the Cu-

mulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) were searched for studies published between January 1,

2000, and November 30, 2015.

Results:Fifty-four articles were included in the review. The majority of studies examined the relationship between nurse

staffing and HAIs (n = 50, 92.6%) and found nurse staffing variables to be associated with an increase in HAI rates (n = 40,

74.1%). Only 5 studies addressed non-nurse staffing, and those had mixed results. Physician staffing was associated with an

increased HAI risk in 1 of 3 studies. Studies varied in design and methodology, as well as in their use of operational defi-

nitions and measures of staffing and HAIs.

Conclusion:Despite the lack of consistency of the included studies, overall, the results of this systematic review demon-

strate that increased staffing is related to decreased risk of acquiring HAIs. More rigorous and consistent research designs,

definitions, and risk-adjusted HAI data are needed in future studies exploring this area.

Health care–associated infections (HAIs) are a serious

patient safety issue that result in increased morbidity

and mortality as well as excessive health resource utilization.1

Recent estimates from the United States show that on any

given day approximately 1 of every 25 inpatients in acute

care hospitals has at least one HAI.2 In Europe HAIs also

represent a considerable burden, with more than 2.5 million

cases occurring each year,resulting in approximately 2.5

million disability-adjusted life years.3 Given the significant

burden of HAIs with the potential for adverse outcomes in

patients, there is much interest in understanding their trans-

mission, prevention, and control. One particular issue is the

relationship between levels and types of staffing of health fa-

cilities and HAIs. A number of organizational factors that

influence the risk of HAIs have been identified, including

standardized HAI case definitions, adequate data sources, and

complex risk adjustment methods.9 Furthermore, the web

of causation linking staffing and HAI is difficult to under-

stand and may include factors such as the complexity of the

infection process,lack of time to comply with infection

control measures, and job-related burnout.9 Methodologi-

cal issues in studies examining the association between hospital

staffing and adverse outcomes have also been identified. These

include lack of application of standardized definitions of nurse

staffing,different databases,and diverse risk adjustment

methods.10 In addition, the temporal relationship between

staffing and HAI occurrence has recently been noted as a

methodological problem in studies examining hospital staff-

ing and HAI.11 HAIs are by definition infections that occur

48 hours after hospitaladmission.11 Hence,staffing levels

The Joint Commission Journalon Quality and Patient Safety 2018; 44:613–622

A Systematic Review of the Literature

Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac; Anne Gardner, PhD; Patricia W. Stone, PhD, RN, FAAN; Lisa Hall, PhD;

Monika Pogorzelska-Maziarz, PhD

Background:Previous literature has linked the level and types of staffing of health facilities to the risk of acquiring a health

care–associated infection (HAI). Investigating this relationship is challenging because of the lack of rigorous study designs

and the use of varying definitions and measures of both staffing and HAIs.

Methods:The objective of this study was to understand and synthesize the most recent research on the relationship of

hospital staffing and HAI risk. A systematic review was undertaken. Electronic databases MEDLINE, PubMed, and the Cu-

mulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) were searched for studies published between January 1,

2000, and November 30, 2015.

Results:Fifty-four articles were included in the review. The majority of studies examined the relationship between nurse

staffing and HAIs (n = 50, 92.6%) and found nurse staffing variables to be associated with an increase in HAI rates (n = 40,

74.1%). Only 5 studies addressed non-nurse staffing, and those had mixed results. Physician staffing was associated with an

increased HAI risk in 1 of 3 studies. Studies varied in design and methodology, as well as in their use of operational defi-

nitions and measures of staffing and HAIs.

Conclusion:Despite the lack of consistency of the included studies, overall, the results of this systematic review demon-

strate that increased staffing is related to decreased risk of acquiring HAIs. More rigorous and consistent research designs,

definitions, and risk-adjusted HAI data are needed in future studies exploring this area.

Health care–associated infections (HAIs) are a serious

patient safety issue that result in increased morbidity

and mortality as well as excessive health resource utilization.1

Recent estimates from the United States show that on any

given day approximately 1 of every 25 inpatients in acute

care hospitals has at least one HAI.2 In Europe HAIs also

represent a considerable burden, with more than 2.5 million

cases occurring each year,resulting in approximately 2.5

million disability-adjusted life years.3 Given the significant

burden of HAIs with the potential for adverse outcomes in

patients, there is much interest in understanding their trans-

mission, prevention, and control. One particular issue is the

relationship between levels and types of staffing of health fa-

cilities and HAIs. A number of organizational factors that

influence the risk of HAIs have been identified, including

standardized HAI case definitions, adequate data sources, and

complex risk adjustment methods.9 Furthermore, the web

of causation linking staffing and HAI is difficult to under-

stand and may include factors such as the complexity of the

infection process,lack of time to comply with infection

control measures, and job-related burnout.9 Methodologi-

cal issues in studies examining the association between hospital

staffing and adverse outcomes have also been identified. These

include lack of application of standardized definitions of nurse

staffing,different databases,and diverse risk adjustment

methods.10 In addition, the temporal relationship between

staffing and HAI occurrence has recently been noted as a

methodological problem in studies examining hospital staff-

ing and HAI.11 HAIs are by definition infections that occur

48 hours after hospitaladmission.11 Hence,staffing levels

The Joint Commission Journalon Quality and Patient Safety 2018; 44:613–622

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

hospital staffing and HAI risk will inform health adminis-

trators,policy makers,and researchers on strategies for

preventing HAIs and thereby improving patient outcomes.

This systematic review therefore aims to examine the asso-

ciation between hospitalstaffing and patients’risk of

developing HAIs in hospital settings.

METHODS

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to iden-

tify publications that examine the relationships between

hospital staffing and patients’ risk of developing an HAI in

the hospitalsetting. The approach used is consistent with

a previous systematic review of this topic.12Reporting of this

systematic review complied with the preferred reporting items

for systematic reviewsand meta-analyses(PRISMA)

guidelines.14

Protocol and Registration

The protocol for conducting this review was registered prior

to commencement of the review and can be accessed on the

internationalprospective register ofsystematic reviews

(PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42015032398).

Search Strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted accord-

ing to the registered protocol. Electronic databases PubMed

and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Lit-

erature (CINAHL) were searched for studies published

between January 1,2000,and November 30,2015. The

search was performed on December 7,2015.A combina-

tion of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms

were used,including “infection control,” “staffing,” and

“healthcare associated infection.” For retrieved articles,a

manual search of the reference lists was also performed to

identify any additional studies. Searches were restricted to

studies published in the English language only.

Selection Criteria

The inclusion criteria were all observational studies (cohort,

case control, or cross-sectional) examining the relationship

community-acquired infections, and articles written in lan-

guages other than English.

Definitions

For the purpose of this systematic review, the following defi-

nitions were used:

• Hospital staffing was defined as nurse staffing, medical

staffing, or infection prevention and control staffing.

• Nurse staffing levels were described using one or more

of the following variables:levelof staffing (nurse-to-

patientratio or nursing hours per patient-day or

admission), skill mix, use of float or nonpermanent staff,

absenteeism and/or overtime, workload.

• Health care–associated infectionscomprised blood-

stream infection,pneumonia,urinary tract infection,

wound or surgical site infection, organism-specific in-

fections (for example, Clostridium difficile infection) that

were defined as being health care–associated in the studies

included in the review. The definition of HAI in the

included studies was based on a recognized standard;

that is,a definition agreed on or published by a pro-

fessional association or government agency (for example,

the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]),

a definition widely used in the published literature, or

an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Re-

vision,ClinicalModification (ICD-9-CM) code that

constitutes an HAI (not just any infection).

Study Selection

The titles and abstracts of all articles identified were exam-

ined and assessed for relevance and appropriateness to the

systematic review aim,and those not relevant were ex-

cluded. The fulltexts of potentially relevant articles were

obtained to further assess eligibility based on the inclusion

and exclusion criteria. Articles with data relevant to the sys-

tematic review were included. The electronic database search

and study selection process were performed by trained re-

search assistants. At each stage of the study selection process,

10% of articles retrieved were selected at random and re-

viewed by the study lead author as a cross-check against study

eligibility.Any discrepancies in the application of the in-

clusion or exclusion criteria were resolved by the lead author.

614 Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac, et al HospitalStaffing and Risk of Infection

trators,policy makers,and researchers on strategies for

preventing HAIs and thereby improving patient outcomes.

This systematic review therefore aims to examine the asso-

ciation between hospitalstaffing and patients’risk of

developing HAIs in hospital settings.

METHODS

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to iden-

tify publications that examine the relationships between

hospital staffing and patients’ risk of developing an HAI in

the hospitalsetting. The approach used is consistent with

a previous systematic review of this topic.12Reporting of this

systematic review complied with the preferred reporting items

for systematic reviewsand meta-analyses(PRISMA)

guidelines.14

Protocol and Registration

The protocol for conducting this review was registered prior

to commencement of the review and can be accessed on the

internationalprospective register ofsystematic reviews

(PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42015032398).

Search Strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted accord-

ing to the registered protocol. Electronic databases PubMed

and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Lit-

erature (CINAHL) were searched for studies published

between January 1,2000,and November 30,2015. The

search was performed on December 7,2015.A combina-

tion of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms

were used,including “infection control,” “staffing,” and

“healthcare associated infection.” For retrieved articles,a

manual search of the reference lists was also performed to

identify any additional studies. Searches were restricted to

studies published in the English language only.

Selection Criteria

The inclusion criteria were all observational studies (cohort,

case control, or cross-sectional) examining the relationship

community-acquired infections, and articles written in lan-

guages other than English.

Definitions

For the purpose of this systematic review, the following defi-

nitions were used:

• Hospital staffing was defined as nurse staffing, medical

staffing, or infection prevention and control staffing.

• Nurse staffing levels were described using one or more

of the following variables:levelof staffing (nurse-to-

patientratio or nursing hours per patient-day or

admission), skill mix, use of float or nonpermanent staff,

absenteeism and/or overtime, workload.

• Health care–associated infectionscomprised blood-

stream infection,pneumonia,urinary tract infection,

wound or surgical site infection, organism-specific in-

fections (for example, Clostridium difficile infection) that

were defined as being health care–associated in the studies

included in the review. The definition of HAI in the

included studies was based on a recognized standard;

that is,a definition agreed on or published by a pro-

fessional association or government agency (for example,

the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]),

a definition widely used in the published literature, or

an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Re-

vision,ClinicalModification (ICD-9-CM) code that

constitutes an HAI (not just any infection).

Study Selection

The titles and abstracts of all articles identified were exam-

ined and assessed for relevance and appropriateness to the

systematic review aim,and those not relevant were ex-

cluded. The fulltexts of potentially relevant articles were

obtained to further assess eligibility based on the inclusion

and exclusion criteria. Articles with data relevant to the sys-

tematic review were included. The electronic database search

and study selection process were performed by trained re-

search assistants. At each stage of the study selection process,

10% of articles retrieved were selected at random and re-

viewed by the study lead author as a cross-check against study

eligibility.Any discrepancies in the application of the in-

clusion or exclusion criteria were resolved by the lead author.

614 Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac, et al HospitalStaffing and Risk of Infection

incidence or prevalence data. Data extracted were crossed-

checked by a different research assistant.

Risk of Bias

An assessment of study quality and risk of bias in the ar-

ticles included in the review was conducted using the

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.15,16

The content validity and inter-

rater reliability of this tool has been established.16One reviewer

undertook this assessment independently, with a random 10%

of articles reviewed by a second reviewer. No discrepancies

were identified.

Data Analysis

Extracted data from included studies were synthesized and

summarized in evidence tables.Summary tables include

studies that examined nurse staffing and single site–specific

HAI, nurse staffing and multiple types of HAI, nurse staff-

ing and organism-specific HAI, nurse staffing and unspecified

HAI, and non-nurse staffing and HAI.Given the hetero-

geneity of the studies included in the systematic review,

pooling of data in a meta-analysis was not feasible.

RESULTS

Overview

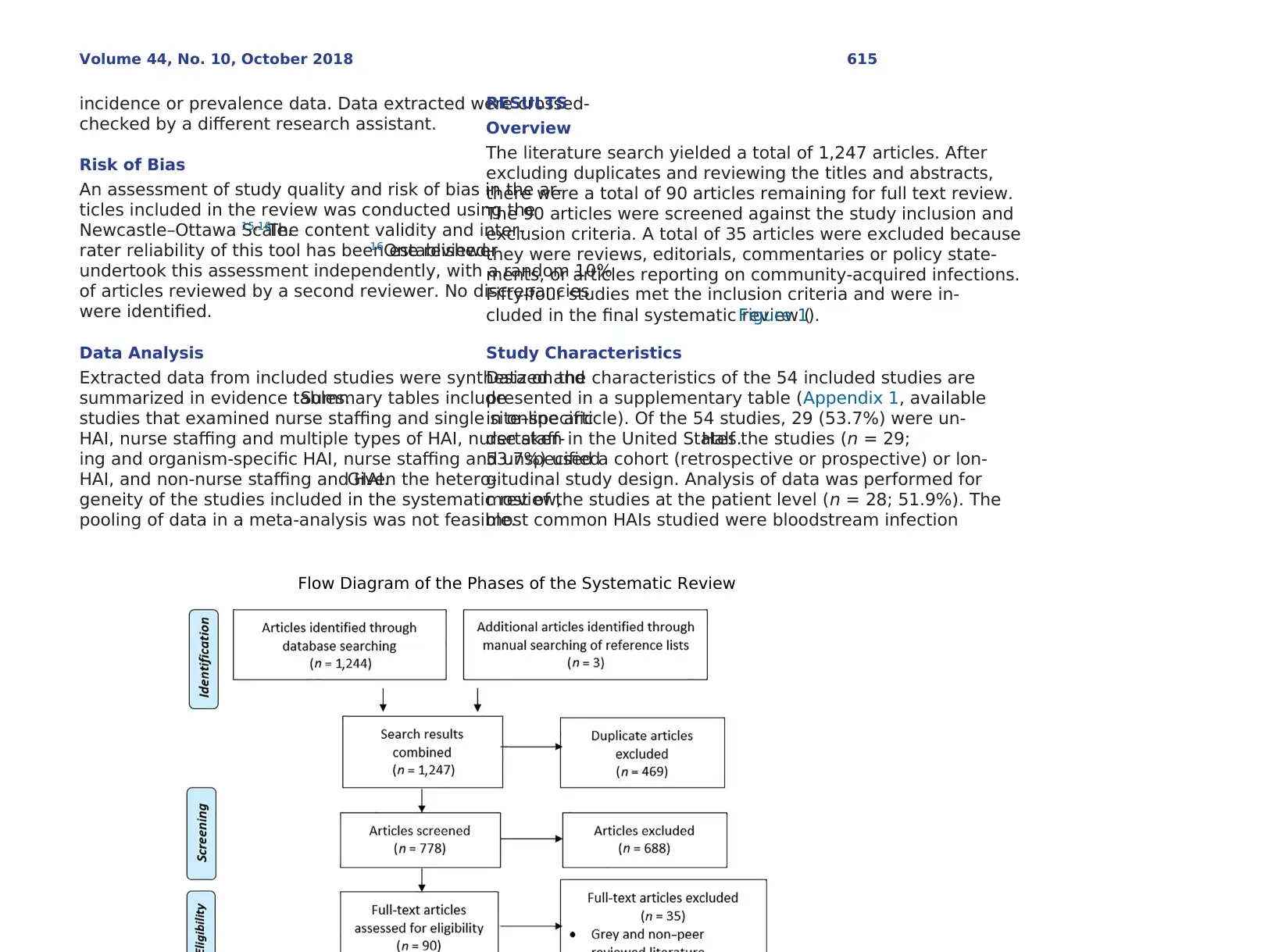

The literature search yielded a total of 1,247 articles. After

excluding duplicates and reviewing the titles and abstracts,

there were a total of 90 articles remaining for full text review.

The 90 articles were screened against the study inclusion and

exclusion criteria. A total of 35 articles were excluded because

they were reviews, editorials, commentaries or policy state-

ments, or articles reporting on community-acquired infections.

Fifty-four studies met the inclusion criteria and were in-

cluded in the final systematic review (Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

Data on the characteristics of the 54 included studies are

presented in a supplementary table (Appendix 1, available

in online article). Of the 54 studies, 29 (53.7%) were un-

dertaken in the United States.Half the studies (n = 29;

53.7%) used a cohort (retrospective or prospective) or lon-

gitudinal study design. Analysis of data was performed for

most of the studies at the patient level (n = 28; 51.9%). The

most common HAIs studied were bloodstream infection

Flow Diagram of the Phases of the Systematic Review

Volume 44, No. 10, October 2018 615

checked by a different research assistant.

Risk of Bias

An assessment of study quality and risk of bias in the ar-

ticles included in the review was conducted using the

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.15,16

The content validity and inter-

rater reliability of this tool has been established.16One reviewer

undertook this assessment independently, with a random 10%

of articles reviewed by a second reviewer. No discrepancies

were identified.

Data Analysis

Extracted data from included studies were synthesized and

summarized in evidence tables.Summary tables include

studies that examined nurse staffing and single site–specific

HAI, nurse staffing and multiple types of HAI, nurse staff-

ing and organism-specific HAI, nurse staffing and unspecified

HAI, and non-nurse staffing and HAI.Given the hetero-

geneity of the studies included in the systematic review,

pooling of data in a meta-analysis was not feasible.

RESULTS

Overview

The literature search yielded a total of 1,247 articles. After

excluding duplicates and reviewing the titles and abstracts,

there were a total of 90 articles remaining for full text review.

The 90 articles were screened against the study inclusion and

exclusion criteria. A total of 35 articles were excluded because

they were reviews, editorials, commentaries or policy state-

ments, or articles reporting on community-acquired infections.

Fifty-four studies met the inclusion criteria and were in-

cluded in the final systematic review (Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

Data on the characteristics of the 54 included studies are

presented in a supplementary table (Appendix 1, available

in online article). Of the 54 studies, 29 (53.7%) were un-

dertaken in the United States.Half the studies (n = 29;

53.7%) used a cohort (retrospective or prospective) or lon-

gitudinal study design. Analysis of data was performed for

most of the studies at the patient level (n = 28; 51.9%). The

most common HAIs studied were bloodstream infection

Flow Diagram of the Phases of the Systematic Review

Volume 44, No. 10, October 2018 615

(BSI) (n = 30; 55.6%), pneumonia (n = 24; 44.4%), urinary

tract infection (UTI) (n = 21;38.9%),and wound infec-

tion (n = 8; 14.8%). The most frequent type of hospital staff

examined were nurses (n = 50; 92.6%). Of these, the ma-

jority (n = 40; 74.1%) found a significant association between

the nurse staffing variable(s) studied and HAI risk.The

number of stars awarded to studies as part of the risk of bias

assessment ranged from three to nine, with the full assess-

ment presented in a supplementary table (Appendix 2,

available in online article). Twenty-one of the 54 articles re-

ceived five or more stars. Studies were of moderate quality,

however,as many of the included studies did not control

for potential confounders (comparability). All studies were

included in the review, regardless of the risk of bias assess-

ment.As no meta-analysis was performed and there was

considerable heterogeneity in the study methods, no further

subanalysis of results based on the risk of bias assessment

was undertaken.

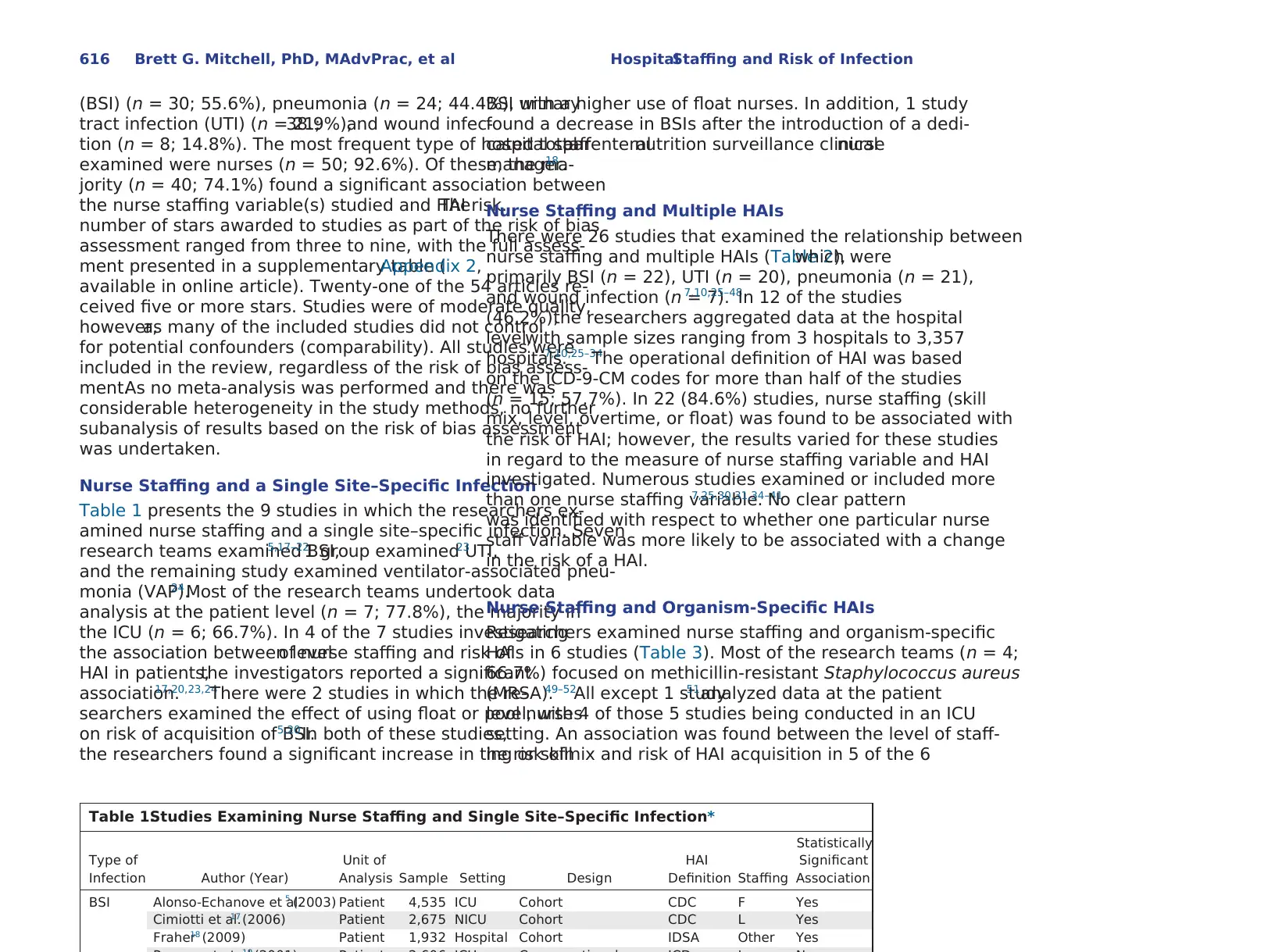

Nurse Staffing and a Single Site–Specific Infection

Table 1 presents the 9 studies in which the researchers ex-

amined nurse staffing and a single site–specific infection. Seven

research teams examined BSI,5,17–22

1 group examined UTI,23

and the remaining study examined ventilator-associated pneu-

monia (VAP).24 Most of the research teams undertook data

analysis at the patient level (n = 7; 77.8%), the majority in

the ICU (n = 6; 66.7%). In 4 of the 7 studies investigating

the association between levelof nurse staffing and risk of

HAI in patients,the investigators reported a significant

association.17,20,23,24

There were 2 studies in which the re-

searchers examined the effect of using float or pool nurses

on risk of acquisition of BSI.5,20 In both of these studies,

the researchers found a significant increase in the risk of

BSI with a higher use of float nurses. In addition, 1 study

found a decrease in BSIs after the introduction of a dedi-

cated totalparenteralnutrition surveillance clinicalnurse

manager.18

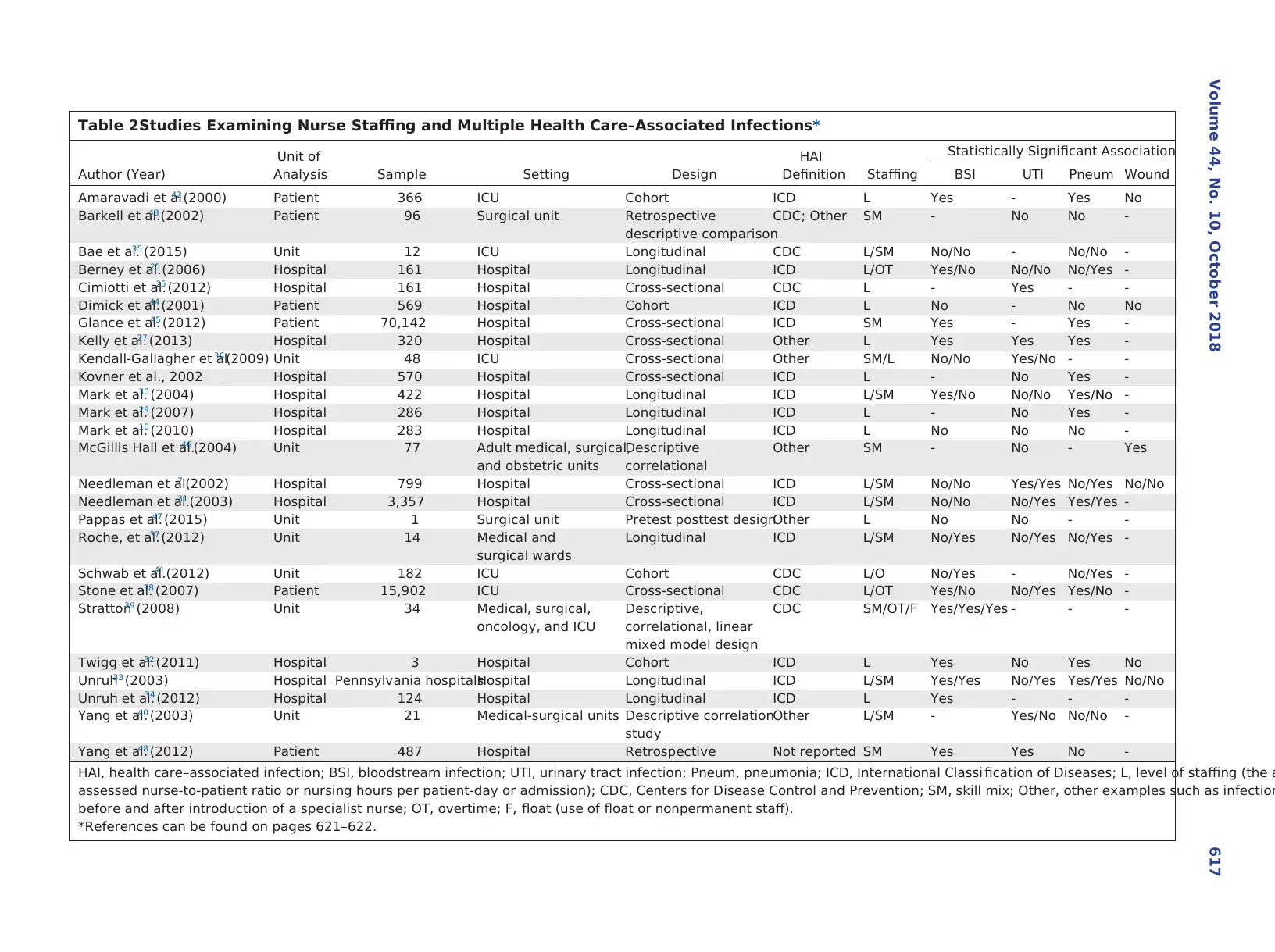

Nurse Staffing and Multiple HAIs

There were 26 studies that examined the relationship between

nurse staffing and multiple HAIs (Table 2),which were

primarily BSI (n = 22), UTI (n = 20), pneumonia (n = 21),

and wound infection (n = 7).7,10,25–48

In 12 of the studies

(46.2%),the researchers aggregated data at the hospital

level,with sample sizes ranging from 3 hospitals to 3,357

hospitals.7,10,25–34

The operational definition of HAI was based

on the ICD-9-CM codes for more than half of the studies

(n = 15; 57.7%). In 22 (84.6%) studies, nurse staffing (skill

mix, level, overtime, or float) was found to be associated with

the risk of HAI; however, the results varied for these studies

in regard to the measure of nurse staffing variable and HAI

investigated. Numerous studies examined or included more

than one nurse staffing variable.7,25,30,31,34–41

No clear pattern

was identified with respect to whether one particular nurse

staff variable was more likely to be associated with a change

in the risk of a HAI.

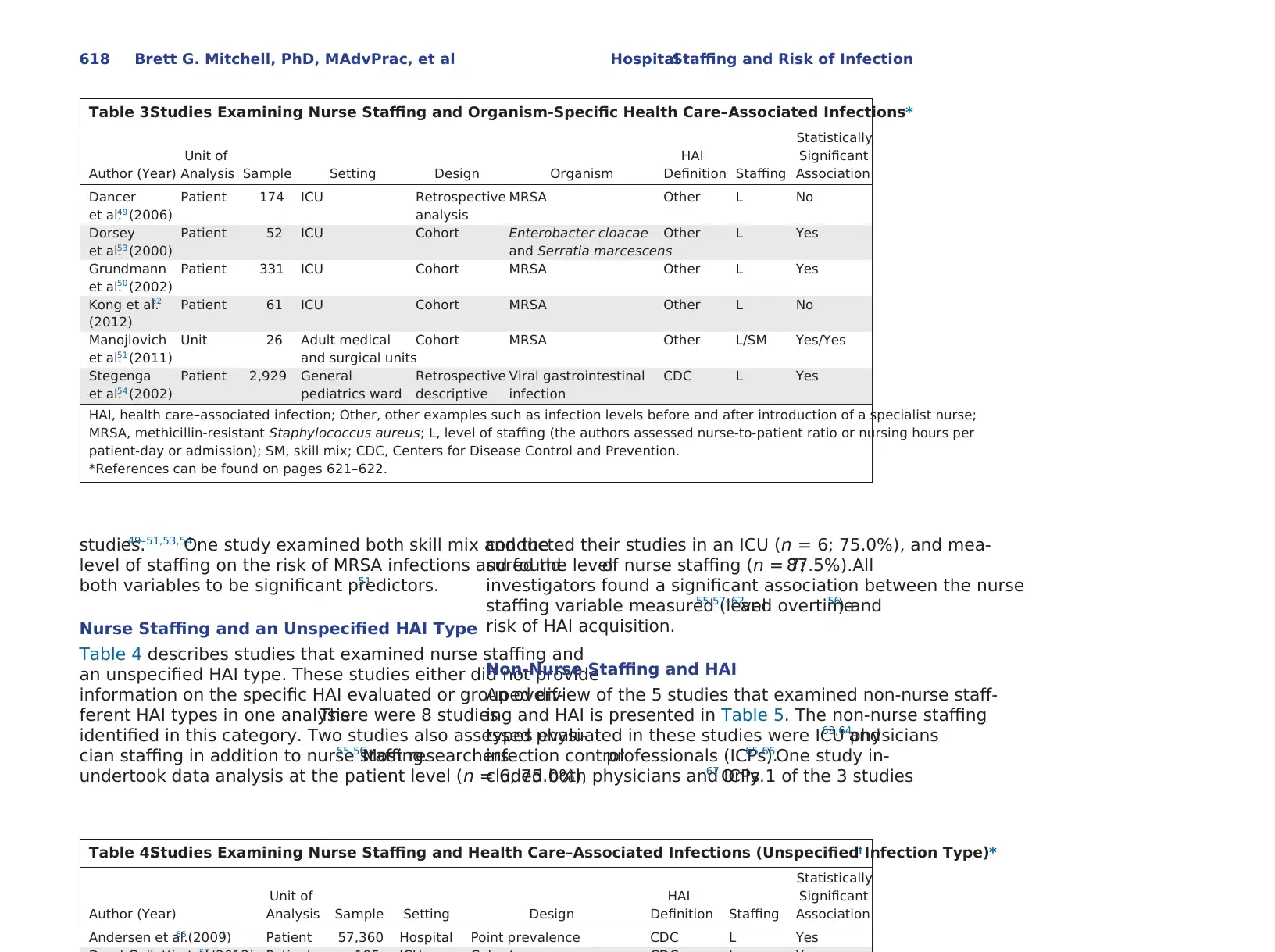

Nurse Staffing and Organism-Specific HAIs

Researchers examined nurse staffing and organism-specific

HAIs in 6 studies (Table 3). Most of the research teams (n = 4;

66.7%) focused on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

(MRSA).49–52

All except 1 study51analyzed data at the patient

level, with 4 of those 5 studies being conducted in an ICU

setting. An association was found between the level of staff-

ing or skillmix and risk of HAI acquisition in 5 of the 6

Table 1.Studies Examining Nurse Staffing and Single Site–Specific Infection*

Type of

Infection Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design

HAI

Definition Staffing

Statistically

Significant

Association

BSI Alonso-Echanove et al.5 (2003) Patient 4,535 ICU Cohort CDC F Yes

Cimiotti et al.17 (2006) Patient 2,675 NICU Cohort CDC L Yes

Fraher18 (2009) Patient 1,932 Hospital Cohort IDSA Other Yes

616 Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac, et al HospitalStaffing and Risk of Infection

tract infection (UTI) (n = 21;38.9%),and wound infec-

tion (n = 8; 14.8%). The most frequent type of hospital staff

examined were nurses (n = 50; 92.6%). Of these, the ma-

jority (n = 40; 74.1%) found a significant association between

the nurse staffing variable(s) studied and HAI risk.The

number of stars awarded to studies as part of the risk of bias

assessment ranged from three to nine, with the full assess-

ment presented in a supplementary table (Appendix 2,

available in online article). Twenty-one of the 54 articles re-

ceived five or more stars. Studies were of moderate quality,

however,as many of the included studies did not control

for potential confounders (comparability). All studies were

included in the review, regardless of the risk of bias assess-

ment.As no meta-analysis was performed and there was

considerable heterogeneity in the study methods, no further

subanalysis of results based on the risk of bias assessment

was undertaken.

Nurse Staffing and a Single Site–Specific Infection

Table 1 presents the 9 studies in which the researchers ex-

amined nurse staffing and a single site–specific infection. Seven

research teams examined BSI,5,17–22

1 group examined UTI,23

and the remaining study examined ventilator-associated pneu-

monia (VAP).24 Most of the research teams undertook data

analysis at the patient level (n = 7; 77.8%), the majority in

the ICU (n = 6; 66.7%). In 4 of the 7 studies investigating

the association between levelof nurse staffing and risk of

HAI in patients,the investigators reported a significant

association.17,20,23,24

There were 2 studies in which the re-

searchers examined the effect of using float or pool nurses

on risk of acquisition of BSI.5,20 In both of these studies,

the researchers found a significant increase in the risk of

BSI with a higher use of float nurses. In addition, 1 study

found a decrease in BSIs after the introduction of a dedi-

cated totalparenteralnutrition surveillance clinicalnurse

manager.18

Nurse Staffing and Multiple HAIs

There were 26 studies that examined the relationship between

nurse staffing and multiple HAIs (Table 2),which were

primarily BSI (n = 22), UTI (n = 20), pneumonia (n = 21),

and wound infection (n = 7).7,10,25–48

In 12 of the studies

(46.2%),the researchers aggregated data at the hospital

level,with sample sizes ranging from 3 hospitals to 3,357

hospitals.7,10,25–34

The operational definition of HAI was based

on the ICD-9-CM codes for more than half of the studies

(n = 15; 57.7%). In 22 (84.6%) studies, nurse staffing (skill

mix, level, overtime, or float) was found to be associated with

the risk of HAI; however, the results varied for these studies

in regard to the measure of nurse staffing variable and HAI

investigated. Numerous studies examined or included more

than one nurse staffing variable.7,25,30,31,34–41

No clear pattern

was identified with respect to whether one particular nurse

staff variable was more likely to be associated with a change

in the risk of a HAI.

Nurse Staffing and Organism-Specific HAIs

Researchers examined nurse staffing and organism-specific

HAIs in 6 studies (Table 3). Most of the research teams (n = 4;

66.7%) focused on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

(MRSA).49–52

All except 1 study51analyzed data at the patient

level, with 4 of those 5 studies being conducted in an ICU

setting. An association was found between the level of staff-

ing or skillmix and risk of HAI acquisition in 5 of the 6

Table 1.Studies Examining Nurse Staffing and Single Site–Specific Infection*

Type of

Infection Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design

HAI

Definition Staffing

Statistically

Significant

Association

BSI Alonso-Echanove et al.5 (2003) Patient 4,535 ICU Cohort CDC F Yes

Cimiotti et al.17 (2006) Patient 2,675 NICU Cohort CDC L Yes

Fraher18 (2009) Patient 1,932 Hospital Cohort IDSA Other Yes

616 Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac, et al HospitalStaffing and Risk of Infection

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Table 2.Studies Examining Nurse Staffing and Multiple Health Care–Associated Infections*

Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design

HAI

Definition Staffing

Statistically Significant Association

BSI UTI Pneum Wound

Amaravadi et al.42 (2000) Patient 366 ICU Cohort ICD L Yes - Yes No

Barkell et al.43 (2002) Patient 96 Surgical unit Retrospective

descriptive comparison

CDC; Other SM - No No -

Bae et al.35 (2015) Unit 12 ICU Longitudinal CDC L/SM No/No - No/No -

Berney et al.25 (2006) Hospital 161 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L/OT Yes/No No/No No/Yes -

Cimiotti et al.25 (2012) Hospital 161 Hospital Cross-sectional CDC L - Yes - -

Dimick et al.44 (2001) Patient 569 Hospital Cohort ICD L No - No No

Glance et al.45 (2012) Patient 70,142 Hospital Cross-sectional ICD SM Yes - Yes -

Kelly et al.27 (2013) Hospital 320 Hospital Cross-sectional Other L Yes Yes Yes -

Kendall-Gallagher et al.36 (2009) Unit 48 ICU Cross-sectional Other SM/L No/No Yes/No - -

Kovner et al., 2002 Hospital 570 Hospital Cross-sectional ICD L - No Yes -

Mark et al.30 (2004) Hospital 422 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L/SM Yes/No No/No Yes/No -

Mark et al.29 (2007) Hospital 286 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L - No Yes -

Mark et al.10 (2010) Hospital 283 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L No No No -

McGillis Hall et al.46 (2004) Unit 77 Adult medical, surgical,

and obstetric units

Descriptive

correlational

Other SM - No - Yes

Needleman et al.7 (2002) Hospital 799 Hospital Cross-sectional ICD L/SM No/No Yes/Yes No/Yes No/No

Needleman et al.31 (2003) Hospital 3,357 Hospital Cross-sectional ICD L/SM No/No No/Yes Yes/Yes -

Pappas et al.47 (2015) Unit 1 Surgical unit Pretest posttest designOther L No No - -

Roche, et al.37 (2012) Unit 14 Medical and

surgical wards

Longitudinal ICD L/SM No/Yes No/Yes No/Yes -

Schwab et al.41 (2012) Unit 182 ICU Cohort CDC L/O No/Yes - No/Yes -

Stone et al.38 (2007) Patient 15,902 ICU Cross-sectional CDC L/OT Yes/No No/Yes Yes/No -

Stratton39 (2008) Unit 34 Medical, surgical,

oncology, and ICU

Descriptive,

correlational, linear

mixed model design

CDC SM/OT/F Yes/Yes/Yes - - -

Twigg et al.32 (2011) Hospital 3 Hospital Cohort ICD L Yes No Yes No

Unruh33 (2003) Hospital Pennsylvania hospitalsHospital Longitudinal ICD L/SM Yes/Yes No/Yes Yes/Yes No/No

Unruh et al.34 (2012) Hospital 124 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L Yes - - -

Yang et al.40 (2003) Unit 21 Medical-surgical units Descriptive correlation

study

Other L/SM - Yes/No No/No -

Yang et al.48 (2012) Patient 487 Hospital Retrospective Not reported SM Yes Yes No -

HAI, health care–associated infection; BSI, bloodstream infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; Pneum, pneumonia; ICD, International Classi fication of Diseases; L, level of staffing (the a

assessed nurse-to-patient ratio or nursing hours per patient-day or admission); CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; SM, skill mix; Other, other examples such as infection

before and after introduction of a specialist nurse; OT, overtime; F, float (use of float or nonpermanent staff).

*References can be found on pages 621–622.

Volume 44, No. 10, October 2018 617

Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design

HAI

Definition Staffing

Statistically Significant Association

BSI UTI Pneum Wound

Amaravadi et al.42 (2000) Patient 366 ICU Cohort ICD L Yes - Yes No

Barkell et al.43 (2002) Patient 96 Surgical unit Retrospective

descriptive comparison

CDC; Other SM - No No -

Bae et al.35 (2015) Unit 12 ICU Longitudinal CDC L/SM No/No - No/No -

Berney et al.25 (2006) Hospital 161 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L/OT Yes/No No/No No/Yes -

Cimiotti et al.25 (2012) Hospital 161 Hospital Cross-sectional CDC L - Yes - -

Dimick et al.44 (2001) Patient 569 Hospital Cohort ICD L No - No No

Glance et al.45 (2012) Patient 70,142 Hospital Cross-sectional ICD SM Yes - Yes -

Kelly et al.27 (2013) Hospital 320 Hospital Cross-sectional Other L Yes Yes Yes -

Kendall-Gallagher et al.36 (2009) Unit 48 ICU Cross-sectional Other SM/L No/No Yes/No - -

Kovner et al., 2002 Hospital 570 Hospital Cross-sectional ICD L - No Yes -

Mark et al.30 (2004) Hospital 422 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L/SM Yes/No No/No Yes/No -

Mark et al.29 (2007) Hospital 286 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L - No Yes -

Mark et al.10 (2010) Hospital 283 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L No No No -

McGillis Hall et al.46 (2004) Unit 77 Adult medical, surgical,

and obstetric units

Descriptive

correlational

Other SM - No - Yes

Needleman et al.7 (2002) Hospital 799 Hospital Cross-sectional ICD L/SM No/No Yes/Yes No/Yes No/No

Needleman et al.31 (2003) Hospital 3,357 Hospital Cross-sectional ICD L/SM No/No No/Yes Yes/Yes -

Pappas et al.47 (2015) Unit 1 Surgical unit Pretest posttest designOther L No No - -

Roche, et al.37 (2012) Unit 14 Medical and

surgical wards

Longitudinal ICD L/SM No/Yes No/Yes No/Yes -

Schwab et al.41 (2012) Unit 182 ICU Cohort CDC L/O No/Yes - No/Yes -

Stone et al.38 (2007) Patient 15,902 ICU Cross-sectional CDC L/OT Yes/No No/Yes Yes/No -

Stratton39 (2008) Unit 34 Medical, surgical,

oncology, and ICU

Descriptive,

correlational, linear

mixed model design

CDC SM/OT/F Yes/Yes/Yes - - -

Twigg et al.32 (2011) Hospital 3 Hospital Cohort ICD L Yes No Yes No

Unruh33 (2003) Hospital Pennsylvania hospitalsHospital Longitudinal ICD L/SM Yes/Yes No/Yes Yes/Yes No/No

Unruh et al.34 (2012) Hospital 124 Hospital Longitudinal ICD L Yes - - -

Yang et al.40 (2003) Unit 21 Medical-surgical units Descriptive correlation

study

Other L/SM - Yes/No No/No -

Yang et al.48 (2012) Patient 487 Hospital Retrospective Not reported SM Yes Yes No -

HAI, health care–associated infection; BSI, bloodstream infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; Pneum, pneumonia; ICD, International Classi fication of Diseases; L, level of staffing (the a

assessed nurse-to-patient ratio or nursing hours per patient-day or admission); CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; SM, skill mix; Other, other examples such as infection

before and after introduction of a specialist nurse; OT, overtime; F, float (use of float or nonpermanent staff).

*References can be found on pages 621–622.

Volume 44, No. 10, October 2018 617

studies.49–51,53,54

One study examined both skill mix and the

level of staffing on the risk of MRSA infections and found

both variables to be significant predictors.51

Nurse Staffing and an Unspecified HAI Type

Table 4 describes studies that examined nurse staffing and

an unspecified HAI type. These studies either did not provide

information on the specific HAI evaluated or grouped dif-

ferent HAI types in one analysis.There were 8 studies

identified in this category. Two studies also assessed physi-

cian staffing in addition to nurse staffing.55,56

Most researchers

undertook data analysis at the patient level (n = 6; 75.0%),

conducted their studies in an ICU (n = 6; 75.0%), and mea-

sured the levelof nurse staffing (n = 7;87.5%).All

investigators found a significant association between the nurse

staffing variable measured (level55,57–62

and overtime56

) and

risk of HAI acquisition.

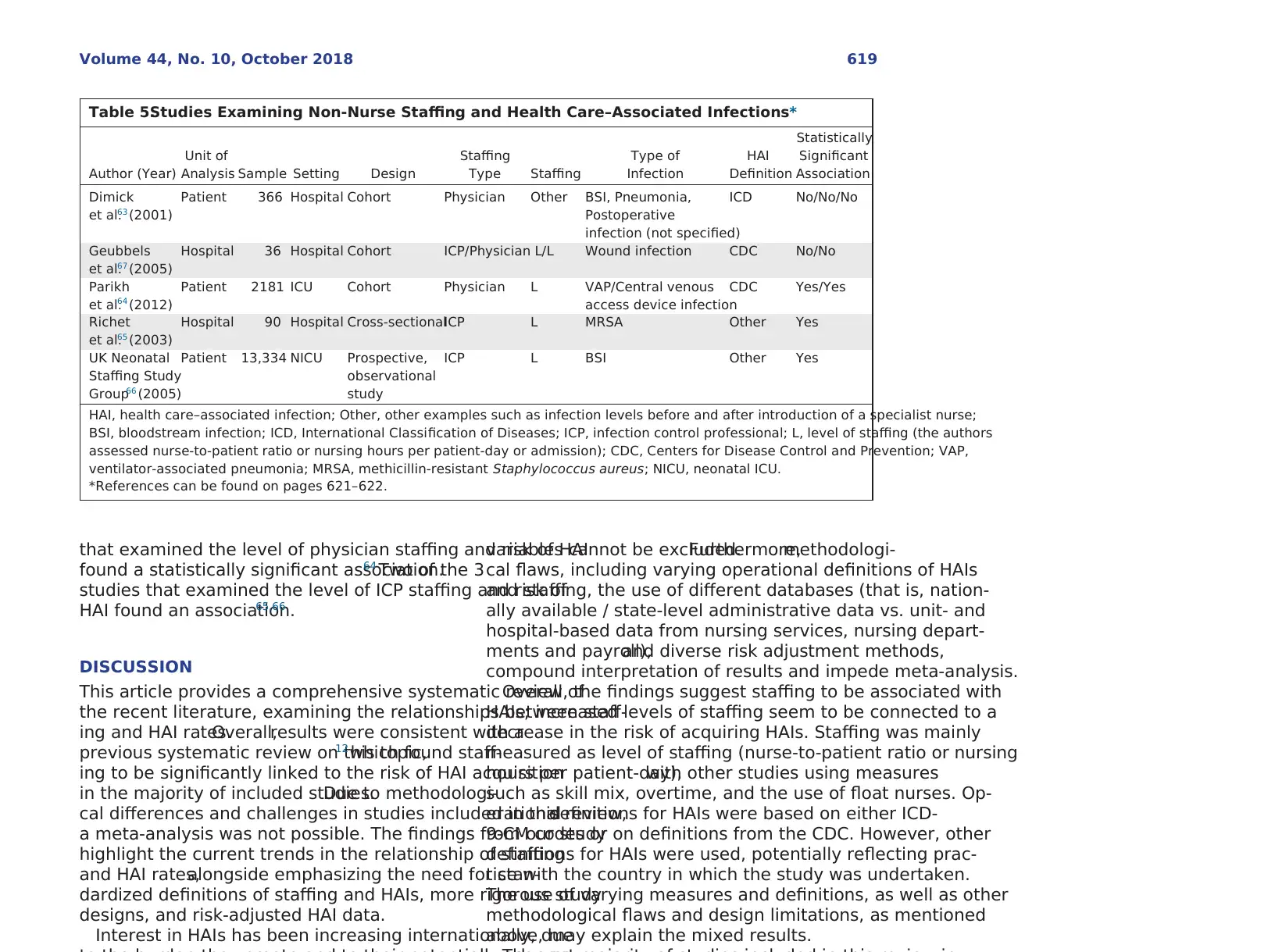

Non-Nurse Staffing and HAI

An overview of the 5 studies that examined non-nurse staff-

ing and HAI is presented in Table 5. The non-nurse staffing

types evaluated in these studies were ICU physicians63,64

and

infection controlprofessionals (ICPs).65,66One study in-

cluded both physicians and ICPs.67 Only 1 of the 3 studies

Table 3.Studies Examining Nurse Staffing and Organism-Specific Health Care–Associated Infections*

Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design Organism

HAI

Definition Staffing

Statistically

Significant

Association

Dancer

et al.49 (2006)

Patient 174 ICU Retrospective

analysis

MRSA Other L No

Dorsey

et al.53 (2000)

Patient 52 ICU Cohort Enterobacter cloacae

and Serratia marcescens

Other L Yes

Grundmann

et al.50 (2002)

Patient 331 ICU Cohort MRSA Other L Yes

Kong et al.52

(2012)

Patient 61 ICU Cohort MRSA Other L No

Manojlovich

et al.51 (2011)

Unit 26 Adult medical

and surgical units

Cohort MRSA Other L/SM Yes/Yes

Stegenga

et al.54 (2002)

Patient 2,929 General

pediatrics ward

Retrospective

descriptive

Viral gastrointestinal

infection

CDC L Yes

HAI, health care–associated infection; Other, other examples such as infection levels before and after introduction of a specialist nurse;

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; L, level of staffing (the authors assessed nurse-to-patient ratio or nursing hours per

patient-day or admission); SM, skill mix; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

*References can be found on pages 621–622.

Table 4.Studies Examining Nurse Staffing and Health Care–Associated Infections (Unspecified Infection Type)*†

Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design

HAI

Definition Staffing

Statistically

Significant

Association

Andersen et al.55 (2009)‡ Patient 57,360 Hospital Point prevalence CDC L Yes

618 Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac, et al HospitalStaffing and Risk of Infection

One study examined both skill mix and the

level of staffing on the risk of MRSA infections and found

both variables to be significant predictors.51

Nurse Staffing and an Unspecified HAI Type

Table 4 describes studies that examined nurse staffing and

an unspecified HAI type. These studies either did not provide

information on the specific HAI evaluated or grouped dif-

ferent HAI types in one analysis.There were 8 studies

identified in this category. Two studies also assessed physi-

cian staffing in addition to nurse staffing.55,56

Most researchers

undertook data analysis at the patient level (n = 6; 75.0%),

conducted their studies in an ICU (n = 6; 75.0%), and mea-

sured the levelof nurse staffing (n = 7;87.5%).All

investigators found a significant association between the nurse

staffing variable measured (level55,57–62

and overtime56

) and

risk of HAI acquisition.

Non-Nurse Staffing and HAI

An overview of the 5 studies that examined non-nurse staff-

ing and HAI is presented in Table 5. The non-nurse staffing

types evaluated in these studies were ICU physicians63,64

and

infection controlprofessionals (ICPs).65,66One study in-

cluded both physicians and ICPs.67 Only 1 of the 3 studies

Table 3.Studies Examining Nurse Staffing and Organism-Specific Health Care–Associated Infections*

Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design Organism

HAI

Definition Staffing

Statistically

Significant

Association

Dancer

et al.49 (2006)

Patient 174 ICU Retrospective

analysis

MRSA Other L No

Dorsey

et al.53 (2000)

Patient 52 ICU Cohort Enterobacter cloacae

and Serratia marcescens

Other L Yes

Grundmann

et al.50 (2002)

Patient 331 ICU Cohort MRSA Other L Yes

Kong et al.52

(2012)

Patient 61 ICU Cohort MRSA Other L No

Manojlovich

et al.51 (2011)

Unit 26 Adult medical

and surgical units

Cohort MRSA Other L/SM Yes/Yes

Stegenga

et al.54 (2002)

Patient 2,929 General

pediatrics ward

Retrospective

descriptive

Viral gastrointestinal

infection

CDC L Yes

HAI, health care–associated infection; Other, other examples such as infection levels before and after introduction of a specialist nurse;

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; L, level of staffing (the authors assessed nurse-to-patient ratio or nursing hours per

patient-day or admission); SM, skill mix; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

*References can be found on pages 621–622.

Table 4.Studies Examining Nurse Staffing and Health Care–Associated Infections (Unspecified Infection Type)*†

Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design

HAI

Definition Staffing

Statistically

Significant

Association

Andersen et al.55 (2009)‡ Patient 57,360 Hospital Point prevalence CDC L Yes

618 Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac, et al HospitalStaffing and Risk of Infection

that examined the level of physician staffing and risk of HAI

found a statistically significant association.64 Two of the 3

studies that examined the level of ICP staffing and risk of

HAI found an association.65,66

DISCUSSION

This article provides a comprehensive systematic review of

the recent literature, examining the relationships between staff-

ing and HAI rates.Overall,results were consistent with a

previous systematic review on this topic,12which found staff-

ing to be significantly linked to the risk of HAI acquisition

in the majority of included studies.Due to methodologi-

cal differences and challenges in studies included in this review,

a meta-analysis was not possible. The findings from our study

highlight the current trends in the relationship of staffing

and HAI rates,alongside emphasizing the need for stan-

dardized definitions of staffing and HAIs, more rigorous study

designs, and risk-adjusted HAI data.

Interest in HAIs has been increasing internationally, due

variables cannot be excluded.Furthermore,methodologi-

cal flaws, including varying operational definitions of HAIs

and staffing, the use of different databases (that is, nation-

ally available / state-level administrative data vs. unit- and

hospital-based data from nursing services, nursing depart-

ments and payroll),and diverse risk adjustment methods,

compound interpretation of results and impede meta-analysis.

Overall, the findings suggest staffing to be associated with

HAIs; increased levels of staffing seem to be connected to a

decrease in the risk of acquiring HAIs. Staffing was mainly

measured as level of staffing (nurse-to-patient ratio or nursing

hours per patient-day),with other studies using measures

such as skill mix, overtime, and the use of float nurses. Op-

erationaldefinitions for HAIs were based on either ICD-

9-CM codes or on definitions from the CDC. However, other

definitions for HAIs were used, potentially reflecting prac-

tice with the country in which the study was undertaken.

The use of varying measures and definitions, as well as other

methodological flaws and design limitations, as mentioned

above, may explain the mixed results.

Table 5.Studies Examining Non-Nurse Staffing and Health Care–Associated Infections*

Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design

Staffing

Type Staffing

Type of

Infection

HAI

Definition

Statistically

Significant

Association

Dimick

et al.63 (2001)

Patient 366 Hospital Cohort Physician Other BSI, Pneumonia,

Postoperative

infection (not specified)

ICD No/No/No

Geubbels

et al.67 (2005)

Hospital 36 Hospital Cohort ICP/Physician L/L Wound infection CDC No/No

Parikh

et al.64 (2012)

Patient 2181 ICU Cohort Physician L VAP/Central venous

access device infection

CDC Yes/Yes

Richet

et al.65 (2003)

Hospital 90 Hospital Cross-sectionalICP L MRSA Other Yes

UK Neonatal

Staffing Study

Group66 (2005)

Patient 13,334 NICU Prospective,

observational

study

ICP L BSI Other Yes

HAI, health care–associated infection; Other, other examples such as infection levels before and after introduction of a specialist nurse;

BSI, bloodstream infection; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; ICP, infection control professional; L, level of staffing (the authors

assessed nurse-to-patient ratio or nursing hours per patient-day or admission); CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; VAP,

ventilator-associated pneumonia; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NICU, neonatal ICU.

*References can be found on pages 621–622.

Volume 44, No. 10, October 2018 619

found a statistically significant association.64 Two of the 3

studies that examined the level of ICP staffing and risk of

HAI found an association.65,66

DISCUSSION

This article provides a comprehensive systematic review of

the recent literature, examining the relationships between staff-

ing and HAI rates.Overall,results were consistent with a

previous systematic review on this topic,12which found staff-

ing to be significantly linked to the risk of HAI acquisition

in the majority of included studies.Due to methodologi-

cal differences and challenges in studies included in this review,

a meta-analysis was not possible. The findings from our study

highlight the current trends in the relationship of staffing

and HAI rates,alongside emphasizing the need for stan-

dardized definitions of staffing and HAIs, more rigorous study

designs, and risk-adjusted HAI data.

Interest in HAIs has been increasing internationally, due

variables cannot be excluded.Furthermore,methodologi-

cal flaws, including varying operational definitions of HAIs

and staffing, the use of different databases (that is, nation-

ally available / state-level administrative data vs. unit- and

hospital-based data from nursing services, nursing depart-

ments and payroll),and diverse risk adjustment methods,

compound interpretation of results and impede meta-analysis.

Overall, the findings suggest staffing to be associated with

HAIs; increased levels of staffing seem to be connected to a

decrease in the risk of acquiring HAIs. Staffing was mainly

measured as level of staffing (nurse-to-patient ratio or nursing

hours per patient-day),with other studies using measures

such as skill mix, overtime, and the use of float nurses. Op-

erationaldefinitions for HAIs were based on either ICD-

9-CM codes or on definitions from the CDC. However, other

definitions for HAIs were used, potentially reflecting prac-

tice with the country in which the study was undertaken.

The use of varying measures and definitions, as well as other

methodological flaws and design limitations, as mentioned

above, may explain the mixed results.

Table 5.Studies Examining Non-Nurse Staffing and Health Care–Associated Infections*

Author (Year)

Unit of

Analysis Sample Setting Design

Staffing

Type Staffing

Type of

Infection

HAI

Definition

Statistically

Significant

Association

Dimick

et al.63 (2001)

Patient 366 Hospital Cohort Physician Other BSI, Pneumonia,

Postoperative

infection (not specified)

ICD No/No/No

Geubbels

et al.67 (2005)

Hospital 36 Hospital Cohort ICP/Physician L/L Wound infection CDC No/No

Parikh

et al.64 (2012)

Patient 2181 ICU Cohort Physician L VAP/Central venous

access device infection

CDC Yes/Yes

Richet

et al.65 (2003)

Hospital 90 Hospital Cross-sectionalICP L MRSA Other Yes

UK Neonatal

Staffing Study

Group66 (2005)

Patient 13,334 NICU Prospective,

observational

study

ICP L BSI Other Yes

HAI, health care–associated infection; Other, other examples such as infection levels before and after introduction of a specialist nurse;

BSI, bloodstream infection; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; ICP, infection control professional; L, level of staffing (the authors

assessed nurse-to-patient ratio or nursing hours per patient-day or admission); CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; VAP,

ventilator-associated pneumonia; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NICU, neonatal ICU.

*References can be found on pages 621–622.

Volume 44, No. 10, October 2018 619

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

are consistent with a previous review that also did not iden-

tify a statistically significant link between physician staffing

and HAIs.12 If these results are to be taken at face value, one

explanation may be that nurses constitute the largest pro-

portion of the health care workforce and have considerable

patient contact,11 thus providing an opportunity for in-

creased risk of organism transmission. As such, nurses have

the unique opportunity to directly reduce HAIs through rec-

ognizing and applying evidence-based procedures to prevent

HAIs among patients and protecting the health of the staff.4

In studies that examine the association between nurse staff-

ing and the risk of HAIs, a differentiation between permanent

nurse staffing and nonpermanent (temporary or float) staff-

ing is often made. Consistent with previous findings,12 the

majority of studies in our review suggested that the use of

permanent nurse staff was connected to a decrease in risk

of HAI acquisition.Conversely,the use of nonpermanent

nurse staff was linked to an increase in HAI risk. However,

evidence on the effects of using nonpermanent staff is scarce,

with our study identifying only three studies exploring this

association.5,20,39

To explain this result, it is plausible that non-

permanent nurse staff are less familiar with ward routine and

infection prevention strategies, may lack specific training, and

may not have the same levelof communication with co-

workers due to the inability to form established relationships.12

The importance of clear, interdisciplinary communication

and collaboration among health care professionals has been

highlighted by severalstudies,68–70with poor communica-

tion being named as one of the most common causes for

medical errors (that is, HAIs).68,69

Our review identified a lack of studies exploring the re-

lationship of specialized staff, including ICPs. The CDC’s

Study on the Efficacy ofNosocomialInfection Control

(SENIC), which suggested an adequate staffing ratio of ICPs

to patients,was published more than four decades ago.71

Given the high interest in HAIs and the number of studies

examining staffing and HAIs published in the last decade,

this scarceness of evidence is problematic; however, the chal-

lenges in undertaking a study such as the SENIC Project

cannot be understated. Only three studies included in our

review examined associations between ICPs and HAIs, and

only one study examined the effect of a specialist nurse on

care as the “problem of many hands.”72 Practicalapplica-

tions of this problem have been demonstrated through the

introduction of checklists to improve different groups of health

care professionals’ compliance with infection prevention.73

Future research is needed to establish a body of evidence to

support the tentative link between specialized nurse staff-

ing and ICPs and HAI rates.

Our review has limitations. Non–peer reviewed literature,

reviews, editorials, and commentaries or policy statements

and articles were excluded to maintain rigour and consistency

of the study. Publications in a language other than English

were also excluded. As such, evidence from such research was

not included.Further,no meta-analysis,and therefore as-

sessment of publication bias,was undertaken due to the

methodological limitations of the included studies. A further

challenge in exploring this topic is understanding a hospital’s

investment areas such as infrastructure,personnel,and

activities aimed at promoting quality. These are potential con-

founders that are not easily controlled or quantified,as

evidenced by the risk of bias assessment. With the trend of

shorter lengths of stay,patients have increased acuity and

may need a higher level of care; however, in this review we

were not able to examine staffing ratios adjusted for patient

acuity.74

CONCLUSION

Despite the data being observational, there is a growing and

updated evidence base demonstrating the relationship between

staffing characteristics and HAIs. The findings support ad-

vocacy for effective use of staffing resources and will inform

health care managers and professional organizations on future

changes to hospital staffing, as they relate to infection pre-

vention. Considerable variability in the study design, methods,

and definitions used to examine staffing and the risk of HAIs

exist in the literature. This highlights the need to move to

uniform operational definitions of staffing and HAIs in future

studies that explore this area.

Funding.This project was supported by an externalcompetitive grant

(Covidien)and scholarship awarded by Avondale College of Higher Ed-

ucation. Funders played no role in any element of this research.

Conflicts of Interest. One of the authors [P.W.S.]was a lead author on

620 Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac, et al HospitalStaffing and Risk of Infection

tify a statistically significant link between physician staffing

and HAIs.12 If these results are to be taken at face value, one

explanation may be that nurses constitute the largest pro-

portion of the health care workforce and have considerable

patient contact,11 thus providing an opportunity for in-

creased risk of organism transmission. As such, nurses have

the unique opportunity to directly reduce HAIs through rec-

ognizing and applying evidence-based procedures to prevent

HAIs among patients and protecting the health of the staff.4

In studies that examine the association between nurse staff-

ing and the risk of HAIs, a differentiation between permanent

nurse staffing and nonpermanent (temporary or float) staff-

ing is often made. Consistent with previous findings,12 the

majority of studies in our review suggested that the use of

permanent nurse staff was connected to a decrease in risk

of HAI acquisition.Conversely,the use of nonpermanent

nurse staff was linked to an increase in HAI risk. However,

evidence on the effects of using nonpermanent staff is scarce,

with our study identifying only three studies exploring this

association.5,20,39

To explain this result, it is plausible that non-

permanent nurse staff are less familiar with ward routine and

infection prevention strategies, may lack specific training, and

may not have the same levelof communication with co-

workers due to the inability to form established relationships.12

The importance of clear, interdisciplinary communication

and collaboration among health care professionals has been

highlighted by severalstudies,68–70with poor communica-

tion being named as one of the most common causes for

medical errors (that is, HAIs).68,69

Our review identified a lack of studies exploring the re-

lationship of specialized staff, including ICPs. The CDC’s

Study on the Efficacy ofNosocomialInfection Control

(SENIC), which suggested an adequate staffing ratio of ICPs

to patients,was published more than four decades ago.71

Given the high interest in HAIs and the number of studies

examining staffing and HAIs published in the last decade,

this scarceness of evidence is problematic; however, the chal-

lenges in undertaking a study such as the SENIC Project

cannot be understated. Only three studies included in our

review examined associations between ICPs and HAIs, and

only one study examined the effect of a specialist nurse on

care as the “problem of many hands.”72 Practicalapplica-

tions of this problem have been demonstrated through the

introduction of checklists to improve different groups of health

care professionals’ compliance with infection prevention.73

Future research is needed to establish a body of evidence to

support the tentative link between specialized nurse staff-

ing and ICPs and HAI rates.

Our review has limitations. Non–peer reviewed literature,

reviews, editorials, and commentaries or policy statements

and articles were excluded to maintain rigour and consistency

of the study. Publications in a language other than English

were also excluded. As such, evidence from such research was

not included.Further,no meta-analysis,and therefore as-

sessment of publication bias,was undertaken due to the

methodological limitations of the included studies. A further

challenge in exploring this topic is understanding a hospital’s

investment areas such as infrastructure,personnel,and

activities aimed at promoting quality. These are potential con-

founders that are not easily controlled or quantified,as

evidenced by the risk of bias assessment. With the trend of

shorter lengths of stay,patients have increased acuity and

may need a higher level of care; however, in this review we

were not able to examine staffing ratios adjusted for patient

acuity.74

CONCLUSION

Despite the data being observational, there is a growing and

updated evidence base demonstrating the relationship between

staffing characteristics and HAIs. The findings support ad-

vocacy for effective use of staffing resources and will inform

health care managers and professional organizations on future

changes to hospital staffing, as they relate to infection pre-

vention. Considerable variability in the study design, methods,

and definitions used to examine staffing and the risk of HAIs

exist in the literature. This highlights the need to move to

uniform operational definitions of staffing and HAIs in future

studies that explore this area.

Funding.This project was supported by an externalcompetitive grant

(Covidien)and scholarship awarded by Avondale College of Higher Ed-

ucation. Funders played no role in any element of this research.

Conflicts of Interest. One of the authors [P.W.S.]was a lead author on

620 Brett G. Mitchell, PhD, MAdvPrac, et al HospitalStaffing and Risk of Infection

ONLINE-ONLY CONTENT

See the online version of this article for Appendix 1 Char-

acteristics of Studies Included in the Systematic Review.

Appendix 2 Risk of Bias Assessment in the Studies in the

Systematic Review.

REFERENCES

1. Allegranzi B, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated

infection in developing countries:systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011 Jan 15;377:228–241.

2. Magill SS, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health

care–associated infections.N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar

27;370:1198–1208.

3. Cassini A, et al. Burden of six healthcare-associated infections

on European population health: estimating incidence-based

disability-adjusted life years through a population

prevalence-based modelling study.PLoS Med. 2016 Oct

18;13:e1002150.

4. Collins AS. Preventing health care–associated infections. In:

Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-

Based Handbook for Nurses.Rockville,MD: Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality,2008 Accessed Apr 26,

2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2683/.

5. Alonso-Echanove J, et al. Effect of nurse staffing and

antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters on the

risk for bloodstream infections in intensive care units. Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:916–925.

6. Jackson M, et al. Nurse staffing and health care–associated

infections: proceedings from a working group meeting. Am

J Infect Control. 2002;30:199–206.

7. Needleman J, et al. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of

care in hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002 May 30;346:1715–1722.

8. Aiken LH,et al.Educationallevels of hospitalnurses and

surgical patient mortality. JAMA. 2003 Sep 24;290:1617–1623.

9. Hugonnet S, et al. Nursing resources: a major determinant

of nosocomial infection? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17:329–

333.

10. Mark BA, Harless DW.Nurse staffing and post-surgical

complications using the present on admission indicator. Res

Nurs Health. 2010;33:35–47.

11. Shang J, Stone P, Larson E. Studies on nurse staffing and

health care–associated infection: methodologic challenges

and potential solutions. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:581–588.

12. Stone PW, et al. Hospital staffing and health care–associated

infections: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect

Dis. 2008 Oct 1;47:937–944.

13. Dettenkofer M, et al. Infection control—a European research

18. Fraher MH,et al.Cost-effectiveness of employing a total

parenteral nutrition surveillance nurse for the prevention of

catheter-related bloodstream infections.J Hosp Infect.

2009;73:129–134.

19. Pronovost PJ, et al. Intensive care unit nurse staffing and the

risk for complications after abdominal aortic surgery. Eff Clin

Pract. 2001;4:199–206.

20. Robert J, et al. The influence ofthe composition ofthe

nursing staff on primary bloodstream infection rates in a

surgical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.

2000;21:12–17.

21. Tucker J, UK Neonatal Staffing Study Group. Patient volume,

staffing, and workload in relation to risk-adjusted outcomes

in a random stratified sample of UK neonatal intensive care

units: a prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359:99–

107.

22. Whitman GR, et al. The impact of staffing on patient

outcomes across specialty units. J Nurs Adm. 2002;32:633–

639.

23. Sujijantararat R, Booth RZ, Davis LL. Nosocomial urinary tract

infection: nursing-sensitive quality indicator in a Thai hospital.

J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20:134–139.

24. Hugonnet S, Uçkay I, Pittet D. Staffing level: a determinant

of late-onset ventilator-associated pneumonia.Crit Care.

2007;11(4):R80.

25. Berney B,Needleman J. Impact ofnursing overtime on

nurse-sensitive patient outcomes in New York hospitals,

1995–2000. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2006;7:87–100.

26. Cimiotti JP, et al. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care–

associated infection. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:486–490.

Erratum in: Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:680.

27. Kelly D, et al. The critical care work environment and nurse-

reported health care–associated infections. Am J Crit Care.

2013;22:482–488.

28. Kovner C,et al. Nurse staffing and postsurgicaladverse

events: an analysis of administrative data from a sample of

U.S. hospitals,1990–1996.Health Serv Res.2002;37:611–

629.

29. Mark BA, Harless DW,Berman WF.Nurse staffing and

adverse events in hospitalized children.Policy Polit Nurs

Pract. 2007;8:83–92.

30. Mark BA, et al. A longitudinal examination ofhospital

registered nurse staffing and quality of care. Health Serv Res.

2004;39:279–300. Erratum in: Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1629.

31. Needleman J, et al. Measuring hospital quality: can Medicare

data substitute for all-payer data? Health Serv Res.

2003;38:1487–1508.

32. Twigg D, et al. The impact of the nursing hours per patient

day (NHPPD) staffing method on patient outcomes:

a retrospective analysis of patient and staffing data. Int J Nurs

Volume 44, No. 10, October 2018 621

See the online version of this article for Appendix 1 Char-

acteristics of Studies Included in the Systematic Review.

Appendix 2 Risk of Bias Assessment in the Studies in the

Systematic Review.

REFERENCES

1. Allegranzi B, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated

infection in developing countries:systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011 Jan 15;377:228–241.

2. Magill SS, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health

care–associated infections.N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar

27;370:1198–1208.

3. Cassini A, et al. Burden of six healthcare-associated infections

on European population health: estimating incidence-based

disability-adjusted life years through a population

prevalence-based modelling study.PLoS Med. 2016 Oct

18;13:e1002150.

4. Collins AS. Preventing health care–associated infections. In:

Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-

Based Handbook for Nurses.Rockville,MD: Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality,2008 Accessed Apr 26,

2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2683/.

5. Alonso-Echanove J, et al. Effect of nurse staffing and

antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters on the

risk for bloodstream infections in intensive care units. Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:916–925.

6. Jackson M, et al. Nurse staffing and health care–associated

infections: proceedings from a working group meeting. Am

J Infect Control. 2002;30:199–206.

7. Needleman J, et al. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of

care in hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002 May 30;346:1715–1722.

8. Aiken LH,et al.Educationallevels of hospitalnurses and

surgical patient mortality. JAMA. 2003 Sep 24;290:1617–1623.

9. Hugonnet S, et al. Nursing resources: a major determinant

of nosocomial infection? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17:329–

333.

10. Mark BA, Harless DW.Nurse staffing and post-surgical

complications using the present on admission indicator. Res

Nurs Health. 2010;33:35–47.

11. Shang J, Stone P, Larson E. Studies on nurse staffing and

health care–associated infection: methodologic challenges

and potential solutions. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:581–588.

12. Stone PW, et al. Hospital staffing and health care–associated

infections: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect

Dis. 2008 Oct 1;47:937–944.

13. Dettenkofer M, et al. Infection control—a European research

18. Fraher MH,et al.Cost-effectiveness of employing a total

parenteral nutrition surveillance nurse for the prevention of

catheter-related bloodstream infections.J Hosp Infect.

2009;73:129–134.

19. Pronovost PJ, et al. Intensive care unit nurse staffing and the

risk for complications after abdominal aortic surgery. Eff Clin

Pract. 2001;4:199–206.

20. Robert J, et al. The influence ofthe composition ofthe

nursing staff on primary bloodstream infection rates in a

surgical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.

2000;21:12–17.

21. Tucker J, UK Neonatal Staffing Study Group. Patient volume,

staffing, and workload in relation to risk-adjusted outcomes

in a random stratified sample of UK neonatal intensive care

units: a prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359:99–

107.

22. Whitman GR, et al. The impact of staffing on patient

outcomes across specialty units. J Nurs Adm. 2002;32:633–

639.

23. Sujijantararat R, Booth RZ, Davis LL. Nosocomial urinary tract

infection: nursing-sensitive quality indicator in a Thai hospital.

J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20:134–139.

24. Hugonnet S, Uçkay I, Pittet D. Staffing level: a determinant

of late-onset ventilator-associated pneumonia.Crit Care.

2007;11(4):R80.

25. Berney B,Needleman J. Impact ofnursing overtime on

nurse-sensitive patient outcomes in New York hospitals,

1995–2000. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2006;7:87–100.

26. Cimiotti JP, et al. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care–

associated infection. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:486–490.

Erratum in: Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:680.

27. Kelly D, et al. The critical care work environment and nurse-

reported health care–associated infections. Am J Crit Care.

2013;22:482–488.

28. Kovner C,et al. Nurse staffing and postsurgicaladverse

events: an analysis of administrative data from a sample of

U.S. hospitals,1990–1996.Health Serv Res.2002;37:611–

629.

29. Mark BA, Harless DW,Berman WF.Nurse staffing and

adverse events in hospitalized children.Policy Polit Nurs

Pract. 2007;8:83–92.

30. Mark BA, et al. A longitudinal examination ofhospital

registered nurse staffing and quality of care. Health Serv Res.

2004;39:279–300. Erratum in: Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1629.

31. Needleman J, et al. Measuring hospital quality: can Medicare

data substitute for all-payer data? Health Serv Res.

2003;38:1487–1508.

32. Twigg D, et al. The impact of the nursing hours per patient

day (NHPPD) staffing method on patient outcomes:

a retrospective analysis of patient and staffing data. Int J Nurs

Volume 44, No. 10, October 2018 621

38. Stone PW, et al. Nurse working conditions and patient safety

outcomes. Med Care. 2007;45:571–578.

39. Stratton KM.Pediatric nurse staffing and quality ofcare

in the hospitalsetting.J Nurs Care Qual. 2008;23:105–

114.

40. Yang KP. Relationships between nurse staffing and patient

outcomes. J Nurs Res. 2003;11:149–158.

41. Schwab F, et al. Understaffing, overcrowding, inappropriate

nurse:ventilated patient ratio and nosocomialinfections:

which parameter is the best reflection of deficits? J Hosp

Infect. 2012;80:133–139.

42. Amaravadi RK, et al. ICU nurse-to-patient ratio is associated

with complications and resource use after esophagectomy.

Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1857–1862.

43. Barkell NP, Killinger KA, Schultz SD. The relationship between

nurse staffing models and patient outcomes: a descriptive

study. Outcomes Manag. 2002;6:27–33.

44. Dimick JB, et al. Effect of nurse-to-patient ratio in the

intensive care unit on pulmonary complications and resource

use after hepatectomy. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10:376–382.

45. Glance LG, et al. The association between nurse staffing and

hospital outcomes in injured patients. BMC Health Serv Res.

2012 Aug 9;12:247.

46. McGillis HallL, Doran D,Pink GH.Nurse staffing models,

nursing hours,and patient safety outcomes.J Nurs Adm.

2004;34:41–45.

47. Pappas S,et al.Risk-adjusted staffing to improve patient

value. Nurs Econ. 2015;33:73–78, 87.

48. Yang PH,et al. The impact ofdifferent nursing skillmix

models on patient outcomes in a respiratory care center.

Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9:227–233.

49. Dancer SJ, et al. MRSA acquisition in an intensive care unit.

Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:10–17.

50. Grundmann H,et al. Risk factors for the transmission of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an adult

intensive care unit: fitting a model to the data. J Infect Dis.

2002 Feb 15;185:481–488.

51. Manojlovich M, et al. Nurse dose: linking staffing variables

to adverse patient outcomes. Nurs Res. 2011;60:214–

220.

52. Kong F, et al. Do staffing and workload levels influence the

risk of new acquisitions of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus in a well-resourced intensive care unit? J Hosp Infect.

2012;80:331–339.

53. Dorsey G, et al. A heterogeneous outbreak of Enterobacter

cloacae and Serratia marcescens infections in a surgical

intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.

2000;21:465–469.

54. Stegenga J, Bell E, Matlow A. The role of nurse understaffing

in nosocomial viral gastrointestinal infections on a general

57. Daud-GallottiRM, et al.Nursing workload as a risk factor

for healthcare associated infections in ICU:a prospective

study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52342.

58. Halwani M, et al. Cross-transmission of nosocomial

pathogens in an adult intensive care unit: incidence and risk

factors. J Hosp Infect. 2006;63:39–46.

59. Maillet JM, et al. Comparison of intensive-care-unit-acquired

infections and their outcomes among patients over and

under 80 years of age. J Hosp Infect. 2014;87:152–158.

60. Rogowski JA, et al. Nurse staffing and NICU infection rates.

JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:444–450.

61. Hugonnet S, Chevrolet JC, Pittet D. The effect of workload

on infection risk in critically illpatients.Crit Care Med.

2007;35:76–81.

62. Hugonnet S, Villaveces A, Pittet D. Nurse staffing level and

nosocomialinfections:empiricalevaluation ofthe case-

crossover and case-time-control designs. Am J Epidemiol.

2007 Jun 1;165:1321–1327.

63. Dimick JB, et al. Intensive care unit physician staffing is

associated with decreased length of stay, hospital cost, and

complications after esophagealresection.Crit Care Med.

2001;29:753–758.

64. Parikh A, et al. Quality improvement and cost savings after

implementation of the Leapfrog intensive care unit physician

staffing standard at a community teaching hospital. Crit Care

Med. 2012;40:2754–2759.

65. Richet HM, et al. Are there regional variations in the

diagnosis,surveillance,and controlof methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus? Infect ControlHosp Epidemiol.

2003;24:334–341.

66. UK NeonatalStaffing Study Group.Relationship between

probable nosocomialbacteraemia and organisationaland

structuralfactors in UK neonatalintensive care units. Qual

Saf Health Care. 2005;14:264–269.

67. Geubbels EL, et al. Hospital-related determinants for

surgical-site infection following hip arthroplasty.Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:435–441.

68. Tschannen D, et al. Implications of nurse-physician relations:

report of a successful intervention. Nurs Econ. 2011;29:127–

135.

69. Siegele P. Enhancing outcomes in a surgical intensive care

unit by implementing daily goals tools.Crit Care Nurse.

2009;29:58–69.

70. Lancaster G,et al. Interdisciplinary communication and

collaboration among physicians,nurses,and unlicensed

assistive personnel. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47:275–284.