Prevalence and Causes of Vision Loss in Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/14

|10

|10105

|451

AI Summary

The National Eye Health Survey conducted a nationwide, cross-sectional, population-based survey to determine the prevalence and causes of vision loss in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The study found that vision loss is more prevalent in Indigenous Australians than in non-Indigenous Australians, with uncorrected refractive error and cataract being the leading causes. Risk factors for vision loss were also identified.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

The Prevalence and Causes of Vision Loss in

Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians

The NationalEye Health Survey

Joshua Foreman, BSc (Hons),1,2 Jing Xie, PhD,1 Stuart Keel, PhD,1 Peter van Wijngaarden, FRANZCO,1,2

SukhpalSingh Sandhu, FRANZCO,1,2 Ghee Soon Ang, FRANZCO,1 Jennifer Fan Gaskin, FRANZCO,1

Jonathan Crowston, FRANZCO,1,2 Rupert Bourne, FRCOphth,3 Hugh R. Taylor, AC,4 Mohamed Dirani, PhD1,2

Purpose: To conduct a nationwide survey on the prevalence and causes of vision loss in Indigenous and

non-Indigenous Australians.

Design: Nationwide, cross-sectional, population-based survey.

Participants: Indigenous Australians aged 40 years or older and non-Indigenous Australians aged 50 year

and older.

Methods: Multistage random-clustersampling was used to select3098 non-Indigenous Australians and

1738 Indigenous Australians from 30 sites across 5 remoteness strata (response rate of71.5%).Sociodemo-

graphic and health data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire.Trained examiners

conducted standardized eye examinations,including visualacuity,perimetry,slit-lamp examination, intraocular

pressure,and fundus photography.The prevalence and main causes ofbilateralpresenting vision loss (visual

acuity <6/12 in the better eye)were determined, and risk factors were identified.

Main Outcome Measures: Prevalence and main causes of vision loss.

Results: The overallprevalence of vision loss in Australia was 6.6% (95% confidence interval[CI], 5.4e7.8).

The prevalence ofvision loss was 11.2% (95% CI,9.5e13.1)in Indigenous Australians and 6.5% (95% CI,

5.3e7.9) in non-Indigenous Australians. Vision loss was 2.8 times more prevalent in Indigenous Australians th

in non-Indigenous Australians after age and gender adjustment (17.7%, 95% CI, 14.5 e21.0 vs. 6.4%, 95% CI

5.2e7.6, P < 0.001). In non-Indigenous Australians, the leading causes of vision loss were uncorrected refrac

error (61.3%),cataract (13.2%),and age-related macular degeneration (10.3%).In Indigenous Australians,the

leading causes of vision loss were uncorrected refractive error (60.8%), cataract (20.1%), and diabetic retino

(5.2%). In non-Indigenous Australians, increasing age (odds ratio [OR], 1.72 per decade)and having not had an

eye examination within the pastyear (OR, 1.61)were risk factors forvision loss.Risk factors in Indigenous

Australians included older age (OR,1.61 per decade),remoteness (OR,2.02),gender (OR,0.60 for men),and

diabetes in combination with never having had an eye examination (OR, 14.47).

Conclusions: Vision loss is more prevalentin Indigenous Australians than in non-Indigenous Australians,

highlighting that improvements in eye healthcare in Indigenous communities are required. The leading caus

vision loss were uncorrected refractive errorand cataract,which are readily treatable.Other countries with

Indigenous communities may benefitfrom conducting similarsurveys of Indigenous and non-Indigenous

populations. Ophthalmology 2017;- :1e10 ª 2017 by the American Academy of Ophthalmology

Globally,approximately 223million peopleexperience

vision loss,1 in whom 80% of cases are avoidable through

early detection,prevention,and treatment.2 The feasibility

of reducing the burden of vision loss prompted the World

Health Assemblyto endorse“UniversalEye Health:

A Global Action Plan 2014e2019”(theGlobalAction

Plan)in 2013,which aimed to reduce the prevalence of

avoidable blindnessby 25% before the year2020.3 The

World Health Assembly emphasizedthe need for

population-based survey data on the prevalence and causes

of vision loss to inform resourceallocationfor eye

healthcare services to achieve the objectives of the Glob

Action Plan.3

Less than 20% of countries have conducted nationwide

surveys on the prevalence and causes ofvision loss,and

existing studies vary in terms of methodologicalrigor.2 In

this article,we contend thatthe methodsused in most

surveysto date are limited in theirability to provide a

sufficientlydetailedmap of a nation’seye health,

particularly in countrieswith disadvantaged Indigenous

groups.The definition ofindigeneity iscontentiousand

varies considerably;however, the United Nations

1ª 2017 by the American Academy of Ophthalmology

Published by Elsevier Inc.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.06.001

ISSN 0161-6420/17

Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians

The NationalEye Health Survey

Joshua Foreman, BSc (Hons),1,2 Jing Xie, PhD,1 Stuart Keel, PhD,1 Peter van Wijngaarden, FRANZCO,1,2

SukhpalSingh Sandhu, FRANZCO,1,2 Ghee Soon Ang, FRANZCO,1 Jennifer Fan Gaskin, FRANZCO,1

Jonathan Crowston, FRANZCO,1,2 Rupert Bourne, FRCOphth,3 Hugh R. Taylor, AC,4 Mohamed Dirani, PhD1,2

Purpose: To conduct a nationwide survey on the prevalence and causes of vision loss in Indigenous and

non-Indigenous Australians.

Design: Nationwide, cross-sectional, population-based survey.

Participants: Indigenous Australians aged 40 years or older and non-Indigenous Australians aged 50 year

and older.

Methods: Multistage random-clustersampling was used to select3098 non-Indigenous Australians and

1738 Indigenous Australians from 30 sites across 5 remoteness strata (response rate of71.5%).Sociodemo-

graphic and health data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire.Trained examiners

conducted standardized eye examinations,including visualacuity,perimetry,slit-lamp examination, intraocular

pressure,and fundus photography.The prevalence and main causes ofbilateralpresenting vision loss (visual

acuity <6/12 in the better eye)were determined, and risk factors were identified.

Main Outcome Measures: Prevalence and main causes of vision loss.

Results: The overallprevalence of vision loss in Australia was 6.6% (95% confidence interval[CI], 5.4e7.8).

The prevalence ofvision loss was 11.2% (95% CI,9.5e13.1)in Indigenous Australians and 6.5% (95% CI,

5.3e7.9) in non-Indigenous Australians. Vision loss was 2.8 times more prevalent in Indigenous Australians th

in non-Indigenous Australians after age and gender adjustment (17.7%, 95% CI, 14.5 e21.0 vs. 6.4%, 95% CI

5.2e7.6, P < 0.001). In non-Indigenous Australians, the leading causes of vision loss were uncorrected refrac

error (61.3%),cataract (13.2%),and age-related macular degeneration (10.3%).In Indigenous Australians,the

leading causes of vision loss were uncorrected refractive error (60.8%), cataract (20.1%), and diabetic retino

(5.2%). In non-Indigenous Australians, increasing age (odds ratio [OR], 1.72 per decade)and having not had an

eye examination within the pastyear (OR, 1.61)were risk factors forvision loss.Risk factors in Indigenous

Australians included older age (OR,1.61 per decade),remoteness (OR,2.02),gender (OR,0.60 for men),and

diabetes in combination with never having had an eye examination (OR, 14.47).

Conclusions: Vision loss is more prevalentin Indigenous Australians than in non-Indigenous Australians,

highlighting that improvements in eye healthcare in Indigenous communities are required. The leading caus

vision loss were uncorrected refractive errorand cataract,which are readily treatable.Other countries with

Indigenous communities may benefitfrom conducting similarsurveys of Indigenous and non-Indigenous

populations. Ophthalmology 2017;- :1e10 ª 2017 by the American Academy of Ophthalmology

Globally,approximately 223million peopleexperience

vision loss,1 in whom 80% of cases are avoidable through

early detection,prevention,and treatment.2 The feasibility

of reducing the burden of vision loss prompted the World

Health Assemblyto endorse“UniversalEye Health:

A Global Action Plan 2014e2019”(theGlobalAction

Plan)in 2013,which aimed to reduce the prevalence of

avoidable blindnessby 25% before the year2020.3 The

World Health Assembly emphasizedthe need for

population-based survey data on the prevalence and causes

of vision loss to inform resourceallocationfor eye

healthcare services to achieve the objectives of the Glob

Action Plan.3

Less than 20% of countries have conducted nationwide

surveys on the prevalence and causes ofvision loss,and

existing studies vary in terms of methodologicalrigor.2 In

this article,we contend thatthe methodsused in most

surveysto date are limited in theirability to provide a

sufficientlydetailedmap of a nation’seye health,

particularly in countrieswith disadvantaged Indigenous

groups.The definition ofindigeneity iscontentiousand

varies considerably;however, the United Nations

1ª 2017 by the American Academy of Ophthalmology

Published by Elsevier Inc.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.06.001

ISSN 0161-6420/17

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

PermanentForum on IndigenousIssuesloosely defines

Indigenous peoples on the basis ofthe following criteria:

(1) self-identification as Indigenous peoples by individuals

and acceptance as such by their community;(2) historical

continuity and land occupation before invasion and coloni-

zation; (3) strong links to territories including land and water

and related natural resources; (4) distinct social, economic, or

politicalsystems;(5) distinctlanguage,culture,religion,

ceremonies, and beliefs; (6) tendency to form nondominant

groups of society; (7) resolution to maintain and reproduce

ancestral environments and systems as distinct peoples and

communities; and (8) tendency to manage their own affairs

separate from centralized state authorities.4 There are 370

million Indigenouspeoplein 90 countries,and they

consistentlyexperiencesignificantly poorer health

outcomesthan theirnon-Indigenouscounterparts.5,6 This

gap is particularly pronounced in developed nations with

historically colonized Indigenous minorities,including the

United States,Canada,New Zealand,and Australia,where

Indigenous morbidity and mortality rates are higher than in

many developing nations.7 Considering thatvision loss is

more prevalentin disadvantaged communities,8 it follows

thatmany Indigenouspopulationsare likely to havea

higher burden of vision loss. Nationwide studies have been

conducted in regionsof Asia, Africa, and Europe with

Indigenous populations,but none have attempted to collect

samples from Indigenous groups.9e22 By assuming ethnic

homogeneity and neglecting to interrogate Indigenous com-

munities,these surveys may have insufficiently quantified

the burden of vision loss in some of their countries’ most

vulnerable groups.Consequently,they may have under-

estimatedthe prevalenceof vision loss and generated

datathat are insufficientto optimallyinform national

interventions.

With the exceptionof 2 surveys conductedin

Australia,23,24 all surveysinvestigatingIndigenouseye

health have been subnational and focused on isolated tribes

or communities with varying degrees of sampling bias,25e33

and mostdid not makerobustcomparisonswith non-

Indigenousgroups25,27,28,30,33

or collectcomprehensive

ophthalmic data.29,30Nevertheless,the majority ofthese

surveys, in conjunction with other research, have found that

Indigenous communities in Brazil,Ecuador,United States,

and Australia have high rates of vision loss24,34,35

and eye

disease,including trachoma,30,36cataract,25 pterygium,25,37

and diabetic retinopathy.24 Therefore,because Indigenous

peoples constitutemore than 5% of the global

population,7 identifyingthe prevalenceand causesof

vision lossin these groupsin conjunction with general

populationsis critical to inform nationaleye health

programsand to achievethe objectivesof the Global

Action Plan.

Australia requires national prevalence data on vision loss

to fulfill its obligations as a signatory to the Global Action

Plan.State-levelsurveys conducted in the early 1990s in

Victoria,38 New South Wales,39 and South Australia40 have

been thereferencestudiesin Australiauntil now. We

conducted a nationwide study,the NationalEye Health

Survey (NEHS),to determine the prevalence and causes

of vision loss in Australia.This survey has implemented a

novelapproach to stratifying its sampling frame according

to Indigenous status to produce reliable estimates ofthe

prevalence and causes ofvision loss in both Indigenous

and non-Indigenous populations.We presentthe findings

of the NEHS and propose thatourstratified study design

forms the basis for future prevalence studies in all countr

with Indigenous groups.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The sampling methodology ofthe NEHS has been described in

detail.41 In brief, the targetpopulationwas stratifiedinto

Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous Australians.In accor-

dance with GlobalAction Plan guidelines,the NEHS recruited

non-IndigenousAustraliansaged 50 yearsor older.3 However,

because Indigenous Australians have earlier onset and more ra

progression ofeye disease and diabetes,42 a youngerage of40

years orolderwas selected.On the basisof the mostreliable

previousestimatesof the prevalenceof vision loss in

Australia,24,43the required sample size was 2794 non-Indigenous

Australiansand 1368 IndigenousAustraliansresidingin 30

geographic areas.

Multistage random-cluster sampling was used to selectpartic-

ipants on the basis of data from the 2011 Australian Census.44 In

stage 1 of sampling,the Australian population was stratified into

5 remoteness strata:Major City,Inner Regional,Outer Regional,

Remote,and Very Remote.Probabilityproportionalto size

sampling was used to select12 MajorCity, 6 InnerRegional,

6 OuterRegional,4 Remote,and 2 Very Remote survey sites,

corresponding to the approximate population distribution in ea

stratum.In the secondstage,a smallerclustercontaining

approximately 100 eligible residents was randomly selected an

nominated asthe enumeration site.Becauseof a numberof

factorsincludinginsufficientpopulationnumbers,inaccurate

Census data,and high absentee rates,a systematic approach was

used to make adjustmentsto some sites,including the use of

backup sitesand sampling from contiguousgeographicareas.

The details of this approach have been published.41 Door-to-door

recruitmentwas conducteduntil approximately100 non-

Indigenousparticipantswere recruitedfrom each cluster.

Although door-to-doorrecruitmentwas used forthe majority of

participants,we consulted Aboriginalelders and localAboriginal

Health Servicesto ensurethatour recruitmentmethodswere

culturallyappropriate.In someinstances,directdoor-to-door

recruitmentwas deemed culturally inappropriate,and telephone

recruitmentfrom formalizedcommunitylists was usedas a

substitute.Householdrecruitment,includingdoor-to-doorand

telephonerecruitment,accountedfor approximately80% of

Indigenous recruitment.Alternative methods ofcontactincluded

concurrent Indigenous health clinics and word of mouth.

The protocol was approved by the Royal Victorian Eye and E

Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, as well as state-b

Indigenousethicsorganizations.This study wasconducted in

accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedures

The examination protocolof the NEHS hasbeen described in

detail.45 Participantexaminations were conducted in a totalof 61

testing venues thatincluded community centers,mobile clinics,

town halls, AboriginalCorporations,schools,and medical

clinics,all within 6 km ofeach recruitmentsite.Examinations

were conducted over13 monthsand 7 days,from March 11,

OphthalmologyVolume- , Number- , Month 2017

2

Indigenous peoples on the basis ofthe following criteria:

(1) self-identification as Indigenous peoples by individuals

and acceptance as such by their community;(2) historical

continuity and land occupation before invasion and coloni-

zation; (3) strong links to territories including land and water

and related natural resources; (4) distinct social, economic, or

politicalsystems;(5) distinctlanguage,culture,religion,

ceremonies, and beliefs; (6) tendency to form nondominant

groups of society; (7) resolution to maintain and reproduce

ancestral environments and systems as distinct peoples and

communities; and (8) tendency to manage their own affairs

separate from centralized state authorities.4 There are 370

million Indigenouspeoplein 90 countries,and they

consistentlyexperiencesignificantly poorer health

outcomesthan theirnon-Indigenouscounterparts.5,6 This

gap is particularly pronounced in developed nations with

historically colonized Indigenous minorities,including the

United States,Canada,New Zealand,and Australia,where

Indigenous morbidity and mortality rates are higher than in

many developing nations.7 Considering thatvision loss is

more prevalentin disadvantaged communities,8 it follows

thatmany Indigenouspopulationsare likely to havea

higher burden of vision loss. Nationwide studies have been

conducted in regionsof Asia, Africa, and Europe with

Indigenous populations,but none have attempted to collect

samples from Indigenous groups.9e22 By assuming ethnic

homogeneity and neglecting to interrogate Indigenous com-

munities,these surveys may have insufficiently quantified

the burden of vision loss in some of their countries’ most

vulnerable groups.Consequently,they may have under-

estimatedthe prevalenceof vision loss and generated

datathat are insufficientto optimallyinform national

interventions.

With the exceptionof 2 surveys conductedin

Australia,23,24 all surveysinvestigatingIndigenouseye

health have been subnational and focused on isolated tribes

or communities with varying degrees of sampling bias,25e33

and mostdid not makerobustcomparisonswith non-

Indigenousgroups25,27,28,30,33

or collectcomprehensive

ophthalmic data.29,30Nevertheless,the majority ofthese

surveys, in conjunction with other research, have found that

Indigenous communities in Brazil,Ecuador,United States,

and Australia have high rates of vision loss24,34,35

and eye

disease,including trachoma,30,36cataract,25 pterygium,25,37

and diabetic retinopathy.24 Therefore,because Indigenous

peoples constitutemore than 5% of the global

population,7 identifyingthe prevalenceand causesof

vision lossin these groupsin conjunction with general

populationsis critical to inform nationaleye health

programsand to achievethe objectivesof the Global

Action Plan.

Australia requires national prevalence data on vision loss

to fulfill its obligations as a signatory to the Global Action

Plan.State-levelsurveys conducted in the early 1990s in

Victoria,38 New South Wales,39 and South Australia40 have

been thereferencestudiesin Australiauntil now. We

conducted a nationwide study,the NationalEye Health

Survey (NEHS),to determine the prevalence and causes

of vision loss in Australia.This survey has implemented a

novelapproach to stratifying its sampling frame according

to Indigenous status to produce reliable estimates ofthe

prevalence and causes ofvision loss in both Indigenous

and non-Indigenous populations.We presentthe findings

of the NEHS and propose thatourstratified study design

forms the basis for future prevalence studies in all countr

with Indigenous groups.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The sampling methodology ofthe NEHS has been described in

detail.41 In brief, the targetpopulationwas stratifiedinto

Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous Australians.In accor-

dance with GlobalAction Plan guidelines,the NEHS recruited

non-IndigenousAustraliansaged 50 yearsor older.3 However,

because Indigenous Australians have earlier onset and more ra

progression ofeye disease and diabetes,42 a youngerage of40

years orolderwas selected.On the basisof the mostreliable

previousestimatesof the prevalenceof vision loss in

Australia,24,43the required sample size was 2794 non-Indigenous

Australiansand 1368 IndigenousAustraliansresidingin 30

geographic areas.

Multistage random-cluster sampling was used to selectpartic-

ipants on the basis of data from the 2011 Australian Census.44 In

stage 1 of sampling,the Australian population was stratified into

5 remoteness strata:Major City,Inner Regional,Outer Regional,

Remote,and Very Remote.Probabilityproportionalto size

sampling was used to select12 MajorCity, 6 InnerRegional,

6 OuterRegional,4 Remote,and 2 Very Remote survey sites,

corresponding to the approximate population distribution in ea

stratum.In the secondstage,a smallerclustercontaining

approximately 100 eligible residents was randomly selected an

nominated asthe enumeration site.Becauseof a numberof

factorsincludinginsufficientpopulationnumbers,inaccurate

Census data,and high absentee rates,a systematic approach was

used to make adjustmentsto some sites,including the use of

backup sitesand sampling from contiguousgeographicareas.

The details of this approach have been published.41 Door-to-door

recruitmentwas conducteduntil approximately100 non-

Indigenousparticipantswere recruitedfrom each cluster.

Although door-to-doorrecruitmentwas used forthe majority of

participants,we consulted Aboriginalelders and localAboriginal

Health Servicesto ensurethatour recruitmentmethodswere

culturallyappropriate.In someinstances,directdoor-to-door

recruitmentwas deemed culturally inappropriate,and telephone

recruitmentfrom formalizedcommunitylists was usedas a

substitute.Householdrecruitment,includingdoor-to-doorand

telephonerecruitment,accountedfor approximately80% of

Indigenous recruitment.Alternative methods ofcontactincluded

concurrent Indigenous health clinics and word of mouth.

The protocol was approved by the Royal Victorian Eye and E

Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, as well as state-b

Indigenousethicsorganizations.This study wasconducted in

accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedures

The examination protocolof the NEHS hasbeen described in

detail.45 Participantexaminations were conducted in a totalof 61

testing venues thatincluded community centers,mobile clinics,

town halls, AboriginalCorporations,schools,and medical

clinics,all within 6 km ofeach recruitmentsite.Examinations

were conducted over13 monthsand 7 days,from March 11,

OphthalmologyVolume- , Number- , Month 2017

2

2015,to April 18, 2016.Residentsattended testing centersat

prespecified appointmenttimesand provided written informed

consent.Standardized sociodemographic,stroke,diabetes,and

ocular history data were collectedusing an interviewer-

administered questionnaire.

Standardized eye examinations were conducted by researchers,

including ophthalmologists, optometrists, orthoptists, and research

assistants trained at the Centre for Eye Research Australia (CERA).

Presenting distancevisualacuity wasmeasured foreach eye

separately using a logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution

chart (Brien Holden Vision Institute, New South Wales, Australia)

in well-lit room conditions. Pinhole testing was performed using a

multiple pinhole occluder on participants with visual acuity <6/12

in 1 or both eyes.If visualacuity improved with pinhole testing,

autorefraction wasperformed using aNidek ARK-30 Type-R

handheld autorefractor/keratometer (Nidek Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan),

and autorefraction-corrected visual acuity was measured. Binocular

presenting near vision was assessed using a CERA “Tumbling E”

nearvision card (CERA,Melbourne,Australia)held atthe par-

ticipant’s preferred reading distance. The smallest line at which the

direction ofat least3 of the 4 “Tumbling E” optotypeswas

correctly identified was recorded. Visual fields were assessed using

a Frequency Doubling Technology perimeter(ZeissHumphrey

Systems,Oberkochen,Germany,and Welch Allyn,Skaneateles

Falls,NY).

Examination ofthe anteriorsegmentwas performed using a

hand-held slitlamp (KeelerOphthalmic Instruments,Berkshire,

UK) at 10 magnification. BecauseChlamydiatrachomatis

infection is endemic in Indigenous Australians,butnotin non-

Indigenous Australians,grading fortrachomatoustrichiasisand

cornealopacity was performed in Indigenous participants using

only the World Health Organization Trachoma Simplified Grading

System.46 If presenting visualacuity was<6/12 in eithereye,

examiners took an anterior segmentphoto in the affected eye(s)

with a DigitalRetinography System47 camera (CenterVue,SpA,

Padova,Italy).

Two-field,45 colorfundus photographs were taken ofeach

retina, centered on the macula and optic disc, respectively, using a

nonmydriatic Diabetic Retinopathy Screening camera in a dark-

ened room to allow forphysiologic mydriasis.In 663 patients

(13.7%) in whom photograph quality was poor because of small

pupilsize,tropicamide 0.5% was instilled to induce mydriasis if

anterior chambers were deemed wide enough to do so safely using

the method by Van Herick et al,48 and photographs were repeated.

Dilation was not performed when the angle was graded as 1 or 2.

Intraocularpressurewas measured using an iCareTonometer

(iCare,Vantaa,Finland).Participants were provided with verbal

feedback on the health oftheireyes,and those with suspected

pathology were provided with a referralletterto be taken to a

local doctor or optometrist.

Blinded retinal graders at CERA graded all retinal images using

OpenClinica software (OpenClinica LLC and collaborators,Wal-

tham, MA), and pathology was graded according to protocols that

have been described in detail.47,49,50

The main cause of vision loss was determined by 2 independent

ophthalmologists,and disagreements were adjudicated by a third

ophthalmologist.Data pertaining to participants’ age,gender,and

Indigenous status were provided to assist with disease attribution.

Uncorrected refractive errorwas assigned as the main cause of

vision loss when distance visual acuity improved to 6/12 in 1 or

both eyeswith pinhole orautorefraction.For all othercases,

ophthalmologists reviewed questionnaire responses and examina-

tion results to identify the condition mostlikely to accountfor

vision loss. When multiple disorders were identified, the condition

with the most clinically significant influence was determined to be

the primary cause.For cases in which a single primary cause was

notidentifiable,vision loss was attributed to combined mecha-

nisms. Cases of vision loss were deemed “not determinable” if

cause of vision loss was identified.

Definitions

Vision impairmentwas defined asbilateralpresenting distance

visual acuity to 6/60. Blindnesswas definedas bilateral

presenting distance visual acuity <6/60. Vision loss was define

bilateralpresenting distance visualacuity <6/12 and included all

cases ofvision impairmentand blindness.Participants with pre-

senting visual acuity <6/12 in 1 eye but 6/12 in the fellow eye

(unilateral vision loss) were not considered to have vision loss

the purpose of this article.

Statistical Analysis

The crude prevalence ofvision loss was calculated as the per-

centageof participantswith vision loss.Prevalencewas then

weighted to accountfor the sampling rate in each remoteness

stratum becausepopulation sizesvaried between strata.This

involved dividing the target population recruited from each stra

overthe population size in each stratum.This also allowed the

absolute number of Australians with vision loss in each stratum

be estimated.To facilitate comparisons between Indigenous and

non-Indigenous Australians, the weighted prevalence of vision

was adjusted for age and gender. Logistic regression analysis w

used to identify risk factors for vision loss. Factors associated w

vision loss atP < 0.10 in univariable analysis were included in

subsequent multivariable logistic regression analysis. A plot of

residuals compared with estimates was examined to testlinearity

and homoscedasticity. The Box-Tidwell model was used to find

bestpower for modelfit based on maximallikelihood estimates.

Logistic regression Model1 investigated risk factors forIndige-

nous and non-Indigenousparticipantstogether.In Model 2,

Indigenousand non-Indigenousparticipantswere investigated

separately.Analyses were conducted with STATA version 14.2.0

(StataCorp LP,College Station,TX).

Results

Participant Characteristics

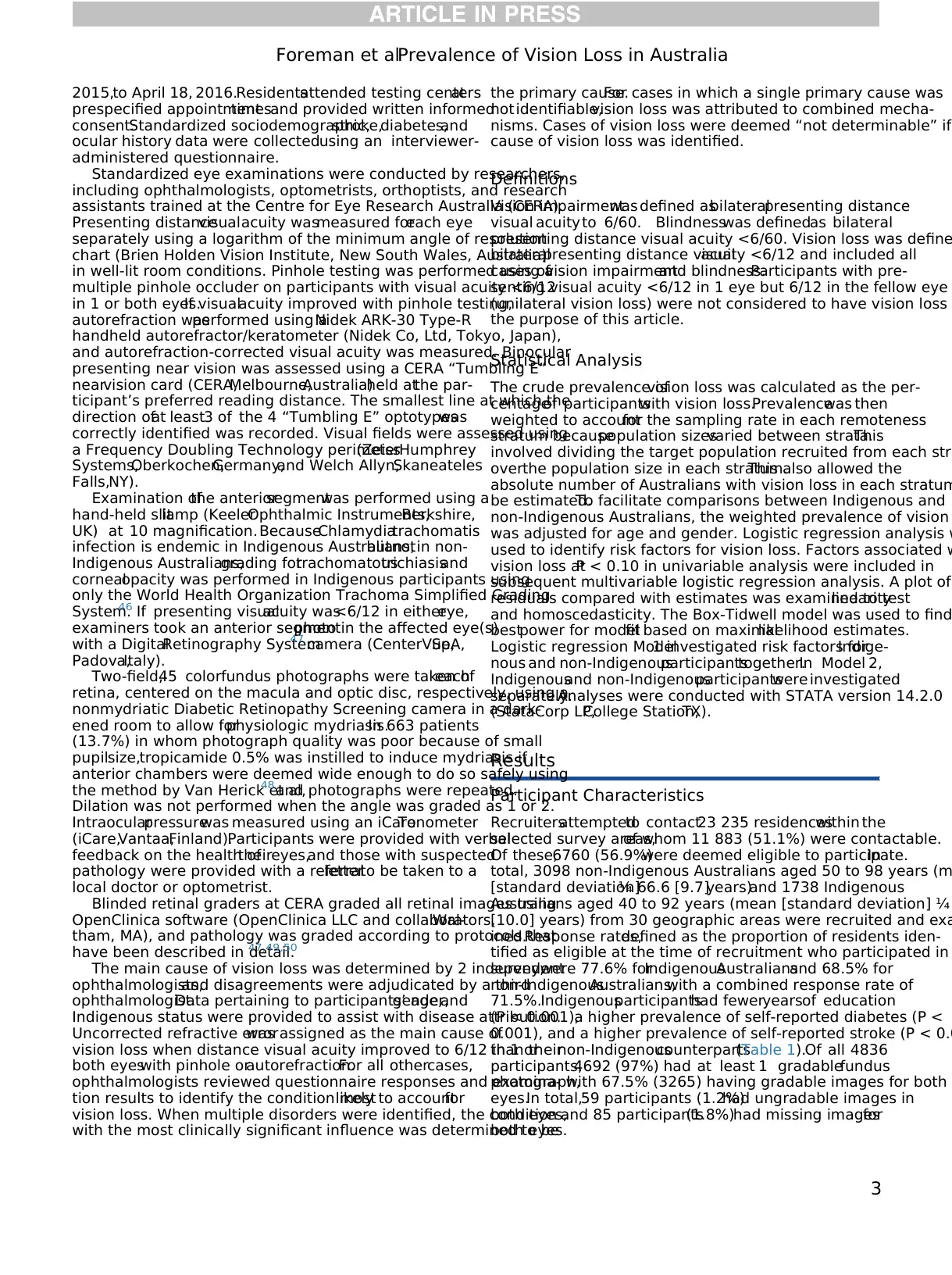

Recruitersattemptedto contact23 235 residenceswithin the

selected survey areas,of whom 11 883 (51.1%) were contactable.

Of these,6760 (56.9%)were deemed eligible to participate.In

total, 3098 non-Indigenous Australians aged 50 to 98 years (m

[standard deviation]¼ 66.6 [9.7]years)and 1738 Indigenous

Australians aged 40 to 92 years (mean [standard deviation] ¼

[10.0] years) from 30 geographic areas were recruited and exa

ined.Response rates,defined as the proportion of residents iden-

tified as eligible at the time of recruitment who participated in

survey,were 77.6% forIndigenousAustraliansand 68.5% for

non-IndigenousAustralians,with a combined response rate of

71.5%.Indigenousparticipantshad feweryearsof education

(P < 0.001),a higher prevalence of self-reported diabetes (P <

0.001), and a higher prevalence of self-reported stroke (P < 0.0

than theirnon-Indigenouscounterparts(Table 1).Of all 4836

participants,4692 (97%) had at least 1 gradablefundus

photograph,with 67.5% (3265) having gradable images for both

eyes.In total,59 participants (1.2%)had ungradable images in

both eyes,and 85 participants(1.8%)had missing imagesfor

both eyes.

Foreman et alPrevalence of Vision Loss in Australia

3

prespecified appointmenttimesand provided written informed

consent.Standardized sociodemographic,stroke,diabetes,and

ocular history data were collectedusing an interviewer-

administered questionnaire.

Standardized eye examinations were conducted by researchers,

including ophthalmologists, optometrists, orthoptists, and research

assistants trained at the Centre for Eye Research Australia (CERA).

Presenting distancevisualacuity wasmeasured foreach eye

separately using a logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution

chart (Brien Holden Vision Institute, New South Wales, Australia)

in well-lit room conditions. Pinhole testing was performed using a

multiple pinhole occluder on participants with visual acuity <6/12

in 1 or both eyes.If visualacuity improved with pinhole testing,

autorefraction wasperformed using aNidek ARK-30 Type-R

handheld autorefractor/keratometer (Nidek Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan),

and autorefraction-corrected visual acuity was measured. Binocular

presenting near vision was assessed using a CERA “Tumbling E”

nearvision card (CERA,Melbourne,Australia)held atthe par-

ticipant’s preferred reading distance. The smallest line at which the

direction ofat least3 of the 4 “Tumbling E” optotypeswas

correctly identified was recorded. Visual fields were assessed using

a Frequency Doubling Technology perimeter(ZeissHumphrey

Systems,Oberkochen,Germany,and Welch Allyn,Skaneateles

Falls,NY).

Examination ofthe anteriorsegmentwas performed using a

hand-held slitlamp (KeelerOphthalmic Instruments,Berkshire,

UK) at 10 magnification. BecauseChlamydiatrachomatis

infection is endemic in Indigenous Australians,butnotin non-

Indigenous Australians,grading fortrachomatoustrichiasisand

cornealopacity was performed in Indigenous participants using

only the World Health Organization Trachoma Simplified Grading

System.46 If presenting visualacuity was<6/12 in eithereye,

examiners took an anterior segmentphoto in the affected eye(s)

with a DigitalRetinography System47 camera (CenterVue,SpA,

Padova,Italy).

Two-field,45 colorfundus photographs were taken ofeach

retina, centered on the macula and optic disc, respectively, using a

nonmydriatic Diabetic Retinopathy Screening camera in a dark-

ened room to allow forphysiologic mydriasis.In 663 patients

(13.7%) in whom photograph quality was poor because of small

pupilsize,tropicamide 0.5% was instilled to induce mydriasis if

anterior chambers were deemed wide enough to do so safely using

the method by Van Herick et al,48 and photographs were repeated.

Dilation was not performed when the angle was graded as 1 or 2.

Intraocularpressurewas measured using an iCareTonometer

(iCare,Vantaa,Finland).Participants were provided with verbal

feedback on the health oftheireyes,and those with suspected

pathology were provided with a referralletterto be taken to a

local doctor or optometrist.

Blinded retinal graders at CERA graded all retinal images using

OpenClinica software (OpenClinica LLC and collaborators,Wal-

tham, MA), and pathology was graded according to protocols that

have been described in detail.47,49,50

The main cause of vision loss was determined by 2 independent

ophthalmologists,and disagreements were adjudicated by a third

ophthalmologist.Data pertaining to participants’ age,gender,and

Indigenous status were provided to assist with disease attribution.

Uncorrected refractive errorwas assigned as the main cause of

vision loss when distance visual acuity improved to 6/12 in 1 or

both eyeswith pinhole orautorefraction.For all othercases,

ophthalmologists reviewed questionnaire responses and examina-

tion results to identify the condition mostlikely to accountfor

vision loss. When multiple disorders were identified, the condition

with the most clinically significant influence was determined to be

the primary cause.For cases in which a single primary cause was

notidentifiable,vision loss was attributed to combined mecha-

nisms. Cases of vision loss were deemed “not determinable” if

cause of vision loss was identified.

Definitions

Vision impairmentwas defined asbilateralpresenting distance

visual acuity to 6/60. Blindnesswas definedas bilateral

presenting distance visual acuity <6/60. Vision loss was define

bilateralpresenting distance visualacuity <6/12 and included all

cases ofvision impairmentand blindness.Participants with pre-

senting visual acuity <6/12 in 1 eye but 6/12 in the fellow eye

(unilateral vision loss) were not considered to have vision loss

the purpose of this article.

Statistical Analysis

The crude prevalence ofvision loss was calculated as the per-

centageof participantswith vision loss.Prevalencewas then

weighted to accountfor the sampling rate in each remoteness

stratum becausepopulation sizesvaried between strata.This

involved dividing the target population recruited from each stra

overthe population size in each stratum.This also allowed the

absolute number of Australians with vision loss in each stratum

be estimated.To facilitate comparisons between Indigenous and

non-Indigenous Australians, the weighted prevalence of vision

was adjusted for age and gender. Logistic regression analysis w

used to identify risk factors for vision loss. Factors associated w

vision loss atP < 0.10 in univariable analysis were included in

subsequent multivariable logistic regression analysis. A plot of

residuals compared with estimates was examined to testlinearity

and homoscedasticity. The Box-Tidwell model was used to find

bestpower for modelfit based on maximallikelihood estimates.

Logistic regression Model1 investigated risk factors forIndige-

nous and non-Indigenousparticipantstogether.In Model 2,

Indigenousand non-Indigenousparticipantswere investigated

separately.Analyses were conducted with STATA version 14.2.0

(StataCorp LP,College Station,TX).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Recruitersattemptedto contact23 235 residenceswithin the

selected survey areas,of whom 11 883 (51.1%) were contactable.

Of these,6760 (56.9%)were deemed eligible to participate.In

total, 3098 non-Indigenous Australians aged 50 to 98 years (m

[standard deviation]¼ 66.6 [9.7]years)and 1738 Indigenous

Australians aged 40 to 92 years (mean [standard deviation] ¼

[10.0] years) from 30 geographic areas were recruited and exa

ined.Response rates,defined as the proportion of residents iden-

tified as eligible at the time of recruitment who participated in

survey,were 77.6% forIndigenousAustraliansand 68.5% for

non-IndigenousAustralians,with a combined response rate of

71.5%.Indigenousparticipantshad feweryearsof education

(P < 0.001),a higher prevalence of self-reported diabetes (P <

0.001), and a higher prevalence of self-reported stroke (P < 0.0

than theirnon-Indigenouscounterparts(Table 1).Of all 4836

participants,4692 (97%) had at least 1 gradablefundus

photograph,with 67.5% (3265) having gradable images for both

eyes.In total,59 participants (1.2%)had ungradable images in

both eyes,and 85 participants(1.8%)had missing imagesfor

both eyes.

Foreman et alPrevalence of Vision Loss in Australia

3

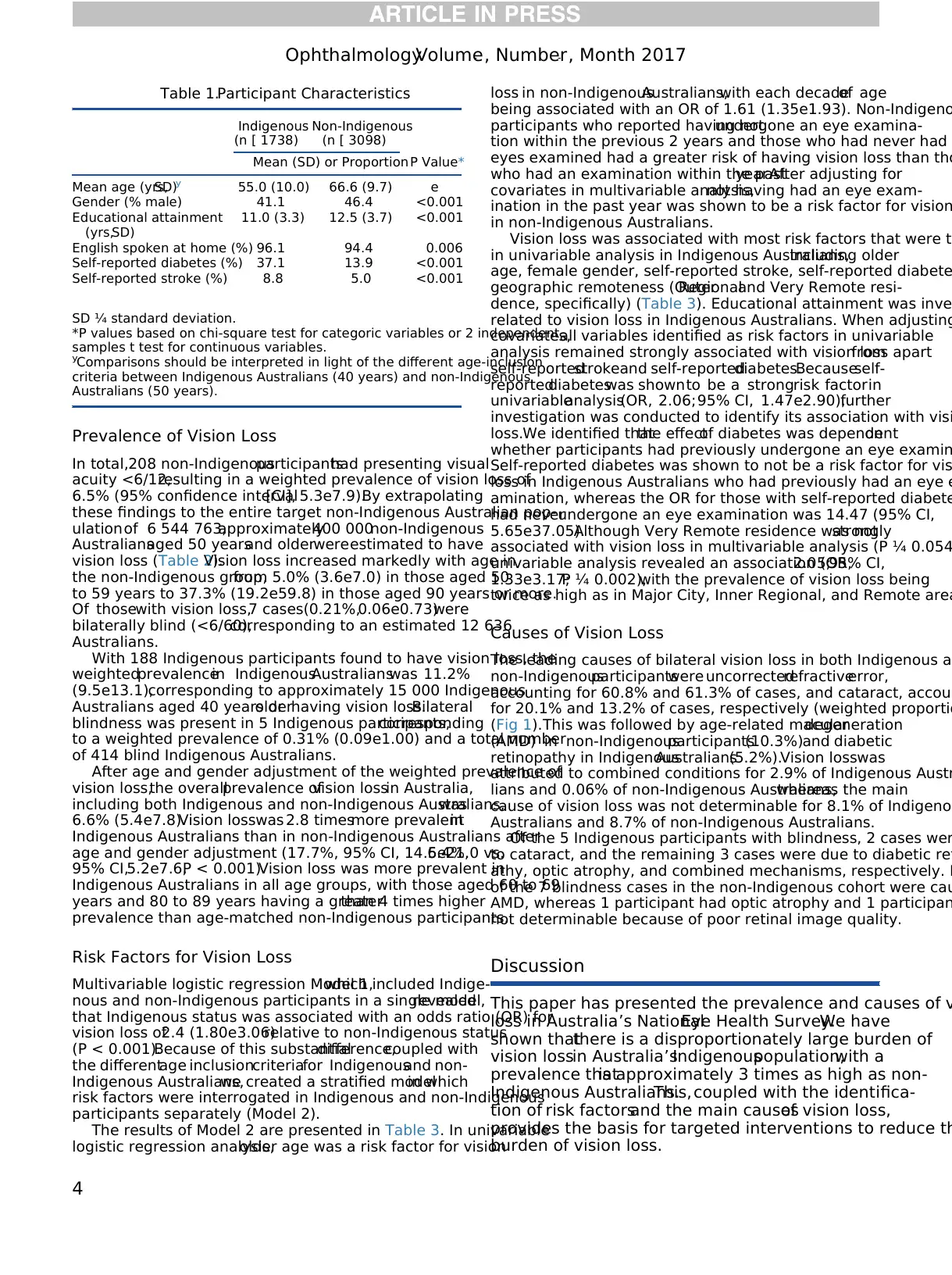

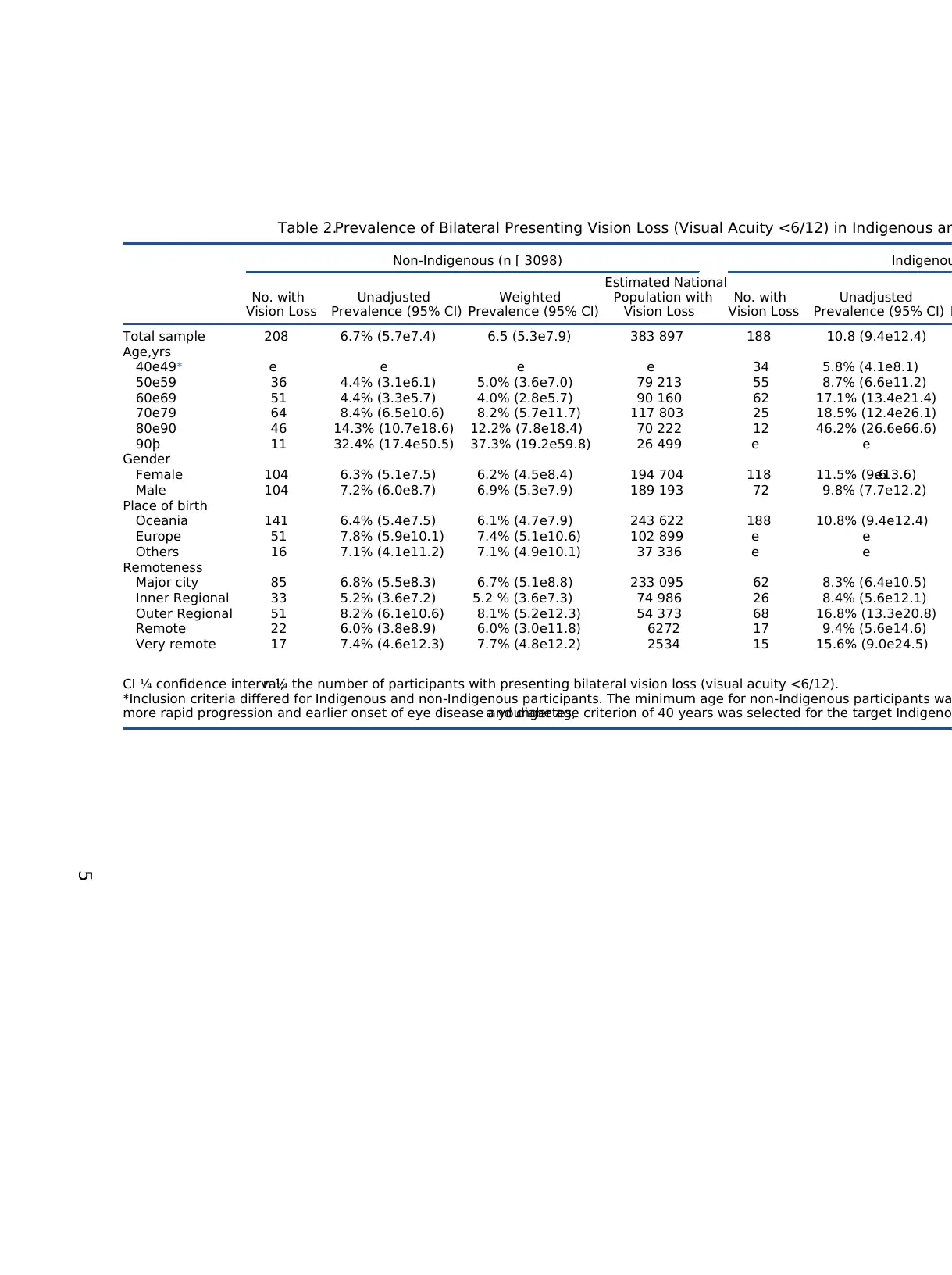

Prevalence of Vision Loss

In total,208 non-Indigenousparticipantshad presenting visual

acuity <6/12,resulting in a weighted prevalence of vision loss of

6.5% (95% confidence interval[CI], 5.3e7.9).By extrapolating

these findings to the entire target non-Indigenous Australian pop-

ulationof 6 544 763,approximately400 000non-Indigenous

Australiansaged 50 yearsand olderwereestimated to have

vision loss (Table 2).Vision loss increased markedly with age in

the non-Indigenous group,from 5.0% (3.6e7.0) in those aged 50

to 59 years to 37.3% (19.2e59.8) in those aged 90 years or more.

Of thosewith vision loss,7 cases(0.21%,0.06e0.73)were

bilaterally blind (<6/60),corresponding to an estimated 12 636

Australians.

With 188 Indigenous participants found to have vision loss, the

weightedprevalencein IndigenousAustralianswas 11.2%

(9.5e13.1),corresponding to approximately 15 000 Indigenous

Australians aged 40 years orolderhaving vision loss.Bilateral

blindness was present in 5 Indigenous participants,corresponding

to a weighted prevalence of 0.31% (0.09e1.00) and a total number

of 414 blind Indigenous Australians.

After age and gender adjustment of the weighted prevalence of

vision loss,the overallprevalence ofvision lossin Australia,

including both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians,was

6.6% (5.4e7.8).Vision losswas 2.8 timesmore prevalentin

Indigenous Australians than in non-Indigenous Australians after

age and gender adjustment (17.7%, 95% CI, 14.5e21.0 vs.6.4%,

95% CI,5.2e7.6,P < 0.001).Vision loss was more prevalent in

Indigenous Australians in all age groups, with those aged 60 to 69

years and 80 to 89 years having a greaterthan 4 times higher

prevalence than age-matched non-Indigenous participants.

Risk Factors for Vision Loss

Multivariable logistic regression Model 1,which included Indige-

nous and non-Indigenous participants in a single model,revealed

that Indigenous status was associated with an odds ratio (OR) for

vision loss of2.4 (1.80e3.06)relative to non-Indigenous status

(P < 0.001).Because of this substantialdifference,coupled with

the differentage inclusioncriteriafor Indigenousand non-

Indigenous Australians,we created a stratified modelin which

risk factors were interrogated in Indigenous and non-Indigenous

participants separately (Model 2).

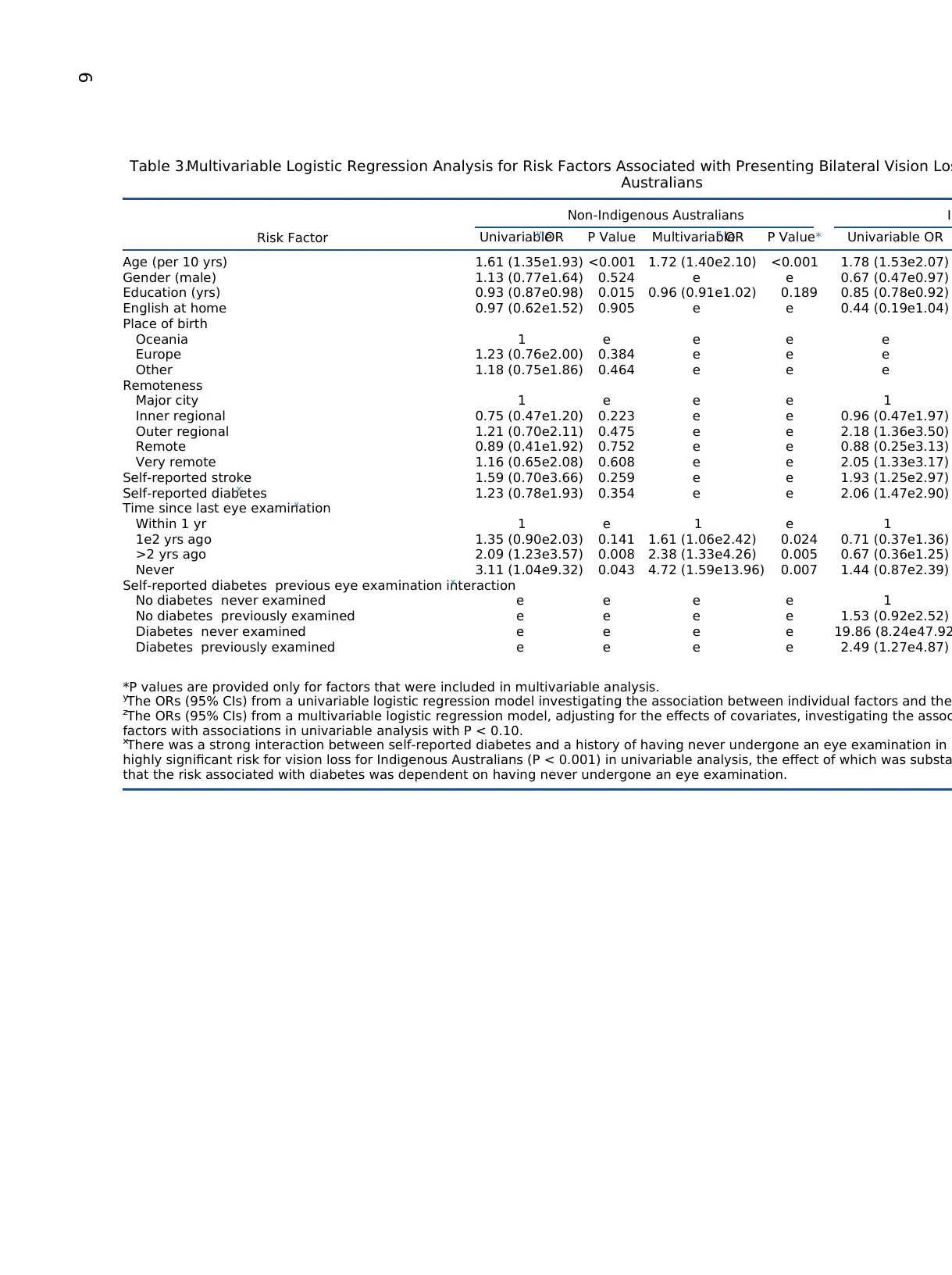

The results of Model 2 are presented in Table 3. In univariable

logistic regression analysis,older age was a risk factor for vision

loss in non-IndigenousAustralians,with each decadeof age

being associated with an OR of 1.61 (1.35e1.93). Non-Indigeno

participants who reported having notundergone an eye examina-

tion within the previous 2 years and those who had never had

eyes examined had a greater risk of having vision loss than tho

who had an examination within the pastyear.After adjusting for

covariates in multivariable analysis,not having had an eye exam-

ination in the past year was shown to be a risk factor for vision

in non-Indigenous Australians.

Vision loss was associated with most risk factors that were te

in univariable analysis in Indigenous Australians,including older

age, female gender, self-reported stroke, self-reported diabete

geographic remoteness (OuterRegionaland Very Remote resi-

dence, specifically) (Table 3). Educational attainment was inve

related to vision loss in Indigenous Australians. When adjusting

covariates,all variables identified as risk factors in univariable

analysis remained strongly associated with vision loss apartfrom

self-reportedstrokeand self-reporteddiabetes.Becauseself-

reporteddiabeteswas shownto be a strongrisk factorin

univariableanalysis(OR, 2.06;95% CI, 1.47e2.90),further

investigation was conducted to identify its association with visi

loss.We identified thatthe effectof diabetes was dependenton

whether participants had previously undergone an eye examin

Self-reported diabetes was shown to not be a risk factor for vis

loss in Indigenous Australians who had previously had an eye e

amination, whereas the OR for those with self-reported diabete

had neverundergone an eye examination was 14.47 (95% CI,

5.65e37.05).Although Very Remote residence was notstrongly

associated with vision loss in multivariable analysis (P ¼ 0.054

univariable analysis revealed an association (OR,2.05;95% CI,

1.33e3.17;P ¼ 0.002),with the prevalence of vision loss being

twice as high as in Major City, Inner Regional, and Remote area

Causes of Vision Loss

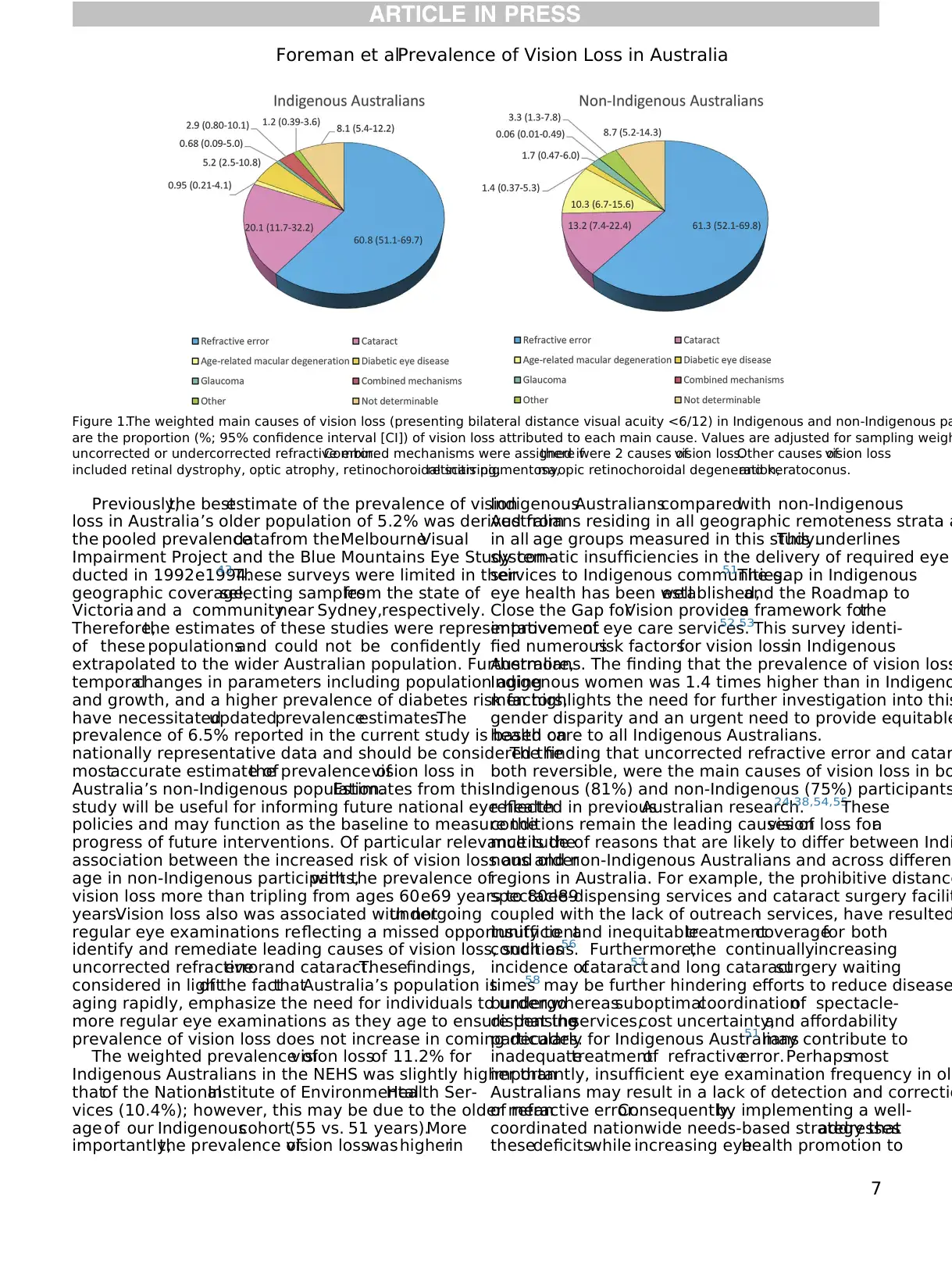

The leading causes of bilateral vision loss in both Indigenous an

non-Indigenousparticipantswere uncorrectedrefractiveerror,

accounting for 60.8% and 61.3% of cases, and cataract, accoun

for 20.1% and 13.2% of cases, respectively (weighted proportio

(Fig 1).This was followed by age-related maculardegeneration

(AMD) in non-Indigenousparticipants(10.3%)and diabetic

retinopathy in IndigenousAustralians(5.2%).Vision losswas

attributed to combined conditions for 2.9% of Indigenous Austr

lians and 0.06% of non-Indigenous Australians,whereas the main

cause of vision loss was not determinable for 8.1% of Indigenou

Australians and 8.7% of non-Indigenous Australians.

Of the 5 Indigenous participants with blindness, 2 cases wer

to cataract, and the remaining 3 cases were due to diabetic ret

athy, optic atrophy, and combined mechanisms, respectively. F

of the 7 blindness cases in the non-Indigenous cohort were cau

AMD, whereas 1 participant had optic atrophy and 1 participan

not determinable because of poor retinal image quality.

Discussion

This paper has presented the prevalence and causes of v

loss in Australia’s NationalEye Health Survey.We have

shown thatthere is a disproportionately large burden of

vision lossin Australia’sIndigenouspopulation,with a

prevalence thatis approximately 3 times as high as non-

Indigenous Australians.This, coupled with the identifica-

tion of risk factorsand the main causesof vision loss,

provides the basis for targeted interventions to reduce th

burden of vision loss.

Table 1.Participant Characteristics

Indigenous

(n [ 1738)

Non-Indigenous

(n [ 3098)

P Value*Mean (SD) or Proportion

Mean age (yrs,SD)y 55.0 (10.0) 66.6 (9.7) e

Gender (% male) 41.1 46.4 <0.001

Educational attainment

(yrs,SD)

11.0 (3.3) 12.5 (3.7) <0.001

English spoken at home (%) 96.1 94.4 0.006

Self-reported diabetes (%) 37.1 13.9 <0.001

Self-reported stroke (%) 8.8 5.0 <0.001

SD ¼ standard deviation.

*P values based on chi-square test for categoric variables or 2 independent

samples t test for continuous variables.

yComparisons should be interpreted in light of the different age-inclusion

criteria between Indigenous Australians (40 years) and non-Indigenous

Australians (50 years).

OphthalmologyVolume- , Number- , Month 2017

4

In total,208 non-Indigenousparticipantshad presenting visual

acuity <6/12,resulting in a weighted prevalence of vision loss of

6.5% (95% confidence interval[CI], 5.3e7.9).By extrapolating

these findings to the entire target non-Indigenous Australian pop-

ulationof 6 544 763,approximately400 000non-Indigenous

Australiansaged 50 yearsand olderwereestimated to have

vision loss (Table 2).Vision loss increased markedly with age in

the non-Indigenous group,from 5.0% (3.6e7.0) in those aged 50

to 59 years to 37.3% (19.2e59.8) in those aged 90 years or more.

Of thosewith vision loss,7 cases(0.21%,0.06e0.73)were

bilaterally blind (<6/60),corresponding to an estimated 12 636

Australians.

With 188 Indigenous participants found to have vision loss, the

weightedprevalencein IndigenousAustralianswas 11.2%

(9.5e13.1),corresponding to approximately 15 000 Indigenous

Australians aged 40 years orolderhaving vision loss.Bilateral

blindness was present in 5 Indigenous participants,corresponding

to a weighted prevalence of 0.31% (0.09e1.00) and a total number

of 414 blind Indigenous Australians.

After age and gender adjustment of the weighted prevalence of

vision loss,the overallprevalence ofvision lossin Australia,

including both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians,was

6.6% (5.4e7.8).Vision losswas 2.8 timesmore prevalentin

Indigenous Australians than in non-Indigenous Australians after

age and gender adjustment (17.7%, 95% CI, 14.5e21.0 vs.6.4%,

95% CI,5.2e7.6,P < 0.001).Vision loss was more prevalent in

Indigenous Australians in all age groups, with those aged 60 to 69

years and 80 to 89 years having a greaterthan 4 times higher

prevalence than age-matched non-Indigenous participants.

Risk Factors for Vision Loss

Multivariable logistic regression Model 1,which included Indige-

nous and non-Indigenous participants in a single model,revealed

that Indigenous status was associated with an odds ratio (OR) for

vision loss of2.4 (1.80e3.06)relative to non-Indigenous status

(P < 0.001).Because of this substantialdifference,coupled with

the differentage inclusioncriteriafor Indigenousand non-

Indigenous Australians,we created a stratified modelin which

risk factors were interrogated in Indigenous and non-Indigenous

participants separately (Model 2).

The results of Model 2 are presented in Table 3. In univariable

logistic regression analysis,older age was a risk factor for vision

loss in non-IndigenousAustralians,with each decadeof age

being associated with an OR of 1.61 (1.35e1.93). Non-Indigeno

participants who reported having notundergone an eye examina-

tion within the previous 2 years and those who had never had

eyes examined had a greater risk of having vision loss than tho

who had an examination within the pastyear.After adjusting for

covariates in multivariable analysis,not having had an eye exam-

ination in the past year was shown to be a risk factor for vision

in non-Indigenous Australians.

Vision loss was associated with most risk factors that were te

in univariable analysis in Indigenous Australians,including older

age, female gender, self-reported stroke, self-reported diabete

geographic remoteness (OuterRegionaland Very Remote resi-

dence, specifically) (Table 3). Educational attainment was inve

related to vision loss in Indigenous Australians. When adjusting

covariates,all variables identified as risk factors in univariable

analysis remained strongly associated with vision loss apartfrom

self-reportedstrokeand self-reporteddiabetes.Becauseself-

reporteddiabeteswas shownto be a strongrisk factorin

univariableanalysis(OR, 2.06;95% CI, 1.47e2.90),further

investigation was conducted to identify its association with visi

loss.We identified thatthe effectof diabetes was dependenton

whether participants had previously undergone an eye examin

Self-reported diabetes was shown to not be a risk factor for vis

loss in Indigenous Australians who had previously had an eye e

amination, whereas the OR for those with self-reported diabete

had neverundergone an eye examination was 14.47 (95% CI,

5.65e37.05).Although Very Remote residence was notstrongly

associated with vision loss in multivariable analysis (P ¼ 0.054

univariable analysis revealed an association (OR,2.05;95% CI,

1.33e3.17;P ¼ 0.002),with the prevalence of vision loss being

twice as high as in Major City, Inner Regional, and Remote area

Causes of Vision Loss

The leading causes of bilateral vision loss in both Indigenous an

non-Indigenousparticipantswere uncorrectedrefractiveerror,

accounting for 60.8% and 61.3% of cases, and cataract, accoun

for 20.1% and 13.2% of cases, respectively (weighted proportio

(Fig 1).This was followed by age-related maculardegeneration

(AMD) in non-Indigenousparticipants(10.3%)and diabetic

retinopathy in IndigenousAustralians(5.2%).Vision losswas

attributed to combined conditions for 2.9% of Indigenous Austr

lians and 0.06% of non-Indigenous Australians,whereas the main

cause of vision loss was not determinable for 8.1% of Indigenou

Australians and 8.7% of non-Indigenous Australians.

Of the 5 Indigenous participants with blindness, 2 cases wer

to cataract, and the remaining 3 cases were due to diabetic ret

athy, optic atrophy, and combined mechanisms, respectively. F

of the 7 blindness cases in the non-Indigenous cohort were cau

AMD, whereas 1 participant had optic atrophy and 1 participan

not determinable because of poor retinal image quality.

Discussion

This paper has presented the prevalence and causes of v

loss in Australia’s NationalEye Health Survey.We have

shown thatthere is a disproportionately large burden of

vision lossin Australia’sIndigenouspopulation,with a

prevalence thatis approximately 3 times as high as non-

Indigenous Australians.This, coupled with the identifica-

tion of risk factorsand the main causesof vision loss,

provides the basis for targeted interventions to reduce th

burden of vision loss.

Table 1.Participant Characteristics

Indigenous

(n [ 1738)

Non-Indigenous

(n [ 3098)

P Value*Mean (SD) or Proportion

Mean age (yrs,SD)y 55.0 (10.0) 66.6 (9.7) e

Gender (% male) 41.1 46.4 <0.001

Educational attainment

(yrs,SD)

11.0 (3.3) 12.5 (3.7) <0.001

English spoken at home (%) 96.1 94.4 0.006

Self-reported diabetes (%) 37.1 13.9 <0.001

Self-reported stroke (%) 8.8 5.0 <0.001

SD ¼ standard deviation.

*P values based on chi-square test for categoric variables or 2 independent

samples t test for continuous variables.

yComparisons should be interpreted in light of the different age-inclusion

criteria between Indigenous Australians (40 years) and non-Indigenous

Australians (50 years).

OphthalmologyVolume- , Number- , Month 2017

4

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Table 2.Prevalence of Bilateral Presenting Vision Loss (Visual Acuity <6/12) in Indigenous an

Non-Indigenous (n [ 3098) Indigenou

No. with

Vision Loss

Unadjusted

Prevalence (95% CI)

Weighted

Prevalence (95% CI)

Estimated National

Population with

Vision Loss

No. with

Vision Loss

Unadjusted

Prevalence (95% CI) P

Total sample 208 6.7% (5.7e7.4) 6.5 (5.3e7.9) 383 897 188 10.8 (9.4e12.4)

Age,yrs

40e49* e e e e 34 5.8% (4.1e8.1)

50e59 36 4.4% (3.1e6.1) 5.0% (3.6e7.0) 79 213 55 8.7% (6.6e11.2)

60e69 51 4.4% (3.3e5.7) 4.0% (2.8e5.7) 90 160 62 17.1% (13.4e21.4)

70e79 64 8.4% (6.5e10.6) 8.2% (5.7e11.7) 117 803 25 18.5% (12.4e26.1)

80e90 46 14.3% (10.7e18.6) 12.2% (7.8e18.4) 70 222 12 46.2% (26.6e66.6)

90þ 11 32.4% (17.4e50.5) 37.3% (19.2e59.8) 26 499 e e

Gender

Female 104 6.3% (5.1e7.5) 6.2% (4.5e8.4) 194 704 118 11.5% (9.6e13.6)

Male 104 7.2% (6.0e8.7) 6.9% (5.3e7.9) 189 193 72 9.8% (7.7e12.2)

Place of birth

Oceania 141 6.4% (5.4e7.5) 6.1% (4.7e7.9) 243 622 188 10.8% (9.4e12.4)

Europe 51 7.8% (5.9e10.1) 7.4% (5.1e10.6) 102 899 e e

Others 16 7.1% (4.1e11.2) 7.1% (4.9e10.1) 37 336 e e

Remoteness

Major city 85 6.8% (5.5e8.3) 6.7% (5.1e8.8) 233 095 62 8.3% (6.4e10.5)

Inner Regional 33 5.2% (3.6e7.2) 5.2 % (3.6e7.3) 74 986 26 8.4% (5.6e12.1)

Outer Regional 51 8.2% (6.1e10.6) 8.1% (5.2e12.3) 54 373 68 16.8% (13.3e20.8)

Remote 22 6.0% (3.8e8.9) 6.0% (3.0e11.8) 6272 17 9.4% (5.6e14.6)

Very remote 17 7.4% (4.6e12.3) 7.7% (4.8e12.2) 2534 15 15.6% (9.0e24.5)

CI ¼ confidence interval;n ¼ the number of participants with presenting bilateral vision loss (visual acuity <6/12).

*Inclusion criteria differed for Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants. The minimum age for non-Indigenous participants wa

more rapid progression and earlier onset of eye disease and diabetes,a younger age criterion of 40 years was selected for the target Indigeno

5

Non-Indigenous (n [ 3098) Indigenou

No. with

Vision Loss

Unadjusted

Prevalence (95% CI)

Weighted

Prevalence (95% CI)

Estimated National

Population with

Vision Loss

No. with

Vision Loss

Unadjusted

Prevalence (95% CI) P

Total sample 208 6.7% (5.7e7.4) 6.5 (5.3e7.9) 383 897 188 10.8 (9.4e12.4)

Age,yrs

40e49* e e e e 34 5.8% (4.1e8.1)

50e59 36 4.4% (3.1e6.1) 5.0% (3.6e7.0) 79 213 55 8.7% (6.6e11.2)

60e69 51 4.4% (3.3e5.7) 4.0% (2.8e5.7) 90 160 62 17.1% (13.4e21.4)

70e79 64 8.4% (6.5e10.6) 8.2% (5.7e11.7) 117 803 25 18.5% (12.4e26.1)

80e90 46 14.3% (10.7e18.6) 12.2% (7.8e18.4) 70 222 12 46.2% (26.6e66.6)

90þ 11 32.4% (17.4e50.5) 37.3% (19.2e59.8) 26 499 e e

Gender

Female 104 6.3% (5.1e7.5) 6.2% (4.5e8.4) 194 704 118 11.5% (9.6e13.6)

Male 104 7.2% (6.0e8.7) 6.9% (5.3e7.9) 189 193 72 9.8% (7.7e12.2)

Place of birth

Oceania 141 6.4% (5.4e7.5) 6.1% (4.7e7.9) 243 622 188 10.8% (9.4e12.4)

Europe 51 7.8% (5.9e10.1) 7.4% (5.1e10.6) 102 899 e e

Others 16 7.1% (4.1e11.2) 7.1% (4.9e10.1) 37 336 e e

Remoteness

Major city 85 6.8% (5.5e8.3) 6.7% (5.1e8.8) 233 095 62 8.3% (6.4e10.5)

Inner Regional 33 5.2% (3.6e7.2) 5.2 % (3.6e7.3) 74 986 26 8.4% (5.6e12.1)

Outer Regional 51 8.2% (6.1e10.6) 8.1% (5.2e12.3) 54 373 68 16.8% (13.3e20.8)

Remote 22 6.0% (3.8e8.9) 6.0% (3.0e11.8) 6272 17 9.4% (5.6e14.6)

Very remote 17 7.4% (4.6e12.3) 7.7% (4.8e12.2) 2534 15 15.6% (9.0e24.5)

CI ¼ confidence interval;n ¼ the number of participants with presenting bilateral vision loss (visual acuity <6/12).

*Inclusion criteria differed for Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants. The minimum age for non-Indigenous participants wa

more rapid progression and earlier onset of eye disease and diabetes,a younger age criterion of 40 years was selected for the target Indigeno

5

Table 3.Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis for Risk Factors Associated with Presenting Bilateral Vision Los

Australians

Risk Factor

Non-Indigenous Australians In

Univariabley OR P Value Multivariablez OR P Value* Univariable OR

Age (per 10 yrs) 1.61 (1.35e1.93) <0.001 1.72 (1.40e2.10) <0.001 1.78 (1.53e2.07)

Gender (male) 1.13 (0.77e1.64) 0.524 e e 0.67 (0.47e0.97)

Education (yrs) 0.93 (0.87e0.98) 0.015 0.96 (0.91e1.02) 0.189 0.85 (0.78e0.92)

English at home 0.97 (0.62e1.52) 0.905 e e 0.44 (0.19e1.04)

Place of birth

Oceania 1 e e e e

Europe 1.23 (0.76e2.00) 0.384 e e e

Other 1.18 (0.75e1.86) 0.464 e e e

Remoteness

Major city 1 e e e 1

Inner regional 0.75 (0.47e1.20) 0.223 e e 0.96 (0.47e1.97)

Outer regional 1.21 (0.70e2.11) 0.475 e e 2.18 (1.36e3.50)

Remote 0.89 (0.41e1.92) 0.752 e e 0.88 (0.25e3.13)

Very remote 1.16 (0.65e2.08) 0.608 e e 2.05 (1.33e3.17)

Self-reported stroke 1.59 (0.70e3.66) 0.259 e e 1.93 (1.25e2.97)

Self-reported diabetesx 1.23 (0.78e1.93) 0.354 e e 2.06 (1.47e2.90)

Time since last eye examinationx

Within 1 yr 1 e 1 e 1

1e2 yrs ago 1.35 (0.90e2.03) 0.141 1.61 (1.06e2.42) 0.024 0.71 (0.37e1.36)

>2 yrs ago 2.09 (1.23e3.57) 0.008 2.38 (1.33e4.26) 0.005 0.67 (0.36e1.25)

Never 3.11 (1.04e9.32) 0.043 4.72 (1.59e13.96) 0.007 1.44 (0.87e2.39)

Self-reported diabetes previous eye examination interactionx

No diabetes never examined e e e e 1

No diabetes previously examined e e e e 1.53 (0.92e2.52)

Diabetes never examined e e e e 19.86 (8.24e47.92

Diabetes previously examined e e e e 2.49 (1.27e4.87)

*P values are provided only for factors that were included in multivariable analysis.

yThe ORs (95% CIs) from a univariable logistic regression model investigating the association between individual factors and the

zThe ORs (95% CIs) from a multivariable logistic regression model, adjusting for the effects of covariates, investigating the assoc

factors with associations in univariable analysis with P < 0.10.

xThere was a strong interaction between self-reported diabetes and a history of having never undergone an eye examination in I

highly significant risk for vision loss for Indigenous Australians (P < 0.001) in univariable analysis, the effect of which was substa

that the risk associated with diabetes was dependent on having never undergone an eye examination.

6

Australians

Risk Factor

Non-Indigenous Australians In

Univariabley OR P Value Multivariablez OR P Value* Univariable OR

Age (per 10 yrs) 1.61 (1.35e1.93) <0.001 1.72 (1.40e2.10) <0.001 1.78 (1.53e2.07)

Gender (male) 1.13 (0.77e1.64) 0.524 e e 0.67 (0.47e0.97)

Education (yrs) 0.93 (0.87e0.98) 0.015 0.96 (0.91e1.02) 0.189 0.85 (0.78e0.92)

English at home 0.97 (0.62e1.52) 0.905 e e 0.44 (0.19e1.04)

Place of birth

Oceania 1 e e e e

Europe 1.23 (0.76e2.00) 0.384 e e e

Other 1.18 (0.75e1.86) 0.464 e e e

Remoteness

Major city 1 e e e 1

Inner regional 0.75 (0.47e1.20) 0.223 e e 0.96 (0.47e1.97)

Outer regional 1.21 (0.70e2.11) 0.475 e e 2.18 (1.36e3.50)

Remote 0.89 (0.41e1.92) 0.752 e e 0.88 (0.25e3.13)

Very remote 1.16 (0.65e2.08) 0.608 e e 2.05 (1.33e3.17)

Self-reported stroke 1.59 (0.70e3.66) 0.259 e e 1.93 (1.25e2.97)

Self-reported diabetesx 1.23 (0.78e1.93) 0.354 e e 2.06 (1.47e2.90)

Time since last eye examinationx

Within 1 yr 1 e 1 e 1

1e2 yrs ago 1.35 (0.90e2.03) 0.141 1.61 (1.06e2.42) 0.024 0.71 (0.37e1.36)

>2 yrs ago 2.09 (1.23e3.57) 0.008 2.38 (1.33e4.26) 0.005 0.67 (0.36e1.25)

Never 3.11 (1.04e9.32) 0.043 4.72 (1.59e13.96) 0.007 1.44 (0.87e2.39)

Self-reported diabetes previous eye examination interactionx

No diabetes never examined e e e e 1

No diabetes previously examined e e e e 1.53 (0.92e2.52)

Diabetes never examined e e e e 19.86 (8.24e47.92

Diabetes previously examined e e e e 2.49 (1.27e4.87)

*P values are provided only for factors that were included in multivariable analysis.

yThe ORs (95% CIs) from a univariable logistic regression model investigating the association between individual factors and the

zThe ORs (95% CIs) from a multivariable logistic regression model, adjusting for the effects of covariates, investigating the assoc

factors with associations in univariable analysis with P < 0.10.

xThere was a strong interaction between self-reported diabetes and a history of having never undergone an eye examination in I

highly significant risk for vision loss for Indigenous Australians (P < 0.001) in univariable analysis, the effect of which was substa

that the risk associated with diabetes was dependent on having never undergone an eye examination.

6

Previously,the bestestimate of the prevalence of vision

loss in Australia’s older population of 5.2% was derived from

the pooled prevalencedatafrom theMelbourneVisual

Impairment Project and the Blue Mountains Eye Study con-

ducted in 1992e1994.43 These surveys were limited in their

geographic coverage,selecting samplesfrom the state of

Victoria and a communitynear Sydney,respectively.

Therefore,the estimates of these studies were representative

of these populationsand could not be confidently

extrapolated to the wider Australian population. Furthermore,

temporalchanges in parameters including population aging

and growth, and a higher prevalence of diabetes risk factors,

have necessitatedupdatedprevalenceestimates.The

prevalence of 6.5% reported in the current study is based on

nationally representative data and should be considered the

mostaccurate estimate ofthe prevalence ofvision loss in

Australia’s non-Indigenous population.Estimates from this

study will be useful for informing future national eye health

policies and may function as the baseline to measure the

progress of future interventions. Of particular relevance is the

association between the increased risk of vision loss and older

age in non-Indigenous participants,with the prevalence of

vision loss more than tripling from ages 60e69 years to 80e89

years.Vision loss also was associated with notundergoing

regular eye examinations reflecting a missed opportunity to

identify and remediate leading causes of vision loss, such as

uncorrected refractiveerrorand cataract.Thesefindings,

considered in lightof the factthatAustralia’s population is

aging rapidly, emphasize the need for individuals to undergo

more regular eye examinations as they age to ensure that the

prevalence of vision loss does not increase in coming decades.

The weighted prevalence ofvision lossof 11.2% for

Indigenous Australians in the NEHS was slightly higher than

thatof the NationalInstitute of EnvironmentalHealth Ser-

vices (10.4%); however, this may be due to the older mean

age of our Indigenouscohort(55 vs. 51 years).More

importantly,the prevalence ofvision losswashigherin

IndigenousAustralianscomparedwith non-Indigenous

Australians residing in all geographic remoteness strata a

in all age groups measured in this study.This underlines

systematic insufficiencies in the delivery of required eye

services to Indigenous communities.51The gap in Indigenous

eye health has been wellestablished,and the Roadmap to

Close the Gap forVision providesa framework forthe

improvementof eye care services.52,53This survey identi-

fied numerousrisk factorsfor vision lossin Indigenous

Australians. The finding that the prevalence of vision loss

Indigenous women was 1.4 times higher than in Indigeno

men highlights the need for further investigation into this

gender disparity and an urgent need to provide equitable

health care to all Indigenous Australians.

The finding that uncorrected refractive error and catar

both reversible, were the main causes of vision loss in bo

Indigenous (81%) and non-Indigenous (75%) participants

reflected in previousAustralian research.24,38,54,55

These

conditions remain the leading causes ofvision loss fora

multitude of reasons that are likely to differ between Indi

nous and non-Indigenous Australians and across different

regions in Australia. For example, the prohibitive distance

spectacle-dispensing services and cataract surgery facilit

coupled with the lack of outreach services, have resulted

insufficientand inequitabletreatmentcoveragefor both

conditions.56 Furthermore,the continuallyincreasing

incidence ofcataract57 and long cataractsurgery waiting

times58 may be further hindering efforts to reduce disease

burden,whereassuboptimalcoordinationof spectacle-

dispensingservices,cost uncertainty,and affordability

particularly for Indigenous Australians51 may contribute to

inadequatetreatmentof refractiveerror.Perhapsmost

importantly, insufficient eye examination frequency in old

Australians may result in a lack of detection and correctio

of refractive error.Consequently,by implementing a well-

coordinated nationwide needs-based strategy thataddresses

thesedeficitswhile increasing eyehealth promotion to

Figure 1.The weighted main causes of vision loss (presenting bilateral distance visual acuity <6/12) in Indigenous and non-Indigenous pa

are the proportion (%; 95% confidence interval [CI]) of vision loss attributed to each main cause. Values are adjusted for sampling weigh

uncorrected or undercorrected refractive error.Combined mechanisms were assigned ifthere were 2 causes ofvision loss.Other causes ofvision loss

included retinal dystrophy, optic atrophy, retinochoroidal scarring,retinitis pigmentosa,myopic retinochoroidal degeneration,and keratoconus.

Foreman et alPrevalence of Vision Loss in Australia

7

loss in Australia’s older population of 5.2% was derived from

the pooled prevalencedatafrom theMelbourneVisual

Impairment Project and the Blue Mountains Eye Study con-

ducted in 1992e1994.43 These surveys were limited in their

geographic coverage,selecting samplesfrom the state of

Victoria and a communitynear Sydney,respectively.

Therefore,the estimates of these studies were representative

of these populationsand could not be confidently

extrapolated to the wider Australian population. Furthermore,

temporalchanges in parameters including population aging

and growth, and a higher prevalence of diabetes risk factors,

have necessitatedupdatedprevalenceestimates.The

prevalence of 6.5% reported in the current study is based on

nationally representative data and should be considered the

mostaccurate estimate ofthe prevalence ofvision loss in

Australia’s non-Indigenous population.Estimates from this

study will be useful for informing future national eye health

policies and may function as the baseline to measure the

progress of future interventions. Of particular relevance is the

association between the increased risk of vision loss and older

age in non-Indigenous participants,with the prevalence of

vision loss more than tripling from ages 60e69 years to 80e89

years.Vision loss also was associated with notundergoing

regular eye examinations reflecting a missed opportunity to

identify and remediate leading causes of vision loss, such as

uncorrected refractiveerrorand cataract.Thesefindings,

considered in lightof the factthatAustralia’s population is

aging rapidly, emphasize the need for individuals to undergo

more regular eye examinations as they age to ensure that the

prevalence of vision loss does not increase in coming decades.

The weighted prevalence ofvision lossof 11.2% for

Indigenous Australians in the NEHS was slightly higher than

thatof the NationalInstitute of EnvironmentalHealth Ser-

vices (10.4%); however, this may be due to the older mean

age of our Indigenouscohort(55 vs. 51 years).More

importantly,the prevalence ofvision losswashigherin

IndigenousAustralianscomparedwith non-Indigenous

Australians residing in all geographic remoteness strata a

in all age groups measured in this study.This underlines

systematic insufficiencies in the delivery of required eye

services to Indigenous communities.51The gap in Indigenous

eye health has been wellestablished,and the Roadmap to

Close the Gap forVision providesa framework forthe

improvementof eye care services.52,53This survey identi-

fied numerousrisk factorsfor vision lossin Indigenous

Australians. The finding that the prevalence of vision loss

Indigenous women was 1.4 times higher than in Indigeno

men highlights the need for further investigation into this

gender disparity and an urgent need to provide equitable

health care to all Indigenous Australians.

The finding that uncorrected refractive error and catar

both reversible, were the main causes of vision loss in bo

Indigenous (81%) and non-Indigenous (75%) participants

reflected in previousAustralian research.24,38,54,55

These

conditions remain the leading causes ofvision loss fora

multitude of reasons that are likely to differ between Indi

nous and non-Indigenous Australians and across different

regions in Australia. For example, the prohibitive distance

spectacle-dispensing services and cataract surgery facilit

coupled with the lack of outreach services, have resulted

insufficientand inequitabletreatmentcoveragefor both

conditions.56 Furthermore,the continuallyincreasing

incidence ofcataract57 and long cataractsurgery waiting

times58 may be further hindering efforts to reduce disease

burden,whereassuboptimalcoordinationof spectacle-

dispensingservices,cost uncertainty,and affordability

particularly for Indigenous Australians51 may contribute to

inadequatetreatmentof refractiveerror.Perhapsmost

importantly, insufficient eye examination frequency in old

Australians may result in a lack of detection and correctio

of refractive error.Consequently,by implementing a well-

coordinated nationwide needs-based strategy thataddresses

thesedeficitswhile increasing eyehealth promotion to

Figure 1.The weighted main causes of vision loss (presenting bilateral distance visual acuity <6/12) in Indigenous and non-Indigenous pa

are the proportion (%; 95% confidence interval [CI]) of vision loss attributed to each main cause. Values are adjusted for sampling weigh

uncorrected or undercorrected refractive error.Combined mechanisms were assigned ifthere were 2 causes ofvision loss.Other causes ofvision loss

included retinal dystrophy, optic atrophy, retinochoroidal scarring,retinitis pigmentosa,myopic retinochoroidal degeneration,and keratoconus.

Foreman et alPrevalence of Vision Loss in Australia

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

improve service use, Australia would successfully supersede

its commitment to the Global Action Plan.

Diabetic retinopathy contributed to 5.2% of vision loss in

Indigenous participants, but less than 1.5% of vision loss in

non-Indigenous participants.This reflects the substantially

higherprevalence ofself-reported diabetes in Indigenous

participants (37.1% vs. 13.9%) and the higher prevalence of

advanced vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy in Indige-

nous Australians that has been attributed to insufficient use

of early detection and treatmentservices.59 Implementing

strategiesto targetrisk factorsfor diabeticretinopathy,

including glycemic,lipid, and blood pressure controlin

Indigenouscommunities,while also enhancing screening

services (supported by the strong association with vision

loss in those who had diabetes and had never had an eye

examination [OR,14.47])may contribute to reducing the

burden of vision loss in Indigenous Australians.52

As the leading cause of blindness (71%) and one of the

leading causes of vision impairmentin Australia and other

high income countries, the burden of AMD as a public health

concern is likely to increase with the aging of the popula-

tion.60 Because the vision loss induced by AMD is largely

irreversible,early detection,treatment,and education on

prevention are critical in slowing disease progression.

Many nationaleye health surveyshaveused Rapid

Assessmentof Avoidable Blindness,Rapid Assessmentof

CataractSurgicalServicesor similarmethodologies.61,62

The strengthsof thesestudy designsare theirrelative

inexpensivenessand thatthey usemultistagesampling

frames,while permitting rapid identification ofobvious

ocular disease.However,their practicalutility is hindered

by a number of weaknesses, including simplified ophthalmic

examinations(often consistingof only slit-lampand

ophthalmoscopy,thereby limiting disease attribution)and

rigid nonstratified sampling methods that do not account for

heterogeneous populations.

Population-based eyesurveysthathaveimplemented

some levelof stratification,howevercrude,have consis-

tently revealed geographic14,15,18

or ethnic34,63,64

variations.

Therefore,it is likely thatnonstratified surveys may not

adequately identify regions and ethnic groups most in need

of improvements in eye healthcare services.Through our

stratifiedsamplingmethodology,in which we have

collectedlarge samplesof both Indigenousand non-

Indigenousparticipantsfrom all levels of geographic

remoteness,we have shown thatthe Indigenous people of

Australia, particularly those living in nonmetropolitan areas,

have a substantially higher risk for vision loss.These find-

ings will strengthen national programs aiming to reduce the

burden of vision loss by assisting policymakers and health

providers to allocate limited resources to communities most

in need.52 On the basis of our findings,future population-

based surveys may benefitfrom using similar stratification

methods to identify and investigate Indigenous groups in

countries with defined Indigenous populations.

Study Limitations

A limitation of this study resulted from Australia’s unique

geographic and population structures, including its unusually

low population density.65A systematic protocol was used to

reducethe risk of bias when selecting new population

clusters imposed by prohibitively low population densitie

high absentee rates, and erroneous census data. Noneth

the completeelimination ofboth nonresponsebias and

selection bias could not be achieved because nonrespond

and absentees may have differed from responders in way

relevantto study outcomes.An additionallimitation is that

the sample size was calculated to detectthe prevalence of

vision loss in general,and the study was notpowered to

achieve precision in the estimates ofthe causes ofvision

loss, the prevalence of vision loss by age, or the presuma

much lowerprevalence ofblindness.Future studies may

benefit from having larger samples,but the benefit must be

weighed against the financial and logistic consequences.

In light of the aim to reduce the prevalence of avoidab

vision loss by 25% before the year 2020 under the Globa

Action Plan,there is an urgentneed for more countries to

conductwell-designed nationaleye health surveys to iden-