A Concept Analysis of the Theory-Practice Gap in Nursing Education

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/05

|24

|7947

|161

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review presents a concept analysis of the theory-practice gap in nursing, utilizing Rodgers' evolutionary process to define and clarify the concept. It addresses the widespread use of the phrase 'theory-practice gap' in nursing literature without a consistent definition. The analysis aims to provide a deeper understanding of the concept for consistent application within nurse education. It details the data search, attributes, antecedents, and consequences of the theory-practice gap. The review identifies attributes such as relational problems between university and clinical practice, practice failing to reflect theory, and theory perceived as irrelevant to practice. Antecedents include issues within university and clinical practice relationships. Consequences include the influence on nurses and nursing students and disparity in collaboration between university and clinical practice. A model case is presented to illustrate the concept, contributing to a standardized understanding and relevance within nursing and nurse education. This analysis highlights the persistent gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, emphasizing the need for collaboration between universities and clinical practice to develop the nursing profession.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329125104

What is a Theory-Practice Gap? An exploration of the concept.

Article in Nurse Education in Practice · November 2018

DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2018.10.005

CITATIONS

0

READS

320

1 author:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

An investigation into the the effects of a theory-practice gap on student nurses' understanding of administering intramuscular injectionsView project

Kathleen Greenway

Oxford Brookes University

7 PUBLICATIONS62CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Kathleen Greenway on 22 November 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

What is a Theory-Practice Gap? An exploration of the concept.

Article in Nurse Education in Practice · November 2018

DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2018.10.005

CITATIONS

0

READS

320

1 author:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

An investigation into the the effects of a theory-practice gap on student nurses' understanding of administering intramuscular injectionsView project

Kathleen Greenway

Oxford Brookes University

7 PUBLICATIONS62CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Kathleen Greenway on 22 November 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1

What is a Theory-Practice Gap? An exploration of the concept.

Abstract

In nursing literature, the phrase ‘theory-practice gap’ is widely used without

common definition or description of its underlying concept. This review paper

presents a concept analysis using Rodgers (2000) evolutionary process to

define and clarify the concept of the theory-practice gap as part of a doctoral

study. In so doing it provides a deeper understanding of the concept to enable

its consistent application within nurse education. A theoretical definition is

developed, the data search that was undertaken is described and a

discussion of the attributes, antecedents and consequences is provided. We

conclude by offering, a model case, which is employed to illustrate the

concept.

Introduction

The primary aim of this doctoral research programme using case study

methodology, was to explore the existence of a theory-practice gap, using

student nurses’ experiences of administering intramuscular injections (IMI)

within their clinical placements as the case. The administration of IMIs forms

part of the essential skills clusters for pre-registration nurses (NMC 2010) and

is one of many skills performed by registered nurses, that may appear to an

onlooker to be an easy skill to execute, yet the practice appears to be fraught

with inconsistencies. The practice to administer an IMI by registered nurses is

not evidence based, which results in a variety of techniques being used

without fully rationalise their practice (Walsh and Brophy 2010). This scenario

can leave students unsure of which method they should use as often what

they are taught in university is not being reflected by their mentors in clinical

practice. This results in a theory-practice gap.

The phrase theory-practice gap is commonly used in nursing literature, often

without consistent definition or description, with the gap regularly referred to

What is a Theory-Practice Gap? An exploration of the concept.

Abstract

In nursing literature, the phrase ‘theory-practice gap’ is widely used without

common definition or description of its underlying concept. This review paper

presents a concept analysis using Rodgers (2000) evolutionary process to

define and clarify the concept of the theory-practice gap as part of a doctoral

study. In so doing it provides a deeper understanding of the concept to enable

its consistent application within nurse education. A theoretical definition is

developed, the data search that was undertaken is described and a

discussion of the attributes, antecedents and consequences is provided. We

conclude by offering, a model case, which is employed to illustrate the

concept.

Introduction

The primary aim of this doctoral research programme using case study

methodology, was to explore the existence of a theory-practice gap, using

student nurses’ experiences of administering intramuscular injections (IMI)

within their clinical placements as the case. The administration of IMIs forms

part of the essential skills clusters for pre-registration nurses (NMC 2010) and

is one of many skills performed by registered nurses, that may appear to an

onlooker to be an easy skill to execute, yet the practice appears to be fraught

with inconsistencies. The practice to administer an IMI by registered nurses is

not evidence based, which results in a variety of techniques being used

without fully rationalise their practice (Walsh and Brophy 2010). This scenario

can leave students unsure of which method they should use as often what

they are taught in university is not being reflected by their mentors in clinical

practice. This results in a theory-practice gap.

The phrase theory-practice gap is commonly used in nursing literature, often

without consistent definition or description, with the gap regularly referred to

2

as being ‘bridged’, ‘breached’, ‘avoided’ or ‘negotiated’. A persistent theory-

practice gap is evident in nursing literature (Rolfe, 2002, Maben et al 2006,

Monaghan, 2015) and frequently mentioned in contemporary research, yet

there is little clarity about its virtual or real characteristics; hence there are

omissions and confusion in our common understanding of this phenomenon.

As a consequence of this lack of consensus a conceptual analysis of the term

was deemed necessary. Walker and Avant (2005) suggest several reasons

for completing a concept analysis, ranging from developing operational

definitions, to clarifying the meaning of an existing concept, to adding to

existing theory. The process for undertaking a concept analysis has been

linked with philosophical inquiry, which in turn uses intellectual analysis to

clarify meaning; moreover in this instance it was crucial as Duncan et al

(2007) argue to embody a shared meaning within a professional discipline to

enable effective communication.

Background

Scully (2011) indicates that despite the differing interpretations of the nature

of the theory-practice gap, there is widespread agreement that it represents

the separation of the practical dimension of nursing from that of theoretical

knowledge (Rolfe 1998, 2002). During the process of completing this concept

analysis it was possible, in the absence of any other given definition, to create

and emergent definition of the theory-practice gap as:

‘The gap between the theoretical knowledge and the practical

application of nursing, most often expressed as a negative entity,

with adverse consequences.’

A definition is important as the theory-practice gap is not tangible; it

represents a metaphorical void which is felt or experienced, yet is not easily

measurable or quantifiable. Consequently, analysis of the components of the

theory-practice gap was expected to produce a classification, a

standardisation of the concept, and an adoption of the common meaning and

relevance to nursing and nurse education.

as being ‘bridged’, ‘breached’, ‘avoided’ or ‘negotiated’. A persistent theory-

practice gap is evident in nursing literature (Rolfe, 2002, Maben et al 2006,

Monaghan, 2015) and frequently mentioned in contemporary research, yet

there is little clarity about its virtual or real characteristics; hence there are

omissions and confusion in our common understanding of this phenomenon.

As a consequence of this lack of consensus a conceptual analysis of the term

was deemed necessary. Walker and Avant (2005) suggest several reasons

for completing a concept analysis, ranging from developing operational

definitions, to clarifying the meaning of an existing concept, to adding to

existing theory. The process for undertaking a concept analysis has been

linked with philosophical inquiry, which in turn uses intellectual analysis to

clarify meaning; moreover in this instance it was crucial as Duncan et al

(2007) argue to embody a shared meaning within a professional discipline to

enable effective communication.

Background

Scully (2011) indicates that despite the differing interpretations of the nature

of the theory-practice gap, there is widespread agreement that it represents

the separation of the practical dimension of nursing from that of theoretical

knowledge (Rolfe 1998, 2002). During the process of completing this concept

analysis it was possible, in the absence of any other given definition, to create

and emergent definition of the theory-practice gap as:

‘The gap between the theoretical knowledge and the practical

application of nursing, most often expressed as a negative entity,

with adverse consequences.’

A definition is important as the theory-practice gap is not tangible; it

represents a metaphorical void which is felt or experienced, yet is not easily

measurable or quantifiable. Consequently, analysis of the components of the

theory-practice gap was expected to produce a classification, a

standardisation of the concept, and an adoption of the common meaning and

relevance to nursing and nurse education.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3

The theory-practice gap has persisted in nursing and continues to have

negative connotations, although its continued presence may facilitate dynamic

change within the profession (Haigh 2008), highlighting the separation

between theoretical or evidence-based knowledge and practical elements of

nursing (Scully 2011). This gap between theory (what should happen), and

what occurs (what actually happens) in the clinical environment is not new.

Yet it is not only the practical skills of new graduate nurses that are

questioned (Voldbjerg et al 2016), it is also the potential lack of proficiency

among nurses in both their clinical skills and critical thinking abilities. Thus the

theory-practice gap remains a continuing problem for nursing, felt both by

experienced and newly qualified and student nurses (Scully 2011). Despite

the more frequently articulated negative associations of the theory-practice

gap, the concept is not always regarded as being resolutely negative. Ousey

has coherently argued, in a debate with Gallagher (Ousey and Gallagher

2007), that the presence of the theory-practice gap can encourage students

and staff to question and thus to avoid complacency in their practice.

Monaghan (2015) suggests as the theory-practice gap begins during pre-

registration education, effecting clinical skills capabilities of student nurses,

collaboration between universities and practice is essential for the

development of the nursing profession.

Method:

Risjord (2009), provides a comprehensive critique of the epistemological

foundations of concept analysis and deems that it can be seen as an arbitrary

and vacuous exercise when it is performed in an unsupported and unjustified

fashion. A concept analysis therefore needs to be undertaken using a

theoretical framework, essential for providing operational definitions.

Traditionally a concept analysis within nursing has used Wilson’s (1963)

method, although many authors have subsequently modified and adapted

Wilson’s framework. Currently, the two most used frameworks within nursing

are those of Walker and Avant (2005) and Rodgers (2000). Walker and

The theory-practice gap has persisted in nursing and continues to have

negative connotations, although its continued presence may facilitate dynamic

change within the profession (Haigh 2008), highlighting the separation

between theoretical or evidence-based knowledge and practical elements of

nursing (Scully 2011). This gap between theory (what should happen), and

what occurs (what actually happens) in the clinical environment is not new.

Yet it is not only the practical skills of new graduate nurses that are

questioned (Voldbjerg et al 2016), it is also the potential lack of proficiency

among nurses in both their clinical skills and critical thinking abilities. Thus the

theory-practice gap remains a continuing problem for nursing, felt both by

experienced and newly qualified and student nurses (Scully 2011). Despite

the more frequently articulated negative associations of the theory-practice

gap, the concept is not always regarded as being resolutely negative. Ousey

has coherently argued, in a debate with Gallagher (Ousey and Gallagher

2007), that the presence of the theory-practice gap can encourage students

and staff to question and thus to avoid complacency in their practice.

Monaghan (2015) suggests as the theory-practice gap begins during pre-

registration education, effecting clinical skills capabilities of student nurses,

collaboration between universities and practice is essential for the

development of the nursing profession.

Method:

Risjord (2009), provides a comprehensive critique of the epistemological

foundations of concept analysis and deems that it can be seen as an arbitrary

and vacuous exercise when it is performed in an unsupported and unjustified

fashion. A concept analysis therefore needs to be undertaken using a

theoretical framework, essential for providing operational definitions.

Traditionally a concept analysis within nursing has used Wilson’s (1963)

method, although many authors have subsequently modified and adapted

Wilson’s framework. Currently, the two most used frameworks within nursing

are those of Walker and Avant (2005) and Rodgers (2000). Walker and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4

Avants’ framework omits the issue of contextualisation which is central within

Rodgers’ (2000) evolutionary framework. Rodgers’ framework emphasises the

dynamic way concepts and theories change over time, or considers when

different contexts are reviewed at the same point in time; thus when the

context of use alters, so must the meaning, focussing on the current

application of the concept and its interconnectedness with other factors. The

theory-practice gap might not only exist in nursing (it might also exist in other

professions such as medicine or teaching, for example) thus the contextual

features and application of Rodgers model, together with its emphasis on

temporal and heuristic elements, was reasoned to provide the most

appropriate framework for this conceptual analysis. The presentation of this

concept analysis will follow the steps as described below in Rodgers’ model.

Steps in Rodgers’ (2000) model

Rodgers (2000) advocates no preconceived descriptions of a concept should

be allowed; instead stating a concept must come from searching the literature

using a systematic technique. Although Rodgers’ model has evolved from

Wilson’s (1963) original 11-step model, it has been refined into an 8-step

process as shown in table 1:

Rodgers' Evolutionary Model

• 1. Identify the concept of interest

• 2. Identify surrogate terms

• 3. Choose the setting and the sample

• 4. Identify the attributes

• 5. Identify the references, antecedents and consequences

• 6. Identify related concepts

• 7. Identify a model case

• 8. Identify implications for further research and development of the concept

Avants’ framework omits the issue of contextualisation which is central within

Rodgers’ (2000) evolutionary framework. Rodgers’ framework emphasises the

dynamic way concepts and theories change over time, or considers when

different contexts are reviewed at the same point in time; thus when the

context of use alters, so must the meaning, focussing on the current

application of the concept and its interconnectedness with other factors. The

theory-practice gap might not only exist in nursing (it might also exist in other

professions such as medicine or teaching, for example) thus the contextual

features and application of Rodgers model, together with its emphasis on

temporal and heuristic elements, was reasoned to provide the most

appropriate framework for this conceptual analysis. The presentation of this

concept analysis will follow the steps as described below in Rodgers’ model.

Steps in Rodgers’ (2000) model

Rodgers (2000) advocates no preconceived descriptions of a concept should

be allowed; instead stating a concept must come from searching the literature

using a systematic technique. Although Rodgers’ model has evolved from

Wilson’s (1963) original 11-step model, it has been refined into an 8-step

process as shown in table 1:

Rodgers' Evolutionary Model

• 1. Identify the concept of interest

• 2. Identify surrogate terms

• 3. Choose the setting and the sample

• 4. Identify the attributes

• 5. Identify the references, antecedents and consequences

• 6. Identify related concepts

• 7. Identify a model case

• 8. Identify implications for further research and development of the concept

5

Concept of interest

Within nursing there is perceived to be a gap between theory and practice

which is persistent and mostly has negative connotations; yet whilst there is

the awareness that it can be felt or experienced, it is not easily measured or

quantifiable. Therefore the theory-practice gap required describing, defining

and exploring; in achieving this it becomes valid for the advancement of the

understanding of the concept within nursing, in both education and practice

(Duncan et al 2007).

Surrogate terms

Rodgers (2000) refers to surrogate terms as being similar or related; those

that can be identified as synonymous to the term theory-practice gap. This

was difficult to quantify as the only other synonym identified was the

‘education-practice gap’ - succinct terms to encompass the void or gulf

between theory and practice were not found. Substitute words such as

‘schism’, ‘gulf’ or ‘dichotomy’, instead of gap, were infrequently used. However

these did not offer a complete, surrogate term, rather they were merely

descriptive, alternative semantics.

Choosing the setting and sample

The keywords for the literature search were derived from the term ‘theory-

practice gap’ and its surrogate term ‘education-practice gap’ using the

CINAHL, BNI, BEI and MEDLINE databases. Limits for English language, for

peer reviewed journals and with a publication date ranging from 2005-2016

were applied. The results were as indicated in Figure 1

Concept of interest

Within nursing there is perceived to be a gap between theory and practice

which is persistent and mostly has negative connotations; yet whilst there is

the awareness that it can be felt or experienced, it is not easily measured or

quantifiable. Therefore the theory-practice gap required describing, defining

and exploring; in achieving this it becomes valid for the advancement of the

understanding of the concept within nursing, in both education and practice

(Duncan et al 2007).

Surrogate terms

Rodgers (2000) refers to surrogate terms as being similar or related; those

that can be identified as synonymous to the term theory-practice gap. This

was difficult to quantify as the only other synonym identified was the

‘education-practice gap’ - succinct terms to encompass the void or gulf

between theory and practice were not found. Substitute words such as

‘schism’, ‘gulf’ or ‘dichotomy’, instead of gap, were infrequently used. However

these did not offer a complete, surrogate term, rather they were merely

descriptive, alternative semantics.

Choosing the setting and sample

The keywords for the literature search were derived from the term ‘theory-

practice gap’ and its surrogate term ‘education-practice gap’ using the

CINAHL, BNI, BEI and MEDLINE databases. Limits for English language, for

peer reviewed journals and with a publication date ranging from 2005-2016

were applied. The results were as indicated in Figure 1

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6

* 88 papers were identified as being duplicates on multiple databases and an

excel spreadsheet was created to list and compare the occurrences of each

paper within the databases searched.

Figure 1 - PRISMA style diagram representing the audit trail of the search

strategy using the Rogerian process.

Records identified through

database searching

(n = 512)

Additional records identified

through snowball sampling

(n = 1)

88 duplicates

removed*

Records screened

(n = 425)

Records excluded

(n = 301)

Full-text articles assessed

for eligibility

(n = 124)

Full-text articles

excluded, with reasons

(n = 0)

Studies included in

concept analysis 20%

representative sample

(n = 26)

* 88 papers were identified as being duplicates on multiple databases and an

excel spreadsheet was created to list and compare the occurrences of each

paper within the databases searched.

Figure 1 - PRISMA style diagram representing the audit trail of the search

strategy using the Rogerian process.

Records identified through

database searching

(n = 512)

Additional records identified

through snowball sampling

(n = 1)

88 duplicates

removed*

Records screened

(n = 425)

Records excluded

(n = 301)

Full-text articles assessed

for eligibility

(n = 124)

Full-text articles

excluded, with reasons

(n = 0)

Studies included in

concept analysis 20%

representative sample

(n = 26)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7

After removal of the duplicates, and the preliminary screening of the abstracts,

a total of 124 papers remained for detailed screening. The papers excluded

by this process mostly referred to ‘bridging’ or ‘overcoming’ the theory-

practice gap, without recourse to defining the term or providing any insight

into the nature of the concept. In accordance with Rodgers’ process of

sampling, 20% of the total results (n=26) were retrieved commencing with a

random starting point to select the literature for inclusion in the analysis. This

was then used as the representative sample to complete the concept

analysis. Whilst the majority of the papers retrieved were research studies,

using Rogerian sampling it is also accepted practice to include any other

cognitive conception of the concept under scrutiny. As concepts are cognitive

conceptions, Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm (2010) concur that data sources can

include professional literature, interviews, or other forms of verbalised

language; several papers which included debates, expressions of personal

experiences or editorial opinions were therefore included in this concept

analysis, though these represent the minority.

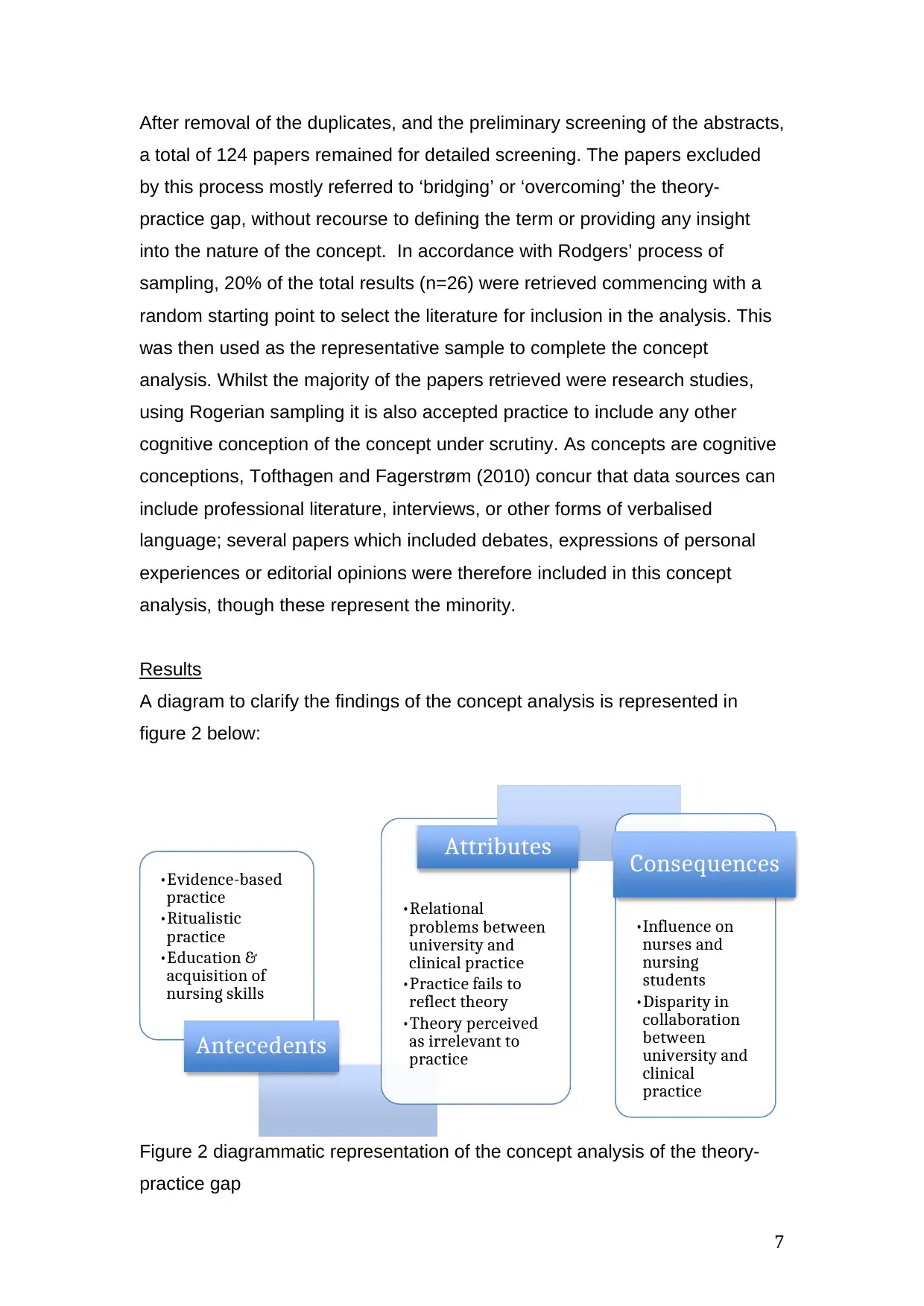

Results

A diagram to clarify the findings of the concept analysis is represented in

figure 2 below:

Figure 2 diagrammatic representation of the concept analysis of the theory-

practice gap

•Evidence-based

practice

•Ritualistic

practice

•Education &

acquisition of

nursing skills

Antecedents

•Relational

problems between

university and

clinical practice

•Practice fails to

reflect theory

•Theory perceived

as irrelevant to

practice

Attributes

•Influence on

nurses and

nursing

students

•Disparity in

collaboration

between

university and

clinical

practice

Consequences

After removal of the duplicates, and the preliminary screening of the abstracts,

a total of 124 papers remained for detailed screening. The papers excluded

by this process mostly referred to ‘bridging’ or ‘overcoming’ the theory-

practice gap, without recourse to defining the term or providing any insight

into the nature of the concept. In accordance with Rodgers’ process of

sampling, 20% of the total results (n=26) were retrieved commencing with a

random starting point to select the literature for inclusion in the analysis. This

was then used as the representative sample to complete the concept

analysis. Whilst the majority of the papers retrieved were research studies,

using Rogerian sampling it is also accepted practice to include any other

cognitive conception of the concept under scrutiny. As concepts are cognitive

conceptions, Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm (2010) concur that data sources can

include professional literature, interviews, or other forms of verbalised

language; several papers which included debates, expressions of personal

experiences or editorial opinions were therefore included in this concept

analysis, though these represent the minority.

Results

A diagram to clarify the findings of the concept analysis is represented in

figure 2 below:

Figure 2 diagrammatic representation of the concept analysis of the theory-

practice gap

•Evidence-based

practice

•Ritualistic

practice

•Education &

acquisition of

nursing skills

Antecedents

•Relational

problems between

university and

clinical practice

•Practice fails to

reflect theory

•Theory perceived

as irrelevant to

practice

Attributes

•Influence on

nurses and

nursing

students

•Disparity in

collaboration

between

university and

clinical

practice

Consequences

8

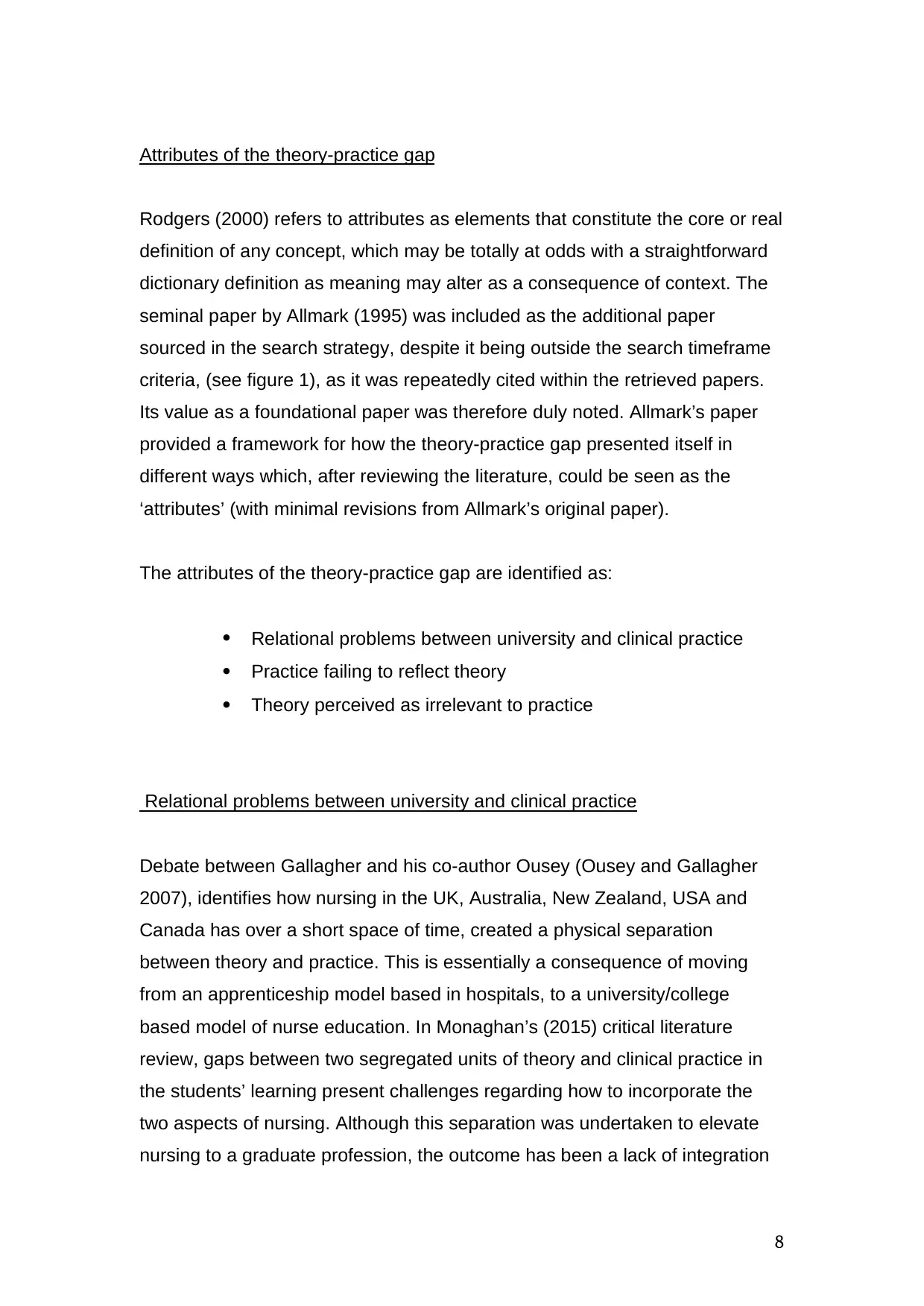

Attributes of the theory-practice gap

Rodgers (2000) refers to attributes as elements that constitute the core or real

definition of any concept, which may be totally at odds with a straightforward

dictionary definition as meaning may alter as a consequence of context. The

seminal paper by Allmark (1995) was included as the additional paper

sourced in the search strategy, despite it being outside the search timeframe

criteria, (see figure 1), as it was repeatedly cited within the retrieved papers.

Its value as a foundational paper was therefore duly noted. Allmark’s paper

provided a framework for how the theory-practice gap presented itself in

different ways which, after reviewing the literature, could be seen as the

‘attributes’ (with minimal revisions from Allmark’s original paper).

The attributes of the theory-practice gap are identified as:

Relational problems between university and clinical practice

Practice failing to reflect theory

Theory perceived as irrelevant to practice

Relational problems between university and clinical practice

Debate between Gallagher and his co-author Ousey (Ousey and Gallagher

2007), identifies how nursing in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, USA and

Canada has over a short space of time, created a physical separation

between theory and practice. This is essentially a consequence of moving

from an apprenticeship model based in hospitals, to a university/college

based model of nurse education. In Monaghan’s (2015) critical literature

review, gaps between two segregated units of theory and clinical practice in

the students’ learning present challenges regarding how to incorporate the

two aspects of nursing. Although this separation was undertaken to elevate

nursing to a graduate profession, the outcome has been a lack of integration

Attributes of the theory-practice gap

Rodgers (2000) refers to attributes as elements that constitute the core or real

definition of any concept, which may be totally at odds with a straightforward

dictionary definition as meaning may alter as a consequence of context. The

seminal paper by Allmark (1995) was included as the additional paper

sourced in the search strategy, despite it being outside the search timeframe

criteria, (see figure 1), as it was repeatedly cited within the retrieved papers.

Its value as a foundational paper was therefore duly noted. Allmark’s paper

provided a framework for how the theory-practice gap presented itself in

different ways which, after reviewing the literature, could be seen as the

‘attributes’ (with minimal revisions from Allmark’s original paper).

The attributes of the theory-practice gap are identified as:

Relational problems between university and clinical practice

Practice failing to reflect theory

Theory perceived as irrelevant to practice

Relational problems between university and clinical practice

Debate between Gallagher and his co-author Ousey (Ousey and Gallagher

2007), identifies how nursing in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, USA and

Canada has over a short space of time, created a physical separation

between theory and practice. This is essentially a consequence of moving

from an apprenticeship model based in hospitals, to a university/college

based model of nurse education. In Monaghan’s (2015) critical literature

review, gaps between two segregated units of theory and clinical practice in

the students’ learning present challenges regarding how to incorporate the

two aspects of nursing. Although this separation was undertaken to elevate

nursing to a graduate profession, the outcome has been a lack of integration

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9

between university and clinical staff in planning the students’ clinical

education. The role of the Lecturer-Practitioner (LP) was created in the 1990s

in the UK with the specific aim of bridging the theory-practice gap. Hancock et

al (2007), in an evaluation study, explored the experiences of LPs and found

that as well as supporting students in practice and providing academic

teaching, their role included the development of clinical skills for newly

qualified nurses. Their joint appointment promoted their clinical credibility and

encouraged stronger links between practice and education. However, Barrett

(2007), in his critical review, states limitations of the LP role resulting in split

loyalties, heavy workloads, unclear career structures and limited effectiveness

of the post holder.

The introduction of joint clinical chairs in nursing, whereby a professorial

position is created as a collaborative appointment between a university and

the healthcare provider, has also been heralded as another means of bridging

the theory-practice gap. Such strategic and operational posts, specifically

designed to straddle the realms of academia and clinical practice, appear

ideally placed to cultivate research and develop clinical practice. Nonetheless,

Darbyshire’s (2010) critical editorial, laments how constant capricious change

within the organisations regarding focus and priorities, fosters the impossibility

of filling these positions - a problem further compounded by a lack of suitable

applicants. This is particularly unfortunate given that Evans (2009), in his

review of mental health nurse training, argues that mutual collaboration

requires a top down leadership approach supporting the two institutions in

developing a joint strategy for student learning.

Hence the roles of LPs and joint chairs were created with the aim of

increasing collaboration between the parties, as well as targeting, influencing

and cascading issues for research or practice. It is apparent that the full

potential of these roles may not yet have been reached.

between university and clinical staff in planning the students’ clinical

education. The role of the Lecturer-Practitioner (LP) was created in the 1990s

in the UK with the specific aim of bridging the theory-practice gap. Hancock et

al (2007), in an evaluation study, explored the experiences of LPs and found

that as well as supporting students in practice and providing academic

teaching, their role included the development of clinical skills for newly

qualified nurses. Their joint appointment promoted their clinical credibility and

encouraged stronger links between practice and education. However, Barrett

(2007), in his critical review, states limitations of the LP role resulting in split

loyalties, heavy workloads, unclear career structures and limited effectiveness

of the post holder.

The introduction of joint clinical chairs in nursing, whereby a professorial

position is created as a collaborative appointment between a university and

the healthcare provider, has also been heralded as another means of bridging

the theory-practice gap. Such strategic and operational posts, specifically

designed to straddle the realms of academia and clinical practice, appear

ideally placed to cultivate research and develop clinical practice. Nonetheless,

Darbyshire’s (2010) critical editorial, laments how constant capricious change

within the organisations regarding focus and priorities, fosters the impossibility

of filling these positions - a problem further compounded by a lack of suitable

applicants. This is particularly unfortunate given that Evans (2009), in his

review of mental health nurse training, argues that mutual collaboration

requires a top down leadership approach supporting the two institutions in

developing a joint strategy for student learning.

Hence the roles of LPs and joint chairs were created with the aim of

increasing collaboration between the parties, as well as targeting, influencing

and cascading issues for research or practice. It is apparent that the full

potential of these roles may not yet have been reached.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10

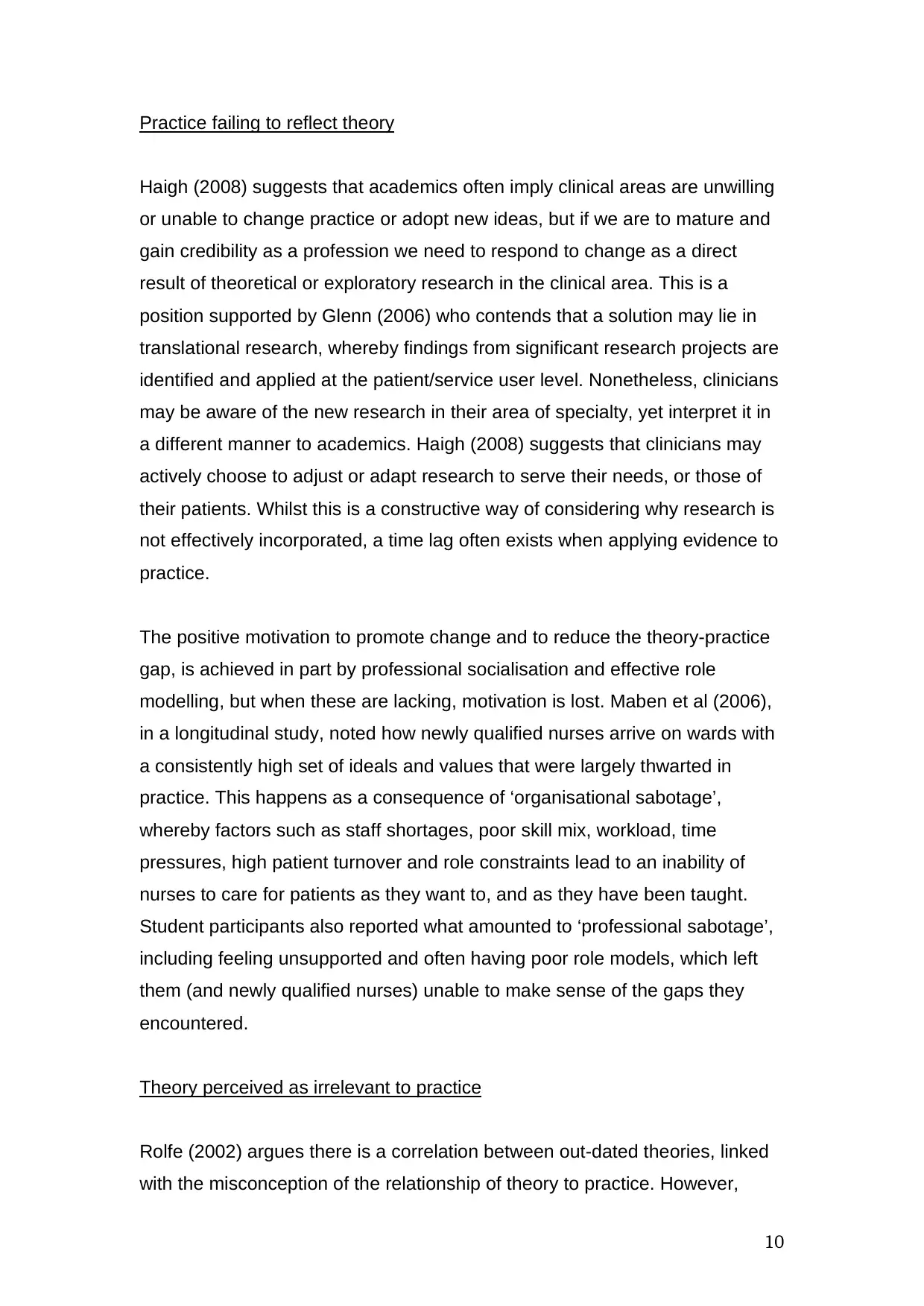

Practice failing to reflect theory

Haigh (2008) suggests that academics often imply clinical areas are unwilling

or unable to change practice or adopt new ideas, but if we are to mature and

gain credibility as a profession we need to respond to change as a direct

result of theoretical or exploratory research in the clinical area. This is a

position supported by Glenn (2006) who contends that a solution may lie in

translational research, whereby findings from significant research projects are

identified and applied at the patient/service user level. Nonetheless, clinicians

may be aware of the new research in their area of specialty, yet interpret it in

a different manner to academics. Haigh (2008) suggests that clinicians may

actively choose to adjust or adapt research to serve their needs, or those of

their patients. Whilst this is a constructive way of considering why research is

not effectively incorporated, a time lag often exists when applying evidence to

practice.

The positive motivation to promote change and to reduce the theory-practice

gap, is achieved in part by professional socialisation and effective role

modelling, but when these are lacking, motivation is lost. Maben et al (2006),

in a longitudinal study, noted how newly qualified nurses arrive on wards with

a consistently high set of ideals and values that were largely thwarted in

practice. This happens as a consequence of ‘organisational sabotage’,

whereby factors such as staff shortages, poor skill mix, workload, time

pressures, high patient turnover and role constraints lead to an inability of

nurses to care for patients as they want to, and as they have been taught.

Student participants also reported what amounted to ‘professional sabotage’,

including feeling unsupported and often having poor role models, which left

them (and newly qualified nurses) unable to make sense of the gaps they

encountered.

Theory perceived as irrelevant to practice

Rolfe (2002) argues there is a correlation between out-dated theories, linked

with the misconception of the relationship of theory to practice. However,

Practice failing to reflect theory

Haigh (2008) suggests that academics often imply clinical areas are unwilling

or unable to change practice or adopt new ideas, but if we are to mature and

gain credibility as a profession we need to respond to change as a direct

result of theoretical or exploratory research in the clinical area. This is a

position supported by Glenn (2006) who contends that a solution may lie in

translational research, whereby findings from significant research projects are

identified and applied at the patient/service user level. Nonetheless, clinicians

may be aware of the new research in their area of specialty, yet interpret it in

a different manner to academics. Haigh (2008) suggests that clinicians may

actively choose to adjust or adapt research to serve their needs, or those of

their patients. Whilst this is a constructive way of considering why research is

not effectively incorporated, a time lag often exists when applying evidence to

practice.

The positive motivation to promote change and to reduce the theory-practice

gap, is achieved in part by professional socialisation and effective role

modelling, but when these are lacking, motivation is lost. Maben et al (2006),

in a longitudinal study, noted how newly qualified nurses arrive on wards with

a consistently high set of ideals and values that were largely thwarted in

practice. This happens as a consequence of ‘organisational sabotage’,

whereby factors such as staff shortages, poor skill mix, workload, time

pressures, high patient turnover and role constraints lead to an inability of

nurses to care for patients as they want to, and as they have been taught.

Student participants also reported what amounted to ‘professional sabotage’,

including feeling unsupported and often having poor role models, which left

them (and newly qualified nurses) unable to make sense of the gaps they

encountered.

Theory perceived as irrelevant to practice

Rolfe (2002) argues there is a correlation between out-dated theories, linked

with the misconception of the relationship of theory to practice. However,

11

other authors (Maben et al 2006, Ousey and Gallagher 2007) suggest the

fault lies with the lack of socialisation of the theories into the clinical setting

and the failure to integrate research into the clinical practice environment.

Haigh (2008) suggests this aspect of the theory-practice gap should be

embraced, not despised. The dynamic and evolving nature of nursing implies

old theories will become irrelevant whilst new theories and skills being

developed, will require testing and evaluation. When new skills or theories are

accepted, or well evaluated, there is a need to cascade into the global nursing

network. It is therefore inevitable that a gap is experienced until such time as

the transfer of knowledge or skills is complete.

Additionally, as nurse education is split between clinical practice and the

university, there is a need to prioritise applying theory in context specific and

workable ways. The use of human patient simulators (HPS) within a simulated

based education (SBE) to provide a more realistic yet controlled classroom

environment has been advocated as a way of making skills learning more

representative of the contextual realities of everyday clinical practice. The

claim university lecturers are out of touch with reality, not clinically credible

and that the theories they espouse do not reflect practice, opposes the

previous position. Ousey and Gallagher (2010) refute this statement in their

debate regarding the clinical credibility of nurse educators. They argue

maintaining such credibility is not of paramount importance, stating that this is

an unrealistic expectation of lecturers given their pressure of work and

requirement to display competence so to remain on the professional register.

Ousey and Gallagher (2010) find this debate to be an unnecessary

distraction, arguing that emphasis should be on partnership between

academia and clinical practice, whilst the issue of clinical credibility should

instead be focused on the mentor in practice. Myall et al (2008) have declared

effective mentorship to be pivotal to students’ clinical learning experiences;

this is of particular importance as mentors provide the summative assessment

of a student’s clinical practice. Therefore, the need for a competent, clinically

credible, research aware and reflective mentor is extremely desirable. Indeed,

this is increasingly regarded as essential for the effective professional

other authors (Maben et al 2006, Ousey and Gallagher 2007) suggest the

fault lies with the lack of socialisation of the theories into the clinical setting

and the failure to integrate research into the clinical practice environment.

Haigh (2008) suggests this aspect of the theory-practice gap should be

embraced, not despised. The dynamic and evolving nature of nursing implies

old theories will become irrelevant whilst new theories and skills being

developed, will require testing and evaluation. When new skills or theories are

accepted, or well evaluated, there is a need to cascade into the global nursing

network. It is therefore inevitable that a gap is experienced until such time as

the transfer of knowledge or skills is complete.

Additionally, as nurse education is split between clinical practice and the

university, there is a need to prioritise applying theory in context specific and

workable ways. The use of human patient simulators (HPS) within a simulated

based education (SBE) to provide a more realistic yet controlled classroom

environment has been advocated as a way of making skills learning more

representative of the contextual realities of everyday clinical practice. The

claim university lecturers are out of touch with reality, not clinically credible

and that the theories they espouse do not reflect practice, opposes the

previous position. Ousey and Gallagher (2010) refute this statement in their

debate regarding the clinical credibility of nurse educators. They argue

maintaining such credibility is not of paramount importance, stating that this is

an unrealistic expectation of lecturers given their pressure of work and

requirement to display competence so to remain on the professional register.

Ousey and Gallagher (2010) find this debate to be an unnecessary

distraction, arguing that emphasis should be on partnership between

academia and clinical practice, whilst the issue of clinical credibility should

instead be focused on the mentor in practice. Myall et al (2008) have declared

effective mentorship to be pivotal to students’ clinical learning experiences;

this is of particular importance as mentors provide the summative assessment

of a student’s clinical practice. Therefore, the need for a competent, clinically

credible, research aware and reflective mentor is extremely desirable. Indeed,

this is increasingly regarded as essential for the effective professional

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 24

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.