HI5017 Managerial Accounting: Time-Driven vs. Driver Rate-Based ABC

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|11

|6252

|189

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an in-depth analysis of Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) and Driver Rate-Based Activity-Based Costing (DRBABC) methods, addressing the ongoing debate about which method is superior for assigning costs. It clarifies the differences between the 'push' and 'pull' approaches in costing, emphasizing that the choice between Time-Driven and Driver Rate-Based methods is independent of the push-pull decision. The report contrasts these methods, highlighting that both are superior to simplistic cost allocation practices. It details the mechanics of both DRBABC and TDABC, including push and pull examples, and discusses the conditions under which each method is most suitable, particularly focusing on how TDABC can provide superior information by leveraging time equations and multiple drivers to capture cost object variability. The report uses examples to illustrate the practical application of both costing methods and their impact on capacity utilization and cost recovery.

TIME-DRIVEN

OR

DRIVER

RATE-BASED

ABC:

HOW DO

YOU

CHOOSE?

OR

DRIVER

RATE-BASED

ABC:

HOW DO

YOU

CHOOSE?

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

February 2016 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ 21

By GARY COKINS, CPIM, AND DOUGLAS D. PAUL

By GARY COKINS, CPIM, AND DOUGLAS D. PAUL

22 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ February 2016

debate has been going on for years about

which method of activity-based costing

(ABC) is better to use for assigning costs:

Time-Driven or Driver Rate-Based. The

answer: It depends on the circum-

stances. There’s a great deal of confusion

regarding which one to use and around

terms such as “push” vs. “pull” and “top-

down” vs. “bottom-up” in which the latter perspective of

both terms is one where a product isn’t consuming all of the

supplied capacity expenses, and the former perspective is

one where the capacity expense, including unused or idle

capacity, is being fully traced into the product, thus over-

costing products. This raises several questions: How are the

approaches similar? How are they different? Is one method

superior to the other? Can a company start with the former

method and transition to the latter method as informational

needs increase? What are the conditions when one or the

other method might suffice?

To discuss the merits, we need a starting point to estab-

lish clarification. It’s an incorrect simplification to refer to

Time-Driven ABC (TDABC) as the “pull” basis and its pred-

ecessor, the conventional Driver Rate-Based ABC

(DRBABC), as the “push” approach. The decisions to use the

push vs. pull or Time-Driven vs. Driver Rate-Based method

are independent of each other, so their merits should be

evaluated independently. Figure 1 displays a two-by-two

matrix where either method can be used with either a push

or pull approach.

Before contrasting and debating these two methods, we

want to emphasize that both types of ABC methods

described in this article are vastly superior to the common

and misleading practice of allocating indirect and shared

expenses (i.e., overhead) using a single “cost pool” and its

associated “cost allocation factor.” Such a practice violates

costing’s “causality principle,” which is “the relation

between a managerial objective’s quantitative output and

the input quantities consumed if the output is to be

achieved.” (See “The Conceptual Framework for Managerial

Costing” by Larry R. White and B. Douglas Clinton at

www.imanet.org/MCCF.) Simple cost allocation factors

(e.g., number of input labor/machine minutes, units pro-

duced, units sold, full-time equivalent employees, and

square feet) don’t reflect a proportional relationship of the

product cost and the work activity costs it consumes. Using

simplistic factors is often referred to as “peanut butter

spreading” with broad noncausal relationship averages that

result in inaccurate costs.

Before diving deeper, we want to make a comment

about expenses and costs. We view them as different things.

Expenses are defined as when an organization exchanges

money with third parties, such as paying suppliers or pay-

ing employees’ salaries. An expense is synonymous with

“spending” to acquire resources. Examples of resource

expenses are salaries, supplies, electrical power, or pur-

chased components. (Expenses may also be “near-cash” to

reflect the obligation to pay cash in the near future.) In

short, with expenses, currency exits the treasury bank

account. In contrast, costs reflect the consumption of the

spending of the expenses. They are always “calculated”

using modeling, and modeling translates expenses into

costs.

THE ASSIGNMENT METHOD

VS. ABSORPTION-TYPE

MATRIX

For the “Absorption Type” rows in Figure 1, the terms push

vs. pull refer to whether all of the expenses incurred are

fully allocated (pushed) to products as product costs or

whether only a measurement of the consumed amount of

those expenses is pulled into the products.

For the “Assignment Method” columns, the terms Time-

Driven vs. Driver Rate-Based represent a unit of method

cost assignment difference: time vs. quantities. We want to

make it clear that either assignment method can be used

with either absorption type.

This article describes both the Time-Driven and the

Driver Rate-Based methods and the push vs. pull

approaches and their respective merits. It also describes the

conditions where a Time-Driven cost assignment method

A

Figure 1

TWO-BY-TWO MATRIX

ABSORPTION TYPE

ASSIGNMENT METHOD

TIME-DRIVEN DRIVER RATE-BASED

4 4

4 4

FULL (PUSH)

PARTIAL (PULL)

ASSIGNMENT METHOD

debate has been going on for years about

which method of activity-based costing

(ABC) is better to use for assigning costs:

Time-Driven or Driver Rate-Based. The

answer: It depends on the circum-

stances. There’s a great deal of confusion

regarding which one to use and around

terms such as “push” vs. “pull” and “top-

down” vs. “bottom-up” in which the latter perspective of

both terms is one where a product isn’t consuming all of the

supplied capacity expenses, and the former perspective is

one where the capacity expense, including unused or idle

capacity, is being fully traced into the product, thus over-

costing products. This raises several questions: How are the

approaches similar? How are they different? Is one method

superior to the other? Can a company start with the former

method and transition to the latter method as informational

needs increase? What are the conditions when one or the

other method might suffice?

To discuss the merits, we need a starting point to estab-

lish clarification. It’s an incorrect simplification to refer to

Time-Driven ABC (TDABC) as the “pull” basis and its pred-

ecessor, the conventional Driver Rate-Based ABC

(DRBABC), as the “push” approach. The decisions to use the

push vs. pull or Time-Driven vs. Driver Rate-Based method

are independent of each other, so their merits should be

evaluated independently. Figure 1 displays a two-by-two

matrix where either method can be used with either a push

or pull approach.

Before contrasting and debating these two methods, we

want to emphasize that both types of ABC methods

described in this article are vastly superior to the common

and misleading practice of allocating indirect and shared

expenses (i.e., overhead) using a single “cost pool” and its

associated “cost allocation factor.” Such a practice violates

costing’s “causality principle,” which is “the relation

between a managerial objective’s quantitative output and

the input quantities consumed if the output is to be

achieved.” (See “The Conceptual Framework for Managerial

Costing” by Larry R. White and B. Douglas Clinton at

www.imanet.org/MCCF.) Simple cost allocation factors

(e.g., number of input labor/machine minutes, units pro-

duced, units sold, full-time equivalent employees, and

square feet) don’t reflect a proportional relationship of the

product cost and the work activity costs it consumes. Using

simplistic factors is often referred to as “peanut butter

spreading” with broad noncausal relationship averages that

result in inaccurate costs.

Before diving deeper, we want to make a comment

about expenses and costs. We view them as different things.

Expenses are defined as when an organization exchanges

money with third parties, such as paying suppliers or pay-

ing employees’ salaries. An expense is synonymous with

“spending” to acquire resources. Examples of resource

expenses are salaries, supplies, electrical power, or pur-

chased components. (Expenses may also be “near-cash” to

reflect the obligation to pay cash in the near future.) In

short, with expenses, currency exits the treasury bank

account. In contrast, costs reflect the consumption of the

spending of the expenses. They are always “calculated”

using modeling, and modeling translates expenses into

costs.

THE ASSIGNMENT METHOD

VS. ABSORPTION-TYPE

MATRIX

For the “Absorption Type” rows in Figure 1, the terms push

vs. pull refer to whether all of the expenses incurred are

fully allocated (pushed) to products as product costs or

whether only a measurement of the consumed amount of

those expenses is pulled into the products.

For the “Assignment Method” columns, the terms Time-

Driven vs. Driver Rate-Based represent a unit of method

cost assignment difference: time vs. quantities. We want to

make it clear that either assignment method can be used

with either absorption type.

This article describes both the Time-Driven and the

Driver Rate-Based methods and the push vs. pull

approaches and their respective merits. It also describes the

conditions where a Time-Driven cost assignment method

A

Figure 1

TWO-BY-TWO MATRIX

ABSORPTION TYPE

ASSIGNMENT METHOD

TIME-DRIVEN DRIVER RATE-BASED

4 4

4 4

FULL (PUSH)

PARTIAL (PULL)

ASSIGNMENT METHOD

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

February 2016 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ 23

provides superior information compared to

the Driver Rate-Based method.

Push vs. Pull

A push approach to costing means full

absorption in which 100% of the expenses

incurred during a time period are assigned

to the activities performed, and all of those

activity costs are in turn reassigned to the

recipients or “cost objects” that consume

them. All expenses are accounted for in

which the expenses collected in the Gen-

eral Ledger (GL) accounting system (pri-

marily from payments for purchases,

employee payroll, and accrual-type journal

entries like depreciation) equal the total

amount when adding up all of the activity

costs and the ultimate final cost object

costs. Examples of final cost objects are

products, standard service lines, types of

orders (e.g., special vs. standard or domes-

tic vs. international), channels, customers,

and business-sustaining cost objects. Other

more advanced examples of final cost

objects can include individual orders and

order lines, shipments, deliveries, medical

patient encounters (such as a visit to the

doctor), or any other type of individual

customer-related transactions. Business-

sustaining cost objects are those that aren’t

related to making products, distributing

them, or serving customers. Some people

may consider them cost assignments from

support departments (e.g., legal expenses)

and not include them with the other final

cost objects just mentioned.

The push approach proportionately

traces costs based on consumption rela-

tionships and is like a complete electrical

circuit from the provider to the receiver.

The benefit of this approach is that there’s

a 100% complete reconciliation of the

expenses to the officially reported financial

results in total. Therefore, the cost amounts

are credible overall and reasonably accu-

rate. With the push approach, estimates of

driver quantities are acceptable since each

assignment must normalize to 100%.

A downside of the push approach is

that the supplier of the resource capacity

expenses (i.e., the “sending” spender of

expenses) always recovers 100% of its

incurred expenses. Therefore, if a support

group such as information technology (IT)

or Finance spends more than its budget, it

becomes the receiving internal depart-

ment’s problem, not theirs. This doesn’t

provide an incentive to the support group

to reduce its expenses. For example, if

resources were added or paid overtime by

WHAT IS DRBABC?

Driver Rate-Based Activity-Based Costing (DRBABC) is

representative of the Activity-Based Costing (ABC) methodology that h

been formally in use to various degrees since the 1980s. It is based on

concept that assignment of costs has grown in importance because of

ever-increasing proportion of indirect and shared support expenses to

total, which, in large part, has been caused by the emergence of great

variation and complexity of product and service offerings.

DRBABC leverages operating metrics as meaningful drivers to assign

costs to “cost objects,” be they products, services, channels, or

customers. Typically, a single driver is employed in any given cost

assignment, and it’s a driver that replaces volume, revenue, or otherw

simplistic approaches.

DRBABC provides substantially higher cost accuracy compared to

traditional costing by capturing the effects of output diversity and

complexity as well as volume.

WHAT IS TDABC?Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) is a costing

method that reflects the supply and demand for costs and capacity th

leverages estimated unit times to calculate time as a driver in lieu of a

single driver quantity. It employs a multidriver approach to obtain an e

greater level of distinction and variability of cost between different cos

objects than DRBABC.

TDABC typically calculates costs to a more granular level, such as

transaction, invoice, order, order line, shipment, or shipment line. With

TDABC, a total time is calculated based on the rendering of an algorith

also known as a “time equation,” on every cost object record. This tim

equation allows the use of multiple drivers (as opposed to the single

DRBABC driver) with if/then logic, thus providing the flexibility to captu

more nuance and variability of a cost object’s behavior.

The TDABC methodology was presented by Steven R. Anderson and

Robert S. Kaplan in November 2004 in their article, “Time-Driven Activ

Based Costing” (Harvard Business Review, Volume 82, No. 11). The two

expanded their views in their 2007 book,Time-Driven Activity-Based

Costing, published by the Harvard Business School Press.

provides superior information compared to

the Driver Rate-Based method.

Push vs. Pull

A push approach to costing means full

absorption in which 100% of the expenses

incurred during a time period are assigned

to the activities performed, and all of those

activity costs are in turn reassigned to the

recipients or “cost objects” that consume

them. All expenses are accounted for in

which the expenses collected in the Gen-

eral Ledger (GL) accounting system (pri-

marily from payments for purchases,

employee payroll, and accrual-type journal

entries like depreciation) equal the total

amount when adding up all of the activity

costs and the ultimate final cost object

costs. Examples of final cost objects are

products, standard service lines, types of

orders (e.g., special vs. standard or domes-

tic vs. international), channels, customers,

and business-sustaining cost objects. Other

more advanced examples of final cost

objects can include individual orders and

order lines, shipments, deliveries, medical

patient encounters (such as a visit to the

doctor), or any other type of individual

customer-related transactions. Business-

sustaining cost objects are those that aren’t

related to making products, distributing

them, or serving customers. Some people

may consider them cost assignments from

support departments (e.g., legal expenses)

and not include them with the other final

cost objects just mentioned.

The push approach proportionately

traces costs based on consumption rela-

tionships and is like a complete electrical

circuit from the provider to the receiver.

The benefit of this approach is that there’s

a 100% complete reconciliation of the

expenses to the officially reported financial

results in total. Therefore, the cost amounts

are credible overall and reasonably accu-

rate. With the push approach, estimates of

driver quantities are acceptable since each

assignment must normalize to 100%.

A downside of the push approach is

that the supplier of the resource capacity

expenses (i.e., the “sending” spender of

expenses) always recovers 100% of its

incurred expenses. Therefore, if a support

group such as information technology (IT)

or Finance spends more than its budget, it

becomes the receiving internal depart-

ment’s problem, not theirs. This doesn’t

provide an incentive to the support group

to reduce its expenses. For example, if

resources were added or paid overtime by

WHAT IS DRBABC?

Driver Rate-Based Activity-Based Costing (DRBABC) is

representative of the Activity-Based Costing (ABC) methodology that h

been formally in use to various degrees since the 1980s. It is based on

concept that assignment of costs has grown in importance because of

ever-increasing proportion of indirect and shared support expenses to

total, which, in large part, has been caused by the emergence of great

variation and complexity of product and service offerings.

DRBABC leverages operating metrics as meaningful drivers to assign

costs to “cost objects,” be they products, services, channels, or

customers. Typically, a single driver is employed in any given cost

assignment, and it’s a driver that replaces volume, revenue, or otherw

simplistic approaches.

DRBABC provides substantially higher cost accuracy compared to

traditional costing by capturing the effects of output diversity and

complexity as well as volume.

WHAT IS TDABC?Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) is a costing

method that reflects the supply and demand for costs and capacity th

leverages estimated unit times to calculate time as a driver in lieu of a

single driver quantity. It employs a multidriver approach to obtain an e

greater level of distinction and variability of cost between different cos

objects than DRBABC.

TDABC typically calculates costs to a more granular level, such as

transaction, invoice, order, order line, shipment, or shipment line. With

TDABC, a total time is calculated based on the rendering of an algorith

also known as a “time equation,” on every cost object record. This tim

equation allows the use of multiple drivers (as opposed to the single

DRBABC driver) with if/then logic, thus providing the flexibility to captu

more nuance and variability of a cost object’s behavior.

The TDABC methodology was presented by Steven R. Anderson and

Robert S. Kaplan in November 2004 in their article, “Time-Driven Activ

Based Costing” (Harvard Business Review, Volume 82, No. 11). The two

expanded their views in their 2007 book,Time-Driven Activity-Based

Costing, published by the Harvard Business School Press.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

24 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ February 2016

$ # Invoices Rate $ # Invoices Rate

Salaries $100,000 $98,000

Benefits $30,000 $28,900

Training $7,000 $4,200

Travel $8,000 $3,000

Allocations In $20,000 $19,800

Subtotal - All Costs In $$1$16$165$165,$165,0$165,00$165,000$165,000 $153,900

Customer 1 $41,420 33,136 $1.25 $41,820 33,456 $1.25

Customer 2 $39,420 31,536 $1.25 $61,155 48,924 $1.25

Customer 3 $36,545 29,236 $1.25 $34,016 27,213 $1.25

Customer 4 $34,920 27,936 $1.25 $20,918 16,734 $1.25

Subtotal - Recovery to Customers $

$165,000

$1

$165,000

$15

$165,000

$152

$165,000

$152,

$165,000

$152,3

$165,000

$152,30

$165,000

$152,305

$165,000

$152,305 121,844 $1.25 $157,909 126,327 $1.25

Net Over/(Under) Recovery (

$165,000

$152,305

($

$165,000

$152,305

($1

$165,000

$152,305

($12

$165,000

$152,305

($12,

$165,000

$152,305

($12,6

$165,000

$152,305

($12,69

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695) $4,009

Capacity Utilization (Recovery/Total Spent) 9

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92.

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92.3

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92.3%

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92.3% 102.6%

January February

Accounts Receivable Department

Activity - Manage Invoices

$ # Invoices Driver % Net Rate $ # Invoices Driver % Net Rate

Salaries $100,000 $98,000

Benefits $30,000 $28,900

Training $7,000 $4,200

Travel $8,000 $3,000

Allocations In $20,000 $19,800

Subtotal - All Costs In $$1$16$165$165,$165,0$165,00$165,000$165,000 $153,900

Customer 1 $44,872 33,136 27.2% $1.35 $40,758 33,456 26.5% $1.22

Customer 2 $42,706 31,536 25.9% $1.35 $59,602 48,924 38.7% $1.22

Customer 3 $39,591 29,236 24.0% $1.35 $33,153 27,213 21.5% $1.22

Customer 4 $37,831 27,936 22.9% $1.35 $20,386 16,734 13.2% $1.22

Subtotal - Recovery to Customers $

$165,000

$1

$165,000

$16

$165,000

$165

$165,000

$165,

$165,000

$165,0

$165,000

$165,00

$165,000

$165,000

$165,000

$165,000 121,844 100% $1.35 $153,900 126,327 $1.22

Net Over/(Under) Recovery $

$165,000

$165,000

$0

$165,000

$165,000

$0 $0

Capacity Utilization (Recovery/Total Spent) 1

$165,000

$165,000

$0

10

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100.

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100.0

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100.0%

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100.0% 100.0%

Accounts Receivable Department

Activity - Manage Invoices

January February

Department Activity Period Amount Time Equation

Accounts Receivable Manage Invoices January $$1$16$165$165,$165,0$165,00$165,000$165,000 If [Invoice].[Order Type]="Web", Then 1 Else if [Invoice].[Order Type]="Fax" Then 5 Else 8

Headcount Hours Per Head Available Hours Available Minutes

65 8 10,400 624,000 Invoice ID Business Group ID Order Type Count Time Cost

2016-01-000001 Customer 1 Web 1 1 $0.30

2016-01-000002 Customer 2 Web 1 1 $0.30

2016-01-000003 Customer 3 Fax 1 5 $1.49

2016-01-000004 Customer 1 Phone 1 8 $2.39

2016-01-000005 Customer 4 Web 1 1 $0.30

2016-01-000006 Customer 2 Phone 1 8 $2.39

2016-01-000007 Customer 4 Web 1 1 $0.30

……. Customer 1 Web 15,078 15,078 $4,506.19

……. Customer 2 Web 13,078 13,078 $3,908.47

$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000

……. Customer 3 Web 8,578 8,578 $2,563.61

……. Customer 4 Web 11,078 11,078 $3,310.75

……. Customer 1 Fax 8,078 40,390 $12,070.89

……. Customer 2 Fax 7,078 35,390 $10,576.60

……. Customer 3 Fax 7,578 37,890 $11,323.74

……. Customer 4 Fax 6,578 32,890 $9,829.45

……. Customer 1 Phone 9,978 79,824 $23,856.07

……. Customer 2 Phone 11,378 91,024 $27,203.28

……. Customer 3 Phone 13,078 104,624 $31,267.76

……. Customer 4 Phone 10,278 82,224 $24,573.33

2016-01-121843 Customer 3 Phone 1 8 $2.39

Total 121,844 552,101 $

$165,000

$1

$165,000

$16

$165,000

$165

$165,000

$165,

$165,000

$165,0

$165,000

$165,00

$165,000

$165,000

$165,000

$165,000

Capacity Utilization (Total Time/Available Minutes) 8

$165,000

$165,000

88

$165,000

$165,000

88.

$165,000

$165,000

88.5

$165,000

$165,000

88.5%

$165,000

$165,000

88.5%

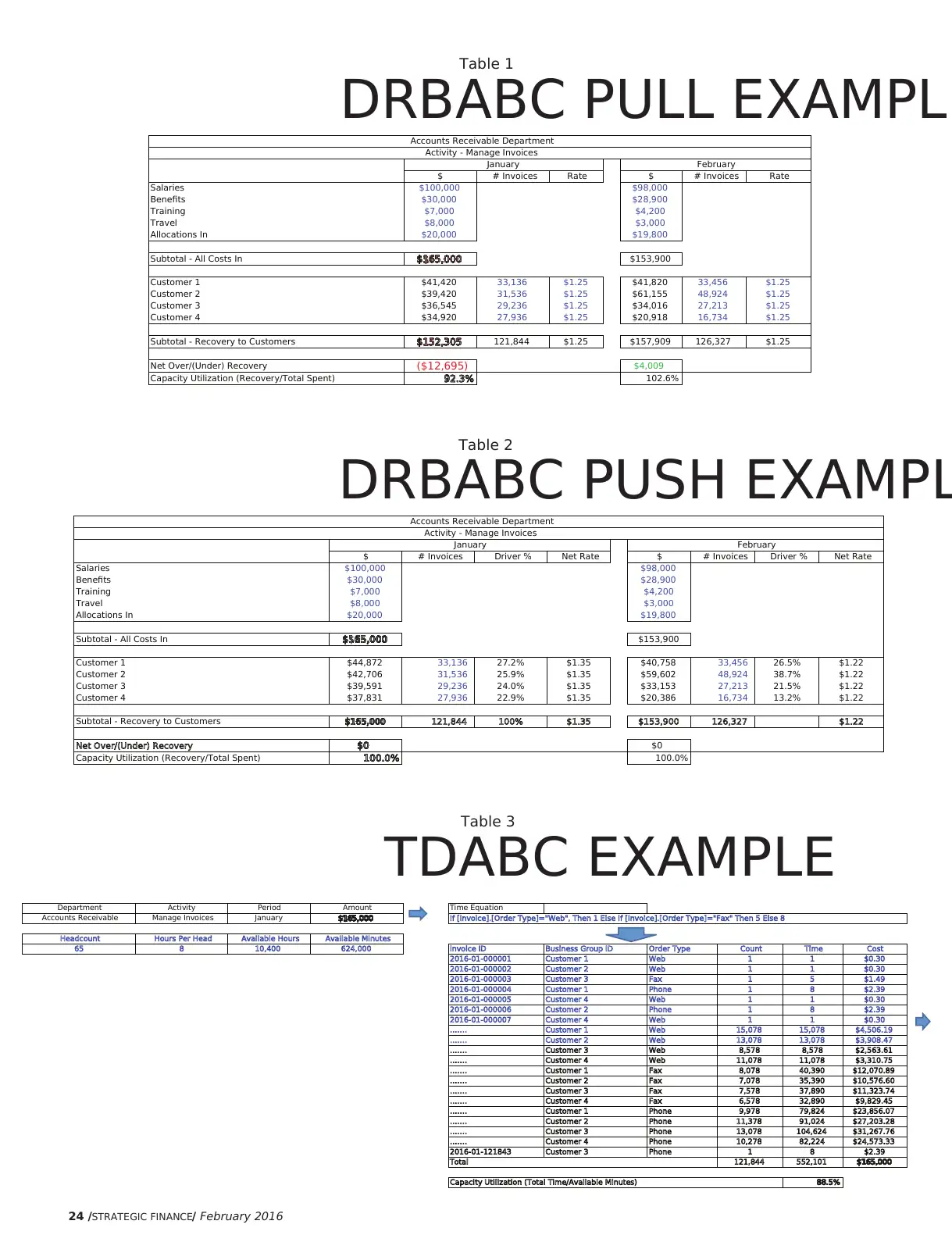

Table 1

DRBABC PULL EXAMPLE

Table 2

DRBABC PUSH EXAMPL

Table 3

TDABC EXAMPLE

($12,695)

$ # Invoices Rate $ # Invoices Rate

Salaries $100,000 $98,000

Benefits $30,000 $28,900

Training $7,000 $4,200

Travel $8,000 $3,000

Allocations In $20,000 $19,800

Subtotal - All Costs In $$1$16$165$165,$165,0$165,00$165,000$165,000 $153,900

Customer 1 $41,420 33,136 $1.25 $41,820 33,456 $1.25

Customer 2 $39,420 31,536 $1.25 $61,155 48,924 $1.25

Customer 3 $36,545 29,236 $1.25 $34,016 27,213 $1.25

Customer 4 $34,920 27,936 $1.25 $20,918 16,734 $1.25

Subtotal - Recovery to Customers $

$165,000

$1

$165,000

$15

$165,000

$152

$165,000

$152,

$165,000

$152,3

$165,000

$152,30

$165,000

$152,305

$165,000

$152,305 121,844 $1.25 $157,909 126,327 $1.25

Net Over/(Under) Recovery (

$165,000

$152,305

($

$165,000

$152,305

($1

$165,000

$152,305

($12

$165,000

$152,305

($12,

$165,000

$152,305

($12,6

$165,000

$152,305

($12,69

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695) $4,009

Capacity Utilization (Recovery/Total Spent) 9

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92.

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92.3

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92.3%

$165,000

$152,305

($12,695)

92.3% 102.6%

January February

Accounts Receivable Department

Activity - Manage Invoices

$ # Invoices Driver % Net Rate $ # Invoices Driver % Net Rate

Salaries $100,000 $98,000

Benefits $30,000 $28,900

Training $7,000 $4,200

Travel $8,000 $3,000

Allocations In $20,000 $19,800

Subtotal - All Costs In $$1$16$165$165,$165,0$165,00$165,000$165,000 $153,900

Customer 1 $44,872 33,136 27.2% $1.35 $40,758 33,456 26.5% $1.22

Customer 2 $42,706 31,536 25.9% $1.35 $59,602 48,924 38.7% $1.22

Customer 3 $39,591 29,236 24.0% $1.35 $33,153 27,213 21.5% $1.22

Customer 4 $37,831 27,936 22.9% $1.35 $20,386 16,734 13.2% $1.22

Subtotal - Recovery to Customers $

$165,000

$1

$165,000

$16

$165,000

$165

$165,000

$165,

$165,000

$165,0

$165,000

$165,00

$165,000

$165,000

$165,000

$165,000 121,844 100% $1.35 $153,900 126,327 $1.22

Net Over/(Under) Recovery $

$165,000

$165,000

$0

$165,000

$165,000

$0 $0

Capacity Utilization (Recovery/Total Spent) 1

$165,000

$165,000

$0

10

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100.

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100.0

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100.0%

$165,000

$165,000

$0

100.0% 100.0%

Accounts Receivable Department

Activity - Manage Invoices

January February

Department Activity Period Amount Time Equation

Accounts Receivable Manage Invoices January $$1$16$165$165,$165,0$165,00$165,000$165,000 If [Invoice].[Order Type]="Web", Then 1 Else if [Invoice].[Order Type]="Fax" Then 5 Else 8

Headcount Hours Per Head Available Hours Available Minutes

65 8 10,400 624,000 Invoice ID Business Group ID Order Type Count Time Cost

2016-01-000001 Customer 1 Web 1 1 $0.30

2016-01-000002 Customer 2 Web 1 1 $0.30

2016-01-000003 Customer 3 Fax 1 5 $1.49

2016-01-000004 Customer 1 Phone 1 8 $2.39

2016-01-000005 Customer 4 Web 1 1 $0.30

2016-01-000006 Customer 2 Phone 1 8 $2.39

2016-01-000007 Customer 4 Web 1 1 $0.30

……. Customer 1 Web 15,078 15,078 $4,506.19

……. Customer 2 Web 13,078 13,078 $3,908.47

$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000$165,000

……. Customer 3 Web 8,578 8,578 $2,563.61

……. Customer 4 Web 11,078 11,078 $3,310.75

……. Customer 1 Fax 8,078 40,390 $12,070.89

……. Customer 2 Fax 7,078 35,390 $10,576.60

……. Customer 3 Fax 7,578 37,890 $11,323.74

……. Customer 4 Fax 6,578 32,890 $9,829.45

……. Customer 1 Phone 9,978 79,824 $23,856.07

……. Customer 2 Phone 11,378 91,024 $27,203.28

……. Customer 3 Phone 13,078 104,624 $31,267.76

……. Customer 4 Phone 10,278 82,224 $24,573.33

2016-01-121843 Customer 3 Phone 1 8 $2.39

Total 121,844 552,101 $

$165,000

$1

$165,000

$16

$165,000

$165

$165,000

$165,

$165,000

$165,0

$165,000

$165,00

$165,000

$165,000

$165,000

$165,000

Capacity Utilization (Total Time/Available Minutes) 8

$165,000

$165,000

88

$165,000

$165,000

88.

$165,000

$165,000

88.5

$165,000

$165,000

88.5%

$165,000

$165,000

88.5%

Table 1

DRBABC PULL EXAMPLE

Table 2

DRBABC PUSH EXAMPL

Table 3

TDABC EXAMPLE

($12,695)

February 2016 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ 25

IT or Finance to meet deadlines or performance measures,

those receiving the allocation would bear the cost impact,

no matter whose behavior caused the variance. Another

negative aspect of the push approach is that it is frequently

capacity insensitive. That is, there’s no obvious way to dif-

ferentiate and classify individual resource capacities as used

or unused (e.g., idle or excess). Hence, the final cost objects

will be modestly overcosted for expenses that they didn’t

cause or require.

As a result of the shortcomings of the push approach, the

pull approach was born. Think of it as a partial absorption

of the resources’ expenses. With the pull approach, senders

of expenses can be viewed as mini profit centers in which

agreed-upon rates for their services are established, typi-

cally based on a budget of planned expenses and expected

volumes. Consumers of these services pay a fixed rate (i.e.,

price) for the actual volume that they consume—no more,

no less. The pull approach opens a new world of arm’s-

length relationships between supporting centers and

customer-facing departments. Customers, whether they are

internal or external, often prefer this arrangement because

it allows them to have some control over how much

expense from their organization is planned for them as

costs.

Additionally, internal service providers may favor this

method because it can show the value of their services or the

need for additional resources based on the overrecovery or

underrecovery of their costs charged to their customers. For

example, if an IT group were shown to be overrecovering its

costs via these chargeouts by a large margin, this information

could be used as justification for increased headcount or at

least demonstrate that they are performing highly. The pull

approach also introduces a rudimentary measure of capacity

utilization: the percent over/under cost recovery. But a prob-

lem with the pull approach is that the correctness of the cost

assignment is highly contingent on setting accurate rates.

Imagine a cost assignment network that includes cross-

charging in which estimated rates are applied. There would

be multiple overrecoveries and underrecoveries of expenses,

potentially large ones, because of faulty rates. The result

would be a difference from the actual GL expense totals in

aggregate, thereby questioning the overall credibility and

understanding of the costs.

Time-Driven vs. Driver Rate-Based

Regardless of the previously referenced advantages and dis-

advantages of the push- vs. pull-based costing approaches,

there lies a separate decision as to whether to use TDABC or

use the conventional DRBABC assignments. Both methods

can be used with either a push or pull approach. To see

how, consider the following examples.

DRIVER RATE-BASED ABC

Pull Approach. An Accounts Receivable (A/R) department

could establish an activity cost driver that is a predefined

rate, such as $1.25 per invoice, based on its budget and vol-

ume projections, and charge for its services on that basis.

At the end of the year, the A/R department will be over-

recovered or underrecovered because their actual incurred

expenses and the volume consumed will never match the

projection exactly, no matter how skilled an organization is

at budgeting. In this example, the pull approach’s driver is

the quantity-based number of invoices rather than a stan-

dard time to process each invoice.

You can see a shortcoming of the pull approach in

Table 1. While a form of capacity utilization value is an out-

put from this approach, there’s a financial underrecovery in

January and an overrecovery in February. The total amount

spent in January was $165,000, but only $152,305 was

charged to customers. In February, $157,909 was charged,

but only $153,900 was spent.

These differences would eventually need to be recon-

ciled somehow at some point.

Push Approach. Alternatively, the DRBABC method could

be used with a push approach in which all of the A/R

department expenses are charged to customers. No over-

recovery or underrecovery reconciliation would be

required. See Table 2 in which all of the expenses are

charged as costs based on number of invoices, resulting in a

net calculated rate each month.

In this case, all of the $165,000 January expenses and all

of the $153,900 February expenses are charged to cus-

tomers, thereby resolving the financial variance problem.

Yet note that the capacity utilization is always 100%. The

cost rate was different in each month, and there’s no meas-

ure of the efficiency of the department.

TIME-DRIVEN ABC

TDABC is a model of supply and demand for cost and

capacity that leverages estimated unit times, not unit quan-

tities. It solves some of the challenges in DRBABC because it

can provide both a full assignment of the expenses as costs

and a meaningful capacity utilization measure. Consider

that the same A/R department could utilize a time-driven

assignment method that’s dependent on the unit times to

process the various types of invoices, which means the

time will differ whether the invoices were received via

Web, fax, or phone. These time-based variables are cap-

tured in a formula that calculates the amount of time taken

to process each invoice. With TDABC, the total time is cal-

culated based on rendering the time equation on every

invoice. The actual A/R department dollars then get

charged to each invoice based on an individual invoice’s

$ % Invoices Net Rate

Customer 1 $40,436 24.5% 33,136 $1.22

Customer 2 $41,691 25.3% 31,536 $1.32

Customer 3 $45,159 27.4% 29,236 $1.54

Customer 4 $37,714 22.9% 27,936 $1.35

Total $$1$16$165$165,$165,0$165,00$165,000$165,000 1$165,000 10$165,000 100$165,000 100.$165,000 100.0$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0% 121,844 $1.35$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%

IT or Finance to meet deadlines or performance measures,

those receiving the allocation would bear the cost impact,

no matter whose behavior caused the variance. Another

negative aspect of the push approach is that it is frequently

capacity insensitive. That is, there’s no obvious way to dif-

ferentiate and classify individual resource capacities as used

or unused (e.g., idle or excess). Hence, the final cost objects

will be modestly overcosted for expenses that they didn’t

cause or require.

As a result of the shortcomings of the push approach, the

pull approach was born. Think of it as a partial absorption

of the resources’ expenses. With the pull approach, senders

of expenses can be viewed as mini profit centers in which

agreed-upon rates for their services are established, typi-

cally based on a budget of planned expenses and expected

volumes. Consumers of these services pay a fixed rate (i.e.,

price) for the actual volume that they consume—no more,

no less. The pull approach opens a new world of arm’s-

length relationships between supporting centers and

customer-facing departments. Customers, whether they are

internal or external, often prefer this arrangement because

it allows them to have some control over how much

expense from their organization is planned for them as

costs.

Additionally, internal service providers may favor this

method because it can show the value of their services or the

need for additional resources based on the overrecovery or

underrecovery of their costs charged to their customers. For

example, if an IT group were shown to be overrecovering its

costs via these chargeouts by a large margin, this information

could be used as justification for increased headcount or at

least demonstrate that they are performing highly. The pull

approach also introduces a rudimentary measure of capacity

utilization: the percent over/under cost recovery. But a prob-

lem with the pull approach is that the correctness of the cost

assignment is highly contingent on setting accurate rates.

Imagine a cost assignment network that includes cross-

charging in which estimated rates are applied. There would

be multiple overrecoveries and underrecoveries of expenses,

potentially large ones, because of faulty rates. The result

would be a difference from the actual GL expense totals in

aggregate, thereby questioning the overall credibility and

understanding of the costs.

Time-Driven vs. Driver Rate-Based

Regardless of the previously referenced advantages and dis-

advantages of the push- vs. pull-based costing approaches,

there lies a separate decision as to whether to use TDABC or

use the conventional DRBABC assignments. Both methods

can be used with either a push or pull approach. To see

how, consider the following examples.

DRIVER RATE-BASED ABC

Pull Approach. An Accounts Receivable (A/R) department

could establish an activity cost driver that is a predefined

rate, such as $1.25 per invoice, based on its budget and vol-

ume projections, and charge for its services on that basis.

At the end of the year, the A/R department will be over-

recovered or underrecovered because their actual incurred

expenses and the volume consumed will never match the

projection exactly, no matter how skilled an organization is

at budgeting. In this example, the pull approach’s driver is

the quantity-based number of invoices rather than a stan-

dard time to process each invoice.

You can see a shortcoming of the pull approach in

Table 1. While a form of capacity utilization value is an out-

put from this approach, there’s a financial underrecovery in

January and an overrecovery in February. The total amount

spent in January was $165,000, but only $152,305 was

charged to customers. In February, $157,909 was charged,

but only $153,900 was spent.

These differences would eventually need to be recon-

ciled somehow at some point.

Push Approach. Alternatively, the DRBABC method could

be used with a push approach in which all of the A/R

department expenses are charged to customers. No over-

recovery or underrecovery reconciliation would be

required. See Table 2 in which all of the expenses are

charged as costs based on number of invoices, resulting in a

net calculated rate each month.

In this case, all of the $165,000 January expenses and all

of the $153,900 February expenses are charged to cus-

tomers, thereby resolving the financial variance problem.

Yet note that the capacity utilization is always 100%. The

cost rate was different in each month, and there’s no meas-

ure of the efficiency of the department.

TIME-DRIVEN ABC

TDABC is a model of supply and demand for cost and

capacity that leverages estimated unit times, not unit quan-

tities. It solves some of the challenges in DRBABC because it

can provide both a full assignment of the expenses as costs

and a meaningful capacity utilization measure. Consider

that the same A/R department could utilize a time-driven

assignment method that’s dependent on the unit times to

process the various types of invoices, which means the

time will differ whether the invoices were received via

Web, fax, or phone. These time-based variables are cap-

tured in a formula that calculates the amount of time taken

to process each invoice. With TDABC, the total time is cal-

culated based on rendering the time equation on every

invoice. The actual A/R department dollars then get

charged to each invoice based on an individual invoice’s

$ % Invoices Net Rate

Customer 1 $40,436 24.5% 33,136 $1.22

Customer 2 $41,691 25.3% 31,536 $1.32

Customer 3 $45,159 27.4% 29,236 $1.54

Customer 4 $37,714 22.9% 27,936 $1.35

Total $$1$16$165$165,$165,0$165,00$165,000$165,000 1$165,000 10$165,000 100$165,000 100.$165,000 100.0$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0% 121,844 $1.35$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%$165,000 100.0%

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

26 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ February 2016

processing time relative to the total processing time of all

invoices. (See Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing by Robert S.

Kaplan and Steven R. Anderson, p. 36, for more details on

this technique for the cost calculations.) This is time-driven

because it uses a time algorithm applied to each transaction

and push because all the expenses are accounted for.

TDABC’s time algorithms are also referred to as time

equations.

With TDABC, the costs are calculated at the invoice level

of detail, not at the aggregated customer level (see Table 3).

The time equation is applied at that more granular level,

and the total amount allocated matches the incurred

expenses, i.e., the same $165,000 in January as seen previ-

ously. The total invoice count matches the total in the con-

ventional DRBABC example, but in this case all of the

dollars were pushed and a calculated time was the basis for

the assignment.

It’s important to realize that the time calculation was

based on the input of standard unit times for the different

order types, not actual times clocked or estimated times

surveyed.

When the values for January are aggregated by cus-

tomer, the summed amounts for each customer are differ-

ent than they were for the DRBABC approach because the

time-driven approach captures more variation and diversity

of cost objects. Customer 3’s low use of Web and high use of

phone increased its cost and provided insight that wouldn’t

be found using the single-driver case. The DRBABC method

can address this by further disaggregating the activity into

more granular ones. But this introduces the issue of how

granular and detailed the DRBABC model and its associated

data collection of activity driver quantities should be

designed. We discuss this issue later in the article.

Additionally, note that there’s a capacity utilization meas-

ure in this full absorption push approach. The DRBABC full

absorption case was capacity insensitive (i.e., 100% of capac-

ity is utilized). The pull single-rate DRBABC approach

showed 92% capacity utilization based on the somewhat

arbitrary standard rate vs. the more informed fact-based

89% utilization using the time-driven method. The

consumed-capacity value from the TDABC approach is based

on the grand total time that was calculated and used to allo-

cate the cost. The available capacity is calculated based on

the number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) multiplied by the

available hours per FTE, two frequently known or estimable

values. This ratio of these two amounts is the capacity uti-

lization, which can be greater or less than 100%. (See Kaplan

and Anderson, p. 77, for an implementation example using

this technique for calculating capacity utilization.)

ABC MODEL STRUCTURE

IMPLICATIONS:

THE CROSSOVER POINT

In defense of the DRBABC approach, the “variation and

diversity” captured by the TDABC approach in the previous

A/R department example could also have been detected

and captured with DRBABC’s push approach through some

additional work. As described earlier, this would have

required “disaggregating” (i.e., decomposing the A/R

department’s activity dictionary into more granular activi-

ties). It will also require estimates from one or more

employees in the A/R department for the increased number

of resource assignments to calculate the activity costs. (An

activity dictionary is a list of activities by function, depart-

ment, and business process that managers can use to help

determine key metrics and find ways to improve opera-

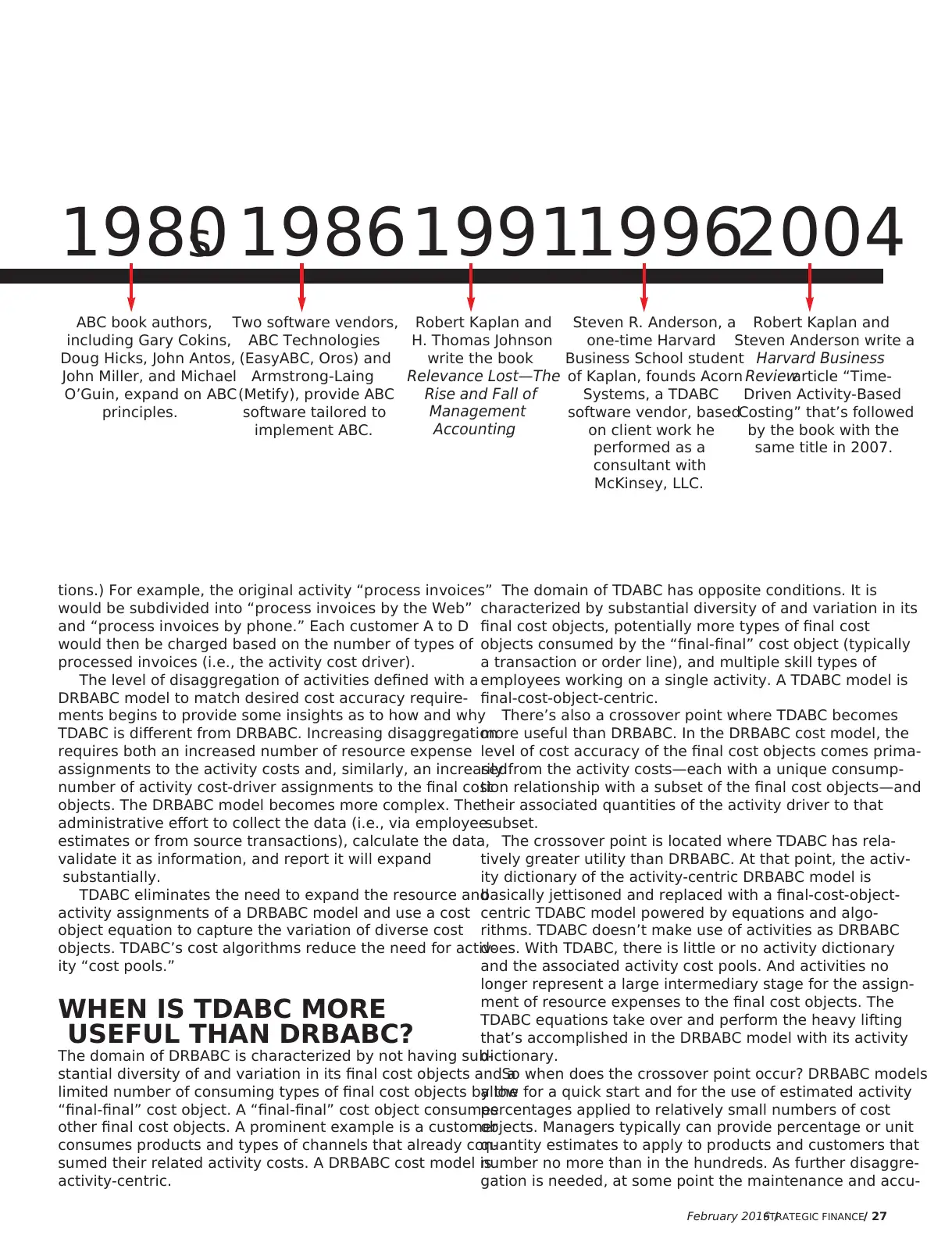

1860s

Albert Fink, a German-

born civil engineer who

worked in the United

States, “invents” ABC as

a means to calculate the

cost of a ton per mile in

the railroad industry.

He didn’t call it activity-

based costing, but his

method used ABC

principles.

1908

Alexander Hamilton

Church, an efficiency

engineer and cost

accountant, writes “The

Proper Distribution of

Expense Burden”

published by The

Engineering Magazine

Company.

1923

John Maurice Clark, an

American economist,

writes the bookStudies

in the Economics of

Overhead Costs.

1984

Robert S. Kaplan writes

a Harvard Business

Reviewarticle titled

“Yesterday’s Accounting

Undermines

Production.”

A TIMELINE OF ABC DEVELOPMEN

processing time relative to the total processing time of all

invoices. (See Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing by Robert S.

Kaplan and Steven R. Anderson, p. 36, for more details on

this technique for the cost calculations.) This is time-driven

because it uses a time algorithm applied to each transaction

and push because all the expenses are accounted for.

TDABC’s time algorithms are also referred to as time

equations.

With TDABC, the costs are calculated at the invoice level

of detail, not at the aggregated customer level (see Table 3).

The time equation is applied at that more granular level,

and the total amount allocated matches the incurred

expenses, i.e., the same $165,000 in January as seen previ-

ously. The total invoice count matches the total in the con-

ventional DRBABC example, but in this case all of the

dollars were pushed and a calculated time was the basis for

the assignment.

It’s important to realize that the time calculation was

based on the input of standard unit times for the different

order types, not actual times clocked or estimated times

surveyed.

When the values for January are aggregated by cus-

tomer, the summed amounts for each customer are differ-

ent than they were for the DRBABC approach because the

time-driven approach captures more variation and diversity

of cost objects. Customer 3’s low use of Web and high use of

phone increased its cost and provided insight that wouldn’t

be found using the single-driver case. The DRBABC method

can address this by further disaggregating the activity into

more granular ones. But this introduces the issue of how

granular and detailed the DRBABC model and its associated

data collection of activity driver quantities should be

designed. We discuss this issue later in the article.

Additionally, note that there’s a capacity utilization meas-

ure in this full absorption push approach. The DRBABC full

absorption case was capacity insensitive (i.e., 100% of capac-

ity is utilized). The pull single-rate DRBABC approach

showed 92% capacity utilization based on the somewhat

arbitrary standard rate vs. the more informed fact-based

89% utilization using the time-driven method. The

consumed-capacity value from the TDABC approach is based

on the grand total time that was calculated and used to allo-

cate the cost. The available capacity is calculated based on

the number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) multiplied by the

available hours per FTE, two frequently known or estimable

values. This ratio of these two amounts is the capacity uti-

lization, which can be greater or less than 100%. (See Kaplan

and Anderson, p. 77, for an implementation example using

this technique for calculating capacity utilization.)

ABC MODEL STRUCTURE

IMPLICATIONS:

THE CROSSOVER POINT

In defense of the DRBABC approach, the “variation and

diversity” captured by the TDABC approach in the previous

A/R department example could also have been detected

and captured with DRBABC’s push approach through some

additional work. As described earlier, this would have

required “disaggregating” (i.e., decomposing the A/R

department’s activity dictionary into more granular activi-

ties). It will also require estimates from one or more

employees in the A/R department for the increased number

of resource assignments to calculate the activity costs. (An

activity dictionary is a list of activities by function, depart-

ment, and business process that managers can use to help

determine key metrics and find ways to improve opera-

1860s

Albert Fink, a German-

born civil engineer who

worked in the United

States, “invents” ABC as

a means to calculate the

cost of a ton per mile in

the railroad industry.

He didn’t call it activity-

based costing, but his

method used ABC

principles.

1908

Alexander Hamilton

Church, an efficiency

engineer and cost

accountant, writes “The

Proper Distribution of

Expense Burden”

published by The

Engineering Magazine

Company.

1923

John Maurice Clark, an

American economist,

writes the bookStudies

in the Economics of

Overhead Costs.

1984

Robert S. Kaplan writes

a Harvard Business

Reviewarticle titled

“Yesterday’s Accounting

Undermines

Production.”

A TIMELINE OF ABC DEVELOPMEN

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

February 2016 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ 27

tions.) For example, the original activity “process invoices”

would be subdivided into “process invoices by the Web”

and “process invoices by phone.” Each customer A to D

would then be charged based on the number of types of

processed invoices (i.e., the activity cost driver).

The level of disaggregation of activities defined with a

DRBABC model to match desired cost accuracy require-

ments begins to provide some insights as to how and why

TDABC is different from DRBABC. Increasing disaggregation

requires both an increased number of resource expense

assignments to the activity costs and, similarly, an increased

number of activity cost-driver assignments to the final cost

objects. The DRBABC model becomes more complex. The

administrative effort to collect the data (i.e., via employee

estimates or from source transactions), calculate the data,

validate it as information, and report it will expand

substantially.

TDABC eliminates the need to expand the resource and

activity assignments of a DRBABC model and use a cost

object equation to capture the variation of diverse cost

objects. TDABC’s cost algorithms reduce the need for activ-

ity “cost pools.”

WHEN IS TDABC MORE

USEFUL THAN DRBABC?

The domain of DRBABC is characterized by not having sub-

stantial diversity of and variation in its final cost objects and a

limited number of consuming types of final cost objects by the

“final-final” cost object. A “final-final” cost object consumes

other final cost objects. A prominent example is a customer

consumes products and types of channels that already con-

sumed their related activity costs. A DRBABC cost model is

activity-centric.

The domain of TDABC has opposite conditions. It is

characterized by substantial diversity of and variation in its

final cost objects, potentially more types of final cost

objects consumed by the “final-final” cost object (typically

a transaction or order line), and multiple skill types of

employees working on a single activity. A TDABC model is

final-cost-object-centric.

There’s also a crossover point where TDABC becomes

more useful than DRBABC. In the DRBABC cost model, the

level of cost accuracy of the final cost objects comes prima-

rily from the activity costs—each with a unique consump-

tion relationship with a subset of the final cost objects—and

their associated quantities of the activity driver to that

subset.

The crossover point is located where TDABC has rela-

tively greater utility than DRBABC. At that point, the activ-

ity dictionary of the activity-centric DRBABC model is

basically jettisoned and replaced with a final-cost-object-

centric TDABC model powered by equations and algo-

rithms. TDABC doesn’t make use of activities as DRBABC

does. With TDABC, there is little or no activity dictionary

and the associated activity cost pools. And activities no

longer represent a large intermediary stage for the assign-

ment of resource expenses to the final cost objects. The

TDABC equations take over and perform the heavy lifting

that’s accomplished in the DRBABC model with its activity

dictionary.

So when does the crossover point occur? DRBABC models

allow for a quick start and for the use of estimated activity

percentages applied to relatively small numbers of cost

objects. Managers typically can provide percentage or unit

quantity estimates to apply to products and customers that

number no more than in the hundreds. As further disaggre-

gation is needed, at some point the maintenance and accu-

1980s

ABC book authors,

including Gary Cokins,

Doug Hicks, John Antos,

John Miller, and Michael

O’Guin, expand on ABC

principles.

1986

Two software vendors,

ABC Technologies

(EasyABC, Oros) and

Armstrong-Laing

(Metify), provide ABC

software tailored to

implement ABC.

1991

Robert Kaplan and

H. Thomas Johnson

write the book

Relevance Lost—The

Rise and Fall of

Management

Accounting.

1996

Steven R. Anderson, a

one-time Harvard

Business School student

of Kaplan, founds Acorn

Systems, a TDABC

software vendor, based

on client work he

performed as a

consultant with

McKinsey, LLC.

2004

Robert Kaplan and

Steven Anderson write a

Harvard Business

Reviewarticle “Time-

Driven Activity-Based

Costing” that’s followed

by the book with the

same title in 2007.

tions.) For example, the original activity “process invoices”

would be subdivided into “process invoices by the Web”

and “process invoices by phone.” Each customer A to D

would then be charged based on the number of types of

processed invoices (i.e., the activity cost driver).

The level of disaggregation of activities defined with a

DRBABC model to match desired cost accuracy require-

ments begins to provide some insights as to how and why

TDABC is different from DRBABC. Increasing disaggregation

requires both an increased number of resource expense

assignments to the activity costs and, similarly, an increased

number of activity cost-driver assignments to the final cost

objects. The DRBABC model becomes more complex. The

administrative effort to collect the data (i.e., via employee

estimates or from source transactions), calculate the data,

validate it as information, and report it will expand

substantially.

TDABC eliminates the need to expand the resource and

activity assignments of a DRBABC model and use a cost

object equation to capture the variation of diverse cost

objects. TDABC’s cost algorithms reduce the need for activ-

ity “cost pools.”

WHEN IS TDABC MORE

USEFUL THAN DRBABC?

The domain of DRBABC is characterized by not having sub-

stantial diversity of and variation in its final cost objects and a

limited number of consuming types of final cost objects by the

“final-final” cost object. A “final-final” cost object consumes

other final cost objects. A prominent example is a customer

consumes products and types of channels that already con-

sumed their related activity costs. A DRBABC cost model is

activity-centric.

The domain of TDABC has opposite conditions. It is

characterized by substantial diversity of and variation in its

final cost objects, potentially more types of final cost

objects consumed by the “final-final” cost object (typically

a transaction or order line), and multiple skill types of

employees working on a single activity. A TDABC model is

final-cost-object-centric.

There’s also a crossover point where TDABC becomes

more useful than DRBABC. In the DRBABC cost model, the

level of cost accuracy of the final cost objects comes prima-

rily from the activity costs—each with a unique consump-

tion relationship with a subset of the final cost objects—and

their associated quantities of the activity driver to that

subset.

The crossover point is located where TDABC has rela-

tively greater utility than DRBABC. At that point, the activ-

ity dictionary of the activity-centric DRBABC model is

basically jettisoned and replaced with a final-cost-object-

centric TDABC model powered by equations and algo-

rithms. TDABC doesn’t make use of activities as DRBABC

does. With TDABC, there is little or no activity dictionary

and the associated activity cost pools. And activities no

longer represent a large intermediary stage for the assign-

ment of resource expenses to the final cost objects. The

TDABC equations take over and perform the heavy lifting

that’s accomplished in the DRBABC model with its activity

dictionary.

So when does the crossover point occur? DRBABC models

allow for a quick start and for the use of estimated activity

percentages applied to relatively small numbers of cost

objects. Managers typically can provide percentage or unit

quantity estimates to apply to products and customers that

number no more than in the hundreds. As further disaggre-

gation is needed, at some point the maintenance and accu-

1980s

ABC book authors,

including Gary Cokins,

Doug Hicks, John Antos,

John Miller, and Michael

O’Guin, expand on ABC

principles.

1986

Two software vendors,

ABC Technologies

(EasyABC, Oros) and

Armstrong-Laing

(Metify), provide ABC

software tailored to

implement ABC.

1991

Robert Kaplan and

H. Thomas Johnson

write the book

Relevance Lost—The

Rise and Fall of

Management

Accounting.

1996

Steven R. Anderson, a

one-time Harvard

Business School student

of Kaplan, founds Acorn

Systems, a TDABC

software vendor, based

on client work he

performed as a

consultant with

McKinsey, LLC.

2004

Robert Kaplan and

Steven Anderson write a

Harvard Business

Reviewarticle “Time-

Driven Activity-Based

Costing” that’s followed

by the book with the

same title in 2007.

28 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ February 2016

racy of a DRBABC model becomes stretched. The activity

dictionary grows and becomes more burdensome to

maintain.

At that point, the substitution of TDABC, with its more

data-driven approach and more transactional-level cost

object instances, becomes more suitable to the task and

easier to maintain. Organizations may not have all the

desirable driver data from their enterprise resource plan-

ning (ERP) systems for the time algorithms, but this

becomes less of a problem as software automation contin-

ues to improve. The added bonus is that TDABC provides

visibility to capacity utilization information while still pro-

viding full absorption of actual cost.

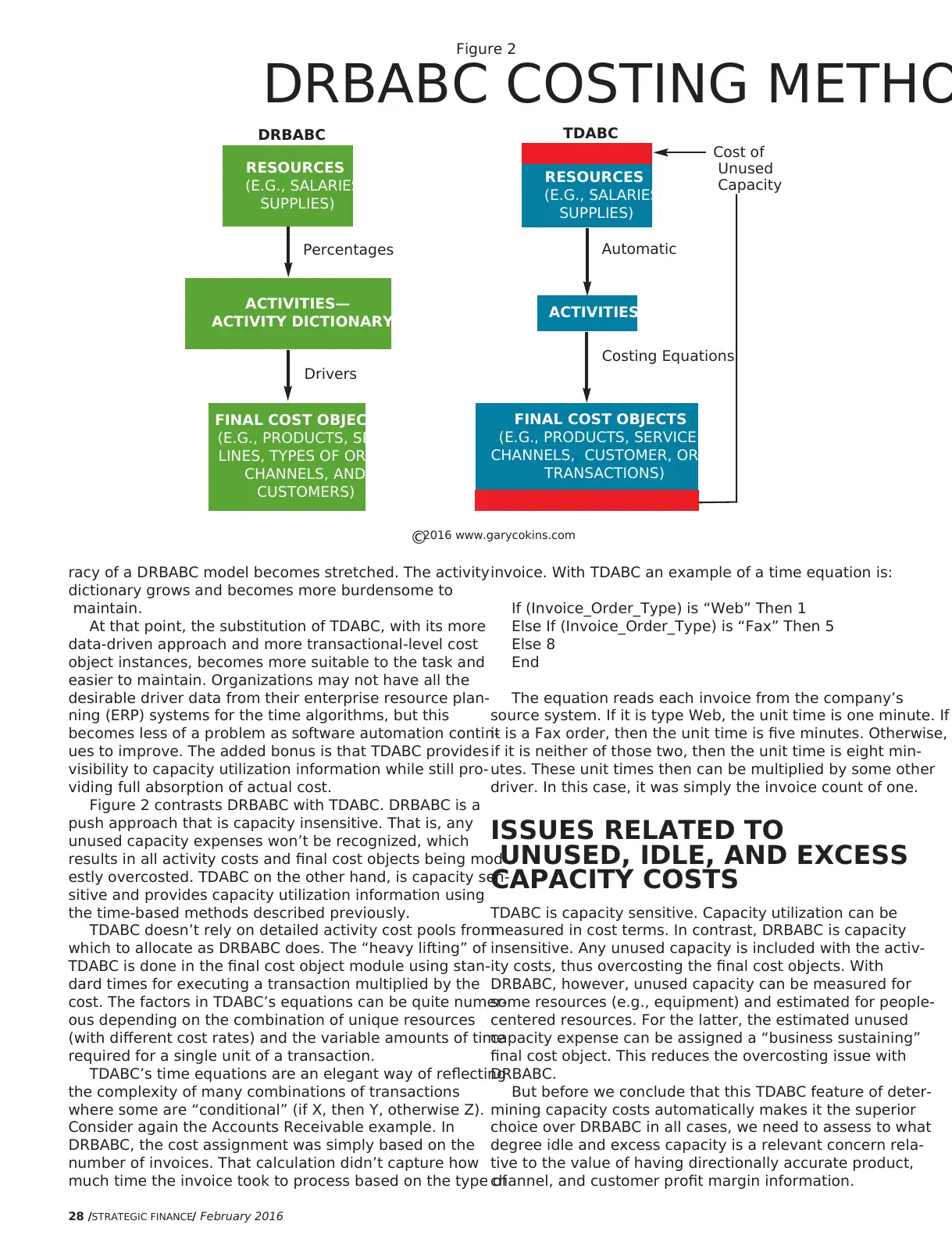

Figure 2 contrasts DRBABC with TDABC. DRBABC is a

push approach that is capacity insensitive. That is, any

unused capacity expenses won’t be recognized, which

results in all activity costs and final cost objects being mod-

estly overcosted. TDABC on the other hand, is capacity sen-

sitive and provides capacity utilization information using

the time-based methods described previously.

TDABC doesn’t rely on detailed activity cost pools from

which to allocate as DRBABC does. The “heavy lifting” of

TDABC is done in the final cost object module using stan-

dard times for executing a transaction multiplied by the

cost. The factors in TDABC’s equations can be quite numer-

ous depending on the combination of unique resources

(with different cost rates) and the variable amounts of time

required for a single unit of a transaction.

TDABC’s time equations are an elegant way of reflecting

the complexity of many combinations of transactions

where some are “conditional” (if X, then Y, otherwise Z).

Consider again the Accounts Receivable example. In

DRBABC, the cost assignment was simply based on the

number of invoices. That calculation didn’t capture how

much time the invoice took to process based on the type of

invoice. With TDABC an example of a time equation is:

If (Invoice_Order_Type) is “Web” Then 1

Else If (Invoice_Order_Type) is “Fax” Then 5

Else 8

End

The equation reads each invoice from the company’s

source system. If it is type Web, the unit time is one minute. If

it is a Fax order, then the unit time is five minutes. Otherwise,

if it is neither of those two, then the unit time is eight min-

utes. These unit times then can be multiplied by some other

driver. In this case, it was simply the invoice count of one.

ISSUES RELATED TO

UNUSED, IDLE, AND EXCESS

CAPACITY COSTS

TDABC is capacity sensitive. Capacity utilization can be

measured in cost terms. In contrast, DRBABC is capacity

insensitive. Any unused capacity is included with the activ-

ity costs, thus overcosting the final cost objects. With

DRBABC, however, unused capacity can be measured for

some resources (e.g., equipment) and estimated for people-

centered resources. For the latter, the estimated unused

capacity expense can be assigned a “business sustaining”

final cost object. This reduces the overcosting issue with

DRBABC.

But before we conclude that this TDABC feature of deter-

mining capacity costs automatically makes it the superior

choice over DRBABC in all cases, we need to assess to what

degree idle and excess capacity is a relevant concern rela-

tive to the value of having directionally accurate product,

channel, and customer profit margin information.

Figure 2

DRBABC COSTING METHO

RESOURCES

(E.G., SALARIES,

SUPPLIES)

RESOURCES

(E.G., SALARIES,

SUPPLIES)

ACTIVITIES—

ACTIVITY DICTIONARY ACTIVITIES

FINAL COST OBJECTS

(E.G., PRODUCTS, SERVICE

LINES, TYPES OF ORDERS,

CHANNELS, AND

CUSTOMERS)

FINAL COST OBJECTS

(E.G., PRODUCTS, SERVICE LINES,

CHANNELS, CUSTOMER, ORDER LINES,

TRANSACTIONS)

Cost of

Unused

Capacity

Percentages Automatic

Costing Equations

Drivers

©2016 www.garycokins.com

DRBABC TDABC

racy of a DRBABC model becomes stretched. The activity

dictionary grows and becomes more burdensome to

maintain.

At that point, the substitution of TDABC, with its more

data-driven approach and more transactional-level cost

object instances, becomes more suitable to the task and

easier to maintain. Organizations may not have all the

desirable driver data from their enterprise resource plan-

ning (ERP) systems for the time algorithms, but this

becomes less of a problem as software automation contin-

ues to improve. The added bonus is that TDABC provides

visibility to capacity utilization information while still pro-

viding full absorption of actual cost.

Figure 2 contrasts DRBABC with TDABC. DRBABC is a

push approach that is capacity insensitive. That is, any

unused capacity expenses won’t be recognized, which

results in all activity costs and final cost objects being mod-

estly overcosted. TDABC on the other hand, is capacity sen-

sitive and provides capacity utilization information using

the time-based methods described previously.

TDABC doesn’t rely on detailed activity cost pools from

which to allocate as DRBABC does. The “heavy lifting” of

TDABC is done in the final cost object module using stan-

dard times for executing a transaction multiplied by the

cost. The factors in TDABC’s equations can be quite numer-

ous depending on the combination of unique resources

(with different cost rates) and the variable amounts of time

required for a single unit of a transaction.

TDABC’s time equations are an elegant way of reflecting

the complexity of many combinations of transactions

where some are “conditional” (if X, then Y, otherwise Z).

Consider again the Accounts Receivable example. In

DRBABC, the cost assignment was simply based on the

number of invoices. That calculation didn’t capture how

much time the invoice took to process based on the type of

invoice. With TDABC an example of a time equation is:

If (Invoice_Order_Type) is “Web” Then 1

Else If (Invoice_Order_Type) is “Fax” Then 5

Else 8

End

The equation reads each invoice from the company’s

source system. If it is type Web, the unit time is one minute. If

it is a Fax order, then the unit time is five minutes. Otherwise,

if it is neither of those two, then the unit time is eight min-

utes. These unit times then can be multiplied by some other

driver. In this case, it was simply the invoice count of one.

ISSUES RELATED TO

UNUSED, IDLE, AND EXCESS

CAPACITY COSTS

TDABC is capacity sensitive. Capacity utilization can be

measured in cost terms. In contrast, DRBABC is capacity

insensitive. Any unused capacity is included with the activ-

ity costs, thus overcosting the final cost objects. With

DRBABC, however, unused capacity can be measured for

some resources (e.g., equipment) and estimated for people-

centered resources. For the latter, the estimated unused

capacity expense can be assigned a “business sustaining”

final cost object. This reduces the overcosting issue with

DRBABC.

But before we conclude that this TDABC feature of deter-

mining capacity costs automatically makes it the superior

choice over DRBABC in all cases, we need to assess to what

degree idle and excess capacity is a relevant concern rela-

tive to the value of having directionally accurate product,

channel, and customer profit margin information.

Figure 2

DRBABC COSTING METHO

RESOURCES

(E.G., SALARIES,

SUPPLIES)

RESOURCES

(E.G., SALARIES,

SUPPLIES)

ACTIVITIES—

ACTIVITY DICTIONARY ACTIVITIES

FINAL COST OBJECTS

(E.G., PRODUCTS, SERVICE

LINES, TYPES OF ORDERS,

CHANNELS, AND

CUSTOMERS)

FINAL COST OBJECTS

(E.G., PRODUCTS, SERVICE LINES,

CHANNELS, CUSTOMER, ORDER LINES,

TRANSACTIONS)

Cost of

Unused

Capacity

Percentages Automatic

Costing Equations

Drivers

©2016 www.garycokins.com

DRBABC TDABC

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

February 2016 /STRATEGIC FINANCE/ 29

MAKING THE TRANSITION

As previously mentioned, whether a company selects

TDABC or DRBABC, the shared goal of both methods is to

move away from the single cost pool allocation factors that

violate costing’s causality principle. TDABC has advantages

with respect to level of detail, cost accuracy, automation,

and capacity calculation. But it also relies on capturing unit

times or other equation inputs for major business processes.

In many organizations, these simply aren’t available at the

onset of the initiative.

DRBABC has an advantage by enabling a quick start to

getting meaningful insight into costs and profitability.

Smaller activity lists and fewer numbers of final cost objects

that can be aggregated (e.g., product families, types of cus-

tomers) can be modeled quickly. Estimates from knowl-

edgeable cross-functional employees can be used initially

and iteratively be replaced with source data as needed. As

mentioned earlier, push cost assignments always normalize

to 100%. Understanding and needed buy-in from managers

for applying ABC can be achieved. Going forward in time,

the DRBABC model can also iteratively be disaggregated in

only selected parts of the model where further granularity

yields better or more accurate information. Once an organi-

zation matures and its informational needs become more

sophisticated, it can choose to migrate to TDABC.

We believe that all organizations can benefit from an

ABC cost assignment method and that either method dis-

cussed here is an improvement over what typically exists

with flawed and misleading cost and profit margin infor-

mation. For some organizations, starting with a DRBABC

model with subsequent iterative remodeling can be a fast

path toward results. Yet some organizations will, over time,

potentially reach the crossover point. From there onward,

TDABC offers increased benefits with regard to accuracy,

model maintenance, and overcoming the capacity-

insensitive nature of DRBABC.SF

Gary Cokins, CPIM, is IMA’s executive-in-residence and is founder

and owner of the consulting firm Analytics-Based Performance

Management LLC in Cary, N.C. (www.garycokins.com). A thought

leader in EPM, business analytics, and advanced cost management, he

previously was a consultant with Deloitte, KPMG, Electronic Data

Systems (EDS), and SAS. He also is a long-time member and active

committee member of IMA. You can reach Gary at (919) 720-2718 or

gcokins@garycokins.com.

Douglas D. Paul is solutions and engagement manager for Ignite

Technologies, formerly Acorn Systems, Inc. He has more than 25 years o

experience in finance software, consulting in cost and performance

management, and corporate positions in controllership and IT. You can

reach Doug at ddpaulpm@yahoo.com.

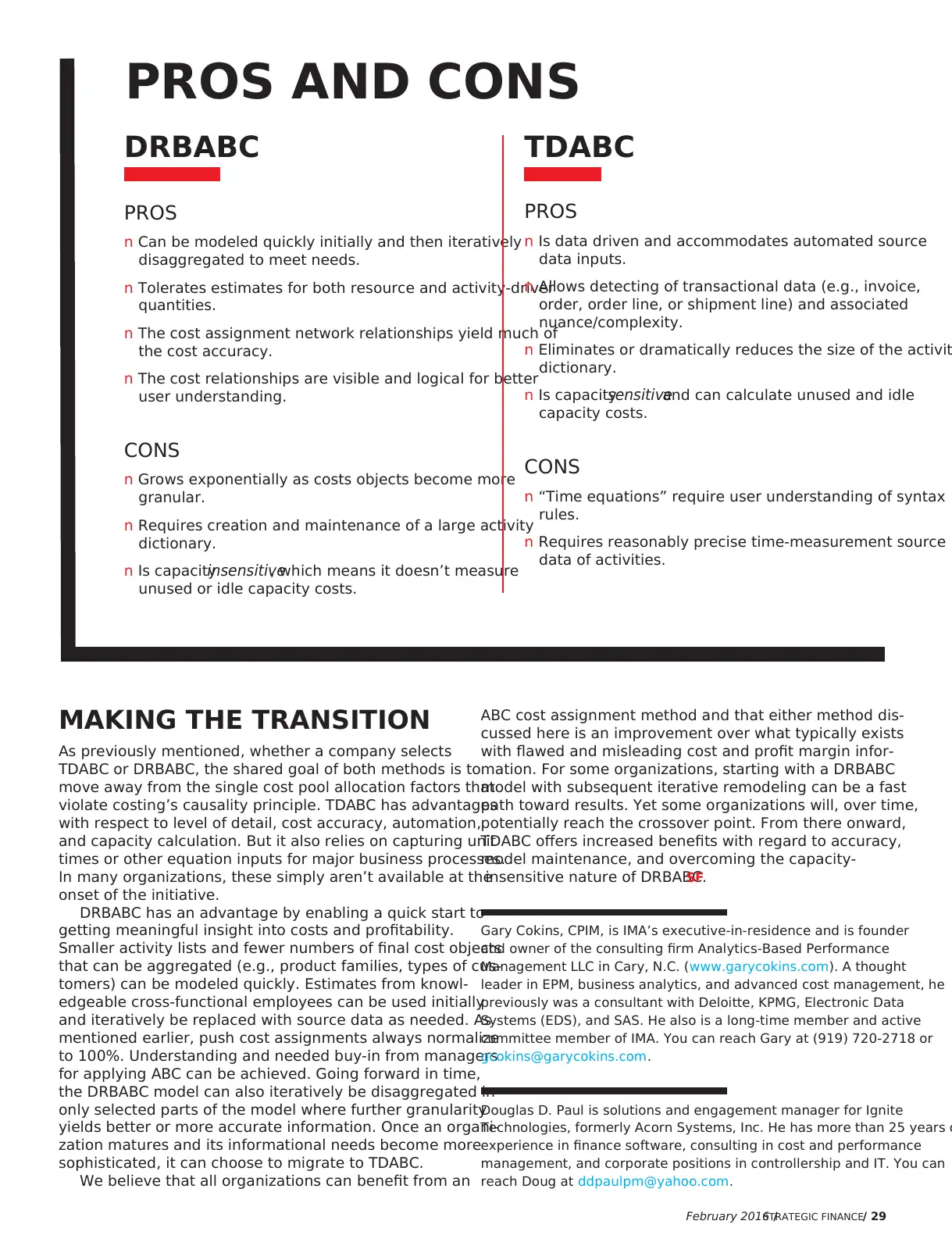

DRBABC

PROS

n Can be modeled quickly initially and then iteratively

disaggregated to meet needs.

n Tolerates estimates for both resource and activity-driver

quantities.

n The cost assignment network relationships yield much of

the cost accuracy.

n The cost relationships are visible and logical for better

user understanding.

CONS

n Grows exponentially as costs objects become more

granular.

n Requires creation and maintenance of a large activity

dictionary.

n Is capacityinsensitive, which means it doesn’t measure

unused or idle capacity costs.

TDABC

PROS

n Is data driven and accommodates automated source

data inputs.

n Allows detecting of transactional data (e.g., invoice,

order, order line, or shipment line) and associated

nuance/complexity.

n Eliminates or dramatically reduces the size of the activit

dictionary.

n Is capacitysensitiveand can calculate unused and idle

capacity costs.

CONS

n “Time equations” require user understanding of syntax

rules.

n Requires reasonably precise time-measurement source

data of activities.

PROS AND CONS

MAKING THE TRANSITION

As previously mentioned, whether a company selects

TDABC or DRBABC, the shared goal of both methods is to

move away from the single cost pool allocation factors that

violate costing’s causality principle. TDABC has advantages

with respect to level of detail, cost accuracy, automation,

and capacity calculation. But it also relies on capturing unit

times or other equation inputs for major business processes.

In many organizations, these simply aren’t available at the

onset of the initiative.

DRBABC has an advantage by enabling a quick start to

getting meaningful insight into costs and profitability.

Smaller activity lists and fewer numbers of final cost objects

that can be aggregated (e.g., product families, types of cus-

tomers) can be modeled quickly. Estimates from knowl-

edgeable cross-functional employees can be used initially

and iteratively be replaced with source data as needed. As