Relevance of ELM: A Replication Analysis in Digital Advertising

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/03

|14

|8125

|431

Report

AI Summary

This report examines the relevance of traditional advertising theories, specifically the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), in today's digital marketplace. It begins by highlighting the shift in advertising expenditures from traditional mass media to online and digital channels, driven by changing consumer habits, demographics, and the rise of emerging markets. The study replicates a seminal ELM study to determine if the original findings hold true in the current environment. The authors argue that many agency planning models are still based on outdated theories from the mass-media era, potentially leading to inefficiencies. The literature review covers the ELM's core concepts, including the central and peripheral routes to persuasion, and acknowledges criticisms of the model. Ultimately, the report advocates for further replication of historical studies to ensure their ongoing validity and applicability in the rapidly evolving digital world, suggesting that practitioners should question traditional models like the ELM and embrace new systems of consumer thinking.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289993214

Does Traditional Advertising Theory Apply to the Digital World? A Replication

Analysis Questions the Relevance Of the Elaboration Likelihood Model

Article in Journal of Advertising Research · December 2015

DOI: 10.2501/JAR-2015-001

CITATIONS

13

READS

1,738

5 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Brickbats and bouquets for marketing. View project

From transactional to relationalView project

Gayle Kerr

Queensland University of Technology

51PUBLICATIONS668CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Philip J. Kitchen

ESC Rennes School of Business

189PUBLICATIONS3,288CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Frank Mulhern

Northwestern University

22PUBLICATIONS174CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Gayle Kerr on 14 September 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Does Traditional Advertising Theory Apply to the Digital World? A Replication

Analysis Questions the Relevance Of the Elaboration Likelihood Model

Article in Journal of Advertising Research · December 2015

DOI: 10.2501/JAR-2015-001

CITATIONS

13

READS

1,738

5 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Brickbats and bouquets for marketing. View project

From transactional to relationalView project

Gayle Kerr

Queensland University of Technology

51PUBLICATIONS668CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Philip J. Kitchen

ESC Rennes School of Business

189PUBLICATIONS3,288CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Frank Mulhern

Northwestern University

22PUBLICATIONS174CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Gayle Kerr on 14 September 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Source: Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 55, No. 4, December 2015

Downloaded from warc.com

Does Traditional Advertising Theory Apply to the Digital Wo

A Replication Analysis Questions the Relevance of the

Elaboration Likelihood Model

All theory is based on a set of seminal concepts and empirical research that are assumed to be replicable and inviolate

time. Recent changes in technology, consumer habits, demographics, and marketplaces, however, have raised question

about the applicability of advertising theory developed in a mass-media environment to today's interactive marketplace.

current study explores this idea by replicating the most-cited study in advertising research, the elaboration likelihood mo

which just three of 27 findings were replicated. The current results advocate further replication of historical studies to ver

current value for ongoing scholarship.

Gayle Kerr

Queensland University of Technology

Don E. Schultz

Northwestern University

Philip J. Kitchen

ESC Rennes School of Business

Frank J. Mulhern

Northwestern University

Park Beede

Higher Colleges of Technology

MANAGEMENT SLANT

To be truly a science–and of value to practitioners–seminal advertising theory, such as the elaboration likelihood mo

(ELM), must be replicable across different cultures and periods.

In addition to replication, advertising theory also should be validated through the documentation and scrutiny of its pr

by marketers.

Practitioners should question planning frameworks that use traditional advertising models such as the ELM, as they l

not reflect how consumers think in a digital world.

Advertising is not always a rational or controllable process, and practitioners should embrace new systems of consum

thinking in driving advertising strategy, tactics, and investment.

INTRODUCTION

Advertising researchers owe much to the halcyon days of mass media. That includes the entertainment of television serie

Lucy,” the information-gathering machine of the BBC, and the power of television to build emotional brand connections. In

cultures, the mass-media period—roughly from 1950 to 1980—particularly was fruitful, encouraging a new wave of advert

research. As one scholar noted, “Some of the best research ever done on advertising was done during the early days of

television” (Bogart, 1986, p. 13). Almost all of advertising’s premier academic journals were established after television (o

the first being theJournal of Advertising Researchin 1960).

The world has changed radically since those days of mass-media dominance. And, advertising has changed as well. A sim

Downloaded from warc.com

Does Traditional Advertising Theory Apply to the Digital Wo

A Replication Analysis Questions the Relevance of the

Elaboration Likelihood Model

All theory is based on a set of seminal concepts and empirical research that are assumed to be replicable and inviolate

time. Recent changes in technology, consumer habits, demographics, and marketplaces, however, have raised question

about the applicability of advertising theory developed in a mass-media environment to today's interactive marketplace.

current study explores this idea by replicating the most-cited study in advertising research, the elaboration likelihood mo

which just three of 27 findings were replicated. The current results advocate further replication of historical studies to ver

current value for ongoing scholarship.

Gayle Kerr

Queensland University of Technology

Don E. Schultz

Northwestern University

Philip J. Kitchen

ESC Rennes School of Business

Frank J. Mulhern

Northwestern University

Park Beede

Higher Colleges of Technology

MANAGEMENT SLANT

To be truly a science–and of value to practitioners–seminal advertising theory, such as the elaboration likelihood mo

(ELM), must be replicable across different cultures and periods.

In addition to replication, advertising theory also should be validated through the documentation and scrutiny of its pr

by marketers.

Practitioners should question planning frameworks that use traditional advertising models such as the ELM, as they l

not reflect how consumers think in a digital world.

Advertising is not always a rational or controllable process, and practitioners should embrace new systems of consum

thinking in driving advertising strategy, tactics, and investment.

INTRODUCTION

Advertising researchers owe much to the halcyon days of mass media. That includes the entertainment of television serie

Lucy,” the information-gathering machine of the BBC, and the power of television to build emotional brand connections. In

cultures, the mass-media period—roughly from 1950 to 1980—particularly was fruitful, encouraging a new wave of advert

research. As one scholar noted, “Some of the best research ever done on advertising was done during the early days of

television” (Bogart, 1986, p. 13). Almost all of advertising’s premier academic journals were established after television (o

the first being theJournal of Advertising Researchin 1960).

The world has changed radically since those days of mass-media dominance. And, advertising has changed as well. A sim

way to measure this change is through advertising expenditures. Between 2013 and 2014, advertising expenditure

grew in North America (+5.4 percent) and the United Kingdom (+7.2 percent);

was flat in continental Europe, notably Germany (+1.5 percent) and France (–2.1 percent); and

soared in the emerging markets of China (+12.5 percent), India (+14.2 percent), and Brazil (+14.7 percent).1

Digital and Demographic Shifts

Another way to look at advertising change is by the diversion of that expenditure from traditional mass media to online and

channels.

In Australia, online advertising expenditure grew by 190 percent in the year June 2012 to June 2013, exceeding free-

television expenditures for the very first time.2

By the end of 2014, in 11 other countries (including China, marketers spent more on digital advertising than on televi3

Internet advertising spending has the highest growth rate of any medium globally (up 18.5 percent in 2014)1 and increasing

30.3 percent annually in the Middle East and Africa and 20.6 percent in Latin America.4

Consumer media habits, like purchasing behaviors, also have changed since the last half of the twentieth century. The

combination of an abundance of consumer choice and consumers’ increasing access to information has created a cornuc

alternatives.

For example, a 2012 study of shoppers ages 20 to 40 reported that 65 percent of U.K. and 55 percent of U.S. participants

searched for products online and went in-store to inspect them before going back online to make their purchases.5 Around one-

third used their smartphone to compare prices in-store with alternative outlets. This so-called “show-rooming” approach is

around the world (Earley, 2014; McCauley and Donofrio, 2014). In India, consumers used mobile phone photos to genera

agreement on planned purchases from family and friends in the United States and the United Kingdom (Jain and Pant, 20

In addition to these marketplace changes, fundamental demographic shifts have occurred as well. For example, in 2013, w

accounted for two-thirds or $12 trillion of the $18 trillion total in global consumer spending.4 Another example of demographic shift

is the growing middle class of shoppers in China. Because of their enthusiasm for online shopping and their enhanced fina

position over the past few decades, China has overtaken the United States as the world’s leader in e-commerce.6

In summary, advertising has evolved from a mass-media marketplace—dominated by the United States—to one driven by

and mobile media, buoyed by the growth of emerging markets. This is not just the result of changing consumer media hab

decision making, and purchasing power, but it also appears to be part of the rise of a transformative global society: Massi

social, marketing, and media changes clearly are reflected in advertising expenditure and allocation.

Is Traditional Advertising Theory Still Relevant?

Given all these changes, the current study questions whether the foundational advertising theories—constructed during th

mass media dominance and a United States–centric marketplace—remain relevant today.

Although there is discussion (even disquiet) about it among academics—and some empirical evidence—to support these

challenges, the current article proposes that the best way to examine the relevance, rigor, and applicability of historic adve

theory is through empirical testing. In other words, if advertising’s earlier so-called “seminal research studies” were condu

again, the authors of the current study asked, “Would the original results be confirmed?

Thus, the position of the current article is simple: If one of the most-cited advertising studies could be replicated, some of

growing concerns about the applicability of the historical advertising theory base in a changing world would be allayed. Su

differences, if found between past studies and current replications, would

lend support to the current academic debate and

provide direction for subsequent investigations of the traditional advertising frameworks that support current research

approaches and guide advertising practice.

Because citations are the accepted “currency” of advertising scholarship, the current study tested one of the most-cited st

advertising research: the lengthy, broad, and deep work conducted on the development, testing, and application of the ela

likelihood model (ELM; Petty, Cacioppo, Schumann, 1983).

Of all advertising theory pillars, the ELM is the most frequently cited source of academic literature by advertising research

grew in North America (+5.4 percent) and the United Kingdom (+7.2 percent);

was flat in continental Europe, notably Germany (+1.5 percent) and France (–2.1 percent); and

soared in the emerging markets of China (+12.5 percent), India (+14.2 percent), and Brazil (+14.7 percent).1

Digital and Demographic Shifts

Another way to look at advertising change is by the diversion of that expenditure from traditional mass media to online and

channels.

In Australia, online advertising expenditure grew by 190 percent in the year June 2012 to June 2013, exceeding free-

television expenditures for the very first time.2

By the end of 2014, in 11 other countries (including China, marketers spent more on digital advertising than on televi3

Internet advertising spending has the highest growth rate of any medium globally (up 18.5 percent in 2014)1 and increasing

30.3 percent annually in the Middle East and Africa and 20.6 percent in Latin America.4

Consumer media habits, like purchasing behaviors, also have changed since the last half of the twentieth century. The

combination of an abundance of consumer choice and consumers’ increasing access to information has created a cornuc

alternatives.

For example, a 2012 study of shoppers ages 20 to 40 reported that 65 percent of U.K. and 55 percent of U.S. participants

searched for products online and went in-store to inspect them before going back online to make their purchases.5 Around one-

third used their smartphone to compare prices in-store with alternative outlets. This so-called “show-rooming” approach is

around the world (Earley, 2014; McCauley and Donofrio, 2014). In India, consumers used mobile phone photos to genera

agreement on planned purchases from family and friends in the United States and the United Kingdom (Jain and Pant, 20

In addition to these marketplace changes, fundamental demographic shifts have occurred as well. For example, in 2013, w

accounted for two-thirds or $12 trillion of the $18 trillion total in global consumer spending.4 Another example of demographic shift

is the growing middle class of shoppers in China. Because of their enthusiasm for online shopping and their enhanced fina

position over the past few decades, China has overtaken the United States as the world’s leader in e-commerce.6

In summary, advertising has evolved from a mass-media marketplace—dominated by the United States—to one driven by

and mobile media, buoyed by the growth of emerging markets. This is not just the result of changing consumer media hab

decision making, and purchasing power, but it also appears to be part of the rise of a transformative global society: Massi

social, marketing, and media changes clearly are reflected in advertising expenditure and allocation.

Is Traditional Advertising Theory Still Relevant?

Given all these changes, the current study questions whether the foundational advertising theories—constructed during th

mass media dominance and a United States–centric marketplace—remain relevant today.

Although there is discussion (even disquiet) about it among academics—and some empirical evidence—to support these

challenges, the current article proposes that the best way to examine the relevance, rigor, and applicability of historic adve

theory is through empirical testing. In other words, if advertising’s earlier so-called “seminal research studies” were condu

again, the authors of the current study asked, “Would the original results be confirmed?

Thus, the position of the current article is simple: If one of the most-cited advertising studies could be replicated, some of

growing concerns about the applicability of the historical advertising theory base in a changing world would be allayed. Su

differences, if found between past studies and current replications, would

lend support to the current academic debate and

provide direction for subsequent investigations of the traditional advertising frameworks that support current research

approaches and guide advertising practice.

Because citations are the accepted “currency” of advertising scholarship, the current study tested one of the most-cited st

advertising research: the lengthy, broad, and deep work conducted on the development, testing, and application of the ela

likelihood model (ELM; Petty, Cacioppo, Schumann, 1983).

Of all advertising theory pillars, the ELM is the most frequently cited source of academic literature by advertising research

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

(Pasadeos, Phelps, and Edison, 2008; Kitchenet al., 2014). Further, it is considered to be “the most influential theoretical

contribution” (Beard, 2002, p. 72). Thus, the authors of the current study believe, a replication of that 1983 study would do

allay the concerns of current day researchers.

Such replication also would permit the examination of the basic premises of advertising research, which clearly have chan

over time. Traditional research from the 1950s through to the 1980s was based on the premise that “advertising is someth

doesto people” (Stewart, 1992, p. 15). The latter is a holdover from the “hypodermic” (or “magic-bullet”) approach that def

behaviorism in the 1930s (Berger, 1995) and was rooted in experiences of a rapidly growing marketplace—with few media

options and limited consumer knowledge and choice.

Fast-forward to the digital age: Those concepts may no longer apply, as today’s empowered consumers have increasing c

over most aspects of the advertising process (Kerr and Schultz, 2010; Kitchen and Uzunoglu, 2015).

It is, therefore, important that advertising be explored in context—and across contexts—rather than in isolation. As one sc

noted, “A typical research paradigm within the field uses relatively naive consumers, fictitious products, forced exposure t

advertising for a single product, and measures that are designed to identify incremental changes,” (Stewart, 1992, p. 7). S

practice perhaps was an artifact of advertising research’s positivist traditions and borrowings from experimental psycholog

(Bogart, 1986; Heath and Feldwick, 2008; Heath, 2012; Kerr and Schultz, 2010).

It is also a concern, however—one that was raised at the 2013 Wharton Conference on Empirical Generalizations in Adve

At that gathering, many delegates advocated that generalizability be explored by using multiple data sets across multiple c

“Rigor comes from results that hold over and over, ideally when conducted by different researchers who use fully transpar

processes, data, analyses, and results” (Wind, Sharp, and Nelson-Field, 2013, p. 178).

Finally, the current authors contend that their study is important from the practitioners’ perspective. Many agency planning

which drive advertising strategy, tactics, and investment, are underpinned by models and theories from the 1970s and 198

(Heath and Feldwick, 2008). A prime example is the linear, one-way approach of the hierarchy of effects model, which stil

underpins most media planning today (Heath, 2012). There would appear to be substantial increases in advertising efficie

financial gain in using planning models that correctly reflect today’s consumer, media systems, and marketplace, rather th

standards of an earlier marketing ecosystem.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The ELM emerged from the maelstrom of conflicting literature, conceptual ambiguities, and methodological problems that

defined the field of persuasion and attitude change in the 1960s and 1970s (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1972; Petty and Caciopp

1983). ELM theorists provided a desperately needed, yet simple, concise framework that would include both cognitive arg

quality and heuristics (Schumann, Kotowski, Ahn, and Haugtvedt, 2012).

The resultant ELM advocates two basic routes to persuasion: the central and the peripheral, determined by the amount of

cognitive effort a person used to process a message (Schumannet al., 2012).

Central route to persuasion: When elaboration likelihood is high, information processing will occur via the central rou

Attitude change will be more persistent (Haugtvedt and Petty, 1989) and predictive of behavior (Petty and Cacioppo,

Peripheral route to persuasion: When little cognitive effort is expended and elaboration is low, processing may occur

peripheral route, relying upon cues such as source credibility and heuristics (Petty and Cacioppo, 1983) to enable th

persuasion.

Criticisms of the ELM

Despite being heralded as one of the most influential advertising-research theories (Szczepanski, 2006), the ELM also ha

one of the most criticized. This criticism includes fundamental constructs such as (Kitchenet al., 2014):

the dual-processing framework;

the idea of a continuum of elaboration;

the definition of the mediating variables and independent variables; and

the fact that the model is descriptive, not analytical.

Instead of being explored in the current study, these criticisms were acknowledged as issues that remain empirically unre

The current authors noted that these criticisms have not had an impact on the influence (or use of) the ELM by advertising

scholars.

contribution” (Beard, 2002, p. 72). Thus, the authors of the current study believe, a replication of that 1983 study would do

allay the concerns of current day researchers.

Such replication also would permit the examination of the basic premises of advertising research, which clearly have chan

over time. Traditional research from the 1950s through to the 1980s was based on the premise that “advertising is someth

doesto people” (Stewart, 1992, p. 15). The latter is a holdover from the “hypodermic” (or “magic-bullet”) approach that def

behaviorism in the 1930s (Berger, 1995) and was rooted in experiences of a rapidly growing marketplace—with few media

options and limited consumer knowledge and choice.

Fast-forward to the digital age: Those concepts may no longer apply, as today’s empowered consumers have increasing c

over most aspects of the advertising process (Kerr and Schultz, 2010; Kitchen and Uzunoglu, 2015).

It is, therefore, important that advertising be explored in context—and across contexts—rather than in isolation. As one sc

noted, “A typical research paradigm within the field uses relatively naive consumers, fictitious products, forced exposure t

advertising for a single product, and measures that are designed to identify incremental changes,” (Stewart, 1992, p. 7). S

practice perhaps was an artifact of advertising research’s positivist traditions and borrowings from experimental psycholog

(Bogart, 1986; Heath and Feldwick, 2008; Heath, 2012; Kerr and Schultz, 2010).

It is also a concern, however—one that was raised at the 2013 Wharton Conference on Empirical Generalizations in Adve

At that gathering, many delegates advocated that generalizability be explored by using multiple data sets across multiple c

“Rigor comes from results that hold over and over, ideally when conducted by different researchers who use fully transpar

processes, data, analyses, and results” (Wind, Sharp, and Nelson-Field, 2013, p. 178).

Finally, the current authors contend that their study is important from the practitioners’ perspective. Many agency planning

which drive advertising strategy, tactics, and investment, are underpinned by models and theories from the 1970s and 198

(Heath and Feldwick, 2008). A prime example is the linear, one-way approach of the hierarchy of effects model, which stil

underpins most media planning today (Heath, 2012). There would appear to be substantial increases in advertising efficie

financial gain in using planning models that correctly reflect today’s consumer, media systems, and marketplace, rather th

standards of an earlier marketing ecosystem.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The ELM emerged from the maelstrom of conflicting literature, conceptual ambiguities, and methodological problems that

defined the field of persuasion and attitude change in the 1960s and 1970s (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1972; Petty and Caciopp

1983). ELM theorists provided a desperately needed, yet simple, concise framework that would include both cognitive arg

quality and heuristics (Schumann, Kotowski, Ahn, and Haugtvedt, 2012).

The resultant ELM advocates two basic routes to persuasion: the central and the peripheral, determined by the amount of

cognitive effort a person used to process a message (Schumannet al., 2012).

Central route to persuasion: When elaboration likelihood is high, information processing will occur via the central rou

Attitude change will be more persistent (Haugtvedt and Petty, 1989) and predictive of behavior (Petty and Cacioppo,

Peripheral route to persuasion: When little cognitive effort is expended and elaboration is low, processing may occur

peripheral route, relying upon cues such as source credibility and heuristics (Petty and Cacioppo, 1983) to enable th

persuasion.

Criticisms of the ELM

Despite being heralded as one of the most influential advertising-research theories (Szczepanski, 2006), the ELM also ha

one of the most criticized. This criticism includes fundamental constructs such as (Kitchenet al., 2014):

the dual-processing framework;

the idea of a continuum of elaboration;

the definition of the mediating variables and independent variables; and

the fact that the model is descriptive, not analytical.

Instead of being explored in the current study, these criticisms were acknowledged as issues that remain empirically unre

The current authors noted that these criticisms have not had an impact on the influence (or use of) the ELM by advertising

scholars.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Replication Attempts

Despite the pervasiveness—and continued criticism—of the ELM over the last three decades, very few studies have soug

replicate the original ELM experiment in its entirety. Instead, most studies have focused on trying to replicate a portion, va

construct of the ELM (Kang and Herr, 2006; Te’eni-Harari, Lampert, and Lehman-Wilzig, 2007; Trampe, Stapel, Siero, and

Mulder, 2010).

On the one hand, those who did seek to replicate the original ELM study unanimously questioned the model’s validity. For

example, scholars who closely replicated the original model—using slightly different products—found little or no support fo

ELM (Cole, Ettenson, Reinke, and Schrader 1990). In a meta-analysis, there was concern that only researchers associate

the original researchers, Petty and Cacioppo, were able to generate results consistent with the ELM’s predictions (Johnso

Eagly, 1989).

On the other hand, failure to replicate the results of the original study, most likely, was the result of modifications or exclus

critical substantive features of the ELM, the original authors of the theory argued (Petty, Kasmer, Haugtvedt, and Caciopp

RESEARCH QUESTION

The current authors chose the seminal ELM study (Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann, 1983) for replication for a number of

An initial study (Petty and Cacioppo,1981) failed to provide any evidence of a peripheral route to persuasion (Petty a

Cacioppo, 1983).

The authors of the original study described the 1983 experiment as a “more sensitive test of the two routes to persua

(Petty and Cacioppo, 1983, p. 18).

The 1983 study is the most republished of all of Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann’s work.

Guiding this replication, the research question for the current study was:

RQ1: Does the ELM explain how today’s consumers process advertising and change attitudes through the central and pe

routes to persuasion?

METHODOLOGY

The authors of the current study noted that they replicated the 1983 study faithfully, in its entirety and, for the first time, in

different countries: the United States (where the original was conducted), the United Kingdom, and Australia.

Like the original 1983 experiment, the replication used a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design, manipulating the independent variables

message processing involvement (high/low), argument strength (strong/weak) and source characteristics (high/low).

Sample

The 1983 experiment used a sample of 160 male and female undergraduate students in a major Midwestern American un

In the current replication, the samples generally were larger and represented a larger global cross-section but still focused

group of sample subjects comparable to the original group of undergraduates:

218 in Australia,

315 in the United Kingdom, and

140 in the United States.

To ensure that the different results across the three countries did not reflect cultural differences, participants in Australia, t

Kingdom and the United States studies were compared across the six dimensions of Hofstede’s cultural tool comparison.

three countries, rated from 0 to 100, scored almost identically on

power distance (36, 35, 40);

individualism (90, 89, 91);

masculinity (61, 66, 62); and

indulgence (71, 69, 68).

Australia and the United States (51, 46) were stronger on uncertainty avoidance than the United Kingdom (35), although t

Kingdom (51) was far more pragmatic compared to Australia and the United States (21, 26). Given the cultural similarities

three countries, differences were unlikely in cross-national responses to scales.

Despite the pervasiveness—and continued criticism—of the ELM over the last three decades, very few studies have soug

replicate the original ELM experiment in its entirety. Instead, most studies have focused on trying to replicate a portion, va

construct of the ELM (Kang and Herr, 2006; Te’eni-Harari, Lampert, and Lehman-Wilzig, 2007; Trampe, Stapel, Siero, and

Mulder, 2010).

On the one hand, those who did seek to replicate the original ELM study unanimously questioned the model’s validity. For

example, scholars who closely replicated the original model—using slightly different products—found little or no support fo

ELM (Cole, Ettenson, Reinke, and Schrader 1990). In a meta-analysis, there was concern that only researchers associate

the original researchers, Petty and Cacioppo, were able to generate results consistent with the ELM’s predictions (Johnso

Eagly, 1989).

On the other hand, failure to replicate the results of the original study, most likely, was the result of modifications or exclus

critical substantive features of the ELM, the original authors of the theory argued (Petty, Kasmer, Haugtvedt, and Caciopp

RESEARCH QUESTION

The current authors chose the seminal ELM study (Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann, 1983) for replication for a number of

An initial study (Petty and Cacioppo,1981) failed to provide any evidence of a peripheral route to persuasion (Petty a

Cacioppo, 1983).

The authors of the original study described the 1983 experiment as a “more sensitive test of the two routes to persua

(Petty and Cacioppo, 1983, p. 18).

The 1983 study is the most republished of all of Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann’s work.

Guiding this replication, the research question for the current study was:

RQ1: Does the ELM explain how today’s consumers process advertising and change attitudes through the central and pe

routes to persuasion?

METHODOLOGY

The authors of the current study noted that they replicated the 1983 study faithfully, in its entirety and, for the first time, in

different countries: the United States (where the original was conducted), the United Kingdom, and Australia.

Like the original 1983 experiment, the replication used a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design, manipulating the independent variables

message processing involvement (high/low), argument strength (strong/weak) and source characteristics (high/low).

Sample

The 1983 experiment used a sample of 160 male and female undergraduate students in a major Midwestern American un

In the current replication, the samples generally were larger and represented a larger global cross-section but still focused

group of sample subjects comparable to the original group of undergraduates:

218 in Australia,

315 in the United Kingdom, and

140 in the United States.

To ensure that the different results across the three countries did not reflect cultural differences, participants in Australia, t

Kingdom and the United States studies were compared across the six dimensions of Hofstede’s cultural tool comparison.

three countries, rated from 0 to 100, scored almost identically on

power distance (36, 35, 40);

individualism (90, 89, 91);

masculinity (61, 66, 62); and

indulgence (71, 69, 68).

Australia and the United States (51, 46) were stronger on uncertainty avoidance than the United Kingdom (35), although t

Kingdom (51) was far more pragmatic compared to Australia and the United States (21, 26). Given the cultural similarities

three countries, differences were unlikely in cross-national responses to scales.

Independent Variables

The independent variables were virtually identical to those cited in the 1983 experiment:

Involvement: Participants were given two booklets containing stimulus material and a questionnaire. In the first booklet,

involvement was measured in the same two places—using the same two devices—as the original 1983 experiment.

Endorsers (peripheral cues): Like the original experiment, the test material contained both non-famous endorsers (w

unknown and average-looking male and female models) and local celebrities relevant to the market in which the

advertisements were being tested (i.e. different sports stars from Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

Argument strength: Like the 1983 experiment, the current study also contained different treatments using weak and s

arguments promoting disposable razors. Arguments in the original study, however, such as “floats in water with a min

of rust” or “designed with the bathroom in mind” were not considered relevant or persuasive to today’s test groups. C

points, therefore, were collected from the websites of three leading disposable razor manufacturers, Schick, Wilkinso

Sword, and Bic. They were evaluated by an expert panel and matched as closely as possible with the original advert

claims, in terms of argument valence (logical or emotional) and strength (strong or weak).

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables from the 1983 study also were used in the current experiment:

Attitudes: What the 1983 study had defined as an “attitude measure” or “attitude index” was represented in the curren

as the average of the three scores—on a per-subject basis—from the 9-point semantic differential scales that measu

overall impression, expected satisfaction, and favorableness of the Edge disposable razor.

Purchase Intentions: This variable was rated on a 4-point scale.

RESULTS PART 1

Manipulation Checks

In a manipulation check of involvement,

75 percent of U.S. participants, 70 percent of U.K. participants, and 50 percent of Australian participants in high-invo

conditions correctly recalled they were to select a brand of disposable razor.

In low-involvement conditions, 79 percent of U.S., 70 percent of U.K., and 63 percent of Australian participants corre

recalled the alternative incentive.

The foregoing results compare with 93 percent for high involvement and 78 percent for low involvement in the origina

In the endorser-manipulation check, two questions were asked, replicating the original study. The first question was about

recognition:

74 percent of U.K., 36 percent of Australian, and 36 percent of U.S. participants indicated recognition, compared to

94 percent in the original study.

The second question concerned the respondents’ liking of the people in the advertisement:

The celebrity was liked more in the United States (5.36 compared to 4.49 for an ordinary citizen) and in the original s

(6.06 compared to 3.64).

In the United Kingdom and Australia, there was no difference in terms of the likeability of celebrities and ordinary citiz

In the original study’s manipulation check for argument-persuasiveness, subjects exposed to strong arguments rated them

significantly more persuasive (M = 5.46) than those exposed to weak arguments (M = 4.03).

This also was the case in the current study where, in the United Kingdom, strong arguments led to a higher mean score. I

United States and Australia, strong arguments were considered no more persuasive than weak arguments. This is explore

further in the next section.

RESULTS PART 2

The results on the dependent variables—attitudes and purchase intentions—from the three administrations of the current

(Australia, United States, and the United Kingdom) bore little resemblance to the original results from 1983 (See Tables 1

The independent variables were virtually identical to those cited in the 1983 experiment:

Involvement: Participants were given two booklets containing stimulus material and a questionnaire. In the first booklet,

involvement was measured in the same two places—using the same two devices—as the original 1983 experiment.

Endorsers (peripheral cues): Like the original experiment, the test material contained both non-famous endorsers (w

unknown and average-looking male and female models) and local celebrities relevant to the market in which the

advertisements were being tested (i.e. different sports stars from Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

Argument strength: Like the 1983 experiment, the current study also contained different treatments using weak and s

arguments promoting disposable razors. Arguments in the original study, however, such as “floats in water with a min

of rust” or “designed with the bathroom in mind” were not considered relevant or persuasive to today’s test groups. C

points, therefore, were collected from the websites of three leading disposable razor manufacturers, Schick, Wilkinso

Sword, and Bic. They were evaluated by an expert panel and matched as closely as possible with the original advert

claims, in terms of argument valence (logical or emotional) and strength (strong or weak).

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables from the 1983 study also were used in the current experiment:

Attitudes: What the 1983 study had defined as an “attitude measure” or “attitude index” was represented in the curren

as the average of the three scores—on a per-subject basis—from the 9-point semantic differential scales that measu

overall impression, expected satisfaction, and favorableness of the Edge disposable razor.

Purchase Intentions: This variable was rated on a 4-point scale.

RESULTS PART 1

Manipulation Checks

In a manipulation check of involvement,

75 percent of U.S. participants, 70 percent of U.K. participants, and 50 percent of Australian participants in high-invo

conditions correctly recalled they were to select a brand of disposable razor.

In low-involvement conditions, 79 percent of U.S., 70 percent of U.K., and 63 percent of Australian participants corre

recalled the alternative incentive.

The foregoing results compare with 93 percent for high involvement and 78 percent for low involvement in the origina

In the endorser-manipulation check, two questions were asked, replicating the original study. The first question was about

recognition:

74 percent of U.K., 36 percent of Australian, and 36 percent of U.S. participants indicated recognition, compared to

94 percent in the original study.

The second question concerned the respondents’ liking of the people in the advertisement:

The celebrity was liked more in the United States (5.36 compared to 4.49 for an ordinary citizen) and in the original s

(6.06 compared to 3.64).

In the United Kingdom and Australia, there was no difference in terms of the likeability of celebrities and ordinary citiz

In the original study’s manipulation check for argument-persuasiveness, subjects exposed to strong arguments rated them

significantly more persuasive (M = 5.46) than those exposed to weak arguments (M = 4.03).

This also was the case in the current study where, in the United Kingdom, strong arguments led to a higher mean score. I

United States and Australia, strong arguments were considered no more persuasive than weak arguments. This is explore

further in the next section.

RESULTS PART 2

The results on the dependent variables—attitudes and purchase intentions—from the three administrations of the current

(Australia, United States, and the United Kingdom) bore little resemblance to the original results from 1983 (See Tables 1

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

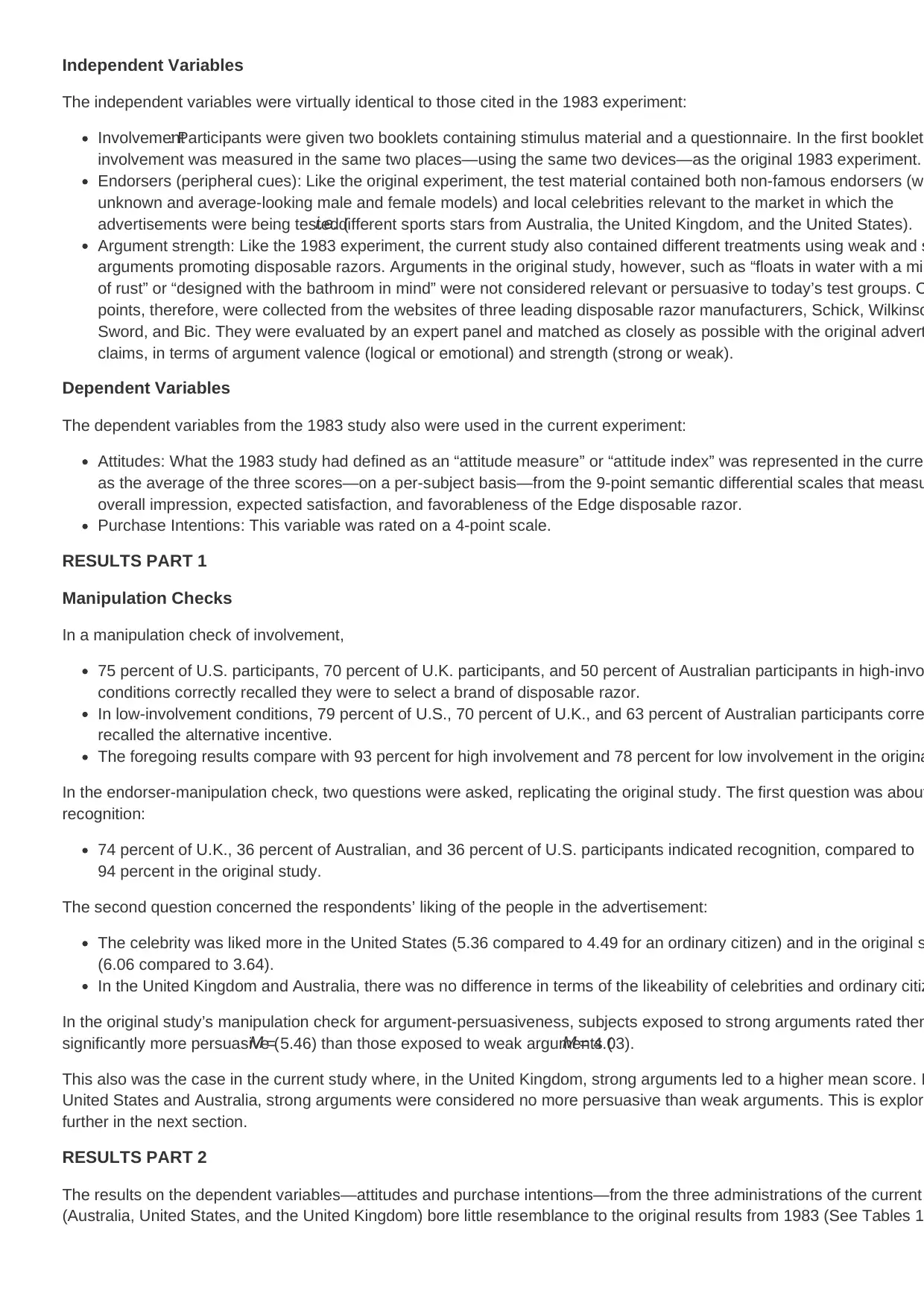

In the replicated study, for the same dependent variables, the means typically were close to the midpoint (zero) and show

minimal differences between the high- and low-involvement conditions for endorser and argument strength (See Table 1).

Attitudes and Involvement

In the original study, the attitude index was higher for the low-involvement group (mean score = 0.99) than for the high-inv

group (mean score = 0.31).

Among the current study’s three replications in the re-test, two of them, the U.K. and Australian respondents, showed no s

difference in the mean attitude score across the involvement treatments. In the U.S. study, the difference in the attitude sc

approached significance (p = 0.064) but in the opposite direction of the 1983 study. That is, the attitude score was higher for

higher involvement group than the lower involvement group (See Table 2).

Hence, the 1983 results were not confirmed in any of the three replicated studies.

Attitudes and Endorsers

In terms of the impact of the celebrity endorser on attitudes toward the razor brand, the 1983 study claimed to find a main

indicating that advertisements featuring celebrity endorsers led to a more positive attitude score (0.86 for celebrity compa

the non-celebrity mean of 0.41). Notably, that conclusion was reached despite thep value being 0.09.

minimal differences between the high- and low-involvement conditions for endorser and argument strength (See Table 1).

Attitudes and Involvement

In the original study, the attitude index was higher for the low-involvement group (mean score = 0.99) than for the high-inv

group (mean score = 0.31).

Among the current study’s three replications in the re-test, two of them, the U.K. and Australian respondents, showed no s

difference in the mean attitude score across the involvement treatments. In the U.S. study, the difference in the attitude sc

approached significance (p = 0.064) but in the opposite direction of the 1983 study. That is, the attitude score was higher for

higher involvement group than the lower involvement group (See Table 2).

Hence, the 1983 results were not confirmed in any of the three replicated studies.

Attitudes and Endorsers

In terms of the impact of the celebrity endorser on attitudes toward the razor brand, the 1983 study claimed to find a main

indicating that advertisements featuring celebrity endorsers led to a more positive attitude score (0.86 for celebrity compa

the non-celebrity mean of 0.41). Notably, that conclusion was reached despite thep value being 0.09.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

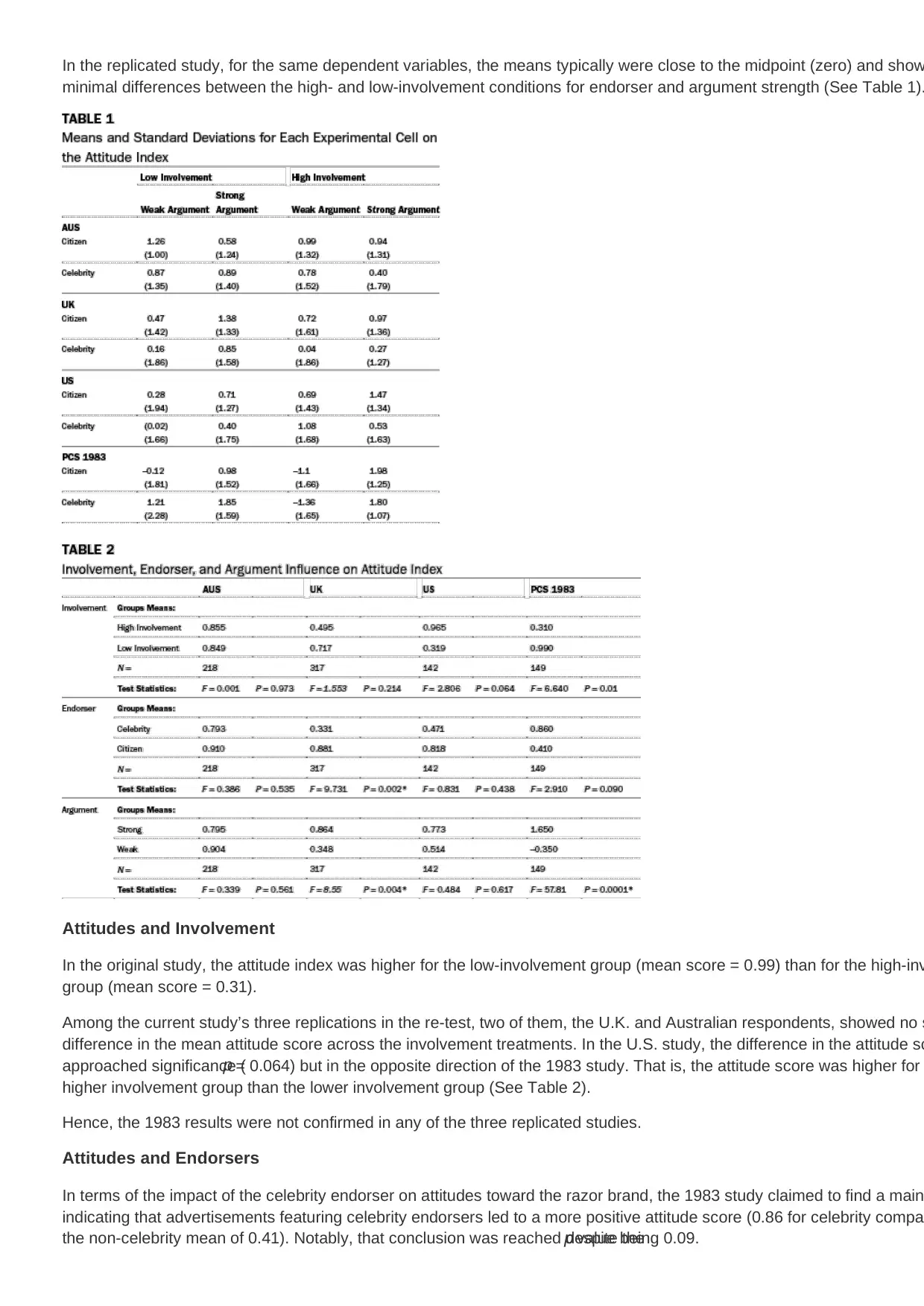

In the three-study replication, the endorser effect was significant only in the U.K. study where the citizen endorser actually

higherattitude than the celebrity—the opposite of what the 1983 study claimed.

Attitudes and Argument Strength

The third main effect tested the impact of strong versus weak arguments. The original study found a mean attitude score o

for the strong argument and a –0.35 for the weak argument. That finding was replicated in the U.K. data (0.86 versus 0.35p =

0.004).

Overall, among the nine attempts to replicate the 1983 study results for the impact of the three treatments on attitudes, thi

only one incident where the results replicated the 1983 study.

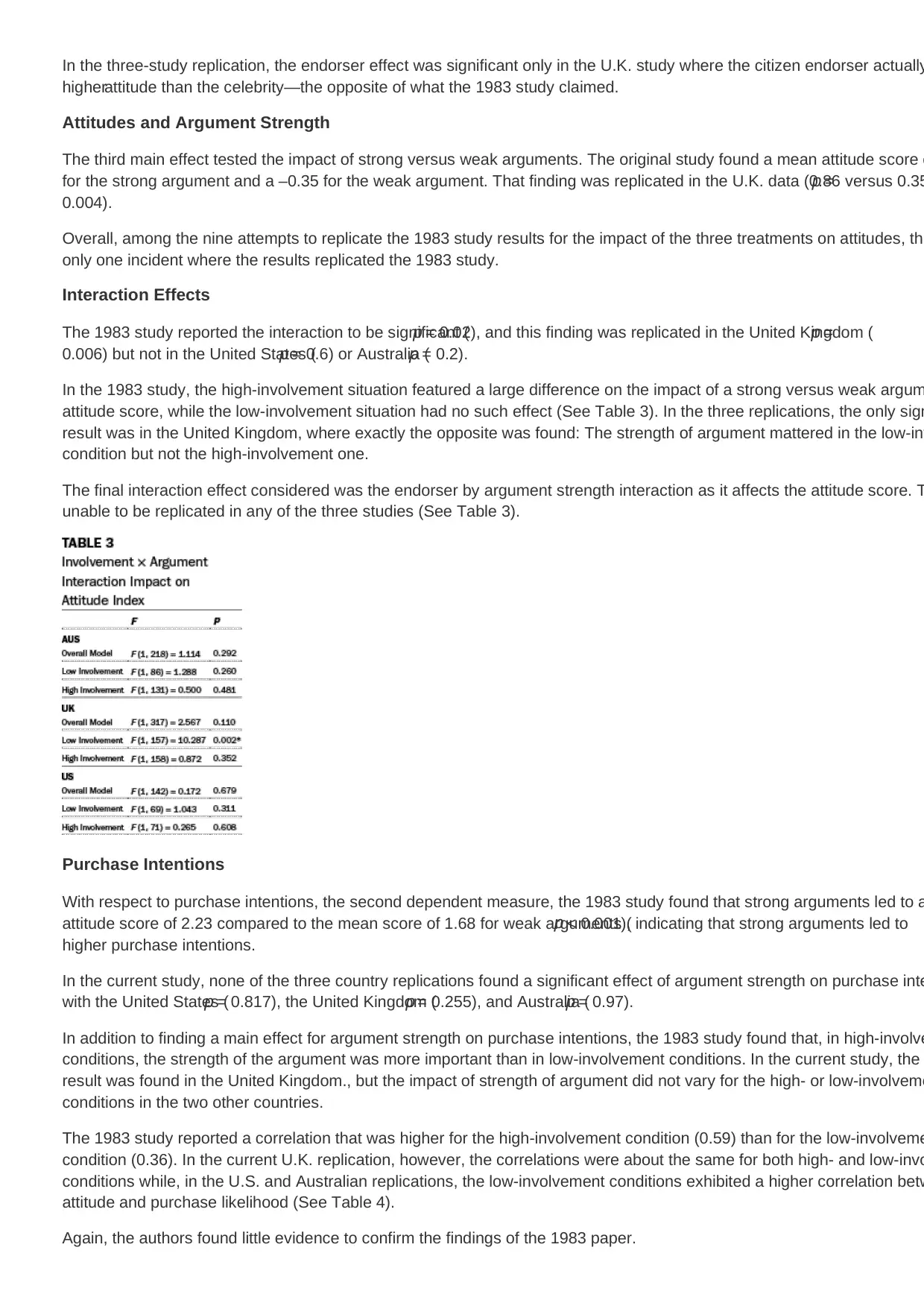

Interaction Effects

The 1983 study reported the interaction to be significant (p = 0.02), and this finding was replicated in the United Kingdom (p =

0.006) but not in the United States (p = 0.6) or Australia (p = 0.2).

In the 1983 study, the high-involvement situation featured a large difference on the impact of a strong versus weak argum

attitude score, while the low-involvement situation had no such effect (See Table 3). In the three replications, the only sign

result was in the United Kingdom, where exactly the opposite was found: The strength of argument mattered in the low-inv

condition but not the high-involvement one.

The final interaction effect considered was the endorser by argument strength interaction as it affects the attitude score. T

unable to be replicated in any of the three studies (See Table 3).

Purchase Intentions

With respect to purchase intentions, the second dependent measure, the 1983 study found that strong arguments led to a

attitude score of 2.23 compared to the mean score of 1.68 for weak arguments (p < 0.001), indicating that strong arguments led to

higher purchase intentions.

In the current study, none of the three country replications found a significant effect of argument strength on purchase inte

with the United States (p = 0.817), the United Kingdom (p = 0.255), and Australia (p = 0.97).

In addition to finding a main effect for argument strength on purchase intentions, the 1983 study found that, in high-involve

conditions, the strength of the argument was more important than in low-involvement conditions. In the current study, the

result was found in the United Kingdom., but the impact of strength of argument did not vary for the high- or low-involveme

conditions in the two other countries.

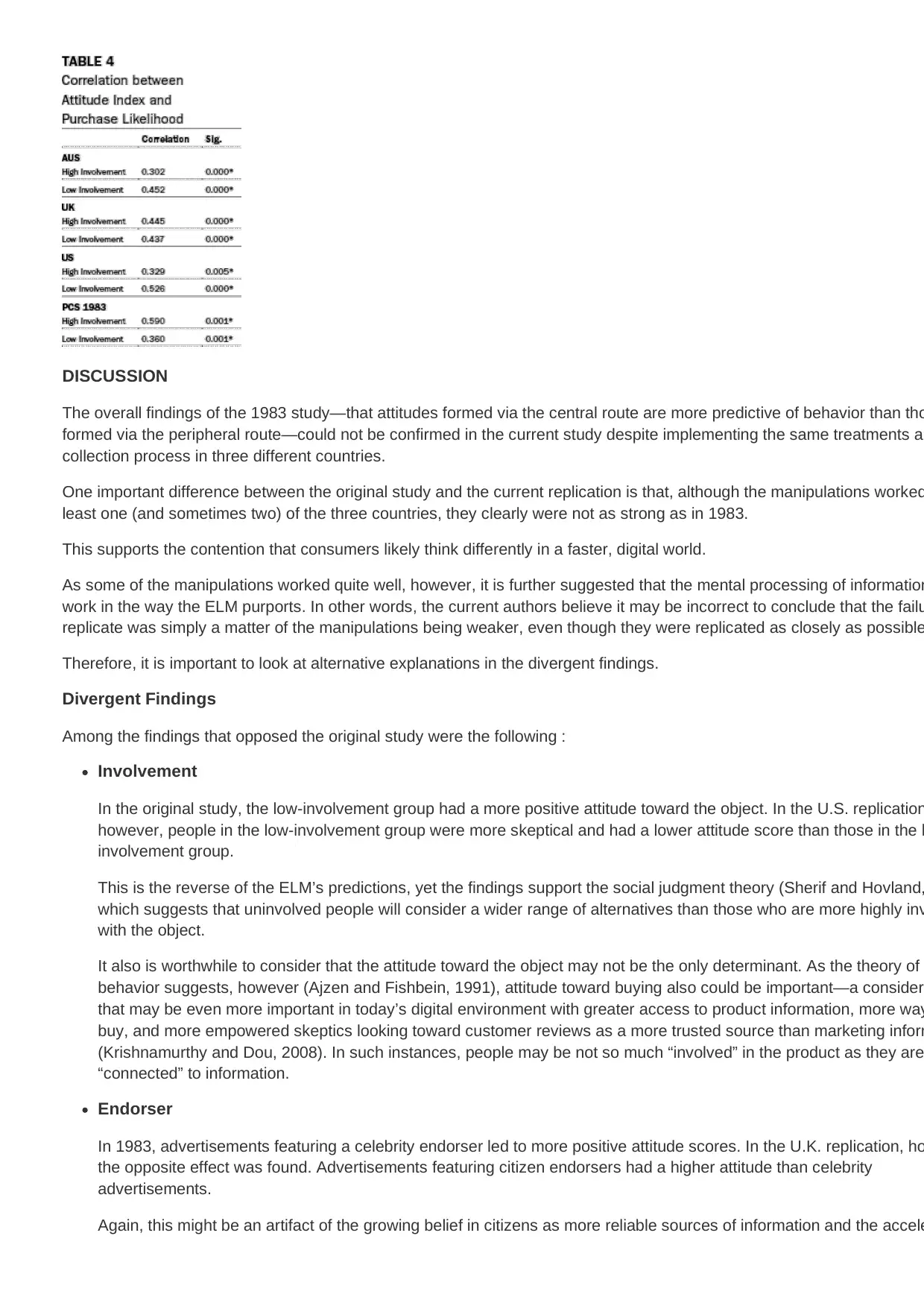

The 1983 study reported a correlation that was higher for the high-involvement condition (0.59) than for the low-involveme

condition (0.36). In the current U.K. replication, however, the correlations were about the same for both high- and low-invo

conditions while, in the U.S. and Australian replications, the low-involvement conditions exhibited a higher correlation betw

attitude and purchase likelihood (See Table 4).

Again, the authors found little evidence to confirm the findings of the 1983 paper.

higherattitude than the celebrity—the opposite of what the 1983 study claimed.

Attitudes and Argument Strength

The third main effect tested the impact of strong versus weak arguments. The original study found a mean attitude score o

for the strong argument and a –0.35 for the weak argument. That finding was replicated in the U.K. data (0.86 versus 0.35p =

0.004).

Overall, among the nine attempts to replicate the 1983 study results for the impact of the three treatments on attitudes, thi

only one incident where the results replicated the 1983 study.

Interaction Effects

The 1983 study reported the interaction to be significant (p = 0.02), and this finding was replicated in the United Kingdom (p =

0.006) but not in the United States (p = 0.6) or Australia (p = 0.2).

In the 1983 study, the high-involvement situation featured a large difference on the impact of a strong versus weak argum

attitude score, while the low-involvement situation had no such effect (See Table 3). In the three replications, the only sign

result was in the United Kingdom, where exactly the opposite was found: The strength of argument mattered in the low-inv

condition but not the high-involvement one.

The final interaction effect considered was the endorser by argument strength interaction as it affects the attitude score. T

unable to be replicated in any of the three studies (See Table 3).

Purchase Intentions

With respect to purchase intentions, the second dependent measure, the 1983 study found that strong arguments led to a

attitude score of 2.23 compared to the mean score of 1.68 for weak arguments (p < 0.001), indicating that strong arguments led to

higher purchase intentions.

In the current study, none of the three country replications found a significant effect of argument strength on purchase inte

with the United States (p = 0.817), the United Kingdom (p = 0.255), and Australia (p = 0.97).

In addition to finding a main effect for argument strength on purchase intentions, the 1983 study found that, in high-involve

conditions, the strength of the argument was more important than in low-involvement conditions. In the current study, the

result was found in the United Kingdom., but the impact of strength of argument did not vary for the high- or low-involveme

conditions in the two other countries.

The 1983 study reported a correlation that was higher for the high-involvement condition (0.59) than for the low-involveme

condition (0.36). In the current U.K. replication, however, the correlations were about the same for both high- and low-invo

conditions while, in the U.S. and Australian replications, the low-involvement conditions exhibited a higher correlation betw

attitude and purchase likelihood (See Table 4).

Again, the authors found little evidence to confirm the findings of the 1983 paper.

DISCUSSION

The overall findings of the 1983 study—that attitudes formed via the central route are more predictive of behavior than tho

formed via the peripheral route—could not be confirmed in the current study despite implementing the same treatments an

collection process in three different countries.

One important difference between the original study and the current replication is that, although the manipulations worked

least one (and sometimes two) of the three countries, they clearly were not as strong as in 1983.

This supports the contention that consumers likely think differently in a faster, digital world.

As some of the manipulations worked quite well, however, it is further suggested that the mental processing of information

work in the way the ELM purports. In other words, the current authors believe it may be incorrect to conclude that the failu

replicate was simply a matter of the manipulations being weaker, even though they were replicated as closely as possible

Therefore, it is important to look at alternative explanations in the divergent findings.

Divergent Findings

Among the findings that opposed the original study were the following :

Involvement

In the original study, the low-involvement group had a more positive attitude toward the object. In the U.S. replication

however, people in the low-involvement group were more skeptical and had a lower attitude score than those in the h

involvement group.

This is the reverse of the ELM’s predictions, yet the findings support the social judgment theory (Sherif and Hovland,

which suggests that uninvolved people will consider a wider range of alternatives than those who are more highly inv

with the object.

It also is worthwhile to consider that the attitude toward the object may not be the only determinant. As the theory of

behavior suggests, however (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1991), attitude toward buying also could be important—a consider

that may be even more important in today’s digital environment with greater access to product information, more way

buy, and more empowered skeptics looking toward customer reviews as a more trusted source than marketing inform

(Krishnamurthy and Dou, 2008). In such instances, people may be not so much “involved” in the product as they are

“connected” to information.

Endorser

In 1983, advertisements featuring a celebrity endorser led to more positive attitude scores. In the U.K. replication, ho

the opposite effect was found. Advertisements featuring citizen endorsers had a higher attitude than celebrity

advertisements.

Again, this might be an artifact of the growing belief in citizens as more reliable sources of information and the accele

The overall findings of the 1983 study—that attitudes formed via the central route are more predictive of behavior than tho

formed via the peripheral route—could not be confirmed in the current study despite implementing the same treatments an

collection process in three different countries.

One important difference between the original study and the current replication is that, although the manipulations worked

least one (and sometimes two) of the three countries, they clearly were not as strong as in 1983.

This supports the contention that consumers likely think differently in a faster, digital world.

As some of the manipulations worked quite well, however, it is further suggested that the mental processing of information

work in the way the ELM purports. In other words, the current authors believe it may be incorrect to conclude that the failu

replicate was simply a matter of the manipulations being weaker, even though they were replicated as closely as possible

Therefore, it is important to look at alternative explanations in the divergent findings.

Divergent Findings

Among the findings that opposed the original study were the following :

Involvement

In the original study, the low-involvement group had a more positive attitude toward the object. In the U.S. replication

however, people in the low-involvement group were more skeptical and had a lower attitude score than those in the h

involvement group.

This is the reverse of the ELM’s predictions, yet the findings support the social judgment theory (Sherif and Hovland,

which suggests that uninvolved people will consider a wider range of alternatives than those who are more highly inv

with the object.

It also is worthwhile to consider that the attitude toward the object may not be the only determinant. As the theory of

behavior suggests, however (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1991), attitude toward buying also could be important—a consider

that may be even more important in today’s digital environment with greater access to product information, more way

buy, and more empowered skeptics looking toward customer reviews as a more trusted source than marketing inform

(Krishnamurthy and Dou, 2008). In such instances, people may be not so much “involved” in the product as they are

“connected” to information.

Endorser

In 1983, advertisements featuring a celebrity endorser led to more positive attitude scores. In the U.K. replication, ho

the opposite effect was found. Advertisements featuring citizen endorsers had a higher attitude than celebrity

advertisements.

Again, this might be an artifact of the growing belief in citizens as more reliable sources of information and the accele

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

of electronic word of mouth (Krishnamurthy and Dou, 2008). Such credibility also is evident in the escalation of “reali

television shows, where the average citizen is the celebrity.

Interaction Effects

In the original study, strength of argument was important in high- but not in low-involvement conditions. In the curren

the U.K. results showed the opposite. Argument strength was significant for low, rather than high involvement.

The notion that “if you buy something you must like it,” as suggested by the self perception theory (Bern, 1972), coul

applied to the high-involvement group. This also is supported by Krugman’s (1965; 1966–1967) notion that behavior

sometimes comes before attitude.

Equally, the strength of argument being significant in low-involvement conditions is supported by social judgment the

(Sherif and Hovland, 1961), which suggests the uninvolved typically consider a wider range of alternatives. This is am

in the notion that “because I am not involved, I need to be convinced.” More than anything else, this shows that conte

rather than content manipulation—sometimes is more important for low-involvement conditions, disagreeing with the

essential premise of the ELM.

Correlations

In the original study, there was a significant positive correlation between attitude toward the product and likelihood to

purchase in both the high- and low-involvement conditions (although stronger in the high-involvement condition).

In the current study, in Australia and the United States, a more positive attitude toward the object was associated wit

greater likelihood to purchase in low-involvement conditions, with a lower correlation for high-involvement conditions.

Perhaps, the authors of the current study suggest, simply “liking” an advertisement, rather than considering the elabo

considered argument, leads to purchase in low-involvement conditions.

This result also could be explained by newer models of thinking, such as “Thinking Fast and Slow” (Kahneman, 2011

Thinking fast (or “System 1 thinking”) is typical of low-involvement conditions, where thinking is automatic, and t

emotion where “something happens to you” produces an automatic response, free from voluntary control. In the

these findings, automatic thinking generates intention to purchase.

More effortful or slow thinking—perhaps akin to high elaboration—only is activated when System 1 thinking doe

have an answer or when its model of the world is violated.

Low attention has been the focus of much scholarly work (Heath, 2012). It suggests that television advertising is not

processed systematically, but rather like System 1, it is automatically processed in response to stimuli.

Advertisements high in emotional content generally received 20 percent less attention (Heathet al., 2009). Lower attention

could reduce counter-argument and, therefore, increase likelihood of purchase.

In summary, the results of this three-study replication diverge from the premise of the ELM model. In all instances, the res

went through an evaluation process, albeit through two different pathways. However, the findings do support the contentio

recent research that there can be learning (and even persuasion) as a result of subconscious processing of advertising ex

suggesting exposure may be more important than processing (Heath, 2012; Kahneman, 2011).

IMPLICATIONS

The current authors believe that the current study has a number of implications for both academics and practitioners:

Replication should be an inherent and ongoing part of theory validation.

As an objective akin to finding a way to “world peace,” revisiting and replicating advertising theory is an overwhelming tas

likely that such efforts will upset a number of academicians who have built their entire careers on following the dictates of

literature.” The results of the current study and the directives of a number of academics, however—among them, many of

participants at Wharton Conference on Empirical Generalizations in Advertising—validate the urgent need to take on this

Journal editors and reviewers should lead the way.

As guardians of research quality, editors and reviewers have an obligation to question the rigor and the appropriate use o

television shows, where the average citizen is the celebrity.

Interaction Effects

In the original study, strength of argument was important in high- but not in low-involvement conditions. In the curren

the U.K. results showed the opposite. Argument strength was significant for low, rather than high involvement.

The notion that “if you buy something you must like it,” as suggested by the self perception theory (Bern, 1972), coul

applied to the high-involvement group. This also is supported by Krugman’s (1965; 1966–1967) notion that behavior

sometimes comes before attitude.

Equally, the strength of argument being significant in low-involvement conditions is supported by social judgment the

(Sherif and Hovland, 1961), which suggests the uninvolved typically consider a wider range of alternatives. This is am

in the notion that “because I am not involved, I need to be convinced.” More than anything else, this shows that conte

rather than content manipulation—sometimes is more important for low-involvement conditions, disagreeing with the

essential premise of the ELM.

Correlations

In the original study, there was a significant positive correlation between attitude toward the product and likelihood to

purchase in both the high- and low-involvement conditions (although stronger in the high-involvement condition).

In the current study, in Australia and the United States, a more positive attitude toward the object was associated wit

greater likelihood to purchase in low-involvement conditions, with a lower correlation for high-involvement conditions.

Perhaps, the authors of the current study suggest, simply “liking” an advertisement, rather than considering the elabo

considered argument, leads to purchase in low-involvement conditions.

This result also could be explained by newer models of thinking, such as “Thinking Fast and Slow” (Kahneman, 2011

Thinking fast (or “System 1 thinking”) is typical of low-involvement conditions, where thinking is automatic, and t

emotion where “something happens to you” produces an automatic response, free from voluntary control. In the

these findings, automatic thinking generates intention to purchase.

More effortful or slow thinking—perhaps akin to high elaboration—only is activated when System 1 thinking doe

have an answer or when its model of the world is violated.

Low attention has been the focus of much scholarly work (Heath, 2012). It suggests that television advertising is not

processed systematically, but rather like System 1, it is automatically processed in response to stimuli.

Advertisements high in emotional content generally received 20 percent less attention (Heathet al., 2009). Lower attention

could reduce counter-argument and, therefore, increase likelihood of purchase.

In summary, the results of this three-study replication diverge from the premise of the ELM model. In all instances, the res

went through an evaluation process, albeit through two different pathways. However, the findings do support the contentio

recent research that there can be learning (and even persuasion) as a result of subconscious processing of advertising ex

suggesting exposure may be more important than processing (Heath, 2012; Kahneman, 2011).

IMPLICATIONS

The current authors believe that the current study has a number of implications for both academics and practitioners:

Replication should be an inherent and ongoing part of theory validation.

As an objective akin to finding a way to “world peace,” revisiting and replicating advertising theory is an overwhelming tas

likely that such efforts will upset a number of academicians who have built their entire careers on following the dictates of

literature.” The results of the current study and the directives of a number of academics, however—among them, many of

participants at Wharton Conference on Empirical Generalizations in Advertising—validate the urgent need to take on this

Journal editors and reviewers should lead the way.

As guardians of research quality, editors and reviewers have an obligation to question the rigor and the appropriate use o

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

in research. Hence, many academic journals and associations have championed research quality.

Kent Monroe, then editor of theJournal of Consumer Research, was a lone voice for replication in the 1990s, promoting a

clear editorial policy of encouraging and accepting replication research for publication.

TheJournal of Advertising Researchhas encouraged debate with its “New Models for a New Age of Research” issue (Vo

51, Issue 2) and “Future of Market Research” (Vol. 51, Issue 1; 2011)

Charles Taylor,International Journal of Advertisingeditor, confirmed the journal’s commitment to research involving

replication, publishing a call for stronger theory development and more relevant research for advertising professional

(Taylor, 2011).

Academic associations must work together.

The American Academy of Advertising and European Advertising Academy both have considered the topic of research qu

worthy enough to feature it in their keynote addresses. Action must follow awareness, however: If the agenda is to revisit

advertising theory—and if editors and reviewers are the guardians of research quality—academic associations should pro

necessary leadership to support that view.

Practitioners should document the practice of theory.

It is contingent upon practitioners—the implementers of advertising theory—to document conditions under which theory w

those conditions that oppose it. Their findings should be published in peer-reviewed journals, where practitioners and aca

can learn from the practice of theory.

Advertising is not always a rational process.

Practitioners should not be constrained by an organizational view that sees advertising as a manageable, informational re

for rational consumers (Heath, 2012). They should embrace new technology (such as neuroscience) and new thinking (lik

Thinking, Fast and Slow[Kahneman, 2011] or even more emotion-centric ideas (like implicit communication or low attention)

These all are concepts more challenging than a central route to persuasion but perhaps better reflective of today’s consum

today’s marketplace.

CONCLUSION

To question the relevance of advertising theory, the current study empirically tested its most cited work, the ELM (Pettyet al.,

1983).

What those scholars found in 1983 could not be replicated today in any of three countries in which the current study was

conducted. This global inability to replicate one of the most fundamental experiments from advertising’s halcyon mass-me

suggests advertising scholars need to re-think the assumptions and foundations of what they call “advertising theory.”

Just because it has been cited a number of times and “everyone” believes it to be true does not necessarily mean a theor

relevant or even empirically generalizable given the massive changes that have occurred in the marketplace.

The onus is on the marketing-research industry and academia to question advertising theory: When everything around it h

changed, why should any particular theory stay the same? And if advertising theory is not questioned, subsequent adverti

research will become increasingly irrelevant.

References

Azjen, I. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.”Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes80 (1991): 179–211.

Beard, F. “Peer Evaluation and Readership of Influential Contributions to the Advertising Literature.”Journal of Advertising31, 4

(2002): 65–75.

Berger, A.Essentials of Mass Communication Theory, London, UK: Sage Publications, 1995.

Bern, D. “Self-Perception Theory.” InAdvances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 6, L. Berkowitz, ed. New York: Academic

Press, 1972.

Bogart, L. “Progress in Advertising Research?”Journal of Advertising ResearchJune/July (1986): 11–15.

Cole, C., R. Ettenson, S. Reinke, and T. Schrader. “The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM): Replications, Extensions, an

Kent Monroe, then editor of theJournal of Consumer Research, was a lone voice for replication in the 1990s, promoting a

clear editorial policy of encouraging and accepting replication research for publication.

TheJournal of Advertising Researchhas encouraged debate with its “New Models for a New Age of Research” issue (Vo

51, Issue 2) and “Future of Market Research” (Vol. 51, Issue 1; 2011)

Charles Taylor,International Journal of Advertisingeditor, confirmed the journal’s commitment to research involving

replication, publishing a call for stronger theory development and more relevant research for advertising professional

(Taylor, 2011).

Academic associations must work together.

The American Academy of Advertising and European Advertising Academy both have considered the topic of research qu

worthy enough to feature it in their keynote addresses. Action must follow awareness, however: If the agenda is to revisit

advertising theory—and if editors and reviewers are the guardians of research quality—academic associations should pro

necessary leadership to support that view.

Practitioners should document the practice of theory.

It is contingent upon practitioners—the implementers of advertising theory—to document conditions under which theory w

those conditions that oppose it. Their findings should be published in peer-reviewed journals, where practitioners and aca

can learn from the practice of theory.

Advertising is not always a rational process.

Practitioners should not be constrained by an organizational view that sees advertising as a manageable, informational re

for rational consumers (Heath, 2012). They should embrace new technology (such as neuroscience) and new thinking (lik

Thinking, Fast and Slow[Kahneman, 2011] or even more emotion-centric ideas (like implicit communication or low attention)

These all are concepts more challenging than a central route to persuasion but perhaps better reflective of today’s consum

today’s marketplace.

CONCLUSION

To question the relevance of advertising theory, the current study empirically tested its most cited work, the ELM (Pettyet al.,

1983).

What those scholars found in 1983 could not be replicated today in any of three countries in which the current study was

conducted. This global inability to replicate one of the most fundamental experiments from advertising’s halcyon mass-me

suggests advertising scholars need to re-think the assumptions and foundations of what they call “advertising theory.”

Just because it has been cited a number of times and “everyone” believes it to be true does not necessarily mean a theor

relevant or even empirically generalizable given the massive changes that have occurred in the marketplace.

The onus is on the marketing-research industry and academia to question advertising theory: When everything around it h

changed, why should any particular theory stay the same? And if advertising theory is not questioned, subsequent adverti

research will become increasingly irrelevant.

References

Azjen, I. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.”Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes80 (1991): 179–211.

Beard, F. “Peer Evaluation and Readership of Influential Contributions to the Advertising Literature.”Journal of Advertising31, 4

(2002): 65–75.

Berger, A.Essentials of Mass Communication Theory, London, UK: Sage Publications, 1995.

Bern, D. “Self-Perception Theory.” InAdvances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 6, L. Berkowitz, ed. New York: Academic

Press, 1972.

Bogart, L. “Progress in Advertising Research?”Journal of Advertising ResearchJune/July (1986): 11–15.

Cole, C., R. Ettenson, S. Reinke, and T. Schrader. “The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM): Replications, Extensions, an

Conflicting Findings.”Advances in Consumer Research17 (1990): 231–236.

Earley. S. “Mobile Commerce: A Broader Perspective.”IEEE Computer Society16, May–June (2014): 61–65.

Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. “Attitudes and Opinions.”Annual Review of Psychology23 (1972): 487–544.

Haugtvedt, C., and R. Petty. “Need for Cognition and Attitude Persistence.”Advances in Consumer Research16 (1989): 33–36.

Heath, R.Seducing the Subconscious: The Psychology of Emotional Influence in Advertising. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-

Blackwell, 2012.

Heath, R., and P. Feldwick. “Fifty Years Using the Wrong Model of Advertising.”International Journal of Market Research50, 1

(2008): 29–59.

Hofstede, G. “The Hofstede Centre.” Retrieved April 14, 2014, fromhttp://geert-hofstede.com/australia.html

Jain, V., and S. Pant. “Navigating Generation Y for Effective Mobile Marketing in India: A Conceptual Framework.”International

Journal of Mobile Marketing7, 3 (2012): 17–26.

Johnson, B., and A. Eagly. “Effects of Involvement on Persuasion: A Meta-Analysis.”Psychological Bulletin106, 2 (1989): 290–

314.

Kahneman, D.Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Girous. 2011.

Kang, Y., and P. Herr. “Beauty and the Beholder: Toward an Integrative Model of Communication Source Effects.”Journal of

Consumer Research33 (2006): 123–130.

Kerr, G., and D. Schultz. “Maintenance Man or Architect? The Role of Academic Advertising Research in Building Better

Understanding.”International Journal of Advertising29, 4 (2010): 547–568.

Kitchen, P. J., and E. Uzunoglu (Eds.).Integrated Communications in the Postmodern Era. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

2015.

Kitchen, P. J., G. Kerr, D. Schultz, R. McColl, R., and H. Pals. “The Elaboration Likelihood Model: Review, Critique and R

Agenda.”European Journal of Marketing48, 11-12 (2014): 2033–2050.

Krugman, H.E. “The Impact of Television Advertising: Learning Without Involvement.”Public Opinion Quarterly29 (1965): 349–

356.

Krugman, H.E. “The Measurement of Advertising Involvement.”Public Opinion Quarterly30 (1966-1967): 583–596.

Krishnamurthya, S., and W. Dou. “Advertising with User-Generated Content: A Framework and Research Agenda.”Journal of

Interactive Advertising8, 2 (2008): 1–4.

McCauley, E., and T. Donofrio. “Apparatus, System and Methods for Stimulating and Securing Retail Transactions.”Patent

Application Publication, 43, August 7 (2014): 783–791.

Monroe, K. “Editorial—On Replications in Consumer Research: Part 2,”Journal of Consumer Research, 19, September (1992):

Preface.

O’Keefe, D.Persuasion: Theory and Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1990.

Pasadeos, Y., J. Phelps, and A. Edison. “Searching for Our “Own Theory” in Advertising: An Update of Research Network

Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly85, 4 (2008): 785–806.

Petty, R., and J. Cacioppo.Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown

Company Publishers, 1981.

Petty, R., and J. Cacioppo. “Central and Peripheral Routes to Persuasion: Application to Advertising.” InAdvertising and

Consumer Psychology, L. Percy and A. G. Woodside, eds. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1983.

Petty, R., J. Cacioppo, and D. Schumann. “Central and Peripheral Routes to Advertising Effectiveness: The Moderating R

Involvement.”Journal of Consumer Research10 (1983): 135–146.

Earley. S. “Mobile Commerce: A Broader Perspective.”IEEE Computer Society16, May–June (2014): 61–65.

Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. “Attitudes and Opinions.”Annual Review of Psychology23 (1972): 487–544.

Haugtvedt, C., and R. Petty. “Need for Cognition and Attitude Persistence.”Advances in Consumer Research16 (1989): 33–36.

Heath, R.Seducing the Subconscious: The Psychology of Emotional Influence in Advertising. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-

Blackwell, 2012.

Heath, R., and P. Feldwick. “Fifty Years Using the Wrong Model of Advertising.”International Journal of Market Research50, 1