Non-Tariff Barriers, Integration, and the Trans-Atlantic Economy

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

|40

|15481

|477

AI Summary

This paper discusses the impact of Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership Agreement (T-TIP) on non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for goods and services, liberalization of public procurement markets, and greater cooperation on market regulation. It also highlights the challenges in removing NTBs and the role of distributive politics in trade negotiations. The paper uses structural gravity modeling to estimate possible trade cost reductions under T-TIP and discusses the potential economic impact on third countries.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Non-Tariff Barriers, Integration, and

the Trans-Atlantic Economy

Peter Egger

ETH Zurich, CESifo, and CEPR

Joseph Francois

University of Bern and CEPR

Miriam Manchin

University College London

Doug Nelson

Tulane University

June 2014

Abstract:

the Trans-Atlantic Economy

Peter Egger

ETH Zurich, CESifo, and CEPR

Joseph Francois

University of Bern and CEPR

Miriam Manchin

University College London

Doug Nelson

Tulane University

June 2014

Abstract:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1. Introduction

In the wake of the great recession and ancillary financial crises, the European

Union and the United States launched a joint, ambitious effort in 2013 to

negotiate a comprehensive trade and investment agreement. Known as the

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership Agreement (T-TIP), the

negotiation process that has ensued is supposed to bring about tariff-free trade

in goods, reduction of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for goods and services,

liberalization of public procurement markets, and greater cooperation on market

regulation. Systemically, the negotiations have been characterized as both an

important step forward for the multilateral trading system, and an existential

threat to that same system. Given that the EU and US account collectively for a

substantial share of global production and world trade in goods and services,

these negotiations have the potential for a major economic impact on third

countries.

At this stage, the shape and coverage of a final T-TIP agreement remain

uncertain. Indeed, the T-TIP would actually be as a set of trade agreements.

While the negotiations are formally bilateral, the agenda means that they entail

the 50 States in the US and the 28 Members of the EU. A successful agreement

needs to take into account particularities of a great number of different partners

and thus on substance amounts to a new type of mini-lateral agreement. It also

needs to cover areas ranging from broad tariff concessions to sector-specific

questions of regulation. While tariff reductions are relatively straightforward, an

important ambition under T-TIP actually relates to greater coherence and

convergence of regulatory standards. Any progress on regulatory convergence

(and better cross-recognition of standards) would require enhanced cooperation

in rule making. As such the agenda is not as straightforward as tariff elimination.

Indeed, there is growing recognition that a successful T-TIP agreement would

likely combine rapid liberalization in some areas (such as tariffs) with

institutional mechanisms set up to allow progressive, long run liberalization in

1

In the wake of the great recession and ancillary financial crises, the European

Union and the United States launched a joint, ambitious effort in 2013 to

negotiate a comprehensive trade and investment agreement. Known as the

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership Agreement (T-TIP), the

negotiation process that has ensued is supposed to bring about tariff-free trade

in goods, reduction of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for goods and services,

liberalization of public procurement markets, and greater cooperation on market

regulation. Systemically, the negotiations have been characterized as both an

important step forward for the multilateral trading system, and an existential

threat to that same system. Given that the EU and US account collectively for a

substantial share of global production and world trade in goods and services,

these negotiations have the potential for a major economic impact on third

countries.

At this stage, the shape and coverage of a final T-TIP agreement remain

uncertain. Indeed, the T-TIP would actually be as a set of trade agreements.

While the negotiations are formally bilateral, the agenda means that they entail

the 50 States in the US and the 28 Members of the EU. A successful agreement

needs to take into account particularities of a great number of different partners

and thus on substance amounts to a new type of mini-lateral agreement. It also

needs to cover areas ranging from broad tariff concessions to sector-specific

questions of regulation. While tariff reductions are relatively straightforward, an

important ambition under T-TIP actually relates to greater coherence and

convergence of regulatory standards. Any progress on regulatory convergence

(and better cross-recognition of standards) would require enhanced cooperation

in rule making. As such the agenda is not as straightforward as tariff elimination.

Indeed, there is growing recognition that a successful T-TIP agreement would

likely combine rapid liberalization in some areas (such as tariffs) with

institutional mechanisms set up to allow progressive, long run liberalization in

1

others. Such institutional mechanisms, if they offer solutions that can be

translated to other situations, might then offer solutions to a broader set of

countries that are also grappling with regulatory barriers to trade and

investment. Alternatively, there is legitimate worry that they may instead offer

new channels for discriminatory management of trade and investment flows.

The T-TIP is attention grabbing, in part, simply because of the magnitudes

involved. From Table 1-1, together the two T-TIP partners accounted for 46

percent of global GDP and almost 60 percent of world trade. Yet most of this

trade is not actually trans-Atlantic trade. Rather, despite their collective shares

of world production and trade, trade flows between the two blocks is relatively

low compared to their trade with other regions. This is again illustrated in the

data in Table 1-1, but perhaps better visualized with Figure 1-1. Focusing first on

directions of trade, the US has far more trade with Asia than it does with Europe.

Asia counts for almost 60 percent of US exports and imports. Similarly, the

region accounts for roughly 39 percent of EU exports and imports. Other upper

and middle-income countries (Canada and Mexico primarily for the US, and

EFTA and the Euro-Med economies for the EU) account for most of remaining

trade.

To appreciate the context of T-TIP, both for the EU and US, but also for third

countries, it is also useful to focus on trade intensity, reported in the Figure 1-1 as

trade scaled by partner GDP. For example, EU and US trade with the world is

valued at roughly 13 percent of global GDP. This means that for each $100

billion in global income, we see $13.3 billion in trade involving the EU and/or the

US. In the case of Asia, for every $100 billion in GDP, there is $9.9 billion in trade

(exports and imports) with the US, and $7.6 billion in trade with the EU. Asian

trade with the EU and US combined is therefore worth 17.6 percent of Asian

GDP.1 Stark asymmetries are evident, especially with low-income countries.

For low-income countries, while trade with the US and EU is worth 18.3 percent

of their GDP, its worth roughly 0.2 percent of EU and US GDP.

1 We are fully aware that scaling trade by GDP is not the same thing as quantifying the impact on

GDP. It does however provide a useful metric for comparison.

2

translated to other situations, might then offer solutions to a broader set of

countries that are also grappling with regulatory barriers to trade and

investment. Alternatively, there is legitimate worry that they may instead offer

new channels for discriminatory management of trade and investment flows.

The T-TIP is attention grabbing, in part, simply because of the magnitudes

involved. From Table 1-1, together the two T-TIP partners accounted for 46

percent of global GDP and almost 60 percent of world trade. Yet most of this

trade is not actually trans-Atlantic trade. Rather, despite their collective shares

of world production and trade, trade flows between the two blocks is relatively

low compared to their trade with other regions. This is again illustrated in the

data in Table 1-1, but perhaps better visualized with Figure 1-1. Focusing first on

directions of trade, the US has far more trade with Asia than it does with Europe.

Asia counts for almost 60 percent of US exports and imports. Similarly, the

region accounts for roughly 39 percent of EU exports and imports. Other upper

and middle-income countries (Canada and Mexico primarily for the US, and

EFTA and the Euro-Med economies for the EU) account for most of remaining

trade.

To appreciate the context of T-TIP, both for the EU and US, but also for third

countries, it is also useful to focus on trade intensity, reported in the Figure 1-1 as

trade scaled by partner GDP. For example, EU and US trade with the world is

valued at roughly 13 percent of global GDP. This means that for each $100

billion in global income, we see $13.3 billion in trade involving the EU and/or the

US. In the case of Asia, for every $100 billion in GDP, there is $9.9 billion in trade

(exports and imports) with the US, and $7.6 billion in trade with the EU. Asian

trade with the EU and US combined is therefore worth 17.6 percent of Asian

GDP.1 Stark asymmetries are evident, especially with low-income countries.

For low-income countries, while trade with the US and EU is worth 18.3 percent

of their GDP, its worth roughly 0.2 percent of EU and US GDP.

1 We are fully aware that scaling trade by GDP is not the same thing as quantifying the impact on

GDP. It does however provide a useful metric for comparison.

2

Figure 1-1 Composition of Trade by Destination

note: trade excludes intra-EU flows. sources: IMF, COMTRADE, GTAP9.

Viewed in this context, though the EU and US account for high shares of GDP and

trade, in a sense the flows between them seem relatively low. For example,

while in Asia each $100 billion in exports is associated with $17.6 billion in trade

with the EU and/or the US, a similar figure for the EU and US themselves tells us

that for each $100 billion in transatlantic GDP, we see only $2.7 billion in trade in

goods and services. In other words, scaled by GDP, the EU and US both have

much more intense trade relationships with other countries and regions than

they do with each other. Much of this is may be explained by economic structure.

Both economies are mature, with high GDP shares derived from services: 75

percent of the EU value added is in services; 82.3 percent of US value added is in

services. As services are less traded, this helps explain the lower bilateral flows.

Such factors should be controlled for when we turn to gravity modelling, as

otherwise we may mislead ourselves into thinking low trade intensity means

high trade barriers. Yet even controlling for such factors, at this stage we should

already note the sense reflected in the negotiating mandate that transatlantic

trade underperforms. The logic is that with shifts in technology and organization

3

note: trade excludes intra-EU flows. sources: IMF, COMTRADE, GTAP9.

Viewed in this context, though the EU and US account for high shares of GDP and

trade, in a sense the flows between them seem relatively low. For example,

while in Asia each $100 billion in exports is associated with $17.6 billion in trade

with the EU and/or the US, a similar figure for the EU and US themselves tells us

that for each $100 billion in transatlantic GDP, we see only $2.7 billion in trade in

goods and services. In other words, scaled by GDP, the EU and US both have

much more intense trade relationships with other countries and regions than

they do with each other. Much of this is may be explained by economic structure.

Both economies are mature, with high GDP shares derived from services: 75

percent of the EU value added is in services; 82.3 percent of US value added is in

services. As services are less traded, this helps explain the lower bilateral flows.

Such factors should be controlled for when we turn to gravity modelling, as

otherwise we may mislead ourselves into thinking low trade intensity means

high trade barriers. Yet even controlling for such factors, at this stage we should

already note the sense reflected in the negotiating mandate that transatlantic

trade underperforms. The logic is that with shifts in technology and organization

3

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

of production toward more global and regional value chains that cross

international borders, behind the border issues whose trade cost impacts were

once second or third order are increasingly important. Without necessarily

changing policy, what were once domestic regulatory issues have emerged as

potential sources of NTB-related trade costs in a world of international

production and associated returns to scale. To some extent, the US has dealt

with these changes in NAFTA with respect to its North American partners

(especially for motor vehicles). The same holds for Europe in the context of the

EU single market. The T-TIP is approached with the combined NAFTA and EU

single market experience helping to frame the current negotiations on regulatory

divergence and mutual recognition of standards.

We have organized our discussion as follows. In Section 2, we focus first on

important qualitative issues (i.e. things we do not try to quantify primarily

because we can’t) that help frame the more quantitative analysis that follows. In

Section 3, we then turn to structural gravity modelling (i.e. estimating equations

based on the trade equations in our computational model introduced in Section

4) to control for factors like economic structure and both physical and cultural

distance that affect trade flows. On this basis, we gauge possible trade cost

reductions under T-TIP, based on a mix of past experience with regional trade

agreements (RTAs) with respect to goods trade, firm-based evidence on goods-

based trade costs not addressed by past RTAs, and recent data from the World

Bank, OECD, and WTO on services barriers and recent services commitments.

With trade cost estimates in hand, we then turn to a computational model of the

world economy in Section 4. This model reflects actual production and trade in

2011. On this basis, we discuss possible impacts of T-TIP based trade cost

reductions for the EU and US economies, but also for third countries. Concluding

comments, thoughts, and ruminations are offered in Section 5.

4

international borders, behind the border issues whose trade cost impacts were

once second or third order are increasingly important. Without necessarily

changing policy, what were once domestic regulatory issues have emerged as

potential sources of NTB-related trade costs in a world of international

production and associated returns to scale. To some extent, the US has dealt

with these changes in NAFTA with respect to its North American partners

(especially for motor vehicles). The same holds for Europe in the context of the

EU single market. The T-TIP is approached with the combined NAFTA and EU

single market experience helping to frame the current negotiations on regulatory

divergence and mutual recognition of standards.

We have organized our discussion as follows. In Section 2, we focus first on

important qualitative issues (i.e. things we do not try to quantify primarily

because we can’t) that help frame the more quantitative analysis that follows. In

Section 3, we then turn to structural gravity modelling (i.e. estimating equations

based on the trade equations in our computational model introduced in Section

4) to control for factors like economic structure and both physical and cultural

distance that affect trade flows. On this basis, we gauge possible trade cost

reductions under T-TIP, based on a mix of past experience with regional trade

agreements (RTAs) with respect to goods trade, firm-based evidence on goods-

based trade costs not addressed by past RTAs, and recent data from the World

Bank, OECD, and WTO on services barriers and recent services commitments.

With trade cost estimates in hand, we then turn to a computational model of the

world economy in Section 4. This model reflects actual production and trade in

2011. On this basis, we discuss possible impacts of T-TIP based trade cost

reductions for the EU and US economies, but also for third countries. Concluding

comments, thoughts, and ruminations are offered in Section 5.

4

Table 1-1 GDP and Trade Orientation, 2011

US EU EU & US

EU-US GDP

billion dollars 14,991 17,645 32,636

share of world GDP 21.3 25.1 46.3

Trade with world

billion dollars 4,096 5,036 8,241

share of world trade 29.4 36.2 59.3

share of own GDP 27.3 28.5 25.3

share of world GDP 5.8 7.2 13.0

Trade between EU & US

billion dollars 891 891 891

share of own GDP 5.9 5.0 2.7

share of partner GDP 5.0 5.9 2.7

share of world trade 6.4 6.4 6.4

share of own trade 21.7 17.7 10.8

Trade with Asia, Pacific

billion dollars 2,443 1,945 4,388

share of own GDP 16.3 11.0 13.4

share of partner GDP 9.9 7.7 17.6

share of world trade 17.6 14.0 31.5

share of own trade 59.6 38.6 53.2

Trade with other upper &

middle income countries

billion dollars 740 2,142 2,882

share of own GDP 4.9 12.1 8.8

share of partner GDP 5.9 17.0 22.8

share of world trade 5.3 15.4 20.7

share of own trade 18.1 42.5 35.0

Trade with low income countries

billion dollars 22 58 80

share of own GDP 0.1 0.3 0.2

share of partner GDP 5.0 13.3 18.3

share of world trade 0.2 0.4 0.6

share of own trade 0.5 1.2 1.0

note: trade excludes intra-EU flows. sources: IMF, COMTRADE, GTAP9.

5

US EU EU & US

EU-US GDP

billion dollars 14,991 17,645 32,636

share of world GDP 21.3 25.1 46.3

Trade with world

billion dollars 4,096 5,036 8,241

share of world trade 29.4 36.2 59.3

share of own GDP 27.3 28.5 25.3

share of world GDP 5.8 7.2 13.0

Trade between EU & US

billion dollars 891 891 891

share of own GDP 5.9 5.0 2.7

share of partner GDP 5.0 5.9 2.7

share of world trade 6.4 6.4 6.4

share of own trade 21.7 17.7 10.8

Trade with Asia, Pacific

billion dollars 2,443 1,945 4,388

share of own GDP 16.3 11.0 13.4

share of partner GDP 9.9 7.7 17.6

share of world trade 17.6 14.0 31.5

share of own trade 59.6 38.6 53.2

Trade with other upper &

middle income countries

billion dollars 740 2,142 2,882

share of own GDP 4.9 12.1 8.8

share of partner GDP 5.9 17.0 22.8

share of world trade 5.3 15.4 20.7

share of own trade 18.1 42.5 35.0

Trade with low income countries

billion dollars 22 58 80

share of own GDP 0.1 0.3 0.2

share of partner GDP 5.0 13.3 18.3

share of world trade 0.2 0.4 0.6

share of own trade 0.5 1.2 1.0

note: trade excludes intra-EU flows. sources: IMF, COMTRADE, GTAP9.

5

2. Regulation, politics, and keeping NTBs in context

It should be stressed that in contrast to reducing tariffs, the removal of NTBs is

not so straightforward. There are many different reasons and sources for NTBs.

Some are unintentional barriers while others reflect deliberate public policy. As

such, for many NTBs, removing them is not possible because, for example, they

require constitutional changes, unrealistic legislative changes, or unrealistic

technical changes. Removing NTBs may also be difficult politically, for example

because there is a lack of sufficient economic benefit to support the effort;

because the set of regulations is too broad; or because consumer preferences or

language preclude a change. Indeed even where public perception is not

congruent with scientific evidence, we need to keep in mind that it's the public

that votes, not the evidence. In recognition of these difficulties, we follow recent

studies by focusing on the set of possible NTB reductions (known as “actionable”

NTBs) given that many will remain in place. Of those NTBs that can feasibly be

reduced, we focus on different levels of ambition for NTB reduction.2

This raises the issue of what might we plausibly expect to be the result of a

successful T-TIP negotiation. In addition to differences over matters of fact

(economics as a body of knowledge is far from settled on many positive issues

with respect to what drives outcomes in national economies and their

relationship to other economies), we expect difficulties to arise over matters of

genuine differences in social goals and the way those goals are embedded in

national legal orders and we also expect outcomes to be affected by distributive

struggles in the national (and in the case of the EU, in the Community level)

political arena.

2 In benchmarking studies leading into the T-TIP talks, such as ECORYS (2009), there was a

strident debate between regulators and trade officials centred on semantics and acronyms. One

man’s barrier is another man’s reasonable measure, or in other words regulatory measures

might not be deliberate barriers. While noting the importance of this distinction in some circles,

for simplicity here we will call all regulatory and non-tariff instruments that impede trade as

non-tariff barriers (NTBs) while recognizing that some of these are perfectly legitimate

measures, and in such cases the less pejorative term perhaps ought to be non-tariff measures

(NTMs). Calling them all NTBs, we focus instead on dividing the trade-restricting aspects of all

measures into those that can be reduced and those that cannot, defined elsewhere in this paper

as “actionable” and “non-actionable” NTBs.

6

It should be stressed that in contrast to reducing tariffs, the removal of NTBs is

not so straightforward. There are many different reasons and sources for NTBs.

Some are unintentional barriers while others reflect deliberate public policy. As

such, for many NTBs, removing them is not possible because, for example, they

require constitutional changes, unrealistic legislative changes, or unrealistic

technical changes. Removing NTBs may also be difficult politically, for example

because there is a lack of sufficient economic benefit to support the effort;

because the set of regulations is too broad; or because consumer preferences or

language preclude a change. Indeed even where public perception is not

congruent with scientific evidence, we need to keep in mind that it's the public

that votes, not the evidence. In recognition of these difficulties, we follow recent

studies by focusing on the set of possible NTB reductions (known as “actionable”

NTBs) given that many will remain in place. Of those NTBs that can feasibly be

reduced, we focus on different levels of ambition for NTB reduction.2

This raises the issue of what might we plausibly expect to be the result of a

successful T-TIP negotiation. In addition to differences over matters of fact

(economics as a body of knowledge is far from settled on many positive issues

with respect to what drives outcomes in national economies and their

relationship to other economies), we expect difficulties to arise over matters of

genuine differences in social goals and the way those goals are embedded in

national legal orders and we also expect outcomes to be affected by distributive

struggles in the national (and in the case of the EU, in the Community level)

political arena.

2 In benchmarking studies leading into the T-TIP talks, such as ECORYS (2009), there was a

strident debate between regulators and trade officials centred on semantics and acronyms. One

man’s barrier is another man’s reasonable measure, or in other words regulatory measures

might not be deliberate barriers. While noting the importance of this distinction in some circles,

for simplicity here we will call all regulatory and non-tariff instruments that impede trade as

non-tariff barriers (NTBs) while recognizing that some of these are perfectly legitimate

measures, and in such cases the less pejorative term perhaps ought to be non-tariff measures

(NTMs). Calling them all NTBs, we focus instead on dividing the trade-restricting aspects of all

measures into those that can be reduced and those that cannot, defined elsewhere in this paper

as “actionable” and “non-actionable” NTBs.

6

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Consider first distributive politics. There is now a sizable literature, in

Economics and Political Science, on the ways political struggles over the returns

to trade (and the losses realized by particular households and sectors in both the

short- and long-run) affect the outcomes of domestic trade politics and, more

relevant for the purposes of this paper, the outcomes of trade negotiations

(Grossman and Helpman, 1995a, b, Ornelas, 2005a). The usual goal of political

economy papers in general is to explain deviations from optimal policies, so it is

not surprising that most of this work emphasizes how politics cause deviations

from “Liberal trade“(Krishna, 1998, Levy, 1997, Ornelas, 2005b). 3 Certainly in

the case of T-TIP there is no shortage of special interests in both the US and

Europe seeking to use the negotiations to either increase access to foreign

markets or reduce access to domestic markets. In this paper we identify sectors

that may gain and lose from liberalization of trade between the US and the EU,

and it should not surprise us to discover that those sectors are actively lobbying

their governments on those issues.4

At the same time, contemporary negotiations between the EU and the US take

place in a context that offers interesting differences relative to expectations

based on standard models. Most obviously, a substantial amount of trade

between the US and the EU takes place in differentiated intermediate goods

along the lines of Ethier (1982). At least since the classic paper of Balassa

(1966), intra-industry trade (IIT) has been seen as less disruptive than inter-

industry trade (Brülhart, 2002, Dixon and Menon, 1997, Menon and Dixon, 1997)

and while this inference is not as well-grounded theoretically as we tend to think

(Lovely and Nelson, 2000, 2002), there appears to be empirical support for the

claim.5 Thus, just as integration among the early members of what became the

EU was eased by the relatively low adjustment costs to liberalization of trade, the

3 Though Ethier (Ethier, 1998, 2001) and Ornelas (Ornelas, 2005a, 2008) are exceptions here.

4 For example, US cultural industries seek strong intellectual property protections and increased

access to European markets, while European producers in these sectors seek exemptions to

protect national culture. An interesting case we note below is the US financial sector, which

seeks regulatory harmonization not only to increase its presence in Europe but, perhaps more

importantly, to secure reduced domestic regulation.

5 Consistent with Lovely and Nelson (2000, 2002), Trefler (2004) finds that rationalization

effects dominate in the long-run, but that short-term adjustment induced by rationalization

involve non-trivial costs in the short-run.

7

Economics and Political Science, on the ways political struggles over the returns

to trade (and the losses realized by particular households and sectors in both the

short- and long-run) affect the outcomes of domestic trade politics and, more

relevant for the purposes of this paper, the outcomes of trade negotiations

(Grossman and Helpman, 1995a, b, Ornelas, 2005a). The usual goal of political

economy papers in general is to explain deviations from optimal policies, so it is

not surprising that most of this work emphasizes how politics cause deviations

from “Liberal trade“(Krishna, 1998, Levy, 1997, Ornelas, 2005b). 3 Certainly in

the case of T-TIP there is no shortage of special interests in both the US and

Europe seeking to use the negotiations to either increase access to foreign

markets or reduce access to domestic markets. In this paper we identify sectors

that may gain and lose from liberalization of trade between the US and the EU,

and it should not surprise us to discover that those sectors are actively lobbying

their governments on those issues.4

At the same time, contemporary negotiations between the EU and the US take

place in a context that offers interesting differences relative to expectations

based on standard models. Most obviously, a substantial amount of trade

between the US and the EU takes place in differentiated intermediate goods

along the lines of Ethier (1982). At least since the classic paper of Balassa

(1966), intra-industry trade (IIT) has been seen as less disruptive than inter-

industry trade (Brülhart, 2002, Dixon and Menon, 1997, Menon and Dixon, 1997)

and while this inference is not as well-grounded theoretically as we tend to think

(Lovely and Nelson, 2000, 2002), there appears to be empirical support for the

claim.5 Thus, just as integration among the early members of what became the

EU was eased by the relatively low adjustment costs to liberalization of trade, the

3 Though Ethier (Ethier, 1998, 2001) and Ornelas (Ornelas, 2005a, 2008) are exceptions here.

4 For example, US cultural industries seek strong intellectual property protections and increased

access to European markets, while European producers in these sectors seek exemptions to

protect national culture. An interesting case we note below is the US financial sector, which

seeks regulatory harmonization not only to increase its presence in Europe but, perhaps more

importantly, to secure reduced domestic regulation.

5 Consistent with Lovely and Nelson (2000, 2002), Trefler (2004) finds that rationalization

effects dominate in the long-run, but that short-term adjustment induced by rationalization

involve non-trivial costs in the short-run.

7

sizable role of IIT in US-EU trade may similarly reduce adjustment cost-driven

distributive politics. Similarly, the opportunity to rationalize nationally

organized production on an international basis in sectors like motor vehicles,

steel, and chemicals should produce support for integration where opposition is

predicted in standard models. Consistent with this observation, the European

motor vehicle industry is strongly behind the T-TIP (they have been primary

drivers of political support, so to speak) while they were adamantly opposed to

the EU-Korea agreement and are opposed to an EU-Japan agreement as well. In

the first case, the most of the same firms operate on both sides of the Atlantic

and see opportunity for rationalization, while in the second the situation is closer

to the classic one of opposing firms.6

Distributive politics encourage us to treat opposition to liberalization as cynical

special pleading. However, especially when we turn from straightforwardly

protectionist barriers to trade to harmonization of regulations that are deeply

rooted in domestic understandings of identity, the good life, national safety, et

cetera, this inference becomes increasingly strained, even as self-interested

groups re-purpose such arguments to their own advantage. Thus, while purely

trade policy-related negotiations have become increasingly fraught as a result of

domestic political opposition (witness the lengthening periods to resolution of

multilateral trade agreements and the difficulty of American presidents in

securing trade promotion authority), as soon as we consider issues like

regulatory harmonization with some kind of non-trivial dispute resolution

process, concerns about surrender of sovereignty are added to standard

distributional conflicts. It is tempting to treat all such resistance as thinly veiled

rent seeking, but this is not really a useful way to understand the underlying

politics.7 Consider three cases of relevance to T-TIP: regulation of cultural

6 See for example Ramsey (2012) and Clark (2014). Lobbying is actually more complex, as Asian

manufacturers also produce in the EU, and both Toyota and Hyundai are members of the

European automakers association (ACEA).

7 This is not to say that such rent seeking is not an essential part of the politics of trade policy. It

certainly is. The point is to recognize that when opponents of liberalization refer to sovereignty

concerns, it is precisely because they tap into powerful notions of community norms that they

are effective. Treating them as simply bad faith is neither good politics, nor good analysis. The

inherent difficulty of incorporating such concerns in systematic analysis makes it all the more

8

distributive politics. Similarly, the opportunity to rationalize nationally

organized production on an international basis in sectors like motor vehicles,

steel, and chemicals should produce support for integration where opposition is

predicted in standard models. Consistent with this observation, the European

motor vehicle industry is strongly behind the T-TIP (they have been primary

drivers of political support, so to speak) while they were adamantly opposed to

the EU-Korea agreement and are opposed to an EU-Japan agreement as well. In

the first case, the most of the same firms operate on both sides of the Atlantic

and see opportunity for rationalization, while in the second the situation is closer

to the classic one of opposing firms.6

Distributive politics encourage us to treat opposition to liberalization as cynical

special pleading. However, especially when we turn from straightforwardly

protectionist barriers to trade to harmonization of regulations that are deeply

rooted in domestic understandings of identity, the good life, national safety, et

cetera, this inference becomes increasingly strained, even as self-interested

groups re-purpose such arguments to their own advantage. Thus, while purely

trade policy-related negotiations have become increasingly fraught as a result of

domestic political opposition (witness the lengthening periods to resolution of

multilateral trade agreements and the difficulty of American presidents in

securing trade promotion authority), as soon as we consider issues like

regulatory harmonization with some kind of non-trivial dispute resolution

process, concerns about surrender of sovereignty are added to standard

distributional conflicts. It is tempting to treat all such resistance as thinly veiled

rent seeking, but this is not really a useful way to understand the underlying

politics.7 Consider three cases of relevance to T-TIP: regulation of cultural

6 See for example Ramsey (2012) and Clark (2014). Lobbying is actually more complex, as Asian

manufacturers also produce in the EU, and both Toyota and Hyundai are members of the

European automakers association (ACEA).

7 This is not to say that such rent seeking is not an essential part of the politics of trade policy. It

certainly is. The point is to recognize that when opponents of liberalization refer to sovereignty

concerns, it is precisely because they tap into powerful notions of community norms that they

are effective. Treating them as simply bad faith is neither good politics, nor good analysis. The

inherent difficulty of incorporating such concerns in systematic analysis makes it all the more

8

goods; food safety regulation; and financial regulation. In all of these cases, there

are fundamental differences between parties engaged in the T-TIP negotiations.

Culture is inherently difficult to identify, but it goes to the heart of national

identity. US firms currently dominate the global cultural marketplace. It is easy

to see arguments for globalization as thinly veiled special pleading for US

television and filmmakers, music and print publishers, et cetera. It is just as easy

to see arguments against globalization as thinly veiled special pleading for

national (read “non US”) producers of the same goods. However, “culture wars”

in the US make clear just how strong are claims about the link between culture

and identity (Huntington, 2005). Especially in moments of economic

uncertainty, “culture” and identity become strong instruments indeed in the

political arena. The politics of culture will always be difficult and unpredictable

precisely because they are not anchored in material interests but elicit strong

responses at the ballot box.

Food safety regulation does not turn on quite such strongly intangible concerns,

but still produces very different responses. Food safety is, of course, a shared

value between citizens and governments of both the EU and the US, and yet the

approaches are fundamentally different. The problem is that many technologies

have uncertain future effects and, if the effects are at least plausibly sufficiently

large, it is necessary to weigh the gains from admitting such goods into the food

system against (possibly low probability) costs. US law emphasizes immediate

scientific process. If chlorine washed chicken and genetically modified

organisms cannot be shown to be dangerous with a high degree of certainty,

there is a presumption that they should be permitted to enter the market. The

European approach emphasizes instead the precautionary principle—i.e. to the

extent that we might reasonably suppose that they constitute risks to the food

system, proponents of sales of chlorine washed chicken or GMOs must prove that

they are safe with a high degree of certainty. These are both reasonable, but

debatable, principles for evaluating uncertain prospects (Gollier et al., 2000,

important that we recognize them where they may provide cause for us to be careful in our

policy recommendations.

9

are fundamental differences between parties engaged in the T-TIP negotiations.

Culture is inherently difficult to identify, but it goes to the heart of national

identity. US firms currently dominate the global cultural marketplace. It is easy

to see arguments for globalization as thinly veiled special pleading for US

television and filmmakers, music and print publishers, et cetera. It is just as easy

to see arguments against globalization as thinly veiled special pleading for

national (read “non US”) producers of the same goods. However, “culture wars”

in the US make clear just how strong are claims about the link between culture

and identity (Huntington, 2005). Especially in moments of economic

uncertainty, “culture” and identity become strong instruments indeed in the

political arena. The politics of culture will always be difficult and unpredictable

precisely because they are not anchored in material interests but elicit strong

responses at the ballot box.

Food safety regulation does not turn on quite such strongly intangible concerns,

but still produces very different responses. Food safety is, of course, a shared

value between citizens and governments of both the EU and the US, and yet the

approaches are fundamentally different. The problem is that many technologies

have uncertain future effects and, if the effects are at least plausibly sufficiently

large, it is necessary to weigh the gains from admitting such goods into the food

system against (possibly low probability) costs. US law emphasizes immediate

scientific process. If chlorine washed chicken and genetically modified

organisms cannot be shown to be dangerous with a high degree of certainty,

there is a presumption that they should be permitted to enter the market. The

European approach emphasizes instead the precautionary principle—i.e. to the

extent that we might reasonably suppose that they constitute risks to the food

system, proponents of sales of chlorine washed chicken or GMOs must prove that

they are safe with a high degree of certainty. These are both reasonable, but

debatable, principles for evaluating uncertain prospects (Gollier et al., 2000,

important that we recognize them where they may provide cause for us to be careful in our

policy recommendations.

9

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Sunstein, 2005). The statement that “both countries agree on the goal of food

safety” only goes so far in resolving a fundamental legal difference about how to

evaluate policies in pursuit of that goal. In addition, of course, parties facing

redistributive effects from any harmonization can use legitimate differences

between weighting of type-1 and type-2 error as tools in rent seeking.

Finally, it is widely understood, especially in the aftermath of the 2007-2008

global economic crisis and follow on currency and debt crises that optimal

regulation of the financial sector involves a trade-off of the gains from efficiency

against the (potentially catastrophic, if low probability) losses from financial

crisis. The appropriate policy is affected not only by aggregate attitudes toward

risk, but also by uncertainty about both sources of and appropriate responses to

instability. Of particular relevance to T-TIP, the US has recently become more

aggressive in response to financial risk. This leads to concerns about both what

the appropriate policy is and active use of negotiations (especially by US

financial institutions) to undermine domestic regulation (Johnson and Schott,

2013).

In all three of these cases, as well as many others (some of which are discussed

elsewhere in this paper), these considerations make welfare evaluation difficult.

It is generally the case that, in all three cases, harmonization that results in

increased trade has a first-order welfare improving effect for all the usual

reasons. Nonetheless, because these policies involve substantial uncertainties

and externalities, those effects cannot be the whole story, especially from an

expected welfare point of view. At the same time, precisely because of

uncertainties about both technical details and true preferences, it is not at all

clear how to incorporate such considerations in our analysis. We follow the

keyless drunk in being systematic about those things that permit systematic

evaluation and we remind the reader that this is only part of the story.8 We

console ourselves that both the EU and the US possess robust democratic

8 For more on this, see (Freedman, 2010), who notes “It is often extremely difficult or even

impossible to cleanly measure what is really important, so scientists instead cleanly measure

what they can, hoping it turns out to be relevant.”

10

safety” only goes so far in resolving a fundamental legal difference about how to

evaluate policies in pursuit of that goal. In addition, of course, parties facing

redistributive effects from any harmonization can use legitimate differences

between weighting of type-1 and type-2 error as tools in rent seeking.

Finally, it is widely understood, especially in the aftermath of the 2007-2008

global economic crisis and follow on currency and debt crises that optimal

regulation of the financial sector involves a trade-off of the gains from efficiency

against the (potentially catastrophic, if low probability) losses from financial

crisis. The appropriate policy is affected not only by aggregate attitudes toward

risk, but also by uncertainty about both sources of and appropriate responses to

instability. Of particular relevance to T-TIP, the US has recently become more

aggressive in response to financial risk. This leads to concerns about both what

the appropriate policy is and active use of negotiations (especially by US

financial institutions) to undermine domestic regulation (Johnson and Schott,

2013).

In all three of these cases, as well as many others (some of which are discussed

elsewhere in this paper), these considerations make welfare evaluation difficult.

It is generally the case that, in all three cases, harmonization that results in

increased trade has a first-order welfare improving effect for all the usual

reasons. Nonetheless, because these policies involve substantial uncertainties

and externalities, those effects cannot be the whole story, especially from an

expected welfare point of view. At the same time, precisely because of

uncertainties about both technical details and true preferences, it is not at all

clear how to incorporate such considerations in our analysis. We follow the

keyless drunk in being systematic about those things that permit systematic

evaluation and we remind the reader that this is only part of the story.8 We

console ourselves that both the EU and the US possess robust democratic

8 For more on this, see (Freedman, 2010), who notes “It is often extremely difficult or even

impossible to cleanly measure what is really important, so scientists instead cleanly measure

what they can, hoping it turns out to be relevant.”

10

political systems whose purpose, among other things is to make determinations

about difficult social trade-offs.

3. Quantifying scope for trade cost reductions in T-TIP

We turn next to quantifying possible trade cost reductions under T-TIP. For

tariffs this is relatively straightforward. For NTBs, on the other hand, it is less so.

Therefore, we start with the easier task of describing tariffs. We then move on to

estimates of trade cost reductions for goods in past RTAs, and estimates specific

to the EU-US context. We save the most speculative for last – trade cost

reductions for services.

a. Tariffs

Though both US and EU average tariffs are similar, there is heterogeneity when

we break down tariff protection by sector. From Figure 3-1, the most striking

cases are motor vehicles and processed foods. The EU tariffs on these products

are substantially higher than corresponding US tariffs, and indeed far higher

than the trade-weighted average MFN tariff for goods overall. For motor

vehicles9 the EU applies an average tariff (7.9 per cent) that is over seven times

higher than the US. For processed food products, EU average tariffs (15.8 per

cent) are more than three times higher than US average tariffs. Though primary

agriculture appears relatively open, this is misleading. Protection in this sector

takes the form of a wife variety of NTBs, as will be see in the next subsection.

b. NTB liberalization in FTAs

We now turn to the trickier question of possible trade cost reductions linked to

NTBs. As noted above, such cost savings may follow from cross-recognition of

standards (a process where industry plays a central role) to acceptance of

9 Motor vehicles sector in this case includes also parts and components.

11

about difficult social trade-offs.

3. Quantifying scope for trade cost reductions in T-TIP

We turn next to quantifying possible trade cost reductions under T-TIP. For

tariffs this is relatively straightforward. For NTBs, on the other hand, it is less so.

Therefore, we start with the easier task of describing tariffs. We then move on to

estimates of trade cost reductions for goods in past RTAs, and estimates specific

to the EU-US context. We save the most speculative for last – trade cost

reductions for services.

a. Tariffs

Though both US and EU average tariffs are similar, there is heterogeneity when

we break down tariff protection by sector. From Figure 3-1, the most striking

cases are motor vehicles and processed foods. The EU tariffs on these products

are substantially higher than corresponding US tariffs, and indeed far higher

than the trade-weighted average MFN tariff for goods overall. For motor

vehicles9 the EU applies an average tariff (7.9 per cent) that is over seven times

higher than the US. For processed food products, EU average tariffs (15.8 per

cent) are more than three times higher than US average tariffs. Though primary

agriculture appears relatively open, this is misleading. Protection in this sector

takes the form of a wife variety of NTBs, as will be see in the next subsection.

b. NTB liberalization in FTAs

We now turn to the trickier question of possible trade cost reductions linked to

NTBs. As noted above, such cost savings may follow from cross-recognition of

standards (a process where industry plays a central role) to acceptance of

9 Motor vehicles sector in this case includes also parts and components.

11

regulations (a process where regulators need to find common ground and

essentially trust the approach taken by comparable agencies on the opposite side

of the pond) to even joint regulation and development of joint standards. None

of this can be considered as easy. While examples such as “run drug trials once

and not twice” might seem obvious places to start, as noted in Section 2,

differences in social/political approach to risk and consumer protection render

even the obvious into something more complex and murky. 10

Figure 3-1 Applied (MFN) tariffs on trans-Atlantic trade

Source: WTO integrated database and the World Bank/UNCTAD WITS database.

Values reported are for 2011 and are trade-weighted.

One place to look, in terms of estimating possible reductions in trade costs, is the

impact we observe from past trade agreements. The EU itself, for example, has

been engaged in a decades long exercise not unlike the goals stated for the T-TIP.

We have also seen other trade agreements, ranging from shallow tariff-only FTAs

to relatively deep and comprehensive agreements, like the NAFTA. These may

10 We invite the reader to look through firm survey responses to regulation in the ECORYS (2009)

annex material, “Annex VI Business survey results”, which provides examples on an industry

basis of sources of cost differences when the same firms operate in multiple regulatory regimes.

12

essentially trust the approach taken by comparable agencies on the opposite side

of the pond) to even joint regulation and development of joint standards. None

of this can be considered as easy. While examples such as “run drug trials once

and not twice” might seem obvious places to start, as noted in Section 2,

differences in social/political approach to risk and consumer protection render

even the obvious into something more complex and murky. 10

Figure 3-1 Applied (MFN) tariffs on trans-Atlantic trade

Source: WTO integrated database and the World Bank/UNCTAD WITS database.

Values reported are for 2011 and are trade-weighted.

One place to look, in terms of estimating possible reductions in trade costs, is the

impact we observe from past trade agreements. The EU itself, for example, has

been engaged in a decades long exercise not unlike the goals stated for the T-TIP.

We have also seen other trade agreements, ranging from shallow tariff-only FTAs

to relatively deep and comprehensive agreements, like the NAFTA. These may

10 We invite the reader to look through firm survey responses to regulation in the ECORYS (2009)

annex material, “Annex VI Business survey results”, which provides examples on an industry

basis of sources of cost differences when the same firms operate in multiple regulatory regimes.

12

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

provide some guidance on the magnitude of trade cost reductions that we might

expect, if T-TIP ends of looking like the deeper end of existing agreements.

In formal terms, we have implemented a gravity model of trade, estimated in a

cross-section of data for the year 2010 for goods at the level of aggregation used

for our computational model, and comparable to earlier ECORYS (2009)

aggregates.11 This means we specify bilateral trade flows in levels as an

exponential function of a log-linear index that is composed of three classes of

determinants: exporter-specific factors (measuring supply potential of exporting

countries), importer-specific factors (measuring demand potential of importing

countries), and bilateral factors (measuring trade impediments in a broad

sense). We specify exporter-specific and importer-specific factors as country

fixed effects and parameterize bilateral factors in the log-linear index as a

function of observable country-pair-specific variables. Thereby, we ensure that

the parameters on the later exhibit a structural interpretation that permits using

them in a subsequent comparative static analysis of a model that is calibrated to

data on trade and production at the same level of aggregation, where the trade

equations in the model are consistent with those in the gravity model itself.

A more technical discussion of the econometrics is provided in the annex.

For explanatory variables we include log bilateral distance, common border,

common language, and former colonial ties. We also include a measure of

political distance based on measures from the political science literature

(polity).12 We have also included the bilateral tariff margin granted in free trade

agreements (measured as the difference between the most-favoured nation rate,

which is subsumed under the importer-specific fixed effect, and the rate used in

11 A mapping from these sectors for NACE is provided in the annex. We have used 2010 rather

than 2011 because bilateral trade and tariff data, while available for the US and EU, were not

available yet for a broad enough set of countries, and we made the decision to go with 2010 to

gain dimensionality in the data used for the regression-based analysis.

12 Shipping distances are based on actual shipping routes (Francois and Rojas-Romagosa, 2014),

data on FTA rankings are from Dür et al. (2014), other geopolitical distance measures are from

the CEPII database (Mayer and Zignago, 2011), and polity comes from the Quality of Governance

(QoG) expert survey dataset (Teorell et al., 2011). The political economy variables include

pairwise measures of similarity, reflecting evidence that homophily is important in explaining

direct economic and political linkages (De Benedictis and Tajoli, 2011).

13

expect, if T-TIP ends of looking like the deeper end of existing agreements.

In formal terms, we have implemented a gravity model of trade, estimated in a

cross-section of data for the year 2010 for goods at the level of aggregation used

for our computational model, and comparable to earlier ECORYS (2009)

aggregates.11 This means we specify bilateral trade flows in levels as an

exponential function of a log-linear index that is composed of three classes of

determinants: exporter-specific factors (measuring supply potential of exporting

countries), importer-specific factors (measuring demand potential of importing

countries), and bilateral factors (measuring trade impediments in a broad

sense). We specify exporter-specific and importer-specific factors as country

fixed effects and parameterize bilateral factors in the log-linear index as a

function of observable country-pair-specific variables. Thereby, we ensure that

the parameters on the later exhibit a structural interpretation that permits using

them in a subsequent comparative static analysis of a model that is calibrated to

data on trade and production at the same level of aggregation, where the trade

equations in the model are consistent with those in the gravity model itself.

A more technical discussion of the econometrics is provided in the annex.

For explanatory variables we include log bilateral distance, common border,

common language, and former colonial ties. We also include a measure of

political distance based on measures from the political science literature

(polity).12 We have also included the bilateral tariff margin granted in free trade

agreements (measured as the difference between the most-favoured nation rate,

which is subsumed under the importer-specific fixed effect, and the rate used in

11 A mapping from these sectors for NACE is provided in the annex. We have used 2010 rather

than 2011 because bilateral trade and tariff data, while available for the US and EU, were not

available yet for a broad enough set of countries, and we made the decision to go with 2010 to

gain dimensionality in the data used for the regression-based analysis.

12 Shipping distances are based on actual shipping routes (Francois and Rojas-Romagosa, 2014),

data on FTA rankings are from Dür et al. (2014), other geopolitical distance measures are from

the CEPII database (Mayer and Zignago, 2011), and polity comes from the Quality of Governance

(QoG) expert survey dataset (Teorell et al., 2011). The political economy variables include

pairwise measures of similarity, reflecting evidence that homophily is important in explaining

direct economic and political linkages (De Benedictis and Tajoli, 2011).

13

a respective trade agreement. (This actually represents the negative of the

preference margin.) Most important, in the present context, is that we have a

measure of the depth of various FTAs from Dür, Elsig and Milewicz (2014). The

depth-of-trade agreement variable takes on integer values ranging between

unity for shallow agreements and seven for deep agreements. The EU is not

technically an FTA, and we represent this with an additional dummy variable.

This indicator variable for intra-European-Union relationships differentiates

between the legal and institutional harmonization associated with EU

membership, which clearly goes beyond the liberalization of policies in other

agreements. 13

Table 3-1 summarizes the relevant trade-cost-function parameters of the second-

stage regression. (The parameters of the first-stage ordered-probit model are

summarized in the Appendix.) Across all regressions presented in the table, the

explanatory power – measured by the correlation coefficient between the model

and the data, dubbed as pseudo-R2 – is quite high. The results suggest that

overall as well as at sector-level, goods trade (in most sectors) rises (trade costs

decline) with a larger preference margin granted in trade agreements, with a

greater depth of an agreement, and with EU membership. The parameter on the

(negative) tariff margin reflects what is referred to as the elasticity of trade with

respect to tariffs.14 With reference to the new trade literature on monopolistic

competition and economies of scale, we

13 We treat the trade policy variables as jointly endogenous and pursue a control-function

approach to reduce the parameter bias flowing from that endogeneity. In essence we have

expanded on the methodology of Egger et al. (2011) to encompass different types of trade

agreements. This approach is discussed in detail in the Appendix. From a general perspective,

such an approach relies on some instrumental variables which help splitting the variation in an

endogenous variable – e.g., the integer-valued depth-of-agreement measure – into two

components: one that contains exogenous variation only and one that contains also endogenous

variation. In the present analysis, we assume joint normality of the endogenous variables and we

base the control function on generalized Mills’ ratios that are obtained from an ordered probit

model of depth-of-trade agreements. Since intra-EU relationships are associated with a depth

measure of seven, and tariff margins granted in agreements are correlated with the depth of

agreements, a flexible function of depth-integer-specific Mills’ ratios is capable of controlling for

the endogeneity of all trade policy measured included in the analysis.

14 This is often estimated at being between -3.5 and -7 for aggregate trade flows and varies

largely across sectors. See for example Broda and Weinstein (2006).

14

preference margin.) Most important, in the present context, is that we have a

measure of the depth of various FTAs from Dür, Elsig and Milewicz (2014). The

depth-of-trade agreement variable takes on integer values ranging between

unity for shallow agreements and seven for deep agreements. The EU is not

technically an FTA, and we represent this with an additional dummy variable.

This indicator variable for intra-European-Union relationships differentiates

between the legal and institutional harmonization associated with EU

membership, which clearly goes beyond the liberalization of policies in other

agreements. 13

Table 3-1 summarizes the relevant trade-cost-function parameters of the second-

stage regression. (The parameters of the first-stage ordered-probit model are

summarized in the Appendix.) Across all regressions presented in the table, the

explanatory power – measured by the correlation coefficient between the model

and the data, dubbed as pseudo-R2 – is quite high. The results suggest that

overall as well as at sector-level, goods trade (in most sectors) rises (trade costs

decline) with a larger preference margin granted in trade agreements, with a

greater depth of an agreement, and with EU membership. The parameter on the

(negative) tariff margin reflects what is referred to as the elasticity of trade with

respect to tariffs.14 With reference to the new trade literature on monopolistic

competition and economies of scale, we

13 We treat the trade policy variables as jointly endogenous and pursue a control-function

approach to reduce the parameter bias flowing from that endogeneity. In essence we have

expanded on the methodology of Egger et al. (2011) to encompass different types of trade

agreements. This approach is discussed in detail in the Appendix. From a general perspective,

such an approach relies on some instrumental variables which help splitting the variation in an

endogenous variable – e.g., the integer-valued depth-of-agreement measure – into two

components: one that contains exogenous variation only and one that contains also endogenous

variation. In the present analysis, we assume joint normality of the endogenous variables and we

base the control function on generalized Mills’ ratios that are obtained from an ordered probit

model of depth-of-trade agreements. Since intra-EU relationships are associated with a depth

measure of seven, and tariff margins granted in agreements are correlated with the depth of

agreements, a flexible function of depth-integer-specific Mills’ ratios is capable of controlling for

the endogeneity of all trade policy measured included in the analysis.

14 This is often estimated at being between -3.5 and -7 for aggregate trade flows and varies

largely across sectors. See for example Broda and Weinstein (2006).

14

Table 3-1 PPML-based gravity estimates for goods

All Goods

Primary

agriculture

Primary

energy

Processed

foods

tariff -6.564 *** -1.960 *** -26.395 *** -2.914 ***

distance -0.529 *** -0.629 *** -0.896 *** -0.596 ***

common colony 0.439 *** 0.542 *** -0.079 0.477 *

common language 0.203 ** 0.239 ** 0.646 ** 0.370 ***

common border 0.508 *** 0.630 *** 0.597 ** 0.664 ***

polity -143.627 *** -30.255 *** -52.614 50.248

former colony 0.229 ** 0.228 ** 0.621 ** 0.406 ***

FTA depth 0.055 ** 0.164 ** 0.164 ** 0.082 ***

EUN 0.451 *** 1.087 *** 1.574 *** 0.681 ***

observations 11,145 11,053 9,413 11,109

pseudo R2 0.8828 0.8306 0.6918 0.8806

Beverages

and

tobacco

Chemicals

and

pharmaceuticals

Petro-

chemicals

Metals,

fabricated

metals

tariff -4.013 *** -3.188 ** -9.032 *** -5.304 ***

distance -0.603 *** -0.627 *** -0.755 *** -0.728 ***

common colony 1.255 *** 0.031 -0.251 0.223

common language 0.462 *** 0.151 * 0.213 0.036

common border 0.509 *** 0.370 *** 0.494 *** 0.587 ***

polity 167.547 * 45.513 * 46.158 -52.582 *

former colony 0.794 *** 0.378 *** 0.014 0.231 **

FTA depth 0.180 *** 0.021 0.192 *** 0.007

EUN 0.462 § 0.160 -0.118 0.778 ***

observations 11,087 11,123 10,854 11,065

pseudo R2 0.8219 0.9517 0.643 0.757

Motor

vehicles

Electronic

equipment

Other

machinery

Other

manufacturing

tariff -12.166 *** -22.869 *** -13.307 *** -7.653 ***

distance -0.312 *** -0.364 *** -0.473 *** -0.526 ***

common colony 0.657 * 0.499 ** 0.460 ** 0.416 ***

common language 0.151 0.130 0.288 ** 0.196 **

common border 0.467 *** 0.357 ** 0.353 *** 0.471 ***

polity 41.944 *** -241.980 *** -168.209 *** -115.083 ***

former colony -0.289 ** 0.128 0.331 *** 0.241 **

FTA depth 0.151 *** 0.028 0.057 *** 0.050 **

EUN 0.884 *** 1.141 *** 0.116 0.386 ***

observations 11,098 11,094 11,115 10,292

pseudo R2 0.8982 0.9372 0.9151 0.899

15

All Goods

Primary

agriculture

Primary

energy

Processed

foods

tariff -6.564 *** -1.960 *** -26.395 *** -2.914 ***

distance -0.529 *** -0.629 *** -0.896 *** -0.596 ***

common colony 0.439 *** 0.542 *** -0.079 0.477 *

common language 0.203 ** 0.239 ** 0.646 ** 0.370 ***

common border 0.508 *** 0.630 *** 0.597 ** 0.664 ***

polity -143.627 *** -30.255 *** -52.614 50.248

former colony 0.229 ** 0.228 ** 0.621 ** 0.406 ***

FTA depth 0.055 ** 0.164 ** 0.164 ** 0.082 ***

EUN 0.451 *** 1.087 *** 1.574 *** 0.681 ***

observations 11,145 11,053 9,413 11,109

pseudo R2 0.8828 0.8306 0.6918 0.8806

Beverages

and

tobacco

Chemicals

and

pharmaceuticals

Petro-

chemicals

Metals,

fabricated

metals

tariff -4.013 *** -3.188 ** -9.032 *** -5.304 ***

distance -0.603 *** -0.627 *** -0.755 *** -0.728 ***

common colony 1.255 *** 0.031 -0.251 0.223

common language 0.462 *** 0.151 * 0.213 0.036

common border 0.509 *** 0.370 *** 0.494 *** 0.587 ***

polity 167.547 * 45.513 * 46.158 -52.582 *

former colony 0.794 *** 0.378 *** 0.014 0.231 **

FTA depth 0.180 *** 0.021 0.192 *** 0.007

EUN 0.462 § 0.160 -0.118 0.778 ***

observations 11,087 11,123 10,854 11,065

pseudo R2 0.8219 0.9517 0.643 0.757

Motor

vehicles

Electronic

equipment

Other

machinery

Other

manufacturing

tariff -12.166 *** -22.869 *** -13.307 *** -7.653 ***

distance -0.312 *** -0.364 *** -0.473 *** -0.526 ***

common colony 0.657 * 0.499 ** 0.460 ** 0.416 ***

common language 0.151 0.130 0.288 ** 0.196 **

common border 0.467 *** 0.357 ** 0.353 *** 0.471 ***

polity 41.944 *** -241.980 *** -168.209 *** -115.083 ***

former colony -0.289 ** 0.128 0.331 *** 0.241 **

FTA depth 0.151 *** 0.028 0.057 *** 0.050 **

EUN 0.884 *** 1.141 *** 0.116 0.386 ***

observations 11,098 11,094 11,115 10,292

pseudo R2 0.8982 0.9372 0.9151 0.899

15

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

note: Cross section regressions based on 2010 data from COMTRADE, WITS, DESTA, CEPII as

discussed in text. Regressions are PPML based and include source and destination fixed effects and

correction for PTA endogeneity.

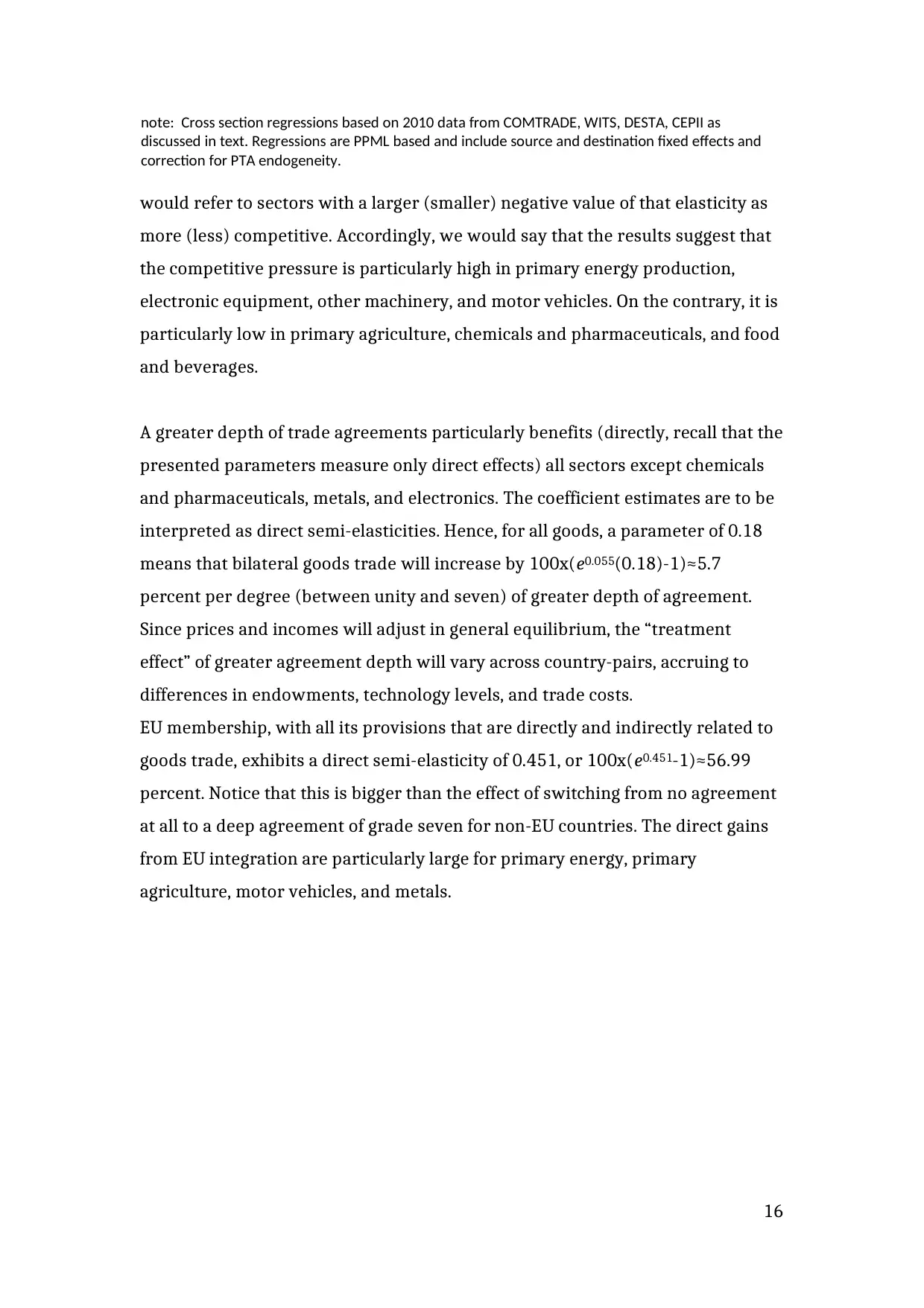

would refer to sectors with a larger (smaller) negative value of that elasticity as

more (less) competitive. Accordingly, we would say that the results suggest that

the competitive pressure is particularly high in primary energy production,

electronic equipment, other machinery, and motor vehicles. On the contrary, it is

particularly low in primary agriculture, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, and food

and beverages.

A greater depth of trade agreements particularly benefits (directly, recall that the

presented parameters measure only direct effects) all sectors except chemicals

and pharmaceuticals, metals, and electronics. The coefficient estimates are to be

interpreted as direct semi-elasticities. Hence, for all goods, a parameter of 0.18

means that bilateral goods trade will increase by 100x(e0.055(0.18)-1)≈5.7

percent per degree (between unity and seven) of greater depth of agreement.

Since prices and incomes will adjust in general equilibrium, the “treatment

effect” of greater agreement depth will vary across country-pairs, accruing to

differences in endowments, technology levels, and trade costs.

EU membership, with all its provisions that are directly and indirectly related to

goods trade, exhibits a direct semi-elasticity of 0.451, or 100x(e0.451-1)≈56.99

percent. Notice that this is bigger than the effect of switching from no agreement

at all to a deep agreement of grade seven for non-EU countries. The direct gains

from EU integration are particularly large for primary energy, primary

agriculture, motor vehicles, and metals.

16

discussed in text. Regressions are PPML based and include source and destination fixed effects and

correction for PTA endogeneity.

would refer to sectors with a larger (smaller) negative value of that elasticity as

more (less) competitive. Accordingly, we would say that the results suggest that

the competitive pressure is particularly high in primary energy production,

electronic equipment, other machinery, and motor vehicles. On the contrary, it is

particularly low in primary agriculture, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, and food

and beverages.

A greater depth of trade agreements particularly benefits (directly, recall that the

presented parameters measure only direct effects) all sectors except chemicals

and pharmaceuticals, metals, and electronics. The coefficient estimates are to be

interpreted as direct semi-elasticities. Hence, for all goods, a parameter of 0.18

means that bilateral goods trade will increase by 100x(e0.055(0.18)-1)≈5.7

percent per degree (between unity and seven) of greater depth of agreement.

Since prices and incomes will adjust in general equilibrium, the “treatment

effect” of greater agreement depth will vary across country-pairs, accruing to

differences in endowments, technology levels, and trade costs.

EU membership, with all its provisions that are directly and indirectly related to

goods trade, exhibits a direct semi-elasticity of 0.451, or 100x(e0.451-1)≈56.99

percent. Notice that this is bigger than the effect of switching from no agreement

at all to a deep agreement of grade seven for non-EU countries. The direct gains

from EU integration are particularly large for primary energy, primary

agriculture, motor vehicles, and metals.

16

Table 3-2 Trade cost reduction estimates, AVEs for goods

A B C D E

intra-EU

AVE savings

deep RTA

AVE savings

ECORYS

(2009)

EU vs US

ECORYS

(2009)

US vs EU

Share of

bilateral

trade

GOODS 7.1 6.0 na na 70.6

Primary agriculture 74.1 79.8 na na 0.9

Primary energy 6.1 36.9 na na 0.6

Processed foods 26.3 21.8 25.4 25.4 1.4

Beverages and tobacco 12.2 36.9 25.4 25.4 1.6

Petrochemicals 0.0 16.0 na na 3.3

Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals 0.0 0.0 10.2 11.4 19.3

Metals, fabricated metals 15.8 0.0 5.3 9.0 5.1

Motor vehicles 7.5 9.1 14.0 14.2 5.9

Electrical machinery 5.1 0.0 6.0 6.8 3.1

Other machinery 0.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 23.2

Other manufactures 5.2 4.6 na na 6.2

Table 3-2 summarizes the ad-valorem equivalents (AVEs) of non-tariff trade-cost

factors in columns A and B. These are based on the regression coefficients in

Table 3-1. To see what these AVEs are, let the generic ad-valorem tariff

parameter be a and the coefficient on any non-tariff measure be b. Moreover,

denote the average value of any generic non-tariff trade cost by c. Then, the AVE

≡ 100x(e-bc/a-1) measures the necessary percentage point adjustment of tariffs

which is equivalent to eliminating the respective non-tariff cost. In the table, the

trade cost indicator c is either EU Membership of the depth of a particular

agreement. In essence the term bc is the trade volume effect, and dividing by the

tariff coefficient gives the comparable tariff that would yield the same volume

effect. In Table 3-2 we have computed two tariff-equivalents, one for cost-savings

from EU membership (i.e., the deepest trade agreement in our sample) and one

for estimated cost reductions following from the deepest observed FTAs (so

indexed as 7). The results suggest that the tariff-equivalent effects of intra-EU

preferences are largest for primary agriculture and processed foods, followed by

metals and fabricated metals. We also observe differences in, both positive and

negative, when comparing the EU estimates with deep FTAs. There are good

17

A B C D E

intra-EU

AVE savings

deep RTA

AVE savings

ECORYS

(2009)

EU vs US

ECORYS

(2009)

US vs EU

Share of

bilateral

trade

GOODS 7.1 6.0 na na 70.6

Primary agriculture 74.1 79.8 na na 0.9

Primary energy 6.1 36.9 na na 0.6

Processed foods 26.3 21.8 25.4 25.4 1.4

Beverages and tobacco 12.2 36.9 25.4 25.4 1.6

Petrochemicals 0.0 16.0 na na 3.3

Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals 0.0 0.0 10.2 11.4 19.3

Metals, fabricated metals 15.8 0.0 5.3 9.0 5.1

Motor vehicles 7.5 9.1 14.0 14.2 5.9

Electrical machinery 5.1 0.0 6.0 6.8 3.1

Other machinery 0.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 23.2

Other manufactures 5.2 4.6 na na 6.2

Table 3-2 summarizes the ad-valorem equivalents (AVEs) of non-tariff trade-cost

factors in columns A and B. These are based on the regression coefficients in

Table 3-1. To see what these AVEs are, let the generic ad-valorem tariff

parameter be a and the coefficient on any non-tariff measure be b. Moreover,

denote the average value of any generic non-tariff trade cost by c. Then, the AVE

≡ 100x(e-bc/a-1) measures the necessary percentage point adjustment of tariffs

which is equivalent to eliminating the respective non-tariff cost. In the table, the

trade cost indicator c is either EU Membership of the depth of a particular

agreement. In essence the term bc is the trade volume effect, and dividing by the

tariff coefficient gives the comparable tariff that would yield the same volume

effect. In Table 3-2 we have computed two tariff-equivalents, one for cost-savings

from EU membership (i.e., the deepest trade agreement in our sample) and one

for estimated cost reductions following from the deepest observed FTAs (so