Analysis of Charles Tyrwhitt's Business Model using BMC - MGMT20143

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/09

|14

|14486

|59

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study deconstructs Charles Tyrwhitt's business model using the Business Model Canvas framework. It identifies key features contributing to its impact on Australian fashion retail, drawing from publicly available information. The analysis highlights the company's reliance on direct mail order elements and rented mailing lists for online order capture. Challenges include growing inventory holdings, a slowing inventory cycle, new store openings in low-growth markets, and significant owner capital drawings. The report suggests reshaping the business model by shifting to a 'job to be done' customer segmentation, assessing disruptive innovation threats, and focusing on successful market strategies in Scandinavia and other English-speaking regions. Recommendations aim to address current issues and drive future growth for Charles Tyrwhitt.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304026101

The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable

business models

Article in Journal of Cleaner Production · June 2016

DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

CITATIONS

66

READS

5,077

2 authors:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Hamburg Workshops on Sustainability-Oriented Business ModelsView project

Business Model Patterns to Support Sustainable BusinessView project

Alexandre Joyce

Concordia University Montreal

10 PUBLICATIONS 88 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Raymond L. Paquin

Concordia University Montreal

19 PUBLICATIONS 438 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable

business models

Article in Journal of Cleaner Production · June 2016

DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

CITATIONS

66

READS

5,077

2 authors:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Hamburg Workshops on Sustainability-Oriented Business ModelsView project

Business Model Patterns to Support Sustainable BusinessView project

Alexandre Joyce

Concordia University Montreal

10 PUBLICATIONS 88 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Raymond L. Paquin

Concordia University Montreal

19 PUBLICATIONS 438 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more

sustainable business models

Alexandre Joycea, *

, Raymond L.Paquin b

a Institut de developpement de produits,4805 Molson,Montreal,Quebec H1Y0A2 Canada

b Concordia University,John Molson School of Business,MB 13.125 e Dept.of Management, 1455 De Maisonneuve Blvd.W.,Montreal,Quebec H3G 1M8

Canada

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 5 August 2015

Received in revised form

30 May 2016

Accepted 11 June 2016

Available online xxx

Keywords:

Business model innovation

Sustainable business models

Business models for sustainability

Triple layered business model canvas

Triple bottom line

a b s t r a c t

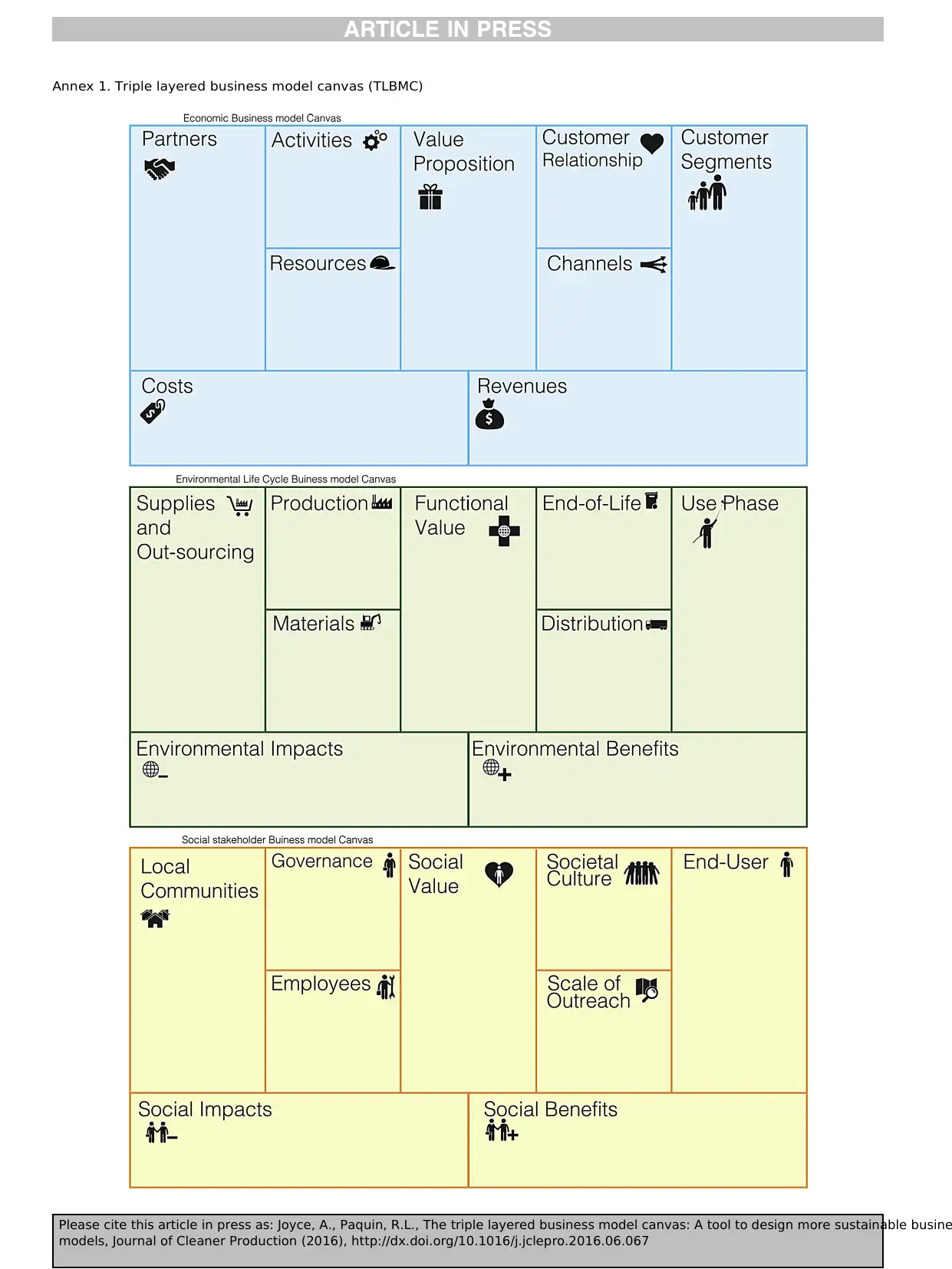

The Triple Layered Business Model Canvas is a tool for exploring sustainability-oriented business model

innovation.It extends the original business model canvas by adding two layers: an environmental layer

based on a lifecycle perspective and a sociallayer based on a stakeholder perspective.When taken

together,the three layers of the business modelmake more explicit how an organization generates

multiple types of value e economic,environmental and social.Visually representing a business model

through this canvas tool supports developing and communicating a more holistic and integrated view of

a business model; which also supports creatively innovating towards more sustainable business models.

This paper presents the triple layer business model canvas tool and describes its key features through a

re-analysis of the Nestle Nespresso business model.This new tool contributes to sustainable business

model research by providing a design toolwhich structures sustainability issues in business model

innovation. Also, it creates two new dynamics for analysis: horizontal coherence and vertical coherence.

© 2016 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The pressure for businesses to respond to sustainability con-

cerns is increasing.Organizations are expected to more actively

address issues such as financialcrises,economic and socialin-

equalities, environmental events, material resource scarcity, energy

demands and technological development as part of their focus. On

the one hand,those challenges can be seen as an increase in risk

(Tennberg, 1995; Paterson,2001).On the other,those same chal-

lenges can be seen as opportunities for organizations to engage in

sustainability-oriented innovation (Adams et al., 2015; Hart, 2005;

McDonough and Braungart,2002). For organizations to succeed,

they must respond to such challenges by creatively integrating eco-

efficient and eco-effective innovations which help conserve and

improve natural, social and financial resourcesinto their core

business (Castello and Lozano,2011; Rifkin,2014; Jackson,2009).

Yet for sustainability-oriented innovation to be truly impactful,it

needs to move beyond incremental,compartmentalized changes

within an organization and towards integrated and integral

changes which reach across the organization and beyond itits

larger stakeholder environment(Adams et al., 2015; Nidumolu

et al.,2009).

For the past 25 years,businesses have been looking at sustain-

ability issues from a far (Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002) without

meaningfully reducing their aggregate resource and energy use.

Most organizationalapproaches have failed to create necessary

reductions in impact at least, in part, because business thinking has

failed to integrate a more natural sciences-based awareness of

sustainability and the ecological limits to our planetary boundaries

(Pain, 2014; Rockstr€om et al.,2009; Whiteman et al., 2013).

This article proposes the Triple Layer Business ModelCanvas

(TLBMC) as a practicaltool for coherently integrating economic,

environmental,and socialconcerns into a holistic view of an or-

ganization's business model. The TLBMC builds on Osterwalder and

Pigneur (2010) originalbusiness modelcanvas e a popular and

widely adopted tool for supporting business model innovation e by

explicitly integrating environmentaland social impacts through

additional business model layers that align directly with the orig-

inal economic-oriented canvas. The TLBMC is a practical and easy to

use tool which supports creatively developing,visualizing,and

communicating sustainable business model innovation (Stubbs and

Cocklin, 2008). The TLBMC follows a triple-bottom line approach to

* Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses:alexandre.joyce@idp-ipd.com (A.Joyce), Raymond.paquin@

concordia.ca (R.L.Paquin).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Cleaner Production

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / j c l e p r o

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

0959-6526/© 2016 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e13

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busi

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

sustainable business models

Alexandre Joycea, *

, Raymond L.Paquin b

a Institut de developpement de produits,4805 Molson,Montreal,Quebec H1Y0A2 Canada

b Concordia University,John Molson School of Business,MB 13.125 e Dept.of Management, 1455 De Maisonneuve Blvd.W.,Montreal,Quebec H3G 1M8

Canada

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 5 August 2015

Received in revised form

30 May 2016

Accepted 11 June 2016

Available online xxx

Keywords:

Business model innovation

Sustainable business models

Business models for sustainability

Triple layered business model canvas

Triple bottom line

a b s t r a c t

The Triple Layered Business Model Canvas is a tool for exploring sustainability-oriented business model

innovation.It extends the original business model canvas by adding two layers: an environmental layer

based on a lifecycle perspective and a sociallayer based on a stakeholder perspective.When taken

together,the three layers of the business modelmake more explicit how an organization generates

multiple types of value e economic,environmental and social.Visually representing a business model

through this canvas tool supports developing and communicating a more holistic and integrated view of

a business model; which also supports creatively innovating towards more sustainable business models.

This paper presents the triple layer business model canvas tool and describes its key features through a

re-analysis of the Nestle Nespresso business model.This new tool contributes to sustainable business

model research by providing a design toolwhich structures sustainability issues in business model

innovation. Also, it creates two new dynamics for analysis: horizontal coherence and vertical coherence.

© 2016 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The pressure for businesses to respond to sustainability con-

cerns is increasing.Organizations are expected to more actively

address issues such as financialcrises,economic and socialin-

equalities, environmental events, material resource scarcity, energy

demands and technological development as part of their focus. On

the one hand,those challenges can be seen as an increase in risk

(Tennberg, 1995; Paterson,2001).On the other,those same chal-

lenges can be seen as opportunities for organizations to engage in

sustainability-oriented innovation (Adams et al., 2015; Hart, 2005;

McDonough and Braungart,2002). For organizations to succeed,

they must respond to such challenges by creatively integrating eco-

efficient and eco-effective innovations which help conserve and

improve natural, social and financial resourcesinto their core

business (Castello and Lozano,2011; Rifkin,2014; Jackson,2009).

Yet for sustainability-oriented innovation to be truly impactful,it

needs to move beyond incremental,compartmentalized changes

within an organization and towards integrated and integral

changes which reach across the organization and beyond itits

larger stakeholder environment(Adams et al., 2015; Nidumolu

et al.,2009).

For the past 25 years,businesses have been looking at sustain-

ability issues from a far (Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002) without

meaningfully reducing their aggregate resource and energy use.

Most organizationalapproaches have failed to create necessary

reductions in impact at least, in part, because business thinking has

failed to integrate a more natural sciences-based awareness of

sustainability and the ecological limits to our planetary boundaries

(Pain, 2014; Rockstr€om et al.,2009; Whiteman et al., 2013).

This article proposes the Triple Layer Business ModelCanvas

(TLBMC) as a practicaltool for coherently integrating economic,

environmental,and socialconcerns into a holistic view of an or-

ganization's business model. The TLBMC builds on Osterwalder and

Pigneur (2010) originalbusiness modelcanvas e a popular and

widely adopted tool for supporting business model innovation e by

explicitly integrating environmentaland social impacts through

additional business model layers that align directly with the orig-

inal economic-oriented canvas. The TLBMC is a practical and easy to

use tool which supports creatively developing,visualizing,and

communicating sustainable business model innovation (Stubbs and

Cocklin, 2008). The TLBMC follows a triple-bottom line approach to

* Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses:alexandre.joyce@idp-ipd.com (A.Joyce), Raymond.paquin@

concordia.ca (R.L.Paquin).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Cleaner Production

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / j c l e p r o

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

0959-6526/© 2016 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e13

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busi

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

organizationalsustainability (Elkington,1994),explicitly address-

ing and integrating economic,environmental,and social value

creation as core to an organization's business model. In particular, it

leverages life-cycle analysisand stakeholder managementper-

spectives within newly created environmental and social canvases

to conceptualize and connectmultiple types of value creation

within a business model perspective.

As a tool,the TLBMC bridges business modelinnovation (Zott

et al., 2011;Spieth et al.,2014) and sustainable business model

development(Boons and Lüdeke-Freund,2013) to support in-

dividuals and organizations in creatively and holistically seeking

competitive sustainability-oriented change as a way to address the

challenges facing us today (Azapagic, 2003; Shrivastava and Statler,

2012). The TLBMC can help users overcome barriers to

sustainability-oriented change within organizations (Lozano, 2013)

by creatively re-conceptualizing their current business models and

communicating potential innovations. Sustainability is argued to be

the key driver of creative innovation for many firms and im-

provements towards sustainability requires innovating on existing

business models to create “new ways of delivering and capturing

value, which will change the basis of competition” (Nidumolu et al.,

2009, p.9). While this point is not new, relatively little work sheds

light on tools which may support the creative conceptual phase of

innovating business models towards organizational sustainability.

Through private consulting, organizational workshops, and

university courses, the TLBMC has been found to help users quickly

visualize and communicate existing business models, make explicit

data and information gaps,and creatively explore potential busi-

ness model innovations which were more explicitly sustainability-

oriented.The TLBMC's layered format helped users better under-

stand and representthe interconnections and relationships be-

tween organizations' current actions and its economic,

environmentaland socialimpacts.By developing environmental

and socialcanvas layers as direct extensions of Osterwalder and

Pigneur (2010) original economic-oriented business model

canvas,each canvas layer provides a horizontal coherence within

itself which also connects across layers, providing a vertical

coherence or more holistic perspective on value creation,which

integrates a view of economic,environmental,and social value

creation throughoutthe business model.Thus, the TLBMC may

enable users to creativity develop broader perspectives and in-

sights into their organizations' actions.

The TLBMC contributes to this specialissue on organizational

creativity and sustainability by proposing a user-friendly toolto

support sustainability-oriented business model innovation. First, as

a multi-layer business model canvas,the TLBMC offers a clear and

relatively easy way to visualize and discuss a business model's

multiple and diverse impacts.Instead of attempting to reduce

multiple types of value into a single canvas,the TLBMC allows

economic,environmentaland social value to be explored hori-

zontally within their own layer and in relationship to each other

through the verticalintegration ofthese layers together.This, in

turn, supports richer discussion and more creative exploration of

sustainability-oriented innovations as a way to explore how action

in one aspect of an organization may ripple through other parts of

the organization.

Second,the TLBMC provides a concise framework to support

visualization, communication and collaboration around innovating

more sustainable businessmodels (Boons and Lüdeke-Freund,

2013).As a relatively easy to understand approach to conceptual-

izing organizations,the TLBMC is as a boundary object (Carlile,

2002) to communicate change to diverse audiences.At its core,

the TLBMC may support transitioning from incrementaland iso-

lated innovations to more integrated and systemic sustainability-

oriented innovations which are likely better suited to meeting

ongoing global crises, and energy and material constraints (Adams

et al.,2015; Shrivastava and Paquin,2011; von Weizsacker et al.,

2009). To support future research and practice around

sustainability-oriented business modelinnovation,the TLBMC is

reproduced in Annex 1 and is available for use under a creative

commons licence.

2. Business models and business model canvases

While the concept of a business model as a“theory of a busi-

ness” is not new (Drucker, 1955), business model research has only

relatively recently gained the attention of many scholars. In fact, as

one recent review noted, scholars “do not [readily] agree on what a

business modelis” (Zott et al., 2011,p.1020).However,for this

article a business model is defined as “the rationale of how an or-

ganization creates,delivers and captures value” (Osterwalder and

Pigneur,2010,p.14).In particular,it is a conceptualization ofan

organization which includes 3 key aspects (Chesbrough,2010;

Osterwalder, 2004):

(1) How key components and functions, or parts, are integrated

to deliver value to the customer;

(2) How those parts are interconnected within the organization

and throughout its supply chain and stakeholder networks;

and

(3) How the organization generatesvalue, or createsprofit,

through those interconnections.

When clearly understood, an organization's business model can

provide insight into the alignment of high level strategies and un-

derlying actions in an organization,which in turn supports stra-

tegic competitiveness (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2010). Given

that such connections are often only tacitly understood within or-

ganizations (Teece,2010),scholars and practitioners have increas-

ingly turned to business models as a way to make these

connections more explicit(Chesbrough and Rosenbloom,2002;

Amit and Zott, 2010; Schaltegger etal., 2012).Making explicit

these connections through an organization's business modelcan

also support business model innovation through the discovery of

previously unseen opportunities for value creation through trans-

forming existing actions and interconnections in new ways

(Johnson et al.,2008).

2.1.A canvas as a creative tool for business model innovation

Business modeltools can be used to support sustainability

through outside-in or inside-out approaches (Baden-Fuller,1995;

Simanis and Hart, 2009; Chesbrough and Garman,2009). An

outside-in approach involves exploring opportunities for innova-

tion by looking at an organization through different types of

idealized business models,or business model archetypes (Bocken

et al.,2014).This allows firms to explore innovations which may

result from adapting their current business model towards a

particular archetype.Put another way,

“Firms can use one or a selection of business model archetypes for

shaping their own transformation, which are envisaged to provide

assistance in exploring new ways to create and deliver sustainable

value and developing the business modelstructure by providing

guidance to realise the new opportunities” (Bocken et al.,2014,

p.13).

As an outside-in approach,Business modelarchetypes allow

users a relatively easy way to explore the potentialimpacts of

innovating towards different types of business models,inspiring a

A. Joyce,R.L.Paquin / Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e132

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busine

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

ing and integrating economic,environmental,and social value

creation as core to an organization's business model. In particular, it

leverages life-cycle analysisand stakeholder managementper-

spectives within newly created environmental and social canvases

to conceptualize and connectmultiple types of value creation

within a business model perspective.

As a tool,the TLBMC bridges business modelinnovation (Zott

et al., 2011;Spieth et al.,2014) and sustainable business model

development(Boons and Lüdeke-Freund,2013) to support in-

dividuals and organizations in creatively and holistically seeking

competitive sustainability-oriented change as a way to address the

challenges facing us today (Azapagic, 2003; Shrivastava and Statler,

2012). The TLBMC can help users overcome barriers to

sustainability-oriented change within organizations (Lozano, 2013)

by creatively re-conceptualizing their current business models and

communicating potential innovations. Sustainability is argued to be

the key driver of creative innovation for many firms and im-

provements towards sustainability requires innovating on existing

business models to create “new ways of delivering and capturing

value, which will change the basis of competition” (Nidumolu et al.,

2009, p.9). While this point is not new, relatively little work sheds

light on tools which may support the creative conceptual phase of

innovating business models towards organizational sustainability.

Through private consulting, organizational workshops, and

university courses, the TLBMC has been found to help users quickly

visualize and communicate existing business models, make explicit

data and information gaps,and creatively explore potential busi-

ness model innovations which were more explicitly sustainability-

oriented.The TLBMC's layered format helped users better under-

stand and representthe interconnections and relationships be-

tween organizations' current actions and its economic,

environmentaland socialimpacts.By developing environmental

and socialcanvas layers as direct extensions of Osterwalder and

Pigneur (2010) original economic-oriented business model

canvas,each canvas layer provides a horizontal coherence within

itself which also connects across layers, providing a vertical

coherence or more holistic perspective on value creation,which

integrates a view of economic,environmental,and social value

creation throughoutthe business model.Thus, the TLBMC may

enable users to creativity develop broader perspectives and in-

sights into their organizations' actions.

The TLBMC contributes to this specialissue on organizational

creativity and sustainability by proposing a user-friendly toolto

support sustainability-oriented business model innovation. First, as

a multi-layer business model canvas,the TLBMC offers a clear and

relatively easy way to visualize and discuss a business model's

multiple and diverse impacts.Instead of attempting to reduce

multiple types of value into a single canvas,the TLBMC allows

economic,environmentaland social value to be explored hori-

zontally within their own layer and in relationship to each other

through the verticalintegration ofthese layers together.This, in

turn, supports richer discussion and more creative exploration of

sustainability-oriented innovations as a way to explore how action

in one aspect of an organization may ripple through other parts of

the organization.

Second,the TLBMC provides a concise framework to support

visualization, communication and collaboration around innovating

more sustainable businessmodels (Boons and Lüdeke-Freund,

2013).As a relatively easy to understand approach to conceptual-

izing organizations,the TLBMC is as a boundary object (Carlile,

2002) to communicate change to diverse audiences.At its core,

the TLBMC may support transitioning from incrementaland iso-

lated innovations to more integrated and systemic sustainability-

oriented innovations which are likely better suited to meeting

ongoing global crises, and energy and material constraints (Adams

et al.,2015; Shrivastava and Paquin,2011; von Weizsacker et al.,

2009). To support future research and practice around

sustainability-oriented business modelinnovation,the TLBMC is

reproduced in Annex 1 and is available for use under a creative

commons licence.

2. Business models and business model canvases

While the concept of a business model as a“theory of a busi-

ness” is not new (Drucker, 1955), business model research has only

relatively recently gained the attention of many scholars. In fact, as

one recent review noted, scholars “do not [readily] agree on what a

business modelis” (Zott et al., 2011,p.1020).However,for this

article a business model is defined as “the rationale of how an or-

ganization creates,delivers and captures value” (Osterwalder and

Pigneur,2010,p.14).In particular,it is a conceptualization ofan

organization which includes 3 key aspects (Chesbrough,2010;

Osterwalder, 2004):

(1) How key components and functions, or parts, are integrated

to deliver value to the customer;

(2) How those parts are interconnected within the organization

and throughout its supply chain and stakeholder networks;

and

(3) How the organization generatesvalue, or createsprofit,

through those interconnections.

When clearly understood, an organization's business model can

provide insight into the alignment of high level strategies and un-

derlying actions in an organization,which in turn supports stra-

tegic competitiveness (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2010). Given

that such connections are often only tacitly understood within or-

ganizations (Teece,2010),scholars and practitioners have increas-

ingly turned to business models as a way to make these

connections more explicit(Chesbrough and Rosenbloom,2002;

Amit and Zott, 2010; Schaltegger etal., 2012).Making explicit

these connections through an organization's business modelcan

also support business model innovation through the discovery of

previously unseen opportunities for value creation through trans-

forming existing actions and interconnections in new ways

(Johnson et al.,2008).

2.1.A canvas as a creative tool for business model innovation

Business modeltools can be used to support sustainability

through outside-in or inside-out approaches (Baden-Fuller,1995;

Simanis and Hart, 2009; Chesbrough and Garman,2009). An

outside-in approach involves exploring opportunities for innova-

tion by looking at an organization through different types of

idealized business models,or business model archetypes (Bocken

et al.,2014).This allows firms to explore innovations which may

result from adapting their current business model towards a

particular archetype.Put another way,

“Firms can use one or a selection of business model archetypes for

shaping their own transformation, which are envisaged to provide

assistance in exploring new ways to create and deliver sustainable

value and developing the business modelstructure by providing

guidance to realise the new opportunities” (Bocken et al.,2014,

p.13).

As an outside-in approach,Business modelarchetypes allow

users a relatively easy way to explore the potentialimpacts of

innovating towards different types of business models,inspiring a

A. Joyce,R.L.Paquin / Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e132

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busine

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

form of creative confrontation or cross-pollination of diverse ideas

(Fleming,2004). The cross-pollination ofbusiness models ideas

happens when an archetype from one context or industry is rein-

terpreted or applied in another. The term outside-in applies

because an ‘outside’business model archetype is adapted or

translated to the organization.

Inversly,an inside-out approach to business model innovation

involves starting with the current elements in the organization.

First, one details an organization's existing business modelthen

explores the potentialchanges to the model.A business model

canvas (BMC), such as that developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur

(2010) tool can be quite effective here in helping users understand

an organization's business model. The BMC can help users visually

represent of the elements of a business modeland the potential

interconnections and impacts on value creation. As a visual tool, the

BMC can facilitate discussion,debate,and exploration of potential

innovations to the underlying business modelitself; with users

developing a more systemic perspective ofan organization and

highlighting its value creating impacts (Wallin et al., 2013; Bocken

et al., 2014). Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) BMC, in particular, was

developed following design science methods and theory underly-

ing business model development (Osterwalder, 2004) with a focus

on providing accessible, visual representation of a business system

to guide the creative phase of prototyping, gathering feedback, and

revising iterations on business modelinnovation.Their BMC has

been widely adopted by practitioners (Nordic Innovation,2012;

OECD et al.,2012; Kaplan,2012) and researchers (Abraham,2013;

Massa & Tucci,2013).Given its wide adoption and ease of use for

multiple types of users, the business modelcanvas is an ideal

foundation to expand upon by integrating sustainability.

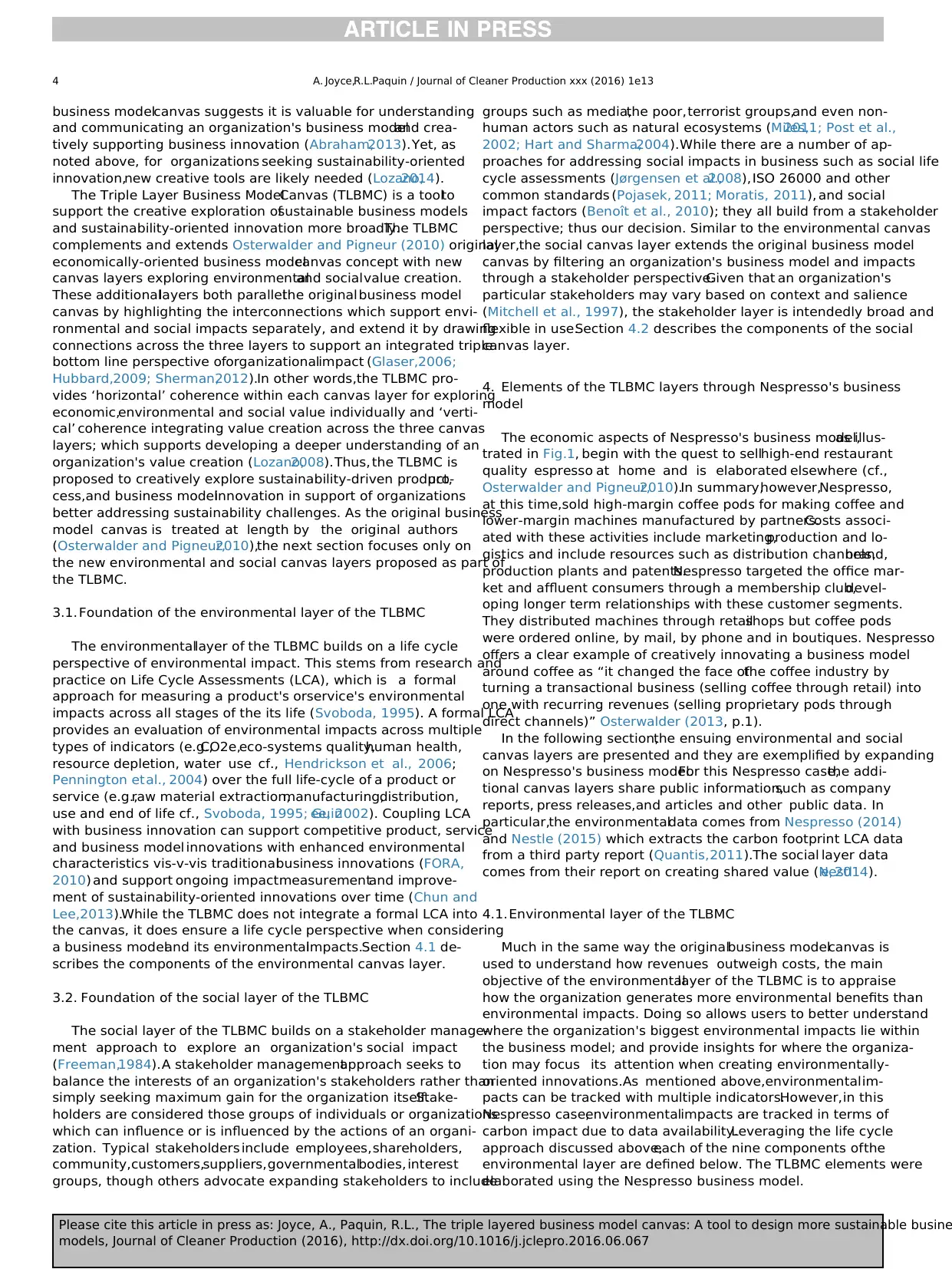

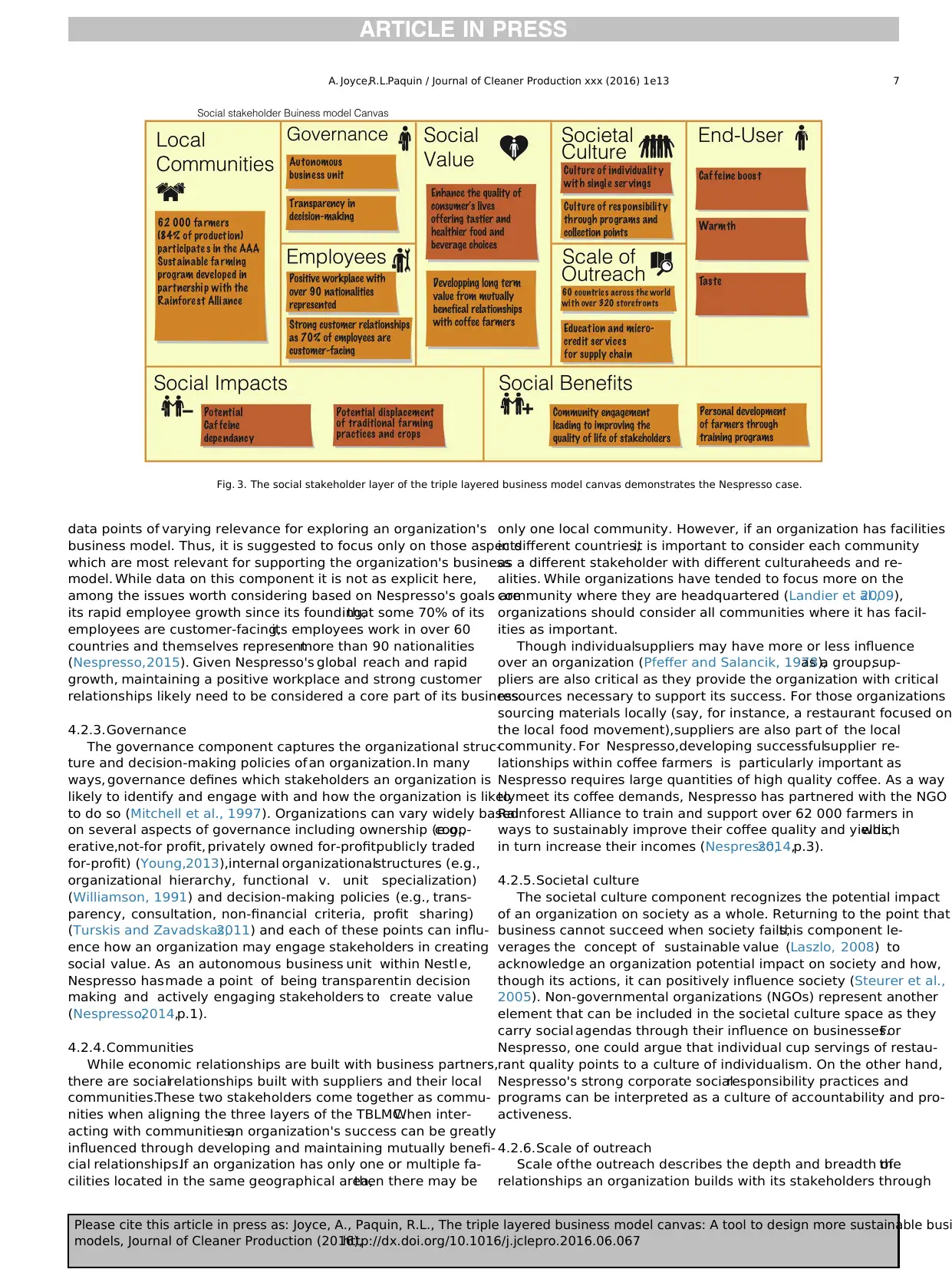

As an example,Fig. 1 shows an interpretation of the Nestle

Nespresso business modelthrough the nine components which

make up Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) original BMC. As discussed

below,their BMC forms the economic layer of the proposed Triple

Layered Business Model Canvas. This is discussed more in section 4.

2.2. Building on the original canvas

The business modelcanvas,as proposed by Osterwalder and

Pigneur (2010),distills an organization's business model into nine

interconnected components e customer value proposition,

segments,customer relationships,channels,key resources,key

activities,partners,costs and revenues.While using it may help

users align profit and purpose to support more sustainability-

oriented value creation on its own (Osterwalder and Pigneur,

2011),in practice environmental and social value is implicitly de-

emphasized behind the canvas's more explicit ‘profit first’or eco-

nomic value orientation (Upward, 2013; Coes, 2014). This has led to

the criticism that developing more sustainability-oriented business

models likely either requires an expert facilitator to support this

orientation or a different tool altogether(Bocken et al., 2013;

Marrewijk and Werre, 2003). A new tool would need to more

explicitly integrate economic, environmental, and social value into

a holistic view of corporate sustainability. As a way to put this into

practice,the TLBMC offers the opportunity for users to explicitly

address a triple bottom line where each canvas layer is dedicated to

a single dimension and together they provide a means to integrate

the relationships and impacts across layers.

The triple bottom line (TBL) perspective,advocating organiza-

tions consider and formally account for their economic,environ-

mental, and social impacts (Savitz,2012),is useful here. While

criticized for simplifying sustainability's complexity (Norman and

MacDonald,2004; Vanclay,2004; Mitchell, 2007), many organi-

zations have adopted TBL thinking, implicitly or explicitly, through

corporate social responsibility reporting and initiatives such as the

Global Report Initiative, Carbon Disclosure Project,and others.

Thus,despite its potential flaws,TBL is a relatively widely under-

stood perspective for considering an organization'seconomic,

environmental,and social and as a conceptual framework for

designing business models to support more sustainable action.

Innovating towards more sustainable business models requires

developing new business models which go beyond an economic

focus to one which generates and integrates economic,environ-

mental and social value through an organization's actions (Bocken

et al., 2013; Willard, 2012). Therefore the structure of the tool leads

to clearly understand and align an organization's actions towards

sustainability at a strategic business model level.

3. Presentation of the triple layered business model canvas

tool

The wide adoption and use of Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010)

Fig. 1.An analysis of Nespresso through Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) original Business Model Canvas, which forms the economic layer of the Triple Layer Business Model

A. Joyce,R.L.Paquin / Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e13 3

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busi

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

(Fleming,2004). The cross-pollination ofbusiness models ideas

happens when an archetype from one context or industry is rein-

terpreted or applied in another. The term outside-in applies

because an ‘outside’business model archetype is adapted or

translated to the organization.

Inversly,an inside-out approach to business model innovation

involves starting with the current elements in the organization.

First, one details an organization's existing business modelthen

explores the potentialchanges to the model.A business model

canvas (BMC), such as that developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur

(2010) tool can be quite effective here in helping users understand

an organization's business model. The BMC can help users visually

represent of the elements of a business modeland the potential

interconnections and impacts on value creation. As a visual tool, the

BMC can facilitate discussion,debate,and exploration of potential

innovations to the underlying business modelitself; with users

developing a more systemic perspective ofan organization and

highlighting its value creating impacts (Wallin et al., 2013; Bocken

et al., 2014). Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) BMC, in particular, was

developed following design science methods and theory underly-

ing business model development (Osterwalder, 2004) with a focus

on providing accessible, visual representation of a business system

to guide the creative phase of prototyping, gathering feedback, and

revising iterations on business modelinnovation.Their BMC has

been widely adopted by practitioners (Nordic Innovation,2012;

OECD et al.,2012; Kaplan,2012) and researchers (Abraham,2013;

Massa & Tucci,2013).Given its wide adoption and ease of use for

multiple types of users, the business modelcanvas is an ideal

foundation to expand upon by integrating sustainability.

As an example,Fig. 1 shows an interpretation of the Nestle

Nespresso business modelthrough the nine components which

make up Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) original BMC. As discussed

below,their BMC forms the economic layer of the proposed Triple

Layered Business Model Canvas. This is discussed more in section 4.

2.2. Building on the original canvas

The business modelcanvas,as proposed by Osterwalder and

Pigneur (2010),distills an organization's business model into nine

interconnected components e customer value proposition,

segments,customer relationships,channels,key resources,key

activities,partners,costs and revenues.While using it may help

users align profit and purpose to support more sustainability-

oriented value creation on its own (Osterwalder and Pigneur,

2011),in practice environmental and social value is implicitly de-

emphasized behind the canvas's more explicit ‘profit first’or eco-

nomic value orientation (Upward, 2013; Coes, 2014). This has led to

the criticism that developing more sustainability-oriented business

models likely either requires an expert facilitator to support this

orientation or a different tool altogether(Bocken et al., 2013;

Marrewijk and Werre, 2003). A new tool would need to more

explicitly integrate economic, environmental, and social value into

a holistic view of corporate sustainability. As a way to put this into

practice,the TLBMC offers the opportunity for users to explicitly

address a triple bottom line where each canvas layer is dedicated to

a single dimension and together they provide a means to integrate

the relationships and impacts across layers.

The triple bottom line (TBL) perspective,advocating organiza-

tions consider and formally account for their economic,environ-

mental, and social impacts (Savitz,2012),is useful here. While

criticized for simplifying sustainability's complexity (Norman and

MacDonald,2004; Vanclay,2004; Mitchell, 2007), many organi-

zations have adopted TBL thinking, implicitly or explicitly, through

corporate social responsibility reporting and initiatives such as the

Global Report Initiative, Carbon Disclosure Project,and others.

Thus,despite its potential flaws,TBL is a relatively widely under-

stood perspective for considering an organization'seconomic,

environmental,and social and as a conceptual framework for

designing business models to support more sustainable action.

Innovating towards more sustainable business models requires

developing new business models which go beyond an economic

focus to one which generates and integrates economic,environ-

mental and social value through an organization's actions (Bocken

et al., 2013; Willard, 2012). Therefore the structure of the tool leads

to clearly understand and align an organization's actions towards

sustainability at a strategic business model level.

3. Presentation of the triple layered business model canvas

tool

The wide adoption and use of Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010)

Fig. 1.An analysis of Nespresso through Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) original Business Model Canvas, which forms the economic layer of the Triple Layer Business Model

A. Joyce,R.L.Paquin / Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e13 3

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busi

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

business modelcanvas suggests it is valuable for understanding

and communicating an organization's business modeland crea-

tively supporting business innovation (Abraham,2013).Yet, as

noted above, for organizations seeking sustainability-oriented

innovation,new creative tools are likely needed (Lozano,2014).

The Triple Layer Business ModelCanvas (TLBMC) is a toolto

support the creative exploration ofsustainable business models

and sustainability-oriented innovation more broadly.The TLBMC

complements and extends Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) original

economically-oriented business modelcanvas concept with new

canvas layers exploring environmentaland socialvalue creation.

These additionallayers both parallelthe original business model

canvas by highlighting the interconnections which support envi-

ronmental and social impacts separately, and extend it by drawing

connections across the three layers to support an integrated triple

bottom line perspective oforganizationalimpact (Glaser,2006;

Hubbard,2009; Sherman,2012).In other words,the TLBMC pro-

vides ‘horizontal’ coherence within each canvas layer for exploring

economic,environmental and social value individually and ‘verti-

cal’ coherence integrating value creation across the three canvas

layers; which supports developing a deeper understanding of an

organization's value creation (Lozano,2008).Thus, the TLBMC is

proposed to creatively explore sustainability-driven product,pro-

cess,and business modelinnovation in support of organizations

better addressing sustainability challenges. As the original business

model canvas is treated at length by the original authors

(Osterwalder and Pigneur,2010),the next section focuses only on

the new environmental and social canvas layers proposed as part of

the TLBMC.

3.1. Foundation of the environmental layer of the TLBMC

The environmentallayer of the TLBMC builds on a life cycle

perspective of environmental impact. This stems from research and

practice on Life Cycle Assessments (LCA), which is a formal

approach for measuring a product's orservice's environmental

impacts across all stages of the its life (Svoboda, 1995). A formal LCA

provides an evaluation of environmental impacts across multiple

types of indicators (e.g.,CO2e,eco-systems quality,human health,

resource depletion, water use cf., Hendrickson et al., 2006;

Pennington etal., 2004) over the full life-cycle of a product or

service (e.g.,raw material extraction,manufacturing,distribution,

use and end of life cf., Svoboda, 1995; Guinee, 2002). Coupling LCA

with business innovation can support competitive product, service

and business model innovations with enhanced environmental

characteristics vis-v-vis traditionalbusiness innovations (FORA,

2010) and support ongoing impactmeasurementand improve-

ment of sustainability-oriented innovations over time (Chun and

Lee,2013).While the TLBMC does not integrate a formal LCA into

the canvas, it does ensure a life cycle perspective when considering

a business modeland its environmentalimpacts.Section 4.1 de-

scribes the components of the environmental canvas layer.

3.2. Foundation of the social layer of the TLBMC

The social layer of the TLBMC builds on a stakeholder manage-

ment approach to explore an organization's social impact

(Freeman,1984).A stakeholder managementapproach seeks to

balance the interests of an organization's stakeholders rather than

simply seeking maximum gain for the organization itself.Stake-

holders are considered those groups of individuals or organizations

which can influence or is influenced by the actions of an organi-

zation. Typical stakeholders include employees,shareholders,

community,customers,suppliers,governmentalbodies, interest

groups, though others advocate expanding stakeholders to include

groups such as media,the poor,terrorist groups,and even non-

human actors such as natural ecosystems (Miles,2011; Post et al.,

2002; Hart and Sharma,2004).While there are a number of ap-

proaches for addressing social impacts in business such as social life

cycle assessments (Jørgensen et al.,2008),ISO 26000 and other

common standards (Pojasek, 2011; Moratis, 2011), and social

impact factors (Benoît et al., 2010); they all build from a stakeholder

perspective; thus our decision. Similar to the environmental canvas

layer,the social canvas layer extends the original business model

canvas by filtering an organization's business model and impacts

through a stakeholder perspective.Given that an organization's

particular stakeholders may vary based on context and salience

(Mitchell et al., 1997), the stakeholder layer is intendedly broad and

flexible in use.Section 4.2 describes the components of the social

canvas layer.

4. Elements of the TLBMC layers through Nespresso's business

model

The economic aspects of Nespresso's business model,as illus-

trated in Fig.1, begin with the quest to sellhigh-end restaurant

quality espresso at home and is elaborated elsewhere (cf.,

Osterwalder and Pigneur,2010).In summary,however,Nespresso,

at this time,sold high-margin coffee pods for making coffee and

lower-margin machines manufactured by partners.Costs associ-

ated with these activities include marketing,production and lo-

gistics and include resources such as distribution channels,brand,

production plants and patents.Nespresso targeted the office mar-

ket and affluent consumers through a membership club,devel-

oping longer term relationships with these customer segments.

They distributed machines through retailshops but coffee pods

were ordered online, by mail, by phone and in boutiques. Nespresso

offers a clear example of creatively innovating a business model

around coffee as “it changed the face ofthe coffee industry by

turning a transactional business (selling coffee through retail) into

one with recurring revenues (selling proprietary pods through

direct channels)” Osterwalder (2013, p.1).

In the following section,the ensuing environmental and social

canvas layers are presented and they are exemplified by expanding

on Nespresso's business model.For this Nespresso case,the addi-

tional canvas layers share public information,such as company

reports, press releases,and articles and other public data. In

particular,the environmentaldata comes from Nespresso (2014)

and Nestle (2015) which extracts the carbon footprint LCA data

from a third party report (Quantis,2011).The social layer data

comes from their report on creating shared value (Nestle, 2014).

4.1.Environmental layer of the TLBMC

Much in the same way the originalbusiness modelcanvas is

used to understand how revenues outweigh costs, the main

objective of the environmentallayer of the TLBMC is to appraise

how the organization generates more environmental benefits than

environmental impacts. Doing so allows users to better understand

where the organization's biggest environmental impacts lie within

the business model; and provide insights for where the organiza-

tion may focus its attention when creating environmentally-

oriented innovations.As mentioned above,environmentalim-

pacts can be tracked with multiple indicators.However,in this

Nespresso case,environmentalimpacts are tracked in terms of

carbon impact due to data availability.Leveraging the life cycle

approach discussed above,each of the nine components ofthe

environmental layer are defined below. The TLBMC elements were

elaborated using the Nespresso business model.

A. Joyce,R.L.Paquin / Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e134

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busine

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

and communicating an organization's business modeland crea-

tively supporting business innovation (Abraham,2013).Yet, as

noted above, for organizations seeking sustainability-oriented

innovation,new creative tools are likely needed (Lozano,2014).

The Triple Layer Business ModelCanvas (TLBMC) is a toolto

support the creative exploration ofsustainable business models

and sustainability-oriented innovation more broadly.The TLBMC

complements and extends Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) original

economically-oriented business modelcanvas concept with new

canvas layers exploring environmentaland socialvalue creation.

These additionallayers both parallelthe original business model

canvas by highlighting the interconnections which support envi-

ronmental and social impacts separately, and extend it by drawing

connections across the three layers to support an integrated triple

bottom line perspective oforganizationalimpact (Glaser,2006;

Hubbard,2009; Sherman,2012).In other words,the TLBMC pro-

vides ‘horizontal’ coherence within each canvas layer for exploring

economic,environmental and social value individually and ‘verti-

cal’ coherence integrating value creation across the three canvas

layers; which supports developing a deeper understanding of an

organization's value creation (Lozano,2008).Thus, the TLBMC is

proposed to creatively explore sustainability-driven product,pro-

cess,and business modelinnovation in support of organizations

better addressing sustainability challenges. As the original business

model canvas is treated at length by the original authors

(Osterwalder and Pigneur,2010),the next section focuses only on

the new environmental and social canvas layers proposed as part of

the TLBMC.

3.1. Foundation of the environmental layer of the TLBMC

The environmentallayer of the TLBMC builds on a life cycle

perspective of environmental impact. This stems from research and

practice on Life Cycle Assessments (LCA), which is a formal

approach for measuring a product's orservice's environmental

impacts across all stages of the its life (Svoboda, 1995). A formal LCA

provides an evaluation of environmental impacts across multiple

types of indicators (e.g.,CO2e,eco-systems quality,human health,

resource depletion, water use cf., Hendrickson et al., 2006;

Pennington etal., 2004) over the full life-cycle of a product or

service (e.g.,raw material extraction,manufacturing,distribution,

use and end of life cf., Svoboda, 1995; Guinee, 2002). Coupling LCA

with business innovation can support competitive product, service

and business model innovations with enhanced environmental

characteristics vis-v-vis traditionalbusiness innovations (FORA,

2010) and support ongoing impactmeasurementand improve-

ment of sustainability-oriented innovations over time (Chun and

Lee,2013).While the TLBMC does not integrate a formal LCA into

the canvas, it does ensure a life cycle perspective when considering

a business modeland its environmentalimpacts.Section 4.1 de-

scribes the components of the environmental canvas layer.

3.2. Foundation of the social layer of the TLBMC

The social layer of the TLBMC builds on a stakeholder manage-

ment approach to explore an organization's social impact

(Freeman,1984).A stakeholder managementapproach seeks to

balance the interests of an organization's stakeholders rather than

simply seeking maximum gain for the organization itself.Stake-

holders are considered those groups of individuals or organizations

which can influence or is influenced by the actions of an organi-

zation. Typical stakeholders include employees,shareholders,

community,customers,suppliers,governmentalbodies, interest

groups, though others advocate expanding stakeholders to include

groups such as media,the poor,terrorist groups,and even non-

human actors such as natural ecosystems (Miles,2011; Post et al.,

2002; Hart and Sharma,2004).While there are a number of ap-

proaches for addressing social impacts in business such as social life

cycle assessments (Jørgensen et al.,2008),ISO 26000 and other

common standards (Pojasek, 2011; Moratis, 2011), and social

impact factors (Benoît et al., 2010); they all build from a stakeholder

perspective; thus our decision. Similar to the environmental canvas

layer,the social canvas layer extends the original business model

canvas by filtering an organization's business model and impacts

through a stakeholder perspective.Given that an organization's

particular stakeholders may vary based on context and salience

(Mitchell et al., 1997), the stakeholder layer is intendedly broad and

flexible in use.Section 4.2 describes the components of the social

canvas layer.

4. Elements of the TLBMC layers through Nespresso's business

model

The economic aspects of Nespresso's business model,as illus-

trated in Fig.1, begin with the quest to sellhigh-end restaurant

quality espresso at home and is elaborated elsewhere (cf.,

Osterwalder and Pigneur,2010).In summary,however,Nespresso,

at this time,sold high-margin coffee pods for making coffee and

lower-margin machines manufactured by partners.Costs associ-

ated with these activities include marketing,production and lo-

gistics and include resources such as distribution channels,brand,

production plants and patents.Nespresso targeted the office mar-

ket and affluent consumers through a membership club,devel-

oping longer term relationships with these customer segments.

They distributed machines through retailshops but coffee pods

were ordered online, by mail, by phone and in boutiques. Nespresso

offers a clear example of creatively innovating a business model

around coffee as “it changed the face ofthe coffee industry by

turning a transactional business (selling coffee through retail) into

one with recurring revenues (selling proprietary pods through

direct channels)” Osterwalder (2013, p.1).

In the following section,the ensuing environmental and social

canvas layers are presented and they are exemplified by expanding

on Nespresso's business model.For this Nespresso case,the addi-

tional canvas layers share public information,such as company

reports, press releases,and articles and other public data. In

particular,the environmentaldata comes from Nespresso (2014)

and Nestle (2015) which extracts the carbon footprint LCA data

from a third party report (Quantis,2011).The social layer data

comes from their report on creating shared value (Nestle, 2014).

4.1.Environmental layer of the TLBMC

Much in the same way the originalbusiness modelcanvas is

used to understand how revenues outweigh costs, the main

objective of the environmentallayer of the TLBMC is to appraise

how the organization generates more environmental benefits than

environmental impacts. Doing so allows users to better understand

where the organization's biggest environmental impacts lie within

the business model; and provide insights for where the organiza-

tion may focus its attention when creating environmentally-

oriented innovations.As mentioned above,environmentalim-

pacts can be tracked with multiple indicators.However,in this

Nespresso case,environmentalimpacts are tracked in terms of

carbon impact due to data availability.Leveraging the life cycle

approach discussed above,each of the nine components ofthe

environmental layer are defined below. The TLBMC elements were

elaborated using the Nespresso business model.

A. Joyce,R.L.Paquin / Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e134

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busine

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

4.1.1.Functional value

The functional value describes the focal outputs of a service (or

product) by the organization under examination.It emulates the

functional unit in a life cycle assessment,which is a quantitative

description of either the service performance or the needs fulfilled

in the investigated product system (Rebitzer et al.,2004).The dif-

ference between a LCA's functional unit and the functional value

can be seen as one of usage. For example, the functional unit of the

Nespresso LCA is a 40 ml espresso pod, while the functional value is

the total of these pods consumed by customers in a given time-

frame such as a year.The point of defining the functional value is

first to clarify what is being examined in the environmental layer;

and second,to serve as a baseline for exploring the impacts of

alternative potential business models.

4.1.2.Materials

The materials component is the environmental extension of the

key resources component from the original business model canvas.

Materials refer to the bio-physical stocks used to render the func-

tional value.For example manufacturers purchase and transform

large amounts of physical materials, whereas service organizations

tend to require materials in the form of building infrastructure and

information technology. These service organizations also consume

significant materialresources in the form of assets such as com-

puters,vehicles and office buildings.While introducing allmate-

rials into the canvas is not practical,it is important to note an

organization's key materials and their environmental impact.For

Nespresso, materials are first and foremost the coffee beans which

represent 19.9% of its carbon footprint. The aluminum used for the

capsules is also to be included in the materials of the life cycle as it

represents 6% of the carbon footprint.

4.1.3.Production

The production component extends the key activities compo-

nent from the original business model canvas to the environmental

layer and captures the actions that the organization undertakes to

create value.Production for a manufacturer may involve trans-

forming raw or unfinished materials into higher value outputs.

Production for a service provider can involve running an IT infra-

structure, transporting people or other logistics, using office spaces

and hosting service points. As with materials, the focus here is not

on all activities but rather those which are core to the organization

and which have high environmentalimpact.For Nespresso,the

industrial processes to prepare the coffee beans represent 4.5% of

the carbon impact and the manufacturing of the packaging capsules

represents 13.3%.

4.1.4.Supplies and outsourcing

Supplies and out-sourcing represent all the other various ma-

terial and production activities that are necessary for the functional

value but not considered ‘core’to the organization.Similar to the

original business model canvas,the distinction here is between is

considered core versusnon-core to support the organization's

value creation. This can be considered in terms of actions which are

unique to the organization and support its competitive advantage

and those actions which are necessary but not unique (Porter, 1985)

and may also be conceived of as those actions which are kept in-

house versus those which are outsourced,though this can be not

strictly accurate. Within the environmental layer, examples of may

include water or energy which,while they could come from in-

house sources (localwells and on-site energy production); they

are likely to be supplied by local utility companies.As such,many

organizations have little influence in these areas unless they are

willing to take more control over these actions through, for

example, creating on-site energy and utility services. In the

available carbon footprintdata of the coffee pod manufacturer,

most of the impacts of supplies and outsourcing such as the ma-

chines and pods were included in the use phase.

4.1.5.Distribution

As with the originalbusiness model,distribution involves the

transportation ofgoods. In the case of a service provider or a

product manufacturer,the distribution representsthe physical

means by which the organization ensures access to its functional

value. Thus within the environmental layer, it is the combination of

the transportation modes,the distances travelled and the weights

of what is shipped which is to be considered.As well, issues of

packaging and delivery logistics may become important here.For

Nespresso, distribution involves the shipment of coffee beans and,

subsequently manufactured,coffee pods over thousands ofkilo-

metres with the total effect of representing only 4.6% of Nespresso's

carbon footprint. Their distribution practicesfavour train over

trucks.In addition,the products are packaged in cardboard boxes

which represent 3.6% of their carbon footprint.

4.1.6.Use phase

The use phase focuses on the impact of the client's partaking in

the organization's functional value, or core service and/or product.

This would include maintenance and repair of products when

relevant;and should include some consideration ofthe client's

material resource and energy requirements through use.Many

electronic products incur use phase impacts when charging a de-

vice and using an infrastructure needed to support the network of

users. This can outweigh production impacts (Nokia, 2005). As well,

the line between production and use phase may not be clear,

especially as organizations increasingly offer co-creation of services

(e.g., user created content) and product sharing (e.g., car sharing) in

lieu of more traditional product and service business models

(Prahalad and Ramaswamy,2004). For Nespresso,the use phase

consists of three elements. First, a client's energy and water needs

to prepare coffee add up to 10.9%.Second,the machine use and

production represents 7.8%.And lastly,the coffee pod production

and washing is the largest single element of the entire life cycle

with 28% of Nespresso's carbon impact.

4.1.7.End-of-life

End-of-life is when the client chooses to end the consumption of

the functional value and often entails issues of material reuse such

as remanufacturing,repurposing,recycling,disassembly,incinera-

tion or disposal of a product.From an environmental perspective,

this component supports the organization exploring ways to

manage its impact through extending its responsibility beyond the

initially conceived value of its products.Increasingly governments

are forcing organizations to address this through various substance

restrictions (European Commission, 2012) and recycling re-

quirements (Environment Agency,2012).This can also be an op-

portunity for organizations to creatively explore new business

models such as product service systems (Mont and Tukker,2006;

Bey and McAloone,2006) and industrial symbiosis (Paquin et al.,

2013).For Nespresso,end-of-life means addressing the impacts of

its spent expresso pods consisting of spent coffee and aluminum.

The capsules, the packaging and the machine in a mix of end of life

scenarios that includes landfilland recycling adds up to 5.5% of

Nespresso's totalcarbon impact.However,the pods can only be

recycled if taken back to one of the 14 000 Nespresso dedicated

collection points (Nespresso, 2014).

4.1.8.Environmental impacts

The environmental impacts component addresses the ecological

costs of the organization's actions.While a traditional business

A. Joyce,R.L.Paquin / Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e13 5

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busi

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

The functional value describes the focal outputs of a service (or

product) by the organization under examination.It emulates the

functional unit in a life cycle assessment,which is a quantitative

description of either the service performance or the needs fulfilled

in the investigated product system (Rebitzer et al.,2004).The dif-

ference between a LCA's functional unit and the functional value

can be seen as one of usage. For example, the functional unit of the

Nespresso LCA is a 40 ml espresso pod, while the functional value is

the total of these pods consumed by customers in a given time-

frame such as a year.The point of defining the functional value is

first to clarify what is being examined in the environmental layer;

and second,to serve as a baseline for exploring the impacts of

alternative potential business models.

4.1.2.Materials

The materials component is the environmental extension of the

key resources component from the original business model canvas.

Materials refer to the bio-physical stocks used to render the func-

tional value.For example manufacturers purchase and transform

large amounts of physical materials, whereas service organizations

tend to require materials in the form of building infrastructure and

information technology. These service organizations also consume

significant materialresources in the form of assets such as com-

puters,vehicles and office buildings.While introducing allmate-

rials into the canvas is not practical,it is important to note an

organization's key materials and their environmental impact.For

Nespresso, materials are first and foremost the coffee beans which

represent 19.9% of its carbon footprint. The aluminum used for the

capsules is also to be included in the materials of the life cycle as it

represents 6% of the carbon footprint.

4.1.3.Production

The production component extends the key activities compo-

nent from the original business model canvas to the environmental

layer and captures the actions that the organization undertakes to

create value.Production for a manufacturer may involve trans-

forming raw or unfinished materials into higher value outputs.

Production for a service provider can involve running an IT infra-

structure, transporting people or other logistics, using office spaces

and hosting service points. As with materials, the focus here is not

on all activities but rather those which are core to the organization

and which have high environmentalimpact.For Nespresso,the

industrial processes to prepare the coffee beans represent 4.5% of

the carbon impact and the manufacturing of the packaging capsules

represents 13.3%.

4.1.4.Supplies and outsourcing

Supplies and out-sourcing represent all the other various ma-

terial and production activities that are necessary for the functional

value but not considered ‘core’to the organization.Similar to the

original business model canvas,the distinction here is between is

considered core versusnon-core to support the organization's

value creation. This can be considered in terms of actions which are

unique to the organization and support its competitive advantage

and those actions which are necessary but not unique (Porter, 1985)

and may also be conceived of as those actions which are kept in-

house versus those which are outsourced,though this can be not

strictly accurate. Within the environmental layer, examples of may

include water or energy which,while they could come from in-

house sources (localwells and on-site energy production); they

are likely to be supplied by local utility companies.As such,many

organizations have little influence in these areas unless they are

willing to take more control over these actions through, for

example, creating on-site energy and utility services. In the

available carbon footprintdata of the coffee pod manufacturer,

most of the impacts of supplies and outsourcing such as the ma-

chines and pods were included in the use phase.

4.1.5.Distribution

As with the originalbusiness model,distribution involves the

transportation ofgoods. In the case of a service provider or a

product manufacturer,the distribution representsthe physical

means by which the organization ensures access to its functional

value. Thus within the environmental layer, it is the combination of

the transportation modes,the distances travelled and the weights

of what is shipped which is to be considered.As well, issues of

packaging and delivery logistics may become important here.For

Nespresso, distribution involves the shipment of coffee beans and,

subsequently manufactured,coffee pods over thousands ofkilo-

metres with the total effect of representing only 4.6% of Nespresso's

carbon footprint. Their distribution practicesfavour train over

trucks.In addition,the products are packaged in cardboard boxes

which represent 3.6% of their carbon footprint.

4.1.6.Use phase

The use phase focuses on the impact of the client's partaking in

the organization's functional value, or core service and/or product.

This would include maintenance and repair of products when

relevant;and should include some consideration ofthe client's

material resource and energy requirements through use.Many

electronic products incur use phase impacts when charging a de-

vice and using an infrastructure needed to support the network of

users. This can outweigh production impacts (Nokia, 2005). As well,

the line between production and use phase may not be clear,

especially as organizations increasingly offer co-creation of services

(e.g., user created content) and product sharing (e.g., car sharing) in

lieu of more traditional product and service business models

(Prahalad and Ramaswamy,2004). For Nespresso,the use phase

consists of three elements. First, a client's energy and water needs

to prepare coffee add up to 10.9%.Second,the machine use and

production represents 7.8%.And lastly,the coffee pod production

and washing is the largest single element of the entire life cycle

with 28% of Nespresso's carbon impact.

4.1.7.End-of-life

End-of-life is when the client chooses to end the consumption of

the functional value and often entails issues of material reuse such

as remanufacturing,repurposing,recycling,disassembly,incinera-

tion or disposal of a product.From an environmental perspective,

this component supports the organization exploring ways to

manage its impact through extending its responsibility beyond the

initially conceived value of its products.Increasingly governments

are forcing organizations to address this through various substance

restrictions (European Commission, 2012) and recycling re-

quirements (Environment Agency,2012).This can also be an op-

portunity for organizations to creatively explore new business

models such as product service systems (Mont and Tukker,2006;

Bey and McAloone,2006) and industrial symbiosis (Paquin et al.,

2013).For Nespresso,end-of-life means addressing the impacts of

its spent expresso pods consisting of spent coffee and aluminum.

The capsules, the packaging and the machine in a mix of end of life

scenarios that includes landfilland recycling adds up to 5.5% of

Nespresso's totalcarbon impact.However,the pods can only be

recycled if taken back to one of the 14 000 Nespresso dedicated

collection points (Nespresso, 2014).

4.1.8.Environmental impacts

The environmental impacts component addresses the ecological

costs of the organization's actions.While a traditional business

A. Joyce,R.L.Paquin / Journal of Cleaner Production xxx (2016) 1e13 5

Please cite this article in press as: Joyce, A., Paquin, R.L., The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable busi

models, Journal of Cleaner Production (2016),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

model often summarizes organizational impacts primarily as

financial costs,the environmentalimpacts components extends

that to include the organization's ecologicalcosts.Based on LCA

research (Jolliet et al., 2003), these performance indicators may be

related to bio-physical measures such as CO2e emissions,human

health,ecosystem impact,natural resource depletion,water con-

sumption.Some environmentalindicators can take the form of

traditional business metrics still related to LCA (De Benedetto and

Klemes, 2009) such as energy consumption,water use and emis-

sions. And,as with exploring an organization's financial costs, this

provides an opportunity to explore where,in the organization's

actions,are its biggest environmentalimpacts.For Nespresso,its

environmental impacts can point to its largest contributor, the use

stage with 46.6% of the carbon footprint.

4.1.9.Environmental benefits

Similar to the relationship between environmental impacts and

costs, environmental benefits extends the concept of value creation

beyond purely financial value.It encompasses the ecological value

the organization creates through environmental impact reductions

and even regenerative positive ecologicalvalue.From a sustain-

ability perspective,this component provides space for an organi-

zation to explicitly explore product,service,and business model

innovations which may reduce negative and/or increase positive

environmentalthrough its actions.For Nespresso,an example of

this would be the 20.7% reduction in carbon emissions they ach-

ieved by redesigning the machines to be energy efficient.By eval-

uating environmentalimpacts with a life cycle approach in the

business model canvas,the description of impacts can move

beyond generalizations and intuitions to establish a firmer even

quantitative basis upon which to design more sustainable business

models.

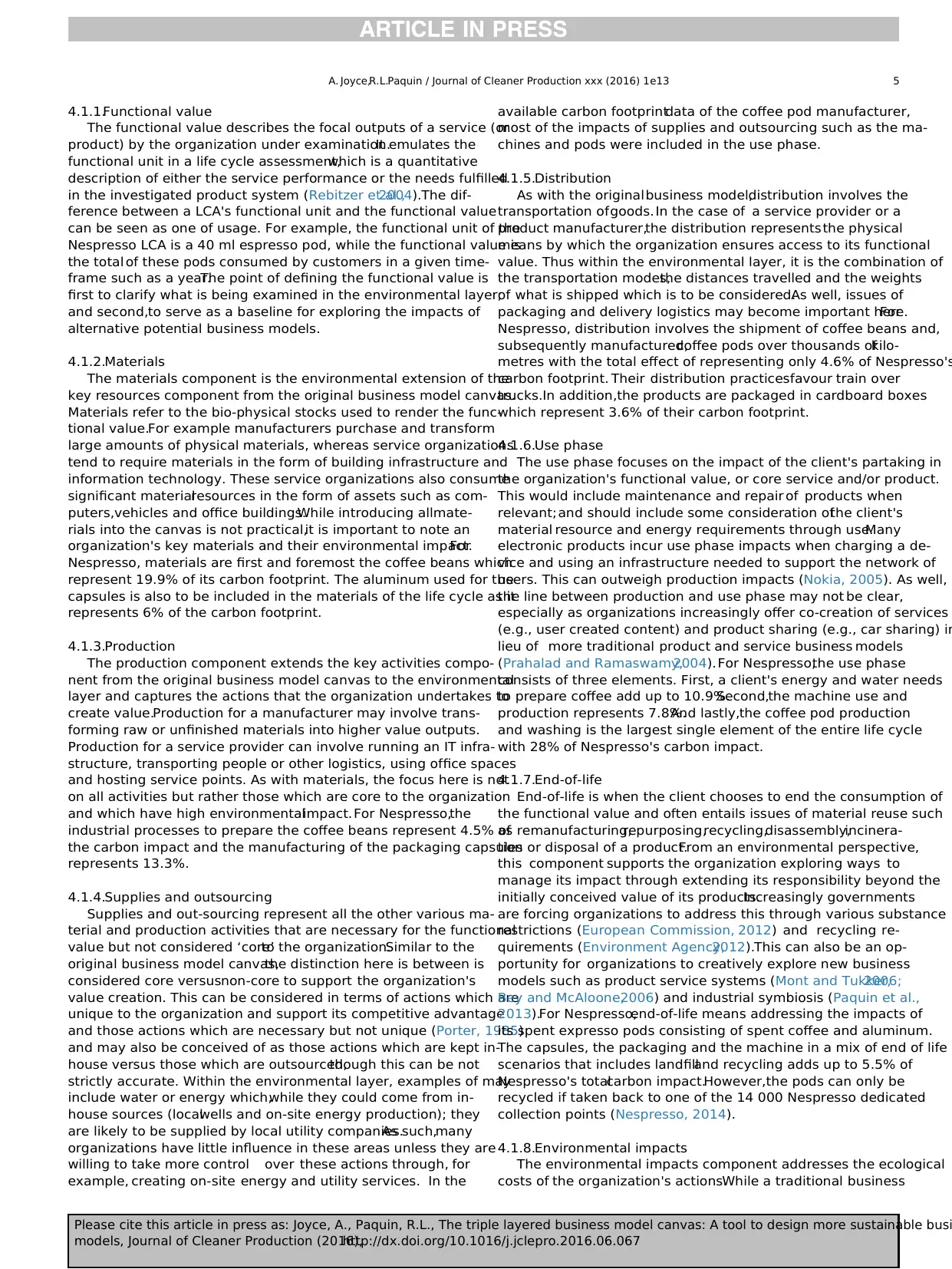

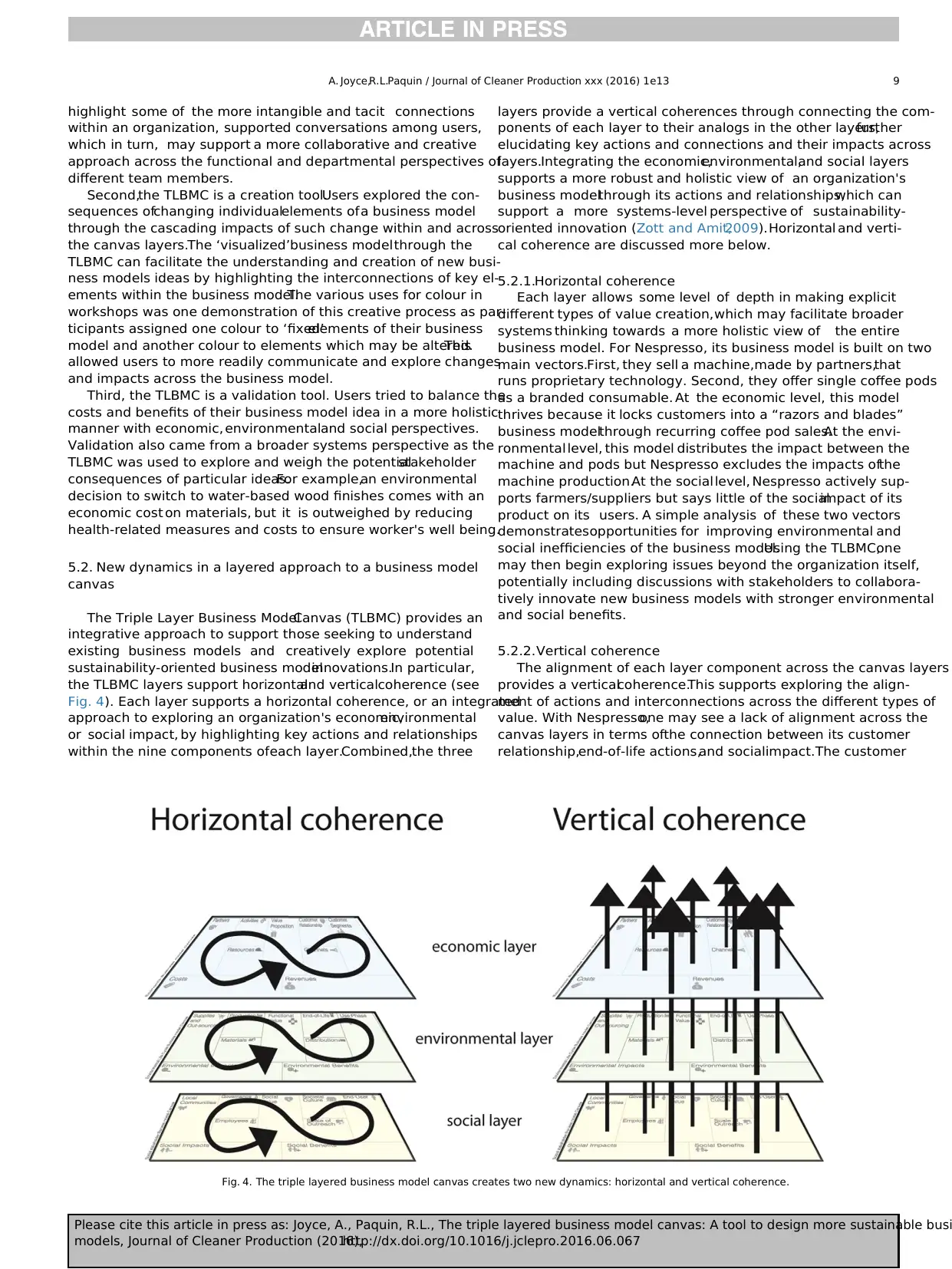

In Fig. 2, a life cycle approach informs the environmental layer as

projected through the original business model canvas. The content

provided inside the canvas framework has been extracted from the

report available on the company's website (Nespresso, 2014) which

recounts the third party life cycle assessment (see Fig.3).

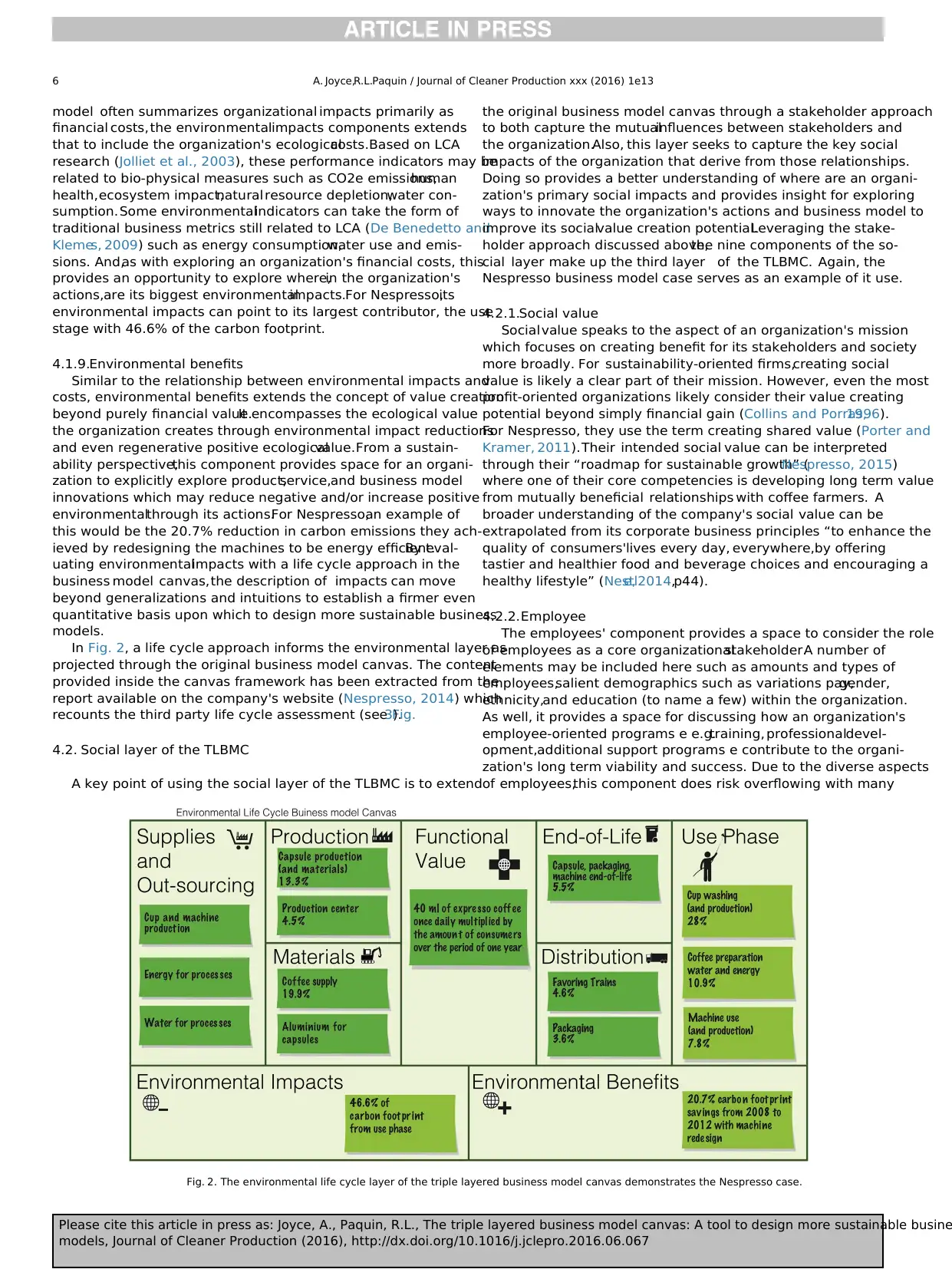

4.2. Social layer of the TLBMC

A key point of using the social layer of the TLBMC is to extend

the original business model canvas through a stakeholder approach

to both capture the mutualinfluences between stakeholders and

the organization.Also, this layer seeks to capture the key social

impacts of the organization that derive from those relationships.

Doing so provides a better understanding of where are an organi-

zation's primary social impacts and provides insight for exploring

ways to innovate the organization's actions and business model to

improve its socialvalue creation potential.Leveraging the stake-

holder approach discussed above,the nine components of the so-

cial layer make up the third layer of the TLBMC. Again, the

Nespresso business model case serves as an example of it use.

4.2.1.Social value

Socialvalue speaks to the aspect of an organization's mission

which focuses on creating benefit for its stakeholders and society

more broadly. For sustainability-oriented firms,creating social

value is likely a clear part of their mission. However, even the most

profit-oriented organizations likely consider their value creating