The extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering among undergraduate nursing students: Implications for pedagogy in nursing and midwifery education

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/05

|39

|9146

|52

AI Summary

This article discusses the benefits of volunteering for nursing students, including increased exposure to diverse environments, improved critical thinking skills, and enhanced self-confidence. The study aims to understand the extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering among nursing students and make recommendations for the nursing curriculum. The article highlights the importance of embedding volunteering within academic programs and structured learning events to teach care and compassion to nursing students.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313012210

The extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering among undergradute

nursing students: Implications for pedagogy in nursing and midifery education

Article in Nurse education in practice · January 2017

DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.01.004

CITATIONS

3

READS

67

4 authors:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

South Asian Nursing Students projectView project

Zimbabwean nursing students proejctView project

Sue Dyson

Middlesex University, UK

27PUBLICATIONS129CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Liang Qin Liu

26PUBLICATIONS284CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Olga B A van den Akker

Middlesex University, UK

162PUBLICATIONS1,845CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Mike O'Driscoll

Middlesex University, UK

15PUBLICATIONS178CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Sue Dyson on 15 February 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering among undergradute

nursing students: Implications for pedagogy in nursing and midifery education

Article in Nurse education in practice · January 2017

DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.01.004

CITATIONS

3

READS

67

4 authors:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

South Asian Nursing Students projectView project

Zimbabwean nursing students proejctView project

Sue Dyson

Middlesex University, UK

27PUBLICATIONS129CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Liang Qin Liu

26PUBLICATIONS284CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Olga B A van den Akker

Middlesex University, UK

162PUBLICATIONS1,845CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Mike O'Driscoll

Middlesex University, UK

15PUBLICATIONS178CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Sue Dyson on 15 February 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Accepted Manuscript

The extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering among undergradute

nursing students: Implications for pedagogy in nursing and midifery education

S.E. Dyson, L. Liu, O. van den Akker, Mike O'Driscoll

PII: S1471-5953(17)30065-3

DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.01.004

Reference: YNEPR 2186

To appear in: Nurse Education in Practice

Received Date:6 April 2016

Revised Date: 1 September 2016

Accepted Date:25 January 2017

Please cite this article as: Dyson, S.E., Liu, L., van den Akker, O., O'Driscoll, M., The extent, variability,

and attitudes towards volunteering among undergradute nursing students: Implications for pedagogy in

nursing and midifery education,Nurse Education in Practice (2017), doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.01.004.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to

our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo

copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please

note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all

legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering among undergradute

nursing students: Implications for pedagogy in nursing and midifery education

S.E. Dyson, L. Liu, O. van den Akker, Mike O'Driscoll

PII: S1471-5953(17)30065-3

DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.01.004

Reference: YNEPR 2186

To appear in: Nurse Education in Practice

Received Date:6 April 2016

Revised Date: 1 September 2016

Accepted Date:25 January 2017

Please cite this article as: Dyson, S.E., Liu, L., van den Akker, O., O'Driscoll, M., The extent, variability,

and attitudes towards volunteering among undergradute nursing students: Implications for pedagogy in

nursing and midifery education,Nurse Education in Practice (2017), doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.01.004.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to

our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo

copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please

note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all

legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

Title page

THE EXTENT, VARIABILITY, AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS VOLUNTEERING AMONG

UNDERGRADUTE NURSING STUDENTS: IMPLICATIONS FOR PEDAGOGY IN NURSING

AND MIDIFERY EDUCATION.

Dyson, S.E, Liu, L and van den Akker, O

Corresponding author: Professor Sue Dyson

Professor Sue Dyson1

1Middlesex University

School of Health and Education

Room WG 17, Williams Building

The Burroughs

Hendon

London NW4 4BT

Tel: +44 (0) 20 8411 2887

Email: s.dyson@mdx.ac.uk

Dr Liang Liu2

2Middlesex University

School of Health and Education

Room WG 17, Williams Building

The Burroughs

Hendon

London NW4 4BT

Tel: +44 (0) 20 8411 2893

Email: L.Q.Liu@mdx.ac.uk

Mike O’Driscoll3

3Middlesex University

School of Health and Education

Room WG 17, Williams Building

The Burroughs

Hendon

London NW4 4BT

Email: m.odriscoll@mdx.ac.uk

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

Title page

THE EXTENT, VARIABILITY, AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS VOLUNTEERING AMONG

UNDERGRADUTE NURSING STUDENTS: IMPLICATIONS FOR PEDAGOGY IN NURSING

AND MIDIFERY EDUCATION.

Dyson, S.E, Liu, L and van den Akker, O

Corresponding author: Professor Sue Dyson

Professor Sue Dyson1

1Middlesex University

School of Health and Education

Room WG 17, Williams Building

The Burroughs

Hendon

London NW4 4BT

Tel: +44 (0) 20 8411 2887

Email: s.dyson@mdx.ac.uk

Dr Liang Liu2

2Middlesex University

School of Health and Education

Room WG 17, Williams Building

The Burroughs

Hendon

London NW4 4BT

Tel: +44 (0) 20 8411 2893

Email: L.Q.Liu@mdx.ac.uk

Mike O’Driscoll3

3Middlesex University

School of Health and Education

Room WG 17, Williams Building

The Burroughs

Hendon

London NW4 4BT

Email: m.odriscoll@mdx.ac.uk

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

Professor Olga B.A. van den Akker 4

4Middlesex University

School of Health and Education

Room WG 17, Williams Building

The Burroughs

Hendon

London NW4 4BT

Tel: :+44 (0)20 8411 6953

Email: o.vandenakker@mdx.ac.uk

Word Count: 5670

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

Professor Olga B.A. van den Akker 4

4Middlesex University

School of Health and Education

Room WG 17, Williams Building

The Burroughs

Hendon

London NW4 4BT

Tel: :+44 (0)20 8411 6953

Email: o.vandenakker@mdx.ac.uk

Word Count: 5670

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

1

INTRODUCTION

Nurses working within the National Health Service (NHS) require critical thinking skills in

order to cope with severely ill patients with complex care needs, to deal with rapidly

changing situations, and to do so with care with compassion. The Nursing and Midwifery

Council (NMC) expect undergraduate nursing programmes to prepare nurses to think

critically, while at the same time offering limited strategies for the educational development

of such skills (Banning, 2006). A lack of consensus around a definition of, and ways of

teaching critical thinking has resulted in a proliferation of strategies for the development of

critical thinking skills in nursing programmes, for example case studies (Popil, 2011),

reflective practice (Caldwell and Grobbel, 2013), and critical reading and writing (Heaslip,

2008). A less well understood strategy for the development of critical thinking in nursing is

student volunteering, despite the view that volunteering is thought to promote students’ self-

esteem and to enhance the development of critical thinking (Moore and Parker, 2008). While

self-esteem and critical thinking skills are synonymous with nursing and with volunteering,

literature concerned with volunteering in nursing programmes appears limited. The paucity of

literature may be due in part to programme requirements determined by the standards for pre-

registration nursing education (NMC, 2010), which leave limited time for the inclusion of

extracurricular activities. In light of this, our study aimed to understand the extent, variability

and attitudes towards volunteering among nursing students at our University. Our primary

research question was to establish the extent of volunteering in a subsection of the student

nurse population. Our secondary research question was to understand the attitudes of our

nursing students towards volunteering, in order that we might make recommendations for the

nursing curriculum.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

1

INTRODUCTION

Nurses working within the National Health Service (NHS) require critical thinking skills in

order to cope with severely ill patients with complex care needs, to deal with rapidly

changing situations, and to do so with care with compassion. The Nursing and Midwifery

Council (NMC) expect undergraduate nursing programmes to prepare nurses to think

critically, while at the same time offering limited strategies for the educational development

of such skills (Banning, 2006). A lack of consensus around a definition of, and ways of

teaching critical thinking has resulted in a proliferation of strategies for the development of

critical thinking skills in nursing programmes, for example case studies (Popil, 2011),

reflective practice (Caldwell and Grobbel, 2013), and critical reading and writing (Heaslip,

2008). A less well understood strategy for the development of critical thinking in nursing is

student volunteering, despite the view that volunteering is thought to promote students’ self-

esteem and to enhance the development of critical thinking (Moore and Parker, 2008). While

self-esteem and critical thinking skills are synonymous with nursing and with volunteering,

literature concerned with volunteering in nursing programmes appears limited. The paucity of

literature may be due in part to programme requirements determined by the standards for pre-

registration nursing education (NMC, 2010), which leave limited time for the inclusion of

extracurricular activities. In light of this, our study aimed to understand the extent, variability

and attitudes towards volunteering among nursing students at our University. Our primary

research question was to establish the extent of volunteering in a subsection of the student

nurse population. Our secondary research question was to understand the attitudes of our

nursing students towards volunteering, in order that we might make recommendations for the

nursing curriculum.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

2

BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE

Student Volunteering

Volunteering, in and of itself is considered a mutually beneficial relationship or exchange

rather than a gift, with considerable evidence of health and wellbeing benefits to those who

volunteer (Mundle et al, 2012). However, in spite of considerable evidence of benefit to

volunteers, measuring these benefits is a complex matter. Mundle et al (2012). argue that

generalisations made from the research around volunteering must be very cautious as most of

the studies have limitations, which would make establishing causal relationships or even

strong associations between good health and wellbeing outcomes and volunteering difficult.

There is also considerable evidence of benefits to those who ‘receive’ help from volunteers

and to the organisations that use volunteers. However, such benefits are hard to evaluate and

are highly dependent on context, such as the nature of the volunteering, the match between

the volunteer and the person receiving help or the training received by the volunteer.

The particular benefits of volunteering to nursing students centre on increasing the variety of

social groups or situations to which students are exposed, increasing self-confidence;

breaking down hierarchies, greater reflection on their own practice through doing (praxis),

the development of more critical perspectives and improvements in terms of meeting

particular competencies (Bell et al, 2014). The development of praxis and critical

perspectives as part of nurse education may be one way in which progress towards greater

compassion in nursing practice may be achieved, although research is needed to fully

appreciate the process by which this is achieved. Nevertheless, the absence of volunteering in

nursing pedagogy is a missed opportunity to harness the students’ knowledge and skills; both

pre-existing and underpinned by the nursing programme, for the benefit of recipients of

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

2

BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE

Student Volunteering

Volunteering, in and of itself is considered a mutually beneficial relationship or exchange

rather than a gift, with considerable evidence of health and wellbeing benefits to those who

volunteer (Mundle et al, 2012). However, in spite of considerable evidence of benefit to

volunteers, measuring these benefits is a complex matter. Mundle et al (2012). argue that

generalisations made from the research around volunteering must be very cautious as most of

the studies have limitations, which would make establishing causal relationships or even

strong associations between good health and wellbeing outcomes and volunteering difficult.

There is also considerable evidence of benefits to those who ‘receive’ help from volunteers

and to the organisations that use volunteers. However, such benefits are hard to evaluate and

are highly dependent on context, such as the nature of the volunteering, the match between

the volunteer and the person receiving help or the training received by the volunteer.

The particular benefits of volunteering to nursing students centre on increasing the variety of

social groups or situations to which students are exposed, increasing self-confidence;

breaking down hierarchies, greater reflection on their own practice through doing (praxis),

the development of more critical perspectives and improvements in terms of meeting

particular competencies (Bell et al, 2014). The development of praxis and critical

perspectives as part of nurse education may be one way in which progress towards greater

compassion in nursing practice may be achieved, although research is needed to fully

appreciate the process by which this is achieved. Nevertheless, the absence of volunteering in

nursing pedagogy is a missed opportunity to harness the students’ knowledge and skills; both

pre-existing and underpinned by the nursing programme, for the benefit of recipients of

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

3

health and social care services. While student volunteering may not automatically result in

learning, nor directly link to the development of caring and compassionate practice,

nonetheless volunteering does provide a way for students to make sense of their experiences

through opportunities intentionally designed to foster compassion for others and critical

thinking skills.

The Extent of Student Volunteering

The National Union of Students (NUS) report almost a third of students in higher education

(HE) devote a significant proportion of their spare time to volunteering activities, with an

average of 44 hours per year spent on volunteering (Mattey, 2014). While these figures

suggest students value the role of volunteering the evidence of any general benefit to health

for the volunteer and the recipient is largely anecdotal (Casiday et al, 2008), and for the most

part unproven (Holdsworth and Quinn, 2010). The assumption that students benefit from

volunteering, specifically in relation to skills development and employability supports

positive action by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to embed volunteering into

programmes. Embedding volunteering within academic programmes, for example through

provision of a volunteering module whereby students may develop skills and achieve credits

(Bell et al, 2014) may lead students to feel they have little choice but to take up a

volunteering activity in order not to be disadvantaged in a limited job market.

The core values of nursing; to make the care of people the first concern (GMC, 2012), while

not exclusive to nursing suggests student nurses are likely to exhibit values based motivators

for volunteering, for example supporting good causes, and helping others (Handy et al, 2010).

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

3

health and social care services. While student volunteering may not automatically result in

learning, nor directly link to the development of caring and compassionate practice,

nonetheless volunteering does provide a way for students to make sense of their experiences

through opportunities intentionally designed to foster compassion for others and critical

thinking skills.

The Extent of Student Volunteering

The National Union of Students (NUS) report almost a third of students in higher education

(HE) devote a significant proportion of their spare time to volunteering activities, with an

average of 44 hours per year spent on volunteering (Mattey, 2014). While these figures

suggest students value the role of volunteering the evidence of any general benefit to health

for the volunteer and the recipient is largely anecdotal (Casiday et al, 2008), and for the most

part unproven (Holdsworth and Quinn, 2010). The assumption that students benefit from

volunteering, specifically in relation to skills development and employability supports

positive action by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to embed volunteering into

programmes. Embedding volunteering within academic programmes, for example through

provision of a volunteering module whereby students may develop skills and achieve credits

(Bell et al, 2014) may lead students to feel they have little choice but to take up a

volunteering activity in order not to be disadvantaged in a limited job market.

The core values of nursing; to make the care of people the first concern (GMC, 2012), while

not exclusive to nursing suggests student nurses are likely to exhibit values based motivators

for volunteering, for example supporting good causes, and helping others (Handy et al, 2010).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

4

Utilitarian motivators, such as career enhancement and developing new skills are less likely

to be important for student nurses whose career choice has been made, and for whom specific

skills are embedded within approved undergraduate nursing programmes. Given the current

job market in healthcare where demand outstrips supply the usefulness of volunteering as a

means to build career contacts while training is questionable. Rather the benefits of

volunteering to nursing students are derived from the very nature of nursing itself, as a

socially engaged activity, whereby a concern for the ‘other` is central to all its endeavours

(Cipriano, 2007).

Care, Compassion and volunteering in the Nursing Curriculum

Since the publication of the Francis Report into failings at Mid Staffordshire Foundation

Hospital Trust in March 2013, it is unusual to hear health commentators talk about the NHS

without referring to “care and compassion”.. Care and compassion has become a figure of

speech, a sustained metaphor for discourse around health care, nursing and nurse education.

In the `post Francis` era “care and compassion” is a dominant discourse. Organisations with

a vested interest in health; NHS England, Health Education England (HEE) the Nursing and

Midwifery Council (NMC), and the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) take a

view on how “care and compassion” is taught in theory and how it is enacted in reality (NHS

England, 2012, DH, 2015, NMC 2015, HEE, 2015, HCPC, 2016). However, teaching “care

and compassion` to student nurses is not straightforward in spite of the edict in the Francis

Report for an increased focus on a culture of compassion at all levels in nurse education,

training and recruitment (Francis, 2013).

One approach for teaching care and compassion to nursing students is through provision of

opportunities for students to engage in a structured voluntary activity, which then becomes

the focus of a structured learning event where student and teacher reflect on the experience in

a safe environment (Buchen and Fertman, 1994). While generally under-researched as a

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

4

Utilitarian motivators, such as career enhancement and developing new skills are less likely

to be important for student nurses whose career choice has been made, and for whom specific

skills are embedded within approved undergraduate nursing programmes. Given the current

job market in healthcare where demand outstrips supply the usefulness of volunteering as a

means to build career contacts while training is questionable. Rather the benefits of

volunteering to nursing students are derived from the very nature of nursing itself, as a

socially engaged activity, whereby a concern for the ‘other` is central to all its endeavours

(Cipriano, 2007).

Care, Compassion and volunteering in the Nursing Curriculum

Since the publication of the Francis Report into failings at Mid Staffordshire Foundation

Hospital Trust in March 2013, it is unusual to hear health commentators talk about the NHS

without referring to “care and compassion”.. Care and compassion has become a figure of

speech, a sustained metaphor for discourse around health care, nursing and nurse education.

In the `post Francis` era “care and compassion” is a dominant discourse. Organisations with

a vested interest in health; NHS England, Health Education England (HEE) the Nursing and

Midwifery Council (NMC), and the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) take a

view on how “care and compassion” is taught in theory and how it is enacted in reality (NHS

England, 2012, DH, 2015, NMC 2015, HEE, 2015, HCPC, 2016). However, teaching “care

and compassion` to student nurses is not straightforward in spite of the edict in the Francis

Report for an increased focus on a culture of compassion at all levels in nurse education,

training and recruitment (Francis, 2013).

One approach for teaching care and compassion to nursing students is through provision of

opportunities for students to engage in a structured voluntary activity, which then becomes

the focus of a structured learning event where student and teacher reflect on the experience in

a safe environment (Buchen and Fertman, 1994). While generally under-researched as a

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

5

teaching strategy the available research suggests that volunteering is perceived as allowing

students to have more control over their learning, to gain experience in diverse environments,

break down stereotypes and developing critical perspectives. Bell et al (2014) describe a

partnership between De Montfort University and Macmillan Cancer Support whereby a

volunteering module (hosted within the Department of Nursing and Midwifery) was offered

to students in all faculties. It required 100 hours of volunteering over three years and the

completion of an academic assignment. The module included workshops and training

sessions which were jointly delivered by Macmillan and academic staff. Bell et al (2014)

report that the module was extremely popular and successful. Their analysis of nine

interviews with members of the module steering group highlight a wide range of benefits for

all stakeholders including meeting the aim of the university to contribute to the local

community and helping Macmillan to meet its aims of supporting people with cancer and

their families. The benefits to the students which were identified by the module steering

group included giving students the opportunity to take control of their learning and to

experience situations that would not be possible within traditional lecture based environment.

The benefits to the student are of volunteering for student nurses are seen partly in

educational or pedagogical terms (being in charge of their own learning and developing a

critical perspective) but also in terms of enhancing the potential for students to more fully

understand compassionate nursing practice and all that this entails in contemporary

healthcare contexts.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

5

teaching strategy the available research suggests that volunteering is perceived as allowing

students to have more control over their learning, to gain experience in diverse environments,

break down stereotypes and developing critical perspectives. Bell et al (2014) describe a

partnership between De Montfort University and Macmillan Cancer Support whereby a

volunteering module (hosted within the Department of Nursing and Midwifery) was offered

to students in all faculties. It required 100 hours of volunteering over three years and the

completion of an academic assignment. The module included workshops and training

sessions which were jointly delivered by Macmillan and academic staff. Bell et al (2014)

report that the module was extremely popular and successful. Their analysis of nine

interviews with members of the module steering group highlight a wide range of benefits for

all stakeholders including meeting the aim of the university to contribute to the local

community and helping Macmillan to meet its aims of supporting people with cancer and

their families. The benefits to the students which were identified by the module steering

group included giving students the opportunity to take control of their learning and to

experience situations that would not be possible within traditional lecture based environment.

The benefits to the student are of volunteering for student nurses are seen partly in

educational or pedagogical terms (being in charge of their own learning and developing a

critical perspective) but also in terms of enhancing the potential for students to more fully

understand compassionate nursing practice and all that this entails in contemporary

healthcare contexts.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

6

In light of a clear body of evidence around volunteering in the nursing curriculum we sought

to understand first, the extent and variability of volunteering among nursing students on our

undergraduate nursing programme, and second, the attitudes of our nursing students towards

volunteering, particularly as a structured activity within the nursing curriculum.

METHODOLOGY

Domain theory provided the theoretical framework for the study (Layder, 2006). In using

domain theory levels of social organization; self, situated activity, setting, and context are

given equal weight. Volunteering is a social activity, which involves the volunteer; an

individual with a social identity, being influenced by a situated activity. The activity may be

in an unfamiliar and challenging environment or setting, and in this case occurs within the

context or social organization of the university.

We used a mixed methods approach to research design. Focusing on mixing both quantitative

and qualitative approaches in combination provided a better understanding of the research

problem than could be understood by using one method. Our philosophical approach was

both pragmatic, practical, and enabled us to cross research paradigms in recognition that as a

team we are social, behavioral, and human sciences researchers first and foremost, and

dividing between quantitative and qualitative approaches only serves to narrow the

collaboration to the inquiry (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2006, p10). Using mixed methods

allowed for the research question to be addressed sequentially and pragmatically

(Denscombe, 2008). with attention paid to each component part. The survey instrument

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

6

In light of a clear body of evidence around volunteering in the nursing curriculum we sought

to understand first, the extent and variability of volunteering among nursing students on our

undergraduate nursing programme, and second, the attitudes of our nursing students towards

volunteering, particularly as a structured activity within the nursing curriculum.

METHODOLOGY

Domain theory provided the theoretical framework for the study (Layder, 2006). In using

domain theory levels of social organization; self, situated activity, setting, and context are

given equal weight. Volunteering is a social activity, which involves the volunteer; an

individual with a social identity, being influenced by a situated activity. The activity may be

in an unfamiliar and challenging environment or setting, and in this case occurs within the

context or social organization of the university.

We used a mixed methods approach to research design. Focusing on mixing both quantitative

and qualitative approaches in combination provided a better understanding of the research

problem than could be understood by using one method. Our philosophical approach was

both pragmatic, practical, and enabled us to cross research paradigms in recognition that as a

team we are social, behavioral, and human sciences researchers first and foremost, and

dividing between quantitative and qualitative approaches only serves to narrow the

collaboration to the inquiry (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2006, p10). Using mixed methods

allowed for the research question to be addressed sequentially and pragmatically

(Denscombe, 2008). with attention paid to each component part. The survey instrument

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

7

allowed for the collection of data concerned with extent and variability of student

volunteering in our study population, whereas the qualitative interviews captured data

concerned with attitudes towards volunteering among our students.

Methods

Student volunteering in nursing is defined in this paper as activities undertaken while

students are officially enrolled on undergraduate nursing programmes. While volunteering

activities may accrue credits in some programmes, in our study, volunteering is not an official

part of academic or practice learning.

The Survey

A 24-item self-report multiple-choice questionnaire was specifically developed, based on the

literature review, to ascertain the extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering, and

pre-tested with nursing academic staff before refining and finalising for distribution to the

students. The questionnaire comprised two parts; with part one containing 5 socio-

demographic questions, which asked students to identify the study programme being taken,

ethnic origin, age, gender and marital status. Part two contained 18 questions regarding

student’s volunteering experience, including past history of volunteering, current

volunteering status, volunteering since studying at university, barriers to uptake of

volunteering opportunities and attitudes towards volunteering. Questions required a `yes` or

`no` answer or a `tick all that apply` response. Opportunity to add additional responses was

provided through provision of free text boxes.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

7

allowed for the collection of data concerned with extent and variability of student

volunteering in our study population, whereas the qualitative interviews captured data

concerned with attitudes towards volunteering among our students.

Methods

Student volunteering in nursing is defined in this paper as activities undertaken while

students are officially enrolled on undergraduate nursing programmes. While volunteering

activities may accrue credits in some programmes, in our study, volunteering is not an official

part of academic or practice learning.

The Survey

A 24-item self-report multiple-choice questionnaire was specifically developed, based on the

literature review, to ascertain the extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering, and

pre-tested with nursing academic staff before refining and finalising for distribution to the

students. The questionnaire comprised two parts; with part one containing 5 socio-

demographic questions, which asked students to identify the study programme being taken,

ethnic origin, age, gender and marital status. Part two contained 18 questions regarding

student’s volunteering experience, including past history of volunteering, current

volunteering status, volunteering since studying at university, barriers to uptake of

volunteering opportunities and attitudes towards volunteering. Questions required a `yes` or

`no` answer or a `tick all that apply` response. Opportunity to add additional responses was

provided through provision of free text boxes.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

8

The study was approved by the University research ethics committee. Permission to distribute

the survey questionnaires was received from programme leaders for each cohort of the three-

year course. Participant consent was assumed upon return of the completed questionnaire. All

participants were recruited during lectures delivered between March 2013 and September

2014, as this ensured students were representative of all three years of the undergraduate

nursing degree programme. Survey responses were entered into Excel (MS 2007 version).

Descriptive statistics were then calculated using SPSS version 19 for Windows (IBM SPSS

statistics 19). Values were reported as number and percentage unless otherwise noted. The

survey results were used to develop an interview schedule for use in semi-structured

interviews focused on experiences and thoughts about volunteering. Storage of data

conformed to ethical requirements of the University.

The Interview

Following the quantitative part of the study, the research team contacted fourteen students

who had indicated a willingness to be interviewed by including their email addresses on

returned questionnaires. Ten students out of 14 who were approached agreed to participate.

These students were invited for interview on campus, provided with a detailed information

sheet about the research, and duly consented into the study. All interviews took place over a

four month period; April to July 2015. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data were analyzed using a general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006), which is specifically

designed to (1) condense extensive and varied raw text data into a readable summary format,

(2) to establish clear links between the research objectives and the summary findings derived

from the raw data and (3) to develop a model or theory about the underlying structures of

experiences or processes which are evident in the raw data. All participants who were

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

8

The study was approved by the University research ethics committee. Permission to distribute

the survey questionnaires was received from programme leaders for each cohort of the three-

year course. Participant consent was assumed upon return of the completed questionnaire. All

participants were recruited during lectures delivered between March 2013 and September

2014, as this ensured students were representative of all three years of the undergraduate

nursing degree programme. Survey responses were entered into Excel (MS 2007 version).

Descriptive statistics were then calculated using SPSS version 19 for Windows (IBM SPSS

statistics 19). Values were reported as number and percentage unless otherwise noted. The

survey results were used to develop an interview schedule for use in semi-structured

interviews focused on experiences and thoughts about volunteering. Storage of data

conformed to ethical requirements of the University.

The Interview

Following the quantitative part of the study, the research team contacted fourteen students

who had indicated a willingness to be interviewed by including their email addresses on

returned questionnaires. Ten students out of 14 who were approached agreed to participate.

These students were invited for interview on campus, provided with a detailed information

sheet about the research, and duly consented into the study. All interviews took place over a

four month period; April to July 2015. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data were analyzed using a general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006), which is specifically

designed to (1) condense extensive and varied raw text data into a readable summary format,

(2) to establish clear links between the research objectives and the summary findings derived

from the raw data and (3) to develop a model or theory about the underlying structures of

experiences or processes which are evident in the raw data. All participants who were

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

9

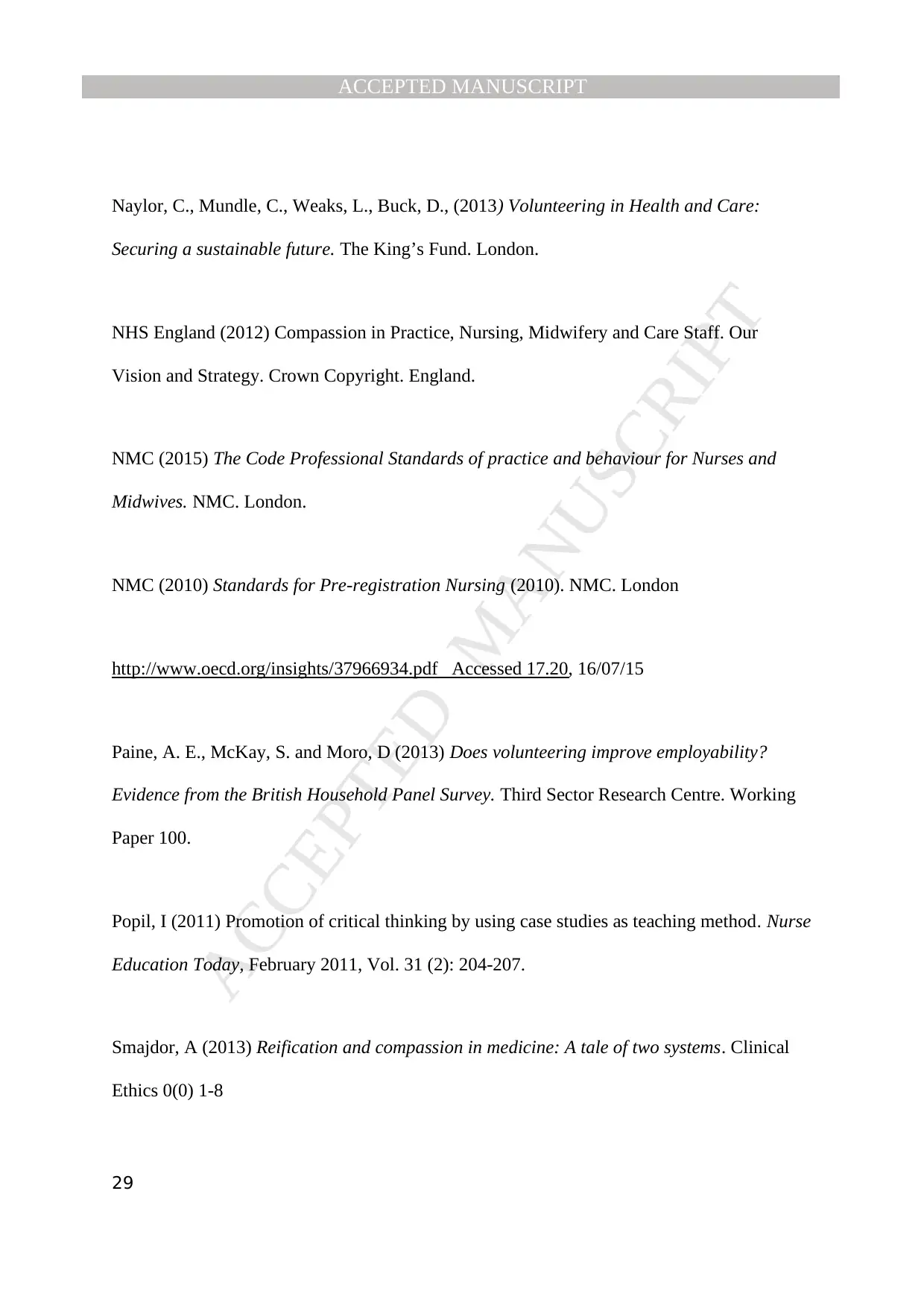

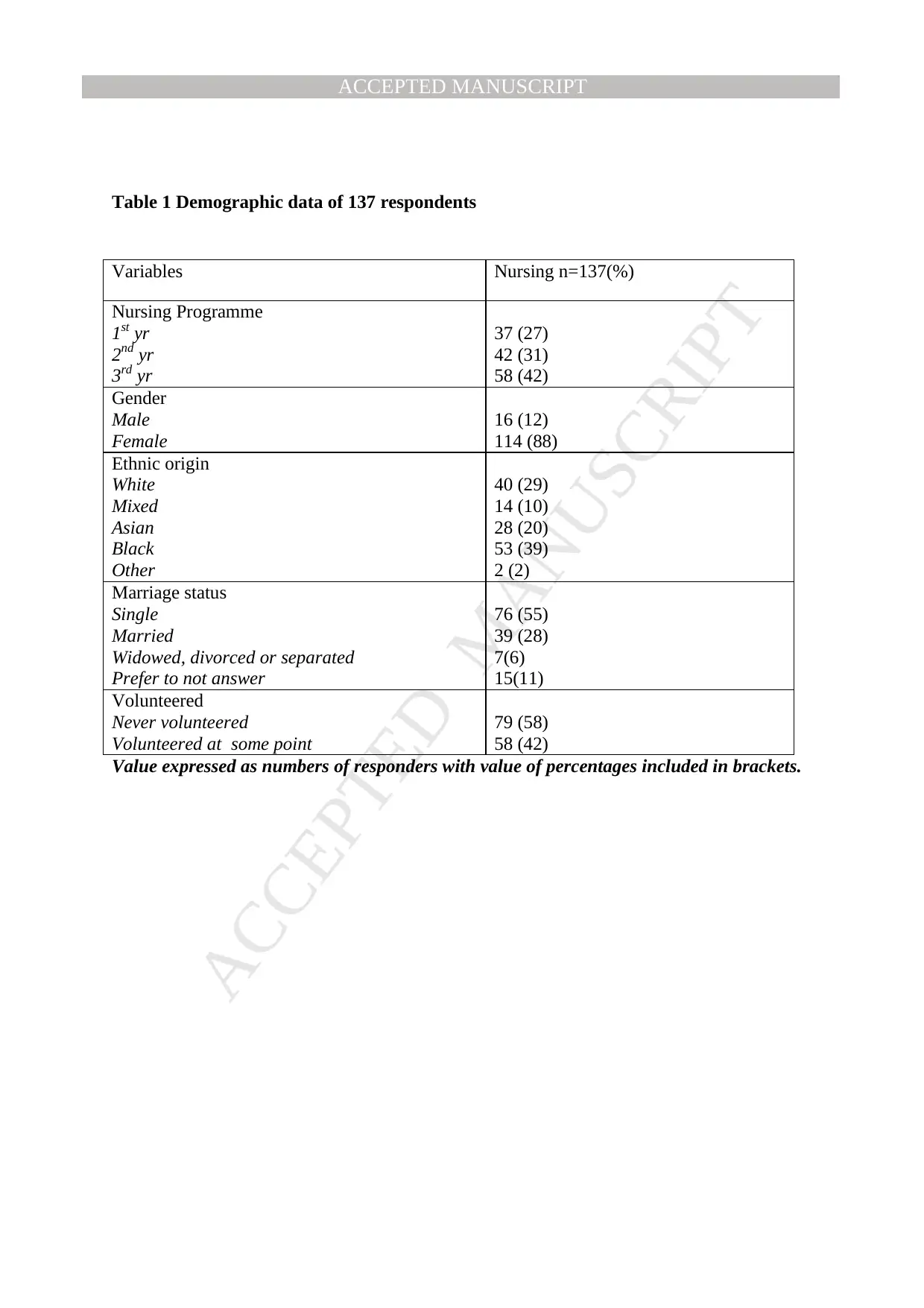

interviewed were given a number to protect anonymity. Table 1 shows demographic data of

respondents.

Table 1 here

SURVEY RESULTS

One hundred and thirty seven (137) of the 250 eligible nursing students completed the

survey, resulting in a 65% response rate. Table 1 shows their sociodemographic details. The

ethnic mix of students is consistent with the study body of the institution where the research

was carried out (23% overseas, 16% outside the EU). Eighty eight percent of respondents

were female, which is reflective of overall trends, whereby a higher proportion of females to

males enter subjects allied to medicine (including nursing) (HESA 2010/11).

Seventy- nine respondents (58%) reported never having volunteered before, while 58 (42%)

respondents reported having volunteered at some point. Twelve (12) of the 58, who had

volunteered, had done so since joining the University, however, only 7 of the 12 students who

had volunteered since becoming University students were currently volunteering at the time

of our study.

Figure 1 here

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

9

interviewed were given a number to protect anonymity. Table 1 shows demographic data of

respondents.

Table 1 here

SURVEY RESULTS

One hundred and thirty seven (137) of the 250 eligible nursing students completed the

survey, resulting in a 65% response rate. Table 1 shows their sociodemographic details. The

ethnic mix of students is consistent with the study body of the institution where the research

was carried out (23% overseas, 16% outside the EU). Eighty eight percent of respondents

were female, which is reflective of overall trends, whereby a higher proportion of females to

males enter subjects allied to medicine (including nursing) (HESA 2010/11).

Seventy- nine respondents (58%) reported never having volunteered before, while 58 (42%)

respondents reported having volunteered at some point. Twelve (12) of the 58, who had

volunteered, had done so since joining the University, however, only 7 of the 12 students who

had volunteered since becoming University students were currently volunteering at the time

of our study.

Figure 1 here

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

10

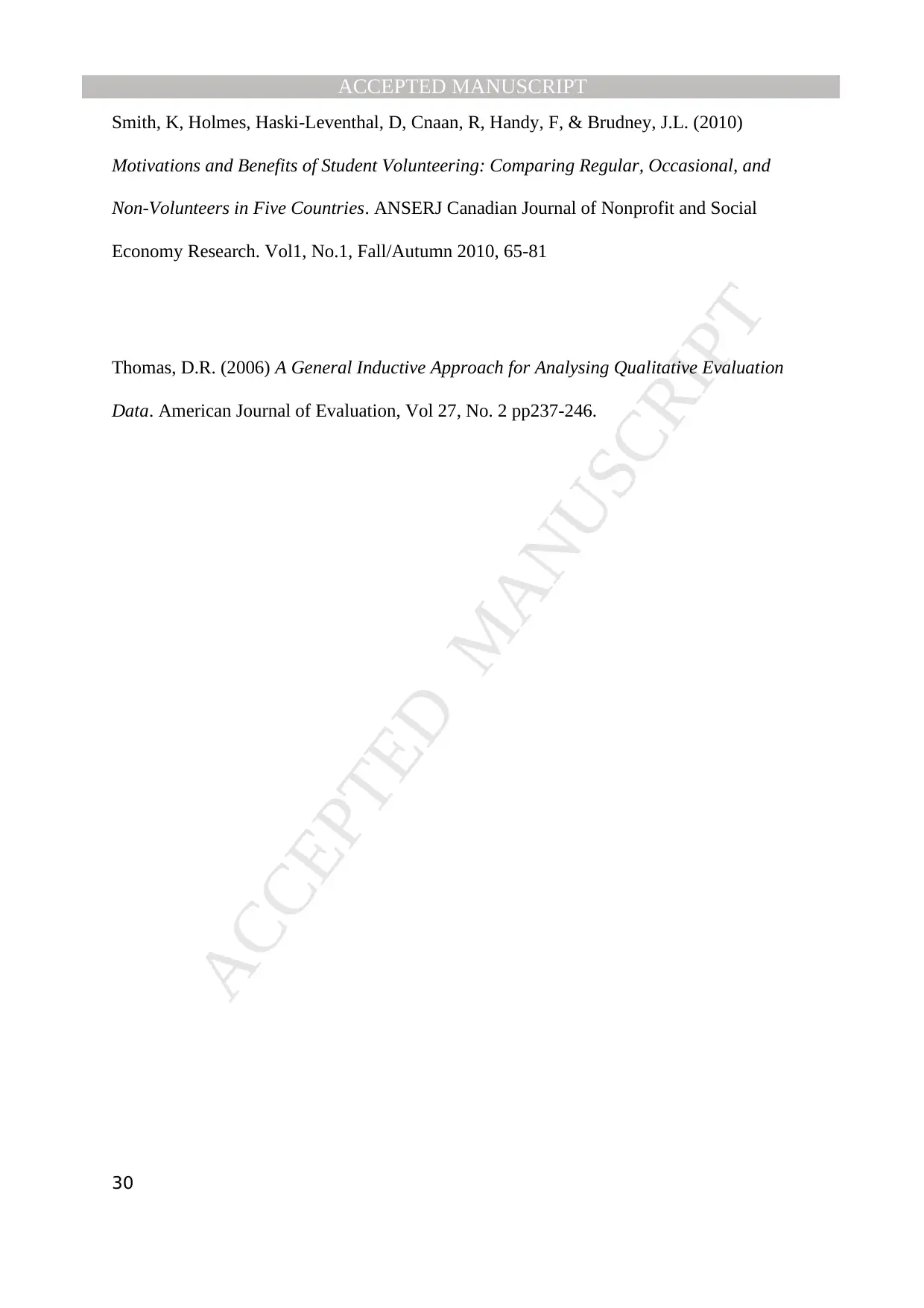

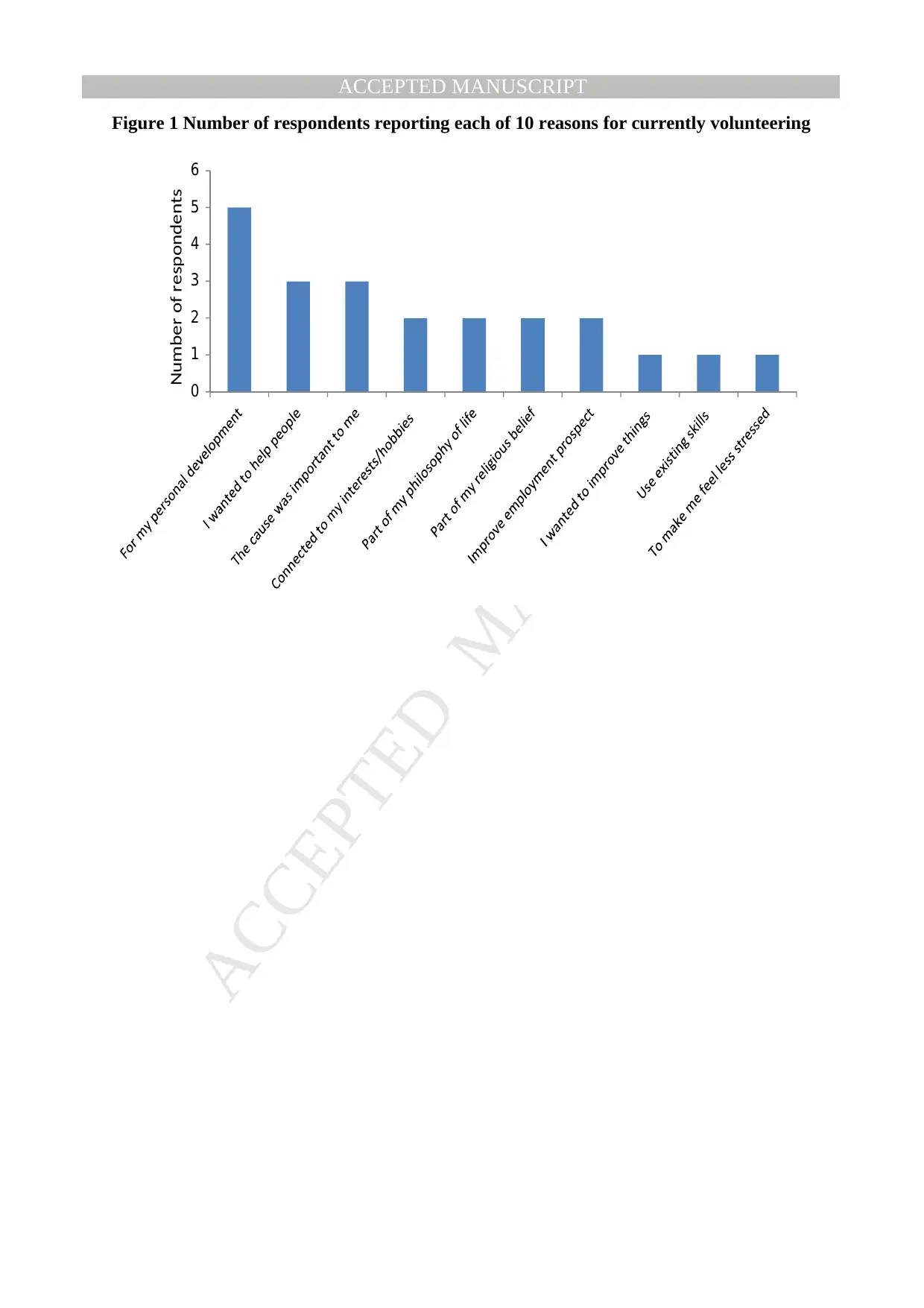

Only 7 of the 137 respondents in our survey were volunteering at the time of our study. We

asked these respondents i.e. those currently volunteering to indicate as many reasons for

volunteering as applied from a pre-determined list, with a free text box provided for

additional responses. Figure 1 shows 10 reasons for volunteering since becoming a university

student.

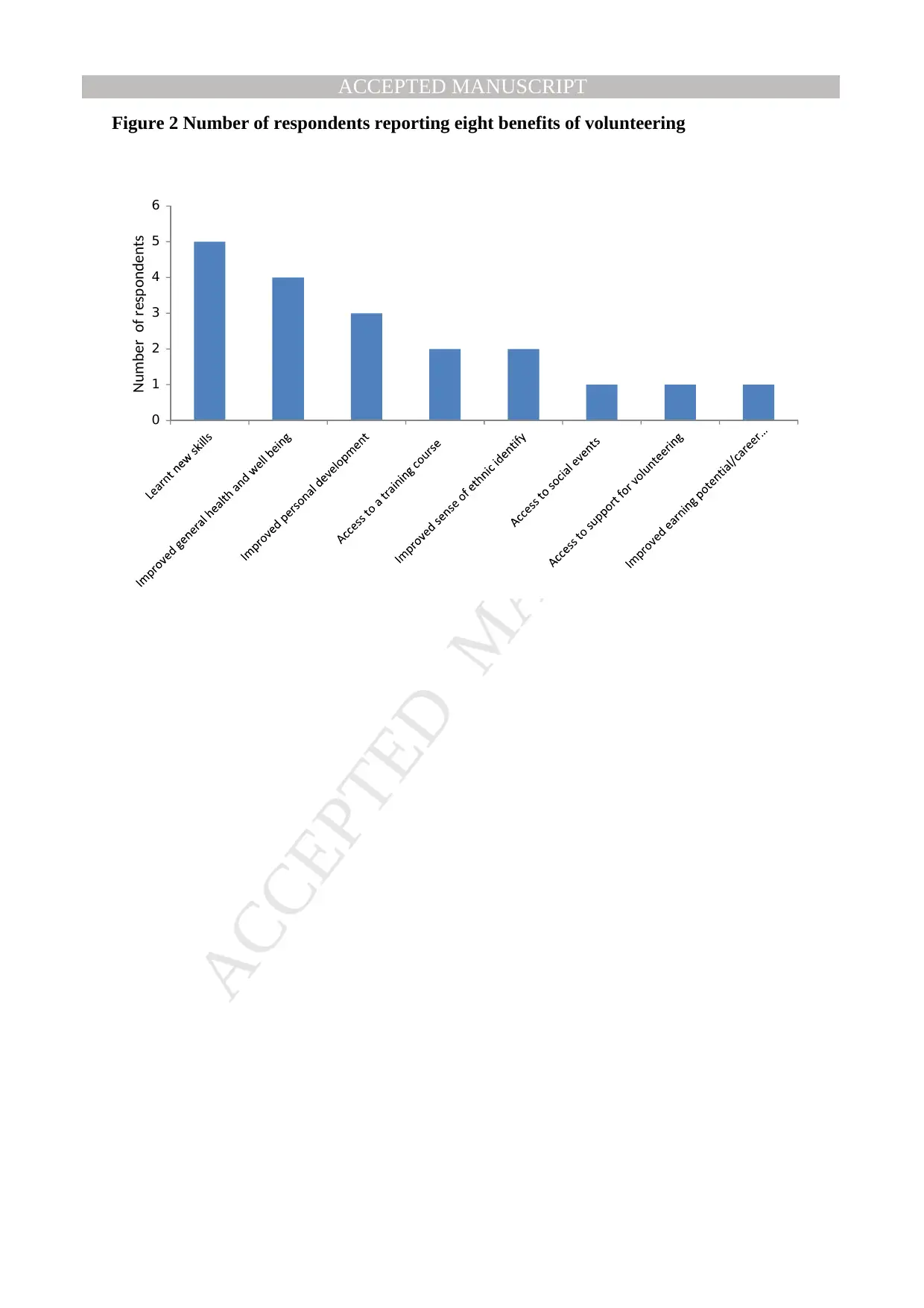

Figure 2 here

We asked respondents who were currently volunteering what had been gained or achieved i.e.

the benefits of volunteering from a pre-determined list, with a free text box for additional

responses. Figure 2 shows numbers of respondents identifying eight benefits to volunteering.

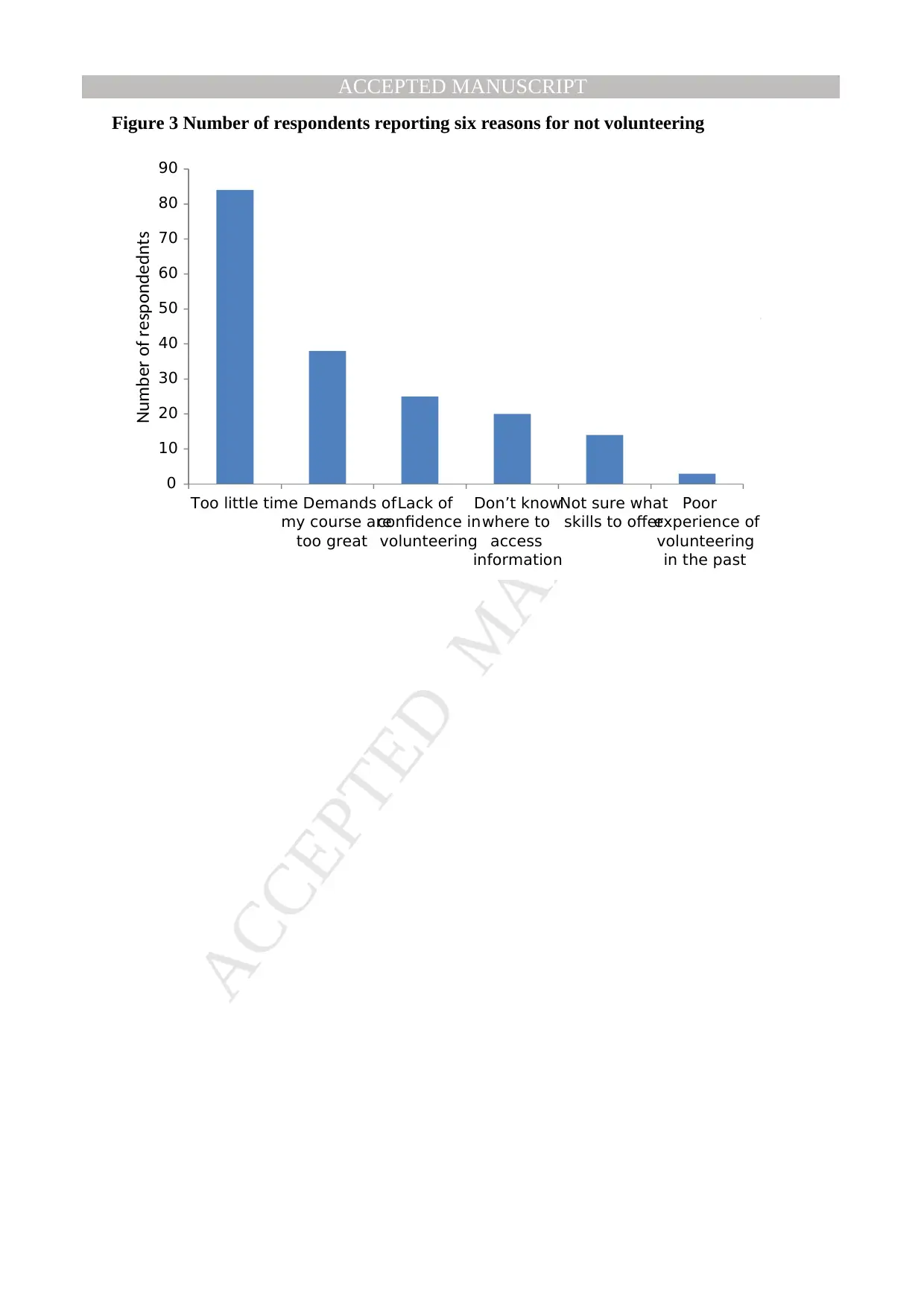

Figure 3 here

Six main reasons were expressed by respondents as reasons for not volunteering, including

too little time, lack of access to information on volunteering opportunities, lack of confidence

in volunteering, uncertainty around what skills to offer, and a previously poor experience of

volunteering. The demands of the nursing programme were reported to impact uptake of

volunteering while studying the undergraduate nursing programme. In total, 85 (62%)

respondents would definitely consider volunteering in the future, 3 (2%) respondents said

they might consider volunteering in the future, while 26 (19%) respondents would not

consider volunteering in the future.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

10

Only 7 of the 137 respondents in our survey were volunteering at the time of our study. We

asked these respondents i.e. those currently volunteering to indicate as many reasons for

volunteering as applied from a pre-determined list, with a free text box provided for

additional responses. Figure 1 shows 10 reasons for volunteering since becoming a university

student.

Figure 2 here

We asked respondents who were currently volunteering what had been gained or achieved i.e.

the benefits of volunteering from a pre-determined list, with a free text box for additional

responses. Figure 2 shows numbers of respondents identifying eight benefits to volunteering.

Figure 3 here

Six main reasons were expressed by respondents as reasons for not volunteering, including

too little time, lack of access to information on volunteering opportunities, lack of confidence

in volunteering, uncertainty around what skills to offer, and a previously poor experience of

volunteering. The demands of the nursing programme were reported to impact uptake of

volunteering while studying the undergraduate nursing programme. In total, 85 (62%)

respondents would definitely consider volunteering in the future, 3 (2%) respondents said

they might consider volunteering in the future, while 26 (19%) respondents would not

consider volunteering in the future.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

11

The results of our survey show few nursing students volunteer after coming to study at

university, irrespective of whether they have volunteered beforehand. The small number of

students who reported volunteering identified personal and societal benefits of doing so. The

demands of the nursing programme and the financial burden of studying at university

appeared to mitigate uptake of volunteering activities.

INTERVIEW FINDINGS

Ten students responded to efforts to contact them via email, and were subsequently

interviewed. Of these ten, two students had volunteered before studying at University.

However, none of the students we interviewed were currently volunteering. Students were

asked to talk about specifically about volunteering within the following themes (1) time to

volunteer, (2) accessing volunteering opportunities, (3) confidence to volunteer, and (4)

volunteering and studying, as these were the main themes arising from survey data. In

addition, students were provided the opportunity to talk freely around any aspect of

volunteering. A condensed summary of the raw text interview data are presented below:

Time to Volunteer

The benefits to students from volunteering are well recognized (Smith et al, 2010). However,

students in our study discussed having little time for extracurricular activities, with

programme requirements appearing to take priority. Supplementary programme content, for

example dissertation and maths workshops, were perceived by students to add value to the

nursing programme. Consequently students were prepared to invest time to attend these

workshops, as opposed to investing valuable time in volunteering.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

11

The results of our survey show few nursing students volunteer after coming to study at

university, irrespective of whether they have volunteered beforehand. The small number of

students who reported volunteering identified personal and societal benefits of doing so. The

demands of the nursing programme and the financial burden of studying at university

appeared to mitigate uptake of volunteering activities.

INTERVIEW FINDINGS

Ten students responded to efforts to contact them via email, and were subsequently

interviewed. Of these ten, two students had volunteered before studying at University.

However, none of the students we interviewed were currently volunteering. Students were

asked to talk about specifically about volunteering within the following themes (1) time to

volunteer, (2) accessing volunteering opportunities, (3) confidence to volunteer, and (4)

volunteering and studying, as these were the main themes arising from survey data. In

addition, students were provided the opportunity to talk freely around any aspect of

volunteering. A condensed summary of the raw text interview data are presented below:

Time to Volunteer

The benefits to students from volunteering are well recognized (Smith et al, 2010). However,

students in our study discussed having little time for extracurricular activities, with

programme requirements appearing to take priority. Supplementary programme content, for

example dissertation and maths workshops, were perceived by students to add value to the

nursing programme. Consequently students were prepared to invest time to attend these

workshops, as opposed to investing valuable time in volunteering.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

12

“We have exams that you need the extra time for, but there’s everything else as well,

like I went to a lot of extra lessons like dissertation workshops this year. And in the

first year I went to the maths workshops, so I think the extra work I think would be

first if I had time. And then second, maybe volunteering but then, yeah, I’d probably

say volunteering if I had any spare time” (student 8, non-volunteer)

Our study drew on relatively small numbers of students, nevertheless time does appear to

be a factor in preventing students from volunteering while studying. Studies were seen as

a priority, including writing assignments and revising for exams. When asked whether a

more flexible curriculum might `free up` time, students did not necessarily prioritise

volunteering;

“Then it would probably be work after studying. I’d have to look at it because I need

to work long term as well”. (student 1, non-volunteer)

Accessing Volunteering Opportunities

Access to volunteering opportunities is key in influencing individual choice to volunteer

(McBride and Lough, 2010). While access to information may not increase the likelihood

for an `unmotivated` student to take up a volunteering opportunity, nevertheless

motivation to volunteer has been linked with previous volunteering experience including

ready access to information, volunteering programmes and support (Jones and Hill, 2003).

Students in our study reported having limited access to volunteering information and

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

12

“We have exams that you need the extra time for, but there’s everything else as well,

like I went to a lot of extra lessons like dissertation workshops this year. And in the

first year I went to the maths workshops, so I think the extra work I think would be

first if I had time. And then second, maybe volunteering but then, yeah, I’d probably

say volunteering if I had any spare time” (student 8, non-volunteer)

Our study drew on relatively small numbers of students, nevertheless time does appear to

be a factor in preventing students from volunteering while studying. Studies were seen as

a priority, including writing assignments and revising for exams. When asked whether a

more flexible curriculum might `free up` time, students did not necessarily prioritise

volunteering;

“Then it would probably be work after studying. I’d have to look at it because I need

to work long term as well”. (student 1, non-volunteer)

Accessing Volunteering Opportunities

Access to volunteering opportunities is key in influencing individual choice to volunteer

(McBride and Lough, 2010). While access to information may not increase the likelihood

for an `unmotivated` student to take up a volunteering opportunity, nevertheless

motivation to volunteer has been linked with previous volunteering experience including

ready access to information, volunteering programmes and support (Jones and Hill, 2003).

Students in our study reported having limited access to volunteering information and

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

13

opportunity. `Fresher’s Week`, which provides students with essential information and

guidance on what to expect while at university would appear to be uniquely placed to

include information about volunteering opportunities.

“I know it didn’t really have a fresher’s event then, it was just like in the sports hall

there were some tables with books on but there wasn’t anything about volunteering. I

remember speaking to the lecturer, because she was leaving and everyone was like,

why are you leaving? She spoke about it, she was going abroad to do some

volunteering work”. (student 8, non-volunteer

`Fresher’s Week` was devoted to information about sports activities, university clubs and

societies, which arguably reflects the University’s priorities. While students were able to

access information about volunteering, this appeared ad hoc and opportunistic, thus

requiring students to have prior experience of volunteering and/or a predetermined level

of motivation to volunteer.

Confidence to Volunteer

Volunteering is thought to build self-esteem, self-confidence, and an opportunity to refocus

attention away from personal difficulties, while at the same time providing opportunities to

learn new skills and gain experience, not readily accessible in the course of everyday life and

work (Agathangelou, 2015). However, students in our study perceived a level of skill to be

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

13

opportunity. `Fresher’s Week`, which provides students with essential information and

guidance on what to expect while at university would appear to be uniquely placed to

include information about volunteering opportunities.

“I know it didn’t really have a fresher’s event then, it was just like in the sports hall

there were some tables with books on but there wasn’t anything about volunteering. I

remember speaking to the lecturer, because she was leaving and everyone was like,

why are you leaving? She spoke about it, she was going abroad to do some

volunteering work”. (student 8, non-volunteer

`Fresher’s Week` was devoted to information about sports activities, university clubs and

societies, which arguably reflects the University’s priorities. While students were able to

access information about volunteering, this appeared ad hoc and opportunistic, thus

requiring students to have prior experience of volunteering and/or a predetermined level

of motivation to volunteer.

Confidence to Volunteer

Volunteering is thought to build self-esteem, self-confidence, and an opportunity to refocus

attention away from personal difficulties, while at the same time providing opportunities to

learn new skills and gain experience, not readily accessible in the course of everyday life and

work (Agathangelou, 2015). However, students in our study perceived a level of skill to be

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

14

required in order to volunteer effectively, or at least some association or affinity with the

recipient of the voluntary activity and/or some understanding of their needs;

“I lost my flat in 1998 and then obviously I moved into a YMCA and it was an

opportunity so I volunteered with the YMCA and it was going out helping the

homeless, feeding the homeless and just offering like just someone to chat to. And

when this came along there was just like a lot of people that were all in the same

situation as me” (student 4 non-volunteer, had previously volunteered)

For this student, the ability to `climb into his skin and walk around in it` (Harper Lee, 1960)

enabled an otherwise reticent and reserved individual to offer support to someone in a

situation he could empathise with. The structured nature of the volunteering opportunity may

have assisted uptake of an activity, which this student might otherwise have foregone.

For another student it appeared important that any voluntary activity was in some way

relevant and reflective of his or her self-worth in terms of what they had to offer the other

person;

“It builds up experience in whatever you’re doing, and also socialising with other

people as well. So it’s building good relationships for what you’re going into, so I

think it’s good, beneficial, for personal development and also I think it’s sort of equal,

as well. Just help to, whatever you volunteer really, you just want sometimes to help”

(student 7 non-volunteer, previous volunteer)

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

14

required in order to volunteer effectively, or at least some association or affinity with the

recipient of the voluntary activity and/or some understanding of their needs;

“I lost my flat in 1998 and then obviously I moved into a YMCA and it was an

opportunity so I volunteered with the YMCA and it was going out helping the

homeless, feeding the homeless and just offering like just someone to chat to. And

when this came along there was just like a lot of people that were all in the same

situation as me” (student 4 non-volunteer, had previously volunteered)

For this student, the ability to `climb into his skin and walk around in it` (Harper Lee, 1960)

enabled an otherwise reticent and reserved individual to offer support to someone in a

situation he could empathise with. The structured nature of the volunteering opportunity may

have assisted uptake of an activity, which this student might otherwise have foregone.

For another student it appeared important that any voluntary activity was in some way

relevant and reflective of his or her self-worth in terms of what they had to offer the other

person;

“It builds up experience in whatever you’re doing, and also socialising with other

people as well. So it’s building good relationships for what you’re going into, so I

think it’s good, beneficial, for personal development and also I think it’s sort of equal,

as well. Just help to, whatever you volunteer really, you just want sometimes to help”

(student 7 non-volunteer, previous volunteer)

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

15

Volunteering and Studying

From the responses students gave about volunteering while studying at university some

insight is provided into how nursing courses variously support or prevent uptake of

volunteering. Nursing programmes in the UK are equally weighted in terms of the ratio of

theory to practice. Modules are usually delivered over 3 semesters or terms, in order to

facilitate the 4,600 programme hours required by the NMC. In reality, this means nursing

students follow a calendar dissimilar to other university courses, with modules running

throughout the academic year. Little time is left for students to engage in extracurricular

activities without self-determination, motivation, human and social capital;

“We’re just really busy on the programme at the moment. I usually do the bank shift,

but I haven’t done that for several months because its time pressure at the moment”

(student1 non-volunteer)

“I have looked at one recently. It’s called the (name) Soup Kitchen, it’s a guy who did

the same thing I did went out to the homeless. I think if I could do that alongside my

nursing I would but it all depends on time again”.(student 4 non-volunteer, previous

volunteer)

DISCUSSION

Extent of Student Volunteering

Volunteering amongst students has a long and sometimes radical history (Brewis 2010). It is

only recently that academics and politicians have come to regard student volunteering as

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

15

Volunteering and Studying

From the responses students gave about volunteering while studying at university some

insight is provided into how nursing courses variously support or prevent uptake of

volunteering. Nursing programmes in the UK are equally weighted in terms of the ratio of

theory to practice. Modules are usually delivered over 3 semesters or terms, in order to

facilitate the 4,600 programme hours required by the NMC. In reality, this means nursing

students follow a calendar dissimilar to other university courses, with modules running

throughout the academic year. Little time is left for students to engage in extracurricular

activities without self-determination, motivation, human and social capital;

“We’re just really busy on the programme at the moment. I usually do the bank shift,

but I haven’t done that for several months because its time pressure at the moment”

(student1 non-volunteer)

“I have looked at one recently. It’s called the (name) Soup Kitchen, it’s a guy who did

the same thing I did went out to the homeless. I think if I could do that alongside my

nursing I would but it all depends on time again”.(student 4 non-volunteer, previous

volunteer)

DISCUSSION

Extent of Student Volunteering

Volunteering amongst students has a long and sometimes radical history (Brewis 2010). It is

only recently that academics and politicians have come to regard student volunteering as

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

16

something that is beneficial for all involved.(Holdsworth and Quinn 2010; Darwen and

Rannard 2011). Estimated rates of student volunteering vary widely but one of the most

reliable sources, the National Union of Students finds that 31% of students had engaged in

formal or informal volunteering in the year prior to the survey, for an average of 44 hours.

30% of these student volunteers said that they had participated in volunteering which was to

do with ‘’visiting people / providing care or support’’ and 40% of all students said that they

would be encouraged to do more volunteering if their institution could link it to their course

or academic qualification (NUS, 2014). The results of our study indicate that most of the

small minority of nursing students who had volunteered had done so before coming to study

at university. This is important since much has been written about the benefits to students of

volunteering (Smith et al, 2010, Haski-Leventhal, 2008. Evans and Saxton, 2005), including

the opportunity to gain work-related experience, to learn new skills, to improve job

opportunities, and to improve outcomes or impacts for communities, education institutions,

employers, and for the students themselves (Smith et al, 2010).

Variability in Student Volunteering

There is little evidence on the frequency of volunteering by nursing students or the types of

volunteering which they do. In our survey of undergraduate nursing students (at one English

university) amongst the 137 who responded to the survey, 42% (n=58) had volunteered at

some point in the past. 20.6% of those who had volunteered in the past (n=12) had

volunteered since starting university (12%) of those who had ever volunteered (n=7) were

doing so currently. To look at it another way, just 5.1% of all respondents to the survey

(7/137) were currently active volunteers which could be contrasted (tentatively) with the rate

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

16

something that is beneficial for all involved.(Holdsworth and Quinn 2010; Darwen and

Rannard 2011). Estimated rates of student volunteering vary widely but one of the most

reliable sources, the National Union of Students finds that 31% of students had engaged in

formal or informal volunteering in the year prior to the survey, for an average of 44 hours.

30% of these student volunteers said that they had participated in volunteering which was to

do with ‘’visiting people / providing care or support’’ and 40% of all students said that they

would be encouraged to do more volunteering if their institution could link it to their course

or academic qualification (NUS, 2014). The results of our study indicate that most of the

small minority of nursing students who had volunteered had done so before coming to study

at university. This is important since much has been written about the benefits to students of

volunteering (Smith et al, 2010, Haski-Leventhal, 2008. Evans and Saxton, 2005), including

the opportunity to gain work-related experience, to learn new skills, to improve job

opportunities, and to improve outcomes or impacts for communities, education institutions,

employers, and for the students themselves (Smith et al, 2010).

Variability in Student Volunteering

There is little evidence on the frequency of volunteering by nursing students or the types of

volunteering which they do. In our survey of undergraduate nursing students (at one English

university) amongst the 137 who responded to the survey, 42% (n=58) had volunteered at

some point in the past. 20.6% of those who had volunteered in the past (n=12) had

volunteered since starting university (12%) of those who had ever volunteered (n=7) were

doing so currently. To look at it another way, just 5.1% of all respondents to the survey

(7/137) were currently active volunteers which could be contrasted (tentatively) with the rate

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

17

of student volunteering found by NUS (2014) which, at 31%, is around six times higher. In

view of the lack of evidence about patterns of volunteering amongst student nurses, clearly

the results are very important and useful. Given the high response rate it seems likely that the

findings are valid in relation to the Higher Education Institution (HEI) studied but obviously

a larger survey across a sample of HEIs would be needed to assess the generalisability of the

findings and to clearly establish whether patterns of volunteering amongst nursing students

are different to those of other students.

Attitudes Towards Volunteering

Motivations for volunteering are a complex mixture of altruism and self–. Holdsworth and

Quinn (2010) refer to the ‘economy of experience’ where volunteering or paid placements

may increasingly be seen by students as necessary additions to qualifications, in order to gain

advantage in the jobs market. However, they recognise that student motivations for

volunteering are likely to be much more complex than this. NUS (2014) find that the top five

motivations to volunteer amongst current student volunteers include: ‘improving

things/helping people’; ‘gaining work experience/developing their CV’; ‘personal values’ and

‘developing skills/meeting new people/making friends’ In our survey, the most important

reasons cited by nursing students were personal development, wanting to help people and

volunteering for an important cause. These findings suggest nursing students’ motivations for

volunteering are less likely to relate to enhanced employment prospects since demand for

nurses far outstrips supply.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

17

of student volunteering found by NUS (2014) which, at 31%, is around six times higher. In

view of the lack of evidence about patterns of volunteering amongst student nurses, clearly

the results are very important and useful. Given the high response rate it seems likely that the

findings are valid in relation to the Higher Education Institution (HEI) studied but obviously

a larger survey across a sample of HEIs would be needed to assess the generalisability of the

findings and to clearly establish whether patterns of volunteering amongst nursing students

are different to those of other students.

Attitudes Towards Volunteering

Motivations for volunteering are a complex mixture of altruism and self–. Holdsworth and

Quinn (2010) refer to the ‘economy of experience’ where volunteering or paid placements

may increasingly be seen by students as necessary additions to qualifications, in order to gain

advantage in the jobs market. However, they recognise that student motivations for

volunteering are likely to be much more complex than this. NUS (2014) find that the top five

motivations to volunteer amongst current student volunteers include: ‘improving

things/helping people’; ‘gaining work experience/developing their CV’; ‘personal values’ and

‘developing skills/meeting new people/making friends’ In our survey, the most important

reasons cited by nursing students were personal development, wanting to help people and

volunteering for an important cause. These findings suggest nursing students’ motivations for

volunteering are less likely to relate to enhanced employment prospects since demand for

nurses far outstrips supply.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

18

Time to Volunteer

Time appeared a significant factor in whether or not our students were volunteering,

irrespective of overall attitudes towards volunteering. Students in our study exhibited a high

work ethic in relation to fulfilling the requirements of the nursing programme, as this would

ultimately ensure their future in terms of employment opportunities and the ability to `pay off

student debt`. The same degree of work ethic did not translate into an engagement with

volunteering activities. One reason might be people are generally poorly socialised into

giving their time, such that an overwhelmingly high work ethic usually sees priority given to

economically rewarding activities over voluntary work (Calleja, 2012). An apparent

contradiction exists in that while students in our study clearly identified the positive benefits

of volunteering, nevertheless, priority was given over to completing the programme in order

to take up paid nursing work. This disconnect between the nursing programme and nursing in

the `real world` suggests while students recognize the contribution volunteering can make to

personal development, they do not appear to fully appreciate how volunteering impacts

learning about nursing. The need to complete all required elements of the nursing course

prevented students from making connections between nursing as a course of study and

nursing as a social enterprise.

Benefits of Volunteering for Nursing Students

The main benefits of volunteering cited by respondents in our survey were learning new

skills, improving general health and wellbeing, and improved personal development. This

finding is significant in that the health benefits to volunteers and recipients are largely

anecdotal (Cassidy et al 2008; Holdsworth & Quinn 2010). Bell et. al 2014 make reference to

the tendency to assume that volunteering is beneficial without citing specific evidence.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

18

Time to Volunteer

Time appeared a significant factor in whether or not our students were volunteering,

irrespective of overall attitudes towards volunteering. Students in our study exhibited a high

work ethic in relation to fulfilling the requirements of the nursing programme, as this would

ultimately ensure their future in terms of employment opportunities and the ability to `pay off

student debt`. The same degree of work ethic did not translate into an engagement with

volunteering activities. One reason might be people are generally poorly socialised into

giving their time, such that an overwhelmingly high work ethic usually sees priority given to

economically rewarding activities over voluntary work (Calleja, 2012). An apparent

contradiction exists in that while students in our study clearly identified the positive benefits

of volunteering, nevertheless, priority was given over to completing the programme in order

to take up paid nursing work. This disconnect between the nursing programme and nursing in

the `real world` suggests while students recognize the contribution volunteering can make to

personal development, they do not appear to fully appreciate how volunteering impacts

learning about nursing. The need to complete all required elements of the nursing course

prevented students from making connections between nursing as a course of study and

nursing as a social enterprise.

Benefits of Volunteering for Nursing Students

The main benefits of volunteering cited by respondents in our survey were learning new

skills, improving general health and wellbeing, and improved personal development. This

finding is significant in that the health benefits to volunteers and recipients are largely

anecdotal (Cassidy et al 2008; Holdsworth & Quinn 2010). Bell et. al 2014 make reference to

the tendency to assume that volunteering is beneficial without citing specific evidence.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

19

Positive learning emerges from a situation predicated upon equality of social relations (Boeck

et al, 2009). This is very important as nursing students and nurses are embedded in a series of

nested and inter-penetrating hierarchies, including both subordinated roles (lecturer-student;

ward manager-nurse; ward manager-nursing student; doctor-nurse) and roles where, although

they may not reflect on the fact, they are generally in the superordinate position

(professional-client; nurse-health care assistant; nurse-nurse student). It would therefore seem

that volunteering, as well as providing opportunities to increase skills, confidence and

empathy, also contain a hidden curriculum message, namely that the learning process benefits

from an equalization of power, and thus has implications for how nurses, nurse tutors and

nursing managers, conduct themselves when in superordinate positions. While student

volunteering may not automatically result in leaning, nor directly link to the development of

caring and compassionate practice, nonetheless volunteering does provide a way for students

to make sense of their experiences through opportunities intentionally designed to foster

critical thinking.

Implications for Nurse Education

Nursing students share many of these characteristics associated with increased volunteering

but the limited evidence available suggests that they have very low rates of volunteering

compared to the student average and this may be in part attributable to the structure of

nursing programmes, which allows little free time compared to other undergraduate

programmes. The abolition of bursaries for students nurses from 2017 may increase the

amount of paid work undertaken by student nurses and thus further limit volunteering,

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

19

Positive learning emerges from a situation predicated upon equality of social relations (Boeck

et al, 2009). This is very important as nursing students and nurses are embedded in a series of

nested and inter-penetrating hierarchies, including both subordinated roles (lecturer-student;

ward manager-nurse; ward manager-nursing student; doctor-nurse) and roles where, although

they may not reflect on the fact, they are generally in the superordinate position

(professional-client; nurse-health care assistant; nurse-nurse student). It would therefore seem

that volunteering, as well as providing opportunities to increase skills, confidence and

empathy, also contain a hidden curriculum message, namely that the learning process benefits

from an equalization of power, and thus has implications for how nurses, nurse tutors and

nursing managers, conduct themselves when in superordinate positions. While student

volunteering may not automatically result in leaning, nor directly link to the development of

caring and compassionate practice, nonetheless volunteering does provide a way for students

to make sense of their experiences through opportunities intentionally designed to foster

critical thinking.

Implications for Nurse Education

Nursing students share many of these characteristics associated with increased volunteering

but the limited evidence available suggests that they have very low rates of volunteering

compared to the student average and this may be in part attributable to the structure of

nursing programmes, which allows little free time compared to other undergraduate

programmes. The abolition of bursaries for students nurses from 2017 may increase the

amount of paid work undertaken by student nurses and thus further limit volunteering,

MANUSCRIPTACCEPTED

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

20

although no evidence as yet available on this point. Increasing costs of education have been

shown to negatively impact on volunteering amongst higher education students generally

(Haski-Leventhal et al, 2008).

Building structured opportunities for student volunteering may prove problematic for reasons

already suggested. However, volunteering as a structured activity within the curriculum does

have potential to contribute to both the achievement of competencies and the acquisition of

the more esoteric and abstract qualities associated with nursing. A structured volunteering

activity, when followed with students’ reflection on the volunteering experience provides the