Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Work Environment and Depressive Symptoms

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|14

|11489

|197

AI Summary

This study provides systematically graded evidence for possible associations between work environment factors and near-future development of depressive symptoms. The study finds that lack of decision latitude, job strain, and bullying are associated with increasing depressive symptoms over time. The review includes studies with a prospective design and is focused on the relationship between working conditions and development of symptoms of depression among the employees.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E Open Access

A systematic review including meta-analysis

of work environment and depressive symptoms

Töres Theorell1,2*

, Anne Hammarström3

, Gunnar Aronsson4

, LilTräskman Bendz5

, Tom Grape6

, Christer Hogstedt7

,

Ina Marteinsdottir8

, Ingmar Skoog9 and Charlotte Hall10

Abstract

Background:Depressive symptoms are potential outcomes of poorly functioning work environments.Such

symptoms are frequent and cause considerable suffering for the employees as well as financial loss for the

Accordingly good prospective studies of psychosocial working conditions and depressive symptoms are va

Scientific reviews of such studies have pointed at methodological difficulties but still established a few job

Those reviews were published some years ago.There is need for an updated systematic review using the GRADE

system.In addition,gender related questions have been insufficiently reviewed.

Method: Inclusion criteria for the studies published 1990 to June 2013:1.European and English speaking countries.2.

Quantified results describing the relationship between exposure (psychosocial or physical/chemical) and o

(standardized questionnaire assessment of depressive symptoms or interview-based clinical depression).3.Prospective

or comparable case-control design with at least 100 participants.4.Assessments of exposure (working conditions) and

outcome at baseline and outcome (depressive symptoms) once again after follow-up 1-5 years later.5.Adjustment for

age and adjustment or stratification for gender.

Studies filling inclusion criteria were subjected to assessment of 1.) relevance and 2.) quality using predefi

criteria.Systematic review of the evidence was made using the GRADE system.When applicable,meta-analysis of

the magnitude of associations was made.Consistency of findings was examined for a number of possible

confounders and publication bias was discussed.

Results:Fifty-nine articles of high or medium high scientific quality were included.Moderately strong evidence

(grade three out of four) was found for job strain (high psychologicaldemands and low decision latitude),low

decision latitude and bullying having significant impact on development of depressive symptoms.Limited

evidence (grade two) was shown for psychologicaldemands,effort reward imbalance,low support,unfavorable

socialclimate,lack of work justice,conflicts,limited skilldiscretion,job insecurity and long working hours.There

was no differentialgender effect of adverse job conditions on depressive symptoms

Conclusion:There is substantialempiricalevidence that employees,both men and women,who report lack of

decision latitude,job strain and bullying,willexperience increasing depressive symptoms over time.These

conditions are amenable to organizationalinterventions.

Keywords:Depression,Work stress,Prevention,Ergonomic,Toxicology

* Correspondence:tores.theorell@stressforskning.su.se

1Stress Research Institute,Stockholm University,SE-106 91 Stockholm,

Sweden

2Department of Neuroscience,Karolinska Institutet,SE- 171 77 Stockholm,

Sweden

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2015 Theorellet al.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,

provided the originalwork is properly credited.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://

creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738

DOI10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4

A systematic review including meta-analysis

of work environment and depressive symptoms

Töres Theorell1,2*

, Anne Hammarström3

, Gunnar Aronsson4

, LilTräskman Bendz5

, Tom Grape6

, Christer Hogstedt7

,

Ina Marteinsdottir8

, Ingmar Skoog9 and Charlotte Hall10

Abstract

Background:Depressive symptoms are potential outcomes of poorly functioning work environments.Such

symptoms are frequent and cause considerable suffering for the employees as well as financial loss for the

Accordingly good prospective studies of psychosocial working conditions and depressive symptoms are va

Scientific reviews of such studies have pointed at methodological difficulties but still established a few job

Those reviews were published some years ago.There is need for an updated systematic review using the GRADE

system.In addition,gender related questions have been insufficiently reviewed.

Method: Inclusion criteria for the studies published 1990 to June 2013:1.European and English speaking countries.2.

Quantified results describing the relationship between exposure (psychosocial or physical/chemical) and o

(standardized questionnaire assessment of depressive symptoms or interview-based clinical depression).3.Prospective

or comparable case-control design with at least 100 participants.4.Assessments of exposure (working conditions) and

outcome at baseline and outcome (depressive symptoms) once again after follow-up 1-5 years later.5.Adjustment for

age and adjustment or stratification for gender.

Studies filling inclusion criteria were subjected to assessment of 1.) relevance and 2.) quality using predefi

criteria.Systematic review of the evidence was made using the GRADE system.When applicable,meta-analysis of

the magnitude of associations was made.Consistency of findings was examined for a number of possible

confounders and publication bias was discussed.

Results:Fifty-nine articles of high or medium high scientific quality were included.Moderately strong evidence

(grade three out of four) was found for job strain (high psychologicaldemands and low decision latitude),low

decision latitude and bullying having significant impact on development of depressive symptoms.Limited

evidence (grade two) was shown for psychologicaldemands,effort reward imbalance,low support,unfavorable

socialclimate,lack of work justice,conflicts,limited skilldiscretion,job insecurity and long working hours.There

was no differentialgender effect of adverse job conditions on depressive symptoms

Conclusion:There is substantialempiricalevidence that employees,both men and women,who report lack of

decision latitude,job strain and bullying,willexperience increasing depressive symptoms over time.These

conditions are amenable to organizationalinterventions.

Keywords:Depression,Work stress,Prevention,Ergonomic,Toxicology

* Correspondence:tores.theorell@stressforskning.su.se

1Stress Research Institute,Stockholm University,SE-106 91 Stockholm,

Sweden

2Department of Neuroscience,Karolinska Institutet,SE- 171 77 Stockholm,

Sweden

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2015 Theorellet al.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,

provided the originalwork is properly credited.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://

creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738

DOI10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Background

Depressive symptomsare potentialoutcomesof poorly

functioning work environments.Such symptoms are fre-

quentand may cause considerable suffering for the em-

ployeesthemselvesas well as financialloss for the

employers.Accordingly good prospective studies ofpsy-

chosocial working conditions and depressive symptoms are

valuable.

Several reviews including prospectivestudies of

psychosocialfactorsat work in relation to depression

have been published.Bonde [1]concluded thatthere

were consistent findings that perception ofadverse psy-

chosocialfactors in the workplace is related to an ele-

vated risk ofsubsequent depressive symptoms or major

depressive episode butalso thatmethodologicallimita-

tions preclude causalinference.Netterström etal. [2]

made a similar conclusion butpointed outthatstudies

are needed thatassess in more detailthe duration and

intensity ofexposure necessary fordeveloping depres-

sion.The conclusions in a review by Siegristfrom the

same year [3]were similar.Also, Michie and Williams

[4] concluded that” many ofthe work related variables

associated with high levels of psychological ill health,are

potentially amenable to change which has been shown

in intervention studies thathave successfully improved

psychologicalhealth and reduced sickness absence”.A

review ofpsychosocialand health effects ofworkplace

reorganization by Egan etal. [5] concluded that” some

organizational-levelparticipationinterventionsmay

benefitemployee health,as predicted by the demand-

control model”.However,severalother psychosocial

exposures should be examined more in detail.

Most of the work environment reviews published so far

have notbeen confined to depression only - they have

included for instance stress related disorders, psychologic-

ally related sick leave and suicide or combinations [4, 6–8]

as outcomes,and it has sometimes been difficult to disen-

tanglethem.Studied workenvironmentfactorshave

mostly been limited to psychosocialfactors although two

reviews have included physical/chemical/ergonomic expo-

sures as well.The conclusion from them [4,7] was that

the evidence for physical/chemical/ergonomic exposures

is limited and inconclusive.Nieuwenhuijsen et al.[8] pub-

lished a review of the effects of the psychosocial environ-

ment on risk of stress-relateddisorders(SRDs) and

concluded that there is” strong evidence that high job de-

mands,low job control, low co-workersupport,low

supervisor support,low proceduraljustice and a high ef-

fort- reward imbalance predicted the incidence of SRDs”.

In summary,the evidence aboutthe negative impact

of certain work environments for depressive symptoms

is accumulating butso far there hasbeen no review

taking the entire spectrum ofadverse working condi-

tions into accountand at the same time focusing on

depressiveconditions/symptomsas outcome.Most of

the reviews have used multiple kinds ofmentalhealth

outcomes.However,depression is the mostwidely re-

ported outcome in the field ofmentalhealth in epi-

demiologicalresearch.Depressivesymptomsare well

understood in psychiatry which has resulted in a large

numberof studies.Accordinglythis outcomeshould

provide a good basis for a focused systematic review.As

far as the authors know there is no published study that

has used the internationalGRADE system [9] for evalu-

ating the evidence in thisfield.In addition there is a

need for a systematic review utilizing the mostrecent

developments in search technology.

An important aspect ofthe systematic review process

is to systematically and transparently assess the scientific

evidence.We have chosen to use the internationally rec-

ognized GRADE-system forscientific evaluation.The

GRADE system usesfour levelsof evidence,namely

High,Moderate,Limited and Very Limited.We are well

aware that the system has been developed primarily for

assessing interventions in a health care context,but the

system has been adapted to epidemiologicalevaluation.

Beside the transparency,an advantageis that the

GRADE system [9]- a system often applied in reviews

conducted within the Cochrane Collaboration -is in-

creasingly used internationally e.g.,by the World Health

Organization.Hence results from systematic reviews can

be more easily compared.

Time has elapsed since mostof the previous reviews

were published and new studies are published continu-

ously.The most relevant reviews were published in 2008.

They pointed atseveralmethodologicalshortcomings,

and it is not known whether researchers more recently

have tried to address the identified scientific problems.In

particular,the reviews have pointed at the paucity of stud-

ies on physical/chemical/ergonomic exposures.

A topic that has not been addressed sufficiently in pre-

vious reviewsis genderin the relationship between

working conditions and the developmentof depressive

symptoms.Are the associationsdifferentfor men and

women?

Aim of the study

The aim of this studywas to providesystematically

graded evidence for possible associations between work

environment factors and near-future development of de-

pressive symptoms

Methods

The present review was based upon studies with a pro-

spectivedesignand is focusedon the relationship

between working conditions and development ofsymp-

toms of depression among theemployees..We con-

ducted and funded thissystematicreview within the

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 2 of 14

Depressive symptomsare potentialoutcomesof poorly

functioning work environments.Such symptoms are fre-

quentand may cause considerable suffering for the em-

ployeesthemselvesas well as financialloss for the

employers.Accordingly good prospective studies ofpsy-

chosocial working conditions and depressive symptoms are

valuable.

Several reviews including prospectivestudies of

psychosocialfactorsat work in relation to depression

have been published.Bonde [1]concluded thatthere

were consistent findings that perception ofadverse psy-

chosocialfactors in the workplace is related to an ele-

vated risk ofsubsequent depressive symptoms or major

depressive episode butalso thatmethodologicallimita-

tions preclude causalinference.Netterström etal. [2]

made a similar conclusion butpointed outthatstudies

are needed thatassess in more detailthe duration and

intensity ofexposure necessary fordeveloping depres-

sion.The conclusions in a review by Siegristfrom the

same year [3]were similar.Also, Michie and Williams

[4] concluded that” many ofthe work related variables

associated with high levels of psychological ill health,are

potentially amenable to change which has been shown

in intervention studies thathave successfully improved

psychologicalhealth and reduced sickness absence”.A

review ofpsychosocialand health effects ofworkplace

reorganization by Egan etal. [5] concluded that” some

organizational-levelparticipationinterventionsmay

benefitemployee health,as predicted by the demand-

control model”.However,severalother psychosocial

exposures should be examined more in detail.

Most of the work environment reviews published so far

have notbeen confined to depression only - they have

included for instance stress related disorders, psychologic-

ally related sick leave and suicide or combinations [4, 6–8]

as outcomes,and it has sometimes been difficult to disen-

tanglethem.Studied workenvironmentfactorshave

mostly been limited to psychosocialfactors although two

reviews have included physical/chemical/ergonomic expo-

sures as well.The conclusion from them [4,7] was that

the evidence for physical/chemical/ergonomic exposures

is limited and inconclusive.Nieuwenhuijsen et al.[8] pub-

lished a review of the effects of the psychosocial environ-

ment on risk of stress-relateddisorders(SRDs) and

concluded that there is” strong evidence that high job de-

mands,low job control, low co-workersupport,low

supervisor support,low proceduraljustice and a high ef-

fort- reward imbalance predicted the incidence of SRDs”.

In summary,the evidence aboutthe negative impact

of certain work environments for depressive symptoms

is accumulating butso far there hasbeen no review

taking the entire spectrum ofadverse working condi-

tions into accountand at the same time focusing on

depressiveconditions/symptomsas outcome.Most of

the reviews have used multiple kinds ofmentalhealth

outcomes.However,depression is the mostwidely re-

ported outcome in the field ofmentalhealth in epi-

demiologicalresearch.Depressivesymptomsare well

understood in psychiatry which has resulted in a large

numberof studies.Accordinglythis outcomeshould

provide a good basis for a focused systematic review.As

far as the authors know there is no published study that

has used the internationalGRADE system [9] for evalu-

ating the evidence in thisfield.In addition there is a

need for a systematic review utilizing the mostrecent

developments in search technology.

An important aspect ofthe systematic review process

is to systematically and transparently assess the scientific

evidence.We have chosen to use the internationally rec-

ognized GRADE-system forscientific evaluation.The

GRADE system usesfour levelsof evidence,namely

High,Moderate,Limited and Very Limited.We are well

aware that the system has been developed primarily for

assessing interventions in a health care context,but the

system has been adapted to epidemiologicalevaluation.

Beside the transparency,an advantageis that the

GRADE system [9]- a system often applied in reviews

conducted within the Cochrane Collaboration -is in-

creasingly used internationally e.g.,by the World Health

Organization.Hence results from systematic reviews can

be more easily compared.

Time has elapsed since mostof the previous reviews

were published and new studies are published continu-

ously.The most relevant reviews were published in 2008.

They pointed atseveralmethodologicalshortcomings,

and it is not known whether researchers more recently

have tried to address the identified scientific problems.In

particular,the reviews have pointed at the paucity of stud-

ies on physical/chemical/ergonomic exposures.

A topic that has not been addressed sufficiently in pre-

vious reviewsis genderin the relationship between

working conditions and the developmentof depressive

symptoms.Are the associationsdifferentfor men and

women?

Aim of the study

The aim of this studywas to providesystematically

graded evidence for possible associations between work

environment factors and near-future development of de-

pressive symptoms

Methods

The present review was based upon studies with a pro-

spectivedesignand is focusedon the relationship

between working conditions and development ofsymp-

toms of depression among theemployees..We con-

ducted and funded thissystematicreview within the

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 2 of 14

framework for the Swedish Council on Health and Tech-

nology Assessment,a public agency with the charge of

providing impartial and scientifically reliable information

to decision makers and health care providers [10].

Search strategy

Systematic literature search was performed in the following

data bases:PubMed,Embase,Psycinfo,Arbline (Swedish

database),Cochrane library and NIOSHTIC-2.A combin-

ation of controlled search words (e.g., MeSH) and free- text

words was used.The search strategy for the outcome was

performed formesh terms (‘Depression’and ‘Depressive

Disorders’) and as free search in title and abstract (depress*

and dysthym*).The whole search strategy is available at

http://www.sbu.se/upload/Publikationer/Content0/1/223E/

Inclusion%20criteria_occupational%20exposure_depression

_burnout.pdf.We only accepted asarticlesin scientific

journals with independent reviews.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies were:

1. The study should have examined the importance of

the work environment for depressive symptoms.

Our review was not confined to any specific kind of

work environment factors.Physical/chemical/

ergonomic exposures as well as psychosocial factors

were screened.

2. The study should be relevant for Swedish conditions

and focused on people at work.Work environments

in Europe,North America,Australia and New

Zealand were included.

3. In the study symptoms of depression should have

been analyzed.These should have have been

certified through diagnostic investigation or with

established scales.We argued that not only

diagnosed major depression,but also milder states

with depressive symptoms are relevant since

depressive feelings give rise to suffering,increase the

risk of long term sick leave and cause productivity

decline and quality loss in work places [11].Thus,

our review included both studies with standardized

clinical interviews regarding diagnosed depression

and studies based upon rating scales on depressive

symptoms.As diagnosed depression is also to a large

extent based on symptoms we decided that the most

accurate naming of the outcome of our review was

depressive symptoms.A few studies were based

upon either sick leave data or registered anti-

depression medication as outcome but these studies

are not included in this review.

4. A minimum of 100 persons should have been

included in the exposed group and the results were

controlled for at least age and gender.

5. The study should have been published between the

years 1990 and (June) 2013 and written in English.

6. Prospective or comparable case-control design. Only

prospective cohort, case control (with design equivalen

to prospective) and randomized intervention studies

with at least 100 participants were included. By case

control studies with “design equivalent to prospective”

we are referring to studies with strict definition of cases

recruited in a representative way in the same

population as the control group.

Assessments ofexposure should have been made be-

fore disease onset.

Doubletswere systematically identified and only the

most relevant publication in a doublet was included.

Analyses of relevance and quality

Abstractscreening and full-textassessmentwere con-

ducted by a specialistin occupationalmedicine and a

psychiatrist.

After that,the scientific experts started their examin-

ation.Pre-set evaluation forms were used.The experts

judged relevance and quality of the studies on the basis

of the relevance/quality criteria,their experience as re-

searchers and their knowledge of the field.Accordingly

they were recruited amongSwedish academichigh

ranking specialists in fields of relevance for the process,

namely psychiatry (three),epidemiology and stress re-

search (three),work psychology (one) and family prac-

tice (one).This group was divided into pairs with as

widely differing specialty in the pair as possible.In the

following process,the articles remaining in the process

were randomly assigned to the four pairs (with avoid-

ance of author bias).Concordance in judgments of rele-

vance and quality was trained.After the training

session,each member ofthe pair did the assessments

separately,and then discordances were discussed within

the pair.If disagreementremained anotherpair was

asked to make an independentjudgment.If thatdeci-

sion was in disagreement with the first group,we made

the decision in the whole group.

In the firstexpertphase,the group judged relevance.

Relevance criteria are presented in http://www.sbu.se/up-

load/Publikationer/Content0/1/223E/Inclusion%20criteria

_occupational%20exposure_depression_burnout.pdf.

Secondly,we performed a quality assessment.Three

levelsof quality rating were used,(low, medium high

and high quality)and in the finalgrading process only

those with medium high and high quality were accepted.

Accordinglythe importantdividing linewas between

poor and medium high quality whereas the distinction

between medium high and high was less crucial.Studies

on the borderline between low and medium high quality

were accordingly re-examined by the whole group.A list

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 3 of 14

nology Assessment,a public agency with the charge of

providing impartial and scientifically reliable information

to decision makers and health care providers [10].

Search strategy

Systematic literature search was performed in the following

data bases:PubMed,Embase,Psycinfo,Arbline (Swedish

database),Cochrane library and NIOSHTIC-2.A combin-

ation of controlled search words (e.g., MeSH) and free- text

words was used.The search strategy for the outcome was

performed formesh terms (‘Depression’and ‘Depressive

Disorders’) and as free search in title and abstract (depress*

and dysthym*).The whole search strategy is available at

http://www.sbu.se/upload/Publikationer/Content0/1/223E/

Inclusion%20criteria_occupational%20exposure_depression

_burnout.pdf.We only accepted asarticlesin scientific

journals with independent reviews.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies were:

1. The study should have examined the importance of

the work environment for depressive symptoms.

Our review was not confined to any specific kind of

work environment factors.Physical/chemical/

ergonomic exposures as well as psychosocial factors

were screened.

2. The study should be relevant for Swedish conditions

and focused on people at work.Work environments

in Europe,North America,Australia and New

Zealand were included.

3. In the study symptoms of depression should have

been analyzed.These should have have been

certified through diagnostic investigation or with

established scales.We argued that not only

diagnosed major depression,but also milder states

with depressive symptoms are relevant since

depressive feelings give rise to suffering,increase the

risk of long term sick leave and cause productivity

decline and quality loss in work places [11].Thus,

our review included both studies with standardized

clinical interviews regarding diagnosed depression

and studies based upon rating scales on depressive

symptoms.As diagnosed depression is also to a large

extent based on symptoms we decided that the most

accurate naming of the outcome of our review was

depressive symptoms.A few studies were based

upon either sick leave data or registered anti-

depression medication as outcome but these studies

are not included in this review.

4. A minimum of 100 persons should have been

included in the exposed group and the results were

controlled for at least age and gender.

5. The study should have been published between the

years 1990 and (June) 2013 and written in English.

6. Prospective or comparable case-control design. Only

prospective cohort, case control (with design equivalen

to prospective) and randomized intervention studies

with at least 100 participants were included. By case

control studies with “design equivalent to prospective”

we are referring to studies with strict definition of cases

recruited in a representative way in the same

population as the control group.

Assessments ofexposure should have been made be-

fore disease onset.

Doubletswere systematically identified and only the

most relevant publication in a doublet was included.

Analyses of relevance and quality

Abstractscreening and full-textassessmentwere con-

ducted by a specialistin occupationalmedicine and a

psychiatrist.

After that,the scientific experts started their examin-

ation.Pre-set evaluation forms were used.The experts

judged relevance and quality of the studies on the basis

of the relevance/quality criteria,their experience as re-

searchers and their knowledge of the field.Accordingly

they were recruited amongSwedish academichigh

ranking specialists in fields of relevance for the process,

namely psychiatry (three),epidemiology and stress re-

search (three),work psychology (one) and family prac-

tice (one).This group was divided into pairs with as

widely differing specialty in the pair as possible.In the

following process,the articles remaining in the process

were randomly assigned to the four pairs (with avoid-

ance of author bias).Concordance in judgments of rele-

vance and quality was trained.After the training

session,each member ofthe pair did the assessments

separately,and then discordances were discussed within

the pair.If disagreementremained anotherpair was

asked to make an independentjudgment.If thatdeci-

sion was in disagreement with the first group,we made

the decision in the whole group.

In the firstexpertphase,the group judged relevance.

Relevance criteria are presented in http://www.sbu.se/up-

load/Publikationer/Content0/1/223E/Inclusion%20criteria

_occupational%20exposure_depression_burnout.pdf.

Secondly,we performed a quality assessment.Three

levelsof quality rating were used,(low, medium high

and high quality)and in the finalgrading process only

those with medium high and high quality were accepted.

Accordinglythe importantdividing linewas between

poor and medium high quality whereas the distinction

between medium high and high was less crucial.Studies

on the borderline between low and medium high quality

were accordingly re-examined by the whole group.A list

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 3 of 14

of relevant articles meeting the inclusion criteria judged

to be of low quality is available at http://www.sbu.se/up-

load/Publikationer/Content0/1/223E/Inclusion%20cri-

teria_occupational%20exposure_depression_burnout.pdf

The following aspects of quality were considered:

1.) Representativeness of study sample.

Representativeness and ways of defining and

recruiting the sample as well as attrition in different

steps were considered in the quality rating.

Statistical considerations and an insightful discussion

of possible consequences of a possible systematic

drop-out for findings were required in case of

marked drop-out problems.

2.) Confounding.Age and at least some aspect of

socioeconomic conditions should have been

considered.Gender specific analyses were preferred

but when such analyses were not available,

adjustment for gender was required.Life habits such

as smoking habits and alcohol consumption were

not taken into account as confounders in our

review.

3.) Prospective data collection. All results of the studies

included in this review (apart from case-control

studies) are based upon assessments of exposure and

depressive symptoms in the beginning and of the

depressive symptoms again at least one year later. In

the calculations of associations a design with either

exclusion of subjects with depressive symptoms at

baseline or adjustment for baseline level of depressive

symptoms was required. Qualified statistics and

thorough discussion of longitudinal data rendered

higher quality ratings.

4.) For both exposure and outcome assessment,

psychometrically standardized and validated

methods were required.Well established methods

enable comparison across studies and therefore

contributed to higher quality rating.

5.) Designs that enable the analysis of a dose response

relationship contributed to a high quality rating.For

instance,in a few studies the work environment was

assessed in two or three subsequent waves and the

development of depressive symptoms followed up

after the last assessment.Exposure to given work

environment factor on one,two or three occasions

could be regarded as a progressive duration of

exposure and was regarded as equivalent of a dose-

response analysis.

Even between studiesof specific work environment

factors there were differences with regard to operationa-

lization ofexposure.Examples are job strain (combin-

ation ofhigh psychologicaldemands and low decision

latitude)and effortreward imbalance (combination of

high effortand poor reward).Since the overallaim of

the present study was to grade total evidence,not to as-

sess magnitude of associations,and since it was impos-

sible to re-constructoperationalizations in such a way

that they would match one another we decided to use

the definitions presented by the authors themselves and

to mostly abstain from assessment of overall magnitude

of the different relationships.

The final list of studiesjudged to be of high or

medium high quality is listed in Appendix.

GRADE procedure

An importantaspectof the systematic review process

was to systematically and transparently assess the scien-

tific evidence.According to the GRADE instructions

explicitconsideration should be given to each ofthe

GRADE criteria forassessing the quality ofevidence

(risk of bias/study limitations,directness,consistency of

results,precision,publication bias,magnitude of the ef-

fect,dose-response gradient,influence of residual plaus-

ible confounding and bias “antagonistic bias”) although

different terminology may be used.For level4 (=High),

randomized trials are required and there were no such

published relevantstudies in our search.For observa-

tional studies of the kind included in the present review,

the highestpossible grade isModerate = 3 ifthere is

sufficient reason for an upgrading from the normal level

for such studies of 2 (=Limited).Level 1 (=Very limited)

corresponds to evidence based on case reports and case

series or on reports downgraded evidence from observa-

tional studies.

We allowed for upgradingthe scientificevidence

when there wasstrong coherence ofresultsbetween

studies - according to the most recent guidelines [12].

Accordingly when there were many published observa-

tional studiesof medium high or high qualitywith

homogenousresults(almostall pointing in the same

direction although all findings may not have been statis-

tically significant)the evidence was graded on level3

(two exposures,high decision latitude as protective and

job strain as negative exposure,see below).Level3 can

also be used according to the GRADE system even when

there are relatively few studies ifthere are unanimous

findings with high odds ratios (above 2.0). This occurred

for one exposure – bullying (see below).

Meta-analyses/Forest plots

In the studies results were reported as calculations of

association,e.g.,expressed as odds ratios,from mul-

tiple logistic regression,multivariatecorrelationsor

multiple linear regression coefficients.Whenever pos-

sible,the results were transformed into multiple logis-

tic regression odds ratios.Forestplots were used for

visual interpretation.To assist in illustrating the

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 4 of 14

to be of low quality is available at http://www.sbu.se/up-

load/Publikationer/Content0/1/223E/Inclusion%20cri-

teria_occupational%20exposure_depression_burnout.pdf

The following aspects of quality were considered:

1.) Representativeness of study sample.

Representativeness and ways of defining and

recruiting the sample as well as attrition in different

steps were considered in the quality rating.

Statistical considerations and an insightful discussion

of possible consequences of a possible systematic

drop-out for findings were required in case of

marked drop-out problems.

2.) Confounding.Age and at least some aspect of

socioeconomic conditions should have been

considered.Gender specific analyses were preferred

but when such analyses were not available,

adjustment for gender was required.Life habits such

as smoking habits and alcohol consumption were

not taken into account as confounders in our

review.

3.) Prospective data collection. All results of the studies

included in this review (apart from case-control

studies) are based upon assessments of exposure and

depressive symptoms in the beginning and of the

depressive symptoms again at least one year later. In

the calculations of associations a design with either

exclusion of subjects with depressive symptoms at

baseline or adjustment for baseline level of depressive

symptoms was required. Qualified statistics and

thorough discussion of longitudinal data rendered

higher quality ratings.

4.) For both exposure and outcome assessment,

psychometrically standardized and validated

methods were required.Well established methods

enable comparison across studies and therefore

contributed to higher quality rating.

5.) Designs that enable the analysis of a dose response

relationship contributed to a high quality rating.For

instance,in a few studies the work environment was

assessed in two or three subsequent waves and the

development of depressive symptoms followed up

after the last assessment.Exposure to given work

environment factor on one,two or three occasions

could be regarded as a progressive duration of

exposure and was regarded as equivalent of a dose-

response analysis.

Even between studiesof specific work environment

factors there were differences with regard to operationa-

lization ofexposure.Examples are job strain (combin-

ation ofhigh psychologicaldemands and low decision

latitude)and effortreward imbalance (combination of

high effortand poor reward).Since the overallaim of

the present study was to grade total evidence,not to as-

sess magnitude of associations,and since it was impos-

sible to re-constructoperationalizations in such a way

that they would match one another we decided to use

the definitions presented by the authors themselves and

to mostly abstain from assessment of overall magnitude

of the different relationships.

The final list of studiesjudged to be of high or

medium high quality is listed in Appendix.

GRADE procedure

An importantaspectof the systematic review process

was to systematically and transparently assess the scien-

tific evidence.According to the GRADE instructions

explicitconsideration should be given to each ofthe

GRADE criteria forassessing the quality ofevidence

(risk of bias/study limitations,directness,consistency of

results,precision,publication bias,magnitude of the ef-

fect,dose-response gradient,influence of residual plaus-

ible confounding and bias “antagonistic bias”) although

different terminology may be used.For level4 (=High),

randomized trials are required and there were no such

published relevantstudies in our search.For observa-

tional studies of the kind included in the present review,

the highestpossible grade isModerate = 3 ifthere is

sufficient reason for an upgrading from the normal level

for such studies of 2 (=Limited).Level 1 (=Very limited)

corresponds to evidence based on case reports and case

series or on reports downgraded evidence from observa-

tional studies.

We allowed for upgradingthe scientificevidence

when there wasstrong coherence ofresultsbetween

studies - according to the most recent guidelines [12].

Accordingly when there were many published observa-

tional studiesof medium high or high qualitywith

homogenousresults(almostall pointing in the same

direction although all findings may not have been statis-

tically significant)the evidence was graded on level3

(two exposures,high decision latitude as protective and

job strain as negative exposure,see below).Level3 can

also be used according to the GRADE system even when

there are relatively few studies ifthere are unanimous

findings with high odds ratios (above 2.0). This occurred

for one exposure – bullying (see below).

Meta-analyses/Forest plots

In the studies results were reported as calculations of

association,e.g.,expressed as odds ratios,from mul-

tiple logistic regression,multivariatecorrelationsor

multiple linear regression coefficients.Whenever pos-

sible,the results were transformed into multiple logis-

tic regression odds ratios.Forestplots were used for

visual interpretation.To assist in illustrating the

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 4 of 14

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

results,and as a contribution to the overallassess-

ment, theseforest plots (meta-analyses)were con-

ducted when in at least two studiesthe samerisk

factor was analysed and mathematically comparable

data was provided using theComprehensiveMeta-

Analysis softwarepackage(www.meta-analysis.com/

index.php).Since the participants in the various stud-

ies might be construed as coming from the same popu-

lation (workers)or from differentpopulations(i.e.,

according to each study’s inclusion criteria) we chose

to use a fixed effects model.The strength of the scien-

tific evidence,using data from all of the included stud-

ies (not just those illustrated in the meta-analyses),

was determined by pairs ofthe authors ofthis paper

and then discussed and confirmed by allauthors.In-

formalhomogeneity tests were performed in order to

compare results from studies using standardized de-

pression interviews versus self-reportedquestion-

naires, high quality versus medium high quality

studies,generalpopulation studies versus specific oc-

cupationalcohorts and men versus women.In these

tests,we conducted sub-analyses of the presented find-

ings and compared results between the sub-categories,

e.g.,if the association between job exposure and de-

pressive symptomsdiffered according to the instru-

ment used for assessing the symptoms.

Ethics

All studies perused in this review have been approved by

the scientificethicalcommitteesin their universities.

They have allbeen published in internationalscientific

journalswith peerreview.Accordingly,no additional

ethical approval has been required.

Results

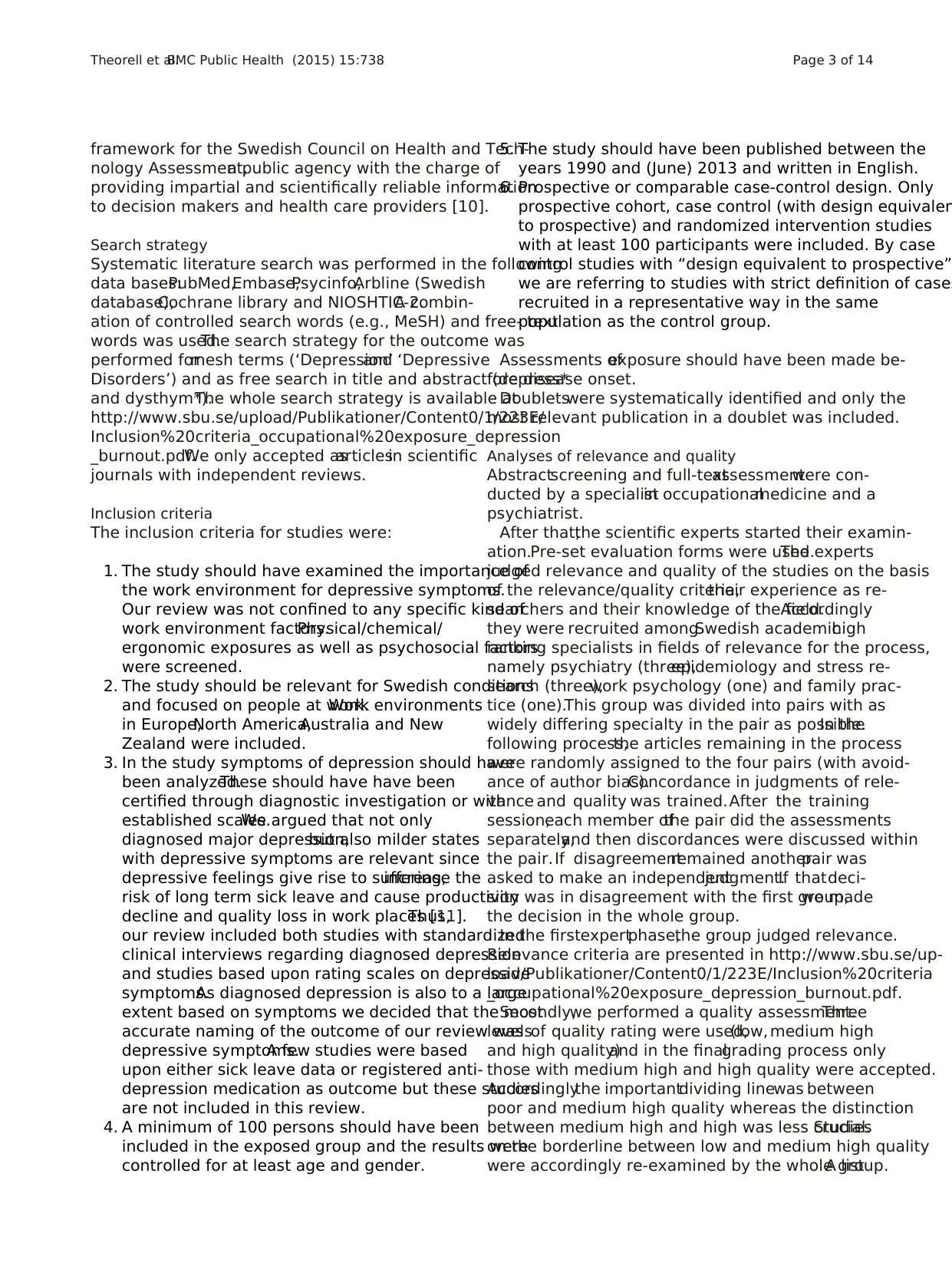

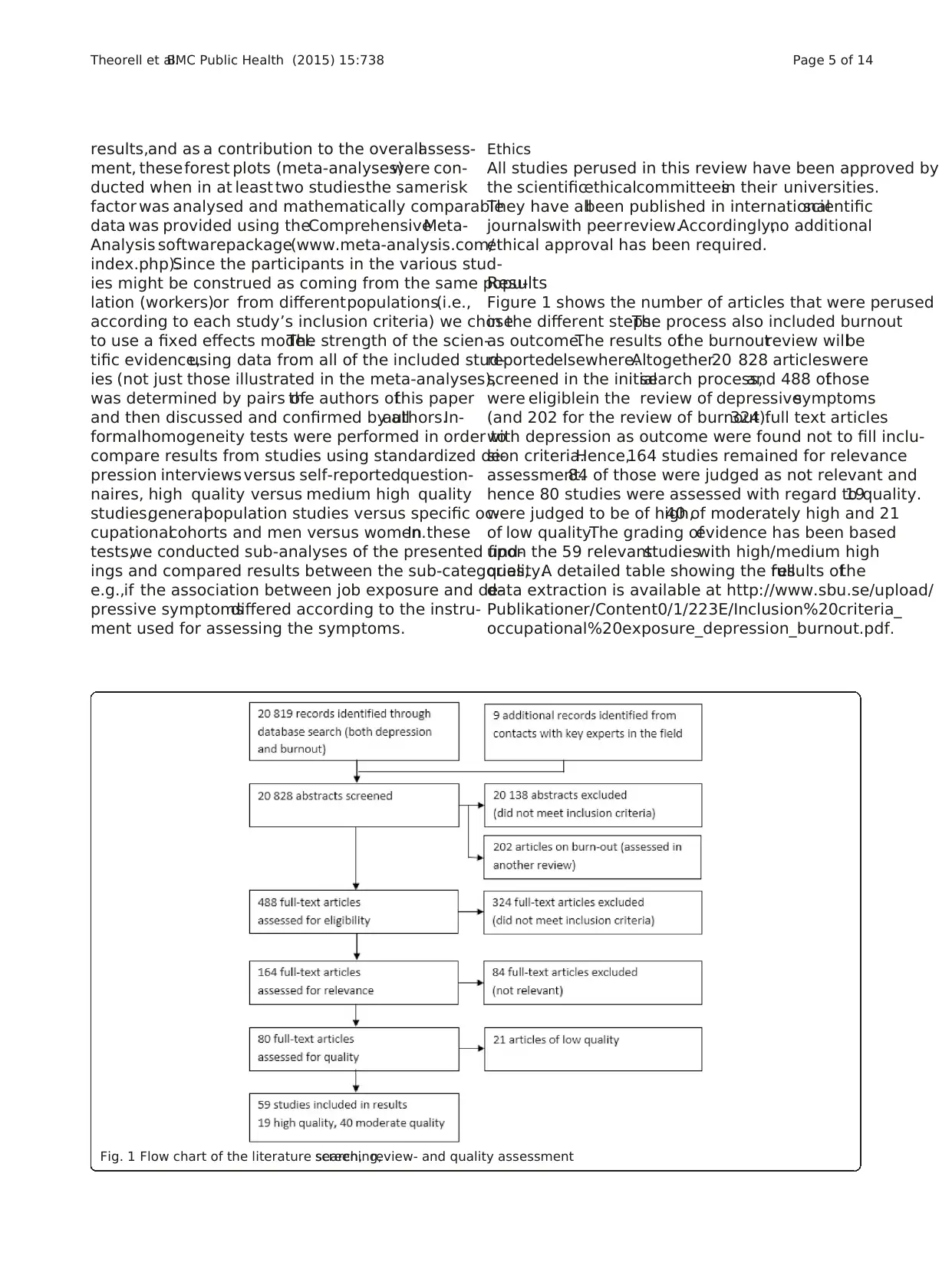

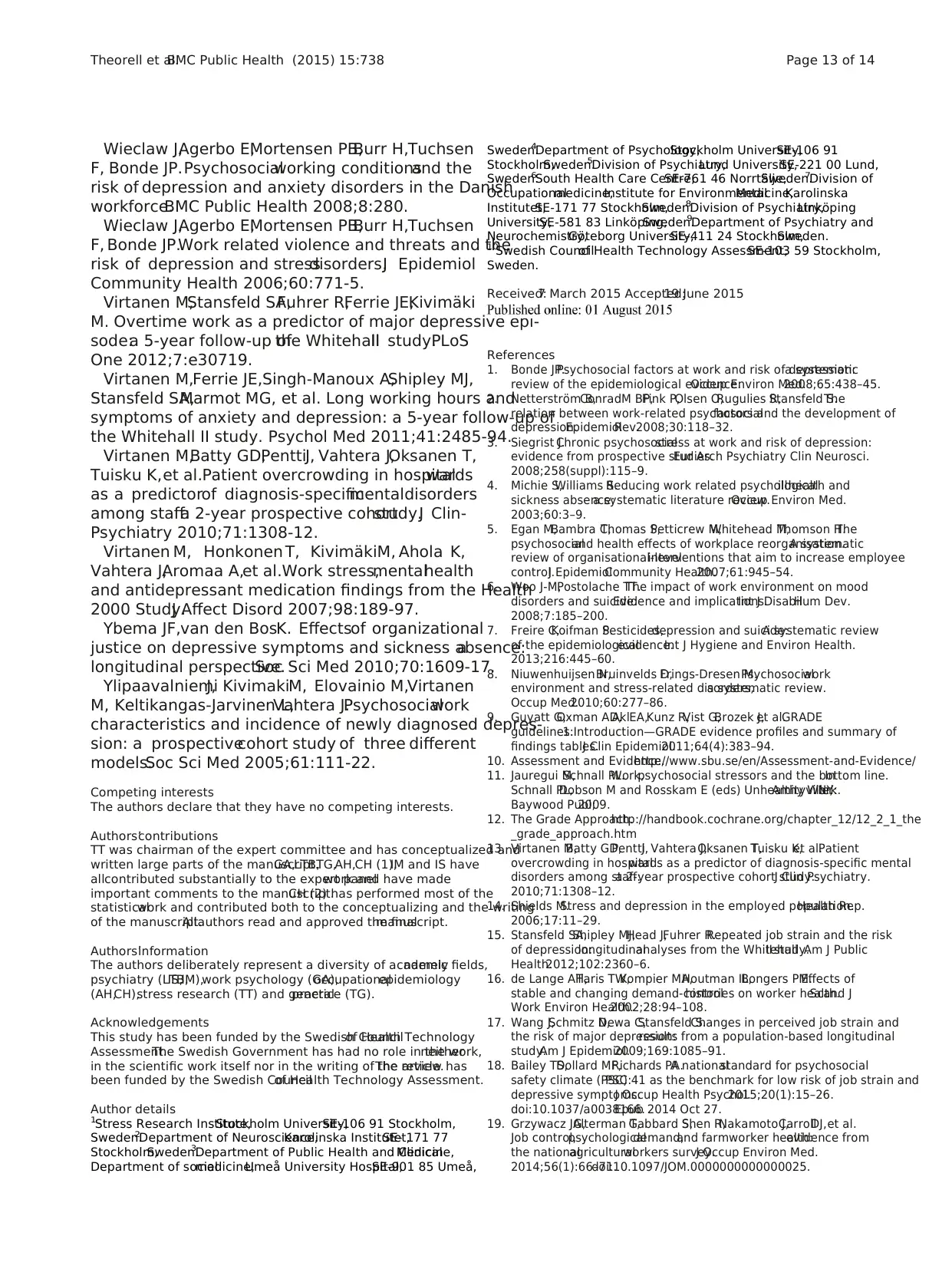

Figure 1 shows the number of articles that were perused

in the different steps.The process also included burnout

as outcome.The results ofthe burnoutreview willbe

reportedelsewhere.Altogether20 828 articleswere

screened in the initialsearch process,and 488 ofthose

were eligiblein the review of depressivesymptoms

(and 202 for the review of burnout).324 full text articles

with depression as outcome were found not to fill inclu-

sion criteria.Hence,164 studies remained for relevance

assessment.84 of those were judged as not relevant and

hence 80 studies were assessed with regard to quality.19

were judged to be of high,40 of moderately high and 21

of low quality.The grading ofevidence has been based

upon the 59 relevantstudieswith high/medium high

quality.A detailed table showing the fullresults ofthe

data extraction is available at http://www.sbu.se/upload/

Publikationer/Content0/1/223E/Inclusion%20criteria_

occupational%20exposure_depression_burnout.pdf.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of the literature search,screening,review- and quality assessment

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 5 of 14

ment, theseforest plots (meta-analyses)were con-

ducted when in at least two studiesthe samerisk

factor was analysed and mathematically comparable

data was provided using theComprehensiveMeta-

Analysis softwarepackage(www.meta-analysis.com/

index.php).Since the participants in the various stud-

ies might be construed as coming from the same popu-

lation (workers)or from differentpopulations(i.e.,

according to each study’s inclusion criteria) we chose

to use a fixed effects model.The strength of the scien-

tific evidence,using data from all of the included stud-

ies (not just those illustrated in the meta-analyses),

was determined by pairs ofthe authors ofthis paper

and then discussed and confirmed by allauthors.In-

formalhomogeneity tests were performed in order to

compare results from studies using standardized de-

pression interviews versus self-reportedquestion-

naires, high quality versus medium high quality

studies,generalpopulation studies versus specific oc-

cupationalcohorts and men versus women.In these

tests,we conducted sub-analyses of the presented find-

ings and compared results between the sub-categories,

e.g.,if the association between job exposure and de-

pressive symptomsdiffered according to the instru-

ment used for assessing the symptoms.

Ethics

All studies perused in this review have been approved by

the scientificethicalcommitteesin their universities.

They have allbeen published in internationalscientific

journalswith peerreview.Accordingly,no additional

ethical approval has been required.

Results

Figure 1 shows the number of articles that were perused

in the different steps.The process also included burnout

as outcome.The results ofthe burnoutreview willbe

reportedelsewhere.Altogether20 828 articleswere

screened in the initialsearch process,and 488 ofthose

were eligiblein the review of depressivesymptoms

(and 202 for the review of burnout).324 full text articles

with depression as outcome were found not to fill inclu-

sion criteria.Hence,164 studies remained for relevance

assessment.84 of those were judged as not relevant and

hence 80 studies were assessed with regard to quality.19

were judged to be of high,40 of moderately high and 21

of low quality.The grading ofevidence has been based

upon the 59 relevantstudieswith high/medium high

quality.A detailed table showing the fullresults ofthe

data extraction is available at http://www.sbu.se/upload/

Publikationer/Content0/1/223E/Inclusion%20criteria_

occupational%20exposure_depression_burnout.pdf.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of the literature search,screening,review- and quality assessment

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 5 of 14

Most studieswere based on population samplesal-

though studies of samples from companies and occupa-

tionalgroups were also present.Few studies thatwere

judged to be relevant were based upon objective assess-

ments ofexposure.Subjective assessments based upon

standardized and validated questionnaires (for instance

demand/control/support,effort/reward,proceduraljust-

ice and bullying)were used in moststudies.The most

widely used established questionnairesrendered high

qualityratings.With regard to depression outcome,

both standardized interviews (mostly Composite Inter-

national DiagnosticInterview,CIDI) performedby

trained interviewers and different versions ofstandard-

ized questionnaires (such as Center for Epidemiological

Studies-Depression Scale,CES-D, and HospitalAnx-

iety and Depression Scale,HAD, and Hamilton Depres-

sion Scale,HRSD) for depressive symptoms were used.

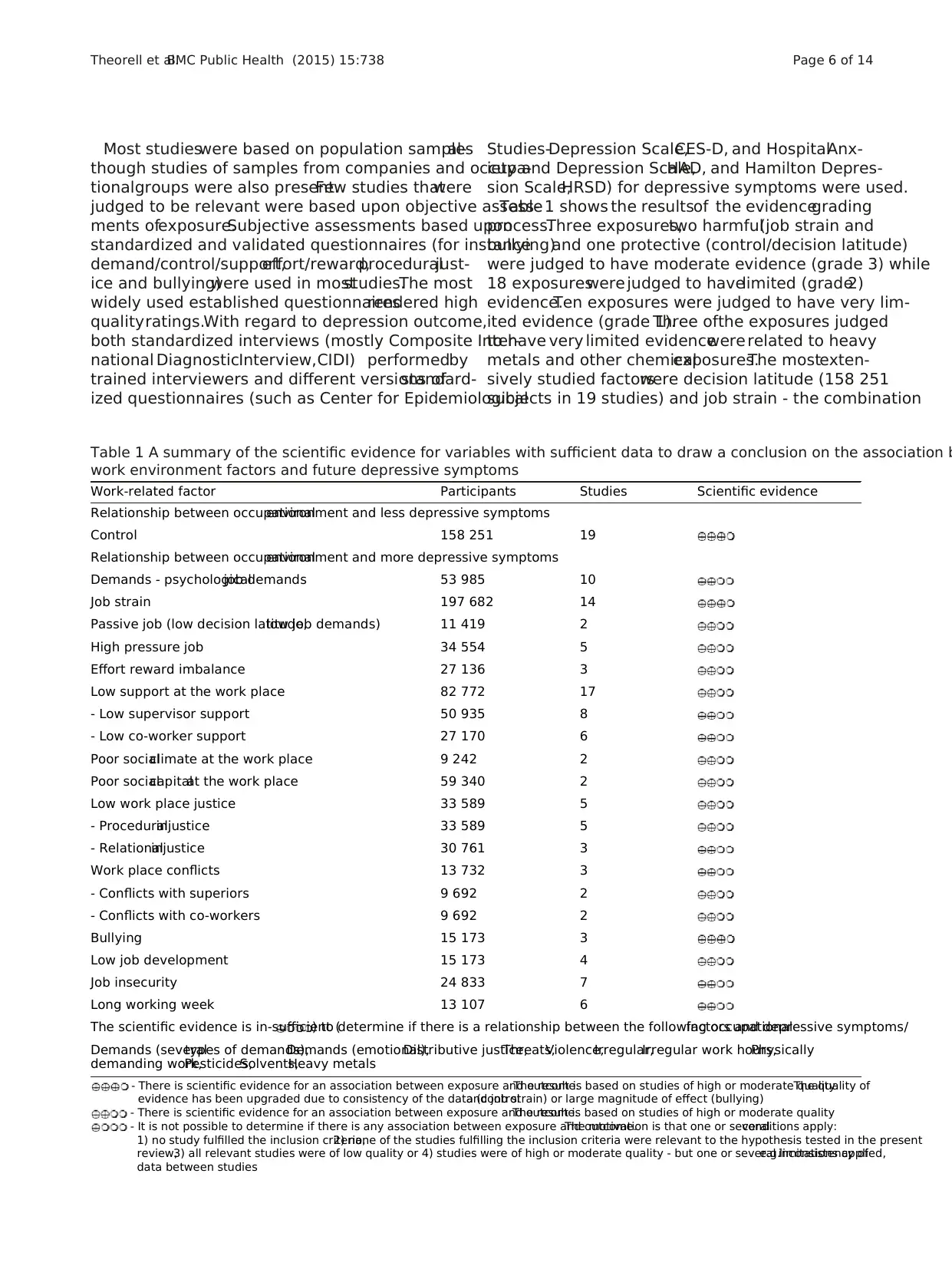

Table1 shows the resultsof the evidencegrading

process.Three exposures,two harmful(job strain and

bullying)and one protective (control/decision latitude)

were judged to have moderate evidence (grade 3) while

18 exposureswere judged to havelimited (grade2)

evidence.Ten exposures were judged to have very lim-

ited evidence (grade 1).Three ofthe exposures judged

to have very limited evidencewere related to heavy

metals and other chemicalexposures.The mostexten-

sively studied factorswere decision latitude (158 251

subjects in 19 studies) and job strain - the combination

Table 1 A summary of the scientific evidence for variables with sufficient data to draw a conclusion on the association b

work environment factors and future depressive symptoms

Work-related factor Participants Studies Scientific evidence

Relationship between occupationalenvironment and less depressive symptoms

Control 158 251 19

Relationship between occupationalenvironment and more depressive symptoms

Demands - psychologicaljob demands 53 985 10

Job strain 197 682 14

Passive job (low decision latitude,low job demands) 11 419 2

High pressure job 34 554 5

Effort reward imbalance 27 136 3

Low support at the work place 82 772 17

- Low supervisor support 50 935 8

- Low co-worker support 27 170 6

Poor socialclimate at the work place 9 242 2

Poor socialcapitalat the work place 59 340 2

Low work place justice 33 589 5

- Proceduralinjustice 33 589 5

- Relationalinjustice 30 761 3

Work place conflicts 13 732 3

- Conflicts with superiors 9 692 2

- Conflicts with co-workers 9 692 2

Bullying 15 173 3

Low job development 15 173 4

Job insecurity 24 833 7

Long working week 13 107 6

The scientific evidence is in-sufficient () to determine if there is a relationship between the following occupationalfactors and depressive symptoms/

Demands (severaltypes of demands),Demands (emotional),Distributive justice,Threats,Violence,Irregular,Irregular work hours,Physically

demanding work,Pesticides,Solvents,Heavy metals

- There is scientific evidence for an association between exposure and outcome.The result is based on studies of high or moderate quality.The quality of

evidence has been upgraded due to consistency of the data (controland job strain) or large magnitude of effect (bullying)

- There is scientific evidence for an association between exposure and outcome.The result is based on studies of high or moderate quality

- It is not possible to determine if there is any association between exposure and outcome.The motivation is that one or severalconditions apply:

1) no study fulfilled the inclusion criteria,2) none of the studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria were relevant to the hypothesis tested in the present

review,3) all relevant studies were of low quality or 4) studies were of high or moderate quality - but one or several limitations applied,e.g.inconsistency of

data between studies

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 6 of 14

though studies of samples from companies and occupa-

tionalgroups were also present.Few studies thatwere

judged to be relevant were based upon objective assess-

ments ofexposure.Subjective assessments based upon

standardized and validated questionnaires (for instance

demand/control/support,effort/reward,proceduraljust-

ice and bullying)were used in moststudies.The most

widely used established questionnairesrendered high

qualityratings.With regard to depression outcome,

both standardized interviews (mostly Composite Inter-

national DiagnosticInterview,CIDI) performedby

trained interviewers and different versions ofstandard-

ized questionnaires (such as Center for Epidemiological

Studies-Depression Scale,CES-D, and HospitalAnx-

iety and Depression Scale,HAD, and Hamilton Depres-

sion Scale,HRSD) for depressive symptoms were used.

Table1 shows the resultsof the evidencegrading

process.Three exposures,two harmful(job strain and

bullying)and one protective (control/decision latitude)

were judged to have moderate evidence (grade 3) while

18 exposureswere judged to havelimited (grade2)

evidence.Ten exposures were judged to have very lim-

ited evidence (grade 1).Three ofthe exposures judged

to have very limited evidencewere related to heavy

metals and other chemicalexposures.The mostexten-

sively studied factorswere decision latitude (158 251

subjects in 19 studies) and job strain - the combination

Table 1 A summary of the scientific evidence for variables with sufficient data to draw a conclusion on the association b

work environment factors and future depressive symptoms

Work-related factor Participants Studies Scientific evidence

Relationship between occupationalenvironment and less depressive symptoms

Control 158 251 19

Relationship between occupationalenvironment and more depressive symptoms

Demands - psychologicaljob demands 53 985 10

Job strain 197 682 14

Passive job (low decision latitude,low job demands) 11 419 2

High pressure job 34 554 5

Effort reward imbalance 27 136 3

Low support at the work place 82 772 17

- Low supervisor support 50 935 8

- Low co-worker support 27 170 6

Poor socialclimate at the work place 9 242 2

Poor socialcapitalat the work place 59 340 2

Low work place justice 33 589 5

- Proceduralinjustice 33 589 5

- Relationalinjustice 30 761 3

Work place conflicts 13 732 3

- Conflicts with superiors 9 692 2

- Conflicts with co-workers 9 692 2

Bullying 15 173 3

Low job development 15 173 4

Job insecurity 24 833 7

Long working week 13 107 6

The scientific evidence is in-sufficient () to determine if there is a relationship between the following occupationalfactors and depressive symptoms/

Demands (severaltypes of demands),Demands (emotional),Distributive justice,Threats,Violence,Irregular,Irregular work hours,Physically

demanding work,Pesticides,Solvents,Heavy metals

- There is scientific evidence for an association between exposure and outcome.The result is based on studies of high or moderate quality.The quality of

evidence has been upgraded due to consistency of the data (controland job strain) or large magnitude of effect (bullying)

- There is scientific evidence for an association between exposure and outcome.The result is based on studies of high or moderate quality

- It is not possible to determine if there is any association between exposure and outcome.The motivation is that one or severalconditions apply:

1) no study fulfilled the inclusion criteria,2) none of the studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria were relevant to the hypothesis tested in the present

review,3) all relevant studies were of low quality or 4) studies were of high or moderate quality - but one or several limitations applied,e.g.inconsistency of

data between studies

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 6 of 14

of high psychologicaldemands and low decision latitude

(197 682 subjects in 14 studies).It was possible to com-

pute a weighted odds ratio 1.74 (95 % CI 1.54 to 1.96 for

studieswith oddsratio calculations).A high decision

latitude protected statistically against worsening depres-

sive symptoms– with a weighted oddsratio of 0.73

(95 % CI 0.68 to 0.77).Bullying had been studied in 15

173 subjectsin three studies.One of thesestudies

showed results for men and women separately.Despite

the relativelysmall numberof studies,bullyingwas

judged to be related to worsening depressive symptoms

with an evidence grade of3 as the findings were very

consistentand the odds ratios were high (the weighted

odds ratio being 2.82;95 % CI 2.21 to 3.59).

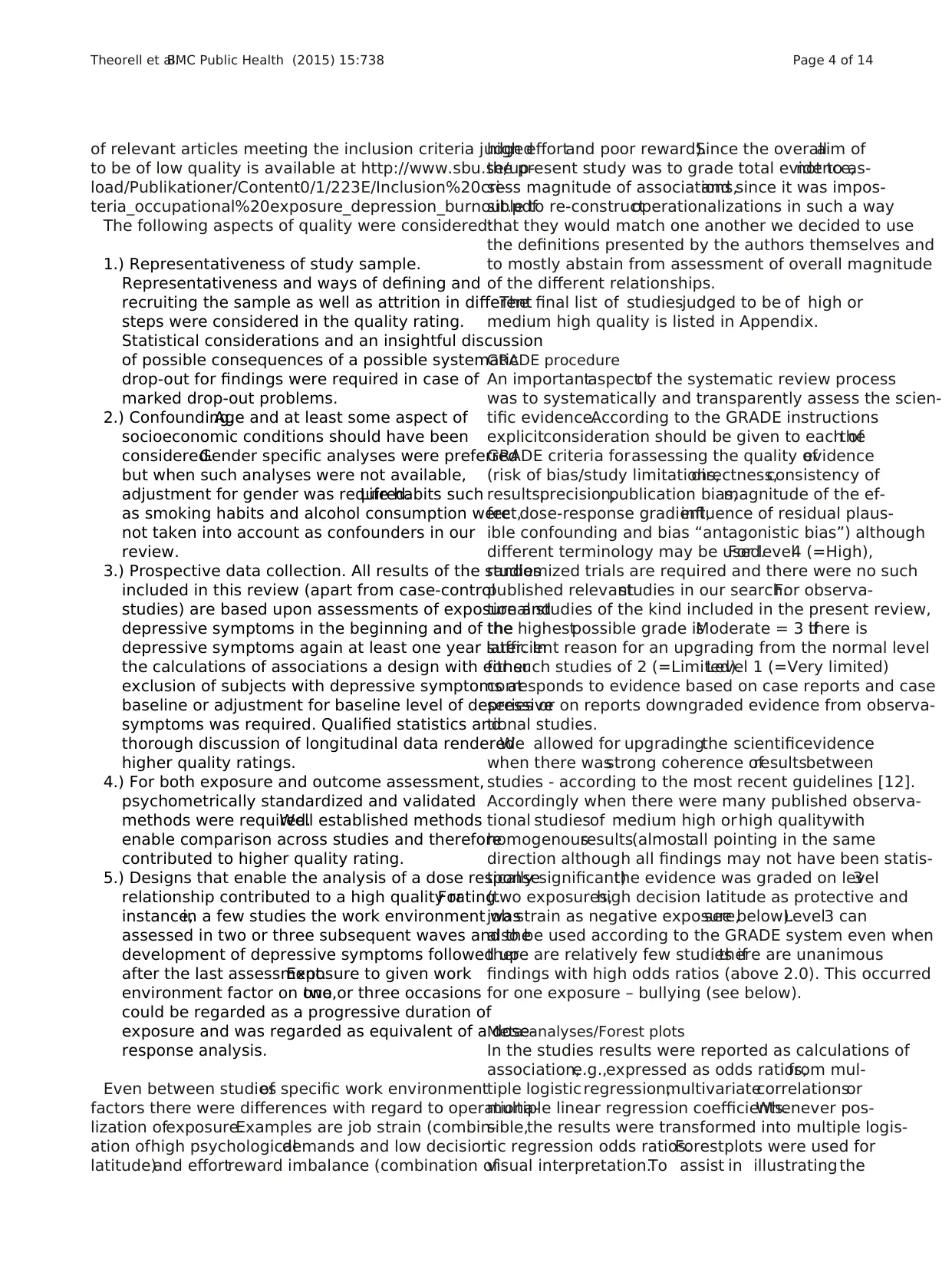

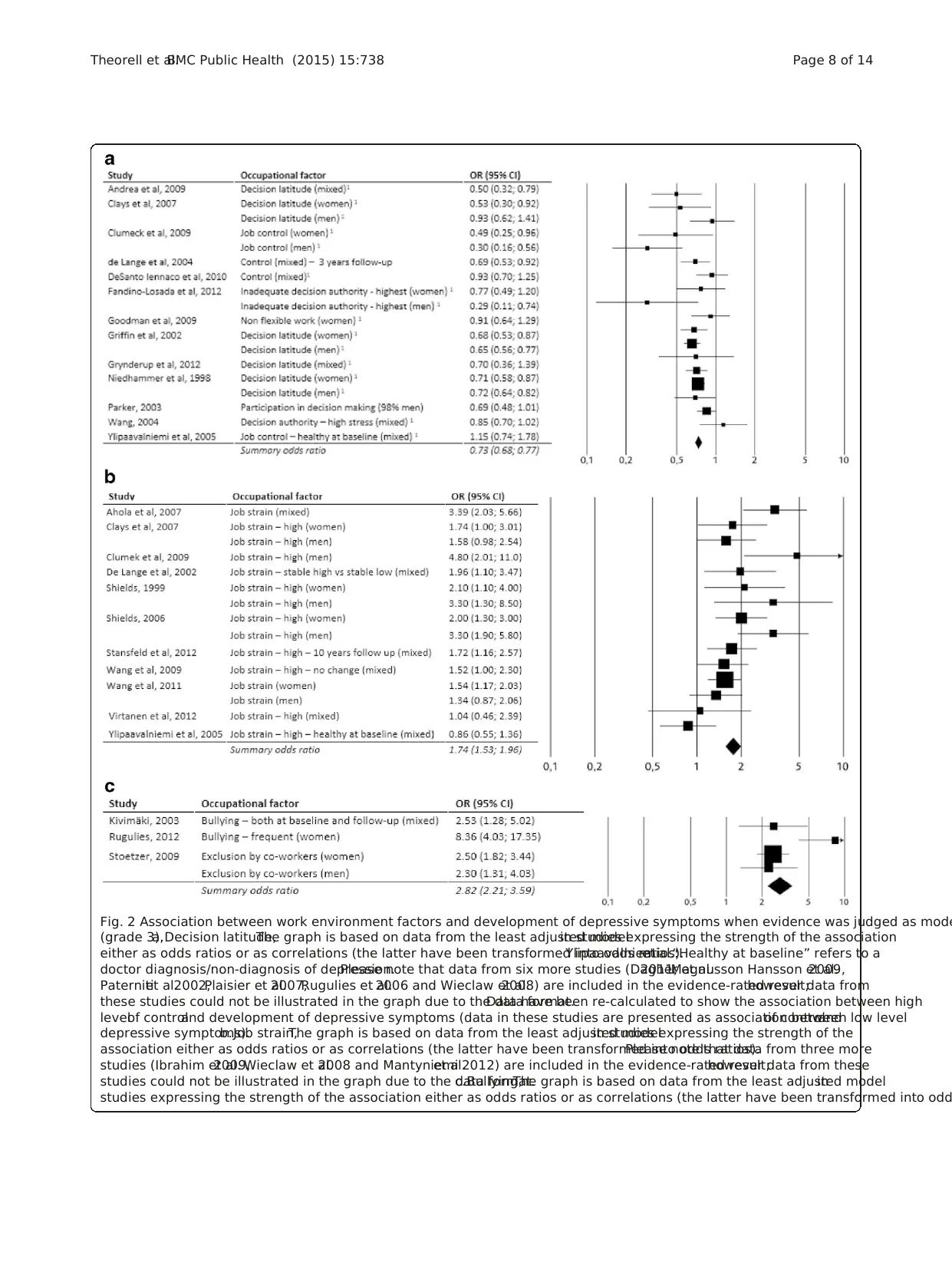

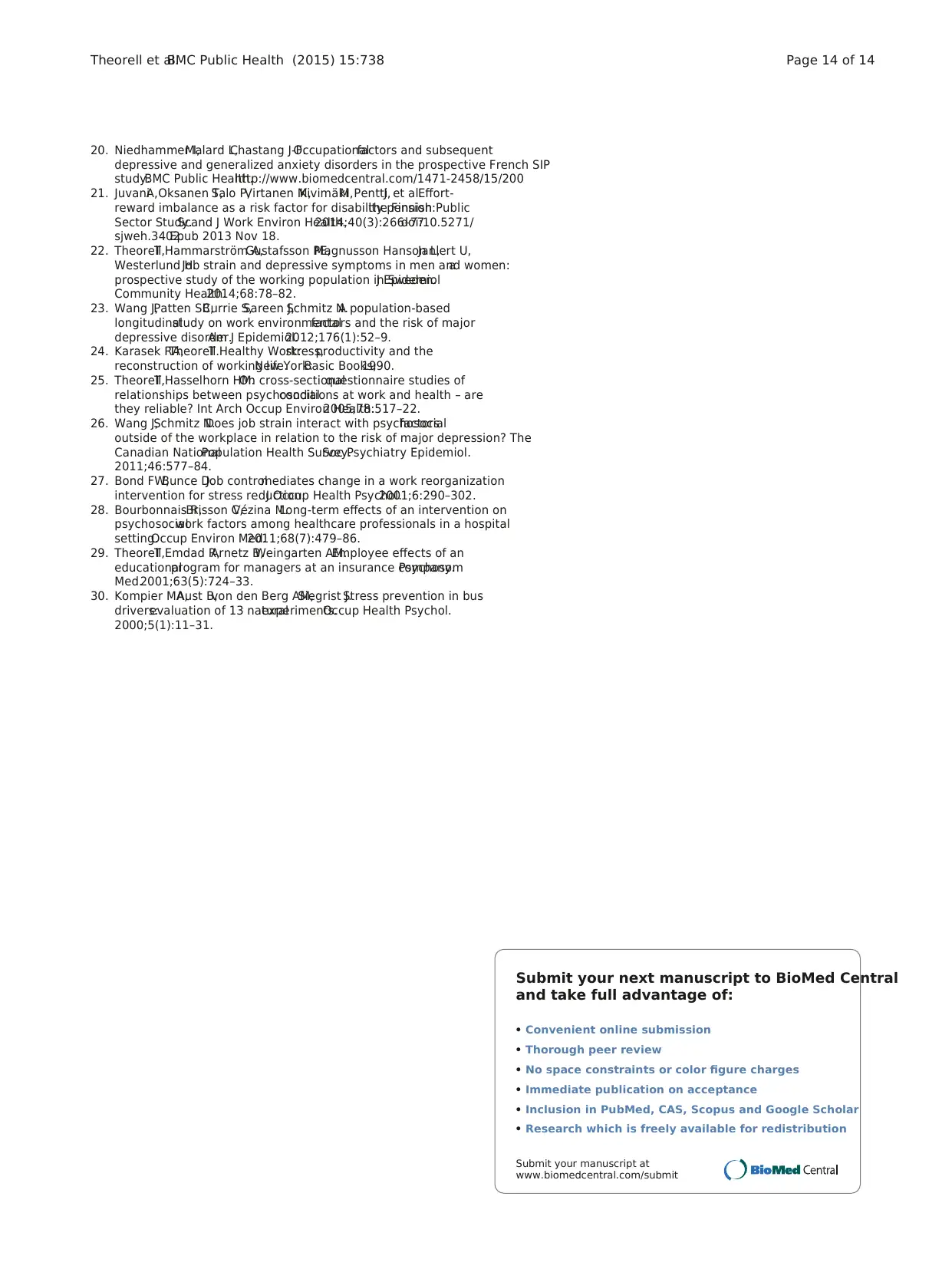

Figure 2 shows forest plots for the three factors with

evidence grade 3 - decision latitude (a),job strain (b)

and bullying (c).For high decision latitude,17/18 point

estimates were lower than 1.0 (separate point estimates

for men and women in five studies).The upper 95 %

confidence limitwas above 1.0 in five studies.For job

strain,14/15 pointestimateswere above1.0. Three

lower confidence limits reached below 1.0.The forest

plots were based upon studies from which odds ratios

could be extracted or calculated.It should be pointed

out, however,that the total evidencegradingalso

included a few additionalstudies.Bullying,finally,had

four pointestimates in the diagram.All of those were

higher than 2.0 and all the lower confidence limits were

above 1.0.

The exposures with a limited levelof evidence were

psychologicaldemands (quantitativepsychological

demandsdefined accordingto the widely used Job

ContentQuestionnaire oralternative psychometrically

tested versions),the combination oflow psychological

demandsand low decision latitude(“passivework”),

“pressing work” (mainly important life events at work),

effort reward imbalance,low social support (from

management and coworkers),poor socialclimate,poor

social capital,low proceduraland relationaljustice,

conflicts with superiorsand colleagues,poor skill

discretion,job insecurity and long working weeks (the

latter for women only).

The exposures with very limited (= level1) evidence

were other kinds of demands (not quantitative) including

emotionaldemands,distributivejustice,threats,vio-

lence,irregularworking hours, long working hours

(men),physically demanding work,exposure to pesti-

cides and insecticides,solvents and heavy metals.

Homogeneity tests showed thatresults were compar-

able for two groups ofoutcome measures (standardized

interview versus standardized self-report questionnaire),

for men and women,for generalpopulation versus spe-

cific occupation cohorts and for white collar versus blue

collar groups.

Discussion

Main findings and recent developments in the field

The aim of the studywas to provide systematically

graded evidence for possible associations between work

environment factors and near-future development of de-

pressive symptoms.A totalof fifty-nine relevant articles

with high or medium high scientific quality fulfilling our

criteria were found.The resultsprovide evidence for

several work conditions being linked to depressive symp-

toms among the employees in both positive and negative

directions.Scientific evidence of grade three out of four

(in other words moderately strong)was shown for job

strain (high psychologicaldemandsand low decision

latitude),low decision latitudeand bullying.Further-

more,scientific evidence ofgrade two wasfound for

psychologicaldemands,effort reward imbalance,low

support,unfavorable socialclimate,lack of procedural

and relationaljustice,conflicts with superiors and col-

leagues,limited skilldiscretion,job insecurity and long

working week.

An important finding is that there were few prospect-

ive studies with sufficient quality of the relationship be-

tween adverse chemical(pesticides and heavy metals for

instance)and physical(heavy loads,awkward positions,

irradiation,cold and hot temperature)and depressive

symptoms.This field needs more research.

The results should primarily be interpreted in the con-

textof the Western world.We deliberately limited our

inclusion of studies to these countries.The rationale be-

hind this was that we wanted to secure similar cultural

framework around work in order to simplify our inter-

pretation of the findings.

The review differs from earlier studies in the field due

to its comprehensive and thorough approach.Our re-

view is based on an extremely thorough literature search

as wellas on a well-described and systematic evaluation

of a large number ofpublications.Thus,it includes all

kinds of environmentalexposures,physicalas well as

psychosocialand that it is based upon a systematic ap-

proach.This is the first review in which the examination

of evidence follows(a slightmodification of )GRADE

principles.Furthermoreit is including morerecently

published research than previous reviews.

Our review shows that the psychosocialresearch field

has made progress since the reviews published in 2008

and 2010.Bonde [1]and Netterström etal. [2] made

criticalremarks aboutpossible publication bias,lack of

more “objective” measures of exposure and outcome and

also aboutlack of time perspectiveswhich would be

needed for the understanding of time of exposure needed

for the development of depression.With regard to object-

ive measures,thereare more publishedstudiesthan

previously with standardized interview based assessment o

clinical depression.Comparison of the plots corresponding

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 7 of 14

(197 682 subjects in 14 studies).It was possible to com-

pute a weighted odds ratio 1.74 (95 % CI 1.54 to 1.96 for

studieswith oddsratio calculations).A high decision

latitude protected statistically against worsening depres-

sive symptoms– with a weighted oddsratio of 0.73

(95 % CI 0.68 to 0.77).Bullying had been studied in 15

173 subjectsin three studies.One of thesestudies

showed results for men and women separately.Despite

the relativelysmall numberof studies,bullyingwas

judged to be related to worsening depressive symptoms

with an evidence grade of3 as the findings were very

consistentand the odds ratios were high (the weighted

odds ratio being 2.82;95 % CI 2.21 to 3.59).

Figure 2 shows forest plots for the three factors with

evidence grade 3 - decision latitude (a),job strain (b)

and bullying (c).For high decision latitude,17/18 point

estimates were lower than 1.0 (separate point estimates

for men and women in five studies).The upper 95 %

confidence limitwas above 1.0 in five studies.For job

strain,14/15 pointestimateswere above1.0. Three

lower confidence limits reached below 1.0.The forest

plots were based upon studies from which odds ratios

could be extracted or calculated.It should be pointed

out, however,that the total evidencegradingalso

included a few additionalstudies.Bullying,finally,had

four pointestimates in the diagram.All of those were

higher than 2.0 and all the lower confidence limits were

above 1.0.

The exposures with a limited levelof evidence were

psychologicaldemands (quantitativepsychological

demandsdefined accordingto the widely used Job

ContentQuestionnaire oralternative psychometrically

tested versions),the combination oflow psychological

demandsand low decision latitude(“passivework”),

“pressing work” (mainly important life events at work),

effort reward imbalance,low social support (from

management and coworkers),poor socialclimate,poor

social capital,low proceduraland relationaljustice,

conflicts with superiorsand colleagues,poor skill

discretion,job insecurity and long working weeks (the

latter for women only).

The exposures with very limited (= level1) evidence

were other kinds of demands (not quantitative) including

emotionaldemands,distributivejustice,threats,vio-

lence,irregularworking hours, long working hours

(men),physically demanding work,exposure to pesti-

cides and insecticides,solvents and heavy metals.

Homogeneity tests showed thatresults were compar-

able for two groups ofoutcome measures (standardized

interview versus standardized self-report questionnaire),

for men and women,for generalpopulation versus spe-

cific occupation cohorts and for white collar versus blue

collar groups.

Discussion

Main findings and recent developments in the field

The aim of the studywas to provide systematically

graded evidence for possible associations between work

environment factors and near-future development of de-

pressive symptoms.A totalof fifty-nine relevant articles

with high or medium high scientific quality fulfilling our

criteria were found.The resultsprovide evidence for

several work conditions being linked to depressive symp-

toms among the employees in both positive and negative

directions.Scientific evidence of grade three out of four

(in other words moderately strong)was shown for job

strain (high psychologicaldemandsand low decision

latitude),low decision latitudeand bullying.Further-

more,scientific evidence ofgrade two wasfound for

psychologicaldemands,effort reward imbalance,low

support,unfavorable socialclimate,lack of procedural

and relationaljustice,conflicts with superiors and col-

leagues,limited skilldiscretion,job insecurity and long

working week.

An important finding is that there were few prospect-

ive studies with sufficient quality of the relationship be-

tween adverse chemical(pesticides and heavy metals for

instance)and physical(heavy loads,awkward positions,

irradiation,cold and hot temperature)and depressive

symptoms.This field needs more research.

The results should primarily be interpreted in the con-

textof the Western world.We deliberately limited our

inclusion of studies to these countries.The rationale be-

hind this was that we wanted to secure similar cultural

framework around work in order to simplify our inter-

pretation of the findings.

The review differs from earlier studies in the field due

to its comprehensive and thorough approach.Our re-

view is based on an extremely thorough literature search

as wellas on a well-described and systematic evaluation

of a large number ofpublications.Thus,it includes all

kinds of environmentalexposures,physicalas well as

psychosocialand that it is based upon a systematic ap-

proach.This is the first review in which the examination

of evidence follows(a slightmodification of )GRADE

principles.Furthermoreit is including morerecently

published research than previous reviews.

Our review shows that the psychosocialresearch field

has made progress since the reviews published in 2008

and 2010.Bonde [1]and Netterström etal. [2] made

criticalremarks aboutpossible publication bias,lack of

more “objective” measures of exposure and outcome and

also aboutlack of time perspectiveswhich would be

needed for the understanding of time of exposure needed

for the development of depression.With regard to object-

ive measures,thereare more publishedstudiesthan

previously with standardized interview based assessment o

clinical depression.Comparison of the plots corresponding

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 7 of 14

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Fig. 2 Association between work environment factors and development of depressive symptoms when evidence was judged as mode

(grade 3),a.Decision latitude,The graph is based on data from the least adjusted modelin studies expressing the strength of the association

either as odds ratios or as correlations (the latter have been transformed into odds ratios).Ylipaavalniemiet al.:“Healthy at baseline” refers to a

doctor diagnosis/non-diagnosis of depression.Please note that data from six more studies (Dagher et al.2011,Magnusson Hansson et al.2009,

Paternitiet al.2002,Plaisier et al.2007,Rugulies et al.2006 and Wieclaw et al.2008) are included in the evidence-rated result;however data from

these studies could not be illustrated in the graph due to the data format.Data have been re-calculated to show the association between high

levelof controland development of depressive symptoms (data in these studies are presented as association between low levelof controland

depressive symptoms).b.Job strain,The graph is based on data from the least adjusted modelin studies expressing the strength of the

association either as odds ratios or as correlations (the latter have been transformed into odds ratios).Please note that data from three more

studies (Ibrahim et al.2009,Wieclaw et al.2008 and Mantyniemiet al.2012) are included in the evidence-rated result;however data from these

studies could not be illustrated in the graph due to the data format.c.Bullying,The graph is based on data from the least adjusted modelin

studies expressing the strength of the association either as odds ratios or as correlations (the latter have been transformed into odd

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 8 of 14

(grade 3),a.Decision latitude,The graph is based on data from the least adjusted modelin studies expressing the strength of the association

either as odds ratios or as correlations (the latter have been transformed into odds ratios).Ylipaavalniemiet al.:“Healthy at baseline” refers to a

doctor diagnosis/non-diagnosis of depression.Please note that data from six more studies (Dagher et al.2011,Magnusson Hansson et al.2009,

Paternitiet al.2002,Plaisier et al.2007,Rugulies et al.2006 and Wieclaw et al.2008) are included in the evidence-rated result;however data from

these studies could not be illustrated in the graph due to the data format.Data have been re-calculated to show the association between high

levelof controland development of depressive symptoms (data in these studies are presented as association between low levelof controland

depressive symptoms).b.Job strain,The graph is based on data from the least adjusted modelin studies expressing the strength of the

association either as odds ratios or as correlations (the latter have been transformed into odds ratios).Please note that data from three more

studies (Ibrahim et al.2009,Wieclaw et al.2008 and Mantyniemiet al.2012) are included in the evidence-rated result;however data from these

studies could not be illustrated in the graph due to the data format.c.Bullying,The graph is based on data from the least adjusted modelin

studies expressing the strength of the association either as odds ratios or as correlations (the latter have been transformed into odd

Theorell et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:738 Page 8 of 14

to results from studies based upon standardized interviews

did not differ from those from studies based upon inter-

nationallyaccepted depression questionnaires.Objective

exposures are stilluncommon,however.One interesting

approach was used by Virtanen et al.[13] who could show

thathospitalstaffwho experienced excess occupancy of

hospital beds had increased risk of developing sick leave be-

cause of depression in a dose-response manner, with excess

occupancy exceeding 10 % being associated with an odds

ratio of sick leave for depression of 1.94 (1.14-3.28).

During later years research designs on the association

between work environmentfactors and depressive feel-

ings havebecomeincreasinglysophisticated.For in-

stance,Shields [14],Stansfeld et al.[15],De Lange et al.

[16] and Wang et al.[17] have examined possible effects

of exposure to job strain atleasttwice,or even three

times in the follow-up survey waves.Their findings indi-

catethat accumulated orincreasing job strain hasa

stronger adverse statisticaleffect on risk of experiencing

increased ratings of depressive symptoms during follow-

up than decreasing job strain.As mightbe expected,

these studies show that two or more assessments of the

job situation provide more precise information regarding

risk than only one measurement.Therefore stronger evi-

dence regarding the influence ofworking conditions on

mentalhealth may be expected in future research with a

growing body of studies with such methodology.

The literature search included articles published up to

June 2013.For practicalreasons it has not been possible

to do a full review of the articles published after that date.

However,a more informalsearch in the scientific litera-

ture (PubMed and PsycInfo untilFebruary 2015) showed

that a few more recent prospective studies of work envir-

onmentand development ofdepressive feelings relevant

to the present review have been published.None of those

would have changed our conclusions.Four ofthem sup-

port the use of standardized measures of job strain or high

psychologicaldemands and low decision latitude in pre-

dicting either depressive symptoms or major depressive

disorder [18–21] and one of them supports the use of ef-

fort reward imbalance (or low reward) in the prediction of

disability pension due to depression [21].

Gender

Our results showed thatsimilar work conditions were

related to asimilarincreasein depressivesymptoms

among men and women.However,although there is no

gender difference in excess risk associated with adverse

work conditions,studies have shown that women actu-

ally have higher levels ofjob strain than men [22].This

may be one reason for women’s higher prevalence of de-

pressivesymptoms.Other studiesindicatethat work

conditions can affect men and women differently in rela-

tion to developmentof major depressivedisorder

(MDD). For example,a Canadian studyshowed that

men had elevated risk of MDD only if they were exposed

to extremely high levelof job strain while women had

elevated risk ofMDD even when exposed to moderate

job strain [23].The study points to the need of context-

ualizing findings aboutmentalhealth and itmay also

illustrate thatgendercould be more relevantfor the

relationshipbetweenworking conditionsand major

depressive disorderthan for the relationship between

working conditions and depressive symptoms.

Technical issues

In this review we have notreviewed evidence whether

there is interaction ornot between high psychological

demands and low decision latitude (as discussed for in-

stance in Karasek and Theorell[24]).We have regarded

the combination simplyas a theoreticalconstruction

and evaluated its possible success or lack of success as a

predictor of development of depressive symptoms.

In forest plots,we chose to use data from the least ad-

justed model from each study.The main rationale for this

was thatthese models were more comparable between

studies than other models,since the more adjusted ones

were adjusted to widely differentpotentialconfounders.

The most powerful prognostic factor for incident depres-

sive symptoms was manifest symptoms at the study base-

line;a parameter that had to be assessed in each ofthe

includedstudies.Generally,adjustingfor other con-

founders had very little effect.For transparency,we have

listed data in both least and most adjusted models, see ex-

tensive tables at http://www.sbu.se/upload/Publikationer/

Content0/1/223E/Inclusion%20criteria_occupational%20

exposure_depression_burnout.pdf.

An important point is that ifa study presented data in

several statistical models,all data from all models were in-

cluded in the expert group assessment of scientific evidenc

for all of the results presented in this systematic review.

Assessments ofodds ratios may be somewhatunreli-

able due to differencesin methodology acrossstudies