HLSC122: EBP Critical Appraisal - Stroke Rehabilitation Case

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|13

|9741

|459

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study critically appraises a research paper related to supporting a stroke patient's activities of daily living, fulfilling the requirements for HLSC122: Evidence for Practice. The assignment involves a critical evaluation of a research article focusing on evidence-based practice (EBP) in physiotherapy, specifically within the context of stroke rehabilitation. It synthesizes findings on barriers, enablers, and interventions related to EBP implementation by physiotherapists. The study uses a systematic review approach, examining literature from 2000-2012, and involves data extraction, synthesis, and quality appraisal of included articles, highlighting key themes such as attitudes, knowledge, skills, and barriers to EBP adoption. The ultimate goal is to identify methods for enhancing the consistency and quality of EBP implementation in physiotherapy practice.

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached

copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research

and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/authorsrights

copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research

and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/authorsrights

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Author's personal copy

Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

Systematic review

Evidence-Based Practice in physiotherapy: a systematic

review of barriers, enablers and interventions

Laura Scurlock-Evansa,∗, Penney Upton b, Dominic Upton c

a Psychological Sciences, Institute of Health and Society, University of Worcester,Henwick Grove, Worcester WR2 6AJ, UK

b Institute of Health and Society, University of Worcester,Henwick Grove, Worcester WR2 6AJ, UK

c Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, University Dr, Bruce ACT 2617, Australia

Abstract

Background Despite clear benefits of the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) approach to ensuring quality and consistency of care, its uptake

within physiotherapy has been inconsistent.

Objectives Synthesise the findings of research into EBP barriers, facilitators and interventions in physiotherapy and identify methods of

enhancing adoption and implementation.

Data sources Literature concerning physiotherapists’ practice between 2000 and 2012 was systematically searched using: Academic Search

Complete, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature Plus, American Psychological Association databases, Medline, Journal

Storage, and Science Direct. Reference lists were searched to identify additional studies.

Study selection Thirty-two studies, focusing either on physiotherapists’ EBP knowledge, attitudes or implementation, or EBP interventions

in physiotherapy were included.

Data extraction and synthesis One author undertook all data extraction and a second author reviewed to ensure consistency and rigour.

Synthesis was organised around the themes of EBP barriers/enablers, attitudes, knowledge/skills, use and interventions.

Results Many physiotherapists hold positive attitudes towards EBP. However, this does not necessarily translate into consistent, high-quality

EBP. Many barriers to EBP implementation are apparent, including: lack of time and skills, and misperceptions of EBP.

Limitations Only studies published in the English language, in peer-reviewed journals were included, thereby introducing possible publication

bias. Furthermore, narrative synthesis may be subject to greater confirmation bias.

Conclusion and implications There is no “one-size fits all” approach to enhancing EBP implementation; assessing organisational culture

prior to designing interventions is crucial. Although some interventions appear promising, further research is required to explore the most

effective methods of supporting physiotherapists’ adoption of EBP.

© 2014 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Evidence-Based Practice; Physiotherapists; Best Practices; Review; Decision Making; Practice-Research Gap

Background

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is a 5 step process

whereby clinicians integrate best research evidence with clin-

ical expertise and client preferences, producing the most

appropriate and effective service [1,2]. As a result there has

been growing pressure on physiotherapy to embrace EBP

[3]. Engaging with both research and clinical findings can

enhance the proficiency of physiotherapists’ clinical practice

∗ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: l.scurlock-evans@worc.ac.uk (L. Scurlock-Evans).

[2] and help prevent the misuse, overuse and underuse of

healthcare services [4]. In an era of growing accountability

of healthcare practitioners, this may provide a useful frame-

work within which to work. Indeed, this has led some to argue

that there is a moral obligation to base decision-making on

research findings [3].

Despite the clear benefits of EBP, its uptake within phys-

iotherapy (and other healthcare domains) has been patchy

and inconsistent in quality [5]. Concerns over the compat-

ibility of aspects of EBP and lack of clinically relevant

research [3,6], have been raised by researchers and clinicians

alike.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2014.03.001

0031-9406/© 2014 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

Systematic review

Evidence-Based Practice in physiotherapy: a systematic

review of barriers, enablers and interventions

Laura Scurlock-Evansa,∗, Penney Upton b, Dominic Upton c

a Psychological Sciences, Institute of Health and Society, University of Worcester,Henwick Grove, Worcester WR2 6AJ, UK

b Institute of Health and Society, University of Worcester,Henwick Grove, Worcester WR2 6AJ, UK

c Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, University Dr, Bruce ACT 2617, Australia

Abstract

Background Despite clear benefits of the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) approach to ensuring quality and consistency of care, its uptake

within physiotherapy has been inconsistent.

Objectives Synthesise the findings of research into EBP barriers, facilitators and interventions in physiotherapy and identify methods of

enhancing adoption and implementation.

Data sources Literature concerning physiotherapists’ practice between 2000 and 2012 was systematically searched using: Academic Search

Complete, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature Plus, American Psychological Association databases, Medline, Journal

Storage, and Science Direct. Reference lists were searched to identify additional studies.

Study selection Thirty-two studies, focusing either on physiotherapists’ EBP knowledge, attitudes or implementation, or EBP interventions

in physiotherapy were included.

Data extraction and synthesis One author undertook all data extraction and a second author reviewed to ensure consistency and rigour.

Synthesis was organised around the themes of EBP barriers/enablers, attitudes, knowledge/skills, use and interventions.

Results Many physiotherapists hold positive attitudes towards EBP. However, this does not necessarily translate into consistent, high-quality

EBP. Many barriers to EBP implementation are apparent, including: lack of time and skills, and misperceptions of EBP.

Limitations Only studies published in the English language, in peer-reviewed journals were included, thereby introducing possible publication

bias. Furthermore, narrative synthesis may be subject to greater confirmation bias.

Conclusion and implications There is no “one-size fits all” approach to enhancing EBP implementation; assessing organisational culture

prior to designing interventions is crucial. Although some interventions appear promising, further research is required to explore the most

effective methods of supporting physiotherapists’ adoption of EBP.

© 2014 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Evidence-Based Practice; Physiotherapists; Best Practices; Review; Decision Making; Practice-Research Gap

Background

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is a 5 step process

whereby clinicians integrate best research evidence with clin-

ical expertise and client preferences, producing the most

appropriate and effective service [1,2]. As a result there has

been growing pressure on physiotherapy to embrace EBP

[3]. Engaging with both research and clinical findings can

enhance the proficiency of physiotherapists’ clinical practice

∗ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: l.scurlock-evans@worc.ac.uk (L. Scurlock-Evans).

[2] and help prevent the misuse, overuse and underuse of

healthcare services [4]. In an era of growing accountability

of healthcare practitioners, this may provide a useful frame-

work within which to work. Indeed, this has led some to argue

that there is a moral obligation to base decision-making on

research findings [3].

Despite the clear benefits of EBP, its uptake within phys-

iotherapy (and other healthcare domains) has been patchy

and inconsistent in quality [5]. Concerns over the compat-

ibility of aspects of EBP and lack of clinically relevant

research [3,6], have been raised by researchers and clinicians

alike.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2014.03.001

0031-9406/© 2014 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Author's personal copy

L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219 209

Objectives

Research has identified a number of challenges phy-

siotherapists face when implementing EBP [6], which are

sometimes inconsistent. This review aimed to synthesise

research findings regarding barriers and enablers of EBP, and

the effectiveness of current EBP interventions in physiother-

apy, to help identify methods of increasing the consistency

and quality of EBP implementation.

Method

The review followed the PRISMA guidelines [7] for

reporting systematic reviews. A narrative analysis approach

was adopted, whereby text is used to summarise and explain

review synthesis findings, as it is suitably flexible to allow

for the inclusion of diverse methodologies.

Data sources

Literature concerning physiotherapists’ practice between

2000 and 2012 was systematically searched using free-text

keywords and MeSH or equivalent terms in combination (see

Table S1). Reference lists were searched to identify additional

studies.

Study selection

Articles were initially reviewed according to the following

inclusion criteria;

• Published in a peer-reviewed journal in English;

• Published between 2002 and 2012;

• Primary research conducted with qualified physiothera-

pists;

• Focused on at least one of the following;

- Physiotherapists’ knowledge/understanding of EBP

- Physiotherapists’ attitudes towards EBP

- Physiotherapists’ practice/implementation of EBP.

- EBP interventions in Physiotherapy.

To enhance comparability of researching findings, only

studies from the following Western cultures/regions were

included: UK, Ireland, Europe, USA, Canada, Australia and

New Zealand.

In total, 32 articles were retrieved that met the criteria; 27

used a quantitative method, 3 used a qualitative method and 2

used mixed-methods designs. A flow chart of study retrieval

and selection is presented in Fig. S1.

Data extraction and synthesis

One author undertook all data extraction using a

pre-defined template, and a second reviewed to ensure

consistency and rigour. Synthesis was organised around the

themes of EBP barriers/enablers, attitudes, knowledge/skills,

use and interventions.

Quality appraisal

Quantitative articles were assessed using the Effective

Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP; [8]) tool: each study

was rated as strong, moderate or weak (see Table 1). Quali-

tative articles were appraised using the consolidated criteria

for reporting qualitative research (COREQ; [9]), modified

to rate articles as strong, moderate or weak. Mixed-methods

research was evaluated using both tools.

Results

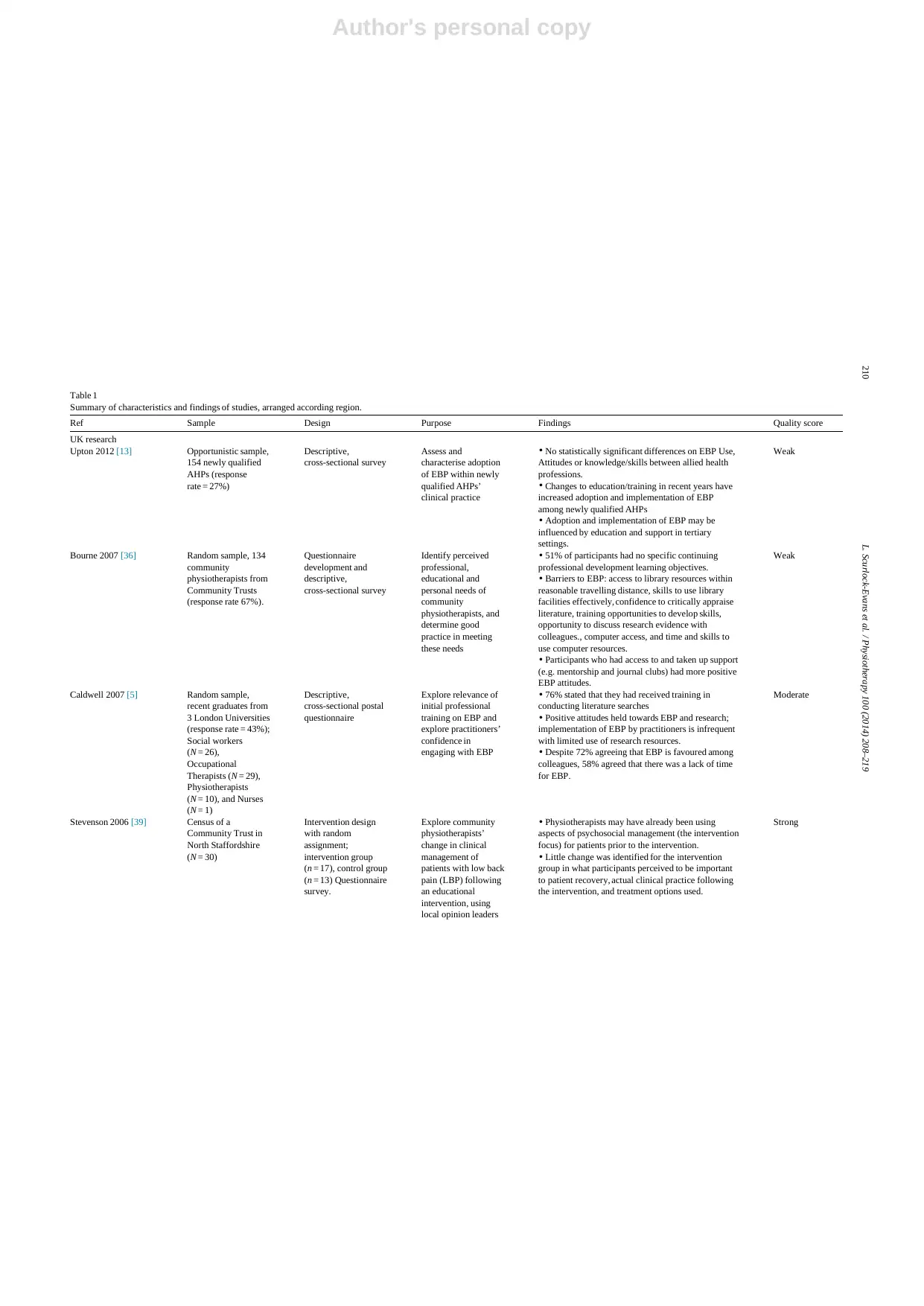

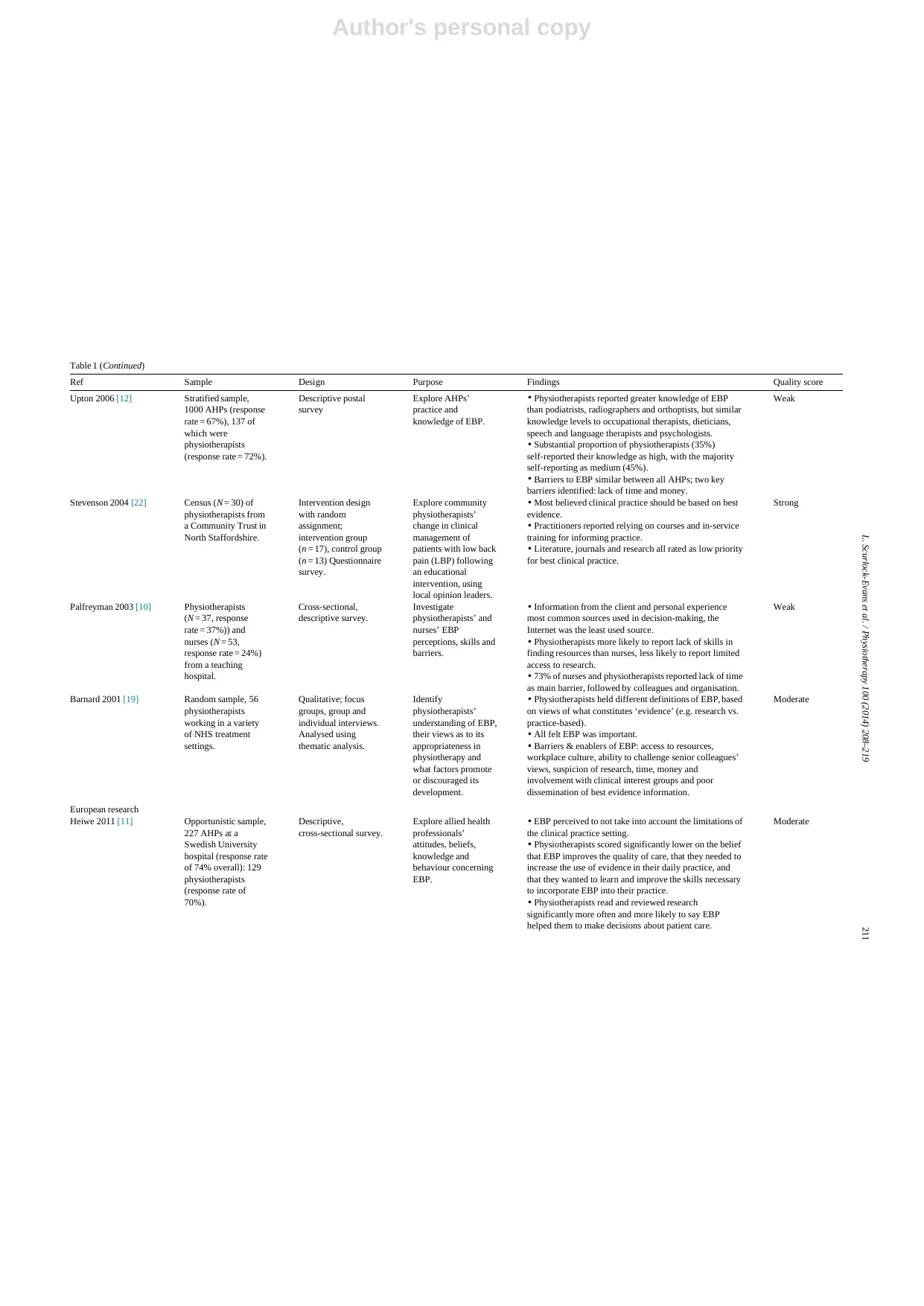

Despite known variations between countries’ healthcare

provision a number of key themes were evident, suggesting

they represent factors common to the practice of physiother-

apy across contexts; as there were no obvious systematic

differences in the characteristics of the research across

regions or publication date, the results were structured around

these themes. However, to aid with interpretation Table 1

presents studies’ characteristics and findings by region and

date.

Practice of EBP

Some studies compared physiotherapists’ practice of

EBP with professionals’ from other healthcare domains.

Palfreyman et al. [10] found that although both nurses

and physiotherapists had access to a broad range of EBP

knowledge sources, physiotherapists used such sources and

implemented EBP more frequently. However, both pro-

fessions relied significantly on patients and colleagues as

knowledge sources.

In a study comparing Swedish physiotherapists, dieti-

cians and occupational therapists, physiotherapists read and

reviewed research more often and were more likely to say

EBP helped them with decision-making [11]. Complex dif-

ferences between physiotherapists’ and other allied health

professionals’ (AHPs) were identified in a UK sample [12];

physiotherapists outperformed on some aspects, such as iden-

tifying relevant research, but performed less well on others,

such as identifying knowledge-gaps. However, other research

with UK-based AHPs (physiotherapists, speech and language

therapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, radiographers

and podiatrists) found no statistically significant differences

in EBP implementation, attitudes, or knowledge and skills

[13]. These discrepancies may be explained by differences

in level of academic preparation and access to educational

initiatives (e.g. all professionals in [13]’s study had

access to a professional development programme, poten-

tially increasing consistency in EBP), and changes to EBP

teaching.

L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219 209

Objectives

Research has identified a number of challenges phy-

siotherapists face when implementing EBP [6], which are

sometimes inconsistent. This review aimed to synthesise

research findings regarding barriers and enablers of EBP, and

the effectiveness of current EBP interventions in physiother-

apy, to help identify methods of increasing the consistency

and quality of EBP implementation.

Method

The review followed the PRISMA guidelines [7] for

reporting systematic reviews. A narrative analysis approach

was adopted, whereby text is used to summarise and explain

review synthesis findings, as it is suitably flexible to allow

for the inclusion of diverse methodologies.

Data sources

Literature concerning physiotherapists’ practice between

2000 and 2012 was systematically searched using free-text

keywords and MeSH or equivalent terms in combination (see

Table S1). Reference lists were searched to identify additional

studies.

Study selection

Articles were initially reviewed according to the following

inclusion criteria;

• Published in a peer-reviewed journal in English;

• Published between 2002 and 2012;

• Primary research conducted with qualified physiothera-

pists;

• Focused on at least one of the following;

- Physiotherapists’ knowledge/understanding of EBP

- Physiotherapists’ attitudes towards EBP

- Physiotherapists’ practice/implementation of EBP.

- EBP interventions in Physiotherapy.

To enhance comparability of researching findings, only

studies from the following Western cultures/regions were

included: UK, Ireland, Europe, USA, Canada, Australia and

New Zealand.

In total, 32 articles were retrieved that met the criteria; 27

used a quantitative method, 3 used a qualitative method and 2

used mixed-methods designs. A flow chart of study retrieval

and selection is presented in Fig. S1.

Data extraction and synthesis

One author undertook all data extraction using a

pre-defined template, and a second reviewed to ensure

consistency and rigour. Synthesis was organised around the

themes of EBP barriers/enablers, attitudes, knowledge/skills,

use and interventions.

Quality appraisal

Quantitative articles were assessed using the Effective

Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP; [8]) tool: each study

was rated as strong, moderate or weak (see Table 1). Quali-

tative articles were appraised using the consolidated criteria

for reporting qualitative research (COREQ; [9]), modified

to rate articles as strong, moderate or weak. Mixed-methods

research was evaluated using both tools.

Results

Despite known variations between countries’ healthcare

provision a number of key themes were evident, suggesting

they represent factors common to the practice of physiother-

apy across contexts; as there were no obvious systematic

differences in the characteristics of the research across

regions or publication date, the results were structured around

these themes. However, to aid with interpretation Table 1

presents studies’ characteristics and findings by region and

date.

Practice of EBP

Some studies compared physiotherapists’ practice of

EBP with professionals’ from other healthcare domains.

Palfreyman et al. [10] found that although both nurses

and physiotherapists had access to a broad range of EBP

knowledge sources, physiotherapists used such sources and

implemented EBP more frequently. However, both pro-

fessions relied significantly on patients and colleagues as

knowledge sources.

In a study comparing Swedish physiotherapists, dieti-

cians and occupational therapists, physiotherapists read and

reviewed research more often and were more likely to say

EBP helped them with decision-making [11]. Complex dif-

ferences between physiotherapists’ and other allied health

professionals’ (AHPs) were identified in a UK sample [12];

physiotherapists outperformed on some aspects, such as iden-

tifying relevant research, but performed less well on others,

such as identifying knowledge-gaps. However, other research

with UK-based AHPs (physiotherapists, speech and language

therapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, radiographers

and podiatrists) found no statistically significant differences

in EBP implementation, attitudes, or knowledge and skills

[13]. These discrepancies may be explained by differences

in level of academic preparation and access to educational

initiatives (e.g. all professionals in [13]’s study had

access to a professional development programme, poten-

tially increasing consistency in EBP), and changes to EBP

teaching.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Author's personal copy

210 L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

Table 1

Summary of characteristics and findings of studies, arranged according region.

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

UK research

Upton 2012 [13] Opportunistic sample,

154 newly qualified

AHPs (response

rate = 27%)

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey

Assess and

characterise adoption

of EBP within newly

qualified AHPs’

clinical practice

• No statistically significant differences on EBP Use,

Attitudes or knowledge/skills between allied health

professions.

• Changes to education/training in recent years have

increased adoption and implementation of EBP

among newly qualified AHPs

• Adoption and implementation of EBP may be

influenced by education and support in tertiary

settings.

Weak

Bourne 2007 [36] Random sample, 134

community

physiotherapists from

Community Trusts

(response rate 67%).

Questionnaire

development and

descriptive,

cross-sectional survey

Identify perceived

professional,

educational and

personal needs of

community

physiotherapists, and

determine good

practice in meeting

these needs

• 51% of participants had no specific continuing

professional development learning objectives.

• Barriers to EBP: access to library resources within

reasonable travelling distance, skills to use library

facilities effectively, confidence to critically appraise

literature, training opportunities to develop skills,

opportunity to discuss research evidence with

colleagues., computer access, and time and skills to

use computer resources.

• Participants who had access to and taken up support

(e.g. mentorship and journal clubs) had more positive

EBP attitudes.

Weak

Caldwell 2007 [5] Random sample,

recent graduates from

3 London Universities

(response rate = 43%);

Social workers

(N = 26),

Occupational

Therapists (N = 29),

Physiotherapists

(N = 10), and Nurses

(N = 1)

Descriptive,

cross-sectional postal

questionnaire

Explore relevance of

initial professional

training on EBP and

explore practitioners’

confidence in

engaging with EBP

• 76% stated that they had received training in

conducting literature searches

• Positive attitudes held towards EBP and research;

implementation of EBP by practitioners is infrequent

with limited use of research resources.

• Despite 72% agreeing that EBP is favoured among

colleagues, 58% agreed that there was a lack of time

for EBP.

Moderate

Stevenson 2006 [39] Census of a

Community Trust in

North Staffordshire

(N = 30)

Intervention design

with random

assignment;

intervention group

(n = 17), control group

(n = 13) Questionnaire

survey.

Explore community

physiotherapists’

change in clinical

management of

patients with low back

pain (LBP) following

an educational

intervention, using

local opinion leaders

• Physiotherapists may have already been using

aspects of psychosocial management (the intervention

focus) for patients prior to the intervention.

• Little change was identified for the intervention

group in what participants perceived to be important

to patient recovery, actual clinical practice following

the intervention, and treatment options used.

Strong

210 L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

Table 1

Summary of characteristics and findings of studies, arranged according region.

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

UK research

Upton 2012 [13] Opportunistic sample,

154 newly qualified

AHPs (response

rate = 27%)

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey

Assess and

characterise adoption

of EBP within newly

qualified AHPs’

clinical practice

• No statistically significant differences on EBP Use,

Attitudes or knowledge/skills between allied health

professions.

• Changes to education/training in recent years have

increased adoption and implementation of EBP

among newly qualified AHPs

• Adoption and implementation of EBP may be

influenced by education and support in tertiary

settings.

Weak

Bourne 2007 [36] Random sample, 134

community

physiotherapists from

Community Trusts

(response rate 67%).

Questionnaire

development and

descriptive,

cross-sectional survey

Identify perceived

professional,

educational and

personal needs of

community

physiotherapists, and

determine good

practice in meeting

these needs

• 51% of participants had no specific continuing

professional development learning objectives.

• Barriers to EBP: access to library resources within

reasonable travelling distance, skills to use library

facilities effectively, confidence to critically appraise

literature, training opportunities to develop skills,

opportunity to discuss research evidence with

colleagues., computer access, and time and skills to

use computer resources.

• Participants who had access to and taken up support

(e.g. mentorship and journal clubs) had more positive

EBP attitudes.

Weak

Caldwell 2007 [5] Random sample,

recent graduates from

3 London Universities

(response rate = 43%);

Social workers

(N = 26),

Occupational

Therapists (N = 29),

Physiotherapists

(N = 10), and Nurses

(N = 1)

Descriptive,

cross-sectional postal

questionnaire

Explore relevance of

initial professional

training on EBP and

explore practitioners’

confidence in

engaging with EBP

• 76% stated that they had received training in

conducting literature searches

• Positive attitudes held towards EBP and research;

implementation of EBP by practitioners is infrequent

with limited use of research resources.

• Despite 72% agreeing that EBP is favoured among

colleagues, 58% agreed that there was a lack of time

for EBP.

Moderate

Stevenson 2006 [39] Census of a

Community Trust in

North Staffordshire

(N = 30)

Intervention design

with random

assignment;

intervention group

(n = 17), control group

(n = 13) Questionnaire

survey.

Explore community

physiotherapists’

change in clinical

management of

patients with low back

pain (LBP) following

an educational

intervention, using

local opinion leaders

• Physiotherapists may have already been using

aspects of psychosocial management (the intervention

focus) for patients prior to the intervention.

• Little change was identified for the intervention

group in what participants perceived to be important

to patient recovery, actual clinical practice following

the intervention, and treatment options used.

Strong

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Author's personal copy

L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219 211

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Upton 2006 [12] Stratified sample,

1000 AHPs (response

rate = 67%), 137 of

which were

physiotherapists

(response rate = 72%).

Descriptive postal

survey

Explore AHPs’

practice and

knowledge of EBP.

• Physiotherapists reported greater knowledge of EBP

than podiatrists, radiographers and orthoptists, but similar

knowledge levels to occupational therapists, dieticians,

speech and language therapists and psychologists.

• Substantial proportion of physiotherapists (35%)

self-reported their knowledge as high, with the majority

self-reporting as medium (45%).

• Barriers to EBP similar between all AHPs; two key

barriers identified: lack of time and money.

Weak

Stevenson 2004 [22] Census (N = 30) of

physiotherapists from

a Community Trust in

North Staffordshire.

Intervention design

with random

assignment;

intervention group

(n = 17), control group

(n = 13) Questionnaire

survey.

Explore community

physiotherapists’

change in clinical

management of

patients with low back

pain (LBP) following

an educational

intervention, using

local opinion leaders.

• Most believed clinical practice should be based on best

evidence.

• Practitioners reported relying on courses and in-service

training for informing practice.

• Literature, journals and research all rated as low priority

for best clinical practice.

Strong

Palfreyman 2003 [10] Physiotherapists

(N = 37, response

rate = 37%)) and

nurses (N = 53,

response rate = 24%)

from a teaching

hospital.

Cross-sectional,

descriptive survey.

Investigate

physiotherapists’ and

nurses’ EBP

perceptions, skills and

barriers.

• Information from the client and personal experience

most common sources used in decision-making, the

Internet was the least used source.

• Physiotherapists more likely to report lack of skills in

finding resources than nurses, less likely to report limited

access to research.

• 73% of nurses and physiotherapists reported lack of time

as main barrier, followed by colleagues and organisation.

Weak

Barnard 2001 [19] Random sample, 56

physiotherapists

working in a variety

of NHS treatment

settings.

Qualitative; focus

groups, group and

individual interviews.

Analysed using

thematic analysis.

Identify

physiotherapists’

understanding of EBP,

their views as to its

appropriateness in

physiotherapy and

what factors promote

or discouraged its

development.

• Physiotherapists held different definitions of EBP, based

on views of what constitutes ‘evidence’ (e.g. research vs.

practice-based).

• All felt EBP was important.

• Barriers & enablers of EBP: access to resources,

workplace culture, ability to challenge senior colleagues’

views, suspicion of research, time, money and

involvement with clinical interest groups and poor

dissemination of best evidence information.

Moderate

European research

Heiwe 2011 [11] Opportunistic sample,

227 AHPs at a

Swedish University

hospital (response rate

of 74% overall): 129

physiotherapists

(response rate of

70%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey.

Explore allied health

professionals’

attitudes, beliefs,

knowledge and

behaviour concerning

EBP.

• EBP perceived to not take into account the limitations of

the clinical practice setting.

• Physiotherapists scored significantly lower on the belief

that EBP improves the quality of care, that they needed to

increase the use of evidence in their daily practice, and

that they wanted to learn and improve the skills necessary

to incorporate EBP into their practice.

• Physiotherapists read and reviewed research

significantly more often and more likely to say EBP

helped them to make decisions about patient care.

Moderate

L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219 211

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Upton 2006 [12] Stratified sample,

1000 AHPs (response

rate = 67%), 137 of

which were

physiotherapists

(response rate = 72%).

Descriptive postal

survey

Explore AHPs’

practice and

knowledge of EBP.

• Physiotherapists reported greater knowledge of EBP

than podiatrists, radiographers and orthoptists, but similar

knowledge levels to occupational therapists, dieticians,

speech and language therapists and psychologists.

• Substantial proportion of physiotherapists (35%)

self-reported their knowledge as high, with the majority

self-reporting as medium (45%).

• Barriers to EBP similar between all AHPs; two key

barriers identified: lack of time and money.

Weak

Stevenson 2004 [22] Census (N = 30) of

physiotherapists from

a Community Trust in

North Staffordshire.

Intervention design

with random

assignment;

intervention group

(n = 17), control group

(n = 13) Questionnaire

survey.

Explore community

physiotherapists’

change in clinical

management of

patients with low back

pain (LBP) following

an educational

intervention, using

local opinion leaders.

• Most believed clinical practice should be based on best

evidence.

• Practitioners reported relying on courses and in-service

training for informing practice.

• Literature, journals and research all rated as low priority

for best clinical practice.

Strong

Palfreyman 2003 [10] Physiotherapists

(N = 37, response

rate = 37%)) and

nurses (N = 53,

response rate = 24%)

from a teaching

hospital.

Cross-sectional,

descriptive survey.

Investigate

physiotherapists’ and

nurses’ EBP

perceptions, skills and

barriers.

• Information from the client and personal experience

most common sources used in decision-making, the

Internet was the least used source.

• Physiotherapists more likely to report lack of skills in

finding resources than nurses, less likely to report limited

access to research.

• 73% of nurses and physiotherapists reported lack of time

as main barrier, followed by colleagues and organisation.

Weak

Barnard 2001 [19] Random sample, 56

physiotherapists

working in a variety

of NHS treatment

settings.

Qualitative; focus

groups, group and

individual interviews.

Analysed using

thematic analysis.

Identify

physiotherapists’

understanding of EBP,

their views as to its

appropriateness in

physiotherapy and

what factors promote

or discouraged its

development.

• Physiotherapists held different definitions of EBP, based

on views of what constitutes ‘evidence’ (e.g. research vs.

practice-based).

• All felt EBP was important.

• Barriers & enablers of EBP: access to resources,

workplace culture, ability to challenge senior colleagues’

views, suspicion of research, time, money and

involvement with clinical interest groups and poor

dissemination of best evidence information.

Moderate

European research

Heiwe 2011 [11] Opportunistic sample,

227 AHPs at a

Swedish University

hospital (response rate

of 74% overall): 129

physiotherapists

(response rate of

70%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey.

Explore allied health

professionals’

attitudes, beliefs,

knowledge and

behaviour concerning

EBP.

• EBP perceived to not take into account the limitations of

the clinical practice setting.

• Physiotherapists scored significantly lower on the belief

that EBP improves the quality of care, that they needed to

increase the use of evidence in their daily practice, and

that they wanted to learn and improve the skills necessary

to incorporate EBP into their practice.

• Physiotherapists read and reviewed research

significantly more often and more likely to say EBP

helped them to make decisions about patient care.

Moderate

Author's personal copy

212 L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

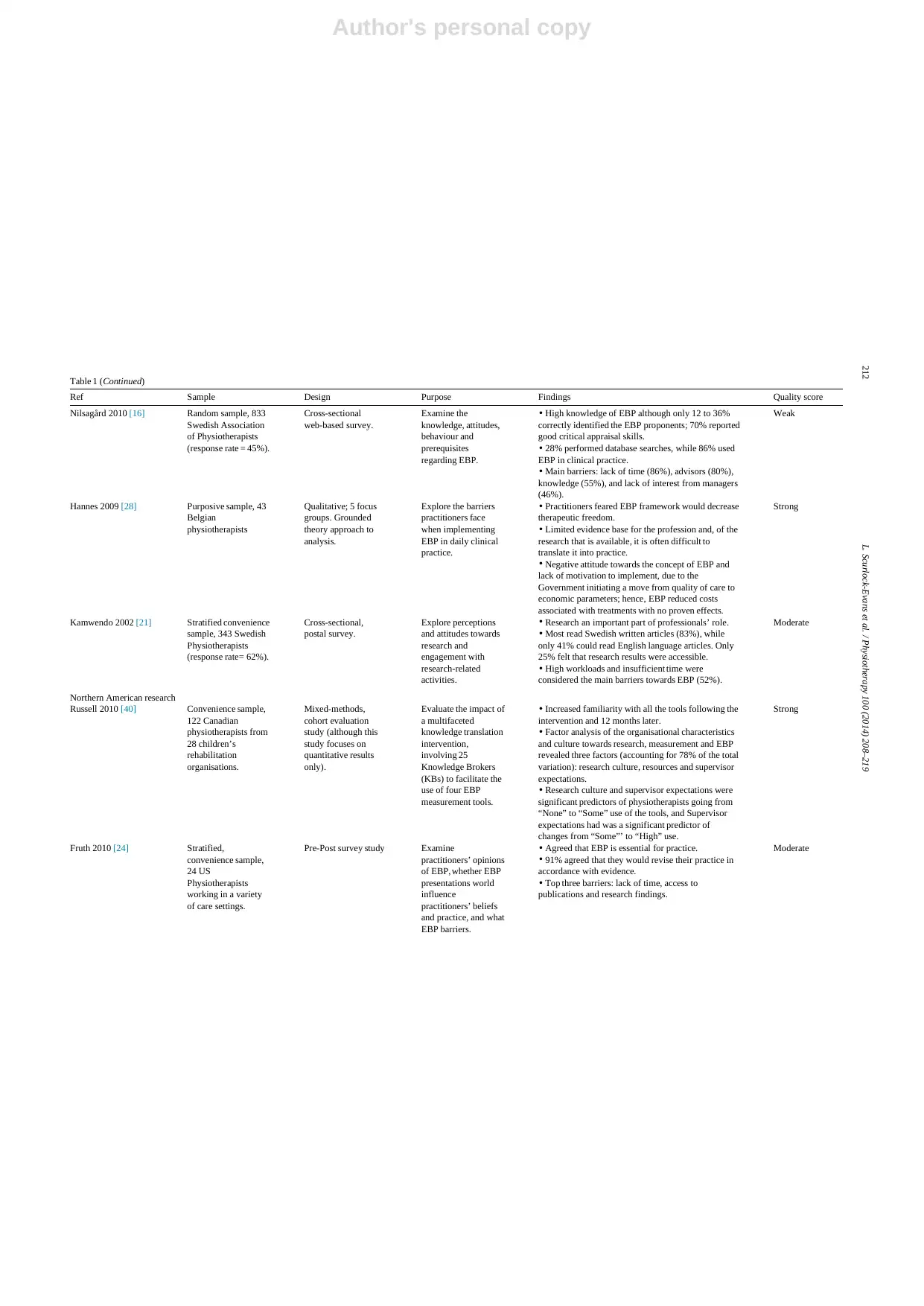

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Nilsagård 2010 [16] Random sample, 833

Swedish Association

of Physiotherapists

(response rate = 45%).

Cross-sectional

web-based survey.

Examine the

knowledge, attitudes,

behaviour and

prerequisites

regarding EBP.

• High knowledge of EBP although only 12 to 36%

correctly identified the EBP proponents; 70% reported

good critical appraisal skills.

• 28% performed database searches, while 86% used

EBP in clinical practice.

• Main barriers: lack of time (86%), advisors (80%),

knowledge (55%), and lack of interest from managers

(46%).

Weak

Hannes 2009 [28] Purposive sample, 43

Belgian

physiotherapists

Qualitative; 5 focus

groups. Grounded

theory approach to

analysis.

Explore the barriers

practitioners face

when implementing

EBP in daily clinical

practice.

• Practitioners feared EBP framework would decrease

therapeutic freedom.

• Limited evidence base for the profession and, of the

research that is available, it is often difficult to

translate it into practice.

• Negative attitude towards the concept of EBP and

lack of motivation to implement, due to the

Government initiating a move from quality of care to

economic parameters; hence, EBP reduced costs

associated with treatments with no proven effects.

Strong

Kamwendo 2002 [21] Stratified convenience

sample, 343 Swedish

Physiotherapists

(response rate= 62%).

Cross-sectional,

postal survey.

Explore perceptions

and attitudes towards

research and

engagement with

research-related

activities.

• Research an important part of professionals’ role.

• Most read Swedish written articles (83%), while

only 41% could read English language articles. Only

25% felt that research results were accessible.

• High workloads and insufficient time were

considered the main barriers towards EBP (52%).

Moderate

Northern American research

Russell 2010 [40] Convenience sample,

122 Canadian

physiotherapists from

28 children’s

rehabilitation

organisations.

Mixed-methods,

cohort evaluation

study (although this

study focuses on

quantitative results

only).

Evaluate the impact of

a multifaceted

knowledge translation

intervention,

involving 25

Knowledge Brokers

(KBs) to facilitate the

use of four EBP

measurement tools.

• Increased familiarity with all the tools following the

intervention and 12 months later.

• Factor analysis of the organisational characteristics

and culture towards research, measurement and EBP

revealed three factors (accounting for 78% of the total

variation): research culture, resources and supervisor

expectations.

• Research culture and supervisor expectations were

significant predictors of physiotherapists going from

“None” to “Some” use of the tools, and Supervisor

expectations had was a significant predictor of

changes from “Some”’ to “High” use.

Strong

Fruth 2010 [24] Stratified,

convenience sample,

24 US

Physiotherapists

working in a variety

of care settings.

Pre-Post survey study Examine

practitioners’ opinions

of EBP, whether EBP

presentations world

influence

practitioners’ beliefs

and practice, and what

EBP barriers.

• Agreed that EBP is essential for practice.

• 91% agreed that they would revise their practice in

accordance with evidence.

• Top three barriers: lack of time, access to

publications and research findings.

Moderate

212 L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Nilsagård 2010 [16] Random sample, 833

Swedish Association

of Physiotherapists

(response rate = 45%).

Cross-sectional

web-based survey.

Examine the

knowledge, attitudes,

behaviour and

prerequisites

regarding EBP.

• High knowledge of EBP although only 12 to 36%

correctly identified the EBP proponents; 70% reported

good critical appraisal skills.

• 28% performed database searches, while 86% used

EBP in clinical practice.

• Main barriers: lack of time (86%), advisors (80%),

knowledge (55%), and lack of interest from managers

(46%).

Weak

Hannes 2009 [28] Purposive sample, 43

Belgian

physiotherapists

Qualitative; 5 focus

groups. Grounded

theory approach to

analysis.

Explore the barriers

practitioners face

when implementing

EBP in daily clinical

practice.

• Practitioners feared EBP framework would decrease

therapeutic freedom.

• Limited evidence base for the profession and, of the

research that is available, it is often difficult to

translate it into practice.

• Negative attitude towards the concept of EBP and

lack of motivation to implement, due to the

Government initiating a move from quality of care to

economic parameters; hence, EBP reduced costs

associated with treatments with no proven effects.

Strong

Kamwendo 2002 [21] Stratified convenience

sample, 343 Swedish

Physiotherapists

(response rate= 62%).

Cross-sectional,

postal survey.

Explore perceptions

and attitudes towards

research and

engagement with

research-related

activities.

• Research an important part of professionals’ role.

• Most read Swedish written articles (83%), while

only 41% could read English language articles. Only

25% felt that research results were accessible.

• High workloads and insufficient time were

considered the main barriers towards EBP (52%).

Moderate

Northern American research

Russell 2010 [40] Convenience sample,

122 Canadian

physiotherapists from

28 children’s

rehabilitation

organisations.

Mixed-methods,

cohort evaluation

study (although this

study focuses on

quantitative results

only).

Evaluate the impact of

a multifaceted

knowledge translation

intervention,

involving 25

Knowledge Brokers

(KBs) to facilitate the

use of four EBP

measurement tools.

• Increased familiarity with all the tools following the

intervention and 12 months later.

• Factor analysis of the organisational characteristics

and culture towards research, measurement and EBP

revealed three factors (accounting for 78% of the total

variation): research culture, resources and supervisor

expectations.

• Research culture and supervisor expectations were

significant predictors of physiotherapists going from

“None” to “Some” use of the tools, and Supervisor

expectations had was a significant predictor of

changes from “Some”’ to “High” use.

Strong

Fruth 2010 [24] Stratified,

convenience sample,

24 US

Physiotherapists

working in a variety

of care settings.

Pre-Post survey study Examine

practitioners’ opinions

of EBP, whether EBP

presentations world

influence

practitioners’ beliefs

and practice, and what

EBP barriers.

• Agreed that EBP is essential for practice.

• 91% agreed that they would revise their practice in

accordance with evidence.

• Top three barriers: lack of time, access to

publications and research findings.

Moderate

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Author's personal copy

L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219 213

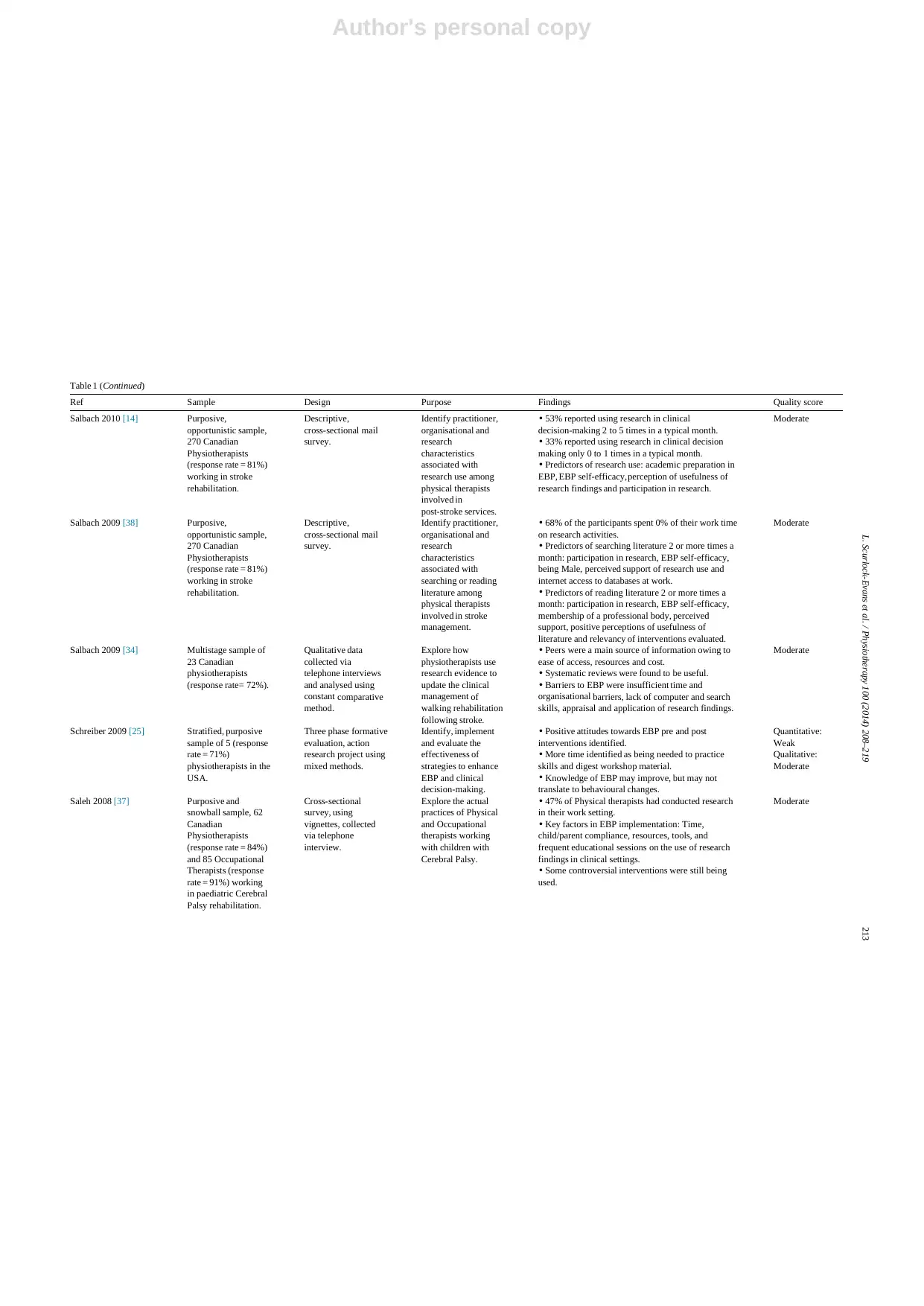

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Salbach 2010 [14] Purposive,

opportunistic sample,

270 Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 81%)

working in stroke

rehabilitation.

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Identify practitioner,

organisational and

research

characteristics

associated with

research use among

physical therapists

involved in

post-stroke services.

• 53% reported using research in clinical

decision-making 2 to 5 times in a typical month.

• 33% reported using research in clinical decision

making only 0 to 1 times in a typical month.

• Predictors of research use: academic preparation in

EBP, EBP self-efficacy, perception of usefulness of

research findings and participation in research.

Moderate

Salbach 2009 [38] Purposive,

opportunistic sample,

270 Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 81%)

working in stroke

rehabilitation.

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Identify practitioner,

organisational and

research

characteristics

associated with

searching or reading

literature among

physical therapists

involved in stroke

management.

• 68% of the participants spent 0% of their work time

on research activities.

• Predictors of searching literature 2 or more times a

month: participation in research, EBP self-efficacy,

being Male, perceived support of research use and

internet access to databases at work.

• Predictors of reading literature 2 or more times a

month: participation in research, EBP self-efficacy,

membership of a professional body, perceived

support, positive perceptions of usefulness of

literature and relevancy of interventions evaluated.

Moderate

Salbach 2009 [34] Multistage sample of

23 Canadian

physiotherapists

(response rate= 72%).

Qualitative data

collected via

telephone interviews

and analysed using

constant comparative

method.

Explore how

physiotherapists use

research evidence to

update the clinical

management of

walking rehabilitation

following stroke.

• Peers were a main source of information owing to

ease of access, resources and cost.

• Systematic reviews were found to be useful.

• Barriers to EBP were insufficient time and

organisational barriers, lack of computer and search

skills, appraisal and application of research findings.

Moderate

Schreiber 2009 [25] Stratified, purposive

sample of 5 (response

rate = 71%)

physiotherapists in the

USA.

Three phase formative

evaluation, action

research project using

mixed methods.

Identify, implement

and evaluate the

effectiveness of

strategies to enhance

EBP and clinical

decision-making.

• Positive attitudes towards EBP pre and post

interventions identified.

• More time identified as being needed to practice

skills and digest workshop material.

• Knowledge of EBP may improve, but may not

translate to behavioural changes.

Quantitative:

Weak

Qualitative:

Moderate

Saleh 2008 [37] Purposive and

snowball sample, 62

Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 84%)

and 85 Occupational

Therapists (response

rate = 91%) working

in paediatric Cerebral

Palsy rehabilitation.

Cross-sectional

survey, using

vignettes, collected

via telephone

interview.

Explore the actual

practices of Physical

and Occupational

therapists working

with children with

Cerebral Palsy.

• 47% of Physical therapists had conducted research

in their work setting.

• Key factors in EBP implementation: Time,

child/parent compliance, resources, tools, and

frequent educational sessions on the use of research

findings in clinical settings.

• Some controversial interventions were still being

used.

Moderate

L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219 213

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Salbach 2010 [14] Purposive,

opportunistic sample,

270 Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 81%)

working in stroke

rehabilitation.

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Identify practitioner,

organisational and

research

characteristics

associated with

research use among

physical therapists

involved in

post-stroke services.

• 53% reported using research in clinical

decision-making 2 to 5 times in a typical month.

• 33% reported using research in clinical decision

making only 0 to 1 times in a typical month.

• Predictors of research use: academic preparation in

EBP, EBP self-efficacy, perception of usefulness of

research findings and participation in research.

Moderate

Salbach 2009 [38] Purposive,

opportunistic sample,

270 Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 81%)

working in stroke

rehabilitation.

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Identify practitioner,

organisational and

research

characteristics

associated with

searching or reading

literature among

physical therapists

involved in stroke

management.

• 68% of the participants spent 0% of their work time

on research activities.

• Predictors of searching literature 2 or more times a

month: participation in research, EBP self-efficacy,

being Male, perceived support of research use and

internet access to databases at work.

• Predictors of reading literature 2 or more times a

month: participation in research, EBP self-efficacy,

membership of a professional body, perceived

support, positive perceptions of usefulness of

literature and relevancy of interventions evaluated.

Moderate

Salbach 2009 [34] Multistage sample of

23 Canadian

physiotherapists

(response rate= 72%).

Qualitative data

collected via

telephone interviews

and analysed using

constant comparative

method.

Explore how

physiotherapists use

research evidence to

update the clinical

management of

walking rehabilitation

following stroke.

• Peers were a main source of information owing to

ease of access, resources and cost.

• Systematic reviews were found to be useful.

• Barriers to EBP were insufficient time and

organisational barriers, lack of computer and search

skills, appraisal and application of research findings.

Moderate

Schreiber 2009 [25] Stratified, purposive

sample of 5 (response

rate = 71%)

physiotherapists in the

USA.

Three phase formative

evaluation, action

research project using

mixed methods.

Identify, implement

and evaluate the

effectiveness of

strategies to enhance

EBP and clinical

decision-making.

• Positive attitudes towards EBP pre and post

interventions identified.

• More time identified as being needed to practice

skills and digest workshop material.

• Knowledge of EBP may improve, but may not

translate to behavioural changes.

Quantitative:

Weak

Qualitative:

Moderate

Saleh 2008 [37] Purposive and

snowball sample, 62

Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 84%)

and 85 Occupational

Therapists (response

rate = 91%) working

in paediatric Cerebral

Palsy rehabilitation.

Cross-sectional

survey, using

vignettes, collected

via telephone

interview.

Explore the actual

practices of Physical

and Occupational

therapists working

with children with

Cerebral Palsy.

• 47% of Physical therapists had conducted research

in their work setting.

• Key factors in EBP implementation: Time,

child/parent compliance, resources, tools, and

frequent educational sessions on the use of research

findings in clinical settings.

• Some controversial interventions were still being

used.

Moderate

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Author's personal copy

214 L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

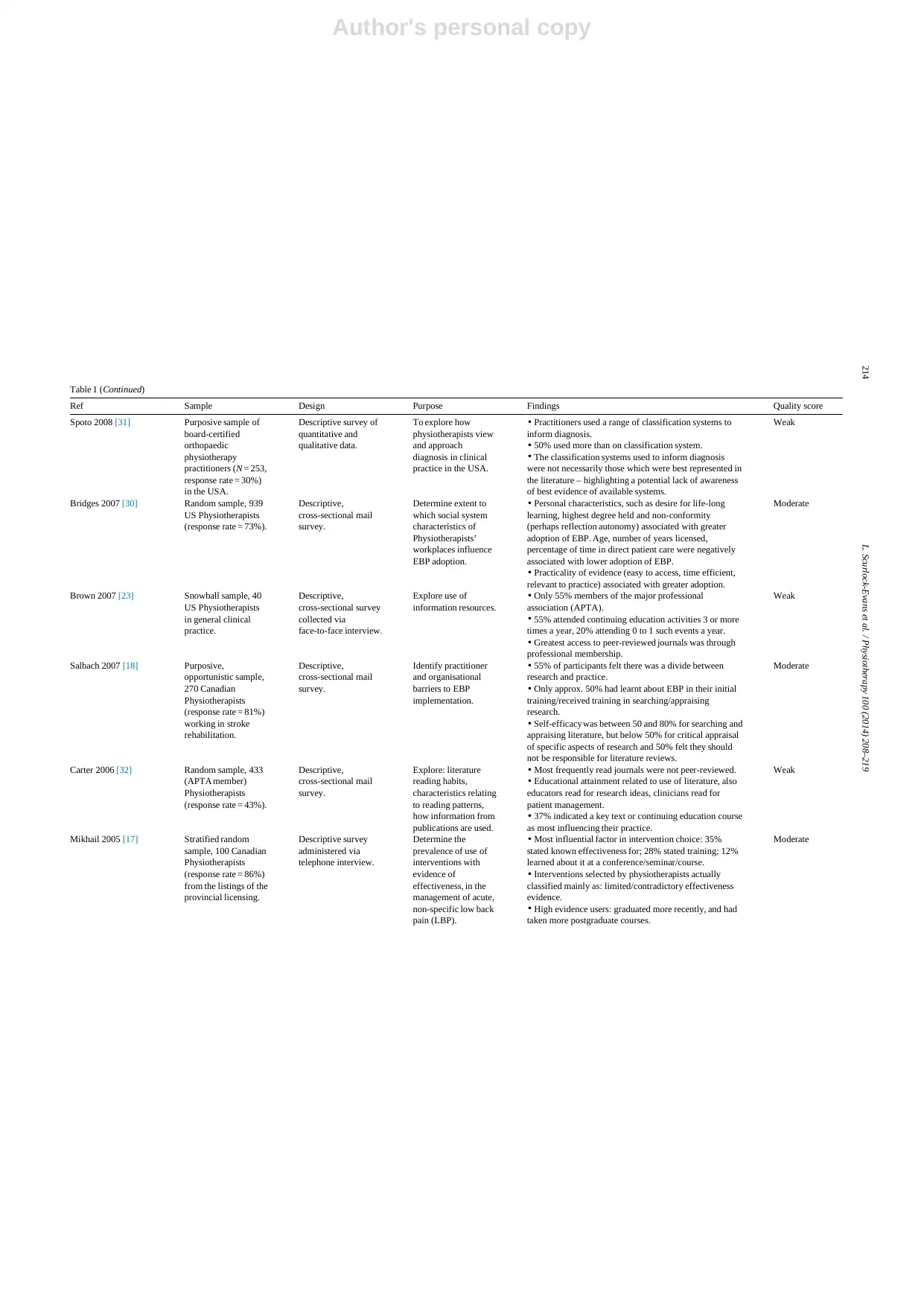

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Spoto 2008 [31] Purposive sample of

board-certified

orthopaedic

physiotherapy

practitioners (N = 253,

response rate = 30%)

in the USA.

Descriptive survey of

quantitative and

qualitative data.

To explore how

physiotherapists view

and approach

diagnosis in clinical

practice in the USA.

• Practitioners used a range of classification systems to

inform diagnosis.

• 50% used more than on classification system.

• The classification systems used to inform diagnosis

were not necessarily those which were best represented in

the literature – highlighting a potential lack of awareness

of best evidence of available systems.

Weak

Bridges 2007 [30] Random sample, 939

US Physiotherapists

(response rate = 73%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Determine extent to

which social system

characteristics of

Physiotherapists’

workplaces influence

EBP adoption.

• Personal characteristics, such as desire for life-long

learning, highest degree held and non-conformity

(perhaps reflection autonomy) associated with greater

adoption of EBP. Age, number of years licensed,

percentage of time in direct patient care were negatively

associated with lower adoption of EBP.

• Practicality of evidence (easy to access, time efficient,

relevant to practice) associated with greater adoption.

Moderate

Brown 2007 [23] Snowball sample, 40

US Physiotherapists

in general clinical

practice.

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey

collected via

face-to-face interview.

Explore use of

information resources.

• Only 55% members of the major professional

association (APTA).

• 55% attended continuing education activities 3 or more

times a year, 20% attending 0 to 1 such events a year.

• Greatest access to peer-reviewed journals was through

professional membership.

Weak

Salbach 2007 [18] Purposive,

opportunistic sample,

270 Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 81%)

working in stroke

rehabilitation.

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Identify practitioner

and organisational

barriers to EBP

implementation.

• 55% of participants felt there was a divide between

research and practice.

• Only approx. 50% had learnt about EBP in their initial

training/received training in searching/appraising

research.

• Self-efficacy was between 50 and 80% for searching and

appraising literature, but below 50% for critical appraisal

of specific aspects of research and 50% felt they should

not be responsible for literature reviews.

Moderate

Carter 2006 [32] Random sample, 433

(APTA member)

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 43%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Explore: literature

reading habits,

characteristics relating

to reading patterns,

how information from

publications are used.

• Most frequently read journals were not peer-reviewed.

• Educational attainment related to use of literature, also

educators read for research ideas, clinicians read for

patient management.

• 37% indicated a key text or continuing education course

as most influencing their practice.

Weak

Mikhail 2005 [17] Stratified random

sample, 100 Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 86%)

from the listings of the

provincial licensing.

Descriptive survey

administered via

telephone interview.

Determine the

prevalence of use of

interventions with

evidence of

effectiveness, in the

management of acute,

non-specific low back

pain (LBP).

• Most influential factor in intervention choice: 35%

stated known effectiveness for; 28% stated training; 12%

learned about it at a conference/seminar/course.

• Interventions selected by physiotherapists actually

classified mainly as: limited/contradictory effectiveness

evidence.

• High evidence users: graduated more recently, and had

taken more postgraduate courses.

Moderate

214 L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Spoto 2008 [31] Purposive sample of

board-certified

orthopaedic

physiotherapy

practitioners (N = 253,

response rate = 30%)

in the USA.

Descriptive survey of

quantitative and

qualitative data.

To explore how

physiotherapists view

and approach

diagnosis in clinical

practice in the USA.

• Practitioners used a range of classification systems to

inform diagnosis.

• 50% used more than on classification system.

• The classification systems used to inform diagnosis

were not necessarily those which were best represented in

the literature – highlighting a potential lack of awareness

of best evidence of available systems.

Weak

Bridges 2007 [30] Random sample, 939

US Physiotherapists

(response rate = 73%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Determine extent to

which social system

characteristics of

Physiotherapists’

workplaces influence

EBP adoption.

• Personal characteristics, such as desire for life-long

learning, highest degree held and non-conformity

(perhaps reflection autonomy) associated with greater

adoption of EBP. Age, number of years licensed,

percentage of time in direct patient care were negatively

associated with lower adoption of EBP.

• Practicality of evidence (easy to access, time efficient,

relevant to practice) associated with greater adoption.

Moderate

Brown 2007 [23] Snowball sample, 40

US Physiotherapists

in general clinical

practice.

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey

collected via

face-to-face interview.

Explore use of

information resources.

• Only 55% members of the major professional

association (APTA).

• 55% attended continuing education activities 3 or more

times a year, 20% attending 0 to 1 such events a year.

• Greatest access to peer-reviewed journals was through

professional membership.

Weak

Salbach 2007 [18] Purposive,

opportunistic sample,

270 Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 81%)

working in stroke

rehabilitation.

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Identify practitioner

and organisational

barriers to EBP

implementation.

• 55% of participants felt there was a divide between

research and practice.

• Only approx. 50% had learnt about EBP in their initial

training/received training in searching/appraising

research.

• Self-efficacy was between 50 and 80% for searching and

appraising literature, but below 50% for critical appraisal

of specific aspects of research and 50% felt they should

not be responsible for literature reviews.

Moderate

Carter 2006 [32] Random sample, 433

(APTA member)

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 43%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional mail

survey.

Explore: literature

reading habits,

characteristics relating

to reading patterns,

how information from

publications are used.

• Most frequently read journals were not peer-reviewed.

• Educational attainment related to use of literature, also

educators read for research ideas, clinicians read for

patient management.

• 37% indicated a key text or continuing education course

as most influencing their practice.

Weak

Mikhail 2005 [17] Stratified random

sample, 100 Canadian

Physiotherapists

(response rate = 86%)

from the listings of the

provincial licensing.

Descriptive survey

administered via

telephone interview.

Determine the

prevalence of use of

interventions with

evidence of

effectiveness, in the

management of acute,

non-specific low back

pain (LBP).

• Most influential factor in intervention choice: 35%

stated known effectiveness for; 28% stated training; 12%

learned about it at a conference/seminar/course.

• Interventions selected by physiotherapists actually

classified mainly as: limited/contradictory effectiveness

evidence.

• High evidence users: graduated more recently, and had

taken more postgraduate courses.

Moderate

Author's personal copy

L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219 215

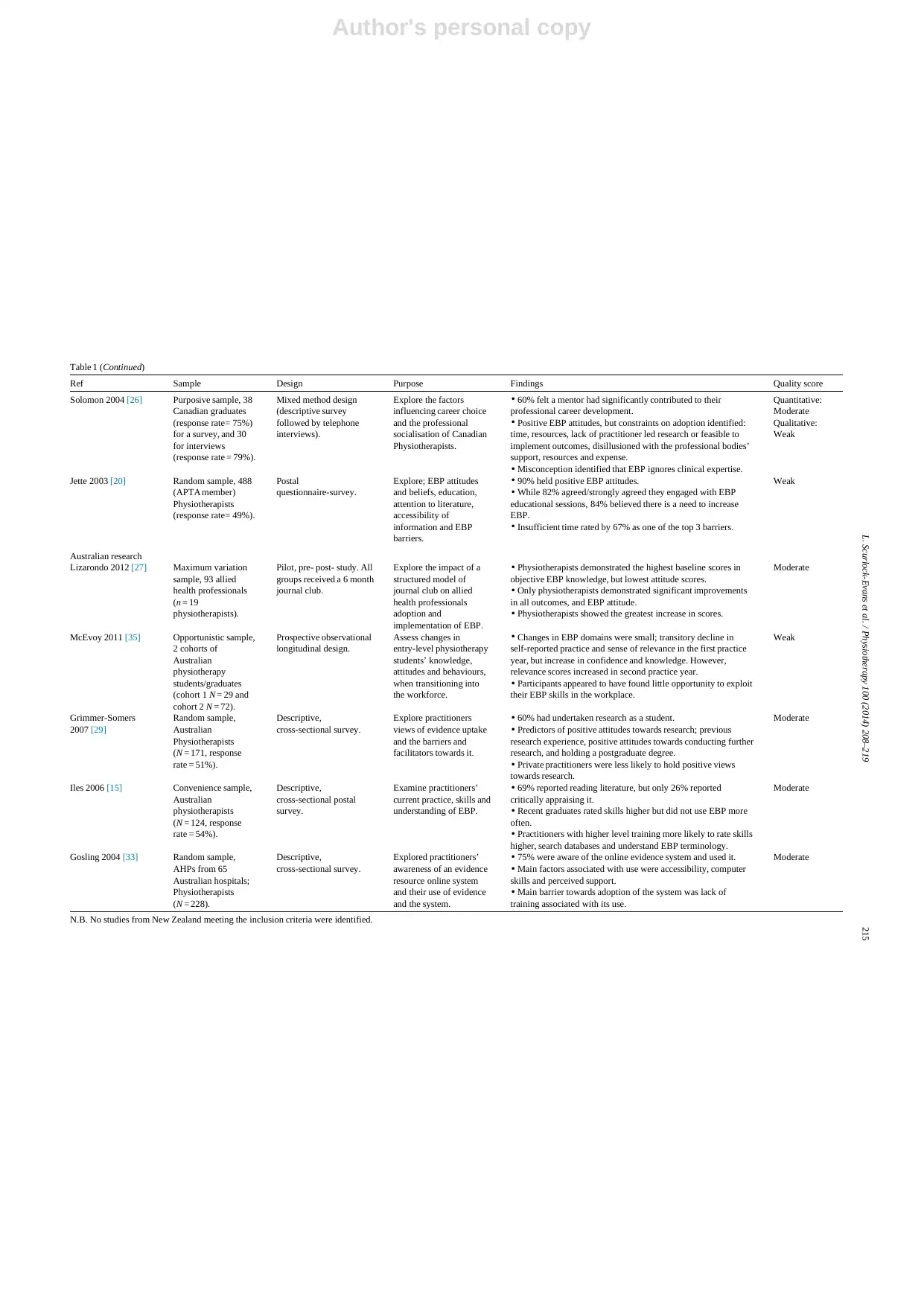

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Solomon 2004 [26] Purposive sample, 38

Canadian graduates

(response rate= 75%)

for a survey, and 30

for interviews

(response rate = 79%).

Mixed method design

(descriptive survey

followed by telephone

interviews).

Explore the factors

influencing career choice

and the professional

socialisation of Canadian

Physiotherapists.

• 60% felt a mentor had significantly contributed to their

professional career development.

• Positive EBP attitudes, but constraints on adoption identified:

time, resources, lack of practitioner led research or feasible to

implement outcomes, disillusioned with the professional bodies’

support, resources and expense.

• Misconception identified that EBP ignores clinical expertise.

Quantitative:

Moderate

Qualitative:

Weak

Jette 2003 [20] Random sample, 488

(APTA member)

Physiotherapists

(response rate= 49%).

Postal

questionnaire-survey.

Explore; EBP attitudes

and beliefs, education,

attention to literature,

accessibility of

information and EBP

barriers.

• 90% held positive EBP attitudes.

• While 82% agreed/strongly agreed they engaged with EBP

educational sessions, 84% believed there is a need to increase

EBP.

• Insufficient time rated by 67% as one of the top 3 barriers.

Weak

Australian research

Lizarondo 2012 [27] Maximum variation

sample, 93 allied

health professionals

(n = 19

physiotherapists).

Pilot, pre- post- study. All

groups received a 6 month

journal club.

Explore the impact of a

structured model of

journal club on allied

health professionals

adoption and

implementation of EBP.

• Physiotherapists demonstrated the highest baseline scores in

objective EBP knowledge, but lowest attitude scores.

• Only physiotherapists demonstrated significant improvements

in all outcomes, and EBP attitude.

• Physiotherapists showed the greatest increase in scores.

Moderate

McEvoy 2011 [35] Opportunistic sample,

2 cohorts of

Australian

physiotherapy

students/graduates

(cohort 1 N = 29 and

cohort 2 N = 72).

Prospective observational

longitudinal design.

Assess changes in

entry-level physiotherapy

students’ knowledge,

attitudes and behaviours,

when transitioning into

the workforce.

• Changes in EBP domains were small; transitory decline in

self-reported practice and sense of relevance in the first practice

year, but increase in confidence and knowledge. However,

relevance scores increased in second practice year.

• Participants appeared to have found little opportunity to exploit

their EBP skills in the workplace.

Weak

Grimmer-Somers

2007 [29]

Random sample,

Australian

Physiotherapists

(N = 171, response

rate = 51%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey.

Explore practitioners

views of evidence uptake

and the barriers and

facilitators towards it.

• 60% had undertaken research as a student.

• Predictors of positive attitudes towards research; previous

research experience, positive attitudes towards conducting further

research, and holding a postgraduate degree.

• Private practitioners were less likely to hold positive views

towards research.

Moderate

Iles 2006 [15] Convenience sample,

Australian

physiotherapists

(N = 124, response

rate = 54%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional postal

survey.

Examine practitioners’

current practice, skills and

understanding of EBP.

• 69% reported reading literature, but only 26% reported

critically appraising it.

• Recent graduates rated skills higher but did not use EBP more

often.

• Practitioners with higher level training more likely to rate skills

higher, search databases and understand EBP terminology.

Moderate

Gosling 2004 [33] Random sample,

AHPs from 65

Australian hospitals;

Physiotherapists

(N = 228).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey.

Explored practitioners’

awareness of an evidence

resource online system

and their use of evidence

and the system.

• 75% were aware of the online evidence system and used it.

• Main factors associated with use were accessibility, computer

skills and perceived support.

• Main barrier towards adoption of the system was lack of

training associated with its use.

Moderate

N.B. No studies from New Zealand meeting the inclusion criteria were identified.

L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219 215

Table 1 (Continued)

Ref Sample Design Purpose Findings Quality score

Solomon 2004 [26] Purposive sample, 38

Canadian graduates

(response rate= 75%)

for a survey, and 30

for interviews

(response rate = 79%).

Mixed method design

(descriptive survey

followed by telephone

interviews).

Explore the factors

influencing career choice

and the professional

socialisation of Canadian

Physiotherapists.

• 60% felt a mentor had significantly contributed to their

professional career development.

• Positive EBP attitudes, but constraints on adoption identified:

time, resources, lack of practitioner led research or feasible to

implement outcomes, disillusioned with the professional bodies’

support, resources and expense.

• Misconception identified that EBP ignores clinical expertise.

Quantitative:

Moderate

Qualitative:

Weak

Jette 2003 [20] Random sample, 488

(APTA member)

Physiotherapists

(response rate= 49%).

Postal

questionnaire-survey.

Explore; EBP attitudes

and beliefs, education,

attention to literature,

accessibility of

information and EBP

barriers.

• 90% held positive EBP attitudes.

• While 82% agreed/strongly agreed they engaged with EBP

educational sessions, 84% believed there is a need to increase

EBP.

• Insufficient time rated by 67% as one of the top 3 barriers.

Weak

Australian research

Lizarondo 2012 [27] Maximum variation

sample, 93 allied

health professionals

(n = 19

physiotherapists).

Pilot, pre- post- study. All

groups received a 6 month

journal club.

Explore the impact of a

structured model of

journal club on allied

health professionals

adoption and

implementation of EBP.

• Physiotherapists demonstrated the highest baseline scores in

objective EBP knowledge, but lowest attitude scores.

• Only physiotherapists demonstrated significant improvements

in all outcomes, and EBP attitude.

• Physiotherapists showed the greatest increase in scores.

Moderate

McEvoy 2011 [35] Opportunistic sample,

2 cohorts of

Australian

physiotherapy

students/graduates

(cohort 1 N = 29 and

cohort 2 N = 72).

Prospective observational

longitudinal design.

Assess changes in

entry-level physiotherapy

students’ knowledge,

attitudes and behaviours,

when transitioning into

the workforce.

• Changes in EBP domains were small; transitory decline in

self-reported practice and sense of relevance in the first practice

year, but increase in confidence and knowledge. However,

relevance scores increased in second practice year.

• Participants appeared to have found little opportunity to exploit

their EBP skills in the workplace.

Weak

Grimmer-Somers

2007 [29]

Random sample,

Australian

Physiotherapists

(N = 171, response

rate = 51%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey.

Explore practitioners

views of evidence uptake

and the barriers and

facilitators towards it.

• 60% had undertaken research as a student.

• Predictors of positive attitudes towards research; previous

research experience, positive attitudes towards conducting further

research, and holding a postgraduate degree.

• Private practitioners were less likely to hold positive views

towards research.

Moderate

Iles 2006 [15] Convenience sample,

Australian

physiotherapists

(N = 124, response

rate = 54%).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional postal

survey.

Examine practitioners’

current practice, skills and

understanding of EBP.

• 69% reported reading literature, but only 26% reported

critically appraising it.

• Recent graduates rated skills higher but did not use EBP more

often.

• Practitioners with higher level training more likely to rate skills

higher, search databases and understand EBP terminology.

Moderate

Gosling 2004 [33] Random sample,

AHPs from 65

Australian hospitals;

Physiotherapists

(N = 228).

Descriptive,

cross-sectional survey.

Explored practitioners’

awareness of an evidence

resource online system

and their use of evidence

and the system.

• 75% were aware of the online evidence system and used it.

• Main factors associated with use were accessibility, computer

skills and perceived support.

• Main barrier towards adoption of the system was lack of

training associated with its use.

Moderate

N.B. No studies from New Zealand meeting the inclusion criteria were identified.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Author's personal copy

216 L. Scurlock-Evans et al. / Physiotherapy 100 (2014) 208–219

Research suggests physiotherapists’ EBP is infrequent and

varying in quality [6]. One study [14] reported that 53% of

respondents used research in clinical decision-making only

2 to 5 times in a typical month and 33% used research only

once a month or less. Another study discovered that although

69% stated they read relevant research, only 26% critically

appraised it [15]. Furthermore, high self-ratings of EBP skills

does not necessarily translate to greater or more accurate

implementation [15]. For example, Nilsagård and Lohse [16]

found that although practitioners rated their knowledge of

EBP highly, only 12 to 36% correctly defined the EBP com-

ponents [16]. Similarly, when asked about the most influential

factors in intervention choice, 35% of a sample of Amer-

ican physiotherapists stated “known effectiveness”, despite

the interventions actually chosen having limited or contradic-

tory evidence [17]. This suggests a disparity between research

awareness, critical appraisal skills and practice. However, it

is not clear what physiotherapists in this study took “known

effectiveness” to mean.

Lastly, although physiotherapists may believe EBP is

important, they may not feel it is their responsibility to under-

take all its steps [18].

Attitudes towards EBP

The majority of studies identified positive attitudes

towards EBP and research use in practice [5,11,17–27], with

many physiotherapists viewing EBP as a necessary part of

their role which helped inform clinical decision-making.

However, misconceptions of EBP were also identified. Some

research [28] revealed less positive attitudes towards EBP

arising from concerns that it would decrease therapeutic

autonomy, resulting in a lack of motivation to implement it.

Therapists felt the drive towards EBP was economic, rather

than quality of care.

Importantly, this review highlights a disparity between

attitudes and behaviour, with some practitioners with posi-

tive attitudes failing to consistently implement EBP [15,16]

and others with less positive attitudes implementing it more

frequently [11]. This raises questions about the link between

attitudes and behaviour; particularly for EBP self-efficacy

studies, which have identified attitudes as an important, mod-

ifiable factor in EBP adoption and implementation [14].

Knowledge, skills & educational preparation

A study comparing AHP’s self-reported EBP knowledge

revealed physiotherapists’ ratings as similar to occupational

therapists, dieticians, speech and language therapists and psy-

chologists, but greater than podiatrists, radiotherapists and

orthoptists; with the vast majority (80%) of physiotherapists

rating their knowledge as mid to high [12]. In another study

[20], physiotherapists rated their self-efficacy in research and

appraising literature as mid to high (50 to 80%), but criti-

cal appraisal of psychometrics and statistics as low (<50%).

Clinicians also reported difficulty in interpreting odds ratios

[11], and research written in English when it was not their

first language [21]. Physiotherapists may also be confused

regarding what the term “evidence” actually refers to [19],