Research Report: Acute Management of Pain for Adult Patients

VerifiedAdded on 2021/06/22

|23

|5535

|24

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of acute pain management for adult patients, examining the challenges and effective strategies in pain control. It begins with an executive summary highlighting the prevalence of acute pain and the need for improved treatment approaches. The report then delves into a systematic literature analysis, outlining the obstacles to successful pain management, including both physician and patient behaviors, educational limitations, and the inherent constraints of clinical techniques. It explores the impact of ineffective pain control on patient well-being, the risks associated with chronic pain, and the role of opioids in acute pain management, while also considering the adverse effects and the potential of multimodal analgesic regimens. The methodology section details the search strategy, evidence searching techniques, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the process for selecting and analyzing relevant studies, including the assessment of study quality and the use of meta-analyses. The discussion section synthesizes the findings from individual clinical trials, systematic analyses, and retrospective studies. The report concludes with implications for practice, emphasizing the importance of effective acute pain management in improving patient outcomes and reducing the risk of chronic pain. The report provides detailed information on the different aspects of pain management, including treatment methods and medication options.

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 0

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS

Name:

Tutor:

Date:

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS

Name:

Tutor:

Date:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 1

Executive Summary

Millions of patients suffer from severe, acute pain every year. Given the recent emphasis

on pain management, the treatment of acute pain remains unsatisfactory. The goal of this

research was to recognize the obstacles to the successful treatment of acute pain and the possible

implications of ineffective pain control by examining recent literature. In a systematic literature

analysis, reviews relating to the treatment of acute pain have been outlined. Information was

collected and summarised on the underlying causes of ineffective pain management and the

sequelae associated with under-managed pain. Studies suggest that acute pain management is

inadequate due to both doctors' and patients' behaviours and educational obstacles, as well as the

inherent limits of the clinical techniques accessible. Failure to treat acute pain adversely affects

certain facets of patient wellbeing, and the risk of chronic pain is elevated. While opioids are the

recommended medication for the mildest to extreme acute pain, their adverse effects can hamper

their use and clinical efficacy. Analgesic regimens with an increased balance of

efficacy/tolerability will enhance acute pain relief and thereby decrease chronic pain occurrence.

Studies that look at the use of various analgesics with separate action pathways find that

multimodal treatments can have an increased combination of potency and tolerability over

single-agent regimens.

Executive Summary

Millions of patients suffer from severe, acute pain every year. Given the recent emphasis

on pain management, the treatment of acute pain remains unsatisfactory. The goal of this

research was to recognize the obstacles to the successful treatment of acute pain and the possible

implications of ineffective pain control by examining recent literature. In a systematic literature

analysis, reviews relating to the treatment of acute pain have been outlined. Information was

collected and summarised on the underlying causes of ineffective pain management and the

sequelae associated with under-managed pain. Studies suggest that acute pain management is

inadequate due to both doctors' and patients' behaviours and educational obstacles, as well as the

inherent limits of the clinical techniques accessible. Failure to treat acute pain adversely affects

certain facets of patient wellbeing, and the risk of chronic pain is elevated. While opioids are the

recommended medication for the mildest to extreme acute pain, their adverse effects can hamper

their use and clinical efficacy. Analgesic regimens with an increased balance of

efficacy/tolerability will enhance acute pain relief and thereby decrease chronic pain occurrence.

Studies that look at the use of various analgesics with separate action pathways find that

multimodal treatments can have an increased combination of potency and tolerability over

single-agent regimens.

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 2

Contents

Introduction.................................................................................................................................................1

Search strategy............................................................................................................................................3

Evidence searching: literature search methods for identifying relevant studies to address core

questions.................................................................................................................................................3

Inclusions and Exclusions Criteria for Review of Study................................................................................4

Discussion....................................................................................................................................................6

Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................10

Implications for Practice............................................................................................................................11

References.................................................................................................................................................13

Appendices................................................................................................................................................18

Contents

Introduction.................................................................................................................................................1

Search strategy............................................................................................................................................3

Evidence searching: literature search methods for identifying relevant studies to address core

questions.................................................................................................................................................3

Inclusions and Exclusions Criteria for Review of Study................................................................................4

Discussion....................................................................................................................................................6

Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................10

Implications for Practice............................................................................................................................11

References.................................................................................................................................................13

Appendices................................................................................................................................................18

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 3

Introduction

Pain is virtually universal and adds significantly to the burden of morbidity, illness, injury,

and the health system. Acute pain description is the neurological reaction and perception to

pathological adverse stimuli, usually occurring unexpectedly at the beginning, restricted in the

duration, which contributes to actions to prevent real or possible tissue injury. Acute pain

generally lasts less than seven days, but, it can also extend up to 30 days. Acute pain is also

chronic in some patients (Grondin et al., 2014 pp. 50-55). During surgery, acute pain is

pervasive. Pain is the commonest cause of admissions to an emergency room and is widespread

in primary, ambulatory, and hospital settings. A selection of pain relief strategies to increase the

quality of life, enhance function, and promote rehabilitation is the main decisive challenge for

acute pain treatment, thus mitigating ad hoc consequences and decreasing over-prescriptions of

opioids (Veiga et al., 2016). Data also shows that effective management of acute pain may

reduce conditions that facilitate chronic pain transfer. Apart from the underlying causes of pain,

age, sex, race/ethnicity, extreme pain, comorbidity / genetic factor, pregnancy, or breastfeeding

are factors that affect pain management. Presentation timings and health conditions can also

affect the acute treatment of pain (Baxter, J., 2012).

The control of pain is a critical skill in hospital medicine, and successful acute pain

management should be a priority for any provider of hospitals. In the last decade, the worldwide

prevalence of both medicinal and non-medical application of opioids has widely increased

(AlMakadma et al., 2013 pp. 100-110). Although non-opioid medicines and non-drug

medications are essential to the management of any acute pain, the treatment of opioids in both

opioid-naive and opioid-addicted patients remains critical. In this study, they offer a validated

guide to the suited and effective usage of opioid analgesics in the management of severe pain in

opioid-dependent patients (Koltka, 2013).

Introduction

Pain is virtually universal and adds significantly to the burden of morbidity, illness, injury,

and the health system. Acute pain description is the neurological reaction and perception to

pathological adverse stimuli, usually occurring unexpectedly at the beginning, restricted in the

duration, which contributes to actions to prevent real or possible tissue injury. Acute pain

generally lasts less than seven days, but, it can also extend up to 30 days. Acute pain is also

chronic in some patients (Grondin et al., 2014 pp. 50-55). During surgery, acute pain is

pervasive. Pain is the commonest cause of admissions to an emergency room and is widespread

in primary, ambulatory, and hospital settings. A selection of pain relief strategies to increase the

quality of life, enhance function, and promote rehabilitation is the main decisive challenge for

acute pain treatment, thus mitigating ad hoc consequences and decreasing over-prescriptions of

opioids (Veiga et al., 2016). Data also shows that effective management of acute pain may

reduce conditions that facilitate chronic pain transfer. Apart from the underlying causes of pain,

age, sex, race/ethnicity, extreme pain, comorbidity / genetic factor, pregnancy, or breastfeeding

are factors that affect pain management. Presentation timings and health conditions can also

affect the acute treatment of pain (Baxter, J., 2012).

The control of pain is a critical skill in hospital medicine, and successful acute pain

management should be a priority for any provider of hospitals. In the last decade, the worldwide

prevalence of both medicinal and non-medical application of opioids has widely increased

(AlMakadma et al., 2013 pp. 100-110). Although non-opioid medicines and non-drug

medications are essential to the management of any acute pain, the treatment of opioids in both

opioid-naive and opioid-addicted patients remains critical. In this study, they offer a validated

guide to the suited and effective usage of opioid analgesics in the management of severe pain in

opioid-dependent patients (Koltka, 2013).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 4

Search strategy

Evidence searching: literature search methods for identifying relevant studies to address

core questions

Publication Date: In 2019, electronic searches for evidence were carried out and each

database was developed (Small et al., 2020). Electronic searches will be revised; as new articles

are listed in the draft report for public review. During the updated search, the literature found

will be reviewed according to the same dual analysis method as the other studies considered in

the study. If related new literature is identified for inclusion in the report, it will be for inclusion

until the final report is submitted.

Databases of literature: A review of the published literature provided by Ovid®

MEDLINE®, PsycINFO®, Embase®, Cochrane Central Registry, and Cochrane Index of

Systematic Reviews. Identification of MEDLINE search strategies in Appendix 1.

Supplementing Searches: Additional information and systematic review data (SEADS) is

required. Therefore, giving notice from the Federal Register is required for this review.

Hand searching: For inclusive literature, checking the reference lists of the publications

used is essential.

Contacting Authors: If the published findings of a study are omitting information on

methodology or results or if they know of unpublished data, they will contact the authors for that

information in case this information is not accessible.

Process for selecting studies: In compliance with the AHRQ Guide of Methods and based

on PICOTS, pre-established requirements utilization to determine eligibility for inclusion and

exclusion of abstracts. Double-checking of omitted abstracts (Voshall et al., 2013). Both omitted

Search strategy

Evidence searching: literature search methods for identifying relevant studies to address

core questions

Publication Date: In 2019, electronic searches for evidence were carried out and each

database was developed (Small et al., 2020). Electronic searches will be revised; as new articles

are listed in the draft report for public review. During the updated search, the literature found

will be reviewed according to the same dual analysis method as the other studies considered in

the study. If related new literature is identified for inclusion in the report, it will be for inclusion

until the final report is submitted.

Databases of literature: A review of the published literature provided by Ovid®

MEDLINE®, PsycINFO®, Embase®, Cochrane Central Registry, and Cochrane Index of

Systematic Reviews. Identification of MEDLINE search strategies in Appendix 1.

Supplementing Searches: Additional information and systematic review data (SEADS) is

required. Therefore, giving notice from the Federal Register is required for this review.

Hand searching: For inclusive literature, checking the reference lists of the publications

used is essential.

Contacting Authors: If the published findings of a study are omitting information on

methodology or results or if they know of unpublished data, they will contact the authors for that

information in case this information is not accessible.

Process for selecting studies: In compliance with the AHRQ Guide of Methods and based

on PICOTS, pre-established requirements utilization to determine eligibility for inclusion and

exclusion of abstracts. Double-checking of omitted abstracts (Voshall et al., 2013). Both omitted

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 5

to validate their omission to ensure consistency. A minimum of one reader shall retrieve all

quotes considered eligible for inclusion. Two team members, including any article recommended

by peer reviewers or arising from the public postings process, shall autonomously assess each

full-text article for eligibility. Resolve any disparities through consensus.

The results are then summarized in categories including but not limited to: research nature,

year, environment, region, sample size, requirements for eligibility, population and clinical

features, intervention features, and outputs for each of the main questions, as illustrated in the

previous PICOTS segment. Choosing of studies to incorporate them is critical. Details important

for evaluating applicability will involve the randomized number of patients compared to the

number of patients licensed, usage of run-in or wash-out hours, and population, intervention, and

care settings characteristics (Black, S., 2012). The research data were both monitored for

coherence and comprehensiveness by a second-team member. A database would be kept for the

exclusion of studies that were omitted during the full-text process.

Inclusions and Exclusions Criteria for Review of Study

The analysis inclusion and exclusion requirements are focused on the core issues

mentioned in the previous PICOTS section. The core opioid versus non opioid treatment issues

are dependent on the comparative feasibility since the properties of analgesics are well known to

cope with acute pain (Karanikolas et al., 2010 pp. 342-355). Key non opioid treatment concerns

include similarities with sham, waitlists, routine care, monitors, and no therapy due to heightened

ambiguity over their role in acute pain relief.

The following are details on the scope of this project in analysing impact of opioids:

to validate their omission to ensure consistency. A minimum of one reader shall retrieve all

quotes considered eligible for inclusion. Two team members, including any article recommended

by peer reviewers or arising from the public postings process, shall autonomously assess each

full-text article for eligibility. Resolve any disparities through consensus.

The results are then summarized in categories including but not limited to: research nature,

year, environment, region, sample size, requirements for eligibility, population and clinical

features, intervention features, and outputs for each of the main questions, as illustrated in the

previous PICOTS segment. Choosing of studies to incorporate them is critical. Details important

for evaluating applicability will involve the randomized number of patients compared to the

number of patients licensed, usage of run-in or wash-out hours, and population, intervention, and

care settings characteristics (Black, S., 2012). The research data were both monitored for

coherence and comprehensiveness by a second-team member. A database would be kept for the

exclusion of studies that were omitted during the full-text process.

Inclusions and Exclusions Criteria for Review of Study

The analysis inclusion and exclusion requirements are focused on the core issues

mentioned in the previous PICOTS section. The core opioid versus non opioid treatment issues

are dependent on the comparative feasibility since the properties of analgesics are well known to

cope with acute pain (Karanikolas et al., 2010 pp. 342-355). Key non opioid treatment concerns

include similarities with sham, waitlists, routine care, monitors, and no therapy due to heightened

ambiguity over their role in acute pain relief.

The following are details on the scope of this project in analysing impact of opioids:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 6

Study design: They will have randomized controlled trials on all main questions (RCTs).

They will also include in sub-question E cohort studies that monitor possible confounders and

assess the impact on long-term opioid usage. In suffrage F, they will provide studies evaluating

the performance, against a reference norm, of a risk prediction instrument for opioid addiction, a

disorder with an opioid application, or overdose (Survey of Anesthesiology, 2010). We will

consider RCTs, retrospective trials, or pre-existing studies evaluating impacts on medication

patterns concerning sub question G. In all KQs, unregulated observational trials, case series, and

case notes face exclusions. Analysis of systematic assessments as facts that are in tune with a

central query, PICOTS, and procedures. The measurement of variables like methods used for

search, choosing tests, abstract results, assessing the potential for bias, and synthesizing data will

be considered as a low risk of bias (Canfield et al., 2011). Within the framework of systematic

evaluations, they update outcomes with new primary studies found in our quests. Meta-analyses

are revised if the latest data is consistent and quantity enough for impact conclusions or if the

findings of new research are conflicting with previous meta-analyses (Althuis et al., 2014). If

many structural reviews are pertinent and have a low likelihood of distortion, they pick the most

appropriate, most current, and highest quality reviews or reviews. If more than one inclusion

utilized in a specific issue, they will assess clear areas and anomalies in the reviews.

Non- English Language Assessments: They can only review papers in English but

examine the abstracts of non-English language articles in English to find research that would

otherwise satisfy inclusion requirements for better determination of possible language bias.

Study design: They will have randomized controlled trials on all main questions (RCTs).

They will also include in sub-question E cohort studies that monitor possible confounders and

assess the impact on long-term opioid usage. In suffrage F, they will provide studies evaluating

the performance, against a reference norm, of a risk prediction instrument for opioid addiction, a

disorder with an opioid application, or overdose (Survey of Anesthesiology, 2010). We will

consider RCTs, retrospective trials, or pre-existing studies evaluating impacts on medication

patterns concerning sub question G. In all KQs, unregulated observational trials, case series, and

case notes face exclusions. Analysis of systematic assessments as facts that are in tune with a

central query, PICOTS, and procedures. The measurement of variables like methods used for

search, choosing tests, abstract results, assessing the potential for bias, and synthesizing data will

be considered as a low risk of bias (Canfield et al., 2011). Within the framework of systematic

evaluations, they update outcomes with new primary studies found in our quests. Meta-analyses

are revised if the latest data is consistent and quantity enough for impact conclusions or if the

findings of new research are conflicting with previous meta-analyses (Althuis et al., 2014). If

many structural reviews are pertinent and have a low likelihood of distortion, they pick the most

appropriate, most current, and highest quality reviews or reviews. If more than one inclusion

utilized in a specific issue, they will assess clear areas and anomalies in the reviews.

Non- English Language Assessments: They can only review papers in English but

examine the abstracts of non-English language articles in English to find research that would

otherwise satisfy inclusion requirements for better determination of possible language bias.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 7

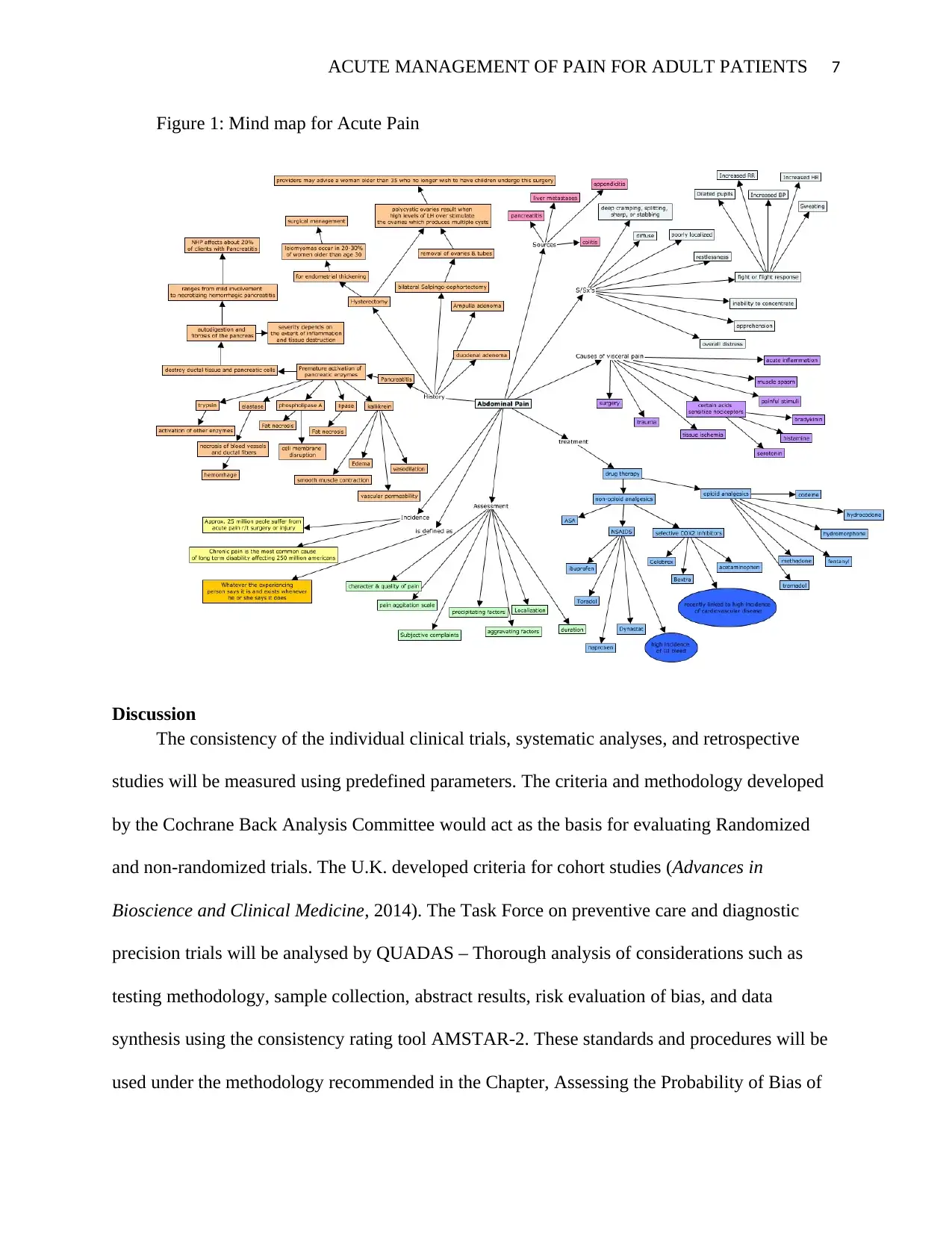

Figure 1: Mind map for Acute Pain

Discussion

The consistency of the individual clinical trials, systematic analyses, and retrospective

studies will be measured using predefined parameters. The criteria and methodology developed

by the Cochrane Back Analysis Committee would act as the basis for evaluating Randomized

and non-randomized trials. The U.K. developed criteria for cohort studies (Advances in

Bioscience and Clinical Medicine, 2014). The Task Force on preventive care and diagnostic

precision trials will be analysed by QUADAS – Thorough analysis of considerations such as

testing methodology, sample collection, abstract results, risk evaluation of bias, and data

synthesis using the consistency rating tool AMSTAR-2. These standards and procedures will be

used under the methodology recommended in the Chapter, Assessing the Probability of Bias of

Figure 1: Mind map for Acute Pain

Discussion

The consistency of the individual clinical trials, systematic analyses, and retrospective

studies will be measured using predefined parameters. The criteria and methodology developed

by the Cochrane Back Analysis Committee would act as the basis for evaluating Randomized

and non-randomized trials. The U.K. developed criteria for cohort studies (Advances in

Bioscience and Clinical Medicine, 2014). The Task Force on preventive care and diagnostic

precision trials will be analysed by QUADAS – Thorough analysis of considerations such as

testing methodology, sample collection, abstract results, risk evaluation of bias, and data

synthesis using the consistency rating tool AMSTAR-2. These standards and procedures will be

used under the methodology recommended in the Chapter, Assessing the Probability of Bias of

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 8

Individual Trials When Comparing Medical Intervention, developed by the Healthcare Research

and Quality Agency. The overall rating of "good," "fair," or "poor." will be granted to the

studies.

Studies graded as "good" consider the least chance of prejudice and are usually valid in

terms of their performance. High-quality intervention findings include consistent demographic

definitions, settings, procedures, and reference groups; a reliable method for patient care

assignment; low dropout rates and clear monitoring for dropouts; effective measures for bias

prevention; and appropriate outcome assessment. Good-quality diagnostic accuracy tests use non

patients' pick techniques; reporting of index test interpretations of no reference standard;

reporting of a predefined threshold for positive index test; reporting of the use of an acceptable

reference standard; extending a reference standard to all patients.

Studies that are graded "fair" are vulnerable to such prejudice, but not adequate to

invalidate them. These studies do not follow all the requirements for a successful quality

evaluation, but no defect or combination of defects may lead to significant distortion. There will

be a shortage of knowledge to determine shortcomings and possible obstacles in the analysis.

The fair-quality group is diverse and their strengths and weaknesses differ from one analysis to

another. The findings of some fair-grade experiments are probably accurate, while others might

only be valid.

The studies graded "poor" have structural flaws that include distortions of multiple kinds

and could make the findings null. They have a critical or "fatal" fault (or flaw mix) in the design,

examination, or documentation of the intervention. There are vast quantities of incomplete

records, reporting inconsistencies, or significant issues with the process. At least more likely are

Individual Trials When Comparing Medical Intervention, developed by the Healthcare Research

and Quality Agency. The overall rating of "good," "fair," or "poor." will be granted to the

studies.

Studies graded as "good" consider the least chance of prejudice and are usually valid in

terms of their performance. High-quality intervention findings include consistent demographic

definitions, settings, procedures, and reference groups; a reliable method for patient care

assignment; low dropout rates and clear monitoring for dropouts; effective measures for bias

prevention; and appropriate outcome assessment. Good-quality diagnostic accuracy tests use non

patients' pick techniques; reporting of index test interpretations of no reference standard;

reporting of a predefined threshold for positive index test; reporting of the use of an acceptable

reference standard; extending a reference standard to all patients.

Studies that are graded "fair" are vulnerable to such prejudice, but not adequate to

invalidate them. These studies do not follow all the requirements for a successful quality

evaluation, but no defect or combination of defects may lead to significant distortion. There will

be a shortage of knowledge to determine shortcomings and possible obstacles in the analysis.

The fair-quality group is diverse and their strengths and weaknesses differ from one analysis to

another. The findings of some fair-grade experiments are probably accurate, while others might

only be valid.

The studies graded "poor" have structural flaws that include distortions of multiple kinds

and could make the findings null. They have a critical or "fatal" fault (or flaw mix) in the design,

examination, or documentation of the intervention. There are vast quantities of incomplete

records, reporting inconsistencies, or significant issues with the process. At least more likely are

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 9

the findings of these clinical trials to indicate defects like the sample as to demonstrate a real

difference between the treatments. They would not rule out studies of poor quality because

studies of low quality, especially where there are inconsistencies between studies, will be

regarded as being less trusted than research of high quality when synthesizing the findings.

Two members of the team determine output individually. Resolving gaps is done by using

consensus. To explain the major points, they will construct evidence tables displaying sample

features, outcomes, and quality assessments for all studies included and overview tables. Meta-

analyses are done to aggregate data and to produce more accurate estimates of results that are

homogeneous enough for a reliable collective estimate to be given. The decision to perform a

quantitative synthesis would rely on two or three experiments, the completeness of the results

recorded, and the lack of heterogeneity of the results reported. They would look at the

consistency of the trial and the variability among design, patient group, treatments, and findings

studies to decide if meta-analysis is suggested and can perform sensible analyses. A random-

effects model would be used for meta-analysis.

The main problems are structured to evaluate patient populations, physical and mental

comorbidities, pain types, therapeutic properties, and dosing methods for comparative efficacy

and damage, including sensitivity approaches and stratified assessments. Performing stratified

review of the research structure and setting characteristics, for example, quality, geographic

setting, clinical setting, study design type, use of crossover design. For each core question or

condition for the predetermined outcomes, the presenting of findings is separate.

In other recent pain-related AHRQ studies, the extent of the results for pain and work is

classified by the same method used. Using the same classifications, the outcomes of pain

the findings of these clinical trials to indicate defects like the sample as to demonstrate a real

difference between the treatments. They would not rule out studies of poor quality because

studies of low quality, especially where there are inconsistencies between studies, will be

regarded as being less trusted than research of high quality when synthesizing the findings.

Two members of the team determine output individually. Resolving gaps is done by using

consensus. To explain the major points, they will construct evidence tables displaying sample

features, outcomes, and quality assessments for all studies included and overview tables. Meta-

analyses are done to aggregate data and to produce more accurate estimates of results that are

homogeneous enough for a reliable collective estimate to be given. The decision to perform a

quantitative synthesis would rely on two or three experiments, the completeness of the results

recorded, and the lack of heterogeneity of the results reported. They would look at the

consistency of the trial and the variability among design, patient group, treatments, and findings

studies to decide if meta-analysis is suggested and can perform sensible analyses. A random-

effects model would be used for meta-analysis.

The main problems are structured to evaluate patient populations, physical and mental

comorbidities, pain types, therapeutic properties, and dosing methods for comparative efficacy

and damage, including sensitivity approaches and stratified assessments. Performing stratified

review of the research structure and setting characteristics, for example, quality, geographic

setting, clinical setting, study design type, use of crossover design. For each core question or

condition for the predetermined outcomes, the presenting of findings is separate.

In other recent pain-related AHRQ studies, the extent of the results for pain and work is

classified by the same method used. Using the same classifications, the outcomes of pain

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 10

interventions in pain tests may be compared. For the intent of these reviews, the average inter-

group disparity between the pain and the pain after a 5- to a 10-point procedure at a visual

analogue scale of 0- to 100-point (vaS) is defined as the mean between 5 and 10 points, or equal

to 0.5 to 1.0 points at the 0- to 100-point Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) or 1 or 2 points at a 0

to 24-point mean 5 to 10-point difference at the ODI (Duncan, 2011). Wider/substantial effects

than moderate are described. For other effects indicators, they can add identical thresholds. Small

outcomes using the device should be below the published clinically relevant effects thresholds;

however, the clinical consequences that are affected by a range of variables, such as attitudes,

period and form of chronic pain, the magnitude, and cost of the baseline symptoms variation,

across patients are subjective (Sharpe., 2016). A minor increase in pain or function with low-cost

or no significant harm can be important for some patients (Lehmann et al., 2016).

If data is synthesized quantitatively or qualitatively, the strength of the evidence on each

main question/evidence body will first be measured by one researcher for each clinical finding

(see PICOTS). The evidence intensity will be assessed by the entire team of researchers until the

final degree on the following criteria needs to be calculated, to ensure accuracy and legitimacy of

the assessment:

Restrictions of the analysis (low, medium, or high level of study limitations)

Coherence (coherent, incompatible, or unknown/non-applicable)

Directivity (direct or indirect)

Accuracy (precise or imprecise)

Bias in reporting (suspected or undetected)

interventions in pain tests may be compared. For the intent of these reviews, the average inter-

group disparity between the pain and the pain after a 5- to a 10-point procedure at a visual

analogue scale of 0- to 100-point (vaS) is defined as the mean between 5 and 10 points, or equal

to 0.5 to 1.0 points at the 0- to 100-point Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) or 1 or 2 points at a 0

to 24-point mean 5 to 10-point difference at the ODI (Duncan, 2011). Wider/substantial effects

than moderate are described. For other effects indicators, they can add identical thresholds. Small

outcomes using the device should be below the published clinically relevant effects thresholds;

however, the clinical consequences that are affected by a range of variables, such as attitudes,

period and form of chronic pain, the magnitude, and cost of the baseline symptoms variation,

across patients are subjective (Sharpe., 2016). A minor increase in pain or function with low-cost

or no significant harm can be important for some patients (Lehmann et al., 2016).

If data is synthesized quantitatively or qualitatively, the strength of the evidence on each

main question/evidence body will first be measured by one researcher for each clinical finding

(see PICOTS). The evidence intensity will be assessed by the entire team of researchers until the

final degree on the following criteria needs to be calculated, to ensure accuracy and legitimacy of

the assessment:

Restrictions of the analysis (low, medium, or high level of study limitations)

Coherence (coherent, incompatible, or unknown/non-applicable)

Directivity (direct or indirect)

Accuracy (precise or imprecise)

Bias in reporting (suspected or undetected)

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PAIN FOR ADULT PATIENTS 11

By calculating and assessing the cumulative findings for the above areas, the quality of

evidence is given an overall rating of strong, moderate, bad, or inadequate according to a four-

level scale:

High—They are very sure that the impact prediction is near the actual result. There are

little to no flaws in the proof. They assume the results are consistent, that is to say, another

analysis would not change the results.

Moderate—They are reasonably optimistic that the effect estimation is similar to the true

effects. There are some flaws in the facts. They think the effects are potentially consistent,

although there is some uncertainty (Zin et al., 2014).

Low—they have no faith that the impact estimation is similar to the true result. The

evidence is significant or multiple (or both). They assume more proof is needed before they

assume that either the outcomes are reliable or the impact estimation is near the true value.

Inadequate — They have no proof; they cannot quantify the impact or they do not have

faith in the effect estimate for this result. No proof is present or there are unacceptable

shortcomings in the body of evidence, stopping it from concluding.

Conclusion

Acute and chronic pain has become more and more recognized as spectrum pain, as its

progression focused on original pain perception and individual biopsychosocial influences. An

adult study found that 29 percent suffered low back pain over three months, 17 percent

experienced migraine or extreme headaches, 15 percent had neck pain and 5 percent had facial or

jaw pain. In an outpatient visit study, analgesics were 11.4% among the most often continued

and recently prescribed medications (Jack et al., 2011). Training on the effective handling of

By calculating and assessing the cumulative findings for the above areas, the quality of

evidence is given an overall rating of strong, moderate, bad, or inadequate according to a four-

level scale:

High—They are very sure that the impact prediction is near the actual result. There are

little to no flaws in the proof. They assume the results are consistent, that is to say, another

analysis would not change the results.

Moderate—They are reasonably optimistic that the effect estimation is similar to the true

effects. There are some flaws in the facts. They think the effects are potentially consistent,

although there is some uncertainty (Zin et al., 2014).

Low—they have no faith that the impact estimation is similar to the true result. The

evidence is significant or multiple (or both). They assume more proof is needed before they

assume that either the outcomes are reliable or the impact estimation is near the true value.

Inadequate — They have no proof; they cannot quantify the impact or they do not have

faith in the effect estimate for this result. No proof is present or there are unacceptable

shortcomings in the body of evidence, stopping it from concluding.

Conclusion

Acute and chronic pain has become more and more recognized as spectrum pain, as its

progression focused on original pain perception and individual biopsychosocial influences. An

adult study found that 29 percent suffered low back pain over three months, 17 percent

experienced migraine or extreme headaches, 15 percent had neck pain and 5 percent had facial or

jaw pain. In an outpatient visit study, analgesics were 11.4% among the most often continued

and recently prescribed medications (Jack et al., 2011). Training on the effective handling of

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 23

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.