Case Study of Acute Severe Asthma: Health Variations 3, Spring 2018

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/03

|11

|2566

|110

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study provides a detailed analysis of acute severe asthma (ASA), focusing on its pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and priority nursing strategies. It explores the interplay of genetic and environmental factors in asthma development, highlighting the role of inflammatory cells and interleukins in airway remodeling. The case study discusses the physiological responses observed in a patient with ASA, including increased blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate, as well as reduced breath sounds and wheezing. It emphasizes the importance of initiating short-acting bronchodilators and oxygen therapy as high-priority interventions, along with assessing the severity of the asthma attack. Furthermore, the study delves into the mode of action of drugs like ipratropium, salbutamol, and hydrocortisone, outlining the nursing implications for their use, including monitoring for potential side effects and ensuring correct dosage and administration. The document concludes with relevant references and a concept map illustrating the key aspects of ASA. Desklib offers a wide range of solved assignments and study resources for students.

Running head: ACUTE SEVERE ASTHMA 1

Health Variations

Name

Institutional Affiliation

Health Variations

Name

Institutional Affiliation

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Acute Severe Asthma 2

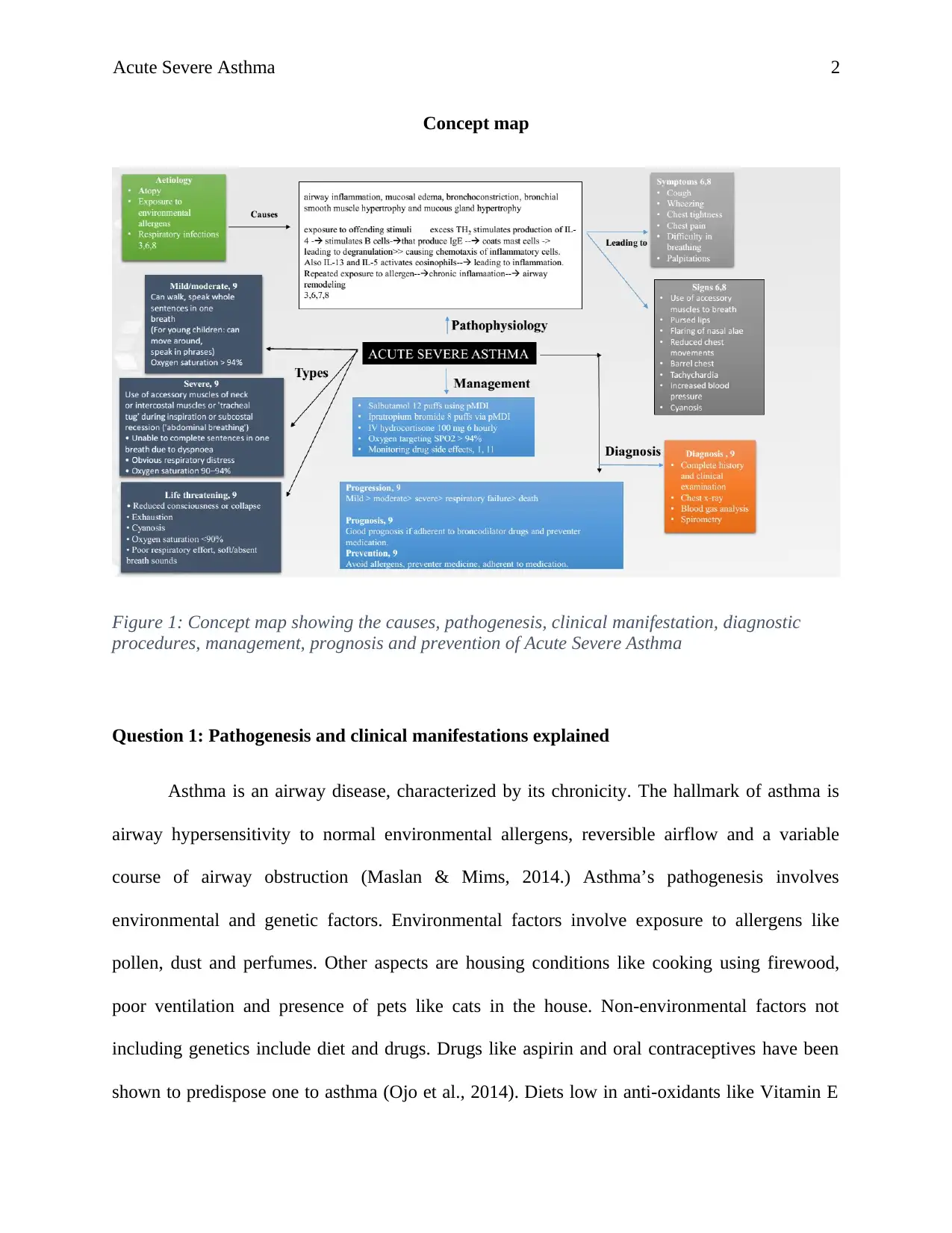

Concept map

Figure 1: Concept map showing the causes, pathogenesis, clinical manifestation, diagnostic

procedures, management, prognosis and prevention of Acute Severe Asthma

Question 1: Pathogenesis and clinical manifestations explained

Asthma is an airway disease, characterized by its chronicity. The hallmark of asthma is

airway hypersensitivity to normal environmental allergens, reversible airflow and a variable

course of airway obstruction (Maslan & Mims, 2014.) Asthma’s pathogenesis involves

environmental and genetic factors. Environmental factors involve exposure to allergens like

pollen, dust and perfumes. Other aspects are housing conditions like cooking using firewood,

poor ventilation and presence of pets like cats in the house. Non-environmental factors not

including genetics include diet and drugs. Drugs like aspirin and oral contraceptives have been

shown to predispose one to asthma (Ojo et al., 2014). Diets low in anti-oxidants like Vitamin E

Concept map

Figure 1: Concept map showing the causes, pathogenesis, clinical manifestation, diagnostic

procedures, management, prognosis and prevention of Acute Severe Asthma

Question 1: Pathogenesis and clinical manifestations explained

Asthma is an airway disease, characterized by its chronicity. The hallmark of asthma is

airway hypersensitivity to normal environmental allergens, reversible airflow and a variable

course of airway obstruction (Maslan & Mims, 2014.) Asthma’s pathogenesis involves

environmental and genetic factors. Environmental factors involve exposure to allergens like

pollen, dust and perfumes. Other aspects are housing conditions like cooking using firewood,

poor ventilation and presence of pets like cats in the house. Non-environmental factors not

including genetics include diet and drugs. Drugs like aspirin and oral contraceptives have been

shown to predispose one to asthma (Ojo et al., 2014). Diets low in anti-oxidants like Vitamin E

Acute Severe Asthma 3

and Vitamin C has also been associated with developing asthma. Genetic factors like atopy,

gender and ethnicity have been implicated to enhance progression of asthma. Others include

positive family history of asthma and polygenic intolerance.

In Jackson’s case, asthma attack can be traced back to positive family history and atopy.

This may have been triggered by an allergen. It is therefore correct to say that both genetic and

environmental factors may have played a role in Smith’s asthma attack. The two factors

combined cause airway remodeling especially in repeated exposure to an allergen (Ojo et al.,

2014).

The major etiological agent for asthma is attributed to genetic predisposition that induces

a type 1 hypersensitive reaction. Numerous inflammatory cells and interleukins play a role in the

cascade. Inflammatory cells involved are neutrophils and eosinophils. Atopic patient

demonstrates a high level of TH2 cells production. (Ojo et al., 2014).These cells stimulate

production of interleukin 4 (IL-4) that promotes the release of IgE. B cells are also responsible

for production of IgE. These B cells are usually activated by IL-13 which also oversees

production of mucus in the bronchial smooth muscles as described by Chung, (2015).

Eosinophils are usually activated by IL-5. Upon exposure to an allergen, the IgE coats mast cells

and cause degranulation to release histamine.

An early and late wave of reactions have been documented. The former is evident during

the degranulation phase of mast cells. Early wave has bronchus constriction, marked mucus

production and variable vasodilation (Lougaris et al., 2017). Epithelial vagal receptors mediate

bronchoconstriction. T-cell, eosinophil and neutrophil activation caused by inflammation is

characteristic of late phase. Airway remodeling occur when there is repeated exposure to

and Vitamin C has also been associated with developing asthma. Genetic factors like atopy,

gender and ethnicity have been implicated to enhance progression of asthma. Others include

positive family history of asthma and polygenic intolerance.

In Jackson’s case, asthma attack can be traced back to positive family history and atopy.

This may have been triggered by an allergen. It is therefore correct to say that both genetic and

environmental factors may have played a role in Smith’s asthma attack. The two factors

combined cause airway remodeling especially in repeated exposure to an allergen (Ojo et al.,

2014).

The major etiological agent for asthma is attributed to genetic predisposition that induces

a type 1 hypersensitive reaction. Numerous inflammatory cells and interleukins play a role in the

cascade. Inflammatory cells involved are neutrophils and eosinophils. Atopic patient

demonstrates a high level of TH2 cells production. (Ojo et al., 2014).These cells stimulate

production of interleukin 4 (IL-4) that promotes the release of IgE. B cells are also responsible

for production of IgE. These B cells are usually activated by IL-13 which also oversees

production of mucus in the bronchial smooth muscles as described by Chung, (2015).

Eosinophils are usually activated by IL-5. Upon exposure to an allergen, the IgE coats mast cells

and cause degranulation to release histamine.

An early and late wave of reactions have been documented. The former is evident during

the degranulation phase of mast cells. Early wave has bronchus constriction, marked mucus

production and variable vasodilation (Lougaris et al., 2017). Epithelial vagal receptors mediate

bronchoconstriction. T-cell, eosinophil and neutrophil activation caused by inflammation is

characteristic of late phase. Airway remodeling occur when there is repeated exposure to

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Acute Severe Asthma 4

allergen. This included bronchial smooth muscle hypertrophy, hypertrophy of mucus gland,

vascularization and collagen deposition in sub epithelium (Craft et al, 2015).

One of the findings was that Smith had an increased blood pressure and heart rate. This

was a physiological response to increase oxygen delivery to tissues at a time. Physical

examination also revealed reduced breath sounds and wheeze. Wheeze was experienced due to

narrowed bronchial lumen that caused turbulent flow of air as it rushed through a narrow space.

Breath sounds were reduced on auscultation because air entry was limited as a result of

narrowing of bronchial muscles (Kumar, Abbas & Aster, 2013).

Arterial blood gas showed compensated respiratory acidosis (renal compensation). This is

shown by high partial pressures of carbon dioxide at 50 mmHg. This is suggestive of long

respiratory distress as described by a book VENTILATOR, (2016). When carbon dioxide is in

excess in blood, it dissolves to form weak carbonic acid that disintegrates to release hydrogen

ions that lowers the blood pH. Short term solution for this is increased respiratory effort to wash

out the excess carbon dioxide. This is why his respiratory rate was high (at 32 breaths per

minute). Long term solution for respiratory acidosis is renal compensation. In this case, there is

increased absorption of bicarbonate ions by the kidneys to act as a buffer (Johnson, 2017).

Smith’s also presents with severe dyspnea. This is because of acute excercubation of

asthma (ASA). ASA does not respond to standard treatment with bronchodilators and

corticosteroids. Dyspnea is due to airway obstruction that is overseen by increased mucus

production as a result of hypertrophy of mucus glands. Airway narrowing is also contributed by

bronchoconstriction secondary to inflammation and airway narrowing due to remodeling that

results into hypertrophy of bronchial smooth muscles VENTILATOR, (2016). These three

factors result into reduced air entry making the patient dyspneic. As a result, there is increased

allergen. This included bronchial smooth muscle hypertrophy, hypertrophy of mucus gland,

vascularization and collagen deposition in sub epithelium (Craft et al, 2015).

One of the findings was that Smith had an increased blood pressure and heart rate. This

was a physiological response to increase oxygen delivery to tissues at a time. Physical

examination also revealed reduced breath sounds and wheeze. Wheeze was experienced due to

narrowed bronchial lumen that caused turbulent flow of air as it rushed through a narrow space.

Breath sounds were reduced on auscultation because air entry was limited as a result of

narrowing of bronchial muscles (Kumar, Abbas & Aster, 2013).

Arterial blood gas showed compensated respiratory acidosis (renal compensation). This is

shown by high partial pressures of carbon dioxide at 50 mmHg. This is suggestive of long

respiratory distress as described by a book VENTILATOR, (2016). When carbon dioxide is in

excess in blood, it dissolves to form weak carbonic acid that disintegrates to release hydrogen

ions that lowers the blood pH. Short term solution for this is increased respiratory effort to wash

out the excess carbon dioxide. This is why his respiratory rate was high (at 32 breaths per

minute). Long term solution for respiratory acidosis is renal compensation. In this case, there is

increased absorption of bicarbonate ions by the kidneys to act as a buffer (Johnson, 2017).

Smith’s also presents with severe dyspnea. This is because of acute excercubation of

asthma (ASA). ASA does not respond to standard treatment with bronchodilators and

corticosteroids. Dyspnea is due to airway obstruction that is overseen by increased mucus

production as a result of hypertrophy of mucus glands. Airway narrowing is also contributed by

bronchoconstriction secondary to inflammation and airway narrowing due to remodeling that

results into hypertrophy of bronchial smooth muscles VENTILATOR, (2016). These three

factors result into reduced air entry making the patient dyspneic. As a result, there is increased

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Acute Severe Asthma 5

respiratory effort to try bring more air rich in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide accumulating in

the blood. Poor oxygenation due to dyspnea is the reason why Smith was saturating at 90% at

room air.

Question 2: Priority nursing strategies

Initiation of a short acting bronchodilator and oxygen therapy are the two high priority

interventions that should be undertaken by nurses to manage Smith’s ASA. Severity of the

asthma attack should be assessed in order to determine the extent of initiating these procedures.

This is described in the book National Asthma Council Australia, (2017).

Bronchodilation is best achieved by giving a short acting beta agonist like salbutamol. 12

puffs equivalent to 100 mcg per actuation using pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) and a

spacer is adequate (Carotenuto, Perfetti, Calcagno, & Meriggi, 2018). A nebulizer with 5mg of

salbutamol is used in cases where the patient cannot breathe. Oxygen should also be given via a

high pressure flow (venturi) system and target a saturation of above 94% in young patients like

Smith (National Asthma Council Australia, 2017).

While giving the medication, nurses should assess if Smith is improving or not. In case of

no improvement, bronchodilator therapy is continued. Repeat doses of salbutamol every 20

minutes for first one hour (3 doses in total) or as sooner as required should be initiated. A

muscarinic receptor antagonist (ipratropium bromide, 8 puffs through pMDI or 500 mcg nebule

added to salbutamol) is added if response is still poor (National Asthma Council Australia,

2017). Oral prednisolone, a systemic corticosteroid (37.5-50 mg for 5 days) or intravenous

hydrocortisone 100 mg every 6 hours is also given to lower down inflammation. Review of

treatment in ASA is done within 1 week and a step up treatment done if no improvements have

respiratory effort to try bring more air rich in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide accumulating in

the blood. Poor oxygenation due to dyspnea is the reason why Smith was saturating at 90% at

room air.

Question 2: Priority nursing strategies

Initiation of a short acting bronchodilator and oxygen therapy are the two high priority

interventions that should be undertaken by nurses to manage Smith’s ASA. Severity of the

asthma attack should be assessed in order to determine the extent of initiating these procedures.

This is described in the book National Asthma Council Australia, (2017).

Bronchodilation is best achieved by giving a short acting beta agonist like salbutamol. 12

puffs equivalent to 100 mcg per actuation using pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) and a

spacer is adequate (Carotenuto, Perfetti, Calcagno, & Meriggi, 2018). A nebulizer with 5mg of

salbutamol is used in cases where the patient cannot breathe. Oxygen should also be given via a

high pressure flow (venturi) system and target a saturation of above 94% in young patients like

Smith (National Asthma Council Australia, 2017).

While giving the medication, nurses should assess if Smith is improving or not. In case of

no improvement, bronchodilator therapy is continued. Repeat doses of salbutamol every 20

minutes for first one hour (3 doses in total) or as sooner as required should be initiated. A

muscarinic receptor antagonist (ipratropium bromide, 8 puffs through pMDI or 500 mcg nebule

added to salbutamol) is added if response is still poor (National Asthma Council Australia,

2017). Oral prednisolone, a systemic corticosteroid (37.5-50 mg for 5 days) or intravenous

hydrocortisone 100 mg every 6 hours is also given to lower down inflammation. Review of

treatment in ASA is done within 1 week and a step up treatment done if no improvements have

Acute Severe Asthma 6

been recorded (National Asthma Council Australia, 2017). A step down therapy is done if good

control has been achieved. Smith’s minimum effective doses for controlling the symptoms and

ASA should be calculated. During this period, symptoms and peak expiratory flow rate is

monitored and follow up visit scheduled. Drug dosage expiry dates should be checked as these

can slow down the progress to a healthy patient life.

Question 3

a) Mode of action of drugs

Ipratropium is an example of a short acting anti muscarinic. It has competitive binding

properties to cholinergic receptors of bronchial smooth muscles, blocking acetylcholine and

therefore preventing bronchoconstriction (FitzGerald et al., 2018). In effect, vasodilation and

bronchodilation occurs. This is by their effect of inhibiting vagal stimulation.

Salbutamol, a short acting beta 2 adrenergic agonist acts via the G-protein coupled

pathway. After G protein is stimulated, cAMP is activated in turn activating protein kinase A.

subsequent activation of myosin light chain phosphatase and deactivation of myosin light chain

kinase occurs enabling entry of calcium via gated ion channels mediating smooth muscle

relaxation (Carotenuto, Perfetti, Calcagno, & Meriggi, 2018). This causes bronchodilation.

Hydrocortisone is a systemic corticosteroid, administered intravenously. It inhibits

inflammatory pathway in asthma by blocking phospholipase A2 which is responsible for

eicosanoids. Lipocortin-1, activated by hydrocortisone suppresses phospholipase A2. In effect,

production of eosinophils and neutrophils is inhibited (Radojicic, Keenan, & Stewart, 2016)

b) Nursing implications for drug use

been recorded (National Asthma Council Australia, 2017). A step down therapy is done if good

control has been achieved. Smith’s minimum effective doses for controlling the symptoms and

ASA should be calculated. During this period, symptoms and peak expiratory flow rate is

monitored and follow up visit scheduled. Drug dosage expiry dates should be checked as these

can slow down the progress to a healthy patient life.

Question 3

a) Mode of action of drugs

Ipratropium is an example of a short acting anti muscarinic. It has competitive binding

properties to cholinergic receptors of bronchial smooth muscles, blocking acetylcholine and

therefore preventing bronchoconstriction (FitzGerald et al., 2018). In effect, vasodilation and

bronchodilation occurs. This is by their effect of inhibiting vagal stimulation.

Salbutamol, a short acting beta 2 adrenergic agonist acts via the G-protein coupled

pathway. After G protein is stimulated, cAMP is activated in turn activating protein kinase A.

subsequent activation of myosin light chain phosphatase and deactivation of myosin light chain

kinase occurs enabling entry of calcium via gated ion channels mediating smooth muscle

relaxation (Carotenuto, Perfetti, Calcagno, & Meriggi, 2018). This causes bronchodilation.

Hydrocortisone is a systemic corticosteroid, administered intravenously. It inhibits

inflammatory pathway in asthma by blocking phospholipase A2 which is responsible for

eicosanoids. Lipocortin-1, activated by hydrocortisone suppresses phospholipase A2. In effect,

production of eosinophils and neutrophils is inhibited (Radojicic, Keenan, & Stewart, 2016)

b) Nursing implications for drug use

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Acute Severe Asthma 7

While giving Smith the drugs, the nurse in charge should be aware of their potential side

effects, and how to monitor drug use. Salbutamol use should be monitored to ensure the correct

dosage and route of administration (Carotenuto, Perfetti, Calcagno, & Meriggi, 2018). An under

dose will mean that the drug will not be effective. An overdose may lead to side effects like

headache, anxiety, tachycardia, hypotension and hypokalemia in prolonged use. Ipratropium

bromide overdose may lead to dryness of mucous membranes, urinary retention (FitzGerald et

al., 2018), while hydrocortisone overdose or prolonged use may lead to susceptibility to

infections and weight gain (Radojicic, Keenan, & Stewart, 2016).

Monitoring of drug use can be done by taking liver and renal function tests to determine

if the drugs like salbutamol are suitable for use. In case of poor renal function tests, dose

adjustment should be made or alternative drug used. Nurses should know what to do in case of

adverse effects, and the relevant authority to contact (National Asthma Council Australia, 2017).

Other aspects of monitoring drug use is to ensure correct route, dosage, correct patient, correct

drug and that the drug has not expired.

While giving Smith the drugs, the nurse in charge should be aware of their potential side

effects, and how to monitor drug use. Salbutamol use should be monitored to ensure the correct

dosage and route of administration (Carotenuto, Perfetti, Calcagno, & Meriggi, 2018). An under

dose will mean that the drug will not be effective. An overdose may lead to side effects like

headache, anxiety, tachycardia, hypotension and hypokalemia in prolonged use. Ipratropium

bromide overdose may lead to dryness of mucous membranes, urinary retention (FitzGerald et

al., 2018), while hydrocortisone overdose or prolonged use may lead to susceptibility to

infections and weight gain (Radojicic, Keenan, & Stewart, 2016).

Monitoring of drug use can be done by taking liver and renal function tests to determine

if the drugs like salbutamol are suitable for use. In case of poor renal function tests, dose

adjustment should be made or alternative drug used. Nurses should know what to do in case of

adverse effects, and the relevant authority to contact (National Asthma Council Australia, 2017).

Other aspects of monitoring drug use is to ensure correct route, dosage, correct patient, correct

drug and that the drug has not expired.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Acute Severe Asthma 8

References

Carotenuto, M., Perfetti, L., Calcagno, M. G., & Meriggi, A. (2018). Comparison of Acute

Bronchodilator Effects of Inhaled Ipratropium Bromide and Salbutamol in Adults with

Bronchial Asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 141(2), AB209.

Chung, K. F. (2015). Targeting the interleukin pathway in the treatment of asthma. The Lancet,

386(9998), 1086-1096.

Craft, J.A., Gordon, C.J., Huether, S.E., McCance, K.L., Brashers, V.L. & Rote, N.E. (2015).

Understanding pathophysiology – ANZ adaptation (2nd ed.). Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier

Australia. Chapter 24 & 25.

FitzGerald, J. M., Buhl, R., Casale, T. B., El Azzi, G., Engel, M., Sigmund, R., & Halpin, D. M.

G. (2018). Tiotropium Respimat® Reduces Episodes of Asthma Worsening in

PrimoTinA-asthma®, Irrespective of Baseline Characteristics or Season. In B65.

ASTHMA: PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL TRIALS (pp. A3947-A3947).

American Thoracic Society.

Johnson, R. A. (2017). A Quick Reference on Respiratory Acidosis. Veterinary Clinics: Small

Animal Practice, 47(2), 185-189.

Kumar, V., Abbas, A., & Aster, J. (2013). Robbins Basic Pathology (9th ed., pp. 468-470).

Canada: Elsevier Saunders.

References

Carotenuto, M., Perfetti, L., Calcagno, M. G., & Meriggi, A. (2018). Comparison of Acute

Bronchodilator Effects of Inhaled Ipratropium Bromide and Salbutamol in Adults with

Bronchial Asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 141(2), AB209.

Chung, K. F. (2015). Targeting the interleukin pathway in the treatment of asthma. The Lancet,

386(9998), 1086-1096.

Craft, J.A., Gordon, C.J., Huether, S.E., McCance, K.L., Brashers, V.L. & Rote, N.E. (2015).

Understanding pathophysiology – ANZ adaptation (2nd ed.). Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier

Australia. Chapter 24 & 25.

FitzGerald, J. M., Buhl, R., Casale, T. B., El Azzi, G., Engel, M., Sigmund, R., & Halpin, D. M.

G. (2018). Tiotropium Respimat® Reduces Episodes of Asthma Worsening in

PrimoTinA-asthma®, Irrespective of Baseline Characteristics or Season. In B65.

ASTHMA: PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL TRIALS (pp. A3947-A3947).

American Thoracic Society.

Johnson, R. A. (2017). A Quick Reference on Respiratory Acidosis. Veterinary Clinics: Small

Animal Practice, 47(2), 185-189.

Kumar, V., Abbas, A., & Aster, J. (2013). Robbins Basic Pathology (9th ed., pp. 468-470).

Canada: Elsevier Saunders.

Acute Severe Asthma 9

Lougaris, V., Moratto, D., Baronio, M., Tampella, G., van der Meer, J. W., Badolato, R., ... &

Plebani, A. (2017). Early and late B-cell developmental impairment in nuclear factor

kappa B, subunit 1–mutated common variable immunodeficiency disease. Journal of

Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 139(1), 349-352.

Maslan, J., & Mims, J. W. (2014). What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and health

care costs. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 47(1), 13-22.

National Asthma Council Australia. (2017) Australian Asthma Handbook – Quick Reference

Guide, Version 1.3. National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne. Available from:

http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au

Ojo, O. O., Basu, S., Jha, A., Ryu, M., Schwartz, J., Doeing, D., & Halayko, A. J. (2014). D29

MOLECULAR SIGNALS AND CELLULAR MECHANICS: FOCUS ON ASTHMA:

S100a8/a9 is a Mediator of Asthma Pathophysiology: In an Acute Allergic Model of

Asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 189, 1.

Radojicic, D., Keenan, C. R., & Stewart, A. G. (2016). The Physiological Glucocorticoid (GC),

Hydrocortisone, Limits Selected Actions of Synthetic GC in Human Airway Epithelium.

In A40. EPITHELIAL REGULATION OF INFLAMMATION (pp. A1472-A1472).

American Thoracic Society.

VENTILATOR, E. O. H. A. O. (2016). VARIBALE VENTILATION DECREASES AIRWAY

RESPONSIVENESS IN ASTHMA. Respirology, 21(3), 3-213.

Lougaris, V., Moratto, D., Baronio, M., Tampella, G., van der Meer, J. W., Badolato, R., ... &

Plebani, A. (2017). Early and late B-cell developmental impairment in nuclear factor

kappa B, subunit 1–mutated common variable immunodeficiency disease. Journal of

Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 139(1), 349-352.

Maslan, J., & Mims, J. W. (2014). What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and health

care costs. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 47(1), 13-22.

National Asthma Council Australia. (2017) Australian Asthma Handbook – Quick Reference

Guide, Version 1.3. National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne. Available from:

http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au

Ojo, O. O., Basu, S., Jha, A., Ryu, M., Schwartz, J., Doeing, D., & Halayko, A. J. (2014). D29

MOLECULAR SIGNALS AND CELLULAR MECHANICS: FOCUS ON ASTHMA:

S100a8/a9 is a Mediator of Asthma Pathophysiology: In an Acute Allergic Model of

Asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 189, 1.

Radojicic, D., Keenan, C. R., & Stewart, A. G. (2016). The Physiological Glucocorticoid (GC),

Hydrocortisone, Limits Selected Actions of Synthetic GC in Human Airway Epithelium.

In A40. EPITHELIAL REGULATION OF INFLAMMATION (pp. A1472-A1472).

American Thoracic Society.

VENTILATOR, E. O. H. A. O. (2016). VARIBALE VENTILATION DECREASES AIRWAY

RESPONSIVENESS IN ASTHMA. Respirology, 21(3), 3-213.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Acute Severe Asthma

10

Concept map References

3. Craft, J.A., Gordon, C.J., Huether, S.E., McCance, K.L., Brashers, V.L. & Rote, N.E. (2015).

Understanding pathophysiology – ANZ adaptation (2nd ed.). Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier

Australia. Chapter 24 & 25.

6. Kumar, V., Abbas, A., & Aster, J. (2013). Robbins Basic Pathology (9th ed., pp. 468-470).

Canada: Elsevier Saunders.

7. Lougaris, V., Moratto, D., Baronio, M., Tampella, G., van der Meer, J. W., Badolato, R., ... &

Plebani, A. (2017). Early and late B-cell developmental impairment in nuclear factor kappa B,

subunit 1–mutated common variable immunodeficiency disease. Journal of Allergy and Clinical

Immunology, 139(1), 349-352.

8. Maslan, J., & Mims, J. W. (2014). What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and

health care costs. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 47(1), 13-22.

9. National Asthma Council Australia. (2017) Australian Asthma Handbook – Quick Reference

Guide, Version 1.3. National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne. Available from:

http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au

10

Concept map References

3. Craft, J.A., Gordon, C.J., Huether, S.E., McCance, K.L., Brashers, V.L. & Rote, N.E. (2015).

Understanding pathophysiology – ANZ adaptation (2nd ed.). Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier

Australia. Chapter 24 & 25.

6. Kumar, V., Abbas, A., & Aster, J. (2013). Robbins Basic Pathology (9th ed., pp. 468-470).

Canada: Elsevier Saunders.

7. Lougaris, V., Moratto, D., Baronio, M., Tampella, G., van der Meer, J. W., Badolato, R., ... &

Plebani, A. (2017). Early and late B-cell developmental impairment in nuclear factor kappa B,

subunit 1–mutated common variable immunodeficiency disease. Journal of Allergy and Clinical

Immunology, 139(1), 349-352.

8. Maslan, J., & Mims, J. W. (2014). What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and

health care costs. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 47(1), 13-22.

9. National Asthma Council Australia. (2017) Australian Asthma Handbook – Quick Reference

Guide, Version 1.3. National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne. Available from:

http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Acute Severe Asthma

11

11

1 out of 11

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.